Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Research Guides

Multiple Case Studies

Nadia Alqahtani and Pengtong Qu

Description

The case study approach is popular across disciplines in education, anthropology, sociology, psychology, medicine, law, and political science (Creswell, 2013). It is both a research method and a strategy (Creswell, 2013; Yin, 2017). In this type of research design, a case can be an individual, an event, or an entity, as determined by the research questions. There are two variants of the case study: the single-case study and the multiple-case study. The former design can be used to study and understand an unusual case, a critical case, a longitudinal case, or a revelatory case. On the other hand, a multiple-case study includes two or more cases or replications across the cases to investigate the same phenomena (Lewis-Beck, Bryman & Liao, 2003; Yin, 2017). …a multiple-case study includes two or more cases or replications across the cases to investigate the same phenomena

The difference between the single- and multiple-case study is the research design; however, they are within the same methodological framework (Yin, 2017). Multiple cases are selected so that “individual case studies either (a) predict similar results (a literal replication) or (b) predict contrasting results but for anticipatable reasons (a theoretical replication)” (p. 55). When the purpose of the study is to compare and replicate the findings, the multiple-case study produces more compelling evidence so that the study is considered more robust than the single-case study (Yin, 2017).

To write a multiple-case study, a summary of individual cases should be reported, and researchers need to draw cross-case conclusions and form a cross-case report (Yin, 2017). With evidence from multiple cases, researchers may have generalizable findings and develop theories (Lewis-Beck, Bryman & Liao, 2003).

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Lewis-Beck, M., Bryman, A. E., & Liao, T. F. (2003). The Sage encyclopedia of social science research methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Key Research Books and Articles on Multiple Case Study Methodology

Yin discusses how to decide if a case study should be used in research. Novice researchers can learn about research design, data collection, and data analysis of different types of case studies, as well as writing a case study report.

Chapter 2 introduces four major types of research design in case studies: holistic single-case design, embedded single-case design, holistic multiple-case design, and embedded multiple-case design. Novice researchers will learn about the definitions and characteristics of different designs. This chapter also teaches researchers how to examine and discuss the reliability and validity of the designs.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches . Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

This book compares five different qualitative research designs: narrative research, phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, and case study. It compares the characteristics, data collection, data analysis and representation, validity, and writing-up procedures among five inquiry approaches using texts with tables. For each approach, the author introduced the definition, features, types, and procedures and contextualized these components in a study, which was conducted through the same method. Each chapter ends with a list of relevant readings of each inquiry approach.

This book invites readers to compare these five qualitative methods and see the value of each approach. Readers can consider which approach would serve for their research contexts and questions, as well as how to design their research and conduct the data analysis based on their choice of research method.

Günes, E., & Bahçivan, E. (2016). A multiple case study of preservice science teachers’ TPACK: Embedded in a comprehensive belief system. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11 (15), 8040-8054.

In this article, the researchers showed the importance of using technological opportunities in improving the education process and how they enhanced the students’ learning in science education. The study examined the connection between “Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge” (TPACK) and belief system in a science teaching context. The researchers used the multiple-case study to explore the effect of TPACK on the preservice science teachers’ (PST) beliefs on their TPACK level. The participants were three teachers with the low, medium, and high level of TPACK confidence. Content analysis was utilized to analyze the data, which were collected by individual semi-structured interviews with the participants about their lesson plans. The study first discussed each case, then compared features and relations across cases. The researchers found that there was a positive relationship between PST’s TPACK confidence and TPACK level; when PST had higher TPACK confidence, the participant had a higher competent TPACK level and vice versa.

Recent Dissertations Using Multiple Case Study Methodology

Milholland, E. S. (2015). A multiple case study of instructors utilizing Classroom Response Systems (CRS) to achieve pedagogical goals . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3706380)

The researcher of this study critiques the use of Classroom Responses Systems by five instructors who employed this program five years ago in their classrooms. The researcher conducted the multiple-case study methodology and categorized themes. He interviewed each instructor with questions about their initial pedagogical goals, the changes in pedagogy during teaching, and the teaching techniques individuals used while practicing the CRS. The researcher used the multiple-case study with five instructors. He found that all instructors changed their goals during employing CRS; they decided to reduce the time of lecturing and to spend more time engaging students in interactive activities. This study also demonstrated that CRS was useful for the instructors to achieve multiple learning goals; all the instructors provided examples of the positive aspect of implementing CRS in their classrooms.

Li, C. L. (2010). The emergence of fairy tale literacy: A multiple case study on promoting critical literacy of children through a juxtaposed reading of classic fairy tales and their contemporary disruptive variants . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3572104)

To explore how children’s development of critical literacy can be impacted by their reactions to fairy tales, the author conducted a multiple-case study with 4 cases, in which each child was a unit of analysis. Two Chinese immigrant children (a boy and a girl) and two American children (a boy and a girl) at the second or third grade were recruited in the study. The data were collected through interviews, discussions on fairy tales, and drawing pictures. The analysis was conducted within both individual cases and cross cases. Across four cases, the researcher found that the young children’s’ knowledge of traditional fairy tales was built upon mass-media based adaptations. The children believed that the representations on mass-media were the original stories, even though fairy tales are included in the elementary school curriculum. The author also found that introducing classic versions of fairy tales increased children’s knowledge in the genre’s origin, which would benefit their understanding of the genre. She argued that introducing fairy tales can be the first step to promote children’s development of critical literacy.

Asher, K. C. (2014). Mediating occupational socialization and occupational individuation in teacher education: A multiple case study of five elementary pre-service student teachers . Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Order Number 3671989)

This study portrayed five pre-service teachers’ teaching experience in their student teaching phase and explored how pre-service teachers mediate their occupational socialization with occupational individuation. The study used the multiple-case study design and recruited five pre-service teachers from a Midwestern university as five cases. Qualitative data were collected through interviews, classroom observations, and field notes. The author implemented the case study analysis and found five strategies that the participants used to mediate occupational socialization with occupational individuation. These strategies were: 1) hindering from practicing their beliefs, 2) mimicking the styles of supervising teachers, 3) teaching in the ways in alignment with school’s existing practice, 4) enacting their own ideas, and 5) integrating and balancing occupational socialization and occupational individuation. The study also provided recommendations and implications to policymakers and educators in teacher education so that pre-service teachers can be better supported.

Multiple Case Studies Copyright © 2019 by Nadia Alqahtani and Pengtong Qu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 January 2022

An embedded multiple case study: using CFIR to map clinical food security screening constructs for the development of primary care practice guidelines

- Sabira Taher ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5368-2998 1 ,

- Naoko Muramatsu 2 ,

- Angela Odoms-Young 3 ,

- Nadine Peacock 2 ,

- C. Fagen Michael 1 &

- K. Suh Courtney 4

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 97 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2642 Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

Food insecurity (FI), the limited access to healthy food to live an active and healthy life, is a social determinant of health linked to poor dietary health and difficulty with disease management in the United States (U.S.). Healthcare experts support the adoption of validated screening tools within primary care practice to identify and connect FI patients to healthy and affordable food resources. Yet, a lack of standard practices limits uptake. The purpose of this study was to understand program processes and outcomes of primary care focused FI screening initiatives that may guide wide-scale program implementation.

This was an embedded multiple case study of two primary care-focused initiatives implemented in two diverse health systems in Chicago and Suburban Cook County that routinely screened patients for FI and referred them to onsite food assistance programs. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research and an iterative process were used to collect/analyze qualitative data through semi-structured interviews with N = 19 healthcare staff. Intended program activities, outcomes, actors, implementation barriers/facilitators and overarching implementation themes were identified as a part of a cross-case analysis.

