Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

In Their Own Words, Americans Describe the Struggles and Silver Linings of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The outbreak has dramatically changed americans’ lives and relationships over the past year. we asked people to tell us about their experiences – good and bad – in living through this moment in history..

Pew Research Center has been asking survey questions over the past year about Americans’ views and reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic. In August, we gave the public a chance to tell us in their own words how the pandemic has affected them in their personal lives. We wanted to let them tell us how their lives have become more difficult or challenging, and we also asked about any unexpectedly positive events that might have happened during that time.

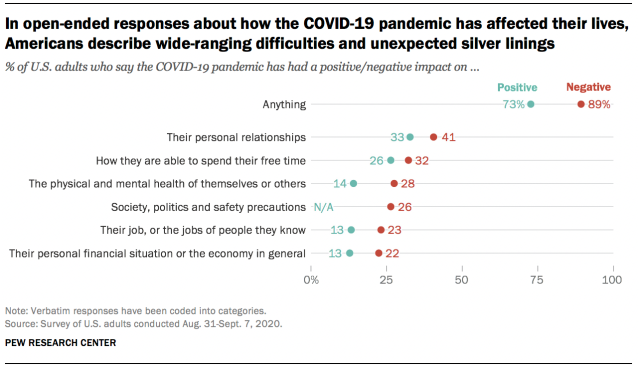

The vast majority of Americans (89%) mentioned at least one negative change in their own lives, while a smaller share (though still a 73% majority) mentioned at least one unexpected upside. Most have experienced these negative impacts and silver linings simultaneously: Two-thirds (67%) of Americans mentioned at least one negative and at least one positive change since the pandemic began.

For this analysis, we surveyed 9,220 U.S. adults between Aug. 31-Sept. 7, 2020. Everyone who completed the survey is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Respondents to the survey were asked to describe in their own words how their lives have been difficult or challenging since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, and to describe any positive aspects of the situation they have personally experienced as well. Overall, 84% of respondents provided an answer to one or both of the questions. The Center then categorized a random sample of 4,071 of their answers using a combination of in-house human coders, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service and keyword-based pattern matching. The full methodology and questions used in this analysis can be found here.

In many ways, the negatives clearly outweigh the positives – an unsurprising reaction to a pandemic that had killed more than 180,000 Americans at the time the survey was conducted. Across every major aspect of life mentioned in these responses, a larger share mentioned a negative impact than mentioned an unexpected upside. Americans also described the negative aspects of the pandemic in greater detail: On average, negative responses were longer than positive ones (27 vs. 19 words). But for all the difficulties and challenges of the pandemic, a majority of Americans were able to think of at least one silver lining.

Both the negative and positive impacts described in these responses cover many aspects of life, none of which were mentioned by a majority of Americans. Instead, the responses reveal a pandemic that has affected Americans’ lives in a variety of ways, of which there is no “typical” experience. Indeed, not all groups seem to have experienced the pandemic equally. For instance, younger and more educated Americans were more likely to mention silver linings, while women were more likely than men to mention challenges or difficulties.

Here are some direct quotes that reveal how Americans are processing the new reality that has upended life across the country.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

4 Ways That the Pandemic Changed How We See Ourselves

A fter more than two years of pandemic life , it seems like we’ve changed as people. But how? In the beginning, many wished for a return to normal, only to realize that this might never be possible—and that could be a good thing. Although we experienced the same global crisis, it has impacted people in extremely different ways and encouraged us to think more deeply about who we are and what we’re looking for.

Isolation tested our sense of identity because it limited our access to in-person social feedback. For decades, scientists have explored how “the self is a social product.” We interpret the world through social observation. In 1902, Charles Cooley invented the concept “the looking glass self.” It explains how we develop our identity based on how we believe other people see us, but also try to influence their perceptions , so they see us in the way we’d like to be seen. If we understand who we are based on social feedback, what happened to our sense of self under isolation?

Here are four ways that the pandemic changed how we see ourselves.

When lockdown started, our identities felt less stable, but we adjusted back over time

In crisis, our self-concept was challenged. A December 2020 study by Guido Alessandri and colleagues, which was published in Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research , measured how Italians reacted to the first week of the COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020 by evaluating how their self-concept clarity—the extent to which they have a consistent sense of self—affected their negative emotional response to the sudden lockdown.

Self-concept clarity represents “how much you have [clearly defined who you are] in your mind … not in this moment but in general,” explains Alessandri, a psychology professor at the Sapienza University of Rome. While generally people have high self-concept clarity, those with depression or personality disorders usually experience lower levels. “The lockdown threatened people’s self-concept. The very surprising result was that people with higher self-concept clarity [were] more reactive” and experienced a greater increase in negative affect than those with lower self-concept clarity.

In Alessandri’s study, people eventually returned to their initial stages of self-concept clarity, but it took longer than expected due to the shock and distress of the pandemic. This reflects a concept called emotional inertia , where emotional states are “resistant to change” and take some time to return to a baseline level. At the beginning of the pandemic, we questioned what we believed to be true about ourselves, but since then, we’ve adjusted to this new world.

Many people were forced to adopt new social roles, but the discomfort they felt depends on how important that role is to them

Our identities are not fixed; we hold several different social roles within our family, workplace, and friend groups, which naturally change over time. But in isolation, many of our social roles had to involuntarily change , from “parents homeschooling children [to] friends socializing online and employees working from home.”

As we adapted to a new way of life, a study published in September 2021 in PLOS One found that people who experienced involuntary social role disruptions because of COVID-19 reported increased feelings of inauthenticity—which could mean feeling disconnected from their true self because of their current situation. It was challenging for people to suddenly change their routines and feel like themselves in the midst of a crisis.

But the study also uncovered that “this social role interruption affects people’s sense of authenticity only to the extent that the role is important to you,” says co-author Jingshi (Joyce) Liu, a lecturer in marketing at the City campus of the University of London. If being a musician is central to your identity, for example, it’s more likely that you would feel inauthentic playing virtual shows on Zoom, but if your job isn’t a big part of who you are, you may not be as affected.

To feel more comfortable in their new identity, people can start accepting their new sense of self without trying to go back to who they once were

Over the last two years, our mindset and control over the roles we occupy in many facets of life helped determine how virtual learning and remote work affected us. “We are very sensitive to our environment,” Liu says. “[The] disruption of who we are will nonetheless feed into how we feel about our own authenticity.” But we can do our best to accept these changes and even form a new sense of self. “[If] I incorporated virtual teaching as a part of my self-identity, I [may not] need to change my behavior to go back to classroom teaching for me to feel authentic. I simply just adapt or expand the definition of what it means to be a teacher,” she adds. Similarly, if you’re a therapist, you can expand your understanding of what consulting with patients looks like to include video and phone calls.

During the pandemic, many people have made voluntary role changes, like choosing to become parents, move to a new city or country, or accept a new job. Previous research by Ibarra and Barbulescu (2010) shows that although these voluntary role changes may temporarily cause a sense of inauthenticity, they eventually tend to result in a feeling of authenticity because people are taking steps to be true to themselves or start a new chapter. “The authenticity will be restored as people adapt to their new identity,” Liu says.

Our identities have changed, so it’s important to be authentic with how we present ourselves online and offline

We have more power than we may realize to navigate a crisis by accepting that it’s OK to change. But it’s important to act in a way that’s true to ourselves. “People have a perception of the true self … They have some idea of who they truly are,” Liu says. “When you lend that to the [looking glass self], I think people would feel most inauthentic when they are performing to others in a way that is inconsistent with how they are [thinking and feeling internally],” which can happen on social media.

In isolation , when we didn’t have access to the same level of social feedback as normal, social media in some cases became a lifeline and a substitute for our self-presentation. The pandemic inspired people to take space away from the Internet and others to become increasingly dependent on it for their social wellbeing. “[Our unpublished data shows] that time spent on social media increased people’s sense of inauthenticity, perhaps because social media entails a lot of impression management [and] people are heavily editing themselves on these platforms,” Liu says.

With all that we’ve experienced, many of us have fundamentally changed as people. “In the same way which the first lockdown required us to [self-regulate] and adhere to new social norms, these changes that we’re experiencing now require another self-regulation effort to understand what is happening,” Alessandri says. “We don’t expect that people will simply get back to their previous [lives]—I don’t think this is possible. I think we have to negotiate a new kind of reality.”

The more we accept that we are no longer the same people after this crisis, the easier it will be for us to reconcile who we are now and who we want to become.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

A Year of Trauma and Resilience: How the Pandemic Changed Everything

New York Times readers describe the ways the pandemic first hit them and upended their lives, in their own words.

By Sarah Mervosh

It dawned on us when the grocery stores ran out of toilet paper.

When we lost work, risked our lives on the job or finally gave in and bought an office chair for home.

It dawned on us when we canceled long-dreamed-of weddings. When we graduated high school from our backyards, without a stage. When we gave birth — masked and alone.

It dawned on us when our aunts died and our children died and our parents died and we realized, with sudden, crushing clarity, that Covid-19 “was not going to be a disease that happened to ‘other people.’”

Across the United States and around the globe, nearly everyone experienced a moment when the coronavirus pandemic truly hit home for them. One year later, as the pandemic carries on, having claimed more than 2.6 million lives worldwide, we asked our readers : When did the pandemic become real for you? Nearly 2,000 people responded.

Their answers, which have been lightly edited and condensed for clarity, are a journey through time. It has been a year of trauma and resilience. No one has been spared, yet some have borne burdens far more profound than others.

Still, our stories connect us: each of us human, each of us just trying to survive a pandemic that changed us and the world.

A year ago…

everything changed.

Some changes were big.

Some subtle.

But for each of us, there was a moment when the pandemic became real.

When I asked a stranger on the street where she found the toilet paper she was carrying.

Heidi Fliegauf, 53, Boston

When my toddler grandson tried to feed me a blueberry through the cellphone screen.

Alice Gilgoff, 74, Rosendale, N.Y.

When I had no place other than a cemetery to take my child for fresh air and distance from people.

Ellie Dunn, 44, Queens, N.Y.

The night before my second round of chemo. I got a call saying my husband couldn’t attend because of new visitor restrictions.

Amelia Hartman, 34, Minneapolis

Seeing our county judge on TV with the governor. That’s when I knew things were going to change, especially in our small town.

Stevi Grose, 41, Cynthiana, Ky.

No more outings, meals, singing or games with Alzheimer’s clients. And no more paycheck. I started long-distance walking to ease anxiety and cope with loneliness and misplaced guilt.

Janice Randall, 64, Vashon Island, Wash.

Our favorite ice rink in Madrid being used as a morgue.

Joni Costello, 42, Madrid

When the food pantry I oversee saw an increase in need of more than 350 percent.

Natalie Nites, 26, Key Largo, Fla.

When I began wiping down everything in sight and wearing the same few outfits every single day.

Jolene Conder, 59, Brentwood, Calif.

I wrote my granddaughter a six-page letter reviewing our time together and what it meant to me in case I never saw her again.

Virginia Graves, 71, Rockport, Mass.

When I could no longer go over to my dad’s house. (My parents are divorced.)

Elizabeth Knight, 15, Clarksville, Tenn.

When they closed schools indefinitely. As a teacher, this was a really surreal experience.

Robin Freeman, 43, Marietta, Ga.

At every stage of life, milestones were upended.

First breaths…

final words…

and everything in between.

It was a year of togetherness.

And moments spent painfully apart.

Nothing during this entire pandemic felt so real as when I lay sobbing in my hospital bed not 24 hours after giving birth to my first child. My mother told me on the phone that the Canadian border agents were not letting her through the Toronto airport from the United States to come be with me.

Kelley Sykes, 27, Toronto

When we realized that we should go to the courthouse to get married on our lunch break because our wedding would be canceled and my then fiancée would lose her health insurance if she got furloughed.

Alex Herrin, 28, Nashville

My baby girl, Paloma, was born on March 11, 2020. Most of our family didn’t meet her in person.

Clary Montgomery, 33, Austin

When my college graduation was canceled. Like many first-generation college students, it was heartbreaking for me to accept that my parents would never get to see me walk across that stage after everything they have sacrificed for me.

Gabby Gil, 22, Charlotte, N.C.

We had to cancel our baby’s first birthday party.

Megan Denniston, 36, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Graduating from my backyard really drove the point home.

Julia Klopfer, 22, Boston

On a Saturday, we joyfully married — in an office, with just our parents. Seven days later, my grandma died without a funeral.

Emma Johnson, 26, St. Paul, Minn.

When my wife who had fought breast cancer for a year and beaten it contracted Covid at the end of August and then the cancer came back. She was gone by Sept. 14. Having lost the love of my life and best friend I have lost interest in everything.

Michael Boyajian, 62, Fishkill, N.Y.

My dad went into hospice care for renal failure. My husband and I became his de facto nurses. Dad died April 16. Just two of us could attend his graveside service.

Michael Hawkins, 63, Lake Oswego, Ore.

Few places were unchanged.

Our homes became crowded with work.

Millions of children were forced to learn online.

For many, a deep sense of emptiness remained.

When I was laid off from my job.

Jamie Harbeck, 38, Arlington, Va.

When I realized I became an unemployment statistic.

Amy Goggin, 41, Troy, N.Y.

When we had to lay off all our employees. No events meant no income. We drank Coronas. We laughed. We cried. We hoped this would not last too long. We have yet to be able to hire even half of them back.

Katwyn Liberti, 50, Orlando, Fla.

I moved to working remotely in our laundry room.

Brady Fopma, 42, Sioux Falls, S.D.

Taking calls from the bathtub to hide from my daughter.

Elis Hackmann Pereira, 35, Burlington, Ontario

The second I walked through the red door of my hospital’s Covid I.C.U. There were about 10 patients, and most were face down and already on continuous dialysis. The wind was knocked out of me. I didn’t know if it was due to the N95 mask or the gravity of the situation.

Mary Keckeisen, 24, Dallas

“Take home everything. Empty your lockers. You won’t be coming back.”

Max Kim, 16, Carmel, Ind.

I never graduated. I never went to senior prom. I hardly got to say goodbye to my best friends before going to college. Bye-bye, normalcy. And bye-bye, childhood and ignorant bliss.

Jess Sauer, 19, Kennett Square, Pa.

Never in my long life had my church been closed to me. I felt utterly abandoned even though I knew it was the right thing to do. This tile helped me survive the pandemic.

Lynn Hoins, 84, Riverton, Utah

When I noticed signs of emptiness outside in the world, whether it was the shelves at stores or a normally crowded train station with not a soul in sight.

Daya Devanathan, 30, Chicago

The silence. No car engines revving as neighbors headed for work. The absence of scraping scooters and giggles of kids as they walk the few blocks to our neighborhood school. The sounds marking the usual hustle and bustle of our daily lives were just gone.

Jennifer Jacoby, 68, Arlington, Mass.

The last night our grandkids spent here. I’ve lain on their beds crying more than once since then.

Stephanie Schuler, 64, Edmonds, Wash.

It was a year of heroism.

Resilience.

My son was born. We pulled my older son from school. Panic attacks daily in the shower. Postpartum anxiety engulfed my life.

Megan Leder, 35, Aurora, Colo.

As a recovering alcoholic, my husband was sober for about 10 months. In March, all group meetings were canceled. He held on for about a month and a half, but the isolation became too much to bear and we are back to suffering the effects of his alcoholism.

Kathy, 66, Florida

When my usually bright and sunny 10-year-old son started having panic attacks. Death is all around him and I can’t completely protect him. Ten is too young to come to the realization that one’s parents are fallible in this way.

Carey Sue Barney, 46, Winchester, Mass.

When I contracted Covid despite taking as many precautions as I could. I cried for the rest of the day. I felt so powerless.

Kelley Schlise, 20, Madison, Wis.

I spent a month recovering from horrendous symptoms, watching daily reports about how African-Americans, like me, in my age range, with hypertension, were dying. I live alone, so I had to struggle alone, recover alone, hoping not to die alone.

Kimwa Walker, 49, Durham, N.C.

I waved goodbye to my significant other as I was wheeled into the E.R. I thought I had bronchitis. It turned out to be Covid-19. I wouldn’t see him again — except through a plate glass door — for five and a half months.

Kathy Glascott, 73, Kissimmee, Fla.

When Covid took my great-aunt in Maryland, left, (who was wild and vivacious) and then her brother in the U.K. less than two weeks later. Attending her Zoom funeral was entirely too real.

Kimberly Parkinson-St. Jean, 36, Newark, N.J.

When my father passed away from it.

Molly McLaughlin, 47, Cleveland Area

When my son died in May 2020 in New York City. He was 54 years old.

Robert Castro, 83, Merrick, N.Y.

My aunt died. She was the 34th reported Covid death in Connecticut. That was the day that I learned that Covid was not going to be a disease that happened to “other people.”

Bill Wight, 62, Kingsport, Tenn.

The last time I held my father’s hand.

Lisa Dean-Erlander, 52, Boise, Idaho

Photo credits: Deirdre Bell, Piper Smith, Erin Hughes, Antonino Clemente Mayra Nolan, Jess Sauer, Kelley Sykes, Helene Rutledge, Emma Johnson, Kyley Pulphus, Megan Denniston, Benny Chan, Kate Wasson, Alicia Pike-Green, Megan Langley-Cass, Veronica Torres, Christina Kratlian, Felicity Nicholson, Jackie Doughty, Sasha Hizon.

Aidan Gardiner and Steven Moity contributed reporting. Asmaa Elkeurti and Fahima Haque contributed research.

Sarah Mervosh is a national reporter based in New York, covering a wide variety of news and feature stories across the country. More about Sarah Mervosh

- Share full article

Advertisement

Three Years Later: How the Pandemic Changed Us

From routines to deep losses, the global health crisis altered lives of staff and faculty

Since her father’s death from COVID-19 in 2021, Alexy Hernandez’s days have become emotional minefields. Any small thing can be a gut punch, reminding her of what’s lost.

Perhaps it’s a football highlight, since she and her father, Josue, shared a love of the sport. Coffee has become complicated since her dad always got a kick out of pictures she sent of the creative designs left in her latte foam.

Or maybe it will simply be the small pieces of her daily routine — getting into work in the morning, coming home at night — experiences that warranted a quick text to her dad, who always wrote back with love and encouragement.

“He was my best friend, my biggest supporter, my biggest cheerleader,” said Hernandez, 28, a clinical research coordinator with the Department of Population Health Sciences . “I am who I am because of him.”

The pandemic changed the way most of us lived. We learned how to work remotely or gained new appreciation for human connection. And, for the loved ones of the roughly 1 million Americans who died from the virus, life will forever feel incomplete.

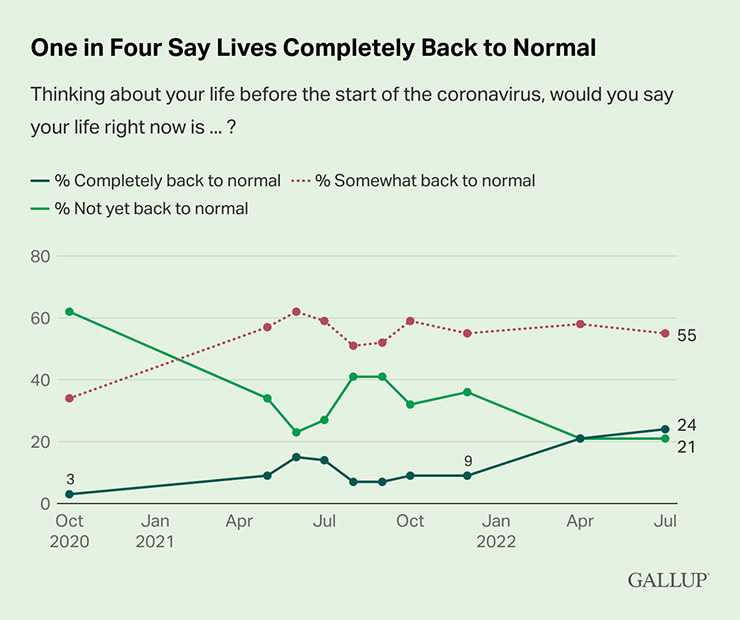

While the worst of the pandemic may be behind us, its effects linger. According to a Gallup poll , 53 percent of U.S. adults don’t expect their life to ever be the same as it was before the pandemic.

“We all felt this,” said Rachel Kranton, the James B. Duke Professor of Economics who, early in the pandemic, contributed to Project ROUSE , an independent Duke faculty research study that looked at how staff and faculty at Duke coped with changes to life, work, and well-being.

Project ROUSE showed that the pandemic had profound effects on everyone, including that, during the pandemic’s first year, roughly 40 percent of nearly 5,000 study respondents were at risk of moderate or severe depression.

As the pandemic’s difficult early days fade, Kranton said that other changes will likely endure, such as a willingness to connect in new ways, reassess careers, or build lives with more flexibility.

“I think there’s probably a new normal, and I think that new normal includes both good things and bad things,” Kranton said.

Hernandez’s life won’t be the same after her father’s death, but she is moving forward.

She’s learned not to stress about trivial things and thinks often about how she can make her father proud. Nothing, she said, can be taken for granted.

“Losing my dad has completely changed how I view and interact with the world and has given me more clarity on what I value,” said Hernandez, who has worked at Duke for four years.

We asked staff and faculty to share how the pandemic changed their lives, and here’s what some colleagues shared.

‘I’ve learned from students’

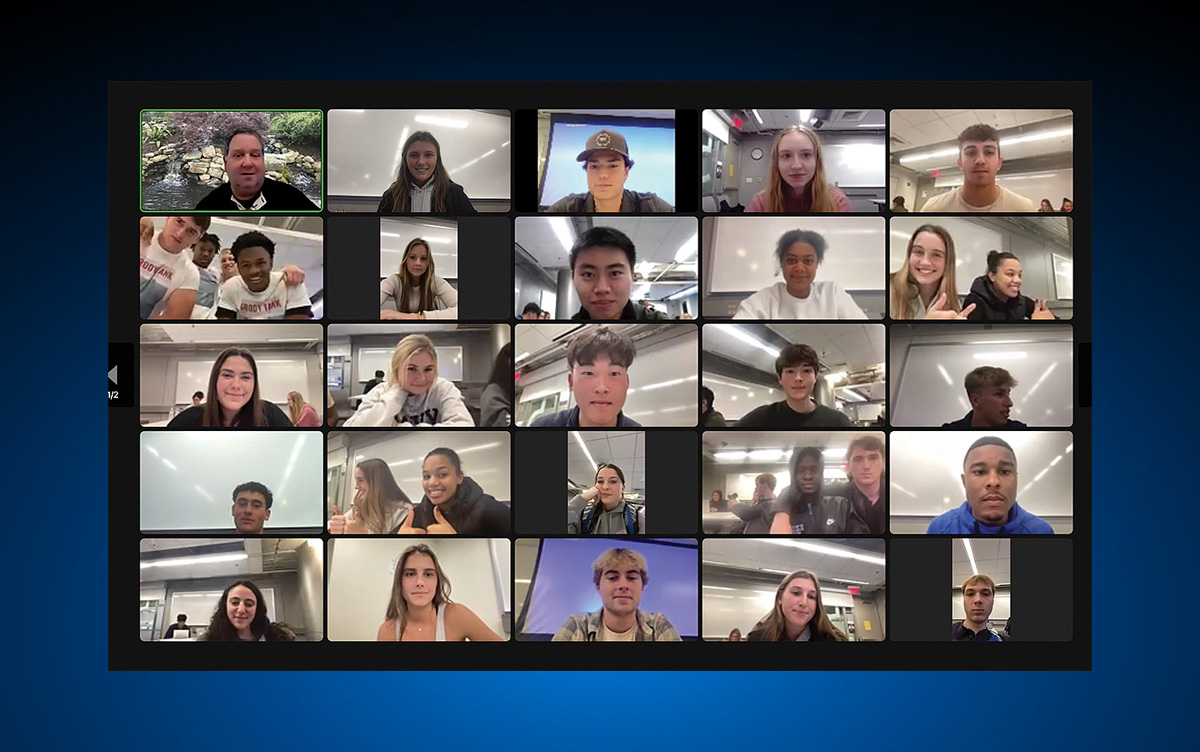

“It’s a new normal. You’ve got to deal with what you’ve got to deal with. Teaching markets and management, I’ve tried to move on and try to keep things fun. I like to make my courses interactive. So whether that’s changing materials or adding new things to a class, I’ve had to adapt. A lot of new stuff I’ve learned from students, whether it’s using polls, or Kahoot, or other activities. You’ve got to keep things fresh. The world is changing, you’ve got to change with it.”

George Grody, 64, Lecturing Fellow of Markets & Management, Trinity College of Arts and Sciences

Value of Life

“I appreciate more than ever before, not only the value of life, but a strong appreciation for others in the respiratory field and healthcare. I have been a respiratory therapist 33 years, and I’ve worked at Duke 35 years. Many have come and some have gone from this world. It’s devastating when you’ve worked so hard on patients, and they don’t make it out. Nothing can replace the value of life and what it means. Life is so important, and each and every day that you work with your patients is important. This all taught me a lot about what it means to really care for your patients, and it taught me a great deal of humility in caring for those who needed me.”

Pamela Bowman, 63, recently retired Respiratory Care Practitioner, Duke Regional Hospital

Out of the Quiet

“Though it’s crazy to say, my life started to flourish during the pandemic in more ways than one. I went back to school at the beginning of the pandemic at Durham Technical Community College to study business. I got in the best shape of my life by focusing on clean eating, and I lost 35 pounds. I started earning more money by taking a job at Duke. The pandemic was a time for me to quiet down the noise around me. Personally, I was able to shut out the world, decide what I really wanted out of life, and for myself, and start making those things happen. Ever since things started getting back to how they were pre-pandemic, those progressions I’ve made slowly started to derail. I gained back the 35 pounds I lost once the world started to open up again, and it’s just been harder to do everything I was doing to better myself every day. I went into a bit of a depression, but now I’m finally coming out of it. I’m back down 20 pounds. I’m learning how to cope with things and get back to being able to do those things that progressed for me and made me happy, even though I’m not able to get the same quietness I once had.”

Sadie Horton, 27, Staff Assistant, Academic Support, Fuqua School of Business

Cherish Loved Ones

“My mom, Johnnie Mae Snipes, was put on hospice on Jan. 11, 2021, and she passed away on January 20, 2021, at age 83. Me and my sisters were holding her hand, and, needless to say, we lost the strongest woman we ever knew. Our queen was gone. My mother had six daughters, 17 grandchildren, 44 great grandchildren and seven great, great grandchildren. My mother passed away from dementia and COVID. The past few years have taught me to never take anything for granted and to cherish your loved ones. It also has showed me how the world can change in one day. But one thing I know for sure that will never change is God is still in charge.”

Clara Bailey, 58, Staff Assistant, Department of Medicine, Oncology

‘I don’t go anywhere without my mask’

“When Dr. Anthony Fauci came out and said we need to wear masks in public, I did it. I’m claustrophobic, so when I first started wearing the cloth masks, I would have panic and anxiety attacks, particularly at the grocery store. Over time, I got used to it, and I started feeling safer by wearing my mask. Now, I don't think I will ever go into another crowded event without a mask. As a woman, we have our purses. We don’t go anywhere without our purses. Now, I don’t go anywhere without my mask. Since wearing my mask, I haven't caught a cold, let alone anything else. It's a piece of cloth, no big deal.”

Sandy Ouellette, 62, Access Specialist, Consultation & Referral Center

Rethinking What’s Most Important

“During the pandemic, my wife got a new job in Virginia, and because I’ve been working remote since March 2020, it made it easy to move with her because, in the past, somebody would have had to quit their job, find a new job, and do all kinds of stuff. Personally, the pandemic has made me rethink what’s most important in life, such as making sure to set aside time for family and friends. Now, I get to spend more time with my wife. We can do house projects, take our dogs out and explore. Now that our parents are getting older, we try to take advantage of any time we can spend with them. The pandemic made spending time with people who are important to you a little extra important because they’re what helped me get through.”

Christopher Morgenstern, 39, Administrative Manager, Cardiology

‘180-degrees different’

“My wedding, honeymoon, and bachelorette party were all canceled due to COVID, so my husband, Brent Durden, and I got married in our backyard with just our parents. We were going to wait several years to start a family so we could travel but decided to seize the day during quarantine after buying a house. Now, we have a beautiful 18-month-old daughter, Eliana. As tragic as the losses we experienced as a country and community have been through this pandemic, my entire world is 180-degrees different than it was before COVID, and it makes me so grateful to have the family that I do.”

Tricia Smar, 36, Education and Training Coordinator, Duke Trauma Center

‘I’m fulfilling my bucket list’

“I have terminal prostate cancer. I live one day at a time. They gave me 18 months to live about six years ago. During the pandemic, I retired to fulfill my bucket list only to find disappointment. I made all sorts of plans, but everything was shut down so my plans were shot. I returned to work. I have a love for nursing and have no regrets coming back to patient care. I missed interacting with people. I missed my coworkers, I missed the patients. Now I travel, and I'm fulfilling my bucket list, but I always look forward to coming back to Duke for both my own care and to care for our patients.”

Doug Buehrle, 68, Clinical Nurse, Apheresis, Duke University Hospital

Savor Small Moments

“I learned to make the best out of a horrific situation. My kids, Derek and Joshua, were 5 and nearly 3 when COVID hit. In the clinical research field, we had to scramble to see which trials could keep going and which ones would have to go on pause. We had to be very flexible to work around each other’s schedules and everyone’s kid’s schedules. But I got to spend a lot more time with my kids than I ever would have if COVID didn't hit, so I'm grateful I was able to do it. We got to spend time going to the park and flying kites since the playgrounds were closed. We went hiking and exploring since the museums were closed. Those were memories I am thankful to have made, and I'm hoping they don't fade.”

Kristin Byrne, 41, Clinical Research Coordinator, Hematology

‘Packed up my car with as much as I could fit into it’

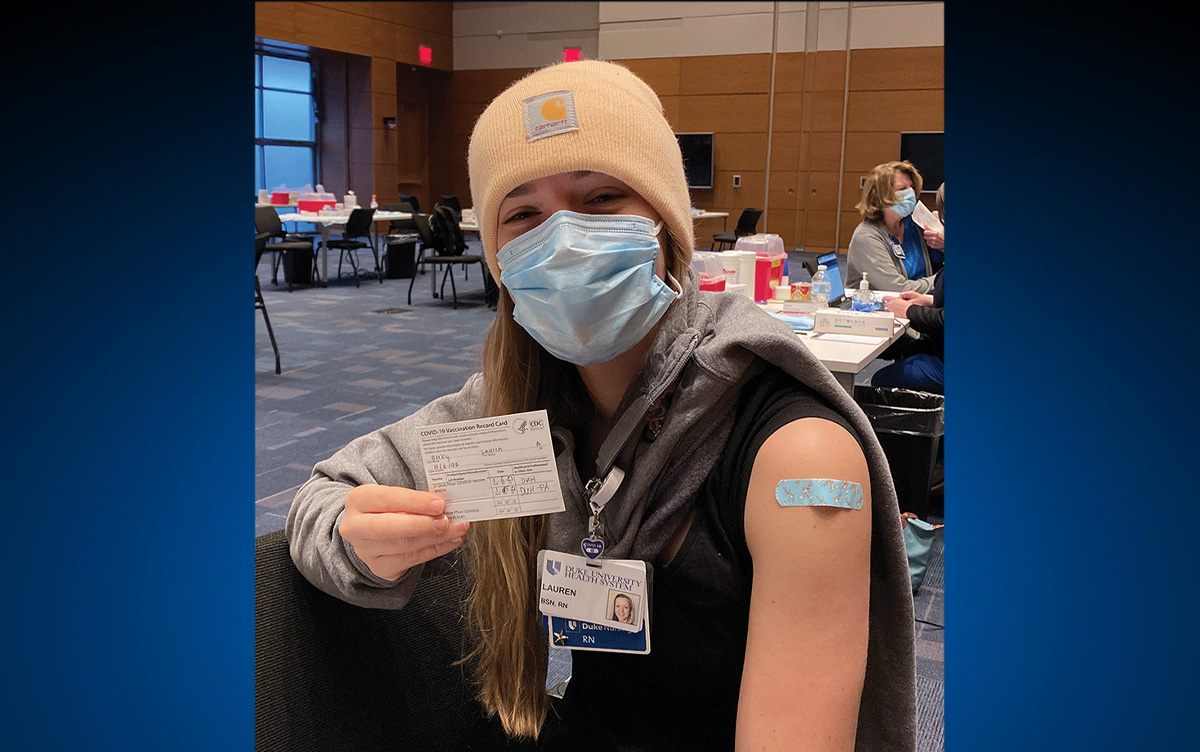

“I graduated from nursing school at George Fox University in Oregon about a month after lockdown happened. I have a grandmother in High Point, so I started applying to hospitals in North Carolina, and Duke turned out to be the best option. In October of 2020, I packed up my car with as much as I could fit into it, and I drove across the country with my dad. I left my family, friends, my church back in Portland, and I’ve had to build an entirely new life here. My first nursing job was working for the medical-surgical float pool at Duke University Hospital, which basically staffed the COVID-19 floors for a while. I was thrown into the thick of it, and I really had to stay on my toes all the time. It was really hard, and it was really a dark period in my life, until I started to get my feet settled. I just started to put myself out there out of my comfort zone, and I started inviting people to do things with me. I found Bright City Church too. Over time, I started to find those little sparks of hope, when you send a patient home instead of the ICU. I’ve learned a lot from my nursing career, and I’ve learned a lot about myself and how to take care of myself.”

Lauren Berky, 25, Clinical Nurse, Internal Staffing Resource Pool

‘More Openness to Change’

“I think COVID has opened the clinical community to change more than ever before. Sharing data has replaced hoarding data. Technology has come so far, and we had a hard time getting people to change the way they think about data. I think COVID opened their minds that we need other ways of dealing with data, particularly that the patient needs to be the centerpiece of everything that we’re doing. Some people have said to me, that five years ago we’d have been laughed at for some of the things we’re trying to do. But now, everybody is at least willing to have the conversation.”

William Edward Hammond, 88, Professor of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Family Medicine and Community Health

‘Never take tomorrow for granted’

“I am much more committed to ‘living in the moment,’ appreciating what I have, and looking inward. At home, I find joy with my husband. I walk much more. I cook at home almost all the time. And, maybe most important, I appreciate the beautiful natural environment around our home on Morgan Creek in Chapel Hill, where husband, David, and I began walking nearly every afternoon in January 2021. I’ve learned to never take tomorrow for granted. To appreciate friendships and family and the place where we are, now. To be OK with less ‘running around.’ To not take progress for granted, and to realize that things can get worse.”

Anne Mitchell Whisnant, 55, Director, Graduate Liberal Studies, and Associate Professor of the Practice, Social Science Research Institute

Bittersweet Milestones

“COVID was honestly a bittersweet time. My father-in-law, Mark, the president of North Georgia Technical College, passed away from COVID on September 13, 2020. Then in January 2021, my husband, Andrew, and I found out we were pregnant with our first child, Lilly, after a very long time. We thought we couldn’t have kids, so that was quite the surprise. When she was born on October 21, 2021, the joy of having her was indescribable. She just turned a year old, and I know she’ll never know her grandfather, and he’ll never know her. We want her to be happy and healthy and treat others the best way possible, and we’ll continue to tell her about her Papa when we can. We can’t wish Mark back because he’s not coming back. We’re living in the reality knowing that we can’t change it; it’s something Ecclesiastes calls our lot in life. COVID-19 brought out the worst for so many families, including ours, but it also brought so much good.”

Marissa Ivester, 34, Fellowship Program Coordinator, Office of Pediatrics

Send story ideas, shout-outs and photographs through our story idea form or write [email protected] .

- LATEST INFORMATION

- High contrast

- Our Mandate

- The Convention on the Rights of the Child

- UNICEF Newsletter

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Multiple Cluster Survey (MICS)

- Partnerships and Ambassadors

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

How covid-19 changed lives - voices of children.

UNICEF Georgia asked children and young people around the country how they are coping with the new normal, and how their lives have been affected.

- Available in:

Being a school student can sometimes be challenging, but the COVID-19 pandemic has made getting an education, and life in general, even more difficult for young people in Georgia.

With schools closed, lessons are being held remotely. All sports, school activities, and events have been cancelled. Friendships and relationships have been transported to live chats and video calls.

Mate Dvalishvili, 15 years old, Kutaisi

The COVID-19 pandemic has radically changed my life. When I used to go to school, by the end of the day I would be exhausted – mentally as well as physically – and as a result, I did not have trouble falling asleep. Now, I don’t get tired enough during the day, so I can’t sleep at night, and I wake up late in the morning. That’s why I am sometimes late for, or even miss, video classes.

Before, I used to wake up at 8 a.m., and by 9 a.m. I was already at school. After classes I went to a tutor, then to play sports. When I came home, I did homework and hung out with my friends, if we had free time. I went to bed sometime between 11 p.m. and midnight. Now, I get up at noon, or even as late as 1 or 2 p.m. When the weather is good, I may go out to ride my bicycle with my family members, but the rest of the time I’m at home playing online games and watching films. I go to bed at 1 or 2 a.m., and at times, I am video-chatting with my friends until 3 or 4 a.m., sometimes until morning.

The teachers are trying to teach our classes like they did in school, but still, I can’t say that online classes are as interesting as they were in person. At least now, I have a bit less homework to do. I was more active during classes while in school, there was more interaction. The programmes that we use for online classes cannot replace school. In order to make online learning effective, they should develop a special online programme that could be adapted to school teaching. At the same time, teachers should be familiar with using the programme.

For me, the hardest thing in the new reality is the new reality itself: doing nothing (for almost 2 months), and the immense lack of communication with my friends in real life. It is not unbearable, but it is very difficult.

Keta Tkhilaishvili, 10 years old, Batumi

My life has changed completely since my school was closed. Before, I spent most of the day at school with my classmates. Now, this is my free time.

When I went to school, my schedule was really full. I got up early, prepared for school, and I also had extra classes like German, chess, circle dancing, and so on.

Now my schedule is organized according to the self-isolation rules. I wake up at 10 a.m., I have breakfast, and then I have my online classes. I spend my free time as I wish, then I prepare my lessons. Sometimes I watch classes on TV. I am at home all the time. Since I have plenty of time now, I try to balance out working and free time on my own.

Interaction with my classmates in school is what I miss the most from before. When I went to school, I had more homework, but the lessons were way more engaging and interesting, I could concentrate better. Online schooling is something very new. At times, I struggle with online group studying because I don’t understand what the teacher is saying because of the Internet connection and other technical problems. But it’s interesting too. I learned how to do homework electronically and search for information on the Internet. Before, I thought that the Internet was only for playing and entertainment.

I want to go back to school soon, and before that happens, I want to be able to communicate on the Internet without interruptions.

Sandro Turabelidze, 11 years old, Village Jimastaro, Imereti

During the pandemic I had to switch to distance or online school. I don’t find learning online difficult, it is easy. Before the class is over, teachers give us an assignment, we do the homework, take a photo of the exercise book, and send it to the teacher. During the next lesson the teacher tests our knowledge. When I have free time, I play with my sister at home. I no longer visit my neighbors. I play by myself in the yard, I try to stay isolated. To spend time with my friends, I call them, we talk to each other, and play online. I go out to the yard for 5-10 minutes only, to play something by myself, like ride the bicycle, or play ball by myself, and then I go back inside as I try to avoid contact with neighbors.

Elene Iashvili, 11 years old, Kvitiri

I live in the village of Kvitiri and I go to the Kutaisi Chess school. I had great plans this year. I was so excited to participate in the Georgia, Poti, Racha, and Tkibuli chess tournaments. Traveling around the country during tournaments is so much fun. We would go to the sea to relax after the game in Poti, and we would cozy up and enjoy the fresh air in the evening in Racha. In Tkibuli, we got to go to the swimming pool. Now, I play online chess games with a computer. Online chess tournaments are held for adults only. They are very rarely held for children my age. I also play with my grandfather, but it is very difficult for a child chess player to develop during quarantine.

I was very sad at the beginning, but my friends and I found a solution together. We created a chat and communicate via that chat very often. We named the chat “girls” but later we added boys to the group as well. These relationships are very helpful.

We became tied to our computers after the schools closed. Online classes can’t replace in-school classes. At school they explain the content in more detail. And also, many of my classmates can’t attend online classes. They may have the Internet, but don’t have a personal telephone or laptop. It would be unfair if they have problems because of this.

During self-isolation, I got interested in taking photos. I go out to the yard, take photos of the flowers. Now the strawberries have ripened. I try to take joyful photos to cheer up people who are locked inside. Having a relationship with nature is one way to keep spirits up.

Luka Turabelidze, 10 years old

I am in the fourth grade and have been studying online for 2 months now. Online learning is not hard at all.

I spend my free time riding my bicycle, and playing with my ball. I am lucky to have a yard, we don’t have to stay inside the house all the time. But, we don’t visit others and no one comes to visit us. That is why I am a bit bored. Also, I miss my classmates. I do talk to them on the phone, but meeting them and playing is a totally different thing. My mother and father are saying that the pandemic will go away soon and we will be able to live our lives like before. I hope that we will be able to go to the river and have a good time this summer.

Nana Samkharadze, mother of Tekla and Lile Machavariani

Tekla and Lile are having a good a time as possible during the pandemic. We try to keep up with their education – they are 4 and 5 years old – and we are teaching their age-specific skills as much as we can. We learn letters, numbers, addition and subtraction, and most of the time we play. We come up with different things. The girls have even made a small flower alley. The entire house is filled with their toys. So, we are having fun together and trying to make sure that the children do not feel the pandemic and its effects. It’s good that they have each other, they would probably be much more bored if they were alone.

Giorgi Kapchelashvili, 17 years old, Kutaisi

The recent changes have affected me very deeply. Staying at home for such a long time is bad for one’s health. Most of the time I am on the computer. I miss real life communication with others a lot.

Before, I woke up at 8 a.m., now I wake up in the afternoon. I play on my phone while still in bed. Next, I have “breakfast” and again – telephone. The exception is the three days a week when online classes start at 10 a.m., and I have to wake up early.

I think one can receive a good education through distance learning, if willing. But real school was more interesting, because discussions with friends helped me to better understand the content. I love mathematics very much, and I miss going to the math teacher.

Although, I have found one upside – I’m in a band, I play an electric guitar. During this quarantine I have improved my playing technique considerably. I have also improved my English language skills. My sister is an English teacher and has helped me with my English.

Amiko Turabelidze, 12 years old

I love TV school programmes, and I watch them often. I personally like distance learning very much, because I have more free time. Now, I can spend more time riding my bike, drawing, and listening to music. I also help my grandfather in the vineyard. I communicate with friends on the Internet, but we cannot see one another and talk. I hope everything will be alright and we will see each other soon.

Nika Khelaia, 13 years old

Initially, I was afraid that online classes would be difficult, but it doesn’t seem as hard as I expected. In a way, it’s even easy. Currently, anatomy is the most interesting subject for me, because I am going to become a doctor, specifically, a surgeon. I usually take part in a lot of competitions, and I hope to be able to participate again starting in September.

I spend my free time with my brother, I ride my bicycle, and spend time outside. I have a younger brother – he’s 2 years old – and I try to keep him entertained. I give my parents a hand so that they have time for household chores.

Related topics

More to explore.

Young people improve their digital skills thanks to UNICEF and business partnership

USAID and UNICEF review results for the partnership initiative to prevent and respond to COVID-19 in Georgia

Educational Programme “Hygiene Protectors” was launched

On a World Youth Skills Day, a new youth led public health campaign launched with support from UNICEF and USAID

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Covid 19 — How the COVID-19 Pandemic Changed Our Lives

How The Covid-19 Pandemic Changed Our Lives

- Categories: Covid 19

About this sample

Words: 783 |

Published: Sep 7, 2023

Words: 783 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Remote work: a new normal, online learning: education in a new era, social distancing: navigating isolation, mask-wearing: a symbol of solidarity, adapting and coping: strategies for resilience, 1. flexibility and adaptability, 2. prioritizing mental health, 3. supporting vulnerable populations, 4. promoting resilience through education.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 617 words

1 pages / 603 words

4 pages / 1827 words

1 pages / 670 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Covid 19

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the indispensable role of accurate information and scientific advancements in managing public health crises. In a time marked by uncertainty and fear, access to reliable data and ongoing [...]

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus, has had far-reaching consequences on individuals' lives worldwide. This essay will explore the personal impacts of the pandemic, focusing on mental and emotional [...]

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought unprecedented challenges to healthcare workers worldwide. This qualitative essay employs a research approach to gain insights into the perceptions and experiences of healthcare workers on the [...]

The United Kingdom has long been a popular destination for tourists from around the world, known for its rich history, diverse culture, and stunning landscapes. However, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 had a [...]

As a Computer Science student who never took Pre-Calculus and Basic Calculus in Senior High School, I never realized that there will be a relevance of Calculus in everyday life for a student. Before the beginning of it uses, [...]

Good morning, today I am going to give a speech on something that is hot in the news at the moment and could potentially harm us, that thing is a coronavirus. There isn’t a huge amount to say about it as it is still being [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Living Through a Crisis: How COVID-19 Has Transformed the Way We Work, Live, and Research

1 Microsoft Research, 1 Microsoft Way, Redmond, WA 98052 USA

Kori Inkpen

2 King’s Business School, King’s College London, Bush House, 30 Aldwych, London, WC2B 4PH UK

Geraldine Fitzpatrick

3 Institute for Visual Computing & Human Centered Technology (HCI Group), TU Wien, Argentinierstrasse 8, 193-5, 1040 Vienna, Austria

Naomi Yamashita

4 NTT Research Labs / Kyoto University, 2-4 Hikaridai, Keihanna, Kyoto, 6190237 Japan

5 KAIST, 291 Daehak-ro Yuseong-gu, Daejeon, 34141 Republic of Korea

The COVID-19 pandemic abruptly changed all aspects of our lives, including the way we worked, how we socialized with friends and family, and how communities functioned. As many were instructed to stay physically separated at home, businesses, educational institutions, and other social institutions had to adapt to this new reality, often turning to video calling applications and other online collaboration technologies. Unlike previous crises, the global scope of the pandemic meant that nearly every country was affected and enacted policies that changed the way the entire population lived and worked. Many people lost their job due to shutdowns to prevent the spread of the pandemic. Many of those who continued to work had to figure out how to do their job working remotely from home. People in essential services also had to learn to work in new ways, avoiding physical contact or being close to others, aspects that are typically considered critical for the accomplishment of everyday activities.

This abrupt change in the landscape of work prompted fundamental changes in our entire lives. People had to quickly re-negotiate new ways of being together at home, which now served as an office, a classroom, a family space, and an extended social gathering place. Changes prompted by the crisis in the way we live, work, and stay socially connected, will undoubtedly affect how we will do so in the future, even after the pandemic subsides. Understanding these changes, learning from them, and exploring new directions is critically important. This special issue collects together empirical work, methodological examplars, and conceptual insights provoked by this unprecedented event.

For decades, CSCW researchers have considered the use of various technologies to support distributed work, from shared file folders to share information with a team to video-mediated systems to support synchronous activities over distance. These studies frequently raised concerns about the limitations of these technologies, not only related to general concerns like privacy, but also with regard to how they seemed to constrain the most mundane aspects of collaborative work, such as how people establish mutual awareness, and how they are able to communicate and coordinate effectively. However, within weeks people who may never have used these systems before had to undertake their day-to-day activities through these systems. This reaction was simultaneously a sudden adoption of technology, an adaptation of work and life practices to what the technology supported, and an opportunity to explore novel ways of staying connected while being required to stay physically remote. This special issue drew from a diverse range of research along those dimensions.

For example, although prior to the pandemic the number of people who had used, Skype and other video-mediated systems like Google Hangouts, were growing steadily, the crisis meant that for some this kind of technology, principally Teams and Zoom became a core feature of their work, with every meeting held in this way. Alongside the use of video for formal activities, many organisations sought to draw on the technology to also support informal interaction and maintain sociability. Researchers in CSCW have long considered the nature, advantages and disadvantages of video-mediated technologies and identified a tension in trying to design systems that support both formal and informal activities. The pandemic provides a resource, albeit an unwelcome one, to observe and analyse these tensions in practice.

The use of these technologies have also had an impact on other more specialised work activities, particularly ones that rely not just on talk and a head and shoulders image of colleagues, for example those where touch and embodied action is critical. These domains and new uses of the technology have the potential to shine new light on our understanding of collaboration, interaction and practice whether these are within general settings like meetings or for more specialised activities.

This issue therefore covers different domains. For example, social welfare services experienced a sudden increase in the number of people who needed those services, while at the same time navigating how to provide those services within the constraints of public health guidelines that limited physical contact. With the sudden shift to video calling for connecting over distance, there was also an opportunity to explore sharing other signals over distance to stay closely connected. As another domain, software development companies and software engineers, whose work is tightly coupled and interdependent, also needed to find new ways to re-establish common ground and collaborate at a distance, often through trial and error despite their technical affinity.

Furthermore, the research included in this special issue was situated in different geographic regions, including Europe, Middle East, Africa, Asia, Australasia and North, South and Central America, providing an international view of how companies, individuals and teams re-negotiated work and life in response to the crisis.

CSCW researchers themselves were also affected by the crisis. Studies with human participants were limited and constrained, prompting data collection to be undertaken in particular ways. The papers in this special issue reflect these research challenges as they describe the methods and approaches that were utilised during this crisis, including online surveys, iterative short polls, participant diaries, and online interviews.

Even the process of pulling this special issue together was affected by the pandemic response. Our original call for participation expected the due date (December 2020) to be after the crisis resolved and we all had a chance to reflect back on what happened. That timeline seems absurd as we continue to operate under the lingering effects of the pandemic as of this writing in summer 2022. We especially want to thank the authors for continuing to do research under pandemic circumstances, to all the reviewers, who found time in their disrupted schedules to give feedback, and the Journal for guiding us through an unexpectedly long and complicated process. We hope this collection of articles helps the community reflect on what we learned from a CSCW perspective through research on the COVID-19 pandemic response and shares how we as a research community are responding to its ongoing effects.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Kate Middleton

- TikTok’s fate

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66606035/1207638131.jpg.0.jpg)

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Want a 32-hour workweek? Give workers more power.

The harrowing “Quiet on Set” allegations, explained

The chaplain who doesn’t believe in God

Beyoncé’s “Jolene” and country music’s scorned woman trope

Could Republican resignations flip the House to Democrats?

Truth Social just made Trump billions. Will it solve his financial woes?

March 1, 2022

Introducing 21 Ways COVID Changed the World

The pandemic didn’t bring us together, but it did show us what we need to change the most

By Jen Schwartz

Hanna Barczyk

I n the spring of 2020 a cartoon was making the rounds on social media. It showed a city perched on a tiny island, surrounded by ocean. A speech bubble emerged from the skyline: “Be sure to wash your hands and all will be well.” Not far out at sea, a giant wave labeled “COVID-19” was about to crash over the city. Behind it was an even bigger wave marked “recession.” And beyond that one was a tower of water that threatened to swallow it all: “climate change.”

I’ve often thought of that statement, by Canadian cartoonist Graeme MacKay, in moments that seem to define our pandemic disorientation: the botched messaging, willful unpreparedness and exhausted confusion. In America, though, the cartoon didn’t play out exactly as drawn. The economy actually grew in 2021. Does that mean the damage wasn’t as bad as many predicted? That question can only be answered in the context of another superlative: the U.S. claims the highest reported number of COVID cases— as well as COVID deaths —in the world.

The past two years have been full of incongruities, paradoxes and absurdities. Consider the mRNA vaccines . Scientists formed a global hive mind and delivered a supereffective vaccine faster than anyone thought possible. But more than a year after the shots became available, the U.S. has one of the lowest vaccination rates among wealthy countries. Some Americans think the vaccine represents a weapon of oppression, if not a literal weapon.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The politicization of our best tool for ending the pandemic surprised everyone. Except for the behavioral scientists, misinformation researchers, sociologists, historians and speculative fiction writers who spent 2020 waving their arms ( sometimes in the pages of this magazine ), calling attention to cognitive bias, influence operations, accessibility issues and barriers to trust. COVID was never going to be the “common enemy” that finally united Americans. As Alondra Nelson, who is now deputy director for science and society at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, explained it to me in December 2020: “This idyllic idea of solidarity, especially in a wartime modality, is created by making an enemy of someone else.” Indeed, former president Donald Trump tried to make an enemy by blaming the virus on China. His xenophobic rhetoric has spread, feeding dangerous conspiracy theories , threatening scientific research and leading to a rise in hate crimes.

The virus provoked other reckonings and pivots—not all of them bad. Many of us who could do our jobs remotely discovered the power of owning our time . COVID concerns made it easier for European cities to install miles and miles of bike lanes, giving us a glimpse of a car-free urban future . The pandemic revealed strange hidden interdependencies; hospital demand for liquid oxygen, for example, delayed rocket launches . It also worsened inequality , increased the prevalence of depressive disorders, added “moral injury” to the common lexicon and set back students’ learning trajectories for years to come.

Amid the noise of an ongoing emergency, it can be hard to notice troubling new trends . We should be far more concerned about the shadow of long COVID. If millions of people end up developing persistent health issues after the acute disease stage, they will likely encounter a medical system unable to do much more than shrug. As with the climate crisis , many of us avert our eyes from the specter of long COVID because its effects tend to be more insidious than dramatic, and the fixes aren’t quick or easy. Dealing with the problem requires acknowledging what was already broken. Yet for every bleak future there’s a hopeful one. Propelled by the force of patient advocates, research into long COVID could lead to new understanding of other postinfection illnesses and autoimmune disorders.

When we planned this issue, Omicron had not yet emerged. I wondered if people would be interested in stories about a pandemic that wasn’t over, even if they were over the pandemic. Would we be fearmongering to suggest that the pandemic hasn’t ended because we haven’t vaccinated the world, leaving us susceptible to variants that are more transmissible?

We’re all over COVID. But we can’t give up and leave our collective fate to the machinations of a virus, sighing in relief when one peak crests (for those of us still unharmed) and leaning on wishful thinking that only the best-case scenarios will come to pass. Avoiding adaptation isn’t the key to reaching the endemic stage, nor will it help us prepare for the even bigger waves of climate crises . We assembled this collection of stories to reflect on how COVID has already changed our world, as well as how our world has been resistant to change—even when a virus disrupts everything, even when it shows us what we need to change the most.

- Skip to main content