- Japanese Culture

- Traditional culture

Shinto Symbols: The Meanings of the Most Common Symbols Seen at Japanese Shinto Shrines

- Jack Xavier

The Japanese religion called Shinto may seem clouded in mystery to many non-Japanese. Indeed, even to Japanese people, there are many aspects of Shinto that are not well-understood, particularly the meaning behind the various Shinto symbols. Learning a little about Shinto will lead to many questions: Why are the gates red? What is the relevance of the lightning-shaped paper decorations? And why are there ropes wrapped around trees? Today we will be diving into the world of Shinto, discussing its background and the hidden meanings behind some of Shinto's more striking symbols.

This post may contain affiliate links. If you buy through them, we may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

What Is Shinto?

Before we get into the meaning behind Shinto symbols, let’s go over some of the basic concepts connected to Shinto to get a better understanding of the religion (if we can even call it that). Like any religion, it is difficult to concisely define Shinto in a few words, however, it is notable for its polytheistic worship of “kami,” meaning “gods or spirits that exist in all things.” Because of this belief that kami reside in all things across nature—such as mountains, trees, waterfalls, etc—Shinto is also classified as an animistic religion, one that worships nature or nature spirits. Another term to describe Shinto is “kami-no-michi,” or “the way of the gods.”

Unlike some religions, there is no central authority that dictates the rules and regulations of Shinto, and as a result, practices can vary greatly from region to region and even neighboring shrines.

Shinto Symbols

Now that we have laid the groundwork for what makes Shinto unique, let's take a look at some of the more notable Shinto symbols and motifs and the meanings behind them. The six Shinto symbols we will be covering today are " torii ," " shimenawa ," " shide ," " sakaki ," " tomoe ," and " shinkyo ."

Torii Gates, The Entrance to Shinto Shrines

Perhaps the most recognizable symbols of Shintoism are the majestic gates that mark the entrance to Shinto shrines. Made of wood or stone, these two-post gateways are known as “torii” and show the boundaries in which a kami lives. The act of passing through a torii is seen as a form of purification, which is very important when visiting a shrine, as purification rituals are a major function in Shinto.

After learning about what torii are, it is natural to wonder why so many are painted such a vibrant shade of red (or orange). In Japan, the color red is representative of the sun and life, and it is also said to ward off bad omens and disasters. Once again, by passing through these red gates, visitors to a shrine are cleansed of any bad energy, ensuring that only good energy will be brought to the Kami that resides inside. On a less spiritual and more practical note, the color red is also the color of the lacquer which has traditionally been used to coat the wood of the torii and protect it against the elements.

Having said this, not all torii are red. There are a variety of torii made of unlacquered wood, stone (usually white or grey in color), and even metal. While there are a great number of color variations (including black), there is an even greater number of shapes (somewhere around 60 different varieties!). The two most common kinds, however, are "myojin" and "shinmei" torii. Myojin torii are curved upwards at their ends and have a crossbeam that extends past the posts (as in the photo above). Shinmei torii, however, have a straight top and a crossbeam that ends at each post (as in the photo below).

・Some of Japan's Most Recognizable Torii

When speaking of torii, perhaps the most famous location is Kyoto's Fushimi Inari Shrine . This iconic shrine plays host to literally thousands of orange torii gates that wind up the mountain.

Another very famous torii can be found at Ikutsushima Shrine on an island called Miyajima. Only 40 minutes from Hiroshima City, this majestic torii is quite spectacular as it rises up out of the sea.

Oarai-Isosaki Shrine in Ibaraki Prefecture is home to another iconic torii that sits on a rocky outcropping off the shore. This torii is simple yet beautiful, particularly at sunset or when a turbulent sea sends waves crashing onto the rock.

One of Tokyo's most iconic torii is the giant first gate at Yasukuni Shrine . The massive metal torii has a simple design, but is awe-inspiring due to its gigantic size, standing 25 meters (82 feet) tall.

Another of the most highly-photographed torii gates in Japan is at Hakone Shrine in Hakone, Kanagawa Prefecture. The gate stands in the water of Lake Ashi near the foot of Mt. Fuji. This torii is so popular that those hoping to take a photo often need to wait in line for more than two hours.

Saitama Prefecture's Mitsumine Shrine not only has a gorgeous setting, nestled in the mountains around the city of Chichibu, but it is also home to a beautiful gold-accented torii with a less common "miwa" design.

Shimenawa, Shinto's Sacred Rope

"Shimenawa" are ropes, often adorned with white zig-zag-shaped ornaments. They can vary greatly in size and diameter, with some being not much more than a few threads, while others are massive and thick! Shimenawa are typically used to mark the boundaries of sacred space and are said to ward off evil spirits.

