- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Problem-Solving Strategies and Obstacles

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Sean is a fact-checker and researcher with experience in sociology, field research, and data analytics.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sean-Blackburn-1000-a8b2229366944421bc4b2f2ba26a1003.jpg)

JGI / Jamie Grill / Getty Images

- Application

- Improvement

From deciding what to eat for dinner to considering whether it's the right time to buy a house, problem-solving is a large part of our daily lives. Learn some of the problem-solving strategies that exist and how to use them in real life, along with ways to overcome obstacles that are making it harder to resolve the issues you face.

What Is Problem-Solving?

In cognitive psychology , the term 'problem-solving' refers to the mental process that people go through to discover, analyze, and solve problems.

A problem exists when there is a goal that we want to achieve but the process by which we will achieve it is not obvious to us. Put another way, there is something that we want to occur in our life, yet we are not immediately certain how to make it happen.

Maybe you want a better relationship with your spouse or another family member but you're not sure how to improve it. Or you want to start a business but are unsure what steps to take. Problem-solving helps you figure out how to achieve these desires.

The problem-solving process involves:

- Discovery of the problem

- Deciding to tackle the issue

- Seeking to understand the problem more fully

- Researching available options or solutions

- Taking action to resolve the issue

Before problem-solving can occur, it is important to first understand the exact nature of the problem itself. If your understanding of the issue is faulty, your attempts to resolve it will also be incorrect or flawed.

Problem-Solving Mental Processes

Several mental processes are at work during problem-solving. Among them are:

- Perceptually recognizing the problem

- Representing the problem in memory

- Considering relevant information that applies to the problem

- Identifying different aspects of the problem

- Labeling and describing the problem

Problem-Solving Strategies

There are many ways to go about solving a problem. Some of these strategies might be used on their own, or you may decide to employ multiple approaches when working to figure out and fix a problem.

An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure that, by following certain "rules" produces a solution. Algorithms are commonly used in mathematics to solve division or multiplication problems. But they can be used in other fields as well.

In psychology, algorithms can be used to help identify individuals with a greater risk of mental health issues. For instance, research suggests that certain algorithms might help us recognize children with an elevated risk of suicide or self-harm.

One benefit of algorithms is that they guarantee an accurate answer. However, they aren't always the best approach to problem-solving, in part because detecting patterns can be incredibly time-consuming.

There are also concerns when machine learning is involved—also known as artificial intelligence (AI)—such as whether they can accurately predict human behaviors.

Heuristics are shortcut strategies that people can use to solve a problem at hand. These "rule of thumb" approaches allow you to simplify complex problems, reducing the total number of possible solutions to a more manageable set.

If you find yourself sitting in a traffic jam, for example, you may quickly consider other routes, taking one to get moving once again. When shopping for a new car, you might think back to a prior experience when negotiating got you a lower price, then employ the same tactics.

While heuristics may be helpful when facing smaller issues, major decisions shouldn't necessarily be made using a shortcut approach. Heuristics also don't guarantee an effective solution, such as when trying to drive around a traffic jam only to find yourself on an equally crowded route.

Trial and Error

A trial-and-error approach to problem-solving involves trying a number of potential solutions to a particular issue, then ruling out those that do not work. If you're not sure whether to buy a shirt in blue or green, for instance, you may try on each before deciding which one to purchase.

This can be a good strategy to use if you have a limited number of solutions available. But if there are many different choices available, narrowing down the possible options using another problem-solving technique can be helpful before attempting trial and error.

In some cases, the solution to a problem can appear as a sudden insight. You are facing an issue in a relationship or your career when, out of nowhere, the solution appears in your mind and you know exactly what to do.

Insight can occur when the problem in front of you is similar to an issue that you've dealt with in the past. Although, you may not recognize what is occurring since the underlying mental processes that lead to insight often happen outside of conscious awareness .

Research indicates that insight is most likely to occur during times when you are alone—such as when going on a walk by yourself, when you're in the shower, or when lying in bed after waking up.

How to Apply Problem-Solving Strategies in Real Life

If you're facing a problem, you can implement one or more of these strategies to find a potential solution. Here's how to use them in real life:

- Create a flow chart . If you have time, you can take advantage of the algorithm approach to problem-solving by sitting down and making a flow chart of each potential solution, its consequences, and what happens next.

- Recall your past experiences . When a problem needs to be solved fairly quickly, heuristics may be a better approach. Think back to when you faced a similar issue, then use your knowledge and experience to choose the best option possible.

- Start trying potential solutions . If your options are limited, start trying them one by one to see which solution is best for achieving your desired goal. If a particular solution doesn't work, move on to the next.

- Take some time alone . Since insight is often achieved when you're alone, carve out time to be by yourself for a while. The answer to your problem may come to you, seemingly out of the blue, if you spend some time away from others.

Obstacles to Problem-Solving

Problem-solving is not a flawless process as there are a number of obstacles that can interfere with our ability to solve a problem quickly and efficiently. These obstacles include:

- Assumptions: When dealing with a problem, people can make assumptions about the constraints and obstacles that prevent certain solutions. Thus, they may not even try some potential options.

- Functional fixedness : This term refers to the tendency to view problems only in their customary manner. Functional fixedness prevents people from fully seeing all of the different options that might be available to find a solution.

- Irrelevant or misleading information: When trying to solve a problem, it's important to distinguish between information that is relevant to the issue and irrelevant data that can lead to faulty solutions. The more complex the problem, the easier it is to focus on misleading or irrelevant information.

- Mental set: A mental set is a tendency to only use solutions that have worked in the past rather than looking for alternative ideas. A mental set can work as a heuristic, making it a useful problem-solving tool. However, mental sets can also lead to inflexibility, making it more difficult to find effective solutions.

How to Improve Your Problem-Solving Skills

In the end, if your goal is to become a better problem-solver, it's helpful to remember that this is a process. Thus, if you want to improve your problem-solving skills, following these steps can help lead you to your solution:

- Recognize that a problem exists . If you are facing a problem, there are generally signs. For instance, if you have a mental illness , you may experience excessive fear or sadness, mood changes, and changes in sleeping or eating habits. Recognizing these signs can help you realize that an issue exists.

- Decide to solve the problem . Make a conscious decision to solve the issue at hand. Commit to yourself that you will go through the steps necessary to find a solution.

- Seek to fully understand the issue . Analyze the problem you face, looking at it from all sides. If your problem is relationship-related, for instance, ask yourself how the other person may be interpreting the issue. You might also consider how your actions might be contributing to the situation.

- Research potential options . Using the problem-solving strategies mentioned, research potential solutions. Make a list of options, then consider each one individually. What are some pros and cons of taking the available routes? What would you need to do to make them happen?

- Take action . Select the best solution possible and take action. Action is one of the steps required for change . So, go through the motions needed to resolve the issue.

- Try another option, if needed . If the solution you chose didn't work, don't give up. Either go through the problem-solving process again or simply try another option.

You can find a way to solve your problems as long as you keep working toward this goal—even if the best solution is simply to let go because no other good solution exists.

