How to Write a Literacy Narrative Essay | Guide & Examples

22 December 2023

last updated

Mastering an art of writing requires students to have a guideline of how to write a good literacy narrative essay, emphasizing the details they should consider. This article begins by defining this type of academic document, its distinctive features, and its unique structure. Moreover, the guideline teaches students how to choose some topics and provides a sample outline and an example of a literacy narrative essay. Other crucial information is the technical details writers should focus on when writing a document, 10 things to do and not to do, and essential tips for producing a high-standard text. Therefore, reading this guideline benefits students and others because one gains critical insights that help to start writing a literacy narrative essay and want to meet a scholarly standard.

General Aspects of How to Write an Outstanding Literacy Narrative Essay

Learning how to write many types of essays should be a priority for any student hoping to be intellectually sharp. Besides being an exercise for academic assessment, writing is a platform for developing mental faculties, including intellect, memory, imagination, reason, and intuition. This guideline of how to write a literacy narrative, and this type of essay requires students to tell their story through the text. It defines a literacy narrative, distinctive text features, unique structure, possible topics students can choose from, and the technicality of writing this kind of text. There is also a sample outline and an example of a good literacy narrative essay. Hence, this guideline gives students critical insights for writing a high-standard literacy narrative essay.

Definition of What Is a Literacy Narrative Essay and Its Meaning

A literacy narrative is an essay that tells the writer’s personal story. It differs from other types of papers , including an argumentative essay , an analytical essay , a cause and effect essay , a report , or a research paper . While these other texts require students to borrow information from different sources to strengthen a thesis statement and back up claims, a literacy narrative means that students narrate an experience or event that has impacted them significantly. In other words, writers focus on one or several aspects of their lives and construct a story through the text. Therefore, when writing a literacy narrative essay, students should examine and reexamine their life course to identify experiences, events, or issues that stand out because they were pleasant or unpleasant. After identifying a memorable aspect of their life, students should use their accumulated knowledge to construct a narrative through speaking, reading, or writing.

Distinctive Features of a Literacy Narrative Essay

Every type of scholarly text has distinctive features that differentiate it from others. While some features may be standard among academic papers, most are not. Therefore, when writing a literacy narrative essay, students must first familiarize themselves with the features that make this kind of document distinct from others, like reports and research papers. With such knowledge, writers can know when to use an element when telling their personal stories through writing. Some distinctive features of a literacy narrative essay include a personal tone, a private tale, descriptive language, show-not-tell, active voice, similes and metaphors, and dialogue .

💠 Personal Tone

A personal tone is a quality that makes a narrative personal, meaning it is the writer telling the story. In this respect, students should use the first-person language, such as ‘I’ and ‘we,’ throughout the story. Using these terms makes the audience realize that the story is about the writer and those close to them, such as family, peers, and colleagues. The value of using a personal tone in writing a literacy narrative essay is that it reinforces the story’s theme, such as celebration or tragedy. In essence, people hearing, listening, or reading the story can appreciate its direct effect on the reader, speaker, or writer.

💠 Private Story

The essence of a literacy narrative essay is to tell a personal story. In this respect, telling people about a private experience, event, or issue gives this kind of text a narrative identity. Although the story people tell need not be about them, they must have been witnesses. For example, one can write a literacy narrative essay about their worst experience after joining college. Such a narrative should tell a private story involving the writer directly. Alternatively, people can write a literacy narrative essay about the day they witnessed corruption in public office. Such a narrative should not necessarily focus on the writer but on corrupt individuals in public office. Therefore, a private story should have the writer as the central character or a witness to an event.

💠 Descriptive Language

Since a literacy narrative essay is about a personal, private story that tells the writer’s experience, it is critical to provide details that help the audience to identify with the experience. Individuals can only do this activity by using descriptive language in their stories because the audience uses the information to imagine what they hear or read. An example of descriptive language is where, instead of writing, “I passed my aunt by the roadside as I headed home to inform others about the event,” one should write, “As I headed home to inform others about the happening, I came across my aunt standing on the roadside with a village elder in what seemed like a deep conversation about the event that had just transpired.” This latter statement is rich with information the audience can use to imagine the situation.

💠 Show-Not-Tell

A literacy narrative essay aims to help the audience to recreate the writer’s experience in their minds. As such, they focus less on telling the audience what happened and more on ‘showing’ them how events unfolded. A practical method for doing this activity is comprehensively narrating experiences and events. For example, authors should not just write about how an experience made them feel, but they should be thorough in their narration by telling how the feeling affected them, such as influencing them to do something. As a result, a literacy narrative essay allows writers to show the audience how past experiences, events, or situations affected them or influenced their worldviews.

💠 Active Voice

Academic writing conventions demand that students write non-scientific scholarly documents, including literacy narrative essays, in the active voice, meaning writing in a form where the subject of a sentence performs the action. Practically, it should follow the following format: subject + verb + object. For example, this arrangement makes the sentence easy to read but, most importantly, keeps meanings in sentences clear and avoids complicating sentences or making them too wordy. The opposite of the active voice is the passive voice, which is common in scientific papers. The following sentence exemplifies the active voice: “The young men helped the old lady climb the stairs.” A passive voice would read: “The old woman was helped by the young men to climb up the stairs.” As is evidence, the active voice is simple, straightforward, and short as opposed to the passive voice.

💠 Similes and Metaphors

Similes and metaphors are literary devices or figures of speech writers use to compare two things that are not alike in literacy narrative essays. The point of difference between these aspects is that similes compare two things by emphasizing one thing is like something else, while metaphors emphasize one thing is something else. Simply put, similes use the terms ‘is like’ or ‘is as…as’ to emphasize comparison between two things. A metaphor uses the word ‘is’ to highlight the comparison. Therefore, when writing a literary narrative essay, students should incorporate similes by saying, “Friendship is like a flowery garden,” meaning friendship is pleasant. An example of a metaphor one can use is the statement: “My uncle’s watch is a dinosaur,” meaning it is ancient, a relic.

Dialogue is communication between two or more people familiar with plays, films, or novels. The purpose of this kind of communication is to show the importance of an issue to different people. Generally, discussions are the most common platforms for dialogue because individuals can speak their minds and hear what others say about the same problem. Dialogue is a distinctive feature of a literacy narrative essay because it allows writers to show-not-tell. Authors can show readers how their interaction with someone moved from pleasant to unpleasant through dialogue. Consequently, dialogue can help readers to understand the writer’s attitudes, mindset, or state of mind during an event described in the text. As such, incorporating a dialogue in a literacy narrative essay makes the text personal to the writer and descriptive to the reader.

Join our satisfied customers who have received perfect papers from Wr1ter Team.

Unique Structure of a Literacy Narrative Essay

Besides the distinctive features above, a literacy narrative is distinct from other types of scholarly documents because it has a unique essay structure . In academic writing, a text’s structure denotes essay outline that writers adopt to produce the work. For example, it is common knowledge that essays should have three sections: introduction, body, and conclusion . In the same way, literacy narratives, which also follow this outline, have a structure, which students should demonstrate in the body. The structure addresses a literacy issue, solution, lesson, and summary . This structure allows writers to produce a coherent paper that readers find to have a logical flow of ideas.

1️⃣ Literacy Issue

A literacy issue signifies a problem or struggles for the writer and is the personal or private issue that the narrative focuses on. Ideally, students use this issue to give the audience a sneak peek into their personalities and private life. Most literacy issues are personal experiences involving a problem or struggle and their effect on the writer and those close to them, like family members or friends. Therefore, when writing a literacy narrative essay, students should identify personal problems or struggles in their past and make them the paper’s focal subject.

2️⃣ Solution

The solution element in a literacy narrative essay describes how writers overcame their problems or managed personal struggles. Simply put, it is where authors tell and show readers how they solved the personal, private issue that is the paper’s subject. Such information is crucial to readers because they need to know what happened to the writer, who they see as the hero or protagonist of the story. For example, literacy narratives are informative because they show the audience how writers dealt with a problem or struggle and how they can use the same strategy to overcome their examples. From this perspective, students should write a literacy narrative essay to inform and empower readers through insights that are relevant and applicable to one’s life.

The lesson element is the message readers get from the writer’s narrative about a literacy issue and its solution. For example, students can talk about how lacking confidence affects their social life by undermining their ability to create and nurture friendships. This problem is personal and becomes a literacy issue. Then, they show readers how they dealt with the situation, such as reading books and articles on building personal confidence. Writers should use practical examples of how they solved their problems or struggles. Overall, including all the information about the unique situation or struggle and the solution helps readers to learn a lesson, what they take away after reading the text. As such, students should know that their literacy narrative essays must have a lesson for their readers.

4️⃣ Summary

The summary element briefly describes a personal experience and its effects. Every literacy narrative essay must summarize the writer’s experience to allow readers to judge, such as learning the value of something. When summarizing their personal story, such as an experience, students should understand that the summary must be brief but detailed enough to allow readers to put themselves in their place. In other words, the summary must be relevant to the reader and the broader society. The most crucial element in the summary is emphasizing the lesson from the personal issue by telling how the writer addressed the personal issue.

Examples of Famous Literacy Narrative Essays

Research is an essential activity that helps writers to find credible sources to support their work. When writing literacy narrative essays, students should adopt this approach to find famous literacy narratives and discover what makes them popular in the literary world. Students should focus on how writers adopt the unique structure described above. The list below highlights five popular literacy narratives because they are high-standard texts.

Learning to Read by Malcolm X

Malcolm X’s Learning to Read is a literacy narrative that describes his journey to enlightenment. The text reflects the unique structure of a literacy narrative because it communicates a personal issue, the solution to the problem, a lesson to the reader, and a summary of the writer’s experience. For example, the literacy issue is the writer’s hardships that inspired his journey to becoming a literate activist. After dropping from school at a young age, Malcolm X committed a crime that led to his imprisonment. The solution to his hardships was knowledge, and he immersed himself in education by reading in the prison library, gaining essential knowledge that helped him to confront his reality. The lesson is that education is transformative, and people can educate themselves from ignorance to enlightenment. The summary is that personal struggles are a ladder to more extraordinary life achievements.

Scars: A Life in Injuries by David Owen

David Owen’s Scars: A Life in Injuries is a literacy narrative that adopts the unique structure above. The literacy issue in the story is Owen’s scars, including over ten injuries and witnessing Duncan’s traumas. For example, the solution that the article proposes for dealing with personal scars is finding a purpose in each. The text describes how Owen saw each scar not as bad but as something that gave him a reason to live. The lesson is that scars are not just injuries but stories people can tell others to give hope and a reason for living. The summary is that life’s misfortunes should not be a reason to give up but a motivation to press on. It clarifies that, while misfortunes can lead to despair, one must be bold enough to see them as scars, not disabilities.

Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son reflects the writer’s tense relationship with his father in the context of racial tension that gripped New York City in the mid-20th century. The story fits the unique structure of a literacy narrative. The personal issue in the text is the writer’s tense relationship with his father. The solution to this struggle is accepting life as it is and humans as they are, not struggling to change anyone or anything. For example, the lesson in the text is that the family can cause pain and anguish, and the best people can do is not to let others influence their feelings, attitude, behaviors, or motivations in life. The summary is that people’s struggles are a fire that sparks a revolution of ideas that uplift them and others in the broader society.

Dreams From My Father by Barack Obama

Barack Obama’s Dreams From My Father is the story of the writer’s search for his biracial identity that satisfies the unique structure of a literacy narrative. For example, the personal issue in the text is Obama’s desire to understand the forces that shaped him and his father’s legacy, which propelled him to travel to Kenya. The journey exposed him to brutal poverty and tribal conflict and a community with an enduring spirit. The solution to this personal struggle is becoming a community organizer in the tumultuous political and racial strife that birthed despair in the inner cities. The reader learns that community is valuable in healing wounds that can lead to distress. The summary is that family is crucial to one’s identity, and spending time to know one’s background is helpful for a purposeful and meaningful life.

A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast recalls the writer’s time in Paris during the 1920s. The personal issue in the text is dealing with a changing Paris. The solution to the writer’s struggle was to build a network of friends and use them as a study. For example, the text summarizes the writer’s story by discussing his relationships, including befriending Paul Cézanne, Ezra Pound, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. He found some unpleasant and others very hedonistic. The reader learns from the text that friendships are vital in one’s professional journey because they provide insights into the attitudes that make up the human community. The summary is that one’s friendships are crucial in social and intellectual development, despite the weaknesses of some friends.

Topic Examples for Writing a Good Literacy Narrative Essay

Since students may get a chance to write a literacy narrative essay, they should learn how to choose good essay topics . Typically, students receive instructions specifying the topic, but, sometimes, such specifications may be lacking. In such an instance, one must know how to choose a good theme from lists of popular narrative essay topics or personal essay topics . For example, the best approach in selecting a subject is to read widely while noting valuable ideas. These aspects are a good starting point when deciding the subject of a literacy narrative essay. The following list provides easy topics for this kind of scholarly paper because they require students to tell a personal story, addressing the elements of the unique structure.

- Overcoming a Fear That Changed My Life

- A Memorable Day in Winter

- My Experience in an Adventure in Africa

- The Greatest Lessons in Friendship

- My Family Is My Anchor

- The Day I Will Never Forget

- My Life as a Community Advocate

- Delving Into the Enigma of Alternate Universes: A Hypothetical Journey

Receive a high-quality paper without plagiarism from Wr1ter Team.

Sample Outline Template for Writing a Literacy Narrative Essay

I. College Essay Introduction

- A hook : An exciting statement to grab the reader’s attention.

- Background of the topic.

- A thesis that states the topic’s significance to the writer and reader.

A. Literacy Issue:

- State the literacy issue that signifies a personal problem, struggle, or issue.

B. Solution

- Give some background information about the literacy issue.

- Describe the setting of the literacy issue.

- Mention some characters involved in solving the literacy issue.

- Give a short story about the literacy issue and its significance.

D. Summary:

- State the outcomes of the literacy issue through detailed language.

III. Conclusion Examples

- Restate the thesis.

- State the outcome and the lesson.

Example of a Literacy Narrative Essay

Topic: My Life as a Community Advocate

I. Example of an Introduction of a Literacy Narrative Essay

Community service is a noble idea that should form part of every person’s life mantra. The context of community is the myriad social issues that may undermine people’s quality of life without adequate interventions. My life as a community advocate is about how I have helped to address social issues without holding any public office, evidence that all one needs is love, concern, focus, and commitment.

