The impact of Globalization on the China Essay

Introduction.

One of the significant traits of the 21st century is the increasing internationalization of trade, production, investment, finance, technology, communication, politics, society, and almost any conceivable sphere. The world is shrinking towards a truly global village. Does globalization lead to equality as anticipated or brings about grave inequalities in its wake? The neoliberal ideology and the Washington consensus hold that globalization with its free trade and market competition is inbuilt to foster economic growth. However, there is enough disturbing evidence that points toward discontents and impoverishment as impacts of globalization.

The work of Professor Joseph Stiglitz Globalization and Its Discontents (2001) is a powerful critique of globalization and all its attendant consequences. He outlines the origins of IMF and the World Bank in the opening chapter, The Promise of Global Institutions . The IMF and the World Bank have their roots in 1944 in the Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. The Allies laid out their plans for a new international economic world order to prevent the recurrence of a globally devastating depression. Adhering to a new post-Depression Keynesian philosophy, the architects of the new system created the IMF to maintain economic stability by helping countries avert crises and the World Bank to induce economic development in poor countries through targeted loans and grants. WTO, which came to existence in 1994 had its precursor in the Bretton Woods era GATT with a mandate to make available a level playing field for the rich and the poor nations (Stiglitz 11). The question is how far have these financial bodies fulfilled the ambitious mandates they set out to achieve? According to Nafeez M. Ahmed of Institute for Policy Research and Development, UK, “… the world capitalist economy has created a phenomenon that can be accurately described as the globalization of insecurity, by firstly generating conflict thus destabilizing nations and communities, and secondly escalating impoverishment, disease, and deprivation” (2004).

Globalization and China

Despite many historical antecedents to our current understanding of growth in China and its causes, the current growth will be traced back to the early 1980s, as the ideological between the superpowers was concluding after more than four decades of bitter ideological conflict and the eventual supremacy of democracy and neoliberalism as the dominant principles of the New World Order. Seeking to explore the Chinese growth and globalization phenomenon by looking back over the past twenty-odd years, this essay will analyze the important antecedents to Chinese growth today.

Neoliberalism and China

Globalization, as it exists today, rests largely on the shoulders of neoliberal economics and the global entrenchment of capitalism as the dominant economic system in the world. Neo-liberalism, the belief in laissez-faire economics, was best articulated by Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom and Ronald Reagan in the United States in the 1980s. US President Ronald Regan famously remarked, “government was not the solution but the problem” (Hobsbawm 1994). Neo-liberals put all of their faith in the distributive capabilities of the invisible hand of the free market, and believe that business was inherently good and that government was bad. The government was longer interested in the provision of welfare but existed to stimulate the capitalist economic market. The United States under Ronald Reagan was thus described as the “greatest of the neo-liberal regimes” (Hobsbawm 1994). Accordingly,

The essence of neo-liberalism, its pure form, is a more or less thoroughgoing adherence, in rhetoric if not in practice, to the virtues of a market economy, and, by extension, a market-oriented society. While some neo-liberals appear to assume that one can construct any kind of ‘society’ on any kind of economy, the position taken here is that the economy, the state, and civil society are, in fact, inextricably interrelated (Coburn, 2000).

Effects of globalization

The proponents of globalization do not find any problems with globalization per se. However, they would prefer appropriate governance for managing globalization. No one can deny that the availability of huge capital required for investment in China has done wonders in the forms of modernization of technology, raising productivity, accelerating growth, and creating employment. This is of course not to rule out the havoc capital can play upon China, for example in Mexico there was a rapid destabilizing reversal of capital flows. In the highly integrated market of today, such impacts can lead to spillover effects with adverse consequences for other nations (Michael Camdessus, 1996).

The cause of success or failure in globalization is seen in privatization-driven policies. They have received much criticism in China in terms of ineffective management of corporate ventures, lack of proper resources management, and political interventions. Most cases of privatization failures are linked to poor contract design, opaque processes with heavy state involvement, lack of re-regulation, and a poor corporate governance framework. (Gopal 2007:158).

The experience of China in globalization has gone on to improve over the years. During the initial globalizing days, there was a crucial doctrinal difference between China and the IMF, about the appropriate roles of the state and the private sector, the need for fiscal equilibrium, and the virtues of deregulation. According to the official UN view, the lesser the role of the state, the better are the gains derived from privatization. This view holds that when the state dominates the economy, resources are often misallocated. However, the governments have an important role to play as a facilitator of economic activities rather than occupying the position of private entrepreneurs’. In the case of China change in policies and performance can be attributed to two factors: the changing role of the state and the globalization of the international capital markets. Since the late 80s, China has witnessed drastic shift in the orientation of economic policy. The reform results were dramatic. Meanwhile, inflation declined and currently experiencing growth. On the external side, however, the region’s current account deficit has narrowed creating and economic giant. This was due in part to the relative weakness of domestic saving at a time of sharply increasing investment, including imports of capital goods needed for industrial modernization, which were facilitated by the increased access to international capital markets” (Michael Camdessus, 1996).