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

Dunbar K. Problem solving . A Companion to Cognitive Science . 2017. doi:10.1002/9781405164535.ch20

Stewart SL, Celebre A, Hirdes JP, Poss JW. Risk of suicide and self-harm in kids: The development of an algorithm to identify high-risk individuals within the children's mental health system . Child Psychiat Human Develop . 2020;51:913-924. doi:10.1007/s10578-020-00968-9

Rosenbusch H, Soldner F, Evans AM, Zeelenberg M. Supervised machine learning methods in psychology: A practical introduction with annotated R code . Soc Personal Psychol Compass . 2021;15(2):e12579. doi:10.1111/spc3.12579

Mishra S. Decision-making under risk: Integrating perspectives from biology, economics, and psychology . Personal Soc Psychol Rev . 2014;18(3):280-307. doi:10.1177/1088868314530517

Csikszentmihalyi M, Sawyer K. Creative insight: The social dimension of a solitary moment . In: The Systems Model of Creativity . 2015:73-98. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9085-7_7

Chrysikou EG, Motyka K, Nigro C, Yang SI, Thompson-Schill SL. Functional fixedness in creative thinking tasks depends on stimulus modality . Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts . 2016;10(4):425‐435. doi:10.1037/aca0000050

Huang F, Tang S, Hu Z. Unconditional perseveration of the short-term mental set in chunk decomposition . Front Psychol . 2018;9:2568. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02568

National Alliance on Mental Illness. Warning signs and symptoms .

Mayer RE. Thinking, problem solving, cognition, 2nd ed .

Schooler JW, Ohlsson S, Brooks K. Thoughts beyond words: When language overshadows insight. J Experiment Psychol: General . 1993;122:166-183. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.2.166

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Barriers to Effective Problem Solving

Learning how to effectively solve problems is difficult and takes time and continual adaptation. There are several common barriers to successful CPS, including:

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to only search for or interpret information that confirms a person’s existing ideas. People misinterpret or disregard data that doesn’t align with their beliefs.

- Mental Set: People’s inclination to solve problems using the same tactics they have used to solve problems in the past. While this can sometimes be a useful strategy (see Analogical Thinking in a later section), it often limits inventiveness and creativity.

- Functional Fixedness: This is another form of narrow thinking, where people become “stuck” thinking in a certain way and are unable to be flexible or change perspective.

- Unnecessary Constraints: When people are overwhelmed with a problem, they can invent and impose additional limits on solution avenues. To avoid doing this, maintain a structured, level-headed approach to evaluating causes, effects, and potential solutions.

- Groupthink: Be wary of the tendency for group members to agree with each other — this might be out of conflict avoidance, path of least resistance, or fear of speaking up. While this agreeableness might make meetings run smoothly, it can actually stunt creativity and idea generation, therefore limiting the success of your chosen solution.

- Irrelevant Information: The tendency to pile on multiple problems and factors that may not even be related to the challenge at hand. This can cloud the team’s ability to find direct, targeted solutions.

- Paradigm Blindness : This is found in people who are unwilling to adapt or change their worldview, outlook on a particular problem, or typical way of processing information. This can erode the effectiveness of problem solving techniques because they are not aware of the narrowness of their thinking, and therefore cannot think or act outside of their comfort zone.

According to Jaffa, the primary barrier of effective problem solving is rigidity. “The most common things people say are, ‘We’ve never done it before,’ or ‘We’ve always done it this way.’” While these feelings are natural, Jaffa explains that this rigid thinking actually precludes teams from identifying creative, inventive solutions that result in the greatest benefit. “The biggest barrier to creative problem solving is a lack of awareness – and commitment to – training employees in state-of-the-art creative problem-solving techniques,” Mattimore explains. “We teach our clients how to use ideation techniques (as many as two-dozen different creative thinking techniques) to help them generate more and better ideas. Ideation techniques use specific and customized stimuli, or ‘thought triggers’ to inspire new thinking and new ideas.” MacLeod adds that ineffective or rushed leadership is another common culprit. “We're always in a rush to fix quickly,” she says. “Sometimes leaders just solve problems themselves, making unilateral decisions to save time. But the investment is well worth it — leaders will have less on their plates if they can teach and eventually trust the team to resolve. Teams feel empowered and engagement and investment increases.”

Image Courtesy of Pexels.

7.3 Problem-Solving

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe problem solving strategies

- Define algorithm and heuristic

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving

People face problems every day—usually, multiple problems throughout the day. Sometimes these problems are straightforward: To double a recipe for pizza dough, for example, all that is required is that each ingredient in the recipe be doubled. Sometimes, however, the problems we encounter are more complex. For example, say you have a work deadline, and you must mail a printed copy of a report to your supervisor by the end of the business day. The report is time-sensitive and must be sent overnight. You finished the report last night, but your printer will not work today. What should you do? First, you need to identify the problem and then apply a strategy for solving the problem.

The study of human and animal problem solving processes has provided much insight toward the understanding of our conscious experience and led to advancements in computer science and artificial intelligence. Essentially much of cognitive science today represents studies of how we consciously and unconsciously make decisions and solve problems. For instance, when encountered with a large amount of information, how do we go about making decisions about the most efficient way of sorting and analyzing all the information in order to find what you are looking for as in visual search paradigms in cognitive psychology. Or in a situation where a piece of machinery is not working properly, how do we go about organizing how to address the issue and understand what the cause of the problem might be. How do we sort the procedures that will be needed and focus attention on what is important in order to solve problems efficiently. Within this section we will discuss some of these issues and examine processes related to human, animal and computer problem solving.

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGIES

When people are presented with a problem—whether it is a complex mathematical problem or a broken printer, how do you solve it? Before finding a solution to the problem, the problem must first be clearly identified. After that, one of many problem solving strategies can be applied, hopefully resulting in a solution.

Problems themselves can be classified into two different categories known as ill-defined and well-defined problems (Schacter, 2009). Ill-defined problems represent issues that do not have clear goals, solution paths, or expected solutions whereas well-defined problems have specific goals, clearly defined solutions, and clear expected solutions. Problem solving often incorporates pragmatics (logical reasoning) and semantics (interpretation of meanings behind the problem), and also in many cases require abstract thinking and creativity in order to find novel solutions. Within psychology, problem solving refers to a motivational drive for reading a definite “goal” from a present situation or condition that is either not moving toward that goal, is distant from it, or requires more complex logical analysis for finding a missing description of conditions or steps toward that goal. Processes relating to problem solving include problem finding also known as problem analysis, problem shaping where the organization of the problem occurs, generating alternative strategies, implementation of attempted solutions, and verification of the selected solution. Various methods of studying problem solving exist within the field of psychology including introspection, behavior analysis and behaviorism, simulation, computer modeling, and experimentation.

A problem-solving strategy is a plan of action used to find a solution. Different strategies have different action plans associated with them (table below). For example, a well-known strategy is trial and error. The old adage, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” describes trial and error. In terms of your broken printer, you could try checking the ink levels, and if that doesn’t work, you could check to make sure the paper tray isn’t jammed. Or maybe the printer isn’t actually connected to your laptop. When using trial and error, you would continue to try different solutions until you solved your problem. Although trial and error is not typically one of the most time-efficient strategies, it is a commonly used one.

