Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques & Examples

Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques & Examples

Published on September 19, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on June 22, 2023.

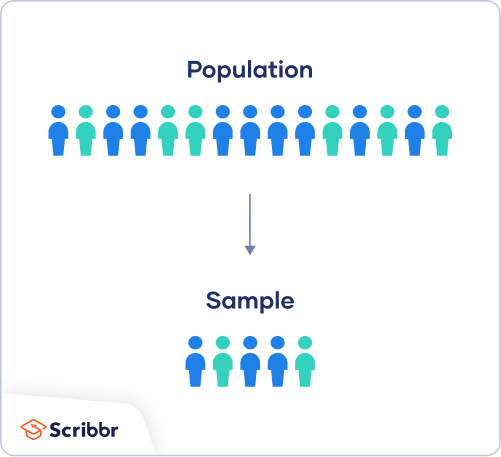

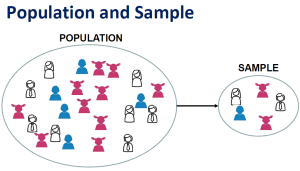

When you conduct research about a group of people, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every person in that group. Instead, you select a sample . The sample is the group of individuals who will actually participate in the research.

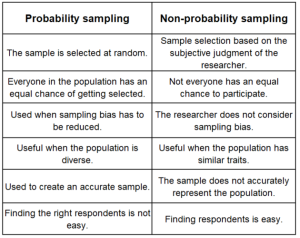

To draw valid conclusions from your results, you have to carefully decide how you will select a sample that is representative of the group as a whole. This is called a sampling method . There are two primary types of sampling methods that you can use in your research:

- Probability sampling involves random selection, allowing you to make strong statistical inferences about the whole group.

- Non-probability sampling involves non-random selection based on convenience or other criteria, allowing you to easily collect data.

You should clearly explain how you selected your sample in the methodology section of your paper or thesis, as well as how you approached minimizing research bias in your work.

Table of contents

Population vs. sample, probability sampling methods, non-probability sampling methods, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about sampling.

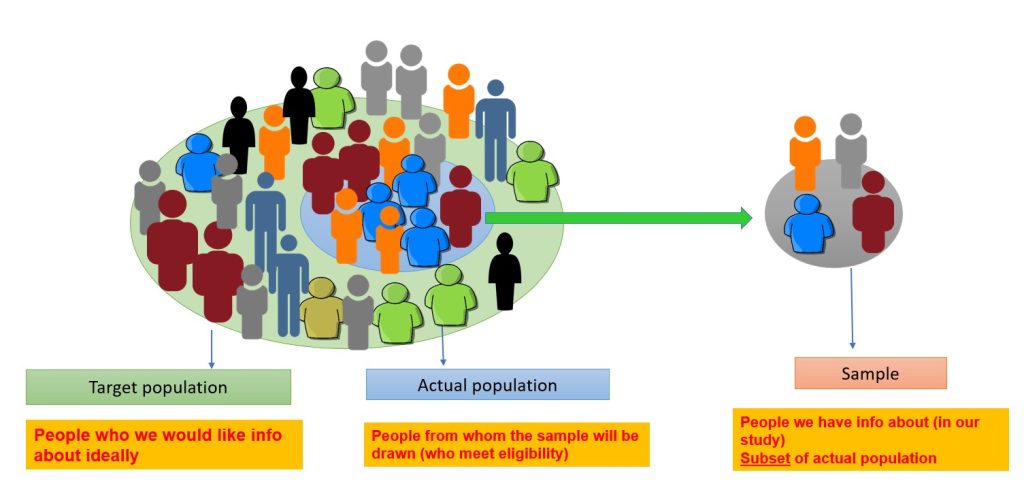

First, you need to understand the difference between a population and a sample , and identify the target population of your research.

- The population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about.

- The sample is the specific group of individuals that you will collect data from.

The population can be defined in terms of geographical location, age, income, or many other characteristics.

It is important to carefully define your target population according to the purpose and practicalities of your project.

If the population is very large, demographically mixed, and geographically dispersed, it might be difficult to gain access to a representative sample. A lack of a representative sample affects the validity of your results, and can lead to several research biases , particularly sampling bias .

Sampling frame

The sampling frame is the actual list of individuals that the sample will be drawn from. Ideally, it should include the entire target population (and nobody who is not part of that population).

Sample size

The number of individuals you should include in your sample depends on various factors, including the size and variability of the population and your research design. There are different sample size calculators and formulas depending on what you want to achieve with statistical analysis .

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Probability sampling means that every member of the population has a chance of being selected. It is mainly used in quantitative research . If you want to produce results that are representative of the whole population, probability sampling techniques are the most valid choice.

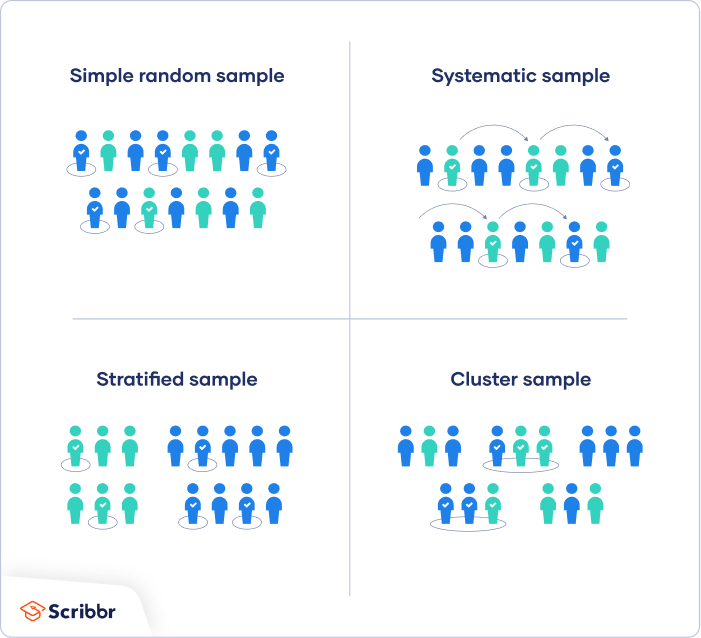

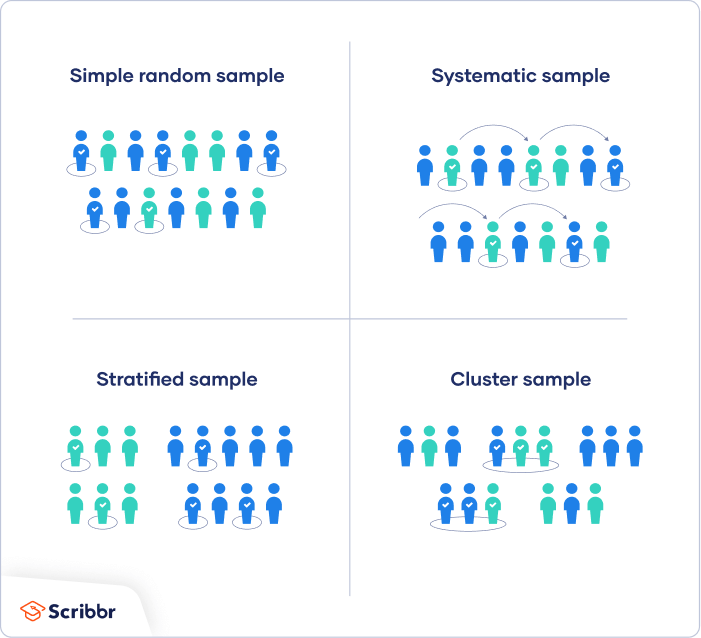

There are four main types of probability sample.

1. Simple random sampling

In a simple random sample, every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. Your sampling frame should include the whole population.

To conduct this type of sampling, you can use tools like random number generators or other techniques that are based entirely on chance.