They are often seen hanging from torii, wrapped around sacred trees and rocks (within which kami are said to reside), or even fastened around that waist of grand champion sumo wrestlers! These special trees, rocks, and "yokozuna" (sumo grand champs) are known as “yorishiro,” meaning something that attracts gods or has a god living within.

Shide, the White, Zig-Zag Papers

One particular item you may notice when walking on the premises of a shrine is the zig-zag white papers, often hanging from the aforementioned shimenawa. These curious items can be found all over the place within a shrine and are often used to demarcate the boundaries of a sacred space or border within the shrine. The lightning-shaped decorations are called “shide” (pronounced "she-day") and are also used in a variety of purification ceremonies. If you go at the right time, you might even see shide attached to special wands used by Shinto priests performing said ceremonies.

There are two theories behind why shide have their lightning shape. One claims that the shape is representative of the infinite power of the gods, and another suggests that as rain, clouds, and lightning are elements of a good harvest, lightning-shaped shide are a prayer to the gods for a bountiful season.

There are a variety of different shide-adorned wands used in Shinto, with subtle differences between them in terms of style. Two of these wands are called “gohei” and “haraegushi." Shrine maidens called “miko” use the gohei wand with two shide attached in rituals and ceremonies to bless people, but the main purpose of the wand is to bless objects or cleanse sacred places of negative energy.

The haraegushi wand with many shide attached is used for the same purpose of cleansing but under different circumstances. A Shinto priest will rhythmically wave the haraegushi over a person or a person's newly obtained objects, such as a new house or car to perform this purification ritual.

Sakaki, Shinto’s Sacred Tree

As mentioned previously, nature worship is a key element of Shintoism, trees playing a particularly important role. Certain types of trees are considered sacred and are known as “shinboku.” Not unlike torii, these trees, which surround a shrine, create a sacred fence inside of which is deemed a purified space.

Although there are a few types of trees that are considered sacred, perhaps there is none more important than the sakaki, a flowering evergreen native to Japan. Sakaki trees are commonly found planted around shrines to act as a sacred fence, and a branch of sakaki is sometimes used as an offering to the gods. One of the reasons that sakaki trees are considered sacred in Shinto has to do with the fact that they are evergreens and therefore symbolic of immortality. Another more important reason is tied to a legend in which a sakaki tree was decorated in order to lure Amaterasu, the sun goddess, out of her hiding place inside a cave. This myth (described in more detail in the shinkyo section below) gives a special symbolism to the sakaki tree that is celebrated in Shinto ritual to this day.

Tomoe, The Swirling Commas

The swirling "tomoe" symbol may remind many of China’s well-known yin-yang symbol. However, the meaning and use are quite different. Tomoe, often translated as “comma,” were commonly used in Japanese badges of authority called “mon,” and as such tomoe are associated with samurai.

Tomoe can feature two, three, or even four commas in their design. The three-comma "mitsu-domoe", however, is the most commonly used in Shintoism and is said to represent the interaction of the three realms of existence: heaven, earth, and the underworld.

Keep an eye out for tomoe and you will see them used to decorate all manner things from taiko drums and protective charms to lanterns and Japanese-style roofs!

Shinkyo, Shinto's God Mirror

Our final Shinto symbol for discussion is in the “shinkyo,” or "god mirror," a mystical object said to connect our world to the spirit realm. Shinkyo can be seen displayed at Shinto alters as an avatar of the kami, the idea being that the god will enter the mirror in order to interface with our world.

This belief goes all the way back to a legend involving the Japanese sun goddess, Amaterasu, who once went into hiding in a cave, thereby plunging the world into darkness. In order to coax her out of the cave, numerous other gods gathered outside the cave and threw a party. The gods hung jewels and a mirror from a sakaki tree in front of the cave to distract Amaterasu's attention should she venture outside. Curious about the festive noises, Amaterasu peeked out of the cave and asked why the other gods were celebrating. In response, she was told that there was a goddess even more beautiful than herself outside the cave. Upon exiting the cave, she was greeted by the mirror and her own reflection, at which point, the other gods took the opportunity to seal the cave shut with a shimenawa.

Later, this same mirror was later given to Amaterasu's grandson with the instructions to worship it as if it were Amaterasu herself. In this way, one does not necessarily pray to a shinkyo, but rather to the god of that shrine for which the mirror is acting as a physical avatar. The shinkyo is considered a "shintai," or a physical stand-in that the kami can inhabit in the human realm.

By the way, the cave described in the legend is actually a real place, now called the Amanoyasugawara Shrine, in Miyazaki Prefecture (pictured above). It's a bit off the beaten path but is a very cool place to visit once you know this story.

Even with what we have covered today, there is much more to learn when it comes to Shinto, the way of the gods. If you are curious to learn more about Japanese culture and shrines, take a look at our articles “ Proper Shrine Worship Etiquette ” and “ 10 Important Points To Note About Praying at a Shrine ”.

