- Countries Who Spend the Most Time Doing Homework

Homework is an important aspect of the education system and is often dreaded by the majority of students all over the world. Although many teachers and educational scholars believe homework improves education performance, many critics and students disagree and believe there is no correlation between homework and improving test scores.

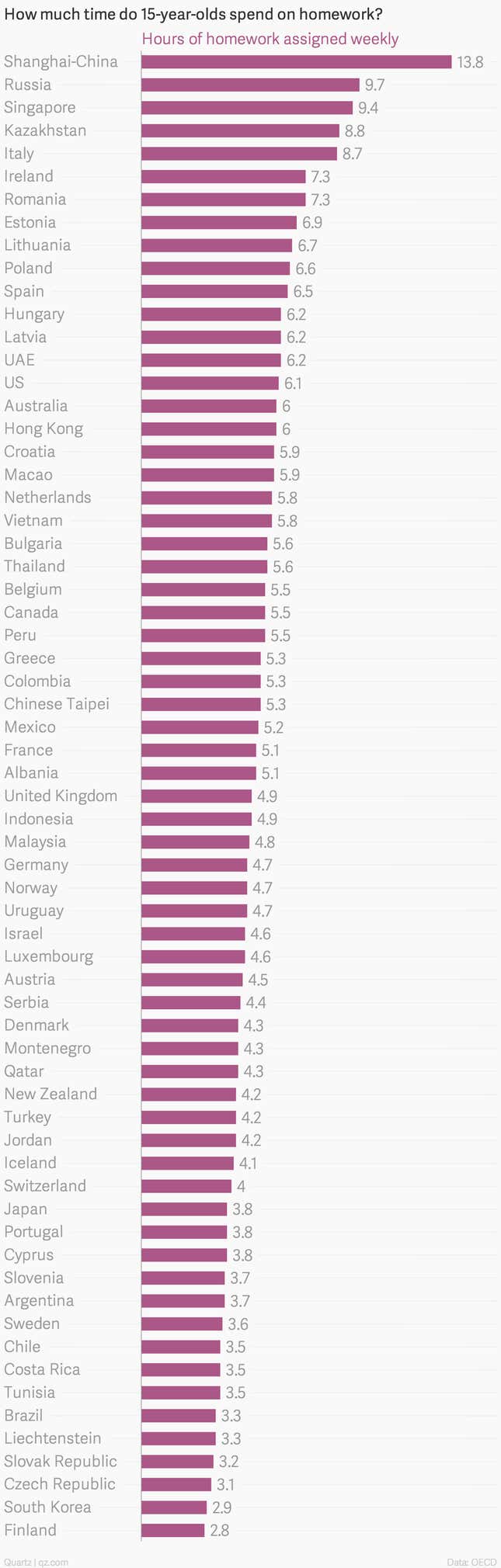

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is an intergovernmental organization. With headquarters in Paris, the organization was formed for the purpose of stimulating global trade and economic progress among member states. In 2009, the OECD conducted a detailed study to establish the number of hours allocated for doing homework by students around the world and conducted the research in 38 member countries. The test subjects for the study were 15 year old high school students in countries that used PISA exams in their education systems. The results showed that in Shanghai, China the students had the highest number of hours of homework with 13.8 hours per week. Russia followed, where students had an average of 9.7 hours of homework per week. Finland had the least amount of homework hours with 2.8 hours per week, followed closely by South Korea with 2.9 hours. Among all the countries tested, the average homework time was 4.9 hours per week.

Interpretation of the data

Although students from Finland spent the least amount of hours on their homework per week, they performed relatively well on tests which discredits the notion of correlation between the number of hours spent on homework with exam performance. Shanghai teenagers who spent the highest number of hours doing their homework also produced excellent performances in the school tests, while students from some regions such as Macao, Japan, and Singapore increased the score by 17 points per additional hour of homework. The data showed a close relation between the economic backgrounds of students and the number of hours they invested in their homework. Students from affluent backgrounds spent fewer hours doing homework when compared to their less privileged counterparts, most likely due to access to private tutors and homeschooling. In some countries such as Singapore, students from wealthy families invested more time doing their homework than less privileged students and received better results in exams.

Decline in number of hours

Subsequent studies conducted by the OECD in 2012 showed a decrease in the average number hours per week spent by students. Slovakia displayed a drop of four hours per week while Russia declined three hours per week. A few countries including the United States showed no change. The dramatic decline of hours spent doing homework has been attributed to teenager’s increased use of the internet and social media platforms.

More in Society

Countries With Zero Income Tax For Digital Nomads

The World's 10 Most Overcrowded Prison Systems

Manichaeism: The Religion that Went Extinct

The Philosophical Approach to Skepticism

How Philsophy Can Help With Your Life

3 Interesting Philosophical Questions About Time

What Is The Antinatalism Movement?

The Controversial Philosophy Of Hannah Arendt

- Privacy Policy

- Letters to the Editor

- Advertise with us

7 Facts About the Education System in Mexico

Did you know that Mexico has one of the most complex education systems globally? There are many different levels of schooling, and it can be pretty confusing to understand it all. Here are seven facts about the education system in Mexico that will help you make sense of it all:

- Only 45% Of Students Finish Secondary School

While the coursework can be overwhelming, having an expert write my paper for me has always been a lifesaver.

In Mexico, students must complete primary school before moving on to secondary school. However, only 45% of Mexican students finish secondary school. This is partly because many families cannot afford to send their children to school for the entire time.

There are also a lot of dropouts at the secondary level because the coursework is very challenging. Students who don’t have someone to help them with their homework often struggle and eventually give up.

- Mexico spends less on education than any other OECD country

Despite being one of the largest economies in Latin America, Mexico spends less money per student than any other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country.

This lack of investment means that many schools are in poor condition and don’t have enough resources for students. As a result, students often have to drop out of school or go to private schools, which are much more expensive.

- Only 60% Of Mexicans Are Literate

While the education system in Mexico has improved over the years, there is still a long way to go. According to recent data, only 60% of Mexicans are literate. This number is even lower for indigenous people, who make up about 21% of the population.

One reason why literacy rates are so low is that many families can’t afford to send their children to school. In addition, some parents don’t think education is essential, or they don’t understand the importance of literacy.

- Mexican Schools Don’t Teach Evolution

Despite being a developed country, Mexico does not require its schools to teach evolution. It’s estimated that less than half of all Mexicans believe in evolution. This is likely due to the influence of the Catholic Church, which opposes the teaching of evolution in schools.

This lack of knowledge about evolution can be dangerous because people don’t understand the scientific evidence for things like climate change. As a result, they are more likely to disbelieve scientists and think that environmental problems are exaggerated.

- The Majority Of Students Attend Public Schools

In Mexico, the majority of students attend public schools. However, these schools are often underfunded and in poor condition. As a result, many families send their children to private schools, which are much more expensive.

Private schools often have better resources and teachers, but most Mexican families are out of reach. This means that many children from low-income families don’t get the education they deserve.

- There Are Three Main Levels Of Schooling In Mexico

The education system in Mexico is divided into three main levels: primary, secondary, and tertiary.

Primary school is compulsory for all children, and it lasts for six years. Secondary school lasts for four years, and it’s not compulsory. Tertiary education includes both university and technical schools.

- Mexico Has A Lot Of Universities

There are over 1800 universities in Mexico, making it one of the most popular destinations for international students. While admission requirements vary from school to school, most universities require an admission essay and a language proficiency test such as TOEFL or IELTS.

In addition, many schools offer conditional admission for students who meet all other admission requirements but need to improve their language skills. Finding the right university can be a daunting task with so many options to choose from. However, with the right admission essay writing service provider, it’s easier to narrow down your options and find the perfect school for your needs. Going through a review of the best service providers in the market can help you find the best option.

As you can see, there are a lot of issues with the education system in Mexico. While there have been some improvements over the years, there is still a long way to go. Hopefully, with more investment and reform, the education system in Mexico will provide all students with the opportunity to get a quality education.

Mexico Daily Post

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

What do young voters in mexico want, ten women who changed the sports industry in mexico forever, three civilians were killed by a roadway bomb in michoacán.

- Topics ›

- Elementary schools in the U.S. ›

The Countries Where Kids Do The Most Homework

Does your kid complain about endless hours of homework? If you live in Italy , those complaints could reach fever-pitch! According to research conducted by the OECD, 15-year old children in Italy have to contend with nearly 9 hours of homework per week - more than anywhere else in the world. Irish children have the second highest after-school workload - just over 7 hours each week. In the United States , about 6.1 hours of a 15-year old's week are sacrificed for the sake of homework. In Asia, children have very little to complain about. Japanese students have to deal with 3.8 hours of homework per week on average while in South Korea, it's just 2.9 hours.

Description

This chart shows hours of homework per week in selected countries.

Can I integrate infographics into my blog or website?

Yes, Statista allows the easy integration of many infographics on other websites. Simply copy the HTML code that is shown for the relevant statistic in order to integrate it. Our standard is 660 pixels, but you can customize how the statistic is displayed to suit your site by setting the width and the display size. Please note that the code must be integrated into the HTML code (not only the text) for WordPress pages and other CMS sites.

Infographic Newsletter

Statista offers daily infographics about trending topics, covering: Economy & Finance , Politics & Society , Tech & Media , Health & Environment , Consumer , Sports and many more.

Related Infographics

Movie industry, do oscar winners also rule the box office, the countries that are safe & unsafe for women, how leading e-commerce platforms stack up to amazon, water industry, how popular is bottled water around the world, munich security conference 2024, extreme weather, russia & cyber attacks top fears list, tourist accommodation, are short-term rentals more popular than hotels, trust in government, are politicians trustworthy, tourism & hospitality, the most important markets for the maldives tourism industry, who sells the most weapons, how europeans deal with cookie controls, germany is europe's solar energy front-runner, 2024 predictions, what will happen in 2024.

- Who may use the "Chart of the Day"? The Statista "Chart of the Day", made available under the Creative Commons License CC BY-ND 3.0, may be used and displayed without charge by all commercial and non-commercial websites. Use is, however, only permitted with proper attribution to Statista. When publishing one of these graphics, please include a backlink to the respective infographic URL. More Information

- Which topics are covered by the "Chart of the Day"? The Statista "Chart of the Day" currently focuses on two sectors: "Media and Technology", updated daily and featuring the latest statistics from the media, internet, telecommunications and consumer electronics industries; and "Economy and Society", which current data from the United States and around the world relating to economic and political issues as well as sports and entertainment.

- Does Statista also create infographics in a customized design? For individual content and infographics in your Corporate Design, please visit our agency website www.statista.design

Any more questions?

Get in touch with us quickly and easily. we are happy to help.

Feel free to contact us anytime using our contact form or visit our FAQ page .

Statista Content & Design

Need infographics, animated videos, presentations, data research or social media charts?

More Information

The Statista Infographic Newsletter

Receive a new up-to-date issue every day for free.

- Our infographics team prepares current information in a clear and understandable format

- Relevant facts covering media, economy, e-commerce, and FMCG topics

- Use our newsletter overview to manage the topics that you have subscribed to

- The A.V. Club

- The Takeout

- The Inventory

Support Quartz

Fund next-gen business journalism with $10 a month

Free Newsletters

Students in these countries spend the most time doing homework

Teens in Shanghai spend 14 hours a week on homework, while students in Finland spend only three. And although there are some educational theorists who argue for reducing or abolishing homework, more homework seems to be helping students with test scores.

That’s according to a new report on data the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development collected from countries and regions that participate in a standardized test to measure academic achievement for 15-year-olds, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

(It should be noted that while Shanghai scored highest on the 2012 PISA mathematics test, Shanghai is not representative of all of mainland China, and the city received criticism for only testing a subset of 15-year-olds to skew scores higher.)

While there are likely many other factors that contribute to student success, homework assigned can be an indicator of PISA test scores for individuals and individual schools, the report notes. In the individual schools in some regions—Hong Kong, Japan, Macao, and Singapore—that earned the highest math scores (pdf, pg. 5) in 2012, students saw an increase of 17 score points or more per extra hour of homework.

The report also notes, however, that while individuals may benefit from homework, a school system’s overall performance relies more on other factors, such as instructional quality and how schools are organized.

On average, teachers assign 15-year-olds around world about five hours of homework each week. But those average hours don’t necessarily tell the whole story. Across countries, students spending less time on homework aren’t necessarily studying less—in South Korea, for example, 15-year-olds spend about three hours on homework a week, but they spend an additional 1.4 hours per week with a personal tutor, and 3.6 hours in after-school classes , well above the OECD average for both, according to the OECD survey.

Within countries, the amount of time students spend on homework varies based on family income: Economically advantaged students spend an average of 1.6 hours more on homework per week than economically disadvantaged students. This might be because wealthier students are likely have the resources for a quiet place to study at home, and may get more encouragement and emphasis on their studies from parents, writes Marilyn Achiron , editor for OECD’s Directorate for Education and Skills.

It should also be noted that this list only includes countries that take the PISA exam, which mostly consists of OECD member countries, and it also includes countries that are OECD partners with “enhanced engagement,” such as parts of China and Russia.

📬 Sign up for the Daily Brief

Our free, fast, and fun briefing on the global economy, delivered every weekday morning.

School system Mexico – How are Mexicans educated?

To understand the education standards in Mexico, it is important to know how the school system works in Mexico. In the following we provide an overview of the education system in Mexico.

Kindergarten

The pre-school in Mexico starts at the age of three, when the children enter in the kindergarten (which is obligatory). The kindergarten is divided into three levels; the so-called “children 1”, “children 2” and “children 3”. During kindergarten, the children already have a fixed timetable, learn how to read & write and the numbers until 1,000 and need to do homework.

School-system

The school system in Mexico is divided into 4 different levels. First, pupuls attend primary school for 6 years (Primaria), following 3 years secondary school (Secundaria) and then another 3 years in high school (Preparatoria), among Mexicans also known as “Prepa”, “Bachillerato” or “Bachi”.

The Prepa prepares for a job or the university. The Bachillerato enabels students to apply for Universities. The courses have an average duration of 5 years.

The state schools have no tution fees. Typical for them is the school uniform, which should prevent students from getting better clothes than their classmates. However, almost all Mexicans who can afford it, send their children to private schools, because the teachers are usually better educated and they have larger supply of materials.

However, teachers usually do not earn much better than at the state schools, but enjoz a more pleasant working atmosphere (smaller class associations, more discipline).

School subjects

The compulsory subjects are usually Spanish, mathematics, physics, chemistry, sports, English, biology, history, literature and often sociology, psychology and logic. But that can vary from school to school.

Doctrine of Law and Order

In the north of Mexico, a few years ago, the subject Cultura de la Legalidad was introduced, the doctrine of law and order. The children are supposed to learn what law and order means. This subject was introduced for criminal prevention.

A school day usually lasts from 7 to 12 or 14 o’clock, but also afternoon or evening classes are common.

Grading System

The grading is from 1 to 10, with 1 being the worst and 10 being the best grade.

The scores in Mexico range from a 10 (very good) to a 5:

- 9-10 – Excellent

- 8-9 – Very good

- 7-8 – Good

- 6-7 – Enough

- 5-6 – Insufficient

- 0-5 – (Unused)

On average, at least a 6 must be achieved for each subject to be moved.

Do you have further questions? We are happy to advise you.

Querétaro | Mexiko Stadt | Puebla | Monterrey | Stuttgart | Greenville | Shanghai

Join our mailing your email:.

Email address:

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

Cookie and Privacy Settings

We may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

Dispatch: Mexico’s School Closures Are Increasing Inequality

Create an FP account to save articles to read later and in the FP mobile app.

ALREADY AN FP SUBSCRIBER? LOGIN

- World Brief

- Editors’ Picks

- Africa Brief

- China Brief

- Latin America Brief

- South Asia Brief

- Situation Report

- Flash Points

- War in Ukraine

- Israel and Hamas

- U.S.-China competition

- Biden's foreign policy

- Trade and economics

- Artificial intelligence

- Asia & the Pacific

- Middle East & Africa

The Return of Great Powers

Ones and tooze, foreign policy live.

Winter 2024 Issue

Print Archive

FP Analytics

- In-depth Special Reports

- Issue Briefs

- Power Maps and Interactive Microsites

- FP Simulations & PeaceGames

- Graphics Database

Her Power 2024

The atlantic & pacific forum, principles of humanity under pressure, optimizing global health, fp global health forum 2024.

By submitting your email, you agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use and to receive email correspondence from us. You may opt out at any time.

Your guide to the most important world stories of the day

Essential analysis of the stories shaping geopolitics on the continent

The latest news, analysis, and data from the country each week

Weekly update on what’s driving U.S. national security policy

Evening roundup with our editors’ favorite stories of the day

One-stop digest of politics, economics, and culture

Weekly update on developments in India and its neighbors

A curated selection of our very best long reads

Mexico’s School Closures Are Increasing Inequality

With schools shut for over a year, limited access to technology is exacerbating the education gap, leaving indigenous communities behind..

CELTÚN, Mexico—As Mary Carmen Che Chi parked her car next to the small school building on a Monday morning in May, the few children around chatted impatiently before lining up for the routine hand wash between their two classrooms. They had been waiting for two long weeks to see her and her colleague José Manuel Cen Kauil.

The two teachers’ work was abruptly halted in March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit Mexico. “All of a sudden they told us, ‘Tomorrow just go and tell the children that you’re not coming back until further notice,’” Che Chi recalled.

Schools closed all over the country, and the federal government rolled out a program called “Learn at Home,” offering classes on television and online. But for teachers like Che Chi and Cen Kauil, this wasn’t an option. The Indigenous community where they both work, Celtún, is located in the middle of the Mexican state of Yucatán and it lacks access to the required tools for virtual learning. “It’s functional for urban areas, but for remote communities without signal it’s hard,” Cen Kauil said.

According to the United Nations, almost 500 million children around the world have been excluded from the remote learning solutions that replaced their normal schooling due to the pandemic. For those lacking the resources and necessary technologies, it has become impossible to keep up with classes. In Mexico, the number of children between 6 and 14 years old who are not receiving any formal education has increased by 74 percent compared to 2015, according to government figures . The hardest-hit communities are those without access to the internet and other technologies, which is the case for around half of Mexico’s rural population, due to both poverty and lack of internet infrastructure.

Celtún has no cellphone service and national television broadcasts are unavailable. The teachers’ first issue was figuring out how to communicate with their students at all.

Headmaster José Manuel Cen Kauil teaches a small class of students ranging from ages 9 to 11 at the Ignacio Ramírez Calzada primary school in Celtún on May 3

Mary Carmen Che Chi teaches a small class of 6- to 8-year-olds at the Ignacio Ramírez Calzada primary school in Celtún on May 3.

“We worried a lot about what to do, and the parents asked us the same, saying the kids needed something to do. But we weren’t authorized to go there,” said Cen Kauil, who lives in Valladolid, about 20 miles from Celtún.

In the beginning, no one without an ID indicating that they lived nearby was allowed to enter Celtún and community members could leave only for emergencies. The teachers decided to use the only means of communication available at the time and sent instructions about books to read via the community police’s radio receiver, asking the leader of the parents’ association to spread the word.

“We had no idea whether they did the exercises or if they were at all productive,” Cen Kauil said, adding that the radio only works when there’s electricity. “When it’s windy or rainy there might be a blackout for two or three days, but it was all we had.”

By summer, community officials finally allowed them into the area once a month to drop off and pick up photocopies of worksheets, but without ever seeing their students. In September 2020, they were permitted to begin meeting with their students for one hour every two weeks to explain the exercises, although the schools officially remained closed. During these short encounters, they review what the students have worked on and hand out new assignments.

Since the pandemic started, this single hour every two weeks is the only interaction the students have with their teachers.

Instead of their normal multigrade full-day class with around 15 to 20 students each, they now split up into small groups of about five to reduce the risk of infections. Since the pandemic started, this single hour every two weeks is the only interaction the students have with their teachers. “It’s affecting them emotionally. The first day we came back the children wanted to come close and hug you, and we had to say that they couldn’t,” Che Chi said.

Fifth-grader Rodrigo Tuz Díaz lives just a few hundred yards away from the concrete building where he just received new homework. He used to be in school five days a week from 7 a.m. until 3 p.m. and received a meal while there.

“I miss them a lot and want them to come and hold classes like before,” he said of his teachers, picking up a small chicken from the ground. He tries to complete the activities in his notebook, but it’s not the same. “I like how my teacher explains the exercises, because he helps me to finish them all.”

Sometimes his older sister helps him, or his dad does when he comes back from working in the fields, where the family grows maize, beans, and other crops. His father, Orlando Tuz Tuz, has felt a double hardship of the pandemic, with work opportunities disappearing and his children cut off from school. “It’s complicated, because the kids fall behind when there’s no classes,” he said.

Prolonged school closures also increase the risks of long-term consequences, such as a rise in dropout rates, as some children tend not to come back when schools finally reopen. This risk gets even higher during an economic crisis, when the pressure on children to contribute to the family income grows.

Che Chi visits with the parents at the home of her student Leisy Liliana Pool Cen in Celtún on May 4. She meets with parents every two weeks to distribute learning materials for the children, as well as to support and coach them through remote learning without access to the internet while schools remain closed.

As parents have been forced to take on more responsibility for their children’s learning, yet another inequality is playing out. Many have only spent a few years in school themselves and some can hardly read or write, making it hard to help their children. “Sometimes I can learn at the same time, but if I don’t understand it I can’t help him, which feels terrible,” Tuz Tuz said.

More than 15 percent of Mexicans haven’t finished elementary school, according to the latest available numbers . Many parents in Celtún speak nothing but Maya and about half of the children don’t become bilingual until starting school, according to Che Chi.

Although over 7.3 million Mexicans—some 6 percent of the population—speak a language other than Spanish as their mother tongue , the federal “Learn at Home” program was rolled out mainly in Spanish and, Cen Kauil said, not with Indigenous students in mind. To overcome the barriers, they put the federal learning materials aside, creating their own substitutes.

Enrique Cetina, a school supervisor in the area, feels it’s been hard to get federal authorities to understand the challenges of rural education—both in terms of students’ learning needs and the financial burdens placed on teachers. “Personally, I feel frustrated and disappointed,” he said. “Almost all the expenses for printing land on the teachers, because the parents don’t have the money.”

In 2018, 8 out of 10 inhabitants of Yucatán were considered to be living in poverty or a vulnerable situation. In general, around 70 percent of Mexico’s Indigenous population live in poverty, compared to 39 percent of the non-Indigenous population. Likewise, 28 percent of the Indigenous population live in extreme poverty, while the proportion of non-Indigenous Mexicans in extreme poverty is just 5 percent.

Historic Droughts Drive Up Prices in Mexico and Brazil

Historic dry spells are straining life and business in the two countries, where presidents are aloof to climate change.

Mexico’s López Obrador Is Pulling an Erdogan on Biden

By reducing U.S.-Mexican relations to migration, Biden is letting himself be played—and ignoring a crisis south of the border.

Mexico Is America’s Answer to China’s Belt and Road

Growing economic integration with Latin America could help the United States avoid the fate of an aging China.

The inequalities are as present when it comes to education. In Mexico’s Indigenous communities the illiteracy rate is 23 percent , compared to 4 percent in the rest of the population. The pandemic seems to be further exacerbating these differences.

A few blocks away, Rodrigo’s classmate Grisel Hau Poot played with a friend while her mother made tortillas over a small fire. Her mom, Argelia Poot Poot, is busy from early morning preparing food for her husband, washing, cleaning, and taking care of the kids. “We need to take an hour to help them, but when there’s something we don’t understand, how are we supposed to help them then?” she asked while kneading the dough.

In Mexico’s Indigenous communities the illiteracy rate is 23 percent , compared to 4 percent in the rest of the population. The pandemic seems to be further exacerbating these differences.

Since realizing parents also need help, the teachers have sometimes held small workshops or visited them to explain the exercises. “It gives them a moment to vent,” Che Chi said. “I love when a mother tells me, ‘Teacher, I tried this, but I’m not sure if it’s right.’ It feels good when they try, because that’s when we start seeing results.”

Further west in Yucatán, Yahaira Ek Sosa and her sister Karla Ek Sosa work with children who need extra support. Some have developmental or physical disorders, while others have fallen behind or dropped out because of family issues or traditional values encouraging girls to stay home rather than going to school.

Most people here live off their land and work as day laborers when they can. As the pandemic eliminated many of those jobs and resources tightened, the sisters had to come up with new strategies.

“I found out that parents who used to have a cellphone sold it to have something to eat. My students in Kancab don’t have any means of communication and in Peto they don’t have money to print the worksheets,” Karla Ek Sosa said.

Students have also told her they sometimes couldn’t finish their homework because they’re left alone without anyone to help when parents are working, or because a family member died.

Yahaira Ek Sosa and Karla Ek Sosa, sisters and elementary school teachers, sit in the “ escuelita móvil ” motorcycle taxi as they travel to visit their students during the coronavirus pandemic in Akil, Yucatán state, Mexico, on May 5.

After last summer, the sisters decided to create a mobile school. Starting their day in the village of Akil, they hire a motorcycle taxi and transform it with decorations and colorful collages to then visit the six villages where their students live. “The idea of using a motorcycle taxi has worked to get the attention of the children, despite all of the social and economic problems they are facing,” Yahaira Ek Sosa explained.

When the teachers arrived at the house of 12-year-old Abigail Xool Sánchez, she greeted them with a big smile, dressed up in a patterned black-and-white dress and pink bows in her hair. Karla Ek Sosa gave her a matching pink face mask and set out scissors and glue, along with photocopies of exercises. “We’re going to cut out the letters you see here, in the same order,” she explained.

Xool Sánchez’s eyes followed her teacher’s finger pointing at different letters as her grandmother María de los Ángeles Quetz Chan, whom she calls “mom,” watched—trying to remember the tasks she would be helping her grandchild with until the next visit.

“I want to work as a cook like my mom,” Xool Sánchez said, grabbing the scissors and starting to cut out the letters. She has a developmental disability and the visits are important for her, Quetz Chan said “It’s not like going to school, because then they come home having learned things already,” she said. “Now if you don’t push them to learn, they don’t.”

Although some teachers have been dropping off exercises for studying at home by meeting their students once every two weeks instead of giving instructions via a screen, schools in Mexico have officially been closed continuously since the pandemic started. Since this June, attempts to reopen schools have been made in various states as COVID-19 cases had decreased. But after an optimistic outlook in Yucatán in May, the spread of the virus increased here again and reopening has been delayed. When the day comes, the children who haven’t had access to the distance education offerings are likely to be the ones who’ve fallen furthest behind.

As Rodrigo Tuz Díaz’s mother prepared lunch, he and his father waited in the backyard. “I think the government should let the schools open so the children can study better,” Orlando Tuz Tuz said, watching his son sit down with his notebook. “Because many children stop going at all when the teachers just come every two weeks.”

Asa Welander is an independent journalist based in Mexico City, Mexico. Twitter: @aosita

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber? Log In .

Subscribe Subscribe

View Comments

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Not your account? Log out

Please follow our comment guidelines , stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username:

I agree to abide by FP’s comment guidelines . (Required)

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.

More from Foreign Policy

China is selectively bending history to suit its territorial ambitions.

Beijing’s unwillingness to let go of certain claims suggests there’s more at stake than reversing past losses.

The United States Has Less Leverage Over Israel Than You Think

A close look at the foundations of U.S. influence—and the lack of it.

Khamenei’s Strategy to Dominate the Middle East Will Outlive Him

Iran’s aging supreme leader is ensuring that any successor will stay the course.

America Has a Resilience Problem

The chair of the Federal Trade Commission makes the case for competition in an increasingly consolidated world.

‘Anyone Who Dares Call Us Nazis Will Be Reported’

Israel is a strategic liability for the united states, america has pressured israel before—and can do it again, don’t give up on unrwa, a family feud in the philippines has beijing and washington on edge, tv’s new ‘game of thrones’ is set in 17th-century japan, israel targets hezbollah in syria, lebanon, what in the world, washington wants in on the deep-sea mining game.

Sign up for World Brief

FP’s flagship evening newsletter guiding you through the most important world stories of the day, written by Alexandra Sharp . Delivered weekdays.

The Marionette

- January 24 Oklahoma lawmakers, educators concerned over ‘Libs of TikTok’ creator’s appointment to education committee

- January 24 Who is Chaya Raichik? Everything to know about the Libs of TikTok creator

- January 24 Dashcam video shows I-40 crash that sent 3 people, including OHP trooper, to hospital

Student perspective: online learning here vs. Mexico

Reporter Paola Zapata shares the differences she noticed in how Mexican schools are approaching online learning in the pandemic versus how HCP is teaching online

Photo by Julia M Cameron from Pexels

Schools across the globe have had to adapt to learning in a pandemic.

Paola Zapata , Reporter January 22, 2021

AT THE START OF COVID-19:

America wasn’t the only country that had to go on lockdown, many students all over the world had to start online classes, and it wasn’t easy. Many students and teachers had a rough time with this. Teachers and schools all over the world had to figure out another way for students to keep on learning. While HCP and Mexican students are both doing online school, Mexican students have it a little tougher.

HCP STUDENTS HAVE IT EASIER:

HCP students are far more privileged than Mexican students, as many students have laptops and internet at home, or have been provided with nece. Mexican schools had to improvise. The students in Mexico that do have the internet can use programs like WhatsApp, Schoology, Aula virtual, Gmail, Google Meet and Zoom. Mexican students without internet use workbooks and can watch a specific channel on TV that airs lessons throughout the day, although it is mainly elementary and middle school students who use these options.

SCHEDULES:

High school students in Mexico do have a schedule for their online classes, but it depends on if they have morning or afternoon classes. Morning classes are from 7:50 a.m. – 2:00 p.m. Afternoon classes are from 1:40 p.m. – 8:00 p.m. HCP students online have one schedule that runs from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. with scheduled breaks.

SIMILARITIES WITH UNIFORM:

HCP and Mexican schools do have some similarities, though. Both wear uniforms. The majority of Mexican schools have to wear a uniform. HCP students wear a green/white/black polo shirt, khaki/blue pants, khaki/blue/plaid skirt, belt, with options for sweatshirts and sweaters if the weather is cold. Mexican schools however, are more strict. Mexican boys wear dress pants, a white-collar shirt, a school vest, a school sweater, and white socks with black dress shoes. Mexican girls wear dress shirts, school vests, school sweaters, a knee-length skirts, white stockings, and black shoes.

NUMBER OF CLASSES:

Another similarity is that HCP and Mexican students both have six or seven classes. Although in-person HCP has 40 minute classes and Mexican schools have 50 minute classes. In most Mexican schools students are put into groups where the students stay in the classroom and the teachers travel from class to class to teach.

OPINIONS FROM MADAY GALLEGOS (MEXICAN STUDENT)

+ PAOLA ZAPATA (ME, HCP STUDENT):

How has school been online?

Maday Gallegos: “It’s easier to be in person. With online school it is tougher because you learn less. In person, you get to interact and process the information easier, but online it is harder to focus and pay attention.” (translated from Spanish)

Paola Zapata: “School online has been tough. It’s a lot! School online has stressed me out way more than school in person does. I got to use Edgenuity for the first semester and it was hard to keep up. I needed a ton of help and thankfully I was still able to email HCP teachers. My sister was also very helpful. The only good thing that comes out of online school is that I don’t have to leave my house.”

How has the day changed?

Maday Gallegos: “School in person was only a couple of hours a day, but online it seems like ALL day because I am constantly checking my phone to see if I have any assignments. The time I wake up has changed, too. I can wake up later than I usually did. With school online, sometimes I have to stay up till 2-3 a.m. doing homework.” (translated from Spanish)

Paola Zapata: “Since I did Edgenuity for the first semester I was able to wake up whenever I wanted. I messed up my sleeping schedule so much. I was going to sleep at 3-5 a.m. and waking up around noon. I was even able to come to Mexico for two months since we knew for sure that Edgenuity students wouldn’t return to school in person if the other students did. Now that I have changed the way I do online school, I do have to go to sleep earlier and wake up even earlier. School at the moment isn’t too stressful, and I’m honestly glad I’m not doing Edgenuity again. It is very hard to teach yourself.”

What is something you miss from in person school?

Maday Gallegos said: “Getting out of the house and seeing different people. I miss talking to friends in person and meeting new people. I also miss group work too.” (translated from Spanish)

Paola Zapata: “I miss having a schedule for the day. Some days I felt like a robot doing the same thing every day, but I miss having a schedule. I hate to admit it, but I do miss getting out of the house. I love my room so much, but it’s good to get out of the house and see people once in a while!”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Harding Charter Preparatory High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.

Hello! I am currently in 12th grade. My pronouns are she/they. I love to write about controversial topics and use my voice to speak up about any topic!...

Do you prefer winter or summer?

- Do you want to build a snowman? Because I do!

- I dream of relaxing in the summer sun, just lettin' off steam

View Results

- Polls Archive

- Maddie Greer on Long live Jillian Thomas

- Mx. Leenders on HCP ASMR, pt. 2

- Lori McNeal on Top 5 Holiday Horror Films

- Pao Z on Song review: ‘Vampire’ by Olivia Rodrigo

- Paola Zapata on It’s time to update prom traditions

Long live Jillian Thomas

Arts & Entertainment

Staff Christmas Playlist 2023

Formidable flavors at 23rd street spot

“Your job is easy”

L’echange Francais 2023

Latin Student Association to hold spirit week

The drastic rise in teen suicide rates

HICD community advocates against county jail building proposal

The vein drain

Seniors reach out to new students through Navigator program

Comments (0)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Acceder / Registro

Mexican university system for International Students

The Mexican university system is unique and is very different from the university system of international students. It is similar to the American one with some special features that will make you want to make an exchange semester in Mexico!

The Mexican classes

In Mexico, students have in general fewer hours of classes. However, there is more homework and more personal work to do at home. Students study before coming to class and exchange on what they have studied during the class.

Most of the classes are conducted in a different way. These are lessons in the form of discussions and debates, each student gives his opinion and there are many oral presentations to make. Even if there are also lectures.

The number of students in the classes is generally smaller, and you will not always find the same people in each course. In fact, you can choose all your courses from a very wide range of options.

So the Mexican university system offers a different way of learning than the European one.

Student-teacher relationship

Mexican teachers are closer to their students. For example, teachers are called by their first names.

They often chat with their students on WhatsApp. But we will develop this point in the next part !

They are also much more understandable and flexible. For example, if a student does not turn in his or her work on time for one reason or another, generally it can be returned the next day.

Also, most of them accept delays in class, and student exits before the end of the course but it’s not the same for all the universities.

A different mode of communication

All of the students who have done their semester in Mexico share the same opinion: Mexican professors are much more communicative!

Getting in touch with a Mexican teacher is easier. They will always be willing to answer to your questions and help you. Also, they are very patient with international students !

It’s very common in the Mexican university system to create WhatsApp groups with the teachers to keep each other up to date on homework assignments and other stuffs.

It simplifies a lot the communication!

To resume, there is a lot more human relations.

Mexican campuses are very similar to American campuses. They are very large and have many amenities and green spaces. We can even sometimes compare them to small towns.

For example, the TEC (Tecnológico de Monterrey) has a swimming pool, basketball courts, a TEC shop, numerous restaurants, etc.

The school provides dance lessons, drama lessons, singing lessons. But also offers soccer, rugby, swimming, and many other activities .

And to conclude with another example that illustrates it, to enter to the TEC you need a badge !

There are a lot of foreign students in Europe who dream of joining this kind of school!

The Mexican school calendar

Finally, the Mexican school calendar is also different !

In Mexico, the summer holidays end in July. So the lessons generally start in early August and end in May.

The Mexican education system offers to its students two weeks of vacation for Christmas and two weeks of vacation for the Holy Week in April. The international students can take the opportunity to travel during this period!

But that information also depends a lot on universities.

To conclude, the Mexican university system is very different from the European one. Many exchange students in Mexico prefer this system because they make them feel more integrated into their university!

We advise you to read the article about doing your exchange in Guadalajara and the one about studying in Mexico City !

Entradas relacionadas

Vibrant Adventures: Exchange Student in Mexico – Top Reasons Revealed

Explorando la fiesta de comida típica mexicana de Guadalajara

Tips for your first week in Mexico

Be part of our great community of friends, carrito de la compra.

No products in the cart.

How Much Homework Is Too Much for Our Teens?

Here's what educators and parents can do to help kids find the right balance between school and home.

Does Your Teen Have Too Much Homework?

Today’s teens are under a lot of pressure.

They're under pressure to succeed, to win, to be the best and to get into the top colleges. With so much pressure, is it any wonder today’s youth report being under as much stress as their parents? In fact, during the school year, teens say they experience stress levels higher than those reported by adults, according to a previous American Psychological Association "Stress in America" survey.

Odds are if you ask a teen what's got them so worked up, the subject of school will come up. School can cause a lot of stress, which can lead to other serious problems, like sleep deprivation . According to the National Sleep Foundation, teens need between eight and 10 hours of sleep each night, but only 15 percent are even getting close to that amount. During the school week, most teens only get about six hours of zzz’s a night, and some of that sleep deficit may be attributed to homework.

When it comes to school, many adults would rather not trade places with a teen. Think about it. They get up at the crack of dawn and get on the bus when it’s pitch dark outside. They put in a full day sitting in hours of classes (sometimes four to seven different classes daily), only to get more work dumped on them to do at home. To top it off, many kids have after-school obligations, such as extracurricular activities including clubs and sports , and some have to work. After a long day, they finally get home to do even more work – schoolwork.

[Read: What Parents Should Know About Teen Depression .]

Homework is not only a source of stress for students, but it can also be a hassle for parents. If you are the parent of a kid who strives to be “perfect," then you know all too well how much time your child spends making sure every bit of homework is complete, even if it means pulling an all-nighter. On the flip side, if you’re the parent of a child who decided that school ends when the last bell rings, then you know how exhausting that homework tug-of-war can be. And heaven forbid if you’re that parent who is at their wit's end because your child excels on tests and quizzes but fails to turn in assignments. The woes of academics can go well beyond the confines of the school building and right into the home.

This is the time of year when many students and parents feel the burden of the academic load. Following spring break, many schools across the nation head into the final stretch of the year. As a result, some teachers increase the amount of homework they give. The assignments aren’t punishment, although to students and parents who are having to constantly stay on top of their kids' schoolwork, they can sure seem that way.

From a teacher’s perspective, the assignments are meant to help students better understand the course content and prepare for upcoming exams. Some schools have state-mandated end of grade or final tests. In those states these tests can account for 20 percent of a student’s final grade. So teachers want to make sure that they cover the entire curriculum before that exam. Aside from state-mandated tests, some high school students are enrolled in advanced placement or international baccalaureate college-level courses that have final tests given a month or more before the end of the term. In order to cover all of the content, teachers must maintain an accelerated pace. All of this means more out of class assignments.

Given the challenges kids face, there are a few questions parents and educators should consider:

Is homework necessary?

Many teens may give a quick "no" to this question, but the verdict is still out. Research supports both sides of the argument. Personally, I would say, yes, some homework is necessary, but it must be purposeful. If it’s busy work, then it’s a waste of time. Homework should be a supplemental teaching tool. Too often, some youth go home completely lost as they haven’t grasped concepts covered in class and they may become frustrated and overwhelmed.

For a parent who has been in this situation, you know how frustrating this can be, especially if it’s a subject that you haven’t encountered in a while. Homework can serve a purpose such as improving grades, increasing test scores and instilling a good work ethic. Purposeful homework can come in the form of individualizing assignments based on students’ needs or helping students practice newly acquired skills.

Homework should not be used to extend class time to cover more material. If your child is constantly coming home having to learn the material before doing the assignments, then it’s time to contact the teacher and set up a conference. Listen when kids express their concerns (like if they say they're expected to know concepts not taught in class) as they will provide clues about what’s happening or not happening in the classroom. Plus, getting to the root of the problem can help with keeping the peace at home too, as an irritable and grumpy teen can disrupt harmonious family dynamics .

[Read: What Makes Teens 'Most Likely to Succeed?' ]

How much is too much?

According to the National PTA and the National Education Association, students should only be doing about 10 minutes of homework per night per grade level. But teens are doing a lot more than that, according to a poll of high school students by the organization Statistic Brain . In that poll teens reported spending, on average, more than three hours on homework each school night, with 11th graders spending more time on homework than any other grade level. By contrast, some polls have shown that U.S. high school students report doing about seven hours of homework per week.

Much of a student's workload boils down to the courses they take (such as advanced or college prep classes), the teaching philosophy of educators and the student’s commitment to doing the work. Regardless, research has shown that doing more than two hours of homework per night does not benefit high school students. Having lots of homework to do every day makes it difficult for teens to have any downtime , let alone family time .

How do we respond to students' needs?

As an educator and parent, I can honestly say that oftentimes there is a mismatch in what teachers perceive as only taking 15 minutes and what really takes 45 minutes to complete. If you too find this to be the case, then reach out to your child's teacher and find out why the assignments are taking longer than anticipated for your child to complete.

Also, ask the teacher about whether faculty communicate regularly with one another about large upcoming assignments. Whether it’s setting up a shared school-wide assignment calendar or collaborating across curriculums during faculty meetings, educators need to discuss upcoming tests and projects, so students don’t end up with lots of assignments all competing for their attention and time at once. Inevitably, a student is going to get slammed occasionally, but if they have good rapport with their teachers, they will feel comfortable enough to reach out and see if alternative options are available. And as a parent, you can encourage your kid to have that dialogue with the teacher.

Often teens would rather blend into the class than stand out. That’s unfortunate because research has shown time and time again that positive teacher-student relationships are strong predictors of student engagement and achievement. By and large, most teachers appreciate students advocating for themselves and will go the extra mile to help them out.

Can there be a balance between home and school?

Students can strike a balance between school and home, but parents will have to help them find it. They need your guidance to learn how to better manage their time, get organized and prioritize tasks, which are all important life skills. Equally important is developing good study habits. Some students may need tutoring or coaching to help them learn new material or how to take notes and study. Also, don’t forget the importance of parent-teacher communication. Most educators want nothing more than for their students to succeed in their courses.

Learning should be fun, not mundane and cumbersome. Homework should only be given if its purposeful and in moderation. Equally important to homework is engaging in activities, socializing with friends and spending time with the family.

[See: 10 Concerns Parents Have About Their Kids' Health .]

Most adults don’t work a full-time job and then go home and do three more hours of work, and neither should your child. It's not easy learning to balance everything, especially if you're a teen. If your child is spending several hours on homework each night, don't hesitate to reach out to teachers and, if need be, school officials. Collectively, we can all work together to help our children de-stress and find the right balance between school and home.

12 Questions You Should Ask Your Kids at Dinner

Tags: parenting , family , family health , teens , education , high school , stress

Most Popular

Senior Care

Patient Advice

health disclaimer »

Disclaimer and a note about your health ».

Your Health

A guide to nutrition and wellness from the health team at U.S. News & World Report.

You May Also Like

Moderating pandemic news consumption.

Victor G. Carrion, M.D. June 8, 2020

Helping Young People Gain Resilience

Nancy Willard May 18, 2020

Keep Kids on Track With Reading During the Pandemic

Ashley Johnson and Tom Dillon May 14, 2020

Pandemic and Summer Education

Nancy Willard May 12, 2020

Trauma and Childhood Regression

Dr. Gail Saltz May 8, 2020

The Sandwich Generation and the Pandemic

Laurie Wolk May 6, 2020

Adapting to an Evolving Pandemic

Laurie Wolk May 1, 2020

Picky Eating During Quarantine

Jill Castle May 1, 2020

Baby Care During the Pandemic

Dr. Natasha Burgert April 29, 2020

Co-Parenting During the Pandemic

Ron Deal April 24, 2020

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71970990/05_nohomework_Jiayue_Li.0.jpg)

Filed under:

- The Highlight

Nobody knows what the point of homework is

The homework wars are back.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Nobody knows what the point of homework is

As the Covid-19 pandemic began and students logged into their remote classrooms, all work, in effect, became homework. But whether or not students could complete it at home varied. For some, schoolwork became public-library work or McDonald’s-parking-lot work.

Luis Torres, the principal of PS 55, a predominantly low-income community elementary school in the south Bronx, told me that his school secured Chromebooks for students early in the pandemic only to learn that some lived in shelters that blocked wifi for security reasons. Others, who lived in housing projects with poor internet reception, did their schoolwork in laundromats.

According to a 2021 Pew survey , 25 percent of lower-income parents said their children, at some point, were unable to complete their schoolwork because they couldn’t access a computer at home; that number for upper-income parents was 2 percent.

The issues with remote learning in March 2020 were new. But they highlighted a divide that had been there all along in another form: homework. And even long after schools have resumed in-person classes, the pandemic’s effects on homework have lingered.

Over the past three years, in response to concerns about equity, schools across the country, including in Sacramento, Los Angeles , San Diego , and Clark County, Nevada , made permanent changes to their homework policies that restricted how much homework could be given and how it could be graded after in-person learning resumed.

Three years into the pandemic, as districts and teachers reckon with Covid-era overhauls of teaching and learning, schools are still reconsidering the purpose and place of homework. Whether relaxing homework expectations helps level the playing field between students or harms them by decreasing rigor is a divisive issue without conclusive evidence on either side, echoing other debates in education like the elimination of standardized test scores from some colleges’ admissions processes.

I first began to wonder if the homework abolition movement made sense after speaking with teachers in some Massachusetts public schools, who argued that rather than help disadvantaged kids, stringent homework restrictions communicated an attitude of low expectations. One, an English teacher, said she felt the school had “just given up” on trying to get the students to do work; another argued that restrictions that prohibit teachers from assigning take-home work that doesn’t begin in class made it difficult to get through the foreign-language curriculum. Teachers in other districts have raised formal concerns about homework abolition’s ability to close gaps among students rather than widening them.

Many education experts share this view. Harris Cooper, a professor emeritus of psychology at Duke who has studied homework efficacy, likened homework abolition to “playing to the lowest common denominator.”

But as I learned after talking to a variety of stakeholders — from homework researchers to policymakers to parents of schoolchildren — whether to abolish homework probably isn’t the right question. More important is what kind of work students are sent home with and where they can complete it. Chances are, if schools think more deeply about giving constructive work, time spent on homework will come down regardless.

There’s no consensus on whether homework works

The rise of the no-homework movement during the Covid-19 pandemic tapped into long-running disagreements over homework’s impact on students. The purpose and effectiveness of homework have been disputed for well over a century. In 1901, for instance, California banned homework for students up to age 15, and limited it for older students, over concerns that it endangered children’s mental and physical health. The newest iteration of the anti-homework argument contends that the current practice punishes students who lack support and rewards those with more resources, reinforcing the “myth of meritocracy.”

But there is still no research consensus on homework’s effectiveness; no one can seem to agree on what the right metrics are. Much of the debate relies on anecdotes, intuition, or speculation.

Researchers disagree even on how much research exists on the value of homework. Kathleen Budge, the co-author of Turning High-Poverty Schools Into High-Performing Schools and a professor at Boise State, told me that homework “has been greatly researched.” Denise Pope, a Stanford lecturer and leader of the education nonprofit Challenge Success, said, “It’s not a highly researched area because of some of the methodological problems.”

Experts who are more sympathetic to take-home assignments generally support the “10-minute rule,” a framework that estimates the ideal amount of homework on any given night by multiplying the student’s grade by 10 minutes. (A ninth grader, for example, would have about 90 minutes of work a night.) Homework proponents argue that while it is difficult to design randomized control studies to test homework’s effectiveness, the vast majority of existing studies show a strong positive correlation between homework and high academic achievement for middle and high school students. Prominent critics of homework argue that these correlational studies are unreliable and point to studies that suggest a neutral or negative effect on student performance. Both agree there is little to no evidence for homework’s effectiveness at an elementary school level, though proponents often argue that it builds constructive habits for the future.

For anyone who remembers homework assignments from both good and bad teachers, this fundamental disagreement might not be surprising. Some homework is pointless and frustrating to complete. Every week during my senior year of high school, I had to analyze a poem for English and decorate it with images found on Google; my most distinct memory from that class is receiving a demoralizing 25-point deduction because I failed to present my analysis on a poster board. Other assignments really do help students learn: After making an adapted version of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book for a ninth grade history project, I was inspired to check out from the library and read a biography of the Chinese ruler.

For homework opponents, the first example is more likely to resonate. “We’re all familiar with the negative effects of homework: stress, exhaustion, family conflict, less time for other activities, diminished interest in learning,” Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, which challenges common justifications for homework, told me in an email. “And these effects may be most pronounced among low-income students.” Kohn believes that schools should make permanent any moratoria implemented during the pandemic, arguing that there are no positives at all to outweigh homework’s downsides. Recent studies , he argues , show the benefits may not even materialize during high school.

In the Marlborough Public Schools, a suburban district 45 minutes west of Boston, school policy committee chair Katherine Hennessy described getting kids to complete their homework during remote education as “a challenge, to say the least.” Teachers found that students who spent all day on their computers didn’t want to spend more time online when the day was over. So, for a few months, the school relaxed the usual practice and teachers slashed the quantity of nightly homework.

Online learning made the preexisting divides between students more apparent, she said. Many students, even during normal circumstances, lacked resources to keep them on track and focused on completing take-home assignments. Though Marlborough Schools is more affluent than PS 55, Hennessy said many students had parents whose work schedules left them unable to provide homework help in the evenings. The experience tracked with a common divide in the country between children of different socioeconomic backgrounds.

So in October 2021, months after the homework reduction began, the Marlborough committee made a change to the district’s policy. While teachers could still give homework, the assignments had to begin as classwork. And though teachers could acknowledge homework completion in a student’s participation grade, they couldn’t count homework as its own grading category. “Rigorous learning in the classroom does not mean that that classwork must be assigned every night,” the policy stated . “Extensions of class work is not to be used to teach new content or as a form of punishment.”

Canceling homework might not do anything for the achievement gap

The critiques of homework are valid as far as they go, but at a certain point, arguments against homework can defy the commonsense idea that to retain what they’re learning, students need to practice it.

“Doesn’t a kid become a better reader if he reads more? Doesn’t a kid learn his math facts better if he practices them?” said Cathy Vatterott, an education researcher and professor emeritus at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. After decades of research, she said it’s still hard to isolate the value of homework, but that doesn’t mean it should be abandoned.

Blanket vilification of homework can also conflate the unique challenges facing disadvantaged students as compared to affluent ones, which could have different solutions. “The kids in the low-income schools are being hurt because they’re being graded, unfairly, on time they just don’t have to do this stuff,” Pope told me. “And they’re still being held accountable for turning in assignments, whether they’re meaningful or not.” On the other side, “Palo Alto kids” — students in Silicon Valley’s stereotypically pressure-cooker public schools — “are just bombarded and overloaded and trying to stay above water.”

Merely getting rid of homework doesn’t solve either problem. The United States already has the second-highest disparity among OECD (the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations between time spent on homework by students of high and low socioeconomic status — a difference of more than three hours, said Janine Bempechat, clinical professor at Boston University and author of No More Mindless Homework .

When she interviewed teachers in Boston-area schools that had cut homework before the pandemic, Bempechat told me, “What they saw immediately was parents who could afford it immediately enrolled their children in the Russian School of Mathematics,” a math-enrichment program whose tuition ranges from $140 to about $400 a month. Getting rid of homework “does nothing for equity; it increases the opportunity gap between wealthier and less wealthy families,” she said. “That solution troubles me because it’s no solution at all.”

A group of teachers at Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia, made the same point after the school district proposed an overhaul of its homework policies, including removing penalties for missing homework deadlines, allowing unlimited retakes, and prohibiting grading of homework.

“Given the emphasis on equity in today’s education systems,” they wrote in a letter to the school board, “we believe that some of the proposed changes will actually have a detrimental impact towards achieving this goal. Families that have means could still provide challenging and engaging academic experiences for their children and will continue to do so, especially if their children are not experiencing expected rigor in the classroom.” At a school where more than a third of students are low-income, the teachers argued, the policies would prompt students “to expect the least of themselves in terms of effort, results, and responsibility.”

Not all homework is created equal

Despite their opposing sides in the homework wars, most of the researchers I spoke to made a lot of the same points. Both Bempechat and Pope were quick to bring up how parents and schools confuse rigor with workload, treating the volume of assignments as a proxy for quality of learning. Bempechat, who is known for defending homework, has written extensively about how plenty of it lacks clear purpose, requires the purchasing of unnecessary supplies, and takes longer than it needs to. Likewise, when Pope instructs graduate-level classes on curriculum, she asks her students to think about the larger purpose they’re trying to achieve with homework: If they can get the job done in the classroom, there’s no point in sending home more work.

At its best, pandemic-era teaching facilitated that last approach. Honolulu-based teacher Christina Torres Cawdery told me that, early in the pandemic, she often had a cohort of kids in her classroom for four hours straight, as her school tried to avoid too much commingling. She couldn’t lecture for four hours, so she gave the students plenty of time to complete independent and project-based work. At the end of most school days, she didn’t feel the need to send them home with more to do.

A similar limited-homework philosophy worked at a public middle school in Chelsea, Massachusetts. A couple of teachers there turned as much class as possible into an opportunity for small-group practice, allowing kids to work on problems that traditionally would be assigned for homework, Jessica Flick, a math coach who leads department meetings at the school, told me. It was inspired by a philosophy pioneered by Simon Fraser University professor Peter Liljedahl, whose influential book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics reframes homework as “check-your-understanding questions” rather than as compulsory work. Last year, Flick found that the two eighth grade classes whose teachers adopted this strategy performed the best on state tests, and this year, she has encouraged other teachers to implement it.

Teachers know that plenty of homework is tedious and unproductive. Jeannemarie Dawson De Quiroz, who has taught for more than 20 years in low-income Boston and Los Angeles pilot and charter schools, says that in her first years on the job she frequently assigned “drill and kill” tasks and questions that she now feels unfairly stumped students. She said designing good homework wasn’t part of her teaching programs, nor was it meaningfully discussed in professional development. With more experience, she turned as much class time as she could into practice time and limited what she sent home.

“The thing about homework that’s sticky is that not all homework is created equal,” says Jill Harrison Berg, a former teacher and the author of Uprooting Instructional Inequity . “Some homework is a genuine waste of time and requires lots of resources for no good reason. And other homework is really useful.”

Cutting homework has to be part of a larger strategy

The takeaways are clear: Schools can make cuts to homework, but those cuts should be part of a strategy to improve the quality of education for all students. If the point of homework was to provide more practice, districts should think about how students can make it up during class — or offer time during or after school for students to seek help from teachers. If it was to move the curriculum along, it’s worth considering whether strategies like Liljedahl’s can get more done in less time.

Some of the best thinking around effective assignments comes from those most critical of the current practice. Denise Pope proposes that, before assigning homework, teachers should consider whether students understand the purpose of the work and whether they can do it without help. If teachers think it’s something that can’t be done in class, they should be mindful of how much time it should take and the feedback they should provide. It’s questions like these that De Quiroz considered before reducing the volume of work she sent home.

More than a year after the new homework policy began in Marlborough, Hennessy still hears from parents who incorrectly “think homework isn’t happening” despite repeated assurances that kids still can receive work. She thinks part of the reason is that education has changed over the years. “I think what we’re trying to do is establish that homework may be an element of educating students,” she told me. “But it may not be what parents think of as what they grew up with. ... It’s going to need to adapt, per the teaching and the curriculum, and how it’s being delivered in each classroom.”

For the policy to work, faculty, parents, and students will all have to buy into a shared vision of what school ought to look like. The district is working on it — in November, it hosted and uploaded to YouTube a round-table discussion on homework between district administrators — but considering the sustained confusion, the path ahead seems difficult.

When I asked Luis Torres about whether he thought homework serves a useful part in PS 55’s curriculum, he said yes, of course it was — despite the effort and money it takes to keep the school open after hours to help them do it. “The children need the opportunity to practice,” he said. “If you don’t give them opportunities to practice what they learn, they’re going to forget.” But Torres doesn’t care if the work is done at home. The school stays open until around 6 pm on weekdays, even during breaks. Tutors through New York City’s Department of Youth and Community Development programs help kids with work after school so they don’t need to take it with them.

As schools weigh the purpose of homework in an unequal world, it’s tempting to dispose of a practice that presents real, practical problems to students across the country. But getting rid of homework is unlikely to do much good on its own. Before cutting it, it’s worth thinking about what good assignments are meant to do in the first place. It’s crucial that students from all socioeconomic backgrounds tackle complex quantitative problems and hone their reading and writing skills. It’s less important that the work comes home with them.

Jacob Sweet is a freelance writer in Somerville, Massachusetts. He is a frequent contributor to the New Yorker, among other publications.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

Millions rely on Vox’s journalism to understand the coronavirus crisis. We believe it pays off for all of us, as a society and a democracy, when our neighbors and fellow citizens can access clear, concise information on the pandemic. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive. Support from our readers helps us keep it free for everyone. If you have already made a financial contribution to Vox, thank you. If not, please consider making a contribution today from as little as $3.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Can we protect and profit from the oceans?

Sometimes kids need a push. here’s how to do it kindly., who gets to flourish, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Do our kids have too much homework?

by: Marian Wilde | Updated: January 31, 2024

Print article

Many students and their parents are frazzled by the amount of homework being piled on in the schools. Yet many researchers say that American students have just the right amount of homework.

“Kids today are overwhelmed!” a parent recently wrote in an email to GreatSchools.org “My first-grade son was required to research a significant person from history and write a paper of at least two pages about the person, with a bibliography. How can he be expected to do that by himself? He just started to learn to read and write a couple of months ago. Schools are pushing too hard and expecting too much from kids.”

Diane Garfield, a fifth grade teacher in San Francisco, concurs. “I believe that we’re stressing children out,” she says.