Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Study Protocol

Assessing the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, shift to online learning, and social media use on the mental health of college students in the Philippines: A mixed-method study protocol

Roles Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft

Affiliation College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Roles Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Clinical Epidemiology, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines, Institute of Clinical Epidemiology, National Institutes of Health, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Roles Methodology

Affiliation Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Leonard Thomas S. Lim,

- Zypher Jude G. Regencia,

- J. Rem C. Dela Cruz,

- Frances Dominique V. Ho,

- Marcela S. Rodolfo,

- Josefina Ly-Uson,

- Emmanuel S. Baja

- Published: May 3, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267555

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Introduction

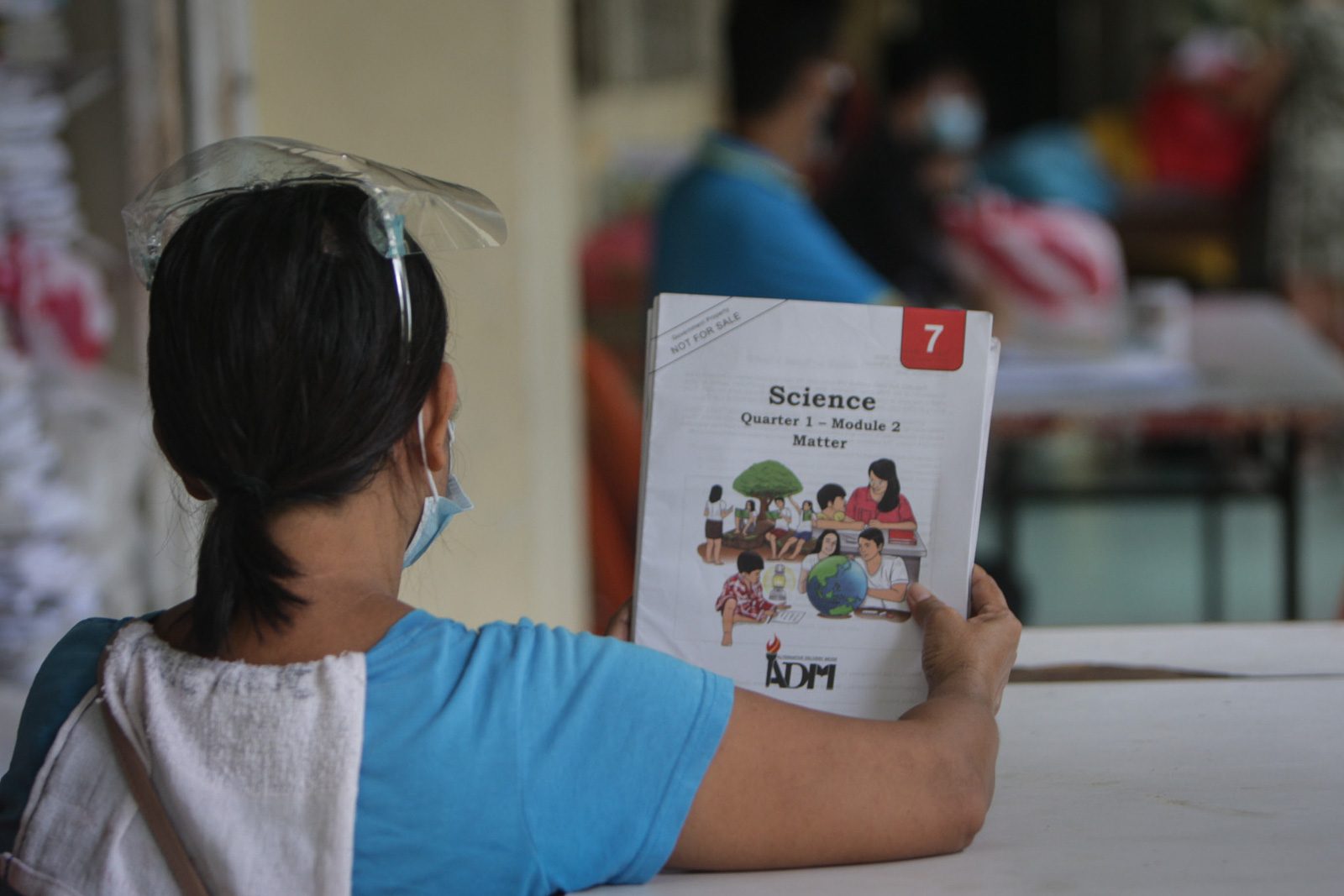

The COVID-19 pandemic declared by the WHO has affected many countries rendering everyday lives halted. In the Philippines, the lockdown quarantine protocols have shifted the traditional college classes to online. The abrupt transition to online classes may bring psychological effects to college students due to continuous isolation and lack of interaction with fellow students and teachers. Our study aims to assess Filipino college students’ mental health status and to estimate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift to online learning, and social media use on mental health. In addition, facilitators or stressors that modified the mental health status of the college students during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning will be investigated.

Methods and analysis

Mixed-method study design will be used, which will involve: (1) an online survey to 2,100 college students across the Philippines; and (2) randomly selected 20–40 key informant interviews (KIIs). Online self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) including Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) and Brief-COPE will be used. Moreover, socio-demographic factors, social media usage, shift to online learning factors, family history of mental health and COVID-19, and other factors that could affect mental health will also be included in the SAQ. KIIs will explore factors affecting the student’s mental health, behaviors, coping mechanism, current stressors, and other emotional reactions to these stressors. Associations between mental health outcomes and possible risk factors will be estimated using generalized linear models, while a thematic approach will be made for the findings from the KIIs. Results of the study will then be triangulated and summarized.

Ethics and dissemination

Our study has been approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB 2021-099-01). The results will be actively disseminated through conference presentations, peer-reviewed journals, social media, print and broadcast media, and various stakeholder activities.

Citation: Lim LTS, Regencia ZJG, Dela Cruz JRC, Ho FDV, Rodolfo MS, Ly-Uson J, et al. (2022) Assessing the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, shift to online learning, and social media use on the mental health of college students in the Philippines: A mixed-method study protocol. PLoS ONE 17(5): e0267555. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267555

Editor: Elisa Panada, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: June 9, 2021; Accepted: April 11, 2022; Published: May 3, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Lim et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This project is being supported by the American Red Cross through the Philippine Red Cross and Red Cross Youth. The funder will not have a role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak as a global pandemic, and the Philippines is one of the 213 countries affected by the disease [ 1 ]. To reduce the virus’s transmission, the President imposed an enhanced community quarantine in Luzon, the country’s northern and most populous island, on March 16, 2020. This lockdown manifested as curfews, checkpoints, travel restrictions, and suspension of business and school activities [ 2 ]. However, as the virus is yet to be curbed, varying quarantine restrictions are implemented across the country. In addition, schools have shifted to online learning, despite financial and psychological concerns [ 3 ].

Previous outbreaks such as the swine flu crisis adversely influenced the well-being of affected populations, causing them to develop emotional problems and raising the importance of integrating mental health into medical preparedness for similar disasters [ 4 ]. In one study conducted on university students during the swine flu pandemic in 2009, 45% were worried about personally or a family member contracting swine flu, while 10.7% were panicking, feeling depressed, or emotionally disturbed. This study suggests that preventive measures to alleviate distress through health education and promotion are warranted [ 5 ].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers worldwide have been churning out studies on its psychological effects on different populations [ 6 – 9 ]. The indirect effects of COVID-19, such as quarantine measures, the infection of family and friends, and the death of loved ones, could worsen the overall mental wellbeing of individuals [ 6 ]. Studies from 2020 to 2021 link the pandemic to emotional disturbances among those in quarantine, even going as far as giving vulnerable populations the inclination to commit suicide [ 7 , 8 ], persistent effect on mood and wellness [ 9 ], and depression and anxiety [ 10 ].

In the Philippines, a survey of 1,879 respondents measuring the psychological effects of COVID-19 during its early phase in 2020 was released. Results showed that one-fourth of respondents reported moderate-to-severe anxiety, while one-sixth reported moderate-to-severe depression [ 11 ]. In addition, other local studies in 2020 examined the mental health of frontline workers such as nurses and physicians—placing emphasis on the importance of psychological support in minimizing anxiety [ 12 , 13 ].

Since the first wave of the pandemic in 2020, risk factors that could affect specific populations’ psychological well-being have been studied [ 14 , 15 ]. A cohort study on 1,773 COVID-19 hospitalized patients in 2021 found that survivors were mainly troubled with fatigue, muscle weakness, sleep difficulties, and depression or anxiety [ 16 ]. Their results usually associate the crisis with fear, anxiety, depression, reduced sleep quality, and distress among the general population.

Moreover, the pandemic also exacerbated the condition of people with pre-existing psychiatric disorders, especially patients that live in high COVID-19 prevalence areas [ 17 ]. People suffering from mood and substance use disorders that have been infected with COVID-19 showed higher suicide risks [ 7 , 18 ]. Furthermore, a study in 2020 cited the following factors contributing to increased suicide risk: social isolation, fear of contagion, anxiety, uncertainty, chronic stress, and economic difficulties [ 19 ].

Globally, multiple studies have shown that mental health disorders among university student populations are prevalent [ 13 , 20 – 22 ]. In a 2007 survey of 2,843 undergraduate and graduate students at a large midwestern public university in the United States, the estimated prevalence of any depressive or anxiety disorder was 15.6% and 13.0% for undergraduate and graduate students, respectively [ 20 ]. Meanwhile, in a 2013 study of 506 students from 4 public universities in Malaysia, 27.5% and 9.7% had moderate and severe or extremely severe depression, respectively; 34% and 29% had moderate and severe or extremely severe anxiety, respectively [ 21 ]. In China, a 2016 meta-analysis aiming to establish the national prevalence of depression among university students analyzed 39 studies from 1995 to 2015; the meta-analysis found that the overall prevalence of depression was 23.8% across all studies that included 32,694 Chinese university students [ 23 ].

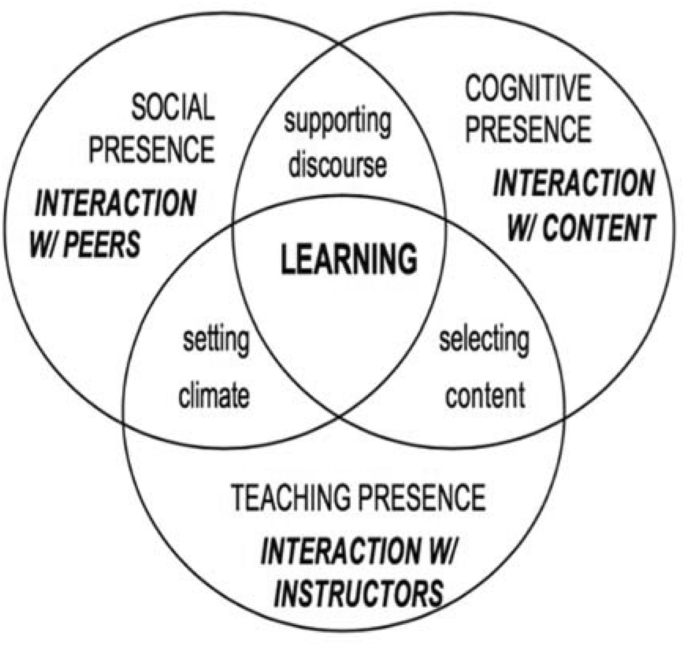

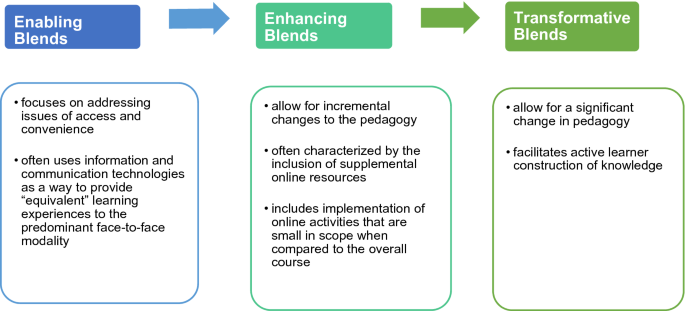

A college student’s mental status may be significantly affected by the successful fulfillment of a student’s role. A 2013 study found that acceptable teaching methods can enhance students’ satisfaction and academic performance, both linked to their mental health [ 24 ]. However, online learning poses multiple challenges to these methods [ 3 ]. Furthermore, a 2020 study found that students’ mental status is affected by their social support systems, which, in turn, may be jeopardized by the COVID-19 pandemic and the physical limitations it has imposed. Support accessible to a student through social ties to other individuals, groups, and the greater community is a form of social support; university students may draw social support from family, friends, classmates, teachers, and a significant other [ 25 , 26 ]. Among individuals undergoing social isolation and distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, social support has been found to be inversely related to depression, anxiety, irritability, sleep quality, and loneliness, with higher levels of social support reducing the risk of depression and improving sleep quality [ 27 ]. Lastly, it has been shown in a 2020 study that social support builds resilience, a protective factor against depression, anxiety, and stress [ 28 ]. Therefore, given the protective effects of social support on psychological health, a supportive environment should be maintained in the classroom. Online learning must be perceived as an inclusive community and a safe space for peer-to-peer interactions [ 29 ]. This is echoed in another study in 2019 on depressed students who narrated their need to see themselves reflected on others [ 30 ]. Whether or not online learning currently implemented has successfully transitioned remains to be seen.

The effect of social media on students’ mental health has been a topic of interest even before the pandemic [ 31 , 32 ]. A systematic review published in 2020 found that social media use is responsible for aggravating mental health problems and that prominent risk factors for depression and anxiety include time spent, activity, and addiction to social media [ 31 ]. Another systematic review published in 2016 argues that the nature of online social networking use may be more important in influencing the symptoms of depression than the duration or frequency of the engagement—suggesting that social rumination and comparison are likely to be candidate mediators in the relationship between depression and social media [ 33 ]. However, their findings also suggest that the relationship between depression and online social networking is complex and necessitates further research to determine the impact of moderators and mediators that underly the positive and negative impact of online social networking on wellbeing [ 33 ].

Despite existing studies already painting a picture of the psychological effects of COVID-19 in the Philippines, to our knowledge, there are still no local studies contextualized to college students living in different regions of the country. Therefore, it is crucial to elicit the reasons and risk factors for depression, stress, and anxiety and determine the potential impact that online learning and social media use may have on the mental health of the said population. In turn, the findings would allow the creation of more context-specific and regionalized interventions that can promote mental wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

The study’s general objective is to assess the mental health status of college students and determine the different factors that influenced them during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, it aims:

- To describe the study population’s characteristics, categorized by their mental health status, which includes depression, anxiety, and stress.

- To determine the prevalence and risk factors of depression, anxiety, and stress among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning.

- To estimate the effect of social media use on depression, anxiety, stress, and coping strategies towards stress among college students and examine whether participant characteristics modified these associations.

- To estimate the effect of online learning shift on depression, anxiety, stress, and coping strategies towards stress among college students and examine whether participant characteristics modified these associations.

- To determine the facilitators or stressors among college students that modified their mental health status during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning.

