- Open access

- Published: 21 April 2022

Domestic violence in Indian women: lessons from nearly 20 years of surveillance

- Rakhi Dandona 1 , 2 ,

- Aradhita Gupta 1 ,

- Sibin George 1 ,

- Somy Kishan 1 &

- G. Anil Kumar 1

BMC Women's Health volume 22 , Article number: 128 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

11 Citations

63 Altmetric

Metrics details

Prevalence of self-reported domestic violence against women in India is high. This paper investigates the national and sub-national trends in domestic violence in India to prioritise prevention activities and to highlight the limitations to data quality for surveillance in India.

Data were extracted from annual reports of National Crimes Record Bureau (NCRB) under four domestic violence crime-headings—cruelty by husband or his relatives, dowry death, abetment to suicide, and protection of women against domestic violence act. Rate for each crime is reported per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years, for India and its states from 2001 to 2018. Data on persons arrested and legal status of the cases were extracted.

Rate of reported cases of cruelty by husband or relatives in India was 28.3 (95% CI 28.1–28.5) in 2018, an increase of 53% from 2001. State-level variations in this rate ranged from 0.5 (95% CI − 0.05 to 1.5) to 113.7 (95% CI 111.6–115.8) in 2018. Rate of reported dowry deaths and abetment to suicide was 2.0 (95% CI 2.0–2.0) and 1.4 (95% CI 1.4–1.4) in 2018 for India, respectively. Overall, a few states accounted for the temporal variation in these rates, with the reporting stagnant in most states over these years. The NCRB reporting system resulted in underreporting for certain crime-headings. The mean number of people arrested for these crimes had decreased over the period. Only 6.8% of the cases completed trials, with offenders convicted only in 15.5% cases in 2018. The NCRB data are available in heavily tabulated format with limited usage for intervention planning. The non-availability of individual level data in public domain limits exploration of patterns in domestic violence that could better inform policy actions to address domestic violence.

Conclusions

Urgent actions are needed to improve the robustness of NCRB data and the range of information available on domestic violence cases to utilise these data to effectively address domestic violence against women in India.

Peer Review reports

The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target 5 is to eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls, and the two indicators of progress towards this are the rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) and non-partner violence [ 1 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated a 26% prevalence of IPV in ever-married/partnered women aged 15 years or more globally in 2018, and this prevalence is higher at 35% for southern Asia region in which India falls [ 2 ]. The self-reported domestic violence (majority by an intimate partner) in any form is reported between 33 to 41% among ever-married women from India [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Furthermore, the suicide death rate among women in India was reported to be twice the global rate [ 9 ], and housewives account for the majority of suicide deaths, the reasons for which are documented as “personal/social” [ 10 ].

Domestic violence was first recognized as a punishable offence in India in 2005 with the passing of the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (PWDVA) [ 11 , 12 ]. A significant focus of domestic violence against women in India has been on dowry-related harassment. Dowry is the transfer of goods, money and/or property from the bride’s family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage [ 13 ], initially meant to provide funds to women who were unable to inherit family property [ 14 ]. Dowry is very prevalent in India [ 15 ], and it has propagated domestic violence as means to extract money or property from the bride and her family [ 13 , 16 ]. While earlier sections of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) criminalized only dowry-related domestic violence, PWDVA expanded legal recourse for domestic violence beyond dowry harassment for more effective protection of the rights of women guaranteed under the Constitution who are victims of violence of any kind occurring within the family [ 11 ].

The major official source of surveillance for domestic violence in India are the reports compiled by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) [ 17 ]. Though under-reporting in NCRB reports is well documented for certain types of injuries [ 9 , 10 , 18 ], it remains the most comprehensive longitudinal source of domestic violence available at the state-level for India. We undertook a situational analysis for the years 2001 to 2018 using the NCRB reports to highlight the trends in the reported magnitude of domestic violence over time, to highlight the variations within country that could facilitate prioritization of immediate actions for prevention, and to discuss the limitations of the available NCRB reports for surveillance.

The primary source of the NCRB data is the First Information Report (FIR) completed by a police officer for any domestic violence incident which is compiled at the state level and provided to NCRB. FIR is a document prepared by police when they receive information about the commission of a cognizable offence either by the victim of the cognizable offence or by someone on their behalf [ 19 , 20 ]. It captures the date, time and location of offence, the details of offence, the details of victim and person reporting the offence, and steps taken by the police after receiving these details. The NCRB reports provide summary data based on these FIRs, which we utilized from 2001 to 2018 available in the public domain for this analysis. The details of data extracted and utilized are described below.

Type of data

Four crime headings corresponding to domestic violence related crimes against women were considered after consultation with legal experts who dealt with domestic violence cases based on the crime headings under which these are registered in India —cruelty by husband or his relatives, dowry death, abetment of suicide of women, and cases registered under PWDVA (Additional file 1 : Table S1). A case is filed under ‘cruelty by husband or his relatives’ (Section 498A of the IPC) when there is evidence of violence causing grave injury or of harassment to fulfil an unlawful demand for property [ 21 ]. Case of death of a woman within 7 years of marriage with evidence of dowry harassment is filed under dowry death (IPC Section 304B) [ 22 ]. As domestic violence is known as a risk factor for death by suicide among married women, we also considered the cases registered under abetment of suicide of women [ 23 ]. The cases under the PWDVA act criminalize perpetrators of domestic violence, defined to include physical, verbal, sexual, emotional and economic abuse in addition to dowry-related violence [ 11 ]. The NCRB reports data based on the “Principal Offence Rule,” which means that regardless of the number of offences under which a case of domestic violence is legally registered, it is reported only under the most serious crime heading by the NCRB [ 24 ].

Data extraction

NCRB reports included the number of cases filed as well as the number of victims under each of the four crime headings for 2014–2018 but reported only the number of cases filed from 2001 to 2013. The ratio of the number of cases to victims was 1.0 for 2014 to 2018, and hence we use the number of cases filed for this analysis from 2001 to 2018. Individual level-data is not published in the NCRB report.

Data for cruelty by husband or his relatives and for dowry death were available from 2001 to 2018, while data for abetment of suicide of women and PWDVA were available only from 2014 to 2018. We extracted the number of cases filed under each of the four domestic violence crime heads for each year for each state and for India. We also extracted data on the number of persons arrested under each crime category, which were available from 2001 to 2015 for the states and until 2018 for India. Here too, the data on abetment of suicide and PWDVA was available from 2014 to 2018 only. Lastly, we extracted data on the number of legal cases filed for these crimes and their current status in the judicial system. This legal data was available cumulatively for only India, and since it could not be extrapolated for each year from the tables, we analyzed this only for 2018.

Data analysis

Our analysis was aimed at understanding trends in the rate for each type of domestic violence crime heading. We calculated the rate of cruelty by husband or his relatives and dowry deaths from 2001 to 2018, and the rate of abetment of suicide of women and PWDVA from 2014 to 2018. As the NCRB reports do not specify the age of women who had reported these crimes, we assumed the age group of women to be 15–49 years to estimate the rates as the previous reports on domestic violence in India are predominately for women aged 15–49 years [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. We used the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study 2019 state-wise annual population estimates for women aged 15–49 years as the denominator [ 32 ], and report the rates per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years with 95% confidence intervals (CI) estimated for these rates. We report these rates across three administrative splits: nationally, by groups of state and individual state. The state groups were populated based on the Socio-demographic Index (SDI) computed by the GBD study, which uses lag distributed income, average years of education for population > 15 years of age, and total fertility rate [ 9 , 32 ].

To assess the trends in arrests related to domestic violence crimes, we computed the mean number of people arrested under each crime heading by dividing the number of people arrested with the total number of cases. The statistical analysis was done using MS Excel 2016, and maps were created using QGIS [ 33 ]. As this analysis used aggregated data available in the public domain, no ethics approval was necessary.

Cruelty by husband or his relatives

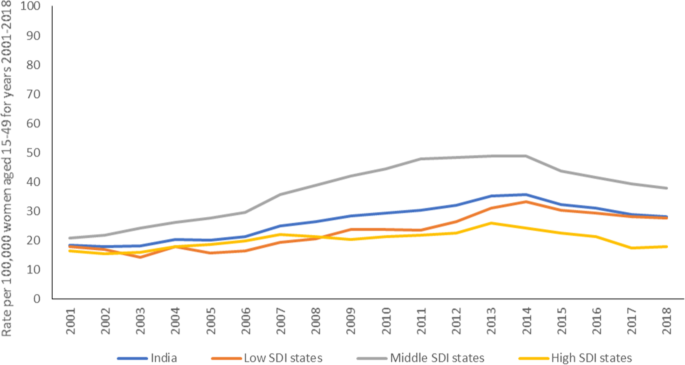

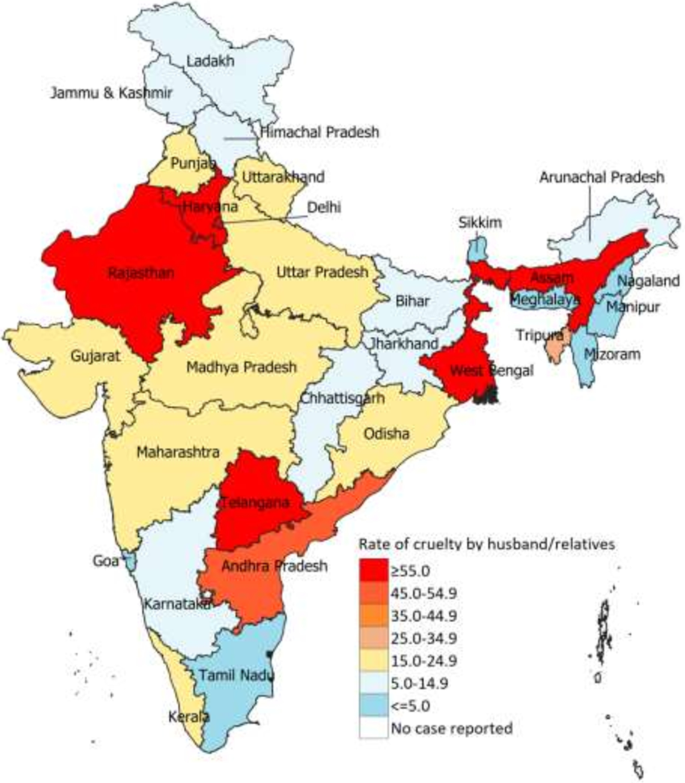

A total of 1,548,548 cases were reported under cruelty by husband or his relatives in India from 2001 to 2018, with 554,481 (35.8%) between 2014 and 2018. The reported rate of this crime in India was 18.5 (95% CI 18.3–18.6) in 2001 and 28.3 (95% CI 28.1–28.5) in 2018 per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years, marking a significant increase of 53% (95% CI 51.7–54.3) over this period (Table 1 ). This rate was 37.9 (95% CI 37.5–38.3) for the middle SDI states as compared with 27.6 (95% CI 27.4–27.8) in the low- and 18.1 (95% CI 17.8–18.4) in the high-SDI states in 2018 (Table 1 ). This reported crime rate remained higher in the middle SDI states between 2001 and 2018 as compared with the other states, reaching its highest levels between 2011 and 2014 (Fig. 1 ). Wide variations were seen in the rate for reported cruelty by husband or his relatives in 2018 at the state-level, which ranged from 0.5 (95% CI -0.05 0–1.5) in Sikkim to 113.7 (95% CI 111.6–115.8) in Assam (Table 1 and Fig. 2 ). The state of Delhi, Assam, West Bengal, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Jammu and Kashmir documented > 160% increase in this reported crime rate during 2001–2018 (Table 1 ). The greatest decline in the rate of this reported crime was seen in Mizoram, 74.3% from 2001 to 2018 (Table 1 ).

Yearly trend in the rate of cruelty by husband or his relatives per 100,000 women of 15–49 years, 2001–2018. SDI denotes Socio-demographic Index

Crime rate for cruelty by husband or his relatives per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years in 2018 in India, by state

Interestingly, the 53% increase in this reported crime rate between 2001 and 2018 for India was accounted for by increased rates for only a few states, and the rate remained stagnant in most states (Additional file 2 : Fig. S1, Additional file 3 : Fig. S2, Additional file 4 : Fig. S3). Only the states of Assam and Rajasthan among the low SDI states (Additional file 2 : Fig. S1), Andhra Pradesh and Tripura among the middle SDI states (Additional file 3 : Fig. S2), and Kerala and Delhi among the high SDI states (Additional file 4 : Fig. S3) showed increased reporting of this crime over the study period. The mean number of persons arrested under this crime in India decreased from 2.2 in 2001 to 1.1 in 2018, and the numbers were similar across the state SDI groups (Additional file 5 : Fig. S4).

Dowry deaths

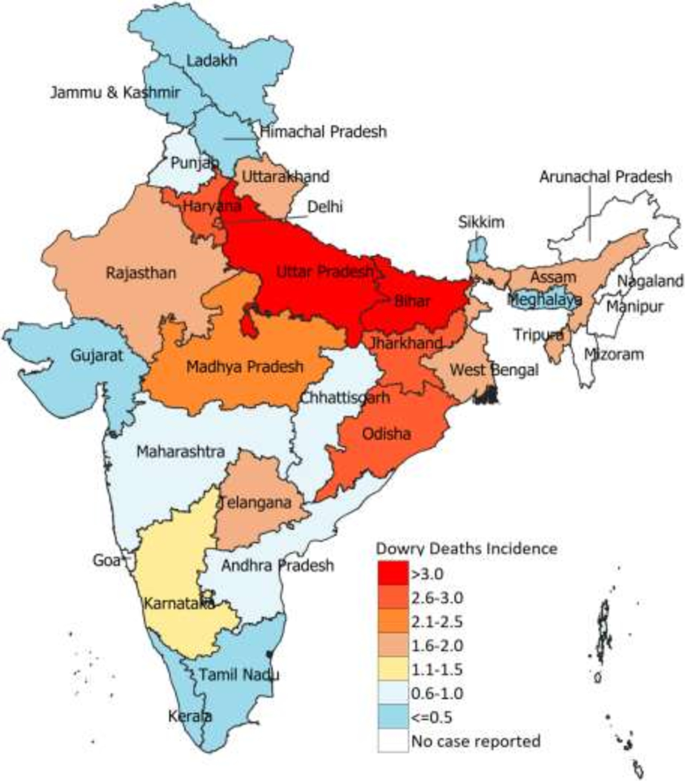

A total of 137,627 crimes were reported as dowry deaths between 2001 and 2018, with 38,342 (27.9%) cases between 2014 and 2018. The rate of this reported crime in India was 2.0 (95% CI 2.5–2.7) in 2018 per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years (Table 1 ). This rate in 2018 was 3.1 (95% CI 3.0–3.2) in the low-SDI states as compared to 1.2 (95% CI 1.1–1) in the middle- and 0.7 (95% CI 0.60–0.8) in the high-SDI states, and this trend was seen throughout the period studied (Table 1 ). At the state level in 2018, this rate ranged from 0.11 (95% CI 0–0.32) in Meghalaya to 4.0 (95% CI 3.8–4.2) in Uttar Pradesh; no cases were reported in Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Mizoram or Nagaland (Table 1 and Fig. 3 ). The largest decline in this rate was seen in the states of Tamil Nadu and Gujarat over the study period (Table 1 ).

Rate of dowry deaths per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years in 2018 in India, by state

The mean number of persons arrested for dowry deaths in India declined from 3 in 2001 to 2.3 in 2018. In 2001, this mean was markedly higher in the high-SDI states (4.9) than the low- (2.7) and middle- (2.6) SDI states. However, by 2015 this rate was higher in the low-SDI states (2.9) than high- (2.2) and middle- (1.8) SDI states (Additional file 5 : Fig. S4).

Abetment of suicide of women

Data under this crime head was available from 2014 to 2018, during which 22,579 cases were reported. The average rate of this crime was 1.27 (95% CI 1.25–1.29) per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years over this period. Overall, relatively higher rates were recorded in middle-SDI states (2.2; 95% CI 2.1–2.3), followed by high- (1.7; 95% CI 1.6–1.8) and low- (0.73; 95% CI 0.69–0.77) SDI states (Table 1 ). Notably, the middle- and high-SDI groups recorded a similar rate in 2014, after which the middle-SDI states recorded a steady increase in rate until 2017, while the high-SDI states saw an initial dip in 2015 and then an increase till 2017. The rate in the low-SDI states remained low throughout this period (Table 1 ).

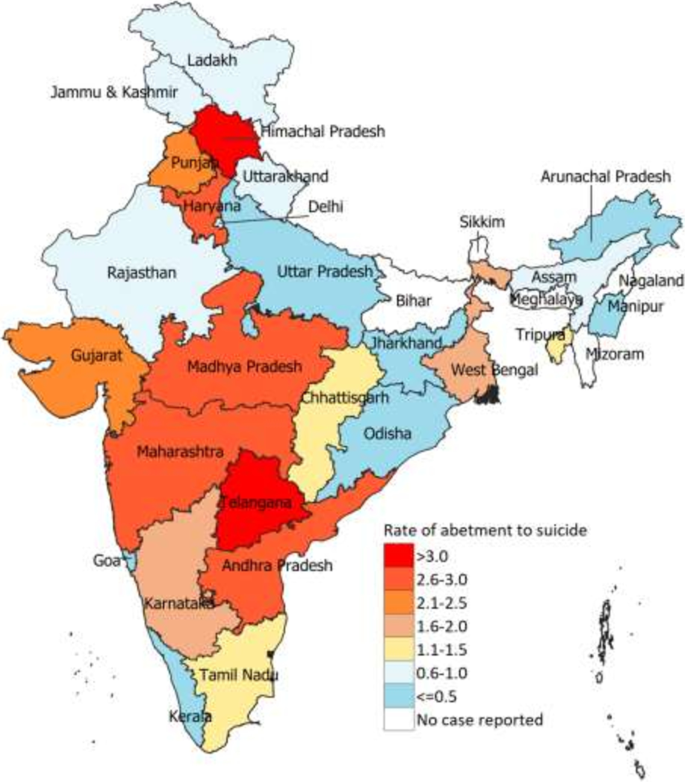

At the state-level in 2018, this rate ranged from 0.07 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.12) in Odisha to 4.0 (95% CI 3.6–4.4) in Telangana; no cases were reported in Bihar, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Sikkim and Nagaland (Table 1 and Fig. 4 ). While some states did not record any case, other states recorded significant changes between the 2014 and 2018. This rate in Tamil Nadu increased by 450% from 2014 to 2018, and West Bengal and Gujarat recorded an increase of over 100%, while this rate declined the most in Telangana, by 31% (Table 1 ). The mean number of persons arrested for this crime in India recorded a small increase from 1.4 in 2014 to 1.7 in 2018, and was similar across the state SDI groups (Additional file 5 : Fig. S4).

Rate of abetment of suicide of women per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years in 2018 in India, by state

PWDVA, 2005

A total of 2,519 cases were reported under PWDVA between 2014 and 2018, with an average crime rate of 0.14 (95% CI 0.13–0.15) per 100,000 women aged 15–49 years during this period (Table 1 ). Majority of the states did not report any case under this Act (Table 1 ). The mean number of persons arrested in India for this crime decreased from 1.6 in 2014 to 1 in 2018 (Additional file 5 : Fig. S4).

Status of the legal cases

A total of 658,418 cases were sent for trial in India in 2018, of which trial was completed in only 44,648 (6.8%) cases. Among the cases in which trial was completed, the offender(s) was convicted in only 6,921 (15.5%) cases.

In India between 2001 and 2018, the majority of domestic violence cases were filed under ‘cruelty by husband or his relatives’, with the reported rate of this crime increasing by 53% over the 18 years. However, it is important to note that only some states recorded change in the reported rate with the almost stagnant reported rate of domestic violence in many states over time. Significant heterogeneity was seen in the pattern of the four types of crimes at the state-level. Overall, the mean persons arrested decreased irrespective of the crime during the period studied, and less than 7% of the filed cases had completed legal trial in 2018. We discuss the gaps identified in the reported data which unless addressed have major implications in the facilitating action to reduce domestic violence against women in India.

The rate of reported crime under all the considered categories excluding dowry deaths in 2018 in India in the NCRB was close to the 33% self-reported domestic violence reported by women in the national survey in 2015–16 [ 3 ], though there is an indication that the prevalence of domestic violence could be as high as 41% in India [ 4 ]. The NCRB data provides passive surveillance with the source being the FIR filed by family/kin/community member with the police for a crime, and hence is dependent on the reporting from the community, which is known to be selective as women report less to the police for domestic violence due to various reasons including lack of social support, shame, and stigma [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. These differences could account for differential rates of domestic violence between the police records and self-reporting of domestic violence in the surveys [ 3 , 4 ]. Recently, it is also shown that how women are asked about domestic violence in surveys can also result in different estimates [ 38 ]. Furthermore, the Principal Offence Rule followed by NCRB "hides" many cases of domestic violence as according to this Rule, each criminal incident is recorded as one crime. If many offences are registered in a single case, only the most heinous crime—one that attracts maximum punishment—is considered as counting unit [ 39 , 40 ]. For example, an incident involving dowry death and cruelty by husband or relative will be reported in NCRB as dowry death as it warrants the maximum punishment, thereby, underreporting the number of cases with cruelty by husband or relative.

The cases under cruelty by husband or his relatives accounted for the majority of reported cases, and the rate of this reporting was comparatively higher in the middle-SDI states over the years studied. Previous research using field notes from cases reported to police indicate that victims are often in an environment that condones violence through active encouragement or tacit approval by the husband’s family members; and that many women lack social support as they experience violence from multiple perpetrators at home [ 34 , 41 ]. It is plausible that this rate is higher in the middle-SDI states because material wealth is highly prized among the Indian middle class, and dowry is seen as an easy path to greater wealth and social status [ 12 ]. A higher dowry demand, and a greater dissatisfaction from inability to meet these demands could possibly result in more domestic violence in these states [ 12 , 42 , 43 ]. Another possible factor in these states could be that the increasing female literacy in these states may be perceived as a threat to the prevalent power structures, prompting violence against women as a means to reinstate control [ 12 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ].

The middle-SDI states also had a higher rate of reported cases under abetment to suicide. The link between abuse and suicidal behaviour is well established, with research indicating that three out of ten women who undergo domestic violence are likely to attempt suicide [ 5 ]. Furthermore, a significantly higher suicide death rate is reported in Indian women than their global counterparts [ 9 ], and housewives account for the majority of these suicide deaths [ 10 ]. Wide state-level variations in the suicide death rate for women are also reported [ 9 ], and the relationship between the prevalence of domestic violence and suicide death rate needs to be explored further.

In contrast to the increased reporting of cases of cruelty over time, the rate of dowry death cases decreased from 2001 to 2018, with the low-SDI states recording the highest rate of dowry deaths. The dip in these cases may have resulted from the 2010 judgment requiring prior harassment of the victim associated with a dowry shortfall which made it harder to register a dowry death but presumably also harder to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that it was a dowry death, and not in fact.[ 48 ] Furthermore, qualitative research has shown that the families of dowry death cases deter from accusing the husband or his family due to fear of issues with up-bringing of the children of their daughter [ 47 ]. Also dowry deaths or related suicide deaths are less likely to be reported by the natal family, who fear social stigma and negative impact on marriages of their other daughters [ 42 , 49 ]. In this context, it is not easy to interpret the decreased number of cases of dowry deaths in India as actual fewer dowry deaths, for which more evidence is needed.

Very few cases were filed under PWDVA with the middle-SDI states reporting no cases during the period studied. While PWDVA defines domestic violence to include coercive behaviour as well as physical, sexual, emotional and economic abuse [ 11 ], in actuality only extreme forms of physical violence with evidence of injury are seen to evoke a legal response [ 12 ]. Interviews with victims indicate that unless they were able to offer a dowry claim or show evidence of grave physical violence, the police were either reluctant to file an FIR or offer PWDVA as a legal recourse to them [ 12 ]. It is also documented that the police, acting as social brokers, attempt to fit the reported domestic violence cases into ‘normal constructs’ frequently focusing on dowry harassment despite the broadened scope of the law as a recourse for domestic violence beyond dowry harassment [ 5 ]. Thus, data under this crime heading is unlikely to reflect the true picture of domestic violence against women in India.

The poor response of formal system to domestic violence is also reflected in the legal recourse as only 6.8% of the cases filed completed trials in 2018, with the majority of accused being acquitted. This bleak state of waiting, extended trials and low conviction is known to further discourage women from reporting [ 50 ]. The legal process is also influenced by the patriarchy driven attitudes of the police and people in the legal systems [ 44 ], and their unwillingness to act on domestic violence cases which they view as “private matter,”[ 13 , 44 ] such that many cases are not investigated, or dropped due to delay in filing [ 5 ]. In other cases, the investigation is based on the statement of the husband or relatives rather than fingerprints [ 13 ], with the perpetrator of violence not even recorded in over 90% of the cases [ 5 ]. Notably, little empirical research is available on the perceptions of abusive husbands and families on domestic violence that can facilitate intervention programs for abusive husbands [ 34 ].

Limitations and way forward

There are limitations to the data presented and the interpretation. The NCRB data depend on the availability and quality of data recorded by the police at the local level, which is known to have varied quality [ 9 , 10 , 18 ]. The findings have to be interpreted within in this limitation as it is not possible for us to comment on the extent of underreporting of data or the pattern of underreporting by type of crime, year or state. The heterogeneity in the NCRB data at the state level highlighted by the noisy trends or stagnant trend for certain states do not allow for a meaningful interpretation, and calls for a robust assessment of the reporting practices by the police and judiciary at state level to identify the gaps for inadequate documentation and underreporting that can facilitate appropriate corrective measures to improve data quality [ 18 ]. We assumed the age group of affected women to be 15–49 years. Though majority of the cases are likely to be in this age group given the other available information, the unavailability of age of women affected by the type of crime, year and state restricts understanding of the target women for prevention and action. Currently, the data are available in heavily tabulated fixed formats that limit the extent of disaggregated analysis. Because of non-availability of data on number of victims for some years, we assumed the ratio of the number of cases to victims based on the available data for other years. More informative analyses may also be possible if the NCRB reports allow for anonymized individual level data to be available in the public domain, including repeat reports of domestic violence by individual women.

Despite NCRB being a passive surveillance source, efforts can be made to improve the quality of information collected by the police during their routine tasks to improve utilisation of these data for planning action. The World Health Organization injury surveillance guidelines could provide practical advice on collecting systematic data on domestic violence, which can be more comparable over time and location [ 51 ]. Training and sensitisation of the police to address gender violence should also include standardisations in capturing of the data and the quality of data captured.

Disasters, natural or otherwise, disproportionately impact women and girls with some evidence suggesting that violence against women increases in disaster settings, however, there is a lack of rigorously designed and good quality studies that are needed to inform evidence-based policies and safeguard women and girls during and after disasters [ 52 ]. There has also been suggestion of an increase in domestic violence against women during the Covid-19 pandemic, globally [ 53 ] and in India [ 54 , 55 ]. In this context, the urgency to address the gaps highlighted in the NCRB data is even more for India to protect its women against domestic violence.

India needs to address the gaps in the administrative data to effectively respond to the SDG target five to eliminate all forms of violence against women. This longitudual analysis of the reported cases of domestic violence of nearly 20 years across the Indian states has highlighted the under-reporting and almost stagnant data, which hinders formulating of well-informed public health intervention strategies to reduce domestic violence in India.

Availability of data and materials

The domestic violence related data used in these analyses are available at NCRB website ( https://ncrb.gov.in ) and from the authors on request. The GBD population data used in these analyses are available at GBD Results Tool | GHDx (healthdata.org).

Abbreviations

Confidence interval

First information report

Global burden of disease

Indian penal code

National Crimes Records Bureau

National Family Health Survey

Protection of women from domestic violence act

Quantum geographic information system

Sustainable development goal

Socio-demographic index

World Health Organization

United Nations: Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; 2015.

World Health Organization. Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. Geneva: WHO; 2021.

Google Scholar

National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16. http://www.rchiips.org/nfhs .

Kalokhe A, Del Rio C, Dunkle K, Stephenson R, Metheny N, Paranjape A, Sahay S. Domestic violence against women in India: A systematic review of a decade of quantitative studies. Glob Public Health. 2017;12(4):498–513.

Article Google Scholar

International Center for Research on Women: Domestic Violence in India 2: a Summary Report of Four Records Studies. ICRW; 2000.

International Center for Research on Women: Domestic Violence in India 3: a Summary Report of a Multi-Site Household Survey. ICRW; 2000.

International Center for Research on Women.: Domestic Violence in India 1: a Summary Report of Three Studies. ICRW; 1999.

International Center for Research on Women.: Domestic violence in India, part 4. ICRW passion, proof, power. ICRW; 2002.

India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Suicide Collaborators. Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(10):e478–89.

Dandona R, Bertozzi-Villa A, Kumar GA, Dandona L. Lessons from a decade of suicide surveillance in India: who, why and how? Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):983–93.

PubMed Google Scholar

Government of India: Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005. In: 2005.

Sundari AYH, Roy A. Changing nature and emerging patterns of domestic violence in global contexts: Dowry abuse and the transnational abandonment of wives in India. Women’s Stud Int Forum. 2018;69:67–75.

Ravikant NS. Dowry deaths: proposing a standard for implementation of domestic legislation in accordance with human rights obligations. Mich J Gender Law. 2000;6(2):449.

Lolayekar AP, Desouza S, Mukhopadhyay P. Crimes Against Women in India: A District-Level Analysis (1991–2011). J Interpers Violence 2020:886260520967147.

The Woman Stat’s Project. Dowry, Bride Price and Wedding Costs. http://www.womanstats.org/vlbMAPS/images1/brideprice_dowry_wedding_costs_2correct.jpg .

Marriage Markets and the Rise of Dowry in India. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3590730

National Crime Records Bureau. http://ncrb.gov.in/ .

Raban MZ, Dandona L, Dandona R. The quality of police data on RTC fatalities in India. Injury Prev J Int Soc Child Adolescent Injury Prev. 2014;20(5):293–301.

Frequently asked questions about filing an FIR in India. http://www.fixindia.org/fir.php#1

First Information Report and You. https://www.humanrightsinitiative.org/publications/police/fir.pdf .

Government of India: Act No. 46 of 1983, Section 498a. http://www.498a.org/contents/amendments/Act%2046%20of%201983.pdf .

Government of India: Act No. 43 of 1986. Section 304B. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_5_23_00037_186045_1523266765688&orderno=342 .

Government of India.: Section 306. Abetment of Suicide. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_5_23_00037_186045_1523266765688&orderno=344

Crime in India. http://nrcb.gov.in .

Ram A, Victor CP, Christy H, Hembrom S, Cherian AG, Mohan VR. Domestic Violence and its Determinants among 15–49-Year-Old Women in a Rural Block in South India. Indian J Community Med. 2019;44(4):362–7.

Nadda A, Malik JS, Bhardwaj AA, Khan ZA, Arora V, Gupta S, Nagar M. Reciprocate and nonreciprocate spousal violence: a cross-sectional study in Haryana, India. J Family Med Primary Care. 2019;8(1):120–4.

Bhattacharya A, Yasmin S, Bhattacharya A, Baur B, Madhwani KP. Domestic violence against women: A hidden and deeply rooted health issue in India. J Family Med Primary Care. 2020;9(10):5229–35.

Leonardsson M, Sebastian M. Prevalence and predictors of help-seeking for women exposed to spousal violence in India—a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17(1):99.

George J, Nair D, Premkumar NR, Saravanan N, Chinnakali P, Roy G. The prevalence of domestic violence and its associated factors among married women in a rural area of Puducherry, South India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5(3):672–6.

Bondade S, Iyengar RS, Shivakumar BK, Karthik KN. Intimate partner violence and psychiatric comorbidity in infertile women—a cross-sectional hospital based study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2018;40(6):540–6.

Raj A, Saggurti N, Lawrence D, Balaiah D, Silverman JG. Association between adolescent marriage and marital violence among young adult women in India. Int J Gynaecol Obstetr. 2010;110(1):35–9.

India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Collaborators. Nations within a nation: variations in epidemiological transition across the states of India, 1990–2016 in the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet (London, England). 2017;390(10111):2437–60.

QGIS Geographic Information System: Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. http://qgis.org .

Bhat M, Ullman SE: Examining marital violence in India: review and recommendations for future research and practice. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2014;15(1):57–74.

Chowdhary NPV. The effect of spousal violence on women’s health: findings from the Stree Arogya Shodh in Goa, India. J Postgrad Med. 2008;54(4):306–12.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Burton B, Duvvury N, Rajan A, Varia N. (2000). Health records and domestic violence in Thane district Maharashtra [by] Surinder Jaswal. Summary report.

Johnson PS, Johnson JA. The oppression of women in India. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:1051–1068.

Cullen C. Method matters: underreporting of intimate partner violence in Nigeria and Rwanda. In: Open Knowledge Repository; 2020.

Aebi MF. Measuring the influence of statistical counting rules on cross-national differences in recorded crime. In: Shoham SG, Beck O, Kett M editors. International Handbook of Criminology. Boca Raton; 2010: 211–227.

Dutta PK. NCRB 2018: Have Indians become less criminal, more civilised? https://www.indiatoday.in/news-analysis/story/ncrb-2018-data-have-indians-become-less-criminal-more-civilised-1635601-2020-01-10

Burton B, Duvvury N, Rajan A, Varia N. (2000). Special Cell for Women and Children: a research study on domestic violence [by] Anjali Dave and Gopika Solanki. Summary report.

Lolayekar AP, Desouza S, Mukhopadhyay P. Crimes against women in India: a district-level analysis (1991–2011). J Interpers Violence 2020; 0886260520967147.

Pallikadavath S, Bradley T. Dowry, dowry autonomy and domestic violence among young married women in India. J Biosoc Sci. 2019;51(3):353–73.

Menon SV, Allen NE. The formal systems response to violence against women in India: a cultural lens. Am J Community Psychol. 2018;62(1–2):51–61.

Nanda P, Gautam A, Verma R, Khanna A, Khan, Brahme D, Boyle S, Kumar S: Study on masculinity, intimate partner violence and son preference in India. In: New Delhi: International Center for Research on Women; 2014.

Bhagat RB. The practice of early marriages among females in India: Persistence and change. In: Mumbai, India: IIPS; 2016.

Jeyaseelan V, Kumar S, Jeyaseelan L, Shankar V, Yadav BK, Bangdiwala SI. Dowry demand and harassment: prevalence and risk factors in India. J Biosoc Sci. 2015;47(6):727–45.

Dang G KV, Gaiha R. Why dowry deaths have risen in India. In: ASARC Working Paper. Brisbane: The Australian National University; 2018.

Belur JTN, Osrin D, Daruwalla N, Kumar M, Tiwari V. Police investigations: discretion denied yet undeniably exercised. Policing Soc. 2014;25(5):439–62.

Conviction Rate for Crimes Against Women Hits Record Low. https://thewire.in/gender/conviction-rate-crimes-women-hits-record-low .

World Health Organization. Injury surveillance guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

Thurston AM, Stöckl H, Ranganathan M. Natural hazards, disasters and violence against women and girls: a global mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(4):10.

Sediri S, Zgueb Y, Ouanes S, Ouali U, Bourgou S, Jomli R, Nacef F. Women’s mental health: acute impact of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(6):749–56.

Indu PV, Vijayan B, Tharayil HM, Ayirolimeethal A, Vidyadharan V. Domestic violence and psychological problems in married women during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: a community-based survey. Asian J Psychiatry. 2021;64:102812.

Iyengar J, Upadhyay AK. Despite the known negative health impact of VAWG, India fails to protect women from the shadow pandemic. Asian J Psychiatry. 2022;67:102958.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Amit Kumar Chetty and Parijat Singh for help with downloading and formatting of the data.

This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [INV-004506]. Under the grant conditions of the Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Public Health Foundation of India, Plot No. 47, Sector 44, Institutional Area, Gurugram, Haryana, 122002, India

Rakhi Dandona, Aradhita Gupta, Sibin George, Somy Kishan & G. Anil Kumar

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, USA

Rakhi Dandona

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

RD and GAK conceptualised this paper. RD drafted the manuscript with contributions from AG and GAK. SG, SK and GAK performed data analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation and agreed with the final version of the paper. RD and GAK had full access to all the data in the study and had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors had access to the estimates presented in the paper. RD and GAK verified the data underlying this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rakhi Dandona .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The analysis is presented on secondary administrative data available in public domain which does not require consent to participate or ethics approval. All human data are reported in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

. Definitions of crime headings considered under domestic violence. IPC denotes Indian Penal Code.

Additional file 2

. Crime rate for cruelty by husband or his relatives per 100,000 women aged 15-49 years in the Indian states categorised as having low Socio-demographic Index, 2001-18.

Additional file 3.

Crime rate for cruelty by husband or his relatives per 100,000 women aged 15-49 years in the Indian states categorised as having middle Socio-demographic Index, 2001-18. Telangana state not shown as it was formed in 2014.

Additional file 4.

Crime rate for cruelty by husband or his relatives per 100,000 women aged 15-49 years in the Indian states categorised as having high Socio-demographic Index, 2001-18.

Additional file 5.

Mean numbers of persons arrested under cruelty by husband or his relatives and dowry deaths for the years 2001-2018, and under abetment of suicide of women and PWDVA for the years 2014-2018. SDI denotes Socio-demographic Index. The state wise data for mean number of persons arrested was available until 2015 only.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dandona, R., Gupta, A., George, S. et al. Domestic violence in Indian women: lessons from nearly 20 years of surveillance. BMC Women's Health 22 , 128 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01703-3

Download citation

Received : 07 October 2021

Accepted : 07 April 2022

Published : 21 April 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01703-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Domestic violence

- Intimate partner

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 05 November 2021

Trends and correlates of intimate partner violence experienced by ever-married women of India: results from National Family Health Survey round III and IV

- Priyanka Garg 1 na1 ,

- Milan Das 2 na1 ,

- Lajya Devi Goyal 1 &

- Madhur Verma 3

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 2012 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7008 Accesses

13 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

The study aims to estimate the prevalence of Intimate partner violence (IPV) in India, and changes observed over a decade as per the nationally representative datasets from National Family Health Surveys (NFHS) Round 3 and 4. We also highlight various socio-demographic characteristics associated with different types of IPV in India. The NFHS round 3 and 4 interviewed 124,385, and 699,686 women respondents aged 15–49 years using a multi-stage sampling method across 29 states and 2 union territories in India. For IPV, we only included ever-married women (64,607, and 62,716) from the two rounds. Primary outcomes of the study was prevalence of the ever-experience of different types of IPV: physical, emotional, and sexual violence by ever-married women aged 15 to 49 years. The secondary outcome included predictors of different forms of IPV, and changes in the prevalence of different types of IPV compared to the previous round of the NFHS survey.

As per NFHS-4, weighted prevalence of physical, sexual, emotional, or any kind of IPV ever-experienced by women were 29.2%, 6.7%, 13.2%, and 32.8%. These subtypes of IPV depicted a relative change of − 14.9%, − 30.2%, − 11.0%, − 15.7% compared to round 3. Significant state-wise variations were observed in the prevalence. Multivariate binary logistic regression analysis highlighted women's and partner’s education, socio-economic status, women empowerment, urban-rural residence, partner’s controlling behaviours as major significant predictors of IPV.

Conclusions

Our study findings suggest high prevalence of IPV with state-wise variations in the prevalence. Similar factors were responsible for different forms of IPV. Therefore, based on existing evidences, it is recommended to offer adequate screening and counselling services for the couples, especially in health-care settings so that they speak up against IPV, and are offered timely help to prevent long-term physical and mental health consequences.

Peer Review reports

Strengths and limitations of the study

One of the very first comprehensive assessment of the different types of IPV using data from the third and fourth rounds of the National Family Health Survey India.

Predictors of IPV were estimated through a weighted analysis, that helped in highlighting certain feasible actionable points

Large and nationally representative data on violence were analysed from India.

Appropriate sampling during the survey makes the results generalisable, and recommendations can be adopted by other Lower Middle Income countries.

The use of only the predetermined variables to predict IPV is the key limitation to this analysis as there are many other variables apart from those included in the NFHS that affect IPV.

Lastly, self-reporting may under-estimate the overall prevalence of the IPV, owing to the fear, economic dependence, humiliation, and the feeling of severe confinement by the women.

Introduction

Spousal or Intimate partner violence (IPV) is one of the most common forms of domestic violence (DV), and refers to any physically, psychologically, sexually, or economically harmful behavior in an intimate relationship [ 1 ]. The three levels of IPV are Level I abuse (pushing, shoving, grabbing, throwing objects to intimidate, or causing damage to property and pets), Level II abuse (kicking, biting, and slapping), and Level III abuse (use of a weapon, choking, or attempt to strangulate) [ 2 ]. IPV takes place across different age groups, genders, sexual orientations, economic, or cultural status. The World Health Organization (WHO) recently estimated that almost one-third of women who have been in a relationship have experienced IPV [ 3 ]. Other studies have depicted the prevalence of IPV in the range of 13 - 61% in women (15–49 years old) [ 3 ]. As per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) round 4, the prevalence of IPV ranges between 3 - 43% in different states of India. Marital violence acceptability is amongst the highest in the world (52% women, and 42% men) [ 4 ]. The magnitude of IPV is underestimated as many studies indicate the difficulty of obtaining clear figures about prevalence of IPV in general population [ 5 , 6 ]. This is because of the under reporting which can be attributed to the fear of reprisal by the perpetrator, economic dependence on the spouse, a hope that IPV will stop, humiliation, loss of social prestige, and the feeling of severe confinement. However, there are anecdotal evidences which suggest that approximately nine out of ten of victims of IPV don’t disclose such mis-happenings and suffer all alone.

Ecological model has been preferred by many scientists around the world to understand IPV, according to which violence is an outcome of interaction between multiple causal agents operating at individual, relationship, community and societal levels [ 3 ]. There are various culturally specific norms that exist at these levels. These norms offer social standards of appropriate and inappropriate behavior that may favor or discourage IPV [ 7 ]. For instance, India had a deep-rooted patriarchal society, with preference to male child. It has been observed that Indian states with anisometric sex-ratios of first births favouring males, women with first born sons are less likely to experience IPV than those with first born daughters and, among those who have experienced IPV once, are more likely to experience it again [ 8 ]. Then, there are societal issues that act as perpetrators of IPV like dowry, inequities in education, and decision making powers. Spousal factors like alcohol, and other substance abuse, unemployment, challenges to masculinity norms are significant factors. At individual levels, IPV is more pronounced among less educated and poor women. High level of IPV and its acceptability in society corroborates with other factors that point towards gender discrimination and other social inequalities [ 9 ]. All these factors depicts the link between sex-discrimination and IPV at the household level, which is bolstered in an environment where females are regularly downplayed [ 10 , 11 ].

There is a substantial evidence suggesting that IPV may act an causal agent to a plethora of acute and chronic physical, mental, and sexual health problems [ 12 ]. Abused women commonly suffer from chronic gynecological problems, including chronic pelvic pain, sexually-transmitted diseases and vaginal bleeding, and present very frequently to healthcare services and require a wide range of medical services [ 13 ]. Other conditions affecting abused women include chronic pain such as back pain and headaches, neurological symptoms such as fainting and seizures, and gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel disease [ 14 , 15 ]. IPV is also a significant risk to pregnant women and their unborn children. The WHO recently reported that abused women have two times higher chances of having an abortion, miscarriage, premature birth, fetal injury, and low birth weight baby [ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Apart from physical injuries, abused women have a lot of mental health problems like depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Such women also suffer from low self-esteem and hopelessness [ 23 ]. These problems impact upon women’s ability to parent their children [ 24 ]. In addition, there are also wider economic societal implications of IPV that needs to be considered.

Around the world, considerable attention is being given to IPV. For instance, European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights affirmed in 2015 that IPV can be perceived as an infringement of human rights and dignity [ 25 ] . On similar lines, the United States Department of Justice stated that IPV has a considerable impact on victim, as well as family members, and other acquaintance of both the abuser and the victim [ 26 ]. In this sense, children who witness violence while growing up can be severely emotionally damaged. In India, IPV has been recognized since 1983 as a criminal offense under Section 498-A of the Indian Penal Code, and is comprehensively defined in the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (PWDVA) 2005, which came into effect in 2006 [ 27 ]. Even after the enactment of the Act, over the last decade, the rate of decline in IPV prevalence has remained abysmally low in India.

Management of IPV demands a need for multi-pronged collaboration between different stakeholders at various levels of the ecological framework. Though, individual-level interventions are comparatively easy to assess, evaluation of multi-component programmes and institutional-wide reforms is more challenging, and are also the most under-explored [ 12 ]. The existing literature describes all kind of violence comprehensively, and doesn’t attempt to explain the differences in the socio-demographic variations observed in the various forms of violence like physical, sexual and emotional type. Each type of IPV may have its own correlates, and management strategies. Hence, they need to be studied separately. For instance, similar counselling sessions cannot be given to women experiencing sexual violence by alcoholic husband and emotional violence instigated by the non-earning husband. Health care providers can play a pertinent role in identifying women who are experiencing IPV and halting the agonizing cycle of abuse through screening, timely support, and offering suitable prevention and referral options [ 28 ]. They are often the first professionals to offer care to women facing IPV. Therefore, this study attempts to explain the experience of IPV in India, and changes observed in the prevalence of various forms of IPV after the enactment of the PWDVA 2005, through the use of nationally representative datasets from NFHS round 3 and 4. We will also attempt to highlight various socio-demographic characteristics associated with physical, sexual and emotional type of IPV in India. The results of such analysis using a national survey holds merits compared to a sub-national estimates, to give a comprehensive picture about the IPV, and deduce meaningful interpretations for advocacy, and policy making.

Methodology

Study design.

A repeated, independent, cross-sectional ecological study design was used in the present study.

Data source

The present study uses data from the third and fourth rounds of the NFHS conducted in 2005–06 and 2015–16. The NFHS is India’s version of the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). In NFHS-3, all 28 states and New Delhi were covered, while NFHS included all 29 states and all union territories using a multistage stratified cluster sampling procedure for data collection. The NFHS-3 and 4 included women and men aged between 15–49 and 15-54 years in the primary sample. The design of the study, sampling strategy, and other details of the NFHS-3 and 4 can be found in the NFHS report (IIPS & ICF International, 2007,2017). The surveys collected information on child and maternal health, family welfare and domestic violence including IPV.

The NFHS follows both Indian and international guidelines, e.g. WHO ethical guidelines for research on domestic violence against women, 2001, for the ethical collection of data on violence. NFHS-4 sample size was approximately 699,686 women, up from about 124,385 women of NFHS-3. Domestic violence related questions were included in the state module, where about 68% in NFHS-3 and 15% in NFHS-4 of the total sample was selected for the interview. It should be noted that to assess DV, a total of 84,703 women (never-married 14,219, ever-married 64,607, others 5877) were interviewed during NFHS-3 survey, while a total of 79,729 women (never-married 13,716, ever-married 62,716, others 3297) were interviewed during NFHS-4 survey.

Study participants

From each household, only one woman was invited to complete the DV module, and sample weights, specific to the estimation of DV, were calculated to adjust for the selection and ensure that the DV subsample is nationally representative. Of all the women who were invited for the DV module, we only included 64,607 and 62,716 ever married women from the round 3 and 4 in our analysis.

Study variables

Dependent variables.

The main dependent variables for this analysis are the ever-experience of different types of IPV: physical, emotional, and sexual violence by a partner of ever-married women aged 15 to 49 years. In both the NFHS-3 and-4, DV is defined to include violence by spouses as well as by other household members [ 29 , 30 ]. However, it is well documented that IPV is one of the most common forms of violence experienced by married women [ 3 ].

The set of questions in NFHS survey attempts to capture detailed information on physical, sexual and emotional IPV. Information is obtained from ever-married women on violence by husbands and by others, and from never married women on violence by anyone, including boyfriends. In NFHS-3 & 4 surveys, spousal physical, sexual and emotional violence for ever-married women is measured using the following module of questions.

Physical violence

Physical IPVs was defined as any type of physical violence experienced by a woman at the hands of husband/partner, which includes: (a) ever having been slapped; (b) ever having had arm twisted or hair pulled; (c) ever having been pushed, shaken or had something thrown at them; (d) ever having been punched with fist or hit by something harmful; € ever having been kicked or dragged; (f) ever having been strangled or brunt; (g) ever having been threatened with knife/gun or other weapon.

Sexual violence

The Sexual IPVs was captured by three questions: a) ever having been physically forced you to have sexual intercourse with him even when you did not want to; b) ever having been physically forced you to perform any other sexual acts you did not want to c) ever having been forced you with threats or in any other way to perform sexual acts you did not want to.

Emotional violence

(a) ever having been said or done something to humiliate you in front of others b) ever having been threatened to hurt or harm you or someone close to you c) ever having been insulted you or make you feel bad about yourself.

The expected responses to all the above questions were coded as either ‘never’, ‘often’, ‘sometimes’, ‘yes but not in the last 12 months’. Of these, all response except ‘never’ to the questions related to IPVs implied experience of physical, sexual and emotional violence respectively. For the ease of analysis, all responses except ‘never’ were coded as Yes = 1, while never was coded as No = 0.

Independent variables

The independent variables were categorized as per the women’s individual, partner, family level factors. The selection of these variables were based upon extensive literature review. All those variables that have been highlighted in previous studies from India and abroad, and were available in the DHS datasets were included in our study [ 11 , 27 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Individual level factors included her age, education status, age at first marriage, parity, and economic empowerment status; and partner level factors included his education status, controlling behavior, and history of substance abuse like alcohol. Family factors included duration of cohabitation in years, number of co wives, and history of witnessing parental violence, while the household and community level factors included the wealth status, religion, place of residence, and region of the country.

These variables were categorized as age (15–19, 20–24, 25–34, 35+), educational attainment (no education, primary, secondary and higher), wealth quintile status (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest), religion (Hindu, non-Hindu), place of residence (urban, rural), region of India classified as North, Central, East, Northeast, West, and South. The North region includes Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Chandigarh, Uttarakhand, Haryana and Delhi; the Central region includes, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh; the East region includes West Bengal, Jharkhand, Odisha and Bihar; the North-east region includes Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura, Meghalaya and Assam; the West region includes Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa; and finally, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Puducherry belong to the South region. Parity was categorized as 0 = None, 1 = 1–2 parity,2 = 3+ parities. Economic empowerment was considered if women had ownership of property (house and land) or was gaining earnings from her work. It was obtained by merging women responses to questions: does a respondent: a) own a house? b) own land [either alone or jointly with a partner for both questions a) and b)] and c) type of earning from her work. The analysis dichotomized question c into paid (cash only, cash and in kind, and in kind only) and not paid. Any one of the three questions a, b, or c indicated a ‘yes’ that a woman is considered empowered and ‘no’ meant non empowerment. Responses to these questions were recorded into two categories (0 = Not empowered, 1 = Empowered).

The variable ‘Age at marriage’ was categorized as 0 = less than or equal to 18 years, 1 = more than 18 years. ‘Witnessing parental violence’ was measured by a question that asked- ‘whether the respondent’s father had ever beat her mother’, which was recorded dichotomously (0 = NO, 1 = Yes). ‘Duration of cohabitation in years’ was categories as 0 = 0–4, 1 = 5–9, 2 = 10–14,3 = 15–19 and 4 = 20 + years. ‘Number of co-wives’ were categories as 0 = None, 1 = One and more.

To measures the partner’s controlling behavior, respondents were asked- “Does your partner ever or did; a) Prohibit you to meet female friends? b) Limit you contact your family? c) Insist on knowing where you are at all times? d) Is jealous if you talk with other men? And e) Frequently accuses you of being unfaithful?” These questions were merged into one variable the “partner’s controlling behaviors”. Any positive response (yes) to any of the above questions implies the existence of such behavior and no to all the questions implied nonexistence of such behaviors. The partner’s alcohol consumption was measured by responses to the questions, “Does your partner drink alcohol?” and it had a binary outcome (0 = No, 1 = Yes). Frequently of a partner being drunk was follow-up question to those respondents whose partners indicated that the partner drank alcohol.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in the study.

Data analysis

Due permissions were sought from the Demographic and Health Survey program for data access and analysis after submitting the protocol and study objectives [ 35 ]. NFHS-3 and 4 datasets were imported into Stata version 14 for analysis. We calculated the weighted prevalence of each type of IPVs ever experience by the female respondents by doing univariate analysis separately for NFHS rounds 3 and 4 to get nationally representative estimates. Logistic regressions were used to estimate the unadjusted (OR) and adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) to depict the association of ever experience of different types of IPVs by the respondent with the independent variables. We used the domestic violence weighting variable (d005) included in the NFHS data and the Stata survey (svy) command to weight the data during the analysis in order to account for the complex survey design. We also explored the relative change in the different types of IPVs between two rounds of NFHS surveys in India.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a secondary analysis of a nationally representative survey dataset NFHS-4 (2015–16) which is in public domain. The Institute Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bathinda waived off the need for ethical clearance for this study wide letter no. IEC/AIIMS/BTI/032.

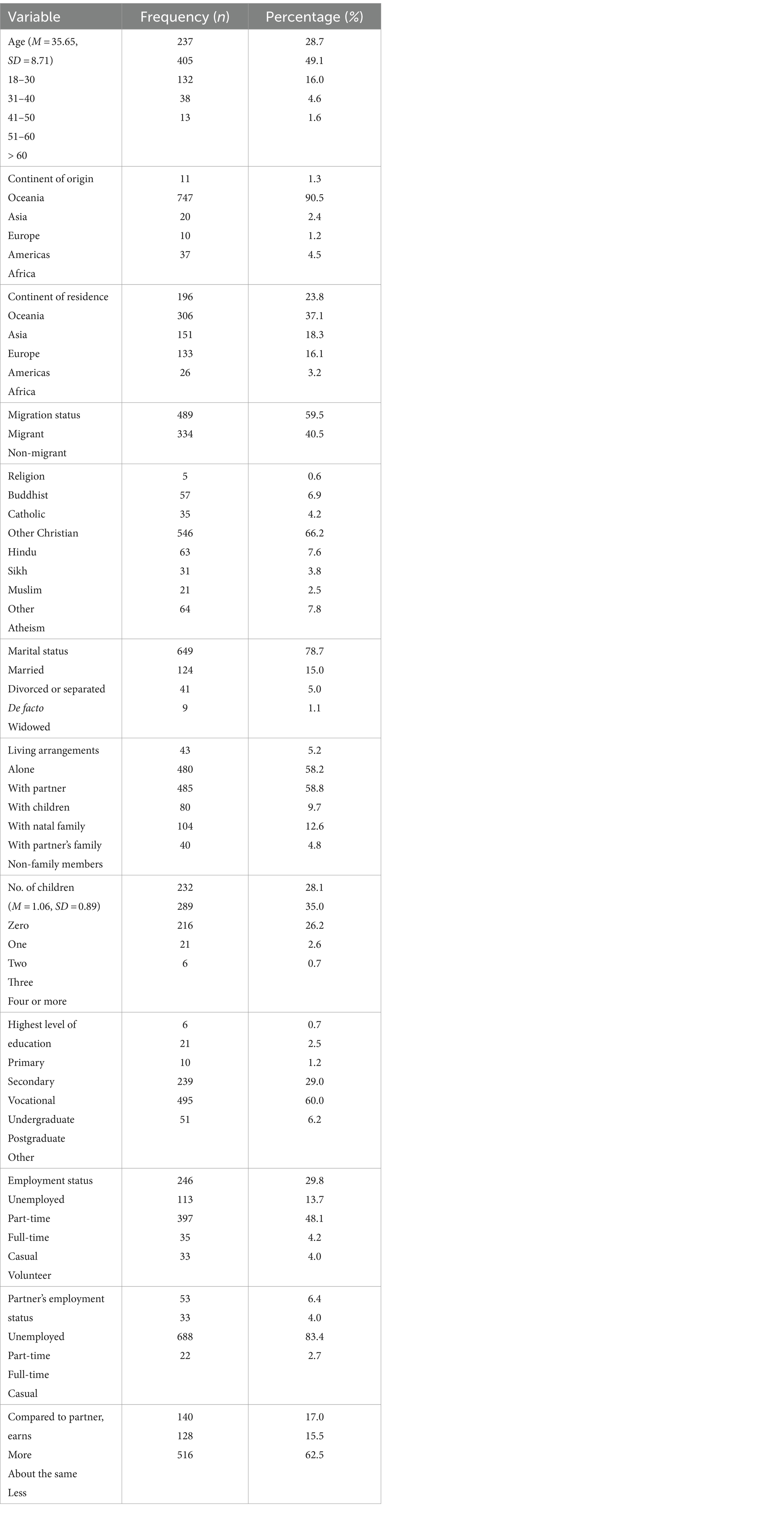

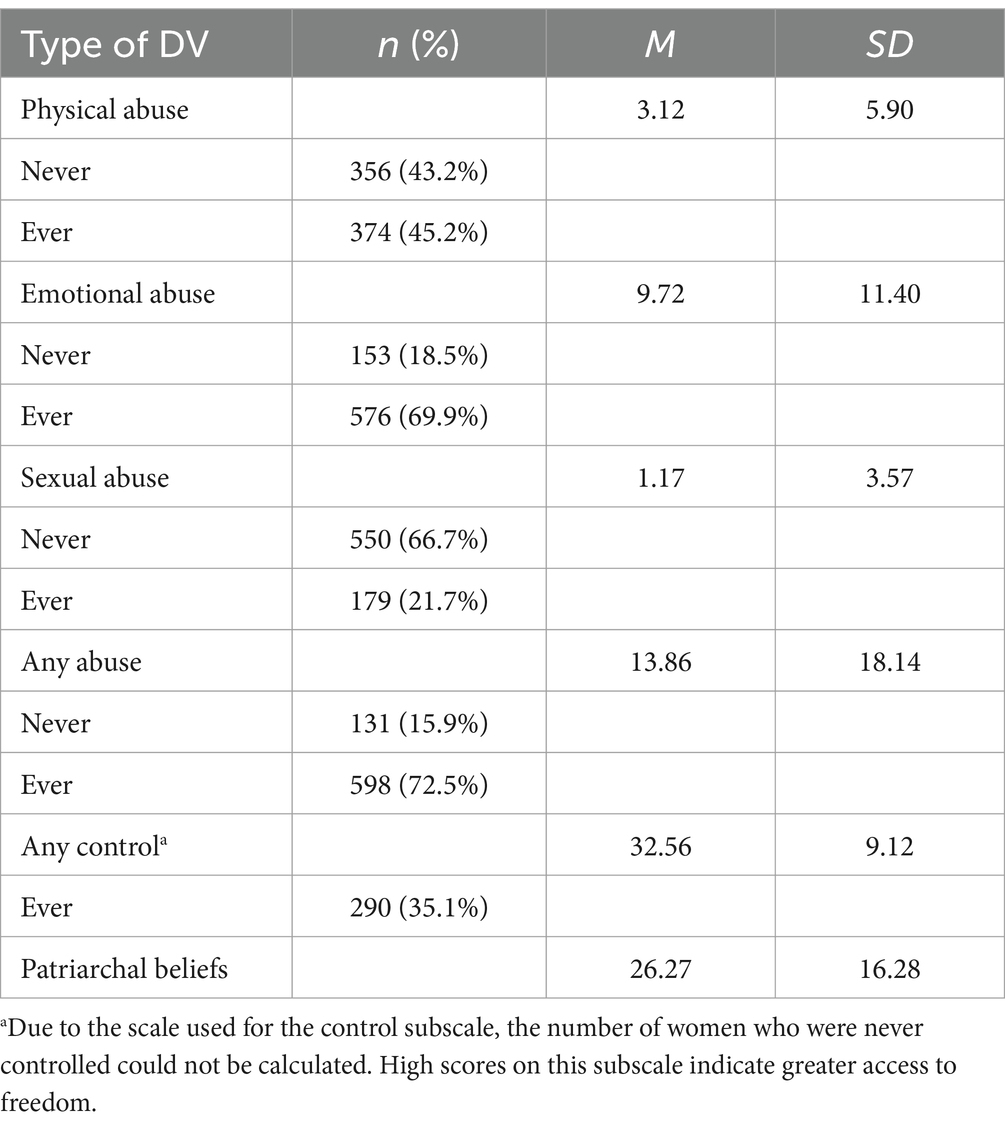

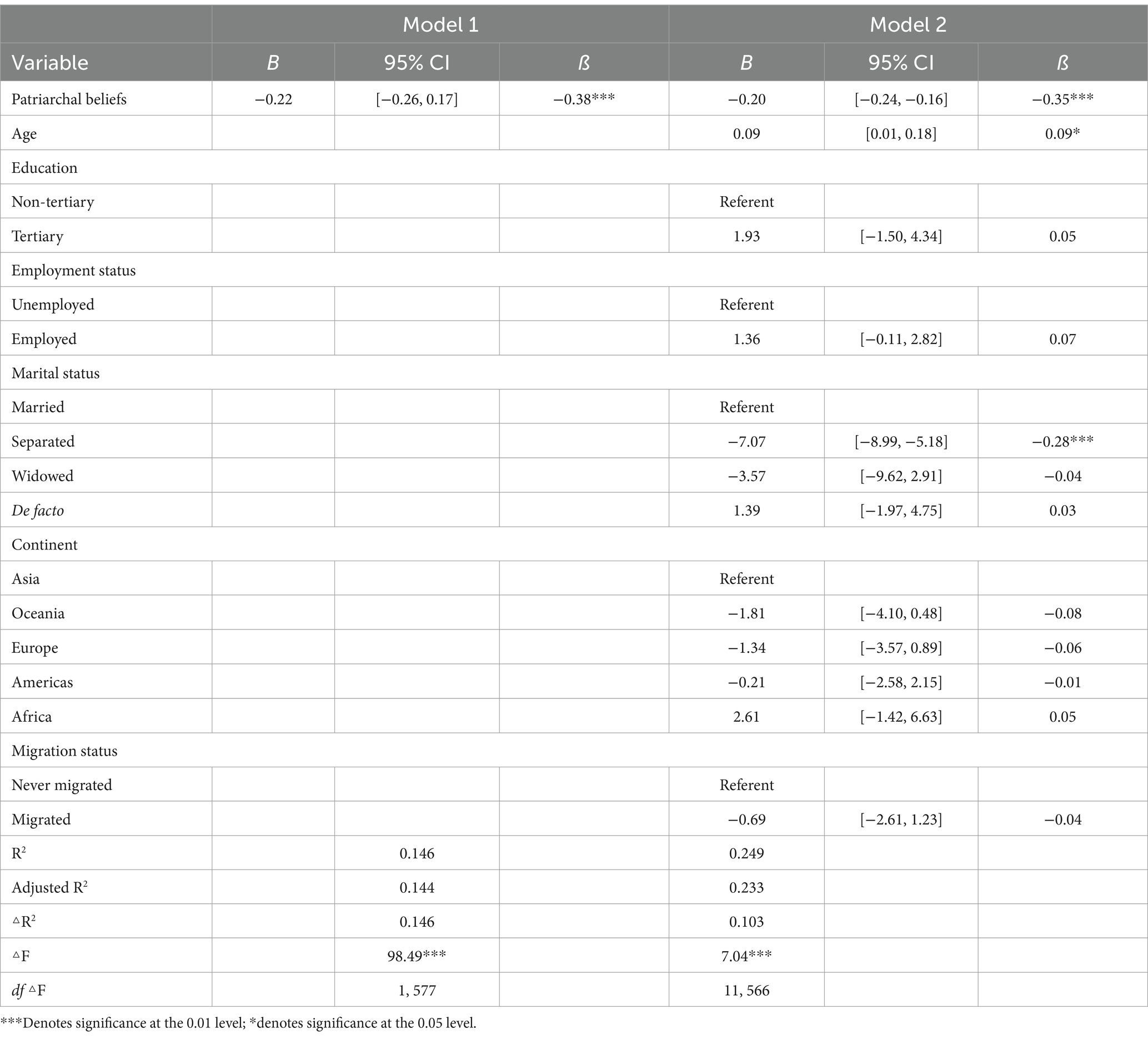

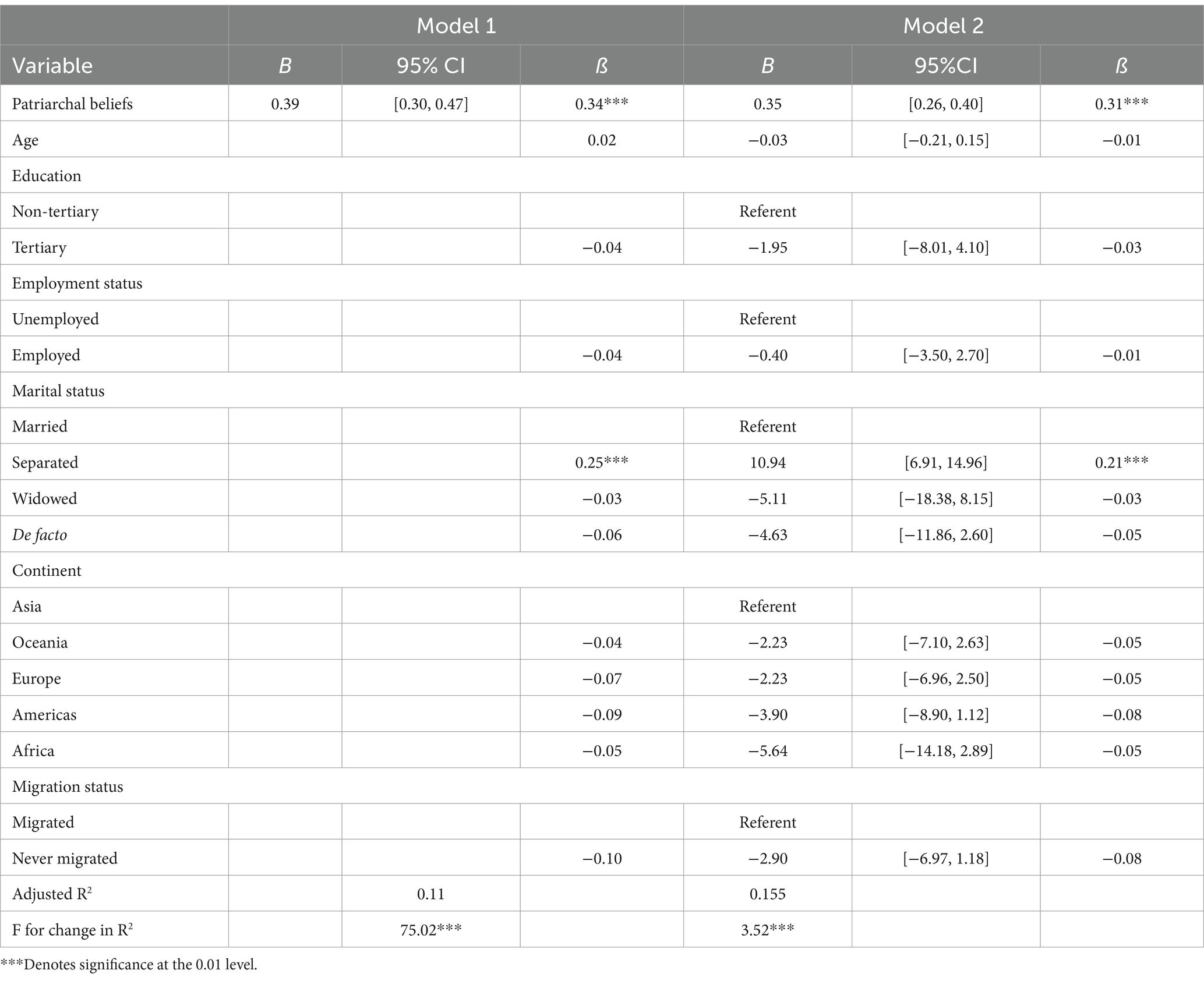

Table 1 depicts the socio-demographic characteristics of the 64,607 and 62,716 ever married females who consented to respond to the domestic violence module of NFHS-3 and 4. The sample in both the rounds was comparable in terms of age distribution, region of country they belong to, wealth status, religion, parity, and duration of cohabitation after marriage. However, a higher number of respondents were educated in round 4 (54.2%), while non-educated group was prevalent as per the 3rd round (47.2%). Most of the respondents from round 4 were economically empowered (55.8%). Nearly four-fifth of the them had witnessed parental violence, and more than half were experiencing partners controlling behavior. Age of marriage of the respondents had shifted primarily from < 18 Years in round 3 to > 18 years in round 4.

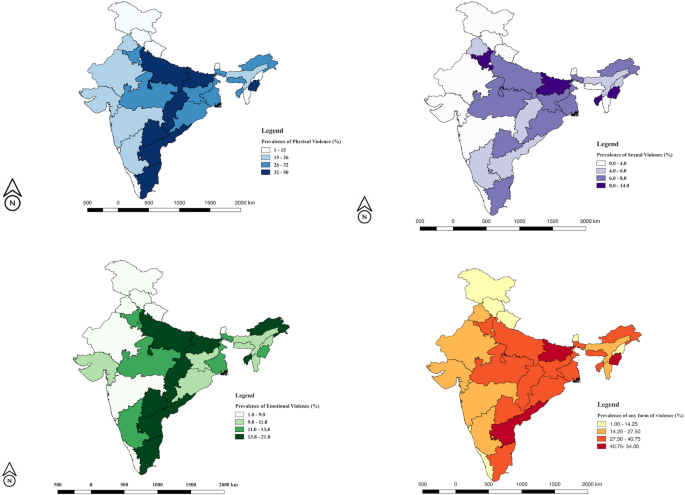

Physical violence was the most common form of IPV (29.2%) experienced by the respondents. Over all, the proportion of the respondents who ever experienced physical form of IPV (Table 2 ) decreased from round 3 to round 4 (Relative change of − 14.9%). The physical form of IPV continues to be reported from the highest age groups, uneducated, poorest respondents from Eastern part of India, who were mostly multiparous, married at a young age and were economically empowered. Also, the weighted prevalence was high among the respondents whose partners either had a controlling behavior, or were addicted to alcohol. Only southern region of the country depicted a relative increase in prevalence of IPV in round 4 compared to round 3. State-wise, maximum prevalence was observed in Manipur (50%), while minimum prevalence was seen in Sikkim (1%) as per the NFHS Round 4 (Supplementary Table 1 ; Fig. 1 a). Multiple binary logistic regression analysis, depicted all the variables depicted in Table 1 as the significant predictor of physical form of domestic violence as per NFHS-4 datasets except older age groups, and less years of education.

a - d State-wise variations in the prevalence of physical, sexual, emotional and anyform of IPV among the married women as per the fourth round of the National Family Health Survey, India (2015–16)

Sexual form depicted minimum weighted prevalence amongst all types of IPV, and decreased (− 30.2%), from round 3 (9.6%) to round 4 (6.7%) (Table 3 ). The weighted prevalence as per the round 4 of NFHS is maximum in the 25–34 years age group, uneducated, poorest respondents from Eastern part of the country who were married at a younger age, were multiparous, and economically empowered. State wise weighted prevalence of Sexual IPV ranged between (14% in Bihar and Manipur to 0% in Sikkim) (Supplementary Table 1 ; Fig. 1 a). Similar to physical form of IPV, weighted prevalence was more among the respondents, whose partners had a controlling behavior, or were consuming alcohol, and had increased in Southern region of the country. Binary logistic regression depicted all the independent variables as significant predictors of sexual IPV except age, less years of education of respondents and their partners, parity, more than 20 years of cohabitation, and age of marriage of the respondents.

Emotional violence was more common than sexual violence but less than the physical form with a national prevalence of around 13% (Table 4 ). The weighted prevalence was nearly similar in all age groups as per NFHS 4, but highest in uneducated, and poorest quintile of respondents belonging to the eastern region of India, who were multiparous and economically empowered similar to other forms of violence. State wise weighted prevalence of emotional IPV ranged between (21% in Tamil Nadu to 1% in Sikkim) (Supplementary Table 1 ; Fig. 1 c). More number of co-wives, early age of marriage, controlling behavior of partners, and alcohol also increased weighted prevalence of emotional form of IPV. Binary logistic regression depicted that there were higher odds of experiencing emotional violence when the respondents were young, uneducated, belong to the poorest quintile, and southern region of India, multiparity, history of witnessing parental violence, more duration of cohabitation after marriage, controlling behaviours of the partner, and alcohol consumptions.

The weighted prevalence of any type of IPV ever faced by a woman decreased from 38.9% in third round to 32.8% in the fourth round. Maximum relative % decrease was seen in youngest age group, uneducated (− 10.9%), middle quintile (− 17.4%), Northern region (− 30.9%), nulliparous female respondents (− 26.4%), amongst those who did not witness any kind of parental violence (− 22.7%), who were coinhabiting for less than 5 years (− 21.5%), and were not living with any co-wives of their partners (− 16.5%). State wise weighted prevalence of any type of IPV ranged between (56% in Manipur to 2% in Sikkim) (Supplementary Table 1 ; Fig. 1 d). Significant predictors of any type of IPV as per the fourth round of NFHS are depicted in Table 5 . It was seen that economic empowerment of women, and age at first marriage could not predict exposure to IPV among the respondents.

There are some major findings of our study. First, there was a decrease in any form of IPV from NFHS round 3 to 4. Maximum reduction was observed in sexual IPV, followed by physical and emotional form. But still, around 7 out of 100 women reported history of sexual IPV. Second, IPV was reported more amongst the poorest and uneducated respondents. Third, contrary to our belief, urban areas depicted a higher chance of IPV. Fourth, we observed that certain factors like economic empowerment that were considered to act as a shield against IPV were of no help, but increased the probability of violence episodes. Lastly, we observed that most of the factors predicting the exposure to different kinds of violence were same. Decrease in IPV in NFHS-4 can be attributed to improvement in education and societal status, decrease in witnessing family violence, improved sense of gender equality, more awareness among women, improved community norms regarding domestic violence, and enforcement of the PWDVA after 2006 .

We observed that sexual IPV has depicted maximum decrease in India as per the two rounds, compared to other forms of IPV. Coerced sex as seen in sexual violence may result in sexual gratification on the part of the perpetrator, though its underlying purpose is to dominate the spouse through force. Also, such men feel that their actions are in accordance with the law as they are married the victim. However, sexual violence has a profound impact on physical and mental health because it also leads to physical injuries, a plethora of acute and chronic sexual and reproductive health problems [ 36 ]. To our dismay, it is a neglected area of research, the available data is scanty and fragmented as many women do not report sexual violence due to emotional embarrassment, or fear of being blamed. Also, only a very small proportion of women seek medical services for immediate problems related to sexual violence.

We observed a higher incidence of IPV among the poorest and uneducated respondents [ 37 ]. It is well documented that people from the under-privileged sections of the society are at increased risk of IPV [ 38 ]. Low economic status also has many associated stressors like economic stress, that are linked with marital conflicts [ 39 , 40 ]. According to the family stress model , lack of money or increased expenditure, induces frequent emotional outbursts and, conflicts among family members, including conflict between spouses [ 40 ]. Also, the women who is a victim to IPV, experience several negative outcomes like decreased economic productivity in addition to poor psychosomatic health as a vicious cycle.

We also observed a higher chance of having IPV in urban areas compared to rural areas. On bivariable logistic regression, there was higher chances of violence in rural areas, but this was reversed during the adjusted analysis. This contradictory pattern has also been noted in Bolivia, Haiti and Zambia, where women living in urban areas were more likely to report partner violence than women living in rural areas [ 41 ]. There are several factors that can explain such trend. Some men may find economically independent and educated female partners threatening. There is evidence that increase in women’s empowerment, abates men’s feelings of control over their spouses that leads to increased violence to exert their control and power [ 42 ]. Further, urban areas provide women with greater opportunities to report violence, contrary to the rural areas, where access to appropriate health care services including the counselling of the victims and management of IPV injuries is more limited [ 43 ]. Also, interpersonal relations are more compromised and strenuous in urban areas due to pressures of urban living, such as poverty, engagement in certain types of occupation, poor quality living conditions and the physical configuration of urban areas, which can lead to greater incidence of violence [ 44 ]. On the other hand, rural areas in India depict better social support compared to the urban [ 45 ]. However, some studies depict higher chances of IPV in rural areas and it attributed to patriarchal ideology, and traditional gender roles [ 46 ]. Women with more children tend to be a higher risk of IPV similar to our observations and it was more in urban areas compared to rural [ 46 ]. This may be indirectly linked to increased economic stress in families with more children.

Economic empowerment was not seen to be protective against IPV in our study. Similar observations were reported in various sub-national analysis from India and abroad [ 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ]. A longitudinal study of married women in Bangalore found that women who were unemployed but began employment subsequently had an 80% higher odds of violence, as compared to women who maintained their unemployed status [ 49 ]. Another study for a violence against women and girls reduction programme in India found that women who earned and controlled their own income were more likely to report violence experienced both at home [ 50 ]. One of the study also reports that till the time women’s income is less than her male spouse, empowerment is protective, and as the scenario changes with increase in her income, violence increase [ 51 ]. This increase in risk is related to ‘male backlash’ – as women gain more economic autonomy, men feel that their authority is being challenged and thus increase their use of violence as a means of reasserting their control [ 49 , 51 ]. It is hypothesized that in less developed settings, where women are not independent economically, their entry into work may initially increase marital tensions and risk of IPV, but the tussle gradually settles down as their male counterparts start recognizing the benefits of additional household income [ 52 ]. This theory is supported by cross-country analysis [ 53 ]. However, the relationship between economic empowerment and violence is not universally the same. Studies from our neighbouring countries like Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh depicted that the lifetime experience of IPV was high among the women with low empowerment [ 54 , 55 ]. Another study from Jordan reported that the women who can take decision independently in the household matters and income related issues are less likely to suffer from IPV [ 56 ]. The relationship between women empowerment and violence is complex, and hence further investigation is required to understand which factors drive such findings in Indian context.

As noted, acceptability of IPV remains high in India, and in fact have seen little changes between the last two rounds of NFHS [ 10 ]. Furthermore, the impact of parental violence on their children was highlighted through our study. Families where parental violence was witnessed, or husbands exerted a controlling behavior depicted a higher risk of IPV [ 57 ]. Unfortunately, each form of family violence begets interrelated forms of violence, and the “cycle of abuse” is often continued from exposed children into their adult relationships, and finally to the care of the elderly [ 57 ]. Mothers should encourage daughters to engage in a relationship with responsible men, while fathers’ communication should be directed towards young boys and aimed at inculcating values against dominant traditional masculinity, objectifying girls and chauvinist values.

There are certain strength and limitations of this study that should be acknowledged. The study was done using the national data collected following a robust methodology that increases the reliability of data generated. The use of complex weighted analytical design to obtain results allow us to generalize the results for projection at national level. However, the use of secondary data in itself is a limitation of the study, as the results will contain only the predetermined variables. There are a lot more number of variables apart from those included in the NFHS that affect IPV and its effects on a female experiencing it. Lastly, if the data is self-reported, the overall true prevalence of the violence may actually be higher than estimated, owing to various reasons discussed earlier in the manuscript.

There are a few policy implications of this study. Given a high prevalence of physical and mental health problems in women exposed to IPV, there is a potential for cognitive behavioral interventions to improve women’s mental health. Advocacy related to IPV is necessary. It should be implemented through a multifaceted approach in the form of legal, housing and financial advices. Awareness should be aimed about the access to existing community resources such as shelters, hostels and psychological interventions and provision of legal support. Informal counselling is another intervention that may be offered to women [ 58 ]. However evidence from a Cochrane review regarding the effect of advocacy for women exposed to IPV has been equivocal [ 58 ]. Therefore, the future research should try to look for the best options that can be offered to such women who are seeking help. Also, the role of screening for IPV has been debated over recent years. The routine screening of women for IPV in health settings, in the absence of structured intervention, was to have limited impact upon health outcomes and re-exposure to violence and hence not recommended [ 18 , 59 ]. However, some other studies from different study setting are in favor of offering screening services, and hence this also needs to be evaluated in different socio-cultural settings [ 60 ]. Finally, exposure to violence has significant impacts. Longitudinal studies are needed to understand the temporal relationship between recent IPV and different health issues, while considering the differential effects of recent versus past exposure to IPV [ 60 ]. Healthcare providers and IPV organizations should be aware of the bidirectional relationship between recent IPV and psycho-somatic symptoms. This will also improve our understanding of the immediate and long-term health needs of women exposed to IPV.

We observed different patterns of IPV and their risk factors through this comprehensive assessment, and concluded that much needs to done in this regards. Our concepts of decreasing IPV through empowerment of women has been challenged, and so it the urban-rural divide. We must understand that in order to decrease IPV, we need to think beyond women, and focus more on challenges emerging from increase in women’s empowerment, and increase in urbanization. Interventions to empower women must work with couple as a unit, and at the community-level, to address equal job opportunities, and gender specific roles.

Availability of data and materials

This study analyses a nationally representative survey database which is available freely in public domain.

Krug E, Mercy J, Dahlberg L, Anthony B. World report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1083–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women Taking action and generating evidence. World Health Organization; 2010. p. 102. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/violence/9789241564007_eng.pdf . Accessed 19 Nov 2020

Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Understanding and addressing violence against women. World Health Organization; 2010. p. 12. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77434/1/WHO_RHR_12.37_eng.pdf . Accessed 29 Sept 2020

Government Of India. National Family Health Survey. 2017. http://rchiips.org/nfhs/ . Accessed 26 Nov 2020.

Crockett C, Brandl B, Dabby FC. Survivors in the margins: the invisibility of violence against older women. J Elder Abus Negl. 2015;27(4-5):291–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2015.1090361 .

Article Google Scholar

Devries KM, Mak JYT, García-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science (80- ). 2013;340:1527–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar