- Appointments

- Resume Reviews

- Undergraduates

- PhDs & Postdocs

- Faculty & Staff

- Prospective Students

- Online Students

- Career Champions

- I’m Exploring

- Architecture & Design

- Education & Academia

- Engineering

- Fashion, Retail & Consumer Products

- Fellowships & Gap Year

- Fine Arts, Performing Arts, & Music

- Government, Law & Public Policy

- Healthcare & Public Health

- International Relations & NGOs

- Life & Physical Sciences

- Marketing, Advertising & Public Relations

- Media, Journalism & Entertainment

- Non-Profits

- Pre-Health, Pre-Law and Pre-Grad

- Real Estate, Accounting, & Insurance

- Social Work & Human Services

- Sports & Hospitality

- Startups, Entrepreneurship & Freelancing

- Sustainability, Energy & Conservation

- Technology, Data & Analytics

- DACA and Undocumented Students

- First Generation and Low Income Students

- International Students

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Transfer Students

- Students of Color

- Students with Disabilities

- Explore Careers & Industries

- Make Connections & Network

- Search for a Job or Internship

- Write a Resume/CV

- Write a Cover Letter

- Engage with Employers

- Research Salaries & Negotiate Offers

- Find Funding

- Develop Professional and Leadership Skills

- Apply to Graduate School

- Apply to Health Professions School

- Apply to Law School

- Self-Assessment

- Experiences

- Post-Graduate

- Jobs & Internships

- Career Fairs

- For Employers

- Meet the Team

- Peer Career Advisors

- Social Media

- Career Services Policies

- Walk-Ins & Pop-Ins

- Strategic Plan 2022-2025

Research statements for faculty job applications

The purpose of a research statement.

The main goal of a research statement is to walk the search committee through the evolution of your research, to highlight your research accomplishments, and to show where your research will be taking you next. To a certain extent, the next steps that you identify within your statement will also need to touch on how your research could benefit the institution to which you are applying. This might be in terms of grant money, faculty collaborations, involving students in your research, or developing new courses. Your CV will usually show a search committee where you have done your research, who your mentors have been, the titles of your various research projects, a list of your papers, and it may provide a very brief summary of what some of this research involves. However, there can be certain points of interest that a CV may not always address in enough detail.

- What got you interested in this research?

- What was the burning question that you set out to answer?

- What challenges did you encounter along the way, and how did you overcome these challenges?

- How can your research be applied?

- Why is your research important within your field?

- What direction will your research take you in next, and what new questions do you have?

While you may not have a good sense of where your research will ultimately lead you, you should have a sense of some of the possible destinations along the way. You want to be able to show a search committee that your research is moving forward and that you are moving forward along with it in terms of developing new skills and knowledge. Ultimately, your research statement should complement your cover letter, CV, and teaching philosophy to illustrate what makes you an ideal candidate for the job. The more clearly you can articulate the path your research has taken, and where it will take you in the future, the more convincing and interesting it will be to read.

Separate research statements are usually requested from researchers in engineering, social, physical, and life sciences, but can also be requested for researchers in the humanities. In many cases, however, the same information that is covered in the research statement is often integrated into the cover letter for many disciplines within the humanities and no separate research statement is requested within the job advertisement. Seek advice from current faculty and new hires about the conventions of your discipline if you are in doubt.

Timeline: Getting Started with your Research Statement

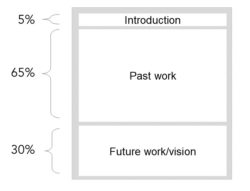

You can think of a research statement as having three distinct parts. The first part will focus on your past research, and can include the reasons you started your research, an explanation as to why the questions you originally asked are important in your field, and a summary some of the work you did to answer some of these early questions.

The middle part of the research statement focuses on your current research. How is this research different from previous work you have done, and what brought you to where you are today? You should still explain the questions you are trying to ask, and it is very important that you focus on some of the findings that you have (and cite some of the publications associated with these findings). In other words, do not talk about your research in abstract terms, make sure that you explain your actual results and findings (even if these may not be entirely complete when you are applying for faculty positions), and mention why these results are significant.

The final part of your research statement should build on the first two parts. Yes, you have asked good questions, and used good methods to find some answers, but how will you now use this foundation to take you into your future? Since you are hoping that your future will be at one of the institutions to which you are applying, you should provide some convincing reasons why your future research will be possible at each institution, and why it will be beneficial to that institution, or to the students at that institution.

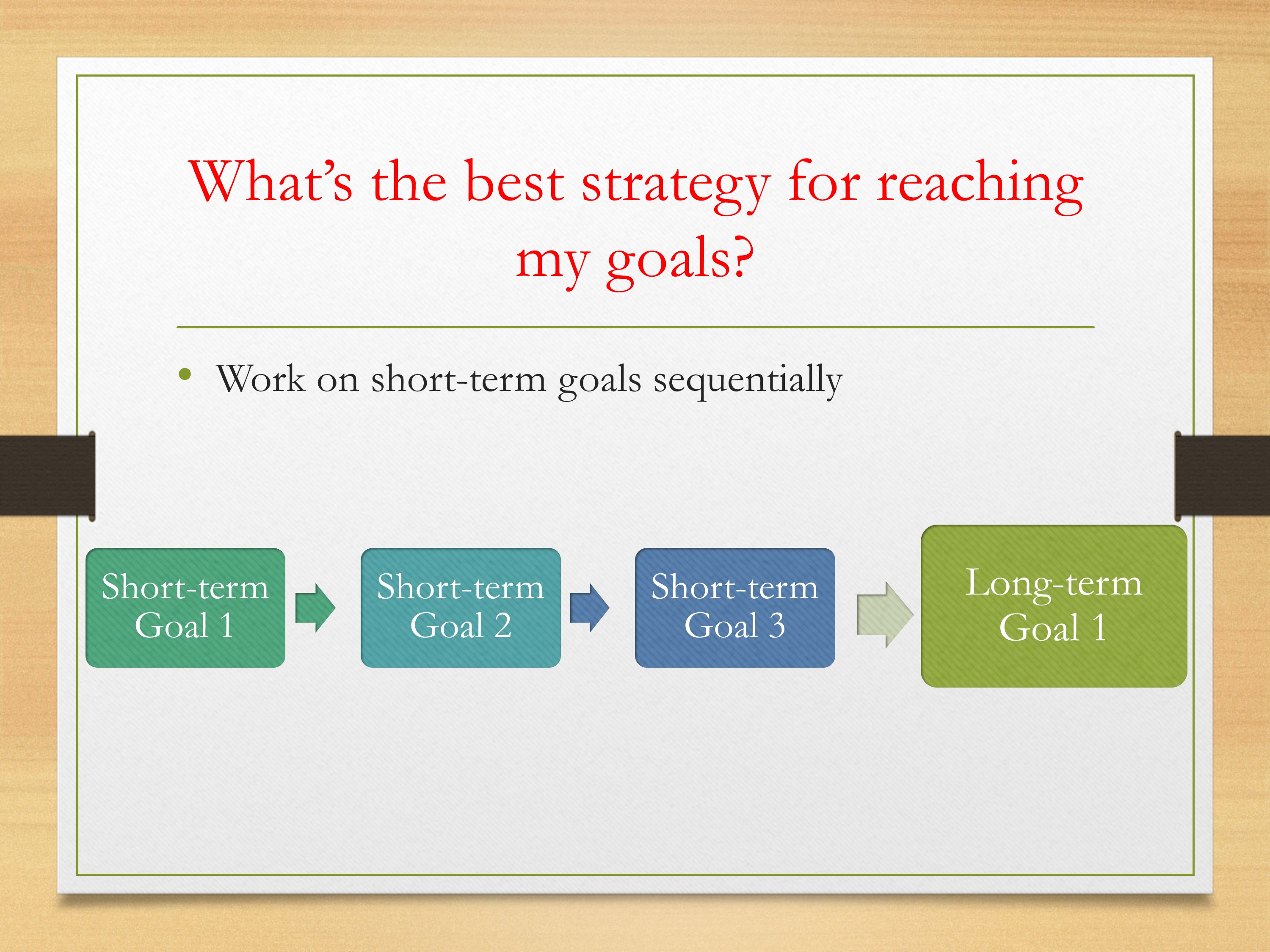

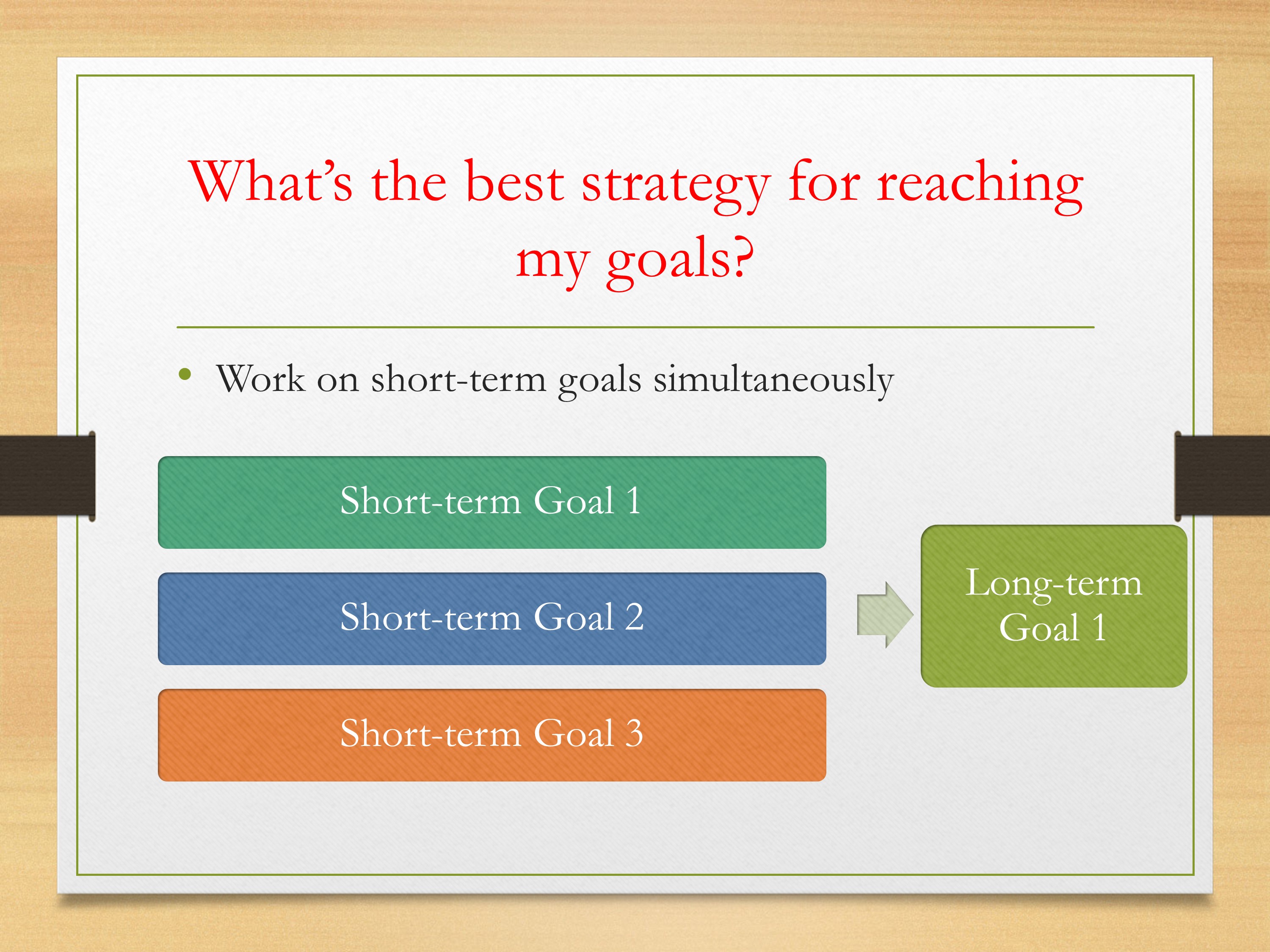

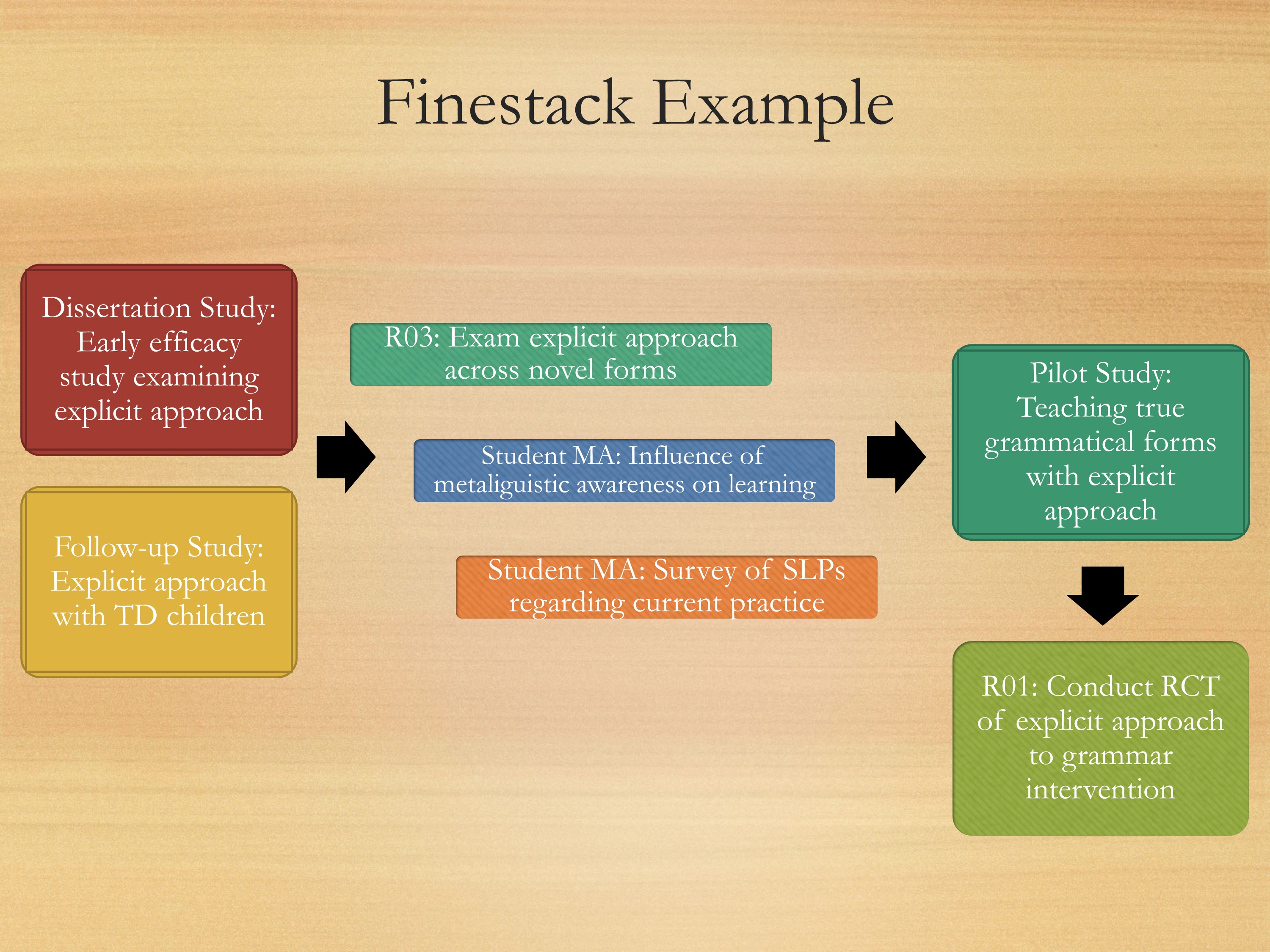

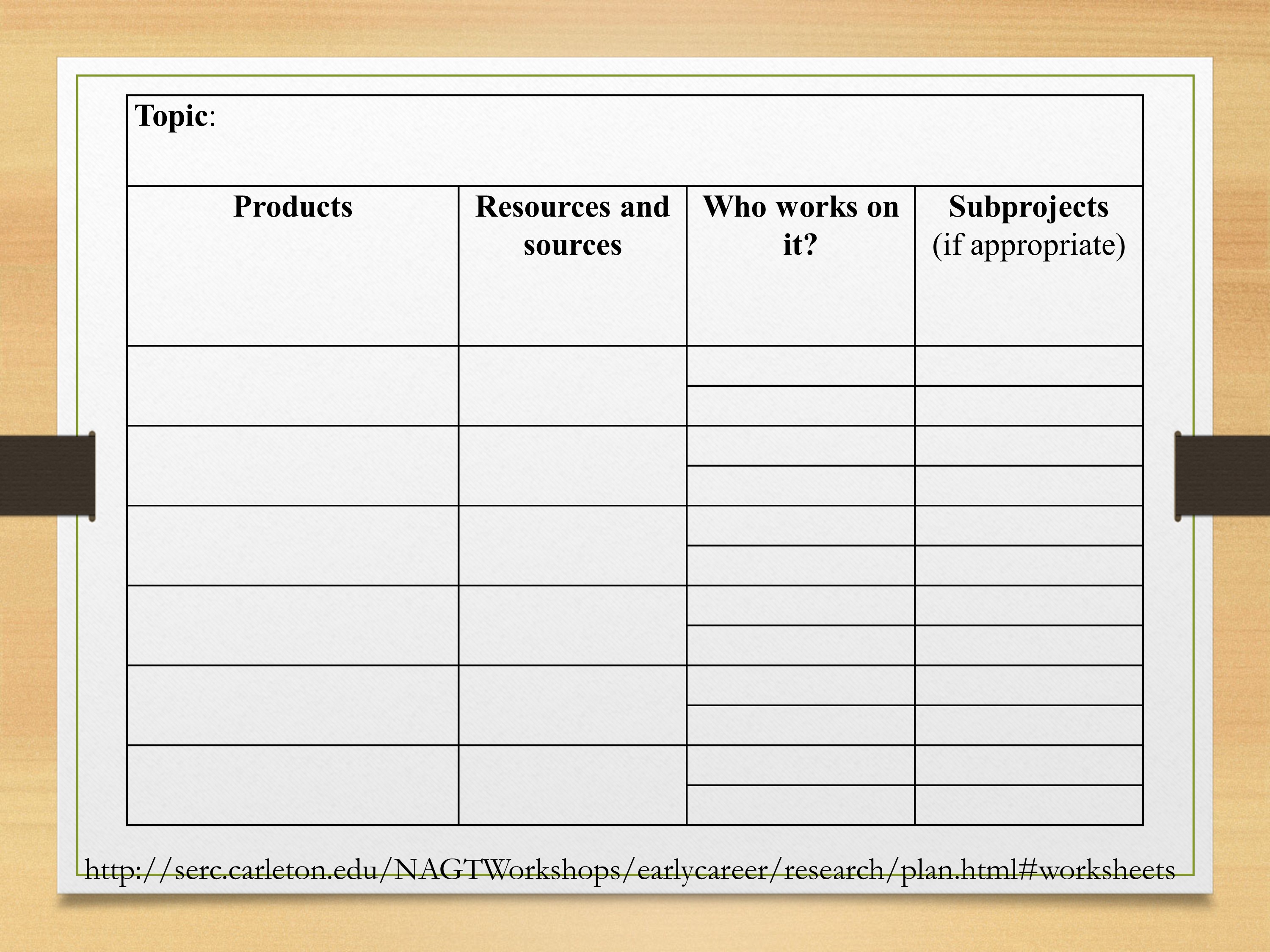

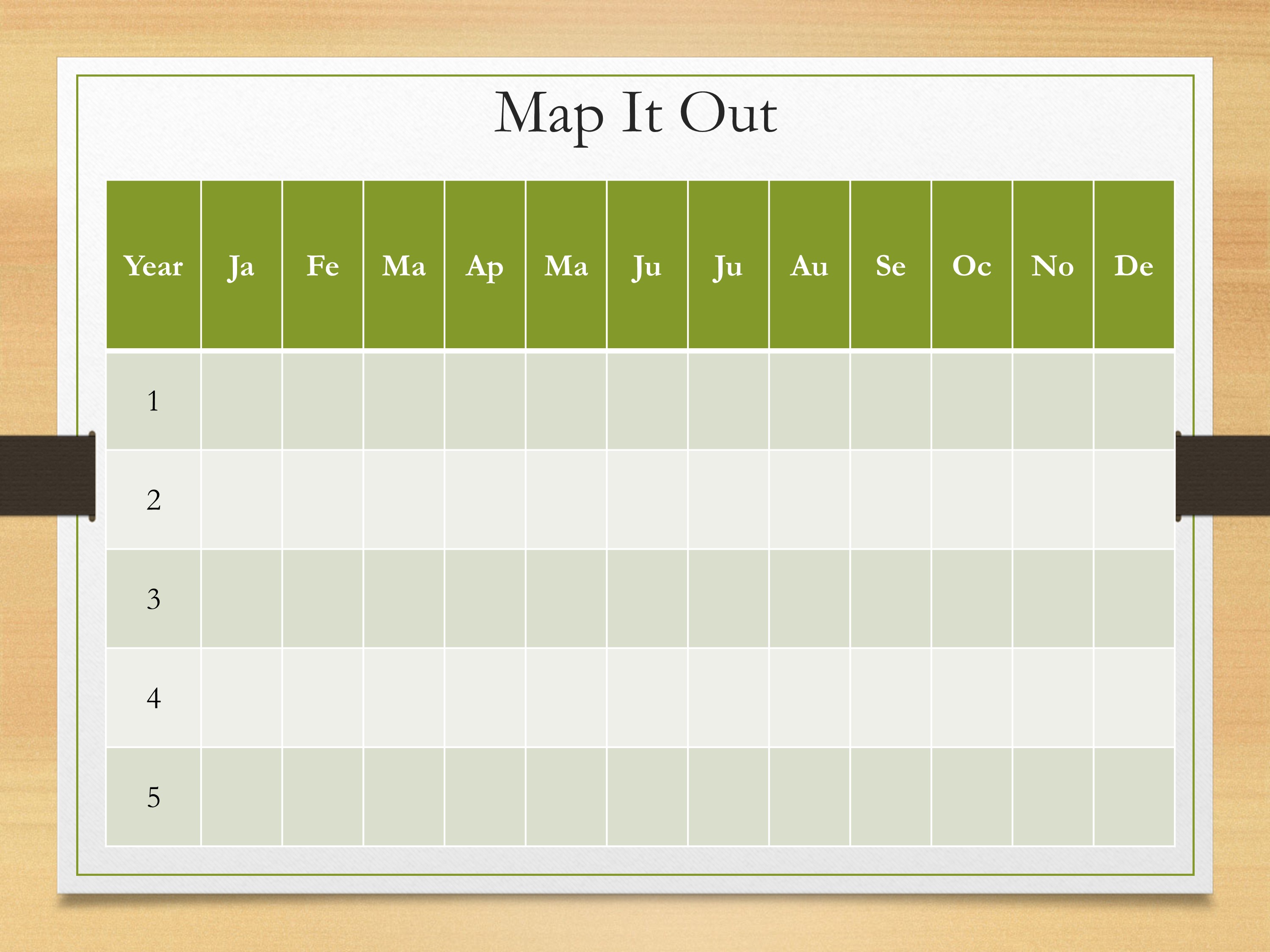

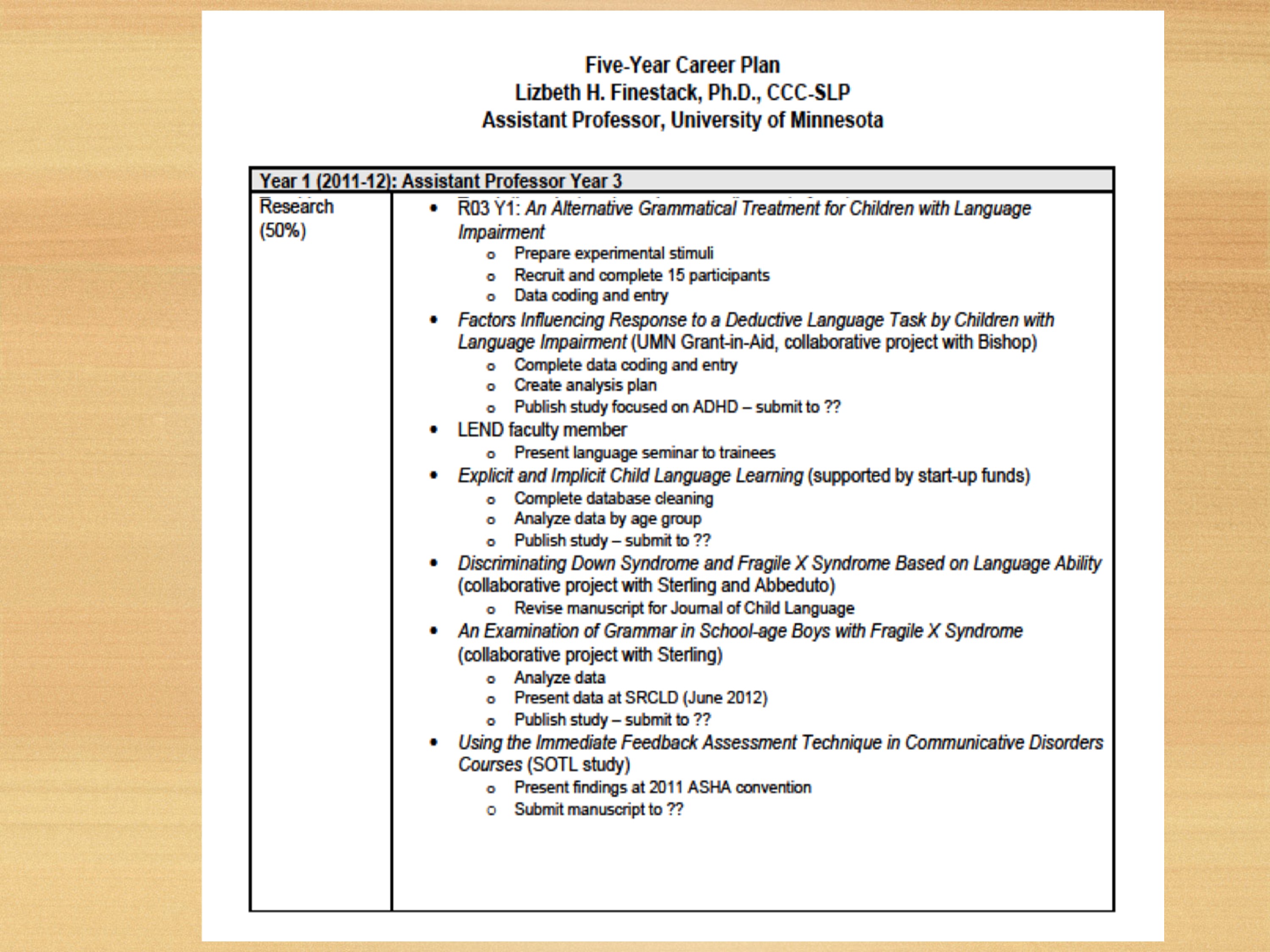

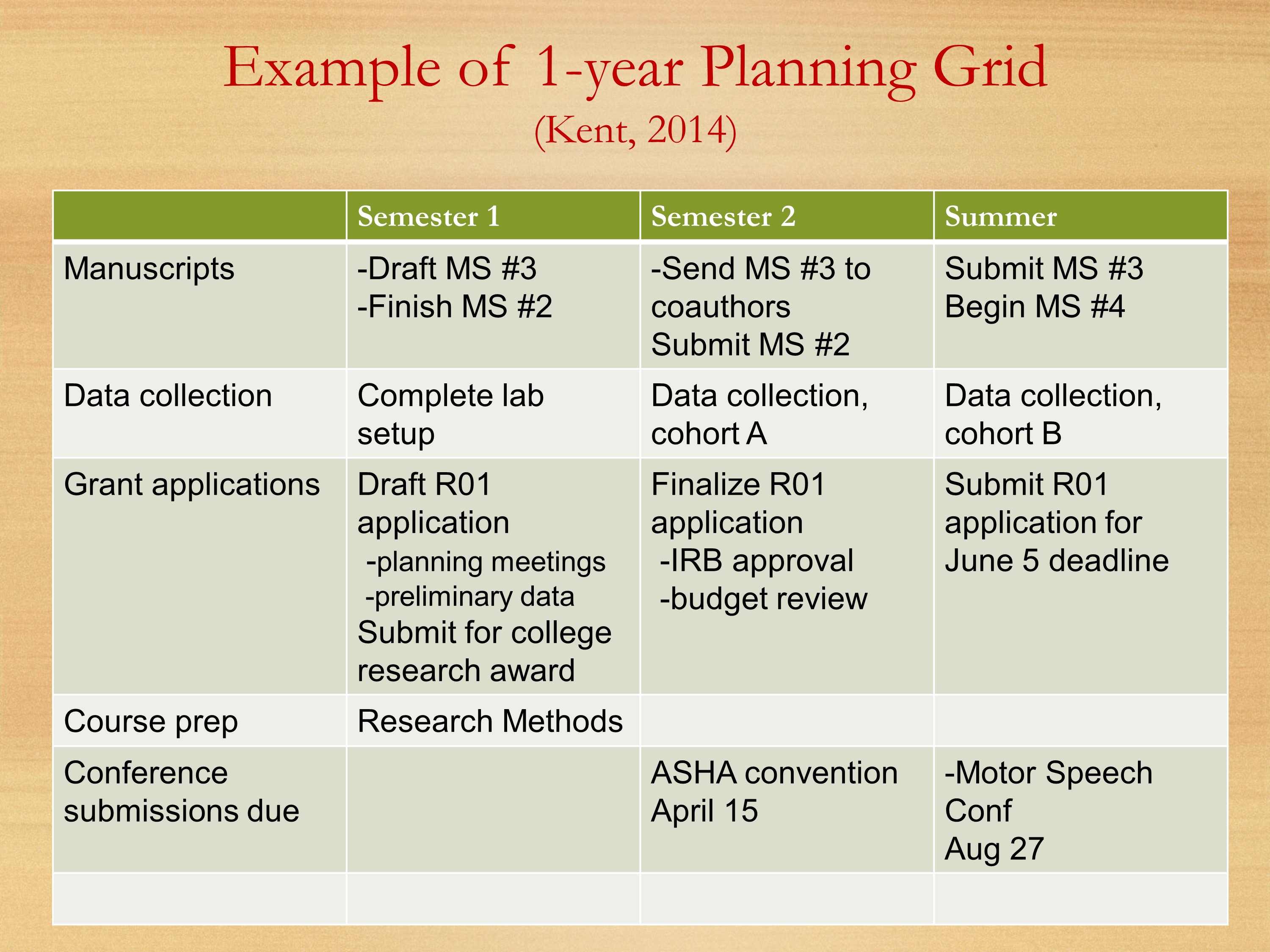

While you are focusing on the past, present, and future or your research, and tailoring it to each institution, you should also think about the length of your statement and how detailed or specific you make the descriptions of your research. Think about who will be reading it. Will they all understand the jargon you are using? Are they experts in the subject, or experts in a range of related subjects? Can you go into very specific detail, or do you need to talk about your research in broader terms that make sense to people outside of your research field focusing on the common ground that might exist? Additionally, you should make sure that your future research plans differ from those of your PI or advisor, as you need to be seen as an independent researcher. Identify 4-5 specific aims that can be divided into short-term and long-term goals. You can give some idea of a 5-year research plan that includes the studies you want to perform, but also mention your long-term plans, so that the search committee knows that this is not a finite project.

Another important consideration when writing about your research is realizing that you do not perform research in a vacuum. When doing your research you may have worked within a team environment at some point, or sought out specific collaborations. You may have faced some serious challenges that required some creative problem-solving to overcome. While these aspects are not necessarily as important as your results and your papers or patents, they can help paint a picture of you as a well-rounded researcher who is likely to be successful in the future even if new problems arise, for example.

Follow these general steps to begin developing an effective research statement:

Step 1: Think about how and why you got started with your research. What motivated you to spend so much time on answering the questions you developed? If you can illustrate some of the enthusiasm you have for your subject, the search committee will likely assume that students and other faculty members will see this in you as well. People like to work with passionate and enthusiastic colleagues. Remember to focus on what you found, what questions you answered, and why your findings are significant. The research you completed in the past will have brought you to where you are today; also be sure to show how your research past and research present are connected. Explore some of the techniques and approaches you have successfully used in your research, and describe some of the challenges you overcame. What makes people interested in what you do, and how have you used your research as a tool for teaching or mentoring students? Integrating students into your research may be an important part of your future research at your target institutions. Conclude describing your current research by focusing on your findings, their importance, and what new questions they generate.

Step 2: Think about how you can tailor your research statement for each application. Familiarize yourself with the faculty at each institution, and explore the research that they have been performing. You should think about your future research in terms of the students at the institution. What opportunities can you imagine that would allow students to get involved in what you do to serve as a tool for teaching and training them, and to get them excited about your subject? Do not talk about your desire to work with graduate students if the institution only has undergraduates! You will also need to think about what equipment or resources that you might need to do your future research. Again, mention any resources that specific institutions have that you would be interested in utilizing (e.g., print materials, super electron microscopes, archived artwork). You can also mention what you hope to do with your current and future research in terms of publication (whether in journals or as a book), try to be as specific and honest as possible. Finally, be prepared to talk about how your future research can help bring in grants and other sources of funding, especially if you have a good track record of receiving awards and fellowships. Mention some grants that you know have been awarded to similar research, and state your intention to seek this type of funding.

Step 3: Ask faculty in your department if they are willing to share their own research statements with you. To a certain extent, there will be some subject-specific differences in what is expected from a research statement, and so it is always a good idea to see how others in your field have done it. You should try to draft your own research statement first before you review any statements shared with you. Your goal is to create a unique research statement that clearly highlights your abilities as a researcher.

Step 4: The research statement is typically a few (2-3) pages in length, depending on the number of images, illustrations, or graphs included. Once you have completed the steps above, schedule an appointment with a career advisor to get feedback on your draft. You should also try to get faculty in your department to review your document if they are willing to do so.

Explore other application documents:

Students & Educators —Menu

- Educational Resources

- Educators & Faculty

- College Planning

- ACS ChemClub

- Project SEED

- U.S. National Chemistry Olympiad

- Student Chapters

- ACS Meeting Information

- Undergraduate Research

- Internships, Summer Jobs & Coops

- Study Abroad Programs

- Finding a Mentor

- Two Year/Community College Students

- Social Distancing Socials

- Planning for Graduate School

- Grants & Fellowships

- Career Planning

- International Students

- Planning for Graduate Work in Chemistry

- ACS Bridge Project

- Graduate Student Organizations (GSOs)

- Schedule-at-a-Glance

- Standards & Guidelines

- Explore Chemistry

- Science Outreach

- Publications

- ACS Student Communities

- You are here:

- American Chemical Society

- Students & Educators

Writing the Research Plan for Your Academic Job Application

By Jason G. Gillmore, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Department of Chemistry, Hope College, Holland, MI

A research plan is more than a to-do list for this week in lab, or a manila folder full of ideas for maybe someday—at least if you are thinking of a tenure-track academic career in chemistry at virtually any bachelor’s or higher degree–granting institution in the country. A perusal of the academic job ads in C&EN every August–October will quickly reveal that most schools expect a cover letter (whether they say so or not), a CV, a teaching statement, and a research plan, along with reference letters and transcripts. So what is this document supposed to be, and why worry about it now when those job ads are still months away?

What Is a Research Plan?

A research plan is a thoughtful, compelling, well-written document that outlines your exciting, unique research ideas that you and your students will pursue over the next half decade or so to advance knowledge in your discipline and earn you grants, papers, speaking invitations, tenure, promotion, and a national reputation. It must be a document that people at the department you hope to join will (a) read, and (b) be suitably excited about to invite you for an interview.

That much I knew when I was asked to write this article. More specifics I only really knew for my own institution, Hope College (a research intensive undergraduate liberal arts college with no graduate program), and even there you might get a dozen nuanced opinions among my dozen colleagues. So I polled a broad cross-section of my network, spanning chemical subdisciplines at institutions ranging from small, teaching-centered liberal arts colleges to our nation’s elite research programs, such as Scripps and MIT. The responses certainly varied, but they did center on a few main themes, or illustrate a trend across institution types. In this article I’ll share those commonalities, while also encouraging you to be unafraid to contact a search committee chair with a few specific questions, especially for the institutions you are particularly excited about and feel might be the best fit for you.

How Many Projects Should You Have?

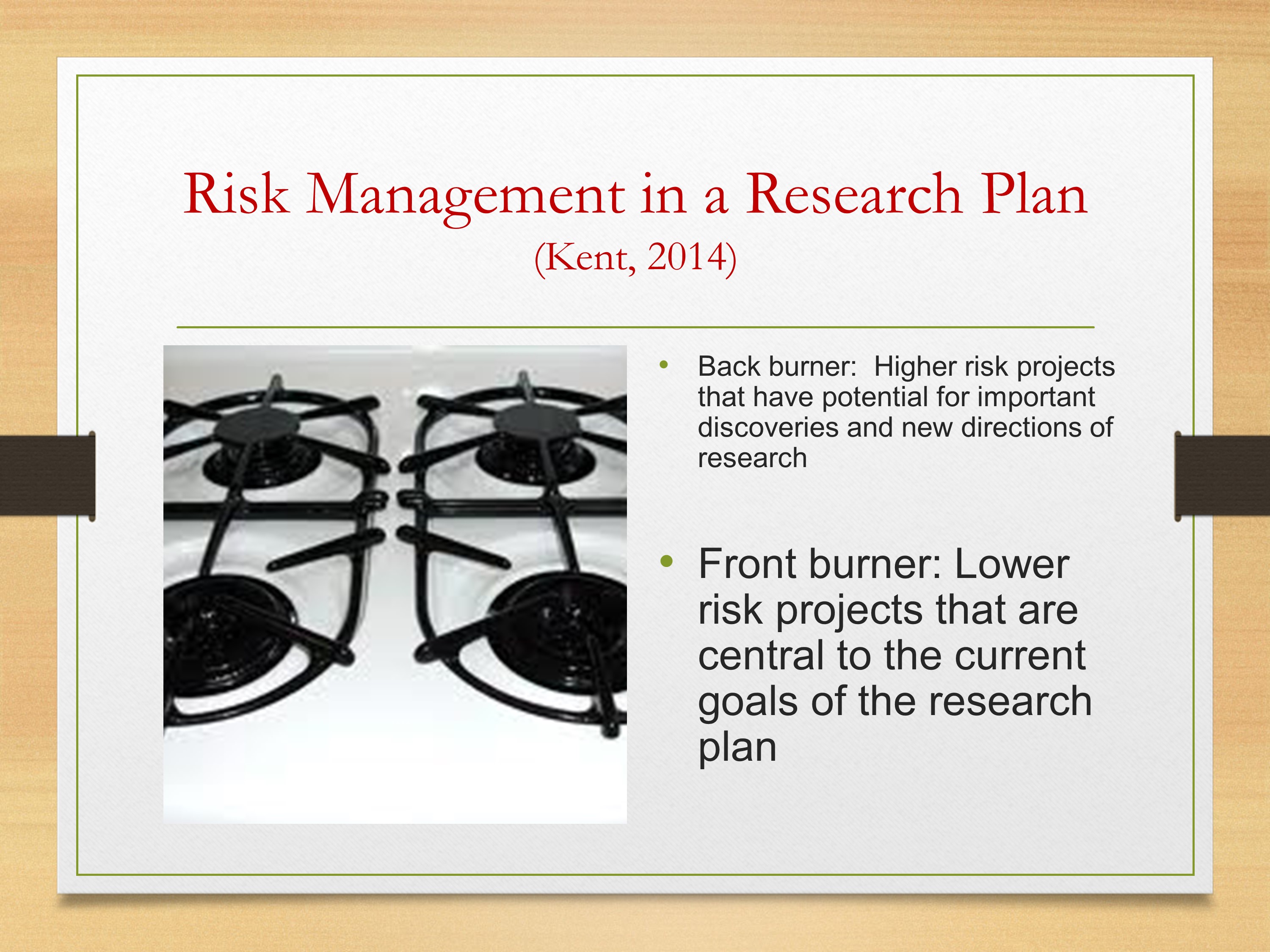

While more senior advisors and members of search committees may have gotten their jobs with a single research project, conventional wisdom these days is that you need two to three distinct but related projects. How closely related to one another they should be is a matter of debate, but almost everyone I asked felt that there should be some unifying technique, problem or theme to them. However, the projects should be sufficiently disparate that a failure of one key idea, strategy, or technique will not hamstring your other projects.

For this reason, many applicants wisely choose to identify:

- One project that is a safe bet—doable, fundable, publishable, good but not earthshaking science.

- A second project that is pie-in-the-sky with high risks and rewards.

- A third project that fits somewhere in the middle.

Having more than three projects is probably unrealistic. But even the safest project must be worth doing, and even the riskiest must appear to have a reasonable chance of working.

How Closely Connected Should Your Research Be with Your Past?

Your proposed research must do more than extend what you have already done. In most subdisciplines, you must be sufficiently removed from your postdoctoral or graduate work that you will not be lambasted for clinging to an advisor’s apron strings. After all, if it is such a good idea in their immediate area of interest, why aren’t they pursuing it?!?

But you also must be able to make the case for why your training makes this a good problem for you to study—how you bring a unique skill set as well as unique ideas to this research. The five years you will have to do, fund, and publish the research before crafting your tenure package will go by too fast for you to break into something entirely outside your realm of expertise.

Biochemistry is a partial exception to this advice—in this subdiscipline it is quite common to bring a project with you from a postdoc (or more rarely your Ph.D.) to start your independent career. However, you should still articulate your original contribution to, and unique angle on the work. It is also wise to be sure your advisor tells that same story in his or her letter and articulates support of your pursuing this research in your career as a genuinely independent scientist (and not merely someone who could be perceived as his or her latest "flunky" of a collaborator.)

Should You Discuss Potential Collaborators?

Regarding collaboration, tread lightly as a young scientist seeking or starting an independent career. Being someone with whom others can collaborate in the future is great. Relying on collaborators for the success of your projects is unwise. Be cautious about proposing to continue collaborations you already have (especially with past advisors) and about starting new ones where you might not be perceived as the lead PI. Also beware of presuming you can help advance the research of someone already in a department. Are they still there? Are they still doing that research? Do they actually want that help—or will they feel like you are criticizing or condescending to them, trying to scoop them, or seeking to ride their coattails? Some places will view collaboration very favorably, but the safest route is to cautiously float such ideas during interviews while presenting research plans that are exciting and achievable on your own.

How Do You Show Your Fit?

Some faculty advise tailoring every application packet document to every institution to which you apply, while others suggest tweaking only the cover letter. Certainly the cover letter is the document most suited to introducing yourself and making the case for how you are the perfect fit for the advertised position at that institution. So save your greatest degree of tailoring for your cover letter. It is nice if you can tweak a few sentences of other documents to highlight your fit to a specific school, so long as it is not contrived.

Now, if you are applying to widely different types of institutions, a few different sets of documents will certainly be necessary. The research plan that you target in the middle to get you a job at both Harvard University and Hope College will not get you an interview at either! There are different realities of resources, scope, scale, and timeline. Not that my colleagues and I at Hope cannot tackle research that is just as exciting as Harvard’s. However, we need to have enough of a niche or a unique angle both to endure the longer timeframe necessitated by smaller groups of undergraduate researchers and to ensure that we still stand out. Furthermore, we generally need to be able to do it with more limited resources. If you do not demonstrate that understanding, you will be dismissed out of hand. But at many large Ph.D. programs, any consideration of "niche" can be inferred as a lack of confidence or ambition.

Also, be aware that department Web pages (especially those several pages deep in the site, or maintained by individual faculty) can be woefully out-of-date. If something you are planning to say is contingent on something you read on their Web site, find a way to confirm it!

While the research plan is not the place to articulate start-up needs, you should consider instrumentation and other resources that will be necessary to get started, and where you will go for funding or resources down the road. This will come up in interviews, and hopefully you will eventually need these details to negotiate a start-up package.

Who Is Your Audience?

Your research plan should show the big picture clearly and excite a broad audience of chemists across your sub-discipline. At many educational institutions, everyone in the department will read the proposal critically, at least if you make the short list to interview. Even at departments that leave it all to a committee of the subdiscipline, subdisciplines can be broad and might even still have an outside member on the committee. And the committee needs to justify their actions to the department at large, as well as to deans, provosts, and others. So having at least the introduction and executive summaries of your projects comprehensible and compelling to those outside your discipline is highly advantageous.

Good science, written well, makes a good research plan. As you craft and refine your research plan, keep the following strategies, as well as your audience in mind:

- Begin the document with an abstract or executive summary that engages a broad audience and shows synergies among your projects. This should be one page or less, and you should probably write it last. This page is something you could manageably consider tailoring to each institution.

- Provide sufficient details and references to convince the experts you know your stuff and actually have a plan for what your group will be doing in the lab. Give details of first and key experiments, and backup plans or fallback positions for their riskiest aspects.

- Hook your readers with your own ideas fairly early in the document, then strike a balance between your own new ideas and the necessary well referenced background, precedents, and justification throughout. Propose a reasonable tentative timeline, if you can do so in no more than a paragraph or two, which shows how you envision spacing out the experiments within and among your projects. This may fit well into your executive summary

- Show how you will involve students (whether undergraduates, graduate students, an eventual postdoc or two, possibly even high schoolers if the school has that sort of outreach, depending on the institutions to which you are applying) and divide the projects among students.

- Highlight how your work will contribute to the education of these students. While this is especially important at schools with greater teaching missions, it can help set you apart even at research intensive institutions. After all, we all have to demonstrate “broader impacts” to our funding agencies!

- Include where you will pursue funding, as well as publication, if you can smoothly work it in. This is especially true if there is doubt about how you plan to target or "market" your research. Otherwise, it is appropriate to hold off until the interview to discuss this strategy.

So, How Long Should Your Research Plan Be?

Learn more on the Blog

Here is where the answers diverged the most and without a unifying trend across institutions. Bottom line, you need space to make your case, but even more, you need people to read what you write.

A single page abstract or executive summary of all your projects together provides you an opportunity to make the case for unifying themes yet distinct projects. It may also provide space to articulate a timeline. Indeed, many readers will only read this single page in each application, at least until winnowing down to a more manageable list of potential candidates. At the most elite institutions, there may be literally hundreds of applicants, scores of them entirely well-suited to the job.

While three to five pages per proposal was a common response (single spaced, in 11-point Arial or 12-point Times with one inch margins), including references (which should be accurate, appropriate, and current!), some of my busiest colleagues have said they will not read more than about three pages total. Only a few actually indicated they would read up to 12-15 pages for three projects. In my opinion, ten pages total for your research plans should be a fairly firm upper limit unless you are specifically told otherwise by a search committee, and then only if you have two to three distinct proposals.

Why Start Now?

Hopefully, this question has answered itself already! Your research plan needs to be a well thought out document that is an integrated part of applications tailored to each institution to which you apply. It must represent mature ideas that you have had time to refine through multiple revisions and a great deal of critical review from everyone you can get to read them. Moreover, you may need a few different sets of these, especially if you will be applying to a broad range of institutions. So add “write research plans” to this week’s to do list (and every week’s for the next few months) and start writing up the ideas in that manila folder into some genuine research plans. See which ones survive the process and rise to the top and you should be well prepared when the job ads begin to appear in C&EN in August!

Jason G. Gillmore , Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Chemistry at Hope College in Holland, MI. A native of New Jersey, he earned his B.S. (’96) and M.S. (’98) degrees in chemistry from Virginia Tech, and his Ph.D. (’03) in organic chemistry from the University of Rochester. After a short postdoctoral traineeship at Vanderbilt University, he joined the faculty at Hope in 2004. He has received the Dreyfus Start-up Award, Research Corporation Cottrell College Science Award, and NSF CAREER Award, and is currently on sabbatical as a Visiting Research Professor at Arizona State University. Professor Gillmore is the organizer of the Biennial Midwest Postdoc to PUI Professor (P3) Workshop co-sponsored by ACS, and a frequent panelist at the annual ACS Postdoc to Faculty (P2F) Workshops.

Other tips to help engage (or at least not turn off) your readers include:

- Avoid two-column formats.

- Avoid too-small fonts that hinder readability, especially as many will view the documents online rather than in print!

- Use good figures that are readable and broadly understandable!

- Use color as necessary but not gratuitously.

Accept & Close The ACS takes your privacy seriously as it relates to cookies. We use cookies to remember users, better understand ways to serve them, improve our value proposition, and optimize their experience. Learn more about managing your cookies at Cookies Policy .

1155 Sixteenth Street, NW, Washington, DC 20036, USA | service@acs.org | 1-800-333-9511 (US and Canada) | 614-447-3776 (outside North America)

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility

Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society

Faculty Application: Research Statement

Criteria for success.

- Clearly articulate your brand.

- Demonstrate the impact of your past work.

- Show that you are credible to carry out your proposed future research.

- Articulate the importance of your research vision.

- Match the standards within the department to which you are applying.

- Show that you are a good fit for the position.

- Polish. Avoid typos.

Structure Diagram

The typical structure and length of research statements vary widely across fields. If you are unsure of what is typical in the field where you are applying, be sure to check with someone who is familiar with the standards.

In electrical engineering and computer science, research statements are usually around three pages long with a focus on past and current work, often following the structure in the diagram below.

Identify Your Purpose

Your cover letter and CV outline your past work and hint at a general direction of your future work but do not go into detail. Therefore, the purpose of a research statement is to emphasize the importance of your past work and describe your research vision. Both your past/current work and future work presented in the research statement should reflect your branding statement .

In EECS, faculty research statements focus on past/current work. However, it is important to also include your vision for the future, which should build on your previous work. This statement should convince the committee that your future work is important, relevant, and feasible. The future work section should go beyond direct extensions of your doctoral or postdoctoral work; it should cover a 5-10 year span. Proposed future work should show scientific growth and convince the committee that you propose strong research directions for your future group. Your research statement can also include possible funding sources and collaborations.

Analyze Your Audience

Your audience is a faculty search committee, which is made up of professors from across the department, not just the ones in your research area. A typical search committee member is probably very busy reviewing lots of applications, and hence may not read your statement in depth until you make it to later rounds of the hiring process.

Knowing details of the job posting and what the faculty search committee is looking for will help you tailor your statement. If the call is for a specific research area (e.g., language processing, bioinformatics, algorithms, machine learning, systems), it is beneficial to motivate and emphasize the importance of your work in the language of that area whenever possible.

Structure your statement

Although there is usually no mandated structure for a research statement, it can be very helpful to a reader if the content flows naturally.

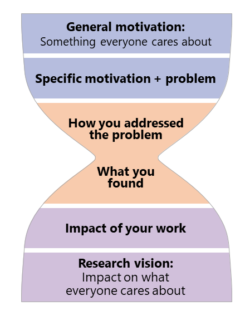

Use the hourglass concept. It makes a compelling introduction if a research statement presents motivation starting from the high-level picture and then zooms in to the main topic(s) of research. This is helpful for two reasons. First, a research statement is typically read by committee members from several research areas, so starting with a high-level picture gives members a gentle guidance to the meat of a work. Second, providing general motivation helps in showing how different pieces of research fit in a big puzzle.

After talking about specific results, the story typically zooms back out by discussing impact and future directions. It is best if future work has some concrete research directions and also widens up to touch on a broader perspective of research plans.

The diagram below summarizes the hourglass concept and provides one potential flow of content.

Use good formatting to help retain focus . A successful research statement is typically organized into three main parts: Introduction and motivation; past work/achievements; and vision/future work. Each of these parts can be divided into subsections.

In addition, you can help a reader focus their attention on the important content by:

- making each section/paragraph title tell a message;

- using bullet points and itemization while listing;

- using bold or italics to emphasize important keywords or sentences.

Some institutions set constraints on the format of research statements, primarily constraints on length . Make sure that your research statement is tailored to the guidelines. It is helpful to prepare two versions of your statement — a long one and a short one. The short version is usually the long one stripped of many details with the emphasis on high-level pictures and ideas.

Say who you are

Your research statement tells a story about you. Think who you want to be in the eyes of committee members (e.g., a programming languages person, a machine learning expert, a theory professor) and which of your achievements you want them to remember.

Make your research statement echo your branding one . A successful research statement builds a story around the author’s branding statement. A strong point is made if past and future work are echoes of the same brand.

Successful candidates outline their research agenda before stating actual results and after providing a background. Sometimes this is done even before giving background and motivation. In the latter case, the research agenda is typically stated briefly, and then reiterated with more context after providing the background.

Show credibility for your future work by your past work

Your past work is an excellent way to illustrate that you are fit for the future work you are proposing. Refer to some of your past work when outlining feasibility of your proposed future directions. Even if you aim to change your field of research, your past experience should still serve as a justification for why you are well suited for the new line of work.

Dedicate space to your strongest results . Describe your strongest results in the most detail. If you want to mention many papers, organize them into several themes. A successful statement communicates how obtained results affect a field or a research community. Impact of papers can be shown by awards, high number of citations, or follow up papers by other research groups. A reader will have limited time to go over your statement, so make sure that the reader’s attention is spent on your most impactful work. Note that your strongest results do not necessarily have to be your most recent ones; they can even be several years old. Nevertheless, it is still a good idea to also mention some of your recent work as it shows that you have been active lately as well.

Importantly, a research statement should be a coherent story about ideas and impact, not only an overview of published articles. Hence, it is often the case that a research statement does not discuss all papers published or all work done by the applicant.

Use figures to support important claims . Consider including figures . They can be used to support your claims about your results and/or in the future work section to illustrate your research plans. A well-made figure can help the reader quickly understand your work, but figures also take up a large amount of space. Use figures carefully, only to draw attention to the most important points.

Devote time!

Getting out a job application package takes an indefinitely long time (writing, addressing feedback, polishing, addressing feedback … aaaand polishing)! Start early and invest time.

Get feedback . Your application package will be read by committee members that are not necessarily in your research area. It is thus important to get feedback about your research statement from colleagues with different backgrounds and seniority. Note that it might take time for other people to share their feedback (remember, others are busy as well!), so plan ahead.

MIT EECS affiliates can also make an appointment with a Communication Fellow to obtain additional feedback on their statements.

Resources and Annotated Examples

Amy zhang research statement.

Submitted in 2018-2019 by Amy Zhang, now faculty at University of Washington 1 MB

Elena Glassman Research Statement

Submitted in 2017-2018 by Elena Glassman, now faculty at Harvard University 2 MB

- Enhancing Student Success

- Innovative Research

- Alumni Success

- About NC State

How to Construct a Compelling Research Statement

A research statement is a critical document for prospective faculty applicants. This document allows applicants to convey to their future colleagues the importance and impact of their past and, most importantly, future research. You as an applicant should use this document to lay out your planned research for the next few years, making sure to outline how your planned research contributes to your field.

Some general guidelines

(from Carleton University )

An effective research statement accomplishes three key goals:

- It clearly presents your scholarship in nonspecialist terms;

- It places your research in a broader context, scientifically and societally; and

- It lays out a clear road map for future accomplishments in the new setting (the institution to which you’re applying).

Another way to think about the success of your research statement is to consider whether, after reading it, a reader is able to answer these questions:

- What do you do (what are your major accomplishments; what techniques do you use; how have you added to your field)?

- Why is your work important (why should both other scientists and nonscientists care)?

- Where is it going in the future (what are the next steps; how will you carry them out in your new job; does your research plan meet the requirements for tenure at this institution)?

1. Make your statement reader-friendly

A typical faculty application call can easily receive 200+ applicants. As such, you need to make all your application documents reader-friendly. Use headings and subheadings to organize your ideas and leave white space between sections.

In addition, you may want to include figures and diagrams in your research statement that capture key findings or concepts so a reader can quickly determine what you are studying and why it is important. A wall of text in your research statement should be avoided at all costs. Rather, a research statement that is concise and thoughtfully laid out demonstrates to hiring committees that you can organize ideas in a coherent and easy-to-understand manner.

Also, this presentation demonstrates your ability to develop competitive funding applications (see more in next section), which is critical for success in a research-intensive faculty position.

2. Be sure to touch on the fundability of your planned research work

Another goal of your research statement is to make the case for why your planned research is fundable. You may get different opinions here, but I would recommend citing open or planned funding opportunities at federal agencies or other funders that you plan to submit to. You might also use open funding calls as a way to demonstrate that your planned research is in an area receiving funding prioritization by various agencies.

If you are looking for funding, check out this list of funding resources on my personal website. Another great way to look for funding is to use NIH Reporter and NSF award search .

3. Draft the statement and get feedback early and often

I can tell you from personal experience that it takes time to refine a strong research statement. I went on the faculty job market two years in a row and found my second year materials to be much stronger. You need time to read, review and reflect on your statements and documents to really make them stand out.

It is important to have your supervisor and other faculty read and give feedback on your critical application documents and especially your research statement. Also, finding peers to provide feedback and in return giving them feedback on their documents is very helpful. Seek out communities of support such as Future PI Slack to find peer reviewers (and get a lot of great application advice) if needed.

4. Share with nonexperts to assess your writing’s clarity

Additionally, you may want to consider sharing your job materials, including your research statement, with non-experts to assess clarity. For example, NC State’s Professional Development Team offers an Academic Packways: Gearing Up for Faculty program each year where you can get feedback on your application documents from individuals working in a variety of areas. You can also ask classmates and colleagues working in different areas to review your research statement. The more feedback you can receive on your materials through formal or informal means, the better.

5. Tailor your statement to the institution

It is critical in your research statement to mention how you will make use of core facilities or resources at the institution you are applying to. If you need particular research infrastructure to do your work and the institution has it, you should mention that in your statement. Something to the effect of: “The presence of the XXX core facility at YYY University will greatly facilitate my lab’s ability to investigate this important process.”

Mentioning core facilities and resources at the target institution shows you have done your research, which is critical in demonstrating your interest in that institution.

Finally, think about the resources available at the institution you are applying to. If you are applying to a primarily undergraduate-serving institution, you will want to be sure you propose a research program that could reasonably take place with undergraduate students, working mostly in the summer and utilizing core facilities that may be limited or require external collaborations.

Undergraduate-serving institutions will value research projects that meaningfully involve students. Proposing overly ambitious research at a primarily undergraduate institution is a recipe for rejection as the institution will read your application as out of touch … that either you didn’t do the work to research them or that you are applying to them as a “backup” to research-intensive positions.

You should carefully think about how to restructure your research statements if you are applying to both primarily undergraduate-serving and research-intensive institutions. For examples of how I framed my research statement for faculty applications at each type of institution, see my personal website ( undergraduate-serving ; research-intensive research statements).

6. Be yourself, not who you think the search committee wants

In the end, a research statement allows you to think critically about where you see your research going in the future. What are you excited about studying based on your previous work? How will you go about answering the unanswered questions in your field? What agencies and initiatives are funding your type of research? If you develop your research statement from these core questions, your passion and commitment to the work will surely shine through.

A closing thought: Be yourself, not who you think the search committee wants. If you try to frame yourself as someone you really aren’t, you are setting the hiring institution and you up for disappointment. You want a university to hire you because they like you, the work you have done, and the work you want to do, not some filtered or idealized version of you.

So, put your true self out there, and realize you want to find the right institutional fit for you and your research. This all takes time and effort. The earlier you start and the more reflection and feedback you get on your research statement and remaining application documents, the better you can present the true you to potential employers.

More Advice on Faculty Job Application Documents on ImPACKful

How to write a better academic cover letter

Tips on writing an effective teaching statement

More Resources

See here for samples of a variety of application materials from UCSF.

- Rules of the (Social Sciences & Humanities) Research Statement

- CMU’s Writing a Research Statement

- UW’s Academic Careers: Research Statements

- Developing a Winning Research Statement (UCSF)

- Academic Packways

- ImPACKful Tips

Leave a Response Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

More From The Graduate School

Advice From Newly Hired Assistant Professors

Virtual Postdoc Research Symposium Elevates and Supports Postdoctoral Scholars Across North Carolina

Expand Your Pack: Start or Join an Online Writing Group!

5 Simple Tips for Writing a Good Research Statement for a Faculty Position

Completed your Ph.D.? What next?

Traditionally, most sought-after jobs after completing Ph.D. are university professors and industry R&D labs professionals. While industrial jobs have seen a surge in applicants to various positions, academia has prominently been the most considered field by Ph.Ds. As a part of the job application for faculty positions in academia, applicants are required to present a research statement that outlines the research they have already completed.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Statement?

A research statement is a document that summarizes your research interests, accomplishments, current research, and future research conduction plans. Furthermore, it outlines how your work contributes to the field. It allows applicants to present the importance and impact of their past, current, and future research to their potential future colleagues. However, throughout your academic career, you may be asked to prepare similar documents for annual reviews, tenure packages, or promotion.

What is the Purpose of a Research Statement?

The purpose of a research statement isn’t just about exhibiting your research interests, achievement, or other academic feats. In fact, its purpose is to make a persuasive case about the importance of your completed work and the potential impact of your future trajectory in research. In other words, researchers must coherently write about their past and current research efforts and articulately present their future research plans.

Furthermore, a research statement’s purpose is to allow the search committee to envision the applicant’s research evolution, productivity, and potential contributions over the coming years. Your research statement must promisingly convey the benefits you bring to the position. In other words, these benefits could be in terms of grant money, faculty collaborations, student involvement in research, or development of new courses.

Three key purposes of a research statement are:

- Clear presentation of your academic feats.

- Description of your research in a broader context, both scientifically and societally.

- Laying out a clear road map for future endeavors concerning the newly applied position.

How is a Research Statement Different from a CV?

While your CV gives an overview of your past research projects, it does not address the details of conducted research or future research interests. Furthermore, a CV fails to answer some questions that can be easily answered through a research statement.

- Why are you interested in a particular research topic?

- Why is your research important?

- What techniques do you use?

- How have you contributed to your field?

- How can your research be applied commercially or academically?

- Does your research have an impact on allied fields?

- Is your research directing you to newer questions?

- How do you plan to develop new skills and knowledge?

What Should You Include in a Research Statement for Faculty Position?

With over hundreds of applications being received at various departments, your research statement must stand out from the crowd and address all points concerning the target position. Expectations for research statements may vary across disciplines. However, certain key elements must be included in a research statement, irrespective of the field.

- Academic specialty and interests.

- Dedication for research.

- Compatibility with departmental or university research efforts.

- Ideas about potential funding sources, collaborative partners, etc.

- Ability to work as a professional scholar.

- Capability to work as an independent researcher.

- Writing proficiency.

- Relevance of your research and its contribution to the field.

- Significant recognition received by your research such as publications, presentations, grants, awards, etc.

- Appropriate acknowledgment of other scholars’ work in your field by giving them credits where due.

- Degree of specificity for future research.

- Long-term and short-term research goals

How to Write a Research statement for Faculty Position?

An effective research statement must present a clear narrative of the relation between your past and current research. Additionally, it should clearly state how your research aligns with the goals, resources, and needs of the institution to which you are applying.

Here we discuss 5 simple tips for writing a good research statement:

As stated earlier, a faculty position may easily receive over a couple of hundred applications. Consequently, the search committee may just glance through some applications. Therefore, you must make your research statement reader-friendly.

Following tips will allow readers to quickly determine why should they select you over other applicants:

- Organize your ideas by using headings and sub-headings.

- Space out different sections properly.

- Additionally, include figures and diagrams to illustrate key findings or concepts.

- Avoid writing long paragraphs in your research statement. Moreover, a concise yet thoughtfully laid out research statement demonstrates your ability to organize ideas in a coherent and easy-to-understand manner.

2. Ensure to Present Your Focus on Research

- Discuss feasible research ideas that interest you.

- Explain how your goals are related to your recent work.

- Additionally, mention your short-term (2-5 years) and long-term (5+ years) research goals.

- Discuss your ideas about potential funding sources, collaborative partners, facilities, etc.

- Specifically mention how your research goals align with your department’s goals.

3. Tailor Your Research Statement

- It is imperative to mention how you will contribute to the research at the institution you are applying to.

- Mention how will you use core facilities or resources at the institution.

- Furthermore, you should mention particular research infrastructure present at the target institution that you may need to do your work.

4. Write for Each Audience

- Even at top-most institutions, not all members of the search committee may be aware of the intricacies of your research work. Therefore, you should avoid jargon and describe your research work in a detailed yet lucid manner.

- Your motive must be to instill a sense of belief in the reader that you are a dedicated researcher and not overwhelm them with finer details.

- Moreover, focus on conveying the importance of your work and its contribution to the field.

5. Be Yourself

In an attempt to impress the search committee, applicants are often seen to go overboard and come out as boastful.

- Emphasize your major academic achievements.

- Be realistic and do not present research goals that are too ambitious.

- Finally, avoid comparing your research statement with other applicants.

Did you decide on the faculty position you want to apply for? How do you plan to go ahead with your research statement? Follow these tips while writing your research statement to acquire your most desired faculty position .

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Trending Now

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

In a bustling university town, there lived a student named Alex. Popular for creativity and…

- Career Corner

- Diversity and Inclusion

- PhDs & Postdocs

Mentoring for Change: Creating an inclusive academic landscape through support programs

Imagine stepping into a world where everyone’s unique talents and backgrounds are not only recognized…

Mentoring for Change: Creating an inclusive academic landscape through support…

Reviving Your Research Career: Overcoming the roadblocks of resuming research after a…

Aiming for Academic Tenure? – 5 Things You Should Know Before Applying!

Statement of Purpose Vs. Personal Statement – A Guide for Early Career…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

- Undergraduate Students

- Masters Students

- PhD/Doctoral Students

- Postdoctoral Scholars

- Faculty & Staff

- Families & Supporters

- Prospective Students

- Explore Your Interests / Self-Assessment

- Build your Network / LinkedIn

- Search for a Job / Internship

- Create a Resume / Cover Letter

- Prepare for an Interview

- Negotiate an Offer

- Prepare for Graduate School

- Find Funding Opportunities

- Prepare for the Academic Job Market

- Search for a Job or Internship

- Advertising, Marketing, and Public Relations

- Arts & Entertainment

- Consulting & Financial Services

- Engineering & Technology

- Government, Law & Policy

- Hospitality

- Management & Human Resources

- Non-Profit, Social Justice & Education

- Retail & Consumer Services

- BIPOC Students & Scholars

- Current & Former Foster Youth

- Disabled Students & Scholars

- First-Generation Students & Scholars

- Formerly Incarcerated Students & Scholars

- International Students & Scholars

- LGBTQ+ Students & Scholars

- Students & Scholars with Dependents

- Transfer Students

- Undocumented Students & Scholars

- Women-Identifying Students & Scholars

Research Statements

- Share This: Share Research Statements on Facebook Share Research Statements on LinkedIn Share Research Statements on X

A research statement is used when applying for some academic faculty positions and research-intensive positions. A research statement is usually a single-spaced 1-2 page document that describes your research trajectory as a scholar, highlighting growth: from where you began to where you envision going in the next few years. Ultimately, research productivity, focus and future are the most highly scrutinized in academic faculty appointments, particularly at research-intensive universities. Tailor your research statement to the institution to which you are applying – if a university has a strong research focus, emphasize publications; if a university values teaching and research equally, consider ending with a paragraph about how your research complements your teaching and vice versa. Structures of these documents also varies by discipline. See two common structures below.

Structure One:

Introduction: The first paragraph should introduce your research interests in the context of your field, tying the research you have done so far to a distinct trajectory that will take you well into the future.

Summary Of Dissertation: This paragraph should summarize your doctoral research project. Try not to have too much language repetition across documents, such as your abstract or cover letter.

Contribution To Field And Publications: Describe the significance of your projects for your field. Detail any publications initiated from your independent doctoral or postdoctoral research. Additionally, include plans for future publications based on your thesis. Be specific about journals to which you should submit or university presses that might be interested in the book you could develop from your dissertation (if your field expects that). If you are writing a two-page research statement, this section would likely be more than one paragraph and cover your future publication plans in greater detail.

Second Project: If you are submitting a cover letter along with your research statement, then the committee may already have a paragraph describing your second project. In that case, use this space to discuss your second project in greater depth and the publication plans you envision for this project. Make sure you transition from your dissertation to your second large project smoothly – you want to give a sense of your cohesion as a scholar, but also to demonstrate your capacity to conceptualize innovative research that goes well beyond your dissertation project.

Wider Impact Of Research Agenda: Describe the broader significance of your work. What ties your research projects together? What impact do you want to make on your field? If you’re applying for a teaching-oriented institution, how would you connect your research with your teaching?

Structure Two:

25% Previous Research Experience: Describe your early work and how it solidified your interest in your field. How did these formative experiences influence your research interests and approach to research? Explain how this earlier work led to your current project(s).

25% Current Projects: Describe your dissertation/thesis project – this paragraph could be modeled on the first paragraph of your dissertation abstract since it covers all your bases: context, methodology, findings, significance. You could also mention grants/fellowships that funded the project, publications derived from this research, and publications that are currently being developed.

50% Future Work: Transition to how your current work informs your future research. Describe your next major project or projects and a realistic plan for accomplishing this work. What publications do you expect to come out of this research? The last part of the research statement should be customized to demonstrate the fit of your research agenda with the institution.

/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="how to write a research plan for faculty position"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Research statement, what is a research statement.

The research statement (or statement of research interests) is a common component of academic job applications. It is a summary of your research accomplishments, current work, and future direction and potential of your work.

The statement can discuss specific issues such as:

- funding history and potential

- requirements for laboratory equipment and space and other resources

- potential research and industrial collaborations

- how your research contributes to your field

- future direction of your research

The research statement should be technical, but should be intelligible to all members of the department, including those outside your subdiscipline. So keep the “big picture” in mind. The strongest research statements present a readable, compelling, and realistic research agenda that fits well with the needs, facilities, and goals of the department.

Research statements can be weakened by:

- overly ambitious proposals

- lack of clear direction

- lack of big-picture focus

- inadequate attention to the needs and facilities of the department or position

Why a Research Statement?

- It conveys to search committees the pieces of your professional identity and charts the course of your scholarly journey.

- It communicates a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be different, important, and innovative.

- It gives a context for your research interests—Why does your research matter? The so what?

- It combines your achievements and current work with the proposal for upcoming research.

- areas of specialty and expertise

- potential to get funding

- academic strengths and abilities

- compatibility with the department or school

- ability to think and communicate like a serious scholar and/or scientist

Formatting of Research Statements

The goal of the research statement is to introduce yourself to a search committee, which will probably contain scientists both in and outside your field, and get them excited about your research. To encourage people to read it:

- make it one or two pages, three at most

- use informative section headings and subheadings

- use bullets

- use an easily readable font size

- make the margins a reasonable size

Organization of Research Statements

Think of the overarching theme guiding your main research subject area. Write an essay that lays out:

- The main theme(s) and why it is important and what specific skills you use to attack the problem.

- A few specific examples of problems you have already solved with success to build credibility and inform people outside your field about what you do.

- A discussion of the future direction of your research. This section should be really exciting to people both in and outside your field. Don’t sell yourself short; if you think your research could lead to answers for big important questions, say so!

- A final paragraph that gives a good overall impression of your research.

Writing Research Statements

- Avoid jargon. Make sure that you describe your research in language that many people outside your specific subject area can understand. Ask people both in and outside your field to read it before you send your application. A search committee won’t get excited about something they can’t understand.

- Write as clearly, concisely, and concretely as you can.

- Keep it at a summary level; give more detail in the job talk.

- Ask others to proofread it. Be sure there are no spelling errors.

- Convince the search committee not only that you are knowledgeable, but that you are the right person to carry out the research.

- Include information that sets you apart (e.g., publication in Science, Nature, or a prestigious journal in your field).

- What excites you about your research? Sound fresh.

- Include preliminary results and how to build on results.

- Point out how current faculty may become future partners.

- Acknowledge the work of others.

- Use language that shows you are an independent researcher.

- BUT focus on your research work, not yourself.

- Include potential funding partners and industrial collaborations. Be creative!

- Provide a summary of your research.

- Put in background material to give the context/relevance/significance of your research.

- List major findings, outcomes, and implications.

- Describe both current and planned (future) research.

- Communicate a sense that your research will follow logically from what you have done and that it will be unique, significant, and innovative (and easy to fund).

Describe Your Future Goals or Research Plans

- Major problem(s) you want to focus on in your research.

- The problem’s relevance and significance to the field.

- Your specific goals for the next three to five years, including potential impact and outcomes.

- If you know what a particular agency funds, you can name the agency and briefly outline a proposal.

- Give broad enough goals so that if one area doesn’t get funded, you can pursue other research goals and funding.

Identify Potential Funding Sources

- Almost every institution wants to know whether you’ll be able to get external funding for research.

- Try to provide some possible sources of funding for the research, such as NIH, NSF, foundations, private agencies.

- Mention past funding, if appropriate.

Be Realistic

There is a delicate balance between a realistic research statement where you promise to work on problems you really think you can solve and over-reaching or dabbling in too many subject areas. Select an over-arching theme for your research statement and leave miscellaneous ideas or projects out. Everyone knows that you will work on more than what you mention in this statement.

Consider Also Preparing a Longer Version

- A longer version (five–15 pages) can be brought to your interview. (Check with your advisor to see if this is necessary.)

- You may be asked to describe research plans and budget in detail at the campus interview. Be prepared.

- Include laboratory needs (how much budget you need for equipment, how many grad assistants, etc.) to start up the research.

Samples of Research Statements

To find sample research statements with content specific to your discipline, search on the internet for your discipline + “Research Statement.”

- University of Pennsylvania Sample Research Statement

- Advice on writing a Research Statement (Plan) from the journal Science

This website uses cookies to improve your user experience. By continuing to use the site, you are accepting our use of cookies. Read the ACS privacy policy.

- ACS Publications

Writing the Research Plan for Your Academic Job Application

- Sep 8, 2017

Want to get that academic faculty job you’ve been dreaming about? Are you stressed about writing a lengthy research plan as part of the application process? Do not fear. ACS can provide you with guidance on writing a remarkable research plan needed for your academic job application so that you can stand out among other […]

Want to get that academic faculty job you’ve been dreaming about? Are you stressed about writing a lengthy research plan as part of the application process? Do not fear. ACS can provide you with guidance on writing a remarkable research plan needed for your academic job application so that you can stand out among other job applicants.

The mobile-friendly eBook entitled “ Writing the Research Plan for Your Academic Job Application ” includes tips on how to:

- Tailor your application for each school: Make sure you look at the guidelines that your university requires for the application. If your application matches the qualities of the type of candidate they want, the more likely you will be selected for the desired position. (i.e. Shania is applying to a university and sees that their “Desired Qualifications” list says they want someone who has a Bachelor of Science degree in Chemistry and knowledge using a certain type of equipment. When she includes this experience on her application, the recruiter will prioritize her as one of the top candidates.)

- Craft your research plan with your audience in mind: The audience reading your research plan will make or break your fate in getting your dream job. If the research plan grabs their attention, it will increase your chances of being hired. (i.e., Britney is starting to write her research plan and begins it with an engaging introduction and provides sufficient details that demonstrate her expertise in the field. If her goal and plan of execution intrigues the audience, she will become a standout candidate.)

- Determine the length of your plan: The recommended length for a research plan is ten pages. Additionally, you should have a proposal that is 3-5 pages long, which would serve as a summary of your roles and responsibilities if/when hired.

Want to show hiring managers that you’re the most qualified candidate? Download your free eBook to learn what it takes to write an effective research plan for your academic job application!

Want the latest stories delivered to your inbox each month?

- DACA/Undocumented

- First Generation, Low Income

- International Students

- Students of Color

- Students with disabilities

- Undergraduate Students

- Master’s Students

- PhD Students

- Faculty/Staff

- Family/Supporters

- Career Fairs

- Post Jobs, Internships, Fellowships

- Build your Brand at MIT

- Recruiting Guidelines and Resources

- Connect with Us

- Career Advising

- Distinguished Fellowships

- Employer Relations

- Graduate Student Professional Development

- Prehealth Advising

- Student Leadership Opportunities

- Academia & Education

- Architecture, Planning, & Design

- Arts, Communications, & Media

- Business, Finance, & Fintech

- Computing & Computer Technology

- Data Science

- Energy, Environment, & Sustainability

- Life Sciences, Biotech, & Pharma

- Manufacturing & Transportation

- Health & Medical Professions

- Social Impact, Policy, & Law

- Getting Started & Handshake 101

- Exploring careers

- Networking & Informational Interviews

- Connecting with employers

- Resumes, cover letters, portfolios, & CVs

- Finding a Job or Internship

- Post-Graduate and Summer Outcomes

- Professional Development Competencies

- Preparing for Graduate & Professional Schools

- Preparing for Medical / Health Profession Schools

- Interviewing

- New jobs & career transitions

- Career Prep and Development Programs

- Employer Events

- Outside Events for Career and Professional Development

- Events Calendar

- Career Services Workshop Requests

- Early Career Advisory Board

- Peer Career Advisors

- Student Staff

- Mission, Vision, Values and Diversity Commitments

- News and Reports

Application Materials for a Faculty Job Search

- Share This: Share Application Materials for a Faculty Job Search on Facebook Share Application Materials for a Faculty Job Search on LinkedIn Share Application Materials for a Faculty Job Search on X

The following materials are commonly requested. We encourage you to schedule an appointment with a career advisor to review your documents and discuss your plan. Get additional feedback on your materials from your faculty advisor and other mentors.

1) CV (curriculum vitae) : comprehensive scholarly record, including your research experience, teaching and mentoring experience, publication record, and more. See more details on preparing a CV .

2) Cover letter : 1-2 page letter, addressed to search committee. Include a brief summary of your academic background, highlights of past and future research, summary of teaching experiences and interests, and your fit with the department and school (why are you interested in that position? How does your experience match the position ad?)

3) Research Statement: A summary of your past research accomplishments, and a proposal for your future research plan as a faculty member. Include both your long-term vision, as well as concrete projects for your research group for the first 3-5 years. Length varies, but typically 3-6 pages. See more advice on writing research statements .

4) Teaching Statement : A statement of your approaches and philosophy regarding teaching and learning. Include specific examples to illustrate your approaches from your past teaching experience, or propose specific ideas for how you would teach future courses. Include a statement of the broad courses you are qualified to teach, as well as any courses you would like to develop. Usually 1-2 pages. See more advice on writing teaching statements .

5) Diversity Statement : A discussion of your past, present and future contributions to promoting equity, inclusion and diversity in your professional career. Typically 1-2 pages. See sample guidelines for writing a diversity statement .

RESOURCES FOR: Job Seekers Faculty Employers

RESOURCES FOR:

Job Seekers Faculty Employers

How to Write a Research Statement

By Sarah Hildebrand

Photo by Nick Youngson on Alpha Stock Images

Research statements have become a core component of faculty job applications. A research statement is a map for your career as a researcher, expanding on how you describe your research in your cover letter. A research statement should document a three- to five-year plan that lays out attainable goals. It should explain your past, present, and future research projects, as well as any major accomplishments. Make sure to highlight your strengths and the importance of your future work, but be realistic about what you can achieve—search committees will know the difference.

Tips and Considerations for Writing an Effective Research Statement

The length of a research statement varies by discipline. Although the average is three pages, it may be slightly shorter (1-2 pages) in the humanities or slightly longer (3-4 pages) in the social sciences and STEM fields.

Organization

Research statements begin with an introductory paragraph that describes your overall work and field, followed by body paragraphs that narrow down into your specific area of expertise and projects.

While some research statements are organized topically by project, most are ordered chronologically. Begin by discussing any past work, such as your dissertation; next describe any current research projects; end with ideas you have for the future. Some applicants may choose to use headings to further delineate among projects or clarify whether certain paragraphs focus on past, present, or future work.

Depending on your discipline, you may choose to include an executive summary at the end of your statement, which summarizes your main research goals, methodology, and qualifications for the position. STEM students may also incorporate relevant graphics that help clearly demonstrate results at a glance.

Research statements should be written for generalists who would make up a search committee. Contextualize your work within your field, avoid jargon, and make sure your work can be understood across your discipline.

Avoid long paragraphs. Paragraphs should never take up more than half a page and may be even shorter. If you have a lot to say about one particular project, that section might be broken up into 2-3 paragraphs to help keep your reader engaged.

Research statements should be written in the first-person and in the active voice. Both of these rhetorical strategies will ensure that you remain the focus of the statement. Your writing should be clear, concise, and assertive.

Example of passive vs. active voice:

Passive voice: The data was collected over a series of three experiments.

Active voice: I collected the data over a series of three experiments.

Topics to Cover in Your Research Statement

The subject and importance of your research.

Describe your general interest area, specific areas of expertise, and methodologies. Explain exactly what your research is and why it matters. How is your work innovative? What contribution does it make to existing bodies of knowledge? What major problems will you solve?

Past, Current, and Future Research Projects

Search committees expect you to discuss multiple projects. While you will certainly spend a paragraph or two on your dissertation, you should also have additional works-in-progress, as well as two or three defined projects you will conduct in the future. You can also describe any projects you’ve completed in the past. Be sure to draw connections between projects and demonstrate how your future work will build off the work you’ve already done. This will help prove that the project is feasible and that you are qualified to lead it.

Major Accomplishments

Describe any publications you have in a sentence or two by explaining what knowledge they contribute to the field. You should also acknowledge any major grants received, sources of funding secured, or awards won.

Additional Considerations for STEM Applicants

In a research statement, STEM applicants must demonstrate that their work is independent from the work of their PI. It may be helpful to describe how you will involve students of your own in your lab. If you require lab equipment and/or support staff, make sure all of your planned research can be accommodated by the institution as is, or identify how you will secure funding to obtain additional resources. Identify potential sources of external funding for your work, as well as potential collaborators within the department, school, or industry. Try to be as specific as possible by naming particular organizations or researchers.

This entry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

Related Posts

- How to Write a Diversity Statement

- How to Write a Teaching Statement

Need help with the Commons?

Email us at [email protected] so we can respond to your questions and requests. Please email from your CUNY email address if possible. Or visit our help site for more information:

- Terms of Service

- Accessibility

- Creative Commons (CC) license unless otherwise noted

Humans To Robots Laboratory

Empowering every person with a collaborative robot, writing a research statement for graduate school and fellowships.

Writing a research statement happens many times throughout a research career. Often for the first time it happens when applying to Ph.D. programs or applying to fellowships. Later, you will be writing postdoc and faculty applications. These documents are challenging to write because they seek to capture your entire research career in one document that may be read in 90 seconds or less.

Think of the research statement as a proposal. Whether you are applying for a Ph.D. program or for a faculty position, you are trying to convince the reader to invest in you. To decide whether to make this investment they need to know three things: 1) what will you do with the investment, 2) why is that an important problem ? and 3) what evidence is there that you will be successful in achieving the goals that you have set out.