- Key Differences

Know the Differences & Comparisons

Difference Between Negotiation and Assignment

On the other hand, assignment alludes to the transfer of ownership of the negotiable instrument, in which the assignee gets the right to receive the amount due on the instrument from the prior parties.

The most important difference between negotiation and assignment is that they are governed by different acts. To know more differences amidst the two types of transfers, take a read of the article below.

Content: Negotiation Vs Assignment

Comparison chart, definition of negotiation.

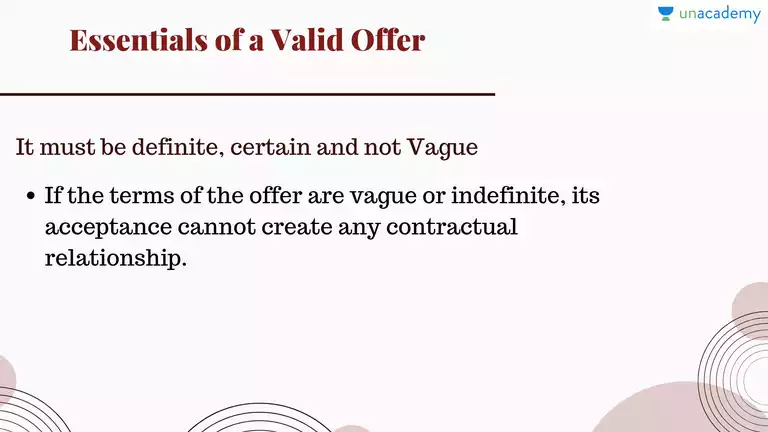

Negotiation can be described as the process in which the transfer of negotiable instrument, is made to any person, in order to make that person, the holder of the negotiable instrument. Therefore the negotiable instrument aims at transferring the title of the instrument to the transferee.

The term of negotiation for any person except maker, drawer or acceptor, until payment and in the case of the maker, drawer or acceptor, it should be until the due date. The two methods of negotiation are:

- By delivery : Negotiation is possible by mere delivery, in the case of bearer instrument, but that should be voluntary in nature.

- By endorsement and delivery : In the case of order instrument, there must be endorsement and delivery of the negotiable instrument. The delivery must be voluntary, with an intention of transferring the underlying asset, to the transferee to complete the negotiation.

Definition of Assignment

By the term assignment we mean, the transfer of contractual rights, ownership of property or interest, by a person, in order to realise the debt.

An assignment is a written transfer of rights or property, in which the assignor transfers the instrument to assignee with the aim of conferring the right on the assignee, by signing an agreement called assignment deed. Thus, the assignee is entitled to receive the amount due on the negotiable instrument, from the liable parties.

Key Differences Between Negotiation and Assignment

The primary differences between negotiation and assignment presented in the points below:

- The transfer of the negotiable instrument, by a person to another to make that person the holder of it, is known as negotiation. The transfer of rights, by a person to another, for the purpose of receiving the debt payment, is known as assignment.

- When it comes to regulation of negotiable instrument, negotiation governs the Negotiable Instrument, 1881, while the assignment is regulated by Transfer of Property Act, 1882.

- Negotiation can be effected by mere delivery in case of bearer instrument and, endorsement and delivery in case of order instrument.

- In the case of bearer instrument, the negotiation is done by mere delivery of the instrument, but in the case of bearer instrument, endorsement and delivery of the instrument must be effected. Conversely, the assignment is effected by written agreement to be signed by the transferor, both in the case of order and bearer instrument.

- In negotiation, the consideration is presumed, whereas, in the case of assignment, the consideration is proved.

- There is no requirement of transfer notice, in negotiation. On the contrary, notice of assignment is compulsory, so as to bind the debtor.

- In negotiation, the transferee has the right to sue the third party in his/her own name. As against, in the assignment, the assignee does not have any right to sue the third party, in his/her own name.

- In negotiation, there is no requirement of payment of stamp duty. Unlike, in the assignment, stamp duty must be paid.

In negotiation, the transfer of negotiable instrument, entitles the transferor, the right of a holder in due course. On the other extreme, in the assignment the title of the assignee, is a bit defective one, as it is subject to the title of assignor of the right.

You Might Also Like:

Girmay says

April 24, 2023 at 8:42 am

Your note is so good, and Like it.keep it up!.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Negotiation vs. Assignment: What's the Difference?

Key Differences

Comparison chart, participation, required skills, negotiation and assignment definitions, negotiation, are assignments always related to education, is negotiation always between two parties, what is negotiation in business, what does assignment mean in law, how important are communication skills in negotiation, can negotiation result in compromise, what happens if an assignment is not completed, what role does diplomacy play in negotiation, is an assignment always a solo task, what is an example of an assignment in a job, can an assignment be declined, what is an assignment brief, are assignments time-bound, can negotiation occur in personal situations, can an assignment be reassigned to someone else, is negotiation a skill, how does culture impact negotiation, how is an assignment evaluated, what is a negotiation strategy, are negotiations confidential.

Trending Comparisons

Popular Comparisons

New Comparisons

Negotiation vs. Assignment — What's the Difference?

Difference Between Negotiation and Assignment

Table of contents, key differences, comparison chart, skills required, legal implications, business impact, compare with definitions, negotiation, common curiosities, are there situations where assignments are not allowed, how does assignment differ from delegation, what is a common negotiation strategy, what legal documents are involved in an assignment, how can negotiation influence business relationships, can anyone perform an assignment of rights, can negotiation result in no agreement, what is the role of communication in negotiation, what types of rights can be assigned, how does assignment affect the original party, what is an example of a negotiation in international relations, is consent needed from the other party in an assignment, what are ethical considerations in negotiation, how do cultural differences impact negotiation, share your discovery.

Author Spotlight

Popular Comparisons

Trending Comparisons

New Comparisons

Trending Terms

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

What Is the Negotiation Process? 4 Steps

- 04 May 2023

Negotiation is part of daily life—whether buying a car, leasing property, aiming for higher compensation, raising capital for a startup, or making difficult decisions as an organizational leader.

“Enhancing your negotiation skills has an enormous payoff,” says Harvard Business School Professor Michael Wheeler in the online course Negotiation Mastery . “It allows you to reach agreements that might otherwise slip through your fingers. It allows you to expand the pie [and] create value, so you get more benefits from the agreements that you do reach. It also—in some cases—allows you to resolve small differences before they escalate into big conflicts.”

Here's an overview of the negotiation process’s four steps and how to gain the skills you need to negotiate successfully.

Access your free e-book today.

4 Steps of the Negotiation Process

1. Preparation

Before entering a negotiation, you need to prepare. There are several things to define, including your:

- Zone of possible agreement (ZOPA) : The range in which you and other parties can find common ground. To establish the ZOPA, think about your perspective and your counterpart’s. What do you each want and need? Where might you be willing to compromise?

- Best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA) : Your ideal course of action if an agreement isn’t possible. To determine your BATNA, consider alternatives that provide some of the value you aim to gain from the negotiation. In Negotiation Mastery , Wheeler gives the example that if you can't negotiate down a new car’s price, your BATNA may be to have your old car repaired.

- Walkaway: The line where ending negotiations is better than making a bad deal. Use your BATNA to determine your walkaway. At what point would the BATNA provide more value than a possible negotiated outcome? That’s your walkaway.

- Stretch goal: The best-case scenario for the negotiation’s outcome. It’s critical to give the negotiation a potential ceiling to gauge offers. In Negotiation Mastery, Wheeler recommends choosing a scenario that’s unlikely but not impossible; something that has a 10 percent chance of occurring.