WTO and China

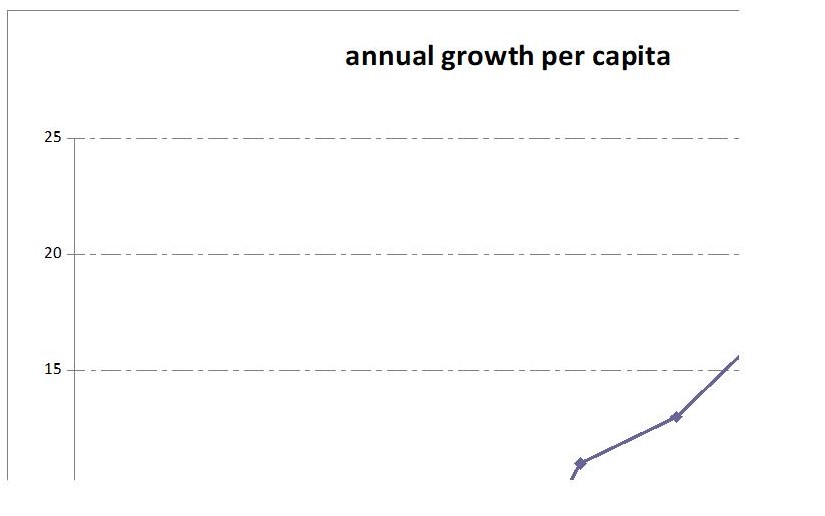

The matching of china into WTO opened new doors for growth and economic labialization. China has become the center of the world for services and external trade. Goods from China are available in the third world at a cheaper price than there before. This is because China is a developing country with a strong labor force that managed to produce goods at a cheaper price and currently they are a major international player in the trade and production of goods and services. They have diversified from the traditional form of production into the new modern technology. This has been made possible because of joining WTO. The country has also changed perceptions on how they treat foreign companies and this has made them a major direct investment country for multinationals. WTO made china open up most of its industries to be accessed by market players and this has lead to the increased growth that is being experienced currently. China started experiencing growth in the year 2000 at a faster rate than what they were experiencing initially. This is due to the growth of information technology, economic restructuring as demanded by WTO, and great growth opportunities brought by redistribution of wealth across the world due to multinationals. There is an improvement in economic growth since currently, the country is growing at the rate of 22%. Therefore WTO has brought the following positive economic effect. Increased economic growth, there is an increase in wages and salaries which are compensation to the members and this began in the year 1978. That’s when growth started being experienced in China. As growth has been experienced in china there has been increased investment geared to consumption and export. Below is a graph showing the growth of china between the years 1975 and 2008.

Globalization and democratic environment in China

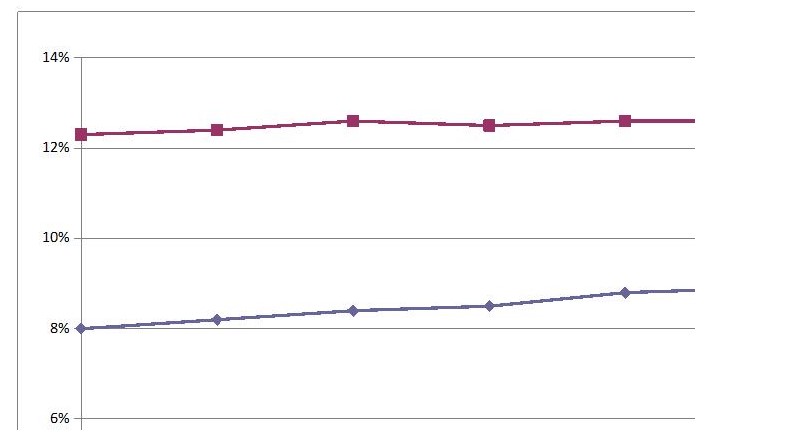

There will be no growth without politics. Politics determine the direction of the country in terms of democratic growth. The benefit of a democratic environment in china has been experienced through the growth of democratic space and this has influenced economic growth at the same time. This can be observed because it can be noted that China has cooperated with United Nations as well as the United States and WTO. If one wants to have a look at the impact of democratic space in china one should be wise enough to look at the growth as influenced by organizations as WTO, United Nations, UNEP, and many organizations. Most Chinese non-governmental organizations have received donations from this organization and this has helped them improve their lives. You look at the unemployment rate, they are coming down for example, in the year 2003, the employment rate was 4.3 and it changes to 4.2 in the year 2004. Below is a graph showing the employment rate and their changes.

The graph above shows the level of unemployment and the rate of unemployment. As the graph indicates there is an upward trend in growth that is reducing the unemployment level as well as the rate of unemployment in china. This is because the growth has been influenced by foreign capital inflow to the country.

