In a short paper—even a research paper—you don’t need to provide an exhaustive summary as part of your conclusion. But you do need to make some kind of transition between your final body paragraph and your concluding paragraph. This may come in the form of a few sentences of summary. Or it may come in the form of a sentence that brings your readers back to your thesis or main idea and reminds your readers where you began and how far you have traveled.

So, for example, in a paper about the relationship between ADHD and rejection sensitivity, Vanessa Roser begins by introducing readers to the fact that researchers have studied the relationship between the two conditions and then provides her explanation of that relationship. Here’s her thesis: “While socialization may indeed be an important factor in RS, I argue that individuals with ADHD may also possess a neurological predisposition to RS that is exacerbated by the differing executive and emotional regulation characteristic of ADHD.”

In her final paragraph, Roser reminds us of where she started by echoing her thesis: “This literature demonstrates that, as with many other conditions, ADHD and RS share a delicately intertwined pattern of neurological similarities that is rooted in the innate biology of an individual’s mind, a connection that cannot be explained in full by the behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

Highlight the “so what”

At the beginning of your paper, you explain to your readers what’s at stake—why they should care about the argument you’re making. In your conclusion, you can bring readers back to those stakes by reminding them why your argument is important in the first place. You can also draft a few sentences that put those stakes into a new or broader context.

In the conclusion to her paper about ADHD and RS, Roser echoes the stakes she established in her introduction—that research into connections between ADHD and RS has led to contradictory results, raising questions about the “behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

She writes, “as with many other conditions, ADHD and RS share a delicately intertwined pattern of neurological similarities that is rooted in the innate biology of an individual’s mind, a connection that cannot be explained in full by the behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

Leave your readers with the “now what”

After the “what” and the “so what,” you should leave your reader with some final thoughts. If you have written a strong introduction, your readers will know why you have been arguing what you have been arguing—and why they should care. And if you’ve made a good case for your thesis, then your readers should be in a position to see things in a new way, understand new questions, or be ready for something that they weren’t ready for before they read your paper.

In her conclusion, Roser offers two “now what” statements. First, she explains that it is important to recognize that the flawed behavioral mediation hypothesis “seems to place a degree of fault on the individual. It implies that individuals with ADHD must have elicited such frequent or intense rejection by virtue of their inadequate social skills, erasing the possibility that they may simply possess a natural sensitivity to emotion.” She then highlights the broader implications for treatment of people with ADHD, noting that recognizing the actual connection between rejection sensitivity and ADHD “has profound implications for understanding how individuals with ADHD might best be treated in educational settings, by counselors, family, peers, or even society as a whole.”

To find your own “now what” for your essay’s conclusion, try asking yourself these questions:

- What can my readers now understand, see in a new light, or grapple with that they would not have understood in the same way before reading my paper? Are we a step closer to understanding a larger phenomenon or to understanding why what was at stake is so important?

- What questions can I now raise that would not have made sense at the beginning of my paper? Questions for further research? Other ways that this topic could be approached?

- Are there other applications for my research? Could my questions be asked about different data in a different context? Could I use my methods to answer a different question?

- What action should be taken in light of this argument? What action do I predict will be taken or could lead to a solution?

- What larger context might my argument be a part of?

What to avoid in your conclusion

- a complete restatement of all that you have said in your paper.

- a substantial counterargument that you do not have space to refute; you should introduce counterarguments before your conclusion.

- an apology for what you have not said. If you need to explain the scope of your paper, you should do this sooner—but don’t apologize for what you have not discussed in your paper.

- fake transitions like “in conclusion” that are followed by sentences that aren’t actually conclusions. (“In conclusion, I have now demonstrated that my thesis is correct.”)

- picture_as_pdf Conclusions

Conclusions

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain the functions of conclusions, offer strategies for writing effective ones, help you evaluate conclusions you’ve drafted, and suggest approaches to avoid.

About conclusions

Introductions and conclusions can be difficult to write, but they’re worth investing time in. They can have a significant influence on a reader’s experience of your paper.

Just as your introduction acts as a bridge that transports your readers from their own lives into the “place” of your analysis, your conclusion can provide a bridge to help your readers make the transition back to their daily lives. Such a conclusion will help them see why all your analysis and information should matter to them after they put the paper down.

Your conclusion is your chance to have the last word on the subject. The conclusion allows you to have the final say on the issues you have raised in your paper, to synthesize your thoughts, to demonstrate the importance of your ideas, and to propel your reader to a new view of the subject. It is also your opportunity to make a good final impression and to end on a positive note.

Your conclusion can go beyond the confines of the assignment. The conclusion pushes beyond the boundaries of the prompt and allows you to consider broader issues, make new connections, and elaborate on the significance of your findings.

Your conclusion should make your readers glad they read your paper. Your conclusion gives your reader something to take away that will help them see things differently or appreciate your topic in personally relevant ways. It can suggest broader implications that will not only interest your reader, but also enrich your reader’s life in some way. It is your gift to the reader.

Strategies for writing an effective conclusion

One or more of the following strategies may help you write an effective conclusion:

- Play the “So What” Game. If you’re stuck and feel like your conclusion isn’t saying anything new or interesting, ask a friend to read it with you. Whenever you make a statement from your conclusion, ask the friend to say, “So what?” or “Why should anybody care?” Then ponder that question and answer it. Here’s how it might go: You: Basically, I’m just saying that education was important to Douglass. Friend: So what? You: Well, it was important because it was a key to him feeling like a free and equal citizen. Friend: Why should anybody care? You: That’s important because plantation owners tried to keep slaves from being educated so that they could maintain control. When Douglass obtained an education, he undermined that control personally. You can also use this strategy on your own, asking yourself “So What?” as you develop your ideas or your draft.

- Return to the theme or themes in the introduction. This strategy brings the reader full circle. For example, if you begin by describing a scenario, you can end with the same scenario as proof that your essay is helpful in creating a new understanding. You may also refer to the introductory paragraph by using key words or parallel concepts and images that you also used in the introduction.

- Synthesize, don’t summarize. Include a brief summary of the paper’s main points, but don’t simply repeat things that were in your paper. Instead, show your reader how the points you made and the support and examples you used fit together. Pull it all together.

- Include a provocative insight or quotation from the research or reading you did for your paper.

- Propose a course of action, a solution to an issue, or questions for further study. This can redirect your reader’s thought process and help them to apply your info and ideas to their own life or to see the broader implications.

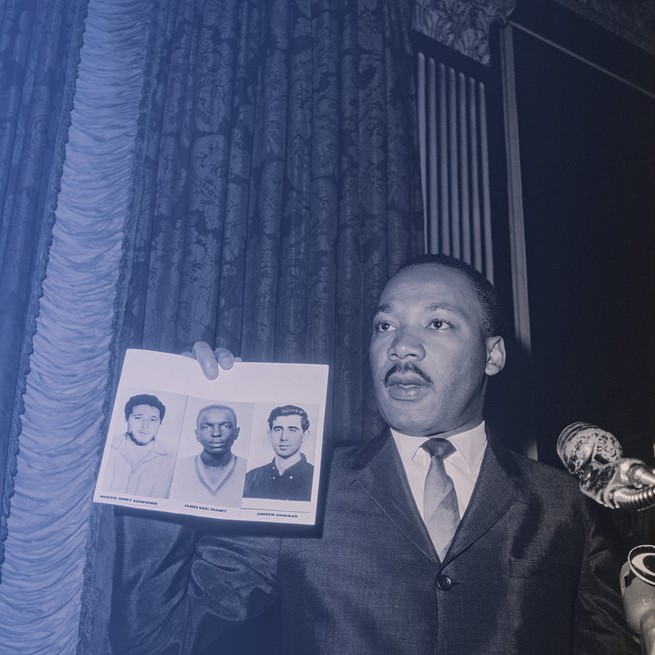

- Point to broader implications. For example, if your paper examines the Greensboro sit-ins or another event in the Civil Rights Movement, you could point out its impact on the Civil Rights Movement as a whole. A paper about the style of writer Virginia Woolf could point to her influence on other writers or on later feminists.

Strategies to avoid

- Beginning with an unnecessary, overused phrase such as “in conclusion,” “in summary,” or “in closing.” Although these phrases can work in speeches, they come across as wooden and trite in writing.

- Stating the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion.

- Introducing a new idea or subtopic in your conclusion.

- Ending with a rephrased thesis statement without any substantive changes.

- Making sentimental, emotional appeals that are out of character with the rest of an analytical paper.

- Including evidence (quotations, statistics, etc.) that should be in the body of the paper.

Four kinds of ineffective conclusions

- The “That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It” Conclusion. This conclusion just restates the thesis and is usually painfully short. It does not push the ideas forward. People write this kind of conclusion when they can’t think of anything else to say. Example: In conclusion, Frederick Douglass was, as we have seen, a pioneer in American education, proving that education was a major force for social change with regard to slavery.

- The “Sherlock Holmes” Conclusion. Sometimes writers will state the thesis for the very first time in the conclusion. You might be tempted to use this strategy if you don’t want to give everything away too early in your paper. You may think it would be more dramatic to keep the reader in the dark until the end and then “wow” them with your main idea, as in a Sherlock Holmes mystery. The reader, however, does not expect a mystery, but an analytical discussion of your topic in an academic style, with the main argument (thesis) stated up front. Example: (After a paper that lists numerous incidents from the book but never says what these incidents reveal about Douglass and his views on education): So, as the evidence above demonstrates, Douglass saw education as a way to undermine the slaveholders’ power and also an important step toward freedom.

- The “America the Beautiful”/”I Am Woman”/”We Shall Overcome” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion usually draws on emotion to make its appeal, but while this emotion and even sentimentality may be very heartfelt, it is usually out of character with the rest of an analytical paper. A more sophisticated commentary, rather than emotional praise, would be a more fitting tribute to the topic. Example: Because of the efforts of fine Americans like Frederick Douglass, countless others have seen the shining beacon of light that is education. His example was a torch that lit the way for others. Frederick Douglass was truly an American hero.

- The “Grab Bag” Conclusion. This kind of conclusion includes extra information that the writer found or thought of but couldn’t integrate into the main paper. You may find it hard to leave out details that you discovered after hours of research and thought, but adding random facts and bits of evidence at the end of an otherwise-well-organized essay can just create confusion. Example: In addition to being an educational pioneer, Frederick Douglass provides an interesting case study for masculinity in the American South. He also offers historians an interesting glimpse into slave resistance when he confronts Covey, the overseer. His relationships with female relatives reveal the importance of family in the slave community.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Douglass, Frederick. 1995. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. New York: Dover.

Hamilton College. n.d. “Conclusions.” Writing Center. Accessed June 14, 2019. https://www.hamilton.edu//academics/centers/writing/writing-resources/conclusions .

Holewa, Randa. 2004. “Strategies for Writing a Conclusion.” LEO: Literacy Education Online. Last updated February 19, 2004. https://leo.stcloudstate.edu/acadwrite/conclude.html.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Applying for Tertiary Education

- Application Essays

How to End a College Essay: The Do’s and Don’ts

Last Updated: January 16, 2024 Fact Checked

Strategies to End Your College Essay

- Things to Avoid

Expert Interview

This article was co-authored by Alexander Ruiz, M.Ed. and by wikiHow staff writer, Sophie Burkholder, BA . Alexander Ruiz is an Educational Consultant and the Educational Director of Link Educational Institute, a tutoring business based in Claremont, California that provides customizable educational plans, subject and test prep tutoring, and college application consulting. With over a decade and a half of experience in the education industry, Alexander coaches students to increase their self-awareness and emotional intelligence while achieving skills and the goal of achieving skills and higher education. He holds a BA in Psychology from Florida International University and an MA in Education from Georgia Southern University. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources.

Deadlines are whizzing by, primary-colored pennants are waving, and keyboards are clicking and clacking…it’s college admissions season! Beyond the test scores and grade point averages, your personal statement is your one chance to show colleges who you are—and for some reason, wrapping up that essay can be the hardest part. We spoke to expert academic tutor and educational consultant Alexander Ruiz to give you strategies for concluding your college essay, along with the examples included in this comprehensive guide to college essay conclusions.

Things You Should Know

- End your college essay by returning to an idea or image you included in your intro or as your hook. This callback satisfies your reader with a full-circle effect.

- Look to the future to conclude your college essay on a positive and hopeful note. Describe your goals and the impact you’ll have on the world.

- Finish your college essay with a lesson learned. After sharing life experiences, describe what you’ve learned and how they’ve prepared you for your next step.

- As expert educational consultant Alexander Ruiz explains, universities are “trying to understand ‘How do you see that you fit within our school?’ Even though the prompt is asking ‘Why did you choose the school?’, it really is truly asking ‘How do you fit within the student body? How do you fit within our campus?’”

- Example of a “college address” conclusion: I want to be part of the long legacy of civil rights activists and leaders, from Martin Luther King, Jr. to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who have studied within the walls of Boston University. I’ve planted the seeds of this work through my two years of volunteering and campaigning in local elections. If admitted to your globally renowned Political Science program, I will be thrilled to grow my skills in Public Policy Analysis and ultimately serve the dynamic and deserving communities of Greater Boston.

- Example of a “full circle” conclusion: This year was a challenge in many ways. But I know that when I drive across those state lines again next fall, I’ll be looking back at the swirling blues and grays of the Boise sky, already anxiously awaiting the next time I get to come back home.

- Example intro hook for above conclusion: As my parents drove us across the Idaho state line, I looked out at the cloud-covered sky and thought: Well, this sure doesn’t look like home.

- Example of a “lesson learned” conclusion: Having the opportunity to travel around Latin America—bouncing between coastal towns like Sayulita and sprawling cities like Buenos Aires—I learned the importance of understanding other cultures and their perspectives. In expanding the limits of my physical world, I also had the opportunity to expand my worldview.

- Example of a “look forward” conclusion: When my great-great-grandchildren fasten their shoes with a futuristic version of Velcro and head down the road to school, they will do so with excitement and purpose. They’ll look forward to the day’s tasks of digging in the garden for Biology, journaling on their socio-emotional well-being in Health class, and debating the issues of their times in Social Studies. An education system built around students, their needs, and their futures—as a hopeful member of your teaching college, that is a future I am enthusiastic to have a hand in.

- Example of a “last-minute reveal” conclusion: After multiple paragraphs of stories from swim meets throughout the writer’s life, they conclude with, I wasn’t just swimming to beat the stopwatch hanging around my coach’s neck. I was swimming because it gave me freedom, a place to reflect, and an ability to push back against even the strongest currents.

- This strategy is difficult to pull off, as our instinct is to put our thesis right at the top. However, when it comes to college admissions, academic tutor Alexander Ruiz warns against “the five-paragraph format, the intro, body, body, body, conclusion.”

- As Ruiz continues to explain, “When it comes to telling your story and sharing how valuable your experience will be to a school, [the five-paragraph format] is not going to be able to portray that in a way that's going to be very attractive. So I think that one of the main mistakes that people make is saying these quantitative measures are going to speak for themselves, and they don't put enough work into being able to tell their story in their essays.”

- Example of a “plot twist” conclusion: Every law office I interned at over the past four years, despite their intensity, was instrumental in shaping my path and who I am. They prepared me for college and a career and gave me a clear view of what I wanted to do: not study law. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed every minute of learning about the inner workings of our legal system, but now I want to put that knowledge toward my true passion: helping foster kids via a social services career.

- Example of a thought-question conclusion: After all, with no other world to compare ours to, who are we to say a better world isn’t possible?

- Example of a “call to action” conclusion: Now that I’ve spent some thousand-odd words advocating for voter rights, voter registration, and rattling off anecdotes of my door-to-door campaigning, I just have one question left: are you registered to vote?

Things to Avoid in Your College Essay Conclusion

- Don’t: In conclusion, my family’s struggle with poverty over the past five years taught me much about resilience.

- Do: Tonight, my dad will put food on the table, as he always manages to. My mom will kiss him on the cheek as soon as she walks in the door from work, sighing as she finally sits down for the day. Despite all the challenges of the last five years, I’ve watched my parents overcome every obstacle with resilience and grit—and what I’ve learned from them is something I wouldn’t give up for the world.

- Don’t: I’m a hard worker.

- Do: Juggling rigorous academics with grueling morning soccer practices has taught me the value of hard work and discipline.

- Don’t: Climate change is a problem.

- Do: My generation is already suffering the real-time effects of climate change, like our snow days turning to smoke days as wildfires burn around our homes.

- Don’t: Please consider me.

- Do: As shown by the four years I volunteered at my local children’s hospital, community service is a priority for me in my future personal and professional life. Seeing what your university does for its surrounding neighborhood and the people there, I feel confident I would be a natural fit at your school.

- Don’t: You miss 100% of the shots you don't take.

- Do: In my wildest dreams, I never imagined I would be the lead in my senior play. Cut to now, and I’m singing my heart out to an applauding audience of parents and peers. From this moment forward, I will always understand and uphold the value of betting on yourself, even when you don’t know the outcome.

- Don’t: College will help me reach my dreams.

- Do: I’m enthusiastic about starting my next chapter—attending a school that will help me grow, learn, and take my next step toward my dream of becoming a doctor.

Expert Q&A

- Be specific in your essay—admissions officers want to hear about you and your life, so tell details about who you are and your experiences. [10] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Be authentic—admissions officers have read enough college essays to know when someone is phoning it in. Be true to yourself, write how you speak, and let your personality shine through. [11] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Show enthusiasm—if you’re talking about the school or your future, show excitement for what the next four years will hold for you. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

Thanks for reading our article! If you’d like to learn more about preparing for graduation, check out our in-depth interview with Alexander Ruiz, M.Ed. .

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/conclusions/

- ↑ https://www.collegeessayadvisors.com/write-amazing-closing-line/

- ↑ https://essaypro.com/blog/how-to-write-a-conclusion

- ↑ https://students.tippie.uiowa.edu/sites/students.tippie.uiowa.edu/files/2022-05/effective_claims.pdf

- ↑ https://www.rochester.edu/newscenter/how-to-write-your-best-college-application-essay-493692/

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

How To End A College Essay - 6+ Strategies, Tips & Examples

Reviewed by:

Former Admissions Committee Member, Columbia University

Reviewed: 1/16/24

Are you having trouble writing a conclusion for your college essay? Here’s how to end a college essay with expert tips and examples.

Writing the perfect ending for your college essay is no easy feat; it can be just as challenging as starting your college essay . But don’t fear - we’ve got you covered! This complete guide will discuss everything you need to know about how to end a college application essay. Follow along for tips, examples, and more.

Let’s get started!

How to End Your College Essay

After an energetic essay , it’s essential to end on a high note. Your conclusion should be clear, concise, and, most importantly - memorable. Since college admissions advisors read hundreds of essays, your conclusion will be the last bit they remember.

No matter what approach you take to the concluding paragraph, you’ll want to focus on the lesson learned. Think of the end of a great movie; what was it that gave you the warmth and fuzzies before the credits rolled? The ending should be impactful, moving, and nod toward the future.

Your ending shouldn't summarize the essay, repeat points that have already been made or taper off into nothingness. You don’t want it to just fade out–you want it to go out with a bang! Keeping it interesting at this stage can be challenging, but it can make or break a good college essay.

6 College Essay Endings Examples and Tips

Let’s go over some college application essay ending examples. Follow along to learn different powerful strategies you can use to end your college essay. If you want to explore even more essay examples, don't forget to check out our extensive College Essay Examples Database .

1. The Lesson Learned

One of the best things you can do in your college essay is demonstrate how you can get back up after getting knocked down. Showing the admissions committee how you’ve learned and grown from a challenging life event is an excellent way to present yourself as a strong candidate.

Think of this method as the ending of a good novel about a complex character: they’re not perfect, but they try to be better, and that’s what counts. In your college essay, you’re the main character of your story. Don’t be afraid to talk about a mistake you’ve made as long as you demonstrate (in your conclusion) that you learned something valuable.

Here’s an example of a college essay ending from a Harvard student using the “Lesson Learned” technique:

"The best thing that I took away from this experience is that I can't always control what happens to me, especially as a minor, but I can control how I handle things. In full transparency: there were still bad days and bad grades, but by taking action and adding a couple of classes into my schedule that I felt passionate about, I started feeling connected to school again. From there, my overall experience with school – and life in general – improved 100%."

Why It Works

This is a good example because it effectively demonstrates the "Lesson Learned" technique by showcasing personal growth and resilience.

The conclusion reflects on the experiences and challenges faced by the applicant, emphasizing the valuable lesson learned and the positive changes made as a result. It shows maturity, self-awareness, and the ability to overcome obstacles, which can leave a positive impression on admissions committees.

2. The Action-Packed Ending

Like you see in the movies, ending your college essay in the action can leave an impactful impression on the admissions committee. In the UMichigan example below, the student ends their essay on an ambiguous, energetic note by saying, “I never saw it coming,” as the last line.