Preparing in advance can improve your confidence, give you clear goals to work toward, and provide a strategy to base your approach on.

2. Bargaining

The second step, bargaining, is what most often comes to mind when thinking about negotiation. Yet, before discussions even begin, there are three levers that determine how the bargaining stage will play out:

- Engaging (the “who”): How do you engage with each other? Is this a friendly conversation, or do you fall into enemy territory?

- Framing (the “what”): How do you define the negotiation? For instance, is it a battle, partnership, or problem to be solved together?

- Norming (the “how”): How do you relate to one another? What behaviors are established that characterize the negotiation?

You typically define these levers in a negotiation’s first few minutes simultaneously. You negotiate the “who,” “what,” and “how” implicitly as the broader negotiation happens explicitly.

How do you and other parties enter the room? Do you greet each other warmly and make small talk, or is there immediate tension? How do you first mention the negotiation? What norms do you imply during the conversation?

Through these levers, you can establish the negotiation’s tone, which is vital as you head into it with someone who may greatly differ from you.

Your counterpart may have different preferences, expectations, risk tolerance, and time horizons. The bargaining stage is about creating value for both you and other parties despite your differences. It requires finding the ZOPA and working within that space to claim the value needed to make the negotiation worthwhile.

“There’s a fundamental tension between creating and claiming value,” Wheeler says in Negotiation Mastery . “Negotiation isn’t one or the other—it’s both at the same time.”

Related: 7 Negotiation Tactics That Actually Work

The third step in the negotiation process is closing—either coming to an agreement or ending the negotiation without reaching one.

How a negotiation closes depends on each party’s walkaway, BATNA, and ZOPA. It also relies on how you use engaging, framing, and norming to create a relationship with the other parties.

If you can’t reach a solution in the ZOPA, perhaps one or more parties decide to go for their BATNA instead. If you and the other parties create and claim value, you may strike a deal.

4. Learning from Your Experience

The final step of the negotiation process is possible to overlook but critical to your ongoing growth: Reflect on your experience. What went well? What went poorly, and why? How do you feel about the outcome?

No two negotiations are the same. The foundational elements can vary (such as the scenarios and people involved), as well as the finer details (for instance, people’s demeanors, emotions , walkaways, and BATNAs).

Reflecting on the process enables you to get to know yourself better as a negotiator and integrate your learnings into your next negotiation.

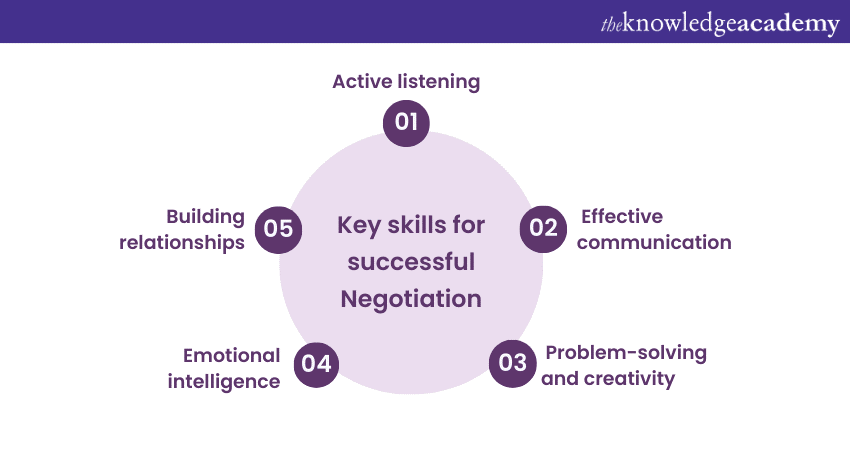

What Skills Do You Need for Successful Negotiation?

Even after learning about the negotiation process, negotiations can still feel intimidating. To gain confidence, it can help to understand the skills that great negotiators possess .

The best negotiators are strong communicators with high emotional intelligence . Developing your skills in those areas can help you form connections with counterparts and communicate goals. They can also enable you to craft a strategy and remain agile as a negotiation progresses.

“Great negotiators have keen analytical skills,” Wheeler says in Negotiation Mastery . “They assess the matter at hand and craft strategy that best fits those particular circumstances. They know that with negotiation strategy, one size doesn’t fit all.”

Finally, you must create value. As Wheeler puts it in the course: You know how to “expand the pie” rather than argue for a bigger slice—creating value for everyone involved while still achieving your goals.

To learn more about the skills needed for successful negotiation, check out the video below and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

How to Become a Better Negotiator

Familiarizing yourself with the negotiation process and what each step entails can demystify it and help you feel more comfortable.

The best way to improve your negotiation skills is through practice. This can take place in real life through interactions like determining a lease’s terms or asking for your desired salary in job interviews.

If you’d prefer to practice in a supportive learning environment, consider enrolling in an online negotiation course featuring virtual simulations.

In Negotiation Mastery , Wheeler leads you through negotiation practice by pairing you with other learners for mock negotiations. He then debriefs each scenario so you can reflect on it and integrate the insights into future negotiations.

Through thoughtful preparation and dedicated practice, you can strengthen your skills and create value in any negotiation.

Do you want to deepen your understanding of negotiation dynamics? Explore our eight-week online course Negotiation Mastery , one of our online leadership and management certificate programs . Not sure which course is right for you? Download our free flowchart .

About the Author

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is Negotiation?

How negotiations work.

- Where They Take Place

The Bottom Line

- Business Essentials

Negotiation: Definition, Stages, Skills, and Strategies

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/dhir__rajeev_dhir-5bfc262c46e0fb00260a216d.jpeg)

Investopedia / Ellen Lindner

The term negotiation refers to a strategic discussion intended to resolve an issue in a way that both parties find acceptable. Negotiations involve give and take, which means one or both parties will usually need to make some concessions.

Negotiation can take place between buyers and sellers, employers and prospective employees, two or more governments, and other parties. Here is how negotiation works and advice for negotiating successfully.

Key Takeaways

- Negotiation is a strategic discussion between two parties to resolve an issue in a way that both find acceptable.

- Negotiations can take place between buyers and sellers, employers and prospective employees, or the governments of two or more countries, among others.

- Successful negotiation usually involves compromises on the part of one or all parties.

Negotiations involve two or more parties who come together to reach some end goal that is agreeable to all those involved. One party will put its position forward, while the other will either accept the conditions presented or counter with its own position. The process continues until both parties agree to a resolution or negotiations break off without one.

Experienced negotiators will often try to learn as much as possible about the other party's position before a negotiation begins, including what the strengths and weaknesses of that position are, how to prepare to defend their positions, and any counter-arguments the other party will likely make.

The length of time it takes for negotiations to conclude depends on the circumstances. Negotiation can take as little as a few minutes, or, in more complex cases, much longer. For example, a buyer and seller may negotiate for minutes or hours for the sale of a car. But the governments of two or more countries may take months or years to negotiate the terms of a major trade deal.

Some negotiations require the use of a skilled negotiator such as a professional advocate, a real estate agent or broker, or an attorney.

Examples of Negotiations

Negotiating can take place between individuals, businesses, governments, and in any other situation where two parties have competing interests. Here are two everyday examples:

Say you plan to buy a new SUV but don't want to pay the full manufacturer's suggested retail price (MSRP). In that case, you might offer what you consider a fair price. The dealer can accept your offer or counter with another price figure. If you have good negotiating skills, you may be able to drive the price down to a level where you're happy and the dealer is still able to walk away with a profit, albeit a slimmer one.

