- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

All-nighters and self-doubt: learn from our dissertation disasters

Recent graduates recall their dissertation slip-ups and share their advice on supervisors, footnotes and steering clear of the pub

I t’s likely to be the greatest academic challenge you’ll face as a student. Speak to a finalist working in the library at the moment and you’ll see from their gaunt and despairing facial expression that writing a thesis is not a fun thing to do.

These students take us through their hair-raising experiences - and share their tips for success.

I got the flu, and had to pull three all-nighters in a row

The dissertation was “a long, arduous process” for William Lloyd, a recent journalism graduate at Kingston University. “I caught the flu for the second time in my life, a week before it was due. That wasn’t ideal because I’d not really organised my time properly.

“True to form, I had left half of it to write with a few days left. I got a small extension due to the illness but had travel back to uni from home and do three all-nighters in a row at the library in order to get it done. Bloody hell, it took its toll.

“Whatever happens, my advice is not to panic. It was quite fun, in a way.”

My supervisor told me I was ‘not a scholar’

Cat Soave, a recent English literature graduate from the University of York, says: “I immediately encountered problems with my dissertation supervisor. They decided that I couldn’t write about the topic I had spent three years of education working up to. Their rationale was that I was “not a scholar” and would be unable to do adequate research for my topic.

“I was incredibly disappointed, and had to begin my research from scratch. In later meetings, I didn’t feel confident enough to be very vocal for fear of further criticism. I ended up completing my dissertation with next to no help or direction.”

What can we draw from Cat’s experience? It’s important to build a good relationship with your supervisor or try to find a different one if it clearly isn’t going to work.

Avoid unnecessary tinkering

Alys Key, a third-year English literature and language student at the University of Oxford, says: “The biggest problem I had with my dissertation was the final stages of drafting. The more I read it, the more it seemed to have problems, even if I’d been happier at an earlier stage.

“I think the key is to set yourself a cut-off point, at least a day or two before the deadline, and just limit yourself to proofreading. Everything seems bad when you’ve read it 100 times, so you have to have a bit of faith.”

I should have looked for more interesting research material

“Looking back, I should have researched more broadly,” says Emma Guest, an English literature and film studies graduate from Worcester University.

“I wrote my dissertation on two films by Guillermo del Toro. When I was looking for secondary reading to support my essay, I mainly focused on finding books on the topic. I think some people don’t realise that there are more interesting forms of secondary reading out there – such as archived papers, documentaries, and so on.”

Different tutors wanted different things - and some didn’t care

For Rupert McCallum, 21, a third-year biological sciences student at the University of Portsmouth, formatting his essay became an obstacle. “Different tutors within the department wanted different things - and some didn’t care,” he says.

“My advice would be to read up early on how to format your essay in case it becomes a pain closer to the deadline. Then double check, especially if the department is sending mixed messages. Although some of it may seem silly, sometimes it’s best just to jump through the hoops.”

I found it was easy to get sidetracked

Jessica Shales studied Anglo Saxon, Norse, and Celtic at the University of Cambridge – a specialist subject that can be difficult to research. “I found it was quite easy to become sidetracked, and to start reading lots in detail about stuff that wasn’t directly related to my question. If I were to start again, I think I would want to keep my overall aim more clearly in mind,” she says.

“I would also start writing it later than I did. I think I panicked a bit and wanted to get something down on paper, and so my argument wasn’t properly formed when I started writing. I think I was a bit scared by the fact that the dissertation was longer than anything I’d written before.

“I suppose my advice is to do whatever you’d try to do in a shorter essay, which is to pose a question, use relevant evidence to discuss it, and arrive at a conclusion accordingly.”

There’s nothing quite so soul-destroying as losing a page reference

Kate Wallis, 21, who studies arts and siences at University College London (UCL), learned the hard way to reference as she went along. “And I mean really reference, with page numbers. I cannot emphasise this enough.

“There’s nothing quite so soul-destroying as a stack of 20 books next to you that you have to go through to work out which elusive page your trifling statistic came from,” she says. “It’s advice that probably applies to all essay writing , but the dissertation is where it really comes to the fore.”

Top tip: don’t drink and dissertate

Don’t follow the example of William Buck, 21, who studied history at Cardiff University. “A desire to be in the pub let me down a bit. I was out at a night club about five times a week,” he says.

Keep up with the latest on Guardian Students: follow us on Twitter at @GdnStudents – and become a member to receive exclusive benefits and our weekly newsletter.

- Guardian Students

- Higher education

- Advice for students

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Emotional Eating in College Students: Associations with Coping and Healthy Eating Motivators and Barriers

- Full length manuscript

- Published: 29 June 2023

Cite this article

- Elizabeth D. Dalton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4013-6450 1

1079 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Emotional eating, or eating in response to stress and other negative affective states, bears negative consequences including excessive weight gain and heightened risk of binge eating disorder. Responding to stress with emotional eating is not universal, and it is important to elucidate under what circumstances and by what mechanisms stress is associated with emotional eating. This is particularly important to understand among college students, who are at risk of experiencing heightened stress and negative changes to dietary habits.

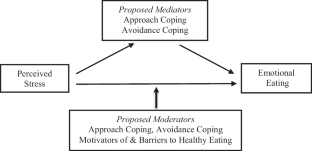

The present study investigated the relationships among perceived stress, emotional eating, coping, and barriers to and motivators of healthy eating both concurrently and 1 year later in a sample of young adult college students ( n = 232).

At baseline, emotional eating was significantly associated with perceived stress ( r = 0.36, p < .001), barriers to ( r = 0.31, p < .001) and motivators of ( r = − 0.14, p < .05) healthy eating, and avoidance coping ( r = 0.37, p < .001), but not approach coping. Furthermore, avoidance coping mediated (indirect effect b = 0.36, 95% CI = 0.13, 0.61) and moderated ( b = − 0.07, p = 0.04) the relationship between perceived stress and emotional eating. Contrary to study hypotheses, baseline stress levels were not associated with emotional eating 1 year later.

College students who utilize avoidance coping strategies may be particularly susceptible to the effects of stress on emotional eating. Healthy eating interventions targeting college students might address stress coping strategies in addition to reduction of barriers to healthy eating.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Cognitive–behavioral therapy for management of mental health and stress-related disorders: Recent advances in techniques and technologies

Mutsuhiro Nakao, Kentaro Shirotsuki & Nagisa Sugaya

Self-Compassion and Bedtime Procrastination: an Emotion Regulation Perspective

Fuschia M. Sirois, Sanne Nauts & Danielle S. Molnar

Self-Compassion Interventions and Psychosocial Outcomes: a Meta-Analysis of RCTs

Madeleine Ferrari, Caroline Hunt, … Danielle A. Einstein

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Martins BG, da Silva WR, Maroco J, Campos JA. Eating behaviors of Brazilian college students: influences of lifestyle, negative affectivity, and personal characteristics. Percept Mot Skills. 2021;128(2):781–99.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Moss RH, Conner M, O’Connor DB. Exploring the effects of positive and negative emotions on eating behaviours in children and young adults. Psychol Health Med. 2020;26(4):457–66.

Schmalbach I, Herhaus B, Pässler S, Schmalbach B, Berth H, Petrowski K. Effects of stress on chewing and food intake in patients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(7):1160–70.

Hennegan JM, Loxton NJ, Mattar A. Great expectations. Eating expectancies as mediators of reinforcement sensitivity and eating. Appetite. 2013;71:81–88.

Moss RH, Conner M, O’Connor DB. Exploring the effects of daily hassles and uplifts on eating behaviour in young adults: the role of daily cortisol levels. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;117.

Wu Y-K, Zimmer C, Munn-Chernoff MA, Baker JH. Association between food addiction and body dissatisfaction among college students: the mediating role of eating expectancies. Eat Behav. 2020;39: 101441.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hermes G, Fogelman N, Seo D, Sinha R. Differential effects of recent versus past traumas on mood, social support, binge drinking, emotional eating and BMI, and on neural responses to acute stress. Stress: Int J Biol Stress. 2021;17:1–10.

Ling J, Zahry NR. Relationships among perceived stress, emotional eating, and dietary intake in college students: eating self-regulation as a mediator. Appetite. 2021;163.

Longmire-Avital B, McQueen C. Exploring a relationship between race-related stress and emotional eating for collegiate Black American women. Women Health. 2019;59(3):240–51.

Barnhart WR, Braden AL, Jordan AK. Negative and positive emotional eating uniquely interact with ease of activation, intensity, and duration of emotional reactivity to predict increased binge eating. Appetite. 2020;151: 104688.

Diggins A, Woods-Giscombe C, Waters S. The association of perceived stress, contextualized stress, and emotional eating with body mass index in college-aged Black women. Eat Behav. 2015;19:188–92.

Altheimer G, Urry HL. Do emotions cause eating? The role of previous experiences and social context in emotional eating. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2019;28(3):234–40.

Article Google Scholar

Klatzkin RR, Nolan LJ, Kissileff HR. Self-reported emotional eaters consume more food under stress if they experience heightened stress reactivity and emotional relief from stress upon eating. Physiol Behav. 2022;243.

American College Health Association. “National College Health Assessment III: Undergraduate Student Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2021.” https://www.acha.org/NCHA/ACHA-NCHA_Data/Publications_and_Reports/NCHA/Data/Reports_ACHA-NCHAIIc.aspx . Accessed August 3rd, 2021.

Charles NE, Strong SJ, Burns LC, Bullerjahn MR, Serafine KM. Increased mood disorder symptoms, perceived stress, and alcohol use among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021;296.

Ulrich AK, Full KM, Cheng B, Gravagna K, Nederhoff D, Basta NE. Stress, anxiety, and sleep among college and university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Health. 2021;1–5.

Krendl AC. Changes in stress predict worse mental health outcomes for college students than does loneliness; evidence from the covid-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Health. 2021;1–4.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Vigorous physical activity, perceived stress, sleep and mental health among university students from 23 low- and middle-income countries. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2020;32(2):1–7.

Google Scholar

Wu D, Yang T. Late bedtime, uncertainty stress among Chinese college students: impact on academic performance and self-rated health. Psychol Health Med. 2022;1–12.

Koda S, Sugawara K. The influence of diet behavior and stress on binge-eating among female college students. Jpn J Psychol. 2009;80(2):83–9.

Miedema MD, Petrone A, Shikany JM, et al. Association of fruit and vegetable consumption during early adulthood with the prevalence of coronary artery calcium after 20 years of follow-up: The coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Circulation. 2015;132(21):1990–8.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Winpenny EM, van Slujis EMF, White M, Klepp K-I, Wold B, Lien N. Changes in diet through adolescence and early adulthood: longitudinal trajectories and association with key life transitions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15.

LaCaille LJ, Dauner KN, Krambeer RJ, Pedersen J. Psychosocial and environmental determinants of eating behaviors, physical activity, and weight change among college students: A qualitative analysis. J Am Coll Health. 2011;59(6):531–8.

Poobalan AS, Aucot LS, Clarke A, Smith WC. Diet behaviour among young people in transition to adulthood (18–25 year olds): a mixed method study. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2014;2(1):909–28.

Sogari G, Velez-Argumedo C, Gómez MI, Mora C. College students and eating habits: a study using an ecological model for healthy behavior. Nutrients. 2018;10(12):1823.

Hilger J, Loerbroks A, Diehl K. Eating behaviour of university students in Germany: dietary intake, barriers to healthy eating and changes in eating behaviour since the time of matriculation. Appetite. 2017;109:100–7.

Aljasem LI, Peyrot M, Wissow L, Rubin RR. The impact of barriers and self efficacy on self-care behaviors in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2001;27(3):393–404.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Fitzgerald A, Heary C, Kelly C, Nixon E, Shevlin M. Self-efficacy for healthy eating and peer support for unhealthy eating are associated with adolescents’ food intake patterns. Appetite. 2013;63(1):48–58.

Zajacova A, Lynch SM, Espenshad TJ. Self-efficacy, stress, and academic success in college. Res High Educ. 2005;46:677–706.

Moos RH. Coping responses inventory: a measure of approach and avoidance coping skills. In: Zalaquett CP, Wood RJ, editors. Evaluating stress: a book of resources. University of Michigan: Scarecrow Press; 1997. p. 51–65.

Gustems-Carnicer J, Calderón C. Virtues and character strengths related to approach coping strategies of college students. Social Psychol Educ. 2016;19(1):77–95.

Moos RH. Coping responses inventory: adult form: professional manual. Odessa: PAR Inc.; 1993.

Konaszewski K, Kolemba M, Niesiobędzka M. Resilience, sense of coherence and self-efficacy as predictors of stress coping style among university students. Curr Psychol. 2021;40(8):4052–62.

Spoor STP, Bekker MHJ, Van Strien T, van Heck GL. Relations between negative affect, coping, and emotional eating. Appetite. 2007;48(3):368–76.

Yönder Ertem M, Karakaş M. Relationship between emotional eating and coping with stress of nursing students. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2020;57(2):433–42.

Young D, Limbers CA. Avoidant coping moderates the relationship between stress and depressive emotional eating in adolescents. Eat Weight Disord. 2017;22(4):683–91.

Errisuriz VL, Pasch KE, Perry CL. Perceived stress and dietary choices: the moderating role of stress management. Eat Behav. 2016;22:211–6.

van den Tol AJM, Ward MR, Fong H. The role of coping in emotional eating and the use of music for discharge when feeling stressed. Arts Psychother. 2019;64:95–103.

Xie A, Cai TS, He JB, Liu W-L, Liu J-X. Effects of negative emotion on emotional eating of college students: mediating role of negative coping style. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2016;24(2):298–301.

United States Department of Agriculture. MyPlate. 2018. https://www.myplate.gov/

Stadler G, Oettingen G, Gollwitzer PM. Intervention effects of information and self-regulation on eating fruits and vegetables over two years. Health Psychol. 2010;29(3):274–83.

Ozier AD, Kendrick OW, Knol LL, Leeper JD, Perko M, Burnham JJ. Development and validation: the EADES (eating and appraisal due to emotions and stress) questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(4):619–28.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Social Behav. 1983;24:386–96.

Lee E-H. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs Res. 2012;6(4):121–7.

Tucker CM, Rice KG, Hou W, et al. development of the motivators of and barriers to health-smart behaviors inventory. Psychol Assess. 2011;23(2):487–503.

Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the BriefCOPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:92–100.

Eisenberg SA, Shen BJ, Schwarz ER, Mallon S. Avoidant coping moderates the association between anxiety and patient-rated physical functioning in heart failure patients. J Behav Med. 2012;35(3):253–61.

Wichianson JR, Bughu SA, Unger JB, Sprujit-Metz D, Nguyen-Rodriguez ST. Perceive stress, coping, and night-eating in college students. Stress Health. 2009;25(3):235–40.

Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge. 2010.

Hair J, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis , 7th ed. London, UK: Pearson Educational International. 2010.

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a conditional process analysis. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2022.

Hayes AF, Montoya AK, Rockwood NJ. The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Australas Mark J. 2017;25:76–81.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc. 1995;57(1):289–300.

Brosof LC, Munn-Chernoff MA, Bulik CM, Baker JH. Associations between eating expectancies and eating disorder symptoms in men and women. Appetite. 2019;141.

Hayaki J, Free S. Positive and negative eating expectancies in disordered eating among women and men. Eat Behav. 2016;22:22–6.

Smith JM, Serier KN, Belon KE, Sebastian RM, Smith JE. Evaluation of the relationships between dietary restraint, emotional eating, and intuitive eating moderated by sex. Appetite. 2020;155(1): 104817.

Greene D, Mullins M, Baggett P, Cherry D. Self-care for helping professionals: students’ perceived stress, coping self- efficacy, and subjective experiences. J Bacc Soc Work. 2017;22:1–16.

Ling J, Zahry NR. Relationships among perceived stress, emotional eating, and dietary intake in college students: Eating self-regulation as a mediator. Appetite. 2021;163.

Marshall SJ, Elliott CC. Predicting college students’ food intake quality with dimensions of executive functioning. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2016;237- 252.

Pribis P, Burtnack CA, McKenzie SO, Thayer J. Trends in body fat, body mass index and physical fitness among male and female college students. Nutrients. 2010;2(10):1075–85.

Quintiliani LM, Whiteley JA. Results of a nutrition and physical activity peer counseling intervention among nontraditional college students. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31:366–74.

Schroeter C, House LA. Fruit and vegetable consumption of college students: what is the role of food culture? J Food Distrib Res. 2015;46(3):131–52.

Son C, Hegde S, Smith A, Wang X, Sasangohar F. Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: interview survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9): e21279.

Peltzer K, Pengpid S. Dietary consumption and happiness and depression among university students: A cross-national survey. J Psychol Afr. 2017;27(4):372–7.

Wright RR, Shuai J, Maldonado Y, Nelson C. The cents program: promoting healthy eating by addressing perceived barriers. Psychol Health. 2021;1:1–19.

Brown ON, O’Connor LE, Savaiano D. Mobile MyPlate: a pilot study using text messaging to provide nutrition education and promote better dietary choices in college students. J Am Coll Health. 2014;62(5):320–7.

Bernardo GL, Rodrigues VM, Bastos BS, et al. Association of personal characteristics and cooking skills with vegetable consumption frequency among university students. Appetite. 2021;166.

Martin S, McCormack L. Eating behaviors and the perceived nutrition environment among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2022.

Vidic Z. Multi-year investigation of a relaxation course with a mindfulness meditation component on college students’ stress, resilience, coping and mindfulness. J Am Coll Health. 2021;1–6.

Yusufov M, Nicoloro-Santa BJ, Grey NE, Moyer A, Lobel M. Meta- analytic evaluation of stress reduction interventions for undergraduate and graduate students. Int J Stress Manag. 2019;26(2):132–45.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Yusuf Chaudhry, Elizabeth Doll, Nakita Edwards, Cheryl Errichetti, Mackenzie Graf, Sarah Kaden, Madison Lasko, and Alexandra Palumbo for their assistance with data collection.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Elizabethtown College, 1 Alpha Drive, Elizabethtown, PA, 17022, USA

Elizabeth D. Dalton

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elizabeth D. Dalton .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Dalton, E.D. Emotional Eating in College Students: Associations with Coping and Healthy Eating Motivators and Barriers. Int.J. Behav. Med. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-023-10193-y

Download citation

Accepted : 06 June 2023

Published : 29 June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-023-10193-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Emotional eating

- College students

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Stress Eating and Health: Findings from MIDUS, a National Study of U.S. Adults

The epidemic of obesity and its related chronic diseases has provoked interest in the predictors of eating behavior. Eating in response to stress has been extensively examined, but currently unclear is whether stress eating is associated with obesity and morbidity. We tested whether self-reported stress eating was associated with worse glucose metabolism among nondiabetic adults as well as with increased odds of prediabetes and diabetes. Further, we investigated whether these relationships were mediated by central fat distribution. Participants were 1138 adults (937 without diabetes) in the Midlife in the U.S. study (MIDUS II). Glucose metabolism was characterized by fasting glucose, insulin, insulin resistance (HOMAIR), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA 1c ), prediabetes, and diabetes status. Multivariate-adjusted analyses showed that stress eating was associated with significantly higher nondiabetic levels of glucose, insulin, insulin resistance, and HbA 1c as well as higher odds of prediabetes or diabetes. Relationships between stress eating and all outcomes were no longer statistically significant once waist circumference was added to the models, suggesting that it mediates such relationships. Findings add to the growing literature on the relationships among psychosocial factors, obesity, and chronic disease by documenting associations between stress eating and objectively measured health outcomes in a national sample of adults. The findings have important implications for interventive targets related to obesity and chronic disease, namely, strategies to modify the tendency to use food as a coping response to stress.

Introduction

Obesity is the most critical factor in the development of metabolic disease, with contemporary environments frequently described as obesogenic, or promoting obesity via abundant availability of energy-dense food accompanied by decline in physical activity ( Chaput, Klingenberg, Astrup, & Sjodin, 2011 ; Swinburn, Egger, & Raza, 1999 ). More than 1/3 of American adults were obese in 2009–2010 ( Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012 ); 25.8 million Americans have diabetes and 79 million have prediabetes ( Centers for Disease Control, 2011 ). Traditionally, research has focused on diet and physical activity as cornerstones of obesity prevention and treatment, although it is clear that these factors leave considerable variance unexplained. Investigators have thus concentrated on identifying factors that extend the concept of energy balance by describing pathways to energy imbalance. Studies on triggers of eating behaviors document that a negative energy balance is a sufficient, but not necessary condition for initiating an eating episode ( Del Parigi, 2010 ). What matters as well for initiation of an eating episode are complex interactions among emotional, cognitive, and cultural factors ( Del Parigi, 2010 ).

Eating in excess of metabolic needs is, in fact, the leading contributor to weight gain, obesity, and subsequent morbidity. The link between stress and eating has received significant attention, given the considerable overlap between the physiological systems that regulate food intake and that mediate the stress response ( Tannenbaum, 2010 ). During stress, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is activated to prepare the organism for fight or fight; that is, mounting a defensive response depends on available energy. Thus, the HPA axis initiates a cascade of physiological adaptations such as the release of glucose into the bloodstream, thereby suppressing hunger ( Gold & Chrousos, 2002 ). Emotional eaters, however, do not show the typical response of eating less during stress ( Gold & Chrousos, 2002 ). Instead, they eat the same amount, or more, during stress ( Oliver, Wardle, & Gibson, 2000 ; van Strien & Ouwens, 2003 ). It has been suggested that people use “comfort food”, meaning food high in sugar and fat, in an effort to reduce activity in the chronic stress-response network with its attendant anxiety. Intake of comfort food is thought to alleviate stress by reducing HPA axis activity and promoting the activation of brain circuits involved in reward-seeking behavior ( Dallman et al., 2003 ), thereby further reinforcing feeding behavior ( Dallman, 2010 ).

Self-reported stress levels have been increasing over time ( Cohen, 2012 ). In addition, acute and chronic stressors have been linked to energy-dense food intake, weight gain, obesity and glucoregulation ( Bjorntorp, 2001 ; Block, He, Zaslavsky, Ding, & Ayanian, 2009 ; Eriksson et al., 2008 ; Groesz et al., 2012 ; Heraclides, Chandola, Witte, & Brunner, 2009 ; Laitinen, Ek, & Sovio, 2002 ; Ng & Jeffery, 2003 ). A recent national survey documented that 39% of people overeat, or increase consumption of energy-dense foods in response to stress ( American Psychological Association, 2012 ). Nonetheless, it remains unclear whether eating in response to stress has metabolic consequences such as dysregulated glycemic control and abdominal obesity. One study looked at the relationship between self-reported stress eating and metabolic syndrome in medical students and found that stress eaters showed significant increases in weight and insulin during an exam period compared to students who reported eating less during stress ( Epel et al., 2004 ).

To our knowledge, no study has examined relationships among stress eating, obesity, and metabolic disease in a national sample. The overarching goal of this investigation was to assess whether eating in response to stress was associated with glucoregulation. Further, we evaluated the role of waist circumference as a potential mediator of the relationship between stress eating and glucoregulation. The underlying rationales were first, that stress activation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of abdominal obesity ( Bjorntorp, 2001 ; Dallman, Pecoraro, & la Fleur, 2005 ), and second, that waist circumference is a powerful predictor of diabetes ( Klein et al., 2007 ). The specific hypotheses of our study therefore were:

- Hypothesis 1 (H1). (a) Eating in response to stress will be associated with worse nondiabetic levels of fasting glucose, insulin, insulin resistance, and HbA 1c . (b) Waist circumference will mediate the relationships between using food in response to stress and fasting glucose, insulin, insulin resistance, and HbA 1c

- Hypothesis 2 (H2). (a) Extending the prior hypotheses to disease progression, eating in response to stress will be associated with higher odds of prediabetes in the nondiabetic subsample as well as diabetes in the full analytical sample. (b) Waist circumference will mediate the relationships between using food in response to stress and higher odds of prediabetes in the nondiabetic subsample and diabetes in the full analytical sample.

Material and Methods

Data are from the Midlife in the US II (MIDUS II) study, a longitudinal follow-up of the original MIDUS sample (N = 7,108). Begun in 1995/96, the overarching objective of MIDUS was to investigate the role of behavioral, psychological, and social factors in physical and mental health. All eligible participants were non-institutionalized, English-speaking adults in the coterminous United States, initially 25 to 74 years of age. Approximately 9–10 years later, respondents were re-contacted and invited to participate in MIDUS II. The longitudinal retention rate was 75%, adjusted for mortality (Radler & Ryff, 2010). One objective of MIDUS II was to extend the scientific scope of the study by adding comprehensive biological assessments on a subsample of respondents who had completed a phone interview and self-administered questionnaires. Forty-three percent of the invited MIDUS II respondents participated in the biological data collection. The majority (87.8%) of African American respondents came from a city-specific sample from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, which was implemented to increase participation of African Americans in the biological data collection, given its close proximity to one of the clinic sites. This full biomarker sample was not significantly different from the main MIDUS sample on age, sex, race, marital status, or income variables, although participants were significantly more educated than the main sample ( Love, Seeman, Weinstein, & Ryff, 2010 ).

The current analyses used data from the biological sample of MIDUS II and included 1255 participants ages 34 to 84 ( M =54.52, SD =11.71), more than half of whom (57%) were female. Only respondents who identified as White or African American were included in the current study because small sample sizes precluded the inclusion of other minority groups. After excluding 117 cases due to partially missing data on any variable in the analysis, or to a race other than black or white, 1138 participants had complete data. Table 1 includes descriptive information for all variables in the analyses.

Means (and SDs) or Proportions for All Measures Stratified by Stress Eating 1 and Diabetes Status

Note: High stress eating group consists of people who answered the questions the two questions about food quantity and preference with “a lot” or “a medium amount.” Low stress eating group consists of people who answered the questions with “only a little” and “not at all.” Stress eating was dichotomized into high and low stress eating groups for descriptive analyses only; a continuous measure of stress eating was used in all regression analyses.

Glucoregulation was indexed using three primary biological measures (fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and HbA 1c ) and three composite measures (insulin resistance, prediabetes, diabetes). Fasting glucose, insulin, and HbA 1c samples were obtained during an overnight stay in a General Clinical Research Center (GCRC). Fasting glucose was measured via an enzymatic assay photometrically on an automated analyzer (Roche Modular Analytics P). Fasting insulin was measured with an ADVIA Centaur Insulin assay, performed on a Siemens Advia Centaur analyzer. The HbA 1c assay was a colorimetric total-hemoglobin determination combined with an immunoturbidometric HbA 1c assay, carried out using a Cobas Integra Systems instrument (Roche Diagnostics) ( Wolf, Lang, & Zander, 1984 ). The first composite measure (insulin resistance) was calculated using the Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA-IR) formula that incorporates both glucose and insulin to describe the interplay between them ( Matthews et al., 1985 ).

The other composites were dichotomous categorizations that used criteria from the American Diabetes Association to define presence of prediabetes or diabetes ( 2013 ). Specifically, nondiabetic individuals were classified as “prediabetic” if their HbA 1c was between 5.7–6.5% or their glucose was between 100–126 mg/dl. In the full analytical sample, diabetes status was coded positive if HbA 1c exceeded 6.5%, fasting glucose exceeded 126 mg/dl, or participant reported taking anti-diabetic medications. Using these criteria, 201 were coded as diabetic. All primary and composite measures are reliable and widely used in clinical practice to predict risk for disease ( Ausk, Boyko, & Ioannou, 2010 ; Balkau et al., 1998 ; Bloomgarden, 2011a , 2011b ; Parekh, Lin, Hayes, Albu, & Lu-Yao, 2010 ; Skriver, Borch-Johnsen, Lauritzen, & Sandbaek, 2010 ). Central fat distribution was indexed by waist circumference (WC), measured by a GCRC staff member around the abdomen just above the hip bone.

Respondents were asked to indicate how they “usually experience a stressful event,” two options of which were “I eat more of my favorite foods to make myself feel better” and “I eat more than I usually do.” Responses ranged from 1= a lot to 4= not at all . Responses to the two items were reverse coded and summed so that higher scores indicated greater use of food in response to stress. The correlation between the two items was .81 in the nondiabetic subsample and .80 in the full analytical sample.

All models were multivariate-adjusted for relevant covariates. Age, household income, and education (12 categories ranged from no school to completion of a professional degree) were treated as continuous variables. Race (black or white) and gender (male or female) were categorical variables.

Data Analysis

Hierarchical multiple regression models were used to predict waist circumference and glycemic control indices (fasting glucose, insulin, insulin resistance, and HbA 1c ). Fasting insulin and HOMA-IR were log-transformed to achieve normal distributions. Binary logistic regression models were used to predict prediabetes and diabetes status. Age and income were rescaled in the regression models such that one unit in the age variable was equal to 10 years and one unit in the income variable was equal to 10,000 dollars. We employed Baron and Kenny’s (1986) criteria for testing waist circumference as a mediator. Additionally, we estimated percent explained (PE), a summary measure of the indirect effect that clarifies the extent to which the effect of stress eating on the different indicators of glucose metabolism was mediated by WC.

Preliminary analyses tested for gender, age, and race differences in the associations between using food to cope and glucoregulation by estimating a model with three two-way interaction terms created by multiplying combinations of gender, age, and race by stress eating. Since none of the interactions was significant, the entire sample was analyzed as one group. All models included all covariates (age, gender, race, education, and household income).

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1 .

H1: Stress eating will predict higher levels of glucose, insulin, insulin resistance, and HbA 1c and these effects will be mediated by waist circumference

Model 1 (see Table 2 ) displays estimates with respect to H1. Consistent with H1, multivariate-adjusted models confirmed that stress eating was associated with higher glucose ( b =.67, p <.001), log-transformed insulin ( b =.08, p <.001), log-transformed insulin resistance ( b =.08, p <.001), and HbA 1c ( b =.02, p <.01). Stress eating was linked with waist circumference in the nondiabetic subsample ( b =.91, p <.001) and waist circumference was associated with all measures of glucoregulation ( p <.001 for all) in multivariate-adjusted models. In contrast to Model 1 estimates, coefficients in Model 1.1—which added waist circumference—indicated that the associations between stress eating and glucose, log-transformed insulin, log-transformed insulin resistance, and HbA 1c were reduced in size and no longer significant ( p ranged from .1 to .2), thus demonstrating that WC mediated the relationships between stress eating and all measures of glucoregulation. Using PE, we found that waist circumference mediated a significant part of the effect of stress eating on glucose (61% PE), log-transformed insulin (81% PE), log-transformed insulin resistance (79% PE), and HbA 1c (56% PE).

Linear Regression Results for Stress Eating, Waist Circumference, and Nondiabetic Glucoregulation (N=937)

Note: Unstandardized coefficients are shown. Insulin and insulin resistance are log-transformed. The age and income variables have been rescaled: one unit in the rescaled age variable is equal to 10 years and one unit in the rescaled income variable is equal to 10,000 dollars.

H2: Stress eating will predict prediabetes and diabetes and these effects will be mediated by waist circumference

Model 2 (see Table 3 ) displays results for the logistic regression models documenting that stress eating was associated with prediabetes ( OR =1.09, p <.05) in the nondiabetic sample and diabetes ( OR =1.15, p <.002) in the full analytical sample. Stress eating was linked with waist circumference in the full sample ( β =.93, p <.001) and waist circumference was associated with all measures of glucoregulation ( p <.001 for all). In contrast to Model 2 estimates, once waist circumference was added, stress eating was no longer a significant predictor of prediabetes ( p =.7) or diabetes status ( p =.3) (See Model 2.1), thus providing supportive evidence that higher waist circumference mediates the relationship between stress eating and glucoregulation.

Estimated odds ratios for the associations between stress eating, prediabetes, and diabetes.

Note: The age and income variables have been rescaled: one unit in the rescaled age variable is equal to 10 years and one unit in the rescaled income variable is equal to 10,000 dollars.

Discussion and Conclusions

The objective of this study was to examine relationships between stress eating and clinically significant measures of metabolic health. The “flight or fight” response to stress causes release of glucose in the bloodstream, which is known to suppress appetite. However, for many people, the response to stressful situations is not to avoid eating, but to consume high volumes of energy-dense comfort foods. Using continuous measures of fasting glucose, insulin, insulin resistance, and HbA 1c , we documented that stress eating was associated with worse glycemic control and prediabetes status among nondiabetic adults as well as diabetes in the full sample. Importantly, waist circumference was found to mediate these relationships. Taken together, these results confirm and extend results from a smaller experimental study ( Epel et al., 2004 ), and suggest that stress eating is associated with objectively measured glucoregulation outcomes and specific diabetic morbidities, with the effects occurring primarily through central adiposity.

Traditional weight loss interventions often focus on diet and exercise, and although they may result in temporary weight loss, recurrent weight gain is common. A meta-analysis of weight loss interventions documented that 5 years post intervention three-fourths of the lost weight was regained ( Anderson, Konz, Frederich, & Wood, 2001 ). One reason for relapse may be that traditional interventions do not target the root cause of overeating and inactivity. Using food to cope with stress may be one such underlying cause that is a potential target of intervention, as the response may be modifiable. If so, it could offer an important step toward incorporating characteristics of the individual in obesity treatment programs (National Institutes of Health, 1998 ). Stressors are thought to activate a neural stress-response network that promotes emotional activity and degrades executive function, resulting in employment of formed habits rather than cognitive resources ( Dallman, 2010 ). Coping with stress by eating palatable foods may thus reduce anxiety and perceived stress, while further reinforcing the feeding habit. To reduce such stress-induced eating, it is important to identify alternative strategies that promote cognitive, goal-directed responses to stress. For example, little is known about the relationships between coping with food and problem- and emotion-focused coping skills ( Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, 1989 ). If comfort feeding is the default response and no active behavioral or emotional strategies are available to deal with the stressor, it is easy to understand how stressors and stress eating reinforce each other, with consequences for promoting obesity and chronic disease.

Mindfulness-based training ( Kristeller & Wolever, 2011 ) may be relevant, given the focus on guided practices to address responses to different emotional states as well as awareness of hunger and satiety cues and related links to conscious food choices. Emerging findings from mindfulness-based interventions document improvements in weight, eating habits, and mental health ( Alberts, Mulkens, Smeets, & Thewissen, 2010 ; Alberts, Thewissen, & Raes, 2012 ; Dalen et al., 2010 ; Daubenmier et al., 2011 ). Importantly, empowering people to cultivate awareness of emotional triggers and eating patterns may also promote self-acceptance ( Kristeller & Wolever, 2011 ), which converges with the idea that effective motivational strategies for health promotion must focus on adopting health behaviors without referencing body weight ( Puhl, Peterson, & Luedicke, 2012 ).

Several limitations of the present study need to be acknowledged. The absence of longitudinal data on stress eating and glucose metabolism limits the strength of the conclusions regarding the directionality of described relationships. However, previous prospective research linking stress eating to metabolic dysregulation ( Epel et al., 2004 ) makes it less likely that poor glycemic control was the precipitating event that promoted stress eating. Another limitation is that many of the African-American respondents were drawn from a city-specific oversample (i.e., Milwaukee) implemented to increase participation of Blacks in the MIDUS biomarker project. Thus, they are not nationally representative. It should be noted, however, that the findings were not driven by racial factors, nor were there differences in the pattern of associations between white and black participants. It is not clear if the results generalize to other ethnicities. Our analyses also did not examine the varieties of stress that may be precursors to stress eating, for which MIDUS has multiple indicators (e.g., job stress, caregiving stress, daily stress, perceived discrimination, work/family conflict). Other individual difference variables, such as personality characteristics (e.g., neuroticism) may add further precision in identifying those most susceptible to stress eating. Finally, our analyses are modeled to capture influences on type 2 diabetes, but we did not have information on whether participants in the diabetes category had type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Given that approximately 90–95% of people with diabetes have type 2 diabetes ( American Diabetes Association, 2013 ), our results are not significantly affected by this imprecision. Despite these caveats, the findings that stress eating was associated with increased waist circumference and worse glucoregulation helps advance understanding of the psychosocial underpinnings of obesity and glucoregulation. Continuing to elucidate the various processes that underlie energy imbalance and behavioral responses to it is critical for developing effective preventive and interventive efforts related to obesity and its disease sequelae.

- We investigate whether stress eating predicts health in a national sample of adults.

- Specific outcomes include nondiabetic glycemic control, pre-diabetes, and diabetes.

- We find that stress eating predicts these outcomes.

- Waist circumference mediates the relationships between stress eating and health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166; Carol D. Ryff, Principal Investigator) to conduct a longitudinal follow-up of the MIDUS (Midlife in the US) investigation. The original study was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Midlife Development. We thank the staff of the Clinical Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, at the University of California—Los Angeles, and at Georgetown University for their support in conducting this study. Data collection was supported by the following grants M01-RR023942 (Georgetown), M01-RR00865 (UCLA) from the General Clinical Research Centers Program, and 1UL1RR025011 (UW) from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. The first author of this study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (K01AG041179) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health And Human Development (T32HD049302). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- Alberts HJ, Mulkens S, Smeets M, Thewissen R. Coping with food cravings. Investigating the potential of a mindfulness-based intervention. Appetite. 2010; 55 (1):160–163. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alberts HJ, Thewissen R, Raes L. Dealing with problematic eating behaviour. The effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on eating behaviour, food cravings, dichotomous thinking and body image concern. Appetite. 2012; 290:58 (3):847–851. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2013; 36 (Suppl 1):S67–74. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American Psychological Association. Stress in America: Our Health at Risk [Press Release] 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson JW, Konz EC, Frederich RC, Wood CL. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001; 74 (5):579–584. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ausk KJ, Boyko EJ, Ioannou GN. Insulin resistance predicts mortality in nondiabetic individuals in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2010; 33 (6):1179–1185. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Balkau B, Shipley M, Jarrett RJ, Pyorala K, Pyorala M, Forhan A, Eschwege E. High blood glucose concentration is a risk factor for mortality in middle-aged nondiabetic men. 20-year follow-up in the Whitehall Study, the Paris Prospective Study, and the Helsinki Policemen Study. Diabetes Care. 1998; 21 (3):360–367. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986; 51 (6):1173–1182. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bjorntorp P. Do stress reactions cause abdominal obesity and comorbidities? Obes Rev. 2001; 2 (2):73–86. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Block JP, He Y, Zaslavsky AM, Ding L, Ayanian JZ. Psychosocial stress and change in weight among US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2009; 170 (2):181–192. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bloomgarden ZT. World congress on insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease: Part 1. Diabetes Care. 2011a; 34 (7):e115–120. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bloomgarden ZT. World congress on insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease: part 2. Diabetes Care. 2011b; 34 (8):e126–131. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989; 56 (2):267–283. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Centers for Disasea Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chaput JP, Klingenberg L, Astrup A, Sjodin AM. Modern sedentary activities promote overconsumption of food in our current obesogenic environment. Obes Rev. 2011; 12 (5):e12–20. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D. Who’s Stressed? Distributions of Psychological Stress in the United States in Probability Samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2012; 42 :1320–1334. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dalen J, Smith BW, Shelley BM, Sloan AL, Leahigh L, Begay D. Pilot study: Mindful Eating and Living (MEAL): weight, eating behavior, and psychological outcomes associated with a mindfulness-based intervention for people with obesity. Complement Ther Med. 2010; 18 (6):260–264. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dallman MF. Stress-induced obesity and the emotional nervous system. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010; 21 (3):159–165. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dallman MF, Pecoraro N, Akana SF, La Fleur SE, Gomez F, Houshyar H, Manalo S. Chronic stress and obesity: a new view of “comfort food” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003; 100 (20):11696–11701. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dallman MF, Pecoraro NC, la Fleur SE. Chronic stress and comfort foods: self-medication and abdominal obesity. Brain Behav Immun. 2005; 19 (4):275–280. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Daubenmier J, Kristeller J, Hecht FM, Maninger N, Kuwata M, Jhaveri K, Epel E. Mindfulness Intervention for Stress Eating to Reduce Cortisol and Abdominal Fat among Overweight and Obese Women: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Study. J Obes. 2011; 2011 :651936. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Del Parigi A. Neuroanatomical correlates of hunger and satiety in lean and obese individuals. In: Dube L, Bechara A, Dagher A, Drewnowski A, LeBel J, James P, Yada R, editors. Obesity Prevention. 1. Academic Press; 2010. pp. 253–271. [ Google Scholar ]

- Epel E, Jimenez S, Brownell K, Stroud L, Stoney C, Niaura R. Are stress eaters at risk for the metabolic syndrome? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004; 1032 :208–210. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eriksson AK, Ekbom A, Granath F, Hilding A, Efendic S, Ostenson CG. Psychological distress and risk of pre-diabetes and Type 2 diabetes in a prospective study of Swedish middle-aged men and women. Diabet Med. 2008; 25 (7):834–842. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in melancholic and atypical depression: high vs low CRH/NE states. Mol Psychiatry. 2002; 7 (3):254–275. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Groesz LM, McCoy S, Carl J, Saslow L, Stewart J, Adler N, Epel E. What is eating you? Stress and the drive to eat. Appetite. 2012; 58 (2):717–721. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- NIo Health. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998; 6 (Suppl 2):51S–209S. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heraclides A, Chandola T, Witte DR, Brunner EJ. Psychosocial stress at work doubles the risk of type 2 diabetes in middle-aged women: evidence from the Whitehall II study. Diabetes Care. 2009; 32 (12):2230–2235. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klein S, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, Kelley DE, Leibel RL, Nonas C, Kahn R. Waist Circumference and Cardiometabolic Risk: a Consensus Statement from Shaping America’s Health: Association for Weight Management and Obesity Prevention; NAASO, the Obesity Society; the American Society for Nutrition; and the American Diabetes Association. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007; 15 (5):1061–1067. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kristeller JL, Wolever RQ. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training for treating binge eating disorder: the conceptual foundation. Eat Disord. 2011; 19 (1):49–61. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Laitinen J, Ek E, Sovio U. Stress-related eating and drinking behavior and body mass index and predictors of this behavior. Prev Med. 2002; 34 (1):29–39. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Love GD, Seeman TE, Weinstein M, Ryff CD. Bioindicators in the MIDUS National Study: Protocol, Measures, Sample, and Comparative Context. J Aging Health. 2010; 22 (8):1059–1080. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985; 28 (7):412–419. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ng DM, Jeffery RW. Relationships between perceived stress and health behaviors in a sample of working adults. Health Psychol. 2003; 22 (6):638–642. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;(82):1–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oliver G, Wardle J, Gibson EL. Stress and food choice: a laboratory study. Psychosom Med. 2000; 62 (6):853–865. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parekh N, Lin Y, Hayes RB, Albu JB, Lu-Yao GL. Longitudinal associations of blood markers of insulin and glucose metabolism and cancer mortality in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Cancer Causes Control. 2010; 21 (4):631–642. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Puhl R, Peterson JL, Luedicke J. Fighting obesity or obese persons? Public perceptions of obesity-related health messages. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Skriver MV, Borch-Johnsen K, Lauritzen T, Sandbaek A. HbA1c as predictor of all-cause mortality in individuals at high risk of diabetes with normal glucose tolerance, identified by screening: a follow-up study of the Anglo-Danish-Dutch Study of Intensive Treatment in People with Screen-Detected Diabetes in Primary Care (ADDITION), Denmark. Diabetologia. 2010; 53 (11):2328–2333. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med. 1999; 29 (6 Pt 1):563–570. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tannenbaum B, Anisman H, Abizaid A. Neuroendocrine stress response and its impact on eating behavior and body weight. In: Dube L, Bechara A, Dagher A, Drewnowski A, LeBel J, James P, Yada R, editors. Obesity Prevention. Academic Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- van Strien T, Ouwens MA. Counterregulation in female obese emotional eaters: Schachter, Goldman, and Gordon’s (1968) test of psychosomatic theory revisited. Eat Behav. 2003; 3 (4):329–340. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wolf HU, Lang W, Zander R. Alkaline haematin D-575, a new tool for the determination of haemoglobin as an alternative to the cyanhaemiglobin method. II. Standardisation of the method using pure chlorohaemin. Clin Chim Acta. 1984; 136 :1–104. 0009-8981(84)90251-1 [pii] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Stress and eating behavior: a daily diary study in youngsters.

- 1 Department of Developmental, Personality and Social Psychology, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

- 2 Department of Public Health, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

Background: Overweight and obesity are growing problems, with more attention recently, to the role of stress in the starting and maintaining process of these clinical problems. However, the mechanisms are not yet known and well-understood; and ecological momentary analyses like the daily variations between stress and eating are far less studied. Emotional eating is highly prevalent and is assumed to be an important mechanism, as a maladaptive emotion regulation (ER) strategy, in starting and maintaining the vicious cycle of (pediatric) obesity.

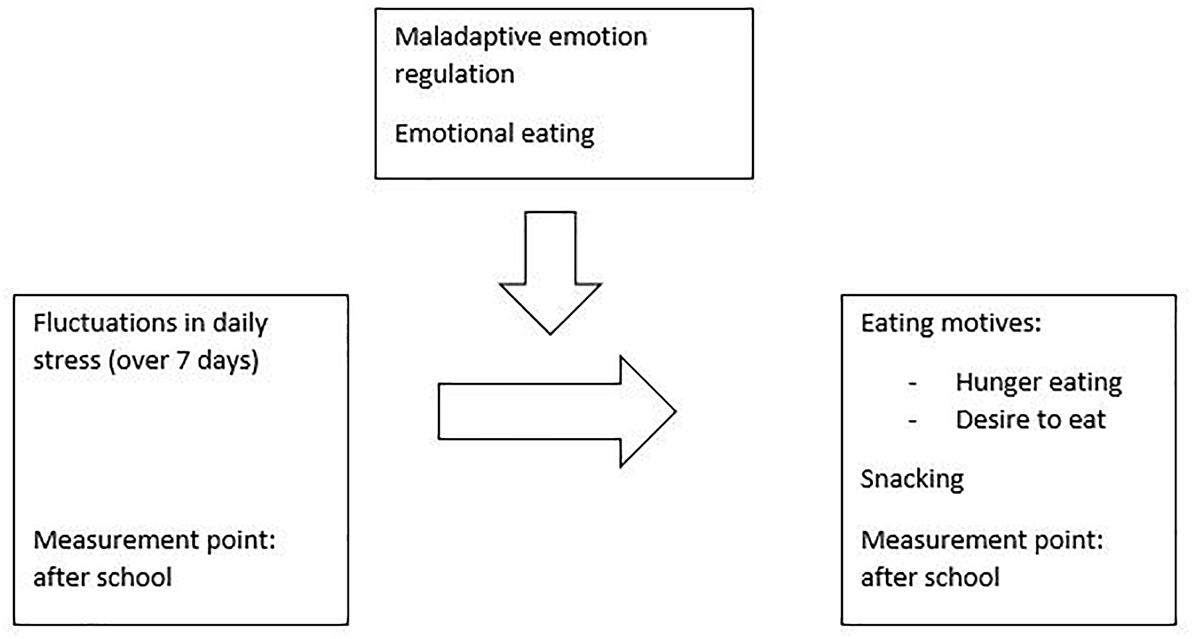

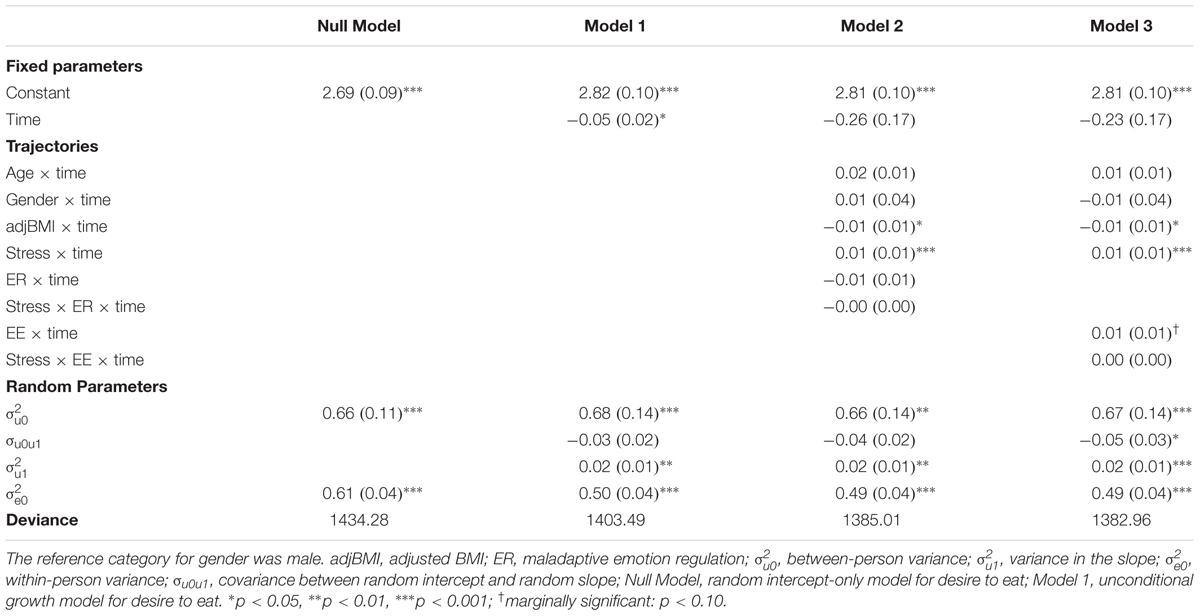

Objectives: The present study aims to investigate in youngsters (10 – 17 years) the daily relationship between stress and the trajectories of self-reported eating behavior (desire to eat motives; hunger eating motives and snacking) throughout 1 week; as well as the moderating role of emotion regulation and emotional eating in an average weight population.

Methods: Participants were 109 average weighted youngsters between the age of 10 and 17 years ( M age = 13.49; SD = 1.64). The youngsters filled in a trait-questionnaire on emotion regulation and emotional eating at home before starting the study, and answered an online diary after school time, during seven consecutive days. Desire to eat motives, hunger eating motives and snacking were assessed daily for seven consecutive days.

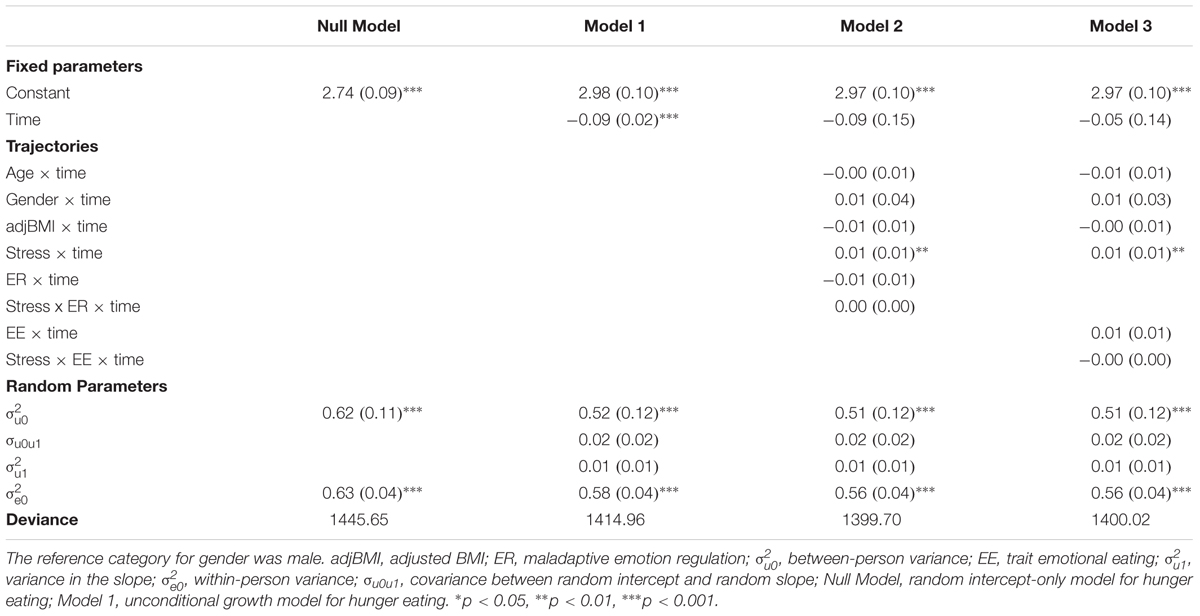

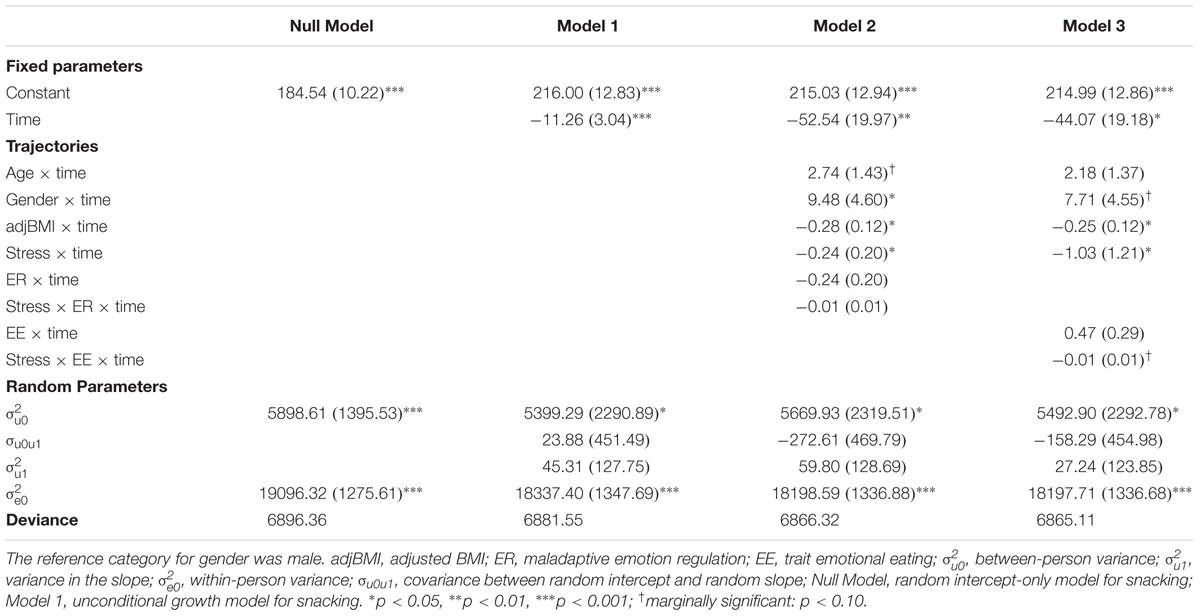

Results: Using multilevel analyses results revealed that daily stress is significantly associated with trajectories of desire to eat motives and hunger eating motives. No evidence was found for the moderating role of maladaptive ER in these relationships; marginally significant evidence was found for the moderating role of emotional eating in the trajectories of desire to eat and snacking.

Discussion: These results stress the importance of looking into the daily relationship between stress and eating behavior parameters, as both are related with change over and within days. More research is needed to draw firm conclusion on the moderating role of ER strategies and emotional eating.

Introduction

Pediatric overweight and obesity are growing problems, as the prevalence of obesity is tripled since 1975. Worldwide, 18% of the children and adolescents (5–19 years) are diagnosed with overweight and 8% with obesity ( World Health Organization [WHO], 2018 ). Parallel to the global rise in pediatric obesity, metabolic, psychological and social health problems are beginning to appear in childhood; and positive associations between these phenomena are found ( Braet et al., 1997 ; Zipper et al., 2001 ; Reilly et al., 2003 ; Erermis et al., 2004 ; Lobstein et al., 2004 ; Reilly and Kelly, 2011 ). Moreover, these diseases are known to track into adulthood ( Ferraro and Kelley-Moore, 2003 ; Reilly et al., 2003 ; Lifshitz, 2008 ; Reilly and Kelly, 2011 ). This progress and the assumed comorbidities emphasize the importance of studying the underlying mechanisms leading to childhood obesity. Psychological and psychophysiological research in this field emphasizes the influence of stress on eating and weight regulation.

Stress Conceptualization

Psychological stress occurs when a person appraises a situation as significant for his or her welfare and when the situation exceeds his or her available coping resources ( Lazarus and Folkman, 1986 ). This definition implicates a subjective component that can be captured only through self-report ( Krohne, 2002 ). Besides, the emotional value of the stressor needs to be taken into account. Lazarus (1993) states that stress is closely related to the conceptualization of emotions because higher levels of stress are consistently associated with higher negative affect but so far, specifically in childhood, this link is less studied in the context of emotional eating ( Cohen et al., 1995 ; Watson, 1998 ; Lemyre and Tessier, 2003 ; Mroczek and Almeida, 2004 ; Minkel et al., 2012 ; Gustafsson et al., 2013 ; Bey et al., 2018 ).

As our stress levels know day-level fluctuations within persons ( Beattie and Griffin, 2014 ), these should be studied as ‘daily hassles,’ which are situations, thoughts or events leading to negative feelings (e.g., annoyance, irritation, worry or frustration) when they occur and inform you on the difficulty or impossibility to achieve your goals and plans ( O’Connor et al., 2008 ).

Stress is associated with the development of different medical and psychological disorders ( Salim, 2014 ). Pertinent to the current study, research in children and adolescents proved that the experience of negative affect and stress is associated with weight gain, a higher waist circumference, a higher BMI and in the long term obesity ( Goodman and Whitaker, 2002 ; Koch et al., 2008 ; De Vriendt et al., 2009 ; Midei and Matthews, 2009 ; Rofey et al., 2009 ; Van Jaarsveld et al., 2009 ; Aparicio et al., 2016 ).

Stress and Eating Behavior

Psychological research shows that stress is associated with overweight and obesity through changes in weight-related health behavior, as stress activates emotional brain networks and elevates the secretion of glucocorticoids and insulin. Both the emotional brain networks and the hormones influence different aspects of our eating behavior such as our food intake, food choice and eating motives (hunger and desire eating) ( O’Connor et al., 2008 ; Dallman, 2010 ; Jastreboff et al., 2013 ).

First, regarding food intake, stress may result in under- or overeating depending on the stress source and stress intensity ( Willenbring et al., 1986 ; Steere and Cooper, 1993 ; O’Connor et al., 2008 ; Ansari and Berg-Beckhoff, 2015 ). Concerning undereating, adults and children are often found to eat less after heavy stressful events and, specifically, family stress is associated with underweight (BMI) ( Popper et al., 1989 ; Stone and Brownell, 1994 ; Oliver and Wardle, 1999 ; Stenhammar et al., 2010 ). However, evidence for overeating after experiencing stress is also found. Next to the detected underweight after family stress, Stenhammar et al. (2010) also report possible overweight after family stress, suggesting a link with respectively under- and overeating. Besides, Evers et al. (2010) and Vandewalle et al. (2017b) show in youngsters how induced negative affect leads to an increased food intake, specifically comfort foods.

Second, concerning food choice, stressor intensity is an important factor. In adults, chronic life stress is associated with the intake of more energy-dense food ( Steptoe et al., 1998 ; Torres and Nowson, 2007 ; O’Connor et al., 2008 ) a lower consumption of main meals and vegetables ( O’Connor et al., 2008 ). In a systematic review and meta-analysis on children, Hill et al. (2018) report that stress, measured via self-reports and via cortisol measures, is associated with the intake of more unhealthy and less healthy food items (8–18 years).

Third, concerning eating motives, De Vriendt et al. (2009) conclude in their review that in adolescents, stress is specifically associated with increased appetite, which can be seen as a desire for food. Therefore, a distinction should be made between ‘hunger eating motives’ (=eating out of hunger) and ‘desire to eat motives’ (=eating out of a desire to eat; eating out of a craving for food), with the latter defined as rather unhealthy eating ( Reichenberger et al., 2016 , 2018 ). Here, a recent EMA study in adults finds that time pressure is associated with more hunger eating ( Reichenberger et al., 2016 ). Goldschmidt et al. (2018) shows in the only available ecologically momentary assessment study (EMA = looking into the current real time behaviors) in obese children in their natural environment that specifically ‘desire to eat motives’ were of importance regarding overeating.

These ecological momentary assessment results ( O’Connor et al., 2008 ; Reichenberger et al., 2016 ) stress the importance of looking into the daily fluctuations in within-person stress levels to better understand the precise role of different daily stressors in eating behavior, on top of the existing measurements of stress. Besides, as eating behaviors are a daily occupation, and appear in different contexts, a diary study can further help to capture the relationship between daily hassles and different indicators of eating behavior.

However, this research in children and adolescents is lacking, but highly needed and relevant as (1) adolescence is an important developmental stage ( Giedd et al., 2009 ); (2) Goldschmidt et al. (2018) showed the importance of daily desire to eat motives in obese youngsters and (3) daily stress is positively associated with daily fluctuations in scores on emotional eating ( Vandewalle et al., 2017a ). It is hypothesized that stress- induced eating or emotional eating, defined as “eating your negative emotions away,” can be seen as a maladaptive emotion regulation (ER) strategy in children also, but this remains to be further explored ( Braet and Van Strien, 1997 ; Thayer, 2001 ; Evers et al., 2010 ).

Role of Emotion Regulation Processes

Emotion regulation strategies.

Emotion regulation refers to the actions by which persons try to influence their emotions, more specifically which emotions they experience, when and how they experience the emotions and how they show their emotions to others ( Gross, 1998 ). Emotion regulation strategies are studied most often in contexts in which persons upregulate their (stress related) negative emotions. Emotion regulation strategies influence eating behavior and health behavior ( Whiteside et al., 2007 ; Evers et al., 2010 ; Koenders and Van Strien, 2011 ), and weight gain and obesity ( De Vriendt et al., 2009 ). This association is stronger when maladaptive emotion regulation strategies are used to deal with the stressor in comparison with the use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies ( Aparicio et al., 2016 ). In a longitudinal perspective, toddlers with lower levels of emotion regulation skills (i.e., more negative emotion reactions and less adequate emotion regulation) have more overweight at the age of 10 ( Graziano et al., 2014 ), suggesting that difficulties in emotion regulation skills in 2 until 5 years old is related to the development of pediatric obesity later in life ( Graziano et al., 2010 ). Using maladaptive emotion regulation strategies is found to mediate the association between the stressor of maternal rejection and emotional eating (measured as a trait, with the DEBQ-questionnaire) in obese youngsters ( Vandewalle et al., 2014 ). On the other hand, adaptive emotion regulation strategies are related with positive health behaviors such as a higher intake of fruits and vegetables and more physical activity ( Isasi et al., 2013 ). Remarkably, whether people with high/low maladaptive emotion regulation strategies cope differently with stress is less studied.

Emotional Eating as Emotion Regulation Strategy

Emotional eating is highly prevalent in community-wide youth samples ( Michels et al., 2012 ) and in youth with obesity ( Braet and Beyers, 2009 ). Besides, emotional eating is treatment resistant, as it often persists after obesity treatment ( Vandewalle et al., 2018 ). Emotional eating can occur in the presence of a lot of different emotions ( Faith et al., 1997 ) and again, is most studied regarding stress-related emotions. In children, high scores on emotional eating have been associated with both negative feelings on physical competencies ( Braet and Van Strien, 1997 ) and experienced stress ( Nguyen-Rodriguez et al., 2009 ; Michels et al., 2012 ). Emotional eating has a short term reinforcing effect, by reducing stress-related arousal and negative affect ( Popless-Vawter et al., 1998 ; Macht, 2008 ). However, in the long-term using the strategy of ‘emotional eating’ in particular in obese persons, often instills feelings of guilt and self-anger ( Popless-Vawter et al., 1998 ), thereby intensifying the existing negative emotions ( Popless-Vawter et al., 1998 ; Gibson, 2006 ). Even more important, emotional eating will not solve the stress origins: as long as people only cope with their stress by means of emotional eating, the stressor will remain and cause psychological discomfort ( Stice et al., 2002 ; Gibson, 2006 ). This way, emotional eating can be seen as a proxy of maladaptive emotion regulation ( Michopoulos et al., 2015 ).

Emotional eating is associated with more calorie-intake ( Braet and Van Strien, 1997 ). This is of concern as emotional eating seems to evolve toward a stable trait component later in life and is of greater importance compared with other life style behaviors for explaining longitudinal weight gain ( Koenders and Van Strien, 2011 ). Persons with a high emotional eating style who are confronted with a stressor eat more high-fat food and more energy-dense meals in comparison with persons who have a low emotional eating style ( Oliver et al., 2000 ). O’Connor et al. (2008) concludes in an EMA-study that the confrontation with daily hassles is associated with more snacking, and this is stronger for individuals who have a high emotional eating style. Interesting, the presence of negative emotions decreases the desire eating in individuals with a low emotional eating style; while the negative emotions do not affect the desire eating in individuals with a high emotional eating style ( Reichenberger et al., 2016 ). This suggests that emotional eating evolves toward a stable trait that might be a moderator in the stress-eating relation.

Research Questions and Daily Diary-Design

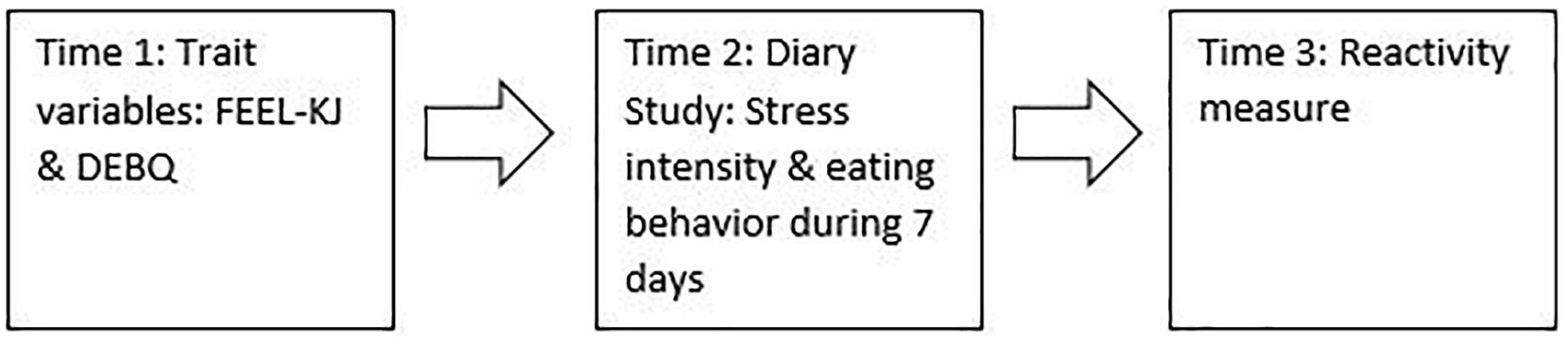

The current study is innovative in different ways: (1) by including children and adolescents, (2) by using a daily diary design during seven consecutive days and (3) by including three indicators of eating behavior; daily hunger eating motives, desire to eat motives and snacking; and their moderating factors, emotion regulation and emotional eating. However, as using a cellphone during school time is often forbidden, the eating motives and snacking during the day will be reported after school time, which is a well-known critical phase with both school related and peer related stress ( Sotardi, 2017 ). The research question is shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1. Research question.

First, we hypothesize that emotional eating will be a proxy of maladaptive emotion regulation (based on Michopoulos et al., 2015 ). Second, we state that daily stress will be significantly associated with (1) the trajectories in desire to eat (2) the trajectories of hunger-eating and (3) the trajectories of snacking (Based on De Vriendt et al., 2009 ; Reichenberger et al., 2016 ; Vandewalle et al., 2017a ). We also hypothesize that these relations will be stronger for youth high in trait maladaptive emotion regulation and/or reporting a more pronounced emotional eating style ( O’Connor et al., 2008 ; Reichenberger et al., 2016 ).

Methodology

Participants.

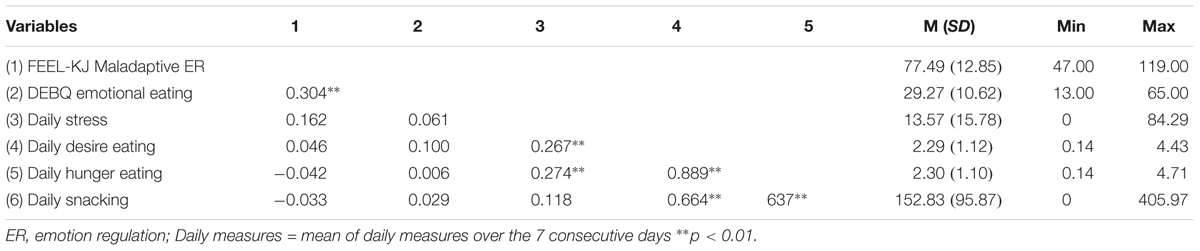

Dutch- speaking children and adolescents were recruited in Belgium, Aalter and Deinze. These youngsters already participated in two previous studies: Generation 2020 study ( Van Beveren et al., 2016 , 2017 ) and the Reward- study ( De Decker et al., 2017a , b ). These are both longitudinal studies with different data collection waves over time on the emotional wellbeing of children and adolescents. During a follow-up data collection in both cohorts, participants were recruited for the current study. A total of 109 participants aged 10–17 years were recruited [ M age = 13.49; SD = 1.64; 51 boys (46.8%) and 57 girls (52.3%)]; one participant did not report their age and gender.

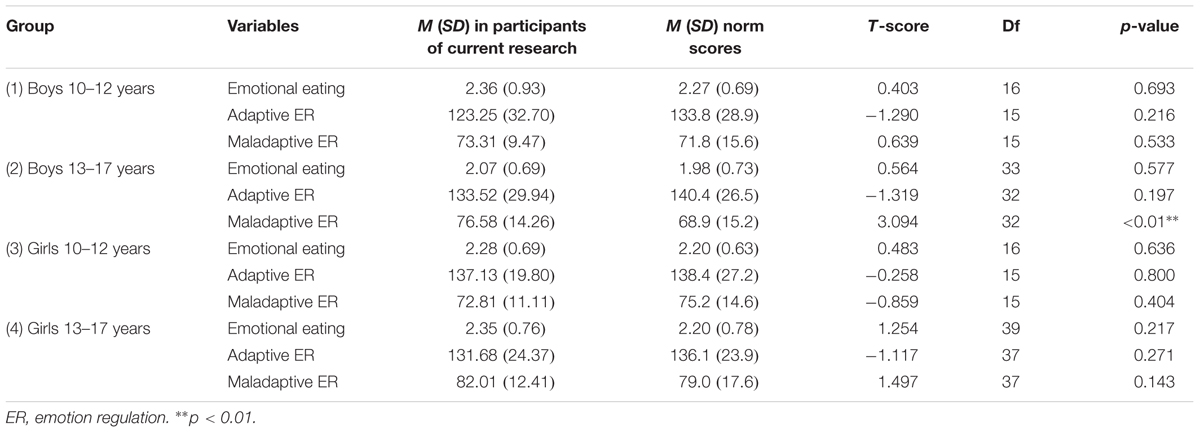

Study Design

Before the diary study, the participants were asked to fill out questionnaires on eating behavior and emotion regulation. Following this, the participants were required to complete the stress/eating behavior diary over seven consecutive days. EMA measures were similar to the study of Reichenberger et al. (2016) , but extended by adding the variable of snacking and the role of emotion regulation (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2. Measurements.

The diary was filled out before breakfast, after school time, when the participants came home from school and before bedtime. In the current study, only the data time point after school was used, which was in most cases filled in between 5 PM and 6 PM. At 5 PM the participants received a reminder message to fill out the diary. Participants were asked to report on their snacking behavior since breakfast.

Trait Variables by Questionnaires

The Fragebogen Zur Erhebung der Emotionsregulation Bei Kindern und Jugendlichen (FEEL-KJ, Grob and Smolenski, 2005 ; A Questionnaire on Emotion Regulation Strategies in Children and Adolescents) is translated from German to Dutch and can be used in children and adolescents between 8 and 18 years old ( Braet et al., 2013 ). The questionnaire measures ER strategies for three emotions: anger, anxiety and sadness. The emotion regulation strategies for every emotion are captured by 30 items, thus the total amount of items is 90. The 15 emotion regulation strategies are divided in three categories of strategies: adaptive, maladaptive and external regulation. The adaptive emotion regulation strategies are distraction, recall a positive emotion, forget, acceptance, problem solving, re-evaluation of the situation, and cognitive reappraisal. The maladaptive strategies are giving up, withdrawing, self- devaluation, rumination and aggression. Looking for social support, controlling your emotions and expressing your emotions are the external strategies. For the Dutch and Flemish population, representative norms are available ( Braet et al., 2013 ). The psychometric qualities of the FEEL-KJ are drawn from a large sample of Dutch speaking Belgian children and adolescents between 8 and 18 years old. A good reliability and validity was found by Cracco et al. (2015) . In the current study, a good reliability was also found for both subscales adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation, respectively α = 0.957 and α = 0.831.

Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire

The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ, van Strien et al., 1986 ; Braet et al., 2008 ) assesses three eating styles: restrained eating, external eating and emotional eating. In this study only the subscale ‘emotional eating’ will be taken into account. The DEBQ contains 33 items, and is a self-report questionnaire. The items question specific eating behaviors, and should be rated on a five-point- Likert scale from 1 = never to 5 = very often. The DEBQ has been shown useful in research with children and adolescents between 7 and 17 years ( Braet et al., 2003 ). Also, good psychometric qualities are reported, such as a good reliability and external validity ( Ricciardelli and McCabe, 2001 ; Braet et al., 2008 ). The emotional eating subscale contains 13 items and has a good internal validity in overweight and normal-weight children (respectively α = 0.91 and α = 0.93) ( Braet et al., 2008 ). In the current study, a good reliability for emotional eating was found (α = 0.946).

Diary-Measures

Stress intensity.

To measure the amount of stress during a particular school day, the participants were asked to rate ‘how stressed did you feel since your breakfast?’ on a visual analog scale from 0 (not at all stressed) to 100 (extremely stressed). By asking about the period since breakfast until after school, we wanted to capture stress related to school performances and peer-related stress (social stress).

Snacking and motives of eating behavior