II. Examples of Body Paragraphs of a Literacy Narrative Essay

A. literacy issue sample paragraph.

Community service is a noble duty every person should view as an intervention against social problems that potentially undermine the quality of life of vulnerable groups in society, such as children, persons living with disabilities, and senior citizens. Community advocacy is standing up for the community in critical forums where decision-makers gather. As such, my life as a community advocate involves attending community meetings, political gatherings, seminars, and any association that consists of an interaction between ordinary people and those in leadership. My goal in such meetings is to raise issues affecting vulnerable groups in my community, which need more attention from local, state, or national leadership.

B. Solution Sample Paragraph

My life as a community advocate happens in the community where I live and any place where leaders with the power to change the community’s political, economic, and social architecture gather. In this respect, people involved in my role as a community advocate include elected leaders at the local, state, and national levels and leaders of various groups, including senior citizens and persons with disabilities. I also interact with school administrators, social workers, and health professionals like psychologists. These people are valuable in providing insights into different groups’ challenges and what is missing to make their lives satisfactory, if not better. It is common knowledge that vulnerable groups are significantly disadvantaged across dimensions of life, including employment, healthcare, and leadership. Therefore, my life as a community advocate focuses on being a voice for these groups in forums where those with the potential to improve their experiences and outcomes are present.

C. Lesson Sample Paragraph

An event that makes me proud of being a community advocate is when I helped to create a school-based program for children from low-income households below the age of five in my county. The program’s objective was to feed children and provide essential amenities they lacked due to their parent’s or guardians’ economic circumstances. Over time, I have learned that several counties across the state have adopted the program and made the lives of vulnerable children promising.

D. Summary Sample Paragraph

I took part in activities and improved the quality of health support for children. I have learned from several clinicians and social workers that children in the program have shown improved scores in body immunity because of good nutrition. Such news makes me proud to be a community advocate and continue being a voice for the voiceless in a society where politicians have prioritized self-interests in local, state, and national leadership.

III. Example of a Conclusion of a Literacy Narrative Essay

My life as a community advocate has shown me that people can solve social problems without minding their position in the community. The only tools I have used are love, concern, focus, and commitment to make the lives of vulnerable groups satisfactory, if not better. Looking back, I feel proud knowing I have helped vulnerable children to experience a life they may have missed if no one showed love and care. My community advocacy is evidence that people can solve social problems by caring.

4 Easy Steps for Writing a Great Literacy Narrative Essay

Writing a literacy narrative essay is a technical exercise that involves several steps. Each step requires writers to demonstrate sufficient knowledge of how to write this type of scholarly document. In essence, the technical details of writing a good literacy narrative essay are the issues one must address in each step of writing: preparation, stage setup, writing a first draft, and wrap-up. Although not every detail applies in a literacy narrative, most do, and students must grasp all for an improved understanding of what writing a high-standard academic document means.

Step 1: Preparation

Preparation is the first step in starting a literacy narrative essay. One technical detail students should address is defining a specific topic. Typically, instructors choose the topic, but students can select one if such a specification is lacking. For example, the best way to choose a topic is research, where one searches for documents, including famous narratives, on the Internet, using online databases. The second technical detail is to generate ideas, which means reading reliable sources while making notes. In this task, one should consider the audience to determine whether to use simple or technical language.

Step 2: Stage Set Up

Setting the stage is the second step in writing a literacy narrative essay. The first technical detail one needs to address is to create a well-organized outline according to the one above. For example, this task helps writers to assess their ideas to see whether they are sufficient for each paper section. The second technical detail is gathering stories by recalling experiences and events significantly affecting one’s life. The last technical point is constructing a hook, a statement that will help the text to grab readers’ attention from the start.

Step 3: Writing a First Draft

Writing a first draft of a literacy narrative essay is the third step in this activity. The first technical detail students should address is creating a draft. This text is the first product of the writing process and helps writers to judge their work. For example, the main issue is whether they have used all the ideas to construct a compelling narrative. The answer will determine if they will add new ideas or delete some, meaning adding or deleting academic sources. Whatever the outcome, writers may have to alter clear outlines to fit all the ideas necessary to make papers compelling and high-standard.

Writing an Introduction for a Literacy Analysis Essay

Students should focus on three outcomes when writing a good introduction: a hook, context, and thesis. The hook is a statement that captures the reader’s attention. As such, one must use a quote, fact, or question that triggers the reader’s interest to want to read more. Context is telling readers why the topic is vital to write about. A thesis is a statement that summarizes the writer’s purpose for writing a literacy narrative essay.

Writing a Body for a Literacy Analysis Essay

Writing the body part of a literacy narrative essay requires addressing the essential elements of a unique structure. The first element is to state a personal issue and make it the center of the narrative. The best approach is to look into the past and identify an experience or event with a lasting impact. The second element is a solution to the problem or struggle resulting from the personal issue. Therefore, writers should identify personal problems that expose them to conflict with others or social structures and systems. The third element is a lesson, how the personal issue and the solution affect the writer and potentially the reader. The last element is a summary, where authors conclude by giving readers a life perspective relating to the personal story.

Writing a Conclusion for a Literacy Analysis Essay

When writing a conclusion part for a literacy narrative essay, students should summarize the story by reemphasizing the thesis, the personal issue, and the lesson learned. Ideally, the goal of this section is not to introduce new ideas but reinforce what the paper has said and use the main points to conclude the story. As such, writers should not leave readers with questions but give information that allows them to draw a good lesson from the text.

Step 4: Wrap Up

The last step in writing a literacy narrative essay is wrapping up a final draft. The first technical detail students should address is revising the sections without a logical order of ideas. Ideally, one should read and reread their work to ensure the sentences and paragraphs make logical sense. For example, this task should ensure all body paragraphs have a topic sentence , a concluding sentence, and a transition. The next technical detail is editing a final draft by adding or deleting words and fixing grammar and format errors. Lastly, writers should confirm that a literary narrative essay adopts a single formatting style from beginning to end. Content in literacy narratives includes block quotes and dialogue. Students should format them appropriately as follows:

- Block quotes: Select the text to quote, click “Layout” on the ribbon, set the left indent to 0.5cm, click the “Enter” key, then use the arrows in the indent size box to increase or decrease the indentation.

- Dialogue: Use quotation marks to start and end spoken dialogue and create a new paragraph for each speaker.

20 Tips for Writing a Literacy Narrative Essay

Writing a literacy narrative essay requires students to learn several tips. These elements include choosing topics that are meaningful to the writer, generating ideas from the selected themes and putting them in sentence form, creating a clear outline and populating it with the ideas, writing the first draft that reflects the unique structure (literacy issue, solution, lesson, and summary), reading and rereading the draft, revising and editing the draft to produce a high-quality literacy narrative essay, proofreading the document.

10 things to do when writing a literacy narrative essay include:

- developing a hook to grab the readers’ attention,

- writing in paragraphs ,

- using the correct grammar,

- incorporating verbs that trigger the reader’s interest,

- showing rather than telling by using descriptive language,

- incorporating a dialogue,

- varying sentence beginnings,

- following figurative speech,

- formatting correctly,

- rereading the text.

10 things not to do include:

- choosing an irrelevant topic that does not stir interest in the reader,

- presenting a long introduction,

- providing a thesis that does not emphasize a personal issue,

- writing paragraphs without topic sentences and transitions,

- ignoring the unique structure of a literacy narrative essay (literacy issue, solution, lesson, and summary),

- focusing on too many personal experiences or events,

- using several formatting styles,

- writing sentences without logical sense,

- finalizing a document with multiple grammatical and formatting mistakes,

- not concluding the narrative by reemphasizing the thesis and lesson learned.

Summing Up on How to Write a Perfect Literacy Narrative Essay

- For writing a good literacy narrative essay, think of a personal experience or an event with a lasting impact.

- Use descriptive language to narrate the experience or event.

- Identify a conflict in the experience or event.

- State how the conflict shaped your perspective.

- Provide a solution to the conflict.

- Mention the setting of the personal experience or event, including people or groups involved.

- State the significance of the experience or event to people and groups involved and the broader society.

To Learn More, Read Relevant Articles

Roles of ethics in artificial intelligence, balancing school curriculum: is art education as important as science.

Chapter 1. What is Literacy? Multiple Perspectives on Literacy

Constance Beecher

“Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” – Frederick Douglass

Download Tar Beach – Faith Ringgold Video Transcript [DOC]

Keywords: literacy, digital literacy, critical literacy, community-based literacies

Definitions of literacy from multiple perspectives

Literacy is the cornerstone of education by any definition. Literacy refers to the ability of people to read and write (UNESCO, 2017). Reading and writing in turn are about encoding and decoding information between written symbols and sound (Resnick, 1983; Tyner, 1998). More specifically, literacy is the ability to understand the relationship between sounds and written words such that one may read, say, and understand them (UNESCO, 2004; Vlieghe, 2015). About 67 percent of children nationwide, and more than 80 percent of those from families with low incomes, are not proficient readers by the end of third grade ( The Nation Assessment for Educational Progress; NAEP 2022 ). Children who are not reading on grade level by third grade are 4 times more likely to drop out of school than their peers who are reading on grade level. A large body of research clearly demonstrates that Americans with fewer years of education have poorer health and shorter lives. In fact, since the 1990s, life expectancy has fallen for people without a high school education. Completing more years of education creates better access to health insurance, medical care, and the resources for living a healthier life (Saha, 2006). Americans with less education face higher rates of illness, higher rates of disability, and shorter life expectancies. In the U.S., 25-year-olds without a high school diploma can expect to die 9 years sooner than college graduates. For example, by 2011, the prevalence of diabetes had reached 15% for adults without a high -school education, compared with 7% for college graduates (Zimmerman et al., 2018).

Thus, literacy is a goal of utmost importance to society. But what does it mean to be literate, or to be able to read? What counts as literacy?

Learning Objectives

- Describe two or more definitions of literacy and the differences between them.

- Define digital and critical literacy.

- Distinguish between digital literacy, critical literacy, and community-based literacies.

- Explain multiple perspectives on literacy.

Here are some definitions to consider:

“Literacy is the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate, and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society.” – United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

“The ability to understand, use, and respond appropriately to written texts.” – National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), citing the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC)

“An individual’s ability to read, write, and speak in English, compute, and solve problems, at levels of proficiency necessary to function on the job, in the family of the individual, and in society.” – Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), Section 203

“The ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate, and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society.” – Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), as cited by the American Library Association’s Committee on Literacy

“Using printed and written information to function in society, to achieve one’s goals, and to develop one’s knowledge and potential.” – Kutner, Greenberg, Jin, Boyle, Hsu, & Dunleavy (2007). Literacy in Everyday Life: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2007-480)

Which one of these above definitions resonates with you? Why?

New literacy practices as meaning-making practices

In the 21 st century, literacy increasingly includes understanding the roles of digital media and technology in literacy. In 1996, the New London Group coined the term “multiliteracies” or “new literacies” to describe a modern view of literacy that reflected multiple communication forms and contexts of cultural and linguistic diversity within a globalized society. They defined multiliteracies as a combination of multiple ways of communicating and making meaning, including such modes as visual, audio, spatial, behavioral, and gestural (New London Group, 1996). Most of the text’s students come across today are digital (like this textbook!). Instead of books and magazines, students are reading blogs and text messages.

For a short video on the importance of digital literacy, watch The New Media Literacies .

The National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE, 2019) makes it clear that our definitions of literacy must continue to evolve and grow ( NCTE definition of digital literacy ).

“Literacy has always been a collection of communicative and sociocultural practices shared among communities. As society and technology change, so does literacy. The world demands that a literate person possess and intentionally apply a wide range of skills, competencies, and dispositions. These literacies are interconnected, dynamic, and malleable. As in the past, they are inextricably linked with histories, narratives, life possibilities, and social trajectories of all individuals and groups. Active, successful participants in a global society must be able to:

- participate effectively and critically in a networked world.

- explore and engage critically and thoughtfully across a wide variety of inclusive texts and tools/modalities.

- consume, curate, and create actively across contexts.

- advocate for equitable access to and accessibility of texts, tools, and information.

- build and sustain intentional global and cross-cultural connections and relationships with others to pose and solve problems collaboratively and strengthen independent thought.

- promote culturally sustaining communication and recognize the bias and privilege present in the interactions.

- examine the rights, responsibilities, and ethical implications of the use and creation of information.

- determine how and to what extent texts and tools amplify one’s own and others’ narratives as well as counterproductive narratives.

- recognize and honor the multilingual literacy identities and culture experiences individuals bring to learning environments, and provide opportunities to promote, amplify, and encourage these variations of language (e.g., dialect, jargon, and register).”

In other words, literacy is not just the ability to read and write. It is also being able to effectively use digital technology to find and analyze information. Students who are digitally literate know how to do research, find reliable sources, and make judgments about what they read online and in print. Next, we will learn more about digital literacy.

- Malleable : can be changed.

- Culturally sustaining : the pedagogical preservation of the cultural and linguistic competence of young people pertaining to their communities of origin while simultaneously affording dominant-culture competence.

- Bias : a tendency to believe that some people, ideas, etc., are better than others, usually resulting in unfair treatment.

- Privilege : a right or benefit that is given to some people and not to others.

- Unproductive narrative : negative commonly held beliefs such as “all students from low-income backgrounds will struggle in school.” (Narratives are phrases or ideas that are repeated over and over and become “shared narratives.” You can spot them in common expressions and stories that almost everyone knows and holds as ingrained values or beliefs.)

Literacy in the digital age

The Iowa Core recognizes that today, literacy includes technology. The goal for students who graduate from the public education system in Iowa is:

“Each Iowa student will be empowered with the technological knowledge and skills to learn effectively and live productively. This vision, developed by the Iowa Core 21st Century Skills Committee, reflects the fact that Iowans in the 21st century live in a global environment marked by a high use of technology, giving citizens and workers the ability to collaborate and make individual contributions as never before. Iowa’s students live in a media-suffused environment, marked by access to an abundance of information and rapidly changing technological tools useful for critical thinking and problem-solving processes. Therefore, technological literacy supports preparation of students as global citizens capable of self-directed learning in preparation for an ever-changing world” (Iowa Core Standards 21 st Century Skills, n.d.).

NOTE: The essential concepts and skills of technology literacy are taken from the International Society for Technology in Education’s National Educational Technology Standards for Students: Grades K-2 | Technology Literacy Standards

Literacy in any context is defined as the ability “ to access, manage, integrate, evaluate, and create information in order to function in a knowledge society” (ICT Literacy Panel, 2002). “ When we teach only for facts (specifics)… rather than for how to go beyond facts, we teach students how to get out of date ” (Sternberg, 2008). This statement is particularly significant when applied to technology literacy. The Iowa essential concepts for technology literacy reflect broad, universal processes and skills.