Or, suppose you've been offered a new job but don't consider the salary sufficient. An employer's first compensation offer is often not its best possible offer, so it may have some room to negotiate. In fact, a 2016 survey by the CareerBuilder website found that 73% of employers were open to negotiating a starting salary with job seekers. And if higher pay isn't a possibility, the employer may be willing to offer something additional, such as more vacation time or better benefits.

In both of these examples—as in most successful negotiations—both parties have made compromises, while also achieving their principal goals.

A 2022 study by Fidelity Investments found that while 58% of workers had accepted their employer's initial offer, 85% of those who attempted to negotiate got at least some of what they asked for.

The Stages of the Negotiation Process

Regardless of what you're negotiating over or with whom, negotiation usually involves several distinct steps.

Preparation

Before negotiations begin, there are a few questions it helps to ask yourself. Those include:

- What do you hope to gain, ideally?

- What are your realistic expectations?

- What compromises are you willing to make?

- What happens if you don't reach your end goal?

Preparation can also include finding out as much as you can about the other party and their likely point of view. In the case of the SUV negotiation above, you could probably find out how much room the dealer has to bargain by looking up actual sales prices for that vehicle online.

Also, marshal any facts that will help you make a persuasive case. If you're negotiating for a new job or a raise at work, for instance, come armed with concrete examples of your accomplishments, including hard numbers if possible. Consider bringing testimonials from satisfied clients and/or coworkers if that will buttress your case.

Many experienced negotiators consider preparation to be the single most important step in the entire process.

Exchanging Information

Once you're prepped for the negotiation, you're ready to sit down with the other party. If they're smart, they have probably prepared themselves, as well. This is the point at which both sides will present their initial positions in terms of what they want and are willing to give in return.

Being able to clearly articulate your wishes is critical to the negotiation process. You may not get everything on your wish list, but the other party, if they want to reach a deal, will have a better idea of what it might take to make that happen. You will have a better idea of their position, and where they might be willing to bend, as well.

Now that both parties have laid out their case, you're ready to start bargaining.

An important key to this step is to hear the other party out and refrain from being dismissive or argumentative. Successful negotiating involves a little give and take on both sides, and an adversarial relationship is likely to be less effective than a collegial one.

Also bear in mind that a negotiation can take time, so try not to rush the process or allow yourself to be rushed.

Closing the Deal

Once both parties are satisfied with the results, it's time to end the negotiations. The next step may be in the form of a verbal agreement or written contract. The latter is usually a better idea as it clearly outlines the position of each party and can be enforced if one party doesn't live up to their end of the bargain.

Tips for Successful Negotiating

Some people may be born negotiators, but many of us are not. Here are a few tips that can help.

- Justify Your Position. Don't just walk into negotiations without being able to back up your position. Bring information to show that you've done your research and you're committed to reaching a deal.

- Put Yourself in Their Shoes. Remember that the other side has things it wants out of the deal, too. What can you offer that will help them reach their goal (or most of it) without giving away more than you want to or can afford to?

- Keep Your Emotions in Check. It's easy to get caught up in the moment and be swayed by your personal feelings, especially ones like anger and frustration. But don't let your emotions cause you to lose sight of your goal.

- Know When to Walk Away. Before you begin the negotiating process, it's a good idea to know what you'll accept as a bare minimum and when you'd rather walk away from the table than continue to bargain. There is no use trying to reach a deal if both sides are hopelessly dug in. Even if you don't want to end negotiations entirely, pausing them can give everyone involved a chance to regroup and possibly return to the table with a fresh perspective.

What Makes a Good Negotiator?

Some of the key skills of a good negotiator are the ability to listen, to think under pressure, to clearly articulate their point of view, and to be willing to compromise, within reason.

What Is ZOPA?

ZOPA is an acronym from the business world. It stands for zone of possible agreement . ZOPA is a way of visualizing where the positions of the parties to a negotiation overlap. It is within that zone that compromises can be reached.

What Is BATNA?

BATNA is another acronym from the world of business, meaning best alternative to a negotiated agreement . It refers to the next course of action a negotiator may take if a negotiation fails to arrive at a satisfactory conclusion. Veteran negotiators often go into a negotiation knowing what their likely BATNA would be, just in case.

Negotiating is essential part of day-to-life, the business world, and international affairs. Regardless of what you're negotiating, being a successful negotiator means knowing what you want, trying to understand the other party's (or parties') position, and compromising if necessary. A successful negotiation leaves everyone satisfied that they have gotten a deal they can live with.

CareerBuilder. " 73% of Employers Would Negotiate Salary, 55% of Workers Don't Ask ."

Fidelity Investments. " 2022 Career Assessment Study ," Page 3.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-950722746-f34efb48665948babecdd411dc991e43.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 9 min read

Negotiation Overview

A quick guide to negotiating.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Negotiation is a skill that everyone develops from an extremely young age, and everyone is a skilled negotiator by the time they can talk. On a business level, negotiation is often a highly complex and sophisticated process. Unfortunately, many people get stuck in a particular way of thinking about how to negotiate, limiting their efficiency and capabilities. Negotiation is a key business skill that needs to be developed through training and practice.

What Is Negotiation?

Negotiation is, at its simplest, a discussion intended to produce an agreement. It is the process of bargaining between two or more interests. [1]

The primary goal of negotiation should be to achieve a mutually acceptable deal, which accomplishes the objectives of the negotiation, without making the other party walk away or damaging a valuable relationship. This often requires substantial preparation, informed negotiation, compromise, and flexibility, depending on the situation. Some of the business situations which might require negotiation skills include:

- determining the details of a new commercial contract

- agreeing pay between management and a trades union

- bringing in new working practices

- changing employees' contractual arrangements

- arranging funding from a governing body

- agreeing next year's budgets

- working out the details of a major new project with colleagues

- agreeing objectives with team members

Stages of Negotiation

Most negotiations can be broken down into six main stages:

1. Preparation

Achieving objectives in the negotiation will be much easier if negotiators are fully prepared. A successful negotiator will ensure that they:

- are fully briefed on the subject matter of the negotiation

- are clear about their objectives and what they are trying to achieve

- have worked out their tactics and how best to put their case

2. Initial Exchanges

At the beginning of the negotiation, both parties will be sizing each other up. Both will be trying to find out and understand the other's position and requirements. The atmosphere in which the negotiation will be conducted should begin to form, and issues that need to be resolved later will emerge. At this stage it is probably wise to encourage the other side to say as much as possible, to listen a lot and not reveal too much too soon.

In this phase the negotiation begins to get serious, as both parties start to put forward their own offers of what they want to get out of the negotiation. During this stage, a number of different things will be happening:

- both sides will be searching for common ground, which could form the basis of an agreement

- both sides will be exploring possible areas of compromise, where ground could be conceded if necessary

- sticking points or objections, which will need to be resolved later, will begin to emerge

4. Bargaining

This is often the crunch-point of the negotiation, as the parties start to trade and exchange in the search for an agreement. Both parties will be aware of the limits they have set themselves on each of the negotiable issues, and therefore which issues they can concede and which they need to hold out for. This is the point at which the difficult issues will need to be resolved and is consequently a vulnerable point at which the negotiation could break down. There are many tools and techniques (such as BATNA and game theory ) that have been developed to determine bargaining positions when negotiating.