Although we have only scratched the surface of Shinto symbols in this article, hopefully, it will give you a greater appreciation for the small details and fascinating stories behind the symbols. When you have the opportunity to visit a Shinto shrine, please keep an eye out for all of the symbols mentioned above!

If you want to give feedback on any of our articles, you have an idea that you'd really like to see come to life, or you just have a question on Japan, hit us up on our Facebook , Twitter , or Instagram !

The information in this article is accurate at the time of publication.

tsunagu Japan Newsletter

Subscribe to our free newsletter and we'll show you the best Japan has to offer!

About the author

Related Articles

Related interests.

- Music & instruments

- Japanese tea ceremony

- Theater & Plays

- Traditional crafts

Restaurant Search

Tsunagu japan sns.

Subscribe to the tsunagu Japan Newsletter

Sign up to our free newsletter to discover the best Japan has to offer.

Connect with Japan through tsunagu Japan

Let us introduce you to the best of Japan through our free newsletter: sightseeing spots, delicious food, deep culture, best places to stay, and more!

Japanese Dragon Symbol Meaning: Origins and Interpretations

Dragons are legendary creatures that have long been a fascinating subject in various cultures around the world. In Japan, the dragon holds a special significance and is deeply rooted in their history, mythology, and art. So what is the meaning behind the Japanese dragon symbol, and how did it come to be?

In this article, we will explore the origins and interpretations of the Japanese dragon symbol, delving into its mythology, portrayal in art, and the traditional beliefs associated with it. Join us as we unravel the mysteries of this powerful and awe-inspiring creature.

Table of Contents

Meaning and Symbolism of the Japanese Dragon

The Japanese dragon is a powerful and revered symbol in Japanese culture. It is associated with various meanings and symbolism, representing different concepts and qualities.

One of the primary meanings of the Japanese dragon is strength and power. The dragon is often depicted as a majestic creature with immense physical strength and the ability to control elements such as fire and water. This symbolizes the dragon’s dominance and authority.

In Japanese mythology, the dragon is also associated with wisdom and knowledge. Dragons are believed to possess ancient wisdom and are often depicted as wise and mystical beings. They are seen as protectors of knowledge and guardians of sacred places.

Furthermore, the Japanese dragon is considered a symbol of good fortune and luck. It is believed to bring blessings and prosperity to those who possess its image or invoke its presence. The dragon is often depicted alongside other auspicious symbols in Japanese art and architecture.

Additionally, the dragon is associated with longevity and immortality . It is believed to have the power to live for thousands of years and is revered for its eternal existence. The dragon’s serpentine body is seen as a representation of the often cyclical and continuous nature of life .

In Japanese culture, the dragon is also associated with transformation and change. It is believed to have the ability to shape-shift and take different forms, symbolizing the fluidity of life and the capacity for personal growth and transformation.

Overall, the Japanese dragon holds significant meaning and symbolism in Japanese culture, representing strength, wisdom, good fortune, longevity, and transformation.

Origins of the Japanese Dragon Symbol

The Japanese dragon symbol holds deep cultural and historical significance in Japan. Its origins can be traced back to ancient Chinese mythology, where the dragon was revered as a powerful and benevolent creature. The concept of the dragon was then adopted and adapted by the Japanese culture, giving rise to its unique interpretation.

In Japanese folklore, the dragon is known as “ryu” and is believed to possess extraordinary powers and wisdom. It is often depicted as a giant serpent-like creature with scales, horns, and claws. Unlike its Western counterparts, the Japanese dragon is not associated with evil or destruction, but rather represents strength, good fortune, and protection.

The influence of the dragon symbol can be seen in various aspects of Japanese culture, including art, literature, and festivals. It is commonly depicted in traditional Japanese paintings, sculptures, and tattoos. The dragon is also a prominent figure in Japanese mythology and is associated with many legendary stories and legends.

Overall, the Japanese dragon symbol has its roots in ancient Chinese mythology but has evolved over time to become a distinct and unique symbol in Japanese culture. It represents power, wisdom, and protection, and continues to be revered and celebrated in Japan today.

The Japanese Dragon in Mythology

The Japanese dragon holds a significant place in Japanese mythology and folklore. It is often revered as a powerful and wise creature that possesses supernatural abilities. The myths surrounding the Japanese dragon vary across different regions of Japan, but they generally depict the dragon as a guardian and bringer of fortune.

In Japanese mythology, the dragon is believed to have control over various elements, including water and weather. It is often associated with rain and storms, and is considered to be the ruler of the seas and bodies of water. This association with water is also why dragons are often depicted as serpentine creatures with long bodies, resembling the shape of a river or ocean current.

The Japanese dragon is often portrayed as a benevolent being that protects the land and its people. It is believed to bring good fortune, prosperity, and success. Many temples and shrines in Japan have dragon statues or carvings as a symbol of protection and prosperity.

