An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

The Importance of Students’ Motivation for Their Academic Achievement – Replicating and Extending Previous Findings

Ricarda steinmayr.

1 Department of Psychology, TU Dortmund University, Dortmund, Germany

Anne F. Weidinger

Malte schwinger.

2 Department of Psychology, Philipps-Universität Marburg, Marburg, Germany

Birgit Spinath

3 Department of Psychology, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany

Associated Data

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Achievement motivation is not a single construct but rather subsumes a variety of different constructs like ability self-concepts, task values, goals, and achievement motives. The few existing studies that investigated diverse motivational constructs as predictors of school students’ academic achievement above and beyond students’ cognitive abilities and prior achievement showed that most motivational constructs predicted academic achievement beyond intelligence and that students’ ability self-concepts and task values are more powerful in predicting their achievement than goals and achievement motives. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the reported previous findings can be replicated when ability self-concepts, task values, goals, and achievement motives are all assessed at the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria (e.g., hope for success in math and math grades). The sample comprised 345 11th and 12th grade students ( M = 17.48 years old, SD = 1.06) from the highest academic track (Gymnasium) in Germany. Students self-reported their ability self-concepts, task values, goal orientations, and achievement motives in math, German, and school in general. Additionally, we assessed their intelligence and their current and prior Grade point average and grades in math and German. Relative weight analyses revealed that domain-specific ability self-concept, motives, task values and learning goals but not performance goals explained a significant amount of variance in grades above all other predictors of which ability self-concept was the strongest predictor. Results are discussed with respect to their implications for investigating motivational constructs with different theoretical foundation.

Introduction

Achievement motivation energizes and directs behavior toward achievement and therefore is known to be an important determinant of academic success (e.g., Robbins et al., 2004 ; Hattie, 2009 ; Plante et al., 2013 ; Wigfield et al., 2016 ). Achievement motivation is not a single construct but rather subsumes a variety of different constructs like motivational beliefs, task values, goals, and achievement motives (see Murphy and Alexander, 2000 ; Wigfield and Cambria, 2010 ; Wigfield et al., 2016 ). Nevertheless, there is still a limited number of studies, that investigated (1) diverse motivational constructs in relation to students’ academic achievement in one sample and (2) additionally considered students’ cognitive abilities and their prior achievement ( Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ; Kriegbaum et al., 2015 ). Because students’ cognitive abilities and their prior achievement are among the best single predictors of academic success (e.g., Kuncel et al., 2004 ; Hailikari et al., 2007 ), it is necessary to include them in the analyses when evaluating the importance of motivational factors for students’ achievement. Steinmayr and Spinath (2009) did so and revealed that students’ domain-specific ability self-concepts followed by domain-specific task values were the best predictors of students’ math and German grades compared to students’ goals and achievement motives. However, a flaw of their study is that they did not assess all motivational constructs at the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria. For example, achievement motives were measured on a domain-general level (e.g., “Difficult problems appeal to me”), whereas students’ achievement as well as motivational beliefs and task values were assessed domain-specifically (e.g., math grades, math self-concept, math task values). The importance of students’ achievement motives for math and German grades might have been underestimated because the specificity levels of predictor and criterion variables did not match (e.g., Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977 ; Baranik et al., 2010 ). The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the seminal findings by Steinmayr and Spinath (2009) will hold when motivational beliefs, task values, goals, and achievement motives are all assessed at the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria. This is an important question with respect to motivation theory and future research in this field. Moreover, based on the findings it might be possible to better judge which kind of motivation should especially be fostered in school to improve achievement. This is important information for interventions aiming at enhancing students’ motivation in school.

Theoretical Relations Between Achievement Motivation and Academic Achievement

We take a social-cognitive approach to motivation (see also Pintrich et al., 1993 ; Elliot and Church, 1997 ; Wigfield and Cambria, 2010 ). This approach emphasizes the important role of students’ beliefs and their interpretations of actual events, as well as the role of the achievement context for motivational dynamics (see Weiner, 1992 ; Pintrich et al., 1993 ; Wigfield and Cambria, 2010 ). Social cognitive models of achievement motivation (e.g., expectancy-value theory by Eccles and Wigfield, 2002 ; hierarchical model of achievement motivation by Elliot and Church, 1997 ) comprise a variety of motivation constructs that can be organized in two broad categories (see Pintrich et al., 1993 , p. 176): students’ “beliefs about their capability to perform a task,” also called expectancy components (e.g., ability self-concepts, self-efficacy), and their “motivational beliefs about their reasons for choosing to do a task,” also called value components (e.g., task values, goals). The literature on motivation constructs from these categories is extensive (see Wigfield and Cambria, 2010 ). In this article, we focus on selected constructs, namely students’ ability self-concepts (from the category “expectancy components of motivation”), and their task values and goal orientations (from the category “value components of motivation”).

According to the social cognitive perspective, students’ motivation is relatively situation or context specific (see Pintrich et al., 1993 ). To gain a comprehensive picture of the relation between students’ motivation and their academic achievement, we additionally take into account a traditional personality model of motivation, the theory of the achievement motive ( McClelland et al., 1953 ), according to which students’ motivation is conceptualized as a relatively stable trait. Thus, we consider the achievement motives hope for success and fear of failure besides students’ ability self-concepts, their task values, and goal orientations in this article. In the following, we describe the motivation constructs in more detail.

Students’ ability self-concepts are defined as cognitive representations of their ability level ( Marsh, 1990 ; Wigfield et al., 2016 ). Ability self-concepts have been shown to be domain-specific from the early school years on (e.g., Wigfield et al., 1997 ). Consequently, they are frequently assessed with regard to a certain domain (e.g., with regard to school in general vs. with regard to math).

In the present article, task values are defined in the sense of the expectancy-value model by Eccles et al. (1983) and Eccles and Wigfield (2002) . According to the expectancy-value model there are three task values that should be positively associated with achievement, namely intrinsic values, utility value, and personal importance ( Eccles and Wigfield, 1995 ). Because task values are domain-specific from the early school years on (e.g., Eccles et al., 1993 ; Eccles and Wigfield, 1995 ), they are also assessed with reference to specific subjects (e.g., “How much do you like math?”) or on a more general level with regard to school in general (e.g., “How much do you like going to school?”).

Students’ goal orientations are broader cognitive orientations that students have toward their learning and they reflect the reasons for doing a task (see Dweck and Leggett, 1988 ). Therefore, they fall in the broad category of “value components of motivation.” Initially, researchers distinguished between learning and performance goals when describing goal orientations ( Nicholls, 1984 ; Dweck and Leggett, 1988 ). Learning goals (“task involvement” or “mastery goals”) describe people’s willingness to improve their skills, learn new things, and develop their competence, whereas performance goals (“ego involvement”) focus on demonstrating one’s higher competence and hiding one’s incompetence relative to others (e.g., Elliot and McGregor, 2001 ). Performance goals were later further subdivided into performance-approach (striving to demonstrate competence) and performance-avoidance goals (striving to avoid looking incompetent, e.g., Elliot and Church, 1997 ; Middleton and Midgley, 1997 ). Some researchers have included work avoidance as another component of achievement goals (e.g., Nicholls, 1984 ; Harackiewicz et al., 1997 ). Work avoidance refers to the goal of investing as little effort as possible ( Kumar and Jagacinski, 2011 ). Goal orientations can be assessed in reference to specific subjects (e.g., math) or on a more general level (e.g., in reference to school in general).

McClelland et al. (1953) distinguish the achievement motives hope for success (i.e., positive emotions and the belief that one can succeed) and fear of failure (i.e., negative emotions and the fear that the achievement situation is out of one’s depth). According to McClelland’s definition, need for achievement is measured by describing affective experiences or associations such as fear or joy in achievement situations. Achievement motives are conceptualized as being relatively stable over time. Consequently, need for achievement is theorized to be domain-general and, thus, usually assessed without referring to a certain domain or situation (e.g., Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ). However, Sparfeldt and Rost (2011) demonstrated that operationalizing achievement motives subject-specifically is psychometrically useful and results in better criterion validities compared with a domain-general operationalization.

Empirical Evidence on the Relative Importance of Achievement Motivation Constructs for Academic Achievement

A myriad of single studies (e.g., Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2018 ; Muenks et al., 2018 ; Steinmayr et al., 2018 ) and several meta-analyses (e.g., Robbins et al., 2004 ; Möller et al., 2009 ; Hulleman et al., 2010 ; Huang, 2011 ) support the hypothesis of social cognitive motivation models that students’ motivational beliefs are significantly related to their academic achievement. However, to judge the relative importance of motivation constructs for academic achievement, studies need (1) to investigate diverse motivational constructs in one sample and (2) to consider students’ cognitive abilities and their prior achievement, too, because the latter are among the best single predictors of academic success (e.g., Kuncel et al., 2004 ; Hailikari et al., 2007 ). For effective educational policy and school reform, it is crucial to obtain robust empirical evidence for whether various motivational constructs can explain variance in school performance over and above intelligence and prior achievement. Without including the latter constructs, we might overestimate the importance of motivation for achievement. Providing evidence that students’ achievement motivation is incrementally valid in predicting their academic achievement beyond their intelligence or prior achievement would emphasize the necessity of designing appropriate interventions for improving students’ school-related motivation.

There are several studies that included expectancy and value components of motivation as predictors of students’ academic achievement (grades or test scores) and additionally considered students’ prior achievement ( Marsh et al., 2005 ; Steinmayr et al., 2018 , Study 1) or their intelligence ( Spinath et al., 2006 ; Lotz et al., 2018 ; Schneider et al., 2018 ; Steinmayr et al., 2018 , Study 2, Weber et al., 2013 ). However, only few studies considered intelligence and prior achievement together with more than two motivational constructs as predictors of school students’ achievement ( Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ; Kriegbaum et al., 2015 ). Kriegbaum et al. (2015) examined two expectancy components (i.e., ability self-concept and self-efficacy) and eight value components (i.e., interest, enjoyment, usefulness, learning goals, performance-approach, performance-avoidance goals, and work avoidance) in the domain of math. Steinmayr and Spinath (2009) investigated the role of an expectancy component (i.e., ability self-concept), five value components (i.e., task values, learning goals, performance-approach, performance-avoidance goals, and work avoidance), and students’ achievement motives (i.e., hope for success, fear of failure, and need for achievement) for students’ grades in math and German and their GPA. Both studies used relative weights analyses to compare the predictive power of all variables simultaneously while taking into account multicollinearity of the predictors ( Johnson and LeBreton, 2004 ; Tonidandel and LeBreton, 2011 ). Findings showed that – after controlling for differences in students‘ intelligence and their prior achievement – expectancy components (ability self-concept, self-efficacy) were the best motivational predictors of achievement followed by task values (i.e., intrinsic/enjoyment, attainment, and utility), need for achievement and learning goals ( Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ; Kriegbaum et al., 2015 ). However, Steinmayr and Spinath (2009) who investigated the relations in three different domains did not assess all motivational constructs on the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria. More precisely, students’ achievement as well as motivational beliefs and task values were assessed domain-specifically (e.g., math grades, math self-concept, math task values), whereas students’ goals were only measured for school in general (e.g., “In school it is important for me to learn as much as possible”) and students’ achievement motives were only measured on a domain-general level (e.g., “Difficult problems appeal to me”). Thus, the importance of goals and achievement motives for math and German grades might have been underestimated because the specificity levels of predictor and criterion variables did not match (e.g., Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977 ; Baranik et al., 2010 ). Assessing students’ goals and their achievement motives with reference to a specific subject might result in higher associations with domain-specific achievement criteria (see Sparfeldt and Rost, 2011 ).

Taken together, although previous work underlines the important roles of expectancy and value components of motivation for school students’ academic achievement, hitherto, we know little about the relative importance of expectancy components, task values, goals, and achievement motives in different domains when all of them are assessed at the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria (e.g., achievement motives in math → math grades; ability self-concept for school → GPA).

The Present Research

The goal of the present study was to examine the relative importance of several of the most important achievement motivation constructs in predicting school students’ achievement. We substantially extend previous work in this field by considering (1) diverse motivational constructs, (2) students’ intelligence and their prior achievement as achievement predictors in one sample, and (3) by assessing all predictors on the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria. Moreover, we investigated the relations in three different domains: school in general, math, and German. Because there is no study that assessed students’ goal orientations and achievement motives besides their ability self-concept and task values on the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria, we could not derive any specific hypotheses on the relative importance of these constructs, but instead investigated the following research question (RQ):

RQ. What is the relative importance of students’ domain-specific ability self-concepts, task values, goal orientations, and achievement motives for their grades in the respective domain when including all of them, students’ intelligence and prior achievement simultaneously in the analytic models?

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedure.

A sample of 345 students was recruited from two German schools attending the highest academic track (Gymnasium). Only 11th graders participated at one school, whereas 11th and 12th graders participated at the other. Students of the different grades and schools did not differ significantly on any of the assessed measures. Students represented the typical population of this type of school in Germany; that is, the majority was Caucasian and came from medium to high socioeconomic status homes. At the time of testing, students were on average 17.48 years old ( SD = 1.06). As is typical for this kind of school, the sample comprised more girls ( n = 200) than boys ( n = 145). We verify that the study is in accordance with established ethical guidelines. Approval by an ethics committee was not required as per the institution’s guidelines and applicable regulations in the federal state where the study was conducted. Participation was voluntarily and no deception took place. Before testing, we received written informed consent forms from the students and from the parents of the students who were under the age of 18 on the day of the testing. If students did not want to participate, they could spend the testing time in their teacher’s room with an extra assignment. All students agreed to participate. Testing took place during regular classes in schools in 2013. Tests were administered by trained research assistants and lasted about 2.5 h. Students filled in the achievement motivation questionnaires first, and the intelligence test was administered afterward. Before the intelligence test, there was a short break.

Ability Self-Concept

Students’ ability self-concepts were assessed with four items per domain ( Schöne et al., 2002 ). Students indicated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree) how good they thought they were at different activities in school in general, math, and German (“I am good at school in general/math/German,” “It is easy to for me to learn in school in general/math/German,” “In school in general/math/German, I know a lot,” and “Most assignments in school/math/German are easy for me”). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of the ability self-concept scale was high in school in general, in math, and in German (0.82 ≤ α ≤ 0.95; see Table 1 ).

Means ( M ), Standard Deviations ( SD ), and Reliabilities (α) for all measures.

Task Values

Students’ task values were assessed with an established German scale (SESSW; Subjective scholastic value scale; Steinmayr and Spinath, 2010 ). The measure is an adaptation of items used by Eccles and Wigfield (1995) in different studies. It assesses intrinsic values, utility, and personal importance with three items each. Students indicated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree) how much they valued school in general, math, and German (Intrinsic values: “I like school/math/German,” “I enjoy doing things in school/math/German,” and “I find school in general/math/German interesting”; Utility: “How useful is what you learn in school/math/German in general?,” “School/math/German will be useful in my future,” “The things I learn in school/math/German will be of use in my future life”; Personal importance: “Being good at school/math/German is important to me,” “To be good at school/math/German means a lot to me,” “Attainment in school/math/German is important to me”). Internal consistency of the values scale was high in all domains (0.90 ≤ α ≤ 0.93; see Table 1 ).

Goal Orientations

Students’ goal orientations were assessed with an established German self-report measure (SELLMO; Scales for measuring learning and achievement motivation; Spinath et al., 2002 ). In accordance with Sparfeldt et al. (2007) , we assessed goal orientations with regard to different domains: school in general, math, and German. In each domain, we used the SELLMO to assess students’ learning goals, performance-avoidance goals, and work avoidance with eight items each and their performance-approach goals with seven items. Students’ answered the items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). All items except for the work avoidance items are printed in Spinath and Steinmayr (2012) , p. 1148). A sample item to assess work avoidance is: “In school/math/German, it is important to me to do as little work as possible.” Internal consistency of the learning goals scale was high in all domains (0.83 ≤ α ≤ 0.88). The same was true for performance-approach goals (0.85 ≤ α ≤ 0.88), performance-avoidance goals (α = 0.89), and work avoidance (0.91 ≤ α ≤ 0.92; see Table 1 ).

Achievement Motives

Achievement motives were assessed with the Achievement Motives Scale (AMS; Gjesme and Nygard, 1970 ; Göttert and Kuhl, 1980 ). In the present study, we used a short form measuring “hope for success” and “fear of failure” with the seven items per subscale that showed the highest factor loadings. Both subscales were assessed in three domains: school in general, math, and German. Students’ answered all items on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 4 (fully applies). An example hope for success item is “In school/math/German, difficult problems appeal to me,” and an example fear of failure item is “In school/math/German, matters that are slightly difficult disconcert me.” Internal consistencies of hope for success and fear of failure scales were high in all domains (hope for success: 0.88 ≤ α ≤ 0.92; fear of failure: 0.90 ≤ α ≤ 0.91; see Table 1 ).

Intelligence

Intelligence was measured with the basic module of the Intelligence Structure Test 2000 R, a well-established German multifactor intelligence measure (I-S-T 2000 R; Amthauer et al., 2001 ). The basic module of the test offers assessments of domain-specific intelligence for verbal, numeric, and figural abilities as well as an overall intelligence score (a composite of the three facets). The overall intelligence score is thought to measure reasoning as a higher order factor of intelligence and can be interpreted as a measure of general intelligence, g . Its construct validity has been demonstrated in several studies ( Amthauer et al., 2001 ; Steinmayr and Amelang, 2006 ). In the present study, we used the scores that were closest to the domains we investigated: overall intelligence, numerical intelligence, and verbal intelligence (see also Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ). Raw values could range from 0 to 60 for verbal and numerical intelligence, and from 0 to 180 for overall intelligence. Internal consistencies of all intelligence scales were high (0.71 ≤ α ≤ 0.90; see Table 1 ).

Academic Achievement

For all students, the school delivered the report cards that the students received 3 months before testing (t0) and 4 months after testing (t2), at the end of the term in which testing took place. We assessed students’ grades in German and math as well as their overall grade point average (GPA) as criteria for school performance. GPA was computed as the mean of all available grades, not including grades in the nonacademic domains Sports and Music/Art as they did not correlate with the other grades. Grades ranged from 1 to 6, and were recoded so that higher numbers represented better performance.

Statistical Analyses

We conducted relative weight analyses to predict students’ academic achievement separately in math, German, and school in general. The relative weight analysis is a statistical procedure that enables to determine the relative importance of each predictor in a multiple regression analysis (“relative weight”) and to take adequately into account the multicollinearity of the different motivational constructs (for details, see Johnson and LeBreton, 2004 ; Tonidandel and LeBreton, 2011 ). Basically, it uses a variable transformation approach to create a new set of predictors that are orthogonal to one another (i.e., uncorrelated). Then, the criterion is regressed on these new orthogonal predictors, and the resulting standardized regression coefficients can be used because they no longer suffer from the deleterious effects of multicollinearity. These standardized regression weights are then transformed back into the metric of the original predictors. The rescaled relative weight of a predictor can easily be transformed into the percentage of variance that is uniquely explained by this predictor when dividing the relative weight of the specific predictor by the total variance explained by all predictors in the regression model ( R 2 ). We performed the relative weight analyses in three steps. In Model 1, we included the different achievement motivation variables assessed in the respective domain in the analyses. In Model 2, we entered intelligence into the analyses in addition to the achievement motivation variables. In Model 3, we included prior school performance indicated by grades measured before testing in addition to all of the motivation variables and intelligence. For all three steps, we tested for whether all relative weight factors differed significantly from each other (see Johnson, 2004 ) to determine which motivational construct was most important in predicting academic achievement (RQ).

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations

Table 1 shows means, standard deviations, and reliabilities. Tables 2 –4 show the correlations between all scales in school in general, in math, and in German. Of particular relevance here, are the correlations between the motivational constructs and students’ school grades. In all three domains (i.e., school in general/math/German), out of all motivational predictor variables, students’ ability self-concepts showed the strongest associations with subsequent grades ( r = 0.53/0.61/0.46; see Tables 2 –4 ). Except for students’ performance-avoidance goals (−0.04 ≤ r ≤ 0.07, p > 0.05), the other motivational constructs were also significantly related to school grades. Most of the respective correlations were evenly dispersed around a moderate effect size of | r | = 0.30.

Intercorrelations between all variables in school in general.

Intercorrelations between all variables in German.

Intercorrelations between all variables in math.

Relative Weight Analyses

Table 5 presents the results of the relative weight analyses. In Model 1 (only motivational variables) and Model 2 (motivation and intelligence), respectively, the overall explained variance was highest for math grades ( R 2 = 0.42 and R 2 = 0.42, respectively) followed by GPA ( R 2 = 0.30 and R 2 = 0.34, respectively) and grades in German ( R 2 = 0.26 and R 2 = 0.28, respectively). When prior school grades were additionally considered (Model 3) the largest amount of variance was explained in students’ GPA ( R 2 = 0.73), followed by grades in German ( R 2 = 0.59) and math ( R 2 = 0.57). In the following, we will describe the results of Model 3 for each domain in more detail.

Relative weights and percentages of explained criterion variance (%) for all motivational constructs (Model 1) plus intelligence (Model 2) plus prior school achievement (Model 3).

Beginning with the prediction of students’ GPA: In Model 3, students’ prior GPA explained more variance in subsequent GPA than all other predictor variables (68%). Students’ ability self-concept explained significantly less variance than prior GPA but still more than all other predictors that we considered (14%). The relative weights of students’ intelligence (5%), task values (2%), hope for success (4%), and fear of failure (3%) did not differ significantly from each other but were still significantly different from zero ( p < 0.05). The relative weights of students’ goal orientations were not significant in Model 3.

Turning to math grades: The findings of the relative weight analyses for the prediction of math grades differed slightly from the prediction of GPA. In Model 3, the relative weights of numerical intelligence (2%) and performance-approach goals (2%) in math were no longer different from zero ( p > 0.05); in Model 2 they were. Prior math grades explained the largest share of the unique variance in subsequent math grades (45%), followed by math self-concept (19%). The relative weights of students’ math task values (9%), learning goals (5%), work avoidance (7%), and hope for success (6%) did not differ significantly from each other. Students’ fear of failure in math explained the smallest amount of unique variance in their math grades (4%) but the relative weight of students’ fear of failure did not differ significantly from that of students’ hope for success, work avoidance, and learning goals. The relative weights of students’ performance-avoidance goals were not significant in Model 3.

Turning to German grades: In Model 3, students’ prior grade in German was the strongest predictor (64%), followed by German self-concept (10%). Students’ fear of failure in German (6%), their verbal intelligence (4%), task values (4%), learning goals (4%), and hope for success (4%) explained less variance in German grades and did not differ significantly from each other but were significantly different from zero ( p < 0.05). The relative weights of students’ performance goals and work avoidance were not significant in Model 3.

In the present studies, we aimed to investigate the relative importance of several achievement motivation constructs in predicting students’ academic achievement. We sought to overcome the limitations of previous research in this field by (1) considering several theoretically and empirically distinct motivational constructs, (2) students’ intelligence, and their prior achievement, and (3) by assessing all predictors at the same level of specificity as the achievement criteria. We applied sophisticated statistical procedures to investigate the relations in three different domains, namely school in general, math, and German.

Relative Importance of Achievement Motivation Constructs for Academic Achievement

Out of the motivational predictor variables, students’ ability self-concepts explained the largest amount of variance in their academic achievement across all sets of analyses and across all investigated domains. Even when intelligence and prior grades were controlled for, students’ ability self-concepts accounted for at least 10% of the variance in the criterion. The relative superiority of ability self-perceptions is in line with the available literature on this topic (e.g., Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ; Kriegbaum et al., 2015 ; Steinmayr et al., 2018 ) and with numerous studies that have investigated the relations between students’ self-concept and their achievement (e.g., Möller et al., 2009 ; Huang, 2011 ). Ability self-concepts showed even higher relative weights than the corresponding intelligence scores. Whereas some previous studies have suggested that self-concepts and intelligence are at least equally important when predicting students’ grades (e.g., Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ; Weber et al., 2013 ; Schneider et al., 2018 ), our findings indicate that it might be even more important to believe in own school-related abilities than to possess outstanding cognitive capacities to achieve good grades (see also Lotz et al., 2018 ). Such a conclusion was supported by the fact that we examined the relative importance of all predictor variables across three domains and at the same levels of specificity, thus maximizing criterion-related validity (see Baranik et al., 2010 ). This procedure represents a particular strength of our study and sets it apart from previous studies in the field (e.g., Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009 ). Alternatively, our findings could be attributed to the sample we investigated at least to some degree. The students examined in the present study were selected for the academic track in Germany, and this makes them rather homogeneous in their cognitive abilities. It is therefore plausible to assume that the restricted variance in intelligence scores decreased the respective criterion validities.

When all variables were assessed at the same level of specificity, the achievement motives hope for success and fear of failure were the second and third best motivational predictors of academic achievement and more important than in the study by Steinmayr and Spinath (2009) . This result underlines the original conceptualization of achievement motives as broad personal tendencies that energize approach or avoidance behavior across different contexts and situations ( Elliot, 2006 ). However, the explanatory power of achievement motives was higher in the more specific domains of math and German, thereby also supporting the suggestion made by Sparfeldt and Rost (2011) to conceptualize achievement motives more domain-specifically. Conceptually, achievement motives and ability self-concepts are closely related. Individuals who believe in their ability to succeed often show greater hope for success than fear of failure and vice versa ( Brunstein and Heckhausen, 2008 ). It is thus not surprising that the two constructs showed similar stability in their relative effects on academic achievement across the three investigated domains. Concerning the specific mechanisms through which students’ achievement motives and ability self-concepts affect their achievement, it seems that they elicit positive or negative valences in students, and these valences in turn serve as simple but meaningful triggers of (un)successful school-related behavior. The large and consistent effects for students’ ability self-concept and their hope for success in our study support recommendations from positive psychology that individuals think positively about the future and regularly provide affirmation to themselves by reminding themselves of their positive attributes ( Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ). Future studies could investigate mediation processes. Theoretically, it would make sense that achievement motives defined as broad personal tendencies affect academic achievement via expectancy beliefs like ability self-concepts (e.g., expectancy-value theory by Eccles and Wigfield, 2002 ; see also, Atkinson, 1957 ).

Although task values and learning goals did not contribute much toward explaining the variance in GPA, these two constructs became even more important for explaining variance in math and German grades. As Elliot (2006) pointed out in his hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation, achievement motives serve as basic motivational principles that energize behavior. However, they do not guide the precise direction of the energized behavior. Instead, goals and task values are commonly recruited to strategically guide this basic motivation toward concrete aims that address the underlying desire or concern. Our results are consistent with Elliot’s (2006) suggestions. Whereas basic achievement motives are equally important at abstract and specific achievement levels, task values and learning goals release their full explanatory power with increasing context-specificity as they affect students’ concrete actions in a given school subject. At this level of abstraction, task values and learning goals compete with more extrinsic forms of motivation, such as performance goals. Contrary to several studies in achievement-goal research, we did not demonstrate the importance of either performance-approach or performance-avoidance goals for academic achievement.

Whereas students’ ability self-concept showed a high relative importance above and beyond intelligence, with few exceptions, each of the remaining motivation constructs explained less than 5% of the variance in students’ academic achievement in the full model including intelligence measures. One might argue that the high relative importance of students’ ability self-concept is not surprising because students’ ability self-concepts more strongly depend on prior grades than the other motivation constructs. Prior grades represent performance feedback and enable achievement comparisons that are seen as the main determinants of students’ ability self-concepts (see Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2002 ). However, we included students’ prior grades in the analyses and students’ ability self-concepts still were the most powerful predictors of academic achievement out of the achievement motivation constructs that were considered. It is thus reasonable to conclude that the high relative importance of students’ subjective beliefs about their abilities is not only due to the overlap of this believes with prior achievement.

Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

Our study confirms and extends the extant work on the power of students’ ability self-concept net of other important motivation variables even when important methodological aspects are considered. Strength of the study is the simultaneous investigation of different achievement motivation constructs in different academic domains. Nevertheless, we restricted the range of motivation constructs to ability self-concepts, task values, goal orientations, and achievement motives. It might be interesting to replicate the findings with other motivation constructs such as academic self-efficacy ( Pajares, 2003 ), individual interest ( Renninger and Hidi, 2011 ), or autonomous versus controlled forms of motivation ( Ryan and Deci, 2000 ). However, these constructs are conceptually and/or empirically very closely related to the motivation constructs we considered (e.g., Eccles and Wigfield, 1995 ; Marsh et al., 2018 ). Thus, it might well be the case that we would find very similar results for self-efficacy instead of ability self-concept as one example.

A second limitation is that we only focused on linear relations between motivation and achievement using a variable-centered approach. Studies that considered different motivation constructs and used person-centered approaches revealed that motivation factors interact with each other and that there are different profiles of motivation that are differently related to students’ achievement (e.g., Conley, 2012 ; Schwinger et al., 2016 ). An important avenue for future studies on students’ motivation is to further investigate these interactions in different academic domains.

Another limitation that might suggest a potential avenue for future research is the fact that we used only grades as an indicator of academic achievement. Although, grades are of high practical relevance for the students, they do not necessarily indicate how much students have learned, how much they know and how creative they are in the respective domain (e.g., Walton and Spencer, 2009 ). Moreover, there is empirical evidence that the prediction of academic achievement differs according to the particular criterion that is chosen (e.g., Lotz et al., 2018 ). Using standardized test performance instead of grades might lead to different results.

Our study is also limited to 11th and 12th graders attending the highest academic track in Germany. More balanced samples are needed to generalize the findings. A recent study ( Ben-Eliyahu, 2019 ) that investigated the relations between different motivational constructs (i.e., goal orientations, expectancies, and task values) and self-regulated learning in university students revealed higher relations for gifted students than for typical students. This finding indicates that relations between different aspects of motivation might differ between academically selected samples and unselected samples.

Finally, despite the advantages of relative weight analyses, this procedure also has some shortcomings. Most important, it is based on manifest variables. Thus, differences in criterion validity might be due in part to differences in measurement error. However, we are not aware of a latent procedure that is comparable to relative weight analyses. It might be one goal for methodological research to overcome this shortcoming.

We conducted the present research to identify how different aspects of students’ motivation uniquely contribute to differences in students’ achievement. Our study demonstrated the relative importance of students’ ability self-concepts, their task values, learning goals, and achievement motives for students’ grades in different academic subjects above and beyond intelligence and prior achievement. Findings thus broaden our knowledge on the role of students’ motivation for academic achievement. Students’ ability self-concept turned out to be the most important motivational predictor of students’ grades above and beyond differences in their intelligence and prior grades, even when all predictors were assessed domain-specifically. Out of two students with similar intelligence scores, same prior achievement, and similar task values, goals and achievement motives in a domain, the student with a higher domain-specific ability self-concept will receive better school grades in the respective domain. Therefore, there is strong evidence that believing in own competencies is advantageous with respect to academic achievement. This finding shows once again that it is a promising approach to implement validated interventions aiming at enhancing students’ domain-specific ability-beliefs in school (see also Muenks et al., 2017 ; Steinmayr et al., 2018 ).

Data Availability

Ethics statement.

In Germany, institutional approval was not required by default at the time the study was conducted. That is, why we cannot provide a formal approval by the institutional ethics committee. We verify that the study is in accordance with established ethical guidelines. Participation was voluntarily and no deception took place. Before testing, we received informed consent forms from the parents of the students who were under the age of 18 on the day of the testing. If students did not want to participate, they could spend the testing time in their teacher’s room with an extra assignment. All students agreed to participate. We included this information also in the manuscript.

Author Contributions

RS conceived and supervised the study, curated the data, performed the formal analysis, investigated the results, developed the methodology, administered the project, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. AW wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. MS performed the formal analysis, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. BS conceived the study, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. We acknowledge financial support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Technische Universität Dortmund/TU Dortmund University within the funding programme Open Access Publishing.

- Ajzen I., Fishbein M. (1977). Attitude–behavior relations: a theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 84 888–918. 10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Amthauer R., Brocke B., Liepmann D., Beauducel A. (2001). Intelligenz-Struktur-Test 2000 R [Intelligence-Structure-Test 2000 R] . Göttingen: Hogrefe. [ Google Scholar ]

- Atkinson J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychol. Rev. 64 359–372. 10.1037/h0043445 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baranik L. E., Barron K. E., Finney S. J. (2010). Examining specific versus general measures of achievement goals. Hum. Perform. 23 155–172. 10.1080/08959281003622180 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ben-Eliyahu A. (2019). A situated perspective on self-regulated learning from a person-by-context perspective. High Ability Studies . 10.1080/13598139.2019.1568828 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brunstein J. C., Heckhausen H. (2008). Achievement motivation. in Motivation and Action eds Heckhausen J., Heckhausen H. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 137–183. [ Google Scholar ]

- Conley A. M. (2012). Patterns of motivation beliefs: combining achievement goal and expectancy-value perspectives. J. Educ. Psychol. 104 32–47. 10.1037/a0026042 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dweck C. S., Leggett E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 95 256–273. 10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eccles J. S., Adler T. F., Futterman R., Goff S. B., Kaczala C. M., Meece J. L. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. in Achievement and Achievement Motivation ed Spence J. T. San Francisco, CA: Freeman, 75–146 [ Google Scholar ]

- Eccles J. S., Wigfield A. (1995). In the mind of the actor: the structure of adolescents’ achievement task values and expectancy-related beliefs. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 21 215–225. 10.1177/0146167295213003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eccles J. S., Wigfield A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 53 109–132. 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eccles J. S., Wigfield A., Harold R. D., Blumenfeld P. (1993). Age and gender differences in children’s self- and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Dev. 64 830–847. 10.2307/1131221 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliot A. J. (2006). The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motiv. Emot. 30 111–116. 10.1007/s11031-006-9028-7 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliot A. J., Church M. A. (1997). A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72 218–232. 10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.218 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliot A. J., McGregor H. A. (2001). A 2 x 2 achievement goal framework. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 80 501–519. 10.1037//0022-3514.80.3.501 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gjesme T., Nygard R. (1970). Achievement-Related Motives: Theoretical Considerations and Construction of a Measuring Instrument . Olso: University of Oslo. [ Google Scholar ]

- Göttert R., Kuhl J. (1980). AMS — achievement motives scale von gjesme und nygard - deutsche fassung [AMS — German version]. in Motivationsförderung im Schulalltag [Enhancement of Motivation in the School Context] eds Rheinberg F., Krug S., Göttingen: Hogrefe, 194–200 [ Google Scholar ]

- Hailikari T., Nevgi A., Komulainen E. (2007). Academic self-beliefs and prior knowledge as predictors of student achievement in mathematics: a structural model. Educ. Psychol. 28 59–71. 10.1080/01443410701413753 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harackiewicz J. M., Barron K. E., Carter S. M., Lehto A. T., Elliot A. J. (1997). Predictors and consequences of achievement goals in the college classroom: maintaining interest and making the grade. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 73 1284–1295. 10.1037//0022-3514.73.6.1284 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hattie J. A. C. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of 800+ Meta-Analyses on Achievement . Oxford: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang C. (2011). Self-concept and academic achievement: a meta-analysis of longitudinal relations. J. School Psychol. 49 505–528. 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.07.001 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hulleman C. S., Schrager S. M., Bodmann S. M., Harackiewicz J. M. (2010). A meta-analytic review of achievement goal measures: different labels for the same constructs or different constructs with similar labels? Psychol. Bull. 136 422–449. 10.1037/a0018947 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson J. W. (2004). Factors affecting relative weights: the influence of sampling and measurement error. Organ. Res. Methods 7 283–299. 10.1177/1094428104266018 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson J. W., LeBreton J. M. (2004). History and use of relative importance indices in organizational research. Organ. Res. Methods 7 238–257. 10.1177/1094428104266510 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kriegbaum K., Jansen M., Spinath B. (2015). Motivation: a predictor of PISA’s mathematical competence beyond intelligence and prior test achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 43 140–148. 10.1016/j.lindif.2015.08.026 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kumar S., Jagacinski C. M. (2011). Confronting task difficulty in ego involvement: change in performance goals. J. Educ. Psychol. 103 664–682. 10.1037/a0023336 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuncel N. R., Hezlett S. A., Ones D. S. (2004). Academic performance, career potential, creativity, and job performance: can one construct predict them all? J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 86 148–161. 10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.148 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Linnenbrink-Garcia L., Wormington S. V., Snyder K. E., Riggsbee J., Perez T., Ben-Eliyahu A., et al. (2018). Multiple pathways to success: an examination of integrative motivational profiles among upper elementary and college students. J. Educ. Psychol. 110 1026–1048 10.1037/edu0000245 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lotz C., Schneider R., Sparfeldt J. R. (2018). Differential relevance of intelligence and motivation for grades and competence tests in mathematics. Learn. Individ. Differ. 65 30–40. 10.1016/j.lindif.2018.03.005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marsh H. W. (1990). Causal ordering of academic self-concept and academic achievement: a multiwave, longitudinal panel analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 82 646–656. 10.1037/0022-0663.82.4.646 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marsh H. W., Pekrun R., Parker P. D., Murayama K., Guo J., Dicke T., et al. (2018). The murky distinction between self-concept and self-efficacy: beware of lurking jingle-jangle fallacies. J. Educ. Psychol. 111 331–353. 10.1037/edu0000281 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marsh H. W., Trautwein U., Lüdtke O., Köller O., Baumert J. (2005). Academic self-concept, interest, grades and standardized test scores: reciprocal effects models of causal ordering. Child Dev. 76 397–416. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00853.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McClelland D. C., Atkinson J., Clark R., Lowell E. (1953). The Achievement Motive . New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts. [ Google Scholar ]

- Middleton M. J., Midgley C. (1997). Avoiding the demonstration of lack of ability: an underexplored aspect of goal theory. Journal J. Educ. Psychol. 89 710–718. 10.1037/0022-0663.89.4.710 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Möller J., Pohlmann B., Köller O., Marsh H. W. (2009). A meta-analytic path analysis of the internal/external frame of reference model of academic achievement and academic self-concept. Rev. Educ. Res. 79 1129–1167. 10.3102/0034654309337522 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muenks K., Wigfield A., Yang J. S., O’Neal C. (2017). How true is grit? Assessing its relations to high school and college students’ personality characteristics, self-regulation, engagement, and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 109 599–620. 10.1037/edu0000153. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muenks K., Yang J. S., Wigfield A. (2018). Associations between grit, motivation, and achievement in high school students. Motiv. Sci. 4 158–176. 10.1037/mot0000076 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murphy P. K., Alexander P. A. (2000). A motivated exploration of motivation terminology. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25 3–53. 10.1006/ceps.1999 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nicholls J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychol. Rev. 91 328–346. 10.1037/0033-295X.91.3.328 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pajares F. (2003). Self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, and achievement in writing: a review of the literature. Read. Writ. Q. 19 139–158. 10.1080/10573560308222 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pintrich P. R., Marx R. W., Boyle R. A. (1993). Beyond cold conceptual change: the role of motivational beliefs and classroom contextual factors in the process of conceptual change. Rev. Educ. Res. 63 167–199. 10.3102/00346543063002167 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Plante I., O’Keefe P. A., Théorêt M. (2013). The relation between achievement goal and expectancy-value theories in predicting achievement-related outcomes: a test of four theoretical conceptions. Motiv. Emot. 37 65–78. 10.1007/s11031-012-9282-9 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Renninger K. A., Hidi S. (2011). Revisiting the conceptualization, measurement, and generation of interest. Educ. Psychol. 46 168–184. 10.1080/00461520.2011.587723 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robbins S. B., Lauver K., Le H., Davis D., Langley R., Carlstrom A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 130 261–288. 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.261 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ryan R. M., Deci E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25 54–67. 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schneider R., Lotz C., Sparfeldt J. R. (2018). Smart, confident, and interested: contributions of intelligence, self-concepts, and interest to elementary school achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 62 23–35. 10.1016/j.lindif.2018.01.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schöne C., Dickhäuser O., Spinath B., Stiensmeier-Pelster J. (2002). Die Skalen zur Erfassung des schulischen Selbstkonzepts (SESSKO) [Scales for Measuring the Academic Ability Self-Concept] . Göttingen: Hogrefe. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwinger M., Steinmayr R., Spinath B. (2016). Achievement goal profiles in elementary school: antecedents, consequences, and longitudinal trajectories. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 46 164–179. 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.05.006 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seligman M. E., Csikszentmihalyi M. (2000). Positive psychology: an introduction. Am. Psychol. 55 5–14. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Skaalvik E. M., Skaalvik S. (2002). Internal and external frames of reference for academic self-concept. Educ. Psychol. 37 233–244. 10.1207/S15326985EP3704_3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sparfeldt J. R., Buch S. R., Wirthwein L., Rost D. H. (2007). Zielorientierungen: Zur Relevanz der Schulfächer. [Goal orientations: the relevance of specific goal orientations as well as specific school subjects]. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie , 39 165–176. 10.1026/0049-8637.39.4.165 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sparfeldt J. R., Rost D. H. (2011). Content-specific achievement motives. Person. Individ. Differ. 50 496–501. 10.1016/j.paid.2010.11.016 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spinath B., Spinath F. M., Harlaar N., Plomin R. (2006). Predicting school achievement from general cognitive ability, self-perceived ability, and intrinsic value. Intelligence 34 363–374. 10.1016/j.intell.2005.11.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spinath B., Steinmayr R. (2012). The roles of competence beliefs and goal orientations for change in intrinsic motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 104 1135–1148. 10.1037/a0028115 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spinath B., Stiensmeier-Pelster J., Schöne C., Dickhäuser O. (2002). Die Skalen zur Erfassung von Lern- und Leistungsmotivation (SELLMO)[Measurement scales for learning and performance motivation] . Göttingen: Hogrefe. [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinmayr R., Amelang M. (2006). First results regarding the criterion validity of the I-S-T 2000 R concerning adults of both sex. Diagnostica 52 181–188. [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinmayr R., Spinath B. (2009). The importance of motivation as a predictor of school achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 19 80–90. 10.1016/j.lindif.2008.05.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinmayr R., Spinath B. (2010). Konstruktion und Validierung einer Skala zur Erfassung subjektiver schulischer Werte (SESSW) [construction and validation of a scale for the assessment of school-related values]. Diagnostica 56 195–211. 10.1026/0012-1924/a000023 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinmayr R., Weidinger A. F., Wigfield A. (2018). Does students’ grit predict their school achievement above and beyond their personality, motivation, and engagement? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 53 106–122. 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.02.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tonidandel S., LeBreton J. M. (2011). Relative importance analysis: a useful supplement to regression analysis. J. Bus. Psychol. 26 1–9. 10.1007/s10869-010-9204-3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Walton G. M., Spencer S. J. (2009). Latent ability grades and test scores systematically underestimate the intellectual ability of negatively stereotyped students. Psychol. Sci. 20 1132–1139. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02417.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weber H. S., Lu L., Shi J., Spinath F. M. (2013). The roles of cognitive and motivational predictors in explaining school achievement in elementary school. Learn. Individ. Differ. 25 85–92. 10.1016/j.lindif.2013.03.008 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weiner B. (1992). Human Motivation: Metaphors, Theories, and Research . Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wigfield A., Cambria J. (2010). Students’ achievement values, goal orientations, and interest: definitions, development, and relations to achievement outcomes. Dev. Rev. 30 1–35. 10.1016/j.dr.2009.12.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wigfield A., Eccles J. S., Yoon K. S., Harold R. D., Arbreton A., Freedman-Doan C., et al. (1997). Changes in children’s competence beliefs and subjective task values across the elementary school years: a three-year study. J. Educ. Psychol. 89 451–469. 10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.451 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wigfield A., Tonks S., Klauda S. L. (2016). “ Expectancy-value theory ,” in Handbook of Motivation in School , 2nd Edn eds Wentzel K. R., Mielecpesnm D. B. (New York, NY: Routledge; ), 55–74. [ Google Scholar ]

RCV Academy

Educating For Excellence! Making You Job Ready!

Research Motivation – Motivational factors for opting research

In this article, let us understand the research motivation or what are the key motivational factors for students who opt for research.

Research Motivation Reasons

The research motivation may be either due to one or more of the following reasons:

- The desire to get a research degree along with its significance.

- The desire to face challenges in solving the unsolved problems. For example, concern over practical problem initiates research.

- The desire to get the intellectual joy of doing some creative work.

- The desire to be finding solutions which service to society.

- The aspiration to get respectability.

However, this is not an exhaustive list of research motivation factors for people to undertake research studies.

Many more factors such as government directives, employment conditions, curiosity about new things, social thinking and awakening may as well motivate people to perform research operations.

Objectives of Research

The purpose of the research is to know the answers to questions through the application of scientific procedures.

The main aim is to find out the truth or to know the answer which has not be known yet.

Every research study has its own purpose, and research objectives can be classified into following broad groupings.

- To get familiar with a phenomenon or to achieve new insights into it (study with this object is termed as exploratory or formulative.

- To put accurately the characteristics of a particular individual, situation or a group (study with this object is known as descriptive research study).

- To determine the occurrence of which something happens or association with something else (study with this object is known as diagnostic research study).

- To test a hypothesis of a causal relationship between variables (the study is known as hypothesis-testing research studies).

Significance of Research

In the context of Hudson Maxim. Progress is possible with increased amounts of research.

Research instructs scientific and inductive thinking, and it promotes the development of logical habits of thinking and organization.

The increasingly sophisticated nature of business and government has focused their attention on the use of research in solving operational problems.

Nowadays, our economic system highly relies on the research to formulate the government policies.

For example, the budget of any country requires the analysis of people’s needs with expected expenditure required to meet those needs. In such conditions, research is heavily required to equate the cost of probable revenues to cover the cost of meeting people’s needs.

Research Process – Importance of knowing the process

Research methodology gives a student the necessary training in gathering material and arranging that information.

It also helps a student for participation in the field work whenever required.

It also trains in techniques for the collection of data which is appropriate to particular problems,

The research process also helps in the course of using statistics, questionnaires, controlled experimentation, recording evidence, sorting it out and interpreting it.

Importance of knowing the research methodology or how research is carried stems from the following considerations:

- The knowledge of methodology provides proper training especially to the new research worker and enables him to do better research.

- The methodology also helps the researcher to develop disciplined thinking or to observe the field objectively.

- Knowledge of how to do research will instruct the ability to estimate and use research results with reasonable confidence.

- Research methodology knowledge enables the consumers of research results to evaluate them and make rational decisions.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The impacts of learning motivation, emotional engagement and psychological capital on academic performance in a blended learning university course.

- 1 Hunan First Normal University, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 2 Department of Agricultural Education & Communications, College of Agricultural Sciences & Natural Resources, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, United States

- 3 Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China

The final, formatted version of the article will be published soon.

Select one of your emails

You have multiple emails registered with Frontiers:

Notify me on publication

Please enter your email address:

If you already have an account, please login

You don't have a Frontiers account ? You can register here

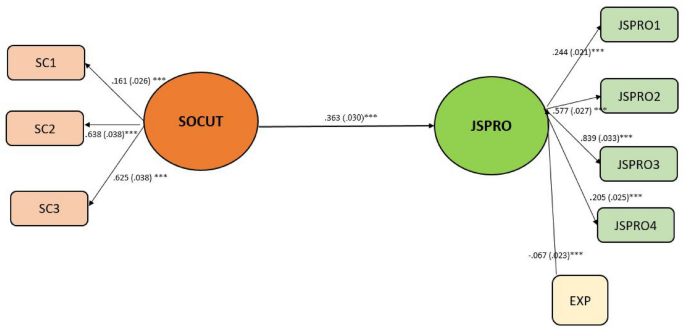

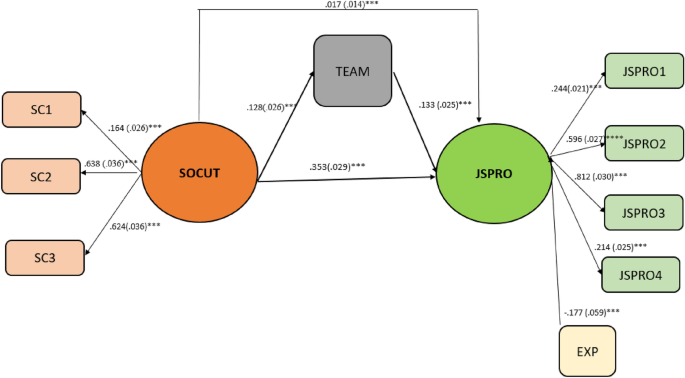

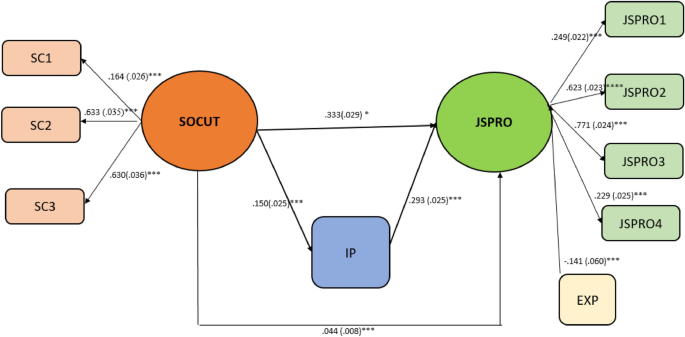

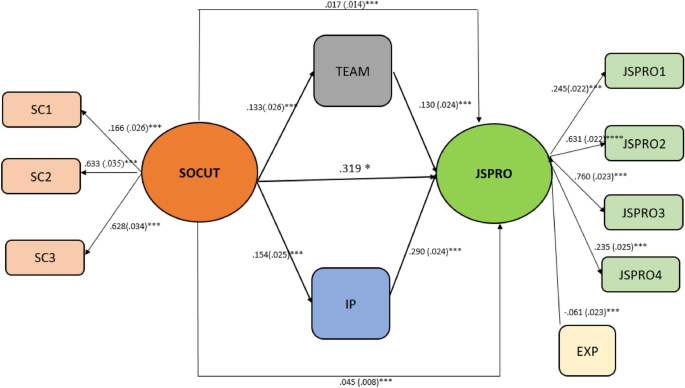

This study aims to explore the relationships among psychological capital, learning motivation, emotional engagement, and academic performance for college students in a blended learning environment.The research consists of two studies: Study 1 primarily focuses on validating, developing, revising, and analyzing the psychometric properties of the scale using factor analysis, while Study 2 employs structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the hypotheses of relationships of included variables and draw conclusions based on 745 data collected in a university in China.Results: Findings revealed that intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, emotional engagement, and psychological capital all impact academic performance. Extrinsic learning motivation has significant positive direct effects on intrinsic learning motivation, emotional engagement, and psychological capital. Intrinsic motivation mediates the relationship between extrinsic motivation and academic performance.Discussion: In future blended learning practices, it is essential to cultivate students' intrinsic learning motivation while maintaining a certain level of external learning motivation. It is also crucial to stimulate and maintain students' emotional engagement, enhance their sense of identity and belonging, and recognize the role of psychological capital in learning to boost students' confidence, resilience, and positive emotions.

Keywords: Psychological Capital, Learning motivation, emotional engagement, academic performance, Blended Learning

Received: 19 Dec 2023; Accepted: 25 Apr 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 Liu, Ma and CHEN. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Yan Liu, Hunan First Normal University, Changsha, Hunan, China Shuai Ma, Department of Agricultural Education & Communications, College of Agricultural Sciences & Natural Resources, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, 79409, Texas, United States YUE CHEN, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Changes in Undergraduate Students’ Self-Efficacy and Outcome Expectancy in an Introductory Statistics Course

Article sidebar.

Main Article Content

The exploration of psychological variables that potentially impact college student performance in challenging academic courses can be useful for understanding success in introductory statistics. Although previous research has examined specific beliefs that students hold about their abilities and future outcomes, the current study is novel in its examination of changes in both self-efficacy (SE) and outcome expectancy (OE) in relation to performance over the course of an undergraduate introductory psychology statistics course. These psychological variables—relating to one’s belief about one’s ability to accomplish a task and the anticipated outcomes—may impact student motivation and performance. Students’ SE, OE, and other variables related to statistics performance were measured through a survey administered at the beginning and end of the course. Multivariate logistic regression and McNemar tests were conducted to examine factors that affected changes in SE and OE as the semester progressed. Students with lower scores on the final exam demonstrated a decrease in both high SE and positive OE. However, higher scores on exams earlier in the course were associated with increased odds for high SE but not for positive OE, suggesting that SE is less resilient to course performance. Based on these findings, the authors recommend that statistics instructors identify students at risk for decreasing SE. Instructors can help foster high SE in students struggling academically by connecting the course content to their everyday lives and suggesting strategies to enhance their confidence in their content knowledge and increase their comfort in navigating such a challenging course.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License .

- Open access

- Published: 24 April 2024

Breast cancer screening motivation and behaviours of women aged over 75 years: a scoping review

- Virginia Dickson-Swift 1 ,

- Joanne Adams 1 ,

- Evelien Spelten 1 ,

- Irene Blackberry 2 ,

- Carlene Wilson 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Eva Yuen 3 , 6 , 7 , 8

BMC Women's Health volume 24 , Article number: 256 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

27 Accesses

Metrics details

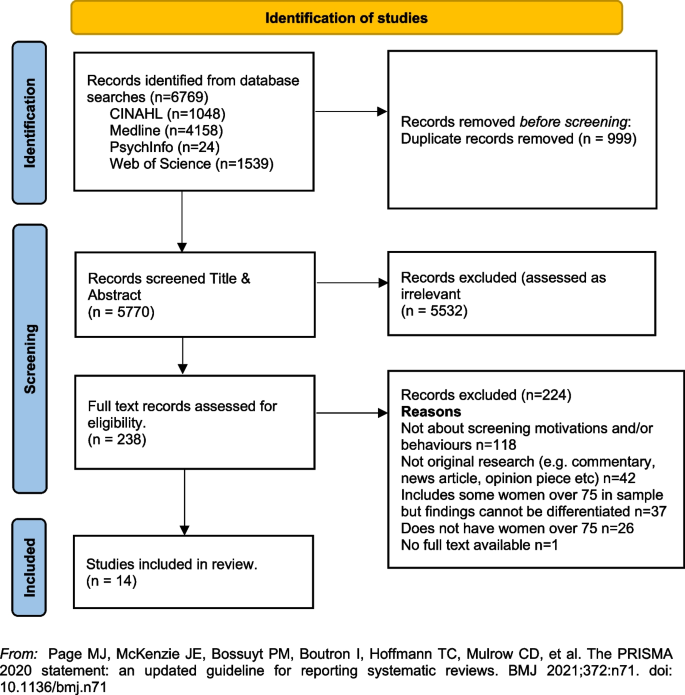

This scoping review aimed to identify and present the evidence describing key motivations for breast cancer screening among women aged ≥ 75 years. Few of the internationally available guidelines recommend continued biennial screening for this age group. Some suggest ongoing screening is unnecessary or should be determined on individual health status and life expectancy. Recent research has shown that despite recommendations regarding screening, older women continue to hold positive attitudes to breast screening and participate when the opportunity is available.

All original research articles that address motivation, intention and/or participation in screening for breast cancer among women aged ≥ 75 years were considered for inclusion. These included articles reporting on women who use public and private breast cancer screening services and those who do not use screening services (i.e., non-screeners).

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews was used to guide this review. A comprehensive search strategy was developed with the assistance of a specialist librarian to access selected databases including: the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline, Web of Science and PsychInfo. The review was restricted to original research studies published since 2009, available in English and focusing on high-income countries (as defined by the World Bank). Title and abstract screening, followed by an assessment of full-text studies against the inclusion criteria was completed by at least two reviewers. Data relating to key motivations, screening intention and behaviour were extracted, and a thematic analysis of study findings undertaken.

A total of fourteen (14) studies were included in the review. Thematic analysis resulted in identification of three themes from included studies highlighting that decisions about screening were influenced by: knowledge of the benefits and harms of screening and their relationship to age; underlying attitudes to the importance of cancer screening in women's lives; and use of decision aids to improve knowledge and guide decision-making.

The results of this review provide a comprehensive overview of current knowledge regarding the motivations and screening behaviour of older women about breast cancer screening which may inform policy development.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Breast cancer is now the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the world overtaking lung cancer in 2021 [ 1 ]. Across the globe, breast cancer contributed to 25.8% of the total number of new cases of cancer diagnosed in 2020 [ 2 ] and accounts for a high disease burden for women [ 3 ]. Screening for breast cancer is an effective means of detecting early-stage cancer and has been shown to significantly improve survival rates [ 4 ]. A recent systematic review of international screening guidelines found that most countries recommend that women have biennial mammograms between the ages of 40–70 years [ 5 ] with some recommending that there should be no upper age limit [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ] and others suggesting that benefits of continued screening for women over 75 are not clear [ 13 , 14 , 15 ].

Some guidelines suggest that the decision to end screening should be determined based on the individual health status of the woman, their life expectancy and current health issues [ 5 , 16 , 17 ]. This is because the benefits of mammography screening may be limited after 7 years due to existing comorbidities and limited life expectancy [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ], with some jurisdictions recommending breast cancer screening for women ≥ 75 years only when life expectancy is estimated as at least 7–10 years [ 22 ]. Others have argued that decisions about continuing with screening mammography should depend on individual patient risk and health management preferences [ 23 ]. This decision is likely facilitated by a discussion between a health care provider and patient about the harms and benefits of screening outside the recommended ages [ 24 , 25 ]. While mammography may enable early detection of breast cancer, it is clear that false-positive results and overdiagnosis Footnote 1 may occur. Studies have estimated that up to 25% of breast cancer cases in the general population may be over diagnosed [ 26 , 27 , 28 ].

The risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer increases with age and approximately 80% of new cases of breast cancer in high-income countries are in women over the age of 50 [ 29 ]. The average age of first diagnosis of breast cancer in high income countries is comparable to that of Australian women which is now 61 years [ 2 , 4 , 29 ]. Studies show that women aged ≥ 75 years generally have positive attitudes to mammography screening and report high levels of perceived benefits including early detection of breast cancer and a desire to stay healthy as they age [ 21 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. Some women aged over 74 participate, or plan to participate, in screening despite recommendations from health professionals and government guidelines advising against it [ 33 ]. Results of a recent review found that knowledge of the recommended guidelines and the potential harms of screening are limited and many older women believed that the benefits of continued screening outweighed the risks [ 30 ].

Very few studies have been undertaken to understand the motivations of women to screen or to establish screening participation rates among women aged ≥ 75 and older. This is surprising given that increasing age is recognised as a key risk factor for the development of breast cancer, and that screening is offered in many locations around the world every two years up until 74 years. The importance of this topic is high given the ambiguity around best practice for participation beyond 74 years. A preliminary search of Open Science Framework, PROSPERO, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and JBI Evidence Synthesis in May 2022 did not locate any reviews on this topic.

This scoping review has allowed for the mapping of a broad range of research to explore the breadth and depth of the literature, summarize the evidence and identify knowledge gaps [ 34 , 35 ]. This information has supported the development of a comprehensive overview of current knowledge of motivations of women to screen and screening participation rates among women outside the targeted age of many international screening programs.

Materials and methods

Research question.

The research question for this scoping review was developed by applying the Population—Concept—Context (PCC) framework [ 36 ]. The current review addresses the research question “What research has been undertaken in high-income countries (context) exploring the key motivations to screen for breast cancer and screening participation (concepts) among women ≥ 75 years of age (population)?

Eligibility criteria

Participants.

Women aged ≥ 75 years were the key population. Specifically, motivations to screen and screening intention and behaviour and the variables that discriminate those who screen from those who do not (non-screeners) were utilised as the key predictors and outcomes respectively.

From a conceptual perspective it was considered that motivation led to behaviour, therefore articles that described motivation and corresponding behaviour were considered. These included articles reporting on women who use public (government funded) and private (fee for service) breast cancer screening services and those who do not use screening services (i.e., non-screeners).

The scope included high-income countries using the World Bank definition [ 37 ]. These countries have broadly similar health systems and opportunities for breast cancer screening in both public and private settings.

Types of sources

All studies reporting original research in peer-reviewed journals from January 2009 were eligible for inclusion, regardless of design. This date was selected due to an evaluation undertaken for BreastScreen Australia recommending expansion of the age group to include 70–74-year-old women [ 38 ]. This date was also indicative of international debate regarding breast cancer screening effectiveness at this time [ 39 , 40 ]. Reviews were also included, regardless of type—scoping, systematic, or narrative. Only sources published in English and available through the University’s extensive research holdings were eligible for inclusion. Ineligible materials were conference abstracts, letters to the editor, editorials, opinion pieces, commentaries, newspaper articles, dissertations and theses.

This scoping review was registered with the Open Science Framework database ( https://osf.io/fd3eh ) and followed Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews [ 35 , 36 ]. Although ethics approval is not required for scoping reviews the broader study was approved by the University Ethics Committee (approval number HEC 21249).

Search strategy