Stock Photo - African american boy doing homework with his dad. A handsome black man helping his son with school work at home. It's important to learn and get an education. A parent and child working on a project

African american boy doing homework with his dad. A handsome black man helping his son with school work at home. It's important to learn and get an education. A parent and child working on a project - Stock Photo

Stock Photo Keywords:

man handsome school work working learn son homework education project parent child dad boy helping two father family

(See example) After purchase you can also find it on your purchase/redownload page ">How do you plan to use this image?

- Extended License info See prices below More than 499,999 impressions

- Standard License info See prices below Websites, Magazines, News, Books, Flyers, Brochures, Posters, etc

- 99% Buy-Out License info See prices below One-time 10 year unlimited world wide buy-out

- Late License info See prices below Got your Image Illegally? Get a license now

- Sensitive License info Alcohol, sexual context, etc

Choose Size and Download

Series: Days With My Family (26)

- AI Generator

5,946 Black Boy Doing Homework Stock Photos & High-Res Pictures

Browse 5,946 black boy doing homework photos and images available, or start a new search to explore more photos and images..

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Rise of Black Homeschooling

By Casey Parks

When Victoria Bradley was in fifth grade, she started asking her mother, Bernita, to homeschool her. Bernita wasn’t sure where the idea came from—they never saw homeschooling on TV. But something always seemed to be going wrong at school for Victoria. In second grade, a teacher lost track of her during parent pickup, and she wandered off school grounds. Bernita went to see the principal, intent on getting the teacher fired. The principal asked if she would consider taking an AmeriCorps position at the school. Bernita cut back her hours at the hair salon she owned and started doing community outreach, assisting teachers and hosting parent meetings.

In 2011, Bernita moved her family—which also included her older son, Carlos—to Detroit ’s East English neighborhood, where she bought a three-story, yellow brick house for twelve thousand dollars. Victoria, then in fourth grade, transferred to Brenda Scott Academy, where two girls began bullying her. One wrote “I’m fat” in black pen on the back of Victoria’s shirt. On another occasion, one of the girls spit at Victoria. She screamed at them, and was suspended. (That year, administrators suspended three hundred and forty Black students, or forty-two per cent of the school’s Black population, and another sixteen Black girls were arrested there.)

Victoria moved to a top-rated charter school, where she lasted only a few months—she said that an administrator picked on certain Black students. By fifth grade, Victoria had attended five schools, and she was tired of being the new kid. She brought up homeschooling when she was reprimanded for having blue braids, and again in eighth grade, after some boys dared each other to try picking her up as she sat at her desk. Homeschooling, she said, would allow her to learn at her own pace, without anyone making fun of her. Bernita was sympathetic, but she told Victoria that she couldn’t teach her. She was a single mom, and she’d never completed her college degree.

For high school, Victoria enrolled in a majority-white charter school. Before the coronavirus pandemic shuttered Detroit’s school system, which serves about fifty-three thousand children, she had failed chemistry and barely passed algebra. Soon after school went remote, in March, 2020, Victoria asked Bernita if she could drop out and take a job doing nails.

During the first months of lockdown, Bernita, who works as an educational consultant, spent hours each day talking to other parents of students in the Detroit system on Zoom and Facebook. One mother told her that she had shut herself in the bathroom to cry after overhearing teachers berate her children on Microsoft Teams. Others told Bernita they’d only just discovered that their kids had been performing below grade level. (Before the pandemic, six per cent of Detroit’s fourth graders met proficiency benchmarks in math, and seven per cent in reading, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress.)

Early one evening last July, before Victoria’s senior year, Bernita and Victoria pulled into their driveway and found that a container of dish soap they’d bought at Sam’s Club had spilled in the trunk. While Bernita bailed out the soap using a three-ring binder and some old rags, Victoria looked down the cracked driveway and pointed at a swarm of fireflies. “What makes them glow?” she asked.

Bernita watched Victoria chase the fireflies around the yard for a few minutes. This, she thought, was what a Black kid’s life should feel like—happy and unencumbered. She told Victoria to find a Mason jar. They ran through the grass until Victoria had trapped a single glowing insect. Afterward, they sat on their stoop, researching the specimen on Victoria’s phone. They learned that the bugs belong to the family Lampyridae, and that a bioluminescent enzyme makes them glow.

As Victoria scrolled, Bernita laughed. “You do know this is homeschooling, right?” she asked.

Victoria looked up from her phone. The fireflies lit up around them. “Really?” she asked.

“Yep,” Bernita said. “This is homeschooling. This is science. We about to do this for real.”

Black families have only recently turned to homeschooling in significant numbers. The Census Bureau found that, by October, 2020, the nationwide proportion of homeschoolers—parents who had withdrawn their children from public or private schools and taken full control of their education—had risen to more than eleven per cent, from five per cent at the start of the pandemic . For Black families, the growth has been sharper. Around three per cent of Black students were homeschooled before the pandemic; by October, the number had risen to sixteen per cent.

Few researchers have studied Black homeschoolers, but in 2009 Cheryl Fields-Smith, an associate professor at the University of Georgia’s Mary Frances Early College of Education, published a study of two dozen such families in and around Atlanta. Some parents were middle class or wealthy, and wanted more challenging curricula for their children. Others hadn’t attended college and earned less than fifteen thousand dollars a year; one family lived in a housing project.

Most of the parents told Fields-Smith that the decision had been wrenching. Winning access to public education was one of the central victories of the civil-rights movement. Several parents had relatives who saw homeschooling as “a slap in the face” to the legacy of Brown v. Board of Education. Others worried about harming their neighbors’ children, because public schools rely on per-pupil funding from state governments. (In 2020, around seventy per cent of Detroit public-school revenues came from per-student allocations by the state.)

Still, the parents said that they felt as if they’d had no choice, with eighty per cent citing pervasive racism and inequities. Even in the wealthy families, parents said that their kids were frequently punished or seen as troublemakers. In some cases, students had been inappropriately recommended for special-education classes or medication; other students were bullied. In a study conducted in 2010 by professors from Temple University and Montgomery County Community College, homeschooling parents said that they thought Black Americans had been tricked into fighting for integration. “Somebody put in our heads that being around your own kind was the worst thing in the world. How you need to be in better neighborhoods, in neighborhoods where people don’t want you, in schools where people don’t want to teach you,” a mother in Virginia, who was homeschooling two children, said.

Bernita and Victoria first encountered a Black homeschooling family in 2015, when Victoria was in seventh grade and attending an after-school music class with a girl named Zwena Gray. Zwena’s mother, Kija, had worked for many years as a substitute teacher in the University Prep School charter system. Most schools, in her view, prioritize whiteness—the kids are taught about white politicians and white inventors, and teachers and Black children are pushed toward compliance rather than creativity. Kija’s son, Kafele, was frequently bullied. When he was in eighth grade, administrators at the charter school he was attending threatened to suspend him for not tucking in his shirt. Kija decided to homeschool him, and later Zwena, who was then in fifth grade. The children enrolled in online courses; Kija spent less time substitute teaching, and her husband, who works for the Detroit Health Department, also helped. Kafele returned to the charter school in eleventh grade, but Zwena never went back to school.

When we talked in her dining room, Kija was baking cinnamon pound cakes to sell. As she described her journey from charter-school teacher to homeschool enthusiast, she drew a Biblical parallel: “Satan was the closest thing to God, and he saw this shit for what it was, and he was, like, ‘Oh, hell no.’ He started to question things, and that’s what made him cast out, because he didn’t have blind faith—he had critical faith.”

Bernita was astonished by what Kija had achieved with her children. Zwena had built robots, written code for Web sites, and designed her own clothes. But Kija had a bachelor’s degree and a background in teaching. Bernita still couldn’t see homeschooling as an option for Victoria.

In early 2020, an online acquaintance of Bernita’s, Keri Rodrigues, a former labor organizer in Massachusetts and the president of a new organization called the National Parents Union, persuaded her to begin hosting a weekly forum for parents on Facebook Live. At the beginning of June, Bernita invited Kija on as a guest. It was a week after the police officer Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd in Minneapolis; thousands of people were protesting in downtown Detroit. The parents who spoke in the Facebook forum connected the uprising for racial justice with their experiences in the educational system. One mother said that she had tried many public and private schools; at all of them, the front office was filled with Black boys awaiting discipline.