Programs outcomes included: the number of patients screened, identified as FI and that participated in the onsite food assistance program. Study participants reported limited internal resources as implementation barriers for program activities. The implementation climate that leveraged the strength of community collaborations and aligned internal, implementation climate were critical facilitators that contributed to the flexibility of program activities that were tailored to fill gaps in resources and meet patient and clinician needs.

Highly adaptable programs and the healthcare context enhanced implementation feasibility across settings. These characteristics can support program uptake in other settings, but should be used with caution to preserve program fidelity. A foundational model for the development and testing of standard clinical practice was the product of this study.

Peer Review reports

- Food insecurity

Food insecurity (hereafter FI) is a social determinant of health and economic condition where limited access to safe, high-quality, nutritious food prevents individuals from leading active and healthy lives [ 1 ]. The World Bank estimated that acute food insecurity increased drastically and on a global scale due to COVID-19, and that the majority of these cases were connected to hunger in International Development Association countries driven by climate change, long-lasting conflict, and other economic conditions [ 2 ]. Low levels of education and limited social networks were consistent variables across countries that increased the risk for FI. Yet, country-specific economic, political and sociocultural factors varied greatly between countries, which highlights the need to utilize country-specific interventions and policies to reduce FI on a local level [ 3 ]. This study specifically focuses on FI and the healthcare context in the U.S., which, when compared to peer nations, has the highest number of preventable chronic illnesses related to poor nutrition, as well as hospitalizations and deaths [ 4 ].

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 33.5 million Americans experienced FI [ 1 ]. Since April 2020, that number has nearly doubled [ 5 ].. FI in the U.S. is characterized by the overconsumption of poor quality, highly processed, calorie dense food that is extremely affordable and widely available [ 6 ]. U.S. households most affected by FI are low-income, ethnic and minority communities, especially those affected by unemployment and job loss [ 7 ] FI contributes to the limited ability to eat a healthy diet, often the first recommended step for disease management. Thus FI contributes to the high prevalence of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and difficulty with disease management among low-income U.S. populations [ 6 ].

Recommendations for screening and linking patients

Studies show that local and federal U.S. food assistance services remain underutilized due to limited awareness about their existence, the stigma associated with using welfare programs, and complex enrollment processes that can discourage use [ 1 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. There is a growing body of evidence that illustrates how partnerships between healthcare systems and local food assistance programs can increase the use of services and help improve dietary health [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Research shows that recommendations for identifying FI patients through routine FI screening with the validated Hunger Vital Signs™ tool, and referring patients to evidence-based programs, such the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (hereafter SNAP) and community food pantries, increases the use of food assistance services, and has demonstrated immediate dietary improvements in cancer, diabetes and hypertensive patients [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

Addressing food insecurity in primary care practice

Among screening initiatives that exist, those implemented in primary care settings demonstrate the most potential to address FI because primary care practice is the most common form of health care delivery in the U.S. Moreover, primary care is recognized by professional and government healthcare organizations as the most typical setting where referrals to social and community resources often occur that connect patients to basic needs for disease management [ 8 , 16 , 17 , 18 ].

Lack of evidence that points to improved health outcomes

Existing literature points to FI screening practices that are largely guided by broad, national principles that have been interpreted in many ways—perhaps due to their rapid and organic evolution to fill a growing FI crisis. Evidence suggests that program activities, actors, implementation processes are driven by each healthcare contexts, program outcomes vary across clinical settings, and as a result, the long-term impact on health outcomes of screening programs cannot be determined [ 9 , 19 , 20 ]. The challenge stems from the lack of translational research and rigorously tested standard practices in this relatively new area of clinical practice [ 20 , 21 ]. The gaps in the literature suggest that we need to examine how these programs operate in real-world settings, and identify which program activities have the most potential for generalization. This can inform the development of practice guidelines that can be tested in effectiveness trials, and eventually implemented and tested on a wider scale.

Implementation science

In implementation science, theory derived frameworks are used to study implementation context—specifically how multilevel system wide factors (e.g. individual level organizational level) and multisector factors (i.e. policies, external partnerships and community needs) interact and determine the quality of implementation outcomes [ 22 ]. Findings from implementation science studies allow researchers to hypothesize the relationship between implementation factors. These contextual variables can be tested in other settings where program adaptations maybe considered that lend themselves to wide-scale dissemination of evidence-based practice [ 22 ].

Implementation science research has been supported in several healthcare research studies, most notably by the National Institutes of Health for a variety of social and behavioral health research, such as tobacco cessation and diabetes prevention. The purpose of these studies was to understand how the complex and interdependent sociocultural, economic and political factors within the implementation context affected the process of program implementation. There is an opportunity to apply implementation science in the context of clinical FI initiatives because theoretical underpinnings of implementation have not yet been explored. Ultimately, researchers used findings to determine how to effectively disseminate and adapt these programs into other healthcare settings and contexts [ 22 , 23 ].

- Consolidated framework for implementation research

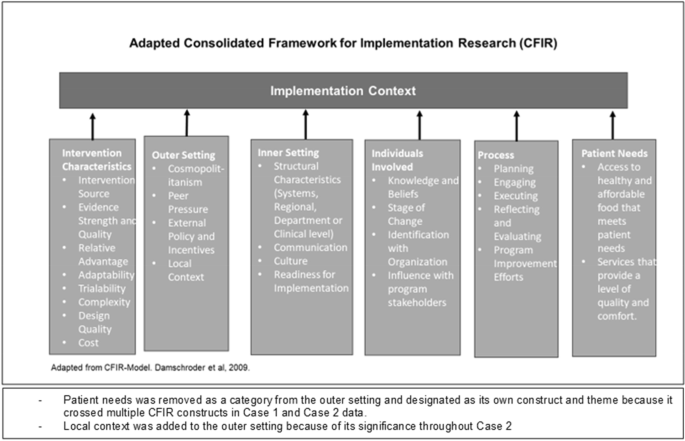

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (hereafter CFIR) is an Implementation determinants framework comprised of theoretically derived domains and constructs as seen in Table 1 . CFIR has been empirically tested and is widely used in healthcare settings to understand multidimensional, interrelated implementation barriers and facilitators within specific healthcare organizations [ 24 , 25 , 26 ].

The framework is broad with over 30 theoretically-derived constructs. When used to map implementation factors, CFIR can help researchers establish a foundation from which semantic relationships between implementation factors can be constructed. Hypothesized relationships between constructs can be used to develop a conceptual model that describes the implementation of a specific intervention. The framework is made up of implementation drivers that are categorized into five domains: 1) The intervention characteristics that point to the quality of the program, compatible design, its cost and adaptability across settings. 2) The inner setting, which directly relates to the physical and cultural setting where daily program processes occur. 3) The outer setting, which refers to any factor external to the program itself, including community needs, influences, local mandates, policies or regulations that affect implementation processes. 4) Characteristics of program staff/individuals, which are their knowledge and beliefs about the program from their own perspective. 5) Implementation processes, which include the steps used in planning, execution and ongoing management of the program [ 22 ].

The purpose of this study was to understand implementation processes and outcomes of two distinctively different FI screening initiatives. One program was implemented in primary care clinics located within the context of an urban, government funded health system. The other program was implemented in primary care clinics associated with a suburban, private, academic medical center. A total of N = 19 healthcare staff participated in one-on-one interviews in this study to provide their perspectives about implementation. We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to identify common implementation barriers and facilitators from each interview as a part of a cross-case analysis. Findings from this study were used to develop a formative conceptual model that can guide the development, refinement and testing of standard screening practices in future research.

