- Systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 19 June 2020

Quantitative measures of health policy implementation determinants and outcomes: a systematic review

- Peg Allen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7000-796X 1 ,

- Meagan Pilar 1 ,

- Callie Walsh-Bailey 1 ,

- Cole Hooley 2 ,

- Stephanie Mazzucca 1 ,

- Cara C. Lewis 3 ,

- Kayne D. Mettert 3 ,

- Caitlin N. Dorsey 3 ,

- Jonathan Purtle 4 ,

- Maura M. Kepper 1 ,

- Ana A. Baumann 5 &

- Ross C. Brownson 1 , 6

Implementation Science volume 15 , Article number: 47 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

56 Citations

34 Altmetric

Metrics details

Public policy has tremendous impacts on population health. While policy development has been extensively studied, policy implementation research is newer and relies largely on qualitative methods. Quantitative measures are needed to disentangle differential impacts of policy implementation determinants (i.e., barriers and facilitators) and outcomes to ensure intended benefits are realized. Implementation outcomes include acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, compliance/fidelity, feasibility, penetration, sustainability, and costs. This systematic review identified quantitative measures that are used to assess health policy implementation determinants and outcomes and evaluated the quality of these measures.

Three frameworks guided the review: Implementation Outcomes Framework (Proctor et al.), Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (Damschroder et al.), and Policy Implementation Determinants Framework (Bullock et al.). Six databases were searched: Medline, CINAHL Plus, PsycInfo, PAIS, ERIC, and Worldwide Political. Searches were limited to English language, peer-reviewed journal articles published January 1995 to April 2019. Search terms addressed four levels: health, public policy, implementation, and measurement. Empirical studies of public policies addressing physical or behavioral health with quantitative self-report or archival measures of policy implementation with at least two items assessing implementation outcomes or determinants were included. Consensus scoring of the Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale assessed the quality of measures.

Database searches yielded 8417 non-duplicate studies, with 870 (10.3%) undergoing full-text screening, yielding 66 studies. From the included studies, 70 unique measures were identified to quantitatively assess implementation outcomes and/or determinants. Acceptability, feasibility, appropriateness, and compliance were the most commonly measured implementation outcomes. Common determinants in the identified measures were organizational culture, implementation climate, and readiness for implementation, each aspects of the internal setting. Pragmatic quality ranged from adequate to good, with most measures freely available, brief, and at high school reading level. Few psychometric properties were reported.

Conclusions

Well-tested quantitative measures of implementation internal settings were under-utilized in policy studies. Further development and testing of external context measures are warranted. This review is intended to stimulate measure development and high-quality assessment of health policy implementation outcomes and determinants to help practitioners and researchers spread evidence-informed policies to improve population health.

Registration

Not registered

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

This systematic review identified 70 quantitative measures of implementation outcomes or determinants in health policy studies.

Readiness to implement and organizational climate and culture were commonly assessed determinants, but fewer studies assessed policy actor relationships or implementation outcomes of acceptability, fidelity/compliance, appropriateness, feasibility, or implementation costs.

Study team members rated most identified measures’ pragmatic properties as good, meaning they are straightforward to use, but few studies documented pilot or psychometric testing of measures.

Further development and dissemination of valid and reliable measures of policy implementation outcomes and determinants can facilitate identification, use, and spread of effective policy implementation strategies.

Despite major impacts of policy on population health [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ], there have been relatively few policy studies in dissemination and implementation (D&I) science to inform implementation strategies and evaluate implementation efforts [ 8 ]. While health outcomes of policies are commonly studied, fewer policy studies assess implementation processes and outcomes. Of 146 D&I studies funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through D&I funding announcements from 2007 to 2014, 12 (8.2%) were policy studies that assessed policy content, policy development processes, or health outcomes of policies, representing 10.5% of NIH D&I funding [ 8 ]. Eight of the 12 studies (66.7%) assessed health outcomes, while only five (41.6%) assessed implementation [ 8 ].

Our ability to explore the differential impact of policy implementation determinants and outcomes and disentangle these from health benefits and other societal outcomes requires high quality quantitative measures [ 9 ]. While systematic reviews of measures of implementation of evidence-based interventions (in clinical and community settings) have been conducted in recent years [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ], to our knowledge, no reviews have explored the quality of quantitative measures of determinants and outcomes of policy implementation.

Policy implementation research in political science and the social sciences has been active since at least the 1970s and has much to contribute to the newer field of D&I research [ 1 , 14 ]. Historically, theoretical frameworks and policy research largely emphasized policy development or analysis of the content of policy documents themselves [ 15 ]. For example, Kingdon’s Multiple Streams Framework and its expansions have been widely used in political science and the social sciences more broadly to describe how factors related to sociopolitical climate, attributes of a proposed policy, and policy actors (e.g., organizations, sectors, individuals) contribute to policy change [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Policy frameworks can also inform implementation planning and evaluation in D&I research. Although authors have named policy stages since the 1950s [ 19 , 20 ], Sabatier and Mazmanian’s Policy Implementation Process Framework was one of the first such frameworks that gained widespread use in policy implementation research [ 21 ] and later in health promotion [ 22 ]. Yet, available implementation frameworks are not often used to guide implementation strategies or inform why a policy worked in one setting but not another [ 23 ]. Without explicit focus on implementation, the intended benefits of health policies may go unrealized, and the ability may be lost to move the field forward to understand policy implementation (i.e., our collective knowledge building is dampened) [ 24 ].

Differences in perspectives and terminology between D&I and policy research in political science are noteworthy to interpret the present review. For example, Proctor et al. use the term implementation outcomes for what policy researchers call policy outputs [ 14 , 20 , 25 ]. To non-D&I policy researchers, policy implementation outcomes refer to the health outcomes in the target population [ 20 ]. D&I science uses the term fidelity [ 26 ]; policy researchers write about compliance [ 20 ]. While D&I science uses the terms outer setting, outer context, or external context to point to influences outside the implementing organization [ 26 , 27 , 28 ], non-D&I policy research refers to policy fields [ 24 ] which are networks of agencies that carry out policies and programs.

Identification of valid and reliable quantitative measures of health policy implementation processes is needed. These measures are needed to advance from classifying constructs to understanding causality in policy implementation research [ 29 ]. Given limited resources, policy implementers also need to know which aspects of implementation are key to improve policy acceptance, compliance, and sustainability to reap the intended health benefits [ 30 ]. Both pragmatic and psychometrically sound measures are needed to accomplish these objectives [ 10 , 11 , 31 , 32 ], so the field can explore the influence of nuanced determinants and generate reliable and valid findings.

To fill this void in the literature, this systematic review of health policy implementation measures aimed to (1) identify quantitative measures used to assess health policy implementation outcomes (IOF outcomes commonly called policy outputs in policy research) and inner and outer setting determinants, (2) describe and assess pragmatic quality of policy implementation measures, (3) describe and assess the quality of psychometric properties of identified instruments, and (4) elucidate health policy implementation measurement gaps.

The study team used systematic review procedures developed by Lewis and colleagues for reviews of D&I research measures and received detailed guidance from the Lewis team coauthors for each step [ 10 , 11 ]. We followed the PRISMA reporting guidelines as shown in the checklist (Supplemental Table 1 ). We have also provided a publicly available website of measures identified in this review ( https://www.health-policy-measures.org/ ).

For the purposes of this review, policy and policy implementation are defined as follows. We deemed public policy to include legislation at the federal, state/province/regional unit, or local levels; and governmental regulations, whether mandated by national, state/province, or local level governmental agencies or boards of elected officials (e.g., state boards of education in the USA) [ 4 , 20 ]. Here, public policy implementation is defined as the carrying out of a governmental mandate by public or private organizations and groups of organizations [ 20 ].

Two widely used frameworks from the D&I field guide the present review, and a third recently developed framework that bridges policy and D&I research. In the Implementation Outcomes Framework (IOF), Proctor and colleagues identify and define eight implementation outcomes that are differentiated from health outcomes: acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, cost, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability [ 25 ]. In the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), Damschroder and colleagues articulate determinants of implementation including the domains of intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting of an organization, characteristics of individuals within organizations, and process [ 33 ]. Finally, Bullock developed the Policy Implementation Determinants Framework to present a balanced framework that emphasizes both internal setting constructs and external setting constructs including policy actor relationships and networks, political will for implementation, and visibility of policy actors [ 34 ]. The constructs identified in these frameworks were used to guide our list of implementation determinants and outcomes.

Through EBSCO, we searched MEDLINE, PsycInfo, and CINAHL Plus. Through ProQuest, we searched PAIS, Worldwide Political, and ERIC. Due to limited time and staff in the 12-month study, we did not search the grey literature. We used multiple search terms in each of four required levels: health, public policy, implementation, and measurement (Table 1 ). Table 1 shows search terms for each string. Supplemental Tables 2 and 3 show the final search syntax applied in EBSCO and ProQuest.

The authors developed the search strings and terms based on policy implementation framework reviews [ 34 , 35 ], additional policy implementation frameworks [ 21 , 22 ], labels and definitions of the eight implementation outcomes identified by Proctor et al. [ 25 ], CFIR construct labels and definitions [ 9 , 33 ], and additional D&I research and search term sources [ 28 , 36 , 37 , 38 ] (Table 1 ). The full study team provided three rounds of feedback on draft terms, and a library scientist provided additional synonyms and search terms. For each test search, we calculated the percentage of 18 benchmark articles the search captured. We determined a priori 80% as an acceptable level of precision.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This review addressed only measures of implementation by organizations mandated to act by governmental units or legislation. Measures of behavior changes by individuals in target populations as a result of legislation or governmental regulations and health status changes were outside the realm of this review.

There were several inclusion criteria: (1) empirical studies of the implementation of public policies already passed or approved that addressed physical or behavioral health, (2) quantitative self-report or archival measurement methods utilized, (3) published in peer-reviewed journals from January 1995 through April 2019, (4) published in the English language, (5) public policy implementation studies from any continent or international governing body, and (6) at least two transferable quantitative self-report or archival items that assessed implementation determinants [ 33 , 34 ] and/or IOF implementation outcomes [ 25 ]. This study sought to identify transferable measures that could be used to assess multiple policies and contexts. Here, a transferable item is defined as one that needed no wording changes or only a change in the referent (e.g., policy title or topic such as tobacco or malaria) to make the item applicable to other policies or settings [ 11 ]. The year 1995 was chosen as a starting year because that is about when web-based quantitative surveying began [ 39 ]. Table 2 provides definitions of the IOF implementation outcomes and the selected determinants of implementation. Broader constructs, such as readiness for implementation, contained multiple categories.

Exclusion criteria in the searches included (1) non-empiric health policy journal articles (e.g., conceptual articles, editorials); (2) narrative and systematic reviews; (3) studies with only qualitative assessment of health policy implementation; (4) empiric studies reported in theses and books; (5) health policy studies that only assessed health outcomes (i.e., target population changes in health behavior or status); (6) bill analyses, stakeholder perceptions assessed to inform policy development, and policy content analyses without implementation assessment; (7) studies of changes made in a private business not encouraged by public policy; and (8) countries with authoritarian regimes. We electronically programmed the searches to exclude policy implementation studies from countries that are not democratically governed due to vast differences in policy environments and implementation factors.

Screening procedures

Citations were downloaded into EndNote version 7.8 and de-duplicated electronically. We conducted dual independent screening of titles and abstracts after two group pilot screening sessions in which we clarified inclusion and exclusion criteria and screening procedures. Abstract screeners used Covidence systematic review software [ 40 ] to code inclusion as yes or no. Articles were included in full-text review if one screener coded it as meeting the inclusion criteria. Full-text screening via dual independent screening was coded in Covidence [ 40 ], with weekly meetings to reach consensus on inclusion/exclusion discrepancies. Screeners also coded one of the pre-identified reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction strategy

Extraction elements included information about (1) measure meta-data (e.g., measure name, total number of items, number of transferable items) and studies (e.g., policy topic, country, setting), (2) development and testing of the measure, (3) implementation outcomes and determinants assessed (Table 2 ), (4) pragmatic characteristics, and (5) psychometric properties. Where needed, authors were emailed to obtain the full measure and measure development information. Two coauthors (MP, CWB) reached consensus on extraction elements. For each included measure, a primary extractor conducted initial entries and coding. Due to time and staff limitations in the 12-month study, we did not search for each empirical use of the measure. A secondary extractor checked the entries, noting any discrepancies for discussion in consensus meetings. Multiple measures in a study were extracted separately.

Quality assessment of measures

To assess the quality of measures, we applied the Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scales (PAPERS) developed by Lewis et al. [ 10 , 11 , 41 , 42 ]. PAPERS includes assessment of five pragmatic instrument characteristics that affect the level of ease or difficulty to use the instrument: brevity (number of items), simplicity of language (readability level), cost (whether it is freely available), training burden (extent of data collection training needed), and analysis burden (ease or difficulty of interpretation of scoring and results). Lewis and colleagues developed the pragmatic domains and rating scales with stakeholder and D&I researchers input [ 11 , 41 , 42 ] and developed the psychometric rating scales in collaboration with D&I researchers [ 10 , 11 , 43 ]. The psychometric rating scale has nine properties (Table 3 ): internal consistency; norms; responsiveness; convergent, discriminant, and known-groups construct validity; predictive and concurrent criterion validity; and structural validity. In both the pragmatic and psychometric scales, reported evidence for each domain is scored from poor (− 1), none/not reported (0), minimal/emerging (1), adequate (2), good (3), or excellent (4). Higher values are indicative of more desirable pragmatic characteristics (e.g., fewer items, freely available, scoring instructions, and interpretations provided) and stronger evidence of psychometric properties (e.g., adequate to excellent reliability and validity) (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5 ).

Data synthesis and presentation

This section describes the synthesis of measure transferability, empiric use study settings and policy topics, and PAPERS scoring. Two coauthors (MP, CWB) consensus coded measures into three categories of item transferability based on quartile item transferability percentages: mostly transferable (≥ 75% of items deemed transferable), partially transferable (25–74% of items deemed transferable), and setting-specific (< 25% of items deemed transferable). Items were deemed transferable if no wording changes or only a change in the referent (e.g., policy title or topic) was needed to make the item applicable to the implementation of other policies or in other settings. Abstractors coded study settings into one of five categories: hospital or outpatient clinics; mental or behavioral health facilities; healthcare cost, access, or quality; schools; community; and multiple. Abstractors also coded policy topics to healthcare cost, access, or quality; mental or behavioral health; infectious or chronic diseases; and other, while retaining documentation of subtopics such as tobacco, physical activity, and nutrition. Pragmatic scores were totaled for the five properties, with possible total scores of − 5 to 20, with higher values indicating greater ease to use the instrument. Psychometric property total scores for the nine properties were also calculated, with possible scores of − 9 to 36, with higher values indicating evidence of multiple types of validity.

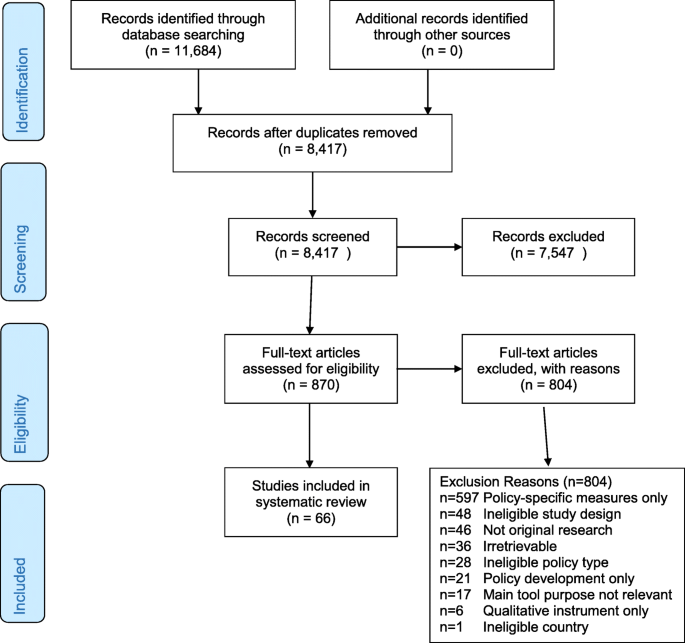

The database searches yielded 11,684 articles, of which 3267 were duplicates (Fig. 1 ). Titles and abstracts of the 8417 articles were independently screened by two team members; 870 (10.3%) were selected for full-text screening by at least one screener. Of the 870 studies, 804 were excluded at full-text screening or during extraction attempts with the consensus of two coauthors; 66 studies were included. Two coauthors (MP, CWB) reached consensus on extraction and coding of information on 70 unique quantitative eligible measures identified in the 66 included studies plus measure development articles where obtained. Nine measures were used in more than one included study. Detailed information on identified measures is publicly available at https://www.health-policy-measures.org/ .

PRISMA flow diagram

The most common exclusion reason was lack of transferable items in quantitative measures of policy implementation ( n = 597) (Fig. 1 ). While this review focused on transferable measures across any health issue or setting, researchers addressing specific health policies or settings may find the excluded studies of interest. The frequencies of the remaining exclusion reasons are listed in Fig. 1 .

A variety of health policy topics and settings from over two dozen countries were found in the database searches. For example, the searches identified quantitative and mixed methods implementation studies of legislation (such as tobacco smoking bans), regulations (such as food/menu labeling requirements), governmental policies that mandated specific clinical practices (such as vaccination or access to HIV antiretroviral treatment), school-based interventions (such as government-mandated nutritional content and physical activity), and other public policies.

Among the 70 unique quantitative implementation measures, 15 measures were deemed mostly transferable (at least 75% transferable, Table 4 ). Twenty-three measures were categorized as partially transferable (25 to 74% of items deemed transferable, Table 5 ); 32 measures were setting-specific (< 25% of items deemed transferable, data not shown).

Implementation outcomes

Among the 70 measures, the most commonly assessed implementation outcomes were fidelity/compliance of the policy implementation to the government mandate (26%), acceptability of the policy to implementers (24%), perceived appropriateness of the policy (17%), and feasibility of implementation (17%) (Table 2 ). Fidelity/compliance was sometimes assessed by asking implementers the extent to which they had modified a mandated practice [ 45 ]. Sometimes, detailed checklists were used to assess the extent of compliance with the many mandated policy components, such as school nutrition policies [ 83 ]. Acceptability was assessed by asking staff or healthcare providers in implementing agencies their level of agreement with the provided statements about the policy mandate, scored in Likert scales. Only eight (11%) of the included measures used multiple transferable items to assess adoption, and only eight (11%) assessed penetration.

Twenty-six measures of implementation costs were found during full-text screening (10 in included studies and 14 in excluded studies, data not shown). The cost time horizon varied from 12 months to 21 years, with most cost measures assessed at multiple time points. Ten of the 26 measures addressed direct implementation costs. Nine studies reported cost modeling findings. The implementation cost survey developed by Vogler et al. was extensive [ 53 ]. It asked implementing organizations to note policy impacts in medication pricing, margins, reimbursement rates, and insurance co-pays.

Determinants of implementation

Within the 70 included measures, the most commonly assessed implementation determinants were readiness for implementation (61% assessed any readiness component) and the general organizational culture and climate (39%), followed by the specific policy implementation climate within the implementation organization/s (23%), actor relationships and networks (17%), political will for policy implementation (11%), and visibility of the policy role and policy actors (10%) (Table 2 ). Each component of readiness for implementation was commonly assessed: communication of the policy (31%, 22 of 70 measures), policy awareness and knowledge (26%), resources for policy implementation (non-training resources 27%, training 20%), and leadership commitment to implement the policy (19%).

Only two studies assessed organizational structure as a determinant of health policy implementation. Lavinghouze and colleagues assessed the stability of the organization, defined as whether re-organization happens often or not, within a set of 9-point Likert items on multiple implementation determinants designed for use with state-level public health practitioners, and assessed whether public health departments were stand-alone agencies or embedded within agencies addressing additional services, such as social services [ 69 ]. Schneider and colleagues assessed coalition structure as an implementation determinant, including items on the number of organizations and individuals on the coalition roster, number that regularly attend coalition meetings, and so forth [ 72 ].

Tables of measures

Tables 4 and 5 present the 38 measures of implementation outcomes and/or determinants identified out of the 70 included measures with at least 25% of items transferable (useable in other studies without wording changes or by changing only the policy name or other referent). Table 4 shows 15 mostly transferable measures (at least 75% transferable). Table 5 shows 23 partially transferable measures (25–74% of items deemed transferable). Separate measure development articles were found for 20 of the 38 measures; the remaining measures seemed to be developed for one-time, study-specific use by the empirical study authors cited in the tables. Studies listed in Tables 4 and 5 were conducted most commonly in the USA ( n = 19) or Europe ( n = 11). A few measures were used elsewhere: Africa ( n = 3), Australia ( n = 1), Canada ( n = 1), Middle East ( n = 1), Southeast Asia ( n = 1), or across multiple continents ( n = 1).