Tesha Jordan, a single mother who works for Head Start, said that she’d been urged to transfer her son out of his middle school after his behavioral issues had scared a teacher. Jordan’s son has a learning disability, and she worried that if she homeschooled him he would lose out—the state gave his middle school money for a social worker to help him with his homework twice a week. “I’m not a teacher,” Jordan said. “I’m just a mother.”

Kija, watching from her living room, unmuted herself. “When I heard you say they had a behavioral problem—or you were told that—the thing that came to mind for me was, all Black people have a behavioral problem. It’s called trauma,” she said. “And when you said, ‘I’m not a teacher, I’m a mother’—those two things are synonymous.”

The modern homeschooling movement in America was ignited in the nineteen-sixties, after Supreme Court decisions in 1962 and 1963 prohibited school prayer and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed racial segregation in public institutions. Although homeschooling attracted some left-leaning hippies during the sixties and seventies, by the nineteen-eighties its most vocal and influential supporters were white Christian conservatives, according to Heath Brown, an associate professor of public policy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and the author of the recent book “Homeschooling the Right: How Conservative Education Activism Erodes the State.”

Most of the earliest homeschooling textbooks were written from a Christian perspective, and some were racist. Bob Jones University, the private South Carolina college that refused to admit Black students until 1971, began issuing homeschooling textbooks through its press later that decade. “United States History for Christian Schools,” first published in 1991, stated that most slaveholders treated enslaved people well, and that slavery “is an excellent example of the far-reaching consequences of sin. The sin in this case was greed—greed on the part of African tribal leaders.”

Arlin and Rebekah Horton, who met at Bob Jones University, went on to found what became Abeka, a Christian publisher that produces some of the country’s most popular homeschooling materials. Abeka’s “America: Land I Love,” for eighth graders, first published in 1996 and now in its third edition, argued that slavery allowed Black people to find Jesus. Abeka’s eleventh-grade textbook “United States History: Heritage of Freedom,” first published in 1983 and now in its fourth edition, claimed that the Ku Klux Klan only occasionally resorted to violence. A 2018 investigation by the Orlando Sentinel found that Abeka was still producing textbooks stating that “the slave who knew Christ had more freedom than a free person who did not know the Savior.”

Early supporters of homeschooling wanted as little government intervention as possible and advocated against legislative proposals that would have sent money their way, Brown told me. “It was a bargain they were unwilling to take,” he said. “In exchange for small amounts of funding, they would be subject to the things they fear most, which was having to adhere to a set of standardized educational schooling practices, on everything from teacher certification to testing to curricular choice.”

In 1983, a group of white evangelical lawyers formed the Home School Legal Defense Association, to represent homeschooling parents who’d been arrested for not sending their children to school. When officers arrested two farmers in Michigan who’d been educating their children at home without a license, the H.S.L.D.A. spent nearly a decade fighting their case. In 1993, the state’s Supreme Court ruled that homeschooling parents in Michigan did not need to be certified. (Michael Farris, the founding president of the H.S.L.D.A. and its board chairman, is now head of the conservative Christian nonprofit Alliance Defending Freedom, which in recent years has pushed for a series of anti-gay and anti-trans bills.)

The H.S.L.D.A. offers grants directly to coöperatives formed by homeschooling parents; after the number of homeschoolers spiked during the pandemic, it doubled its grant dollars for this year, to $1.3 million. As the number of Black and Latino homeschooling families has grown, the group has attempted to diversify its membership and staff. All but one of its lawyers are white, but it recently hired several Black and Latino consultants. LaNissir James, who has seven children, ranging in age from five to twenty-three, and who is based in Maryland but “roadschools” across multiple states in her R.V., started working as a high-school educational consultant for the H.S.L.D.A. in 2019. Families “first need to understand the law,” she said, because homeschooling regulations vary widely from state to state. Then James interviews parents to assess their children’s academic needs. “Are Mom and Dad working? Is Mom home? Do they want to be online? You find their strengths and weaknesses so that you can find a curriculum that matches that family.”

For Black families like James’s, the ability to improvise a curriculum is a major reason to try homeschooling. “We are not seeing ourselves in textbooks,” she said. “I love traditional American history, but I like to take my kids to the Museum of African American History and Culture and say, O.K., here’s what was going on with Black people in 1800.” There are now hundreds of curricula to choose from, available on free or inexpensive Web sites such as Khan Academy and Outschool. Last year, one of the most popular offerings on Outschool was a course called Black History from a Decolonized Perspective, taught by Iman Alleyne, a former schoolteacher in Fort Lauderdale, who turned to homeschooling after her elementary-age son told her that school made him want to die.

James said that some of her Black clients need to know that homeschooling is something other Black families do. “That’s a normal feeling,” she told me. “And the answer is yes. There is joy for Black homeschoolers who find out about other Black homeschoolers.”

In August, 2020, Bernita applied for and won a twenty-five-thousand-dollar grant from Keri Rodrigues’s group, the National Parents Union, to fund a homeschooling collective called Engaged Detroit. She hired Kija and two other Black homeschooling mothers, at thirty-five dollars an hour, to coach a group of twelve parents, and used the remaining money to buy software, laptops, and other supplies.

In accepting the grant, Bernita became part of a decades-long political debate. The National Parents Union paid for the grant with money from Vela Education Fund, which is backed by the Walton Family Foundation and the Charles Koch Institute. These groups advocate “school choice”—rerouting money and families away from traditional public schools through such means as charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately managed, and vouchers, which allow public-education dollars to be put toward private-school tuition.

Sarah Reckhow, an associate professor of political science at Michigan State University and the author of “Follow the Money: How Foundation Dollars Change Public School Politics,” told me that the Waltons “have been consistently a key funder of the charter-school movement.” Since 1997, the Walton foundation has spent more than four hundred million dollars to create and expand charter schools nationwide. In 2016, it announced plans to spend an additional billion dollars on charters.

School choice is an especially divisive subject in Michigan, where some of the country’s first charter schools were established, in 1994. Betsy DeVos , of Michigan’s billionaire Prince family, has invested millions, through donations and lobbying, to expand charters across the state. In 1999 and 2000, DeVos and her family backed an unsuccessful campaign, called Kids First! Yes!, to amend Michigan law to allow vouchers. In 2013, the Walton foundation doubled the budget of another DeVos project, the pro-voucher group Alliance for School Choice, when it announced a donation of six million dollars to send lower-income children to private schools. Three years later, DeVos published an op-ed in the Detroit News calling for the state to “retire” Detroit’s public-school system: “Rather than create a new traditional school district to replace the failed D.P.S.”—Detroit Public Schools—“we should liberate all students from this woefully under-performing district model and provide in its place a system of schools where performance and competition create high-quality opportunities for kids.” DeVos’s first budget proposal as Secretary of Education under President Trump, in 2017, would have cut nine billion dollars from federal education funding while adding more than a billion dollars for school-choice programs.

Advocates of school choice say that it gives low-income parents access to institutions that can better serve their children. Critics say that it lures highly motivated Black families away from traditional public schools and further hobbles underfunded districts. Presidents Clinton and Obama supported charters, but Democrats have largely cooled on them, and progressives such as Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have proposed curbing their growth. Michigan’s charters, most of which operate as for-profit companies, have consistently performed worse than the state’s traditional public schools. Yet parents continue to choose charters, which receive a large chunk of the more than eight thousand dollars per student that the state would otherwise send to non-charters, but aren’t subject to the same degree of public oversight. About half of Detroit’s students are now enrolled in charters, one of the highest proportions of any U.S. city.

The Walton foundation set up the National Parents Union in January, 2020, with Rodrigues as the founding president. Rodrigues’s oldest son, who has autism and A.D.H.D., was suspended thirty-six times in kindergarten alone; sometimes he was sent to a sensory-deprivation room that Rodrigues thought resembled a cinder-block cell. Eventually, a school representative suggested a charter school. “I didn’t know what a charter school was,” Rodrigues said. “I didn’t know I had any options. I just thought I had to send him to the closest school. I didn’t know there were fights like this in education. All I knew was ‘Oh, my god, are you kidding me—why are you doing this to my kid?’ ”

The National Parents Union was less than three months old when the pandemic closed schools. As well-off families set up private learning pods, Vela Education Fund gave Rodrigues seven hundred thousand dollars to help people with fewer resources, like Bernita, create their own. “There was an article in the New York Times about fancy white people in upstate New York creating these ‘pandemic pods,’ ” Rodrigues said. “But that’s how poor Black and brown folks survive in America—we resource-share. We don’t call them ‘pandemic pods,’ because that’s a bougie new term. For us, we called it ‘going to Abuelita’s house,’ because she watched all the cousins in the family after school, and that’s where you learned a host of skills outside of the normal school setting.”

Last summer, the nonprofit news organization Chalkbeat, which receives Walton funding, co-sponsored a virtual town hall on reopening Michigan’s public schools. Detroit’s superintendent, Nikolai P. Vitti, said that expanding to “non-traditional” options, such as learning pods, would hurt many of the city’s children. He warned that homeschooling, like charter schools, would undermine public education and cost teachers their jobs. Legislators were already drafting bills, he said, to take money away from schools so that children could continue learning in pods after campuses reopened.

“I don’t judge any parent for using the socioeconomic means that they have to create what they believe is the best educational opportunity for their child,” Vitti said. “We all do that, in our way, as parents. But that is the purpose of traditional public education, to try to be the equalizer, to try to create that equal opportunity.”

Bernita had logged on to the discussion from her kitchen. “Parents are not deciding to take their children out because of COVID ,” she told Vitti. “Parents are doing pods because education has failed children in this city forever.”

I asked Kija if it bothered her to accept money from the conservative-libertarian Koch family, who have spent vast sums of their fortune advocating for lower taxes, deep cuts to social services, and looser environmental regulations. “I guess the bigger question is, why don’t we have enough resources so that we don’t have to get money from them? It bothers me, yes—but why do they have so much money that they get to fund all of our shit?” she asked. “I shouldn’t have to get resources from the Kochs.”

Kija and Bernita describe themselves as Democrats. Bernita said that, in another era, she “would be a Black Panther with white friends.” She said that she was “at peace” with her decision to take money from the Koch family, because they fund several of the charter schools that Victoria attended, through their Michigan-based building-supply company Guardian Industries. She is not a “poster child” for her conservative backers, she added—the Koch family has no control over what or how she teaches. In a video about Engaged Detroit produced by Vela Education Fund, Bernita states, “If school won’t reinvent education, we have to reinvent it ourselves, and our goal at Engaged Detroit is to make sure families have the tools so that choice is in their hands.”

Vela Education Fund offered Bernita one year of funding, and in April she accepted another twenty-five-thousand-dollar grant, from Guardian Industries, to sustain her group through the next school year. Rodrigues imagines a scenario in which the per-pupil funding that public-school districts normally receive goes straight to a homeschooling parent. “Instead,” she said, “you have systems that are addicted to that money.”

Celine Coggins, the executive director of Grantmakers for Education, a collective of more than three hundred philanthropic organizations, including the Walton Family Foundation, says it’s not clear yet whether funders will continue to invest in homeschooling after the pandemic. Most are in “listening mode,” she said. Andre Perry, an education-policy expert at the centrist Brookings Institution, suspects that conservative-libertarian philanthropists will not prop up homeschooling as they have charters and vouchers, “but they will use this wedge issue to hurt public schools,” he said.

Perry was once the C.E.O. of the Capital One New Beginnings Charter School Network, which launched in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, but he grew skeptical of the school-choice movement. Its funders tend to put their wealth toward alternatives to the public-school system, Perry told me, rather than lobbying state governments to implement more equitable funding models for public schools or to address the over-representation of Black children in special education. “Because of the pandemic, you’ve had organizations saying, Hey, this is an opportunity to again go after public schools,” Perry said. The Vela-funded homeschooling collectives don’t address root causes of educational disparities, he continued: “When people only focus on the escape hatch, it reveals they’re not interested in improving public education.”

Perry went on, “Slapping ‘Parents Union’ on something while you’re constantly trying to underfund public education—that’s not the kind of trade-off that suggests you’re interested in empowering Black people. It’s more of a sign that you’re trying to advance a conservative agenda against public systems.”

Six months into the pandemic, a consensus had emerged that many children, in all kinds of learning environments, were depressed, disengaged, and lonely in the Zoom simulacrum of school. “It’s Time to Admit It: Remote Education Is a Failure,” a headline stated in the Washington Post . “Remote Learning Is a Bad Joke,” The Atlantic declared. For some homeschoolers who rely heavily on online curricula, an all-screens, alone-in-a-room version of school can have a flattening effect even outside of a global health crisis. Kafele Gray, Kija’s son, who is now twenty-one and studying music business at Durham College, in Ontario, liked online homeschooling because it freed him from bullying. After two years, though, he was failing his classes and procrastinating, with assignments piling up. “It got kind of stressful,” he said. “You have to teach yourself and be on yourself.” He especially struggled with math. “When I’m in school, I’m better at math, because I have the teacher there to explain it to me—I’m seeing it broken down. When I was online, I would get it wrong, but I wouldn’t know why.” Still, when Kafele returned to his charter school, in eleventh grade, he’d learned to push himself to figure things out on his own. “School was less challenging” than it had been two years earlier, he told me. “I started getting A’s and B’s again.”

When the fall semester started, Bernita and Victoria tried to replicate the course load Victoria would have undertaken in a normal year. Bernita searched for online chemistry and trigonometry classes, and Victoria decided to take dance at the charter high school she’d attended before the pandemic. Bernita wanted the Engaged Detroit families to learn about Black history, so she signed them up for a six-week virtual course with the Detroit historian Jamon Jordan. Victoria bought pink notebooks and pens and a chalkboard for writing out the weekly schedule, and Bernita set up a desk for her daughter in the den. Though Bernita spent many hours on Zoom for her consulting work, the family ate lunch together most days.

As the semester continued, Victoria faded. She stayed up until seven in the morning and slept until two every afternoon, and she stopped doing chemistry. In October, Bernita told her that she couldn’t go on a planned post-pandemic trip to Los Angeles. Later that week, during her weekly coaching session with Kija, Bernita bragged about disciplining Victoria. Kija asked her to reconsider: teen-agers like sleeping in, and homeschooling allows kids to follow their natural rhythms. Besides, Kija said, Black kids are disciplined more than enough. Rather than punish Victoria, Kija suggested, Bernita should ask her daughter what she wanted to study.

The advice worked: Victoria replaced chemistry with a forensic-science class that met the state science requirements for graduation. She pored over lessons about evidence and crime scenes for hours at a time. By spring, she was waking up early to study for the core classes she needed to pass. One cold, sunny Wednesday, wearing a sweatshirt that read “Look Momma I’m Soaring,” Victoria sat down to puzzle out the trigonometry lessons that had always confused her. She emptied a pail of highlighters onto the table. At her high school, teachers hadn’t let her write in different colors, and she couldn’t make sense of her monochromatic notes. She opened a Khan Academy lesson on side ratios, and as the instructor explained the formulas for finding cosine and tangent Victoria drew triangles, highlighting each side with a different color.

The lesson included a nine-minute video and several practice questions. Every time Victoria attempted to find the cosine of the specified angle, she got the wrong answer. In a regular class, she would have pretended to understand. At home, she paused the video, rewound it, and flipped back through her notes. Eventually, she realized that she didn’t know which side was the hypotenuse. She Googled the word.

“The longest side of a right triangle,” she read. “Oh.”

She tried the formula for sine—opposite over hypotenuse—and this time a green check mark of victory flashed on her screen. Victoria solved for the angle’s tangent, and when she got it right she smiled. “O.K., I’m smart,” she said.

