Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 June 2020

Half the world’s population are exposed to increasing air pollution

- G. Shaddick ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4117-4264 1 ,

- M. L. Thomas 2 ,

- P. Mudu 3 ,

- G. Ruggeri 3 &

- S. Gumy 3

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science volume 3 , Article number: 23 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

43k Accesses

186 Citations

509 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Environmental impact

Air pollution is high on the global agenda and is widely recognised as a threat to both public health and economic progress. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 4.2 million deaths annually can be attributed to outdoor air pollution. Recently, there have been major advances in methods that allow the quantification of air pollution-related indicators to track progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals and that expand the evidence base of the impacts of air pollution on health. Despite efforts to reduce air pollution in many countries there are regions, notably Central and Southern Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, in which populations continue to be exposed to increasing levels of air pollution. The majority of the world’s population continue to be exposed to levels of air pollution substantially above WHO Air Quality Guidelines and, as such, air pollution constitutes a major, and in many areas, increasing threat to public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Environmental determinants of cardiovascular disease: lessons learned from air pollution

Sadeer G. Al-Kindi, Robert D. Brook, … Sanjay Rajagopalan

Global air pollution exposure and poverty

Jun Rentschler & Nadezda Leonova

Health impacts of air pollution exposure from 1990 to 2019 in 43 European countries

Alen Juginović, Miro Vuković, … Valentina Biloš

Introduction

In 2016, the WHO estimated that 4.2 million deaths annually could be attributed to ambient (outdoor) fine particulate matter air pollution, or PM 2.5 (particles smaller than 2.5 μm in diameter) 1 . PM 2.5 comes from a wide range of sources, including energy production, households, industry, transport, waste, agriculture, desert dust and forest fires and particles can travel in the atmosphere for hundreds of kilometres and their chemical and physical characteristics may vary greatly over time and space. The WHO developed Air Quality Guidelines (AQG) to offer guidance for reducing the health impacts of air pollution. The first edition, the WHO AQG for Europe, was published in 1987 with a global update (in 2005) reflecting the increased scientific evidence of the health risks of air pollution worldwide and the growing appreciation of the global scale of the problem 2 . The current WHO AQG states that annual mean concentration should not exceed 10 μg/m 3 2 .

The adoption and implementation of policy interventions have proved to be effective in improving air quality 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 . There are at least three examples of enforcement of long-term policies that have reduced concentration of air pollutants in Europe and North America: (i) the Clean Air Act in 1963 and its subsequent amendments in the USA; (ii) the Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution (LRTAP) with protocols enforced since the beginning of the 1980s in Europe and North America 8 ; and (iii) the European emission standards passed in the European Union in the early 1990s 9 . However, between 1960 and 2009 concentrations of PM 2.5 globally increased by 38%, due in large part to increases in China and India, with deaths attributable to air pollution increasing by 124% between 1960 and 2009 10 .

The momentum behind the air pollution and climate change agendas, and the synergies between them, together with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide an opportunity to address air pollution and the related burden of disease. Here, trends in global air quality between 2010 and 2016 are examined in the context of attempts to reduce air pollution, both through long-term policies and more recent attempts to reduce levels of air pollution. Particular focus is given to providing comprehensive coverage of estimated concentrations and obtaining (national-level) distributions of population exposures for health impact assessment. Traditionally, the primary source of information has been measurements from ground monitoring networks but, although coverage is increasing, there remain regions in which monitoring is sparse, or even non-existent (see Supplementary Information) 11 . The Data Integration Model for Air Quality (DIMAQ) was developed by the WHO Data Integration Task Force (see Acknowledgements for details) to respond to the need for improved estimates of exposures to PM 2.5 at high spatial resolution (0.1° × 0.1°) globally 11 . DIMAQ calibrates ground monitoring data with information from satellite retrievals of aerosol optical depth, chemical transport models and other sources to provide yearly air quality profiles for individual countries, regions and globally 11 . Estimates of PM 2.5 concentrations have been compared with previous studies and a good quantitative agreement in the direction and magnitude of trends has been found. This is especially valid in data rich settings (North America, Western Europe and China) where trends results are consistent with what has been found from the analysis of ground level PM 2.5 measurements.

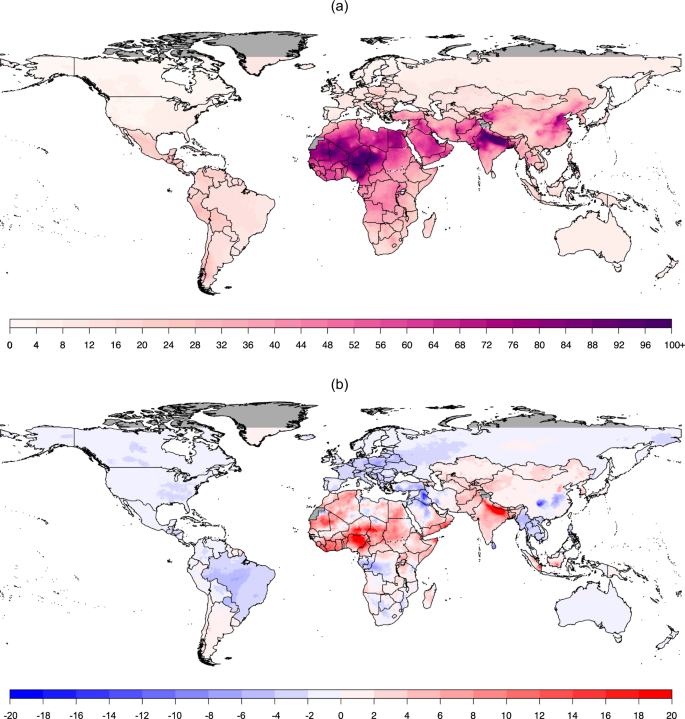

Figure 1a shows average annual concentrations of PM 2.5 for 2016, estimated using DIMAQ,; and Fig. 1b the differences in concentrations between 2010 and 2016. Although air pollution affects high and low-income countries alike, low- and middle-income countries experience the highest burden, with the highest concentrations being seen in Central, Eastern Southern and South-Eastern Asia 12 .

a Concentrations in 2016. b Changes in concentrations between 2010 and 2016.

The high concentrations observed across parts of the Middle East, parts of Asia and Sub-Saharan regions of Africa are associated with sand and desert dust. Desert dust has received increasing attention due to the magnitude of its concentration and the capacity to be transported over very long distances in particular areas of the world 13 , 14 . The Sahara is one of the biggest global source of desert dust 15 and the increase of PM 2.5 in this region is consistent with the prediction of an increase of desert dust due to climate change 16 , 17 .

Globally, 55.3% of the world’s population were exposed to increased levels of PM 2.5 , between 2010 and 2016, however there are marked differences in the direction and magnitude of trends across the world. For example, in North America and Europe annual average population-weighted concentrations decreased from 12.4 to 9.8 μg/m 3 while in Central and Southern Asia they rose from 54.8 to 61.5 μg/m 3 . Reductions in concentrations observed in North America and Europe align with those reported by the US Environmental Protection Agency and European Environmental Agency (EEA) 18 , 19 . The lower values observed in these regions reflect substantial regulatory processes that were implemented thirty years ago that have led to substantial decreases in air pollution over previous decades 18 , 20 , 21 . In high-income countries, the extent of air pollution from widespread coal and other solid-fuel burning, together with other toxic emissions from largely unregulated industrial processes, declined markedly with Clean Air Acts and similar ‘smoke control’ legislation introduced from the mid-20th century. However, these remain important sources of air pollution in other parts of the world 22 . In North America and Europe, the rates of improvements are small reflecting the difficulties in reducing concentrations at lower levels.

Assessing the health impacts of air pollution requires detailed information of the levels to which specific populations are exposed. Specifically, it is important to identify whether areas where there are high concentrations are co-located with high populations within a country or region. Population-weighted concentrations, often referred to as population-weighted exposures, are calculated by spatially aligning concentrations of PM 2.5 with population estimates (see Supplementary Information).

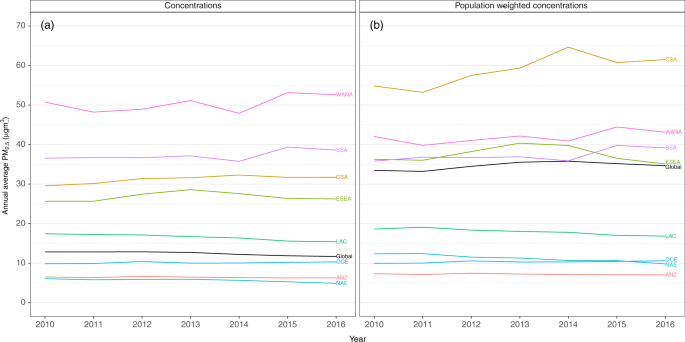

Figure 2 shows global trends in estimated concentrations and population-weighted concentrations of PM 2.5 for 2010–2016, together with trends for SDG regions (see Supplementary Fig. 1.1 ). Where population-weighted exposures are higher than concentrations, as seen in Central Asia and Southern Asia, this indicates that higher levels of air pollution coincide with highly populated areas. Globally, whilst concentrations have reduced slightly (from 12.8 μg/m 3 in 2010 to 11.7 in 2016), population-weighted concentrations have increased slightly (33.5 μg/m 3 in 2010, 34.6 μg/m 3 in 2016). In North America and Europe both concentrations and population-weighted concentrations have decreased (6.1–4.9 and 12.4–9.8 μg/m 3 , respectively). The association between concentrations and population can be clearly seen for Central Asia and Southern Asia where concentrations increased from 29.6 to 31.7 μg/m 3 (a 7% increase) while population-weighted concentrations were higher both in magnitude and in percentage of increase, increasing from 54.8 to 61.5 μg/m 3 (a 12% increase).

a Concentrations. b Population-weighted concentrations.

For the Eastern Asia and South Eastern Asia concentrations increase from 2010 to 2013 and then decrease from 2013 to 2016, a result of the implementation of the ‘Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan’ 21 and the transition to cleaner energy mix due to increased urbanization in China 23 , 24 , 25 . Population-weighted concentrations for urban areas in this region are strongly influenced by China, which comprises 62.6% of the population in the region. Population-weighted concentrations are higher than the concentrations and the decrease is more marked (in the population-weighted concentrations), indicating that the implementation of policies has been successful in terms of the number of people affected. The opposite effect of population-weighting is observed in areas within Western Asia and Northern Africa where an increasing trend in population-weighted concentrations (from 42.0 to 43.1. μg/m 3 ) contains lower values than for concentrations (from 50.7 to 52.6 μg/m 3 ). In this region, concentrations are inversely correlated with population, reflecting the high concentrations associated with desert dust in areas of lower population density.

Long-term policies to reduce air pollution have been shown to be effective and have been implemented in many countries, notably in Europe and the United States. However, even in countries with the cleanest air there are large numbers of people exposed to harmful levels of air pollution. Although precise quantification of the outcomes of specific policies is difficult, coupling the evidence for effective interventions with global, regional and local trends in air pollution can provide essential information for the evidence base that is key in informing and monitoring future policies. There have been major advances in methods that expand the knowledge base about impacts of air pollution on health, from evidence on the health effects 26 , modelling levels of air pollution 1 , 11 and quantification of health impacts that can be used to monitor and report on progress towards the air pollution-related indicators of the Sustainable Development Goals: SDG 3.9.1 (mortality rate attributed to household and ambient air pollution); SDG 7.1.2 (proportion of population with primary reliance on clean fuels and technology); and SDG 11.6.2 (annual mean levels of fine particulate matter (e.g., PM 2.5 and PM 10 ) in cities (population weighted)) 1 . There is a continuing need for further research, collaboration and sharing of good practice between scientists and international organisations, for example the WHO and the World Meteorological Organization, to improve modelling of global air pollution and the assessment of its impact on health. This will include developing models that address specific questions, including for example the effects of transboundary air pollution and desert dust, and to produce tools that provide policy makers with the ability to assess the effects of interventions and to accurately predict the potential effects of proposed policies.

Globally, the population exposed to PM 2.5 levels above the current WHO AQG (annual average of 10 μg/m 3 ) has fallen from 94.2% in 2010 to 90.0% in 2016, driven largely by decreases in North America and Europe (from 71.0% in 2010 to 48.6% in 2016). However, no such improvements are seen in other regions where the proportion has remained virtually constant and extremely high (e.g., greater than 99% in Central, Southern, Eastern and South-Eastern Asia Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) regions. See Supplementary Information for more details).

The problem, and the need for solutions, is not confined to cities: across much of the world the vast majority of people living in rural areas are also exposed to levels above the guidelines. Although there are differences when considering urban and rural areas in North America and Europe, in the vast majority of the world populations living in both urban and rural areas are exposed to levels that are above the AQGs. However, in other regions the story is very different (see Supplementary Information Fig. 7.1 and Supplementary Information Sections 7 and 8), for example population-weighted concentrations in rural areas in the Central and Southern Asia (55.5 μg/m 3 ), Sub-Saharan Africa (39.1 μg/m 3 ), Western Asia and Northern Africa (42.7 μg/m 3 ) and Eastern Asia and South-Eastern Asia (34.3 μg/m 3 ) regions (in 2016) were all considerably above the AQG. From 2010 to 2016 population-weighted concentrations in rural areas in the Central and Southern Asia region rose by approximately 11% (from 49.8 to 55.5 μg/m 3 ; see Supplementary Information Fig. 7.1 and Supplementary Information Sections 7 and 8). This is largely driven by large rural populations in India where 67.2% of the population live in rural areas 27 . Addressing air pollution in both rural and urban settings should therefore be a key priority in effectively reducing the burden of disease associated with air pollution.

Attempts to mitigate the effects of air pollution have varied according to its source and local conditions, but in all cases cooperation across sectors and at different levels, urban, regional, national and international, is crucial 28 . Policies and investments supporting affordable and sustainable access to clean energy, cleaner transport and power generation, as well as energy-efficient housing and municipal waste management can reduce key sources of outdoor air pollution. Interventions would not only improve health but also reduce climate pollutants and serve as a catalyst for local economic development and the promotion of healthy lifestyles.

Assessment of trends in global air pollution requires comprehensive information on concentrations over time for every country. This information is primarily based on ground monitoring (GM) from 9690 monitoring locations around the world from the WHO cities database for 2010–2016. However, there are regions in this may be limited if not completely unavailable, particularly for earlier years (see Supplementary Information). Even in countries where GM networks are well established, there will still be gaps in spatial coverage and missing data over time. The Data Integration Model for Air Quality (DIMAQ) supplements GM with information from other sources including estimates of PM2.5 from satellite retrievals and chemical transport models, population estimates and topography (e.g., elevation). Specifically, satellite-based estimates that combine aerosol optical depth retrievals with information from the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model 29 were used, together with estimates of sulfate, nitrate, ammonium, organic carbon and mineral dust 30 .

The most recent release of the WHO ambient air quality database, for the first time, contains data from GM for multiple years, where available The version of DIMAQ used here builds on the original version 11 , 30 by allowing data from multiple years to be modelled simultaneously, with the relationship between GMs and satellite-based estimates allowed to vary (smoothly) over time. The result is a comprehensive set of high-resolution (10 km × 10 km) estimates of PM2.5 for each year (2010–2016) for every country.

In order to produce population-weighted concentrations, a comprehensive set of population data on a high-resolution grid (Gridded Population of the World (GPW v4) database 31 ) was combined with estimates from DIMAQ. In addition, the Global Human Settlement Layer 32 was used to define areas as either urban, sub-urban or rural (based on land-use, derived from satellite images, and population estimates). A further dichotomous classification of whether grid-cells within a particular country were urban or rural (allocating sub-urban as either urban or rural) was based on providing the best alignment (at the country-level) to the estimates of urban-rural populations produced by the United Nations 27 .

It is noted that the estimates from DIMAQ used in this article may differ slightly from those used in the WHO estimates of the global burden of disease associated with ambient air pollution 1 , and the associated estimates of air pollution related SDG indicators, due to recent updates in the database and further quality assurance procedures.

Data availability

The estimates of PM 2.5 data that support the findings of this work are available from https://www.who.int/airpollution/data/en/ .

Ambient air pollution: Global assessment of exposure and BOD, update 2018. WHO (2020) (In press).

Krzyzanowski, M. & Cohen, A. Update of WHO air quality guidelines. Air Qual. Atmosphere Health 1 , 7–13 (2008).

Article Google Scholar

Zheng, Y. et al. Air quality improvements and health benefits from China’s clean air action since 2013. Environ. Res. Lett. 12 , 114020 (2017).

Turnock, S. T. et al. The impact of European legislative and technology measures to reduce air pollutants on air quality, human health and climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 11 , 024010 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Long-term trends in the ambient PM 2.5 - and O 3 -related mortality burdens in the United States under emission reductions from 1990 to 2010. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18 , 15003–15016 (2018).

Kuklinska, K., Wolska, L. & Namiesnik, J. Air quality policy in the U.S. and the EU – a review. Atmos. Pollut. Res 6 , 129–137 (2015).

Guerreiro, C. B. B., Foltescu, V. & de Leeuw, F. Air quality status and trends in Europe. Atmos. Environ. 98 , 376–384 (2014).

Byrne, A. The 1979 convention on long-range transboundary air pollution: assessing its effectiveness as a multilateral environmental regime after 35 Years. Transnatl. Environ. Law 4 , 37–67 (2015).

Crippa, M. et al. Forty years of improvements in European air quality: regional policy-industry interactions with global impacts. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16 , 3825–3841 (2016).

Butt, E. W. et al. Global and regional trends in particulate air pollution and attributable health burden over the past 50 years. Environ. Res. Lett. 12 , 104017 (2017).

Shaddick, G. et al. Data integration model for air quality: a hierarchical approach to the global estimation of exposures to ambient air pollution. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C. Appl. Stat. 67 , 231–253 (2018).

World Bank Country and Lending Groups—World Bank data. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (Accessed 3rd December 2018).

Guo, H. et al. Assessment of PM2.5 concentrations and exposure throughout China using ground observations. Sci. Total Environ. 601–602 , 1024–1030 (2017).

Ganor, E., Osetinsky, I., Stupp, A. & Alpert, P. Increasing trend of African dust, over 49 years, in the eastern Mediterranean. J. Geophys. Res. 115 , 1–7 (2010).

Google Scholar

Goudie, A. S. & Middleton, N. J. Desert Dust in the Global System . (Springer Science & Business Media, 2006).

Mahowald, N. M. et al. Observed 20th century desert dust variability: impact on climate and biogeochemistry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10 , 10875–10893 (2010).

Stanelle, T., Bey, I., Raddatz, T., Reick, C. & Tegen, I. Anthropogenically induced changes in twentieth century mineral dust burden and the associated impact on radiative forcing. J. Geophys. Res. Atmosph 119 , 13526–13546 (2014).

Air quality in Europe (European Environment Agency, 2018). https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2018 .

Particulate Matter (PM2.5) Trends | National Air Quality: Status and Trends of Key Air Pollutants | US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/air-trends/particulate-matter-pm25-trends .

Chay, K., Dobkin, C. & Greenstone, M. The clean air act of 1970 and adult mortality. J. Risk Uncertain. 27 , 279–300 (2003).

Huang, J., Pan, X., Guo, X. & Li, G. Health impact of China’s air pollution prevention and control action plan: an analysis of national air quality monitoring and mortality data. Lancet Planet. Health 2 , e313–e323 (2018).

Heal, M. R., Kumar, P. & Harrison, R. M. Particles, air quality, policy and health. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41 , 6606–6630 (2012).

Chen, J. et al. A review of biomass burning: emissions and impacts on air quality, health and climate in China. Sci. Total Environ. 579 , 1000–1034 (2017).

Zhao, B. et al. Change in household fuels dominates the decrease in PM2.5 exposure and premature mortality in China in 2005–2015. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci . 201812955 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1812955115 .

Shen, H. et al. Urbanization-induced population migration has reduced ambient PM2.5 concentrations in China. Sci. Adv. 3 , e1700300 (2017).

Burnett, R. et al. Global estimates of mortality associated with long-term exposure to outdoor fine particulate matter. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115 , 9592–9597 (2018).

World Urbanization Prospects - Population Division - United Nations. https://population.un.org/wup/Download/ (Accessed: 10th December 2018).

Towards Cleaner Air Scientific Assessment Report 2016- UNECE (2016). https://www.unece.org/index.php?id=42861 .

van Donkelaar, A. et al. Global estimates of fine particulate matter using a combined geophysical-statistical method with information from satellites, models, and monitors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50 , 3762–3772 (2016).

Shaddick, G. et al. Data Integration for the assessment for population exposure to ambient air pollution for global burden of disease assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52 , 9069–9078 (2018).

Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) Columbia University. 2016. Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4): Population Count. NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC), Palisades, NY. https://doi.org/10.7927/H4X63JVC . Accessed 3rd December 2018.

Pesaresi, M. et al. GHS Settlement grid following the REGIO model 2014 in application to GHSL Landsat and CIESIN GPW v4- multitemporal (1975-1990-2000-2015). European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC)[Dataset] http://data.europa.eu/89h/jrc-ghsl-ghs_smod_pop_globe_r2016a . Accessed: 3rd December 2018.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the WHO Data Integration Task Force, a multi-disciplinary group of experts established as part of the recommendations from the first meeting of the WHO Global Platform for Air Quality, Geneva, January 2014. The Task Force developed the Data Integration Model for Air Quality and consists of the first author, Michael Brauer, Aaron van Donkelaar, Rick Burnett, Howard H. Chang, Aaron Cohen, Rita Van Dingenen, Yang Liu, Randall Martin, Lance A. Waller, Jason West, James V. Zidek and Annette Pruss-Ustun. The authors would like to give particular thanks to Michael Brauer who provided specialist expertise, together with data on ground measurements, and Aaron van Donkelaar and the Atmospheric Composition Analysis Group at Dalhousie University for providing estimates from satellite remote sensing. The authors would also like to thank Dan Simpson for technical expertise on implementing extensions to DIMAQ. Matthew L Thomas is supported by a scholarship from the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Statistical Applied Mathematics at Bath (SAMBa), under the project EP/L015684/1. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies to institutions with which they are affiliated.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Mathematics, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

G. Shaddick

Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, Imperial College, London, UK

M. L. Thomas

World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

P. Mudu, G. Ruggeri & S. Gumy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

GS, PM, and SG conceived the project and led the writing of the manuscript. MLT and GR performed the data analysis. GS and MLT developed the statistical model used to produce the estimates. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to G. Shaddick .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shaddick, G., Thomas, M.L., Mudu, P. et al. Half the world’s population are exposed to increasing air pollution. npj Clim Atmos Sci 3 , 23 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-020-0124-2

Download citation

Received : 22 February 2019

Accepted : 01 May 2020

Published : 17 June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-020-0124-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Higher air pollution in wealthy districts of most low- and middle-income countries.

- A. Patrick Behrer

- Sam Heft-Neal

Nature Sustainability (2024)

Mineralogical Characteristics and Sources of Coarse Mode Particulate Matter in Central Himalayas

- Sakshi Gupta

- Shobhna Shankar

- Sudhir Kumar Sharma

Aerosol Science and Engineering (2024)

Role of short-term campaigns and long-term mechanisms for air pollution control: lessons learned from the “2 + 26” city cluster in China

- Yazhen Gong

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2024)

A Review of the Interactive Effects of Climate and Air Pollution on Human Health in China

- Tiantian Li

Current Environmental Health Reports (2024)

Indoor Air Pollution in Kenya

- Ibrahim Kipngeno Rotich

- Peter K. Musyimi

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

JavaScript appears to be disabled on this computer. Please click here to see any active alerts .

Air Pollution: Current and Future Challenges

Despite dramatic progress cleaning the air since 1970, air pollution in the United States continues to harm people’s health and the environment. Under the Clean Air Act, EPA continues to work with state, local and tribal governments, other federal agencies, and stakeholders to reduce air pollution and the damage that it causes.

- Learn about more about air pollution, air pollution programs, and what you can do.

Outdoor air pollution challenges facing the United States today include:

- Meeting health-based standards for common air pollutants

- Limiting climate change

- Reducing risks from toxic air pollutants

- Protecting the stratospheric ozone layer against degradation

Indoor air pollution, which arises from a variety of causes, also can cause health problems. For more information on indoor air pollution, which is not regulated under the Clean Air Act, see EPA’s indoor air web site .

Air Pollution Challenges: Common Pollutants

Great progress has been made in achieving national air quality standards, which EPA originally established in 1971 and updates periodically based on the latest science. One sign of this progress is that visible air pollution is less frequent and widespread than it was in the 1970s.

However, air pollution can be harmful even when it is not visible. Newer scientific studies have shown that some pollutants can harm public health and welfare even at very low levels. EPA in recent years revised standards for five of the six common pollutants subject to national air quality standards. EPA made the standards more protective because new, peer-reviewed scientific studies showed that existing standards were not adequate to protect public health and the environment.

Status of common pollutant problems in brief

Today, pollution levels in many areas of the United States exceed national air quality standards for at least one of the six common pollutants:

- Although levels of particle pollution and ground-level ozone pollution are substantially lower than in the past, levels are unhealthy in numerous areas of the country. Both pollutants are the result of emissions from diverse sources, and travel long distances and across state lines. An extensive body of scientific evidence shows that long- and short-term exposures to fine particle pollution, also known as fine particulate matter (PM 2.5 ), can cause premature death and harmful effects on the cardiovascular system, including increased hospital admissions and emergency department visits for heart attacks and strokes. Scientific evidence also links PM to harmful respiratory effects, including asthma attacks. Ozone can increase the frequency of asthma attacks, cause shortness of breath, aggravate lung diseases, and cause permanent damage to lungs through long-term exposure. Elevated ozone levels are linked to increases in hospitalizations, emergency room visits and premature death. Both pollutants cause environmental damage, and fine particles impair visibility. Fine particles can be emitted directly or formed from gaseous emissions including sulfur dioxide or nitrogen oxides. Ozone, a colorless gas, is created when emissions of nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds react.

- For unhealthy peak levels of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide , EPA is working with states and others on ways to determine where and how often unhealthy peaks occur. Both pollutants cause multiple adverse respiratory effects including increased asthma symptoms, and are associated with increased emergency department visits and hospital admissions for respiratory illness. Both pollutants cause environmental damage, and are byproducts of fossil fuel combustion.

- Airborne lead pollution, a nationwide health concern before EPA phased out lead in motor vehicle gasoline under Clean Air Act authority, now meets national air quality standards except in areas near certain large lead-emitting industrial facilities. Lead is associated with neurological effects in children, such as behavioral problems, learning deficits and lowered IQ, and high blood pressure and heart disease in adults.

- The entire nation meets the carbon monoxide air quality standards, largely because of emissions standards for new motor vehicles under the Clean Air Act.

In Brief: How EPA is working with states and tribes to limit common air pollutants

- EPA's air research provides the critical science to develop and implement outdoor air regulations under the Clean Air Act and puts new tools and information in the hands of air quality managers and regulators to protect the air we breathe.

- To reflect new scientific studies, EPA revised the national air quality standards for fine particles (2006, 2012), ground-level ozone (2008, 2015), sulfur dioxide (2010), nitrogen dioxide (2010), and lead (2008). After the scientific review, EPA decided to retain the existing standards for carbon monoxide. EPA strengthened the air quality standards for ground-level ozone in October 2015 based on extensive scientific evidence about ozone’s effects.

EPA has designated areas meeting and not meeting the air quality standards for the 2006 and 2012 PM standards and the 2008 ozone standard, and has completed an initial round of area designations for the 2010 sulfur dioxide standard. The agency also issues rules or guidance for state implementation of the various ambient air quality standards – for example, in March 2015, proposing requirements for implementation of current and future fine particle standards. EPA is working with states to improve data to support implementation of the 2010 sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide standards.

For areas not meeting the national air quality standards, states are required to adopt state implementation plan revisions containing measures needed to meet the standards as expeditiously as practicable and within time periods specified in the Clean Air Act (except that plans are not required for areas with “marginal” ozone levels).

- EPA is helping states to meet standards for common pollutants by issuing federal emissions standards for new motor vehicles and non-road engines, national emissions standards for categories of new industrial equipment (e.g., power plants, industrial boilers, cement manufacturing, secondary lead smelting), and technical and policy guidance for state implementation plans. EPA and state rules already on the books are projected to help 99 percent of counties with monitors meet the revised fine particle standards by 2020. The Mercury and Air Toxics Standards for new and existing power plants issued in December 2011 are achieving reductions in fine particles and sulfur dioxide as a byproduct of controls required to cut toxic emissions.

- Vehicles and their fuels continue to be an important contributor to air pollution. EPA in 2014 issued standards commonly known as Tier 3, which consider the vehicle and its fuel as an integrated system, setting new vehicle emissions standards and a new gasoline sulfur standard beginning in 2017. The vehicle emissions standards will reduce both tailpipe and evaporative emissions from passenger cars, light-duty trucks, medium-duty passenger vehicles, and some heavy-duty vehicles. The gasoline sulfur standard will enable more stringent vehicle emissions standards and will make emissions control systems more effective. These rules further cut the sulfur content of gasoline. Cleaner fuel makes possible the use of new vehicle emission control technologies and cuts harmful emissions in existing vehicles. The standards will reduce atmospheric levels of ozone, fine particles, nitrogen dioxide, and toxic pollution.

Learn more about common pollutants, health effects, standards and implementation:

- fine particles

- ground-level ozone

- sulfur dioxide

- nitrogen dioxide

- carbon monoxide

Air Pollution Challenges: Climate Change

EPA determined in 2009 that emissions of carbon dioxide and other long-lived greenhouse gases that build up in the atmosphere endanger the health and welfare of current and future generations by causing climate change and ocean acidification. Long-lived greenhouse gases , which trap heat in the atmosphere, include carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases. These gases are produced by a numerous and diverse human activities.

In May 2010, the National Research Council, the operating arm of the National Academy of Sciences, published an assessment which concluded that “climate change is occurring, is caused largely by human activities, and poses significant risks for - and in many cases is already affecting - a broad range of human and natural systems.” 1 The NRC stated that this conclusion is based on findings that are consistent with several other major assessments of the state of scientific knowledge on climate change. 2

Climate change impacts on public health and welfare

The risks to public health and the environment from climate change are substantial and far-reaching. Scientists warn that carbon pollution and resulting climate change are expected to lead to more intense hurricanes and storms, heavier and more frequent flooding, increased drought, and more severe wildfires - events that can cause deaths, injuries, and billions of dollars of damage to property and the nation’s infrastructure.

Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas pollution leads to more frequent and intense heat waves that increase mortality, especially among the poor and elderly. 3 Other climate change public health concerns raised in the scientific literature include anticipated increases in ground-level ozone pollution 4 , the potential for enhanced spread of some waterborne and pest-related diseases 5 , and evidence for increased production or dispersion of airborne allergens. 6

Other effects of greenhouse gas pollution noted in the scientific literature include ocean acidification, sea level rise and increased storm surge, harm to agriculture and forests, species extinctions and ecosystem damage. 7 Climate change impacts in certain regions of the world (potentially leading, for example, to food scarcity, conflicts or mass migration) may exacerbate problems that raise humanitarian, trade and national security issues for the United States. 8

The U.S. government's May 2014 National Climate Assessment concluded that climate change impacts are already manifesting themselves and imposing losses and costs. 9 The report documents increases in extreme weather and climate events in recent decades, with resulting damage and disruption to human well-being, infrastructure, ecosystems, and agriculture, and projects continued increases in impacts across a wide range of communities, sectors, and ecosystems.

Those most vulnerable to climate related health effects - such as children, the elderly, the poor, and future generations - face disproportionate risks. 10 Recent studies also find that certain communities, including low-income communities and some communities of color (more specifically, populations defined jointly by ethnic/racial characteristics and geographic location), are disproportionately affected by certain climate-change-related impacts - including heat waves, degraded air quality, and extreme weather events - which are associated with increased deaths, illnesses, and economic challenges. Studies also find that climate change poses particular threats to the health, well-being, and ways of life of indigenous peoples in the U.S.

The National Research Council (NRC) and other scientific bodies have emphasized that it is important to take initial steps to reduce greenhouse gases without delay because, once emitted, greenhouse gases persist in the atmosphere for long time periods. As the NRC explained in a recent report, “The sooner that serious efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions proceed, the lower the risks posed by climate change, and the less pressure there will be to make larger, more rapid, and potentially more expensive reductions later.” 11

In brief: What EPA is doing about climate change

Under the Clean Air Act, EPA is taking initial common sense steps to limit greenhouse gas pollution from large sources:

EPA and the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration between 2010 and 2012 issued the first national greenhouse gas emission standards and fuel economy standards for cars and light trucks for model years 2012-2025, and for medium- and heavy-duty trucks for 2014-2018. Proposed truck standards for 2018 and beyond were announced in June 2015. EPA is also responsible for developing and implementing regulations to ensure that transportation fuel sold in the United States contains a minimum volume of renewable fuel. Learn more about clean vehicles

EPA and states in 2011 began requiring preconstruction permits that limit greenhouse gas emissions from large new stationary sources - such as power plants, refineries, cement plants, and steel mills - when they are built or undergo major modification. Learn more about GHG permitting

- On August 3, 2015, President Obama and EPA announced the Clean Power Plan – a historic and important step in reducing carbon pollution from power plants that takes real action on climate change. Shaped by years of unprecedented outreach and public engagement, the final Clean Power Plan is fair, flexible and designed to strengthen the fast-growing trend toward cleaner and lower-polluting American energy. With strong but achievable standards for power plants, and customized goals for states to cut the carbon pollution that is driving climate change, the Clean Power Plan provides national consistency, accountability and a level playing field while reflecting each state’s energy mix. It also shows the world that the United States is committed to leading global efforts to address climate change. Learn more about the Clean Power Plan, the Carbon Pollution Standards, the Federal Plan, and model rule for states

The Clean Power Plan will reduce carbon pollution from existing power plants, the nation’s largest source, while maintaining energy reliability and affordability. The Clean Air Act creates a partnership between EPA, states, tribes and U.S. territories – with EPA setting a goal, and states and tribes choosing how they will meet it. This partnership is laid out in the Clean Power Plan.

Also on August 3, 2015, EPA issued final Carbon Pollution Standards for new, modified, and constructed power plants, and proposed a Federal Plan and model rules to assist states in implementing the Clean Power Plan.

On February 9, 2016, the Supreme Court stayed implementation of the Clean Power Plan pending judicial review. The Court’s decision was not on the merits of the rule. EPA firmly believes the Clean Power Plan will be upheld when the merits are considered because the rule rests on strong scientific and legal foundations.

On October 16, 2017, EPA proposed to repeal the CPP and rescind the accompanying legal memorandum.

EPA is implementing its Strategy to Reduce Methane Emissions released in March 2014. In January 2015 EPA announced a new goal to cut methane emissions from the oil and gas sector by 40 – 45 percent from 2012 levels by 2025, and a set of actions by EPA and other agencies to put the U.S. on a path to achieve this ambitious goal. In August 2015, EPA proposed new common-sense measures to cut methane emissions, reduce smog-forming air pollution and provide certainty for industry through proposed rules for the oil and gas industry . The agency also proposed to further reduce emissions of methane-rich gas from municipal solid waste landfills . In March 2016 EPA launched the National Gas STAR Methane Challenge Program under which oil and gas companies can make, track and showcase ambitious commitments to reduce methane emissions.

EPA in July 2015 finalized a rule to prohibit certain uses of hydrofluorocarbons -- a class of potent greenhouse gases used in air conditioning, refrigeration and other equipment -- in favor of safer alternatives. The U.S. also has proposed amendments to the Montreal Protocol to achieve reductions in HFCs internationally.

Learn more about climate science, control efforts, and adaptation on EPA’s climate change web site

Air Pollution Challenges: Toxic Pollutants

While overall emissions of air toxics have declined significantly since 1990, substantial quantities of toxic pollutants continue to be released into the air. Elevated risks can occur in urban areas, near industrial facilities, and in areas with high transportation emissions.

Numerous toxic pollutants from diverse sources

Hazardous air pollutants, also called air toxics, include 187 pollutants listed in the Clean Air Act. EPA can add pollutants that are known or suspected to cause cancer or other serious health effects, such as reproductive effects or birth defects, or to cause adverse environmental effects.

Examples of air toxics include benzene, which is found in gasoline; perchloroethylene, which is emitted from some dry cleaning facilities; and methylene chloride, which is used as a solvent and paint stripper by a number of industries. Other examples of air toxics include dioxin, asbestos, and metals such as cadmium, mercury, chromium, and lead compounds.

Most air toxics originate from manmade sources, including mobile sources such as motor vehicles, industrial facilities and small “area” sources. Numerous categories of stationary sources emit air toxics, including power plants, chemical manufacturing, aerospace manufacturing and steel mills. Some air toxics are released in large amounts from natural sources such as forest fires.

Health risks from air toxics

EPA’s most recent national assessment of inhalation risks from air toxics 12 estimated that the whole nation experiences lifetime cancer risks above ten in a million, and that almost 14 million people in more than 60 urban locations have lifetime cancer risks greater than 100 in a million. Since that 2005 assessment, EPA standards have required significant further reductions in toxic emissions.

Elevated risks are often found in the largest urban areas where there are multiple emission sources, communities near industrial facilities, and/or areas near large roadways or transportation facilities. Benzene and formaldehyde are two of the biggest cancer risk drivers, and acrolein tends to dominate non-cancer risks.

In brief: How EPA is working with states and communities to reduce toxic air pollution

EPA standards based on technology performance have been successful in achieving large reductions in national emissions of air toxics. As directed by Congress, EPA has completed emissions standards for all 174 major source categories, and 68 categories of small area sources representing 90 percent of emissions of 30 priority pollutants for urban areas. In addition, EPA has reduced the benzene content in gasoline, and has established stringent emission standards for on-road and nonroad diesel and gasoline engine emissions that significantly reduce emissions of mobile source air toxics. As required by the Act, EPA has completed residual risk assessments and technology reviews covering numerous regulated source categories to assess whether more protective air toxics standards are warranted. EPA has updated standards as appropriate. Additional residual risk assessments and technology reviews are currently underway.

EPA also encourages and supports area-wide air toxics strategies of state, tribal and local agencies through national, regional and community-based initiatives. Among these initiatives are the National Clean Diesel Campaign , which through partnerships and grants reduces diesel emissions for existing engines that EPA does not regulate; Clean School Bus USA , a national partnership to minimize pollution from school buses; the SmartWay Transport Partnership to promote efficient goods movement; wood smoke reduction initiatives; a collision repair campaign involving autobody shops; community-scale air toxics ambient monitoring grants ; and other programs including Community Action for a Renewed Environment (CARE). The CARE program helps communities develop broad-based local partnerships (that include business and local government) and conduct community-driven problem solving as they build capacity to understand and take effective actions on addressing environmental problems.

Learn more about air toxics, stationary sources of emissions, and control efforts Learn more about mobile source air toxics and control efforts

Air Pollution Challenges: Protecting the Stratospheric Ozone Layer

The ozone (O 3 ) layer in the stratosphere protects life on earth by filtering out harmful ultraviolet radiation (UV) from the sun. When chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other ozone-degrading chemicals are emitted, they mix with the atmosphere and eventually rise to the stratosphere. There, the chlorine and the bromine they contain initiate chemical reactions that destroy ozone. This destruction has occurred at a more rapid rate than ozone can be created through natural processes, depleting the ozone layer.

The toll on public health and the environment

Higher levels of ultraviolet radiation reaching Earth's surface lead to health and environmental effects such as a greater incidence of skin cancer, cataracts, and impaired immune systems. Higher levels of ultraviolet radiation also reduce crop yields, diminish the productivity of the oceans, and possibly contribute to the decline of amphibious populations that is occurring around the world.

In brief: What’s being done to protect the ozone layer

Countries around the world are phasing out the production of chemicals that destroy ozone in the Earth's upper atmosphere under an international treaty known as the Montreal Protocol . Using a flexible and innovative regulatory approach, the United States already has phased out production of those substances having the greatest potential to deplete the ozone layer under Clean Air Act provisions enacted to implement the Montreal Protocol. These chemicals include CFCs, halons, methyl chloroform and carbon tetrachloride. The United States and other countries are currently phasing out production of hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), chemicals being used globally in refrigeration and air-conditioning equipment and in making foams. Phasing out CFCs and HCFCs is also beneficial in protecting the earth's climate, as these substances are also very damaging greenhouse gases.

Also under the Clean Air Act, EPA implements regulatory programs to:

Ensure that refrigerants and halon fire extinguishing agents are recycled properly.

Ensure that alternatives to ozone-depleting substances (ODS) are evaluated for their impacts on human health and the environment.

Ban the release of ozone-depleting refrigerants during the service, maintenance, and disposal of air conditioners and other refrigeration equipment.

Require that manufacturers label products either containing or made with the most harmful ODS.

These vital measures are helping to protect human health and the global environment.

The work of protecting the ozone layer is not finished. EPA plans to complete the phase-out of ozone-depleting substances that continue to be produced, and continue efforts to minimize releases of chemicals in use. Since ozone-depleting substances persist in the air for long periods of time, the past use of these substances continues to affect the ozone layer today. In our work to expedite the recovery of the ozone layer, EPA plans to augment CAA implementation by:

Continuing to provide forecasts of the expected risk of overexposure to UV radiation from the sun through the UV Index, and to educate the public on how to protect themselves from over exposure to UV radiation.

Continuing to foster domestic and international partnerships to protect the ozone layer.

Encouraging the development of products, technologies, and initiatives that reap co-benefits in climate change and energy efficiency.

Learn more About EPA’s Ozone Layer Protection Programs

Some of the following links exit the site

1 National Research Council (2010), Advancing the Science of Climate Change , National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., p. 3.

2 National Research Council (2010), Advancing the Science of Climate Change , National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., p. 286.

3 USGCRP (2009). Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States . Karl, T.R., J.M. Melillo, and T.C. Peterson (eds.). United States Global Change Research Program. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA.

4 CCSP (2008). Analyses of the effects of global change on human health and welfare and human systems . A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. Gamble, J.L. (ed.), K.L. Ebi, F.G. Sussman, T.J. Wilbanks, (Authors). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, USA.

5 Confalonieri, U., B. Menne, R. Akhtar, K.L. Ebi, M. Hauengue, R.S. Kovats, B. Revich and A. Woodward (2007). Human health. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability . Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Parry, M.L., O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, (eds.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

7 An explanation of observed and projected climate change and its associated impacts on health, society, and the environment is included in the EPA’s Endangerment Finding and associated technical support document (TSD). See EPA, “ Endangerment and Cause or Contribute Findings for Greenhouse Gases under Section 202(a) of the Clean Air Act ,” 74 FR 66496, Dec. 15, 2009. Both the Federal Register Notice and the Technical Support Document (TSD) for Endangerment and Cause or Contribute Findings are found in the public docket, Docket No. EPA-OAR-2009-0171.

8 EPA, Endangerment Finding , 74 FR 66535.

9 . U.S. Global Change Research Program, Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment , May 2014.

10 EPA, Endangerment Finding , 74 FR 66498.

11 National Research Council (2011) America’s Climate Choices: Report in Brief , Committee on America’s Climate Choices, Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, Division on Earth and Life Studies, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., p. 2.

12 EPA, 2005 National-Scale Air Toxics Assessment (2011).

- Clean Air Act Overview Home

- Progress Cleaning the Air

- Air Pollution Challenges

- Requirements and History

- Role of Science and Technology

- Roles of State, Local, Tribal and Federal Governments

- Developing Programs Through Dialogue

- Flexibility with Accountability

- The Clean Air Act and the Economy

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Sample Essay on Pollution in 250- 300 Words. The biggest threat planet earth is facing is pollution. Unwanted substances leave a negative impact once released into an environment. There are four types of pollution air, water, land, and noise. Pollution affects the quality of life more than any human can imagine.

Air pollution is high on the global agenda and is widely recognised as a threat to both public health and economic progress. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 4.2 million deaths ...

Outdoor air pollution challenges facing the United States today include: Meeting health-based standards for common air pollutants. Limiting climate change. Reducing risks from toxic air pollutants. Protecting the stratospheric ozone layer against degradation. Indoor air pollution, which arises from a variety of causes, also can cause health ...