2a. Critical Reading

An introduction to reading in college.

While the best way to develop your skills as a writer is to actually practice by writing, practicing critical reading skills is crucial to becoming a better college writer. Careful and skilled readers develop a stronger understanding of topics, learn to better anticipate the needs of the audience, and pick up sophisticated writing “maneuvers” and strategies from professional writing. A good reading practice requires reading text and context, which you’ll learn more about in the next section. Writing a successful academic essay also begins with critical reading as you explore ideas and consider how to make use of sources to provide support for your writing.

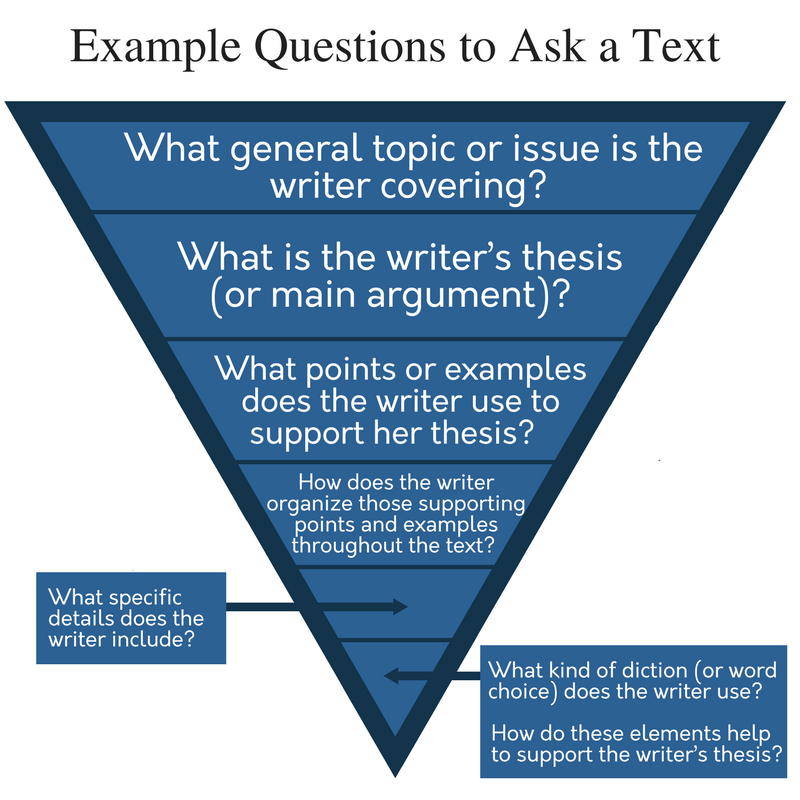

Questions to ask as you read

If you consider yourself a particularly strong reader or want to improve your reading comprehension skills, writing out notes about a text—even if it’s in shorthand—helps you to commit the answers to memory more easily. Even if you don’t write out all these notes, answering these basic questions about any text or reading you encounter in college will help you get the most out of the time you put into your reading. It will also give you more confidence to understand and question the text while you read.

- Is there context provided about the author and/or essay? If so, what stands out as important?

Context in this instance means things like dates of publication, where the piece was originally published, and any biographical information about the author. All of that information will be important for developing a critical reading of the piece, so track what’s available as you read.

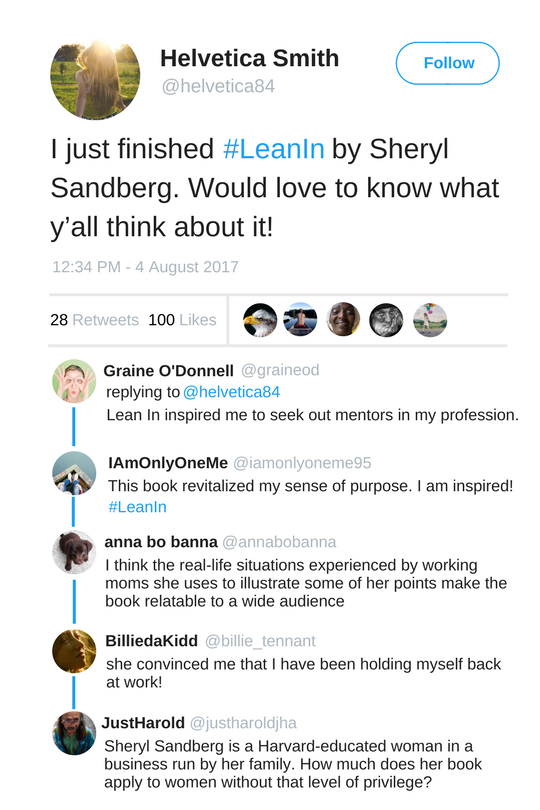

- If you had to guess, who is the author’s intended audience ? Describe them in as much detail as possible.

Sometimes the author will state who the audience is, but sometimes you have to figure it out by context clues, such as those you tracked above. For instance, the audience for a writer on Buzzfeed is very different from the audience for a writer for the Wall Street Journal —and both writers know that, which means they’re more effective at reaching their readers. Learning how to identify your audience is a crucial writing skill for all genres of writing.

- In your own words, what is the question the author is trying to answer in this piece? What seems to have caused them to write in the first place?

In nonfiction writing of the kind we read in Writing 121, writers set out to answer a question. Their thesis/main argument is usually the answer to the question, so sometimes you can “reverse engineer” the question from that. Often, the question is asked in the title of the piece.

- In your own words, what’s the author’s main idea or argument ? If you had to distill it down to one or two sentences, what does the author want you, the reader, to agree with?

If you’ve ever had to write a paper for a class, you’re probably familiar with a thesis or main argument. Published writers also have a thesis (or else they don’t get published!), but sometimes it can be tricky to find in a more sophisticated piece of writing. Trying to put the main argument into your own words can help.

- How many examples and types of evidence did the author provide to support the main argument? Which examples/evidence stood out to you as persuasive?

It’s never enough to just make a claim and expect people to believe it—we have to support that claim with evidence. The types of evidence and examples that will be persuasive to readers depends on the audience, though, which is why it’s important to have some idea of your readers and their expectations.

- Did the author raise any points of skepticism (also known as counterarguments)? Can you identify exactly what page or paragraph where the author does this?

As we’ll see later when the writing process, respectfully engaging with points of skepticism and counterarguments builds trust with the reader because it shows that the writer has thought about the issue from multiple perspectives before arriving at the main argument. Raising a counterargument is not enough, though. Pay careful attention to how the writer responds to that counterargument—is it an effective and persuasive response? If not, perhaps the counterargument has more merit for you than the author’s main argument.

- In your own words, how does the essay conclude ? What does the author “want” from us, the readers?

A conclusion usually offers a brief summary of the main argument and some kind of “what’s next?” appeal from the writer to the audience. The “what’s next?” appeal can take many forms, but it’s usually a question for readers to ponder, actions the author thinks people should take, or areas related to the main topic that need more investigation or research. When you read the conclusion, ask yourself, “What does the author want from me now that I’ve read their essay?”

Reading Like Writers: Critical Reading

Reading as a creative act.

“The theory of books is noble. The scholar of the first age received into him the world around; brooded thereon; gave it the new arrangement of his own mind, and uttered it again. It came into him life; it went out from him truth. It came to him short-lived actions; it went out from him immortal thoughts. It came to him business; it went from him poetry. It was dead fact; now, it is quick thought. It can stand, and it can go. It now endures, it now flies, it now inspires. Precisely in proportion to the depth of mind from which it issued, so high does it soar, so long does it sing.” ~Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The American Scholar”

- Consider the discourse community when you read and write in your college classes

- Analyze any reading for text and context

- Read like a writer so you can write for your readers

By the end of this lesson, you’ll be able to apply the concept of discourse community to honing your college-level critical reading skills.

Good writers are good readers, so let’s start there. When you can confidently identify the audience, context, and purpose of a text —position it within its discourse community—you’ll be a stronger, savvier reader.