The parents of Engaged Detroit meet on Zoom every other Monday night. One evening in mid-March, Bernita set her laptop on the kitchen table next to a plate of broccoli and mashed potatoes. A dozen squares popped up on her screen, showing kitchens and living rooms from across the city. The parents updated one another on their children’s progress. Two preteens had started a jewelry-making business. An elementary-age boy with a stutter was relieved to be learning at home with his mom. Victoria watched for a minute, then went upstairs to feed her guinea pig, Giselle.

A mother, Jeanetta Riley, recounted how, at the beginning of lockdown, she had discovered that her daughter, Skye, a freshman in high school, was performing two grades behind in math. After she joined Bernita’s group, she found a tutor, and now, using Khan Academy, Skye had caught up to her grade level.

Link copied

Like Bernita, Jeanetta had thought of homeschooling as something only white people did. “A lot of Black people are struggling,” she told me. They don’t have the resources to stay at home all day teaching. Before the pandemic, Jeanetta worked long hours in customer service at the Fiat Chrysler plant. The company laid her off in March, 2020, and she isn’t sure when she’ll return to work. Skye is old enough to stay home alone, though, and Jeanetta plans to continue homeschooling after the pandemic, a decision some of her family members do not support. One relative berated her at a party for thinking she could take charge of something others go to graduate school to master. But Jeanetta was enjoying her weekly coaching sessions with Kija, and Skye seemed happier.

“I see such growth in her,” Jeanetta said. “She’s always painting stuff and bringing it to me. If that builds up her confidence, then I’m going for it. We didn’t even know she could paint. We didn’t know so much stuff about her. How is this my child, and I didn’t know?”

The day after the Engaged Detroit meeting, Victoria logged on to a dance class she was taking at the charter high school. Her teacher also joined from home, where she demonstrated the day’s lesson under a framed poster of the Beatles. She was a white woman who often played white music in class, Victoria said—that Tuesday, she streamed an Adrianne Lenker song as the students stretched. Victoria preferred R. & B., but she felt close to her teacher, who often e-mailed her to check in. Other instructors had disappeared early in the pandemic.

For the class’s final project, the teacher had encouraged the students to do something personal. Some choreographed a dance to music or to a poem. Victoria had written an original poem about being sexually abused as a child. Part of it read:

trauma can cause memory loss i physically remembered but consciously lost you’re so shaken up thrown around and tossed it’s up to you to ration the cost are you going to know who you are or cause family loss and you ask god to bring clarity on what you saw is this what defined who you are

Near the end of that day’s session, the teacher asked Victoria to stay online after class. When the other students had logged off, she told Victoria that she was worried about her poem. “I don’t want to censor anything,” the teacher said. “I just don’t know from a school standpoint that we can share.” The performances would be public, she said, for a “family audience.” She asked Victoria if she could revise the poem. “Some of the lines are very, very vulgar,” the teacher told her. (She was evidently referring to a stark couplet that switched the identity of “you” to disorienting effect: “you touched me in a way i never knew was true / before you could make anyone else hard he got hard off of you.”) Victoria slumped a little in her chair, but she tried to keep smiling. “O.K.,” she said.

A few nights later, Victoria opened an acceptance letter from Wayne State University. She’d won enough scholarship money to cover four years of tuition. With Pell Grant assistance, the amount came to more than thirteen thousand dollars a year. “That’s crazy,” she whispered to herself. She carried the letter around the house the next morning; she paused her trigonometry lesson to reread it. On her lunch break, buzzing with triumph, Victoria called her dance teacher on Microsoft Teams. She asked if, instead of revising her poem, she could add a trigger warning. The teacher said again that parts of the poem were “vulgar,” then laughed—a high-pitched giggle. If Victoria wanted to perform it, the teacher would need to consult with the school’s social worker: “I feel like there’s a fine line there, and I don’t know what’s acceptable for our audience.”

Victoria told her that she understood. She smiled, big and inviting, and she thanked her teacher for her time. “I appreciate it that you’re being understanding, that we’re having a good conversation about this,” the teacher said. “Other people would get into this intense thing.”

Bernita walked by and asked if she could speak to the teacher. Embarrassed, Victoria quickly closed her laptop.

“You just hung up on her,” Bernita said. “You know what I’m going to do is e-mail her, right?”

“Mom,” Victoria said firmly. Bernita stared back. Victoria bent over onto the table and buried her face in her arms. “She’s scared that [the teacher] is going to start acting funny with her,” Bernita told me. “That’s what always happens when she addresses something. The teacher turns around and starts feeling some kind of way about her, so she don’t want to address that, because she’s, like, ‘Just let me finish school.’ ”

She turned back to Victoria, who was sobbing.

“Ain’t that how you feeling?”

Victoria sat up to blow her nose, but cried harder. She nodded.

“People don’t know the damage they do to kids,” Bernita said. “She’s somewhere now thinking, ‘Oh, that went well.’ Baby, I’m going to e-mail her, O.K.?”

Victoria’s tears dropped onto her acceptance letter, soaking it.

Bernita suggested that she put her emotions into something creative, so Victoria collected herself and went upstairs to her room, returning with green and yellow ribbons and a pair of white Nike Air Force Ones. She wouldn’t have a normal high-school graduation. She wasn’t even sure what her high-school diploma would say. “Homeschool Academy”? But she wanted to celebrate, so she’d started planning the outfit she’d wear when the semester ended. Wayne State’s colors are green and gold.

For years, Victoria told people that she didn’t plan to go to college, because she feared no college would accept her. Now, the damp acceptance letter underneath her laptop, she wrapped a ribbon around the shoe and did what she’d done every year for the past twelve: she told herself that what came next would be better, and that, eventually, she’d find her place. ♦

An earlier version of this article misspelled Jamon Jordan’s name.

New Yorker Favorites

- The day the dinosaurs died .

- What if you could do it all over ?

- A suspense novelist leaves a trail of deceptions .

- The art of dying .

- Can reading make you happier ?

- A simple guide to tote-bag etiquette .

- Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Eric Lach

By Adam Iscoe

By Ronan Farrow

By Andrew Marantz

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

America Reckons With Racial Injustice

For some black students, remote learning has offered a chance to thrive.

Elizabeth Miller

Back when school was in person, Josh Secrett was always tired.

"I used to come home and just lay down and go to sleep for like hours," the eighth-grader says. "Wake up for dinner, go to bed."

Josh's mom, Sharnissa Secrett, says teachers at his Portland, Ore., school would sometimes discipline Josh for small things, like talking when he wasn't supposed to. Those interactions would hang over him the rest of the day.

"You look in my baby's eyes, when he used to come home, he was tired...mentally tired," she says.

But ever since his school went all-virtual, Josh has been doing much better.

His mom says there are fewer distractions, he can work independently and it's been easier for him to focus.

"It's like almost the noise is shut out and we can just get to the work."

Middle school is tough for just about everyone, but for Black students like Josh, school can be even harder. That's because, in addition to learning algebra and coping with social awkwardness, they're often navigating an educational system that historically hasn't supported them.

In Texas, students have been assigned history textbooks that downplay slavery and avoid talking about Jim Crow . In Massachusetts, Black girls have been reprimanded for violating dress codes that ban hair extensions . And across the country, according to federal data, Black students are more likely than white classmates to be disciplined at school .

Disparities Persist In School Discipline, Says Government Watchdog

When Black Hair Violates The Dress Code

In Oregon, where Josh lives, Black students have lower graduation rates. They're also less likely to be identified as "talented and gifted."

All that can take a toll on kids. But for some students like Josh, remote learning during the pandemic has offered an escape.

Of course, that hasn't been every student's experience. Between mental health struggles , limited Internet access and reduced child care options, distance learning isn't working for a lot of families. Research shows students with disabilities, those experiencing poverty and Black and Latinx students are among those especially at risk of falling behind.

Still, for Josh and kids like him, learning from home has given them a chance to thrive.