Quality of identified measures

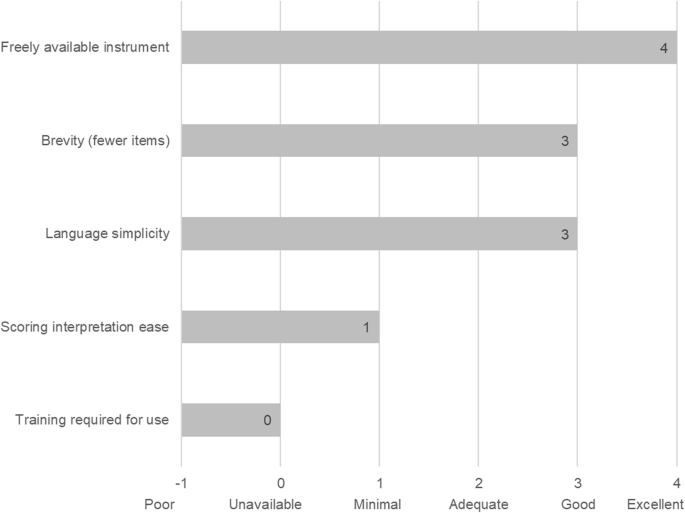

Figure 2 shows the median pragmatic quality ratings across the 38 measures with at least 25% transferable items shown in Tables 4 and 5 . Higher scores are desirable and indicate the measures are easier to use (Table 3 ). Overall, the measures were freely available in the public domain (median score = 4), brief with a median of 11–50 items (median score = 3), and had good readability, with a median reading level between 8th and 12th grade (median score = 3). However, instructions on how to score and interpret item scores were lacking, with a median score of 1, indicating the measures did not include suggestions for interpreting score ranges, clear cutoff scores, and instructions for handling missing data. In general, information on training requirements or availability of self-training manuals on how to use the measures was not reported in the included study or measure development article/s (median score = 0, not reported). Total pragmatic rating scores among the 38 measures with at least 25% of items transferable ranged from 7 to 17 (Tables 4 and 5 ), with a median total score of 12 out of a possible total score of 20. Median scores for each pragmatic characteristic were the same across all measures as for the 38 mostly or partially transferable measures, with a median total score of 11 across all measures.

Pragmatic rating scale results across identified measures. Footnote: pragmatic criteria scores from Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale (PAPERS) (Lewis et al. [ 11 ], Stanick et al. [ 42 ]). Total possible score = 20, total median score across 38 measures = 11. Scores ranged from 0 to 18. Rating scales for each domain are provided in Supplemental Table 4

Few psychometric properties were reported. The study team found few reports of pilot testing and measure refinement as well. Among the 38 measures with at least 25% transferable items, the psychometric properties from the PAPERS rating scale total scores ranged from − 1 to 17 (Tables 4 and 5 ), with a median total score of 5 out of a possible total score of 36. Higher scores indicate more types of validity and reliability were reported with high quality. The 32 measures with calculable norms had a median norms PAPERS score of 3 (good), indicating appropriate sample size and distribution. The nine measures with reported internal consistency mostly showed Cronbach’s alphas in the adequate (0.70 to 0.79) to excellent (≥ 90) range, with a median of 0.78 (PAPERS score of 2, adequate) indicating adequate internal consistency. The five measures with reported structural validity had a median PAPERS score of 2, adequate (range 1 to 3, poor to good), indicating the sample size was sufficient and the factor analysis goodness of fit was reasonable. Among the 38 measures, no reports were found for responsiveness, convergent validity, discriminant validity, known-groups construct validity, or predictive or concurrent criterion validity.

In this systematic review, we sought to identify quantitative measures used to assess health policy implementation outcomes and determinants, rate the pragmatic and psychometric quality of identified measures, and point to future directions to address measurement gaps. In general, the identified measures are easy to use and freely available, but we found little data on validity and reliability. We found more quantitative measures of intra-organizational determinants of policy implementation than measures of the relationships and interactions between organizations that influence policy implementation. We found a limited number of measures that had been developed for or used to assess one of the eight IOF policy implementation outcomes that can be applied to other policies or settings, which may speak more to differences in terms used by policy researchers and D&I researchers than to differences in conceptualizations of policy implementation. Authors used a variety of terms and rarely provided definitions of the constructs the items assessed. Input from experts in policy implementation is needed to better understand and define policy implementation constructs for use across multiple fields involved in policy-related research.

We found several researchers had used well-tested measures of implementation determinants from D&I research or from organizational behavior and management literature (Tables 4 and 5 ). For internal setting of implementing organizations, whether mandated through public policy or not, well-developed and tested measures are available. However, a number of authors crafted their own items, with or without pilot testing, and used a variety of terms to describe what the items assessed. Further dissemination of the availability of well-tested measures to policy researchers is warranted [ 9 , 13 ].

What appears to be a larger gap involves the availability of well-developed and tested quantitative measures of the external context affecting policy implementation that can be used across multiple policy settings and topics [ 9 ]. Lack of attention to how a policy initiative fits with the external implementation context during policymaking and lack of policymaker commitment of adequate resources for implementation contribute to this gap [ 23 , 93 ]. Recent calls and initiatives to integrate health policies during policymaking and implementation planning will bring more attention to external contexts affecting not only policy development but implementation as well [ 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 ]. At the present time, it is not well-known which internal and external determinants are most essential to guide and achieve sustainable policy implementation [ 100 ]. Identification and dissemination of measures that assess factors that facilitate the spread of evidence-informed policy implementation (e.g., relative advantage, flexibility) will also help move policy implementation research forward [ 1 , 9 ].

Given the high potential population health impact of evidence-informed policies, much more attention to policy implementation is needed in D&I research. Few studies from non-D&I researchers reported policy implementation measure development procedures, pilot testing, scoring procedures and interpretation, training of data collectors, or data analysis procedures. Policy implementation research could benefit from the rigor of D&I quantitative research methods. And D&I researchers have much to learn about the contexts and practical aspects of policy implementation and can look to the rich depth of information in qualitative and mixed methods studies from other fields to inform quantitative measure development and testing [ 101 , 102 , 103 ].

Limitations

This systematic review has several limitations. First, the four levels of the search string and multiple search terms in each level were applied only to the title, abstract, and subject headings, due to limitations of the search engines, so we likely missed pertinent studies. Second, a systematic approach with stakeholder input is needed to expand the definitions of IOF implementation outcomes for policy implementation. Third, although the authors value intra-organizational policymaking and implementation, the study team restricted the search to governmental policies due to limited time and staffing in the 12-month study. Fourth, by excluding tools with only policy-specific implementation measures, we excluded some well-developed and tested instruments in abstract and full-text screening. Since only 12 measures had 100% transferable items, researchers may need to pilot test wording modifications of other items. And finally, due to limited time and staffing, we only searched online for measures and measures development articles and may have missed separately developed pragmatic information, such as training and scoring materials not reported in a manuscript.

Despite the limitations, several recommendations for measure development follow from the findings and related literature [ 1 , 11 , 20 , 35 , 41 , 104 ], including the need to (1) conduct systematic, mixed-methods procedures (concept mapping, expert panels) to refine policy implementation outcomes, (2) expand and more fully specify external context domains for policy implementation research and evaluation, (3) identify and disseminate well-developed measures for specific policy topics and settings, (4) ensure that policy implementation improves equity rather than exacerbating disparities [ 105 ], and (5) develop evidence-informed policy implementation guidelines.

Easy-to-use, reliable, and valid quantitative measures of policy implementation can further our understanding of policy implementation processes, determinants, and outcomes. Due to the wide array of health policy topics and implementation settings, sound quantitative measures that can be applied across topics and settings will help speed learnings from individual studies and aid in the transfer from research to practice. Quantitative measures can inform the implementation of evidence-informed policies to further the spread and effective implementation of policies to ultimately reap greater population health benefit. This systematic review of measures is intended to stimulate measure development and high-quality assessment of health policy implementation outcomes and predictors to help practitioners and researchers spread evidence-informed policies to improve population health and reduce inequities.

Availability of data and materials

A compendium of identified measures is available for dissemination at https://www.health-policy-measures.org/ . A link will be provided on the website of the Prevention Research Center, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, at https://prcstl.wustl.edu/ . The authors invite interested organizations to provide a link to the compendium. Citations and abstracts of excluded policy-specific measures are available on request.

Abbreviations

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature

Dissemination and implementation science

Elton B. Stephens Company

Education Resources Information Center

Implementation Outcomes Framework

Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Purtle J, Dodson EA, Brownson RC. Policy dissemination research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice, Second Edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Google Scholar

Brownson RC, Baker EA, Deshpande AD, Gillespie KN. Evidence-based public health. Third ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Guide to Community Preventive Services. About the community guide.: community preventive services task force; 2020 [updated October 03, 2019; cited 2020. Available from: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/ .

Eyler AA, Chriqui JF, Moreland-Russell S, Brownson RC, editors. Prevention, policy, and public health, first edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016.

Andre FE, Booy R, Bock HL, Clemens J, Datta SK, John TJ, et al. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death, and inequity worldwide. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008 February 2008. Contract No.: 07-040089.

Cheng JJ, Schuster-Wallace CJ, Watt S, Newbold BK, Mente A. An ecological quantification of the relationships between water, sanitation and infant, child, and maternal mortality. Environ Health. 2012;11:4.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Levy DT, Li Y, Yuan Z. Impact of nations meeting the MPOWER targets between 2014 and 2016: an update. Tob Control. 2019.

Purtle J, Peters R, Brownson RC. A review of policy dissemination and implementation research funded by the National Institutes of Health, 2007-2014. Implement Sci. 2016;11:1.

Lewis CC, Proctor EK, Brownson RC. Measurement issues in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Ga C, Proctor EK, editors. Disssemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice, Second Edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M, Martinez RG. Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence-based rating criteria. Implement Sci. 2015;10:155.

Lewis CC, Mettert KD, Dorsey CN, Martinez RG, Weiner BJ, Nolen E, et al. An updated protocol for a systematic review of implementation-related measures. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):66.

Chaudoir SR, Dugan AG, Barr CH. Measuring factors affecting implementation of health innovations: a systematic review of structural, organizational, provider, patient, and innovation level measures. Implement Sci. 2013;8:22.

Rabin BA, Lewis CC, Norton WE, Neta G, Chambers D, Tobin JN, et al. Measurement resources for dissemination and implementation research in health. Implement Sci. 2016;11:42.

Nilsen P, Stahl C, Roback K, Cairney P. Never the twain shall meet?--a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implement Sci. 2013;8:63.

Sabatier PA, editor. Theories of the Policy Process. New York, NY: Routledge; 2019.

Kingdon J. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies, second edition. Second ed. New York: Longman; 1995.

Jones MD, Peterson HL, Pierce JJ, Herweg N, Bernal A, Lamberta Raney H, et al. A river runs through it: a multiple streams meta-review. Policy Stud J. 2016;44(1):13–36.

Fowler L. Using the multiple streams framework to connect policy adoption to implementation. Policy Studies Journal. 2020 (11 Feb).

Howlett M, Mukherjee I, Woo JJ. From tools to toolkits in policy design studies: the new design orientation towards policy formulation research. Policy Polit. 2015;43(2):291–311.

Natesan SD, Marathe RR. Literature review of public policy implementation. Int J Public Policy. 2015;11(4):219–38.

Sabatier PA, Mazmanian. Implementation of public policy: a framework of analysis. Policy Studies Journal. 1980 (January).

Sabatier PA. Theories of the Policy Process. Westview; 2007.

Tomm-Bonde L, Schreiber RS, Allan DE, MacDonald M, Pauly B, Hancock T, et al. Fading vision: knowledge translation in the implementation of a public health policy intervention. Implement Sci. 2013;8:59.

Roll S, Moulton S, Sandfort J. A comparative analysis of two streams of implementation research. Journal of Public and Nonprofit Affairs. 2017;3(1):3–22.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice, second edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3):337–50.

Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Kreuter MW, Weaver NL. A glossary for dissemination and implementation research in health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(2):117–23.

PubMed Google Scholar

Lewis CC, Klasnja P, Powell BJ, Lyon AR, Tuzzio L, Jones S, et al. From classification to causality: advancing understanding of mechanisms of change in implementation science. Front Public Health. 2018;6:136.

Boyd MR, Powell BJ, Endicott D, Lewis CC. A method for tracking implementation strategies: an exemplar implementing measurement-based care in community behavioral health clinics. Behav Ther. 2018;49(4):525–37.

Glasgow RE. What does it mean to be pragmatic? Pragmatic methods, measures, and models to facilitate research translation. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40(3):257–65.

Glasgow RE, Riley WT. Pragmatic measures: what they are and why we need them. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(2):237–43.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Bullock HL. Understanding the implementation of evidence-informed policies and practices from a policy perspective: a critical interpretive synthesis in: How do systems achieve their goals? the role of implementation in mental health systems improvement [Dissertation]. Hamilton, Ontario: McMaster University; 2019.

Watson DP, Adams EL, Shue S, Coates H, McGuire A, Chesher J, et al. Defining the external implementation context: an integrative systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):209.

McKibbon KA, Lokker C, Wilczynski NL, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Davis DA, et al. A cross-sectional study of the number and frequency of terms used to refer to knowledge translation in a body of health literature in 2006: a Tower of Babel? Implement Sci. 2010;5:16.

Terwee CB, Jansma EP, Riphagen II, de Vet HC. Development of a methodological PubMed search filter for finding studies on measurement properties of measurement instruments. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(8):1115–23.

Egan M, Maclean A, Sweeting H, Hunt K. Comparing the effectiveness of using generic and specific search terms in electronic databases to identify health outcomes for a systematic review: a prospective comparative study of literature search method. BMJ Open. 2012;2:3.

Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2009.

Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation. https://www.covidence.org . Accessed Mar 2019.

Powell BJ, Stanick CF, Halko HM, Dorsey CN, Weiner BJ, Barwick MA, et al. Toward criteria for pragmatic measurement in implementation research and practice: a stakeholder-driven approach using concept mapping. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):118.

Stanick CF, Halko HM, Nolen EA, Powell BJ, Dorsey CN, Mettert KD, et al. Pragmatic measures for implementation research: development of the Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale (PAPERS). Transl Behav Med. 2019.

Henrikson NB, Blasi PR, Dorsey CN, Mettert KD, Nguyen MB, Walsh-Bailey C, et al. Psychometric and pragmatic properties of social risk screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6S1):S13–24.

Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, Calloway A. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2013;8:65.

Lau AS, Brookman-Frazee L. The 4KEEPS study: identifying predictors of sustainment of multiple practices fiscally mandated in children’s mental health services. Implement Sci. 2016;11:1–8.

Ekvall G. Organizational climate for creativity and innovation. European J Work Organizational Psychology. 1996;5(1):105–23.

Lövgren G, Eriksson S, Sandman PO. Effects of an implemented care policy on patient and personnel experiences of care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2002;16(1):3–11.

Dwyer DJ, Ganster DC. The effects of job demands and control on employee attendance and satisfaction. J Organ Behav. 1991;12:595–608.

Condon-Paoloni D, Yeatman HR, Grigonis-Deane E. Health-related claims on food labels in Australia: understanding environmental health officers’ roles and implications for policy. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(1):81–8.

Patterson MG, West MA, Shackleton VJ, Dawson JF, Lawthom R, Maitlis S, et al. Validating the organizational climate measure: links to managerial practices, productivity and innovation. J Organ Behav. 2005;26:279–408.

Glisson C, Green P, Williams NJ. Assessing the Organizational Social Context (OSC) of child welfare systems: implications for research and practice. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(9):621–32.

Beidas RS, Aarons G, Barg F, Evans A, Hadley T, Hoagwood K, et al. Policy to implementation: evidence-based practice in community mental health--study protocol. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):38.

Eisenberger R, Cummings J, Armeli S, Lynch P. Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. J Appl Psychol. 1997;82:812–20.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Eby L, George K, Brown BL. Going tobacco-free: predictors of clinician reactions and outcomes of the NY state office of alcoholism and substance abuse services tobacco-free regulation. J Subst Abus Treat. 2013;44(3):280–7.

Vogler S, Zimmermann N, de Joncheere K. Policy interventions related to medicines: survey of measures taken in European countries during 2010-2015. Health Policy. 2016;120(12):1363–77.

Wanberg CRB, Banas JT. Predictors and outcomes of openness to change in a reorganizing workplace. J Applied Psychology. 2000;85:132–42.

CAS Google Scholar

Hardy LJ, Wertheim P, Bohan K, Quezada JC, Henley E. A model for evaluating the activities of a coalition-based policy action group: the case of Hermosa Vida. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(4):514–23.

Gavriilidis G, Östergren P-O. Evaluating a traditional medicine policy in South Africa: phase 1 development of a policy assessment tool. Glob Health Action. 2012;5:17271.

Hongoro C, Rutebemberwa E, Twalo T, Mwendera C, Douglas M, Mukuru M, et al. Analysis of selected policies towards universal health coverage in Uganda: the policy implementation barometer protocol. Archives Public Health. 2018;76:12.

Roeseler A, Solomon M, Beatty C, Sipler AM. The tobacco control network’s policy readiness and stage of change assessment: what the results suggest for moving tobacco control efforts forward at the state and territorial levels. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(1):9–19.

Brämberg EB, Klinga C, Jensen I, Busch H, Bergström G, Brommels M, et al. Implementation of evidence-based rehabilitation for non-specific back pain and common mental health problems: a process evaluation of a nationwide initiative. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):79.

Rütten A, Lüschen G, von Lengerke T, Abel T, Kannas L, Rodríguez Diaz JA, et al. Determinants of health policy impact: comparative results of a European policymaker study. Sozial-Und Praventivmedizin. 2003;48(6):379–91.

Smith SN, Lai Z, Almirall D, Goodrich DE, Abraham KM, Nord KM, et al. Implementing effective policy in a national mental health reengagement program for veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205(2):161–70.

Carasso BS, Lagarde M, Cheelo C, Chansa C, Palmer N. Health worker perspectives on user fee removal in Zambia. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10:40.

Goldsmith REH, C.F. Measuring consumer innovativeness. J Acad Mark Sci. 1991;19(3):209–21.

Webster CA, Caputi P, Perreault M, Doan R, Doutis P, Weaver RG. Elementary classroom teachers’ adoption of physical activity promotion in the context of a statewide policy: an innovation diffusion and socio-ecologic perspective. J Teach Phys Educ. 2013;32(4):419–40.

Aarons GA, Glisson C, Hoagwood K, Kelleher K, Landsverk J, Cafri G. Psychometric properties and U.S. National norms of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Psychol Assess. 2010;22(2):356–65.

Gill KJ, Campbell E, Gauthier G, Xenocostas S, Charney D, Macaulay AC. From policy to practice: implementing frontline community health services for substance dependence--study protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9:108.

Lavinghouze SR, Price AW, Parsons B. The environmental assessment instrument: harnessing the environment for programmatic success. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10(2):176–85.

Bull FC, Milton K, Kahlmeier S. National policy on physical activity: the development of a policy audit tool. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11(2):233–40.

Bull F, Milton K, Kahlmeier S, Arlotti A, Juričan AB, Belander O, et al. Turning the tide: national policy approaches to increasing physical activity in seven European countries. British J Sports Med. 2015;49(11):749–56.

Schneider EC, Smith ML, Ory MG, Altpeter M, Beattie BL, Scheirer MA, et al. State fall prevention coalitions as systems change agents: an emphasis on policy. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17(2):244–53.

Helfrich CD, Savitz LA, Swiger KD, Weiner BJ. Adoption and implementation of mandated diabetes registries by community health centers. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(1,Suppl):S50-S65.

Donchin M, Shemesh AA, Horowitz P, Daoud N. Implementation of the Healthy Cities’ principles and strategies: an evaluation of the Israel Healthy Cities network. Health Promot Int. 2006;21(4):266–73.

Were MC, Emenyonu N, Achieng M, Shen C, Ssali J, Masaba JP, et al. Evaluating a scalable model for implementing electronic health records in resource-limited settings. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17(3):237–44.

Konduri N, Sawyer K, Nizova N. User experience analysis of e-TB Manager, a nationwide electronic tuberculosis recording and reporting system in Ukraine. ERJ Open Research. 2017;3:2.

McDonnell E, Probart C. School wellness policies: employee participation in the development process and perceptions of the policies. J Child Nutr Manag. 2008;32:1.

Mersini E, Hyska J, Burazeri G. Evaluation of national food and nutrition policy in Albania. Zdravstveno Varstvo. 2017;56(2):115–23.

Cavagnero E, Daelmans B, Gupta N, Scherpbier R, Shankar A. Assessment of the health system and policy environment as a critical complement to tracking intervention coverage for maternal, newborn, and child health. Lancet. 2008;371 North American Edition(9620):1284-93.

Lehman WE, Greener JM, Simpson DD. Assessing organizational readiness for change. J Subst Abus Treat. 2002;22(4):197–209.

Pankratz M, Hallfors D, Cho H. Measuring perceptions of innovation adoption: the diffusion of a federal drug prevention policy. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(3):315–26.

Cook JM, Thompson R, Schnurr PP. Perceived characteristics of intervention scale: development and psychometric properties. Assessment. 2015;22(6):704–14.

Probart C, McDonnell ET, Jomaa L, Fekete V. Lessons from Pennsylvania’s mixed response to federal school wellness law. Health Aff. 2010;29(3):447–53.

Probart C, McDonnell E, Weirich JE, Schilling L, Fekete V. Statewide assessment of local wellness policies in Pennsylvania public school districts. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(9):1497–502.

Rakic S, Novakovic B, Stevic S, Niskanovic J. Introduction of safety and quality standards for private health care providers: a case-study from the Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17(1):92.

Rozema AD, Mathijssen JJP, Jansen MWJ, van Oers JAM. Sustainability of outdoor school ground smoking bans at secondary schools: a mixed-method study. Eur J Pub Health. 2018;28(1):43–9.

Barbero C, Moreland-Russell S, Bach LE, Cyr J. An evaluation of public school district tobacco policies in St. Louis County, Missouri. J Sch Health. 2013;83(8):525–32.

Williams KM, Kirsh S, Aron D, Au D, Helfrich C, Lambert-Kerzner A, et al. Evaluation of the Veterans Health Administration’s specialty care transformational initiatives to promote patient-centered delivery of specialty care: a mixed-methods approach. Telemed J E-Health. 2017;23(7):577–89.

Spencer E, Walshe K. National quality improvement policies and strategies in European healthcare systems. Quality Safety Health Care. 2009;18(Suppl 1):i22–i7.

Assunta M, Dorotheo EU. SEATCA Tobacco Industry Interference Index: a tool for measuring implementation of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Article 5.3. Tob Control. 2016;25(3):313–8.

Tummers L. Policy alienation of public professionals: the construct and its measurement. Public Adm Rev. 2012;72(4):516–25.

Tummers L, Bekkers V. Policy implementation, street-level bureaucracy, and the importance of discretion. Public Manag Rev. 2014;16(4):527–47.

Raghavan R, Bright CL, Shadoin AL. Toward a policy ecology of implementation of evidence-based practices in public mental health settings. Implement Sci. 2008;3:26.

Peters D, Harting J, van Oers H, Schuit J, de Vries N, Stronks K. Manifestations of integrated public health policy in Dutch municipalities. Health Promot Int. 2016;31(2):290–302.

Tosun J, Lang A. Policy integration: mapping the different concepts. Policy Studies. 2017;38(6):553–70.

Tubbing L, Harting J, Stronks K. Unravelling the concept of integrated public health policy: concept mapping with Dutch experts from science, policy, and practice. Health Policy. 2015;119(6):749–59.

Donkin A, Goldblatt P, Allen J, Nathanson V, Marmot M. Global action on the social determinants of health. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;3(Suppl 1):e000603-e.

Baum F, Friel S. Politics, policies and processes: a multidisciplinary and multimethods research programme on policies on the social determinants of health inequity in Australia. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e017772-e.

Delany T, Lawless A, Baum F, Popay J, Jones L, McDermott D, et al. Health in All Policies in South Australia: what has supported early implementation? Health Promot Int. 2016;31(4):888–98.

Valaitis R, MacDonald M, Kothari A, O'Mara L, Regan S, Garcia J, et al. Moving towards a new vision: implementation of a public health policy intervention. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:412.

Bennett LM, Gadlin H, Marchand, C. Collaboration team science: a field guide. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; 2018. Contract No.: NIH Publication No. 18-7660.

Mazumdar M, Messinger S, Finkelstein DM, Goldberg JD, Lindsell CJ, Morton SC, et al. Evaluating academic scientists collaborating in team-based research: a proposed framework. Acad Med. 2015;90(10):1302–8.

Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Green LW. Building capacity for evidence-based public health: reconciling the pulls of practice and the push of research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:27–53.

Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Future issues in dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. Second Edition ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018.

Thomson K, Hillier-Brown F, Todd A, McNamara C, Huijts T, Bambra C. The effects of public health policies on health inequalities in high-income countries: an umbrella review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):869.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the policy expertise and guidance of Alexandra Morshed and the administrative support of Mary Adams, Linda Dix, and Cheryl Valko at the Prevention Research Center, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis. We thank Lori Siegel, librarian, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, for assistance with search terms and procedures. We appreciate the D&I contributions of Enola Proctor and Byron Powell at the Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, that informed this review. We thank Russell Glasgow, University of Colorado Denver, for guidance on the overall review and pragmatic measure criteria.

This project was funded March 2019 through February 2020 by the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital, with support from the Washington University in St. Louis Institute of Clinical and Translational Science Pilot Program, NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant UL1 TR002345. The project was also supported by the National Cancer Institute P50CA244431, Cooperative Agreement number U48DP006395-01-00 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, R01MH106510 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases award number P30DK020579. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital, Washington University in St. Louis Institute of Clinical and Translational Science, National Institutes of Health, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Prevention Research Center, Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1196, St. Louis, MO, 63130, USA

Peg Allen, Meagan Pilar, Callie Walsh-Bailey, Stephanie Mazzucca, Maura M. Kepper & Ross C. Brownson

School of Social Work, Brigham Young University, 2190 FJSB, Provo, UT, 84602, USA

Cole Hooley

Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, 1730 Minor Ave, Seattle, WA, 98101, USA

Cara C. Lewis, Kayne D. Mettert & Caitlin N. Dorsey

Department of Health Management & Policy, Drexel University Dornsife School of Public Health, Nesbitt Hall, 3215 Market St, Philadelphia, PA, 19104, USA

Jonathan Purtle

Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1196, St. Louis, MO, 63130, USA

Ana A. Baumann

Department of Surgery (Division of Public Health Sciences) and Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center, Washington University School of Medicine, 4921 Parkview Place, Saint Louis, MO, 63110, USA

Ross C. Brownson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Review methodology and quality assessment scale: CCL, KDM, CND. Eligibility criteria: PA, RCB, CND, KDM, SM, MP, JP. Search strings and terms: CH, PA, MP with review by AB, RCB, CND, CCL, MMK, SM, KDM. Framework selection: PA, AB, CH, MP. Abstract screening: PA, CH, MMK, SM, MP. Full-text screening: PA, CH, MP. Pilot extraction: PA, DNC, CH, KDM, SM, MP. Data extraction: MP, CWB. Data aggregation: MP, CWB. Writing: PA, RCB, JP. Editing: RCB, JP, SM, AB, CD, CH, MMK, CCL, KM, MP, CWB. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Peg Allen .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare they have no conflicting interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: table s1.

. PRISMA checklist. Table S2 . Electronic search terms for databases searched through EBSCO. Table S3 . Electronic search terms for searches conducted through PROQUEST. Table S4: PAPERS Pragmatic rating scales. Table S5 . PAPERS Psychometric rating scales.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Allen, P., Pilar, M., Walsh-Bailey, C. et al. Quantitative measures of health policy implementation determinants and outcomes: a systematic review. Implementation Sci 15 , 47 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01007-w

Download citation

Received : 24 March 2020

Accepted : 05 June 2020

Published : 19 June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01007-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Implementation science

- Health policy

- Policy implementation

- Implementation

- Public policy

- Psychometric

Implementation Science

ISSN: 1748-5908

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences pp 27–49 Cite as

Quantitative Research

- Leigh A. Wilson 2 , 3

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 13 January 2019

3980 Accesses

4 Citations

Quantitative research methods are concerned with the planning, design, and implementation of strategies to collect and analyze data. Descartes, the seventeenth-century philosopher, suggested that how the results are achieved is often more important than the results themselves, as the journey taken along the research path is a journey of discovery. High-quality quantitative research is characterized by the attention given to the methods and the reliability of the tools used to collect the data. The ability to critique research in a systematic way is an essential component of a health professional’s role in order to deliver high quality, evidence-based healthcare. This chapter is intended to provide a simple overview of the way new researchers and health practitioners can understand and employ quantitative methods. The chapter offers practical, realistic guidance in a learner-friendly way and uses a logical sequence to understand the process of hypothesis development, study design, data collection and handling, and finally data analysis and interpretation.

- Quantitative

- Epidemiology

- Data analysis

- Methodology

- Interpretation

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Babbie ER. The practice of social research. 14th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth Cengage; 2016.

Google Scholar

Descartes. Cited in Halverston, W. (1976). In: A concise introduction to philosophy, 3rd ed. New York: Random House; 1637.

Doll R, Hill AB. The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits. BMJ. 1954;328(7455):1529–33. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1529 .

Article Google Scholar

Liamputtong P. Research methods in health: foundations for evidence-based practice. 3rd ed. Melbourne: Oxford University Press; 2017.

McNabb DE. Research methods in public administration and nonprofit management: quantitative and qualitative approaches. 2nd ed. New York: Armonk; 2007.

Merriam-Webster. Dictionary. http://www.merriam-webster.com . Accessed 20th December 2017.

Olesen Larsen P, von Ins M. The rate of growth in scientific publication and the decline in coverage provided by Science Citation Index. Scientometrics. 2010;84(3):575–603.

Pannucci CJ, Wilkins EG. Identifying and avoiding bias in research. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(2):619–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181de24bc .

Petrie A, Sabin C. Medical statistics at a glance. 2nd ed. London: Blackwell Publishing; 2005.

Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Pearson Publishing; 2009.

Sheehan J. Aspects of research methodology. Nurse Educ Today. 1986;6:193–203.

Wilson LA, Black DA. Health, science research and research methods. Sydney: McGraw Hill; 2013.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Science and Health, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, Australia

Leigh A. Wilson

Faculty of Health Science, Discipline of Behavioural and Social Sciences in Health, University of Sydney, Lidcombe, NSW, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Leigh A. Wilson .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Pranee Liamputtong

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Wilson, L.A. (2019). Quantitative Research. In: Liamputtong, P. (eds) Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_54

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_54

Published : 13 January 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-5250-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-5251-4

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 4

- How to appraise quantitative research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

This article has a correction. Please see:

- Correction: How to appraise quantitative research - April 01, 2019

- Xabi Cathala 1 ,

- Calvin Moorley 2

- 1 Institute of Vocational Learning , School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University , London , UK

- 2 Nursing Research and Diversity in Care , School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to Mr Xabi Cathala, Institute of Vocational Learning, School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University London UK ; cathalax{at}lsbu.ac.uk and Dr Calvin Moorley, Nursing Research and Diversity in Care, School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University, London SE1 0AA, UK; Moorleyc{at}lsbu.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2018-102996

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Some nurses feel that they lack the necessary skills to read a research paper and to then decide if they should implement the findings into their practice. This is particularly the case when considering the results of quantitative research, which often contains the results of statistical testing. However, nurses have a professional responsibility to critique research to improve their practice, care and patient safety. 1 This article provides a step by step guide on how to critically appraise a quantitative paper.

Title, keywords and the authors

The authors’ names may not mean much, but knowing the following will be helpful:

Their position, for example, academic, researcher or healthcare practitioner.

Their qualification, both professional, for example, a nurse or physiotherapist and academic (eg, degree, masters, doctorate).

This can indicate how the research has been conducted and the authors’ competence on the subject. Basically, do you want to read a paper on quantum physics written by a plumber?

The abstract is a resume of the article and should contain:

Introduction.

Research question/hypothesis.

Methods including sample design, tests used and the statistical analysis (of course! Remember we love numbers).

Main findings.

Conclusion.

The subheadings in the abstract will vary depending on the journal. An abstract should not usually be more than 300 words but this varies depending on specific journal requirements. If the above information is contained in the abstract, it can give you an idea about whether the study is relevant to your area of practice. However, before deciding if the results of a research paper are relevant to your practice, it is important to review the overall quality of the article. This can only be done by reading and critically appraising the entire article.

The introduction

Example: the effect of paracetamol on levels of pain.

My hypothesis is that A has an effect on B, for example, paracetamol has an effect on levels of pain.

My null hypothesis is that A has no effect on B, for example, paracetamol has no effect on pain.

My study will test the null hypothesis and if the null hypothesis is validated then the hypothesis is false (A has no effect on B). This means paracetamol has no effect on the level of pain. If the null hypothesis is rejected then the hypothesis is true (A has an effect on B). This means that paracetamol has an effect on the level of pain.

Background/literature review

The literature review should include reference to recent and relevant research in the area. It should summarise what is already known about the topic and why the research study is needed and state what the study will contribute to new knowledge. 5 The literature review should be up to date, usually 5–8 years, but it will depend on the topic and sometimes it is acceptable to include older (seminal) studies.

Methodology

In quantitative studies, the data analysis varies between studies depending on the type of design used. For example, descriptive, correlative or experimental studies all vary. A descriptive study will describe the pattern of a topic related to one or more variable. 6 A correlational study examines the link (correlation) between two variables 7 and focuses on how a variable will react to a change of another variable. In experimental studies, the researchers manipulate variables looking at outcomes 8 and the sample is commonly assigned into different groups (known as randomisation) to determine the effect (causal) of a condition (independent variable) on a certain outcome. This is a common method used in clinical trials.

There should be sufficient detail provided in the methods section for you to replicate the study (should you want to). To enable you to do this, the following sections are normally included:

Overview and rationale for the methodology.

Participants or sample.

Data collection tools.

Methods of data analysis.

Ethical issues.

Data collection should be clearly explained and the article should discuss how this process was undertaken. Data collection should be systematic, objective, precise, repeatable, valid and reliable. Any tool (eg, a questionnaire) used for data collection should have been piloted (or pretested and/or adjusted) to ensure the quality, validity and reliability of the tool. 9 The participants (the sample) and any randomisation technique used should be identified. The sample size is central in quantitative research, as the findings should be able to be generalised for the wider population. 10 The data analysis can be done manually or more complex analyses performed using computer software sometimes with advice of a statistician. From this analysis, results like mode, mean, median, p value, CI and so on are always presented in a numerical format.

The author(s) should present the results clearly. These may be presented in graphs, charts or tables alongside some text. You should perform your own critique of the data analysis process; just because a paper has been published, it does not mean it is perfect. Your findings may be different from the author’s. Through critical analysis the reader may find an error in the study process that authors have not seen or highlighted. These errors can change the study result or change a study you thought was strong to weak. To help you critique a quantitative research paper, some guidance on understanding statistical terminology is provided in table 1 .

- View inline

Some basic guidance for understanding statistics

Quantitative studies examine the relationship between variables, and the p value illustrates this objectively. 11 If the p value is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected and the hypothesis is accepted and the study will say there is a significant difference. If the p value is more than 0.05, the null hypothesis is accepted then the hypothesis is rejected. The study will say there is no significant difference. As a general rule, a p value of less than 0.05 means, the hypothesis is accepted and if it is more than 0.05 the hypothesis is rejected.

The CI is a number between 0 and 1 or is written as a per cent, demonstrating the level of confidence the reader can have in the result. 12 The CI is calculated by subtracting the p value to 1 (1–p). If there is a p value of 0.05, the CI will be 1–0.05=0.95=95%. A CI over 95% means, we can be confident the result is statistically significant. A CI below 95% means, the result is not statistically significant. The p values and CI highlight the confidence and robustness of a result.

Discussion, recommendations and conclusion

The final section of the paper is where the authors discuss their results and link them to other literature in the area (some of which may have been included in the literature review at the start of the paper). This reminds the reader of what is already known, what the study has found and what new information it adds. The discussion should demonstrate how the authors interpreted their results and how they contribute to new knowledge in the area. Implications for practice and future research should also be highlighted in this section of the paper.

A few other areas you may find helpful are:

Limitations of the study.

Conflicts of interest.

Table 2 provides a useful tool to help you apply the learning in this paper to the critiquing of quantitative research papers.

Quantitative paper appraisal checklist

- 1. ↵ Nursing and Midwifery Council , 2015 . The code: standard of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf ( accessed 21.8.18 ).

- Gerrish K ,

- Moorley C ,

- Tunariu A , et al

- Shorten A ,

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Correction notice This article has been updated since its original publication to update p values from 0.5 to 0.05 throughout.

Linked Articles

- Miscellaneous Correction: How to appraise quantitative research BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and RCN Publishing Company Ltd Evidence-Based Nursing 2019; 22 62-62 Published Online First: 31 Jan 2019. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102996corr1

Read the full text or download the PDF:

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Quantitative Approaches for the Evaluation of Implementation Research Studies

Justin d. smith.

1 Center for Prevention Implementation Methodology (Ce-PIM) for Drug Abuse and HIV, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 750 N Lake Shore Dr., Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Mohamed Hasan

2 Center for Healthcare Studies, Institute of Public Health and Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, 633 N St. Claire St., Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Authors’ contributions