Unlike the previous generations, learning in the digital age is marked using rapidly evolving technology, a deluge of information, and a highly networked global community (Dede, 2010). In such a dynamic environment, learners need skills beyond the basic cognitive ability to consume and process language. To understand the characteristics of the digital age, and what this means for how people learn in this new and changing landscape, one may turn to the evolving discussion of literacy or, as one might say now, of digital literacy. The history of literacy contextualizes digital literacy and illustrates changes in literacy over time. By looking at literacy as an evolving historical phenomenon, we can glean the fundamental characteristics of the digital age. These characteristics in turn illuminate the skills needed to take advantage of digital environments. The following discussion is an overview of digital literacy, its essential components, and why it is important for learning in the digital age.

Literacy is often considered a skill or competency. Children and adults alike can spend years developing the appropriate skills for encoding and decoding information. Over the course of thousands of years, literacy has become much more common and widespread, with a global literacy rate ranging from 81% to 90% depending on age and gender (UNESCO, 2016). From a time when literacy was the domain of an elite few, it has grown to include huge swaths of the global population. There are several reasons for this, not the least of which are some of the advantages the written word can provide. Kaestle (1985) tells us that “literacy makes it possible to preserve information as a snapshot in time, allows for recording, tracking and remembering information, and sharing information more easily across distances among others” (p. 16). In short, literacy led “to the replacement of myth by history and the replacement of magic by skepticism and science.”

If literacy involves the skills of reading and writing, digital literacy requires the ability to extend those skills to effectively take advantage of the digital world (American Library Association [ALA], 2013). More general definitions express digital literacy as the ability to read and understand information from digital sources as well as to create information in various digital formats (Bawden, 2008; Gilster, 1997; Tyner, 1998; UNESCO, 2004). Developing digital skills allows digital learners to manage a vast array of rapidly changing information and is key to both learning and working in the evolving digital landscape (Dede, 2010; Koltay, 2011; Mohammadyari & Singh, 2015). As such, it is important for people to develop certain competencies specifically for handling digital content.

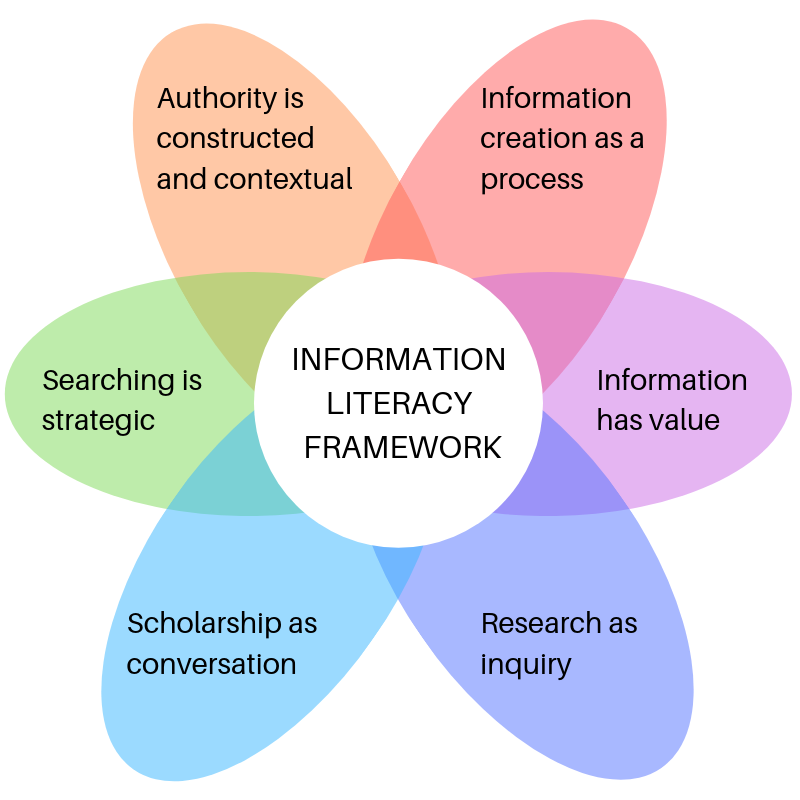

ALA Digital Literacy Framework

To fully understand the many digital literacies, we will look at the American Library Association (ALA) framework. The ALA framework is laid out in terms of basic functions with enough specificity to make it easy to understand and remember but broad enough to cover a wide range of skills. The ALA framework includes the following areas:

- understanding,

- evaluating,

- creating, and

- communicating (American Library Association, 2013).

Finding information in a digital environment represents a significant departure from the way human beings have searched for information for centuries. The learner must abandon older linear or sequential approaches to finding information such as reading a book, using a card catalog, index, or table of contents, and instead use more horizontal approaches like natural language searches, hypermedia text, keywords, search engines, online databases and so on (Dede, 2010; Eshet, 2002). The shift involves developing the ability to create meaningful search limits (SCONUL, 2016). Previously, finding the information would have meant simply looking up page numbers based on an index or sorting through a card catalog. Although finding information may depend to some degree on the search tool being used (library, internet search engine, online database, etc.) the search results also depend on how well a person is able to generate appropriate keywords and construct useful Boolean searches. Failure in these two areas could easily return too many results to be helpful, vague, or generic results, or potentially no useful results at all (Hangen, 2015).

Part of the challenge of finding information is the ability to manage the results. Because there is so much data, changing so quickly, in so many different formats, it can be challenging to organize and store them in such a way as to be useful. SCONUL (2016) talks about this as the ability to organize, store, manage, and cite digital resources, while the Educational Testing Service also specifically mentions the skills of accessing and managing information. Some ways to accomplish these tasks is using social bookmarking tools such as Diigo, clipping and organizing software such as Evernote and OneNote, and bibliographic software. Many sites, such as YouTube, allow individuals with an account to bookmark videos, as well as create channels or collections of videos for specific topics or uses. Other websites have similar features.

Understanding

Understanding in the context of digital literacy perhaps most closely resembles traditional literacy because it is the ability to read and interpret text (Jones-Kavalier & Flannigan, 2006). In the digital age, however, the ability to read and understand extends much further than text alone. For example, searches may return results with any combination of text, video, sound, and audio, as well as still and moving pictures. As the internet has evolved, a whole host of visual languages have also evolved, such as moving images, emoticons, icons, data visualizations, videos, and combinations of all the above. Lankshear & Knoble (2008) refer to these modes of communication as “post typographic textual practice.” Understanding the variety of modes of digital material may also be referred to as multimedia literacy (Jones-Kavalier & Flannigan, 2006), visual literacy (Tyner, 1998), or digital literacy (Buckingham, 2006).

Evaluating digital media requires competencies ranging from assessing the importance of a piece of information to determining its accuracy and source. Evaluating information is not new to the digital age, but the nature of digital information can make it more difficult to understand who the source of information is and whether it can be trusted (Jenkins, 2018). When there are abundant and rapidly changing data across heavily populated networks, anyone with access can generate information online. This results in the learner needing to make decisions about its authenticity, trustworthiness, relevance, and significance. Learning evaluative digital skills means learning to ask questions about who is writing the information, why they are writing it, and who the intended audience is (Buckingham, 2006). Developing critical thinking skills is part of the literacy of evaluating and assessing the suitability for use of a specific piece of information (SCONUL, 2016).