"Always on alert ... always deflecting"

At school, Josh learns from predominantly white teachers in classrooms full of predominantly nonwhite students. That demographic disparity is not exclusive to Portland . National data show the U.S. public school teacher population is overwhelmingly white, while more than half of the students those teachers interact with are nonwhite. And whether it's explicit or implicit, many teachers bring some kind of bias into the classroom.

Valerie Adams-Bass is a developmental psychologist at the University of Virginia who studies Black youth and media stereotypes. She says often, in the media, Black students are portrayed as being uninterested in education, and Black boys are portrayed as scary or intimidating.

"If that's what the teachers and administrators or their peers see, then oftentimes that is what they're responding to when they're engaging with Black students in reality."

Adams-Bass says it's no surprise some Black students are doing better at home than they were at school. School can take a lot out of them.

"There is emotional energy and a cognitive energy that goes along with navigating the spaces where you don't feel welcome or comfortable. You're always on alert, you're always on, you're always deflecting, so you would be exhausted at the end of the day on top of growing," she says.

"I'm more energized. I want to do more things."

Before the pandemic, Josh says he wasn't connecting with his teachers. Instead, he put his energy into showing them he wasn't a "bad" kid.

"I didn't want the teachers to think I was the problem in the classroom, or what they thought of my skin color," he says. "I just wanted to show them I was better."

"Even that is problematic," his mom interjects. She and Josh's father often talk to him about growing up as a Black boy, and how to advocate for himself if he feels singled out by teachers or peers.

"You're not the model," she tells him. "They have to do better, to make you feel like you are seen and heard."

In the past, when that hasn't happened, Secrett says she would step in on her son's behalf.

Parenting: Difficult Conversations

Talking race with young children.

"The nagging, the 'you're not doing well' — that damages our babies' self-esteem, especially our Black babies' and our kids of color."

Now, at home, both Josh and his mom say he's more comfortable. They say Josh and his teachers have been building relationships based around his classwork and academic achievements.

"I can interact with the teachers as I need." Secrett says. "He interacts with the teachers as they need."

Secrett says she's also seeing her son's confidence go up, and she's better able to monitor how he's feeling. "I know what's going on with him. I can maintain the emotional."

She does worry about the mental health impacts of Josh learning from home, but for now she's decided the benefits outweigh the costs.

Josh can take breaks and relax, and he can spend more time with his family, including his older brothers. He's not exhausted at the end of the school day anymore.

"I'm more energized," Josh says. "I want to do more things."

How schools can help

The pandemic won't go on forever. Soon enough, Josh and his peers will be back in a physical classroom. And there are a few things schools can do to make learning in-person a better experience for all students, Adams-Bass says.

Schools could hire more teachers of color, and offer a curriculum that reflects students' culture and history.

"[Students] should see teachers, they should see administrators that look like them. And certainly, the curriculum should include them beyond one month of celebration," she explains.

Teaching Students A New Black History

Adams-Bass also recommends training current teachers to understand their own biases. She says students need caring relationships with their teachers, and "teachers that demonstrate and understand a knowledge and sensitivity to who the students are as individuals, as well as part of the classroom."

She also suggests forming groups where marginalized students can share their stories with each other.

"Affinity spaces allow them to talk about common experiences, to develop solutions, to support one another, and also to figure out ... how to navigate the larger space where they're learning."

Of course, not all of these things can happen overnight.

"Our staff is our staff," says Michael Contreras, Josh's principal at Ron Russell Middle School.

"We admit that we're a bunch of white teachers teaching mostly nonwhite kids."

Contreras says it's not easy to quickly diversify a school's teaching staff. But he's committed to supporting teachers "in teaching kids who don't necessarily have the same life experience as them." He says trust and strong relationships are important for teachers and students, no matter their differences.

Still, any changes at Ron Russell will come too late for Josh, who is heading to high school next year. His family is considering a high school in another district, one that may be a better fit.

With the right teachers, they're hoping Josh's newfound energy — both during school and after — extends beyond the pandemic.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Nearly one-in-five teens can’t always finish their homework because of the digital divide

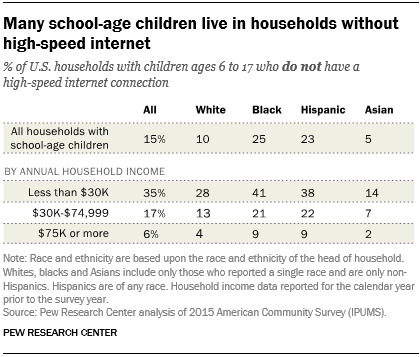

Some 15% of U.S. households with school-age children do not have a high-speed internet connection at home, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of 2015 U.S. Census Bureau data. New survey findings from the Center also show that some teens are more likely to face digital hurdles when trying to complete their homework.

School-age children in lower-income households are especially likely to lack broadband access. Roughly one-third of households with children ages 6 to 17 and whose annual income falls below $30,000 a year do not have a high-speed internet connection at home, compared with just 6% of such households earning $75,000 or more a year. These broadband disparities are particularly pronounced for black and Hispanic households with school-age children – especially those with low household incomes. (The overall share of households with school-age children lacking a high-speed internet connection in 2015 is comparable to what the Center found in an analysis of 2013 Census data.)

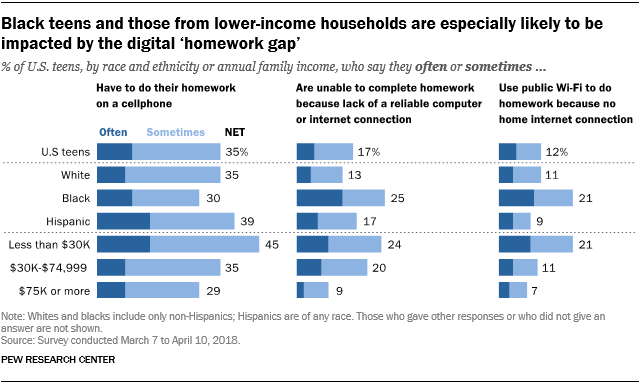

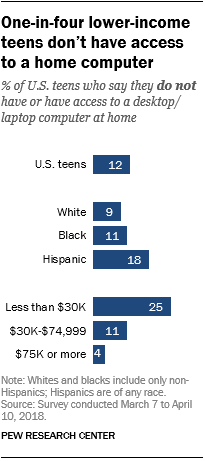

This aspect of the digital divide – often referred to as the “homework gap” – can be an academic burden for teens who lack access to digital technologies at home. Black teens, as well as those from lower-income households, are especially likely to face these school-related challenges as a result, according to the new Center survey of 743 U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 conducted March 7–April 10, 2018.

At its most extreme, the homework gap can mean that teens have trouble even finishing their homework. Overall, 17% of teens say they are often or sometimes unable to complete homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection.

This is even more common among black teens. One-quarter of black teens say they are at least sometimes unable to complete their homework due to a lack of digital access, including 13% who say this happens to them often. Just 4% of white teens and 6% of Hispanic teens say this often happens to them. (There were not enough Asian respondents in this survey sample to be broken out into a separate analysis.)

Teens also differ by income level when it comes to completing assignments: 24% of teens whose annual family income is less than $30,000 say the lack of a dependable computer or internet connection often or sometimes prohibits them from finishing their homework, but that share drops to 9% among teens who live in households earning $75,000 or more a year.

Other times, teens who lack reliable internet service at home say they seek out other locations to complete their schoolwork: 12% of teens say they at least sometimes use public Wi-Fi to complete assignments because they do not have an internet connection at home. Again, this problem is more prevalent for black or less affluent teens. Roughly one-in-five black teens (21%) report having to at least sometimes use public Wi-Fi for this reason, including 10% who say they often do so. And teens whose family income is below $30,000 a year are far more likely than those whose annual household income is $30,000 or higher to say that they do this (21% vs. 9%).

Lastly, 35% of teens say they often or sometimes have to do their homework on their cellphone. Although it is not uncommon for young people in all circumstances to complete assignments in this way, it is especially prevalent among lower-income teens. Indeed, 45% of teens who live in households earning less than $30,000 a year say they at least sometimes rely on their cellphone to finish their homework.

These findings reflect a broader discussion about the digital divide’s impact on America’s youth. Numerous policymakers and advocates have expressed concern that students with less access to certain technologies may fall behind their more digitally connected peers. There is some evidence that teens who have access to a home computer are more likely to graduate from high school when compared with those who don’t.

The Center’s survey of teens does show stark differences in teens’ computer access based on their household income. A quarter of teens whose family income is less than $30,000 a year do not have access to a home computer, compared with 4% of those whose annual family income is $75,000 or more.

Note: See full topline results and methodology here (PDF).

- Age & Generations

- Digital Divide

- Economic Inequality

- Education & Learning Online

- Teens & Tech

- Teens & Youth

Monica Anderson is a director of research at Pew Research Center

Andrew Perrin is a former research analyst focusing on internet and technology at Pew Research Center

How Teens and Parents Approach Screen Time

Who are you the art and science of measuring identity, u.s. centenarian population is projected to quadruple over the next 30 years, older workers are growing in number and earning higher wages, teens, social media and technology 2023, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- Home Planet

- 2024 election

- Supreme Court

- TikTok’s fate

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

The myth about smart black kids and “acting white” that won’t die

Nerds come in all colors.

If you buy something from a Vox link, Vox Media may earn a commission. See our ethics statement .

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: The myth about smart black kids and “acting white” that won’t die

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/52613011/shutterstock_383673616.0.jpg)

You've probably heard it before: Too many black students don't do well in school because they think being smart means "acting white."

Just last week, Columbia University English professor John McWhorter mentioned it in a piece for Vox to support his critique of elements of the Black Lives Matter platform. Key to his argument was the assertion that the similar goals of the 1960s “war on poverty failed,” in part, due to black people’s “cultural traits and behaviors.”

While the “acting white” theory used to be pretty popular to bring up in debates about black academic achievement there’s a catch: It’s not true.

At best, it's a very creative interpretation of inadequate research and anecdotal evidence. At worst, it's a messy attempt to transform the near-universal stigma attached to adolescent nerdiness into an indictment of black culture, while often ignoring the systemic inequality that contributes to the country's racial achievement gap.

Yet McWhorter — despite being a scholar of linguistics, not sociology — has become one of the primary defenders of the “acting white” theory and has dismissed those who debunk it as “pundits” who are “uncomfortable with the possibility that a black problem could not be due to racism.” But the people who challenge it are not pundits — they’re academics who’ve dedicated significant time and scientific scrutiny to this theory. Here’s why they say it’s a myth.

Where the “acting white” theory came from

The “acting white” theory — the idea that African-American kids underachieve academically because they and their peers associate being smart with acting white, and because they're afraid they'll be shunned — was born in the 1980s. John Ogbu , an anthropology professor at the University of California Berkeley, introduced it in an ethnographic study of one Washington, DC, high school. He found what he dubbed an "oppositional culture" in which, he said, students saw academic achievement as "white."

The acting white theory has since become a go-to explanation for the achievement gap between African-American students and their white peers, and is repeated in public conversations as if it's a fact of life.

Authors such as Ron Christie in Acting White: The Curious History of a Racial Slu r and Stuart Buck in Acting White: The Ironic Legacy of Desegregation have written entire books (heavy on personal observations, anecdotes, and theories) dedicated to the phenomenon.

Even President Barack Obama said in 2004 , when he was running for US Senate, " Children can't achieve unless we raise their expectations and turn off the television sets and eradicate the slander that says a black youth with a book is acting white."

Perhaps aware of some of the research debunking this as an academic theory in the intervening years, he noted in 2014 remarks related to the My Brother's Keeper program that it was "sometimes overstated." But he still offered the theory in the form of a personal observation, saying that in his experience, "there's an element of truth to it, where, OK, if boys are reading too much, then, well, why are you doing that? Or why are you speaking so properly?"

It's no surprise that the "acting white" narrative resonates with a lot of people. After all, it echoes legitimate frustrations with a society that too often presents a narrow, stereotypical image of what it means to be black. It validates the experiences of African-American adults who remember being treated like they were different, or being smart but not popular in school. And for those who are sincerely interested in improving educational equality, it promises a quick fix. ("If they would just stop thinking being smart was 'acting white,' they could achieve anything!")

The "acting white" theory also validates a particular social conservative worldview by placing the blame for disparate academic outcomes squarely on the backward ideas of black children and black cultural pathology, instead of on harder-to-tackle factors like socioeconomic inequality, implicit racial bias on the part of teachers, segregated and underresourced schools, and the school discipline disparities that create what's been called the school-to-prison pipeline .

The "acting white" research was weak to begin with

"The acting white theory is difficult to assess through research," Ivory Toldson — a Howard University professor, senior research analyst for the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, and deputy director of the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities — wrote at the Root in 2013. "Many scholars who claim to find evidence of this theory loosely interpret their data and exploit the expert gap to sell their finding," he said.

Despite abundant personal anecdotes by African Americans who say they were good students in school and were accused of acting white, there's no research that explicitly supports a relationship between race, beliefs about "acting white," social stigma, and academic outcomes.

Even those who claim to have found evidence of the theory, Toldson explained , failed to connect the dots between what students deem "white" and the effect of this belief on academic achievement.

"Observing and/or recording African-American students labeling a high-achieving African-American student as acting white does not warrant a characterization of African-American academic underperformance as a response to the fear of acting white," he said .

Studies suggest that the highest-achieving black students are actually more popular than the lowest-achieving ones

A prime example of a shaky study on this topic, according to Toldson, was Harvard economist Roland G. Fryer's 2006 research paper "Acting White: The Social Price Paid by the Best and the Brightest Minority Students ." Published by Education Next , the paper purported to affirm Ogbu's findings by using Add Health data to demonstrate that the highest-achieving black students in the schools Fryer studied had few friends. "My analysis confirms that acting white is a vexing reality within a subset of American schools," he wrote.

But the numbers didn't actually add up to support the "acting white" theory, Toldson said. To start, the most popular black students in his study were the ones with 3.5 GPAs, and students with 4.0s had about as many friends as those with 3.0s. The least popular students? Those with less than a 2.5 GPA.

It seemed that the "social price" paid by the lowest-achieving black students was actually far greater than the price in popularity paid by the highest academic achievers.

Fryer conceded this. He said there was "no evidence of a trade-off between popularity and achievement" for black students at private schools, poking another hole in the theory.

Plus, Toldson pointed out, even if the results had shown that the highest-achieving students at all schools had the fewest friends, that would have indicated a connection between grades and popularity, but wouldn't have supported the core of the "acting white" theory itself. "Methodologically, the study has to make the ostensible leap that the number of friends a black student has is a direct measure and a consequence of acting white," he explained .

In 2009, the authors of an American Sociological Review article, “The Search For Oppositional Culture Among Black Students,” concluded that high-achieving black students were in fact especially popular among their peers, and that being a good student increased popularity among black students even more so than for white students.

McWhorter has dismissed this study as one that “encourages us to pretend,” because he says that black kids may be dishonest when asked if they value school. It’s unclear why the suspicion of dishonesty only applies to black students and not the white students who were also studied. He’s also written the self-reports can’t be trusted because, according to reasoning he attributes to Fryer , “[a]sking teenagers whether they’re popular is like asking them if they’re having sex.” That may be fair, but it doesn’t explain the stronger link between being a good student and self-reports about popularity for black teens than for white teens.

In 2011, Smith College's Tina Wildhagen, in the Journal of Negro Education , tested the "entire causal process tested by the 'acting white' theory," using the Educational Longitudinal Study of 2002, and found that "the results lend no support to the process predicted by the acting white hypothesis for African-American students."

Research suggests that black students have more positive attitudes about education than white students

There is an established phenomenon called the attitude-achievement paradox , which refers to the way positive attitudes about school can fail to translate to successful academic outcomes among black students. Originated by Roslyn Mickelson in 1990, it's been the subject of extensive sociological research.