5. Securing Agreement

As the two parties arrive at their final positions, the negotiation could still break down. There are two common reasons for such a failure:

- potential loss of face in coming to a sensible compromise solution

- the last-minute introduction of a completely new set of conditions

In either of these situations, a final, small, unrelated concession, as a gesture of goodwill, may be necessary to secure the agreement. In order to reach a mutually satisfactory conclusion to the negotiation, care needs to be taken to ensure that:

- the best time to bring the negotiation to a conclusion is chosen

- a 'final' proposal is put forward only if it is really meant and if the reasons why no further movement is available are justified

- the final agreement is comprehensive, unambiguous and clearly understood by each party

6. Implementation

A deal is only successful if it is workable. A successful negotiator is one who has a sound track record of successfully implementing the agreement that has been reached. The implementation plan will need to incorporate the following:

- a comprehensive list of necessary activities

- timescales or deadlines for each of the activities

- a clear understanding of who will be responsible for carrying out each action

- the resources and information that will be necessary to carry out the activities

- who else needs to be involved or informed

- arrangements for coordination and monitoring

- how to review the implementation and evaluate the effectiveness of the negotiated solution

- who should be informed of this outcome

Negotiation Styles

While successful negotiators tend to do many of the same things, they often go about it in different ways. This is because there are a number of different negotiation styles. The style a negotiator adopts will depend upon many things, including:

- their knowledge of the subject matter which is under negotiation

- their personality

- what they know of the other party, and how much they trust them

- whether it is a one-to-one or a team negotiation

- the national or regional culture of the individual(s) involved

- the type of negotiation and its level of importance

- how much time is available for the process to take place

- whether the negotiation is a 'one-off' or one in a regular series of events

A simple, but effective, classification of negotiators is whether they are task-oriented or people-oriented . The former will pursue their objectives relentlessly, will be tough, aware of tactical ploys and have little concern about the effect they have on others. The latter, on the other hand, are highly concerned about the wellbeing of others, which can mean they are more likely to understand the emotional aspects of the negotiation and build rapport. However, negotiators who favor the people-oriented approach can put insufficient emphasis on business goals, making them a 'soft touch' for negotiators who favor the task-oriented approach. In reality though, it is not quite so simple: there are a number of intermediate points in between the two extremes. Bill Scott has identified three main styles of negotiator: [2]

- The fighter: highly task oriented and likely to go flat out to achieve objectives

- The collaborator: attempts to get everything into the open, is prepared to confront issues and be innovative in order to make a deal.

- The compromiser: tends to make significant use of compromise in order to settle deals.

The significance of negotiation styles is threefold:

- To be successful we must recognize the negotiating style of the other party and work out what impact this is likely to have on us.

- We must work out what our own natural negotiating style is and whether the combination of the two styles can lead to problems.

- We should decide how we could adjust our own negotiating style, if necessary, in order to cope with, and succeed in, the situation with which we will be faced.

Negotiation Tools and Techniques

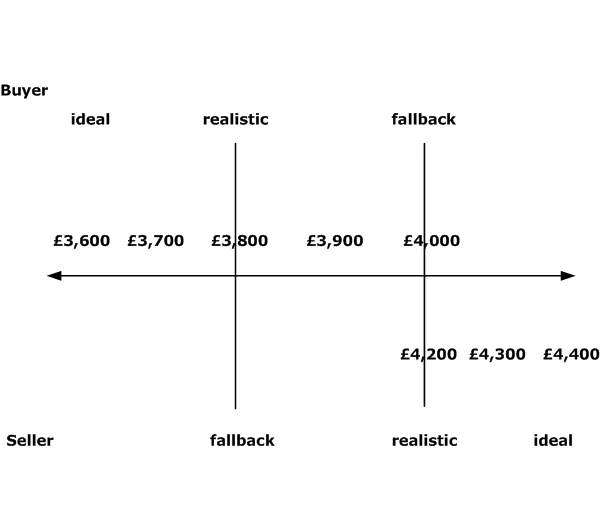

Many tools and techniques have been developed to determine bargaining positions when negotiating. One of these advises negotiators to work out three negotiating positions in advance:

- Ideal: the best possible outcome

- Realistic: what they expect to achieve

- Fallback: minimum what they will accept.

This strategy, also known as BATNA (Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement) was developed by Fisher and Ury as part of the Harvard Negotiation Project at Harvard Law School. [3] Negotiators should also estimate what they think the negotiating positions of the other party will be. If there are overlapping areas, bargaining and agreement may be possible. For example, a car buyer would ideally like to pay £3,600 for a new car but, realistically, expects to have to pay £3,800, and as a fallback will pay no more than £4,000. The car salesperson will also have equivalent ideal, realistic and fallback positions:

As the diagram shows, there is a small degree of negotiating space between the two parties in this situation. The price where the two parties will find their compromise, if one is to be reached, is between £3,900 and £4,000. One of the major developments for 20th century negotiation was that of game theory. Game theory is strategic interaction between two or more players, who make decisions and negotiate while trying to anticipate the others' actions and reactions. [4] Techniques such as game theory, or the use of asymmetric information , give a trained negotiator an edge over someone relying on general life experience. [5] Game theory has become a useful negotiation tool for mapping out potential scenarios and assessing the options that both the parties face.

Qualities of a Successful Negotiator

Successful negotiations require an atmosphere of calm, reasonable discussion. This can often be difficult, as negotiations which have taken a significant amount of time and energy to prepare for, can easily become emotionally charged events. Key to thriving in these situations is the ability to distinguish between the issues involved in the negotiation, and the relationship with the other party. Discussing issues as a matter of mutual, legitimate concern can diffuse emotional aspects of a negotiation, and produce a stronger long-term relationship between the two parties. Negotiating to solve problems helps participants move away from an adversarial approach, aiding the search for a solution through co-operative work.

That is not to say that there is no place for playing the negotiation with specific techniques to gain an advantage (the other party is most likely doing the same), but these must be carefully considered, and the circumstances judged perfectly in order to avoid permanently damaging a relationship.

Pragmatism is an essential quality for a negotiator, with good, objective judgment required at all times. The negotiator needs to be able to judge precisely when to make concessions, when to play hardball, or when to back away from a deal. Negotiating formally is a skill that needs to be developed through training and practice. Individuals may well have been informally negotiating for their whole lives, but there are aspects of a formal negotiation, mentioned above, which need time, preparation and thought to master.

[1] http://www.thefreedictionary.com/negotiation (February 2009).

[2] Bill Scott, The Skills of Negotiating (Jaico Publishing House, 2005).

[3] Roger Fisher and William Ury, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In , 2nd Ed (Penguin Putnam, 2008).

[4] In the 1950s, work on game theory really began to gather steam, specifically the work by John Nash , proving the existence of an equilibrium (the Nash Equilibrium), for non-co-operative games, and mathematician Albert Tucker , who developed the example of the Prisoner’s Dilemma . This model was an example of a non-zero-sum game i.e. a game that allows for collaboration, as opposed to a zero-sum game, a win-lose situation, in which a gain for one party means an equal loss for the other.

[5] Asymmetric information exchange occurs when one of the parties involved in a negotiation has more information concerning the process than the other party.

Join Mind Tools and get access to exclusive content.

This resource is only available to Mind Tools members.

Already a member? Please Login here

Team Management

Learn the key aspects of managing a team, from building and developing your team, to working with different types of teams, and troubleshooting common problems.

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

ADHD in the Workplace

Team Briefings

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Swot analysis.

Understanding Your Business, Informing Your Strategy

How to Build a Strong Culture in a Distributed Team

Establishing trust, accountability and work-life balance

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Head or heart - how personality affects problem-solving.