You can also achieve this approach by ending your essay with dialogue or a description. For example, “Hi mom, I’m not coming home just yet,” or “I picked up my brother's phone, and dialed the number.” These are examples of endings that leave you “in the action”–dropping off the reader almost mid-story, leaving them intrigued.

Here is an example of an “action-packed” college essay ending from a UMichigan student .

"No foreign exchange trip could outdo that. I am a member of many communities based on my geography, ethnicity, interests, and talents, but the most meaningful community is the one that I never thought I would be a part of…

On that first bus ride to the Nabe, I never saw it coming.”

The example from the UMichigan student provides a strong ending to the college essay by using an "action-packed" approach. It engages the reader with an unexpected twist, creating intrigue and leaving them wanting more.

The phrase "I never saw it coming" adds a sense of anticipation and curiosity, making the conclusion memorable. This technique effectively leaves the reader with a lasting impression, showcasing the applicant's storytelling skills and ability to capture attention.

3. The Full Circle

As you may know, a “full circle” ending ties the story’s ending to the very beginning. Not to be confused with a summary, this method is an excellent way to leave a lasting impression on your reader.

When using this technique, tie the very first sentence with the very last. Avoid over-explaining yourself, and end with a very simple recall of the beginning of the story. Keep in mind if you use this method, your “full circle” should be straightforward and seamless, regardless of the essay topic .

Here is an example of a “Full Circle” college essay ending from a Duke student :

“So next time it rains, step outside. Close your eyes. Hear the symphony of millions of water droplets. And enjoy the moment.”

In response to the beginning:

“The pitter patter of droplets, the sweet smell that permeates throughout the air, the dark grey clouds that fill the sky, shielding me from the otherwise intense gaze of the sun, create a landscape unparalleled by any natural beauty.”

This example of a "Full Circle" college essay ending is effective because it masterfully connects the ending to the beginning of the story. The essay begins with a vivid description of a rainy day, and the conclusion seamlessly brings the reader back to that initial scene.

It emphasizes the importance of savoring the moment, creating a sense of reflection and unity in the narrative. This technique allows the reader to feel a sense of closure and reinforces the central theme of the essay, making it a strong and memorable conclusion.

4. The College Address

Directly addressing your college is a popular method, as it recalls the main reason you want to attend the school. If you choose to address your school, it is imperative to do your research. You should know precisely what you find attractive about the school, what it offers, and why it speaks to you.

Here is a college essay ending example using the “College Address” technique from a UMichigan Student:

"I want to join the University of Michigan’s legacy of innovators. I want to be part of the LSA community, studying economics and political science. I want to attend the Ford School and understand how policy in America and abroad has an effect on global poverty. I want to be involved with the Poverty Solutions Initiative, conducting groundbreaking research on the ways we can reform our financial system to better serve the lower and middle classes.”

This is a good example because it effectively utilizes the "College Address" technique. The student clearly articulates their specific intentions and aspirations related to the University of Michigan.

They showcase a deep understanding of the university's offerings and how these align with their academic and career goals. This kind of conclusion demonstrates genuine interest and a strong connection to the school, which can leave a positive impression on admissions committees.

5. The Look To the Future

Admissions committees want to know how attending their school will help you on your journey. To use this method, highlight your future goals at the end of your essay. You can highlight what made you want to go to this school in the first place and what you hope to achieve moving forward. If done correctly, this can be highly impactful.

Here is a college essay ending example from a med student using the “Look To the Future” technique:

“I want to tell my peers that doctors like my grandfather are not only healers in biology but healers in the spirit by the way he made up heroic songs for the children and sang the fear out of their hearts. I want to show my peers that patients are unique individuals who have suffered and sacrificed to trust us with their health care, so we must honor their trust by providing quality treatment and empathy.

My formative experiences in pediatrics contributed to my globally conscious mindset, and I look forward to sharing these diverse insights in my medical career.”

This is a good example because it effectively ties the applicant's personal experiences and aspirations to their desire to attend the specific school. It showcases a clear passion for medicine and a genuine desire to make a positive impact on patients' lives.

By highlighting the applicant's unique perspective gained from their experiences in pediatrics and emphasizing their commitment to providing quality care and empathy, it demonstrates a strong connection between their goals and the opportunities offered by the school.

This kind of conclusion helps the admissions committee understand how the applicant will contribute to the school's community and align with their future ambitions.

6. Learn What Not to Do

Admissions committees are unimpressed by clichéd and generic conclusions that fail to demonstrate an applicant's individuality or genuine interest in the institution. Unfortunately, many students fall into the trap of providing vague recaps of their academic journey without adding any unique insights or future aspirations.

Below is an example of such an unimpressive conclusion:

"In conclusion, I've learned a lot throughout my life, and I hope to continue learning in college. College will be a new chapter for me, and I'm excited to see where it takes me. I'm looking forward to the opportunities and experiences that lie ahead, and I can't wait to grow as a person. College is the next step in my journey, and I'm ready to embrace it with open arms."

Why It Doesn't Work

This is a bad example because it's overly generic and doesn't offer any specific insights or compelling reasons why the applicant is interested in the college. It simply states the obvious without adding any depth or uniqueness to the conclusion. Admissions committees are looking for applicants to stand out and showcase their genuine enthusiasm for the institution, which this conclusion fails to do. So, make sure to avoid essay topics that don’t genuinely excite you.

.jpg)

3 College Essay Endings to Avoid

You want your essay to have an impactful ending - but these methods may have the opposite impact. Now that you know some effective ways to end your college essay, let’s go over some methods to avoid.

1. The Summary

Remember that you’re writing a college essay, not a high school assignment you need to scrape through. Avoid simply summarizing the points you made during your essay. This method can come off as lazy and ultimately leave a negative impression on the admissions committee–or no impression at all. Instead, end the essay on a high note, with a point of action, or with your future goals.

2. The Famous Quote

Some students start their college essay with one, and some end it with one. Neither is a good idea. Avoid using a famous quote anywhere in your essay, as it can give the impression that you don’t know what to write. The admissions committee wants to get to know you –they already know the famous quotes.

Unless you’ve done a thorough research and are quoting someone affiliated with the school, you should avoid quotes altogether in your college essay.

3. The Needy Student

In your college essay conclusion, avoid begging for admission. You don’t want to come off desperate in your essay. Saying things like “Please consider me” or “I really want to attend” doesn’t say anything about you and doesn’t read smoothly. Instead, demonstrate who you are and how you’ve learned and grown in your life. Focus on you, not them!

Tips and Strategies on How to Approach Essay’s Conclusion

When it comes to nailing your college essay's conclusion, here are some practical tips to keep in mind:

- Sum It Up : Start by summarizing the main points you've discussed in your essay. You don't need to rehash everything, but provide a brief recap to remind the reader of your journey.

- Avoid Repetition : While summarizing is essential, avoid repeating verbatim what you've already said. Instead, aim to offer a fresh perspective or a new angle on your experiences.

- Look to the Future : Connect your past experiences with your future aspirations. Explain how attending this particular college aligns with your goals and ambitions. Admissions committees appreciate candidates who have a clear vision.

- Get Specific : Be as specific as possible. Use anecdotes and personal details to make your conclusion vivid and memorable. Show, don't just tell.

- Reflect on Personal Growth : Offer insights into how your experiences have shaped you as an individual. Highlight the lessons you've learned and the personal growth you've achieved.

- Show Your Enthusiasm : Let your passion for the college shine through. Convey why this institution is the right fit for you, emphasizing unique aspects that resonate with your goals and interests.

- End with Impact : Finish strong with a closing sentence that leaves a lasting impression. It could be a thought-provoking question, a call to action, or a memorable quote. Make sure it lingers in the reader's mind.

Your college essay's conclusion is your chance to make a final pitch. It should reinforce your suitability for the college and leave a strong, positive impression on the admissions committee. So, take your time and craft it carefully—it's worth the effort.

FAQs: How to End a College Essay

Here are some answers to frequently asked questions about how to end a college application essay.

1. How Do You Conclude a College Essay?

The end of your college essay should be strong, clear, and impactful. You can talk about your future goals, end in a moment of action, talk about what you’ve learned, or go full circle. Whatever method you choose, make sure to avoid summarizing your essay.

2. What Is a Good Closing Sentence?

A good closing sentence on your college essay is impactful, meaningful, and makes the reader think. You’ll want to ensure the reader remembers your essay, so conclude with something unique that ends your story with a bang.

3. What Words Can You Use to End an Essay?

Avoid saying “to conclude,” “to summarize,” or “finally.” Your essay should end on a high note, like the ending of a movie. Think of moving sentences such as “I never saw it coming,” “I’ll always remember what happened,” or “I’ve learned so much since then.”

Final Thoughts

By following our tips, you should be on track to write a stellar college essay with an impactful ending. Think of what you’ve learned, what you’ll do in the future, and where you can end the story that would leave a lasting impression.

If you’re still having a hard time ending your college essay, you can always contact an admissions expert or tutor to help guide you through the process.

Good luck with your essay!

Access 190+ sample college essays here

Get A Free Consultation

You may also like.

Princeton vs. Harvard: Which College to Choose?

How to Get Into Wake Forest University: Admission Guide

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

5 Examples of Concluding Words for Essays

4-minute read

- 19th September 2022

If you’re a student writing an essay or research paper, it’s important to make sure your points flow together well. You’ll want to use connecting words (known formally as transition signals) to do this. Transition signals like thus , also , and furthermore link different ideas, and when you get to the end of your work, you need to use these to mark your conclusion. Read on to learn more about transition signals and how to use them to conclude your essays.

Transition Signals

Transition signals link sentences together cohesively, enabling easy reading and comprehension. They are usually placed at the beginning of a sentence and separated from the remaining words with a comma. There are several types of transition signals, including those to:

● show the order of a sequence of events (e.g., first, then, next)

● introduce an example (e.g., specifically, for instance)

● indicate a contrasting idea (e.g., but, however, although)

● present an additional idea (e.g., also, in addition, plus)

● indicate time (e.g., beforehand, meanwhile, later)

● compare (e.g., likewise, similarly)

● show cause and effect (e.g., thus, as a result)

● mark the conclusion – which we’ll focus on in this guide.

When you reach the end of an essay, you should start the concluding paragraph with a transition signal that acts as a bridge to the summary of your key points. Check out some concluding transition signals below and learn how you can use them in your writing.

To Conclude…

This is a particularly versatile closing statement that can be used for almost any kind of essay, including both formal and informal academic writing. It signals to the reader that you will briefly restate the main idea. As an alternative, you can begin the summary with “to close” or “in conclusion.” In an argumentative piece, you can use this phrase to indicate a call to action or opinion:

To conclude, Abraham Lincoln was the best president because he abolished slavery.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

As Has Been Demonstrated…

To describe how the evidence presented in your essay supports your argument or main idea, begin the concluding paragraph with “as has been demonstrated.” This phrase is best used for research papers or articles with heavy empirical or statistical evidence.

As has been demonstrated by the study presented above, human activities are negatively altering the climate system.

The Above Points Illustrate…

As another transitional phrase for formal or academic work, “the above points illustrate” indicates that you are reiterating your argument and that the conclusion will include an assessment of the evidence you’ve presented.

The above points illustrate that children prefer chocolate over broccoli.

In a Nutshell…

A simple and informal metaphor to begin a conclusion, “in a nutshell” prepares the reader for a summary of your paper. It can work in narratives and speeches but should be avoided in formal situations.

In a nutshell, the Beatles had an impact on musicians for generations to come.

Overall, It Can Be Said…

To recap an idea at the end of a critical or descriptive essay, you can use this phrase at the beginning of the concluding paragraph. “Overall” means “taking everything into account,” and it sums up your essay in a formal way. You can use “overall” on its own as a transition signal, or you can use it as part of a phrase.

Overall, it can be said that art has had a positive impact on humanity.

Proofreading and Editing

Transition signals are crucial to crafting a well-written and cohesive essay. For your next writing assignment, make sure you include plenty of transition signals, and check out this post for more tips on how to improve your writing. And before you turn in your paper, don’t forget to have someone proofread your work. Our expert editors will make sure your essay includes all the transition signals necessary for your writing to flow seamlessly. Send in a free 500-word sample today!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

What is market research.

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

3-minute read

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

The 5 Best Ecommerce Website Design Tools

A visually appealing and user-friendly website is essential for success in today’s competitive ecommerce landscape....

The 7 Best Market Research Tools in 2024

Market research is the backbone of successful marketing strategies. To gain a competitive edge, businesses...

Google Patents: Tutorial and Guide

Google Patents is a valuable resource for anyone who wants to learn more about patents, whether...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

17 Essay Conclusion Examples (Copy and Paste)

Essay conclusions are not just extra filler. They are important because they tie together your arguments, then give you the chance to forcefully drive your point home.

I created the 5 Cs conclusion method to help you write essay conclusions:

I’ve previously produced the video below on how to write a conclusion that goes over the above image.

The video follows the 5 C’s method ( you can read about it in this post ), which doesn’t perfectly match each of the below copy-and-paste conclusion examples, but the principles are similar, and can help you to write your own strong conclusion:

💡 New! Try this AI Prompt to Generate a Sample 5Cs Conclusion This is my essay: [INSERT ESSAY WITHOUT THE CONCLUSION]. I want you to write a conclusion for this essay. In the first sentence of the conclusion, return to a statement I made in the introduction. In the second sentence, reiterate the thesis statement I have used. In the third sentence, clarify how my final position is relevant to the Essay Question, which is [ESSAY QUESTION]. In the fourth sentence, explain who should be interested in my findings. In the fifth sentence, end by noting in one final, engaging sentence why this topic is of such importance.

Remember: The prompt can help you generate samples but you can’t submit AI text for assessment. Make sure you write your conclusion in your own words.

Essay Conclusion Examples

Below is a range of copy-and-paste essay conclusions with gaps for you to fill-in your topic and key arguments. Browse through for one you like (there are 17 for argumentative, expository, compare and contrast, and critical essays). Once you’ve found one you like, copy it and add-in the key points to make it your own.

1. Argumentative Essay Conclusions

The arguments presented in this essay demonstrate the significant importance of _____________. While there are some strong counterarguments, such as ____________, it remains clear that the benefits/merits of _____________ far outweigh the potential downsides. The evidence presented throughout the essay strongly support _____________. In the coming years, _____________ will be increasingly important. Therefore, continual advocacy for the position presented in this essay will be necessary, especially due to its significant implications for _____________.

Version 1 Filled-In

The arguments presented in this essay demonstrate the significant importance of fighting climate change. While there are some strong counterarguments, such as the claim that it is too late to stop catastrophic change, it remains clear that the merits of taking drastic action far outweigh the potential downsides. The evidence presented throughout the essay strongly support the claim that we can at least mitigate the worst effects. In the coming years, intergovernmental worldwide agreements will be increasingly important. Therefore, continual advocacy for the position presented in this essay will be necessary, especially due to its significant implications for humankind.

As this essay has shown, it is clear that the debate surrounding _____________ is multifaceted and highly complex. While there are strong arguments opposing the position that _____________, there remains overwhelming evidence to support the claim that _____________. A careful analysis of the empirical evidence suggests that _____________ not only leads to ____________, but it may also be a necessity for _____________. Moving forward, _____________ should be a priority for all stakeholders involved, as it promises a better future for _____________. The focus should now shift towards how best to integrate _____________ more effectively into society.

Version 2 Filled-In

As this essay has shown, it is clear that the debate surrounding climate change is multifaceted and highly complex. While there are strong arguments opposing the position that we should fight climate change, there remains overwhelming evidence to support the claim that action can mitigate the worst effects. A careful analysis of the empirical evidence suggests that strong action not only leads to better economic outcomes in the long term, but it may also be a necessity for preventing climate-related deaths. Moving forward, carbon emission mitigation should be a priority for all stakeholders involved, as it promises a better future for all. The focus should now shift towards how best to integrate smart climate policies more effectively into society.

Based upon the preponderance of evidence, it is evident that _____________ holds the potential to significantly alter/improve _____________. The counterarguments, while noteworthy, fail to diminish the compelling case for _____________. Following an examination of both sides of the argument, it has become clear that _____________ presents the most effective solution/approach to _____________. Consequently, it is imperative that society acknowledge the value of _____________ for developing a better _____________. Failing to address this topic could lead to negative outcomes, including _____________.

Version 3 Filled-In

Based upon the preponderance of evidence, it is evident that addressing climate change holds the potential to significantly improve the future of society. The counterarguments, while noteworthy, fail to diminish the compelling case for immediate climate action. Following an examination of both sides of the argument, it has become clear that widespread and urgent social action presents the most effective solution to this pressing problem. Consequently, it is imperative that society acknowledge the value of taking immediate action for developing a better environment for future generations. Failing to address this topic could lead to negative outcomes, including more extreme climate events and greater economic externalities.

See Also: Examples of Counterarguments

On the balance of evidence, there is an overwhelming case for _____________. While the counterarguments offer valid points that are worth examining, they do not outweigh or overcome the argument that _____________. An evaluation of both perspectives on this topic concludes that _____________ is the most sufficient option for _____________. The implications of embracing _____________ do not only have immediate benefits, but they also pave the way for a more _____________. Therefore, the solution of _____________ should be actively pursued by _____________.

Version 4 Filled-In

On the balance of evidence, there is an overwhelming case for immediate tax-based action to mitigate the effects of climate change. While the counterarguments offer valid points that are worth examining, they do not outweigh or overcome the argument that action is urgently necessary. An evaluation of both perspectives on this topic concludes that taking societal-wide action is the most sufficient option for achieving the best results. The implications of embracing a society-wide approach like a carbon tax do not only have immediate benefits, but they also pave the way for a more healthy future. Therefore, the solution of a carbon tax or equivalent policy should be actively pursued by governments.

2. Expository Essay Conclusions

Overall, it is evident that _____________ plays a crucial role in _____________. The analysis presented in this essay demonstrates the clear impact of _____________ on _____________. By understanding the key facts about _____________, practitioners/society are better equipped to navigate _____________. Moving forward, further exploration of _____________ will yield additional insights and information about _____________. As such, _____________ should remain a focal point for further discussions and studies on _____________.

Overall, it is evident that social media plays a crucial role in harming teenagers’ mental health. The analysis presented in this essay demonstrates the clear impact of social media on young people. By understanding the key facts about the ways social media cause young people to experience body dysmorphia, teachers and parents are better equipped to help young people navigate online spaces. Moving forward, further exploration of the ways social media cause harm will yield additional insights and information about how it can be more sufficiently regulated. As such, the effects of social media on youth should remain a focal point for further discussions and studies on youth mental health.

To conclude, this essay has explored the multi-faceted aspects of _____________. Through a careful examination of _____________, this essay has illuminated its significant influence on _____________. This understanding allows society to appreciate the idea that _____________. As research continues to emerge, the importance of _____________ will only continue to grow. Therefore, an understanding of _____________ is not merely desirable, but imperative for _____________.

To conclude, this essay has explored the multi-faceted aspects of globalization. Through a careful examination of globalization, this essay has illuminated its significant influence on the economy, cultures, and society. This understanding allows society to appreciate the idea that globalization has both positive and negative effects. As research continues to emerge, the importance of studying globalization will only continue to grow. Therefore, an understanding of globalization’s effects is not merely desirable, but imperative for judging whether it is good or bad.

Reflecting on the discussion, it is clear that _____________ serves a pivotal role in _____________. By delving into the intricacies of _____________, we have gained valuable insights into its impact and significance. This knowledge will undoubtedly serve as a guiding principle in _____________. Moving forward, it is paramount to remain open to further explorations and studies on _____________. In this way, our understanding and appreciation of _____________ can only deepen and expand.

Reflecting on the discussion, it is clear that mass media serves a pivotal role in shaping public opinion. By delving into the intricacies of mass media, we have gained valuable insights into its impact and significance. This knowledge will undoubtedly serve as a guiding principle in shaping the media landscape. Moving forward, it is paramount to remain open to further explorations and studies on how mass media impacts society. In this way, our understanding and appreciation of mass media’s impacts can only deepen and expand.

In conclusion, this essay has shed light on the importance of _____________ in the context of _____________. The evidence and analysis provided underscore the profound effect _____________ has on _____________. The knowledge gained from exploring _____________ will undoubtedly contribute to more informed and effective decisions in _____________. As we continue to progress, the significance of understanding _____________ will remain paramount. Hence, we should strive to deepen our knowledge of _____________ to better navigate and influence _____________.

In conclusion, this essay has shed light on the importance of bedside manner in the context of nursing. The evidence and analysis provided underscore the profound effect compassionate bedside manner has on patient outcome. The knowledge gained from exploring nurses’ bedside manner will undoubtedly contribute to more informed and effective decisions in nursing practice. As we continue to progress, the significance of understanding nurses’ bedside manner will remain paramount. Hence, we should strive to deepen our knowledge of this topic to better navigate and influence patient outcomes.