The dragon also holds a symbolic meaning in relation to the imperial family of Japan. In Japanese myth, the imperial family is said to be descended from the gods, and the dragon is one of the sacred creatures associated with the gods. As a result, the dragon is closely tied to the symbolism of the imperial family and is often depicted in imperial regalia.

Overall, the Japanese dragon in mythology represents power, wisdom, protection, and good fortune. Its role as a guardian and bringer of prosperity has made it an important symbol in Japanese culture and art.

The Japanese Dragon in Art

The Japanese dragon is a prominent motif in Japanese art, and its representation can vary depending on the artist and the style of art. Here are some common interpretations of the Japanese dragon in art:

Traditional Paintings: In traditional Japanese paintings, known as “nihonga,” the dragon is often depicted with a long, serpentine body, sharp claws, and colorful scales. These paintings often portray the dragon in dynamic poses, surrounded by clouds or water, symbolizing its connection to the elements.

Ukiyo-e Prints: Ukiyo-e prints are a popular form of Japanese art that emerged during the Edo period. Dragons in ukiyo-e prints are often depicted as fierce and powerful creatures. They are sometimes shown in battle scenes, alongside samurai warriors or mythical beings.

Ceramics and Pottery: The dragon is a common motif found on Japanese ceramics and pottery. These pieces often depict the dragon in a more stylized and abstract manner, with simplified lines and shapes. Dragon motifs can be found on everything from tea bowls to sake sets.

Kimono Design: The dragon is also frequently incorporated into kimono designs. These designs can range from intricate, embroidered dragons to simpler, printed patterns. The dragon motif is believed to bring good luck and protection when incorporated into clothing.

The Japanese dragon’s representation in art reflects its significance and symbolism in Japanese culture. Whether depicted in traditional paintings, ukiyo-e prints, ceramics, or kimono designs, the dragon is a powerful and revered creature that continues to inspire artists and captivate audiences.

Traditional Beliefs and the Japanese Dragon

In Japanese culture, the dragon holds a significant place and is revered as a divine creature. It is believed to bring good fortune, protection, and fertility. The dragon is seen as a symbol of power, strength, and wisdom.

According to traditional beliefs, dragons are guardians of the spiritual world and are associated with the elements of water, earth and the heavens. They are believed to have the ability to control weather and natural phenomena, such as rain, wind, and clouds.

The Japanese dragon is also closely associated with the Imperial family and has been used as a symbol of the emperor’s power and authority. It is often depicted on emblems, flags, and various other forms of art.

In Japanese folklore, dragons are often depicted as benevolent creatures that bring blessings and protection. They are believed to be protectors of the land and its people, guarding against evil spirits and bringing prosperity. It is common to see dragon motifs in temples, shrines, and traditional ceremonies.

Overall, the Japanese dragon holds deep cultural and spiritual significance in Japanese society. It symbolizes power, protection, and prosperity, and is an essential part of Japan’s rich mythology and traditional beliefs.

The Japanese dragon holds a rich history and symbolism in Japanese culture. From its origins in mythology to its representation in art, the Japanese dragon is seen as a powerful and auspicious creature. It is associated with strength, wisdom, and good fortune.

Throughout history, the Japanese dragon has been revered and respected for its connection to nature and the spiritual realm. Its presence in traditional beliefs and its depiction in art showcase the deep cultural significance of the Japanese dragon. Whether seen as a guardian or a bringer of luck, the Japanese dragon continues to hold a special place in the hearts and minds of the Japanese people.

Liked this? Share it!

You May Also Like

- The Meaning Behind Dragon Tattoos: Symbolism and Significance

- Dreaming About a Dragon: Symbolism and Interpretations

- Bearded Dragon: Symbolism, Meanings, and History

- What Does a Red Dragon Symbolize?

Linda Callaway is a passionate history buff and researcher specializing in ancient history, symbolism, and dream interpretation. Her inquisitive nature has been a life-long pursuit, from her childhood days spent exploring the past, to her current academic studies of the ancient world. Linda has a strong interest in the symbolism associated with everyday objects, as well as the interpretation of dreams as a way to uncover hidden truths.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Terms and Conditions - Privacy Policy

Japanese Color Meanings – Symbolic Colors in Japanese Culture

All colors have meaning, but they are not all the same, as different countries and cultures play a big part in how people perceive colors. Japan is a country steeped in history, where colors are perceived differently to the Western world. They have developed a beautiful language of colors that can be seen in their clothes, art, and rituals. The Japanese culture has also been influenced by the Western world, but many of the Japanese color meanings are still applicable today. Let us now discuss the various color meanings in Japan, so we can gain a little more insight into this remarkable culture!