This Article Looks at How Personality Preferences Affect the Problem-Solving Process

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

What is Negotiation?

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- Communication Skills

- Emotional Intelligence

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

- Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Negotiation in Action

- Transactional Analysis

- Avoiding Misunderstandings in Negotiations

- Peer Negotiation

- Negotiating Within Your Job

- Negotiation and Persuasion in Personal Relationships

- Negotiation Across Cultures

- Persuasion and Influencing Skills

- Developing Persuasion Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Negotiation is a method by which people settle differences. It is a process by which compromise or agreement is reached while avoiding argument and dispute.

In any disagreement, individuals understandably aim to achieve the best possible outcome for their position (or perhaps an organisation they represent). However, the principles of fairness, seeking mutual benefit and maintaining a relationship are the keys to a successful outcome.

Specific forms of negotiation are used in many situations: international affairs, the legal system, government, industrial disputes or domestic relationships as examples. However, general negotiation skills can be learned and applied in a wide range of activities. Negotiation skills can be of great benefit in resolving any differences that arise between you and others.

Stages of Negotiation

In order to achieve a desirable outcome, it may be useful to follow a structured approach to negotiation. For example, in a work situation a meeting may need to be arranged in which all parties involved can come together.

The process of negotiation includes the following stages:

- Preparation

- Clarification of goals

- Negotiate towards a Win-Win outcome

- Implementation of a course of action

1. Preparation

Before any negotiation takes place, a decision needs to be taken as to when and where a meeting will take place to discuss the problem and who will attend. Setting a limited time-scale can also be helpful to prevent the disagreement continuing.

This stage involves ensuring all the pertinent facts of the situation are known in order to clarify your own position. In the work example above, this would include knowing the ‘rules’ of your organisation, to whom help is given, when help is not felt appropriate and the grounds for such refusals. Your organisation may well have policies to which you can refer in preparation for the negotiation.

Undertaking preparation before discussing the disagreement will help to avoid further conflict and unnecessarily wasting time during the meeting.

2. Discussion

During this stage, individuals or members of each side put forward the case as they see it, i.e. their understanding of the situation.

Key skills during this stage include questioning , listening and clarifying .

Sometimes it is helpful to take notes during the discussion stage to record all points put forward in case there is need for further clarification. It is extremely important to listen, as when disagreement takes place it is easy to make the mistake of saying too much and listening too little. Each side should have an equal opportunity to present their case.

3. Clarifying Goals

From the discussion, the goals, interests and viewpoints of both sides of the disagreement need to be clarified.

It is helpful to list these factors in order of priority. Through this clarification it is often possible to identify or establish some common ground. Clarification is an essential part of the negotiation process, without it misunderstandings are likely to occur which may cause problems and barriers to reaching a beneficial outcome.

4. Negotiate Towards a Win-Win Outcome

This stage focuses on what is termed a 'win-win' outcome where both sides feel they have gained something positive through the process of negotiation and both sides feel their point of view has been taken into consideration.

A win-win outcome is usually the best result. Although this may not always be possible, through negotiation, it should be the ultimate goal.

Suggestions of alternative strategies and compromises need to be considered at this point. Compromises are often positive alternatives which can often achieve greater benefit for all concerned compared to holding to the original positions.

5. Agreement

Agreement can be achieved once understanding of both sides’ viewpoints and interests have been considered.

It is essential to for everybody involved to keep an open mind in order to achieve an acceptable solution. Any agreement needs to be made perfectly clear so that both sides know what has been decided.

6. Implementing a Course of Action

From the agreement, a course of action has to be implemented to carry through the decision.

See our pages: Strategic Thinking and Action Planning for more information.

Failure to Agree

If the process of negotiation breaks down and agreement cannot be reached, then re-scheduling a further meeting is called for. This avoids all parties becoming embroiled in heated discussion or argument, which not only wastes time but can also damage future relationships.

At the subsequent meeting, the stages of negotiation should be repeated. Any new ideas or interests should be taken into account and the situation looked at afresh. At this stage it may also be helpful to look at other alternative solutions and/or bring in another person to mediate.

See our page on Mediation Skills for more information.

Informal Negotiation

There are times when there is a need to negotiate more informally. At such times, when a difference of opinion arises, it might not be possible or appropriate to go through the stages set out above in a formal manner.

Nevertheless, remembering the key points in the stages of formal negotiation may be very helpful in a variety of informal situations.

In any negotiation, the following three elements are important and likely to affect the ultimate outcome of the negotiation:

Interpersonal Skills

All negotiation is strongly influenced by underlying attitudes to the process itself, for example attitudes to the issues and personalities involved in the particular case or attitudes linked to personal needs for recognition.

Always be aware that:

- Negotiation is not an arena for the realisation of individual achievements.

- There can be resentment of the need to negotiate by those in authority.

- Certain features of negotiation may influence a person’s behaviour, for example some people may become defensive.

The more knowledge you possess of the issues in question, the greater your participation in the process of negotiation. In other words, good preparation is essential.

Do your homework and gather as much information about the issues as you can.

Furthermore, the way issues are negotiated must be understood as negotiating will require different methods in different situations.

Good interpersonal skills are essential for effective negotiations, both in formal situations and in less formal or one-to-one negotiations.

These skills include:

Effective verbal communication. See our pages: Verbal Communication and Effective Speaking .

Listening. See our pages on Active Listening and Tips for Effective Listening .

Reducing misunderstandings is a key part of effective negotiation. See our pages: Reflection , Clarification and The Ladder of Inference for more information.

Rapport Building. Build stronger working relationships based on mutual respect. See our pages: Building Rapport and How to be Polite .

Problem Solving. See our section on effective Problem Solving .

Decision Making. Learn some simple techniques to help you make better decisions, see our section: Decision Making .

Assertiveness. Assertiveness is an essential skill for successful negotiation. See our page: Assertiveness Techniques for more information.

Dealing with Difficult Situations. See our page: Communicating in Difficult Situations for some tips and advice to make difficult communications, easier.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

Conflict Resolution and Mediation

Learn more about how to effectively resolve conflict and mediate personal relationships at home, at work and socially.

Our eBooks are ideal for anyone who wants to learn about or develop their interpersonal skills and are full of easy-to-follow, practical information.

Continue to: Negotiation in Action Negotiating Within Your Job

See also: Transactional Analysis Assertiveness Peer Negotiation Skills

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What’s Your Negotiation Strategy?

- Jonathan Hughes

- Danny Ertel

Many people don’t tackle negotiations in a proactive way; instead, they simply react to moves the other side makes. While that approach may work in a lot of instances, complex deals demand a much more strategic approach.

The best negotiators look beyond their immediate counterparts to see if other constituencies have a stake in the deal’s outcome or value to contribute; rethink the scope and timing of talks; and search for connections across multiple deals. They also get creative about the process and framing of negotiations, ditching the binary thinking that can lock negotiators into unproductive zero-sum postures.

Applying such strategic techniques will allow dealmakers to find novel sources of leverage, realize bigger opportunities, and achieve outcomes that maximize value for both sides.

Here’s how to avoid reactive dealmaking

Idea in Brief

The challenge.

Negotiators often mainly react to the other side’s moves. But for complex deals, a proactive approach is needed.

The Strategy

Strategic negotiators look beyond their immediate counterpart for stakeholders who can influence the deal. They intentionally control the scope and timing of talks, search for novel sources of leverage, and seek connections across multiple deals.

Tactical negotiating can lock parties into a zero-sum posture, in which the goal is to capture as much value from the other side as possible. Well-thought-out strategies suppress the urge to react to moves or to take preemptive action based on fears about the other side’s intentions. They lead to deals that maximize value for both sides.

When we advise our clients on negotiations, we often ask them how they intend to formulate a negotiation strategy. Most reply that they’ll do some planning before engaging with their counterparts—for instance, by identifying each side’s best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA) or by researching the other party’s key interests. But beyond that, they feel limited in how well they can prepare. What we hear most often is “It depends on what the other side does.”

- JH Jonathan Hughes is a partner at Vantage Partners, a global consultancy specializing in strategic partnerships and complex negotiations.

- Danny Ertel is a partner at Vantage Partners, a global consultancy specializing in strategic partnerships and complex negotiations.

Partner Center

Negotiation vs. Assignment: Know the Difference

Key Differences

Comparison Chart

Nature of process, involvement of parties, common contexts, success factors, negotiation and assignment definitions, negotiation, repeatedly asked queries, what is the primary goal of negotiation, can an assignment be revoked, is an assignment legally binding, what skills are essential for successful negotiation, are negotiations confidential, how important is communication in negotiation, is consent needed for an assignment, does negotiation always involve compromise, can anyone be given an assignment, does an assignment require acceptance by the assignee, what happens if an assignment is not completed, can negotiation occur in personal contexts, can an assignment be conditional, what are common obstacles in negotiation, who can make an assignment, can a third party be involved in an assignment, how is success measured in negotiation, how does culture impact negotiation, what is the difference between negotiation and debate, what legal considerations apply to an assignment, share this page.

Popular Comparisons

Trending Comparisons

Featured Comparisons

New Comparisons

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Negotiation and bargaining.

- Wolfgang Steinel Wolfgang Steinel Leiden University, Department of Psychology

- and Fieke Harinck Fieke Harinck Leiden University, Department of Psychology

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.253

- Published online: 28 September 2020

Bargaining and negotiation are the most constructive ways to handle conflict. Economic prosperity, order, harmony, and enduring social relationships are more likely to be reached by parties who decide to work together toward agreements that satisfy everyone’s interests than by parties who fight openly, dominate one another, break off contact, or take their dispute to an authority to resolve.

There are two major research paradigms: distributive and integrative negotiation. Distributive negotiation (“bargaining”) focuses on dividing scarce resources and is studied in social dilemma research. Integrative negotiation focuses on finding mutually beneficial agreements and is studied in decision-making negotiation tasks with multiple issues. Negotiation behavior can be categorized by five different styles: distributive negotiation is characterized by forcing, compromising, or yielding behavior in which each party gives and takes; integrative negotiation is characterized by problem-solving behavior in which parties search for mutually beneficial agreements. Avoiding is the fifth negotiation style, in which parties do not negotiate.

Cognitions (what people think about the negotiation) and emotions (how they feel about the negotiation and the other party) affect negotiation behavior and outcomes. Most cognitive biases hinder the attainment of integrative agreements. Emotions have intrapersonal and interpersonal effects, and can help or hinder the negotiation. Aspects of the social context, such as gender, power, cultural differences, and group constellations, affect negotiation behaviors and outcomes as well. Although gender differences in negotiation exist, they are generally small and are usually caused by stereotypical ideas about gender and negotiation. Power differences affect negotiation in such a way that the more powerful party usually has an advantage. Different cultural norms dictate how people will behave in a negotiation.

Aspects of the situational context of a negotiation are, for example, time, communication media, and conflict issues. Communication media differ in whether they contain visual and acoustic channels, and whether they permit synchronous communication. The richness of the communication channel can help unacquainted negotiators to reach a good agreement, yet it can lead negotiators with a negative relationship into a conflict spiral. Conflict issues can be roughly categorized in scarce resources (money, time, land) on the one hand, and norms and values on the other. Negotiation is more feasible when dividing scarce resources, and when norms and values are at play in the negotiation, people generally have a harder time to find agreements, since the usual give and take is no longer feasible. Areas of future research include communication, ethics, physiological or hormonal correlates, or personality factors in negotiations.

- negotiation

- negotiation style

- multiparty negotiations

- motivated information processing

Bargaining and negotiation, the “back-and-forth communication designed to reach an agreement when you and the other side have some interests that are shared and others that are opposed” (Fisher, Ury, & Patton, 2012 , p. xxv), are the most constructive ways to handle conflict. Economic prosperity, order, harmony, and enduring social relationships are more likely to be reached by parties who decide to work together toward agreements that satisfy everyone’s interests than by parties who fight openly, dominate one another, break off contact, or take their dispute to an authority to resolve (Lewicki, Saunders, & Barry, 2021 ).

Negotiation and bargaining are common terms for discussions aimed at reaching agreement in interdependent situations, that is, in situations where parties need each other in order to reach their goals. While both terms are often used interchangeably, Lewicki et al. ( 2021 ) distinguish between distributive bargaining and integrative negotiation. Distributive refers to situations where a fixed amount of a resource (e.g., money or time) is divided, so that one party’s gains are the other party’s losses. In such win–lose situations, like haggling over the price of a bicycle, bargainers usually take a competitive approach, trying to maximize their outcomes. Integrative refers to situations where the goals and objectives of both parties are not mutually exclusive or connected in a win–lose fashion. In such more complex situations that usually involve several issues (rather than the distribution of only one resource), interdependent parties try to find mutually acceptable solutions and may even search for win–win solutions, that is, they cooperate to create a better deal for both parties (Lewicki et al., 2021 ).

The distinction between bargaining and negotiation reflects the research tradition, where bargaining has largely been investigated from an economic perspective, focusing on the dilemma between immediate self-interest and benefit to a larger collective. Negotiation has mostly been investigated from the perspective of social psychology, organizational behavior, management, and communication science and has mainly focused on the effect on, and behavior and cognition of people in richer social situations.

Research Paradigms

Negotiation research has applied various paradigms. Game-theoretic approaches, such as the Prisoners’ Dilemma and related matrix games, in which simultaneous choices together influence two parties’ outcomes, explore how people handle the conflict between immediate self-interest and longer-term collective interests (see Van Lange, Joireman, Parks, & Van Dijk, 2013 , for a review). A paradigm to investigate behavior in purely distributive settings is the Ultimatum Bargaining Game (Güth, Schmittberger, & Schwarze, 1982 ). It models the end phase of a negotiation: one player offers a division of a certain resource (e.g., €100 split 50–50), and the other player can either accept, in which case the offer is carried out, or reject, in which case both players get nothing. Studies in ultimatum bargaining have consistently shown that even in distributive one-shot interactions, bargainers not only try and maximize their own outcomes, but are also driven by other-regarding preference, can reject unfair offers (Güth & Kocher, 2014 ), are concerned about being and appearing fair (Van Dijk, De Cremer, & Handgraaf, 2004 ), and are affected by their own and a counterpart’s emotions (Lelieveld, Van Dijk, Van Beest, & Van Kleef, 2012 ).

While ultimatum bargaining is a context-free simulation of a distributive negotiation, integrative negotiation has predominantly been studied in richer contexts that simulate real-life decision-making. Research has largely relied on negotiation simulations to identify and analyze participants’ behaviors and measured economic outcomes (Thompson, 1990 ). Field studies on negotiation behavior have been conducted to a much smaller extent (Sharma, Bottom, & Elfenbein, 2013 ).

The remainder of this article will first describe the strategy and planning for negotiations, and the behavior and outcomes of negotiations. It will then cover research on factors that affect behavior and outcome in integrative negotiation, starting with intrapersonal factors, such as cognitions and emotions. Then aspects of the social context, such as gender, power, culture, and group constellations will be covered, before moving on to aspects of the situational context, such as time, communication media, and conflict issues, and concluding with some emerging lines of research.

Negotiation Preparation and Goals

The goal of negotiations.

The goal of negotiations may be deal-making or dispute resolution. Before entering the actual negotiation, well-prepared negotiators define the goals they want to achieve and the key issues they need to address in order to achieve these goals (Lewicki et al., 2021 ). Deal-making (e.g., a student selling his bike) involves two or more parties who have some common goals (e.g., transferring ownership of the bike from the seller to the buyer) and some incompatible goals (receiving a high price vs. paying a low price), and try and negotiate an agreement that is better for both than the status quo (the seller keeping the bike) or any alternative agreements with third parties (e.g., selling the bike to someone else or buying a different bike). Negotiation with the aim of dispute resolution (e.g., a student complaining about the noise a flatmate makes) occurs when parties who are dependent on each other (e.g., because they share a flat) realize that they are blocking each other’s goal attainment (preparing for an exam vs. listening to punk rock) and negotiate what can be done to solve the problem.

Preparing for Negotiations

Negotiators are advised to define their alternatives, targets, and limits, and to prepare an opening offer (Lewicki et al., 2021 ). Figure 1 shows the key points in the example of a student selling his bike to another student. The target point is the point at which each negotiator aspires to reach a settlement. For example, the seller hopes to sell his bike for €280, and the buyer hopes to buy it for €190. By making opening offers beyond their targets, negotiators create leeway for concessions while pursuing their goal. In the bike example, the seller has prepared an opening offer (e.g., an asking price) of €320, while the buyer planned to start the negotiation by offering to pay €150. Well-prepared negotiators define their limits before entering a negotiation by setting a resistance point, that is, the price below which a settlement is not acceptable (Lewicki et al., 2021 ). If, for example, the seller would accept any price above €200 and the buyer is willing to pay up to €280, it is likely that they settle on a price somewhere in this range. This zone between the two parties’ resistance points is called zone of potential agreements (ZOPA; Lewicki et al., 2021 ).

Figure 1. Overview of Key Points in Negotiation Preparation (Example).

Well-prepared negotiators are aware of the alternative they have to reaching a deal in the upcoming negotiation, in particular of their best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA; Fisher et al., 2012 ). As the quality of a negotiator’s BATNA defines their need to reach an agreement, and thus their dependency on their counterpart, attractive BATNAs increase a negotiator’s power.

Deal-making and dispute resolution differ in the way parties are dependent on each other: in deal-making, both parties can have independent alternatives that they can unilaterally decide to turn to instead of reaching a deal (the buyer may find a different seller, and the seller might find another potential buyer). Disputes that occur between parties who share a common fate, like flatmates, parents of a child, co-owners of a company, or different ethnic or religious groups living on the same territory, can only be solved by the parties working together. The alternative to not solving a dispute for both disputants therefore is conflict escalation (e.g., sabotaging the stereo installation), a victory for one (and a grudge for the other) or a stalemate in which neither party is willing to abandon their position. These alternatives usually do not last or they damage the relationship between the parties.

Negotiation Behavior and Outcomes

Negotiation is communication. Parties communicate either directly, or through agents, and exchange offers and counteroffers, usually alongside arguments, questions, proposals, cooperative statements, commitments, threats, and so on. How people behave in negotiations is influenced by their preferred negotiation style. The Dual Concern Model (Blake & Mouton, 1964 ; Pruitt & Carnevale, 1993 ; Rubin, Pruitt, & Kim, 1994 ) describes how two types of concerns jointly determine negotiation styles. These two concerns, which can both range in intensity from low (i.e., indifference) to high, are the concern about a party’s own outcome and the concern about the other’s outcome, as displayed in Figure 2 . Importantly, the model does not postulate concern about a party’s own interests (also called concern for self or self-interest) and concern about the other’s outcomes (also called concern for other or cooperativeness) as opposite ends of one scale, but rather as two dimensions that can vary independently.

Figure 2. Dual-Concern Model.

Parties with a low concern for self and for other will probably be avoiding negotiations, leaving the other party without an agreement. Parties with a high concern for self and a low concern for other are likely to use forcing behaviors, while aiming to achieve the own goals by imposing a solution onto the other. Forcing (also called contending), like using threats or other forms of pressure, is detrimental to the relationship with the other party, and can lead parties into a conflict spiral, especially when they are similarly powerful (Rubin et al., 1994 ).

Parties with a low concern for self and a high concern for other are likely to engage in yielding . Yielding (also called accommodating), like making large concessions or accepting the other party’s demands, is often the strategy of parties who feel weaker than their counterpart or have a strong need for harmony. This can lead into a dynamic of exploitation. It is less effective when negotiating important issues, since yielding on important issues will leave the yielding party dissatisfied with the outcome. Parties with an intermediate concern about both parties’ outcomes are likely to use compromising , a “meet-in-the-middle” approach often considered a democratic and fair way of solving conflicts between mutually exclusive goals. Parties who compromise, however, might settle for a simple solution and overlook more creative solutions (Pruitt & Carnevale, 1993 ).

The negotiation styles displayed in Figure 2 , on the diagonal from yielding via compromising to forcing, entail distributive behavior. Distributive behavior aims to distribute the value of a deal in a win–lose fashion—one’s losses are the other’s gains. These are the behavior that bargainers engage in during positional bargaining—each side takes a position, argues for it, and might make concessions in order to move toward a compromise (Fisher et al., 2012 ). The negotiation style problem-solving, which is located beyond this distributive diagonal, aims at reaching win–win agreements. Instead of focusing on their positions, parties with a high concern for self and for other may focus on their interests. Interests are the underlying causes or reasons why negotiators take a certain position (Fisher et al., 2012 ). Engaging in integrative problem-solving behavior, negotiators try to find solutions that integrate both parties’ interests and are thus better for both parties than a simple compromise would be (see the article “ Conflict Management ” for a more elaborate description of the dual concern model).

Differentiation before Integration

Negotiations often follow a differentiation-before-integration pattern in which negotiating parties start with distributive, forcing behavior, such as threatening the other party or fiercely arguing for their own interests. Only after realizing that this competitive behavior does not bring them any closer to an agreement, for example because the other party does the same, they tend to switch to more integrative negotiation and become willing to look for mutually satisfactory agreements (Harinck & De Dreu, 2004 ; Olekalns & Smith, 2005 ; Walton & McKersie, 1965 ). In lab studies, such switches from competitive to cooperative negotiation often occur after temporary impasses (Harinck & De Dreu, 2004 )—moments in a negotiation in which parties take a time-out before having reached an agreement. In field studies, such switches have been described as “ripe moments” (Zartman, 1991 ) or “turning points” (Druckman, 2001 ; Druckman & Olekalns, 2011 ).

Outcomes of Negotiations

Outcomes of negotiations are either an impasse when no agreement is reached or an agreement that can be either distributive (win–lose) or integrative (win–win). Outcomes can be measured as objective or economic outcomes—such as money or points—and as subjective outcomes—such as satisfaction with the outcome or process and willingness to interact in the future (Curhan, Elfenbein, & Kilduff, 2009 ). Distributive agreements are those that divide some fixed resources between parties in a win–lose way—one party’s gains are the other party’s losses. An example would be a situation in which a buyer and seller are negotiating only about the price of a bike. Win–lose does not necessarily imply victory of one party over the other—a simple compromise (50–50) where parties meet in the middle of their initial demands is an example of a distributive agreement as well. Distributive negotiation styles are likely to lead to impasses when parties match their forcing behavior, or to distributive agreements when one party yields to the forcing of the other or when both decide to compromise and “meet in the middle.”

