30 Examples: How to Conclude a Presentation (Effective Closing Techniques)

By Status.net Editorial Team on March 4, 2024 — 9 minutes to read

Ending a presentation on a high note is a skill that can set you apart from the rest. It’s the final chance to leave an impact on your audience, ensuring they walk away with the key messages embedded in their minds. This moment is about driving your points home and making sure they resonate. Crafting a memorable closing isn’t just about summarizing key points, though that’s part of it, but also about providing value that sticks with your listeners long after they’ve left the room.

Crafting Your Core Message

To leave a lasting impression, your presentation’s conclusion should clearly reflect your core message. This is your chance to reinforce the takeaways and leave the audience thinking about your presentation long after it ends.

Identifying Key Points

Start by recognizing what you want your audience to remember. Think about the main ideas that shaped your talk. Make a list like this:

- The problem your presentation addresses.

- The evidence that supports your argument.

- The solution you propose or the action you want the audience to take.

These key points become the pillars of your core message.

Contextualizing the Presentation

Provide context by briefly relating back to the content of the whole presentation. For example:

- Reference a statistic you shared in the opening, and how it ties into the conclusion.

- Mention a case study that underlines the importance of your message.

Connecting these elements gives your message cohesion and makes your conclusion resonate with the framework of your presentation.

30 Example Phrases: How to Conclude a Presentation

- 1. “In summary, let’s revisit the key takeaways from today’s presentation.”

- 2. “Thank you for your attention. Let’s move forward together.”

- 3. “That brings us to the end. I’m open to any questions you may have.”

- 4. “I’ll leave you with this final thought to ponder as we conclude.”

- 5. “Let’s recap the main points before we wrap up.”

- 6. “I appreciate your engagement. Now, let’s turn these ideas into action.”

- 7. “We’ve covered a lot today. To conclude, remember these crucial points.”

- 8. “As we reach the end, I’d like to emphasize our call to action.”

- 9. “Before we close, let’s quickly review what we’ve learned.”

- 10. “Thank you for joining me on this journey. I look forward to our next steps.”

- 11. “In closing, I’d like to thank everyone for their participation.”

- 12. “Let’s conclude with a reminder of the impact we can make together.”

- 13. “To wrap up our session, here’s a brief summary of our discussion.”

- 14. “I’m grateful for the opportunity to present to you. Any final thoughts?”

- 15. “And that’s a wrap. I welcome any final questions or comments.”

- 16. “As we conclude, let’s remember the objectives we’ve set today.”

- 17. “Thank you for your time. Let’s apply these insights to achieve success.”

- 18. “In conclusion, your feedback is valuable, and I’m here to listen.”

- 19. “Before we part, let’s take a moment to reflect on our key messages.”

- 20. “I’ll end with an invitation for all of us to take the next step.”

- 21. “As we close, let’s commit to the goals we’ve outlined today.”

- 22. “Thank you for your attention. Let’s keep the conversation going.”

- 23. “In conclusion, let’s make a difference, starting now.”

- 24. “I’ll leave you with these final words to consider as we end our time together.”

- 25. “Before we conclude, remember that change starts with our actions today.”

- 26. “Thank you for the lively discussion. Let’s continue to build on these ideas.”

- 27. “As we wrap up, I encourage you to reach out with any further questions.”

- 28. “In closing, I’d like to express my gratitude for your valuable input.”

- 29. “Let’s conclude on a high note and take these learnings forward.”

- 30. “Thank you for your time today. Let’s end with a commitment to progress.”

Summarizing the Main Points

When you reach the end of your presentation, summarizing the main points helps your audience retain the important information you’ve shared. Crafting a memorable summary enables your listeners to walk away with a clear understanding of your message.

Effective Methods of Summarization

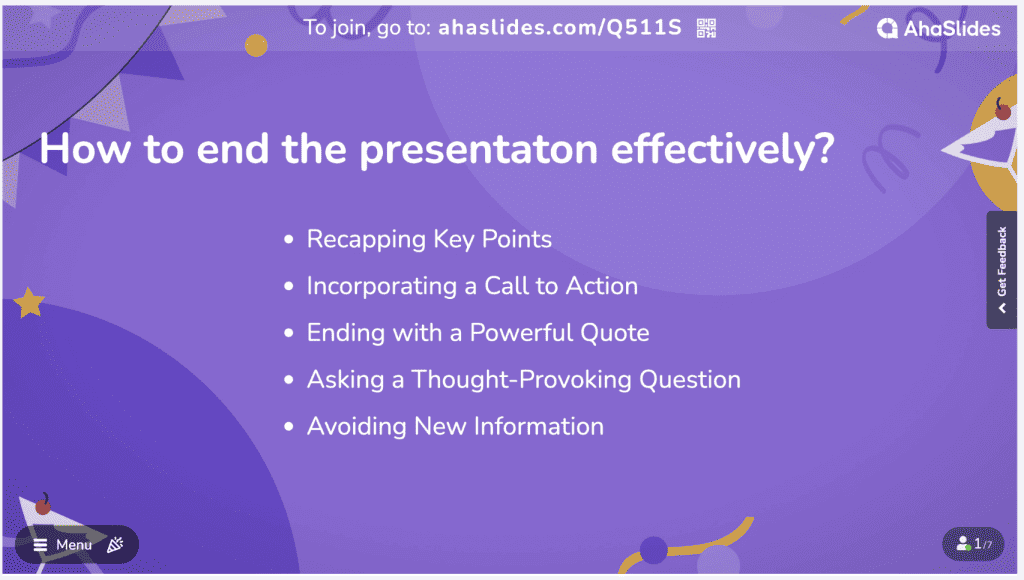

To effectively summarize your presentation, you need to distill complex information into concise, digestible pieces. Start by revisiting the overarching theme of your talk and then narrow down to the core messages. Use plain language and imagery to make the enduring ideas stick. Here are some examples of how to do this:

- Use analogies that relate to common experiences to recap complex concepts.

- Incorporate visuals or gestures that reinforce your main arguments.

The Rule of Three

The Rule of Three is a classic writing and communication principle. It means presenting ideas in a trio, which is a pattern that’s easy for people to understand and remember. For instance, you might say, “Our plan will save time, cut costs, and improve quality.” This structure has a pleasing rhythm and makes the content more memorable. Some examples include:

- “This software is fast, user-friendly, and secure.”

- Pointing out a product’s “durability, affordability, and eco-friendliness.”

Reiterating the Main Points

Finally, you want to circle back to the key takeaways of your presentation. Rephrase your main points without introducing new information. This reinforcement supports your audience’s memory and understanding of the material. You might summarize key takeaways like this:

- Mention the problem you addressed, the solution you propose, and the benefits of this solution.

- Highlighting the outcomes of adopting your strategy: higher efficiency, greater satisfaction, and increased revenue.

Creating a Strong Conclusion

The final moments of your presentation are your chance to leave your audience with a powerful lasting impression. A strong conclusion is more than just summarizing—it’s your opportunity to invoke thought, inspire action, and make your message memorable.

Incorporating a Call to Action

A call to action is your parting request to your audience. You want to inspire them to take a specific action or think differently as a result of what they’ve heard. To do this effectively:

- Be clear about what you’re asking.

- Explain why their action is needed.

- Make it as simple as possible for them to take the next steps.

Example Phrases:

- “Start making a difference today by…”

- “Join us in this effort by…”

- “Take the leap and commit to…”

Leaving a Lasting Impression

End your presentation with something memorable. This can be a powerful quote, an inspirational statement, or a compelling story that underscores your main points. The goal here is to resonate with your audience on an emotional level so that your message sticks with them long after they leave.

- “In the words of [Influential Person], ‘…'”

- “Imagine a world where…”

- “This is more than just [Topic]; it’s about…”

Enhancing Audience Engagement

To hold your audience’s attention and ensure they leave with a lasting impression of your presentation, fostering interaction is key.

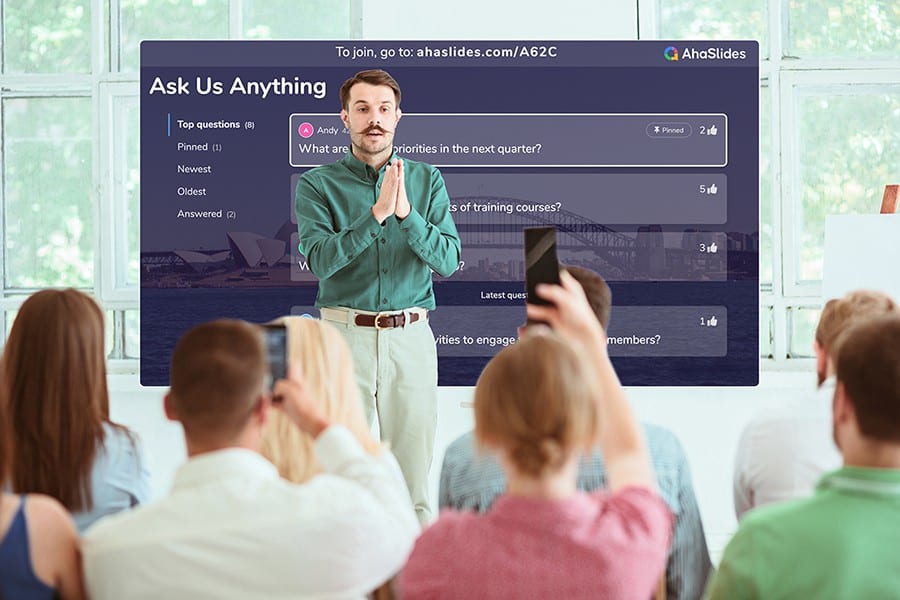

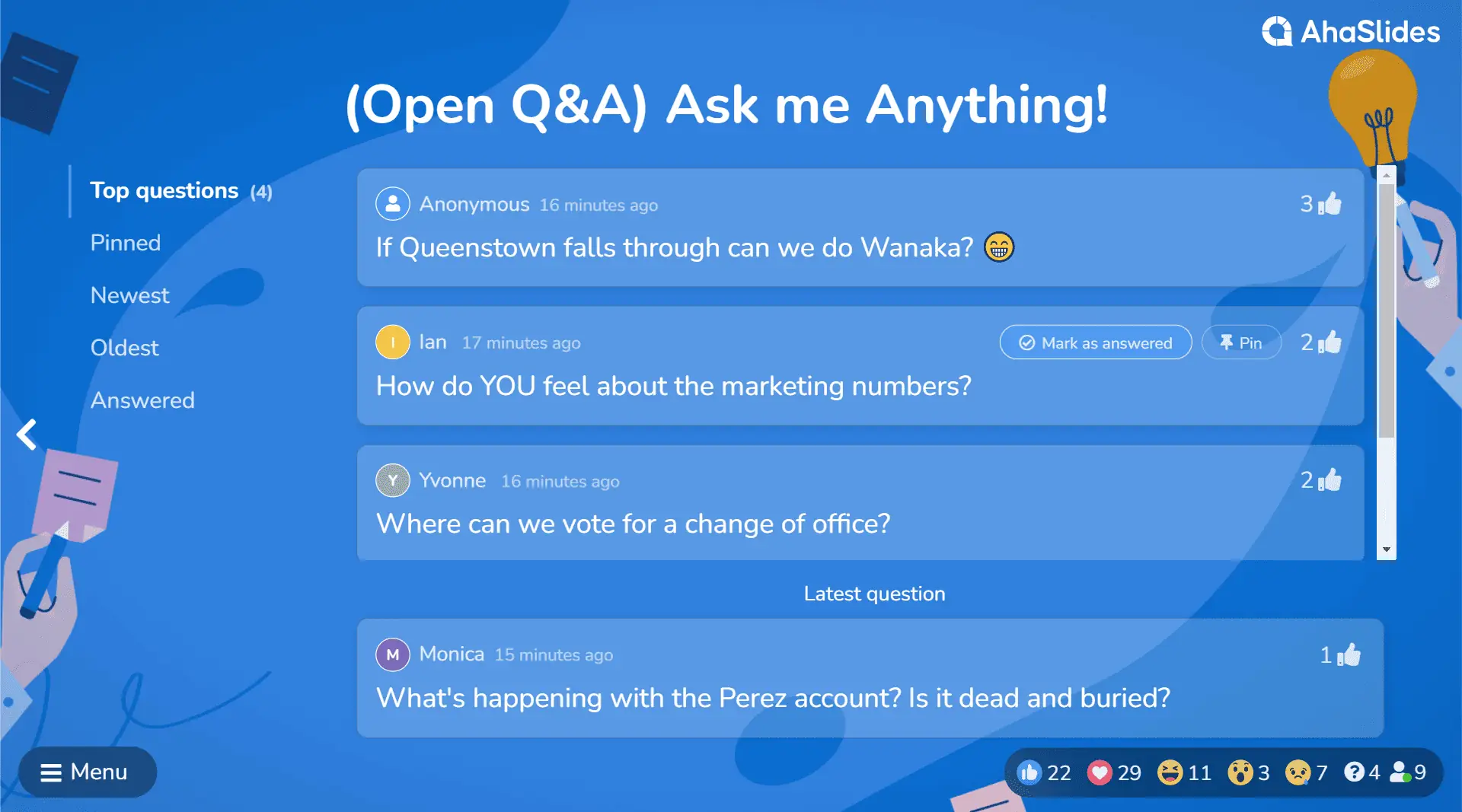

Q&A Sessions

It’s important to integrate a Q&A session because it allows for direct communication between you and your audience. This interactive segment helps clarify any uncertainties and encourages active participation. Plan for this by designating a time slot towards the end of your presentation and invite questions that promote discussion.