Table of Contents

- 1.1 Meaning of Kimono Colors

- 2.1 Red (Aka)

- 2.2 White (Shiro)

- 2.3 Black (Kuro)

- 2.4 Blue (Ao)

- 2.5 Green (Midori)

- 2.6 Purple (Murasaki)

- 2.7 Orange (Orenji)

- 2.8 Yellow (Kiiro)

- 2.9 Brown (Chairo)

- 2.10 Pink (Pinku)

- 2.11 Gold (Kin’iro)

- 2.12 Silver (Gin’iro)

- 3.1 What Are Some of the Lucky Colors in Japan?

- 3.2 What Does Red Mean in Japan?

- 3.3 What Is the Most Popular Color in Japan Today?

What Is the Influence of Colors in the Japanese Culture?

There are quite a few lucky colors in Japan, some are more important at weddings, while others are often used in various rituals. There are also some rules to using different colors, especially with the kimono colors. Besides the influence of the Western world, traditional Japanese colors have also been heavily influenced by China. The influence of Japanese color symbolism goes as far back as the seventh century when there was a heavy Chinese presence in Japan.

The color meanings in Japan may not be the same as in China, but many of the colors have their origin in various Chinese beliefs, from Confucianism and Buddhism to Taoism. Some of these influenced how colors were associated with social classes, which then affected the growth of Japanese color meanings.

One of the biggest influences on Japanese color symbolism was the philosophy of Zen Buddhism, which is similar to the Japanese philosophy of Shintoism. These two religions overlapped, but later in the 19 th century, they were officially separated by the Meiji regime. Shinto philosophy has animalistic connections, where various nature spirits are worshiped, and where various colors have meaning.

The colors are what represent the core values of living a good and modest life. The four primary colors in this Japanese system include red, white, blue, and black. Other colors also have meaning, but these four colors are prominent and form part of most traditional Japanese architecture , and clothing, and are used in other events.

Meaning of Kimono Colors

The kimono is a traditional Japanese garment that has existed for many years. The kimono is a symbol of good fortune and long life, and the patterns and colors used are connected to the virtues of the wearer, or it is related to a special event, or it can also be related to a specific season. So, many of the colors and patterns are only worn at a particular time of year. For example, if you wear blue, which is a summer color in spring, it could be considered improper.

The kimono colors are similar to the traditional Japanese colors. The one part of the outfit that is seen as the most important is the sash or belt, which is known as the obi.

This part of the outfit acts as a focus point, so the same kimono can have different “belts”, which can change the whole impression the outfit makes. So, if a woman has a colorful obi or belt, and is wearing a white kimono, it could mean she is off to a wedding, even though white is a symbol of mourning. Next, let us discuss in more detail the different Japanese color meanings.

Traditional Japanese Colors and Their Meaning

Two of the more prominent Japanese colors are red and white, which can be found in the country’s national flag. Both these colors are also used as decorations for various events and are mainly associated with joy. The colors are also important in certain ceremonies like weddings or birthdays. Let us now look at these two colors in more detail, followed by a few other important and lucky colors in Japan. The term for color in Japan is “iro”.

What does red mean in Japan? Red is one of the major colors in Japan and the color means many things, such as passion, strength, self-sacrifice, authority, prosperity, and happiness. Red is also the symbolic color of the nation and is used as a full red circle that represents the sun, surrounded by white on the national flag. When festivals are held, red and white are often the colors you will notice. Red is also seen as the color meaning peace and wealth within the family. Red will also be a color you see at birthdays and other events, for example, if money is offered as a gift, it usually comes in a red envelope.

The red color is also used often in Japanese architecture, mostly at the Shinto shrines. The red color or “akani”, is considered to offer protection from evil. Red is also used to strengthen the spiritual connection with the gods being worshiped in the shrines.

Red was also used in the 15 to 16 th century, during the Japanese civil wars. The samurai warriors wore the colors as they represented power and strength. The red color has also been used for centuries by Japanese women as makeup. For many years before lipstick became popular, noblewomen made traditional lipstick from safflowers, which is still used by some today. The color is believed to help protect their beauty.

White (Shiro)

White is a color that stands for purity and is also considered a blessed and sacred color. White forms the background for the national flag, which symbolizes the people’s reverence for their gods. White also represents humility, simplicity, divinity, truth, and mourning. In past years, white was often the color worn to funerals and was not generally used in everyday life.

Today, the Shinto priests still wear white, and it is the color that is the focus at many of the shrines, for example, white pebbles or sand, representing the purity of the gods.

The samurai would also wear white clothing when performing the hara-kiri or seppuku ritual, a form of ritualistic suicide. When Japan was opened up to the Western world, there was some influence and today white is often worn as an everyday color, while black has become the color for mourning.