Study design

A mixed-method study design will be used to address the study’s objectives, which will include Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and an online survey. During the quarantine period of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines from April to November 2021, the study shall occur with the population amid community quarantine and an abrupt transition to online classes. Since this is the Philippines’ first study that will look at the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning, the online survey will be utilized for the quantitative part of the study design. For the qualitative component of the study design, KIIs will determine facilitators or stressors among college students that modified their mental health status during the quarantine period.

Study population

The Red Cross Youth (RCY), one of the Philippine Red Cross’s significant services, is a network of youth volunteers that spans the entire country, having active members in Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. The group is clustered into different age ranges, with the College Red Cross Youth (18–25 years old) being the study’s population of interest. The RCY has over 26,060 students spread across 20 chapters located all over the country’s three major island groups. The RCY is heterogeneously composed, with some members classified as college students and some as out-of-school youth. Given their nationwide scope, disseminating information from the national to the local level is already in place; this is done primarily through email, social media platforms, and text blasts. The research team will leverage these platforms to distribute the online survey questionnaire.

In addition, the online survey will also be open to non-members of the RCY. It will be disseminated through social media and engagements with different university administrators in the country. Stratified random sampling will be done for the KIIs. The KII participants will be equally coming from the country’s four (4) primary areas: 5–10 each from the national capital region (NCR), Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao, including members and non-members of the RCY.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the online survey will include those who are 18–25 years old, currently enrolled in a university, can provide consent for the study, and are proficient in English or Filipino. The exclusion criteria will consist of those enrolled in graduate-level programs (e.g., MD, JD, Master’s, Doctorate), out-of-school youth, and those whose current curricula involve going on duty (e.g., MDs, nursing students, allied medical professions, etc.). The inclusion criteria for the KIIs will include online survey participants who are 18–25 years old, can provide consent for the study, are proficient in English or Filipino, and have access to the internet.

Sample size

A continuity correction method developed by Fleiss et al. (2013) was used to calculate the sample size needed [ 34 ]. For a two-sided confidence level of 95%, with 80% power and the least extreme odds ratio to be detected at 1.4, the computed sample size was 1890. With an adjustment for an estimated response rate of 90%, the total sample size needed for the study was 2,100. To achieve saturation for the qualitative part of the study, 20 to 40 participants will be randomly sampled for the KIIs using the respondents who participated in the online survey [ 35 ].

Study procedure

Self-administered questionnaire..

The study will involve creating, testing, and distributing a self-administered questionnaire (SAQ). All eligible study participants will answer the SAQ on socio-demographic factors such as age, sex, gender, sexual orientation, residence, household income, socioeconomic status, smoking status, family history of mental health, and COVID-19 sickness of immediate family members or friends. The two validated survey tools, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) and Brief-COPE, will be used for the mental health outcome assessment [ 36 – 39 ]. The DASS-21 will measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress [ 40 ], while the Brief-COPE will measure the students’ coping strategies [ 41 ].

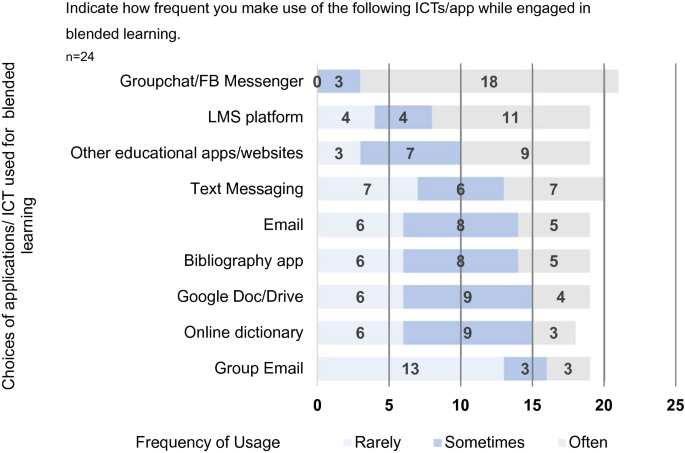

For the exposure assessment of the students to social media and shift to online learning, the total time spent on social media (TSSM) per day will be ascertained by querying the participants to provide an estimated time spent daily on social media during and after their online classes. In addition, students will be asked to report their use of the eight commonly used social media sites identified at the start of the study. These sites include Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, Pinterest, TikTok, YouTube, and social messaging sites Viber/WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger with response choices coded as "(1) never," "(2) less often," "(3) every few weeks," "(4) a few times a week," and “(5) daily” [ 42 – 44 ]. Furthermore, a global frequency score will be calculated by adding the response scores from the eight social media sites. The global frequency score will be used as an additional exposure marker of students to social media [ 45 ]. The shift to online learning will be assessed using questions that will determine the participants’ satisfaction with online learning. This assessment is comprised of 8 items in which participants will be asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree.’

The online survey will be virtually distributed in English using the Qualtrics XM™ platform. Informed consent detailing the purpose, risks, benefits, methods, psychological referrals, and other ethical considerations will be included before the participants are allowed to answer the survey. Before administering the online survey, the SAQ shall undergo pilot testing among twenty (20) college students not involved with the study. It aims to measure total test-taking time, respondent satisfaction, and understandability of questions. The survey shall be edited according to the pilot test participant’s responses. Moreover, according to the Philippines’ Data Privacy Act, all the answers will be accessible and used only for research purposes.

Key informant interviews.

The research team shall develop the KII concept note, focusing on the extraneous factors affecting the student’s mental health, behaviors, and coping mechanism. Some salient topics will include current stressors (e.g., personal, academic, social), emotional reactions to these stressors, and how they wish to receive support in response to these stressors. The KII will be facilitated by a certified psychologist/psychiatrist/social scientist and research assistants using various online video conferencing software such as Google Meet, Skype, or Zoom. All the KIIs will be recorded and transcribed for analysis. Furthermore, there will be a debriefing session post-KII to address the psychological needs of the participants. Fig 1 presents the diagrammatic flowchart of the study.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267555.g001

Data analyses

Quantitative data..

Descriptive statistics will be calculated, including the prevalence of mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, stress, and coping strategies. In addition, correlation coefficients will be estimated to assess the relations among the different mental health outcomes, covariates, and possible risk factors.

Several study characteristics as effect modifiers will also be assessed, including sex, gender, sexual orientation, family income, smoking status, family history of mental health, and Covid-19. We will include interaction terms between the dichotomized modifier variable and markers of social media use (total TSSM and global frequency score) and shift to online learning in the models. The significance of the interaction terms will be evaluated using the likelihood ratio test. All the regression analyses will be done in R ( http://www.r-project.org ). P values ≤ 0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Qualitative data.

After transcribing the interviews, the data transcripts will be analyzed using NVivo 1.4.1 software [ 50 ] by three research team members independently using the inductive logic approach in thematic analysis: familiarizing with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing the themes, defining and naming the themes, and producing the report [ 51 ]. Data familiarization will consist of reading and re-reading the data while noting initial ideas. Additionally, coding interesting features of the data will follow systematically across the entire dataset while collating data relevant to each code. Moreover, the open coding of the data will be performed to describe the data into concepts and themes, which will be further categorized to identify distinct concepts and themes [ 52 ].

The three researchers will discuss the results of their thematic analyses. They will compare and contrast the three analyses in order to come up with a thematic map. The final thematic map of the analysis will be generated after checking if the identified themes work in relation to the extracts and the entire dataset. In addition, the selection of clear, persuasive extract examples that will connect the analysis to the research question and literature will be reviewed before producing a scholarly report of the analysis. Additionally, the themes and sub-themes generated will be assessed and discussed in relevance to the study’s objectives. Furthermore, the gathering and analyzing of the data will continue until saturation is reached. Finally, pseudonyms will be used to present quotes from qualitative data.

Data triangulation.

Data triangulation using the two different data sources will be conducted to examine the various aspects of the research and will be compared for convergence. This part of the analysis will require listing all the relevant topics or findings from each component of the study and considering where each method’s results converge, offer complementary information on the same issue, or appear to contradict each other. It is crucial to explicitly look for disagreements between findings from different data collection methods because exploration of any apparent inter-method discrepancy may lead to a better understanding of the research question [ 53 , 54 ].

Data management plan.

The Project Leader will be responsible for overall quality assurance, with research associates and assistants undertaking specific activities to ensure quality control. Quality will be assured through routine monitoring by the Project Leader and periodic cross-checks against the protocols by the research assistants. Transcribed KIIs and the online survey questionnaire will be used for recording data for each participant in the study. The project leader will be responsible for ensuring the accuracy, completeness, legibility, and timeliness of the data captured in all the forms. Data captured from the online survey or KIIs should be consistent, clarified, and corrected. Each participant will have complete source documentation of records. Study staff will prepare appropriate source documents and make them available to the Project Leader upon request for review. In addition, study staff will extract all data collected in the KII notes or survey forms. These data will be secured and kept in a place accessible to the Project Leader. Data entry and cleaning will be conducted, and final data cleaning, data freezing, and data analysis will be performed. Key informant interviews will always involve two researchers. Where appropriate, quality control for the qualitative data collection will be assured through refresher KII training during research design workshops. The Project Leader will check through each transcript for consistency with agreed standards. Where translations are undertaken, the quality will be assured by one other researcher fluent in that language checking against the original recording or notes.

Ethics approval.

The study shall abide by the Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). It will be conducted along with the Guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP), E6 (R2), and other ICH-GCP 6 (as amended); National Ethical Guidelines for Health and Health-Related Research (NEGHHRR) of 2017. This protocol has been approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB 2021-099-01 dated March 25, 2021).

The main concerns for ethics were consent, data privacy, and subject confidentiality. The risks, benefits, and conflicts of interest are discussed in this section from an ethical standpoint.

Recruitment.

The participants will be recruited to answer the online SAQ voluntarily. The recruitment of participants for the KIIs will be chosen through stratified random sampling using a list of those who answered the online SAQ; this will minimize the risk of sampling bias. In addition, none of the participants in the study will have prior contact or association with the researchers. Moreover, power dynamics will not be contacted to recruit respondents. The research objectives, methods, risks, benefits, voluntary participation, withdrawal, and respondents’ rights will be discussed with the respondents in the consent form before KII.

Informed consent will be signified by the potential respondent ticking a box in the online informed consent form and the voluntary participation of the potential respondent to the study after a thorough discussion of the research details. The participant’s consent is voluntary and may be recanted by the participant any time s/he chooses.

Data privacy.

All digital data will be stored in a cloud drive accessible only to the researchers. Subject confidentiality will be upheld through the assignment of control numbers and not requiring participants to divulge the name, address, and other identifying factors not necessary for analysis.

Compensation.

No monetary compensation will be given to the participants, but several tokens will be raffled to all the participants who answered the online survey and did the KIIs.

This research will pose risks to data privacy, as discussed and addressed above. In addition, there will be a risk of social exclusion should data leaks arise due to the stigma against mental health. This risk will be mitigated by properly executing the data collection and analysis plan, excluding personal details and tight data privacy measures. Moreover, there is a risk of psychological distress among the participants due to the sensitive information. This risk will be addressed by subjecting the SAQ and the KII guidelines to the project team’s psychiatrist’s approval, ensuring proper communication with the participants. The KII will also be facilitated by registered clinical psychologists/psychiatrists/social scientists to ensure the participants’ appropriate handling; there will be a briefing and debriefing of the participants before and after the KII proper.

Participation in this study will entail health education and a voluntary referral to a study-affiliated psychiatrist, discussed in previous sections. Moreover, this would contribute to modifications in targeted mental-health campaigns for the 18–25 age group. Summarized findings and recommendations will be channeled to stakeholders for their perusal.

Dissemination.

The results will be actively disseminated through conference presentations, peer-reviewed journals, social media, print and broadcast media, and various stakeholder activities.

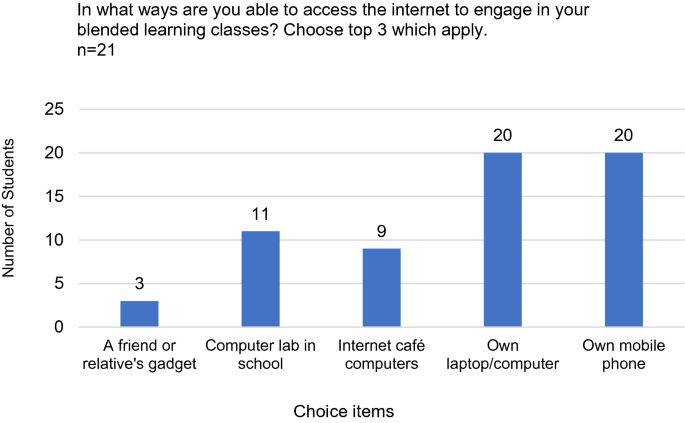

This study protocol rationalizes the examination of the mental health of the college students in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic as the traditional face-to-face classes transitioned to online and modular classes. The pandemic that started in March 2020 is now stretching for more than a year in which prolonged lockdown brings people to experience social isolation and disruption of everyday lifestyle. There is an urgent need to study the psychosocial aspects, particularly those populations that are vulnerable to mental health instability. In the Philippines, where community quarantine is still being imposed across the country, college students face several challenges amidst this pandemic. The pandemic continues to escalate, which may lead to fear and a spectrum of psychological consequences. Universities and colleges play an essential role in supporting college students in their academic, safety, and social needs. The courses of activities implemented by the different universities and colleges may significantly affect their mental well-being status. Our study is particularly interested in the effect of online classes on college students nationwide during the pandemic. The study will estimate this effect on their mental wellbeing since this abrupt transition can lead to depression, stress, or anxiety for some students due to insufficient time to adjust to the new learning environment. The role of social media is also an important exposure to some college students [ 55 , 56 ]. Social media exposure to COVID-19 may be considered a contributing factor to college students’ mental well-being, particularly their stress, depression, and anxiety [ 57 , 58 ]. Despite these known facts, little is known about the effect of transitioning to online learning and social media exposure on the mental health of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. To our knowledge, this is the first study in the Philippines that will use a mixed-method study design to examine the mental health of college students in the entire country. The online survey is a powerful platform to employ our methods.

Additionally, our study will also utilize a qualitative assessment of the college students, which may give significant insights or findings of the experiences of the college students during these trying times that cannot be captured on our online survey. The thematic findings or narratives from the qualitative part of our study will be triangulated with the quantitative analysis for a more robust synthesis. The results will be used to draw conclusions about the mental health status among college students during the pandemic in the country, which will eventually be used to implement key interventions if deemed necessary. A cross-sectional study design for the online survey is one of our study’s limitations in which contrasts will be mainly between participants at a given point of time. In addition, bias arising from residual or unmeasured confounding factors cannot be ruled out.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its accompanying effects will persistently affect the mental wellbeing of college students. Mental health services must be delivered to combat mental instability. In addition, universities and colleges should create an environment that will foster mental health awareness among Filipino college students. The results of our study will tailor the possible coping strategies to meet the specific needs of college students nationwide, thereby promoting psychological resilience.

Exploring the Online Learning Experience of Filipino College Students During Covid-19 Pandemic

- Louie Giray College of Education, Polytechnic University of the Philipines, Taguig City, Philippines

- Daxjhed Gumalin College of Education, Polytechnic University of the Philipines, Taguig City, Philippines

- Jomarie Jacob College of Education, Polytechnic University of the Philipines, Taguig City, Philippines

- Karl Villacorta College of Education, Polytechnic University of the Philipines, Taguig City, Philippines

This study was endeavored to understand the online learning experience of Filipino college students enrolled in the academic year 2020-2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data were obtained through an open-ended qualitative survey. The responses were analyzed and interpreted using thematic analysis. A total of 71 Filipino college students from state and local universities in the Philippines participated in this study. Four themes were classified from the collected data: (1) negative views toward online schooling, (2) positive views toward online schooling, (3) difficulties encountered in online schooling, and (4) motivation to continue studying. The results showed that although many Filipino college students find online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic to be a positive experience such as it provides various conveniences, eliminates the necessity of public transportation amid the COVID-19 pandemic, among others, a more significant number of respondents believe otherwise. The majority of the respondents shared a general difficulty adjusting toward the new online learning setup because of problems related to technology and Internet connectivity, mental health, finances, and time and space management. A large portion of students also got their motivation to continue studying despite the pandemic from fear of being left behind, parental persuasion, and aspiration to help the family.

- EndNote - EndNote format (Macintosh & Windows)

- ProCite - RIS format (Macintosh & Windows)

- Reference Manager - RIS format (Windows only)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms: (1) Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC-BY-SA) that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgment of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal; (2) Authors are able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the non-exclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), with an acknowledgment of its initial publication in this journal; (3) Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work ( See The Effect of Open Access ).

Content Use Policy

Online classes and learning in the Philippines during the Covid-19 Pandemic

13 citations

11 citations

3 citations

1 citations

44 citations

Related Papers (5)

Trending questions (3).

The paper does not provide information about the current state of online counseling in the Philippines.

The paper does not provide a direct answer to the query. The paper discusses the shift to online classes in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic and the issues faced by students and teachers. However, it does not specifically address the impact of online classes on the quality of learning.

The paper does not specifically mention the impact of COVID-19 on online classes in Cebu, Philippines. The paper discusses the general impact of the pandemic on online classes in the Philippines.

Ask Copilot

Related papers

Contributing institutions

Related topics

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Assessing the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, shift to online learning, and social media use on the mental health of college students in the Philippines: A mixed-method study protocol

Leonard thomas s. lim.

1 College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Zypher Jude G. Regencia

2 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

3 Institute of Clinical Epidemiology, National Institutes of Health, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

J. Rem C. Dela Cruz

Frances dominique v. ho, marcela s. rodolfo, josefina ly-uson.

4 Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines

Emmanuel S. Baja

Associated data.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic declared by the WHO has affected many countries rendering everyday lives halted. In the Philippines, the lockdown quarantine protocols have shifted the traditional college classes to online. The abrupt transition to online classes may bring psychological effects to college students due to continuous isolation and lack of interaction with fellow students and teachers. Our study aims to assess Filipino college students’ mental health status and to estimate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift to online learning, and social media use on mental health. In addition, facilitators or stressors that modified the mental health status of the college students during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning will be investigated.

Methods and analysis

Mixed-method study design will be used, which will involve: (1) an online survey to 2,100 college students across the Philippines; and (2) randomly selected 20–40 key informant interviews (KIIs). Online self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) including Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) and Brief-COPE will be used. Moreover, socio-demographic factors, social media usage, shift to online learning factors, family history of mental health and COVID-19, and other factors that could affect mental health will also be included in the SAQ. KIIs will explore factors affecting the student’s mental health, behaviors, coping mechanism, current stressors, and other emotional reactions to these stressors. Associations between mental health outcomes and possible risk factors will be estimated using generalized linear models, while a thematic approach will be made for the findings from the KIIs. Results of the study will then be triangulated and summarized.

Ethics and dissemination

Our study has been approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB 2021-099-01). The results will be actively disseminated through conference presentations, peer-reviewed journals, social media, print and broadcast media, and various stakeholder activities.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak as a global pandemic, and the Philippines is one of the 213 countries affected by the disease [ 1 ]. To reduce the virus’s transmission, the President imposed an enhanced community quarantine in Luzon, the country’s northern and most populous island, on March 16, 2020. This lockdown manifested as curfews, checkpoints, travel restrictions, and suspension of business and school activities [ 2 ]. However, as the virus is yet to be curbed, varying quarantine restrictions are implemented across the country. In addition, schools have shifted to online learning, despite financial and psychological concerns [ 3 ].

Previous outbreaks such as the swine flu crisis adversely influenced the well-being of affected populations, causing them to develop emotional problems and raising the importance of integrating mental health into medical preparedness for similar disasters [ 4 ]. In one study conducted on university students during the swine flu pandemic in 2009, 45% were worried about personally or a family member contracting swine flu, while 10.7% were panicking, feeling depressed, or emotionally disturbed. This study suggests that preventive measures to alleviate distress through health education and promotion are warranted [ 5 ].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers worldwide have been churning out studies on its psychological effects on different populations [ 6 – 9 ]. The indirect effects of COVID-19, such as quarantine measures, the infection of family and friends, and the death of loved ones, could worsen the overall mental wellbeing of individuals [ 6 ]. Studies from 2020 to 2021 link the pandemic to emotional disturbances among those in quarantine, even going as far as giving vulnerable populations the inclination to commit suicide [ 7 , 8 ], persistent effect on mood and wellness [ 9 ], and depression and anxiety [ 10 ].

In the Philippines, a survey of 1,879 respondents measuring the psychological effects of COVID-19 during its early phase in 2020 was released. Results showed that one-fourth of respondents reported moderate-to-severe anxiety, while one-sixth reported moderate-to-severe depression [ 11 ]. In addition, other local studies in 2020 examined the mental health of frontline workers such as nurses and physicians—placing emphasis on the importance of psychological support in minimizing anxiety [ 12 , 13 ].

Since the first wave of the pandemic in 2020, risk factors that could affect specific populations’ psychological well-being have been studied [ 14 , 15 ]. A cohort study on 1,773 COVID-19 hospitalized patients in 2021 found that survivors were mainly troubled with fatigue, muscle weakness, sleep difficulties, and depression or anxiety [ 16 ]. Their results usually associate the crisis with fear, anxiety, depression, reduced sleep quality, and distress among the general population.

Moreover, the pandemic also exacerbated the condition of people with pre-existing psychiatric disorders, especially patients that live in high COVID-19 prevalence areas [ 17 ]. People suffering from mood and substance use disorders that have been infected with COVID-19 showed higher suicide risks [ 7 , 18 ]. Furthermore, a study in 2020 cited the following factors contributing to increased suicide risk: social isolation, fear of contagion, anxiety, uncertainty, chronic stress, and economic difficulties [ 19 ].

Globally, multiple studies have shown that mental health disorders among university student populations are prevalent [ 13 , 20 – 22 ]. In a 2007 survey of 2,843 undergraduate and graduate students at a large midwestern public university in the United States, the estimated prevalence of any depressive or anxiety disorder was 15.6% and 13.0% for undergraduate and graduate students, respectively [ 20 ]. Meanwhile, in a 2013 study of 506 students from 4 public universities in Malaysia, 27.5% and 9.7% had moderate and severe or extremely severe depression, respectively; 34% and 29% had moderate and severe or extremely severe anxiety, respectively [ 21 ]. In China, a 2016 meta-analysis aiming to establish the national prevalence of depression among university students analyzed 39 studies from 1995 to 2015; the meta-analysis found that the overall prevalence of depression was 23.8% across all studies that included 32,694 Chinese university students [ 23 ].

A college student’s mental status may be significantly affected by the successful fulfillment of a student’s role. A 2013 study found that acceptable teaching methods can enhance students’ satisfaction and academic performance, both linked to their mental health [ 24 ]. However, online learning poses multiple challenges to these methods [ 3 ]. Furthermore, a 2020 study found that students’ mental status is affected by their social support systems, which, in turn, may be jeopardized by the COVID-19 pandemic and the physical limitations it has imposed. Support accessible to a student through social ties to other individuals, groups, and the greater community is a form of social support; university students may draw social support from family, friends, classmates, teachers, and a significant other [ 25 , 26 ]. Among individuals undergoing social isolation and distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, social support has been found to be inversely related to depression, anxiety, irritability, sleep quality, and loneliness, with higher levels of social support reducing the risk of depression and improving sleep quality [ 27 ]. Lastly, it has been shown in a 2020 study that social support builds resilience, a protective factor against depression, anxiety, and stress [ 28 ]. Therefore, given the protective effects of social support on psychological health, a supportive environment should be maintained in the classroom. Online learning must be perceived as an inclusive community and a safe space for peer-to-peer interactions [ 29 ]. This is echoed in another study in 2019 on depressed students who narrated their need to see themselves reflected on others [ 30 ]. Whether or not online learning currently implemented has successfully transitioned remains to be seen.

The effect of social media on students’ mental health has been a topic of interest even before the pandemic [ 31 , 32 ]. A systematic review published in 2020 found that social media use is responsible for aggravating mental health problems and that prominent risk factors for depression and anxiety include time spent, activity, and addiction to social media [ 31 ]. Another systematic review published in 2016 argues that the nature of online social networking use may be more important in influencing the symptoms of depression than the duration or frequency of the engagement—suggesting that social rumination and comparison are likely to be candidate mediators in the relationship between depression and social media [ 33 ]. However, their findings also suggest that the relationship between depression and online social networking is complex and necessitates further research to determine the impact of moderators and mediators that underly the positive and negative impact of online social networking on wellbeing [ 33 ].

Despite existing studies already painting a picture of the psychological effects of COVID-19 in the Philippines, to our knowledge, there are still no local studies contextualized to college students living in different regions of the country. Therefore, it is crucial to elicit the reasons and risk factors for depression, stress, and anxiety and determine the potential impact that online learning and social media use may have on the mental health of the said population. In turn, the findings would allow the creation of more context-specific and regionalized interventions that can promote mental wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

The study’s general objective is to assess the mental health status of college students and determine the different factors that influenced them during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, it aims:

- To describe the study population’s characteristics, categorized by their mental health status, which includes depression, anxiety, and stress.

- To determine the prevalence and risk factors of depression, anxiety, and stress among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning.

- To estimate the effect of social media use on depression, anxiety, stress, and coping strategies towards stress among college students and examine whether participant characteristics modified these associations.

- To estimate the effect of online learning shift on depression, anxiety, stress, and coping strategies towards stress among college students and examine whether participant characteristics modified these associations.

- To determine the facilitators or stressors among college students that modified their mental health status during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning.

Study design

A mixed-method study design will be used to address the study’s objectives, which will include Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and an online survey. During the quarantine period of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines from April to November 2021, the study shall occur with the population amid community quarantine and an abrupt transition to online classes. Since this is the Philippines’ first study that will look at the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine, and subsequent shift to online learning, the online survey will be utilized for the quantitative part of the study design. For the qualitative component of the study design, KIIs will determine facilitators or stressors among college students that modified their mental health status during the quarantine period.

Study population

The Red Cross Youth (RCY), one of the Philippine Red Cross’s significant services, is a network of youth volunteers that spans the entire country, having active members in Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. The group is clustered into different age ranges, with the College Red Cross Youth (18–25 years old) being the study’s population of interest. The RCY has over 26,060 students spread across 20 chapters located all over the country’s three major island groups. The RCY is heterogeneously composed, with some members classified as college students and some as out-of-school youth. Given their nationwide scope, disseminating information from the national to the local level is already in place; this is done primarily through email, social media platforms, and text blasts. The research team will leverage these platforms to distribute the online survey questionnaire.

In addition, the online survey will also be open to non-members of the RCY. It will be disseminated through social media and engagements with different university administrators in the country. Stratified random sampling will be done for the KIIs. The KII participants will be equally coming from the country’s four (4) primary areas: 5–10 each from the national capital region (NCR), Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao, including members and non-members of the RCY.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the online survey will include those who are 18–25 years old, currently enrolled in a university, can provide consent for the study, and are proficient in English or Filipino. The exclusion criteria will consist of those enrolled in graduate-level programs (e.g., MD, JD, Master’s, Doctorate), out-of-school youth, and those whose current curricula involve going on duty (e.g., MDs, nursing students, allied medical professions, etc.). The inclusion criteria for the KIIs will include online survey participants who are 18–25 years old, can provide consent for the study, are proficient in English or Filipino, and have access to the internet.

Sample size

A continuity correction method developed by Fleiss et al. (2013) was used to calculate the sample size needed [ 34 ]. For a two-sided confidence level of 95%, with 80% power and the least extreme odds ratio to be detected at 1.4, the computed sample size was 1890. With an adjustment for an estimated response rate of 90%, the total sample size needed for the study was 2,100. To achieve saturation for the qualitative part of the study, 20 to 40 participants will be randomly sampled for the KIIs using the respondents who participated in the online survey [ 35 ].

Study procedure

Self-Administered questionnaire

The study will involve creating, testing, and distributing a self-administered questionnaire (SAQ). All eligible study participants will answer the SAQ on socio-demographic factors such as age, sex, gender, sexual orientation, residence, household income, socioeconomic status, smoking status, family history of mental health, and COVID-19 sickness of immediate family members or friends. The two validated survey tools, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) and Brief-COPE, will be used for the mental health outcome assessment [ 36 – 39 ]. The DASS-21 will measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress [ 40 ], while the Brief-COPE will measure the students’ coping strategies [ 41 ].

For the exposure assessment of the students to social media and shift to online learning, the total time spent on social media (TSSM) per day will be ascertained by querying the participants to provide an estimated time spent daily on social media during and after their online classes. In addition, students will be asked to report their use of the eight commonly used social media sites identified at the start of the study. These sites include Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, Pinterest, TikTok, YouTube, and social messaging sites Viber/WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger with response choices coded as "(1) never," "(2) less often," "(3) every few weeks," "(4) a few times a week," and “(5) daily” [ 42 – 44 ]. Furthermore, a global frequency score will be calculated by adding the response scores from the eight social media sites. The global frequency score will be used as an additional exposure marker of students to social media [ 45 ]. The shift to online learning will be assessed using questions that will determine the participants’ satisfaction with online learning. This assessment is comprised of 8 items in which participants will be asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree.’

The online survey will be virtually distributed in English using the Qualtrics XM™ platform. Informed consent detailing the purpose, risks, benefits, methods, psychological referrals, and other ethical considerations will be included before the participants are allowed to answer the survey. Before administering the online survey, the SAQ shall undergo pilot testing among twenty (20) college students not involved with the study. It aims to measure total test-taking time, respondent satisfaction, and understandability of questions. The survey shall be edited according to the pilot test participant’s responses. Moreover, according to the Philippines’ Data Privacy Act, all the answers will be accessible and used only for research purposes.

Key informant interviews

The research team shall develop the KII concept note, focusing on the extraneous factors affecting the student’s mental health, behaviors, and coping mechanism. Some salient topics will include current stressors (e.g., personal, academic, social), emotional reactions to these stressors, and how they wish to receive support in response to these stressors. The KII will be facilitated by a certified psychologist/psychiatrist/social scientist and research assistants using various online video conferencing software such as Google Meet, Skype, or Zoom. All the KIIs will be recorded and transcribed for analysis. Furthermore, there will be a debriefing session post-KII to address the psychological needs of the participants. Fig 1 presents the diagrammatic flowchart of the study.

Data analyses

Quantitative data.

Descriptive statistics will be calculated, including the prevalence of mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, stress, and coping strategies. In addition, correlation coefficients will be estimated to assess the relations among the different mental health outcomes, covariates, and possible risk factors.

Associations between mental health outcomes and possible risk factors will be estimated using generalized linear models, a standard method for analyzing data in cross-sectional studies. Depending on how rare or common the mental health outcomes are, generalized linear models with either a Poisson distribution and log link function with a robust variance estimator or a Binomial distribution and logit link function will be used to estimate either the adjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) or odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), respectively [ 46 – 49 ]. Separate single-mental health outcome models will be evaluated, and the models will consider the general form:

where Y i will be the mental health outcome (depression, anxiety, stress, and coping strategy) status of subject i and covariates for subject i will be denoted by X 1i to X ri as the possible exposure risk factors (i.e., social media use and shift to online learning) and confounding factors (i.e., age, sex, gender, smoking status, family income, etc.). In addition, we will control for the covariates chosen a priori as potentially important predictors of mental health outcomes in all the models.

Several study characteristics as effect modifiers will also be assessed, including sex, gender, sexual orientation, family income, smoking status, family history of mental health, and Covid-19. We will include interaction terms between the dichotomized modifier variable and markers of social media use (total TSSM and global frequency score) and shift to online learning in the models. The significance of the interaction terms will be evaluated using the likelihood ratio test. All the regression analyses will be done in R ( http://www.r-project.org ). P values ≤ 0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Qualitative data

After transcribing the interviews, the data transcripts will be analyzed using NVivo 1.4.1 software [ 50 ] by three research team members independently using the inductive logic approach in thematic analysis: familiarizing with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing the themes, defining and naming the themes, and producing the report [ 51 ]. Data familiarization will consist of reading and re-reading the data while noting initial ideas. Additionally, coding interesting features of the data will follow systematically across the entire dataset while collating data relevant to each code. Moreover, the open coding of the data will be performed to describe the data into concepts and themes, which will be further categorized to identify distinct concepts and themes [ 52 ].

The three researchers will discuss the results of their thematic analyses. They will compare and contrast the three analyses in order to come up with a thematic map. The final thematic map of the analysis will be generated after checking if the identified themes work in relation to the extracts and the entire dataset. In addition, the selection of clear, persuasive extract examples that will connect the analysis to the research question and literature will be reviewed before producing a scholarly report of the analysis. Additionally, the themes and sub-themes generated will be assessed and discussed in relevance to the study’s objectives. Furthermore, the gathering and analyzing of the data will continue until saturation is reached. Finally, pseudonyms will be used to present quotes from qualitative data.

Data triangulation

Data triangulation using the two different data sources will be conducted to examine the various aspects of the research and will be compared for convergence. This part of the analysis will require listing all the relevant topics or findings from each component of the study and considering where each method’s results converge, offer complementary information on the same issue, or appear to contradict each other. It is crucial to explicitly look for disagreements between findings from different data collection methods because exploration of any apparent inter-method discrepancy may lead to a better understanding of the research question [ 53 , 54 ].

Data management plan

The Project Leader will be responsible for overall quality assurance, with research associates and assistants undertaking specific activities to ensure quality control. Quality will be assured through routine monitoring by the Project Leader and periodic cross-checks against the protocols by the research assistants. Transcribed KIIs and the online survey questionnaire will be used for recording data for each participant in the study. The project leader will be responsible for ensuring the accuracy, completeness, legibility, and timeliness of the data captured in all the forms. Data captured from the online survey or KIIs should be consistent, clarified, and corrected. Each participant will have complete source documentation of records. Study staff will prepare appropriate source documents and make them available to the Project Leader upon request for review. In addition, study staff will extract all data collected in the KII notes or survey forms. These data will be secured and kept in a place accessible to the Project Leader. Data entry and cleaning will be conducted, and final data cleaning, data freezing, and data analysis will be performed. Key informant interviews will always involve two researchers. Where appropriate, quality control for the qualitative data collection will be assured through refresher KII training during research design workshops. The Project Leader will check through each transcript for consistency with agreed standards. Where translations are undertaken, the quality will be assured by one other researcher fluent in that language checking against the original recording or notes.

Ethics approval

The study shall abide by the Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). It will be conducted along with the Guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP), E6 (R2), and other ICH-GCP 6 (as amended); National Ethical Guidelines for Health and Health-Related Research (NEGHHRR) of 2017. This protocol has been approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB 2021-099-01 dated March 25, 2021).

The main concerns for ethics were consent, data privacy, and subject confidentiality. The risks, benefits, and conflicts of interest are discussed in this section from an ethical standpoint.

Recruitment

The participants will be recruited to answer the online SAQ voluntarily. The recruitment of participants for the KIIs will be chosen through stratified random sampling using a list of those who answered the online SAQ; this will minimize the risk of sampling bias. In addition, none of the participants in the study will have prior contact or association with the researchers. Moreover, power dynamics will not be contacted to recruit respondents. The research objectives, methods, risks, benefits, voluntary participation, withdrawal, and respondents’ rights will be discussed with the respondents in the consent form before KII.

Informed consent will be signified by the potential respondent ticking a box in the online informed consent form and the voluntary participation of the potential respondent to the study after a thorough discussion of the research details. The participant’s consent is voluntary and may be recanted by the participant any time s/he chooses.

Data privacy

All digital data will be stored in a cloud drive accessible only to the researchers. Subject confidentiality will be upheld through the assignment of control numbers and not requiring participants to divulge the name, address, and other identifying factors not necessary for analysis.

Compensation

No monetary compensation will be given to the participants, but several tokens will be raffled to all the participants who answered the online survey and did the KIIs.

This research will pose risks to data privacy, as discussed and addressed above. In addition, there will be a risk of social exclusion should data leaks arise due to the stigma against mental health. This risk will be mitigated by properly executing the data collection and analysis plan, excluding personal details and tight data privacy measures. Moreover, there is a risk of psychological distress among the participants due to the sensitive information. This risk will be addressed by subjecting the SAQ and the KII guidelines to the project team’s psychiatrist’s approval, ensuring proper communication with the participants. The KII will also be facilitated by registered clinical psychologists/psychiatrists/social scientists to ensure the participants’ appropriate handling; there will be a briefing and debriefing of the participants before and after the KII proper.

Participation in this study will entail health education and a voluntary referral to a study-affiliated psychiatrist, discussed in previous sections. Moreover, this would contribute to modifications in targeted mental-health campaigns for the 18–25 age group. Summarized findings and recommendations will be channeled to stakeholders for their perusal.

Dissemination

The results will be actively disseminated through conference presentations, peer-reviewed journals, social media, print and broadcast media, and various stakeholder activities.

This study protocol rationalizes the examination of the mental health of the college students in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic as the traditional face-to-face classes transitioned to online and modular classes. The pandemic that started in March 2020 is now stretching for more than a year in which prolonged lockdown brings people to experience social isolation and disruption of everyday lifestyle. There is an urgent need to study the psychosocial aspects, particularly those populations that are vulnerable to mental health instability. In the Philippines, where community quarantine is still being imposed across the country, college students face several challenges amidst this pandemic. The pandemic continues to escalate, which may lead to fear and a spectrum of psychological consequences. Universities and colleges play an essential role in supporting college students in their academic, safety, and social needs. The courses of activities implemented by the different universities and colleges may significantly affect their mental well-being status. Our study is particularly interested in the effect of online classes on college students nationwide during the pandemic. The study will estimate this effect on their mental wellbeing since this abrupt transition can lead to depression, stress, or anxiety for some students due to insufficient time to adjust to the new learning environment. The role of social media is also an important exposure to some college students [ 55 , 56 ]. Social media exposure to COVID-19 may be considered a contributing factor to college students’ mental well-being, particularly their stress, depression, and anxiety [ 57 , 58 ]. Despite these known facts, little is known about the effect of transitioning to online learning and social media exposure on the mental health of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. To our knowledge, this is the first study in the Philippines that will use a mixed-method study design to examine the mental health of college students in the entire country. The online survey is a powerful platform to employ our methods.

Additionally, our study will also utilize a qualitative assessment of the college students, which may give significant insights or findings of the experiences of the college students during these trying times that cannot be captured on our online survey. The thematic findings or narratives from the qualitative part of our study will be triangulated with the quantitative analysis for a more robust synthesis. The results will be used to draw conclusions about the mental health status among college students during the pandemic in the country, which will eventually be used to implement key interventions if deemed necessary. A cross-sectional study design for the online survey is one of our study’s limitations in which contrasts will be mainly between participants at a given point of time. In addition, bias arising from residual or unmeasured confounding factors cannot be ruled out.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its accompanying effects will persistently affect the mental wellbeing of college students. Mental health services must be delivered to combat mental instability. In addition, universities and colleges should create an environment that will foster mental health awareness among Filipino college students. The results of our study will tailor the possible coping strategies to meet the specific needs of college students nationwide, thereby promoting psychological resilience.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to extend their gratitude to the executives of the Philippine Red Cross, notably Senator Richard J. Gordon (Chairman), Ms. Elizabeth S. Zavalla (Secretary-General), and Ms. Maria Theresa S. Bongiad (Manager, Red Cross Youth), for making this project a reality. We also would like to thank all Red Cross Youth Chapters in the Philippines for helping in the pre-implementation stage of the project.

Funding Statement

This project is being supported by the American Red Cross through the Philippine Red Cross and Red Cross Youth. The funder will not have a role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

- PLoS One. 2022; 17(5): e0267555.

Decision Letter 0

PONE-D-21-17998Assessing the Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic, Shift to Online Learning, and Social Media Use on Mental Health Among College Students in the Philippines: A Mixed-Method Study ProtocolPLOS ONE

Dear Dr. Baja,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands. Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process. Please address all comments from reviewers 1 and 2. Please disregard the comments from reviewers 3 and 4 to the effect that protocols shouldn't be published; PLOS ONE considers study protocols for publication ( https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/what-we-publish#loc-study-protocols ).

Please submit your revised manuscript by Nov 25 2021 11:59PM. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp . When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

Please include the following items when submitting your revised manuscript:

- A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). You should upload this letter as a separate file labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

- A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

- An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Manuscript'.

If you would like to make changes to your financial disclosure, please include your updated statement in your cover letter. Guidelines for resubmitting your figure files are available below the reviewer comments at the end of this letter.

If applicable, we recommend that you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io to enhance the reproducibility of your results. Protocols.io assigns your protocol its own identifier (DOI) so that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols . Additionally, PLOS ONE offers an option for publishing peer-reviewed Lab Protocol articles, which describe protocols hosted on protocols.io. Read more information on sharing protocols at https://plos.org/protocols?utm_medium=editorial-email&utm_source=authorletters&utm_campaign=protocols .

We look forward to receiving your revised manuscript.

Kind regards,

Yann Benetreau, PhD

Senior Editor

Journal Requirements:

When submitting your revision, we need you to address these additional requirements.

1. Please ensure that your manuscript meets PLOS ONE's style requirements, including those for file naming. The PLOS ONE style templates can be found at

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=wjVg/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_main_body.pdf and https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=ba62/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_title_authors_affiliations.pdf .

2. Thank you for stating the following in the Acknowledgments Section of your manuscript:

“The research received a grant from the American Red Cross through the Philippine Red Cross and Red Cross Youth.”

We note that you have provided additional information within the Acknowledgements Section that is not currently declared in your Funding Statement. Please note that funding information should not appear in the Acknowledgments section or other areas of your manuscript. We will only publish funding information present in the Funding Statement section of the online submission form.

Please remove any funding-related text from the manuscript and let us know how you would like to update your Funding Statement. Currently, your Funding Statement reads as follows:

“This project is being supported by the American Red Cross through the Philippine Red Cross and Red Cross Youth. The funder will not have a role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.”

Please include your amended statements within your cover letter; we will change the online submission form on your behalf.

3. Please include a caption for figure 1.

Additional Editor Comments (if provided):

Dear Author

The manuscript is deemed to be not suitable for accepting for corrections or publications as it never meets the basic quality of an SSCI journal. Please refer to the comments from the reviewers.

[Note: HTML markup is below. Please do not edit.]

Reviewers' comments:

Reviewer's Responses to Questions

Comments to the Author

1. Does the manuscript provide a valid rationale for the proposed study, with clearly identified and justified research questions?

The research question outlined is expected to address a valid academic problem or topic and contribute to the base of knowledge in the field.

Reviewer #1: Yes

Reviewer #2: Partly

Reviewer #3: Yes

Reviewer #4: No

2. Is the protocol technically sound and planned in a manner that will lead to a meaningful outcome and allow testing the stated hypotheses?

The manuscript should describe the methods in sufficient detail to prevent undisclosed flexibility in the experimental procedure or analysis pipeline, including sufficient outcome-neutral conditions (e.g. necessary controls, absence of floor or ceiling effects) to test the proposed hypotheses and a statistical power analysis where applicable. As there may be aspects of the methodology and analysis which can only be refined once the work is undertaken, authors should outline potential assumptions and explicitly describe what aspects of the proposed analyses, if any, are exploratory.

Reviewer #3: Partly

Reviewer #4: Partly

3. Is the methodology feasible and described in sufficient detail to allow the work to be replicable?

Descriptions of methods and materials in the protocol should be reported in sufficient detail for another researcher to reproduce all experiments and analyses. The protocol should describe the appropriate controls, sample size calculations, and replication needed to ensure that the data are robust and reproducible.

Reviewer #2: No

Reviewer #4: Yes

4. Have the authors described where all data underlying the findings will be made available when the study is complete?

The PLOS Data policy requires authors to make all data underlying the findings described in their manuscript fully available without restriction, with rare exception, at the time of publication. The data should be provided as part of the manuscript or its supporting information, or deposited to a public repository. For example, in addition to summary statistics, the data points behind means, medians and variance measures should be available. If there are restrictions on publicly sharing data—e.g. participant privacy or use of data from a third party—those must be specified.

Reviewer #3: No

5. Is the manuscript presented in an intelligible fashion and written in standard English?

PLOS ONE does not copyedit accepted manuscripts, so the language in submitted articles must be clear, correct, and unambiguous. Any typographical or grammatical errors should be corrected at revision, so please note any specific errors here.

6. Review Comments to the Author

Please use the space provided to explain your answers to the questions above and, if applicable, provide comments about issues authors must address before this protocol can be accepted for publication. You may also include additional comments for the author, including concerns about research or publication ethics.

You may also provide optional suggestions and comments to authors that they might find helpful in planning their study.

(Please upload your review as an attachment if it exceeds 20,000 characters)