See More: How to Write an Expository Essay

3. Compare and Contrast Essay Conclusion

While both _____________ and _____________ have similarities such as _____________, they also have some very important differences in areas like _____________. Through this comparative analysis, a broader understanding of _____________ and _____________ has been attained. The choice between the two will largely depend on _____________. For example, as highlighted in the essay, ____________. Despite their differences, both _____________ and _____________ have value in different situations.

While both macrosociology and microsociology have similarities such as their foci on how society is structured, they also have some very important differences in areas like their differing approaches to research methodologies. Through this comparative analysis, a broader understanding of macrosociology and microsociology has been attained. The choice between the two will largely depend on the researcher’s perspective on how society works. For example, as highlighted in the essay, microsociology is much more concerned with individuals’ experiences while macrosociology is more concerned with social structures. Despite their differences, both macrosociology and microsociology have value in different situations.

It is clear that _____________ and _____________, while seeming to be different, have shared characteristics in _____________. On the other hand, their contrasts in _____________ shed light on their unique features. The analysis provides a more nuanced comprehension of these subjects. In choosing between the two, consideration should be given to _____________. Despite their disparities, it’s crucial to acknowledge the importance of both when it comes to _____________.

It is clear that behaviorism and consructivism, while seeming to be different, have shared characteristics in their foci on knowledge acquisition over time. On the other hand, their contrasts in ideas about the role of experience in learning shed light on their unique features. The analysis provides a more nuanced comprehension of these subjects. In choosing between the two, consideration should be given to which approach works best in which situation. Despite their disparities, it’s crucial to acknowledge the importance of both when it comes to student education.

Reflecting on the points discussed, it’s evident that _____________ and _____________ share similarities such as _____________, while also demonstrating unique differences, particularly in _____________. The preference for one over the other would typically depend on factors such as _____________. Yet, regardless of their distinctions, both _____________ and _____________ play integral roles in their respective areas, significantly contributing to _____________.

Reflecting on the points discussed, it’s evident that red and orange share similarities such as the fact they are both ‘hot colors’, while also demonstrating unique differences, particularly in their social meaning (red meaning danger and orange warmth). The preference for one over the other would typically depend on factors such as personal taste. Yet, regardless of their distinctions, both red and orange play integral roles in their respective areas, significantly contributing to color theory.

Ultimately, the comparison and contrast of _____________ and _____________ have revealed intriguing similarities and notable differences. Differences such as _____________ give deeper insights into their unique and shared qualities. When it comes to choosing between them, _____________ will likely be a deciding factor. Despite these differences, it is important to remember that both _____________ and _____________ hold significant value within the context of _____________, and each contributes to _____________ in its own unique way.

Ultimately, the comparison and contrast of driving and flying have revealed intriguing similarities and notable differences. Differences such as their differing speed to destination give deeper insights into their unique and shared qualities. When it comes to choosing between them, urgency to arrive at the destination will likely be a deciding factor. Despite these differences, it is important to remember that both driving and flying hold significant value within the context of air transit, and each contributes to facilitating movement in its own unique way.

See Here for More Compare and Contrast Essay Examples

4. Critical Essay Conclusion

In conclusion, the analysis of _____________ has unveiled critical aspects related to _____________. While there are strengths in _____________, its limitations are equally telling. This critique provides a more informed perspective on _____________, revealing that there is much more beneath the surface. Moving forward, the understanding of _____________ should evolve, considering both its merits and flaws.

In conclusion, the analysis of flow theory has unveiled critical aspects related to motivation and focus. While there are strengths in achieving a flow state, its limitations are equally telling. This critique provides a more informed perspective on how humans achieve motivation, revealing that there is much more beneath the surface. Moving forward, the understanding of flow theory of motivation should evolve, considering both its merits and flaws.

To conclude, this critical examination of _____________ sheds light on its multi-dimensional nature. While _____________ presents notable advantages, it is not without its drawbacks. This in-depth critique offers a comprehensive understanding of _____________. Therefore, future engagements with _____________ should involve a balanced consideration of its strengths and weaknesses.

To conclude, this critical examination of postmodern art sheds light on its multi-dimensional nature. While postmodernism presents notable advantages, it is not without its drawbacks. This in-depth critique offers a comprehensive understanding of how it has contributed to the arts over the past 50 years. Therefore, future engagements with postmodern art should involve a balanced consideration of its strengths and weaknesses.

Upon reflection, the critique of _____________ uncovers profound insights into its underlying intricacies. Despite its positive aspects such as ________, it’s impossible to overlook its shortcomings. This analysis provides a nuanced understanding of _____________, highlighting the necessity for a balanced approach in future interactions. Indeed, both the strengths and weaknesses of _____________ should be taken into account when considering ____________.

Upon reflection, the critique of marxism uncovers profound insights into its underlying intricacies. Despite its positive aspects such as its ability to critique exploitation of labor, it’s impossible to overlook its shortcomings. This analysis provides a nuanced understanding of marxism’s harmful effects when used as an economic theory, highlighting the necessity for a balanced approach in future interactions. Indeed, both the strengths and weaknesses of marxism should be taken into account when considering the use of its ideas in real life.

Ultimately, this critique of _____________ offers a detailed look into its advantages and disadvantages. The strengths of _____________ such as __________ are significant, yet its limitations such as _________ are not insignificant. This balanced analysis not only offers a deeper understanding of _____________ but also underscores the importance of critical evaluation. Hence, it’s crucial that future discussions around _____________ continue to embrace this balanced approach.

Ultimately, this critique of artificial intelligence offers a detailed look into its advantages and disadvantages. The strengths of artificial intelligence, such as its ability to improve productivity are significant, yet its limitations such as the possibility of mass job losses are not insignificant. This balanced analysis not only offers a deeper understanding of artificial intelligence but also underscores the importance of critical evaluation. Hence, it’s crucial that future discussions around the regulation of artificial intelligence continue to embrace this balanced approach.

This article promised 17 essay conclusions, and this one you are reading now is the twenty-first. This last conclusion demonstrates that the very best essay conclusions are written uniquely, from scratch, in order to perfectly cater the conclusion to the topic. A good conclusion will tie together all the key points you made in your essay and forcefully drive home the importance or relevance of your argument, thesis statement, or simply your topic so the reader is left with one strong final point to ponder.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- SAT BootCamp

- SAT MasterClass

- SAT Private Tutoring

- SAT Proctored Practice Test

- ACT Private Tutoring

- Academic Subjects

- College Essay Workshop

- Academic Writing Workshop

- AP English FRQ BootCamp

- 1:1 College Essay Help

- Online Instruction

- Free Resources

How to end a college essay

How to end your college application essay (with examples).

Bonus Material: PrepMaven’s 30 College Essays That Worked

We’ve all been there: you’ve just about finished creating a brilliant, gripping piece of writing. All that’s left is to wrap it up with the perfect ending…but how do you give your essay the kind of ending that sticks with the reader, that wraps everything up neatly?

With college application essays, the stakes are even higher: the right ending can ensure you stand out from the thousands of other applicants and wow admissions officers.

