Annual Review of Ethics Case Studies

What are research ethics cases.

For additional information, please visit Resources for Research Ethics Education

Research Ethics Cases are a tool for discussing scientific integrity. Cases are designed to confront the readers with a specific problem that does not lend itself to easy answers. By providing a focus for discussion, cases help staff involved in research to define or refine their own standards, to appreciate alternative approaches to identifying and resolving ethical problems, and to develop skills for dealing with hard problems on their own.

Research Ethics Cases for Use by the NIH Community

- Theme 23 – Authorship, Collaborations, and Mentoring (2023)

- Theme 22 – Use of Human Biospecimens and Informed Consent (2022)

- Theme 21 – Science Under Pressure (2021)

- Theme 20 – Data, Project and Lab Management, and Communication (2020)

- Theme 19 – Civility, Harassment and Inappropriate Conduct (2019)

- Theme 18 – Implicit and Explicit Biases in the Research Setting (2018)

- Theme 17 – Socially Responsible Science (2017)

- Theme 16 – Research Reproducibility (2016)

- Theme 15 – Authorship and Collaborative Science (2015)

- Theme 14 – Differentiating Between Honest Discourse and Research Misconduct and Introduction to Enhancing Reproducibility (2014)

- Theme 13 – Data Management, Whistleblowers, and Nepotism (2013)

- Theme 12 – Mentoring (2012)

- Theme 11 – Authorship (2011)

- Theme 10 – Science and Social Responsibility, continued (2010)

- Theme 9 – Science and Social Responsibility - Dual Use Research (2009)

- Theme 8 – Borrowing - Is It Plagiarism? (2008)

- Theme 7 – Data Management and Scientific Misconduct (2007)

- Theme 6 – Ethical Ambiguities (2006)

- Theme 5 – Data Management (2005)

- Theme 4 – Collaborative Science (2004)

- Theme 3 – Mentoring (2003)

- Theme 2 – Authorship (2002)

- Theme 1 – Scientific Misconduct (2001)

For Facilitators Leading Case Discussion

For the sake of time and clarity of purpose, it is essential that one individual have responsibility for leading the group discussion. As a minimum, this responsibility should include:

- Reading the case aloud.

- Defining, and re-defining as needed, the questions to be answered.

- Encouraging discussion that is “on topic”.

- Discouraging discussion that is “off topic”.

- Keeping the pace of discussion appropriate to the time available.

- Eliciting contributions from all members of the discussion group.

- Summarizing both majority and minority opinions at the end of the discussion.

How Should Cases be Analyzed?

Many of the skills necessary to analyze case studies can become tools for responding to real world problems. Cases, like the real world, contain uncertainties and ambiguities. Readers are encouraged to identify key issues, make assumptions as needed, and articulate options for resolution. In addition to the specific questions accompanying each case, readers should consider the following questions:

- Who are the affected parties (individuals, institutions, a field, society) in this situation?

- What interest(s) (material, financial, ethical, other) does each party have in the situation? Which interests are in conflict?

- Were the actions taken by each of the affected parties acceptable (ethical, legal, moral, or common sense)? If not, are there circumstances under which those actions would have been acceptable? Who should impose what sanction(s)?

- What other courses of action are open to each of the affected parties? What is the likely outcome of each course of action?

- For each party involved, what course of action would you take, and why?

- What actions could have been taken to avoid the conflict?

Is There a Right Answer?

Acceptable solutions.

Most problems will have several acceptable solutions or answers, but it will not always be the case that a perfect solution can be found. At times, even the best solution will still have some unsatisfactory consequences.

Unacceptable Solutions

While more than one acceptable solution may be possible, not all solutions are acceptable. For example, obvious violations of specific rules and regulations or of generally accepted standards of conduct would typically be unacceptable. However, it is also plausible that blind adherence to accepted rules or standards would sometimes be an unacceptable course of action.

Ethical Decision-Making

It should be noted that ethical decision-making is a process rather than a specific correct answer. In this sense, unethical behavior is defined by a failure to engage in the process of ethical decision-making. It is always unacceptable to have made no reasonable attempt to define a consistent and defensible basis for conduct.

This page was last updated on Friday, July 7, 2023

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Case Study: Protect Your Company or Your Cousin?

- Joseph L. Badaracco

A manager gets inside information that could affect the future of her firm.

After a long week, all Marguerite Espinoza wanted to do was shut down her computer. It was 5:30 on Friday afternoon, and she’d just finished her workday as a customer experience manager at Spring Fire, a manufacturer of outdoor smokeless firepits. But she was supposed to log in to her extended family’s weekly Zoom call, a tradition they’d started at the beginning of the pandemic.

- Joseph L. Badaracco is the John Shad Professor of Business Ethics at Harvard Business School, where he has taught courses on leadership, strategy, corporate responsibility, and management. His books on these subjects include New York Times bestseller Leading Quietly , Defining Moments , and his latest book, Step Back: How to Bring the Art of Reflection into Your Busy Life (HBR Press, 2020).

Partner Center

Advertisement

The Boeing 737 MAX: Lessons for Engineering Ethics

- Original Research/Scholarship

- Published: 10 July 2020

- Volume 26 , pages 2957–2974, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Joseph Herkert 1 ,

- Jason Borenstein 2 &

- Keith Miller 3

106k Accesses

58 Citations

108 Altmetric

11 Mentions

Explore all metrics

The crash of two 737 MAX passenger aircraft in late 2018 and early 2019, and subsequent grounding of the entire fleet of 737 MAX jets, turned a global spotlight on Boeing’s practices and culture. Explanations for the crashes include: design flaws within the MAX’s new flight control software system designed to prevent stalls; internal pressure to keep pace with Boeing’s chief competitor, Airbus; Boeing’s lack of transparency about the new software; and the lack of adequate monitoring of Boeing by the FAA, especially during the certification of the MAX and following the first crash. While these and other factors have been the subject of numerous government reports and investigative journalism articles, little to date has been written on the ethical significance of the accidents, in particular the ethical responsibilities of the engineers at Boeing and the FAA involved in designing and certifying the MAX. Lessons learned from this case include the need to strengthen the voice of engineers within large organizations. There is also the need for greater involvement of professional engineering societies in ethics-related activities and for broader focus on moral courage in engineering ethics education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Repentance as Rebuke: Betrayal and Moral Injury in Safety Engineering

Airworthiness and Safety in Air Operations in Ecuadorian Public Institutions

Safety in Numbers? (Lessons Learned From Aviation Safety Assessment Techniques)

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In October 2018 and March 2019, Boeing 737 MAX passenger jets crashed minutes after takeoff; these two accidents claimed nearly 350 lives. After the second incident, all 737 MAX planes were grounded worldwide. The 737 MAX was an updated version of the 737 workhorse that first began flying in the 1960s. The crashes were precipitated by a failure of an Angle of Attack (AOA) sensor and the subsequent activation of new flight control software, the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS). The MCAS software was intended to compensate for changes in the size and placement of the engines on the MAX as compared to prior versions of the 737. The existence of the software, designed to prevent a stall due to the reconfiguration of the engines, was not disclosed to pilots until after the first crash. Even after that tragic incident, pilots were not required to undergo simulation training on the 737 MAX.

In this paper, we examine several aspects of the case, including technical and other factors that led up to the crashes, especially Boeing’s design choices and organizational tensions internal to the company, and between Boeing and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). While the case is ongoing and at this writing, the 737 MAX has yet to be recertified for flight, our analysis is based on numerous government reports and detailed news accounts currently available. We conclude with a discussion of specific lessons for engineers and engineering educators regarding engineering ethics.

Overview of 737 MAX History and Crashes

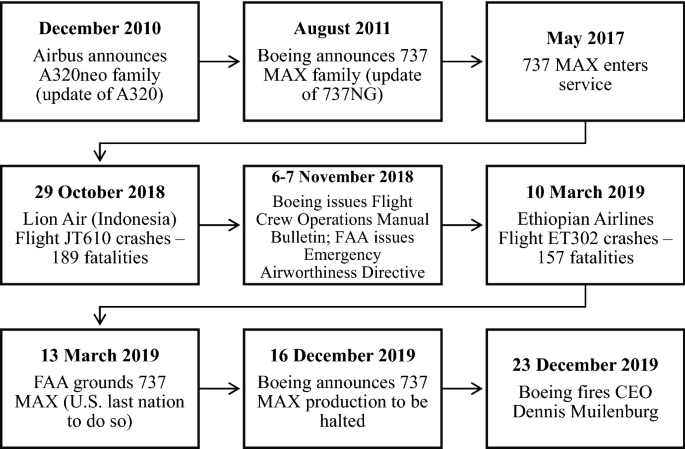

In December 2010, Boeing’s primary competitor Airbus announced the A320neo family of jetliners, an update of their successful A320 narrow-body aircraft. The A320neo featured larger, more fuel-efficient engines. Boeing had been planning to introduce a totally new aircraft to replace its successful, but dated, 737 line of jets; yet to remain competitive with Airbus, Boeing instead announced in August 2011 the 737 MAX family, an update of the 737NG with similar engine upgrades to the A320neo and other improvements (Gelles et al. 2019 ). The 737 MAX, which entered service in May 2017, became Boeing’s fastest-selling airliner of all time with 5000 orders from over 100 airlines worldwide (Boeing n.d. a) (See Fig. 1 for timeline of 737 MAX key events).

737 MAX timeline showing key events from 2010 to 2019

The 737 MAX had been in operation for over a year when on October 29, 2018, Lion Air flight JT610 crashed into the Java Sea 13 minutes after takeoff from Jakarta, Indonesia; all 189 passengers and crew on board died. Monitoring from the flight data recorder recovered from the wreckage indicated that MCAS, the software specifically designed for the MAX, forced the nose of the aircraft down 26 times in 10 minutes (Gates 2018 ). In October 2019, the Final Report of Indonesia’s Lion Air Accident Investigation was issued. The Report placed some of the blame on the pilots and maintenance crews but concluded that Boeing and the FAA were primarily responsible for the crash (Republic of Indonesia 2019 ).

MCAS was not identified in the original documentation/training for 737 MAX pilots (Glanz et al. 2019 ). But after the Lion Air crash, Boeing ( 2018 ) issued a Flight Crew Operations Manual Bulletin on November 6, 2018 containing procedures for responding to flight control problems due to possible erroneous AOA inputs. The next day the FAA ( 2018a ) issued an Emergency Airworthiness Directive on the same subject; however, the FAA did not ground the 737 MAX at that time. According to published reports, these notices were the first time that airline pilots learned of the existence of MCAS (e.g., Bushey 2019 ).

On March 20, 2019, about four months after the Lion Air crash, Ethiopian Airlines Flight ET302 crashed 6 minutes after takeoff in a field 39 miles from Addis Ababa Airport. The accident caused the deaths of all 157 passengers and crew. The Preliminary Report of the Ethiopian Airlines Accident Investigation (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia 2019 ), issued in April 2019, indicated that the pilots followed the checklist from the Boeing Flight Crew Operations Manual Bulletin posted after the Lion Air crash but could not control the plane (Ahmed et al. 2019 ). This was followed by an Interim Report (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia 2020 ) issued in March 2020 that exonerated the pilots and airline, and placed blame for the accident on design flaws in the MAX (Marks and Dahir 2020 ). Following the second crash, the 737 MAX was grounded worldwide with the U.S., through the FAA, being the last country to act on March 13, 2019 (Kaplan et al. 2019 ).

Design Choices that Led to the Crashes

As noted above, with its belief that it must keep up with its main competitor, Airbus, Boeing elected to modify the latest generation of the 737 family, the 737NG, rather than design an entirely new aircraft. Yet this raised a significant engineering challenge for Boeing. Mounting larger, more fuel-efficient engines, similar to those employed on the A320neo, on the existing 737 airframe posed a serious design problem, because the 737 family was built closer to the ground than the Airbus A320. In order to provide appropriate ground clearance, the larger engines had to be mounted higher and farther forward on the wings than previous models of the 737 (see Fig. 2 ). This significantly changed the aerodynamics of the aircraft and created the possibility of a nose-up stall under certain flight conditions (Travis 2019 ; Glanz et al. 2019 ).

(Image source: https://www.norebbo.com )

Boeing 737 MAX (left) compared to Boeing 737NG (right) showing larger 737 MAX engines mounted higher and more forward on the wing.

Boeing’s attempt to solve this problem involved incorporating MCAS as a software fix for the potential stall condition. The 737 was designed with two AOA sensors, one on each side of the aircraft. Yet Boeing decided that the 737 MAX would only use input from one of the plane’s two AOA sensors. If the single AOA sensor was triggered, MCAS would detect a dangerous nose-up condition and send a signal to the horizontal stabilizer located in the tail. Movement of the stabilizer would then force the plane’s tail up and the nose down (Travis 2019 ). In both the Lion Air and Ethiopian Air crashes, the AOA sensor malfunctioned, repeatedly activating MCAS (Gates 2018 ; Ahmed et al. 2019 ). Since the two crashes, Boeing has made adjustments to the MCAS, including that the system will rely on input from the two AOA sensors instead of just one. But still more problems with MCAS have been uncovered. For example, an indicator light that would alert pilots if the jet’s two AOA sensors disagreed, thought by Boeing to be standard on all MAX aircraft, would only operate as part of an optional equipment package that neither airline involved in the crashes purchased (Gelles and Kitroeff 2019a ).

Similar to its responses to previous accidents, Boeing has been reluctant to admit to a design flaw in its aircraft, instead blaming pilot error (Hall and Goelz 2019 ). In the 737 MAX case, the company pointed to the pilots’ alleged inability to control the planes under stall conditions (Economy 2019 ). Following the Ethiopian Airlines crash, Boeing acknowledged for the first time that MCAS played a primary role in the crashes, while continuing to highlight that other factors, such as pilot error, were also involved (Hall and Goelz 2019 ). For example, on April 29, 2019, more than a month after the second crash, then Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg defended MCAS by stating:

We've confirmed that [the MCAS system] was designed per our standards, certified per our standards, and we're confident in that process. So, it operated according to those design and certification standards. So, we haven't seen a technical slip or gap in terms of the fundamental design and certification of the approach. (Economy 2019 )

The view that MCAS was not primarily at fault was supported within an article written by noted journalist and pilot William Langewiesche ( 2019 ). While not denying Boeing made serious mistakes, he placed ultimate blame on the use of inexperienced pilots by the two airlines involved in the crashes. Langewiesche suggested that the accidents resulted from the cost-cutting practices of the airlines and the lax regulatory environments in which they operated. He argued that more experienced pilots, despite their lack of information on MCAS, should have been able to take corrective action to control the planes using customary stall prevention procedures. Langewiesche ( 2019 ) concludes in his article that:

What we had in the two downed airplanes was a textbook failure of airmanship. In broad daylight, these pilots couldn’t decipher a variant of a simple runaway trim, and they ended up flying too fast at low altitude, neglecting to throttle back and leading their passengers over an aerodynamic edge into oblivion. They were the deciding factor here — not the MCAS, not the Max.

Others have taken a more critical view of MCAS, Boeing, and the FAA. These critics prominently include Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, who famously crash-landed an A320 in the Hudson River after bird strikes had knocked out both of the plane’s engines. Sullenberger responded directly to Langewiesche in a letter to the Editor:

… Langewiesche draws the conclusion that the pilots are primarily to blame for the fatal crashes of Lion Air 610 and Ethiopian 302. In resurrecting this age-old aviation canard, Langewiesche minimizes the fatal design flaws and certification failures that precipitated those tragedies, and still pose a threat to the flying public. I have long stated, as he does note, that pilots must be capable of absolute mastery of the aircraft and the situation at all times, a concept pilots call airmanship. Inadequate pilot training and insufficient pilot experience are problems worldwide, but they do not excuse the fatally flawed design of the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) that was a death trap.... (Sullenberger 2019 )

Noting that he is one of the few pilots to have encountered both accident sequences in a 737 MAX simulator, Sullenberger continued:

These emergencies did not present as a classic runaway stabilizer problem, but initially as ambiguous unreliable airspeed and altitude situations, masking MCAS. The MCAS design should never have been approved, not by Boeing, and not by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)…. (Sullenberger 2019 )

In June 2019, Sullenberger noted in Congressional Testimony that “These crashes are demonstrable evidence that our current system of aircraft design and certification has failed us. These accidents should never have happened” (Benning and DiFurio 2019 ).

Others have agreed with Sullenberger’s assessment. Software developer and pilot Gregory Travis ( 2019 ) argues that Boeing’s design for the 737 MAX violated industry norms and that the company unwisely used software to compensate for inadequacies in the hardware design. Travis also contends that the existence of MCAS was not disclosed to pilots in order to preserve the fiction that the 737 MAX was just an update of earlier 737 models, which served as a way to circumvent the more stringent FAA certification requirements for a new airplane. Reports from government agencies seem to support this assessment, emphasizing the chaotic cockpit conditions created by MCAS and poor certification practices. The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) ( 2019 ) Safety Recommendations to the FAA in September 2019 indicated that Boeing underestimated the effect MCAS malfunction would have on the cockpit environment (Kitroeff 2019 , a , b ). The FAA Joint Authorities Technical Review ( 2019 ), which included international participation, issued its Final Report in October 2019. The Report faulted Boeing and FAA in MCAS certification (Koenig 2019 ).

Despite Boeing’s attempts to downplay the role of MCAS, it began to work on a fix for the system shortly after the Lion Air crash (Gates 2019 ). MCAS operation will now be based on inputs from both AOA sensors, instead of just one sensor, with a cockpit indicator light when the sensors disagree. In addition, MCAS will only be activated once for an AOA warning rather than multiple times. What follows is that the system would only seek to prevent a stall once per AOA warning. Also, MCAS’s power will be limited in terms of how much it can move the stabilizer and manual override by the pilot will always be possible (Bellamy 2019 ; Boeing n.d. b; Gates 2019 ). For over a year after the Lion Air crash, Boeing held that pilot simulator training would not be required for the redesigned MCAS system. In January 2020, Boeing relented and recommended that pilot simulator training be required when the 737 MAX returns to service (Pasztor et al. 2020 ).

Boeing and the FAA

There is mounting evidence that Boeing, and the FAA as well, had warnings about the inadequacy of MCAS’s design, and about the lack of communication to pilots about its existence and functioning. In 2015, for example, an unnamed Boeing engineer raised in an email the issue of relying on a single AOA sensor (Bellamy 2019 ). In 2016, Mark Forkner, Boeing’s Chief Technical Pilot, in an email to a colleague flagged the erratic behavior of MCAS in a flight simulator noting: “It’s running rampant” (Gelles and Kitroeff 2019c ). Forkner subsequently came under federal investigation regarding whether he misled the FAA regarding MCAS (Kitroeff and Schmidt 2020 ).

In December 2018, following the Lion Air Crash, the FAA ( 2018b ) conducted a Risk Assessment that estimated that fifteen more 737 MAX crashes would occur in the expected fleet life of 45 years if the flight control issues were not addressed; this Risk Assessment was not publicly disclosed until Congressional hearings a year later in December 2019 (Arnold 2019 ). After the two crashes, a senior Boeing engineer, Curtis Ewbank, filed an internal ethics complaint in 2019 about management squelching of a system that might have uncovered errors in the AOA sensors. Ewbank has since publicly stated that “I was willing to stand up for safety and quality… Boeing management was more concerned with cost and schedule than safety or quality” (Kitroeff et al. 2019b ).

One factor in Boeing’s apparent reluctance to heed such warnings may be attributed to the seeming transformation of the company’s engineering and safety culture over time to a finance orientation beginning with Boeing’s merger with McDonnell–Douglas in 1997 (Tkacik 2019 ; Useem 2019 ). Critical changes after the merger included replacing many in Boeing’s top management, historically engineers, with business executives from McDonnell–Douglas and moving the corporate headquarters to Chicago, while leaving the engineering staff in Seattle (Useem 2019 ). According to Tkacik ( 2019 ), the new management even went so far as “maligning and marginalizing engineers as a class”.

Financial drivers thus began to place an inordinate amount of strain on Boeing employees, including engineers. During the development of the 737 MAX, significant production pressure to keep pace with the Airbus 320neo was ever-present. For example, Boeing management allegedly rejected any design changes that would prolong certification or require additional pilot training for the MAX (Gelles et al. 2019 ). As Adam Dickson, a former Boeing engineer, explained in a television documentary (BBC Panorama 2019 ): “There was a lot of interest and pressure on the certification and analysis engineers in particular, to look at any changes to the Max as minor changes”.

Production pressures were exacerbated by the “cozy relationship” between Boeing and the FAA (Kitroeff et al. 2019a ; see also Gelles and Kaplan 2019 ; Hall and Goelz 2019 ). Beginning in 2005, the FAA increased its reliance on manufacturers to certify their own planes. Self-certification became standard practice throughout the U.S. airline industry. By 2018, Boeing was certifying 96% of its own work (Kitroeff et al. 2019a ).

The serious drawbacks to self-certification became acutely apparent in this case. Of particular concern, the safety analysis for MCAS delegated to Boeing by the FAA was flawed in at least three respects: (1) the analysis underestimated the power of MCAS to move the plane’s horizontal tail and thus how difficult it would be for pilots to maintain control of the aircraft; (2) it did not account for the system deploying multiple times; and (3) it underestimated the risk level if MCAS failed, thus permitting a design feature—the single AOA sensor input to MCAS—that did not have built-in redundancy (Gates 2019 ). Related to these concerns, the ability of MCAS to move the horizontal tail was increased without properly updating the safety analysis or notifying the FAA about the change (Gates 2019 ). In addition, the FAA did not require pilot training for MCAS or simulator training for the 737 MAX (Gelles and Kaplan 2019 ). Since the MAX grounding, the FAA has been become more independent during its assessments and certifications—for example, they will not use Boeing personnel when certifying approvals of new 737 MAX planes (Josephs 2019 ).

The role of the FAA has also been subject to political scrutiny. The report of a study of the FAA certification process commissioned by Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao (DOT 2020 ), released January 16, 2020, concluded that the FAA certification process was “appropriate and effective,” and that certification of the MAX as a new airplane would not have made a difference in the plane’s safety. At the same time, the report recommended a number of measures to strengthen the process and augment FAA’s staff (Pasztor and Cameron 2020 ). In contrast, a report of preliminary investigative findings by the Democratic staff of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure (House TI 2020 ), issued in March 2020, characterized FAA’s certification of the MAX as “grossly insufficient” and criticized Boeing’s design flaws and lack of transparency with the FAA, airlines, and pilots (Duncan and Laris 2020 ).

Boeing has incurred significant economic losses from the crashes and subsequent grounding of the MAX. In December 2019, Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg was fired and the corporation announced that 737 MAX production would be suspended in January 2020 (Rich 2019 ) (see Fig. 1 ). Boeing is facing numerous lawsuits and possible criminal investigations. Boeing estimates that its economic losses for the 737 MAX will exceed $18 billion (Gelles 2020 ). In addition to the need to fix MCAS, other issues have arisen in recertification of the aircraft, including wiring for controls of the tail stabilizer, possible weaknesses in the engine rotors, and vulnerabilities in lightning protection for the engines (Kitroeff and Gelles 2020 ). The FAA had planned to flight test the 737 MAX early in 2020, and it was supposed to return to service in summer 2020 (Gelles and Kitroeff 2020 ). Given the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and other factors, it is difficult to predict when MAX flights might resume. In addition, uncertainty of passenger demand has resulted in some airlines delaying or cancelling orders for the MAX (Bogaisky 2020 ). Even after obtaining flight approval, public resistance to flying in the 737 MAX will probably be considerable (Gelles 2019 ).

Lessons for Engineering Ethics

The 737 MAX case is still unfolding and will continue to do so for some time. Yet important lessons can already be learned (or relearned) from the case. Some of those lessons are straightforward, and others are more subtle. A key and clear lesson is that engineers may need reminders about prioritizing the public good, and more specifically, the public’s safety. A more subtle lesson pertains to the ways in which the problem of many hands may or may not apply here. Other lessons involve the need for corporations, engineering societies, and engineering educators to rise to the challenge of nurturing and supporting ethical behavior on the part of engineers, especially in light of the difficulties revealed in this case.

All contemporary codes of ethics promulgated by major engineering societies state that an engineer’s paramount responsibility is to protect the “safety, health, and welfare” of the public. The American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Code of Ethics indicates that engineers must “[H]old paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public in the performance of their duties” (AIAA 2013 ). The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Code of Ethics goes further, pledging its members: “…to hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public, to strive to comply with ethical design and sustainable development practices, and to disclose promptly factors that might endanger the public or the environment” (IEEE 2017 ). The IEEE Computer Society (CS) cooperated with the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) in developing a Software Engineering Code of Ethics ( 1997 ) which holds that software engineers shall: “Approve software only if they have a well-founded belief that it is safe, meets specifications, passes appropriate tests, and does not diminish quality of life, diminish privacy or harm the environment….” According to Gotterbarn and Miller ( 2009 ), the latter code is a useful guide when examining cases involving software design and underscores the fact that during design, as in all engineering practice, the well-being of the public should be the overriding concern. While engineering codes of ethics are plentiful in number, they differ in their source of moral authority (i.e., organizational codes vs. professional codes), are often unenforceable through the law, and formally apply to different groups of engineers (e.g., based on discipline or organizational membership). However, the codes are generally recognized as a statement of the values inherent to engineering and its ethical commitments (Davis 2015 ).

An engineer’s ethical responsibility does not preclude consideration of factors such as cost and schedule (Pinkus et al. 1997 ). Engineers always have to grapple with constraints, including time and resource limitations. The engineers working at Boeing did have legitimate concerns about their company losing contracts to its competitor Airbus. But being an engineer means that public safety and welfare must be the highest priority (Davis 1991 ). The aforementioned software and other design errors in the development of the 737 MAX, which resulted in hundreds of deaths, would thus seem to be clear violations of engineering codes of ethics. In addition to pointing to engineering codes, Peterson ( 2019 ) argues that Boeing engineers and managers violated widely accepted ethical norms such as informed consent and the precautionary principle.

From an engineering perspective, the central ethical issue in the MAX case arguably circulates around the decision to use software (i.e., MCAS) to “mask” a questionable hardware design—the repositioning of the engines that disrupted the aerodynamics of the airframe (Travis 2019 ). As Johnston and Harris ( 2019 ) argue: “To meet the design goals and avoid an expensive hardware change, Boeing created the MCAS as a software Band-Aid.” Though a reliance on software fixes often happens in this manner, it places a high burden of safety on such fixes that they may not be able to handle, as is illustrated by the case of the Therac-25 radiation therapy machine. In the Therac-25 case, hardware safety interlocks employed in earlier models of the machine were replaced by software safety controls. In addition, information about how the software might malfunction was lacking from the user manual for the Therac machine. Thus, when certain types of errors appeared on its interface, the machine’s operators did not know how to respond. Software flaws, among other factors, contributed to six patients being given massive radiation overdoses, resulting in deaths and serious injuries (Leveson and Turner 1993 ). A more recent case involves problems with the embedded software guiding the electronic throttle in Toyota vehicles. In 2013, “…a jury found Toyota responsible for two unintended acceleration deaths, with expert witnesses citing bugs in the software and throttle fail safe defects” (Cummings and Britton 2020 ).

Boeing’s use of MCAS to mask the significant change in hardware configuration of the MAX was compounded by not providing redundancy for components prone to failure (i.e., the AOA sensors) (Campbell 2019 ), and by failing to notify pilots about the new software. In such cases, it is especially crucial that pilots receive clear documentation and relevant training so that they know how to manage the hand-off with an automated system properly (Johnston and Harris 2019 ). Part of the necessity for such training is related to trust calibration (Borenstein et al. 2020 ; Borenstein et al. 2018 ), a factor that has contributed to previous airplane accidents (e.g., Carr 2014 ). For example, if pilots do not place enough trust in an automated system, they may add risk by intervening in system operation. Conversely, if pilots trust an automated system too much, they may lack sufficient time to act once they identify a problem. This is further complicated in the MAX case because pilots were not fully aware, if at all, of MCAS’s existence and how the system functioned.

In addition to engineering decision-making that failed to prioritize public safety, questionable management decisions were also made at both Boeing and the FAA. As noted earlier, Boeing managerial leadership ignored numerous warning signs that the 737 MAX was not safe. Also, FAA’s shift to greater reliance on self-regulation by Boeing was ill-advised; that lesson appears to have been learned at the expense of hundreds of lives (Duncan and Aratani 2019 ).

The Problem of Many Hands Revisited

Actions, or inaction, by large, complex organizations, in this case corporate and government entities, suggest that the “problem of many hands” may be relevant to the 737 MAX case. At a high level of abstraction, the problem of many hands involves the idea that accountability is difficult to assign in the face of collective action, especially in a computerized society (Thompson 1980 ; Nissenbaum 1994 ). According to Nissenbaum ( 1996 , 29), “Where a mishap is the work of ‘many hands,’ it may not be obvious who is to blame because frequently its most salient and immediate causal antecedents do not converge with its locus of decision-making. The conditions for blame, therefore, are not satisfied in a way normally satisfied when a single individual is held blameworthy for a harm”.

However, there is an alternative understanding of the problem of many hands. In this version of the problem, the lack of accountability is not merely because multiple people and multiple decisions figure into a final outcome. Instead, in order to “qualify” as the problem of many hands, the component decisions should be benign, or at least far less harmful, if examined in isolation; only when the individual decisions are collectively combined do we see the most harmful result. In this understanding, the individual decision-makers should not have the same moral culpability as they would if they made all the decisions by themselves (Noorman 2020 ).

Both of these understandings of the problem of many hands could shed light on the 737 MAX case. Yet we focus on the first version of the problem. We admit the possibility that some of the isolated decisions about the 737 MAX may have been made in part because of ignorance of a broader picture. While we do not stake a claim on whether this is what actually happened in the MAX case, we acknowledge that it may be true in some circumstances. However, we think the more important point is that some of the 737 MAX decisions were so clearly misguided that a competent engineer should have seen the implications, even if the engineer was not aware of all of the broader context. The problem then is to identify responsibility for the questionable decisions in a way that discourages bad judgments in the future, a task made more challenging by the complexities of the decision-making. Legal proceedings about this case are likely to explore those complexities in detail and are outside the scope of this article. But such complexities must be examined carefully so as not to act as an insulator to accountability.

When many individuals are involved in the design of a computing device, for example, and a serious failure occurs, each person might try to absolve themselves of responsibility by indicating that “too many people” and “too many decisions” were involved for any individual person to know that the problem was going to happen. This is a common, and often dubious, excuse in the attempt to abdicate responsibility for a harm. While it can have different levels of magnitude and severity, the problem of many hands often arises in large scale ethical failures in engineering such as in the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (Thompson 2014 ).

Possible examples in the 737 MAX case of the difficulty of assigning moral responsibility due to the problem of many hands include:

The decision to reposition the engines;

The decision to mask the jet’s subsequent dynamic instability with MCAS;

The decision to rely on only one AOA sensor in designing MCAS; and

The decision to not inform nor properly train pilots about the MCAS system.

While overall responsibility for each of these decisions may be difficult to allocate precisely, at least points 1–3 above arguably reflect fundamental errors in engineering judgement (Travis 2019 ). Boeing engineers and FAA engineers either participated in or were aware of these decisions (Kitroeff and Gelles 2019 ) and may have had opportunities to reconsider or redirect such decisions. As Davis has noted ( 2012 ), responsible engineering professionals make it their business to address problems even when they did not cause the problem, or, we would argue, solely cause it. As noted earlier, reports indicate that at least one Boeing engineer expressed reservations about the design of MCAS (Bellamy 2019 ). Since the two crashes, one Boeing engineer, Curtis Ewbank, filed an internal ethics complaint (Kitroeff et al. 2019b ) and several current and former Boeing engineers and other employees have gone public with various concerns about the 737 MAX (Pasztor 2019 ). And yet, as is often the case, the flawed design went forward with tragic results.

Enabling Ethical Engineers

The MAX case is eerily reminiscent of other well-known engineering ethics case studies such as the Ford Pinto (Birsch and Fielder 1994 ), Space Shuttle Challenger (Werhane 1991 ), and GM ignition switch (Jennings and Trautman 2016 ). In the Pinto case, Ford engineers were aware of the unsafe placement of the fuel tank well before the car was released to the public and signed off on the design even though crash tests showed the tank was vulnerable to rupture during low-speed rear-end collisions (Baura 2006 ). In the case of the GM ignition switch, engineers knew for at least four years about the faulty design, a flaw that resulted in at least a dozen fatal accidents (Stephan 2016 ). In the case of the well-documented Challenger accident, engineer Roger Boisjoly warned his supervisors at Morton Thiokol of potentially catastrophic flaws in the shuttle’s solid rocket boosters a full six months before the accident. He, along with other engineers, unsuccessfully argued on the eve of launch for a delay due to the effect that freezing temperatures could have on the boosters’ O-ring seals. Boisjoly was also one of a handful of engineers to describe these warnings to the Presidential commission investigating the accident (Boisjoly et al. 1989 ).

Returning to the 737 MAX case, could Ewbank or others with concerns about the safety of the airplane have done more than filing ethics complaints or offering public testimony only after the Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines crashes? One might argue that requiring professional registration by all engineers in the U.S. would result in more ethical conduct (for example, by giving state licensing boards greater oversight authority). Yet the well-entrenched “industry exemption” from registration for most engineers working in large corporations has undermined such calls (Kline 2001 ).

It could empower engineers with safety concerns if Boeing and other corporations would strengthen internal ethics processes, including sincere and meaningful responsiveness to anonymous complaint channels. Schwartz ( 2013 ) outlines three core components of an ethical corporate culture, including strong core ethical values, a formal ethics program (including an ethics hotline), and capable ethical leadership. Schwartz points to Siemens’ creation of an ethics and compliance department following a bribery scandal as an example of a good solution. Boeing has had a compliance department for quite some time (Schnebel and Bienert 2004 ) and has taken efforts in the past to evaluate its effectiveness (Boeing 2003 ). Yet it is clear that more robust measures are needed in response to ethics concerns and complaints. Since the MAX crashes, Boeing’s Board has implemented a number of changes including establishing a corporate safety group and revising internal reporting procedures so that lead engineers primarily report to the chief engineer rather than business managers (Gelles and Kitroeff 2019b , Boeing n.d. c). Whether these measures will be enough to restore Boeing’s former engineering-centered focus remains to be seen.

Professional engineering societies could play a stronger role in communicating and enforcing codes of ethics, in supporting ethical behavior of engineers, and by providing more educational opportunities for learning about ethics and about the ethical responsibilities of engineers. Some societies, including ACM and IEEE, have become increasingly engaged in ethics-related activities. Initially ethics engagement by the societies consisted primarily of a focus on macroethical issues such as sustainable development (Herkert 2004 ). Recently, however, the societies have also turned to a greater focus on microethical issues (the behavior of individuals). The 2017 revision to the IEEE Code of Ethics, for example, highlights the importance of “ethical design” (Adamson and Herkert 2020 ). This parallels IEEE activities in the area of design of autonomous and intelligent systems (e.g., IEEE 2018 ). A promising outcome of this emphasis is a move toward implementing “ethical design” frameworks (Peters et al. 2020 ).

In terms of engineering education, educators need to place a greater emphasis on fostering moral courage, that is the courage to act on one’s moral convictions including adherence to codes of ethics. This is of particular significance in large organizations such as Boeing and the FAA where the agency of engineers may be limited by factors such as organizational culture (Watts and Buckley 2017 ). In a study of twenty-six ethics interventions in engineering programs, Hess and Fore ( 2018 ) found that only twenty-seven percent had a learning goal of development of “ethical courage, confidence or commitment”. This goal could be operationalized in a number of ways, for example through a focus on virtue ethics (Harris 2008 ) or professional identity (Hashemian and Loui 2010 ). This need should not only be addressed within the engineering curriculum but during lifelong learning initiatives and other professional development opportunities as well (Miller 2019 ).

The circumstances surrounding the 737 MAX airplane could certainly serve as an informative case study for ethics or technical courses. The case can shed light on important lessons for engineers including the complex interactions, and sometimes tensions, between engineering and managerial considerations. The case also tangibly displays that what seems to be relatively small-scale, and likely well-intended, decisions by individual engineers can combine collectively to result in large-scale tragedy. No individual person wanted to do harm, but it happened nonetheless. Thus, the case can serve a reminder to current and future generations of engineers that public safety must be the first and foremost priority. A particularly useful pedagogical method for considering this case is to assign students to the roles of engineers, managers, and regulators, as well as the flying public, airline personnel, and representatives of engineering societies (Herkert 1997 ). In addition to illuminating the perspectives and responsibilities of each stakeholder group, role-playing can also shed light on the “macroethical” issues raised by the case (Martin et al. 2019 ) such as airline safety standards and the proper role for engineers and engineering societies in the regulation of the industry.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The case of the Boeing 737 MAX provides valuable lessons for engineers and engineering educators concerning the ethical responsibilities of the profession. Safety is not cheap, but careless engineering design in the name of minimizing costs and adhering to a delivery schedule is a symptom of ethical blight. Using almost any standard ethical analysis or framework, Boeing’s actions regarding the safety of the 737 MAX, particularly decisions regarding MCAS, fall short.

Boeing failed in its obligations to protect the public. At a minimum, the company had an obligation to inform airlines and pilots of significant design changes, especially the role of MCAS in compensating for repositioning of engines in the MAX from prior versions of the 737. Clearly, it was a “significant” change because it had a direct, and unfortunately tragic, impact on the public’s safety. The Boeing and FAA interaction underscores the fact that conflicts of interest are a serious concern in regulatory actions within the airline industry.

Internal and external organizational factors may have interfered with Boeing and FAA engineers’ fulfillment of their professional ethical responsibilities; this is an all too common problem that merits serious attention from industry leaders, regulators, professional societies, and educators. The lessons to be learned in this case are not new. After large scale tragedies involving engineering decision-making, calls for change often emerge. But such lessons apparently must be retaught and relearned by each generation of engineers.

ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Task Force. (1997). Software Engineering Code of Ethics and Professional Practice, https://ethics.acm.org/code-of-ethics/software-engineering-code/ .

Adamson, G., & Herkert, J. (2020). Addressing intelligent systems and ethical design in the IEEE Code of Ethics. In Codes of ethics and ethical guidelines: Emerging technologies, changing fields . New York: Springer ( in press ).

Ahmed, H., Glanz, J., & Beech, H. (2019). Ethiopian airlines pilots followed Boeing’s safety procedures before crash, Report Shows. The New York Times, April 4, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/04/world/asia/ethiopia-crash-boeing.html .

AIAA. (2013). Code of Ethics, https://www.aiaa.org/about/Governance/Code-of-Ethics .

Arnold, K. (2019). FAA report predicted there could be 15 more 737 MAX crashes. The Dallas Morning News, December 11, https://www.dallasnews.com/business/airlines/2019/12/11/faa-chief-says-boeings-737-max-wont-be-approved-in-2019/

Baura, G. (2006). Engineering ethics: an industrial perspective . Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Google Scholar

BBC News. (2019). Work on production line of Boeing 737 MAX ‘Not Adequately Funded’. July 29, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-49142761 .

Bellamy, W. (2019). Boeing CEO outlines 737 MAX MCAS software fix in congressional hearings. Aviation Today, November 2, https://www.aviationtoday.com/2019/11/02/boeing-ceo-outlines-mcas-updates-congressional-hearings/ .

Benning, T., & DiFurio, D. (2019). American Airlines Pilots Union boss prods lawmakers to solve 'Crisis of Trust' over Boeing 737 MAX. The Dallas Morning News, June 19, https://www.dallasnews.com/business/airlines/2019/06/19/american-airlines-pilots-union-boss-prods-lawmakers-to-solve-crisis-of-trust-over-boeing-737-max/ .

Birsch, D., & Fielder, J. (Eds.). (1994). The ford pinto case: A study in applied ethics, business, and technology . New York: The State University of New York Press.

Boeing. (2003). Boeing Releases Independent Reviews of Company Ethics Program. December 18, https://boeing.mediaroom.com/2003-12-18-Boeing-Releases-Independent-Reviews-of-Company-Ethics-Program .

Boeing. (2018). Flight crew operations manual bulletin for the Boeing company. November 6, https://www.avioesemusicas.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/TBC-19-Uncommanded-Nose-Down-Stab-Trim-Due-to-AOA.pdf .

Boeing. (n.d. a). About the Boeing 737 MAX. https://www.boeing.com/commercial/737max/ .

Boeing. (n.d. b). 737 MAX Updates. https://www.boeing.com/737-max-updates/ .

Boeing. (n.d. c). Initial actions: sharpening our focus on safety. https://www.boeing.com/737-max-updates/resources/ .

Bogaisky, J. (2020). Boeing stock plunges as coronavirus imperils quick ramp up in 737 MAX deliveries. Forbes, March 11, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeremybogaisky/2020/03/11/boeing-coronavirus-737-max/#1b9eb8955b5a .

Boisjoly, R. P., Curtis, E. F., & Mellican, E. (1989). Roger Boisjoly and the challenger disaster: The ethical dimensions. J Bus Ethics, 8 (4), 217–230.

Article Google Scholar

Borenstein, J., Mahajan, H. P., Wagner, A. R., & Howard, A. (2020). Trust and pediatric exoskeletons: A comparative study of clinician and parental perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society , 1 (2), 83–88.

Borenstein, J., Wagner, A. R., & Howard, A. (2018). Overtrust of pediatric health-care robots: A preliminary survey of parent perspectives. IEEE Robot Autom Mag, 25 (1), 46–54.

Bushey, C. (2019). The Tough Crowd Boeing Needs to Convince. Crain’s Chicago Business, October 25, https://www.chicagobusiness.com/manufacturing/tough-crowd-boeing-needs-convince .

Campbell, D. (2019). The many human errors that brought down the Boeing 737 MAX. The Verge, May 2, https://www.theverge.com/2019/5/2/18518176/boeing-737-max-crash-problems-human-error-mcas-faa .

Carr, N. (2014). The glass cage: Automation and us . Norton.

Cummings, M. L., & Britton, D. (2020). Regulating safety-critical autonomous systems: past, present, and future perspectives. In Living with robots (pp. 119–140). Academic Press, New York.

Davis, M. (1991). Thinking like an engineer: The place of a code of ethics in the practice of a profession. Philos Publ Affairs, 20 (2), 150–167.

Davis, M. (2012). “Ain’t no one here but us social forces”: Constructing the professional responsibility of engineers. Sci Eng Ethics, 18 (1), 13–34.

Davis, M. (2015). Engineering as profession: Some methodological problems in its study. In Engineering identities, epistemologies and values (pp. 65–79). Springer, New York.

Department of Transportation (DOT). (2020). Official report of the special committee to review the Federal Aviation Administration’s Aircraft Certification Process, January 16. https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/2020-01/scc-final-report.pdf .

Duncan, I., & Aratani, L. (2019). FAA flexes its authority in final stages of Boeing 737 MAX safety review. The Washington Post, November 27, https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2019/11/27/faa-flexes-its-authority-final-stages-boeing-max-safety-review/ .

Duncan, I., & Laris, M. (2020). House report on 737 Max crashes faults Boeing’s ‘culture of concealment’ and labels FAA ‘grossly insufficient’. The Washington Post, March 6, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/trafficandcommuting/house-report-on-737-max-crashes-faults-boeings-culture-of-concealment-and-labels-faa-grossly-insufficient/2020/03/06/9e336b9e-5fce-11ea-b014-4fafa866bb81_story.html .

Economy, P. (2019). Boeing CEO Puts Partial Blame on Pilots of Crashed 737 MAX Aircraft for Not 'Completely' Following Procedures. Inc., April 30, https://www.inc.com/peter-economy/boeing-ceo-puts-partial-blame-on-pilots-of-crashed-737-max-aircraft-for-not-completely-following-procedures.html .

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). (2018a). Airworthiness directives; the Boeing company airplanes. FR Doc No: R1-2018-26365. https://rgl.faa.gov/Regulatory_and_Guidance_Library/rgad.nsf/0/fe8237743be9b8968625835b004fc051/$FILE/2018-23-51_Correction.pdf .

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). (2018b). Quantitative Risk Assessment. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6573544-Risk-Assessment-for-Release-1.html#document/p1 .

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). (2019). Joint authorities technical review: observations, findings, and recommendations. October 11, https://www.faa.gov/news/media/attachments/Final_JATR_Submittal_to_FAA_Oct_2019.pdf .

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. (2019). Aircraft accident investigation preliminary report. Report No. AI-01/19, April 4, https://leehamnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Preliminary-Report-B737-800MAX-ET-AVJ.pdf .

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. (2020). Aircraft Accident Investigation Interim Report. Report No. AI-01/19, March 20, https://www.aib.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2020/documents/accident/ET-302%2520%2520Interim%2520Investigation%2520%2520Report%2520March%25209%25202020.pdf .

Gates, D. (2018). Pilots struggled against Boeing's 737 MAX control system on doomed Lion Air flight. The Seattle Times, November 27, https://www.seattletimes.com/business/boeing-aerospace/black-box-data-reveals-lion-air-pilots-struggle-against-boeings-737-max-flight-control-system/ .

Gates, D. (2019). Flawed analysis, failed oversight: how Boeing, FAA Certified the Suspect 737 MAX Flight Control System. The Seattle Times, March 17, https://www.seattletimes.com/business/boeing-aerospace/failed-certification-faa-missed-safety-issues-in-the-737-max-system-implicated-in-the-lion-air-crash/ .

Gelles, D. (2019). Boeing can’t fly its 737 MAX, but it’s ready to sell its safety. The New York Times, December 24 (updated February 10, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/24/business/boeing-737-max-survey.html .

Gelles, D. (2020). Boeing expects 737 MAX costs will surpass $18 Billion. The New York Times, January 29, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/29/business/boeing-737-max-costs.html .

Gelles, D., & Kaplan, T. (2019). F.A.A. Approval of Boeing jet involved in two crashes comes under scrutiny. The New York Times, March 19, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/19/business/boeing-elaine-chao.html .

Gelles, D., & Kitroeff, N. (2019a). Boeing Believed a 737 MAX warning light was standard. It wasn’t. New York: The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/05/business/boeing-737-max-warning-light.html .

Gelles, D., & Kitroeff, N. (2019b). Boeing board to call for safety changes after 737 MAX Crashes. The New York Times, September 15, (updated October 2), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/15/business/boeing-safety-737-max.html .

Gelles, D., & Kitroeff, N. (2019c). Boeing pilot complained of ‘Egregious’ issue with 737 MAX in 2016. The New York Times, October 18, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/18/business/boeing-flight-simulator-text-message.html .

Gelles, D., & Kitroeff, N. (2020). What needs to happen to get Boeing’s 737 MAX flying again?. The New York Times, February 10, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/10/business/boeing-737-max-fly-again.html .

Gelles, D., Kitroeff, N., Nicas, J., & Ruiz, R. R. (2019). Boeing was ‘Go, Go, Go’ to beat airbus with the 737 MAX. The New York Times, March 23, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/23/business/boeing-737-max-crash.html .

Glanz, J., Creswell, J., Kaplan, T., & Wichter, Z. (2019). After a Lion Air 737 MAX Crashed in October, Questions About the Plane Arose. The New York Times, February 3, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/03/world/asia/lion-air-plane-crash-pilots.html .

Gotterbarn, D., & Miller, K. W. (2009). The public is the priority: Making decisions using the software engineering code of ethics. Computer, 42 (6), 66–73.

Hall, J., & Goelz, P. (2019). The Boeing 737 MAX Crisis Is a Leadership Failure, The New York Times, July 17, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/17/opinion/boeing-737-max.html .

Harris, C. E. (2008). The good engineer: Giving virtue its due in engineering ethics. Science and Engineering Ethics, 14 (2), 153–164.

Hashemian, G., & Loui, M. C. (2010). Can instruction in engineering ethics change students’ feelings about professional responsibility? Science and Engineering Ethics, 16 (1), 201–215.

Herkert, J. R. (1997). Collaborative learning in engineering ethics. Science and Engineering Ethics, 3 (4), 447–462.

Herkert, J. R. (2004). Microethics, macroethics, and professional engineering societies. In Emerging technologies and ethical issues in engineering: papers from a workshop (pp. 107–114). National Academies Press, New York.

Hess, J. L., & Fore, G. (2018). A systematic literature review of US engineering ethics interventions. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24 (2), 551–583.

House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure (House TI). (2020). The Boeing 737 MAX Aircraft: Costs, Consequences, and Lessons from its Design, Development, and Certification-Preliminary Investigative Findings, March. https://transportation.house.gov/imo/media/doc/TI%2520Preliminary%2520Investigative%2520Findings%2520Boeing%2520737%2520MAX%2520March%25202020.pdf .

IEEE. (2017). IEEE Code of Ethics. https://www.ieee.org/about/corporate/governance/p7-8.html .

IEEE. (2018). Ethically Aligned Design: A Vision for Prioritizing Human Well-being with Autonomous and Intelligent Systems (version 2). https://standards.ieee.org/content/dam/ieee-standards/standards/web/documents/other/ead_v2.pdf .

Jennings, M., & Trautman, L. J. (2016). Ethical culture and legal liability: The GM switch crisis and lessons in governance. Boston University Journal of Science and Technology Law, 22 , 187.

Johnston, P., & Harris, R. (2019). The Boeing 737 MAX Saga: Lessons for software organizations. Software Quality Professional, 21 (3), 4–12.

Josephs, L. (2019). FAA tightens grip on Boeing with plan to individually review each new 737 MAX Jetliner. CNBC, November 27, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/27/faa-tightens-grip-on-boeing-with-plan-to-individually-inspect-max-jets.html .

Kaplan, T., Austen, I., & Gebrekidan, S. (2019). The New York Times, March 13. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/13/business/canada-737-max.html .

Kitroeff, N. (2019). Boeing underestimated cockpit chaos on 737 MAX, N.T.S.B. Says. The New York Times, September 26, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/26/business/boeing-737-max-ntsb-mcas.html .

Kitroeff, N., & Gelles, D. (2019). Legislators call on F.A.A. to say why it overruled its experts on 737 MAX. The New York Times, November 7 (updated December 11), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/07/business/boeing-737-max-faa.html .

Kitroeff, N., & Gelles, D. (2020). It’s not just software: New safety risks under scrutiny on Boeing’s 737 MAX. The New York Times, January 5, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/05/business/boeing-737-max.html .

Kitroeff, N., & Schmidt, M. S. (2020). Federal prosecutors investigating whether Boeing pilot lied to F.A.A. The New York Times, February 21, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/21/business/boeing-737-max-investigation.html .

Kitroeff, N., Gelles, D., & Nicas, J. (2019a). The roots of Boeing’s 737 MAX Crisis: A regulator relaxes its oversight. The New York Times, July 27, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/27/business/boeing-737-max-faa.html .

Kitroeff, N., Gelles, D., & Nicas, J. (2019b). Boeing 737 MAX safety system was vetoed, Engineer Says. The New York Times, October 2, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/02/business/boeing-737-max-crashes.html .

Kline, R. R. (2001). Using history and sociology to teach engineering ethics. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, 20 (4), 13–20.

Koenig, D. (2019). Boeing, FAA both faulted in certification of the 737 MAX. AP, October 11, https://apnews.com/470abf326cdb4229bdc18c8ad8caa78a .

Langewiesche, W. (2019). What really brought down the Boeing 737 MAX? The New York Times, September 18, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/18/magazine/boeing-737-max-crashes.html .

Leveson, N. G., & Turner, C. S. (1993). An investigation of the Therac-25 accidents. Computer, 26 (7), 18–41.

Marks, S., & Dahir, A. L. (2020). Ethiopian report on 737 Max Crash Blames Boeing, March 9, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/09/world/africa/ethiopia-crash-boeing.html .

Martin, D. A., Conlon, E., & Bowe, B. (2019). The role of role-play in student awareness of the social dimension of the engineering profession. European Journal of Engineering Education, 44 (6), 882–905.

Miller, G. (2019). Toward lifelong excellence: navigating the engineering-business space. In The Engineering-Business Nexus (pp. 81–101). Springer, Cham.

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). (2019). Safety Recommendations Report, September 19, https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/ASR1901.pdf .

Nissenbaum, H. (1994). Computing and accountability. Communications of the ACM , January, https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/175222.175228 .

Nissenbaum, H. (1996). Accountability in a computerized society. Science and Engineering Ethics, 2 (1), 25–42.

Noorman, M. (2020). Computing and moral responsibility. In Zalta, E. N. (Ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/computing-responsibility .

Pasztor, A. (2019). More Whistleblower complaints emerge in Boeing 737 MAX Safety Inquiries. The Wall Street Journal, April 27, https://www.wsj.com/articles/more-whistleblower-complaints-emerge-in-boeing-737-max-safety-inquiries-11556418721 .

Pasztor, A., & Cameron, D. (2020). U.S. News: Panel Backs How FAA gave safety approval for 737 MAX. The Wall Street Journal, January 17, https://www.wsj.com/articles/panel-clears-737-maxs-safety-approval-process-at-faa-11579188086 .

Pasztor, A., Cameron.D., & Sider, A. (2020). Boeing backs MAX simulator training in reversal of stance. The Wall Street Journal, January 7, https://www.wsj.com/articles/boeing-recommends-fresh-max-simulator-training-11578423221 .

Peters, D., Vold, K., Robinson, D., & Calvo, R. A. (2020). Responsible AI—two frameworks for ethical design practice. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society, 1 (1), 34–47.

Peterson, M. (2019). The ethical failures behind the Boeing disasters. Blog of the APA, April 8, https://blog.apaonline.org/2019/04/08/the-ethical-failures-behind-the-boeing-disasters/ .

Pinkus, R. L., Pinkus, R. L. B., Shuman, L. J., Hummon, N. P., & Wolfe, H. (1997). Engineering ethics: Balancing cost, schedule, and risk-lessons learned from the space shuttle . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Republic of Indonesia. (2019). Final Aircraft Accident Investigation Report. KNKT.18.10.35.04, https://knkt.dephub.go.id/knkt/ntsc_aviation/baru/2018%2520-%2520035%2520-%2520PK-LQP%2520Final%2520Report.pdf .

Rich, G. (2019). Boeing 737 MAX should return in 2020 but the crisis won't be over. Investor's Business Daily, December 31, https://www.investors.com/news/boeing-737-max-service-return-2020-crisis-not-over/ .

Schnebel, E., & Bienert, M. A. (2004). Implementing ethics in business organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 53 (1–2), 203–211.

Schwartz, M. S. (2013). Developing and sustaining an ethical corporate culture: The core elements. Business Horizons, 56 (1), 39–50.

Stephan, K. (2016). GM Ignition Switch Recall: Too Little Too Late? [Ethical Dilemmas]. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, 35 (2), 34–35.

Sullenberger, S. (2019). My letter to the editor of New York Times Magazine, https://www.sullysullenberger.com/my-letter-to-the-editor-of-new-york-times-magazine/ .

Thompson, D. F. (1980). Moral responsibility of public officials: The problem of many hands. American Political Science Review, 74 (4), 905–916.

Thompson, D. F. (2014). Responsibility for failures of government: The problem of many hands. The American Review of Public Administration, 44 (3), 259–273.

Tkacik, M. (2019). Crash course: how Boeing’s managerial revolution created the 737 MAX Disaster. The New Republic, September 18, https://newrepublic.com/article/154944/boeing-737-max-investigation-indonesia-lion-air-ethiopian-airlines-managerial-revolution .

Travis, G. (2019). How the Boeing 737 MAX disaster looks to a software developer. IEEE Spectrum , April 18, https://spectrum.ieee.org/aerospace/aviation/how-the-boeing-737-max-disaster-looks-to-a-software-developer .

Useem, J. (2019). The long-forgotten flight that sent Boeing off course. The Atlantic, November 20, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/11/how-boeing-lost-its-bearings/602188/ .

Watts, L. L., & Buckley, M. R. (2017). A dual-processing model of moral whistleblowing in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 146 (3), 669–683.

Werhane, P. H. (1991). Engineers and management: The challenge of the Challenger incident. Journal of Business Ethics, 10 (8), 605–616.

Download references

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA

Joseph Herkert

Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA

Jason Borenstein

University of Missouri – St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA

Keith Miller

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joseph Herkert .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Herkert, J., Borenstein, J. & Miller, K. The Boeing 737 MAX: Lessons for Engineering Ethics. Sci Eng Ethics 26 , 2957–2974 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00252-y

Download citation

Received : 26 March 2020

Accepted : 25 June 2020

Published : 10 July 2020

Issue Date : December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00252-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Engineering ethics

- Airline safety

- Engineering design

- Corporate culture

- Software engineering

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )

Videos Concepts Unwrapped View All 36 short illustrated videos explain behavioral ethics concepts and basic ethics principles. Concepts Unwrapped: Sports Edition View All 10 short videos introduce athletes to behavioral ethics concepts. Ethics Defined (Glossary) View All 58 animated videos - 1 to 2 minutes each - define key ethics terms and concepts. Ethics in Focus View All One-of-a-kind videos highlight the ethical aspects of current and historical subjects. Giving Voice To Values View All Eight short videos present the 7 principles of values-driven leadership from Gentile's Giving Voice to Values. In It To Win View All A documentary and six short videos reveal the behavioral ethics biases in super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff's story. Scandals Illustrated View All 30 videos - one minute each - introduce newsworthy scandals with ethical insights and case studies. Video Series

Case Study UT Star Icon

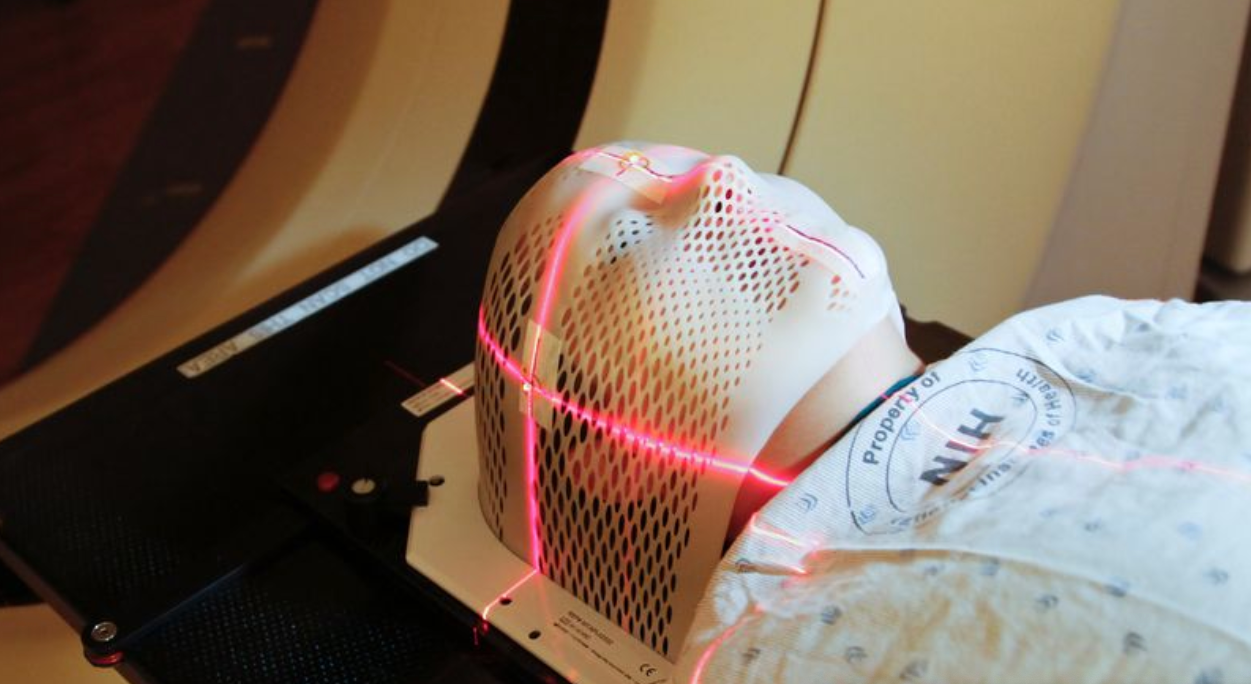

Providing radiation therapy to cancer patients, Therac-25 had malfunctions that resulted in 6 deaths. Who is accountable when technology causes harm?

The Therac-25 machine was a state-of-the-art linear accelerator developed by the company Atomic Energy Canada Limited (AECL) and a French company CGR to provide radiation treatment to cancer patients. The Therac-25 was the most computerized and sophisticated radiation therapy machine of its time. With the aid of an onboard computer, the device could select multiple treatment table positions and select the type/strength of the energy selected by the operating technician. AECL sold eleven Therac-25 machines that were used in the United States and Canada beginning in 1982.

Unfortunately, six accidents involving significant overdoses of radiation to patients resulting in death occurred between 1985 and 1987 (Leveson & Turner 1993). Patients reported being “burned by the machine” which some technicians reported, but the company thought was impossible. The machine was recalled in 1987 for an extensive redesign of safety features, software, and mechanical interlocks. Reports to the manufacturer resulted in inadequate repairs to the system and assurances that the machines were safe. Lawsuits were filed, and no investigations took place. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) later found that there was an inadequate reporting structure in the company, to follow up with reported accidents.

There were two earlier versions of the Therac-25 unit: the Therac-6 and the Therac-20, which were built from the CGR company’s other radiation units–Neptune and Sagittaire. The Therac-6 and Therac-20 units were built with a microcomputer that made the patient data entry more accessible, but the units were operational without an onboard computer. These units had built-in safety interlocks and positioning guides, and mechanical features that prevented radiation exposure if there was a positioning problem with the patient or with the components of the machine. There was some “base duplication” of the software used from the Therac-20 that carried over to the Therac-25. The Therac-6 and Therac-20 were clinically tested machines with an excellent safety record. They relied primarily on hardware for safety controls, whereas the Therac-25 relied primarily on software.

On February 6, 1987, the FDA placed a shutdown on all machines until permanent repairs could be made. Although the AECL was quick to state that a “fix” was in place, and the machines were now safer, that was not the case. After this incident, Leveson and Turner (1993) compiled public information from AECL, the FDA, and various regulatory agencies and concluded that there was inadequate record keeping when the software was designed. The software was inadequately tested, and “patches” were used from earlier versions of the machine. The premature assumption that the problem(s) was detected and corrected was unproven. Furthermore, AECL had great difficulty reproducing the conditions under which the issues were experienced in the clinics. The FDA restructured its reporting requirements for radiation equipment after these incidents.

As computers become more and more ubiquitous and control increasingly significant and complex systems, people are exposed to increasing harms and risks. The issue of accountability arises when a community expects its agents to stand up for the quality of their work. Nissenbaum (1994) argues that responsibility in our computerized society is systematically undermined, and this is a disservice to the community. This concern has grown with the number of critical life services controlled by computer systems in the governmental, airline, and medical arenas.

According to Nissenbaum, there are four barriers to accountability: the problem of many hands, “bugs” in the system, the computer as a scapegoat, and ownership without liability. The problem of too many hands relates to the fact that many groups of people (programmers, engineers, etc.) at various levels of a company are typically involved in creation of a computer program and have input into the final product. When something goes wrong, there is no one individual who can be clearly held responsible. It is easy for each person involved to rationalize that he or she is not responsible for the final outcome, because of the small role played. This occurred with the Therac-25 that had two prominent software errors, a failed microswitch, and a reduced number of safety features compared to earlier versions of the device. The problem of bugs in the software system causing errors in machines under certain conditions has been used as a cover for careless programming, lack of testing, and lack of safety features built into the system in the Therac-25 accident. The fact that computers “always have problems with their programming” cannot be used as an excuse for overconfidence in a product, unclear/ambiguous error messages, or improper testing of individual components of the system. Another potential obstacle is ownership of proprietary software and an unwillingness to share “trade secrets” with investigators whose job it is to protect the public (Nissenbaum 1994).

The Therac-25 incident involved what has been called one of the worst computer bugs in history (Lynch 2017), though it was largely a matter of overall design issues rather than a specific coding error. Therac-25 is a glaring example of what can go wrong in a society that is heavily dependent on technology.

Discussion Questions

1. Who should be responsible for the errors in a medical device?

2. What moral responsibility do creators of software have for the adverse consequences that flow from flaws in that software?

3. What steps are creators of software morally required to take to minimize the risk that they will sell flawed software with dangerous consequences?

4. What should constitute FDA approval of a medical device?

- Should the benefit outweigh the harm?

- Should the device be 100% safe prior to approval?

- Should FDA approval guidelines take into consideration novel therapies for protected populations such as children or patients with rare conditions?

5. Should updated medical devices be reviewed by the FDA as a new device or as an improvement in an older design?

- If reviewed as an improvement, at what point can/should a device be subject to a full review process?

- If reviewed as a novel device, how might this effect the production of modified/ improved devices and the overall companies that produce medical devices?

Related Videos

Causing Harm

Causing harm explores the types of harm that may be caused to people or groups and the potential reasons we may have for justifying these harms.

Bibliography

Gotterbarn, Donald, “Software Engineering Ethics,” Encyclopedia of Software Engineering (2002), https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/0471028959.sof314 .

Leveson, Nancy & Turner, Clark, “An Investigation of the Therac-25 Accidents,” Computer 26:7, p. 18 (July 19993), https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs240/old/sp2014/readings/therac-25.pdf

Leveson, Nancy, Medical Devices: The Therac—25 (1995), http://sunnyday.mit.edu/papers/therac.pdf .

Lynch, Jamie, “Therac-25 Causes Radiation Overdoses,” Bugsnag Blog ( 2017) https://www.bugsnag.com/blog/bug-day-race-condition-therac-25

Nissenbaum, Helen, “Computing and Accountability,“ Communications of the ACM , 37:1, p. 73 ( 1994). http://delivery.acm.org/10.1145/180000/175228/p72-nissenbaum.pdf?ip=128.62.211.38&id=175228&acc=ACTIVE%20SERVICE&key=603D2E7028CD4EF5%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35&__acm__=1576603038_0292b9d0b31643bd7b06dde8efa509f7

Stay Informed

Support our work.

- Dean’s Office

- External Advisory Council

- Computing Council

- Extended Computing Council

- Undergraduate Advisory Group

- Break Through Tech AI

- Building 45 Event Space

- Infinite Mile Awards: Past Winners

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Undergraduate Programs

- Graduate Programs

- Educating Computing Bilinguals

- Online Learning

- Industry Programs

- AI Policy Briefs

- Envisioning the Future of Computing Prize

- SERC Symposium 2023

- SERC Case Studies

- SERC Scholars Program

- SERC Postdocs

- Common Ground Subjects

- For First-Year Students and Advisors

- For Instructors: About Common Ground Subjects

- Common Ground Award for Excellence in Teaching

- New and Incoming Faculty

- Faculty Resources

- Faculty Openings

- Search for: Search

- MIT Homepage

Case Studies in Social and Ethical Responsibilities of Computing

The MIT Case Studies in Social and Ethical Responsibilities of Computing (SERC) aims to advance new efforts within and beyond the Schwarzman College of Computing. The specially commissioned and peer-reviewed cases are brief and intended to be effective for undergraduate instruction across a range of classes and fields of study, and may also be of interest for computing professionals, policy specialists, and general readers. The series editors interpret “social and ethical responsibilities of computing” broadly. Some cases focus closely on particular technologies, others on trends across technological platforms. Others examine social, historical, philosophical, legal, and cultural facets that are essential for thinking critically about present-day efforts in computing activities. Special efforts are made to solicit cases on topics ranging beyond the United States and that highlight perspectives of people who are affected by various technologies in addition to perspectives of designers and engineers. New sets of case studies, produced with support from the MIT Press’ Open Publishing Services program, will be published twice a year and made available via the Knowledge Futures Group’s PubPub platform. The SERC case studies are made available for free on an open-access basis , under Creative Commons licensing terms. Authors retain copyright, enabling them to re-use and re-publish their work in more specialized scholarly publications. If you have suggestions for a new case study or comments on a published case, the series editors would like to hear from you! Please reach out to [email protected] .

Winter 2024

Integrals and Integrity: Generative AI Tries to Learn Cosmology

How Interpretable Is “Interpretable” Machine Learning?

AI’s Regimes of Representation: A Community-Centered Study of Text-to-Image Models in South Asia

Past issues, summer 2023.

Pretrial Risk Assessment on the Ground: Algorithms, Judgments, Meaning, and Policy by Cristopher Moore, Elise Ferguson, and Paul Guerin