Black (Kuro)

Black is a popular color and is mainly associated with mystery, formality, night, mourning, elegance, and anger. The color can also represent evil, unhappiness, and misfortune. Traditionally, black is also associated with masculinity and men wore black at events like weddings. One of the older methods of using black in Japan, was in tattoos, especially by fishermen. The samurai also liked to wear black armor, which shone and reflected. The black color has also been used since the earliest days when women wore makeup.

It was tradition to even apply black to the teeth, using a combination of vinegar and iron, which is also believed to prevent tooth decay. This is not practiced all that much today, but a few still observe the traditions at funerals or other special occasions.

In calligraphy, black also plays an important part, especially in what is known as “ink painting” or “sumi-e”. This involves using black ink on a white space or surface, which is usually handmade paper. The artist uses various shades of black to produce beautiful compositions.

Blue is associated with fidelity, coolness, cleanliness, and purity, and is one of the most important lucky colors in Japan. Today, the word “ao” is used to describe blue, however, in the past, it described both blue and green and there was not much to distinguish the two colors. Eventually, the word “midori” came into the picture, and today describes the color green.

However, the word “ao” is still used to describe some words, for example, the green traffic lights are known as “ao shingo”, which means “blue signal”.

The color was very common among the Japanese people, as they used dyes from certain plants that were quite common. When the country was opened to the West, many of the visitors noticed how prolific the color was and named it “Japan blue”. Today, the color is still popular and applied to both everyday clothing items and formal wear like Japanese kimonos.

Green (Midori)

Green is another one of the lucky colors in Japan and is also associated with growth, youthfulness, fertility, and vitality. The color is popular in clothing as it represents freshness and restfulness. Tea is another important part of Japanese culture, and matcha green tea stands out with a particular shade of green. In Japan, nature is also important, and they celebrate “Greenery Day” every April to show respect for all things natural and green.

This came about because Emperor Showa (1901 – 1989), the 124th Emperor of Japan, loved nature. To show respect and honor, this day was dedicated to him on his birthday in April.

Purple (Murasaki)

Purple is a color that, as with many cultures, is associated with royalty and nobility, and common folk were not allowed to wear the color for many years. The purple color also signifies spirituality, wisdom, and luxury. Purple is also seen as the color of warriors as it is a symbol of strength. The color was difficult to come by and make, so it was rare and expensive, which also made it unavailable to the common people.

Today, the color is more commonly worn and is seen as a bold and luxurious color option.

However, in the early years, there was the “twelve-level cap and rank system”, which represented the hierarchy system in government that was different from the hereditary positions. This meant officials got posts because of merit. The 12 ranks were identified by the color cap worn by each official. A deep purple was reserved for the top officials only. Also, when Buddhism was introduced to Japan, the monk who displayed high levels of virtue could wear purple. The color purple is also closely associated with wisteria flowers, which are as popular as cherry blossoms in Japan.

Orange (Orenji)

Orange is a color that represents happiness and love and is a popular color with clothing in Japan. The color orange also symbolizes knowledge and development . The color is written today in the katakana writing system as “orenji”, but the traditional word for the orange color is “daidaiiro”.

Yellow (Kiiro)

Yellow, the color of sunshine represents nature and is a sacred color. Maybe not as significant as red or white, but yellow certainly has a place in the hearts of the Japanese people. In the past, a yellow chrysanthemum was worn to symbolize courage. Today, yellow is used at railway crossings and children wear yellow caps because it helps to increase visibility.

There are various terms or sayings that are also used with the color yellow. For example, a “yellow voice”, means the sharp voices of children and women.

Brown (Chairo)

As with Western associations, brown is also seen as a color of the earth in Japanese culture. The color brown also represents durability and strength. The word that represents brown, “chairo”, is the word for “tea color”, which can be various shades of brown . As mentioned before, tea is an important part of the Japanese culture.

Pink (Pinku)

Pink is another popular color in Japan and can be seen in clothing and other items. The pink color represents youth, good health, happiness, femininity, and spring. The color has a cute and child-like association but is also considered a color of romance and love. The Sakura or cherry blossom trees, which are popular in Japan, are also a beautiful shade of pink.

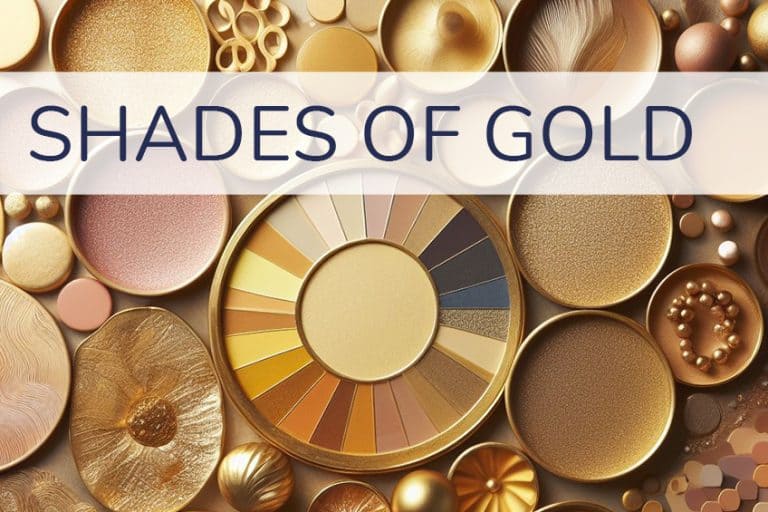

Gold (Kin’iro)

Gold is the color that represents prestige, royalty, and wealth. It is the color of the heavens and can often be found in temples and shrines. Gold threads were also often used in traditional wear like the kimono. A beautiful art form known as Kintsugi uses gold to mend broken pieces of pottery, which is a symbol of how you should embrace your imperfections and flaws.

Silver (Gin’iro)

Silver is often used in things like weapons and tools, and represents strength, precision, and masculinity. Other associations with silver include reliability, intelligence, modesty, security, and maturity. Silver jewelry is also important in Japanese culture and is used in special ceremonies and other celebrations.

Learning the significance of colors can be interesting, especially if you bring in different cultural aspects. Understanding the Japanese color meanings can be fascinating and inspiring, but it can also be challenging. There are many influences and beliefs, and even though there is so much more to the importance of color, we hope that we have provided a clear and simple explanation of the color meanings in Japan.

Take a look at our Japanese colors webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some of the lucky colors in japan .

The color that sits at the top of the list of lucky colors in Japan is blue. However, red is also a favorable color, along with white, purple, green, and yellow.

What Does Red Mean in Japan?

Red has many meanings in Japan, but it is a color that represents peace, strength, protection, power, and prosperity. Red is a strong spiritual color that is said to ward off evil and bad luck.

What Is the Most Popular Color in Japan Today?

Even though there are many significant colors that have important meanings in Japan, recent surveys taken in 2019 indicate that blue is one of the more popular colors, closely followed by black, white, and pink.

In 2005, Charlene completed her Wellness Diplomas in Therapeutic Aromatherapy and Reflexology from the International School of Reflexology and Meridian Therapy. She worked for a company offering corporate wellness programs for a couple of years, before opening up her own therapy practice. It was in 2015 that a friend, who was a digital marketer, asked her to join her company as a content creator, and this is where she found her excitement for writing.

Since joining the content writing world, she has gained a lot of experience over the years writing on a diverse selection of topics, from beauty, health, wellness, travel, and more. Due to various circumstances, she had to close her therapy practice and is now a full-time freelance writer. Being a creative person, she could not pass up the opportunity to contribute to the Art in Context team, where is was in her element, writing about a variety of art and craft topics. Contributing articles for over three years now, her knowledge in this area has grown, and she has gotten to explore her creativity and improve her research and writing skills.

Charlene Lewis has been working for artincontext.org since the relaunch in 2020. She is an experienced writer and mainly focuses on the topics of color theory, painting and drawing.

Learn more about Charlene Lewis and the Art in Context Team .

Cite this Article

Charlene, Lewis, “Japanese Color Meanings – Symbolic Colors in Japanese Culture.” Art in Context. October 25, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/japanese-color-meanings/

Lewis, C. (2023, 25 October). Japanese Color Meanings – Symbolic Colors in Japanese Culture. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/japanese-color-meanings/

Lewis, Charlene. “Japanese Color Meanings – Symbolic Colors in Japanese Culture.” Art in Context , October 25, 2023. https://artincontext.org/japanese-color-meanings/ .

Similar Posts

Shades of Gold Color – 120+ Gold Color Tones To Know

Beach Color Palette – 25 Stylish Décor Ideas

Hot Pink Color – Exploring Shades of Hot Pink and Combinations

Meaning of the Color Green – From Renewal to Growth

20 Things That Are Brown – Earthy Elegance

Crimson Color – How to Make and Use Crimson Red in Art

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

To support our work, we invite you to accept cookies or to subscribe.

You have chosen not to accept cookies when visiting our site.

The content available on our site is the result of the daily efforts of our editors. They all work towards a single goal: to provide you with rich, high-quality content. All this is possible thanks to the income generated by advertising and subscriptions.

By giving your consent or subscribing, you are supporting the work of our editorial team and ensuring the long-term future of our site.

If you already have purchased a subscription, please log in

What is the translation of "representation" in Japanese?

"representation" in japanese, representation {noun}, mental representation {noun}, proportional representation {noun}, knowledge representation {noun}, irreducible representation {noun}, translations.

- open_in_new Link to source

- warning Request revision

Context sentences

English japanese contextual examples of "representation" in japanese.

These sentences come from external sources and may not be accurate. bab.la is not responsible for their content.