At PrepMaven, we’ve helped thousands of students do just that: create compelling, memorable admissions essays that land them acceptances at top-tier universities.

In this post, we’ll specifically break down how to put those finishing touches on your Common App essay (or any other personal essay), providing examples so you can see exactly how each technique works.

You can also feel free to hit the button below to download a free collection of 30 successful essays that worked, many of which provide great examples of these very strategies.

Download 30 College Essays That Worked

Jump to section: Necessary elements of a college essay ending Reflect Connect to your narrative Look ahead to college 3 specific ways to end your college essay (with examples!) The full-circle callback The return with a difference The statement of purpose Next Steps

Necessary elements of a college essay ending

In this section of the post, we’ll cover the beats that every college essay ending should hit to be maximally successful. Later, we’ll show you specific tricks for ending the essay–structures that you can easily integrate into your own writing. If you’d like to jump there, click here: specific ways to end your college essay .

Regardless of which specific technique you use to wrap up your essay, though, it should still help you accomplish the key things we list below. The fact is, college admissions counselors are really looking for pretty specific things in these essays.

Whatever the structure, tone, or style of your admissions essay, you should be sure that the conclusion does all of the following:

Connect to your narrative

Look ahead to college.

If you’ve read our other posts on how to structure your application essay or how to start it , you probably already know a big part of your personal statement should involve a story.

But it can’t be just a story: just as important is an element of reflection, which is best developed at the conclusion of your essay.

What do we mean by reflection? Simply put, you need to think through the story you’ve laid out throughout the entire essay and articulate what it says about you, why it matters. In essence, the reflection is your answer to the question, “So what?”

For example, if you write an essay about giving up professional dance, your reflection might be about how that choice led you to view dance differently, perhaps as something that you can value independently regardless of whether you pursue it as a career. You might then expand that reflection to other elements of your life: did that changed viewpoint also apply to how you view academics, the arts, or other extracurriculars?

Or say you wrote an essay about overcoming an obstacle to your education. Your reflection might then touch on how this process shaped your thinking, altered how you view challenges, or led you to develop a particular approach to academics and schoolwork.

The key here is that you really show us the process of you thinking through the important changes/lessons/etc. at play in your essay. It’s not enough to just say, “This is important because X.” Admissions committees want to see you actually think through this. Real realizations don’t usually happen in an instant: you should question and consider, laying your thoughts out on paper.

Rhetorical questions are often a great way to do this, as is narrating the thought process you underwent while overcoming the obstacle, learning the lesson, or whatever your story might be.

A suggestion we often give our students is to read over the story you’ve written, and ask yourself what it means to you, what lessons you can take from it. As you ask and answer those questions, put those onto the page and work through them in writing. You can always clean it up and make it more presentable later.

Below, we’ve selected the conclusion from Essay 2 in our collection of 30 Essays that Worked . In that essay, the writer spends most of the intro and body discussing their love for hot sauce and all things spicy, as well as how they’ve pursued that passion. Take a look at how they end their essay:

I’m not sure what it is about spiciness that intrigues me. Maybe my fungiform papillae are mapped out in a geography uniquely designed to appreciate bold seasonings. Maybe these taste buds are especially receptive to the intricacies of the savors and zests that they observe. Or maybe it’s simply my burning sense of curiosity. My desire to challenge myself, to stimulate my mind, to experience the fullness of life in all of its varieties and flavors.

In that example, the student doesn’t just tell us “the lesson.” Instead, we get to see them actively working through what the story they’ve told means and why it matters by offering potential ways it’s shaped them. Notice that it’s perfectly okay for the student not to have one clear “answer;” it actually works even better, in this case, that the student is wondering, thinking, still figuring things out.

That’s reflection, and every good college application essay does it in one form or another.

Who, on paper, are you? We know–it’s a brutal question to try to answer. That’s what these essays are all about, though, and these college essay conclusions are the perfect place to tie everything together.

Now, this doesn’t mean you should try to cram elements of your resume or transcript into the end of your essay–please don’t! When we say the conclusion should “connect to your narrative,” we mean that you should write it while bearing in mind the other aspects of your application the admissions committee will be looking at.

So, the conclusion of your college essay should work to connect the story and reflection you’ve developed with the broader picture of you as a college applicant. In a way, this goes hand in hand with reflection: you want your conclusion to tie all these threads together, explaining why this all matters in the context of college applications.

You might, as in the above “hot sauce” essay example, allude to an element of your personality/mentality that your personal statement exemplifies. In that example, we can clearly see the writer showing off some scientific knowledge (“fungiform papillae”) while also highlighting their “curiosity” and desire to challenge themselves.

This helps the reader see what this whole story is meant to tell us about the applicant, connecting to who they are and what they’re looking for.

Or, you might connect this reflection to your academic goals. Or else you could connect elements of your story and reflection to some passion evident in the rest of your application. Often, the best essays involve a mix of all of these connections, but there’s no “right” or “wrong” connection to make, so long as it develops convincingly from the story you’ve told.

There are numerous ways to go here, and it doesn’t have to be super heavy-handed or to take up much real estate. Simply bear in mind that these essays gain an additional sense of balance when they resonate with other elements of your broader high school narrative.

Though it’s true these college essays are, in part, ways to demonstrate your writing skills and ability to respond concisely to a complicated essay prompt, their primary purpose is to show a college admissions counselor why you’re a good fit for their college.

So, a strong college essay ending should draw strong connections to your future as (hopefully) a college student. As with the previous point, this is one that you don’t need to go over the top with! Don’t take away from your story by suddenly telling us how smart you are and what great grades you’ll get.

Instead, you might want to suggest how the experiences you write about have prepared you for college–or, even better, how they’ve shaped what you hope to get out of the next four years.

Generally, this is a small and subtle part of your conclusion: it might be a sentence, or it might even be the kind of thing that you imply without stating directly. The idea is that a college admissions officer reading your essay will walk away with some idea of why you’d be a good fit for college in general.

In the example we quoted above, the essay does this fairly subtly: by describing their desire to challenge themselves and stimulate their mind, the writer is clearly alluding to the exact kinds of things college is for, even if they don’t come right out and say it.

A successful college conclusion will contain all three of these elements. You can find thirty fantastic examples of such conclusions in the sample college essays below.

Read on for 3 specific techniques to end your college admissions essay.

3 Specific ways to end your college essay (with examples!)

Each of the essay endings we cover below is designed to help your essay develop a sense of closure while simultaneously accomplishing all of those tricky things it needs to do to wow admissions officers.

While all of these endings have been proven to work countless times, how you incorporate them and which you choose matters–a lot!

Because every student’s essay is (or at least should be) unique, we recommend getting a trusted advisor to offer guidance on how to wrap up your essay. You can get paired up with one of our expert tutors quickly by contacting us here .

Now, for the techniques.

The full-circle callback

This is probably the most classic ending structure for college essays, and with good reasons. The premise is simple: your essay’s conclusion will return to the image, story, or idea that your essay began with.

Take a look at the below example, which includes just the first and last paragraphs of Essay 12 from our collection of 30 essays that worked . In this essay, the writer uses a discussion of food to explore their integration into American society as a Russian immigrant.