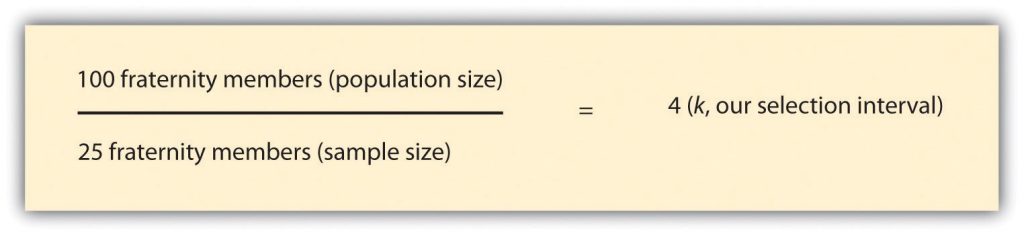

2. Systematic sampling

Systematic sampling is similar to simple random sampling, but it is usually slightly easier to conduct. Every member of the population is listed with a number, but instead of randomly generating numbers, individuals are chosen at regular intervals.

If you use this technique, it is important to make sure that there is no hidden pattern in the list that might skew the sample. For example, if the HR database groups employees by team, and team members are listed in order of seniority, there is a risk that your interval might skip over people in junior roles, resulting in a sample that is skewed towards senior employees.

3. Stratified sampling

Stratified sampling involves dividing the population into subpopulations that may differ in important ways. It allows you draw more precise conclusions by ensuring that every subgroup is properly represented in the sample.

To use this sampling method, you divide the population into subgroups (called strata) based on the relevant characteristic (e.g., gender identity, age range, income bracket, job role).

Based on the overall proportions of the population, you calculate how many people should be sampled from each subgroup. Then you use random or systematic sampling to select a sample from each subgroup.

4. Cluster sampling

Cluster sampling also involves dividing the population into subgroups, but each subgroup should have similar characteristics to the whole sample. Instead of sampling individuals from each subgroup, you randomly select entire subgroups.

If it is practically possible, you might include every individual from each sampled cluster. If the clusters themselves are large, you can also sample individuals from within each cluster using one of the techniques above. This is called multistage sampling .

This method is good for dealing with large and dispersed populations, but there is more risk of error in the sample, as there could be substantial differences between clusters. It’s difficult to guarantee that the sampled clusters are really representative of the whole population.

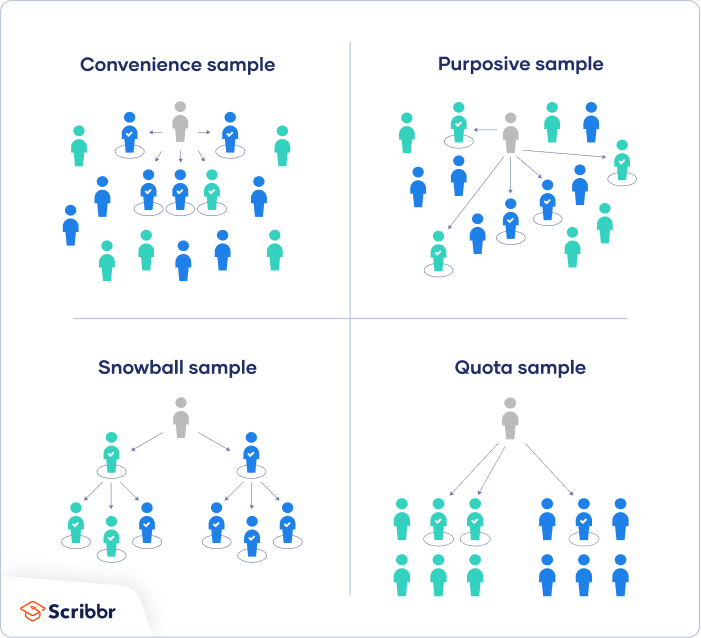

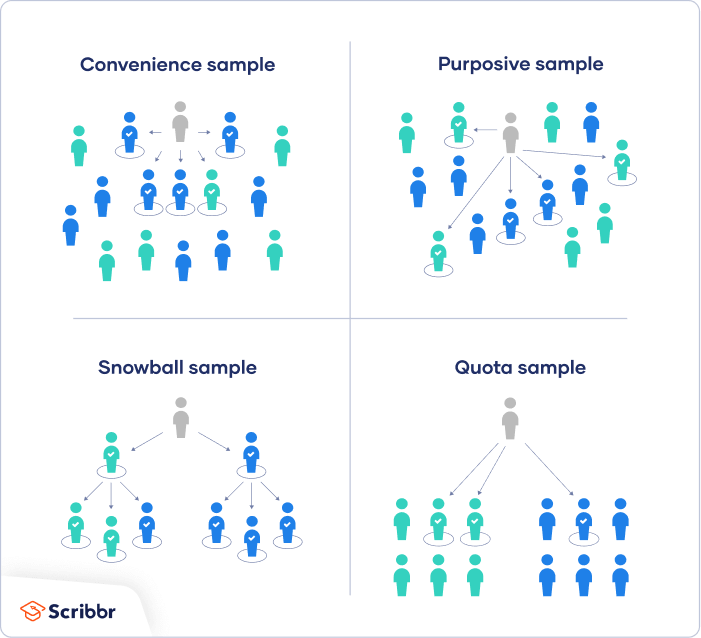

In a non-probability sample, individuals are selected based on non-random criteria, and not every individual has a chance of being included.

This type of sample is easier and cheaper to access, but it has a higher risk of sampling bias . That means the inferences you can make about the population are weaker than with probability samples, and your conclusions may be more limited. If you use a non-probability sample, you should still aim to make it as representative of the population as possible.

Non-probability sampling techniques are often used in exploratory and qualitative research . In these types of research, the aim is not to test a hypothesis about a broad population, but to develop an initial understanding of a small or under-researched population.

1. Convenience sampling

A convenience sample simply includes the individuals who happen to be most accessible to the researcher.

This is an easy and inexpensive way to gather initial data, but there is no way to tell if the sample is representative of the population, so it can’t produce generalizable results. Convenience samples are at risk for both sampling bias and selection bias .

2. Voluntary response sampling

Similar to a convenience sample, a voluntary response sample is mainly based on ease of access. Instead of the researcher choosing participants and directly contacting them, people volunteer themselves (e.g. by responding to a public online survey).

Voluntary response samples are always at least somewhat biased , as some people will inherently be more likely to volunteer than others, leading to self-selection bias .

3. Purposive sampling

This type of sampling, also known as judgement sampling, involves the researcher using their expertise to select a sample that is most useful to the purposes of the research.

It is often used in qualitative research , where the researcher wants to gain detailed knowledge about a specific phenomenon rather than make statistical inferences, or where the population is very small and specific. An effective purposive sample must have clear criteria and rationale for inclusion. Always make sure to describe your inclusion and exclusion criteria and beware of observer bias affecting your arguments.

4. Snowball sampling

If the population is hard to access, snowball sampling can be used to recruit participants via other participants. The number of people you have access to “snowballs” as you get in contact with more people. The downside here is also representativeness, as you have no way of knowing how representative your sample is due to the reliance on participants recruiting others. This can lead to sampling bias .

5. Quota sampling

Quota sampling relies on the non-random selection of a predetermined number or proportion of units. This is called a quota.

You first divide the population into mutually exclusive subgroups (called strata) and then recruit sample units until you reach your quota. These units share specific characteristics, determined by you prior to forming your strata. The aim of quota sampling is to control what or who makes up your sample.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population . Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research. For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

In statistics, sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population.

Samples are used to make inferences about populations . Samples are easier to collect data from because they are practical, cost-effective, convenient, and manageable.

Probability sampling means that every member of the target population has a known chance of being included in the sample.

Probability sampling methods include simple random sampling , systematic sampling , stratified sampling , and cluster sampling .

In non-probability sampling , the sample is selected based on non-random criteria, and not every member of the population has a chance of being included.

Common non-probability sampling methods include convenience sampling , voluntary response sampling, purposive sampling , snowball sampling, and quota sampling .

In multistage sampling , or multistage cluster sampling, you draw a sample from a population using smaller and smaller groups at each stage.

This method is often used to collect data from a large, geographically spread group of people in national surveys, for example. You take advantage of hierarchical groupings (e.g., from state to city to neighborhood) to create a sample that’s less expensive and time-consuming to collect data from.

Sampling bias occurs when some members of a population are systematically more likely to be selected in a sample than others.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, June 22). Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 6, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/sampling-methods/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, population vs. sample | definitions, differences & examples, simple random sampling | definition, steps & examples, sampling bias and how to avoid it | types & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Sampling Methods & Strategies 101

Everything you need to know (including examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Kerryn Warren (PhD) | January 2023

If you’re new to research, sooner or later you’re bound to wander into the intimidating world of sampling methods and strategies. If you find yourself on this page, chances are you’re feeling a little overwhelmed or confused. Fear not – in this post we’ll unpack sampling in straightforward language , along with loads of examples .

Overview: Sampling Methods & Strategies

- What is sampling in a research context?

- The two overarching approaches

Simple random sampling

Stratified random sampling, cluster sampling, systematic sampling, purposive sampling, convenience sampling, snowball sampling.

- How to choose the right sampling method

What (exactly) is sampling?

At the simplest level, sampling (within a research context) is the process of selecting a subset of participants from a larger group . For example, if your research involved assessing US consumers’ perceptions about a particular brand of laundry detergent, you wouldn’t be able to collect data from every single person that uses laundry detergent (good luck with that!) – but you could potentially collect data from a smaller subset of this group.

In technical terms, the larger group is referred to as the population , and the subset (the group you’ll actually engage with in your research) is called the sample . Put another way, you can look at the population as a full cake and the sample as a single slice of that cake. In an ideal world, you’d want your sample to be perfectly representative of the population, as that would allow you to generalise your findings to the entire population. In other words, you’d want to cut a perfect cross-sectional slice of cake, such that the slice reflects every layer of the cake in perfect proportion.

Achieving a truly representative sample is, unfortunately, a little trickier than slicing a cake, as there are many practical challenges and obstacles to achieving this in a real-world setting. Thankfully though, you don’t always need to have a perfectly representative sample – it all depends on the specific research aims of each study – so don’t stress yourself out about that just yet!

With the concept of sampling broadly defined, let’s look at the different approaches to sampling to get a better understanding of what it all looks like in practice.

The two overarching sampling approaches

At the highest level, there are two approaches to sampling: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . Within each of these, there are a variety of sampling methods , which we’ll explore a little later.

Probability sampling involves selecting participants (or any unit of interest) on a statistically random basis , which is why it’s also called “random sampling”. In other words, the selection of each individual participant is based on a pre-determined process (not the discretion of the researcher). As a result, this approach achieves a random sample.

Probability-based sampling methods are most commonly used in quantitative research , especially when it’s important to achieve a representative sample that allows the researcher to generalise their findings.

Non-probability sampling , on the other hand, refers to sampling methods in which the selection of participants is not statistically random . In other words, the selection of individual participants is based on the discretion and judgment of the researcher, rather than on a pre-determined process.

Non-probability sampling methods are commonly used in qualitative research , where the richness and depth of the data are more important than the generalisability of the findings.

If that all sounds a little too conceptual and fluffy, don’t worry. Let’s take a look at some actual sampling methods to make it more tangible.

Need a helping hand?

Probability-based sampling methods

First, we’ll look at four common probability-based (random) sampling methods:

Importantly, this is not a comprehensive list of all the probability sampling methods – these are just four of the most common ones. So, if you’re interested in adopting a probability-based sampling approach, be sure to explore all the options.

Simple random sampling involves selecting participants in a completely random fashion , where each participant has an equal chance of being selected. Basically, this sampling method is the equivalent of pulling names out of a hat , except that you can do it digitally. For example, if you had a list of 500 people, you could use a random number generator to draw a list of 50 numbers (each number, reflecting a participant) and then use that dataset as your sample.

Thanks to its simplicity, simple random sampling is easy to implement , and as a consequence, is typically quite cheap and efficient . Given that the selection process is completely random, the results can be generalised fairly reliably. However, this also means it can hide the impact of large subgroups within the data, which can result in minority subgroups having little representation in the results – if any at all. To address this, one needs to take a slightly different approach, which we’ll look at next.

Stratified random sampling is similar to simple random sampling, but it kicks things up a notch. As the name suggests, stratified sampling involves selecting participants randomly , but from within certain pre-defined subgroups (i.e., strata) that share a common trait . For example, you might divide the population into strata based on gender, ethnicity, age range or level of education, and then select randomly from each group.

The benefit of this sampling method is that it gives you more control over the impact of large subgroups (strata) within the population. For example, if a population comprises 80% males and 20% females, you may want to “balance” this skew out by selecting a random sample from an equal number of males and females. This would, of course, reduce the representativeness of the sample, but it would allow you to identify differences between subgroups. So, depending on your research aims, the stratified approach could work well.

Next on the list is cluster sampling. As the name suggests, this sampling method involves sampling from naturally occurring, mutually exclusive clusters within a population – for example, area codes within a city or cities within a country. Once the clusters are defined, a set of clusters are randomly selected and then a set of participants are randomly selected from each cluster.

Now, you’re probably wondering, “how is cluster sampling different from stratified random sampling?”. Well, let’s look at the previous example where each cluster reflects an area code in a given city.

With cluster sampling, you would collect data from clusters of participants in a handful of area codes (let’s say 5 neighbourhoods). Conversely, with stratified random sampling, you would need to collect data from all over the city (i.e., many more neighbourhoods). You’d still achieve the same sample size either way (let’s say 200 people, for example), but with stratified sampling, you’d need to do a lot more running around, as participants would be scattered across a vast geographic area. As a result, cluster sampling is often the more practical and economical option.

If that all sounds a little mind-bending, you can use the following general rule of thumb. If a population is relatively homogeneous , cluster sampling will often be adequate. Conversely, if a population is quite heterogeneous (i.e., diverse), stratified sampling will generally be more appropriate.

The last probability sampling method we’ll look at is systematic sampling. This method simply involves selecting participants at a set interval , starting from a random point .

For example, if you have a list of students that reflects the population of a university, you could systematically sample that population by selecting participants at an interval of 8 . In other words, you would randomly select a starting point – let’s say student number 40 – followed by student 48, 56, 64, etc.

What’s important with systematic sampling is that the population list you select from needs to be randomly ordered . If there are underlying patterns in the list (for example, if the list is ordered by gender, IQ, age, etc.), this will result in a non-random sample, which would defeat the purpose of adopting this sampling method. Of course, you could safeguard against this by “shuffling” your population list using a random number generator or similar tool.

Non-probability-based sampling methods

Right, now that we’ve looked at a few probability-based sampling methods, let’s look at three non-probability methods :

Again, this is not an exhaustive list of all possible sampling methods, so be sure to explore further if you’re interested in adopting a non-probability sampling approach.

First up, we’ve got purposive sampling – also known as judgment , selective or subjective sampling. Again, the name provides some clues, as this method involves the researcher selecting participants using his or her own judgement , based on the purpose of the study (i.e., the research aims).

For example, suppose your research aims were to understand the perceptions of hyper-loyal customers of a particular retail store. In that case, you could use your judgement to engage with frequent shoppers, as well as rare or occasional shoppers, to understand what judgements drive the two behavioural extremes .

Purposive sampling is often used in studies where the aim is to gather information from a small population (especially rare or hard-to-find populations), as it allows the researcher to target specific individuals who have unique knowledge or experience . Naturally, this sampling method is quite prone to researcher bias and judgement error, and it’s unlikely to produce generalisable results, so it’s best suited to studies where the aim is to go deep rather than broad .

Next up, we have convenience sampling. As the name suggests, with this method, participants are selected based on their availability or accessibility . In other words, the sample is selected based on how convenient it is for the researcher to access it, as opposed to using a defined and objective process.

Naturally, convenience sampling provides a quick and easy way to gather data, as the sample is selected based on the individuals who are readily available or willing to participate. This makes it an attractive option if you’re particularly tight on resources and/or time. However, as you’d expect, this sampling method is unlikely to produce a representative sample and will of course be vulnerable to researcher bias , so it’s important to approach it with caution.

Last but not least, we have the snowball sampling method. This method relies on referrals from initial participants to recruit additional participants. In other words, the initial subjects form the first (small) snowball and each additional subject recruited through referral is added to the snowball, making it larger as it rolls along .

Snowball sampling is often used in research contexts where it’s difficult to identify and access a particular population. For example, people with a rare medical condition or members of an exclusive group. It can also be useful in cases where the research topic is sensitive or taboo and people are unlikely to open up unless they’re referred by someone they trust.

Simply put, snowball sampling is ideal for research that involves reaching hard-to-access populations . But, keep in mind that, once again, it’s a sampling method that’s highly prone to researcher bias and is unlikely to produce a representative sample. So, make sure that it aligns with your research aims and questions before adopting this method.

How to choose a sampling method

Now that we’ve looked at a few popular sampling methods (both probability and non-probability based), the obvious question is, “ how do I choose the right sampling method for my study?”. When selecting a sampling method for your research project, you’ll need to consider two important factors: your research aims and your resources .

As with all research design and methodology choices, your sampling approach needs to be guided by and aligned with your research aims, objectives and research questions – in other words, your golden thread. Specifically, you need to consider whether your research aims are primarily concerned with producing generalisable findings (in which case, you’ll likely opt for a probability-based sampling method) or with achieving rich , deep insights (in which case, a non-probability-based approach could be more practical). Typically, quantitative studies lean toward the former, while qualitative studies aim for the latter, so be sure to consider your broader methodology as well.

The second factor you need to consider is your resources and, more generally, the practical constraints at play. If, for example, you have easy, free access to a large sample at your workplace or university and a healthy budget to help you attract participants, that will open up multiple options in terms of sampling methods. Conversely, if you’re cash-strapped, short on time and don’t have unfettered access to your population of interest, you may be restricted to convenience or referral-based methods.

In short, be ready for trade-offs – you won’t always be able to utilise the “perfect” sampling method for your study, and that’s okay. Much like all the other methodological choices you’ll make as part of your study, you’ll often need to compromise and accept practical trade-offs when it comes to sampling. Don’t let this get you down though – as long as your sampling choice is well explained and justified, and the limitations of your approach are clearly articulated, you’ll be on the right track.

Let’s recap…

In this post, we’ve covered the basics of sampling within the context of a typical research project.

- Sampling refers to the process of defining a subgroup (sample) from the larger group of interest (population).

- The two overarching approaches to sampling are probability sampling (random) and non-probability sampling .

- Common probability-based sampling methods include simple random sampling, stratified random sampling, cluster sampling and systematic sampling.

- Common non-probability-based sampling methods include purposive sampling, convenience sampling and snowball sampling.

- When choosing a sampling method, you need to consider your research aims , objectives and questions, as well as your resources and other practical constraints .

If you’d like to see an example of a sampling strategy in action, be sure to check out our research methodology chapter sample .

Last but not least, if you need hands-on help with your sampling (or any other aspect of your research), take a look at our 1-on-1 coaching service , where we guide you through each step of the research process, at your own pace.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

Excellent and helpful. Best site to get a full understanding of Research methodology. I’m nolonger as “clueless “..😉

Excellent and helpful for junior researcher!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Sampling Techniques for Quantitative Research

- First Online: 27 October 2022

Cite this chapter

- Moniruzzaman Sarker ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3595-5838 4 &

- Mohammed Abdulmalek AL-Muaalemi 5

3014 Accesses

8 Citations

In quantitative research, collecting data from an entire population of a study is impractical in many instances. It squanders resources like time and money which can be minimized by choosing suitable sampling techniques between probability and non-probability methods. The chapter outlines a brief idea about the different categories of sampling techniques with examples. Sensibly selecting among the sampling techniques allows the researcher to generalize the findings to a specific study context. Although probability sampling is more appealing to draw a representative sample, non-probability sampling techniques also enable the researcher to generalize the findings upon implementing the sampling strategy wisely. Moreover, adopting probability sampling techniques is not feasible in many situations. The chapter suggests selecting sampling techniques should be guided by research objectives, study scope, and availability of sampling frame rather than looking at the nature of sampling techniques.

- Sampling techniques

- Quantitative study

- Probability sampling

- Non-probability sampling

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2015). Business research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Clottey, T. A., & Grawe, S. J. (2014). Non-response bias assessment in logistics survey research: Use fewer tests? International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 44 (5), 412–426. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-10-2012-0314

Article Google Scholar

Collier, J. E., & Bienstock, C. C. (2007). An analysis of how nonresponse error is assessed in academic marketing research. Marketing Theory, 7 (2), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593107076865

Cooper, D. R., Schindler, P. S., & Sun, J. (2006). Business research methods (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Incorporated.

Feild, L., Pruchno, R. A., Bewley, J., Lemay, E. P., & Levinsky, N. G. (2006). Using probability versus nonprobability sampling to identify hard-to-access participants for health-related research: Costs and contrasts. Journal of Aging and Health, 18 (4), 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264306291420.

Hulland, J., Baumgartner, H., & Smith, K. M. (2017). Marketing survey research best practices: Evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 92–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0532-y

Lindner, J. R., Murphy, T. H., & Briers, G. E. (2001). Handling nonresponse in social science research. Journal of Agricultural Education, 42 (4), 43–53.

Malhotra, N. K., & Das, S. (2010). Marketing research: An applied orientation (6th ed.). Pearson Education.

Book Google Scholar

Marshall, M. N. (1996). Sampling for qualitative research. Family Practice, 13 (6), 522–526. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/13.6.522

Memon, M. A., Ting, H., Ramayah, T., Chuah, F., & Cheah, J.-H. (2017). A review of the methodological misconceptions and guidelines related to the application of structural equation modeling: A Malaysian scenario. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 1 (1), i–xiii.

Rowley, J. (2014). Designing and using research questionnaires. Management Research Review, 37 (3), 308–330. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-02-2013-0027

Sarstedt, M., Bengart, P., Shaltoni, A. M., & Lehmann, S. (2018). The use of sampling methods in advertising research: A gap between theory and practice. International Journal of Advertising, 37 (4), 650–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1348329

Sax, L. J., Gilmartin, S. K., & Bryant, A. N. (2003). Assessing response rates and nonresponse bias in web and paper surveys. Research in Higher Education, 44 (4), 409–432. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024232915870

Seddon, P. B., & Scheepers, R. (2012). Towards the improved treatment of generalization of knowledge claims in IS research: Drawing general conclusions from samples. European Journal of Information Systems, 21 (1), 6–21.

Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill building approach (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Zikmund, W. G., Babin, B. J., Carr, J. C., & Griffin, M. (2013). Business research methods (9th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Assistant Professor of Marketing, Southamton Malysia Business School, University of Southamton Malysia, Johor Bahru, Malaysia

Moniruzzaman Sarker

Faculty of Business and Accountancy, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Mohammed Abdulmalek AL-Muaalemi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Moniruzzaman Sarker .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Centre for Family and Child Studies, Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

M. Rezaul Islam

Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Niaz Ahmed Khan

Department of Social Work, School of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Rajendra Baikady

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Moniruzzaman Sarker, AL-Muaalemi, M.A. (2022). Sampling Techniques for Quantitative Research. In: Islam, M.R., Khan, N.A., Baikady, R. (eds) Principles of Social Research Methodology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5441-2_15

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5441-2_15

Published : 27 October 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-19-5219-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-19-5441-2

eBook Packages : Social Sciences

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3.4 Sampling Techniques in Quantitative Research

Target population.

The target population includes the people the researcher is interested in conducting the research and generalizing the findings on. 40 For example, if certain researchers are interested in vaccine-preventable diseases in children five years and younger in Australia. The target population will be all children aged 0–5 years residing in Australia. The actual population is a subset of the target population from which the sample is drawn, e.g. children aged 0–5 years living in the capital cities in Australia. The sample is the people chosen for the study from the actual population (Figure 3.9). The sampling process involves choosing people, and it is distinct from the sample. 40 In quantitative research, the sample must accurately reflect the target population, be free from bias in terms of selection, and be large enough to validate or reject the study hypothesis with statistical confidence and minimise random error. 2

Sampling techniques

Sampling in quantitative research is a critical component that involves selecting a representative subset of individuals or cases from a larger population and often employs sampling techniques based on probability theory. 41 The goal of sampling is to obtain a sample that is large enough and representative of the target population. Examples of probability sampling techniques include simple random sampling, stratified random sampling, systematic random sampling and cluster sampling ( shown below ). 2 The key feature of probability techniques is that they involve randomization. There are two main characteristics of probability sampling. All individuals of a population are accessible to the researcher (theoretically), and there is an equal chance that each person in the population will be chosen to be part of the study sample. 41 While quantitative research often uses sampling techniques based on probability theory, some non-probability techniques may occasionally be utilised in healthcare research. 42 Non-probability sampling methods are commonly used in qualitative research. These include purposive, convenience, theoretical and snowballing and have been discussed in detail in chapter 4.

Sample size calculation

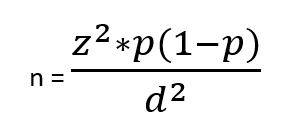

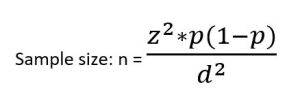

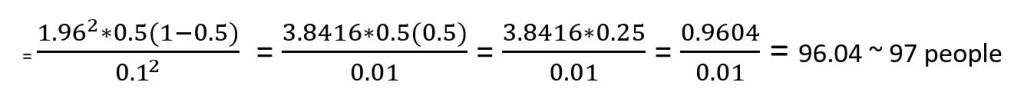

In order to enable comparisons with some level of established statistical confidence, quantitative research needs an acceptable sample size. 2 The sample size is the most crucial factor for reliability (reproducibility) in quantitative research. It is important for a study to be powered – the likelihood of identifying a difference if it exists in reality. 2 Small sample-sized studies are more likely to be underpowered, and results from small samples are more likely to be prone to random error. 2 The formula for sample size calculation varies with the study design and the research hypothesis. 2 There are numerous formulae for sample size calculations, but such details are beyond the scope of this book. For further readings, please consult the biostatistics textbook by Hirsch RP, 2021. 43 However, we will introduce a simple formula for calculating sample size for cross-sectional studies with prevalence as the outcome. 2

z is the statistical confidence; therefore, z = 1.96 translates to 95% confidence; z = 1.68 translates to 90% confidence

p = Expected prevalence (of health condition of interest)

d = Describes intended precision; d = 0.1 means that the estimate falls +/-10 percentage points of true prevalence with the considered confidence. (e.g. for a prevalence of 40% (0.4), if d=.1, then the estimate will fall between 30% and 50% (0.3 to 0.5).

Example: A district medical officer seeks to estimate the proportion of children in the district receiving appropriate childhood vaccinations. Assuming a simple random sample of a community is to be selected, how many children must be studied if the resulting estimate is to fall within 10% of the true proportion with 95% confidence? It is expected that approximately 50% of the children receive vaccinations

z = 1.96 (95% confidence)

d = 10% = 10/ 100 = 0.1 (estimate to fall within 10%)

p = 50% = 50/ 100 = 0.5

Now we can enter the values into the formula

Given that people cannot be reported in decimal points, it is important to round up to the nearest whole number.

An Introduction to Research Methods for Undergraduate Health Profession Students Copyright © 2023 by Faith Alele and Bunmi Malau-Aduli is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques, & Examples

Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques, & Examples

Published on 3 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

When you conduct research about a group of people, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every person in that group. Instead, you select a sample. The sample is the group of individuals who will actually participate in the research.

To draw valid conclusions from your results, you have to carefully decide how you will select a sample that is representative of the group as a whole. There are two types of sampling methods:

- Probability sampling involves random selection, allowing you to make strong statistical inferences about the whole group. It minimises the risk of selection bias .

- Non-probability sampling involves non-random selection based on convenience or other criteria, allowing you to easily collect data.

You should clearly explain how you selected your sample in the methodology section of your paper or thesis.

Table of contents

Population vs sample, probability sampling methods, non-probability sampling methods, frequently asked questions about sampling.

First, you need to understand the difference between a population and a sample , and identify the target population of your research.

- The population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about.

- The sample is the specific group of individuals that you will collect data from.

The population can be defined in terms of geographical location, age, income, and many other characteristics.

It is important to carefully define your target population according to the purpose and practicalities of your project.

If the population is very large, demographically mixed, and geographically dispersed, it might be difficult to gain access to a representative sample.

Sampling frame

The sampling frame is the actual list of individuals that the sample will be drawn from. Ideally, it should include the entire target population (and nobody who is not part of that population).

You are doing research on working conditions at Company X. Your population is all 1,000 employees of the company. Your sampling frame is the company’s HR database, which lists the names and contact details of every employee.

Sample size

The number of individuals you should include in your sample depends on various factors, including the size and variability of the population and your research design. There are different sample size calculators and formulas depending on what you want to achieve with statistical analysis .

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Probability sampling means that every member of the population has a chance of being selected. It is mainly used in quantitative research . If you want to produce results that are representative of the whole population, probability sampling techniques are the most valid choice.

There are four main types of probability sample.

1. Simple random sampling

In a simple random sample , every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. Your sampling frame should include the whole population.

To conduct this type of sampling, you can use tools like random number generators or other techniques that are based entirely on chance.

You want to select a simple random sample of 100 employees of Company X. You assign a number to every employee in the company database from 1 to 1000, and use a random number generator to select 100 numbers.

2. Systematic sampling

Systematic sampling is similar to simple random sampling, but it is usually slightly easier to conduct. Every member of the population is listed with a number, but instead of randomly generating numbers, individuals are chosen at regular intervals.

All employees of the company are listed in alphabetical order. From the first 10 numbers, you randomly select a starting point: number 6. From number 6 onwards, every 10th person on the list is selected (6, 16, 26, 36, and so on), and you end up with a sample of 100 people.

If you use this technique, it is important to make sure that there is no hidden pattern in the list that might skew the sample. For example, if the HR database groups employees by team, and team members are listed in order of seniority, there is a risk that your interval might skip over people in junior roles, resulting in a sample that is skewed towards senior employees.

3. Stratified sampling

Stratified sampling involves dividing the population into subpopulations that may differ in important ways. It allows you draw more precise conclusions by ensuring that every subgroup is properly represented in the sample.

To use this sampling method, you divide the population into subgroups (called strata) based on the relevant characteristic (e.g., gender, age range, income bracket, job role).

Based on the overall proportions of the population, you calculate how many people should be sampled from each subgroup. Then you use random or systematic sampling to select a sample from each subgroup.

The company has 800 female employees and 200 male employees. You want to ensure that the sample reflects the gender balance of the company, so you sort the population into two strata based on gender. Then you use random sampling on each group, selecting 80 women and 20 men, which gives you a representative sample of 100 people.

4. Cluster sampling

Cluster sampling also involves dividing the population into subgroups, but each subgroup should have similar characteristics to the whole sample. Instead of sampling individuals from each subgroup, you randomly select entire subgroups.

If it is practically possible, you might include every individual from each sampled cluster. If the clusters themselves are large, you can also sample individuals from within each cluster using one of the techniques above. This is called multistage sampling .

This method is good for dealing with large and dispersed populations, but there is more risk of error in the sample, as there could be substantial differences between clusters. It’s difficult to guarantee that the sampled clusters are really representative of the whole population.

The company has offices in 10 cities across the country (all with roughly the same number of employees in similar roles). You don’t have the capacity to travel to every office to collect your data, so you use random sampling to select 3 offices – these are your clusters.

In a non-probability sample , individuals are selected based on non-random criteria, and not every individual has a chance of being included.

This type of sample is easier and cheaper to access, but it has a higher risk of sampling bias . That means the inferences you can make about the population are weaker than with probability samples, and your conclusions may be more limited. If you use a non-probability sample, you should still aim to make it as representative of the population as possible.