Creating in the digital world makes the production of knowledge and ideas in digital formats explicit. While writing is a critical component of traditional literacy, it is not the only creative tool in the digital toolbox. Other tools are available and include creative activities such as podcasting, making audio-visual presentations, building data visualizations, 3D printing, and writing blogs. Tools that haven’t been thought of before are constantly appearing. In short, a digitally literate individual will want to be able to use all formats in which digital information may be conveyed in the creation of a product. A key component of creating with digital tools is understanding what constitutes fair use and what is considered plagiarism. While this is not new to the digital age, it may be more challenging these days to find the line between copying and extending someone else’s work.

In part, the reason for the increased difficulty in discerning between plagiarism and new work is the “cut and paste culture” of the Internet, referred to as “reproduction literacy” (Eshet 2002, p.4), or appropriation in Jenkins’ New Media Literacies (Jenkins, 2018). The question is, what kind and how much change is required to avoid the accusation of plagiarism? This skill requires the ability to think critically, evaluate a work, and make appropriate decisions. There are tools and information to help understand and find those answers, such as the Creative Commons. Learning about such resources and how to use them is part of digital literacy.

Communicating

Communicating is the final category of digital skills in the ALA digital framework. The capacity to connect with individuals all over the world creates unique opportunities for learning and sharing information, for which developing digital communication skills is vital. Some of the skills required for communicating in the digital environment include digital citizenship, collaboration, and cultural awareness. This is not to say that one does not need to develop communication skills outside of the digital environment, but that the skills required for digital communication go beyond what is required in a non-digital environment. Most of us are adept at personal, face- to-face communication, but digital communication needs the ability to engage in asynchronous environments such as email, online forums, blogs, social media, and learning platforms where what is written may not be deleted and may be misinterpreted. Add that to an environment where people number in the millions and the opportunities for misunderstanding and cultural miscues are likely.

The communication category of digital literacies covers an extensive array of skills above and beyond what one might need for face-to-face interactions. It is comprised of competencies around ethical and moral behavior, responsible communication for engagement in social and civic activities (Adam Becker et al., 2017), an awareness of audience, and an ability to evaluate the potential impact of one’s online actions. It also includes skills for handling privacy and security in online environments. These activities fall into two main categories: digital citizenship and collaboration.

Digital citizenship refers to one’s ability to interact effectively in the digital world. Part of this skill is good manners, often referred to as “netiquette.” There is a level of context which is often missing in digital communication due to physical distance, lack of personal familiarity with the people online, and the sheer volume of the people who may encounter our words. People who know us well may understand exactly what we mean when we say something sarcastic or ironic, but people online do not know us, and vocal and facial cues are missing in most digital communication, making it more likely we will be misunderstood. Furthermore, we are more likely to misunderstand or be misunderstood if we are unaware of cultural differences. So, digital citizenship includes an awareness of who we are, what we intend to say, and how it might be perceived by other people we do not know (Buckingham, 2006). It is also a process of learning to communicate clearly in ways that help others understand what we mean.

Another key digital skill is collaboration, and it is essential for effective participation in digital projects via the Internet. The Internet allows people to engage with others they may never see in person and work towards common goals, be they social, civic, or business oriented. Creating a community and working together requires a degree of trust and familiarity that can be difficult to build when there is physical distance between the participants. Greater effort must be made to be inclusive , and to overcome perceived or actual distance and disconnectedness. So, while the potential of digital technology for connecting people is impressive, it is not automatic or effortless, and it requires new skills.

Literacy narratives are stories about reading or composing a message in any form or context. They often include poignant memories that involve a personal experience with literacy. Digital literacy narratives can sometimes be categorized as ones that focus on how the writer came to understand the importance of technology in their life or pedagogy. More often, they are simply narratives that use a medium beyond the print-based essay to tell the story:

Create your own literacy narrative that tells of a significant experience you had with digital literacy. Use a multi-modal tool that includes audio and images or video. Share it with your classmates and discuss the most important ideas you notice in each other’s narratives.

Critical literacy

Literacy scholars recognize that although literacy is a cognitive skill, it is also a set of practices that communities and people participate in. Next, we turn to another perspective on literacy – critical literacy. “Critical” here is not meant as having a negative point of view, but rather using an analytic lens that detects power, privilege, and representation to understand different ways of looking at texts. For example, when groups or individuals stage a protest, do the media refer to them as “protesters” or “rioters?” What is the reason for choosing the label they do, and what are the consequences?

Critical literacy does not have a set definition or typical history of use, but the following key tenets have been described in the literature, which will vary in their application based on the individual social context (Vasquez, 2019). Table 1 presents some key aspects of critical literacy, but this area of literacy research is growing and evolving rapidly, so this is not an exhaustive list.

An important component of critical literacy is the adoption of culturally responsive and sustaining pedagogy. One definition comes from Dr. Django Paris (2012), who stated that Culturally Responsive-Sustaining (CR-S) education recognizes that cultural differences (including racial, ethnic, linguistic, gender, sexuality, and ability ones) should be treated as assets for teaching and learning. Culturally sustaining pedagogy requires teachers to support multilingualism and multiculturalism in their practice. That is, culturally sustaining pedagogy seeks to perpetuate and foster—to sustain—linguistic, literary, and cultural pluralism as part of the democratic project of schooling.

For more, see the Culturally Responsive and Sustaining F ramework . The framework helps educators to think about how to create student-centered learning environments that uphold racial, linguistic, and cultural identities. It prepares students for rigorous independent learning, develops their abilities to connect across lines of difference, elevates historically marginalized voices, and empowers them as agents of social change. CR-S education explores the relationships between historical and contemporary conditions of inequality and the ideas that shape access, participation, and outcomes for learners.

- What can you do to learn more about your students’ cultures?

- How can you build and sustain relationships with your students?

- How do the instructional materials you use affirm your students’ identities?

Community-based literacies

You may have noticed that communities are a big part of critical literacy – we understand that our environment and culture impact what we read and how we understand the world. Now think about the possible differences among three Iowa communities: a neighborhood in the middle of Des Moines, the rural community of New Hartford, and Coralville, a suburb of Iowa City:

You may not have thought about how living in a certain community might contribute to or take away from a child’s ability to learn to read. Dr. Susan Neuman (2001) did. She and her team investigated the differences between two neighborhoods regarding how much access to books and other reading materials children in those neighborhoods had. One middle-to-upper class neighborhood in Philadelphia had large bookstores, toy stores with educational materials, and well-resourced libraries. The other, a low-income neighborhood, had no bookstores or toy stores. There was a library, but it had fewer resources and served a larger number of patrons. In fact, the team found that even the signs on the businesses were harder to read, and there was less environmental printed word. Their findings showed that each child in the middle-class neighborhood had 13 books on average, while in the lower-class neighborhood there was one book per 300 children .

Dr. Neuman and her team (2019) recently revisited this question. This time, they looked at low-income neighborhoods – those where 60% or more of the people are living in poverty . They compared these to borderline neighborhoods – those with 20-40% in poverty – in three cities, Washington, D.C., Detroit, and Los Angeles. Again, they found significantly fewer books in the very low-income areas. The chart represents the preschool books available for sale in each neighborhood. Note that in the lower-income neighborhood of Washington D.C., there were no books for young children to be found at all!