Globalization and outsourcing

One of the positive effects of globalization to the public of china is the issue of outsourcing. The western countries have fewer laborers as compared to china. Therefore the Chinese have provided laborers for some sectors to the west industries. This earns the employees help in generating foreign income which has helped in spurring growth for the country.

Current economic growth

The current economic growth being experienced in China is due to globalization. Globalization has provided the market for Chinese growth, provided jobs to the Chinese people, and helped in influencing foreign inflow of income thus helping in economic growth. China is currently viewed by many nations as one of the best and stable economies in the world. This is because:

- Of increased market prices for goods manufactured in china,

- Increased industrial growth and agricultural development.

- Stable market prices for goods and services

- Reduction in export and increase of imports

- Increase in foreign direct investment

It can be summarized that in the long term as well as medium-term china has experienced growth that has never been experienced before.

Globalization and Chinese’s agriculture

Industrialization provides a philosophical change where people develop a different attitude towards their perception of nature. Intensified agriculture can be said to be operating as a cultural-ecological system because as a result of improved technology in agriculture, the available crop production resources are now utilized well without damage or wastage (Cowdrey, Albert E 1996).

This shows that sustainable land use should not target preserving and maintaining the ecological stand for occupation and improvement but also as developing the community and environment. This will enable it to adopt the increase and also maintenance of the options present or available as well as in the face of a natural and social world in an unending conversion.

For China to be able to produce food that will assist the country to experience faster economic growth, the use of land must be sustainable. That is involving social-economic and ecological options that will assist in reducing susceptibility and increasing options for the use of land. The country needs to adopt high technology in the use of land to improve productivity. Apart from the use of technology, crop rotation has been adapted as a viable way of improving production but it is implemented with the assistance of government-trained agriculture officers. (Cowdrey, Albert E 1996).

The use of technology and crop rotation is intended to improve production as well as make life more comfortable for the people of China. It also ensures that there is enough food for the people of China. Applicable technology involves the use of the machine, the use of irrigation in arid and semi-arid areas as well as encouraging large-scale farming for economies of scale. Agriculture in China has been made impossible because of global warming which has reduced food production thus leading to increased food prices. This is observed by the increase in food prices although the government has subsidies some farms from some farming activities as well as increased drought-resistant food crops to increase production of food.

In the era that we are today, technology has been found not only including research, design, and crafts but also it is said to be a multifaceted communal project involving maintenance, marketing, labor, management, manufacturing, and finance. As a result of industrialization through technology, in the broadest sense, it improves our abilities to change the world, since research clearly shows that a higher percentage of the world’s economy depends on agriculture (Cowdrey, Albert E 1996).

As a result of the introduction of technology, the naturally available resources can now be completely utilized. Examples include; the introduction of machines that can be used in irrigation to ensure better utilization of water whereby water can be drawn from rivers and spread to larger farms by the use of water pipes.

However, intensive agriculture and industrialization also have some things to do with demography. Though in this type of agriculture especially the large scale one is adversely affected by increased land pressure due to the rapidly growing population, there are advantages on both sides, that is, to the agricultural sector and the local people or residents whereby, the agricultural sector benefits from the availability of labor whereas the local people benefit from employment when they are picked by the farmers and given different responsibilities hence it becomes of great importance to the community by providing employment opportunities.

Social relations have some significance in the agricultural sector whereby it ensures collective responsibilities in resource management. Better relationships between different people or countries high standards of farming hence steady food supply. For example, China is one of the most industrialized countries and also densely populated thus making it enjoy good farming technologies and reliable labor supply, for this matter, the international community has established a good relationship with China by amending its grain policy to enable the international community access China’s grain market (Berry, Wendell 1998).

Culture as a factor also has something to do with intensive agriculture whereby the environment to where the type of agriculture is done should be favorable. The community should embrace it no matter what so long as it is of importance. For instance, the United States of America amended its policies which were barriers in 1990. Intensive agriculture as well depends on the way it is carried out, either large scale or small, and also the types of inputs.

Inflation is one of the problems or negative effects that china has experienced due to globalization. There has been a flow of capital into China from the west and this capital was coming from companies that are currently experiencing financial crisis making them spread the crisis to China.

Runaway Inflation which is caused by oil prices has caused food prices to go up and other consumable goods have become very expensive although the government has responded with the increased supply of food to try to reduce the shortage and ensure prices are affordable to the community. It has been complicated further by climatic changes. It is feared that global warming has had a negative impact on the production of food which has contributed to runaway inflation. Inflation in China is causing a lot of problems since life is becoming difficult for the citizens of the country. For the first time in ten years, consumer price index was at 5.6% which was higher than what the government has anticipated in the year.

Inflation in other parts of the world complicates strategies to be adopted by the Chinese government to fight run-away inflation. For example, if the government wanted to fight food prices, the option of reducing the prices of food was imported from foreign countries but it is not possible since inflation has taken a toll in most countries. For example, inflation in the United States has affected the dollar which is accepted in the national currency meaning that even imports to China will be expensive.

The government has responded with a monetary policy to ease inflation and increase economic development as well as increase employment opportunities for the citizens of the country. Using the producer price index in china which has been on the increase the government has predicted the future consumer price index through the use of these statistics a monetary policy has been designed to reduce dependence on outside importations. This has helped to create a balance in economic growth as well as inflationary tendencies and this is how they have managed to maintain their growth at 22%. The financial crisis which began as a subprime crisis in the united states has had a negative impact and added to inflation in the economy of China. The Chinese economy has been affected due to the devaluation of the dollar, strong economic growth in India, an increase in oil prices between the month of august and November 2008, the increase in food prices, and the collapse of major international banks. These factors although not directly involved they are the main causes of inflation in China.

Concluding Remarks

Globalization has been propelled by capitalism and the internationalization of the capitalist economic system. The main effect of globalization on china is the spread of neo-liberalism and the entrenchment of some capitalism– some would say the sole – viable economic system for the China economy. This essay has traced the antecedents to the current wave of globalization in china with an emphasis on key events associated with the arrival of neoliberalism in the 1980s, followed by Communist collapse and the emergence of authoritarian capitalism in China. Enthusiastically promoted by the Reagan and Thatcher regimes in America and Britain, neo-liberalism was given a huge boost following the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the fall of communism in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s. Entrenched as the dominant economic ideology across china, neo-liberalism is the underlying force behind the current wave of globalization. Despite numerous detractors on all corners of the globe, globalization remains an important force in modern society and a key component of continued and sustained economic growth on a global scale (Harvey 2007).

- Ahmed, Nafeez Mosaddeq (2004); The Globalization of Insecurity. Institute for Policy Research & Development, United Kingdom, p.113-126

- Bhagwati J.N. (2004); In Defense of Globalization, Oxford University Press. 2004

- Berry, Wendell. (1998)The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

- Camdessus M. (1996); Argentina and the Challenge of Globalization; International Monetary Fund.

- Clark, G.L. & W. B. Kim 1995. Asian NIEs & the Global Economy: Industrial Restructuring & Corporate Strategy in the 1990s. Johns Hopkins University Press, New York.

- Clark J. (2002); Globalization and the Poor: Exploitation or Equalizer. IDEA.

- Coburn, D. 2000. “Income inequality, social cohesion and the health status of populations: the role of neo-liberalism”, Social Science & Medicine, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 135-146.

- Cowdrey, Albert E. (1996) This Land, This South: An Environmental History. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky

- Gopal R. (2007); Dynamics of International Trade and Economy. Nova Publishers.

- Hale, W. & E. Kienle. 1997. After the Cold War: Security and Democracy in Africa and Asia. I.B.Tauris, London.

- Harvey, D. 2007. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press, London.

- Herman, Edward S. (1999);The Threat of Globalization, New Politics, vol. 7, no. 2 (new series), whole no. 26.

- Hobsbawm, E.1994. Age of Extremes: The Short History of the Twentieth Century: 1914-1991. Abacus, London.

- Mamman. A and Liu K (2008); The Interpretation Of Globalization Amongst Chinese Business Leaders: A Managerial And Organizational Cognition Approach, Brooks World Poverty Institute (The University Of Manchester )

- Roland R. and White K. E. (2004); Critical Concepts in Sociology. Routledge.

- Stiglitz, J. (2002); Globalization and Its Discontents. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Strayer, R. W. 1998. Why Did the Soviet Union Collapse?: Understanding Historical Change. I. E. Sharpe, New York.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, October 20). The impact of Globalization on the China. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-globalization-on-the-china/

"The impact of Globalization on the China." IvyPanda , 20 Oct. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-globalization-on-the-china/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'The impact of Globalization on the China'. 20 October.

IvyPanda . 2021. "The impact of Globalization on the China." October 20, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-globalization-on-the-china/.

1. IvyPanda . "The impact of Globalization on the China." October 20, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-globalization-on-the-china/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The impact of Globalization on the China." October 20, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-impact-of-globalization-on-the-china/.

- Neoliberalism: An Interview with David Harvey

- Relationship Between Neoliberalism and Imperialism

- Contemporary Stage of Globalization and Neo-liberalism in Europe

- Impact of Globalization and Neoliberalism on Crime and Criminal Justice

- Mexico: Transnationalism, Neoliberalism and Globalization

- The Dirty Work of Neoliberalism

- Origin, Purpose and Important Aspects of the WTO

- Neoliberalism in the U.S. Economic Policies

- Challenges to Build Feminist Movement Against Problems of Globalization and Neoliberalism

- Neo-Liberalism vs. Classic Liberalism

- Turkey and Thailand: Culture Influence on Management

- CVS Caremark Company Analysis: Management

- Business Consultancy: Sony vs Panasonic

- Sports-Qits Company Performance Analysis

- Ladies’ All Magazine, UK PEST Analysis

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- For Cambridge students

- For our researchers

- Business and enterprise

- Colleges and Departments

- Email and phone search

- Give to Cambridge

- Museums and collections

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Fees and funding

- Postgraduate events

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Visiting the University

- Annual reports

- Equality and diversity

- A global university

- Public engagement

Tracing the history of modern globalisation in China

- Research home

- About research overview

- Animal research overview

- Overseeing animal research overview

- The Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body

- Animal welfare and ethics

- Report on the allegations and matters raised in the BUAV report

- What types of animal do we use? overview

- Guinea pigs

- Naked mole-rats

- Non-human primates (marmosets)

- Other birds

- Non-technical summaries

- Animal Welfare Policy

- Alternatives to animal use

- Further information

- Funding Agency Committee Members

- Research integrity

- Horizons magazine

- Strategic Initiatives & Networks

- Nobel Prize

- Interdisciplinary Research Centres

- Open access

- Energy sector partnerships

- Podcasts overview

- S2 ep1: What is the future?

- S2 ep2: What did the future look like in the past?

- S2 ep3: What is the future of wellbeing?

- S2 ep4 What would a more just future look like?

- Research impact

A Sino-British project is examining the history of China’s first age of modern globalisation, enabling China and Britain to rediscover their interconnected past.

The ‘in-between’ nature of the Customs, at the interface between China and the rest of the world, has provided a remarkable opportunity to examine how globalisation played out in the century before China was closed off from the rest of the world in the 1950s.

Walking through the streets of Shanghai today, you see a city full of dynamism, enterprise and quirky creativity, a ‘must visit’ place that draws talents from across China and the rest of the world. Yet, in the mid-1980s you would have been struck by the fact that the former ‘Paris of the East’ seemed a gothic ruin, a melancholy reminder of a past that China had turned against after the 1949 victory of the Chinese Communist Party. China’s recent rapid take-off into globalisation, only a few short years after Deng Xiaoping, Mao Zedong’s successor, instituted the policy of ‘reform and open up’, shows that China was never entirely a closed country. History shows that wave after wave of foreign goods, people and ideas have rolled into China, been absorbed, and in turn have transformed its economy, patterns of consumption, lifestyles, imaginative life, architecture and spatial organisation.

Professor Hans van de Ven, Chair of the University’s Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, has been researching a key resource in tracing the history of modern globalisation in China: the Chinese Maritime Customs Service. In its almost century-long history between 1853 and 1950, the Customs Service kept records detailing how the key globalising commodities of the time – opium, sugar, kerosene, tobacco and arms – spread through China and were taken up differently in its regions. This little-studied institution was at the heart of China’s encounter with globalisation in the years between the Taiping Rebellion of the 1850s and the Communist assumption of power. The ‘in-between’ nature of the Customs, at the interface between China and the rest of the world, has provided a remarkable opportunity to examine how globalisation played out in the century before China was closed off from the rest of the world in the 1950s.

Seeded by a serendipitous encounter

In the late 1990s, while Professor van de Ven was studying documents at the Second Historical Archives of China in Nanjing, a chance conversation with Vice-Director Ma Zhendu led to him hearing about the recent acquisition of 55,000 files from the Customs that had just arrived by train from various parts of China. Out of this has grown a fruitful collaborative project involving historians in China and Britain that continues today.

Initial funding for the project came from the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation, an organisation for international scholarly exchange that supports and promotes the understanding of Chinese culture and society overseas. This allowed the cataloguing of all 55,000 files in the archives; an effort that took a team of four Chinese archivists four years to conclude. Professor van de Ven and his collaborator, Professor Robert Bickers of the University of Bristol, simultaneously compiled databases from Customs data on China’s international trade, wages and arms trade. In 2003, an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Major Research Grant allowed the employment of a research assistant and the recruitment of two PhD students. The project is now in full swing, with a website in operation( www.bristol.ac.uk/history/customs ), monographs being produced, guides to the archives being completed, databases in the final stages of verification, and 350 reels of microfilms now published to enable researchers worldwide to make use of the archives.

A unique institution in Sino-British history

The Customs was founded in Shanghai at the time when the Taiping Rebellion against the authority of the Qing government raged inland, and a local uprising drove Qing Dynasty officials out of the city in 1853. Bound by treaty obligations to ensure that foreign merchants fulfilled their tax obligations, the British, French and US consuls stepped in. They established a foreign board for the local Customs Stations to enforce trade tariffs. Although intended as a temporary measure, out of this small beginning grew a huge organisation whose influence rippled out across China and to the rest of the world.

The Customs managed nearly 60 harbours along China’s coast and rivers; collected about a third of the entire national revenue; established China’s national postal service; financed China’s legations abroad; assembled its contributions to international fairs and exhibitions; funded a Quarantine Service to protect China from pandemics; formed China’s coastguard and railroad police; and supported scholarly enterprises such as the translation of Western textbooks on political economy and international law.

Unique in many ways, the Customs was the only integrated national bureaucracy that continued to function through the many civil wars and foreign invasions that preceded the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. Although the Customs was always a Chinese organisation, foreigners dominated its upper echelons in rough proportion to a country’s significance in their trade with China. As Britain was the dominant trade partner, the Head of the Customs was British until the final few years of the institution, when it was led by an American. A cosmopolitan mix of French, British, Russian, German and Japanese staff worked together in the Customs, even as their countries went to war elsewhere or their armies invaded China.

Researching the files has yielded details of the complex roles that the foreigners performed within the institution. During the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, Sir Robert Hart, the Head at the time, secured the food supply to the city and effectively knocked foreign and Chinese heads together to end the fighting and restore central administration, thus helping to prevent the country’s dismemberment. (Unfortunately, he also negotiated an indemnity that crippled China financially for many years.)

The Customs was a pillar of foreign privilege in China, but China’s rulers also used ‘foreigners to control foreigners’, establishing Customs Stations with foreign Commissioners along China’s borders as bulwarks against foreign encroachment. Because of this role, Custom Houses appeared in some rather odd places, including along the mountainous border with Burma and the arid deserts of Xinjiang, as well as between Chinese and Japanese frontlines deep in inland China during the 1937–1945 War of Resistance against Japan.

More than a collector of taxes

The Customs was always much more than just a tax collection agency. It was well informed about local conditions, deeply involved in local, provincial and national politics, and also in international affairs. To some extent, its influence is still felt today. China’s Custom Houses and lighthouses often occupy the same place as those before 1949, sometimes still operating from the same buildings. Hosea Ballou Morse, one of the Chinese Customs Commissioners, and his wife were avid botanists whose samples continue to enrich Kew Gardens and helped make China’s flora popular in Britain. Many foreign Customs officials learned Chinese, wrote on Chinese history and translated Chinese books, some of which are still read today. As Chinese Studies became established as an academic discipline, universities around the world recruited Customs scholars: indeed, the founder of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, Sir Thomas Wade, was the first Professor of Chinese at Cambridge. By tapping into the vast resources of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, this research project is casting a fascinating historical perspective on the history of globalisation in China.

For more information, please contact the author Professor Hans van de Ven: ( [email protected] ) at the Department of East Asian Studies, or see the project website ( www.bristol.ac.uk/history/customs ), which was created by Professor Robert Bickers and hosts research tools and publications.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence . If you use this content on your site please link back to this page.

Read this next

War in Ukraine widens global divide in public opinion

Forgotten heroes: Study gives voice to China's nationalist WWII veterans

Beyond the pandemic: re-learn how to govern risk

Globalised economy making water, energy and land insecurity worse: study

Huangpu River, Shanghai from a China Navigation Company steamship

Credit: GW Swire and Sons Ltd and SOAS

Search research

Sign up to receive our weekly research email.

Our selection of the week's biggest Cambridge research news sent directly to your inbox. Enter your email address, confirm you're happy to receive our emails and then select 'Subscribe'.

I wish to receive a weekly Cambridge research news summary by email.

The University of Cambridge will use your email address to send you our weekly research news email. We are committed to protecting your personal information and being transparent about what information we hold. Please read our email privacy notice for details.

- globalisation

- Hans van de Van

- Department of East Asian Studies

- Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies

- School of Arts and Humanities

Related organisations

- Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)

Connect with us

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- Contact the University

- Accessibility statement

- Freedom of information

- Privacy policy and cookies

- Statement on Modern Slavery

- Terms and conditions

- University A-Z

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Cambridge University Press & Assessment

- Research news

- About research at Cambridge

- Spotlight on...

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

Introduction: China and Globalization

- Published: September 2009

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The opening of China with foreign investment, trade, and culture in 1979 produced dismay among Chinese leaders and citizens. Many Chinese citizens and leaders expressed concern about a return to foreign domination over China. The Chinese state opened the foreign trade, investment, and cultural flows in order to promote national advancement without sacrificing China’s economic and political sovereignty. As China moved from a period of economic closure in 1976 to the world’s largest recipient of foreign direct investment in 2003, the issue of how to manage the transplantation of foreign corporations and their business institutions became increasingly acute. This opening to foreign capital emphasized the impact of foreign investors on China’s domestic reforms, but such an understanding threatens to overshadow the role of domestic actors in the process. This book makes three principal contributions to the analysis of China and its political economy. In addition, it draws from two main types of sources: relevant laws and policies in China and data collected from interviews about foreign business operations, Chinese reactions to foreign businesses, and foreign and Chinese understandings of the process of transplanting institutions to China.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

World History Project - 1750 to the Present

Course: world history project - 1750 to the present > unit 9.

- READ: International Institutions

READ: Rise of China

- BEFORE YOU WATCH: Global China into the 21st Century

- WATCH: Global China into the 21st Century

- READ: Hua Guofeng (Graphic Biography)

- READ: Goods Across the World

- READ: WTO Resistance

- Economic Interactions in an Age of Intense Globalization

First read: preview and skimming for gist

Second read: key ideas and understanding content.

- What were some of the important developments in the economy of the People’s Republic of China in the years shortly after its 1949 founding?

- What led to the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution and what were some of the results?

- What were some of the important aspects of the post-Mao policies under Deng Xiaoping?

- Alongside the increasing national wealth of the People’s Republic of China that Elshaikh outlines, what are some of the downsides of this economic growth?

- Can you connect aspects of China’s rise to the requirements of “neoliberal” policies that Elshaikh introduces in her essay on “International Institutions”?

Third read: evaluating and corroborating

- When we consider the “rise of China,” what parts of the story might be lost when we only look at economic growth? Elshaikh hints at these when she mentions growing inequality, environmental degradation, the persecution of minorities in China, and other factors. What happens when we tell the story of post-Mao China without mention of the 1989 protests and crackdown in Tiananmen Square, or 2019 events in Hong Kong?

- In terms of the “communities” frame narrative, how important do you think it is to a country’s sense of community to be wealthy and powerful on the world stage? How might increasing national wealth like that of the People’s Republic of China in recent decades change the ways people within the country view themselves and their national bonds?

- Deng Xiaoping referred to post-Mao reforms as “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Based on the evidence in this reading, is this just capitalism under one-party rule? Why or why not?

Rise of China

Introduction, china after world war ii, changing directions, china and the global economy, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Navigating complexity: globalization narratives in China and the West

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 10 January 2023

- Volume 4 , pages 351–366, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Anthea Roberts 1 &

- Nicolas Lamp ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6000-691X 2

2690 Accesses

3 Citations

12 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Relations between China and the West appear to be caught in a downward spiral. In the West, there is a widespread perception that China has unduly benefited from economic globalization, while in China, there appears to be increasing concern that the West is seeking to contain China’s rise. In this essay, we argue that the picture is more complex. We first discuss the highly varied ways in which China appears in Western narratives about economic globalization. We then sketch our understanding of how different narratives about globalization are playing out in China. Our approach highlights the diversity of perspectives within and between the West and China. How countries, companies, and individuals navigate this complexity depends not just on the rise and fall of narratives within the West and China, but also on how these narratives intersect and interact with each other.

Similar content being viewed by others

Toward an Understanding of a Global China: A Latin American Perspective

Chinese Strategic Narratives of Europe Since the European Debt Crisis

Not the Relationship You Would Expect: China, Sub-National Actors, and Structural Factors

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Complex issues look different from different perspectives. In Six Faces of Globalization: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why It Matters , we track the main narratives that have dominated Western debates about economic globalization in recent years. We argue that no one view holds the whole truth. Competing narratives identify different winners and losers of economic globalization while advancing different claims about whether these wins and losses are good or bad. However, a common theme, particularly since 2016, has been the growing pushback against the upbeat establishment account of economic globalization from narratives that focus on issues such the increasing class divide in Western societies, the West’s relative loss of economic power, and skyrocketing carbon emissions. In the West, globalization’s discontents have been growing in number and strength.

But the backlash against economic globalization in Western countries is not the whole story. Perspectives on globalization in countries outside the West differ significantly from the views that dominate Western media and political debates. As the Singaporean public intellectual and former diplomat Kishore Mahbubani notes, “for the majority of us, the past three decades—1990 to 2020—have been the best in human history,” as hundreds of millions lifted themselves out of poverty, and living standards soared across much of the developing world (Mahbubani 2018 ). Parag Khanna, the author of the book The Future Is Asian , concurs: “Western populist politics from Brexit to Trump haven’t infected Asia.... Rather than being backward-looking, navel-gazing, and pessimistic, billions of Asians are forward-looking, outward-orientated, and optimistic” (Khanna 2019 ). Globalization continues to have many supporters around the globe, particularly in Asia.

Where does China fit into this story? In this essay, we explore two aspects of this question: what role does China play in the Western narratives, and what role do these or other narratives play in China? We first explore the multiple ways China appears in different Western narratives—as a poster child, a villain, a scapegoat, a threat, and an indispensable nation. We then sketch our understanding of how different narratives about globalization are playing out in China, from the embrace of free trade as a driver of prosperity to increased concerns about the economic and security implications of rising geoeconomic tensions to a turn toward common prosperity instead of simple economic growth.

Our multi-narrative analysis highlights the diversity of perspectives not just within but also between the West and China—an approach that psychologists have found to be useful in understanding complex issues more holistically and in identifying potential pathways forward. Footnote 1 How countries, companies, and individuals navigate these complexities depends not just on the rise and fall of narratives within the West and China, but also on how these narratives intersect and interact with each other on the international plane and, in turn, influence domestic politics and policies in an iterative and recursive manner. Footnote 2 Narratives in the West about China can affect narratives in China about the West, which can in turn affect narratives in the West and so on. As relations between the West and China become more fraught, understanding this interplay becomes ever more important.

2 China’s role in western narratives about globalization

The relationship between the West and China appears to be caught in a downward spiral. The trade war initiated by former US President Trump has morphed into simmering hostility under the Biden administration. In quarrels over politically sensitive questions, such as an international inquiry into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic or relations with Taiwan, China has at times resorted to trade restrictions that its trading partners (such as Australia and the European Union) decry as economic coercion, prompting the lodging of legal challenges in the World Trade Organization and the development of anti-coercion instruments. The Chinese government’s decision not to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has further deepened estrangement between the two sides.

While an antagonistic view of the relationship has come to dominate public debates in the West, especially in the United States, just below the surface there are a variety of Western narratives that depict China’s role in the global economy in widely varying ways. Just as there is no one view of economic globalization, so too there is no one view of China and its role in the process. Examining these competing narratives not only provides a nuanced picture of Western debates but also highlights the contradictions and trade-offs that the West must navigate as it reassesses its relationship with China.

2.1 The establishment position: China as a poster child

Not long ago, the perhaps dominant view of China in the West was that it was a poster child for economic globalization’s successes. After all, here was a country that had managed to fulfill the aspiration shared by every “developing country” since that concept was first coined in the period of decolonization, namely, to follow the path trodden by today’s “developed countries” while at the same time contributing to the economic growth of its trading partners.

China stuck to that economic development path almost to a tee: it first attracted labor-intensive manufacturing industries, then moved up the value chain by acquiring advanced technologies, and finally evolved from imitator to innovator to attain technological leadership in important sectors, just as the United States and Germany had done in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the process, China created the conditions for hundreds of millions of its citizens to lift themselves out of destitution in just a few short decades—a reduction of poverty on a scale and speed unparalleled in human history. Even as globalization has started to lose its luster in the West, the proponents of what we call the pro-globalization “establishment” narrative keep pointing to this historic achievement as a knockout argument for its benefits.

However, China not only benefited its own citizens by opening up to the global economy: its manufacturing prowess and its status as the largest and fastest-growing market in the world in many industries also benefited producers, service providers, consumers, and entrepreneurs all over the world. The prices of manufactured goods, from fridges to solar panels to clothing, have fallen dramatically as hundreds of millions of Chinese workers have joined the global labor force, producing large savings for consumers and allowing businesses to source cheap inputs and products, boosting their profits. Many multinational companies also generate a significant share of their global revenues from their businesses in China, supporting employment and R&D in their home countries. Technological collaboration has led to scientific advances and business innovation. On this view, China’s integration into the world economy produced an economic bonanza that showcased the potential of globalization to make (almost) everyone better off.

2.2 The right-wing populist view: China as a villain

In the 2016 US presidential election, Donald Trump garnered support among US voters by painting China’s role in the global economy in starkly different terms. In his telling, China had achieved its astounding economic success not through hard work, ingenuity, and sacrifice, but by cheating its way around international trade rules. By using export subsidies to prop up its own companies, engaging in theft of intellectual property from Western companies, and undercutting labor and environmental standards, China had been able to “steal” the jobs of hard-working American manufacturing workers, leaving behind “rusted out factories” and devastated communities marked by unemployment and despair. In this view, Chinese workers had won at the expense of American workers.

This right-wing populist view, which continues to resonate among many American voters, discounts the benefits of trade with China, such as access to cheap products and to China’s large domestic market, and instead highlights the costs, which it measures first and foremost in terms of the decline of US manufacturing employment and the social ills that have followed in its wake. Proponents of this narrative argue for reshoring manufacturing in the hope of reviving communities in America’s rust belt so that they, rather than Chinese workers, may flourish again. In this view, China has taken advantage of America and left it weak; bringing back jobs in coal mines, steel smelters, and auto plants is vital to rebuilding the country’s industrial strength and making America great again.

2.3 Left-wing and corporate power concerns: China as a scapegoat

Many on the political left share concerns about the effects of China’s economic practices on US manufacturing employment, but there is also another prominent theme in left-wing narratives: the charge that those on the political right use China as a scapegoat for problems that are in large part the product of domestic policies within Western countries.

On this view, blaming China for the malaise of the middle and working classes in developed economies obscures the role that domestic policy failures have played in widening the gap between the rich and the poor in many Western countries. From underinvestment in schools and infrastructure to restrictive zoning laws that drive up the cost of housing, from anti-union legislation to regressive tax codes, it is largely domestic policies that rig the economy in favor of an entrenched elite.