Integrative agreements are those that divide an expanded set of resources and thereby increase the benefit for both negotiators. Contrary to distributive bargaining, which is dominated by value-claiming strategies, integrative negotiation offers the possibility to create value, that is, to find solutions that improve the outcomes to both parties (Lewicki et al., 2021 ). A key activity in integrative negotiation is to generate alternative solutions to the problem at hand. One way to generate alternative solutions is by adding resources and negotiating about more than initially planned, thereby making a deal more attractive to both parties. Figuratively, negotiators expand the pie before they divide it. For example, the seller of a bicycle might add a good bicycle lock that he does not need any more, thereby making a better deal selling his bike and lock, while the buyer gets a good lock for his new bike and in total pays less than he would have paid if he had to buy a new lock in a shop.

Another way to generate alternative solutions is by discussing multiple issues rather than single issues, and by determining which issues are more and less important. For example, the seller of the bicycle might be a returning exchange student who cannot take the bike to his home country, but he needs to use it until the final days of his stay. By negotiating the price and delivery date, buyer and seller may integrate the seller’s preference for a late delivery with the buyer’s preference for a lower price. Integrative negotiation styles can lead to integrative agreements; if negotiators trust each other, exchange information, and gain an accurate understanding of their preferences and priorities, they might detect common interests (Rubin et al., 1994 ) and mutually beneficial trade-offs across topics that vary in importance (Ritov & Moran, 2008 ), so-called logrolling (Thompson & Hastie, 1990 ). Parties can also reach integrative agreements through an implicit way of exchanging information, for example by proposing multiple equivalent simultaneous offers (MESOs; Leonardelli, Gu, McRuer, Medvec, & Galinsky, 2019 ) and letting the other side choose which offers they prefer. For example, knowing that a rental bike would cost €50 a week, the seller may propose two equally attractive offers—selling the bike immediately for €300, or selling it in one week for €250. The prospective buyer, provided he has little urgency, might choose the latter option, thereby creating value from the different priorities that the two parties have.

An important ability of negotiators is perspective-taking, the cognitive capacity to consider the world from another individual’s viewpoint (Galinsky & Mussweiler, 2001 ; Trötschel, Hüffmeier, Loschelder, Schwartz, & Gollwitzer, 2011 ). Perspective-taking helps negotiators detect logrolling opportunities and thereby exploit the integrative potential of a negotiation situation (Trötschel et al., 2011 ).

Cognitions (how people think about a situation) influence negotiation behaviors and outcomes. Cognitions have been the focus of the behavioral decision perspective on negotiations that was dominant in the 1980s and 1990s (for an overview, see Bazerman, Curhan, Moore, & Valley, 2000 ). Two of the most prominent biases are fixed-pie perceptions and anchoring.

Fixed-Pie Perception

A fixed-pie perception is the common assumption that the interests of the parties are diametrically opposed such that “my gain is your loss” (Thompson & Hastie, 1990 ). This idea is related to the view that negotiation is a purely distributive contest in dividing a fixed amount of resources in which the winner claims a larger share than the loser. When both parties have a fixed-pie perception, they are unlikely to notice that their priorities may differ and might overlook profitable opportunities for a mutually beneficial exchange of concessions (logrolling; as described in the section “ Outcomes of Negotiations ”).

Anchoring is the tendency to rely on a first number when making a judgment. For example, the interested buyer might offer a higher price if, immediately before negotiating the price of the second-hand bike, he saw an ad for a bike costing €1,500, than if he saw a bike offered for €100. The offer made for the second-hand bike is thus influenced (anchored) by prior information. This bias is related to the first-offer effect. In negotiations, the first offer functions as an anchor point at which the negotiation starts and a negotiation agreement is often in favor of the first party that proposes a concrete number (Galinsky & Mussweiler, 2001 ; Loschelder, Trötschel, Swaab, Friese, & Galinsky, 2016 ).

Emotions (how people feel about a situation) and the expression thereof have a profound influence on negotiation processes and outcomes. The effects of emotions on the negotiation process can be intrapersonal—a person’s mood or emotion influences his or her own behavior. These effects can also be interpersonal—one person who expresses his or her emotions affects another person’s behavior (Van Kleef, Van Dijk, Steinel, Harinck, & Van Beest, 2008 ).

Intrapersonal Effects of Emotions

The intrapersonal effects of emotions are straightforward. Negotiators who are in a bad mood, or who feel angry or disappointed, are more likely to engage in forcing behavior and less likely to accommodate the other party. On the other hand, negotiators who are in a good mood or feel happy are more likely to be lenient negotiation partners who are willing to make a deal (Allred, Mallozzi, Matsui, & Raia, 1997 ; Friedman et al., 2004 ; Kopelman, Rosette, & Thompson, 2006 ; Van Kleef & De Dreu, 2010 ; Van Kleef, De Dreu, & Manstead, 2004 ).

Interpersonal Effects of Emotions

The interpersonal effects of emotions in negotiations are summarized by the Emotions-As-Social-Information Model (Van Kleef, 2009 ), which proposes that a negotiator’s emotions affect the behavior of their counterparts via two distinct processes. Emotions trigger inferential processes and affective reactions in the targets of those emotions. The inferential process means that emotions give information about the aspirations of a party—an angry reaction of a counterpart on a proposal signals that the counterpart has set ambitious limits. As a result, an angry reaction by party A often triggers a yielding response by party B, in order to satisfy party A and reach an agreement (Sinaceur & Tiedens, 2006 ; Van Kleef et al., 2004 ). A happy reaction by party A, on the other hand, might indicate the proposal is near target point of party A, and party B may conclude that no further concessions are required in order to reach an agreement.

Emotions might also trigger an affective reaction in the receiver; an expression of anger of party A is likely to engender an angry reaction by party B in return, whereas a more happy reaction will trigger a happier response. In general, the interpersonal effect of anger is exemplified by the finding that negotiators who express anger will get a yielding response from their counterpart, but only when the other party is willing and able to take the emotions of the angry party into account (Sinaceur & Tiedens, 2006 ; Van Kleef et al., 2004 ). On the other hand, an expression of happiness is met with a more competitive or less yielding response. Expressing anger in negotiations can backfire, however (Van Kleef et al., 2008 ). Anger directed at the person, rather than at a proposal, is likely to lead to retaliation rather than concessions (Steinel, Van Kleef, & Harinck, 2008 ), and the same effect occurs for angry expressions in value-laden conflict (Harinck & Van Kleef, 2012 ); people may overtly concede to a counterpart who expresses anger, but they might subsequently retaliate covertly (Wang, Northcraft, & Van Kleef, 2012 ). Similarly, expressing anger helps powerful negotiators who may receive a conciliatory response, but harms powerless parties, who are more likely to receive an angry, non-conciliatory response (Overbeck, Neale, & Govan, 2010 ; Van Dijk, Van Kleef, Steinel, & Van Beest, 2008 ). Also, fake expressions of anger aimed at trying to get the other party to concede are more likely to lead to intransigence rather than to conciliatory behavior in the receiving party, due to reduced trust (Campagna, Mislin, Kong, & Bottom, 2016 ; Côté, Hideg, & Van Kleef, 2013 ).