Selection of study cases

Cook County is located in Illinois, a state located in the Midwestern region of the U.S. Within Cook County is a complex healthcare network that serves 5.2 million people. Two FI screening and referral programs were selected for this study using criterion sampling from a larger sample of 13 programs implemented within primary care settings identified in a previous study. The two programs selected for this study (hereafter Program A and Program B) differed in the type of setting (i.e. one public, government funded organization, the other an academic medical center). Distinct program differences listed in Table 1 allowed for the exploration of program implementation in different contexts and the extraction of common, overarching implementation themes.

Inclusion criteria were based on previous research and national recommendations for clinical FI screening initiatives [ 8 , 17 , 18 , 27 ]. Study cases met the following criteria: 1) Programs that utilized the standardized two question Hunger Vital Signs tool to screen patients for FI; 2) Programs that incorporated a referral system to onsite food services for FI patients; 3) Programs that incorporated a referral system for FI to enroll in SNAP and other federal benefits; 4) Programs that had been implemented for a minimum of one year. The last criterion allowed for the examination of programs that had been presumably functioning long enough that initial challenges common to start-up programs had already been addressed.

Study design

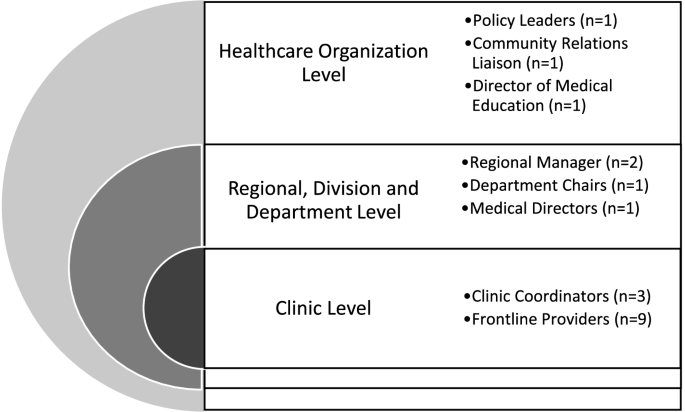

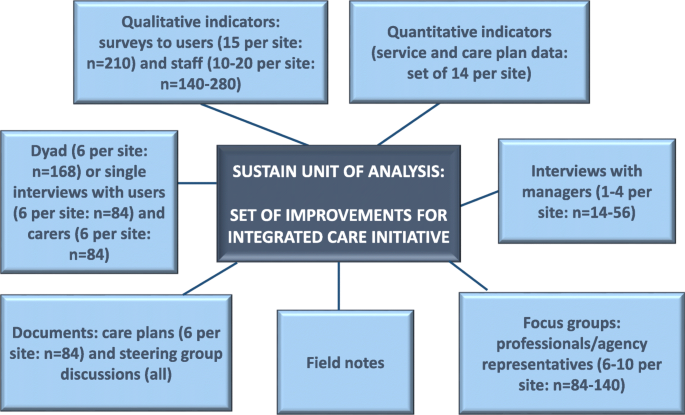

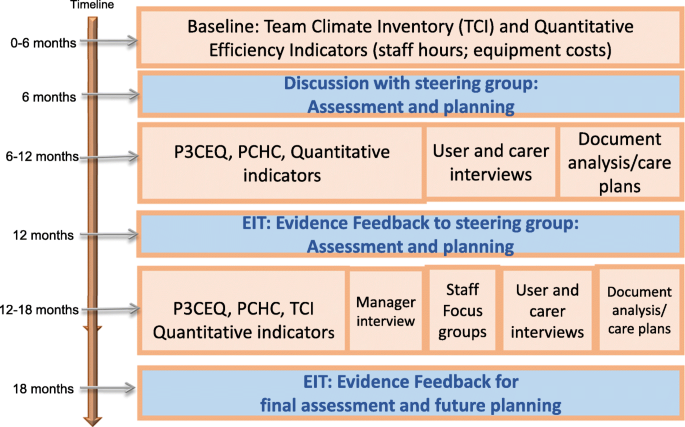

An embedded multiple case study design was used to examine the phenomenon of primary care situated FI screening and referral processes [ 28 , 29 ]. The embedded nature of this study refers to the multiple units of analysis within each case [ 29 ]. Preliminary research for this study indicated that the healthcare context (e.g. clinicians at the practice level) drove how FI screening programs were implemented and what types of food assistance programs were incorporated for referral. Therefore, each case in this study was identified as one individual screening initiative and the units of analysis were clinical program actors within the healthcare setting as illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Units of analysis across healthcare organizations in this study ( N = 19)

Participants

From September 2019 to March 2020, an iterative sampling approach was used to recruit participants for this study from a convenience sample of implementation actors at each case until data saturation was achieved (N = 19). Through a purposive sampling process, implementation leaders, clinicians and other healthcare staff critical to program implementation were recruited for this study [ 30 ].

Study instrument and data collection

The interview guides used with organizational leaders and frontline providers were developed for this study using the adapted CFIR framework (available in Additional File 1 “Interview Guide for Key Program Planners” and “Frontline Provider Interview Guide”). As in similar research, interview questions broadly asked about program activities, implementation processes, program outcomes and asked participants to identify major challenges/facilitators that affected feasibility and fidelity of program implementation [ 31 ].

A trained qualitative researcher (ST) conducted semi-structured, key informant interviews for this study. The interviews were conducted face-to-face at each program site or over the telephone at the study participant’s discretion. Each interview lasted 30–45 min and were audio recorded for data analysis purposes. Participants recruited for the study were made aware of the audio recording at the beginning of each session and were required to provide verbal consent prior to participation in the study. This study and the verbal consent process were approved for a claim of exemption (Protocol # 2019–0610) from the University of Illinois at Chicago Office for the Protection of Research Subjects Institutional Review Board on August 30, 2019.

The researcher took detailed notes during each interview that provided initial insights to the study. Revisions to the instrument guide were made after each interview for clarity and to collect additional program details.

Data collection, coding and analysis

Data were collected, managed and analyzed concurrently over a period of seven months until data saturation was achieved. Transcriptions of the interviews were uploaded to Atlas.ti v.8 Qualitative Data Analysis Software for data management, coding and assistance with analysis. All personal identifying information was removed from the data prior to analysis. All data were stored on a password protected computer only accessible by the researcher. A codebook developed a priori based on the adapted CFIR framework for data interpretation was used during data collection and analysis (see Additional File 2 , “Study Codebook”). Codes were added to or removed from the codebook based on previous research, organizational theory, and as new ideas and concepts emerged, illustrated in Fig. 2 [ 9 , 32 , 33 ].

Adapted CFIR framework for this study

Two experienced PhD level university students (ST and LC) established interrater reliability of the coding process until 80% agreement was achieved as recommended for qualitative research [ 34 ]. As data were collected, memos were used to document progress, study decisions and emerging themes [ 35 ]. Matrices and frameworks were developed to guide thematic analysis and anchor emerging concepts to specific CFIR constructs [ 36 ]. The themes and patterns that emerged from each interview were compared to previous interview findings. This allowed the identification of commonalities, disparities and outliers in the data and for a rich understanding of program implementation to emerge [ 28 ].