For example, in a study published in the American Sociological Review in 1998, James Ainsworth-Darnell and Douglas Downey, using data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study, found that black students offered more optimistic responses than their white counterparts to questions about the following: 1) the kind of occupation they expected to have at age 30, 2) the importance of education to success, 3) whether they felt teachers treated them well, 4) whether the teachers were good, 5) whether it was okay to break rules, 6) whether it was okay to cheat, 7) whether other students viewed them as a "good student," 8) whether other students viewed them as a "troublemaker," and 9) whether they tried as hard as they could in class.

Findings like these fly in the face of the idea that black students think academic achievement is "white" or negative, or that it's something they must actively shun for acceptance and popularity.

When Toldson analyzed raw data from a 2005 CBS News monthly poll of 1,000 high school students who were asked their opinions on being smart and other smart students, he saw this reflected again.

Students were asked, "Thinking about the kids who get good grades in your school, which one of these best describes how you see them: 1) cool, 2) normal, 3) weird, 4) boring, or 5) admired?" The responses of black boys, black girls, white boys, and white girls were around the same. But black boys were the most likely (17 percent) to consider such students "cool."

Students also answered this question: "In general, if you really did well in school, is that something you would be proud of and tell all your friends about, or something you would be embarrassed about and keep to yourself?" Eighty-nine percent of all students said they would be "proud and tell all." Black girls were top among this group, with 95 percent saying they'd be proud. Meanwhile, white boys, at 17 percent, were the most likely to say they would be "embarrassed or keep to self" or report that they "did not know" how they would handle the news that they were doing very well academically.

As recently as 2009, researchers have revisited the theory and confirmed the findings of pro-school attitudes among black students .

All racial groups have nerds

Fryer's research found that the very highest-achieving black kids were the least popular — but this likely had much less to do with beliefs about acting white and more to do with the fact that the very smartest kids of any race tend to suffer social stigma.

"In my own research , I have noticed a 'nerd bend' among all races, whereby high — but not the highest — achievers receive the most social rewards," Toldson said . "For instance, the lowest achievers get bullied the most, and bullying continues to decrease as grades increase; however, when grades go from good to great, bullying starts to increase again slightly. Thus, the highest achievers get bullied more than high achievers, but significantly less than the lowest achievers."

In a 2003 study titled "It's not a black thing: Understanding the Burden of Acting White and Other Dilemmas of High Achievement," published in the American Sociological Review , researchers concluded that the smartest black and white students actually had similar experiences and that the stigma was similar across cultures:

Typically, high-achieving students, regardless of race, are to some degree stigmatized as "nerds" or "geeks." School structures, rather than culture, may help explain when this stigma becomes racialized, producing a burden of acting white for black adolescents, and when it becomes class-based, producing a burden of "acting high and mighty" for low-income whites.

So very high-achieving kids of all races experience social isolation at times. This is why there are plenty of high-achieving black kids to provide anecdotes about being socially shunned (and there are probably plenty of white kids who could do the same, but there isn't the same appetite for collecting these stories to explain the white experience). There are also plenty of black kids — many of whom are also smart — who have been accused of "acting white." But there doesn't appear to be much of a basis to connect the two experiences.

Jamelle Bouie gave his take on the distinction between these two experiences in a 2010 piece for the American Prospect :

As a nerdy black kid who was accused of "acting white" on a fairly regular basis, I feel confident saying that the charge had everything to do with cultural capital, and little to do with academics. If you dressed like other black kids, had the same interests as other black kids, and lived in the same neighborhoods as the other black kids, then you were accepted into the tribe. If you didn't, you weren't. In my experience, the "acting white" charge was reserved for black kids, academically successful or otherwise, who didn't fit in with the main crowd. In other words, this wasn't some unique black pathology against academic achievement; it was your standard bullying and exclusion, but with a racial tinge.

Why it matters that we get this right

The "acting white" theory is tempting to believe because it does contain pieces of truth. Yes, there's a racial academic achievement gap. Yes, there are plenty of African-American adults eager to tell stories about how they were shunned because they were brilliant.

(McWhorter has vigorously defended the “acting white” theory against academic critics primarily by citing 125 letters he says he received from people describing their experiences that reflect the theory. While he argues that accounts in these letters should be accepted without question, he disregards data such as the scientific study responses indicating pro-school attitudes among black kids because of his view that “personal feelings are not reachable by direct questioning.”)

And, yes, some high-achieving black kids — like kids of all races — experience social stigma. These individual facts are painful, and they resonate with people in a way that makes it easy to blur what's missing from the "acting white" equation: an actual, causal connection between the accusations of acting white, social stigma, and lower academic outcomes. There isn't one.

It's particularly troubling that this myth persists, because stories about the sources of educational inequality can shape public attitudes and policy. A perfect example is in McWhorter’s recent Vox piece. Readers who believed his assertion about the “acting white” theory may have been more likely to be convinced of his larger argument that “cultural orientations” of black communities are a cause of inequality. That is, of course, a very damning charge that could shape attitudes about black people and perpetuate racism. But the most glaring problem with it is that it’s an outdated theory that has fallen out of favor with actual sociologists.

A continued willingness to believe that solutions lie in simply repairing backward attitudes about getting good grades will continue to distract from the real problems: poverty, segregation, discipline disparities, teacher biases, and other structural factors. Unfortunately, none of these issues are as easy to fix as simply changing the beliefs of black students.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In The Latest

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

You need $500. How should you get it?

What the backlash to student protests over Gaza is really about

Food delivery fees have soared. How much of it goes to workers?

So you’ve found research fraud. Now what?

How JoJo Siwa’s “rebrand” got so messy

Student protests are testing US colleges’ commitment to free speech

Black Americans homeschool for different reasons than whites

Visiting Assistant Professor of Sociology, Hamilton College

Disclosure statement

Mahala Dyer Stewart does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Hamilton College provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

When Michelle, a white stay-at-home mom, decided to homeschool her 8-year-old daughter, Emily, the decision was driven by what she saw as the lack of individualized attention at school.

“We wound up feeling frustrated that the school wasn’t following the child,” Michelle, a former communications specialist, explained of the decision by she and her husband, a software engineer, to homeschool their daughter.

She described her daughter as “exceptionally gifted” and said after repeated attempts to get her daughter’s school to provide advanced coursework, “it just felt like so much energy that I might as well do this thing myself.”

Michelle’s decision to homeschool stands in stark contrast to that of Lynette, a black mother who told me her son, Trevor, was seven when he started having a hard time in school.

“I don’t want to say that it was bullying but that’s what it kind of ended up being and it wasn’t from students,” Lynette explained. “It was from teachers.”

“He’s seven but he looks like he’s 10,” Lynette continued. “And they kind of acted like they were afraid of him. He’s never acted out violently but they made it sound like he was going to.”

Like Michelle, Lynette grew tired of making visits to her child’s school, but for a different reason.

“I just didn’t want to have to keep going to the principal’s office,” Lynette recalled during an interview at a cafe in the suburbs of a Northeastern city. “I’m like ‘you’re really targeting my kid for no reason because he’s the second biggest kid in the school.’”

Motives differ

The sharp contrast between Michelle and Lynette’s reason for homeschooling their children is common.

As a sociologist who has interviewed dozens of homeschooling parents, I’ve found that whereas most white parents homeschool to make sure their children get an education more tailored to their needs and talents, most black parents homeschool to remove their children from what they see as a racially hostile environment.

Now that schools are closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, families of all racial, ethnic and class backgrounds have been forced to spend more time educating their children at home, or at least making sure their children do whatever work the school has assigned.

It is unclear as to whether schools will reopen in the fall. It is also unclear how homeschooling – or at least the ability to oversee at-home learning – will be impacted by the pandemic. Based on existing research and data , I don’t see why reasons that parents previously decided to homeschool – whether they are black or white – will change or disappear. However, concerns about sending their children back to school amid the pandemic could become an additional reason.

Black students disciplined more

There is no shortage of research to support the view that America’s public schools treat black students more harshly than their white peers.

For example, a study by sociologists Edward Morris and Brea Perry found black boys are twice as likely as white boys to receive disciplinary action such as office referral, detention, suspension or expulsion. The same study found black girls are three times as likely as white girls to be disciplined for less serious and arguably more ambiguous behavior, such as disruptive behavior, dress code violations or disobedience.

The middle-class black mothers I interviewed say that despite their college education, salaries and advocacy on behalf of their children, they were unable to protect their children from the racial hostilities at school. The black families I spoke with told me they chose to homeschool only after they tried in vain to address discriminatory discipline practices at their children’s schools.

Money matters

Though the reasons why families chose to homeschool varies by race, other researchers and I have found that homeschooling is more common among two-parent households where one parent is the breadwinner and the other – most often the mother – educates the children. Homeschooling parents are also most often college-educated. One 2013 study found that among the 54 black homeschooling families interviewed, 42 of the families had one parent with at least a college degree, while many (19) also had graduate degrees.

If the ability to work from home makes it possible to homeschool, although incredibly challenging , data also suggest that homeschooling is more likely among families with higher incomes. That’s because the ability to work from home is largely tied to income. Federal labor data show that in 2017 and 2018, 61.5% of workers in the top income quartile could work from home. For workers in the second highest quartile, 37.3% could work from home. But for those in third and fourth highest income quartiles, only 20.1% and 9.1%, respectively, could work from home.

If reducing the risk of exposing their children to COVID-19 becomes a reason to homeschool this fall, these data would suggest that more well-to-do families are in a better position to see that their children are educated at home. By contrast, low-wage workers are less likely to easily exercise this choice. Some scholars speculate that this will lead to more well-off families deciding to continue their children’s learning at-home as a way to avoid virus exposure.

Future growth?

The percentage of U.S. children who are homeschooled rather than attending public and private schools was rising before the pandemic . Between 1999 and 2016 , the percentage of the school age population who were homeschooled doubled from 1.7% to 3.3%, or close to 1.7 million students.

Black homeschoolers account for roughly 8% of this population, up from an estimated 4% in 2007 . The 8% in 2016 represents 132,000 black homeschooling kids, according to the NCES data.

In 2017, black kids made up 15% of public school students, or 7.7 million kids of the roughly 50.7 million public school kids that year.

A 2019 federal report shows parents homeschool for a variety of reasons. Just 16% of homeschool families report moral or religious instruction as the primary reason for homeschooling, while 34% report their primary reason is concern with school environment. This report does not document how reasons vary by race. Yet my study would suggest that black parents, like Lynette, may be dissatisfied with school environment in very different ways than white parents, like Michelle.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend .]

- Homeschooling

- K-12 education

- School closures

- K-12 online learning

- School closings

- Pandemic school closures

Program Manager, Teaching & Learning Initiatives

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

Share this content

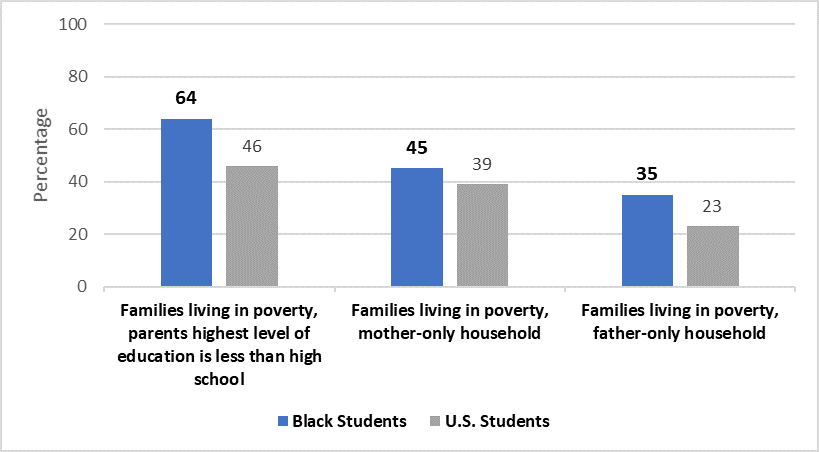

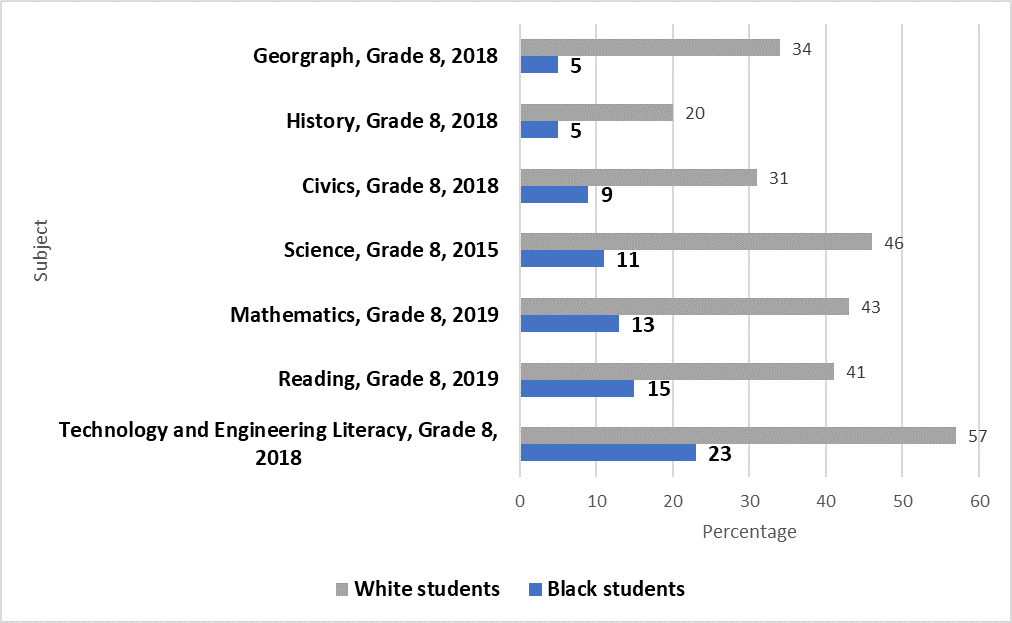

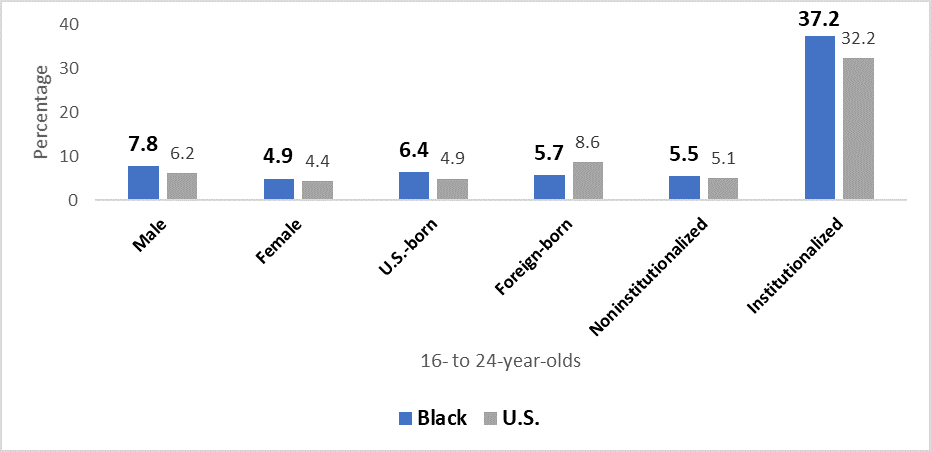

Black Students in the Condition of Education 2020

On May 25, a Black father, George Floyd, was tragically killed as a result of police brutality. Floyd has been described as a loving father of two girls who wanted to better his life and become a better father. His wish represents the desires of millions of American parents: to get out of poverty and be able to support their children with better education.

Better education for every student is a pivotal change that public schools are pursuing. However, the recently released congressionally mandated annual report — the Condition of Education 2020 — painted a very unsettling national picture of the state of education for Black students. The report, prepared by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), aims to use data to help policymakers and the public to monitor educational progress of all students from prekindergarten through postsecondary education in the United States.