Now watch this video from Campaign for Grade Level Reading. Access to books is one way that children can have new experiences, but it is not the only way!

What is the “summer slide,” and how does it contribute to the differences in children’s reading abilities?

The importance of being literate and how to get there

“Literacy is a bridge from misery to hope” – Kofi Annan, former United Nations Secretary-General.

Our economy is enhanced when citizens have higher literacy levels. Effective literacy skills open the doors to more educational and employment opportunities so that people can lift themselves out of poverty and chronic underemployment. In our increasingly complex and rapidly changing technological world, it is essential that individuals continuously expand their knowledge and learn new skills to keep up with the pace of change. The goal of our public school system in the United States is to “ensure that all students graduate from high school with the skills and knowledge necessary to succeed in college, career, and life, regardless of where they live.” This is the basis of the Common Core Standards, developed by the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) and the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center). These groups felt that education was too inconsistent across the different states, and today’s students are preparing to enter a world in which colleges and businesses are demanding more than ever before. To ensure that all students are ready for success after high school, the Common Core State Standards established clear universal guidelines for what every student should know and be able to do in math and English language arts from kindergarten through 12th grade: “The Common Core State Standards do not tell teachers how to teach, but they do help teachers figure out the knowledge and skills their students should have” (Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2012).

Explore the Core!

Go to iowacore.gov and click on Literacy Standards. Spend some time looking at the K-3 standards. Notice how consistent they are across the grade levels. Each has specific requirements within the categories:

- Reading Standards for Literature

- Reading Standards for Informational Text

- Reading Standards for Foundational Skills

- Writing Standards

- Speaking and Listening Standards

- Language Standards

Download the Iowa Core K-12 Literacy Manual . You will use it as a reference when you are creating lessons.

Next, explore the Subject Area pages and resources. What tools does the state provide to teachers to support their use of the Core?

Describe a resource you found on the website. How will you use this when you are a teacher?

Watch this video about the Iowa Literacy Core Standards:

- Literacy is typically defined as the ability to ingest, understand, and communicate information.

- Literacy has multiple definitions, each with a different point of focus.

- “New literacies,” or multiliteracies, are a combination of multiple ways of communicating and making meaning, including visual, audio, spatial, behavioral, and gestural communication.

- As online communication has become more prevalent, digital literacy has become more important for learners to engage with the wealth of information available online.

- Critical literacy develops learners’ critical thinking by asking them to use an analytic lens that detects power, privilege, and representation to understand different ways of looking at information.

- The Common Core State Standards were established to set clear, universal guidelines for what every student should know after completing high school.

Resources for teacher educators

- Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education Framework [PDF]

- Common Core State Standards

- Iowa Core Instructional Resources in Literacy

Gonzalez, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2006). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms . New York, NY: Routledge.

Lau, S. M. C. (2012). Reconceptualizing critical literacy teaching in ESL classrooms. The Reading Teacher, 65 , 325–329.

Literacy. (2018, March 19). Retrieved March 2, 2020, from https://en.unesco.org/themes/literacy

Neuman, S. B., & Celano, D. (2001). Access to print in low‐income and middle‐income communities: An ecological study of four neighborhoods. Reading Research Quarterly, 36 (1), 8-26.

Neuman, S. B., & Moland, N. (2019). Book deserts: The consequences of income segregation on children’s access to print. Urban education, 54 (1), 126-147.

New London Group (1996). A Pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66 (1), 60-92.

O’Brien, J. (2001). Children reading critically: A local history. In B. Comber & A. Simpson (Eds.), Negotiating critical literacies in classrooms (pp. 41–60). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ordoñez-Jasis, R., & Ortiz, R. W. (2006). Reading their worlds: Working with diverse families to enhance children’s early literacy development. Y C Young Children, 61 (1), 42.

Saha S. (2006). Improving literacy as a means to reducing health disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 21 (8):893-895. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00546.x

UNESCO. (2017). Literacy rates continue to rise from one generation to the next global literacy trends today. Retrieved from http://on.unesco.org/literacy-map.

Vasquez, V.M., Janks, H. & Comber, B. (2019). Critical Literacy as a Way of Being and Doing. Language Arts, 96 (5), 300-311.

Vlieghe, J. (2015). Traditional and digital literacy. The literacy hypothesis, technologies of reading and writing, and the ‘grammatized’ body. Ethics and Education, 10 (2), 209-226.

Zimmerman, E. B., Woolf, S. H., Blackburn, S. M., Kimmel, A. D., Barnes, A. J., & Bono, R. S. (2018). The case for considering education and health. Urban Education, 53 (6), 744-773.U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences.

U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), 2022 Reading Assessment.

Methods of Teaching Early Literacy Copyright © 2023 by Constance Beecher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

What you need to know about literacy

What is the global situation in relation to literacy.

Great progress has been made in literacy with most recent data (UNESCO Institute for Statistics) showing that more than 86 per cent of the world’s population know how to read and write compared to 68 per cent in 1979. Despite this, worldwide at least 763 million adults still cannot read and write, two thirds of them women, and 250 million children are failing to acquire basic literacy skills. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused the worst disruption to education in a century, 617 million children and teenagers had not reached minimum reading levels.

How does UNESCO define literacy?

Acquiring literacy is not a one-off act. Beyond its conventional concept as a set of reading, writing and counting skills, literacy is now understood as a means of identification, understanding, interpretation, creation, and communication in an increasingly digital, text-mediated, information-rich and fast-changing world. Literacy is a continuum of learning and proficiency in reading, writing and using numbers throughout life and is part of a larger set of skills, which include digital skills, media literacy, education for sustainable development and global citizenship as well as job-specific skills. Literacy skills themselves are expanding and evolving as people engage more and more with information and learning through digital technology.

What are the effects of literacy?

Literacy empowers and liberates people. Beyond its importance as part of the right to education, literacy improves lives by expanding capabilities which in turn reduces poverty, increases participation in the labour market and has positive effects on health and sustainable development. Women empowered by literacy have a positive ripple effect on all aspects of development. They have greater life choices for themselves and an immediate impact on the health and education of their families, and in particular, the education of girl children.

How does UNESCO work to promote literacy?

UNESCO works through its global network, field offices and institutes and with its Member States and partners to advance literacy in the framework of lifelong learning, and address the literacy target 4.6 in SDG4 and the Education 2030 Framework for Action . Its Strategy for Youth and Adult Literacy (2020-2025) pays special attention to the member countries of the Global Alliance for Literacy which targets 20 countries with an adult literacy rate below 50 per cent and the E9 countries, of which 17 are in Africa. The focus is on promoting literacy in formal and non-formal settings with four priority areas: strengthening national strategies and policy development on literacy; addressing the needs of disadvantaged groups, particularly women and girls; using digital technologies to expand and improve learning outcomes; and monitoring progress and assessing literacy skills. UNESCO also promotes adult learning and education through its Institute for Lifelong Learning , including the implementation of the 2015 Recommendation on Adult Learning and Education and its monitoring through the Global Report on Adult Learning and Education.

What is digital literacy and why is it important?

UNESCO defines digital literacy as the ability to access, manage, understand, integrate, communicate, evaluate and create information safely and appropriately through digital technologies for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship. It includes skills such as computer literacy, ICT literacy, information literacy and media literacy which aim to empower people, and in particular youth, to adopt a critical mindset when engaging with information and digital technologies, and to build their resilience in the face of disinformation, hate speech and violent extremism.