Another type of strategy is an algorithm. An algorithm is a problem-solving formula that provides you with step-by-step instructions used to achieve a desired outcome (Kahneman, 2011). You can think of an algorithm as a recipe with highly detailed instructions that produce the same result every time they are performed. Algorithms are used frequently in our everyday lives, especially in computer science. When you run a search on the Internet, search engines like Google use algorithms to decide which entries will appear first in your list of results. Facebook also uses algorithms to decide which posts to display on your newsfeed. Can you identify other situations in which algorithms are used?

A heuristic is another type of problem solving strategy. While an algorithm must be followed exactly to produce a correct result, a heuristic is a general problem-solving framework (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). You can think of these as mental shortcuts that are used to solve problems. A “rule of thumb” is an example of a heuristic. Such a rule saves the person time and energy when making a decision, but despite its time-saving characteristics, it is not always the best method for making a rational decision. Different types of heuristics are used in different types of situations, but the impulse to use a heuristic occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind in the same moment

Working backwards is a useful heuristic in which you begin solving the problem by focusing on the end result. Consider this example: You live in Washington, D.C. and have been invited to a wedding at 4 PM on Saturday in Philadelphia. Knowing that Interstate 95 tends to back up any day of the week, you need to plan your route and time your departure accordingly. If you want to be at the wedding service by 3:30 PM, and it takes 2.5 hours to get to Philadelphia without traffic, what time should you leave your house? You use the working backwards heuristic to plan the events of your day on a regular basis, probably without even thinking about it.

Another useful heuristic is the practice of accomplishing a large goal or task by breaking it into a series of smaller steps. Students often use this common method to complete a large research project or long essay for school. For example, students typically brainstorm, develop a thesis or main topic, research the chosen topic, organize their information into an outline, write a rough draft, revise and edit the rough draft, develop a final draft, organize the references list, and proofread their work before turning in the project. The large task becomes less overwhelming when it is broken down into a series of small steps.

Further problem solving strategies have been identified (listed below) that incorporate flexible and creative thinking in order to reach solutions efficiently.

Additional Problem Solving Strategies :

- Abstraction – refers to solving the problem within a model of the situation before applying it to reality.

- Analogy – is using a solution that solves a similar problem.

- Brainstorming – refers to collecting an analyzing a large amount of solutions, especially within a group of people, to combine the solutions and developing them until an optimal solution is reached.

- Divide and conquer – breaking down large complex problems into smaller more manageable problems.

- Hypothesis testing – method used in experimentation where an assumption about what would happen in response to manipulating an independent variable is made, and analysis of the affects of the manipulation are made and compared to the original hypothesis.

- Lateral thinking – approaching problems indirectly and creatively by viewing the problem in a new and unusual light.

- Means-ends analysis – choosing and analyzing an action at a series of smaller steps to move closer to the goal.

- Method of focal objects – putting seemingly non-matching characteristics of different procedures together to make something new that will get you closer to the goal.

- Morphological analysis – analyzing the outputs of and interactions of many pieces that together make up a whole system.

- Proof – trying to prove that a problem cannot be solved. Where the proof fails becomes the starting point or solving the problem.

- Reduction – adapting the problem to be as similar problems where a solution exists.

- Research – using existing knowledge or solutions to similar problems to solve the problem.

- Root cause analysis – trying to identify the cause of the problem.

The strategies listed above outline a short summary of methods we use in working toward solutions and also demonstrate how the mind works when being faced with barriers preventing goals to be reached.

One example of means-end analysis can be found by using the Tower of Hanoi paradigm . This paradigm can be modeled as a word problems as demonstrated by the Missionary-Cannibal Problem :

Missionary-Cannibal Problem

Three missionaries and three cannibals are on one side of a river and need to cross to the other side. The only means of crossing is a boat, and the boat can only hold two people at a time. Your goal is to devise a set of moves that will transport all six of the people across the river, being in mind the following constraint: The number of cannibals can never exceed the number of missionaries in any location. Remember that someone will have to also row that boat back across each time.

Hint : At one point in your solution, you will have to send more people back to the original side than you just sent to the destination.

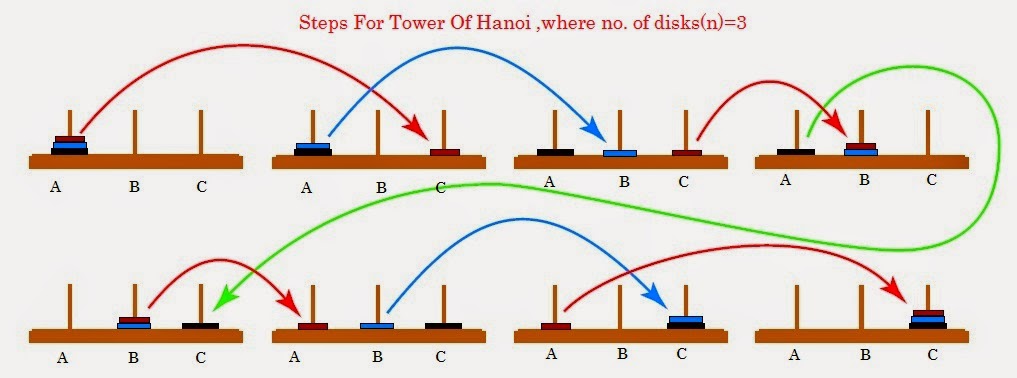

The actual Tower of Hanoi problem consists of three rods sitting vertically on a base with a number of disks of different sizes that can slide onto any rod. The puzzle starts with the disks in a neat stack in ascending order of size on one rod, the smallest at the top making a conical shape. The objective of the puzzle is to move the entire stack to another rod obeying the following rules:

- 1. Only one disk can be moved at a time.

- 2. Each move consists of taking the upper disk from one of the stacks and placing it on top of another stack or on an empty rod.

- 3. No disc may be placed on top of a smaller disk.

Figure 7.02. Steps for solving the Tower of Hanoi in the minimum number of moves when there are 3 disks.

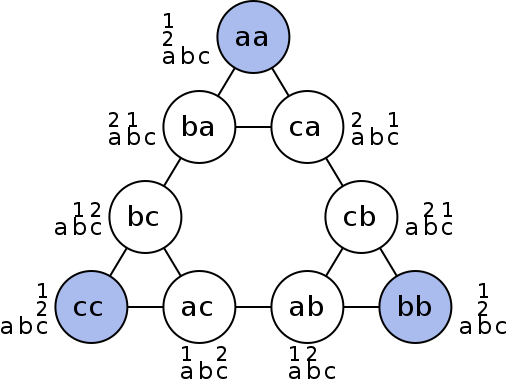

Figure 7.03. Graphical representation of nodes (circles) and moves (lines) of Tower of Hanoi.

The Tower of Hanoi is a frequently used psychological technique to study problem solving and procedure analysis. A variation of the Tower of Hanoi known as the Tower of London has been developed which has been an important tool in the neuropsychological diagnosis of executive function disorders and their treatment.

GESTALT PSYCHOLOGY AND PROBLEM SOLVING

As you may recall from the sensation and perception chapter, Gestalt psychology describes whole patterns, forms and configurations of perception and cognition such as closure, good continuation, and figure-ground. In addition to patterns of perception, Wolfgang Kohler, a German Gestalt psychologist traveled to the Spanish island of Tenerife in order to study animals behavior and problem solving in the anthropoid ape.

As an interesting side note to Kohler’s studies of chimp problem solving, Dr. Ronald Ley, professor of psychology at State University of New York provides evidence in his book A Whisper of Espionage (1990) suggesting that while collecting data for what would later be his book The Mentality of Apes (1925) on Tenerife in the Canary Islands between 1914 and 1920, Kohler was additionally an active spy for the German government alerting Germany to ships that were sailing around the Canary Islands. Ley suggests his investigations in England, Germany and elsewhere in Europe confirm that Kohler had served in the German military by building, maintaining and operating a concealed radio that contributed to Germany’s war effort acting as a strategic outpost in the Canary Islands that could monitor naval military activity approaching the north African coast.

While trapped on the island over the course of World War 1, Kohler applied Gestalt principles to animal perception in order to understand how they solve problems. He recognized that the apes on the islands also perceive relations between stimuli and the environment in Gestalt patterns and understand these patterns as wholes as opposed to pieces that make up a whole. Kohler based his theories of animal intelligence on the ability to understand relations between stimuli, and spent much of his time while trapped on the island investigation what he described as insight , the sudden perception of useful or proper relations. In order to study insight in animals, Kohler would present problems to chimpanzee’s by hanging some banana’s or some kind of food so it was suspended higher than the apes could reach. Within the room, Kohler would arrange a variety of boxes, sticks or other tools the chimpanzees could use by combining in patterns or organizing in a way that would allow them to obtain the food (Kohler & Winter, 1925).

While viewing the chimpanzee’s, Kohler noticed one chimp that was more efficient at solving problems than some of the others. The chimp, named Sultan, was able to use long poles to reach through bars and organize objects in specific patterns to obtain food or other desirables that were originally out of reach. In order to study insight within these chimps, Kohler would remove objects from the room to systematically make the food more difficult to obtain. As the story goes, after removing many of the objects Sultan was used to using to obtain the food, he sat down ad sulked for a while, and then suddenly got up going over to two poles lying on the ground. Without hesitation Sultan put one pole inside the end of the other creating a longer pole that he could use to obtain the food demonstrating an ideal example of what Kohler described as insight. In another situation, Sultan discovered how to stand on a box to reach a banana that was suspended from the rafters illustrating Sultan’s perception of relations and the importance of insight in problem solving.

Grande (another chimp in the group studied by Kohler) builds a three-box structure to reach the bananas, while Sultan watches from the ground. Insight , sometimes referred to as an “Ah-ha” experience, was the term Kohler used for the sudden perception of useful relations among objects during problem solving (Kohler, 1927; Radvansky & Ashcraft, 2013).

Solving puzzles.

Problem-solving abilities can improve with practice. Many people challenge themselves every day with puzzles and other mental exercises to sharpen their problem-solving skills. Sudoku puzzles appear daily in most newspapers. Typically, a sudoku puzzle is a 9×9 grid. The simple sudoku below (see figure) is a 4×4 grid. To solve the puzzle, fill in the empty boxes with a single digit: 1, 2, 3, or 4. Here are the rules: The numbers must total 10 in each bolded box, each row, and each column; however, each digit can only appear once in a bolded box, row, and column. Time yourself as you solve this puzzle and compare your time with a classmate.

How long did it take you to solve this sudoku puzzle? (You can see the answer at the end of this section.)

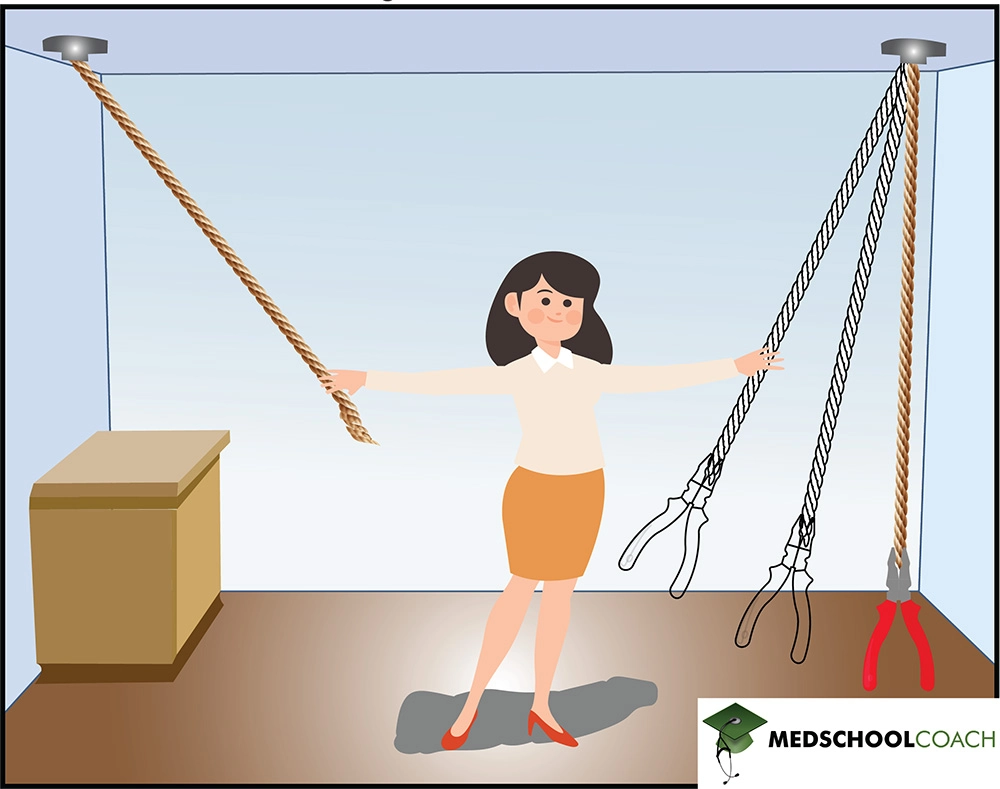

Here is another popular type of puzzle (figure below) that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper:

Did you figure it out? (The answer is at the end of this section.) Once you understand how to crack this puzzle, you won’t forget.

Take a look at the “Puzzling Scales” logic puzzle below (figure below). Sam Loyd, a well-known puzzle master, created and refined countless puzzles throughout his lifetime (Cyclopedia of Puzzles, n.d.).

What steps did you take to solve this puzzle? You can read the solution at the end of this section.

Pitfalls to problem solving.

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but she just needs to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now.

Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and nonindustrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Often, this knowledge and reasoning is sound and solid. Sometimes, however, we are swayed by biases or by others manipulating a situation. For example, let’s say you and three friends wanted to rent a house and had a combined target budget of $1,600. The realtor shows you only very run-down houses for $1,600 and then shows you a very nice house for $2,000. Might you ask each person to pay more in rent to get the $2,000 home? Why would the realtor show you the run-down houses and the nice house? The realtor may be challenging your anchoring bias. An anchoring bias occurs when you focus on one piece of information when making a decision or solving a problem. In this case, you’re so focused on the amount of money you are willing to spend that you may not recognize what kinds of houses are available at that price point.

The confirmation bias is the tendency to focus on information that confirms your existing beliefs. For example, if you think that your professor is not very nice, you notice all of the instances of rude behavior exhibited by the professor while ignoring the countless pleasant interactions he is involved in on a daily basis. Hindsight bias leads you to believe that the event you just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t. In other words, you knew all along that things would turn out the way they did. Representative bias describes a faulty way of thinking, in which you unintentionally stereotype someone or something; for example, you may assume that your professors spend their free time reading books and engaging in intellectual conversation, because the idea of them spending their time playing volleyball or visiting an amusement park does not fit in with your stereotypes of professors.

Finally, the availability heuristic is a heuristic in which you make a decision based on an example, information, or recent experience that is that readily available to you, even though it may not be the best example to inform your decision . Biases tend to “preserve that which is already established—to maintain our preexisting knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and hypotheses” (Aronson, 1995; Kahneman, 2011). These biases are summarized in the table below.

Were you able to determine how many marbles are needed to balance the scales in the figure below? You need nine. Were you able to solve the problems in the figures above? Here are the answers.

Many different strategies exist for solving problems. Typical strategies include trial and error, applying algorithms, and using heuristics. To solve a large, complicated problem, it often helps to break the problem into smaller steps that can be accomplished individually, leading to an overall solution. Roadblocks to problem solving include a mental set, functional fixedness, and various biases that can cloud decision making skills.

References:

Openstax Psychology text by Kathryn Dumper, William Jenkins, Arlene Lacombe, Marilyn Lovett and Marion Perlmutter licensed under CC BY v4.0. https://openstax.org/details/books/psychology

Review Questions:

1. A specific formula for solving a problem is called ________.

a. an algorithm

b. a heuristic

c. a mental set

d. trial and error

2. Solving the Tower of Hanoi problem tends to utilize a ________ strategy of problem solving.

a. divide and conquer

b. means-end analysis

d. experiment

3. A mental shortcut in the form of a general problem-solving framework is called ________.

4. Which type of bias involves becoming fixated on a single trait of a problem?

a. anchoring bias

b. confirmation bias

c. representative bias

d. availability bias

5. Which type of bias involves relying on a false stereotype to make a decision?

6. Wolfgang Kohler analyzed behavior of chimpanzees by applying Gestalt principles to describe ________.

a. social adjustment

b. student load payment options

c. emotional learning

d. insight learning

7. ________ is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for.

a. functional fixedness

c. working memory

Critical Thinking Questions:

1. What is functional fixedness and how can overcoming it help you solve problems?

2. How does an algorithm save you time and energy when solving a problem?

Personal Application Question:

1. Which type of bias do you recognize in your own decision making processes? How has this bias affected how you’ve made decisions in the past and how can you use your awareness of it to improve your decisions making skills in the future?

anchoring bias

availability heuristic

confirmation bias

functional fixedness

hindsight bias

problem-solving strategy

representative bias

trial and error

working backwards

Answers to Exercises

algorithm: problem-solving strategy characterized by a specific set of instructions

anchoring bias: faulty heuristic in which you fixate on a single aspect of a problem to find a solution

availability heuristic: faulty heuristic in which you make a decision based on information readily available to you

confirmation bias: faulty heuristic in which you focus on information that confirms your beliefs

functional fixedness: inability to see an object as useful for any other use other than the one for which it was intended

heuristic: mental shortcut that saves time when solving a problem

hindsight bias: belief that the event just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t

mental set: continually using an old solution to a problem without results

problem-solving strategy: method for solving problems

representative bias: faulty heuristic in which you stereotype someone or something without a valid basis for your judgment

trial and error: problem-solving strategy in which multiple solutions are attempted until the correct one is found

working backwards: heuristic in which you begin to solve a problem by focusing on the end result

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Identifying Barriers to Problem-Solving in Psychology

Problem-solving is a key aspect of psychology, essential for understanding and overcoming challenges in our daily lives. There are common barriers that can hinder our ability to effectively solve problems. From mental blocks to confirmation bias, these obstacles can impede our progress.

In this article, we will explore the various barriers to problem-solving in psychology, as well as strategies to overcome them. By addressing these challenges head-on, we can unlock the benefits of improved problem-solving skills and mental agility.

- Identifying and overcoming barriers to problem-solving in psychology can lead to more effective and efficient solutions.

- Some common barriers include mental blocks, confirmation bias, and functional fixedness, which can all limit critical thinking and creativity.

- Mindfulness techniques, seeking different perspectives, and collaborating with others can help overcome these barriers and lead to more successful problem-solving.

- 1 What Is Problem-Solving in Psychology?

- 2 Why Is Problem-Solving Important in Psychology?

- 3.1 Mental Blocks

- 3.2 Confirmation Bias

- 3.3 Functional Fixedness

- 3.4 Lack of Creativity

- 3.5 Emotional Barriers

- 3.6 Cultural Influences

- 4.1 Divergent Thinking

- 4.2 Mindfulness Techniques

- 4.3 Seeking Different Perspectives

- 4.4 Challenging Assumptions

- 4.5 Collaborating with Others

- 5 What Are the Benefits of Overcoming These Barriers?

- 6 Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Problem-Solving in Psychology?

Problem-solving in psychology refers to the cognitive processes through which individuals identify and overcome obstacles or challenges to reach a desired goal, drawing on various mental processes and strategies.

In the realm of cognitive psychology, problem-solving is a key area of study that delves into how people use algorithms and heuristics to tackle complex issues. Algorithms are systematic step-by-step procedures that guarantee a solution, whereas heuristics are mental shortcuts or rules of thumb that provide efficient solutions, albeit without certainty. Understanding these mental processes is crucial in exploring how individuals approach different types of problems and make decisions based on their problem-solving strategies.

Why Is Problem-Solving Important in Psychology?

Problem-solving holds significant importance in psychology as it facilitates the discovery of new insights, enhances understanding of complex issues, and fosters effective actions based on informed decisions.

Assumptions play a crucial role in problem-solving processes, influencing how individuals perceive and approach challenges. By challenging these assumptions, individuals can break through mental barriers and explore creative solutions.

Functional fixedness, a cognitive bias where individuals restrict the use of objects to their traditional functions, can hinder problem-solving. Overcoming functional fixedness involves reevaluating the purpose of objects, leading to innovative problem-solving strategies.

Through problem-solving, psychologists uncover underlying patterns in behavior, delve into subconscious motivations, and offer practical interventions to improve mental well-being.

What Are the Common Barriers to Problem-Solving in Psychology?

In psychology, common barriers to problem-solving include mental blocks , confirmation bias , functional fixedness, lack of creativity, emotional barriers, and cultural influences that hinder the application of knowledge and resources to overcome challenges.

Mental blocks refer to the difficulty in generating new ideas or solutions due to preconceived notions or past experiences. Confirmation bias, on the other hand, is the tendency to search for, interpret, or prioritize information that confirms existing beliefs or hypotheses, while disregarding opposing evidence.

Functional fixedness limits problem-solving by constraining individuals to view objects or concepts in their traditional uses, inhibiting creative approaches. Lack of creativity impedes the ability to think outside the box and consider unconventional solutions.

Emotional barriers such as fear, stress, or anxiety can halt progress by clouding judgment and hindering clear decision-making. Cultural influences may introduce unique perspectives or expectations that clash with effective problem-solving strategies, complicating the resolution process.

Mental Blocks

Mental blocks in problem-solving occur when individuals struggle to consider all relevant information, fall into a fixed mental set, or become fixated on irrelevant details, hindering progress and creative solutions.

For instance, irrelevant information can lead to mental blocks by distracting individuals from focusing on the key elements required to solve a problem effectively. This could involve getting caught up in minor details that have no real impact on the overall solution. A fixed mental set, formed by previous experiences or patterns, can limit one’s ability to approach a problem from new perspectives, restricting innovative thinking.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias, a common barrier in problem-solving, leads individuals to seek information that confirms their existing knowledge or assumptions, potentially overlooking contradictory data and hindering objective analysis.

This cognitive bias affects decision-making and problem-solving processes by creating a tendency to favor information that aligns with one’s beliefs, rather than considering all perspectives.

- One effective method to mitigate confirmation bias is by actively challenging assumptions through critical thinking.

- By questioning the validity of existing beliefs and seeking out diverse viewpoints, individuals can counteract the tendency to only consider information that confirms their preconceptions.

- Another strategy is to promote a culture of open-mindedness and encourage constructive debate within teams to foster a more comprehensive evaluation of data.

Functional Fixedness

Functional fixedness restricts problem-solving by limiting individuals to conventional uses of objects, impeding the discovery of innovative solutions and hindering the application of insightful approaches to challenges.

For instance, when faced with a task that requires a candle to be mounted on a wall to provide lighting, someone bound by functional fixedness may struggle to see the potential solution of using the candle wax as an adhesive instead of solely perceiving the candle’s purpose as a light source.

This mental rigidity often leads individuals to overlook unconventional or creative methods, which can stifle their ability to find effective problem-solving strategies.

To combat this cognitive limitation, fostering divergent thinking, encouraging experimentation, and promoting flexibility in approaching tasks can help individuals break free from functional fixedness and unlock their creativity.

Lack of Creativity

A lack of creativity poses a significant barrier to problem-solving, limiting the potential for improvement and hindering flexible thinking required to generate novel solutions and address complex challenges.

When individuals are unable to think outside the box and explore unconventional approaches, they may find themselves stuck in repetitive patterns without breakthroughs.

Flexibility is key to overcoming this hurdle, allowing individuals to adapt their perspectives, pivot when necessary, and consider multiple viewpoints to arrive at innovative solutions.

Encouraging a culture that embraces experimentation, values diverse ideas, and fosters an environment of continuous learning can fuel creativity and push problem-solving capabilities to new heights.

Emotional Barriers

Emotional barriers, such as fear of failure, can impede problem-solving by creating anxiety, reducing risk-taking behavior, and hindering effective collaboration with others, limiting the exploration of innovative solutions.

When individuals are held back by the fear of failure, it often stems from a deep-seated worry about making mistakes or being judged negatively. This fear can lead to hesitation in decision-making processes and reluctance to explore unconventional approaches, ultimately hindering the ability to discover creative solutions. To overcome this obstacle, it is essential to cultivate a positive emotional environment that fosters trust, resilience, and open communication among team members. Encouraging a mindset that embraces failure as a stepping stone to success can enable individuals to take risks, learn from setbacks, and collaborate effectively to overcome challenges.

Cultural Influences

Cultural influences can act as barriers to problem-solving by imposing rigid norms, limiting flexibility in thinking, and hindering effective communication and collaboration among diverse individuals with varying perspectives.

When individuals from different cultural backgrounds come together to solve problems, the ingrained values and beliefs they hold can shape their approaches and methods.

For example, in some cultures, decisiveness and quick decision-making are highly valued, while in others, a consensus-building process is preferred.

Understanding and recognizing these differences is crucial for navigating through the cultural barriers that might arise during collaborative problem-solving.

How Can These Barriers Be Overcome?

These barriers to problem-solving in psychology can be overcome through various strategies such as divergent thinking, mindfulness techniques, seeking different perspectives, challenging assumptions, and collaborating with others to leverage diverse insights and foster critical thinking.

Engaging in divergent thinking , which involves generating multiple solutions or viewpoints for a single issue, can help break away from conventional problem-solving methods. By encouraging a free flow of ideas without immediate judgment, individuals can explore innovative paths that may lead to breakthrough solutions. Actively seeking diverse perspectives from individuals with varied backgrounds, experiences, and expertise can offer fresh insights that challenge existing assumptions and broaden the problem-solving scope. This diversity of viewpoints can spark creativity and unconventional approaches that enhance problem-solving outcomes.

Divergent Thinking

Divergent thinking enhances problem-solving by encouraging creative exploration of multiple solutions, breaking habitual thought patterns, and fostering flexibility in generating innovative ideas to address challenges.

When individuals engage in divergent thinking, they open up their minds to various possibilities and perspectives. Instead of being constrained by conventional norms, a person might ideate freely without limitations. This leads to out-of-the-box solutions that can revolutionize how problems are approached. Divergent thinking sparks creativity by allowing unconventional ideas to surface and flourish.

For example, imagine a team tasked with redesigning a city park. Instead of sticking to traditional layouts, they might brainstorm wild concepts like turning the park into a futuristic playground, a pop-up art gallery space, or a wildlife sanctuary. Such diverse ideas stem from divergent thinking and push boundaries beyond the ordinary.

Mindfulness Techniques

Mindfulness techniques can aid problem-solving by promoting present-moment awareness, reducing cognitive biases, and fostering a habit of continuous learning that enhances adaptability and open-mindedness in addressing challenges.

Engaging in regular mindfulness practices encourages individuals to stay grounded in the current moment, allowing them to detach from preconceived notions and biases that could cloud judgment. By cultivating a non-judgmental attitude towards thoughts and emotions, people develop the capacity to observe situations from a neutral perspective, facilitating clearer decision-making processes. Mindfulness techniques facilitate the development of a growth mindset, where one acknowledges mistakes as opportunities for learning and improvement rather than failures.

Seeking Different Perspectives

Seeking different perspectives in problem-solving involves tapping into diverse resources, engaging in effective communication, and considering alternative viewpoints to broaden understanding and identify innovative solutions to complex issues.

Collaboration among individuals with various backgrounds and experiences can offer fresh insights and approaches to tackling challenges. By fostering an environment where all voices are valued and heard, teams can leverage the collective wisdom and creativity present in diverse perspectives. For example, in the tech industry, companies like Google encourage cross-functional teams to work together, harnessing diverse skill sets to develop groundbreaking technologies.

To incorporate diverse viewpoints, one can implement brainstorming sessions that involve individuals from different departments or disciplines to encourage out-of-the-box thinking. Another effective method is to conduct surveys or focus groups to gather input from a wide range of stakeholders and ensure inclusivity in decision-making processes.

Challenging Assumptions

Challenging assumptions is a key strategy in problem-solving, as it prompts individuals to critically evaluate preconceived notions, gain new insights, and expand their knowledge base to approach challenges from fresh perspectives.

By questioning established beliefs or ways of thinking, individuals open the door to innovative solutions and original perspectives. Stepping outside the boundaries of conventional wisdom enables problem solvers to see beyond limitations and explore uncharted territories. This process not only fosters creativity but also encourages a culture of continuous improvement where learning thrives. Daring to challenge assumptions can unveil hidden opportunities and untapped potential in problem-solving scenarios, leading to breakthroughs and advancements that were previously overlooked.

- One effective technique to challenge assumptions is through brainstorming sessions that encourage participants to voice unconventional ideas without judgment.

- Additionally, adopting a beginner’s mindset can help in questioning assumptions, as newcomers often bring a fresh perspective unburdened by past biases.

Collaborating with Others

Collaborating with others in problem-solving fosters flexibility, encourages open communication, and leverages collective intelligence to navigate complex challenges, drawing on diverse perspectives and expertise to generate innovative solutions.

Effective collaboration enables individuals to combine strengths and talents, pooling resources to tackle problems that may seem insurmountable when approached individually. By working together, team members can break down barriers and silos that often hinder progress, leading to more efficient problem-solving processes and better outcomes.

Collaboration also promotes a sense of shared purpose and increases overall engagement, as team members feel valued and enableed to contribute their unique perspectives. To foster successful collaboration, it is crucial to establish clear goals, roles, and communication channels, ensuring that everyone is aligned towards a common objective.

What Are the Benefits of Overcoming These Barriers?

Overcoming the barriers to problem-solving in psychology leads to significant benefits such as improved critical thinking skills, enhanced knowledge acquisition, and the ability to address complex issues with greater creativity and adaptability.

By mastering the art of problem-solving, individuals in the field of psychology can also cultivate resilience and perseverance, two essential traits that contribute to personal growth and success.

When confronting and overcoming cognitive obstacles, individuals develop a deeper understanding of their own cognitive processes and behavioral patterns, enabling them to make informed decisions and overcome challenges more effectively.

Continuous learning and adaptability play a pivotal role in problem-solving, allowing psychologists to stay updated with the latest research, techniques, and methodologies that enhance their problem-solving capabilities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Similar posts.

Understanding Baseline in Psychology

The article was last updated by Lena Nguyen on February 4, 2024. Baseline in psychology is a crucial concept that serves as a reference point…

Understanding Negative Correlation in Psychology: Meaning and Examples

The article was last updated by Dr. Naomi Kessler on February 9, 2024. Negative correlation in psychology is a crucial concept that explores the relationship…

Utilizing Naturalistic Observation in Psychology: An In-Depth Examination

The article was last updated by Julian Torres on February 8, 2024. Have you ever wondered how psychologists study human behavior in real-life settings? Naturalistic…

Mastering the Art of Reading Journal Articles in Social Psychology

The article was last updated by Vanessa Patel on February 8, 2024. Are you looking to enhance your understanding of social psychology through journal articles…

Understanding Construct Validity in Psychology: Definition and Examples

The article was last updated by Julian Torres on February 9, 2024. Construct validity is a crucial concept in psychology, but what exactly does it…

Understanding Mnemonic Devices in Psychology

The article was last updated by Dr. Henry Foster on February 8, 2024. Have you ever struggled to remember important information for a test or…

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.8: Blocks to Problem Solving

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 54768

- Mehgan Andrade and Neil Walker

- College of the Canyons

Sometimes, previous experience or familiarity can even make problem solving more difficult. This is the case whenever habitual directions get in the way of finding new directions – an effect called fixation.

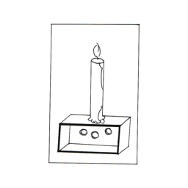

Functional Fixedness

Functional fixedness concerns the solution of object-use problems. The basic idea is that when the usual way of using an object is emphasised, it will be far more difficult for a person to use that object in a novel manner. An example for this effect is the candle problem : Imagine you are given a box of matches, some candles and tacks. On the wall of the room there is a cork- board. Your task is to fix the candle to the cork-board in such a way that no wax will drop on the floor when the candle is lit. – Got an idea?

Explanation: The clue is just the following: when people are confronted with a problem

and given certain objects to solve it, it is difficult for them to figure out that they could use them in a different (not so familiar or obvious) way. In this example the box has to be recognized as a support rather than as a container.

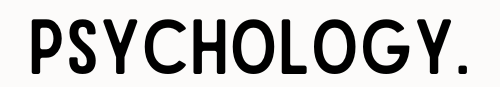

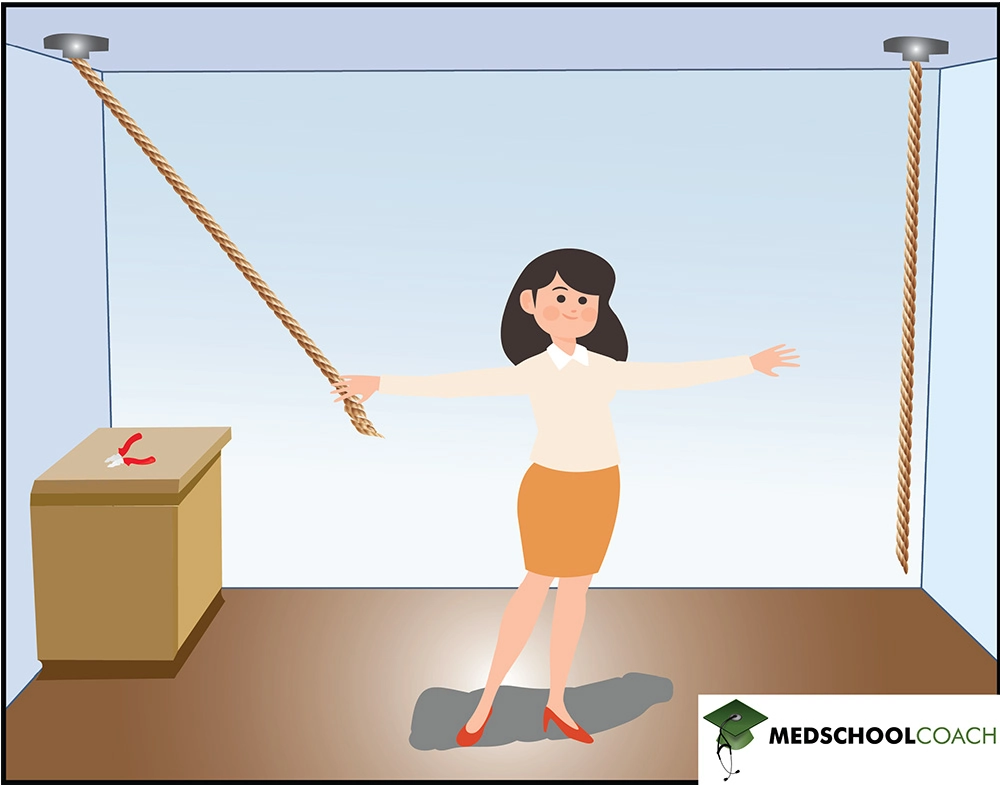

A further example is the two-string problem: Knut is left in a room with a chair and a pair of pliers given the task to bind two strings together that are hanging from the ceiling. The problem he faces is that he can never reach both strings at a time because they are just too far away from each other. What can Knut do?

Solution: Knut has to recognize he can use the pliers in a novel function – as weight for a pendulum. He can bind them to one of the strings, push it away, hold the other string and just wait for the first one moving towards him. If necessary, Knut can even climb on the chair, but he is not that small, we suppose…

Mental Fixedness

Functional fixedness as involved in the examples above illustrates a mental set - a person’s tendency to respond to a given task in a manner based on past experience. Because Knut maps an object to a particular function he has difficulties to vary the way of use (pliers as pendulum's weight). One approach to studying fixation was to study wrong-answer verbal insight problems. It was shown that people tend to give rather an incorrect answer when failing to solve a problem than to give no answer at all.

A typical example: People are told that on a lake the area covered by water lilies doubles every 24 hours and that it takes 60 days to cover the whole lake. Then they are asked how many days it takes to cover half the lake. The typical response is '30 days' (whereas 59 days is correct).

These wrong solutions are due to an inaccurate interpretation, hence representation, of the problem. This can happen because of sloppiness (a quick shallow reading of the problemand/or weak monitoring of their efforts made to come to a solution). In this case error feedback should help people to reconsider the problem features, note the inadequacy of their first answer, and find the correct solution. If, however, people are truly fixated on their incorrect representation, being told the answer is wrong does not help. In a study made by P.I. Dallop and R.L. Dominowski in 1992 these two possibilities were contrasted. In approximately one third of the cases error feedback led to right answers, so only approximately one third of the wrong answers were due to inadequate monitoring. [6] Another approach is the study of examples with and without a preceding analogous task. In cases such like the water-jug task analogous thinking indeed leads to a correct solution, but to take a different way might make the case much simpler:

Imagine Knut again, this time he is given three jugs with different capacities and is asked to measure the required amount of water. Of course he is not allowed to use anything despite the jugs and as much water as he likes. In the first case the sizes are 127 litres, 21 litres and 3 litres while 100 litres are desired. In the second case Knut is asked to measure 18 litres from jugs of 39, 15 and three litres size.

In fact participants faced with the 100 litre task first choose a complicate way in order tosolve the second one. Others on the contrary who did not know about that complex task solved the 18 litre case by just adding three litres to 15.

Pitfalls to Problem Solving

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but she just needs to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now. Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Link to Learning

Check out this Apollo 13 scene where the group of NASA engineers are given the task of overcoming functional fixedness.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and non-industrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

Common obstacles to solving problems

The example also illustrates two common problems that sometimes happen during problem solving. One of these is functional fixedness : a tendency to regard the functions of objects and ideas as fixed (German & Barrett, 2005). Over time, we get so used to one particular purpose for an object that we overlook other uses. We may think of a dictionary, for example, as necessarily something to verify spellings and definitions, but it also can function as a gift, a doorstop, or a footstool. For students working on the nine-dot matrix described in the last section, the notion of “drawing” a line was also initially fixed; they assumed it to be connecting dots but not extending lines beyond the dots. Functional fixedness sometimes is also called response set , the tendency for a person to frame or think about each problem in a series in the same way as the previous problem, even when doing so is not appropriate to later problems. In the example of the nine-dot matrix described above, students often tried one solution after another, but each solution was constrained by a set response not to extend any line beyond the matrix.

Functional fixedness and the response set are obstacles in problem representation , the way that a person understands and organizes information provided in a problem. If information is misunderstood or used inappropriately, then mistakes are likely—if indeed the problem can be solved at all. With the nine-dot matrix problem, for example, construing the instruction to draw four lines as meaning “draw four lines entirely within the matrix” means that the problem simply could not be solved. For another, consider this problem: “The number of water lilies on a lake doubles each day. Each water lily covers exactly one square foot. If it takes 100 days for the lilies to cover the lake exactly, how many days does it take for the lilies to cover exactly half of the lake?” If you think that the size of the lilies affects the solution to this problem, you have not represented the problem correctly. Information about lily size is not relevant to the solution, and only serves to distract from the truly crucial information, the fact that the lilies double their coverage each day. (The answer, incidentally, is that the lake is half covered in 99 days; can you think why?)

The Process of Problem Solving

- Editor's Choice

- Experimental Psychology

- Problem Solving

In a 2013 article published in the Journal of Cognitive Psychology , Ngar Yin Louis Lee (Chinese University of Hong Kong) and APS William James Fellow Philip N. Johnson-Laird (Princeton University) examined the ways people develop strategies to solve related problems. In a series of three experiments, the researchers asked participants to solve series of matchstick problems.

In matchstick problems, participants are presented with an array of joined squares. Each square in the array is comprised of separate pieces. Participants are asked to remove a certain number of pieces from the array while still maintaining a specific number of intact squares. Matchstick problems are considered to be fairly sophisticated, as there is generally more than one solution, several different tactics can be used to complete the task, and the types of tactics that are appropriate can change depending on the configuration of the array.

Louis Lee and Johnson-Laird began by examining what influences the tactics people use when they are first confronted with the matchstick problem. They found that initial problem-solving tactics were constrained by perceptual features of the array, with participants solving symmetrical problems and problems with salient solutions faster. Participants frequently used tactics that involved symmetry and salience even when other solutions that did not involve these features existed.

To examine how problem solving develops over time, the researchers had participants solve a series of matchstick problems while verbalizing their problem-solving thought process. The findings from this second experiment showed that people tend to go through two different stages when solving a series of problems.

People begin their problem-solving process in a generative manner during which they explore various tactics — some successful and some not. Then they use their experience to narrow down their choices of tactics, focusing on those that are the most successful. The point at which people begin to rely on this newfound tactical knowledge to create their strategic moves indicates a shift into a more evaluative stage of problem solving.

In the third and last experiment, participants completed a set of matchstick problems that could be solved using similar tactics and then solved several problems that required the use of novel tactics. The researchers found that participants often had trouble leaving their set of successful tactics behind and shifting to new strategies.

From the three studies, the researchers concluded that when people tackle a problem, their initial moves may be constrained by perceptual components of the problem. As they try out different tactics, they hone in and settle on the ones that are most efficient; however, this deduced knowledge can in turn come to constrain players’ generation of moves — something that can make it difficult to switch to new tactics when required.

These findings help expand our understanding of the role of reasoning and deduction in problem solving and of the processes involved in the shift from less to more effective problem-solving strategies.

Reference Louis Lee, N. Y., Johnson-Laird, P. N. (2013). Strategic changes in problem solving. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25 , 165–173. doi: 10.1080/20445911.2012.719021

good work for other researcher

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

Careers Up Close: Joel Anderson on Gender and Sexual Prejudices, the Freedoms of Academic Research, and the Importance of Collaboration

Joel Anderson, a senior research fellow at both Australian Catholic University and La Trobe University, researches group processes, with a specific interest on prejudice, stigma, and stereotypes.

Experimental Methods Are Not Neutral Tools

Ana Sofia Morais and Ralph Hertwig explain how experimental psychologists have painted too negative a picture of human rationality, and how their pessimism is rooted in a seemingly mundane detail: methodological choices.

APS Fellows Elected to SEP

In addition, an APS Rising Star receives the society’s Early Investigator Award.

Privacy Overview

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies