The Declaration of Independence

21 pages • 42 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Essay Analysis

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Literary Devices

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

In what ways is the Declaration of Independence a timeless document, and in what ways is it a product of a specific time and place? Is it primarily a historical document, or is it relevant to the modern era?

How does the Declaration of Independence define a tyrant? And how convincing is the argument the signers make that George III was a tyrant?

The Declaration of Independence does not establish any laws for the United States. But how do its ideas influence the Constitution or other documents that do establish laws?

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Thomas Jefferson

Notes on the State of Virginia

Thomas Jefferson

Featured Collections

American Revolution

View Collection

Books on Justice & Injustice

Books on U.S. History

Nation & Nationalism

Politics & Government

Required Reading Lists

103 Declaration of Independence Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best declaration of independence topic ideas & essay examples, ⭐ good research topics about declaration of independence, 👍 simple & easy declaration of independence essay titles, ❓ declaration of independence essay questions.

- Rhetoric of The Declaration of Independence Other than appealing to ethics, Jefferson and the founding fathers required the audience to have an emotional attachment to the Declaration of Independence.

- Stylistic Devices Used in the Declaration of Independence The use of rhythm in the Declaration of Independence is used with the intention of emphasizing the points the author is making. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Similarities and Differences Between the English Bill of Rights and the American Declaration of Independence The document, the English Bill of Rights, was ratified in the year 1689 by the English parliament. The American Declaration of Independence, like the English Bill of Rights, safeguarded the right of subjects to participate […]

- Parallelism in the Declaration of Independence This is the technique that Jefferson uses in writing the Declaration of Independence. In using this technique Jefferson enumerates to illustrate the patience of an oppressed people.

- The Declaration of Independence and 1984 by George Orwell Another feature that relates the Declaration of Independence to 1984 is a demonstration of the tyranny of the ruler and the restriction of the citizen’s rights.

- Declaration of Independence: All Men Are Created Equal However Jefferson and the other signers of the declaration could not probably believe this at a time when slavery existed in the colonies.

- Thomas Jefferson Argument in the Declaration of Independence The first argument was that the Great Britain was taking advantage of the communities in the colonies because they could only export their produce to the Great Britain.

- Why Was the Declaration of Independence Written? The Declaration was to serve as a notice to all the nations of the world that the American Colonies were proclaiming their independence from the British Colonists.

- The US Declaration of Independence Analysis This is the first document in history that proclaimed the principle of popular sovereignty as the basis of the state system and rejected the theory of the divine origin of power.

- Thomas Jefferson on Slavery and Declaration of Independence Additionally, with the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson set the foundation for the abolition of slavery in the future. Thus, the claim that Jefferson’s participation in slavery invalidates his writing of the Declaration of Independence is […]

- The Struggles Before the Declaration of Independence The tension grew up from the end of the 1760s when capitalism and the formation of the North American nation came into conflict with the policy of the metropolis.

- The Declaration of Independence, the Aim of Political Groups The historic politician played a key role in promoting equality in the United States and the world. The phrase “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed” was […]

- English Bill of Rights vs. American Declaration of Independence In a sense, the American constitution is the fruition of the struggle of the people to dispense with the monarchy and privileged aristocracy and it is the voice of an authentic Republic.

- The Declaration of Independence: Document Reaction The declaration of independence was written by Thomas Jefferson and was later adopted by the second continental congress and this declaration of independence illustrates the main reasons that pushed the colonies of the United Kingdom […]

- Texas Declaration of Independence The core issue of the Declaration of Texas Independence is the proclamation of independence itself and the definition of responsibilities and functions of the new Government.

- The Original and the Edited Declarations of Independence The Declaration of Independence was an assertion that there was no more war between the thirteen states and Great Britain and that these states were free and sovereign states.

- Declaration of Independence: Self-Evident Truths Now Open to Question According to Becker, among man’s inalienable rights set in the Declaration as self-evident truths were the freedom of speech and expression, the right to religion and conscience, the right of assembly, the right to equal […]

- Jefferson and Writing the Declaration of Independence Thomas Jefferson was a prominent political leader of the 18th century who made his name in the history of United States of America by drafting the famous Declaration of Independence.

- Declaration of Independence for USA Analysis Even the Declaration of Independence for the United States of America states that “…whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish […]

- The Use of Logic in the Declaration of Independence: Following Jefferson’s Argument By emphasizing the notions of egalitarianism and the principles of natural law, Jefferson successfully appeals to logic and makes a convincing presentation of the crucial social and legal principles to his opposition.

- The History of U.S. Declaration of Independence On July 4, 1776, in Philadelphia, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America from Great Britain and its Crown.

- Declaration of Independence – Reason and Significance The main reason for declaring independence against Great Britain was the people’s dissatisfaction with the governing and taxes introduced by it.

- The American Declaration of Independence ‘The Declaration of Independence’ is one of the importance documents in the history of America as it has laid a foundation to a better constitution.

- Declaration of Independence in American History The question as to whether the United States has lived up to the promise of liberty and opportunity for all its citizens can be analyzed by critically looking into a number of issues that the […]

- Political Philosophy: US Declaration of Independence In the assumption of legitimate political power, a state has the right to develop laws and measures to be used for the purpose of controlling and conserving individual or public property.

- Declaration of Independence Content The accusation section discloses to the reader a leader who is authoritative, that is, he does not consider the interests of others.

- Key Ideas in the Declaration of Independence In addition, the compulsion of change that finally led to the declaration of independence based on the consent of the governed.

- Declaration of Independence: Thomas Paine, Common Sense and Thomas Jefferson On top of the list is the call for Americans to pay taxes that would oversee the funding of Britain’s defence.

- Thomas Paine, Common Sense and Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence He employs literal imagery and creates arguments to show that Monarchy was of no use and that England was of no help to the colonies.

- The Declaration of Independence The norms which are presented in the Declaration were connected with all the aspects of the development of the American society in the 18th century.

- Declaration of Independence – Constitution Thirteen to 22 abuses describe in detail the use of parliament by the King to destroy the colonies’ right to independence.

- United States Declaration of Independence The main aim was to declare the necessity for independence especially to the colonist as well as to state their view and position on the purpose of the government.

- The Declaration of Independence: The Three Copies and Drafts, and Their Relation to Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” Furthermore, as opposed to the first draft, both the reported draft and the engrossed copy contain the additional phrase “without the consent of our legislatures”, to the argument of the King placing standing armies amongst […]

- Freedom and Equality Among Men in the Declaration of Independence

- Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography and the Declaration of Independence

- Abigail Adams Before the Declaration of Independence

- How Has the Declaration of Independence Influenced the Oppression in America

- Accusations Against King George in the Declaration of Independence

- Pursuing Democratic Principles From Declaration of Independence to the U.S. Constitution

- President Thomas Jefferson and His Declaration of Independence

- The Fight for Equality: From the Declaration of Independence to a Letter From a Birmingham Jail

- The Risks, Challenges, and Benefits That Came With the Declaration of Independence in the U.S.

- United States Declaration of Independence and Rhetorical Analysis

- Equality: United States Declaration of Independence and Sexual Orientation

- Analyzing the Style and Virtue of the Declaration of Independence

- The Meaning Rings True: An Analysis of Text Within the Declaration of Independence and Its Relationship to Modern Events

- Declaration of Independence: Right to Institute New Government

- The Constitution and the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America

- Abolitionism: United States Declaration of Independence and Modern Equivalent

- Comparing the Three Most Important Documents in the History of the U.S.: The Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and the Declaration of Independence

- The Declaration of Independence: The Ideals of the United States and the Reasons for Separation From Great Britain

- Analyzing the Structure and Language of the Declaration of Independence

- How the American Declaration of Independence Affected the World

- Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness for the People in the Declaration of Independence

- The Natural Rights, Popular Sovereignty, and Social Contract as the Foundation of the Declaration of Independence

- “All Men Are Created Equal” – Human Rights in the United States Declaration of Independence

- The Hypocrisy Behind the Creation of the American Declaration of Independence

- God, Government and the United States Declaration of Independence

- Emancipation Proclamation and the Declaration of Independence: Comparison

- Separation From England and Declaration of Independence

- Racial Tension and the Declaration of Independence

- Modern America Has Not Been Living up to the Five Ideas Expressed in the Declaration of Independence

- Reasons for Writing the Declaration of Independence

- Slavery and the Declaration of Independence for the American Revolution

- Five American Thinkers and How They Employed the Declaration of Independence Into Their Writings

- The Laws and Rules in the Declaration of Independence

- Enlightenment, Romanticism, and the American Declaration of Independence

- The Key Aspects That Changes the American Lives in the Declaration of Independence

- The Constitution of the United States and the Declaration of Independence

- Native Americans and the Declaration of Independence

- The Original Objectives and Historical Importance of the Declaration of Independence in America

- The American Dream and the Declaration of Independence

- Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence

- Who Was the Author of the Declaration of Independence?

- What Impact Did the Declaration of Independence Have on Society?

- How Did the Declaration of Independence Impact Human Rights?

- When Was the Declaration of Independence of the United States?

- Does the Declaration of Independence Make All Men Equal?

- How Did the Declaration of Independence Affect Oppression in America?

- How Does the Declaration of Independence Reflect the American Dream?

- How Did the American Declaration of Independence Affect the World?

- What Was John Locke’s Contribution to the Declaration of Independence?

- How Can You Analyze the Style and Merits of the Declaration of Independence?

- What Was Benjamin Franklin’s Role in the Declaration of Independence?

- Why Is the Declaration of Independence One of the Most Important Documents in Us History?

- When and Where Was the Declaration of Independence Adopted?

- What Events Preceded the Declaration of Independence?

- Who Signed the United States Declaration of Independence?

- Why Is the Declaration of Independence Important?

- How Did American Thinkers Use the Declaration of Independence in Their Writings?

- How Did the Petition of Rights Influence the Declaration of Independence?

- Where to See the Original Declaration of Independence?

- What Ideas Were Expressed in the Declaration of Independence?

- What Were the Reasons Behind the Declaration of Independence??

- What Was the Partisan Politics of the United States During the Declaration of Independence?

- What Are the Causes and Effects of Vietnam’s Declaration of Independence?

- Why Is the Declaration of Independence a Symbol of Freedom?

- What Issues Were Considered When Writing the Declaration of Independence?

- What Values of American Society Are Reflected in the Declaration of Independence?

- What Were the Original Goals of the Declaration of Independence?

- How Did the Declaration of Independence Impact the Lives of African Americans?

- What Is the Purpose of the American Declaration of Independence?

- What Part of the US Constitution Is Similar to the Declaration of Rights?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, September 26). 103 Declaration of Independence Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/declaration-of-independence-essay-topics/

"103 Declaration of Independence Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Sept. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/declaration-of-independence-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '103 Declaration of Independence Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 September.

IvyPanda . 2023. "103 Declaration of Independence Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/declaration-of-independence-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "103 Declaration of Independence Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/declaration-of-independence-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "103 Declaration of Independence Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/declaration-of-independence-essay-topics/.

- American Revolution Topics

- Bill of Rights Research Ideas

- Patriotism Research Ideas

- Thomas Jefferson Ideas

- US History Topics

- Thomas Paine Research Ideas

- Benjamin Franklin Titles

- Alexander Hamilton Ideas

- Republican Party Paper Topics

- 1984 Essay Titles

- Freedom Topics

- Equality Topics

- Women’s Rights Titles

- Oppression Research Topics

- Constitution Research Ideas

- Utility Menu

Text of the Declaration of Independence

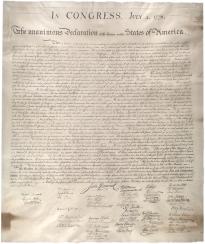

Note: The source for this transcription is the first printing of the Declaration of Independence, the broadside produced by John Dunlap on the night of July 4, 1776. Nearly every printed or manuscript edition of the Declaration of Independence has slight differences in punctuation, capitalization, and even wording. To find out more about the diverse textual tradition of the Declaration, check out our Which Version is This, and Why Does it Matter? resource.

WHEN in the Course of human Events, it becomes necessary for one People to dissolve the Political Bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the Separation. We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness—-That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient Causes; and accordingly all Experience hath shewn, that Mankind are more disposed to suffer, while Evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the Forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future Security. Such has been the patient Sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the Necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The History of the present King of Great-Britain is a History of repeated Injuries and Usurpations, all having in direct Object the Establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid World. He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public Good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing Importance, unless suspended in their Operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other Laws for the Accommodation of large Districts of People, unless those People would relinquish the Right of Representation in the Legislature, a Right inestimable to them, and formidable to Tyrants only. He has called together Legislative Bodies at Places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the Depository of their public Records, for the sole Purpose of fatiguing them into Compliance with his Measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly Firmness his Invasions on the Rights of the People. He has refused for a long Time, after such Dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the Dangers of Invasion from without, and Convulsions within. He has endeavoured to prevent the Population of these States; for that Purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their Migrations hither, and raising the Conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the Tenure of their Offices, and the Amount and Payment of their Salaries. He has erected a Multitude of new Offices, and sent hither Swarms of Officers to harrass our People, and eat out their Substance. He has kept among us, in Times of Peace, Standing Armies, without the consent of our Legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a Jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution, and unacknowledged by our Laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large Bodies of Armed Troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from Punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all Parts of the World: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us, in many Cases, of the Benefits of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended Offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an arbitrary Government, and enlarging its Boundaries, so as to render it at once an Example and fit Instrument for introducing the same absolute Rule into these Colonies: For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with Power to legislate for us in all Cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People. He is, at this Time, transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the Works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy, scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous Ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized Nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the Executioners of their Friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic Insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction, of all Ages, Sexes and Conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions we have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble Terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated Injury. A Prince, whose Character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the Ruler of a free People. Nor have we been wanting in Attentions to our British Brethren. We have warned them from Time to Time of Attempts by their Legislature to extend an unwarrantable Jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the Circumstances of our Emigration and Settlement here. We have appealed to their native Justice and Magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the Ties of our common Kindred to disavow these Usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our Connections and Correspondence. They too have been deaf to the Voice of Justice and of Consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the Necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of Mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace, Friends. We, therefore, the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the World for the Rectitude of our Intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly Publish and Declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States; that they are absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political Connection between them and the State of Great-Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Signed by Order and in Behalf of the Congress, JOHN HANCOCK, President.

Attest. CHARLES THOMSON, Secretary.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Declaration of Independence

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 28, 2023 | Original: October 27, 2009

The Declaration of Independence was the first formal statement by a nation’s people asserting their right to choose their own government.

When armed conflict between bands of American colonists and British soldiers began in April 1775, the Americans were ostensibly fighting only for their rights as subjects of the British crown. By the following summer, with the Revolutionary War in full swing, the movement for independence from Britain had grown, and delegates of the Continental Congress were faced with a vote on the issue. In mid-June 1776, a five-man committee including Thomas Jefferson , John Adams and Benjamin Franklin was tasked with drafting a formal statement of the colonies’ intentions. The Congress formally adopted the Declaration of Independence—written largely by Jefferson—in Philadelphia on July 4 , a date now celebrated as the birth of American independence.

America Before the Declaration of Independence

Even after the initial battles in the Revolutionary War broke out, few colonists desired complete independence from Great Britain, and those who did–like John Adams– were considered radical. Things changed over the course of the next year, however, as Britain attempted to crush the rebels with all the force of its great army. In his message to Parliament in October 1775, King George III railed against the rebellious colonies and ordered the enlargement of the royal army and navy. News of his words reached America in January 1776, strengthening the radicals’ cause and leading many conservatives to abandon their hopes of reconciliation. That same month, the recent British immigrant Thomas Paine published “Common Sense,” in which he argued that independence was a “natural right” and the only possible course for the colonies; the pamphlet sold more than 150,000 copies in its first few weeks in publication.

Did you know? Most Americans did not know Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence until the 1790s; before that, the document was seen as a collective effort by the entire Continental Congress.

In March 1776, North Carolina’s revolutionary convention became the first to vote in favor of independence; seven other colonies had followed suit by mid-May. On June 7, the Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee introduced a motion calling for the colonies’ independence before the Continental Congress when it met at the Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall) in Philadelphia. Amid heated debate, Congress postponed the vote on Lee’s resolution and called a recess for several weeks. Before departing, however, the delegates also appointed a five-man committee–including Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and Robert R. Livingston of New York–to draft a formal statement justifying the break with Great Britain. That document would become known as the Declaration of Independence.

Thomas Jefferson Writes the Declaration of Independence

Jefferson had earned a reputation as an eloquent voice for the patriotic cause after his 1774 publication of “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” and he was given the task of producing a draft of what would become the Declaration of Independence. As he wrote in 1823, the other members of the committee “unanimously pressed on myself alone to undertake the draught [sic]. I consented; I drew it; but before I reported it to the committee I communicated it separately to Dr. Franklin and Mr. Adams requesting their corrections….I then wrote a fair copy, reported it to the committee, and from them, unaltered to the Congress.”

As Jefferson drafted it, the Declaration of Independence was divided into five sections, including an introduction, a preamble, a body (divided into two sections) and a conclusion. In general terms, the introduction effectively stated that seeking independence from Britain had become “necessary” for the colonies. While the body of the document outlined a list of grievances against the British crown, the preamble includes its most famous passage: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The Continental Congress Votes for Independence

The Continental Congress reconvened on July 1, and the following day 12 of the 13 colonies adopted Lee’s resolution for independence. The process of consideration and revision of Jefferson’s declaration (including Adams’ and Franklin’s corrections) continued on July 3 and into the late morning of July 4, during which Congress deleted and revised some one-fifth of its text. The delegates made no changes to that key preamble, however, and the basic document remained Jefferson’s words. Congress officially adopted the Declaration of Independence later on the Fourth of July (though most historians now accept that the document was not signed until August 2).

The Declaration of Independence became a significant landmark in the history of democracy. In addition to its importance in the fate of the fledgling American nation, it also exerted a tremendous influence outside the United States, most memorably in France during the French Revolution . Together with the Constitution and the Bill of Rights , the Declaration of Independence can be counted as one of the three essential founding documents of the United States government.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Declaration of Independence

What were the philos

Guiding Question:

- What were the philosophical bases and practical purposes of the Declaration of Independence?

- Students will examine the philosophical bases and practical purposes of the Declaration of Independence by analyzing key passages from the document.

Expand Materials Materials

Student materials.

- Background Essay: Declaration of Independence

- Background Essay Graphic Organizer and Questions

Declaration Preamble and Grievances Organizer: Versions A and B

Thomas jefferson looks back on the declaration of independence.

- Appendix C: The Declaration of Independence, with Line Numbers

Teacher Resources

- The Declaration of Independence Answer Key

Expand More Information More Information

For students who need additional scaffolding in vocabulary and reading comprehension, this lesson plan suggests having students interview three people as preparatory work and read the essay and accompanying organizer in class. Stronger readers can complete the essay and accompanying organizer for homework and begin class by posing the question “What does the Fourth of July mean to you?” to classmates and then having a class discussion. Two versions of the graphic organizer are provided for the second part of the activity. Version A contains shorter excerpts. Version B can be used with stronger readers. Students will consult Appendix A: Founding Principles and Civic Virtues Organizer and Appendix B: Being an American Unit Graphic Organizer from the first lesson in this curriculum.

Expand Prework Prework

Have students ask three people (siblings, friends, teachers, coaches, parents, etc.) what the Fourth of July means to them.

Expand Warmup Warmup

Allow students 5 minutes to discuss their answers to the homework question with a partner or in small groups, as best fits your classroom. When time has passed, ask students to share their responses with the class. Encourage students to look for patterns and move the conversation to the focus of the holiday being the celebration of ideals and principles in the Declaration of Independence.

Expand Activities Activities

- Distribute Background Essay and Background Essay Graphic Organizer and Questions to students. Have students look at the timeline, headers, and images to predict main ideas and concepts they will see in the essay. Read the essay aloud as a class or have students read individually (this can also be done as preparatory work for stronger readers). Students should complete the accompanying graphic organizer as they read. After reading, give students time to complete the three concluding questions on main ideas. Lead a brief discussion on the answers.

- Distribute Declaration Preamble and Grievances Organizer , either Version A or Version B. Complete the introduction and Preamble together (the introduction has been filled out as an example). Divide the class into pairs/small groups, and assign each group one section of the Declaration in the organizer. You may wish to have pairs/groups put their information on a poster or PowerPoint slide for ease of sharing with the class. After completing their assigned section(s), have groups share out to the class.

- Have students complete the concluding questions after the organizer. Lead a brief discussion on student answers.

Expand Wrap Up Wrap Up

Assess & reflect.

- Have students return to Appendix A: Founding Principles and Civic Virtues Organizer from the first lesson in this curriculum and complete the definitions of liberty and equality based on what they learned in this activity.

- Have students return to Appendix B: Being an American Unit Graphic Organizer from the first lesson in this curriculum and complete the applicable row as an exit ticket.

Expand Homework Homework

- Challenge students to find or take pictures of scenes that illustrate the main ideas of the Declaration of Independence. Post pictures to a class site or compile into a mural or collage.

- Have students research specific grievances listed in the Declaration.

- Have students research an individual who signed the Declaration of Independence and write a one- to two-page biography.

- Have students complete Thomas Jefferson Looks Back on the Declaration of Independence .

Student Handouts

Background essay: the declaration of independence, background essay graphic organizer and questions: the declaration of independence.

Next Lesson

The Guiding Star of Equality: The Declaration of Independence and Equality in U.S. History

Related resources.

Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence

Why did the colonists declare independence from Britain?

Declaration of Independence

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee brought what came to be called the Lee Resolution before the Continental Congress. This resolution stated “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states ...” Congress debated independence for several days.

The Declaration of Independence Explained | A Primary Source Close Read w/ BRI

What was the Continental Congress's argument for Independence? Join Kirk Higgins, as he takes a line by line look at the the Declaration of Independence.

America's Founding Documents

Declaration of Independence: A Transcription

Note: The following text is a transcription of the Stone Engraving of the parchment Declaration of Independence (the document on display in the Rotunda at the National Archives Museum .) The spelling and punctuation reflects the original.

In Congress, July 4, 1776

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.--Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Button Gwinnett

George Walton

North Carolina

William Hooper

Joseph Hewes

South Carolina

Edward Rutledge

Thomas Heyward, Jr.

Thomas Lynch, Jr.

Arthur Middleton

Massachusetts

John Hancock

Samuel Chase

William Paca

Thomas Stone

Charles Carroll of Carrollton

George Wythe

Richard Henry Lee

Thomas Jefferson

Benjamin Harrison

Thomas Nelson, Jr.

Francis Lightfoot Lee

Carter Braxton

Pennsylvania

Robert Morris

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Franklin

John Morton

George Clymer

James Smith

George Taylor

James Wilson

George Ross

Caesar Rodney

George Read

Thomas McKean

William Floyd

Philip Livingston

Francis Lewis

Lewis Morris

Richard Stockton

John Witherspoon

Francis Hopkinson

Abraham Clark

New Hampshire

Josiah Bartlett

William Whipple

Samuel Adams

Robert Treat Paine

Elbridge Gerry

Rhode Island

Stephen Hopkins

William Ellery

Connecticut

Roger Sherman

Samuel Huntington

William Williams

Oliver Wolcott

Matthew Thornton

Back to Main Declaration Page

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

The Declaration of Independence

By tim bailey, view the declaration in the gilder lehrman collection by clicking here and here . for additional primary resources click here and here ., unit objective.

This unit is part of Gilder Lehrman’s series of Common Core State Standards–based teaching resources. These units were written to enable students to understand, summarize, and analyze original texts of historical significance. Students will demonstrate this knowledge by writing summaries of selections from the original document and, by the end of the unit, articulating their understanding of the complete document by answering questions in an argumentative writing style to fulfill the Common Core State Standards. Through this step-by-step process, students will acquire the skills to analyze any primary or secondary source material.

While the unit is intended to flow over a five-day period, it is possible to present and complete the material within a shorter time frame. For example, the first two days can be used to ensure an understanding of the process with all of the activity completed in class. The teacher can then assign lessons three and four as homework. The argumentative essay is then written in class on day three.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of the Declaration of Independence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In the first lesson this will be facilitated by the teacher and done as a whole-class lesson.

Introduction

Tell the students that they will be learning what Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1776 that served to announce the creation of a new nation by reading and understanding Jefferson’s own words. Resist the temptation to put the Declaration into too much context. Remember, we are trying to let the students discover what Jefferson and the Continental Congress had to say and then develop ideas based solely on the original text.

- The Declaration of Independence, abridged (PDF)

- Teacher Resource: Complete text of the Declaration of Independence (PDF). This transcript of the Declaration of Independence is from the National Archives online resource The Charters of Freedom .

- Summary Organizer #1 (PDF)

- All students are given an abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The teacher then "share reads" the text with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a few sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the students will be analyzing the first part of the text today and that they will be learning how to do in-depth analysis for themselves. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #1. This contains the first selection from the Declaration of Independence.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #1 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today the whole class will be going through this process together.

- Explain that the objective is to select "Key Words" from the first section and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in the first paragraph.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: Key Words are very important contributors to understanding the text. Without them the selection would not make sense. These words are usually nouns or verbs. Don’t pick "connector" words (are, is, the, and, so, etc.). The number of Key Words depends on the length of the original selection. This selection is 181 words so we can pick ten Key Words. The other Key Words rule is that we cannot pick words if we don’t know what they mean.

- Students will now select ten words from the text that they believe are Key Words and write them in the box to the right of the text on their organizers.

- The teacher surveys the class to find out what the most popular choices were. The teacher can either tally this or just survey by a show of hands. Using this vote and some discussion the class should, with guidance from the teacher, decide on ten Key Words. For example, let’s say that the class decides on the following words: necessary, dissolve, political bonds (yes, technically these are two words, but you can allow such things if it makes sense to do so; just don’t let whole phrases get by), declare, separation, self-evident, created equal, liberty, abolish, and government. Now, no matter which words the students had previously selected, have them write the words agreed upon by the class or chosen by you into the Key Words box in their organizers.

- The teacher now explains that, using these Key Words, the class will write a sentence that restates or summarizes what was stated in the Declaration. This should be a whole-class discussion-and-negotiation process. For example, "It is necessary for us to dissolve our political bonds and declare a separation; it is self-evident that we are created equal and should have liberty, so we need to abolish our current government." You might find that the class decides they don’t need the some of the words to make it even more streamlined. This is part of the negotiation process. The final negotiated sentence is copied into the organizer in the third section under the original text and Key Words sections.

- The teacher explains that students will now be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. Again, this is a class discussion-and-negotiation process. For example, "We need to get rid of our old government so we can be free."

- Wrap up: Discuss vocabulary that the students found confusing or difficult. If you choose, you could have students use the back of their organizers to make a note of these words and their meanings.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of what Thomas Jefferson was writing about in the Declaration of Independence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In the second lesson the students will work with partners and in small groups.

Tell the students that they will be further exploring the meaning of the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s text and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working with partners and in small groups.

- Summary Organizer #2 (PDF)

- All students are given the abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first selection.

- The teacher then "share reads" the second selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the second selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #2. This contains the second selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #2 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday but with partners and in small groups.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the second selection and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. However, because this paragraph is shorter than the last one at 148 words, they can pick only seven or eight Key Words.

- Pair the students up and have them negotiate which Key Words to select. After they have decided on their words both students will write them in the Key Words box of their organizers.

- The teacher now puts two pairs together. These two pairs go through the same negotiation-and-discussion process to come up with their Key Words. Be strategic in how you make your groups to ensure the most participation by all group members.

- The teacher now explains that by using these Key Words the group will build a sentence that restates or summarizes what Thomas Jefferson was saying. This is done by the group negotiating with its members on how best to build that sentence. Try to make sure that everyone is contributing to the process. It is very easy for one student to take control of the entire process and for the other students to let them do so. All of the students should write their negotiated sentence into their organizers.

- The teacher asks for the groups to share out the summary sentences they have created. This should start a teacher-led discussion that points out the qualities of the various attempts. How successful were the groups at understanding the Declaration and were they careful to only use Jefferson’s Key Words in doing so?

- The teacher explains that the group will now be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. Again, this is a group discussion-and-negotiation process. After they have decided on a sentence it should be written into their organizers. Again, the teacher should have the groups share out and discuss the clarity and quality of the groups’ attempts.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of the meaning of the Declaration of Indpendence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In this lesson the students will be working individually.

Tell the students that they will be further exploring what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the third selection from the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s words and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working by themselves on their summaries.

- Summary Organizer #3 (PDF)

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first two selections.

- The teacher then "share reads" the third selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the third selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #3. This contains the third selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #3 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday, but they will be working by themselves.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the third paragraph and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. However, because this paragraph is longer (208 words) they can pick ten Key Words.

- Have the students decide which Key Words to select. After they have chosen their words they will write them in the Key Words box of their organizers.

- The teacher explains that, using these Key Words, each student will build a sentence that restates or summarizes what Jefferson was saying. They should write their summary sentences into their organizers.

- The teacher explains that they will be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. This should be added to their organizers.

- The teacher asks for students to share out the summary sentences they have created. This should start a teacher-led discussion that points out the qualities of the various attempts. How successful were the students at understanding what Jefferson was writing about?

Tell the students that they will be further exploring what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the fourth selection from the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s words and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working by themselves on their summaries.

- Summary Organizer #4 (PDF)

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first three selections.

- The teacher then "share reads" the fourth selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the fourth selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #4. This contains the fourth selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #4 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday, but they will be working by themselves.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the fourth paragraph and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. Because this paragraph is the longest (more than 219 words) it will be challenging for them to select only ten Key Words. However, the purpose of this exercise is for the students to get at the most important content of the selection.

- The teacher explains that now they will be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. This should be added to their organizers.

This lesson has two objectives. First, the students will synthesize the work of the last four days and demonstrate that they understand what Jefferson was saying in the Declaration of Independence. Second, the teacher will ask questions of the students that require them to make inferences from the text and also require them to support their conclusions in a short essay with explicit information from the text.

Tell the students that they will be reviewing what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the Declaration of Independence. Second, you will be asking them to write a short argumentative essay about the Declaration; explain that their conclusions must be backed up by evidence taken directly from the text.

- All students are given the abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and then are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The teacher asks the students for their best personal summary of selection one. This is done as a negotiation or discussion. The teacher may write this short sentence on the overhead or similar device. The same procedure is used for selections two, three, and four. When they are finished the class should have a summary, either written or oral, of the Declaration in only a few sentences. This should give the students a way to state what the general purpose or purposes of the document were.

- The teacher can have the students write a short essay now addressing one of the following prompts or do a short lesson on constructing an argumentative essay. If the latter is the case, save the essay writing until the next class period or assign it for homework. Remind the students that any arguments they make must be backed up with words taken directly from the Declaration of Independence. The first prompt is designed to be the easiest.

- What are the key arguments that Thomas Jefferson makes for the colonies’ separation from Great Britain?

- Can the Declaration of Independence be considered a declaration of war? Using evidence from the text argue whether this is or is not true.

- Thomas Jefferson defines what the role of government should and should not be. How does he make these arguments?

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

New York Is Turning 400. We Should Celebrate. But How?

By Russell Shorto

Mr. Shorto is the author of “The Island at the Center of the World” and curator of the exhibit “New York Before New York,” at the New-York Historical Society.

This spring is the 400th anniversary of the founding of New York — or, to be precise, of the Dutch colony that became New York once the English took it over. It’s a noteworthy milestone. That settlement gave rise to a city unencumbered by old ways and powered by pluralism and capitalism: the first modern city, you might say.

Don’t feel bad, though, if you were unaware of the birthday. Organizers of commemorative events have themselves been in a quandary about how to observe it — a quandary that has become familiar in recent years. Yes, New Netherland, the Dutch colony, and New Amsterdam, the city that became New York, created the conditions for New York’s ascent, and helped shape America as a place of tolerance , multiethnicity and free trade. But the Dutch also established slavery in the region and contributed to the removal of Native peoples from their lands. Where in the past we might have highlighted the positives, now the negative elements of that history seem to overshadow them, which may result, paradoxically, in the loss of a valuable opportunity for reflection.

A question that hung in my mind as I curated an exhibit about the founding at the New-York Historical Society continues to vex me, and not just in terms of that event. Are we allowed to celebrate the past anymore? Do we even want to?

Consider that in two years’ time the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and of the founding of our country, will be upon us. Efforts to commemorate the occasion have been slowed, in part, by controversy and confusion because we can’t agree on what our past means. And that’s because we can’t agree on our identity and purpose as a country.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m utterly convinced that the concerted effort of recent years to look deeply into the wrongs of our ancestors is vital. We are going through a national process of reckoning, a societal self-analysis that, if done right, just might result in a more open and honest culture.

But we’ve also become allergic to nuance and complexity. Some seem to feel that championing the achievements of the past means denying the failures. Others fear that to highlight those failures is to undermine the foundation we stand on.

The answer to this conundrum is really quite simple. You do it all. You do your best. In our exhibit, we highlight the contributions of the Dutch — they brought free trade, pluralism and (relative) tolerance, and in so doing they set the template for New York City. At the same time, we give cleareyed attention to the role the Dutch played in the dispossession of the Native people and the introduction of African slavery.

But we don’t stop there. It would be misleading and damaging to leave the impression that the Indigenous and African people in the story had no agency. They were active crafters of that history. Enslaved Black people worked assiduously to win their freedom. Some achieved it and became landowners in what is today Lower Manhattan.

In our exhibit, we feature a petition in which a free Black couple, Emmanuel Pietersz and Dorothea Angola, ask the governing council to guarantee Angola’s adopted son’s freedom. That wasn’t assured in the Dutch system, but they worked the angles, arguing that Angola had raised the boy “with maternal attention and care without having to ask for public assistance.” They won the case.

Members of the Lenape, as well as the powerful Haudenosaunee Confederacy to the north, meanwhile, were businesspeople who had complex relations with the Europeans in New Amsterdam and early New York: trading furs for manufactured goods, at times making war, and at other times negotiating complex peace treaties.