Strong, savvy readers are more effective writers because they consider their own audience, context, and purpose when they write and communicate, which makes their writing clearer and to the point.

So the goal of this lesson is to help you read like a writer!

The Savvy Reader

Good writers are good readers! And good readers. . .

- get to know the author

- get to know the author’s community + audience

- accurately summarize the author’s argument

- look up terms you don’t know

- “listen” respectfully to the author’s point of view

- have a sense of the larger conversation

- think about other issues related to the conversation

- put it in current context

- analyze and assess the author’s reasoning, evidence, and assumptions

Why read critically? While the best way to develop your skills as a writer is to actually practice by writing, practicing critical reading skills is crucial to becoming a better writer. Careful and skilled readers develop a stronger understanding of topics, learn to better anticipate the needs of the audience, and pick up writing “maneuvers” and strategies from professional writing.

Reading Like Writers

How do you read like a writer? When you read like a writer, you are practicing deeper reading comprehension. In order to understand a text, you are reading not just what’s in it but what’s around it, too: text and context.

Practice: Reading Like Writers

In-class discussion : Advertisements are helpful for practicing reading like writers because advertisers make deliberate choices with text and images based on audience (target consumer), context (where they are reaching them), and purpose (buy this product).

- But I’m not trying to sell a product! How can I use my newfound understanding of audience, context, and purpose to improve my writing?

It’s true! You aren’t selling a product. You aren’t (I hope) trying to manipulate your audience. You aren’t relying on discriminatory assumptions or stereotypes to appeal to your audience. But when you write, let’s say, an essay, you are asking readers to “buy into” your point of view. The goal doesn’t have to be for them to agree with you; it can be for your readers to respectfully consider, understand, or sympathize with your point of view or analysis of an issue. The point is you’re thinking of your reader when you write, and that will make your writing process smoother and your writing clearer.

Writing for Your Readers

When you write for your readers, you. . .

- Learn from your reading and communication experience: What makes texts work? How are ideas conveyed clearly?

- Analyze the writing situation: What are the goals and purpose for a writing project? Who is your audience?

- Explore and play as you draft: What are different ways to respond? Can you use a better word or phrase?

- Consider your audience: What might a reader expect to see? What does your reader need to understand your point of view? What questions might a reader have?

Writing as a process of inquiry

Just as you want your readers to take you seriously, you want to approach texts with an open and curious mind. Whatever the topic, it was important enough for this person to want to write on it. While we don’t have to agree with the point someone is making, we can respect their opinion and appreciate reading a different perspective.

Approach reading and writing in college in a learning zone. Be open, be curious, ask questions, seek answers. Share, stretch, experiment.

Guides and Worksheets

- Use this guide for any of your college reading!

- Learn a basic study skill–annotating or taking notes on your readings

Critical Reading Guide: Text + Context

Title of the text: Author:

Reading the text: Comprehension

Main idea . In one sentence, summarize the main point or argument of the text.

Claim . Identify one claim in the text.

Key points . Paraphrase a key point, example, or passage that interested you.

Evidence . In your own words, describe 1-2 compelling examples or pieces of evidence that support the point/argument of the text.

Conclusion . What is the ultimate takeaway the text gives us on the topic/issue?

Personal experience . What is your experience of the topic? Have you had problems related to it?

Vocabulary . What is a word or phrase in the text you didn’t know? Look it up. What does it mean?

Inquiry . What is one thing you need more information about? Or, what is one question you have about the content of the text?

Reading for context: Rhetorical analysis

The author . Do an internet search on the author. What did you find out?

Ethos . Do you trust the author on the topic/issue? Why or why not?

Container . When and where was the text first published? Who will read/see it?

Audience . How does the author address or appeal to their readers? What tone does the author use in the text?

Bias . What knowledge, values, or beliefs does the author assume the reader shares?

Types of evidence . What types of evidence does the author use? Types of evidence include facts, examples, statistics, statements by authorities (references to or quotes from other sources), interviews, observations, logical reasoning, and personal experience

Structure . How does the author organize the text?

Purpose . What question does the author seek to answer in the text? In other words, why do you think they wrote this piece?

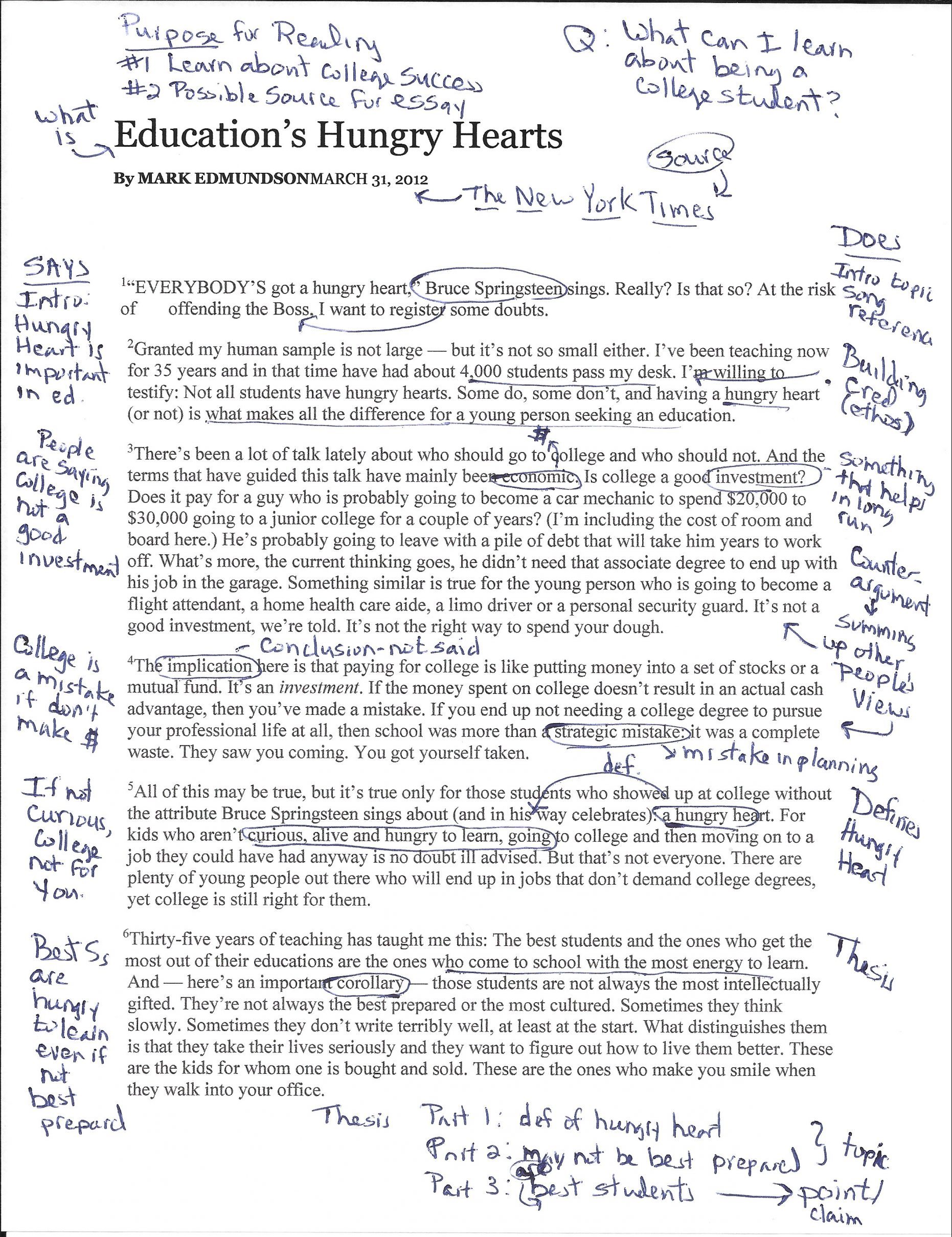

Mark-up Assignment: The Savvy Reader Practice

The object is to fill the empty space of the margins with your thoughts and questions to the text. By reading sympathetically (reading to understand what the writer is saying) and critically (reading to analyze and critique what the writer is saying), you are reading mindfully and creatively. You are finding those passages that you are drawn to, asking questions that you have, and beginning to develop your reaction, response, and ideas about a topic or issue. It’s a useful tool in the “getting started” phase of the writing process. Learning how to read effectively will be an invaluable skill in your college career and beyond because it means engaging in a task actively rather than passively.

Choose 1-2 paragraphs from READING X to fully annotate. This passage should be one that interests you, i.e. seems important, confusing, and/or prompted agreement, disagreement, or questions for you.

- Circle any word you think is crucial for the passage, including ones you cannot easily define.

- Underline phrases or images you think crucial for the meaning of the passage/essay.

- Put a bracket around ideas or assertions you find puzzling or questionable.

- Then write notes around the margins of the passage defining these terms, identifying the important ideas, or raising questions with the bracketed phrases. For each item you have circled, underlined, or bracketed, there should be a margin note. For this assignment, your margin notes should be substantive: they should meaty statements and full questions.

Photocopy or clear, legible photograph of paragraphs with your annotations or type up the paragraphs and annotate.

Writing as Inquiry Copyright © 2021 by Kara Clevinger and Stephen Rust is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Jump to navigation

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Transfer Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Honors and Scholars Admissions

- International Admissions

- Law Admissions

- Office of Financial Aid

- Orientation

- Pre-College Programs

- Scholarships

- Tuition & Fees

- Academic Calendar

- Academic Colleges

- Degree Programs

- Online Programs

- Class Schedule

- Workforce Development

- Sponsored Programs and Research Services

- Technology Transfer

- Faculty Expertise Database

- Research Centers

- College of Graduate Studies

- Institutional Research and Analysis

- At a Glance

- Concerned Vikes

- Free Speech on Campus

- Policies and Procedures

- Messages & Updates

- In the News

- Board of Trustees

- Senior Leadership Team

- Services Near CSU

Cleveland State University

Search this site

Critical reading: what is critical reading, and why do i need to do it.

Critical reading means that a reader applies certain processes, models, questions, and theories that result in enhanced clarity and comprehension. There is more involved, both in effort and understanding, in a critical reading than in a mere "skimming" of the text. What is the difference? If a reader "skims" the text, superficial characteristics and information are as far as the reader goes. A critical reading gets at "deep structure" (if there is such a thing apart from the superficial text!), that is, logical consistency, tone, organization, and a number of other very important sounding terms.

What does it take to be a critical reader? There are a variety of answers available to this question; here are some suggested steps:

1. Prepare to become part of the writer's audience.

After all, authors design texts for specific audiences, and becoming a member of the target audience makes it easier to get at the author's purpose. Learn about the author, the history of the author and the text, the author's anticipated audience; read introductions and notes.

2. Prepare to read with an open mind.

Critical readers seek knowledge; they do not "rewrite" a work to suit their own personalities. Your task as an enlightened critical reader is to read what is on the page, giving the writer a fair chance to develop ideas and allowing yourself to reflect thoughtfully, objectively, on the text.

3. Consider the title.

This may seem obvious, but the title may provide clues to the writer's attitude, goals, personal viewpoint, or approach.

4. Read slowly.

Again, this appears obvious, but it is a factor in a "close reading." By slowing down, you will make more connections within the text.

5. Use the dictionary and other appropriate reference works.

If there is a word in the text that is not clear or difficult to define in context: look it up. Every word is important, and if part of the text is thick with technical terms, it is doubly important to know how the author is using them.

6. Make notes.

Jot down marginal notes, underline and highlight, write down ideas in a notebook, do whatever works for your own personal taste. Note for yourself the main ideas, the thesis, the author's main points to support the theory. Writing while reading aids your memory in many ways, especially by making a link that is unclear in the text concrete in your own writing.

7. Keep a reading journal

In addition to note-taking, it is often helpful to regularly record your responses and thoughts in a more permanent place that is yours to consult. By developing a habit of reading and writing in conjunction, both skills will improve.

Critical reading involves using logical and rhetorical skills. Identifying the author's thesis is a good place to start, but to grasp how the author intends to support it is a difficult task. More often than not an author will make a claim (most commonly in the form of the thesis) and support it in the body of the text. The support for the author's claim is in the evidence provided to suggest that the author's intended argument is sound, or reasonably acceptable. What ties these two together is a series of logical links that convinces the reader of the coherence of the author's argument: this is the warrant. If the author's premise is not supportable, a critical reading will uncover the lapses in the text that show it to be unsound.

Questions, comments, and other sundry things may be sent to [email protected]

[Top of Page]

©2024 Cleveland State University | 2121 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44115-2214 | (216) 687-2000. Cleveland State University is an equal opportunity educator and employer. Affirmative Action | Diversity | Employment | Tobacco Free | Non-Discrimination Statement | Web Privacy Statement | Accreditations

- Subject Guides

Being critical: a practical guide

Critical reading.

- Being critical

- Critical thinking

- Evaluating information

- Reading academic articles

- Critical writing

The purposes and practices of reading

The way we read depends on what we’re reading and why we’re reading it. The way we read a novel is different to the way we read a menu . Perhaps we are reading to understand a subject, to increase our knowledge, to analyse data, to retrieve information, or maybe even to have fun! The purpose of our reading will determine the approach we take.

Reading for information

Suppose we were trying to find some directions or opening hours... We would need to scan the text for key words or phrases that answer our question, and then we would move on.

It's a bit like doing a Google search and then just reading the results page rather than accessing the website.

Reading for understanding

When we're reading for pleasure or doing background reading on a topic, we'll generally read the text once, from start to finish . We might apply skimming techniques to look through the text quickly and get the general gist. Our engagement with the text might therefore be quite passive: we're looking for a general understanding of what's being written, perhaps only taking in the bits that seem important.

Reading for analysis

When we're doing reading for an essay, dissertation, or thesis, we're going to need to actively read the text multiple times . All the while we'll engage our prior knowledge and actively apply it to our reading, asking questions of what's been written.

This is critical reading !

Reading strategies

When you’re reading you don’t have to read everything with the same amount of care and attention. Sometimes you need to be able to read a text very quickly.

There are three different techniques for reading:

- Scanning — looking over material quite quickly in order to pick out specific information;

- Skimming — reading something fairly quickly to get the general idea;

- Close reading — reading something in detail.

You'll need to use a combination of these methods when you are reading an academic text: generally, you would scan to determine the scope and relevance of the piece, skim to pick out the key facts and the parts to explore further, then read more closely to understand in more detail and think critically about what is being written.

These strategies are part of your filtering strategy before deciding what to read in more depth. They will save you time in the long run as they will help you focus your time on the most relevant texts!

You might scan when you are...

- ...browsing a database for texts on a specific topic;

- ...looking for a specific word or phrase in a text;

- ...determining the relevance of an article;

- ...looking back over material to check something;

- ...first looking at an article to get an idea of its shape.

Scan-reading essentially means that you know what you are looking for. You identify the chapters or sections most relevant to you and ignore the rest. You're scanning for pieces of information that will give you a general impression of it rather than trying to understand its detailed arguments.

You're mostly on the look-out for any relevant words or phrases that will help you answer whatever task you're working on. For instance, can you spot the word "orange" in the following paragraph?

Being able to spot a word by sight is a useful skill, but it's not always straightforward. Fortunately there are things to help you. A book might have an index, which might at least get you to the right page. An electronic text will let you search for a specific word or phrase. But context will also help. It might be that the word you're looking for is surrounded by similar words, or a range of words associated with that one. I might be looking for something about colour, and see reference to pigment, light, or spectra, or specific colours being called out, like red or green. I might be looking for something about fruit and come across a sentence talking about apples, grapes and plums. Try to keep this broader context in mind as you scan the page. That way, you're never really just going to be looking for a single word or orange on its own. There will normally be other clues to follow to help guide your eye.

Approaches to scanning articles:

- Make a note of any questions you might want to answer – this will help you focus;

- Pick out any relevant information from the title and abstract – Does it look like it relates to what you're wanting? If so, carry on...

- Flick or scroll through the article to get an understanding of its structure (the headings in the article will help you with this) – Where are certain topics covered?

- Scan the text for any facts , illustrations , figures , or discussion points that may be relevant – Which parts do you need to read more carefully? Which can be read quickly?

- Look out for specific key words . You can search an electronic text for key words and phrases using Ctrl+F / Cmd+F. If your text is a book, there might even be an index to consult. In either case, clumps of results could indicate an area where that topic is being discussed at length.

Once you've scanned a text you might feel able to reject it as irrelevant, or you may need to skim-read it to get more information.

You might skim when you are...

- ...jumping to specific parts such as the introduction or conclusion;

- ...going over the whole text fairly quickly without reading every word;

Skim-reading, or speed-reading, is about reading superficially to get a gist rather than a deep understanding. You're looking to get a feel for the content and the way the topic is being discussed.

Skim-reading is easier to do if the text is in a language that's very familiar to you, because you will have more of an awareness of the conventions being employed and the parts of speech and writing that you can gloss over. Not only will there be whole sections of a text that you can pretty-much ignore, but also whole sections of paragraphs. For instance, the important sentence in this paragraph is the one right here where I announce that the important part of the paragraph might just be one sentence somewhere in the middle. The rest of the paragraph could just be a framework to hang around this point in order to stop the article from just being a list.

However, it may more often be that the important point for your purposes comes at the start of the paragraph. Very often a paragraph will declare what it's going to be about early on, and will then start to go into more detail. Maybe you'll want to do some closer reading of that detail, or maybe you won't. If the first paragraph makes it clear that this paragraph isn't going to be of much use to you, then you can probably just stop reading it. Or maybe the paragraph meanders and heads down a different route at some point in the middle. But if that's the case then it will probably end up summarising that second point towards the end of the paragraph. You might therefore want to skim-read the last sentence of a paragraph too, just in case it offers up any pithy conclusions, or indicates anything else that might've been covered in the paragraph!

For example, this paragraph is just about the 1980s TV gameshow "Treasure Hunt", which is something completely irrelevant to the topic of how to read an article. "Treasure Hunt" saw two members of the public (aided by TV newsreader Kenneth Kendall) using a library of books and tourist brochures to solve a series of five clues (provided, for the most part, by TV weather presenter Wincey Willis). These clues would generally be hidden at various tourist attractions within a specific county of the British Isles. The contestants would be in radio contact with a 'skyrunner' (Anneka Rice) who had a map and the use of a helicopter (piloted by Keith Thompson). Solving a clue would give the contestants the information they needed to direct the skyrunner (and her crew of camera operator Graham Berry and video engineer Frank Meyburgh) to the location of the next clue, and, ultimately, to the 'treasure' (a token object such as a little silver brooch). All of this was done against the clock, the contestants having only 45' to solve the clues and find the treasure. This, necessarily, required the contestants to be able to find relevant information quickly: they would have to select the right book from the shelves, and then navigate that text to find the information they needed. This, inevitably, involved a considerable amount of skim-reading. So maybe this paragraph was slightly relevant after all? No, probably not...

Skim-reading, then, is all about picking out the bits of a text that look like they need to be read, and ignoring other bits. It's about understanding the structure of a sentence or paragraph, and knowing where the important words like the verbs and nouns might be. You'll need to take in and consider the meaning of the text without reading every single word...

Approaches to skim-reading articles:

- Pick out the most relevant information from the title and abstract – What type of article is it? What are the concepts? What are the findings?;

- Scan through the article and note the headings to get an understanding of structure;

- Look more closely at the illustrations or figures ;

- Read the conclusion ;

- Read the first and last sentences in a paragraph to see whether the rest is worth reading.

After skimming, you may still decide to reject the text, or you may identify sections to read in more detail.

Close reading

You might read closely when you are...

- ...doing background reading;

- ...trying to get into a new or difficult topic;

- ...examining the discussions or data presented;

- ...following the details or the argument.

Again, close reading isn't necessarily about reading every single word of the text, but it is about reading deeply within specific sections of it to find the meaning of what the author is trying to convey. There will be parts that you will need to read more than once, as you'll need to consider the text in great detail in order to properly take in and assess what has been written.

Approaches to the close reading of articles:

- Focus on particular passages or a section of the text as a whole and read all of its content – your aim is to identify all the features of the text;

- Make notes and annotate the text as you read – note significant information and questions raised by the text;

- Re-read sections to improve understanding;

- Look up any concepts or terms that you don’t understand.

Questioning

Questioning goes hand-in-hand with reading for analysis. Before you begin to read, you should have a question or set of questions that will guide you. This will give purpose to your reading, and focus you; it will change your reading from a passive pursuit to an active one, and make it easier for you to retain the information you find. Think about what you want to achieve and keep the purpose in mind as you're reading.

Ask yourself...

- Why am I reading this? — What is my task or assignment question, and how is this source helping to answer it?

- What do I already know about the subject? — How can I relate what I'm reading to my own experiences?

You'll need to ask questions of the text too:

- Examine the evidence or arguments presented;

- Check out any influences on the evidence or arguments;

- Check the limitations of study design or focus;

- Examine the interpretations made.

Are you prepared to accept the authors’ arguments, opinions, or conclusions?

Critical reading: why, what, and how

Blocks to critical reading.

Certain habits or approaches we have to life can hold us back from really thinking objectively about issues. We may not realise it, but often we're our own worst enemies when it comes to being critical...

Select a student to reveal the statement they've made.

I have been asked to work on an area that is completely new. Where do I start in terms of finding relevant texts?

Ask for guidance:

ask your tutor or module leader

use your module reading lists

make use of the Skills Guides (oh... you are! Excellent!)

ask your Faculty Librarians

Take a look at our contextagon and begin to consider sources of information .

I don’t understand what I'm reading – It's too difficult!

If the text is difficult, don’t panic!

If it is a journal article, scan the text first – look at the contents, abstract, introduction, conclusion and subheadings to try to make sense of the argument.

Then read through the whole text to try to understand the key messages, rather than every single word or section. On a second reading, you will find it easier to understand more.

If you are struggling to get to grips with theories or concepts, you might find it useful to look at a summary as a way in -- for example, in an online subject encyclopaedia .

If you are struggling with difficult vocabulary, it may be useful to keep a glossary of key vocabulary, particularly if it is specialist or technical.

Remember, the more you read, the more you will understand it and be able to use it yourself.

Take a look at our Academic sources Skills Guide .

Help! There is too much to read and too little time!

University study involves a large amount of reading. However, some texts on your reading lists are core texts and some are more optional.

You will generally need to read the core text, but on the optional list there may be a range of texts which deal with the same topic from different perspectives. You will need to decide which are the most relevant to your interests and assignments.

Keep in mind the questions you want the text to answer and look for what is relevant to those questions. Prioritise and read only as much as you need to get the information you need (if it's a book, use the index; if it's an article, concentrate on the relevant parts).

Improve your note-taking skills by keeping them brief and selective.

If in doubt, ask your tutor or Faculty Librarians for guidance.

Take a look at the Organise and Analyse section of the Skills Guides.

I am struggling to remember what I have read.

To remember what you have read, you need to interact with the material. If you have questioned and evaluated the material you are reading, you will find it easier to remember.

Improve your active note-taking skills using a method like Cornell or Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review (SQR3).

Annotate your pdfs and use a note-taking app .

Make time to consolidate your reading periodically. You could do this by summarising key points from memory or connecting ideas using mindmapping.

Consider using a reference management program to keep on top of reading, and mind-mapping software like Mindgenius to connect ideas.

Where did I read that thing?

Make sure you have a good system for taking notes and try to keep your notes organised/in one place, whether that is using an app or taking notes by hand. There is no right way to do this - find a system that works for you.

Logically label and file your notes, linking new information with what you already know and cross-reference with any handouts.

Make sure you make a note of information for referencing sources.

Where possible, save resources you have used to Google Drive or your University filestore , and organise these (e.g. by module, assessment, topic etc.).

Many of the above tips can be achieved with reference management software .

I have strong opinions about the argument being presented in the reading – why can’t I just put this side forward?

Truth is a complicated business. Core texts or texts by highly respected authors are an author’s interpretation, and that interpretation is not above question. Any single text only provides a perspective. Even a scientific observation may be modified by further evidence. Critical writing means making sure your argument is balanced, considering and critiquing a range of perspectives.

Read texts objectively and assess their value in terms of what they can bring to your work, rather than whether you agree with them or not.

If you agree or disagree strongly with an author, you still need to analyse their argument and justify why it is sound or unsound, reliable or unreliable, and valid or lacking validity.

Ignoring opposing views can be a mistake. Your reader may think you are unaware of the different views or are not willing to think the ideas through and challenge them.

Be careful not to be blinded by your own views about a topic or an author. Engaging actively with a text which you initially don’t agree with can mean you have to rethink or adjust your own position, making your final argument stronger.

Take a look at the other parts of the Being critical Skills Guides .

That's not right. Try again.

Being actively critical

Active reading is about making a conscious effort to understand and evaluate a text for its relevance to your studies. You would actively try to think about what the text is trying to say, for example by making notes or summaries.

Critical reading is about engaging with the text by asking questions rather than passively accepting what it says. Is the methodology sound? What was the purpose? Do ideas flow logically? Are arguments properly formulated? Is the evidence there to support what is being claimed?

When you're reading critically, you're looking to...

- ...link evidence to your own research;

- ...compare and contrast different sources effectively;

- ...focus research and sources;

- ...synthesise the information you've found;

- ...justify your own arguments with reference to other sources.

You're going beyond just an understanding of a text. You're asking questions of it; making judgements about it... What you're reading is no longer undisputed 'fact': it's an argument put forward by an author. And you need to determine whether that argument is a valid one.

"Reading without reflecting is like eating without digesting"

– Edmund Burke

"Feel free to reflect on the merits (or not) of that quote..."

– anon.

Critical reading involves understanding the content of the text as well as how the subject matter is developed...

- How true is what's being written?

- How significant are the statements that are being made?

Regardless of how objective, technical, or scientific the text may be, the authors will have made certain decisions during the writing process, and it is these decisions that we will need to examine.

Two models of critical reading

There are several approaches to critical reading. Here's a couple of models you might want to try:

Choose a chapter or article relevant to your assessment (or pick something from your reading list).

Then do the following:

Determine broadly what the text is about.

Look at the front and back covers

Scan the table of contents

Look at the title, headings, and subheadings

Read the abstract, introduction and conclusion

Are there any images, charts, data or graphs?

What are the questions the text will answer? Write some down.

Use the title, headings and subheadings to write questions

What questions do the abstract, introduction and conclusion prompt?

What do you already know about the topic? What do you need to know?

Do a first reading. Read selectively.

Read a section at a time

Answer your questions

Summarise or make brief notes

Underline or highlight any key points

Recite (in your own words)

Recall the key points.

Summarise key points from memory

Try to answer the questions you asked orally, without looking at the text or your notes

Use diagrams or mindmaps to recall the information

After you have completed the reading…

Go back over your notes and check they are clear

Check that you have answered all your questions

At a later date, review your notes to check that they make sense

At a later date, review the questions and see how much you can recall from memory

Choose a relevant article from your reading list and make brief notes on it using the prompts below.

Choose an article you have read earlier in your course and re-read it, applying the prompts below.

Compare your comments and the notes you have made. What are the differences?

Who is the text by? Who is the text aimed at? Who is described in the text?

What is the text about? What is the main point, problem or topic? What is the text's purpose?

Where is the problem/topic/issue situated?, and in what context?

When does the problem/topic/issue occur, and what is its context? When was the text written?

How did the topic/problem/issue occur? How does something work? How does one factor affect another? How does this fit into the bigger picture?

Why did the topic/problem/issue occur? Why was this argument/theory/solution used? Why not something else?

What if this or that factor were added/removed/altered? What if there are alternatives?

So what makes it significant? So what are the implications? So what makes it successful?

What next in terms of how and where else it's applied? What next in terms of what can be learnt? What next in terms of what needs doing now?

Here's a template for use with the model.

Go to File > Make a copy... to create your own version of the template that you can edit.

CC BY-NC-SA Learnhigher

Arguments & evidence

Academic reading can be a trial. In more ways than one...

It might help to think of every text you read as a witness in a court case. And you're the judge ! You're going to need to examine the testimony...

- What’s being claimed ?

- What are the reasons for making that claim?

- Are there gaps in the evidence?

- Do other witnesses support and corroborate their testimony?

- Does the testimony support the overall case ?

- How does the testimony relate to the other witnesses?

You're going to need to consider all sides of the case...

Considering the argument

An argument explains a position on something. A lot of academic writing is about gathering those claims and explaining your own position through their explanations.

You'll need to question...

- ...the author's claims ;

- ...the arguments they use — are their claims well documented ?;

- ...the counter-arguments presented;

- ...any bias in the source;

- ...the research method being used;

- ...how the author qualifies their arguments.

You'll also need to develop your own reasoned arguments, based on a logical interpretation of reliable sources of information.

What's the evidence?

Evidence isn't just the results of research or a reference to an academic study. You might use other authors' opinions to back up your argument. Keep in mind that some evidence is stronger than others:

You can get an idea of an author's certainty through the language they use, too:

Linking evidence to argument

- Why did the author select the evidence they did? — Why did they decide to use a particular methodology, choose a specific method, or conduct the work in the way they did?

- How does the author interpret the evidence?

- How does the evidence prove or help the argument?

Even in the most technical and scientific disciplines, the presentation of argument will always involve elements that can be examined and questioned. For example, you could ask:

- Why did the author select that particular topic of enquiry in the first place?

- Why did the author select that particular process of analysis?

Synthesis :

"the combination of components or elements to form a connected whole."

You'll need to make logical connections between the different sources you encounter, pulling together their findings. Are there any patterns that emerge?

Analyse the texts you've found, and how meaningful they are in context of your studies...

- How do they compare to each other and to any other knowledge you are gathering about the subject? Do some ideas complement or conflict with each other?

- How will you synthesise the different sources to serve an idea you are constructing? Are there any inferences you can draw from the material?

Embracing other perspectives

Good critical research seeks to be impartial, and will embrace (or, at the very least, address) conflicting opinions. Try to bring these into your research to show comprehensive searching and knowledge of the subject.

You can strengthen your argument by explaining, critically, why one source is more persuasive than another.

Recall & review

Synthesising research is much easier if you take notes. When you know an article is relevant to your area of research, read it and make notes which are relevant to you. Consider keeping a spreadsheet or something similar , to make a note of what you have read and how it relates to the task.

You don't need elaborate notes; just a summary of the relevant details. But you can use your notes to help with the process of analysing and synthesising the texts. One method you could try is the recall & review approach:

Try to summarise key words and elements of the text:

- Sketch a rough diagram of the text from memory — test what you can recall from your reading of the text;

- Make headings of the main ideas and note the supporting evidence;

- Include your evaluation — what were the strengths and weaknesses?

- Identify any gaps in your memory.

Go over your notes, focusing on the parts you found difficult. Organise your notes, re-read parts, and start to bring everything together...

- Summarise the text in preparation for writing;

- Be creative: use colour and arrows; make it easy to visualise;

- Highlight the ideas you may want to make use of;

- Identify areas for further research.

Critical analysis vs criticism

The aim of critical reading and critical writing is not to find fault; it's not about focusing on the negative or being derogatory. Rather it's about assessing the strength of the evidence and the argument. It's just as useful to conclude that a study or an article presents very strong evidence and a well-reasoned argument as it is to identify weak evidence and poorly formed arguments.

Criticising

The author's argument is poor because it is badly written.

Critical analysis

The author's argument is unconvincing without further supporting evidence.

Academic reading: What it is and how to do it

Struggling with academic reading? This bitesize workshop breaks it down for you! Discover how to read faster, smarter, and make those academic texts work for you:

Think critically about what you read...

- examine the evidence or arguments presented

- check out any influences on the evidence or arguments

- check out the limitations of study design or focus

- examine the interpretations made

Active critical reading

It's important to take an analytical approach to reading the texts you encounter. In the concluding part of our " Being critical " theme, we look at how to evaluate sources effectively, and how to develop practical strategies for reading in an efficient and critical manner.

Forthcoming training sessions

Forthcoming sessions on :

CITY College

Please ensure you sign up at least one working day before the start of the session to be sure of receiving joining instructions.

If you're based at CITY College you can book onto the following sessions by sending an email with the session details to your Academic Liaison Librarian:

There's more training events at:

- << Previous: Reading academic articles

- Next: Critical writing >>

- Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024 5:46 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.york.ac.uk/critical

- LEARNING SKILLS

- Study Skills

- Critical Reading

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Learning Skills:

- A - Z List of Learning Skills

- What is Learning?

- Learning Approaches

- Learning Styles

- 8 Types of Learning Styles

- Understanding Your Preferences to Aid Learning

- Lifelong Learning

- Decisions to Make Before Applying to University

- Top Tips for Surviving Student Life

- Living Online: Education and Learning

- 8 Ways to Embrace Technology-Based Learning Approaches

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Critical Thinking and Fake News

- Understanding and Addressing Conspiracy Theories

- Critical Analysis

- Top Tips for Study

- Staying Motivated When Studying

- Student Budgeting and Economic Skills

- Getting Organised for Study

- Finding Time to Study

- Sources of Information

- Assessing Internet Information

- Using Apps to Support Study

- What is Theory?

- Styles of Writing

- Effective Reading

- Note-Taking from Reading

- Note-Taking for Verbal Exchanges

- Planning an Essay

- How to Write an Essay

- The Do’s and Don’ts of Essay Writing

- How to Write a Report

- Academic Referencing

- Assignment Finishing Touches

- Reflecting on Marked Work

- 6 Skills You Learn in School That You Use in Real Life

- Top 10 Tips on How to Study While Working

- Exam Skills

Get the SkillsYouNeed Study Skills eBook

Part of the Skills You Need Guide for Students .

- Writing a Dissertation or Thesis

- Research Methods

- Teaching, Coaching, Mentoring and Counselling

- Employability Skills for Graduates

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Critical Reading and Reading Strategy

What is critical reading.

Reading critically does not, necessarily, mean being critical of what you read.

Both reading and thinking critically don’t mean being ‘ critical ’ about some idea, argument, or piece of writing - claiming that it is somehow faulty or flawed.

Critical reading means engaging in what you read by asking yourself questions such as, ‘ what is the author trying to say? ’ or ‘ what is the main argument being presented? ’

Critical reading involves presenting a reasoned argument that evaluates and analyses what you have read. Being critical, therefore - in an academic sense - means advancing your understanding , not dismissing and therefore closing off learning.

See also: Listening Types to learn about the importance of critical listening skills.

To read critically is to exercise your judgement about what you are reading – that is, not taking anything you read at face value.

When reading academic material you will be faced with the author’s interpretation and opinion. Different authors will, naturally, have different slants. You should always examine what you are reading critically and look for limitations, omissions, inconsistencies, oversights and arguments against what you are reading.

In academic circles, whilst you are a student, you will be expected to understand different viewpoints and make your own judgements based on what you have read.

Critical reading goes further than just being satisfied with what a text says, it also involves reflecting on what the text describes, and analysing what the text actually means, in the context of your studies.

As a critical reader you should reflect on:

- What the text says: after critically reading a piece you should be able to take notes, paraphrasing - in your own words - the key points.

- What the text describes: you should be confident that you have understood the text sufficiently to be able to use your own examples and compare and contrast with other writing on the subject in hand.

- Interpretation of the text: this means that you should be able to fully analyse the text and state a meaning for the text as a whole.

Critical reading means being able to reflect on what a text says, what it describes and what it means by scrutinising the style and structure of the writing, the language used as well as the content.

Critical Thinking is an Extension of Critical Reading

Thinking critically, in the academic sense, involves being open-minded - using judgement and discipline to process what you are learning about without letting your personal bias or opinion detract from the arguments.

Critical thinking involves being rational and aware of your own feelings on the subject – being able to reorganise your thoughts, prior knowledge and understanding to accommodate new ideas or viewpoints.

Critical reading and critical thinking are therefore the very foundations of true learning and personal development.

See our page: Critical Thinking for more.

Developing a Reading Strategy

You will, in formal learning situations, be required to read and critically think about a lot of information from different sources.

It is important therefore, that you not only learn to read critically but also efficiently.

The first step to efficient reading is to become selective.

If you cannot read all of the books on a recommended reading list, you need to find a way of selecting the best texts for you. To start with, you need to know what you are looking for. You can then examine the contents page and/or index of a book or journal to ascertain whether a chapter or article is worth pursuing further.

Once you have selected a suitable piece the next step is to speed-read.

Speed reading is also often referred to as skim-reading or scanning. Once you have identified a relevant piece of text, like a chapter in a book, you should scan the first few sentences of each paragraph to gain an overall impression of subject areas it covers. Scan-reading essentially means that you know what you are looking for, you identify the chapters or sections most relevant to you and ignore the rest.

When you speed-read you are not aiming to gain a full understanding of the arguments or topics raised in the text. It is simply a way of determining what the text is about.

When you find a relevant or interesting section you will need to slow your reading speed dramatically, allowing you to gain a more in-depth understanding of the arguments raised. Even when you slow your reading down it may well be necessary to read passages several times to gain a full understanding.

See also: Speed-Reading for Professionals .

Following SQ3R

SQ3R is a well-known strategy for reading. SQ3R can be applied to a whole range of reading purposes as it is flexible and takes into account the need to change reading speeds.

SQ3R is an acronym and stands for:

This relates to speed-reading, scanning and skimming the text. At this initial stage you will be attempting to gain the general gist of the material in question.

It is important that, before you begin to read, you have a question or set of questions that will guide you - why am I reading this? When you have a purpose to your reading you want to learn and retain certain information. Having questions changes reading from a passive to an active pursuit. Examples of possible questions include:

- What do I already know about this subject?

- How does this chapter relate to the assignment question?

- How can I relate what I read to my own experiences?

Now you will be ready for the main activity of reading. This involves careful consideration of the meaning of what the author is trying to convey and involves being critical as well as active.

Regardless of how interesting an article or chapter is, unless you make a concerted effort to recall what you have just read, you will forget a lot of the important points. Recalling from time to time allows you to focus upon the main points – which in turn aids concentration. Recalling gives you the chance to think about and assimilate what you have just read, keeping you active. A significant element in being active is to write down, in your own words, the key points.

The final step is to review the material that you have recalled in your notes. Did you understand the main principles of the argument? Did you identify all the main points? Are there any gaps? Do not take for granted that you have recalled everything you need correctly – review the text again to make sure and clarify.

Continue to: Effective Reading Critical Thinking

See also: Critical Analysis Writing a Dissertation Critical Thinking and Fake News

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

In Between the Lines: A Guide to Reading Critically

I often find that Princeton professors assume that we all know how to “read critically.” It’s a phrase often included in essay prompts, and a skill necessary to academic writing. Maybe we’re familiar with its definition: close examination of a text’s logic, arguments, style, and other content in order to better understand the author’s intent. Reading non-critically would be identifying a metaphor in a passage, whereas the critical reader would question why the author used that specific metaphor in the first place. Now that the terminology is clarified, what does critical reading look like in practice? I’ve put together a short guide on how I approach my readings to help demystify the process.

- Put on your scholar hat. Critical reading starts before the first page. You should assume that the reading in front of you was the product of several choices made by the author, and that each of these choices is subject to analysis. This is a critical mindset, but importantly, not a negative one. Not taking a reading at face value doesn’t mean approaching the reading hoping to find everything that’s wrong, but rather what could be improved .

- Revisit Writing Sem : Motive and thesis are incredibly helpful guides to understanding tough academic texts. Examining why the author is writing this text (motive), provides a context for the work that follows. The thesis should be in the back of your mind at all times to understand how the evidence presented proves it, but simultaneously thinking about the motive allows you to think about what opponents to the author might say, and then question how the evidence would stand up to these potential rebuttals.

- Get physical . Take notes! Critical reading involves making observations and insights—track them! My process involves underlining, especially as I see recurring terms, images, or themes. As I read, I also like to turn back and forth constantly between pages to link up arguments. I was reading a longer legal text for a class and found that flipping back and forth helped me clarify the ideas presented in the beginning of the text so I could track their development in later pages.

- Play Professor. While I’m reading, I like to imagine potential discussion or essay topics I would come up with if I were a professor. These usually involves examining the themes of the text, placing this text in comparison or contrast with another one we have read in the class, and paying close attention to how the evidence attempts to prove the thesis.

- Form an (informed) opinion. After much work, underlining, and debating, it’s safe to make your own judgments about the author’s work. In forming this opinion, I like to mentally prepare to have this opinion debated, which helps me complicate my own conclusions—a great start to a potential essay!

Critical reading is an important prerequisite for the academic writing that Princeton professors expect. The best papers don’t start with the first word you type, but rather how you approach the texts composing your essay subject. Hopefully, this guide to reading critically will help you write critically as well!

–Elise Freeman, Social Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Reading Critically and Actively

Critical reading is a vital part of the writing process. In fact, reading and writing processes are alike. In both, you make meaning by actively engaging a text. As a reader, you are not a passive participant, but an active constructor of meaning. Exhibiting an inquisitive, "critical" attitude towards what you read will make anything you read richer and more useful to you in your classes and your life. This guide is designed to help you to understand and engage this active reading process more effectively so that you can become a better critical reader.

Reading a Text--Some Definitions

You might think that reading a text means curling up with a good book, or forcing yourself to study a textbook. Actually, reading a text can mean much more. First of all, let's define the two terms of interest here--"reading" and "text."

What Counts as Reading?

Reading is something we do with books and other print materials, certainly, but we also read things like the sky when we want to know what the weather is doing, someone's expression or body language when we want to know what someone is thinking or feeling, or an unpredictable situation so we'll know what the best course of action is. As well as reading to gather information, "reading" can mean such diverse things as interpreting, analyzing, or attempting to make predictions.

What Counts as a Text?

When we think of a text, we may think of words in print, but a text can be anything from a road map to a movie. Some have expanded the meaning of "text" to include anything that can be read, interpreted or analyzed. So a painting can be a text to interpret for some meaning it holds, and a mall can be a text to be analyzed to find out how modern Americans behave in their free time.

How Do Readers Read?

Those who study the way readers read have come up with some different theories about how readers make meaning from the texts they read.

Being aware of how readers read is important so that you can become a more critical reader. In fact, you may discover that you are already a critical reader.

The Reading Equation

Prior Knowledge + Predictions = Comprehension

When we read, we don't decipher every word on the page for its individual meaning. We process text in chunks, and we also employ other "tricks" to help us make meaning out of so many individual words in a text we are reading. First, we bring prior knowledge to everything we read, whether we are aware of it or not. Titles of texts, authors' names, and the topic of the piece all trigger prior knowledge in us. The more prior knowledge we have, the better prepared we are to make meaning of the text. With prior knowledge we make predictions, or guesses about how what we are reading relates to our prior experience. We also make predictions about what meaning the text will convey.

Related Information: How can Reaching Comprehension Make Us Better Writers?

When you have successfully comprehended the text you are reading, you should take this comprehension one step further and try to apply it to your writing process. Good writers know that readers have to work to make meaning of texts, so they will try to make the reader's journey through the text as effortless as possible. As a writer you can help readers tap into prior knowledge by clearly outlining your intent in the introduction of your paper and making use of your own personal experience. You can help readers make accurate guesses by employing clear organization and using clear transitions in your paper.

Related Information: Making Predictions

Whether you realize it or not, you are always making guesses about what you will encounter next in a text. Making predictions about where a text is headed is an important part of the comprehension equation. It's alright to make wrong guesses about what a text will do--wrong guesses are just as much a part of the meaning-making process of reading as right guesses are.

Related Information: Tapping into Prior Knowledge

It's important to tap into your prior knowledge of subject before you read about it. Writing an entry in your writer's notebook may be a good way to access this prior knowledge. Discussing the subject with classmates before you read is also a good idea. Tapping into prior knowledge will allow you to approach a piece of writing with more ways to create comprehension than if you start reading "cold."

Cognitive Reading Theory

When you read, you may think you are decoding a message that a writer has encoded into a text. Error in reading comprehension, in this model, would occur if you as a reader were not decoding the message correctly, or if the writer was not encoding the message accurately or clearly. The writer, however, would have the responsibility of getting the message into the text, and the reader would assume a passive role.

Related Information: Reading has a Model

Let's look at a more recent and widely accepted model of reading that is based on cognitive psychology and schema theory. In this model, the reader is an active participant who has an important interpretive function in the reading process. In other words, in the cognitive model you as a reader are more than a passive participant who receives information while an active text makes itself and its meanings known to you. Actually, the act of reading is a push and pull between reader and text. As a reader, you actively make, or construct, meaning; what you bring to the text is at least as important as the text itself.

Related Information: Reading is an active, constuctive, meaning-making process

Readers construct a meaning they can create from a text, so that "what a text means" can differ from reader to reader. Readers construct meaning based not only on the visual cues in the text (the words and format of the page itself) but also based on non-visual information such as all the knowledge readers already have in their heads about the world, their experience with reading as an activity, and, especially, what they know about reading different kinds of writing. This kind of non-visual information that readers bring with them before they even encounter the text is far more potent than the actual words on the page.

Related Information: Reading is hypothesis based

In yet another layer of complexity, readers also create for themselves an idea of what the text is about before they read it. In reading, prediction is much more important than decoding. In fact, if we had to read each letter and word, we couldn't possibly remember the letters and words long enough to put them all together to make sense of a sentence. And reading larger chunks than sentences would be absolutely impossible with our limited short-term memories.

So, instead of looking at each word and figuring out what it "means," readers rely on all their language and discourse knowledge to predict what a text is about. Then we sample the text to confirm, revise, or discard that hypothesis. More highly structured texts with topic sentences and lots of forecasting features are easier to hypothesize about; they're also easier to learn information from. Less structured texts that allow lots of room for predictions (and revised and discarded hypotheses) give more room for creative meanings constructed by readers. Thus we get office memos or textbooks or entertaining novels.

Related Information: Reading is multi-level

When we read a text, we pick up visual cues based on font size and clarity, the presence or absence of "pictures," spelling, syntax, discourse cues, and topic. In other words, we integrate data from a text including its smallest and most discrete features as well as its largest, most abstract features. Usually, we don't even know we're integrating data from all these levels. In addition, data from the text is being integrated with what we already know from our experience in the world about all fonts, pictures, spelling, syntax, discourse, and the topic more generally. No wonder reading is so complex!

Related Information: Reading is Strategic

We change our reading strategies (processes) depending on why we're reading. If we are reading an instruction manual, we usually read one step at a time and then try to do whatever the instructions tell us. If we are reading a novel, we don't tend to read for informative details. If we a reading a biology textbook, we read for understanding both of concepts and details (particularly if we expected to be tested over our comprehension of the material.)

Our goals for reading will affect the way we read a text. Not only do we read for the intended message, but we also construct a meaning that is valuable in terms of our purpose for reading the text.

Strategic reading also allows us to speed up or slow down, depending on our goals for reading (e.g. scanning newspaper headlines v. Carefully perusing a feature story).

Strategies for Reading More Critically

Although you probably already read critically in some respects, here are some things you can do when you read a text to improve your critical reading skills.

Most successful critical readers do some combination of the following strategies:

Summarizing

Previewing a text means gathering as much information about the text as you can before you actually read it. You can ask yourself the following questions:

What is my Purpose for Reading?

If you are being asked to summarize a particular piece of writing, you will want to look for the thesis and main points. Are you being asked to respond to a piece? If so, you may want to be conscious of what you already know about the topic and how you arrived at that opinion.

What can the Title Tell Me About the Text?

Before you read, look at the title of the text. What clues does it give you about the piece of writing? It may reveal the author's stance, or make a claim the piece will try to support. Good writers usually try to make their titles do work to help readers make meaning of the text from the reader's first glance at it.

Who is the Author?

If you have heard the author's name before, what comes to your mind in terms of their reputation and/or stance on the issue you are reading about? Has the author written other things of which you are aware? How does the piece in front of you fit into to the author's body of work? What is the author's political position on the issue they are writing about? Are they liberal, conservative, or do you know anything about what prompted them to write in the first place?

How is the Text Structured?

Sometimes the structure of a piece can give you important clues to its meaning. Be sure to read all section headings carefully. Also, reading the opening sentences of paragraphs should give you a good idea of the main ideas contained in the piece.

Annotating is an important skill to employ if you want to read critically. Successful critical readers read with a pencil in their hand, making notes in the text as they read. Instead of reading passively, they create an active relationship with what they are reading by "talking back" to the text in its margins. You may want to make the following annotations as you read:

Mark the Thesis and Main Points of the Piece

Mark key terms and unfamiliar words, underline important ideas and memorable images, write your questions and/or comments in the margins of the piece, write any personal experience related to the piece, mark confusing parts of the piece, or sections that warrant a reread, underline the sources, if any, the author has used.

Mark the thesis and main points of the piece. The thesis is the main idea or claim of the text, and relates to the author's purpose for writing. Sometimes the thesis is not explicitly stated, but is implied in the text, but you should still be able to paraphrase an overall idea the author is interested in exploring in the text. The thesis can be thought of as a promise the writer makes to the reader that the rest of the essay attempts to fulfill.

The main points are the major subtopics, or sub-ideas the author wants to explore. Main points make up the body of the text, and are often signaled by major divisions in the structure of the text.

Marking the thesis and main points will help you understand the overall idea of the text, and the way the author has chosen to develop her or his thesis through the main points s/he has chosen.

While you are annotating the text you are reading, be sure to circle unfamiliar words and take the time to look them up in the dictionary. Making meaning of some discussions in texts depends on your understanding of pivotal words. You should also annotate key terms that keep popping up in your reading. The fact that the author uses key terms to signal important and/or recurring ideas means that you should have a firm grasp of what they mean.

You will want to underline important ideas and memorable images so that you can go back to the piece and find them easily. Marking these things will also help you relate to the author's position in the piece more readily. Writers may try to signal important ideas with the use of descriptive language or images, and where you find these stylistic devices, there may be a key concept the writer is trying to convey.

Writing your own questions and responses to the text in its margins may be the most important aspect of annotating. "Talking back" to the text is an important meaning-making activity for critical readers. Think about what thoughts and feelings the text arouses in you. Do you agree or disagree with what the author is saying? Are you confused by a certain section of the text? Write your reactions to the reading in the margins of the text itself so you can refer to it again easily. This will not only make your reading more active and memorable, but it may be material you can use in your own writing later on.

One way to make a meaningful connection to a text is to connect the ideas in the text to your own personal experience. Where can you identify with what the author is saying? Where do you differ in terms of personal experience? Identifying personally with the piece will enable you to get more out of your reading because it will become more relevant to your life, and you will be able to remember what you read more easily.

Be sure to mark confusing parts of the piece you are reading, or sections that warrant a reread. It is tempting to glide over confusing parts of a text, probably because they cause frustration in us as readers. But it is important to go back to confusing sections to try to understand as much as you can about them. Annotating these sections may also remind you to bring up the confusing section in class or to your instructor.

Good critical readers are always aware of the sources an author uses in her or his text. You should mark sources in the text and ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the source relevant? In other words, does the source work to support what the author is trying to say?

- Is the source credible? What is his or her reputation? Is the source authoritative? What is the source's bias on the issue? What is the source's political and/or personal stance on the issue?

- Is the source current? Is there new information that refutes what the source is asserting? Is the writer of the text using source material that is outdated?

Summarizing the text you've read is an valuable way to check your understanding of the text. When you summarize, you should be able to find and write down the thesis and main points of the text.

Annotating the thesis and main points

Analyzing a text means breaking it down into its parts to find out how these parts relate to one another. Being aware of the functions of various parts of a piece of writing and their relationship to one another and the overall piece can help you better understand a text's meaning. To analyze a text, you can look at the following things:

- Assumptions

- Author Bias

Analyzing Evidence

Consider the evidence the author presents. Is there enough evidence to support the point the author is trying to make? Does the evidence relate to the main point in a logical way? In other words, does the evidence work to prove the point, or does is contradict the point, or show itself to be irrelevant to the point the author is trying to make?

Related Information: Source Evaluation

Analyzing Assumptions

Consider any assumptions the author is making. Assumptions may be unstated in the piece of writing you are assessing, but the writer may be basing her or his thesis on them. What does the author have to believe is true before the rest of her or his essay makes sense?

Example: "[I]f a college recruiter argues that the school is superior to most others because its ratio of students to teachers is low, the unstated assumptions are (1) that students there will get more attention, and (2) that more attention results in a better education" (Crusius and Channell, The Aims of Argument , Mayfield Publishing Co., 1995).

Analyzing Sources

If an author uses outside sources to back up what s/he is saying, analyzing those sources is an important critical reading activity. Not all sources are created equal. There are at least three criteria to keep in mind when you are evaluating a source:

- Is the Source Relevant?

- Is the Source Credible?

- Is the Source Current?

Analyzing Author Bias

Taking a close look at the author's bias can tell you a lot about a text. Ask yourself what experiences in the author's background may have led him or her to hold the position s/he does. What does s/he hope to gain from taking this position? How does the author's position stand up in comparison to other positions on the issue? Knowing where the author is "coming from" can help you to more easily make meaning from a text.

Re-reading is a crucial part of the critical reading process. Good readers will reread a piece several times, until they are satisfied they know it inside and out. It is recommended that you read a text three times to make as much meaning as you can.

The First Reading

The first time you read a text, skim it quickly for its main ideas. Pay attention to the introduction, the opening sentences of paragraphs, and section headings, if there are any. Previewing the text in this way gets you off to a good start when you have to read critically.

The Second Reading

The second reading should be a slow, meditative read, and you should have your pencil in your hand so you can annotate the text. Taking time to annotate your text during the second reading may be the most important strategy to master if you want to become a critical reader.

The Third Reading

The third reading should take into account any questions you asked yourself by annotating the margins. You should use this reading to look up any unfamiliar words, and to make sure you have understood any confusing or complicated sections of the text.

Responding to what you read is an important step in understanding what you read. You can respond in writing, or by talking about what you've read to others. Here are several ways you can respond critically to a piece of writing:

- Writing a Response in Your Writer's Notebook

- Discussing the Text with Others

Writing a response in your writer's notebook