How is UNESCO helping advance girls' and women's literacy?

UNESCO’s Global Partnership for Women and Girls Education, launched in 2011, emphasizes quality education for girls and women at the secondary level and in the area of literacy; its Literacy Initiative for Empowerment (LIFE) project (2005–15) targeted women; and UNESCO’s international literacy prizes regularly highlight the life-changing power of meeting women’s and girls’ needs for literacy in specific contexts. Literacy acquisition often brings with it positive change in relation to harmful traditional practices, forms of marginalization and deprivation. Girls’ and women’s literacy seen as lifelong learning is integral to achieving the aims of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

How has youth and adult literacy been impacted in times of COVID-19?

Since the start of the pandemic, several surveys have been conducted but very little is still known about the effect on youth and adult literacy of massive disruptions to learning, growing inequalities and projected increases in school dropouts. To fill this gap UNESCO will conduct a global survey “Learning from the COVID-19 crisis to write the future: National policies and programmes for youth and adult literacy” collecting information from countries worldwide regarding the situation and policy and programme responses. Its results will help UNESCO, countries and other partners respond better to the recovery phase and advance progress towards achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 on education and its target 4.6 on youth and adult literacy. In addition, for International Literacy Day 2020, UNESCO prepared a background paper on the impact of the crisis on youth and adult literacy.

What is the purpose of the Literacy Prize and Literacy Day?

Every year since 1967, UNESCO celebrates International Literacy Day and rewards outstanding and innovative programmes that promote literacy through the International Literacy Prizes. Every year on 8 September UNESCO comes together for the annual celebration with Field Offices, institutes, NGOs, teachers, learners and partners to remind the world of the importance of literacy as a matter of dignity and human rights. The event emphasizes the power of literacy and creates awareness to advance the global agenda towards a more literate and sustainable society.

The International Literacy Prizes reward excellence and innovation in the field of literacy and, so far, over 506 projects and programmes undertaken by governments, non-governmental organizations and individuals around the world have been recognized. Following an annual call for submissions, an International Jury of experts appointed by UNESCO's Director-General recommends potential prizewinning programmes. Candidates are submitted by Member States or by international non-governmental organizations in official partnership with UNESCO.

Related items

- Lifelong education

Defining and Understanding Literacy

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Simply put, literacy is the ability to read and write in at least one language. So just about everyone in developed countries is literate in the basic sense. In her book "The Literacy Wars," Ilana Snyder argues that "there is no single, correct view of literacy that would be universally accepted. There are a number of competing definitions, and these definitions are continually changing and evolving." The following quotes raise several issues about literacy, its necessity, its power, and its evolution.

Observations on Literacy

- "Literacy is a human right, a tool of personal empowerment and a means for social and human development. Educational opportunities depend on literacy. Literacy is at the heart of basic education for all and essential for eradicating poverty, reducing child mortality, curbing population growth, achieving gender equality and ensuring sustainable development, peace, and democracy.", "Why Is Literacy Important?" UNESCO , 2010

- "The notion of basic literacy is used for the initial learning of reading and writing, which adults who have never been to school need to go through. The term functional literacy is kept for the level of reading and writing that adults are thought to need in a modern complex society. Use of the term underlines the idea that although people may have basic levels of literacy, they need a different level to operate in their day-to-day lives.", David Barton, "Literacy: An Introduction to the Ecology of Written Language ," 2006

- "To acquire literacy is more than to psychologically and mechanically dominate reading and writing techniques. It is to dominate those techniques in terms of consciousness; to understand what one reads and to write what one understands: It is to communicate graphically. Acquiring literacy does not involve memorizing sentences, words or syllables, lifeless objects unconnected to an existential universe, but rather an attitude of creation and re-creation, a self-transformation producing a stance of intervention in one's context.", Paulo Freire, "Education for Critical Consciousness," 1974

- "There is hardly an oral culture or a predominantly oral culture left in the world today that is not somehow aware of the vast complex of powers forever inaccessible without literacy.", Walter J. Ong, "Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word," 1982

Women and Literacy

Joan Acocella, in a New Yorker review of the book "The Woman Reader" by Belinda Jack, had this to say in 2012:

"In the history of women, there is probably no matter, apart from contraception, more important than literacy. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, access to the power required knowledge of the world. This could not be gained without reading and writing, skills that were granted to men long before they were to women. Deprived of them, women were condemned to stay home with the livestock or, if they were lucky, with the servants. (Alternatively, they may have been the servants.) Compared with men, they led mediocre lives. In thinking about wisdom, it helps to read about wisdom, about Solomon or Socrates or whomever. Likewise, goodness and happiness and love. To decide whether you have them or want to make the sacrifices necessary to get them, it is useful to read about them. Without such introspection, women seemed stupid; therefore, they were considered unfit for education; therefore, they weren’t given an education; therefore they seemed stupid."

A New Definition?

Barry Sanders, in "A Is for Ox: Violence, Electronic Media, and the Silencing of the Written Word" (1994), makes a case for a changing definition of literacy in the technological age.

"We need a radical redefinition of literacy, one that includes a recognition of the vital importance that morality plays in shaping literacy . We need a radical redefinition of what it means for society to have all the appearances of literacy and yet to abandon the book as its dominant metaphor. We must understand what happens when the computer replaces the book as the prime metaphor for visualizing the self." "It is important to remember that those who celebrate the intensities and discontinuities of postmodern electronic culture in print write from an advanced literacy. That literacy provides them the profound power of choosing their ideational repertoire. No such choice or power is available to the illiterate young person subjected to an endless stream of electronic images."

- Orality: Definition and Examples

- What Is a Literacy Test?

- The Power of Literacy Narratives

- 5 Ways to Improve Adult Literacy

- Definition and Meaning of Illiteracy

- Multiple Literacies: Definition, Types, and Classroom Strategies

- Adult Education

- How to Assess and Teach Reading Comprehension

- How to Understand a Difficult Reading Passage

- Thinking About Reading

- Teaching Developmental Reading Skills for Targeted Content Focuses

- 7 Active Reading Strategies for Students

- 'Fahrenheit 451' Overview

- Editor Definition

- 7 Independent Reading Activities to Increase Literacy

- Literature Definitions: What Makes a Book a Classic?

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Historically, literacy refers to the act of reading and writing--the act of symbolic thinking. Yet, over time, as humanity has developed new tools for expression (e.g., the printing press, the internet, social media, or artificial intelligence), humanity has developed a more nuanced understanding of what it means to read and write. This article defines literacy, summarizes different types of literacies, and explores the effects of literacy on human consciousness and culture.

Literacy Definition

Literacy refers to, or functions as,

- the ability to read and write in home, school, workplace, and public settings

- an amalgam of competencies, skills, knowledge, and dispositions related to acts of interpretation , communication , or competency

- a commodity

- empowers people to develop their personal, social, and economic power

- empowers literate cultures to develop new ideas and methods, including science, social science, humanities, engineering, and arts

- a measure of educational attainment and audience awareness .

Related Concepts: Academic Writing Prose Style ; Critical Literacy ; Information Literacy ; Intellectual Openness ; Professional Writing Prose Style ; Rhetoric & Apparatus Theory ; Semiotics: Sign, Signifier, Signified ; Writing Process

What is Literacy? – Guide to Literacy in 2023