- “I’d love to hear your thoughts; what questions do you have?”

- “Let’s dive into any questions you might have. Who would like to start?”

- “Feel free to ask any questions, whether they’re clarifications or deeper inquiries about the topic.”

Encouraging Audience Participation

Getting your audience involved can transform a good presentation into a great one. Use open-ended questions that provoke thought and allow audience members to reflect on how your content relates to them. Additionally, inviting volunteers to participate in a demonstration or share their experiences keeps everyone engaged and adds a personal touch to your talk.

- “Could someone give me an example of how you’ve encountered this in your work?”

- “I’d appreciate a volunteer to help demonstrate this concept. Who’s interested?”

- “How do you see this information impacting your daily tasks? Let’s discuss!”

Delivering a Persuasive Ending

At the end of your presentation, you have the power to leave a lasting impact on your audience. A persuasive ending can drive home your key message and encourage action.

Sales and Persuasion Tactics

When you’re concluding a presentation with the goal of selling a product or idea, employ carefully chosen sales and persuasion tactics. One method is to summarize the key benefits of your offering, reminding your audience why it’s important to act. For example, if you’ve just presented a new software tool, recap how it will save time and increase productivity. Another tactic is the ‘call to action’, which should be clear and direct, such as “Start your free trial today to experience the benefits first-hand!” Furthermore, using a touch of urgency, like “Offer expires soon!”, can nudge your audience to act promptly.

Final Impressions and Professionalism

Your closing statement is a chance to solidify your professional image and leave a positive impression. It’s important to display confidence and poise. Consider thanking your audience for their time and offering to answer any questions. Make sure to end on a high note by summarizing your message in a concise and memorable way. If your topic was on renewable energy, you might conclude by saying, “Let’s take a leap towards a greener future by adopting these solutions today.” This reinforces your main points and encourages your listeners to think or act differently when they leave.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some creative strategies for ending a presentation memorably.

To end your presentation in a memorable way, consider incorporating a call to action that engages your audience to take the next step. Another strategy is to finish with a thought-provoking question or a surprising fact that resonates with your listeners.

Can you suggest some powerful quotes suitable for concluding a presentation?

Yes, using a quote can be very effective. For example, Maya Angelou’s “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel,” can reinforce the emotional impact of your presentation.

What is an effective way to write a conclusion that summarizes a presentation?

An effective conclusion should recap the main points succinctly, highlighting what you want your audience to remember. A good way to conclude is by restating your thesis and then briefly summarizing the supporting points you made.

As a student, how can I leave a strong impression with my presentation’s closing remarks?

To leave a strong impression, consider sharing a personal anecdote related to your topic that demonstrates passion and conviction. This helps humanize your content and makes the message more relatable to your audience.

How can I appropriately thank my audience at the close of my presentation?

A simple and sincere expression of gratitude is always appropriate. You might say, “Thank you for your attention and engagement today,” to convey appreciation while also acknowledging their participation.

What are some examples of a compelling closing sentence in a presentation?

A compelling closing sentence could be something like, “Together, let’s take the leap towards a greener future,” if you’re presenting on sustainability. This sentence is impactful, calls for united action, and leaves your audience with a clear message.

- How to Build Rapport: Effective Techniques

- Active Listening (Techniques, Examples, Tips)

- Effective Nonverbal Communication in the Workplace (Examples)

- What is Problem Solving? (Steps, Techniques, Examples)

- 2 Examples of an Effective and Warm Letter of Welcome

- Effective Interview Confirmation Email (Examples)

- By Illiya Vjestica

- - January 23, 2023

10 Powerful Examples of How to End a Presentation

Here are 10 powerful examples of how to end a presentation that does not end with a thank you slide.

How many presentations have you seen that end with “Thank you for listening” or “Any questions?” I bet it’s a lot…

“Thank you for listening.” is the most common example. Unfortunately, when it comes to closing out your slides ending with “thank you” is the norm. We can create a better presentation ending by following these simple examples.

The two most essential slides of your deck are the ending and intro. An excellent presentation ending is critical to helping the audience to the next step or following a specific call to action.

There are many ways you can increase your presentation retention rate . The most critical steps are having a solid call to action at the end of your presentation and a powerful hook that draws your audience in.

What Action do You Want Your Audience to Take?

Before designing your presentation, start with this question – what message or action will you leave your audience with?

Are you looking to persuade, inspire, entertain or inform your audience? You can choose one or multiple words to describe the intent of your presentation.

Think about the action words that best describe your presentation ending – what do you want them to do? Inspire, book, learn, understand, engage, donate, buy, book or schedule. These are a few examples.

If the goal of your presentation is to inspire, why not end with a powerful and inspiring quote ? Let words of wisdom be the spark that ignites an action within your audience.

Here are three ways to end your presentation:

- Call to Action – getting the audience to take a specific action or next step, for example, booking a call, signing up for an event or donating to your cause.

- Persuade – persuading your audience to think differently, try something new, undertake a challenge or join your movement or community.

- Summarise – A summary of the key points and information you want the audience to remember. If you decide to summarise your talk at the end, keep it to no more than three main points.

10 Examples of How to End a Presentation

1. Asking your audience to take action or make a pledge.

Here were asking the audience to take action by using the wording “take action” in our copy. This call to action is a pledge to donate. A clear message like this can be helpful for charities and non-profits looking to raise funding for their campaign or cause.

2. Encourage your audience to take a specific action, e.g. joining your cause or community

Here was are asking the audience to join our community and help solve a problem by becoming part of the solution. It’s a simple call to action. You can pass the touch to your audience and ask them to take the next lead.

3. Highlight the critical points for your audience to remember.

Rember, to summarise your presentation into no more than three key points. This is important because the human brain struggles to remember more than three pieces of information simultaneously. We call this the “Rule of Three”.

4. If you are trying to get more leads or sales end with a call to action to book a demo or schedule a call.

Can you inspire your audience to sign up for a demo or trial of your product? Structure your talk to lead your prospect through a journey of the results you generate for other clients. At the end of your deck, finish with a specific call to action, such as “Want similar results to X?”

Make sure you design a button, or graphic your prospect can click on when you send them the PDF version of the slides.

5. Challenge your audience to think differently or take action, e.g. what impact could they make?

6. Give your audience actions to help share your message.

7. Promote your upcoming events or workshops

8. Asking your audience to become a volunteer.

9. Direct your audience to learn more about your website.

10. If you are a book author, encourage your audience to engage with your book.

6 Questions to Generate an Ending for Your Presentation

You’ve told an engaging story, but why end your presentation without leaving your audience a clear message or call to action?

Here are six great questions you can ask yourself to generate an ending for your presentation or keynote talk.

- What impression would you want to leave your audience with?

- What is the big idea you want to leave them with?

- What action should they take next?

- What key point should you remember 72 hours after your presentation?

- What do you want them to feel?

- What is the key takeaway for them to understand?

What to Say After Ending a Presentation?

When you get to the end of a book, you don’t see the author say, “thank you for reading my last chapter.” Of course, there is no harm in thanking the audience after your presentation ends, but don’t make that the last words you speak.

Think of the ending of the presentation as the final chapter of an epic novel. It’s your chance to leave a lasting impression on the audience. Close with an impactful ending and leave them feeling empowered, invigorated and engaged.

- Leave a lasting impression.

- Think of it as the last chapter of a book.

- Conclude with a thought or question.

- Leave the audience with a specific action or next step.

How to End a Presentation with Style?

There are many great ways you can end your presentation with style. Are you ready to drop the mic?

Ensure your closing slide is punchy, has a clear headline, or uses a thought-provoking image.

Think about colours. You want to capture the audience’s attention before closing the presentation. Make sure the fonts you choose are clear and easy to read.

Do you need to consider adding a link? If you add links to your social media accounts, use icons and buttons to make them easy to see. Add a link to each button or icon. By doing this, if you send the PDF slides to people, they can follow the links to your various accounts.

What Should you Remember?

💡 If you take one thing away from this post, it’s to lose the traditional ending slides. Let’s move on from the “Thank you for your attention.” or “Any questions.” slides.

These don’t help you or the audience. Respect them and think about what they should do next. You may be interested to learn 3 Tactics to Free Your Presentation Style to help you connect to your audience.

Illiya Vjestica

Share this post:, leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Template Lists

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Beginner Guides

Blog Marketing

How To End A Presentation & Leave A Lasting Impression

By Krystle Wong , Aug 09, 2023

So you’ve got an exciting presentation ready to wow your audience and you’re left with the final brushstroke — how to end your presentation with a bang.

Just as a captivating opening draws your audience in, creating a well-crafted presentation closing has the power to leave a profound and lasting impression that resonates long after the lights dim and the audience disperses.

In this article, I’ll walk you through the art of crafting an impactful conclusion that resonates with 10 effective techniques and ideas along with real-life examples to inspire your next presentation. Alternatively, you could always jump right into creating your slides by customizing our professionally designed presentation templates . They’re fully customizable and require no design experience at all!

Click to jump ahead:

Why is it important to have an impactful ending for your presentation?

10 effective presentation closing techniques to leave a lasting impression, 7 things to put on a conclusion slide.

- 5 real-life exceptional examples of how to end a presentation

6 mistakes to avoid in concluding a presentation

Faqs on how to end a presentation, how to create a memorable presentation with venngage.

People tend to remember the beginning and end of a presentation more vividly than the middle, making the final moments your last chance to make a lasting impression.

An ending that leaves a lasting impact doesn’t merely mark the end of a presentation; it opens doors to further exploration. A strong conclusion is vital because it:

- Leaves a lasting impression on the audience.

- Reinforces key points and takeaways.

- Motivates action and implementation of ideas.

- Creates an emotional connection with the audience.

- Fosters engagement, curiosity and reflection.

Just like the final scene of a movie, your presentation’s ending has the potential to linger in your audience’s minds long after they’ve left the room. From summarizing key points to engaging the audience in unexpected ways, make a lasting impression with these 10 ways to end a presentation:

1. The summary

Wrap up your entire presentation with a concise and impactful summary, recapping the key points and main takeaways. By doing so, you reinforce the essential aspects and ensure the audience leaves with a crystal-clear understanding of your core message.

2. The reverse story

Here’s a cool one: start with the end result and then surprise the audience with the journey that led you to where you are. Share the challenges you conquered and the lessons you learned, making it a memorable and unique conclusion that drives home your key takeaways.

Alternatively, customize one of our cool presentation templates to capture the attention of your audience and deliver your message in an engaging and memorable way

3. The metaphorical prop

For an added visual touch, bring a symbolic prop that represents your message. Explain its significance in relation to your content, leaving the audience with a tangible and unforgettable visual representation that reinforces your key concepts.

4. The audience engagement challenge

Get the audience involved by throwing them a challenge related to your informational presentation. Encourage active participation and promise to share the results later, fostering their involvement and motivating them to take action.

5. The memorable statistic showcase

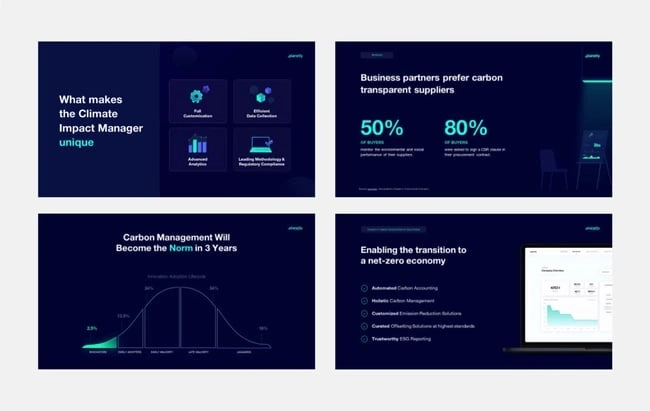

Spice things up with a series of surprising or intriguing statistics, presented with attention-grabbing visual aids. Summarize your main points using these impactful stats to ensure the audience remembers and grasps the significance of your data, especially when delivering a business presentation or pitch deck presentation .

Transform your data-heavy presentations into engaging presentations using data visualization tools. Venngage’s chart and graph tools help you present information in a digestible and visually appealing manner. Infographics and diagrams can simplify complex concepts while images add a relatable dimension to your presentation.

6. The interactive story creation

How about a collaborative story? Work with the audience to create an impromptu tale together. Let them contribute elements and build the story with you. Then, cleverly tie it back to your core message with a creative presentation conclusion.

7. The unexpected guest speaker

Introduce an unexpected guest who shares a unique perspective related to your presentation’s theme. If their story aligns with your message, it’ll surely amp up the audience’s interest and engagement.

8. The thought-provoking prompt

Leave your audience pondering with a thought-provoking question or prompt related to your topic. Encourage reflection and curiosity, sparking a desire to explore the subject further and dig deeper into your message.

9. The empowering call-to-action

Time to inspire action! Craft a powerful call to action that motivates the audience to make a difference. Provide practical steps and resources to support their involvement, empowering them to take part in something meaningful.

10. The heartfelt expression

End on a warm note by expressing genuine gratitude and appreciation for the audience’s time and attention. Acknowledge their presence and thank them sincerely, leaving a lasting impression of professionalism and warmth.

Not sure where to start? These 12 presentation software might come in handy for creating a good presentation that stands out.

Remember, your closing slides for the presentation is your final opportunity to make a strong impact on your audience. However, the question remains — what exactly should be on the last slide of your presentation? Here are 7 conclusion slide examples to conclude with a high note:

1. Key takeaways

Highlight the main points or key takeaways from your presentation. This reinforces the essential information you want the audience to remember, ensuring they leave with a clear understanding of your message with a well summarized and simple presentation .

2. Closing statement

Craft a strong closing statement that summarizes the overall message of your presentation and leaves a positive final impression. This concluding remark should be impactful and memorable.

3. Call-to-action

Don’t forget to include a compelling call to action in your final message that motivates the audience to take specific steps after the presentation. Whether it’s signing up for a newsletter, trying a product or conducting further research, a clear call to action can encourage engagement.

4. Contact information

Provide your contact details, such as email address or social media handles. That way, the audience can easily reach out for further inquiries or discussions. Building connections with your audience enhances engagement and opens doors for future opportunities.

Use impactful visuals or graphics to deliver your presentation effectively and make the conclusion slide visually appealing. Engaging visuals can captivate the audience and help solidify your key points.

Visuals are powerful tools for retention. Use Venngage’s library of icons, images and charts to complement your text. You can easily upload and incorporate your own images or choose from Venngage’s library of stock photos to add depth and relevance to your visuals.

6. Next steps

Outline the recommended next steps for the audience to take after the presentation, guiding them on what actions to pursue. This can be a practical roadmap for implementing your ideas and recommendations.

7. Inspirational quote

To leave a lasting impression, consider including a powerful and relevant quote that resonates with the main message of your presentation. Thoughtful quotes can inspire and reinforce the significance of your key points.

Whether you’re giving an in-person or virtual presentation , a strong wrap-up can boost persuasiveness and ensure that your message resonates and motivates action effectively. Check out our gallery of professional presentation templates to get started.

5 real-life exceptional examples of how to end a presentation

When we talk about crafting an exceptional closing for a presentation, I’m sure you’ll have a million questions — like how do you end a presentation, what do you say at the end of a presentation or even how to say thank you after a presentation.

To get a better idea of how to end a presentation with style — let’s delve into five remarkable real-life examples that offer valuable insights into crafting a conclusion that truly seals the deal:

1. Sheryl Sandberg

In her TED Talk titled “Why We Have Too Few Women Leaders,” Sheryl Sandberg concluded with an impactful call to action, urging men and women to lean in and support gender equality in the workplace. This motivational ending inspired the audience to take action toward a more inclusive world.

2. Elon Musk

Elon Musk often concludes with his vision for the future and how his companies are working towards groundbreaking advancements. His passion and enthusiasm for pushing the boundaries of technology leave the audience inspired and eager to witness the future unfold.

3. Barack Obama

President Obama’s farewell address concluded with an emotional and heartfelt expression of gratitude to the American people. He thanked the audience for their support and encouraged them to stay engaged and uphold the values that define the nation.

4. Brené Brown

In her TED Talk on vulnerability, Brené Brown ended with a powerful quote from Theodore Roosevelt: “It is not the critic who counts… The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena.” This quote reinforced her message about the importance of embracing vulnerability and taking risks in life.

5. Malala Yousafzai

In her Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, Malala Yousafzai ended with a moving call to action for education and girls’ rights. She inspired the audience to stand up against injustice and to work towards a world where every child has access to education.

For more innovative presentation ideas , turn ordinary slides into captivating experiences with these 15 interactive presentation ideas that will leave your audience begging for more.

So, we talked about how a good presentation usually ends. As you approach the conclusion of your presentation, let’s go through some of the common pitfalls you should avoid that will undermine the impact of your closing:

1. Abrupt endings

To deliver persuasive presentations, don’t leave your audience hanging with an abrupt conclusion. Instead, ensure a smooth transition by providing a clear closing statement or summarizing the key points to leave a lasting impression.

2. New information

You may be wondering — can I introduce new information or ideas in the closing? The answer is no. Resist the urge to introduce new data or facts in the conclusion and stick to reinforcing the main content presented earlier. By introducing new content at the end, you risk overshadowing your main message.

3. Ending with a Q&A session

While Q&A sessions are valuable , don’t conclude your presentation with them. Opt for a strong closing statement or call-to-action instead, leaving the audience with a clear takeaway.

4. Overloading your final slide

Avoid cluttering your final slide with too much information or excessive visuals. Keep it clean, concise and impactful to reinforce your key messages effectively.

5. Forgetting the call-to-action

Most presentations fail to include a compelling call-to-action which can diminish the overall impact of your presentation. To deliver a persuasive presentation, encourage your audience to take specific steps after the talk, driving engagement and follow-through.

6. Ignoring the audience

Make your conclusion audience-centric by connecting with their needs and interests. Avoid making it solely about yourself or your achievements. Instead, focus on how your message benefits the audience.

What should be the last slide of a presentation?

The last slide of a presentation should be a conclusion slide, summarizing key takeaways, delivering a strong closing statement and possibly including a call to action.

How do I begin a presentation?

Grabbing the audience’s attention at the very beginning with a compelling opening such as a relevant story, surprising statistic or thought-provoking question. You can even create a game presentation to boost interactivity with your audience. Check out this blog for more ideas on how to start a presentation .

How can I ensure a smooth transition from the body of the presentation to the closing?

To ensure a smooth transition, summarize key points from the body, use transition phrases like “In conclusion,” and revisit the main message introduced at the beginning. Bridge the content discussed to the themes of the closing and consider adjusting tone and pace to signal the transition.

How long should the conclusion of a presentation be?

The conclusion of a presentation should typically be around 5-10% of the total presentation time, keeping it concise and impactful.

Should you say thank you at the end of a presentation?

Yes, saying thank you at the end of a PowerPoint presentation is a courteous way to show appreciation for the audience’s time and attention.

Should I use presentation slides in the concluding part of my talk?

Yes, using presentation slides in the concluding part of your talk can be effective. Use concise slides to summarize key takeaways, reinforce your main points and deliver a strong closing statement. A final presentation slide can enhance the impact of your conclusion and help the audience remember your message.

Should I include a Q&A session at the end of the presentation?

Avoid Q&A sessions in certain situations to ensure a well-structured and impactful conclusion. It helps prevent potential time constraints and disruptions to your carefully crafted ending, ensuring your core message remains the focus without the risk of unanswered or off-topic questions diluting the presentation’s impact.

Is it appropriate to use humor in the closing of a presentation?

Using humor in the closing of a presentation can be appropriate if it aligns with your content and audience as it can leave a positive and memorable impression. However, it’s essential to use humor carefully and avoid inappropriate or offensive jokes.

How do I manage nervousness during the closing of a presentation?

To manage nervousness during the closing, focus on your key points and the main message you want to convey. Take deep breaths to calm your nerves, maintain eye contact and remind yourself that you’re sharing valuable insights to enhance your presentation skills.

Creating a memorable presentation is a blend of engaging content and visually captivating design. With Venngage, you can transform your ideas into a dynamic and unforgettable presentation in just 5 easy steps:

- Choose a template from Venngage’s library: Pick a visually appealing template that fits your presentation’s theme and audience, making it easy to get started with a professional look.

- Craft a compelling story or outline: Organize your content into a clear and coherent narrative or outline the key points to engage your audience and make the information easy to follow.

- Customize design and visuals: Tailor the template with your brand colors, fonts and captivating visuals like images and icons, enhancing your presentation’s visual appeal and uniqueness. You can also use an eye-catching presentation background to elevate your visual content.

- Incorporate impactful quotes or inspiring elements: Include powerful quotes or elements that resonate with your message, evoking emotions and leaving a lasting impression on your audience members

- Utilize data visualization for clarity: Present data and statistics effectively with Venngage’s charts, graphs and infographics, simplifying complex information for better comprehension.

Additionally, Venngage’s real-time collaboration tools allow you to seamlessly collaborate with team members to elevate your presentation creation process to a whole new level. Use comments and annotations to provide feedback on each other’s work and refine ideas as a group, ensuring a comprehensive and well-rounded presentation.

Well, there you have it—the secrets of how to conclude a presentation. From summarizing your key message to delivering a compelling call to action, you’re now armed with a toolkit of techniques that’ll leave your audience in awe.

Now go ahead, wrap it up like a pro and leave that lasting impression that sets you apart as a presenter who knows how to captivate, inspire and truly make a mark.

SpeakUp resources

How to end a presentation in english: methods and examples.

- By Matthew Jones

Naturally, the way you end a presentation will depend on the setting and subject matter. Are you pitching an idea to your boss? Are you participating in a group presentation at school? Or are you presenting a business idea to potential investors? No matter the context, you’ll want to have a stellar ending that satisfies your audience and reinforces your goals.

So, do you want to learn how to end a presentation with style? Wondering how to end an informative speech? Or do you want to know how to conclude a Powerpoint presentation with impact? We’re here to help you learn how to end a presentation and make a great impression!

How to End a Presentation: 3 Effective Methods

Every presentation needs a great beginning, middle, and end. In this guide, we will focus on crafting the perfect conclusion. However, if you’d like to make sure that your presentation sounds good from start to finish, you should also check out our guide on starting a presentation in English .

Though there are many ways to end a presentation, the most effective strategies focus on making a lasting impression on your audience and reinforcing your goals. So, let’s take a look at three effective ways to end a presentation:

1. Summarize the Key Takeaways

Most presenters either make an argument (i.e. they want to convince their audience to adopt their view) or present new or interesting information (i.e. they want to educate their audience). In either case, the presentation will likely consist of important facts and figures. The conclusion gives you the opportunity to reiterate the most important information to your audience.

This doesn’t mean that you should simply restate everything from your presentation a second time. Instead, you should identify the most important parts of your presentation and briefly summarize them.

This is similar to what you might find in the last paragraph of an academic essay. For example, if you’re presenting a business proposal to potential investors, you might conclude with a summary of your business and the reasons why your audience should invest in your idea.

2. End with a CTA (Call-To-Action)

Ending with a Call-To-Action is one of the best ways to increase audience engagement (participation) with your presentation. A CTA is simply a request or invitation to perform a specific action. This technique is frequently used in sales or marketing presentations, though it can be used in many different situations.

For example, let’s say that you’re giving an informational presentation about the importance of hygiene in the workplace. Since your goal is to educate your audience, you may think that there’s no place for a CTA.

On the contrary, informational presentations are perfect for CTA’s. Rather than simply ending your presentation, you can direct your audience to seek out more information on the subject from authorities. In this case, you might encourage listeners to learn more from an authoritative medical organization, like the World Health Organization (WHO).

3. Use a Relevant Quote

It may sound cliche, but using quotes in your closing speech is both memorable and effective. However, not just any quote will do. You should always make sure that your quote is relevant to the topic. If you’re making an argument, you might want to include a quote that either directly or indirectly reinforces your main point.

Let’s say that you’re conducting a presentation about your company’s mission statement. You might present the information with a Powerpoint presentation, in which case your last slide could include an inspirational quote. The quote can either refer to the mission statement or somehow reinforce the ideas covered in the presentation.

Formatting Your Conclusion

While these 3 strategies should give you some inspiration, they won’t help you format your conclusion. You might know that you want to end your presentation with a Call-To-Action, but how should you “start” your conclusion? How long should you make your conclusion? Finally, what are some good phrases to use for ending a presentation?<br>

Examples of a Good Conclusion

In conclusion, I believe that we can increase our annual revenue this year. We can do this with a combination of increased efficiency in our production process and a more dynamic approach to lead generation. If we implement these changes, I estimate that annual revenue will increase by as much as 15%.

The example above shows a good conclusion for a business presentation. However, some people believe that the term in conclusion is overused. Here’s how to end a presentation using transition words similar to in conclusion .

Transition words help your audience know that your presentation is ending. Try starting your conclusion with one of these phrases:

- To summarize

However, transition words aren’t always necessary. Here are a few good ways to end a presentation using a different approach.

- Summarize Key Takeaways : There are two things that I’d like you to remember from today’s presentation. First, we are a company that consults startups for a fraction of the cost of other consultation services. And second, we have a perfect record of successfully growing startups in a wide variety of industries. If anything was unclear, I’d be happy to open the floor to questions.

- Make a Call-To-Action : I am very passionate about climate change. The future of the planet rests on our shoulders and we are quickly running out of time to take action. That said, I do believe that we can effect real change for future generations. I challenge you to take up the fight for our children and our children’s children.

- Use a Relevant Quote: I’d like to end my presentation with one of my favorite quotes: “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.”

As you can see, your conclusion does not need to be very long. In fact, a conclusion should be short and to the point. This way, you can effectively end your presentation without rambling or adding extraneous (irrelevant) information.

How to End a Presentation in English with Common Phrases

Finally, there are a few generic phrases that people frequently use to wrap up presentations. While we encourage you to think about how to end a presentation using a unique final statement, there’s nothing wrong with using these common closing phrases:

- Thank you for your time.

- I appreciate the opportunity to speak with you today.

- I’ll now answer any questions you have about (topic).

- If you need any further information, feel free to contact me at (contact information).

We hope this guide helps you better understand how to end a presentation ! If you’d like to find out more about how to end a presentation in English effectively, visit Magoosh Speaking today!

Matthew Jones

Free practice (Facebook group)

Phone: +1 (510) 560-7571

Terms of Use

Privacy Policy

Company Home

Home Blog Presentation Ideas Key Insights on How To End a Presentation Effectively

Key Insights on How To End a Presentation Effectively

A piece of research by Ipsos Corporate Firm titled “Last Impressions Also Count” argues that “our memories can be governed more by how an experience ends than how it begins .” A lasting final impression can be critical to any presentation, especially as it makes our presentation goals more attainable. We’re covering how to end a presentation , as it can certainly come through as an earned skill or a craft tailored with years of experience. Yet, we can also argue that performing exceptionally in a presentation is conducting the proper research. So, here’s vital information to help out with the task.

This article goes over popular presentation types; it gives suggestions, defines the benefits and examples of different speech closing approaches, and lines all this information up following each presentation purpose.

We also included references to industry leaders towards the end, hoping a few real-life examples can help you gain valuable insight. Learn from noted speakers and consultants as you resort to SlideModel’s latest presentation templates for your efforts. We’re working together on more successful presentation endings that make a difference!

Table of Content

A presentation’s end is not a recap

The benefits of ending a presentation uniquely, the power of closing in persuasive presentations, informative presentations: the kind set out to convey, call to action presentations: trigger actions or kickoff initiatives, a final word on cta presentations, real-life examples of how to end a presentation, succeeding with an effective presentation’s ending.

We need to debunk a widespread myth to start. That’s why the ending of the presentation calls for an appealing action or content beyond just restating information that the speaker already provided.

A presentation’s end is not a summary of data already given to our audience. On the contrary, a wrap-up is a perfect time to provide meaningful and valuable facts that trigger the desired response we seek from our audience. Just as important as knowing how to start a presentation , your skills on how to end a PowerPoint presentation will make a difference in the presentation’s performance.

Effective ways to end a presentation stem from truly seeking to accomplish – and excel – at reaching a presentation’s primary objective. And what are the benefits of that?

Considering the benefits of each closing approach, think about the great satisfaction that comes from giving an excellent presentation that ends well. We all intuitively rejoice in that success, regardless of the kind of audience we face.

That feeling of achievement, when an ending feels right, is not a minor element, and it’s the engine that should drive our best efforts forward. Going for the most recommended way of ending a presentation according to its primary goal and presentation type is one way to ensure we achieve our purpose.

The main benefit of cleverly unlocking the secret to presentation success is getting the ball rolling on what we set ourselves to achieve . Whether that’s securing a funding round, delivering a final project, presenting a quarterly business review, or other goals; there is no possible way in which handling the best presentation-ending approaches fails to add to making a skilled presenter, improving a brand or business, or positively stirring any academic or commercial context.

The best part of mastering these skills is the ability to benefit from all of the above time and time again; for any project, idea, or need moving forward.

How to end a PowerPoint Presentation?

PowerPoint Presentations differ by dimensions. They vary not only tied to the diverse reasons people present, but they also separate themselves from one another according to: a- use, b- context, c- industry, and d- purpose.

We’re focusing on three different types of presentation pillars, which are:

- Informative

- Calls to action

As you can guess, the speaker’s intent varies throughout these types. Yet, there’s much more to each! Let’s go over each type’s diverse options with examples.

In 2009, “The New Rules of Persuasion,” a journal article published by The Royal Society for Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce, determined that commercial persuasion was missing “the ability to think clearly about behavior goals and the mindset of starting small and growing what works.” Incorporating these thoughts is still equally valid in persuasive presentations today.

What hasn’t changed since, however, is this society’s good reminder that “the potential to persuade is in the hands of millions.” As they stated in that publication, “ordinary people sitting in dorm rooms and garages can compete against the biggest brands and the richest companies.” The proven reality behind that concept can be pretty inspiring.

According to this source, “ the first critical step in designing for persuasion is to select an appropriate target behavior. ” And, for behavior to occur, in their opinion, “three elements must converge at the same moment […]: Motivation , Ability, and Trigger .” This theory signals a person is motivated through sensation, anticipation, or belonging when they can perform a particular action. This concept is at the backbone of setting the correct trigger to allow a group of people to react a certain way.

The above is of utmost importance as we seek to gear persuasive efforts. The more insight we get on the matter, the easier it is to define the precise actions that will effectively trigger a certainly required response – in any scenario.

Here are options on how to deliver a final punch in a persuasive presentation during different types of objectives:

Investment presentations

Whenever you seek funding, that need should be expressly clear during a pitch. Investors need to know what’s in it for them on a given investment. Highlight what interests them, and add what the return for the investor is. Mention dividends, equity, or the return method selected, for instance. Your final ask slide should show the exact amount you’re looking for during this funding stage.

Throughout, explain what an investor’s return on investment (ROI) will be. And make sure you do so according to provable calculations. Here, the goal is to display current figures and future opportunities in your speech.

You mustn’t make up this data. In this setting, presenters are naturally assessed by their ability to stay within real options fully supported by proven and concise reliable information.

Focus on showing an ability to execute and accomplish expected growth. Also, be precise on how you’re using any trusted funds . For that, mention where they’ll be allocated and how you foresee revenue after investing the funds in your idea, product, or company.

Pitch Presentations

Pitches are also another form of persuasive presentation. Presenters are expected to wow in new ways with them, be engaging in their approach, and deliver valuable, market-impacting data. When someone delivers a pitch, it seeks a particular kind of action in return from the audience. Being fully engaged towards a presentation’s end is crucial.

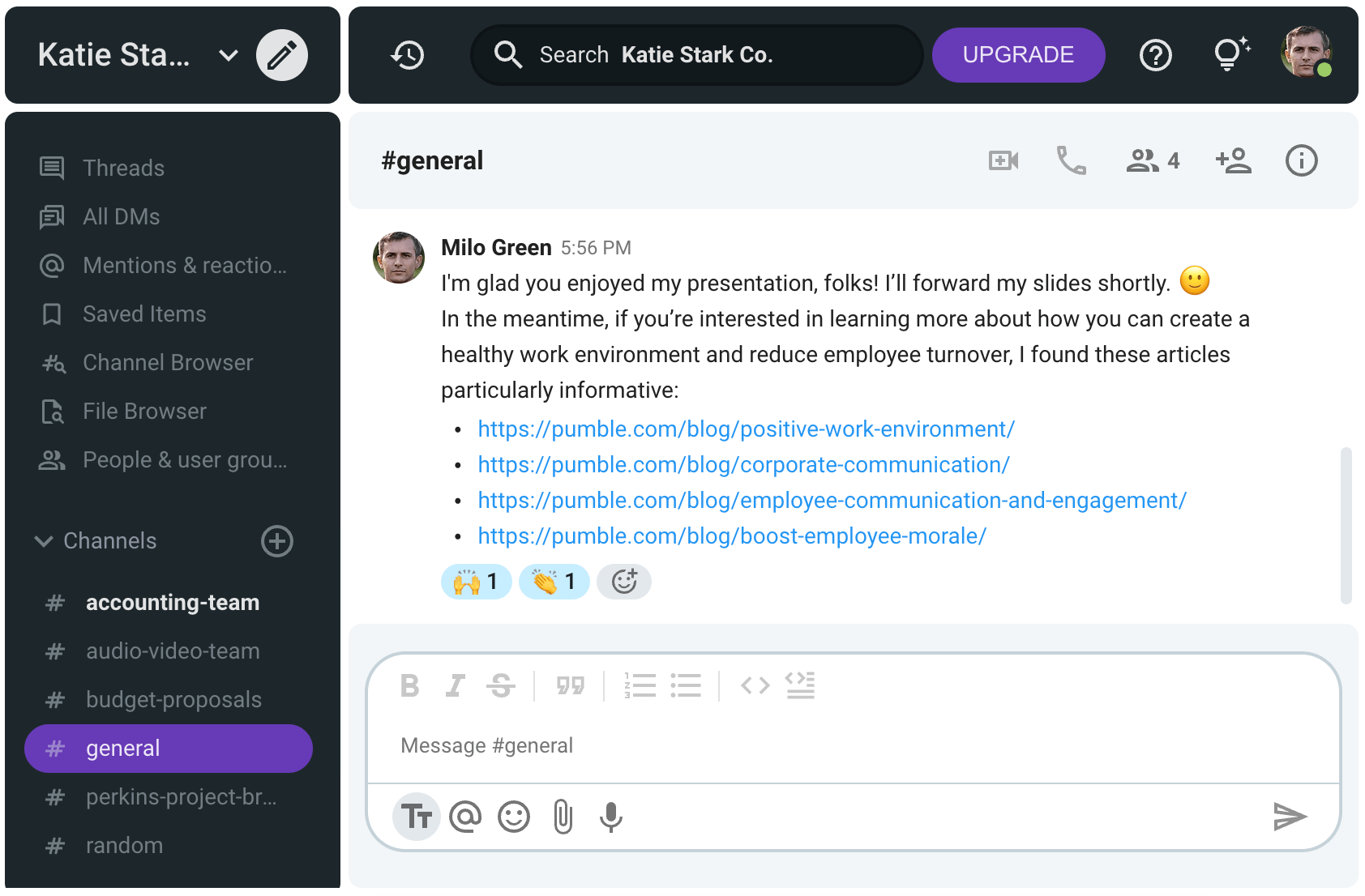

Make sure you give the presentation’s end a Call to Action slide in sales. You’re certainly looking to maximize conversion rates here. Bluntly invite your audience to purchase the product or service you’re selling, and doing so is fair in this context. For example, you can add a QR code or even include an old-fashioned Contact Us button. To generate the QR code, you can use a QR code generator .

According to Sage Publishing , there are “four types of informative speeches[, which] are definition speeches, demonstration speeches, explanatory speeches, and descriptive speeches.” In business, descriptive speeches are the most common. When we transport these more specifically to the art of presenting, we can think of project presentations, quarterly business reviews, and product launches. In education, the definition and demonstration speeches are the norm, we can think in lectures and research presentations respectively.

As their name suggests, these presentations are meant to inform our audiences of specific content. Or, as SAGE Flex for Public Speaking puts it in a document about these kinds of speeches, “the speaker’s general goal is always to inform—or teach—the audience by offering interesting information about a topic in a way that helps the audience remember what they’ve heard.” Remember that as much as possible, you’re looking to, in Sage’s words, give out “information about a topic in a way that’s easy to understand and memorable.” Let’s see how we manage that in the most common informative presentation scenarios mentioned above.

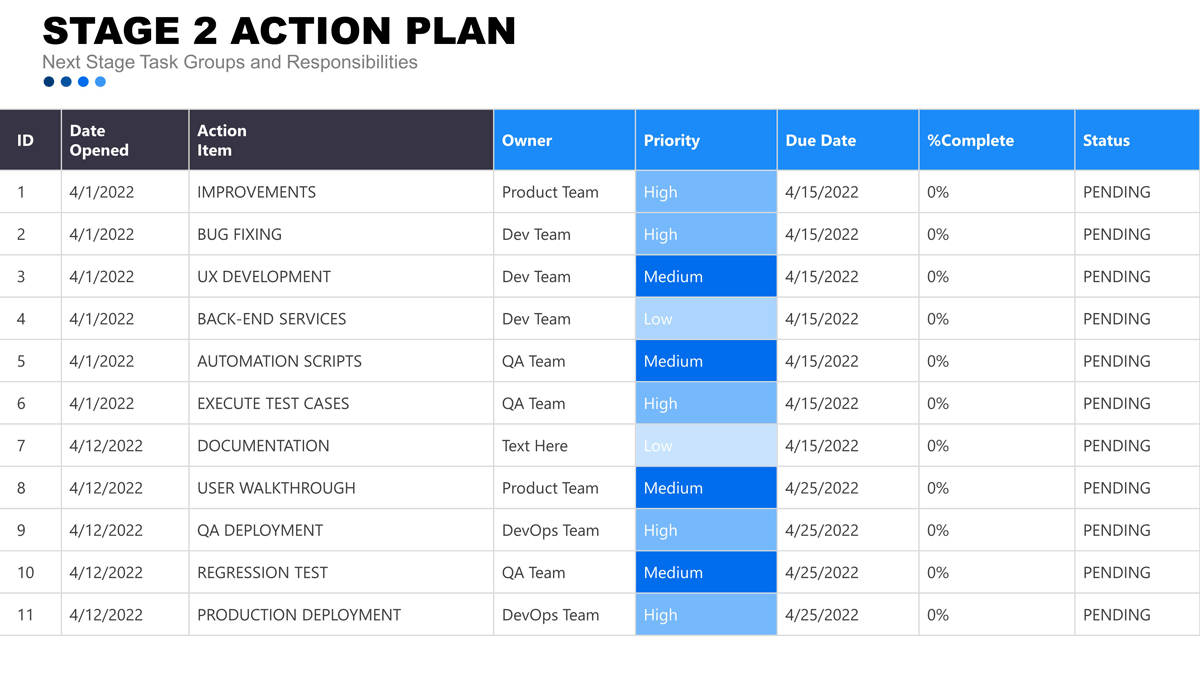

Project Presentations

For projects, presentations should end with an action plan . Ensure the project can keep moving forward after the presentation. The best with these conclusion slides is to define who is responsible for which tasks and the expected date of completion. Aim to do so clearly, so that there are no remaining doubts about stakeholders and duties when the presentation ends. In other words, seek commitment from the team, before stepping out of these meetings. It should be clear to your audience what’s expected next of them.

As an addition, sum up, your problem, solution, and benefits of this project as part of your final message.

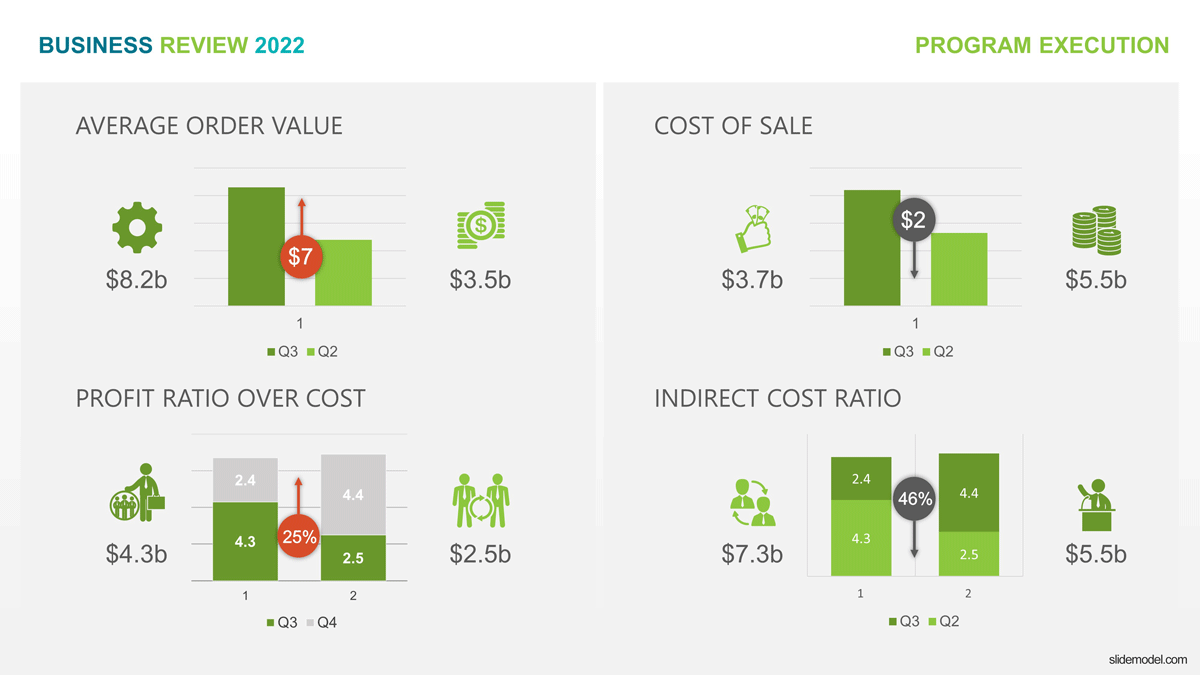

Quarterly Business Review Presentations (QBR)

By the end of the presentation type, you would’ve naturally gone over everything that happened during a specific quarter. Therefore, make sure you end this quarterly review with clear objectives on what’s to come for the following term. Be specific on what’s to come.

In doing so, set figures you hope to reach. Give out numbers and be precise in this practice. Having a clear action plan to address new or continuing goals is crucial in this aspect for a recent quarter’s start out of your QBR. Otherwise, we’re missing out on a true QBR’s purpose. According to Gainsight , “If you go into a QBR without a concrete set of goals and a pathway to achieve them, you’ll only waste everyone’s time. You won’t improve the value of your product or services for your customers. You won’t bolster your company’s image in the eyes of key stakeholders and decision-makers. You won’t better understand your client’s business objectives.” As they put it, “Lock in solid goals for the next quarter (or until your next QBR)” and secure your way forward as the last step in presenting these kinds of data. Visit our guide on How to Write an Effective Quarterly Business Review for further tips on this type of presentation.

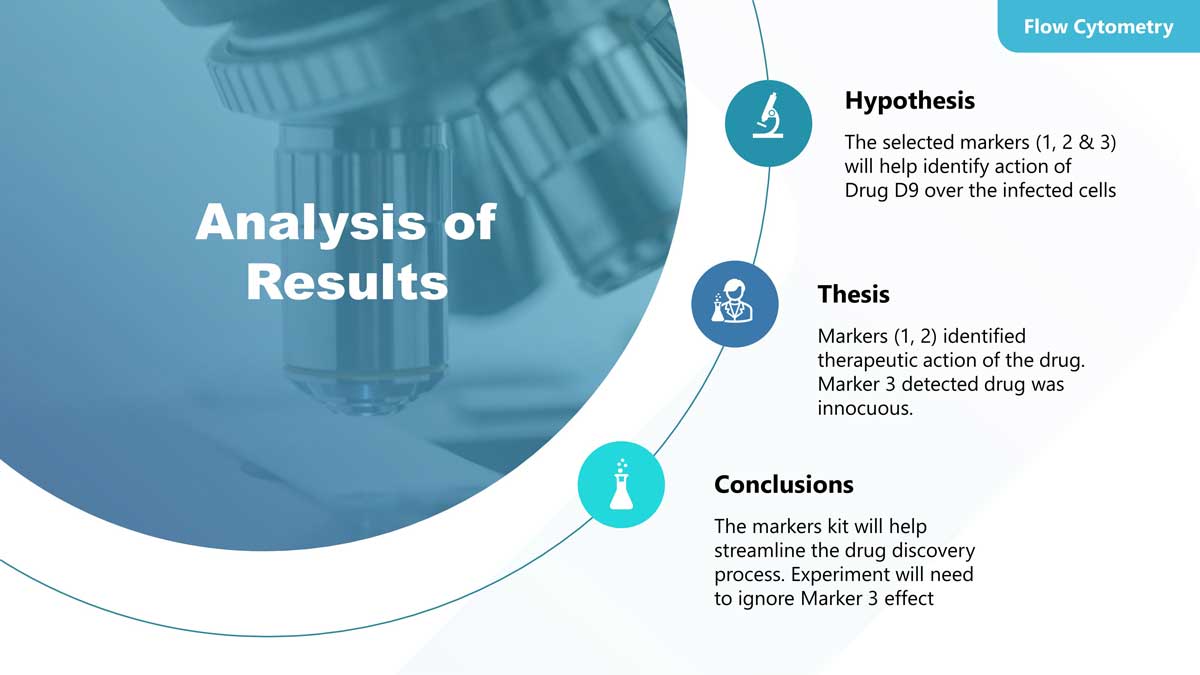

Research presentations

Your research has come this far! It’s time to close it off with an executive summary.

Include the hypothesis, thesis, and conclusion towards the presentation’s end.

How do you get the audience to recall the main points of all this work? Let this guiding question answer what to insert in your final slide, but seek to reinforce your main findings, key concepts, or valuable insight as much as possible. Support your statements where necessary.

Most commonly, researchers end with credits to the collaborating teams. Consider your main messages for the audience to take home. And tie those with the hypothesis as much as possible.

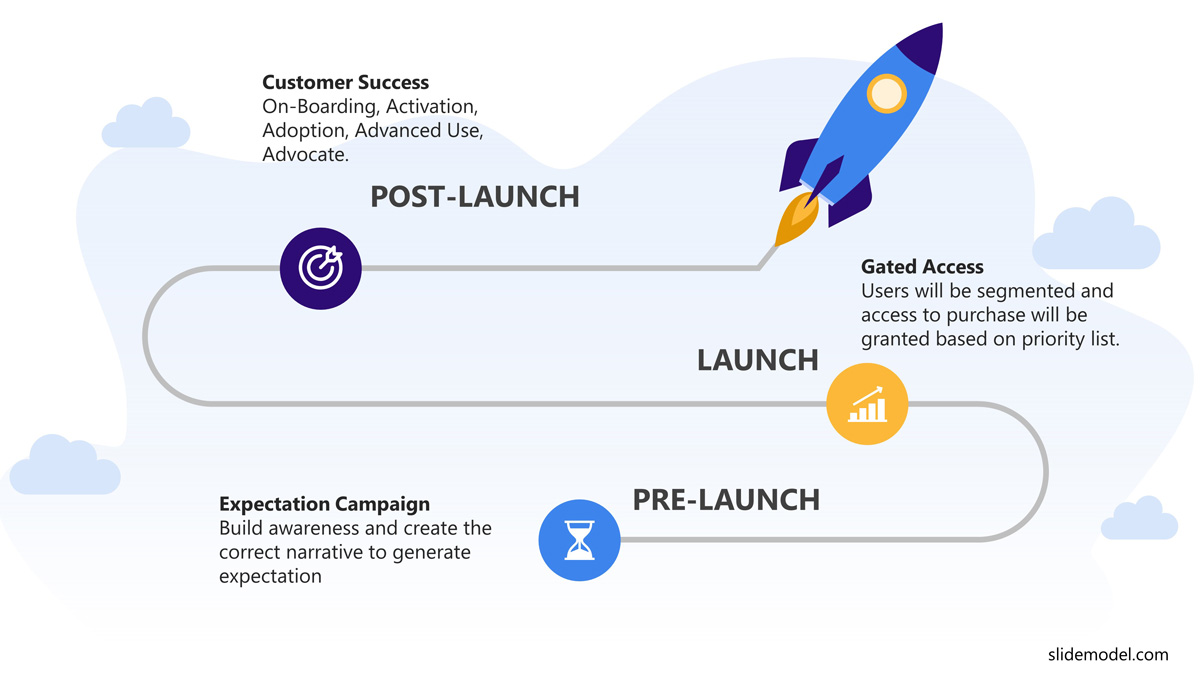

Product Launch Presentation

Quite simply, please take out the product launch’s roadmap and make it visible for your presentation’s end in this case.

It’s ideal for product launch presentations to stir conversations that get a product moving. Please don’t stick to showcasing the product, but build a narrative around it.

Steve Jobs’ example at the bottom might help guide you with ideas on how to go around this. A key factor is how Apple presentations were based on a precise mix of cutting-edge, revolutionary means of working with technology advancements and a simple human touch.

Elon Musk’s principles are similar. People’s ambitions and dreams are a natural part of that final invitation for consumers or viewers to take action. What will get your audience talking? Seek to make them react.

Lecture for specific classes / educational presentation

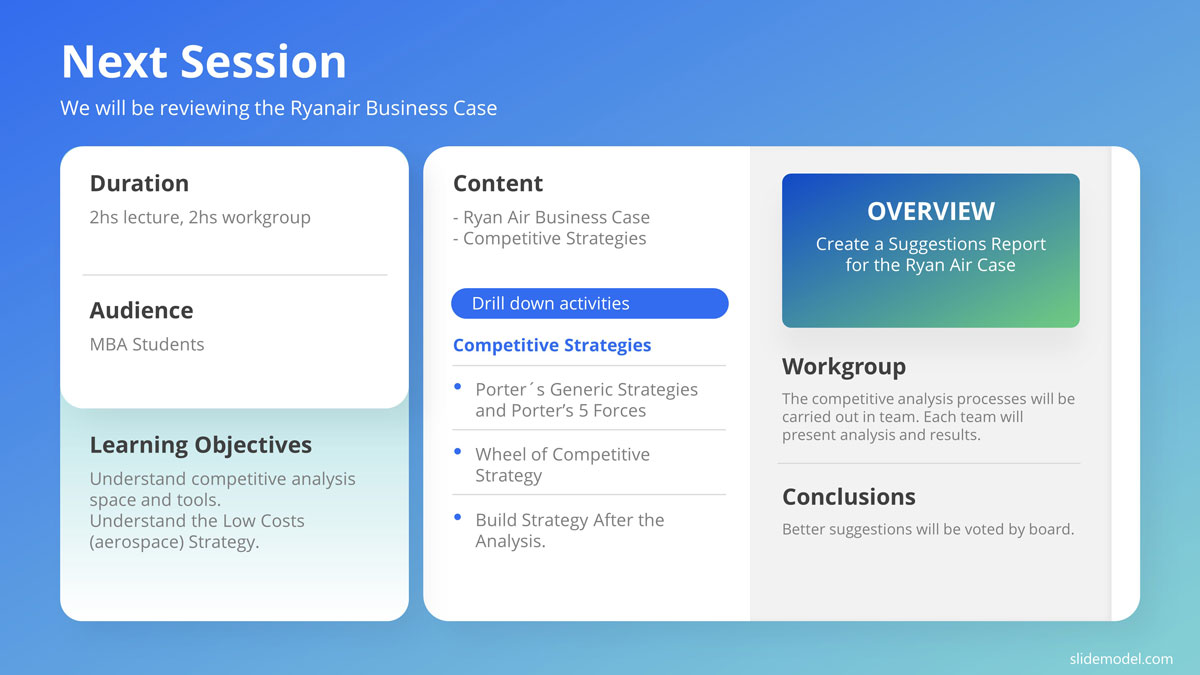

When it comes to academic settings, it’s helpful to summarize key points of a presentation while leaving room for questions and answers.

If you’re facing a periodic encounter in a class environment, let students know what’s coming for the next term. For instance, you could title that section “What’s coming next class,” or be creative about how you call for your student body’s attention every time you go over pending items.

If you need to leave homework, list what tasks need to be completed by the audience for the next class.

Another option is to jot down the main learnings from this session or inspire students to come back for the following class with a list of exciting topics. There’s more room for play in this setting than in the others we’ve described thus far.

Harvard Business Review (HBR) concisely describes the need at the end of a call to action presentation. HBR’s direct piece of advice is that you should “use the last few moments of your presentation to clarify what action [an audience] can take to show their support.” And what’s key to HBR is that you “Also mention your timeframe” as, for them, “a deadline can help to urge [the audience] into action.” Having a clear view of specific timelines is always fruitful for a better grasp of action items.

In her book Resonate, Nancy Duarte explains that “No matter how engaging your presentation may be, no audience will act unless you describe a reward that makes it worthwhile. You must clearly articulate the ultimate gain for the audience […] If your call to action asks them to sacrifice their time, money, or ideals, you must be very clear about the payoff.”

Business plan presentations

Here, we need to speak of two different presentation types, one is a traditional approach , and the second is what we call a lean approach .

For the traditional business plan presentation, display each internal area call to action. Think of Marketing, Operations, HR, and even budgets as you do so. Your PowerPoint end slide should include the rewards for each of the areas. For example, which will benefit each area when achieving the targets, or how will the company reward its employees when attaining specific goals? Communicating the reward will help each of the responsible entities to trigger action.

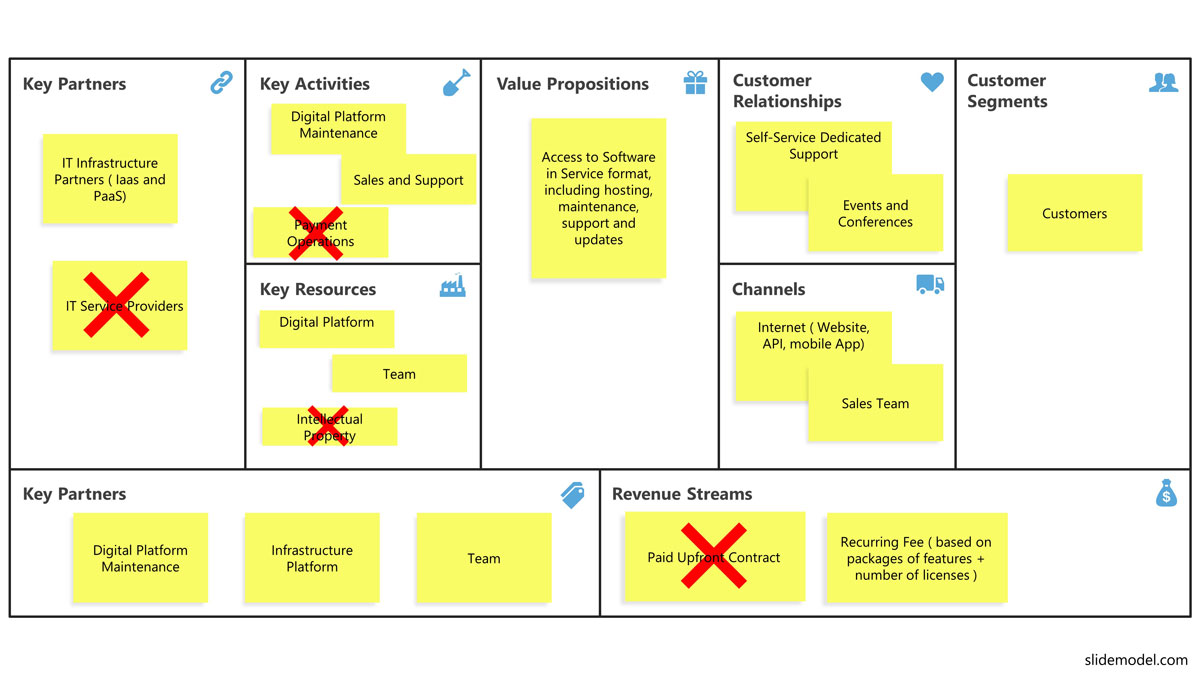

On the other hand, for your lean business plan, consider a business model canvas to bring your presentation to an end.

Job interview presentations

You can undoubtedly feel tons of pressure asking for a specific position. For a great chance of getting that new job, consider closing your case with a 30 60 90 day plan as a particular hiring date. The employer will see its reward in each of the 30-day milestones.

Also, show off what you’ll bring to the role and how you’ll benefit the company in that period, specifically. Again, to a certain extent, we’re seeking to impress by being offered a position. Your differentiator can help as a wrap-up statement in this case.

Business Model Presentation

The pivot business model fits perfectly here for a presentation’s grand finale. The reward is simple; the business validated a hypothesis, and a new approach has been defined.

Though the setting can be stressful around business model presentations, you can see this as simply letting executives know what the following line of steps will need to be for the business model to be scalable and viable. Take some tension off this purpose by focusing on actions needed moving forward.

Your call to action will center around a clear business model canvas pivot here.

We need to work hard at ending presentations with clear and concise calls to action (CTA) and dare be creative as we’re doing so! Suppose you can manage to give out a specific CTA in a way that’s imaginative, appealing, and even innovative. In that case, you’ll be showing off priceless and unique creative skills that get people talking for years!

Think of Bill Gates’ releasing mosquitoes in a TED Talk on malaria, for example. He went that far to get his CTA across. Maybe that’s a bit too bold, but there’s also no limit!

Now that we can rely on a broader understanding of how to conclude a presentation successfully, we’ll top this summary off with real-life examples of great endings to famous speakers’ presentations. These people have done a stellar job at ending their presentations in every case.

We’re also going back to our three main pillars to focus on a practical example for each. You’ll find an excellent example for an informative speech, a persuasive pitch, and a successful investor pitch deck. We’re also expanding on the last item for a guiding idea on ending a pitch directly from Reid Hoffman.

Informational Presentation: A product launch of a phone reinvention

The first is what’s been titled “the best product launch ever.” We’re going back to the iconic Steve Jobs’ iPhone launch dated more than a decade ago. You can see how to end a presentation with a quote in this example effectively. The quote resonates with the whole presentation purpose, which was not “selling” the iPhone as a “hardware phone” but as the “hardware” platform for “great software.” Closing with a quote from a famous personality that summarizes the idea was a clever move.

Little words are needed to introduce Steve Jobs as a great speaker who effectively moved the business forward every time he went up on a stage to present a new product. No one has ever been so revolutionary with a calm business spirit that has changed the world!

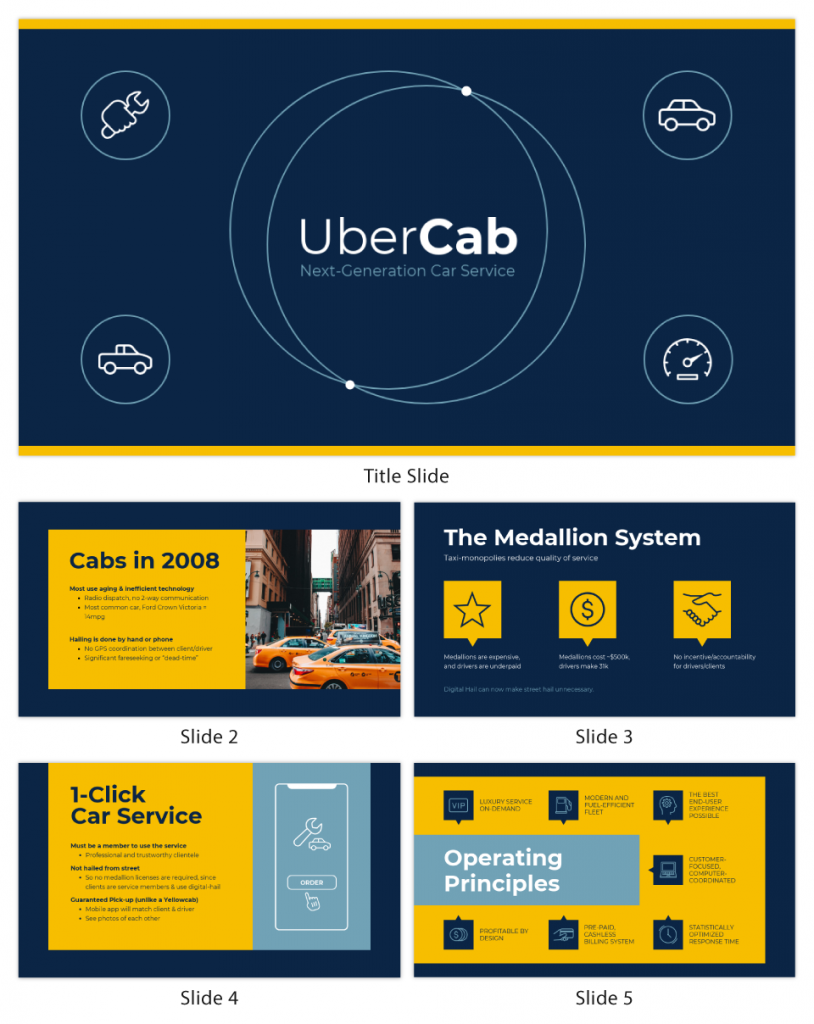

Persuasive Presentation: The best pitch deck ever

We’re giving you the perfect example of a great pitch deck for a persuasive kind of presentation.

Here’s TechCrunch’s gallery on Uber’s first pitch deck .

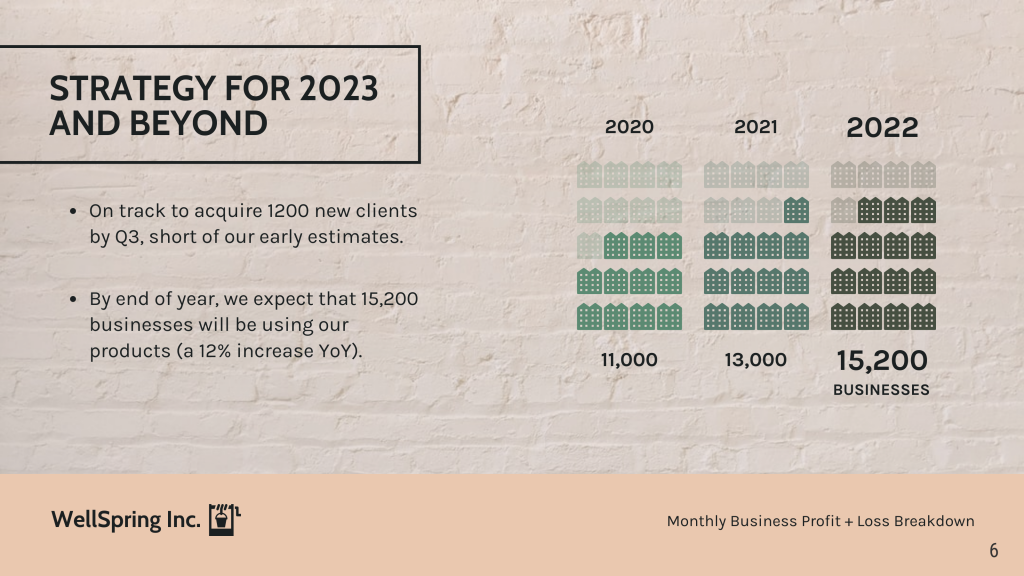

As you can see, the last slide doesn’t just report the status to date on their services; it also accounts for the following steps moving forward with a precise date scheduled.

Check the deck out for a clearer idea of wrapping up a persuasive business presentation.

Call to Action Presentation: LinkedIn’s Series B pitch deck by Reid Hoffman

As mentioned before, here’s an expanded final sendoff! Reid Hoffman is an established entrepreneur. As a venture capitalist and author, he’s earned quite a remarkable record in his career, acting as co-founder and executive chairman of LinkedIn.

We’re highlighting LinkedIn’s series B pitch deck to Greylock Partners mainly because these slides managed to raise a $10 M funding round. Yet, moreover, we’re doing so because this deck is known to be well-rounded and overall highly successful.

LinkedIn may be famous now for what it does, but back in 2004, when this deck made a difference, the company wasn’t a leader in a market with lots of attention. As Reid highlights on his website, they had no substantial organic growth or revenue. Yet, they still managed to raise a considerable amount.

In Reid’s words for his last slide, “The reason we reused this slide from the beginning of the presentation was to indicate the end of presentation while returning to the high line of conceptualizing the business and reminding investors of the value proposition.” In his vision, “You should end on a slide that you want people to be paying attention to,” which he has tied with the recommendation that you “close with your investment thesis,” as well. A final note from him on this last slide of LinkedIn’s winning pitch is that “the end is when you should return to the most fundamental topic to discuss with your investors.” Quite a wrap-up from a stellar VC! Follow the linked site above to read more on the rest of his ending slides if you haven’t ever done so already.

The suggestions above are practical and proven ways to end a presentation effectively. Yet, remember, the real secret is knowing your audience so well you’ll learn how to grasp their attention for your production in the first place.

Focus on the bigger picture and add content to your conclusion slide that’s cohesive to your entire presentation. And then aim to make a lasting final impression that will secure what you need. There is a myriad of ways to achieve that and seek the perfect-suiting one.

Also, be bold if the area calls for it. As you see above, there is no shame, but an actual need to state the precise funding amount you need to make it through a specific stage of funding. Exercise whatever tools you have at your disposal to get the required attention.

Also, being sure about whatever decision you make will only make this an easier road to travel. If your head is transparent about what’s needed, you’ll be more confident to make a convincing case that points your audience in the right direction.

Check out our step-by-step guide on how to make a presentation .

Like this article? Please share

Business, Business Development, Business PowerPoint Templates, Business Presentations, Corporate Presentations, PowerPoint Tips, Presentation Approaches Filed under Presentation Ideas

Related Articles

Filed under Design • March 27th, 2024

How to Make a Presentation Graph

Detailed step-by-step instructions to master the art of how to make a presentation graph in PowerPoint and Google Slides. Check it out!

Filed under PowerPoint Tutorials • March 26th, 2024

How to Translate in PowerPoint

Unlock the experience of PowerPoint translation! Learn methods, tools, and expert tips for smooth Spanish conversions. Make your presentations global.

Filed under PowerPoint Tutorials • March 19th, 2024

How to Change Line Spacing in PowerPoint

Adjust text formatting by learning how to change line spacing in PowerPoint. Instructions for paragraph indenting included.

Leave a Reply

How to End a Presentation The Right Way (+ 3 Downloadable Creative PowerPoint Conclusion Slides)

Ausbert Generoso

Ever been in a presentation that started strong but fizzled out at the end? It’s a common frustration. The conclusion is where your message either sticks or fades away.

But how often have you left a presentation wondering, “Was that it?” A lackluster ending can undermine the impact of an entire presentation. In the digital age, a strong conclusion isn’t just a courtesy; it’s your secret weapon to make your message unforgettable.

In this blog, we’re diving into the art of crafting a powerful ending, making sure your audience doesn’t just understand but gets inspired. Let’s explore the key on how to end a presentation in a way that lingers in your audience’s minds.

Table of Contents

Why having a good presentation conclusion matters.

Understanding why a conclusion is not merely a formality but a critical component is key to elevating your presentation game. Let’s delve into the pivotal reasons why a well-crafted conclusion matters:

🎉 Lasting Impression

The conclusion is the last note your audience hears, leaving a lasting impression. It shapes their overall perception and ensures they vividly remember your key points.

🔄 Message Reinforcement

Think of the conclusion as the reinforcement stage for your central message. It’s the last opportunity to drive home your main ideas, ensuring they are understood and internalized.

📝 Audience Takeaways

Summarizing key points in the conclusion acts as a guide, ensuring your audience remembers the essential elements of your presentation.

💬 Connection and Engagement

A well-crafted conclusion fosters engagement, connecting with your audience on a deeper level through thought-provoking questions, compelling quotes, or visual recaps.

🚀 Motivation for Action

If your presentation includes a call to action, the conclusion plants the seeds for motivation, encouraging your audience to become active participants.

🌟 Professionalism and Polishing

A strong conclusion adds professionalism, showcasing attention to detail and a commitment to delivering a comprehensive and impactful message.

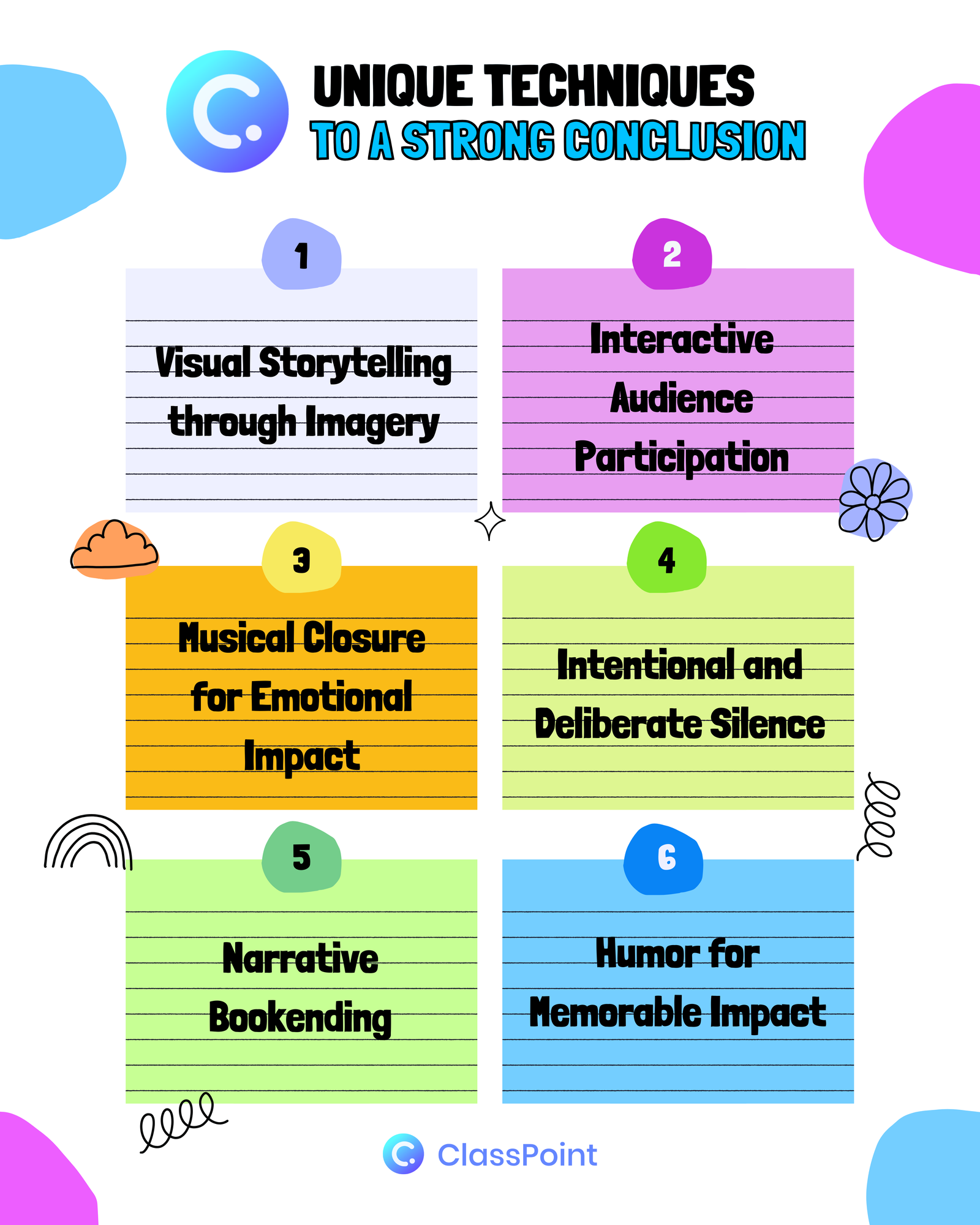

6 Unique Techniques and Components to a Strong Conclusion

As we navigate the art of how to end a presentation, it becomes evident that a powerful and memorable conclusion is not merely the culmination of your words—it’s an experience carefully crafted to resonate with your audience. In this section, we explore key components that transcend the ordinary, turning your conclusion into a compelling finale that lingers in the minds of your listeners.

1. Visual Storytelling through Imagery

What it is: In the digital age, visuals carry immense power. Utilize compelling imagery in your conclusion to create a visual story that reinforces your main points. Whether it’s a metaphorical image, a powerful photograph, or an infographic summarizing key ideas, visuals can enhance the emotional impact of your conclusion.

How to do it: Select images that align with your presentation theme and evoke the desired emotions. Integrate these visuals into your conclusion, allowing them to speak volumes. Ensure consistency in style and tone with the rest of your presentation, creating a seamless visual narrative that resonates with your audience.

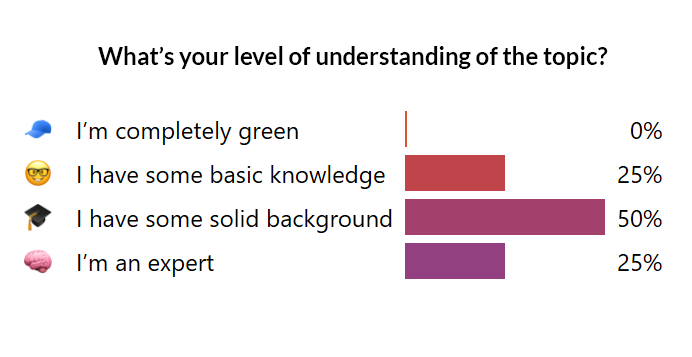

2. Interactive Audience Participation

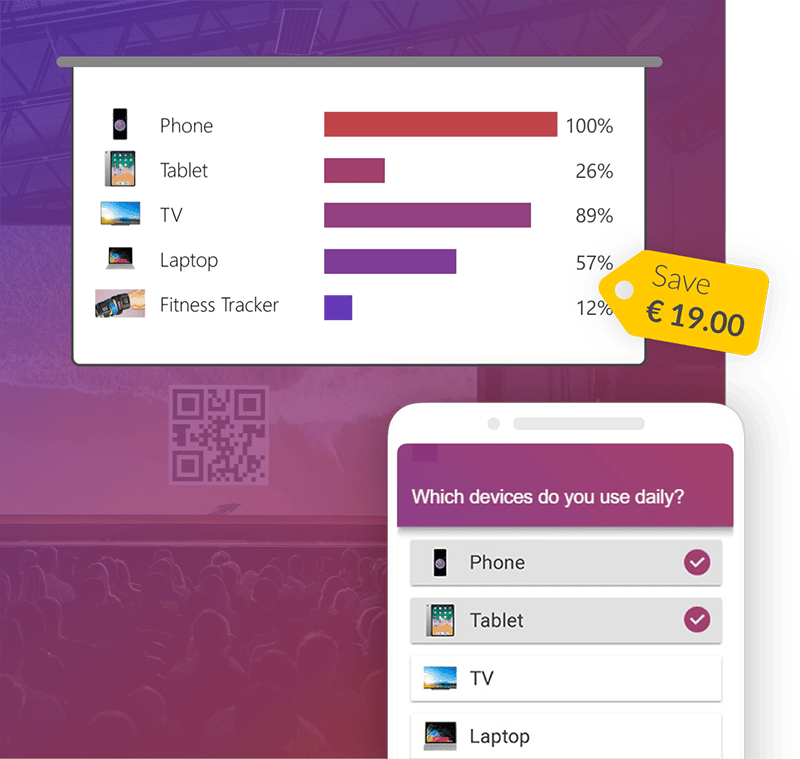

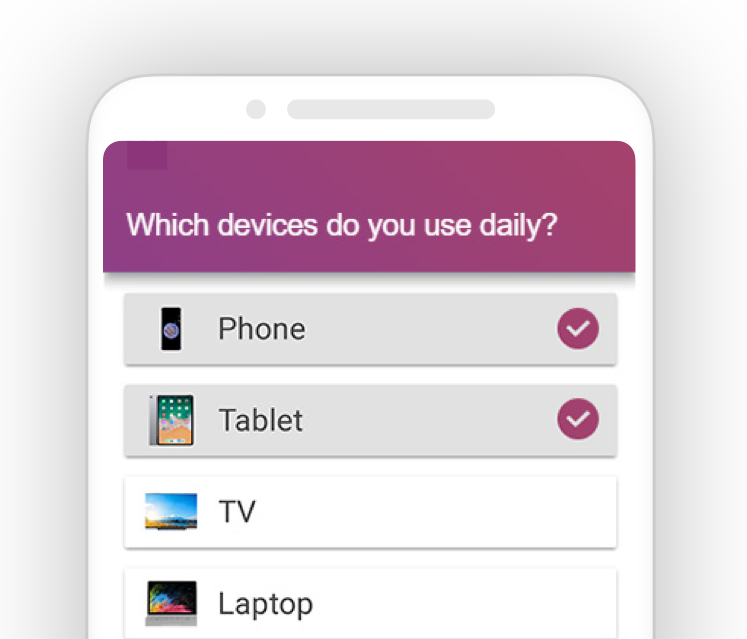

What it is: Transform your conclusion into an interactive experience by engaging your audience directly. Pose a thought-provoking question or conduct a quick poll related to your presentation theme. This fosters active participation, making your conclusion more memorable and involving your audience on a deeper level.

How to do it: Craft a question that encourages reflection and discussion. Use audience response tools, if available, to collect real-time feedback. Alternatively, encourage a show of hands or open the floor for brief comments. This direct engagement not only reinforces your message but also creates a dynamic and memorable conclusion.

3. Musical Closure for Emotional Impact

What it is: Consider incorporating music into your conclusion to evoke emotions and enhance the overall impact. A carefully selected piece of music can complement your message, creating a powerful and memorable ending that resonates with your audience on a sensory level.

How to do it: Choose a piece of music that aligns with the tone and message of your presentation. Introduce the music at the right moment in your conclusion, allowing it to play during the final thoughts. Ensure that the volume is appropriate and that the music enhances, rather than distracts from, your message.

4. Intentional and Deliberate Silence

What it is: Sometimes, the most impactful way to conclude a presentation is through intentional silence. A brief pause after delivering your final words allows your audience to absorb and reflect on your message. This minimalist approach can create a sense of gravity and emphasis.

How to do it: Plan a deliberate pause after your last sentence or key point. Use this moment to make eye contact with your audience, allowing your message to sink in. The strategic use of silence can be particularly effective when followed by a strong closing statement or visual element.

5. Narrative Bookending

What it is: Create a sense of completeness by bookending your presentation. Reference a story, quote, or anecdote from the introduction, bringing your presentation full circle. This technique provides a satisfying narrative structure and reinforces your core message.

How to do it: Identify a story or element from your introduction that aligns with your conclusion. Reintroduce it with a fresh perspective, revealing its relevance to the journey you’ve taken your audience on. This technique not only creates coherence but also leaves a lasting impression.

6. Incorporating Humor for Memorable Impact

What it is: Humor can be a powerful tool in leaving a positive and memorable impression. Consider injecting a well-timed joke, light-hearted anecdote, or amusing visual element into your conclusion. Humor can create a sense of camaraderie and connection with your audience.

How to do it: Choose humor that aligns with your audience’s sensibilities and the overall tone of your presentation. Ensure it enhances, rather than detracts from, your message. A genuine and well-placed moment of humor can humanize your presentation and make your conclusion more relatable.

[Bonus] Creative Ways on How to End a Presentation Like a Pro

1. minimalist conclusion table design.

One of the many ways to (aesthetically) end your PowerPoint presentation is by having a straightforward and neat-looking table to sum up all the important points you want your audience to reflect on. Putting closing information in one slide can get heavy, especially if there’s too much text included – as to why it’s important to go minimal on the visual side whenever you want to present a group of text.

Here’s how you can easily do it:

- Insert a table. Depending on the number of points you want to reinforce, feel free to customize the number of rows & columns you might need. Then, proceed to fill the table with your content.

- Clear the fill for the first column of the table by selecting the entire column. Then, go to the Table Design tab on your PowerPoint ribbon, click on the Shading drop down, and select No Fill.

- Color the rest of the columns as preferred. Ideally, the heading column must be in a darker shade compared to the cells below.

- Insert circles at the top left of each heading column. Each circle should be colored the same as the heading. Then, put a weighted outline and make it white, or the same color as the background.

- Finally, put icons on top each circle that represent the columns. You may find free stock PowerPoint icons by going to Insert, then Icons.

2. Animated Closing Text

Ever considered closing a presentation with what seems to be a blank slide which will then be slowly filled with text in a rather captivating animation? Well, that’s sounds specific, yes! But, it’s time for you take this hack as your next go-to in ending your presentations!

Here’s how simple it is to do it:

- Go to Pixabay , and set your search for only videos. In this example, I searched for the keyword, ‘yellow ink’.

- Insert the downloaded video onto a blank PowerPoint slide. Then, go to the Playback tab on the PowerPoint ribbon. Set the video to start automatically, and tick the box for ‘Loop until stopped’. Then, cover it whole with a shape.

- Place your closing text on top of the shape. It could be a quote, an excerpt, or just a message that you want to end your PowerPoint presentation with.

- Select the shape, hold Shift, and select the text next. Then, go to Merge Shapes, and select Subtract.

- Color the shape white with no outline. And, you’re done!

3. Animated 3D Models

What quicker way is there than using PowerPoint’s built-in 3D models? And did you know they have an entire collection of animated 3D models to save you time in setting up countless animations? Use it as part of your presentation conclusion and keep your audience’ eyes hooked onto the screens.

Here’s how you can do it:

- Design a closing slide. In this example, I’m using a simple “Thank You” slide.

- Go to Insert, then click on the 3D Models dropdown, and select Stock 3D Models. Here, you can browse thru the ‘All Animated Models’ pack and find the right model for you

- Once your chosen model has been inserted, go to the Animations tab.

- In this example, I’m setting a Swing animation. Then, set the model to start with previous.

- For a final touch, go to Animation Pane. From the side panel, click on the Effect Options dropdown and tick the check box for Auto-reverse. Another would be the Timing dropdown, then select Until End of Slide down the Repeat dropdown.

Get a hold of these 3 bonus conclusion slides for free!

Expert Tips on How to End a Presentation With Impact

🔍 Clarity and Conciseness

Tip: Keep your conclusion clear and concise. Avoid introducing new information, and instead, focus on summarizing key points and reinforcing your main message. A concise conclusion ensures that your audience retains the essential takeaways without feeling overwhelmed.

⏩ Maintain a Strong Pace

Tip: Control the pacing of your conclusion. Maintain a steady rhythm to sustain audience engagement. Avoid rushing through key points or lingering too long on any single aspect. A well-paced conclusion keeps your audience focused and attentive until the very end.

🚀 Emphasize Key Takeaways

Tip: Clearly highlight the most critical takeaways from your presentation. Reinforce these key points in your conclusion to emphasize their significance. This ensures that your audience leaves with a firm grasp of the essential messages you aimed to convey.

🔄 Align with Your Introduction

Tip: Create a sense of cohesion by aligning your conclusion with elements introduced in the beginning. Reference a story, quote, or theme from your introduction, providing a satisfying narrative arc. This connection enhances the overall impact and resonance of your presentation.

🎭 Practice, but Embrace Flexibility

Tip: Practice your conclusion to ensure a confident delivery. However, be prepared to adapt based on audience reactions or unexpected changes. Embrace flexibility to address any unforeseen circumstances while maintaining the overall integrity of your conclusion.

📢 End with a Strong Call to Action (if applicable)