One of the most powerful and fraught items in our exhibit is the nearly 400-year-old letter, on loan from the Dutch National Archives, in which a Dutch official named Pieter Schagen wrote his bosses informing them of the settlement of Manhattan Island. Among other things, he said that their countrymen had bought the island from the Native people for “the value of 60 guilders.” A 19th-century translator would infamously convert that to $24. The Indigenous people probably saw the arrangement as an agreement to share the land. The Dutch went along with that, but eventually reverted to their narrower understanding of real estate transactions and began to push the Lenape aside.

The Schagen letter cuts both ways. It represents the foundation on which New York would be built. Without it, there would be no Broadway, no Wall Street, no Yankee Stadium or Katz’s Deli. It’s also a prime artifact of colonialism.

Such complexity runs through all our history. To add nuance to the exhibit, I invited a group of Lenape chiefs — descendants of the people who very likely took part in that event — to contribute a statement in reaction to the Schagen letter. In the centuries since that time, the Lenape have been systematically abused as America has prospered. The chiefs chose to address their unnamed forebear: “Ancestor, who could have known that a Dutch colonizer’s written words and 60 guilders would bring 400 years of devastation, disease, war, forced removal, oppression, murder, division, suicide and generational trauma for your Lenape people?”

The chiefs took this occasion to assert their people’s presence as part of America’s 21st-century landscape, and to declare that the injustice the letter represents won’t define them: “We will only allow it to highlight the resilience of our spirits, minds and body. We will not allow our stories to be forgotten or erased from history.”

The chiefs’ statement — complex yet packed with feeling — stands in the exhibit beside the historic letter and the brief text I wrote to contextualize it. Viewers can see the actual artifact upon which so much history has been built, read the accompanying texts and react as they see fit.

That is how we can advance the narrative: integrate previously marginalized voices and find our way forward. Some will continue to argue either that history should be put to the purpose of valorizing past events or that its principal aim should be to expose our ancestors’ misdeeds. We need history to support our foundations. But it can only do that with integrity if it exposes the failings.

Maybe the main thing we have to come to terms with in looking back is the simple fact that people of the past were as complex as we are: flawed, scheming, generous, occasionally capable of greatness. Four centuries ago, an interwoven network of them — Europeans, Africans and Native Americans — began something on the island of Manhattan. Appreciating what they did as fully as we can might help us to understand ourselves better. And that would be a cause for celebration.

Russell Shorto ( @RussellShorto ) is the author of “ The Island at the Center of the World ,” director of the New Amsterdam Project at the New-York Historical Society and curator of the exhibit “ New York Before New York .”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Suggested Essay Topics. Previous. In what ways was George III's nationality (German) influential in his actions against the colonists? What influenced moderates to vote for independence? Why would the Declaration of Independence ease the domestic turmoil between Tories and Whigs? In what way did the King of Britain's actions make colonial ...

Essay Topics. 1. In what ways is the Declaration of Independence a timeless document, and in what ways is it a product of a specific time and place? Is it primarily a historical document, or is it relevant to the modern era? 2. How does the Declaration of Independence define a tyrant?

The norms which are presented in the Declaration were connected with all the aspects of the development of the American society in the 18th century. Declaration of Independence - Constitution. Thirteen to 22 abuses describe in detail the use of parliament by the King to destroy the colonies' right to independence.

In At Least 150 Words, Describe The Main Contradiction Inherent In Both The Declaration Of Independence And The Bill Of Rights At The Time They Were Written.

The Declaration of Independence is the foundational document of the United States of America. Written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, it explains why the Thirteen Colonies decided to separate from Great Britain during the American Revolution (1765-1789). It was adopted by the Second Continental Congress on 4 July 1776, the anniversary of which ...

Background Essay: Declaration of Independence. Guiding Question: What were the philosophical bases and practical purposes of the Declaration of Independence? I can explain the major events that led the American colonists to question British rule. I can explain how the concepts of natural rights and self-government influenced the Founders and ...

Text of the Declaration of Independence . Note: The source for this transcription is the first printing of the Declaration of Independence, the broadside produced by John Dunlap on the night of July 4, 1776. Nearly every printed or manuscript edition of the Declaration of Independence has slight differences in punctuation, capitalization, and ...

Declaration of Independence, in U.S. history, document that was approved by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, and that announced the separation of 13 North American British colonies from Great Britain. It explained why the Congress on July 2 "unanimously" by the votes of 12 colonies (with New York abstaining) had resolved that "these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be ...

The U.S. Declaration of Independence, adopted July 4, 1776, was the first formal statement by a nation's people asserting the right to choose their government.

The Declaration of Independence can be looked at two ways: as a legal document separating the colonies from the empire or as a statement of a political philosophy grounded in the natural rights of ...

The Declaration of Independence: A History. Nations come into being in many ways. Military rebellion, civil strife, acts of heroism, acts of treachery, a thousand greater and lesser clashes between defenders of the old order and supporters of the new--all these occurrences and more have marked the emergences of new nations, large and small.

Drafting the Documents. Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia behind a veil of Congressionally imposed secrecy in June 1776 for a country wracked by military and political uncertainties. In anticipation of a vote for independence, the Continental Congress on June 11 appointed Thomas Jefferson, John Adams ...