For each case, program activities, time of occurrence and implementation actors were confirmed. Implementation processes were also described as originally intended, as well as unanticipated implementation facilitators and challenges and the unique implementation context that resulted in program adaptations.

Program outcomes were also collected to assess implementation feasibility, effectiveness, as well as overall program fidelity [ 31 , 37 ]. The following program outcomes were identified across cases: the number of patients screened; the number that identified as FI; the number of patients referred to food assistance programs; the number of patients that participated in the food assistance program. The frequency that clinicians completed essential program activities was also collected to tie outcomes to specific program elements. During the cross-case analysis, the binding implementation themes were identified and gave meaning to program outcomes.

Atlas.ti v8 exploratory functions were used to further analyze and confirm findings, and for source triangulation between participants. Any overlap of themes helped to establish the semantic relationships between CFIR constructs. Prior to the finalization of study results, one program leader and one clinician from each case were asked to participate in member-checks. They each reviewed the results from their respective case, and provided feedback where necessary to ensure validity of study findings.

Program activities and process outcomes

Study findings revealed similar intended program activities and processes within and across cases illustrated in Tables 2 and 3 .

Both cases intended to screen all of their patients for FI using their EMR systems and projected that 45% of their patient population would be identified as FI based on previous community-wide data [ 38 ]. Across cases, screening took place by a clinician approximately one time a year prior to the doctor’s visit during intake or in the clinic waiting room. Positive responses were documented and flagged in the patient’s medical record to prompt the physician to discuss FI during the patient visit. Between 24 and 31% of patients were actually identified through screening and were referred to an onsite food distribution program that provided fresh produce at no cost to FI patients. During the doctor’s visit, all patients identified as FI were projected to receive information or list about local food assistance resources and should have been referred to the Social Worker to enroll in SNAP benefits if eligible. These data were either unavailable for this study or this program activity was not performed.

Clinicians across cases intended to use phone call reminders as an opportunity to remind and educate FI patients about the benefits of participating in the food distribution programs. Between 8 and 22% of patients received phone call reminders.

Thematic analysis findings

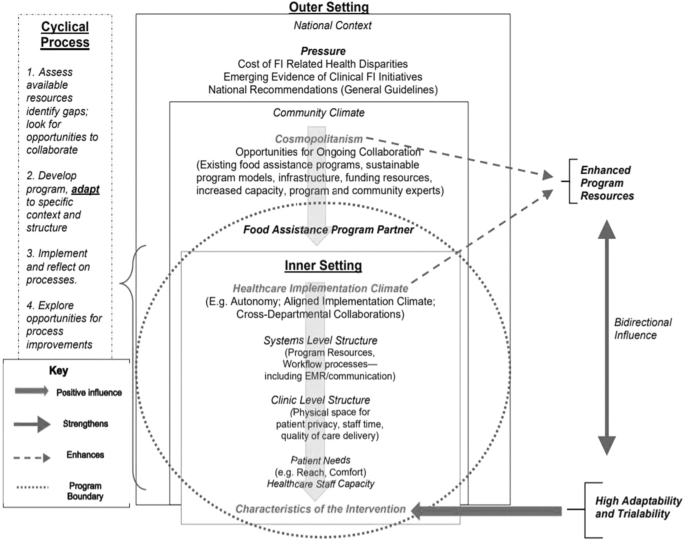

Figure 3 represents a formative conceptual model utilizing CFIR concepts that sums up overarching themes described below. The model illustrates the semantic relationships between core CFIR concepts revealed during thematic analysis that helps to explain why process outcomes were lower than projected.

Formative conceptual model for implementation

Barriers within the inner setting

Clinicians across cases reported that physical space, clinician capacity, financial resources and EMR technology were resource challenges that inhibited program implementation. The study revealed a hierarchical relationship where barriers study participants identified trickled down from the organizational systems level that resulted in challenges with the delivery of care at the clinic level and ultimately affected how patients experienced FI screening and referral processes as seen in Fig. 3 . Identified in similar intervention studies, these challenges speak to the broader applicability of study findings to other U.S. healthcare settings [ 39 ].

Study participants agreed that due to their health system’s pre-programmed EMR software, clinician prompts for FI screening and resource lists were not functional for the realities of day-to-day clinical care. Study participants reported that electronic screening tools were either unavailable or were only available intermittently (e.g. once per year), which did not allow for clinicians to capture the episodic and cyclical nature of FI. Resource lists were embedded so deeply within the EMR system that study participants also reported that they did not have time to navigate to those lists during patient visits.

Limited financial resources that health systems could allocate to screening and referral initiatives negatively affected the frequency of food distribution, program sustainability and reach. Study participants reported that screening and referral programs were supported by a finite amount of in-kind donations from their community food assistance partner and local and federal grants. As a result, funding would last for only a fixed amount of time, and study participants reported that the money just did not pay for enough food meet patient needs. Moreover, grant dollars had spending restrictions, and required patients to be enrolled in SNAP benefits. Study participants reported that because of this spending rule, they had to turn several of their low-income patients away during program activities if they were not eligible for SNAP benefits, which negatively affected program reach.

Rigid workflow processes across cases provided a small window of opportunity for FI screening and referral during the patient visit. Study participants said that check-in and intake were activities that occurred in settings with very little privacy, but indicated that this was typical for how clinic waiting room or nurse’s intake stations functioned. Physical space became a barrier to screening, referral and food distribution. Across cases, patients displayed discomfort when presented with FI questions, which study participants believed was because of the lack of privacy from other patients. Some patients commonly denied experiencing FI, even if clinicians knew that this was not the case. A lack of privacy could explain why a lower than expected number of patients were identified as FI, and were referred to and participated in the food distribution programs.

Study participants reported that clinician capacity to deliver patient care was dependent on the health system’s workflow, and consistently reported that its rigidity did not provide enough time to distribute food assistance resource lists and counsel patients about FI. Clinicians also reported the inability to conduct patient outreach and phone calls for the purpose of increasing awareness about when food distribution was scheduled—an important component for increasing program reach. This finding could explain why there were lower than expected number of patients participated in the food distribution programs overall.

Leveraging the implementation context as a facilitator

Across cases, study participants reported that the support of community partnerships and the internal work culture created an aligned implementation context. As seen in Fig. 3 , the community climate—cosmopolitanism—played a big role during program planning and execution and clinic-level autonomy allowed clinicians to make timely program adaptations when faced with resource challenges.

Multi-sector networks supported inherent synergy with existing community initiatives, which gave each health system access to an existing program model, expertise and infrastructure. The local food justice organization and food depository that partnered with the health systems advocated for an equitable and sustainable food system through existing initiatives throughout the community and played a fundamental role in bringing together health systems, local food growers and other health and wellness community organizations; the collective strength and presence of which created a supportive implementation climate where study participants reported an activation of knowledge, awareness and advocacy work among clinical staff in preparation for program implementation.

For example, study participants reported the presence of farm stands across the health system campus, medical and dietetics students involved in program activities, the use of offsite community centers to increase program participation and the assistance of local grant opportunities to increase food production and reach.

A culture of clinic-level autonomy facilitated the equitable distribution of decision-making authority. “Managers need to take ownership because they know their patients and their staff,” said one study participant and in turn, when asked about this, clinicians responded with, “We do things differently here,” and “the way we do it is we want to reach everyone…” Statements of this kind referred to linkages, voucher activities and food distribution processes that study participants reported were adapted for universal distribution to reduce the stigma of FI. This adaptation could explain why the number of patients that participated in food distribution programs were much greater than the number of phone call reminders, and SNAP enrollment activities that clinicians actually engaged in.

Adaptability and trialability of program characteristics

Study participants reported that program activities were highly adaptable and testable. Adaptability refers to the degree to which the core program components can be tailored to fit the implementation context [ 22 ]. Trialability refers to the ability for stakeholders to pilot an intervention on a small scale and engaged in quality improvement efforts [ 22 ]. As seen in Fig. 3 , both constructs emerged in the context of limited program resources. It appeared that when limited program resources were supplemented, high levels of adaptability and trialability characteristics were revealed. Conversely, the high level of adaptability and trialability of each program allowed for ongoing exploration of alternative and creative methods to improve program implementation, reach and sustainability, suggesting a bi-directional relationship between these program characteristics.

Table 4 lists the overarching study themes and illustrative quotes that assisted in the interpretation of findings.

This is the first study, to this author’s knowledge, that applied CFIR to examine system-wide implementation factors of clinical FI screening initiatives within the context of healthcare settings and primary care. Empirically tested and theoretically derived CFIR concepts guided the development of a conceptual implementation model, while integrating program outcomes strengthened the interpretation of qualitative findings. The conceptual model in Fig. 3 may be tested and refined in follow-up studies to facilitate implementation and increase program reach, impact and sustainability.

In this early stage of formative research, one optimal combination of clinical screening and referral activities did not emerge as generalizable for testing on a larger scale, which is a necessary step in the translational research pipeline [ 40 ]. The U.S. healthcare system’s fragmented payer system, lack of universal coverage and disparities in cost and quality of healthcare may have contributed to this finding, and was reflective in this study when each program was operationalized in different ways to meet the unique challenges, needs and context of each health system and patient population.

Nevertheless, overarching themes that emerged across cases that maybe generalizable. Salient to this study were the CFIR concepts, program adaptability and trialability that made implementation feasible across both cases, while maintaining core screening and referral activities. This is consistent with the scalability and implementation framework literature that relies on assessing context, such as available human capital, technical resources, financial costs, and any other contextual factors that may not be replicable in a larger study, but that provide information about the authenticity and feasibility of delivering core intervention activities in clinical practice [ 26 , 40 , 41 ]. This finding is also reflective in and policy recommendations for SDOH screening practices that identify the flexibility of SDOH screening program activities to meet the health system context, including patient and staff needs [ 42 , 43 ].

Building on this concept, the proactive support of intervention modifications has been proposed in emerging health equity research as a way to address disparities in healthcare delivery, access, resources and outcomes in our most vulnerable populations [ 44 ]. It requires the documentation of intervention modifications, which enhance fit or effectiveness in a given context that can lead to improved engagement, acceptability and clinical outcomes [ 44 , 45 ]. Documentation of key adaptations can also facilitate more rigorous feasibility studies when researchers clarify the context of adaptations, such as the reasoning, timing, and process of modifications that facilitated implementation, scale-up, spread or sustainability, and should be considered in future clinical FI screening research that builds on this study [ 45 ].

Moreover, adaptability and trialability highlighted the significance of the CFIR cosmopolitanism concept in this study. Specifically, the interaction between the inner culture and community context drove program design and filled healthcare resource gaps. This finding reflects the current literature on the existences of clinical-community linkages to address FI through clinical screening and referral mechanisms [ 8 , 9 ]. It also points to a multi-sector response that has already demonstrated effective collaborations between primary care and community organizations in the control and management of communicable and chronic diseases by establishing a medical home that is patient and community centered [ 46 , 47 ].

Recommendations

Study findings resulted in the following recommendations for health systems: 1) Allow for adaptations with caution. Unique implementation contexts can foster implementation feasibility. Yet, considerations need to be made about how adaptations may negatively impact fidelity, reach and effectiveness. 2) Consider how the context can support intervention activities through clinician input about workflow, program responsibilities and time management. 3) Conduct asset mapping and outreach to potential community partners that have a strong presence in the community, aligned goals and objectives and resources that can be leveraged during program design and implementation. This recommendation raises its own challenges about whose responsibility within the health system it is to make community-wide connections and manage relationships, but is key for establishing a truly patient and community-centered medical home. 4) Consider non-traditional forms of staff support. In this study, allied health and medical students were motivated to work as interns in exchange for hands-on, experiential learning. Generally, students are subject to high turnover and may not always be the best solution to fill staffing shortages that require a long-term commitment. An alternative solution is to leverage the role and expertise of community health workers that are trusted sources of information for patients because they often live within the communities they serve.

Limitations

As a study instrument, the researcher was positioned alongside study participants during the process of information discovery during data collection and analysis. As such, this was a subjective process that may have been affected by the researcher’s own biases and experiences [ 48 ]. The researcher utilized source triangulation and member checks to negate the effect of these factors during data analysis and interpretation.

While this study incorporated the perspective of multiple implementation actors representative of the implementation context, the sample size may be considered small at first glance. What is important to note is that data saturation was achieved, and that qualitative research of this nature requires the deep exploration of the context to interpret findings in a meaningful way. The scope of the study may have been expanded to incorporate more programs and program staff if time and resources to complete this study had not been limited.

The study did not include patients’ perspectives or in vivo observations of screening and referral processes. Real-time data could have enhanced study findings, and patients’ perspectives could have provided insight about how screening and referral processes affected their clinical experience. The amount of time allotted for this study limited the scope of the study to the perspective of implementation actors only. Moreover, due to patient privacy laws, the study sites would not allow researchers to sit in during clinical visits. Future studies should consider patient interviews and immediate, post visit surveys to gauge a patient’s perspective about screening and referral processes.

Due to time restrictions, data that were collected at only one point in time and relied on the memory of each participant. Future studies should consider the collection of data from participants at multiple time points to capture the dynamic process of implementation and to further validate findings.

Lastly, this study is applicable only to the context of the U.S. healthcare system and characteristics of FI within the U.S. Nevertheless, a community-clinical integrated model may have the potential to address hunger in other countries.

Implications

This study makes significant contributions to the limited body of literature in the emerging field of clinical FI screening programs in primary care practice. In particular, the proposed conceptual model is a foundation for the development of theory-driven standard practices. Though formative in nature the model identifies areas of exploration that have not been considered in previous research, such as intervention adaptability, internal work culture and the community climate.

Study findings have implications for practice-based research. The exploration of external factors and creative uses of internal assets for program support should be considered due to the scarcity of funding for community-based interventions implemented in low-resource clinics. Future work should consider how these factors may enhance limited internal resources long-term. Community-engaged formative research with patients could help to tailor primary care focused initiatives to the realities of patient needs. Engaging the patient community could provide critical insights about stigma, privacy, trust and workflow processes from the patient’s perspective, as well as provide deeper understanding about the cyclical nature of household FI that may inform frequency of screening and can be used to advocate for additional health services. Study findings also have implications for ongoing policy work of universal social determinants of health screening practices supported by national healthcare experts.

The key take away from this study is that due to limited healthcare resources, primary care practices that serve low-income communities need to be supported in their ability to adapt program activities to their specific context. While high program fidelity and intended program outcomes may not have been achieved in this study, findings demonstrate how implementation feasibility can be achieved when community partnerships and an internal resources are leveraged for program adaptations and support. With this in mind, future research may continue to build on the proposed conceptual model, which is formative in nature and sets the stage for development of standard screening practices. As our healthcare system continues its transition to a value-based model of care, we need to consider how primary care focused FI screening initiatives can effectively connect patients to food resources. If we can reduce the inequitable access to affordable and healthy food, we may eventually see long-term improvements in the quality of life of our most vulnerable populations.

Abbreviations

Food Insecurity/Food Insecure

United States

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

Special Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program for Women’s Infants and Children

Electronic Health Records

Electronic Medical Records

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

Alliance for Health Equity

Services USD of AER. Food and Nutrition Assistance, Food Security in the U.S., Measurement [Internet]. Vol. 2017. 2016. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement/

Food Security and COVID-19 [Internet]. [cited 2021 May 25]. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/agriculture/brief/food-security-and-covid-19

Smith MD, Rabbitt MP. Coleman- Jensen a. who are the world’s food insecure? New evidence from the food and agriculture organization’s food insecurity experience scale. World Dev. 2017;93:402–12.

Article Google Scholar

U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective, 2019 | Commonwealth Fund [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 18]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019

Food insecurity is at the highest levels since the Great Depression because of the COVID-19 pandemic [Internet]. [cited 2021 May 11]. Available from: https://slate.com/technology/2020/11/food-insecurity-crisis-thanksgiving.html

Seligman KK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity and clinical measures of chronic disease. Abstract Presentation, SGIM, National Meeting, PA,. 2008.

Gundersen C, Engelhard EE, Crumbaugh AS, Seligman HK. Brief assessment of food insecurity accurately identifies highrisk US adults. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(08):1367–71.

Barnidge E, Stenmark S, Seligman H. Clinic-to-community models to address food insecurity. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(6):507–8.

Lundeen EA, Siegel KR, Calhoun H, Kim SA, Garcia SP, Hoeting NM, et al. Clinical-community partnerships to identify patients with food insecurity and address food needs. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14(E113).

Joshi K, Smith S, Bolen SD, Osborne A, Benko M, Trapl ES. Implementing a Produce Prescription Program for Hypertensive Patients in Safety Net Clinics. Health Promot Pract [Internet]. 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2020 May 24];20(1):94–104. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1524839917754090

Patel KG, Borno HT, Seligman HK. Food insecurity screening: A missing piece in cancer management. Vol. 125, Cancer. John Wiley and Sons Inc.; 2019. p. 3494–501.

Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304–10.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Cavanagh M, Jurkowski J, Bozlak C, Hastings J, Klein A. Veggie Rx: an outcome evaluation of a healthy food incentive programme. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(14):2636–41.

Nestle M. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): History, politics, and public health implications. Am J Public Health [Internet]. 2019 Dec 6 [cited 2020 May 28];109(12):1631–5. Available from: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305361

Trapl ES, Smith S, Joshi K, Osborne A, Matos AT, Bolen S. Dietary impact of produce prescriptions for patients with hypertension. Prev Chronic Dis 2018 1;15(11).

Gupta DM, Boland RJ Jr, Aron DC. The physician’s experience of changing clinical practice: a struggle to unlearn. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):22–8.

Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing Social Determinants of Health at Well Child Care Visits: A Cluster RCT. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2015;135(2):e296–304 1p. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=103794683&site=ehost-live

Barnidge E, LaBarge G, Krupsky K, Arthur J. Screening for food insecurity in pediatric clinical settings: opportunities and barriers. J Community Health. 2017;42(1):51–7.

Torres J, De Marchis E, Fichtenberg C, Gottlieb L. Identifying food insecurity in health care settings: a review of the evidence. San Francisco, CA: Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network; 2017.

Google Scholar

De Marchis EH, Torres JM, Benesch T, Fichtenberg C, Allen IE, Whitaker EM, et al. Interventions addressing food insecurity in health care settings: A systematic review. Vol. 17, Annals of Family Medicine. Annals of Family Medicine, Inc; 2019. p. 436–47.

Downer S, Berkowitz SA, Berkowitz SA, Harlan TS, Olstad DL, Mozaffarian D. Food is medicine: Actions to integrate food and nutrition into healthcare [Internet]. Vol. 369, The BMJ. BMJ Publishing Group; 2020 [cited 2021 May 25]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2482http://www.bmj.com/

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury MJ, Kaplan RM, Hunter C. National Institutes of Health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. Am J Public Heal [Internet]. 2012;102(7):1274–81. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300755 .

Damschroder LJ. Clarity out of chaos: use of theory in implementation research. Psychiatry Res. 2020;283:112461.

Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Vol. 11, Implementation Science. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2016.

Li SA, Jeffs L, Barwick M, Stevens B. Organizational contextual features that influence the implementation of evidence-based practices across healthcare settings: a systematic integrative review. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):1–19.

NOPREN. Food Insecurity Screening Algorithm for Pediatric Patients [Internet]. Vol. 2017. 2017. Available from: http://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/food-insecurity-screening-algorithm-pediatric-patients.pdf

Stake RE. The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995.

Yin KR. Case study research and applications: design and methods. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.; 2018.

Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.; 2018. 100, 148 p.

Gold R, Bunce A, Cottrell E, Marino M, Middendorf M, Cowburn S, et al. Study protocol: A pragmatic, stepped-wedge trial of tailored support for implementing social determinants of health documentation/action in community health centers, with realist evaluation. Implement Sci [Internet]. 2019 Jan 28 [cited 2021 Feb 26];14(1):1–17. Available from: doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0855-9 .

Safaeinili N, Brown-Johnson C, Shaw JG, Mahoney M, Winget M. CFIR simplified: Pragmatic application of and adaptations to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) for evaluation of a patient-centered care transformation within a learning health system. Learn Heal Syst [Internet]. n/a(n/a):e10201. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/lrh2.10201

Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health Care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001;79(2):281–315.

Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:29–45.

Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2015.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol [Internet]. 2013;13:117. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24047204 .

Haynes A, Brennan S, Redman S, Williamson A, Gallego G, Butow P. Figuring out fidelity: A worked example of the methods used to identify, critique and revise the essential elements of a contextualised intervention in health policy agencies. Implement Sci [Internet]. 2016 Feb 24 [cited 2021 Apr 1];11(1):23. Available from: http://www.implementationscience.com/content/11/1/23

Community Needs Assessment Central Region CHNA. Chicago, IL: Illinois Public Health Institute; 2016.

Stenmark SH, Steiner JF, Marpadga S, Debor M, Underhill K, Seligman H. Lessons Learned from Implementation of the Food Insecurity Screening and Referral Program at Kaiser Permanente Colorado. Perm J [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2021 May 25];22:18–093. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30296400/

Beets MW, Weaver RG, Ioannidis JPA, Geraci M, Brazendale K, Decker L, et al. Identification and evaluation of risk of generalizability biases in pilot versus efficacy/effectiveness trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis [Internet]. Vol. 17, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. BioMed Central Ltd.; 2020 [cited 2021 May 28]. p. 1–20. Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-020-0918-y

Damschroder J. L, Aron C. D, Keith E. R, Kirsh R. S, Alexander A. J, Lowery C. J. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science.

Byhoff E, Freund KM, Garg A. Accelerating the Implementation of Social Determinants of Health Interventions in Internal Medicine. J Gen Intern Med [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2021 Jun 16];33(2):223–8. Available from: www.who.int/social_determinants/en/ ,

De Marchis EH, Hessler D, Fichtenberg C, Fleegler EW, Huebschmann AG, Clark CR, et al. Assessment of social risk factors and interest in receiving health care-based social assistance among adult patients and adult caregivers of pediatric patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;1:3(10).

Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ. Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2020 Mar 12 [cited 2020 Apr 21];20(1):190. Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-020-4975-3

Stirman SW, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2019;6:14(1).

Martin-Misener R, Valaitis R, Wong ST, Macdonald M, Meagher-Stewart D, Kaczorowski J, et al. A scoping literature review of collaboration between primary care and public health. Prim Heal Care Res Dev [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2021 May 11];13(4):327–46. Available from: http://strengthenphc.mcmaster.cahttps//www.cambridge.org/core/terms . 10.1017/S1463423611000491, Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core

Franz BA, Murphy JW. The Patient-Centered Medical Home as a Community-based Strategy. Perm J [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2021 Jun 1];21:17. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC5528840/.

Stake RE. Multiple case study analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study participants for taking time out of their busy schedules to contribute to this study. We would like to thank Kathy Chan and Lena Hatchett for their assistance with participant recruitment.

Availability of data

Datasets from this study are not publicly available due to institutional review board regulations, but selective, di-identified, aggregated data may be made available upon reasonable request. Please contact corresponding author Sabira Taher at [email protected] .

This study was funded by an internal dissertation research award funded by the researcher’s academic institution. The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Preventive Medicine, Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, 680 N Lake Shore Drive Suite 1400, Chicago, IL, 60611, USA

Sabira Taher & C. Fagen Michael

Department of Community Health Sciences, School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1603 W. Taylor Street, Chicago, IL, 60612, USA

Naoko Muramatsu & Nadine Peacock

Division of Nutritional Sciences, College of Human Ecology, Cornell University, Martha Van Rensselaer Hall, Ithaca, NY, 14853, USA

Angela Odoms-Young

Department of Family Medicine, Loyola Stritch School of Medicine, 2160 S 1st Ave, Maywood, IL, 60153, USA

K. Suh Courtney

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ST led the conception and design of the study, development of study instruments, conducted interviews, data analysis, data interpretation and led manuscript writing. NM assisted with critical revisions of the manuscript for content. AOY assisted with developing the study design, data interpretation and critical revisions of the manuscript. MF, NP, and CS assisted with data interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sabira Taher .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate.

All procedures in this study involving human subjects were in accordance with ethical standards of the University of Illinois at Chicago Office for the Protection of Research Subjects Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study and the verbal consent process were approved for a claim of exemption (Protocol # 2019–0610) from the University of Illinois at Chicago Office for the Protection of Research Subjects Institutional Review Board on August 30, 2019. Informed, verbal consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. Study findings were reported using the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., additional file 2., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Taher, S., Muramatsu, N., Odoms-Young, A. et al. An embedded multiple case study: using CFIR to map clinical food security screening constructs for the development of primary care practice guidelines. BMC Public Health 22 , 97 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12407-y

Download citation

Received : 05 August 2021

Accepted : 10 December 2021

Published : 14 January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12407-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Food security screening

- Implementation

- Dissemination

- Primary care practice

- Semi-structured interviews

- Produce prescription programs

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Improving the Evaluation of Scholarly Work pp 65–80 Cite as

Case Research and Theory in Service Research

- Cristina Mele 4 ,

- Marialuisa Marzullo 4 ,

- Montserrat Díaz-Méndez 5 &

- Evert Gummesson 6

- First Online: 09 November 2022

135 Accesses

1 Citations

Research methodology is a set of procedures that scholars follow to address their studies and ensure valid and reliable results. Choosing a suitable methodological approach is essential for the research process and represents one of the most challenging decisions for scholars. Case studies research assumes a key role in the debate between qualitative and quantitative methods. A manageable step forward to addressing complexity is offered by the narrative case study that interprets and makes sense of stories told by individuals. A further recent extension of case study research coming from the need to include two theoretical approaches that face complexity more systematically and structured: network theory and systems theory, led to the definition of case theory. Case theory offers higher validity and relevance by focusing on the outcome instead of details of the research process and techniques to augment reliability and rigor. Due to its characteristics, case theory is suitable to the service research and could contribute to new theoretical development.

- Case theory

- Narrative case

- Qualitative method

- Interpretive research

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Alam, M. K. (2020). A systematic qualitative case study: Questions, data collection, NVivo analysis and saturation. Qualitative Research in Organisations and Management: An International Journal, 16 (1), 15–31.

Google Scholar

Andersen, P. H., Dubois, A., & Lind, F. (2018). Process validation: Coping with three dilemmas in process-based single-case research. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing., 39 (1), 49–55.

Article Google Scholar

Antwi, S. K., & Hamza, K. (2015). Qualitative and quantitative research paradigms in business research: A philosophical reflection. European Journal of Business and Management, 7 (3), 217–225.

Azorín, J. M., & Cameron, R. (2010). The application of mixed methods in organisational research: A literature review. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 8 (2), 95–105.

Benasso, S., Palumbo, M., & Pandolfini, V. (2019). Narrating cases: A storytelling approach to case study analysis in the field of lifelong learning policies. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 11 (2), 21–35.

Borghini, S., Carù, A., & Cova, B. (2010). Representing BtoB reality in case study research: Challenges and new opportunities. Industrial Marketing Management, 39 (1), 16–24.

Botturi, D., Curcio Rubertini, B., Desmarteau, R. H., & Lavalle, T. (2015). Investing in social capital in Emilia-Romagna region of Italy as a strategy for making public health work. In C. D. Johnson (Ed.), Social capital: Global perspectives, management strategies and effectiveness (pp. 197–219). Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Bucic, T., Robinson, L., & Ramburuth, P. (2010). Effects of leadership style on team learning. Journal of Workplace Learning., 22 (4), 228–248.

Coffey, A., & Atkinson, P. (1996). Making sense of qualitative data: Complementary research strategies . Sage Publications, Inc.

Czarniawska, B. (2004). Narratives in social science research. Introducing qualitative methods . Sage Publications.

Denzin, N. K. (1989). Interpretive biography . Sage.

Dilthey, W. (1883). Introduction to the human sciences. In H. P. Richman (Ed.), W. Dilthey: Selected writings (pp. 157–263). London: Cambridge University Press

Dubois, A., & Araujo, L. (2004). Research methods in industrial marketing studies. In H. Håkansson (Ed.), Rethinking marketing: Developing a new understanding of markets (pp. 207–227). Wiley.

Durkheim, E. (1960). Montesquieu’s contribution to the rise of social science. In Montesquieu and Rousseau: Forerunners of sociology . Translated by R. Man- heim with a foreword by H. Peyre (pp. 1–64). University of Michigan Press.

Edmondson, A. C., & McManus, S. E. (2007). Methodological fit in management field research. Academy of Management Review, 32 (4), 1246–1264.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50 (1), 25–32.

Fischer, M. (2015). Fit for the future? A new approach in the debate about what makes healthcare systems really sustainable. Sustainability, 7 , 294–312.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12 (2), 219–245.

George, A. L., & Bennett, A. (2005). Case studies and theory development in the social sciences . MA, MIT Press.

Gillham, B. (2000). Case study research methods . Bloomsbury Publishing.

Gomm, R., Hammersley, M., & Foster, P. (Eds.). (2000). Case study method: Key issues, key texts . Sage.

Goulding, C. (2002). Grounded theory: A practical guide for management, business and market researchers . Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Gray, D. E. (2021). Doing research in the real world . Sage.

Gummesson, E. (2002). Relationship marketing and a new economy: It’s time for de‐programming. Journal of services marketing, 16 (7), 585–589.

Gummesson, E. (2007). Case study research and network theory: Birds of a feather. Qualitative Research in Organisations and Management, 2 (3), 226–248.

Gummesson, E. (2014). Service research methodology: From case study research to case theory. Revista Ibero Americana De Estratégia, 13 (4), 08–17.

Gummesson, E. (2015). Innovative case study research in business and management . Sage.

Gummesson, E. (2017). Case theory in business and management: Reinventing case study research . Sage.

Gummesson, E., Mele, C., & Polese, F. (2019). Complexity and viability in service ecosystems. Marketing Theory, 19 (1), 3–7.

Halkier, B. (2011). Methodological practicalities in analytical generalisation. Qualitative Inquiry, 17 (9), 787–797.

Harrison, R. L., III. (2013). Using mixed methods designs in the Journal of Business Research, 1990–2010. Journal of Business Research, 66 (11), 2153–2162.

Helkkula, A. (2010). Service experience in an innovation context . Hanken School of Economics

Helkkula, A., Kelleher, C., & Pihlström, M. (2012). Characterising value as an experience: Implications for service researchers and managers. Journal of Service Research, 15 (1), 59–75.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Ireland, R. D. (1994). A mid-range theory of the interactive effects of international and product diversification on innovation and performance. Journal of Management, 20 (2), 297–326.

Johnston, W. J., Leach, M. P., & Liu, A. H. (1999). Theory testing using case studies in business-to-business research. Industrial Marketing Management, 28 (3), 201–213.

King, G., R. Keohane and S. Verba (1994) Designing Social Enquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

Knights, D., & McCabe, D. (1997). ‘How would you measure something like that?’: Quality in a retail bank. Journal of Management Studies, 34 (3), 371–388.

Lee, B., Collier, P. M., & Cullen, J. (2007). Reflections on the use of case studies in the accounting, management and organisational disciplines. Qualitative Research in Organisations and Management: An International Journal., 2 (3), 169–178.

Mathisen, L. I. N. E., & Chen, J. S. (2014). Storytelling in a co-creation perspective. In J. S. Chen, M. Uysal, & N. K. Prebensen (Eds.), Co-creation of experience value—A tourist behavior approach . CAB International (in Press).

Modell, S. (2010). Bridging the paradigm divide in management accounting research: The role of mixed methods approaches. Management Accounting Research, 21 (2), 124–129.

Närvänen, E., Gummesson, E., & Kuusela, H. (2014). The collective consumption network. Managing Service Quality, 24 (6), 545–564.

Neuman, S. B., & Dickinson, D. K. (Eds.). (2003). Handbook of early literacy research (Vol. 1, pp. 11–29). Guilford Press.

Nie, Y. (2017). Combining narrative analysis, grounded theory and qualitative data analysis software to develop a case study research. Journal of Management Research, 9 (2), 53–70.

Parlett, M., Hamilton, D. (1976) ‘Evaluation as illumination: A new approach to the study of innovative programs’. In D. A. Tawney (Ed.), Curriculum evaluation today: Trends and implications . Macmillan Education.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (p. 532). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Perry, C. (1998). Processes of a case study methodology for postgraduate research in marketing. European Journal of Marketing., 32 (9/10), 785–802.

Piekkari, R., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Welch, C. (2010). ‘Good’ case research in industrial marketing: Insights from research practice. Industrial Marketing Management, 39 (1), 109–117.

Pike, K. L. (1967). Etic and emic standpoints for the description of behavior. In D. C. Hildum (Ed.), Language and thought: An enduring problem in psychology (pp. 32–39). Van Nostrand.

Reis, H. T., & Judd, C. M. (Eds.). (2000). Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology . Cambridge University Press.

Ridder, H. G. (2017). The theory contribution of case study research designs. Business Research, 10 (2), 281–305.

Riessman, C. K. (1993). Narrative analysis (Vol. 30). Sage.

Rossman, G. B., & Wilson, B. L. (1994). Numbers and words revisited: Being “shamelessly eclectic.” Quality and Quantity, 28 (3), 315–327.

Roller, M. R., & Lavrakas, P. J. (2015). Applied qualitative research design: A total quality framework approach . Guilford Publications.

Russo Spena, T., & Mele, C. (2019). Practising innovation in the healthcare ecosystem: The agency of third-party actors. The Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 35 (3), 390–403.

Saunders, M. N., & Bezzina, F. (2015). Reflections on conceptions of research methodology among management academics. European Management Journal, 33 (5), 297–304.

Siltaloppi, J., & Vargo, S. L. (2017). Triads: A review and analytical framework. Marketing Theory, 17 (4), 395–414.

Simons, H. (2014). Case study research: In-depth understanding in context. The Oxford handbook of qualitative research (pp. 455–470).

Sommer Harrits, G. (2011). More than method?: A discussion of paradigm differences within mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 5 (2), 150–166.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research . Sage Publications, Inc.

Stake, R. (1998). Case studies. In N. Denzin, Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies of qualitative inquiry . Sage.

Stake, R. E. (2000). The case study and generalizability. In R. Gomm, M. Hammersley, and P. Foster (Eds.), Case study method. Key issues, key texts (pp. 19–26). Sage Publications.

Stake, R. E. (2013). Multiple case study analysis . Guilford press.

Taleb, N. N. (2007). Black swans and the domains of statistics. The American Statistician, 61 (3), 198–200.

Thyer, B. A. (2001). What is the role of theory in research on social work practice? Journal of Social Work Education, 37 (1), 9–25.

Tight, M. (2010). The curious case of case study: A viewpoint. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 13 (4), 329–339.

Tsoukas, H., & Hatch, M. J. (2001). Complex thinking, complex practice: The case for a narrative approach to organisational complexity. Human Relations, 54 (8), 979–1013.

Turner, J. H. (2001). The origins of positivism: The contributions of Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer. In Handbook of social theory (pp. 30–42). Sage Publications.

Weber, M. (1904). Die" Objektivität" sozialwissenschaftlicher und sozialpolitischer Erkenntnis. Archiv Für Sozialwissenschaft Und Sozialpolitik, 19 (1), 22–87.

Webster, L., & Mertova, P. (2007). Using narrative inquiry as a research method: An introduction to using critical event narrative analysis in research on learning and teaching . Routledge.

Welch, C., Piekkari, R., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Paavilainen-Ma¨ntyma¨ki, E. (2011). Theorising from case studies: Towards a pluralist future for international business research. Journal of International Business Studie, 42 , 740–762.

Westerman, M. A. (2011). Defenses in interpersonal interaction: Using a theory-building case study to develop and validate the theory of interpersonal defense. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 7 (4), 449–476.

Woodside, A. G., & Wilson, E. J. (2003). Case study research methods for theory building. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 18 (6/7), 493–508.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Yin, R. K. (Ed.). (2004). The case study anthology . Thousand Oaks.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research design and methods (5th ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy

Cristina Mele & Marialuisa Marzullo

University of Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain

Montserrat Díaz-Méndez

University of Stockholm, Stockholm, Sweden

Evert Gummesson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cristina Mele .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Stockholm Business School, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain

University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

Michael Saren

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Mele, C., Marzullo, M., Díaz-Méndez, M., Gummesson, E. (2022). Case Research and Theory in Service Research. In: Gummesson, E., Díaz-Méndez, M., Saren, M. (eds) Improving the Evaluation of Scholarly Work. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17662-3_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17662-3_5

Published : 09 November 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-17661-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-17662-3

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Section 2: Home

- Developing the Quantitative Research Design

- Qualitative Descriptive Design

- Design and Development Research (DDR) For Instructional Design

- Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Research

- Action Research Resource