Non-probability sampling techniques are often used in exploratory and qualitative research . In these types of research, the aim is not to test a hypothesis about a broad population, but to develop an initial understanding of a small or under-researched population.

1. Convenience sampling

A convenience sample simply includes the individuals who happen to be most accessible to the researcher.

This is an easy and inexpensive way to gather initial data, but there is no way to tell if the sample is representative of the population, so it can’t produce generalisable results.

You are researching opinions about student support services in your university, so after each of your classes, you ask your fellow students to complete a survey on the topic. This is a convenient way to gather data, but as you only surveyed students taking the same classes as you at the same level, the sample is not representative of all the students at your university.

2. Voluntary response sampling

Similar to a convenience sample, a voluntary response sample is mainly based on ease of access. Instead of the researcher choosing participants and directly contacting them, people volunteer themselves (e.g., by responding to a public online survey).

Voluntary response samples are always at least somewhat biased, as some people will inherently be more likely to volunteer than others.

You send out the survey to all students at your university and many students decide to complete it. This can certainly give you some insight into the topic, but the people who responded are more likely to be those who have strong opinions about the student support services, so you can’t be sure that their opinions are representative of all students.

3. Purposive sampling

Purposive sampling , also known as judgement sampling, involves the researcher using their expertise to select a sample that is most useful to the purposes of the research.

It is often used in qualitative research , where the researcher wants to gain detailed knowledge about a specific phenomenon rather than make statistical inferences, or where the population is very small and specific. An effective purposive sample must have clear criteria and rationale for inclusion.

You want to know more about the opinions and experiences of students with a disability at your university, so you purposely select a number of students with different support needs in order to gather a varied range of data on their experiences with student services.

4. Snowball sampling

If the population is hard to access, snowball sampling can be used to recruit participants via other participants. The number of people you have access to ‘snowballs’ as you get in contact with more people.

You are researching experiences of homelessness in your city. Since there is no list of all homeless people in the city, probability sampling isn’t possible. You meet one person who agrees to participate in the research, and she puts you in contact with other homeless people she knows in the area.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Samples are used to make inferences about populations . Samples are easier to collect data from because they are practical, cost-effective, convenient, and manageable.

Probability sampling means that every member of the target population has a known chance of being included in the sample.

Probability sampling methods include simple random sampling , systematic sampling , stratified sampling , and cluster sampling .

In non-probability sampling , the sample is selected based on non-random criteria, and not every member of the population has a chance of being included.

Common non-probability sampling methods include convenience sampling , voluntary response sampling, purposive sampling , snowball sampling , and quota sampling .

Sampling bias occurs when some members of a population are systematically more likely to be selected in a sample than others.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/sampling/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is quantitative research | definition & methods, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, controlled experiments | methods & examples of control.

Part I: Sampling, Data Collection, & Analysis in Quantitative Research

In this module, we will focus on how quantitative research collects and analyzes data, as well as methods for obtaining sample population.

- Levels of Measurement

- Reliability and Validity

- Population and Samples

- Common Data Collection Methods

- Data Analysis

- Statistical Significance versus Clinical Significance

Objectives:

- Describe levels of measurement

- Describe reliability and validity as applied to critical appraisal of research

- Differentiate methods of obtaining samples for population generalizability

- Describe common data collection methods in quantitative research

- Describe various data analysis methods in quantitative research

- Differentiate statistical significance versus clinical significance

Levels of measurement

Once researchers have collected their data (we will talk about data collection later in this module), they need methods to organize the data before they even start to think about statistical analyses. Statistical operations depend on a variable’s level of measurement. Think about this similarly to shuffling all of your bills in some type of organization before you pay them. With levels of measurement, we are precisely recording variables in a method to help organize them.

There are four levels of measurement:

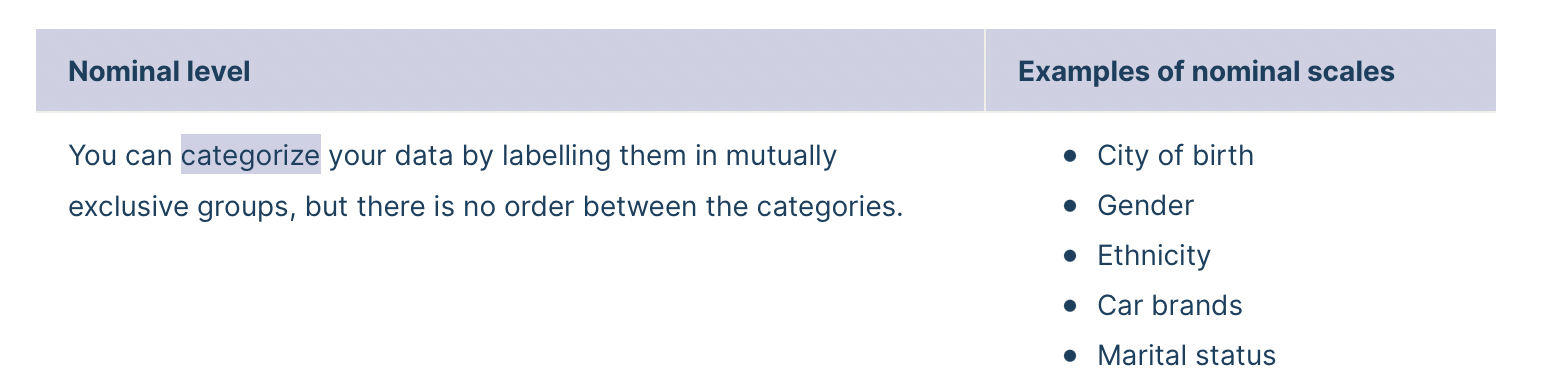

Nominal: The data can only be categorized

Ordinal: The data can be categorized and ranked

Interval: The data can be categorized, ranked, and evenly spaced

Ratio: The data can be categorized, ranked, even spaced, and has a natural zero

Going from lowest to highest, the 4 levels of measurement are cumulative. This means that they each take on the properties of lower levels and add new properties.

- A variable is nominal if the values could be interchanged (e.g. 1 = male, 2 = female OR 1 = female, 2 = male).

- A variable is ordinal if there is a quantitative ordering of values AND if there are a small number of values (e.g. excellent, good, fair, poor).

- A variable is usually considered interval if it is measured with a composite scale or test.

- A variable is ratio level if it makes sense to say that one value is twice as much as another (e.g. 100 mg is twice as much as 50 mg) (Polit & Beck, 2021).

Reliability and Validity as Applied to Critical Appraisal of Research

Reliability measures the ability of a measure to consistently measure the same way. Validity measures what it is supposed to measure. Do we have the need for both in research? Yes! If a variable is measured inaccurately, the data is useless. Let’s talk about why.

For example, let’s set out to measure blood glucose for our study. The validity is how well the measure can determine the blood glucose. If we used a blood pressure cuff to measure blood glucose, this would not be a valid measure. If we used a blood glucose meter, it would be a more valid measure. It does not stop there, however. What about the meter itself? Has it been calibrated? Are the correct sticks for the meter available? Are they expired? Does the meter have fresh batteries? Are the patient’s hands clean?

Reliability wants to know: Is the blood glucose meter measuring the same way, every time?

Validity is asking, “Does the meter measure what it is supposed to measure?” Construct validity: Does the test measure the concept that it’s intended to measure? Content validity: Is the test fully representative of what it aims to measure? Face validity: Does the content of the test appear to be suitable to its aims?

Leibold, 2020

Obtaining Samples for Population Generalizability

In quantitative research, a population is the entire group that the researcher wants to draw conclusions about.

A sample is the specific group that the researcher will actually collect data from. A sample is always a much smaller group of people than the total size of the population. For example, if we wanted to investigate heart failure, there would be no possible way to measure every single human with heart failure. Therefore, researchers will attempt to select a sample of that large population which would most likely reflect (AKA: be a representative sample) the larger population of those with heart failure. Remember, in quantitative research, the results should be generalizable to the population studied.

A researcher will specify population characteristics through eligibility criteria. This means that they consider which characteristics to include ( inclusion criteria ) and which characteristics to exclude ( exclusion criteria ).

For example, if we were studying chemotherapy in breast cancer subjects, we might specify:

- Inclusion Criteria: Postmenopausal women between the ages of 45 and 75 who have been diagnosed with Stage II breast cancer.

- Exclusion Criteria: Abnormal renal function tests since we are studying a combination of drugs that may be nephrotoxic. Renal function tests are to be performed to evaluate renal function and the threshold values that would disqualify the prospective subject is serum creatinine above 1.9 mg/dl.

Sampling Designs:

There are two broad classes of sampling in quantitative research: Probability and nonprobability sampling.

Probability sampling : As the name implies, probability sampling means that each eligible individual has a random chance (same probability) of being selected to participate in the study.

There are three types of probability sampling:

Simple random sampling : Every eligible participant is randomly selected (e.g. drawing from a hat).

Stratified random sampling : Eligible population is first divided into two or more strata (categories) from which randomization occurs (e.g. pollution levels selected from restaurants, bars with ordinances of state laws, and bars with no ordinances).

Systematic sampling : Involves the selection of every __ th eligible participant from a list (e.g. every 9 th person).

Nonprobability sampling : In nonprobability sampling, eligible participants are selected using a subjective (non-random) method.

There are four types of nonprobability sampling:

Convenience sampling : Participants are selected for inclusion in the sample because they are the easiest for the researcher to access. This can be due to geographical proximity, availability at a given time, or willingness to participate in the research.

Quota sampling : Participants are from a very tailored sample that’s in proportion to some characteristic or trait of a population. For example, the researcher could divide a population by the state they live in, income or education level, or sex. The population is divided into groups (also called strata) and samples are taken from each group to meet a quota.

Consecutive sampling : A sampling technique in which every subject meeting the criteria of inclusion is selected until the required sample size is achieved. Consecutive sampling is defined as a nonprobability technique where samples are picked at the ease of a researcher more like convenience sampling, only with a slight variation. Here, the researcher selects a sample or group of people, conducts research over a period, collects results, and then moves on to another sample.

Purposive sampling : A group of non-probability sampling techniques in which units are selected because they have characteristics that the researcher needs in their sample. In other words, units are selected “on purpose” in purposive sampling.

Common Data Collection Methods in Quantitative Research

There are various methods that researchers use to collect data for their studies. For nurse researchers, existing records are an important data source. Researchers need to decide if they will collect new data or use existing data. There is also a wealth of clinical data that can be used for non-research purposed to help answer clinical questions.

Let’s look at some general data collection methods and data sources in quantitative research.

Existing data could include medical records, school records, corporate diaries, letters, meeting minutes, and photographs. These are easy to obtain do not require participation from those being studied.

Collecting new data:

Let’s go over a few methods in which researcher can collect new data. These usually requires participation from those being studied.

Self-reports can be obtained via interviews or questionnaires . Closed-ended questions can be asked (“Within the past 6 months, were you ever a member of a fitness gym?” Yes/No) or open-ended questions such as “Why did you decide to join a fitness gym?” Important to remember (this sometimes throws students off) is that conducting interviews and questionnaires does not mean it is qualitative in nature! Do not let that throw you off in assessing whether a published article is quantitative or qualitative. The nature of the questions, however, may help to determine the type of research (quantitative or qualitative), as qualitative questions deal with ascertaining a very organic collection of people’s experiences in open-ended questions.

Advantages of questionnaires (compared to interviews):

- Questionnaires are less costly and are advantageous for geographically dispersed samples.

- Questionnaires offer the possibility of anonymity, which may be crucial in obtaining information about certain opinions or traits.

Advances of interviews (compared to questionnaires):

- Higher response rates

- Some people cannot fill out a questionnaire.

- Opportunities to clarify questions or to determine comprehension

- Opportunity to collect supplementary data through observation

Psychosocial scales are often utilized within questionnaires or interviews. These can help to obtain attitudes, perceptions, and psychological traits.

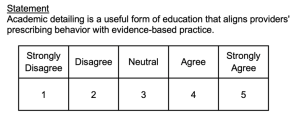

Likert Scales :

- Consist of several declarative statements ( items ) expressing viewpoints

- Responses are on an agree/disagree continuum (usually five or seven response options).

- Responses to items are summed to compute a total scale score.

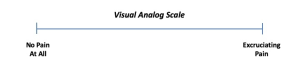

Visual Analog Scale:

- Used to measure subjective experiences (e.g., pain, nausea)

- Measurements are on a straight line measuring 100 mm.

- End points labeled as extreme limits of sensation

Observational Methods include the observation method of data collection involves seeing people in a certain setting or place at a specific time and day. Essentially, researchers study the behavior of the individuals or surroundings in which they are analyzing. This can be controlled, spontaneous, or participant-based research .

When a researcher utilizes a defined procedure for observing individuals or the environment, this is known as structured observation. When individuals are observed in their natural environment, this is known as naturalistic observation. In participant observation, the researcher immerses himself or herself in the environment and becomes a member of the group being observed.

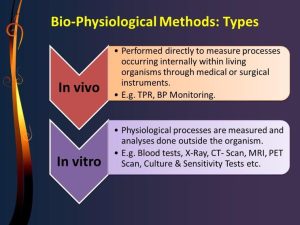

Biophysiologic Measures are defined as ‘those physiological and physical variables that require specialized technical instruments and equipment for their measurement’. Biophysiological measures are the most common instruments for collecting data in medical science studies. To collect valid and reliable data, it is critical to apply these measures appropriately.

- In vivo refers to when research or work is done with or within an entire, living organism. Examples can include studies in animal models or human clinical trials.

- In vitro is used to describe work that’s performed outside of a living organism. This usually involves isolated tissues, organs, or cells.

Let’s watch a video about Sampling and Data Collection that I made a couple of years ago.

Home » Sampling Methods – Types, Techniques and Examples

Sampling Methods – Types, Techniques and Examples

Table of Contents

Sampling refers to the process of selecting a subset of data from a larger population or dataset in order to analyze or make inferences about the whole population.

In other words, sampling involves taking a representative sample of data from a larger group or dataset in order to gain insights or draw conclusions about the entire group.

Sampling Methods

Sampling methods refer to the techniques used to select a subset of individuals or units from a larger population for the purpose of conducting statistical analysis or research.

Sampling is an essential part of the Research because it allows researchers to draw conclusions about a population without having to collect data from every member of that population, which can be time-consuming, expensive, or even impossible.

Types of Sampling Methods

Sampling can be broadly categorized into two main categories:

Probability Sampling

This type of sampling is based on the principles of random selection, and it involves selecting samples in a way that every member of the population has an equal chance of being included in the sample.. Probability sampling is commonly used in scientific research and statistical analysis, as it provides a representative sample that can be generalized to the larger population.

Type of Probability Sampling :

- Simple Random Sampling: In this method, every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected for the sample. This can be done using a random number generator or by drawing names out of a hat, for example.

- Systematic Sampling: In this method, the population is first divided into a list or sequence, and then every nth member is selected for the sample. For example, if every 10th person is selected from a list of 100 people, the sample would include 10 people.

- Stratified Sampling: In this method, the population is divided into subgroups or strata based on certain characteristics, and then a random sample is taken from each stratum. This is often used to ensure that the sample is representative of the population as a whole.

- Cluster Sampling: In this method, the population is divided into clusters or groups, and then a random sample of clusters is selected. Then, all members of the selected clusters are included in the sample.

- Multi-Stage Sampling : This method combines two or more sampling techniques. For example, a researcher may use stratified sampling to select clusters, and then use simple random sampling to select members within each cluster.

Non-probability Sampling

This type of sampling does not rely on random selection, and it involves selecting samples in a way that does not give every member of the population an equal chance of being included in the sample. Non-probability sampling is often used in qualitative research, where the aim is not to generalize findings to a larger population, but to gain an in-depth understanding of a particular phenomenon or group. Non-probability sampling methods can be quicker and more cost-effective than probability sampling methods, but they may also be subject to bias and may not be representative of the larger population.

Types of Non-probability Sampling :

- Convenience Sampling: In this method, participants are chosen based on their availability or willingness to participate. This method is easy and convenient but may not be representative of the population.

- Purposive Sampling: In this method, participants are selected based on specific criteria, such as their expertise or knowledge on a particular topic. This method is often used in qualitative research, but may not be representative of the population.

- Snowball Sampling: In this method, participants are recruited through referrals from other participants. This method is often used when the population is hard to reach, but may not be representative of the population.

- Quota Sampling: In this method, a predetermined number of participants are selected based on specific criteria, such as age or gender. This method is often used in market research, but may not be representative of the population.

- Volunteer Sampling: In this method, participants volunteer to participate in the study. This method is often used in research where participants are motivated by personal interest or altruism, but may not be representative of the population.

Applications of Sampling Methods

Applications of Sampling Methods from different fields:

- Psychology : Sampling methods are used in psychology research to study various aspects of human behavior and mental processes. For example, researchers may use stratified sampling to select a sample of participants that is representative of the population based on factors such as age, gender, and ethnicity. Random sampling may also be used to select participants for experimental studies.

- Sociology : Sampling methods are commonly used in sociological research to study social phenomena and relationships between individuals and groups. For example, researchers may use cluster sampling to select a sample of neighborhoods to study the effects of economic inequality on health outcomes. Stratified sampling may also be used to select a sample of participants that is representative of the population based on factors such as income, education, and occupation.

- Social sciences: Sampling methods are commonly used in social sciences to study human behavior and attitudes. For example, researchers may use stratified sampling to select a sample of participants that is representative of the population based on factors such as age, gender, and income.

- Marketing : Sampling methods are used in marketing research to collect data on consumer preferences, behavior, and attitudes. For example, researchers may use random sampling to select a sample of consumers to participate in a survey about a new product.

- Healthcare : Sampling methods are used in healthcare research to study the prevalence of diseases and risk factors, and to evaluate interventions. For example, researchers may use cluster sampling to select a sample of health clinics to participate in a study of the effectiveness of a new treatment.

- Environmental science: Sampling methods are used in environmental science to collect data on environmental variables such as water quality, air pollution, and soil composition. For example, researchers may use systematic sampling to collect soil samples at regular intervals across a field.

- Education : Sampling methods are used in education research to study student learning and achievement. For example, researchers may use stratified sampling to select a sample of schools that is representative of the population based on factors such as demographics and academic performance.

Examples of Sampling Methods

Probability Sampling Methods Examples:

- Simple random sampling Example : A researcher randomly selects participants from the population using a random number generator or drawing names from a hat.

- Stratified random sampling Example : A researcher divides the population into subgroups (strata) based on a characteristic of interest (e.g. age or income) and then randomly selects participants from each subgroup.

- Systematic sampling Example : A researcher selects participants at regular intervals from a list of the population.

Non-probability Sampling Methods Examples:

- Convenience sampling Example: A researcher selects participants who are conveniently available, such as students in a particular class or visitors to a shopping mall.

- Purposive sampling Example : A researcher selects participants who meet specific criteria, such as individuals who have been diagnosed with a particular medical condition.

- Snowball sampling Example : A researcher selects participants who are referred to them by other participants, such as friends or acquaintances.

How to Conduct Sampling Methods

some general steps to conduct sampling methods:

- Define the population: Identify the population of interest and clearly define its boundaries.

- Choose the sampling method: Select an appropriate sampling method based on the research question, characteristics of the population, and available resources.

- Determine the sample size: Determine the desired sample size based on statistical considerations such as margin of error, confidence level, or power analysis.

- Create a sampling frame: Develop a list of all individuals or elements in the population from which the sample will be drawn. The sampling frame should be comprehensive, accurate, and up-to-date.

- Select the sample: Use the chosen sampling method to select the sample from the sampling frame. The sample should be selected randomly, or if using a non-random method, every effort should be made to minimize bias and ensure that the sample is representative of the population.

- Collect data: Once the sample has been selected, collect data from each member of the sample using appropriate research methods (e.g., surveys, interviews, observations).

- Analyze the data: Analyze the data collected from the sample to draw conclusions about the population of interest.

When to use Sampling Methods

Sampling methods are used in research when it is not feasible or practical to study the entire population of interest. Sampling allows researchers to study a smaller group of individuals, known as a sample, and use the findings from the sample to make inferences about the larger population.

Sampling methods are particularly useful when:

- The population of interest is too large to study in its entirety.

- The cost and time required to study the entire population are prohibitive.

- The population is geographically dispersed or difficult to access.

- The research question requires specialized or hard-to-find individuals.

- The data collected is quantitative and statistical analyses are used to draw conclusions.

Purpose of Sampling Methods

The main purpose of sampling methods in research is to obtain a representative sample of individuals or elements from a larger population of interest, in order to make inferences about the population as a whole. By studying a smaller group of individuals, known as a sample, researchers can gather information about the population that would be difficult or impossible to obtain from studying the entire population.

Sampling methods allow researchers to:

- Study a smaller, more manageable group of individuals, which is typically less time-consuming and less expensive than studying the entire population.

- Reduce the potential for data collection errors and improve the accuracy of the results by minimizing sampling bias.

- Make inferences about the larger population with a certain degree of confidence, using statistical analyses of the data collected from the sample.

- Improve the generalizability and external validity of the findings by ensuring that the sample is representative of the population of interest.

Characteristics of Sampling Methods

Here are some characteristics of sampling methods:

- Randomness : Probability sampling methods are based on random selection, meaning that every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. This helps to minimize bias and ensure that the sample is representative of the population.

- Representativeness : The goal of sampling is to obtain a sample that is representative of the larger population of interest. This means that the sample should reflect the characteristics of the population in terms of key demographic, behavioral, or other relevant variables.

- Size : The size of the sample should be large enough to provide sufficient statistical power for the research question at hand. The sample size should also be appropriate for the chosen sampling method and the level of precision desired.

- Efficiency : Sampling methods should be efficient in terms of time, cost, and resources required. The method chosen should be feasible given the available resources and time constraints.

- Bias : Sampling methods should aim to minimize bias and ensure that the sample is representative of the population of interest. Bias can be introduced through non-random selection or non-response, and can affect the validity and generalizability of the findings.

- Precision : Sampling methods should be precise in terms of providing estimates of the population parameters of interest. Precision is influenced by sample size, sampling method, and level of variability in the population.

- Validity : The validity of the sampling method is important for ensuring that the results obtained from the sample are accurate and can be generalized to the population of interest. Validity can be affected by sampling method, sample size, and the representativeness of the sample.

Advantages of Sampling Methods

Sampling methods have several advantages, including:

- Cost-Effective : Sampling methods are often much cheaper and less time-consuming than studying an entire population. By studying only a small subset of the population, researchers can gather valuable data without incurring the costs associated with studying the entire population.

- Convenience : Sampling methods are often more convenient than studying an entire population. For example, if a researcher wants to study the eating habits of people in a city, it would be very difficult and time-consuming to study every single person in the city. By using sampling methods, the researcher can obtain data from a smaller subset of people, making the study more feasible.

- Accuracy: When done correctly, sampling methods can be very accurate. By using appropriate sampling techniques, researchers can obtain a sample that is representative of the entire population. This allows them to make accurate generalizations about the population as a whole based on the data collected from the sample.

- Time-Saving: Sampling methods can save a lot of time compared to studying the entire population. By studying a smaller sample, researchers can collect data much more quickly than they could if they studied every single person in the population.

- Less Bias : Sampling methods can reduce bias in a study. If a researcher were to study the entire population, it would be very difficult to eliminate all sources of bias. However, by using appropriate sampling techniques, researchers can reduce bias and obtain a sample that is more representative of the entire population.

Limitations of Sampling Methods

- Sampling Error : Sampling error is the difference between the sample statistic and the population parameter. It is the result of selecting a sample rather than the entire population. The larger the sample, the lower the sampling error. However, no matter how large the sample size, there will always be some degree of sampling error.