Monolingual examples

English how to use "representation" in a sentence, english how to use "mental representation" in a sentence, english how to use "proportional representation" in a sentence, english how to use "knowledge representation" in a sentence, english how to use "irreducible representation" in a sentence, synonyms (english) for "representation":.

- histrionics

- internal representation

- mental representation

- theatrical performance

- representation

pronunciation

- reporting to the emperor

- repose of souls

- repository or treasure house

- reprehensible

- reprehension

- represent by signs

- representational art

- representative

- representative director

- representative example

- representative government

- representative of Gifu and Mie prefectures

- representative point

- representative system

- represented

- representing others in a conference

Have a look at the Tswana-English dictionary by bab.la.

Social Login

- Look up in Linguee

- Suggest as a translation of "representation"

Linguee Apps

▾ dictionary english-japanese, representation —, romanization (representation of foreign words using the roman alphabet) —, proportional representation electoral system (n which party votes are cast, and candidates from each party are elected based on an ordered list available to the public) —, electoral quota (e.g. in a proportional representation system) —, tower crowned by a representation of the chinese firebird —, representation of a face surrounded by or made from leaves —, normalization (e.g. in floating-point representation system) —, law for preventing unjustifiable extra or unexpected benefit and misleading representation —, proportional representation system in which both party and individual votes are cast, seats are distributed amongst parties by proportion of vote obtained, and candidates are elected in descending order of number of votes obtained —, normalized form (e.g. in floating-point representation) —, indicative (kanji whose shape is based on logical representation of an abstract idea) —, paper, cloth, wood, etc. representation of a sacred object —, proportional representation system in which votes are cast for a publicly available list of party members or for individual members of that list —, icon or representation of a user in a shared virtual reality —, 1st note in the tonic solfa representation of the diatonic scale —, 4th note in the tonic solfa representation of the diatonic scale —, 3rd note in the tonic solfa representation of the diatonic scale —, 6th note in the tonic solfa representation of the diatonic scale —, 7th note in the tonic solfa representation of the diatonic scale —, iteration mark (used to represent repetition of the previous character) —, representative director (i.e. someone chosen by the board of directors from among the directors to actually represent the company in its dealings with the outside world) —, part of a kanji for which the role is primarily to represent the pronunciation (as opposed to the meaning) —, (prior to the advent of kana) kanji used to represent readings of words, selected for their kun-yomi, regardless of meaning —, using the chinese-reading of kanji to represent native japanese words (irrespective of the kanji's actual meaning) —, (unscrupulous) sales methods used by someone falsely claiming to represent a charitable (social welfare) organization —, iteration mark used to represent repetition of the previous kanji (to be read using its kun-yomi) —, company president, with responsibility to represent the company in its dealings with the outside world —, using the japanese-reading of kanji to represent native japanese words (irrespective of the kanji's actual meaning) —, part of a kanji for which the role is primarily to represent the meaning (as opposed to the pronunciation) —, signs, symbols and characters used in manga to represent actions, emotions, etc. —, using multiple simple paper masks to represent different emotions in a play (from the middle of the edo period) —, iteration mark shaped like the hiragana "ku" (used in vertical writing to represent repetition of two or more characters) —, feel (on adj-stem to represent a third party's apparent emotion) —, represent —, ▾ external sources (not reviewed).

- This is not a good example for the translation above.

- The wrong words are highlighted.

- It does not match my search.

- It should not be summed up with the orange entries

- The translation is wrong or of bad quality.

Translation of "Representation" into Japanese

代表, 表現, 代理 are the top translations of "Representation" into Japanese. Sample translated sentence: This mode of representation parallels in Japanese art . ↔ これ は 日本 絵画 の 表現 方法 に も 通じ る 。

That which represents another. [..]

English-Japanese dictionary

システム論における、抽象的または実在する物体、関係、あるいは変更についての、機能またはプロパティ

This mode of representation parallels in Japanese art .

これ は 日本 絵画 の 表現 方法 に も 通じ る 。

acting (principal, etc.) [..]

I don't currently have legal representation .

僕 に は 今 の ところ 法的 な 代理 権 が な い 。

Less frequent translations

Show algorithmically generated translations

Automatic translations of " Representation " into Japanese

Images with "representation", phrases similar to "representation" with translations into japanese.

- representational art

- legal representation 法定代理

- simultaneously running for a seat in a single-member constituency and a seat in a proportionally representated constituency

- decimal representation 小数

- pictorial representation 視覚表現

- party-list proportional representation 政党名簿比例代表

- proportional representation system in which votes are cast for a publicly available list of party members or for individual members of that list

- variable-point representation system

Translations of "Representation" into Japanese in sentences, translation memory

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

12 Semantic representation

Gabriella Vigliocco, Deafness, Cognition, and Language Center, Department of Human Communication Science and Department of Psychology, University of London.

David P. Vinson, Deafness, Cognition, and Language Center, Department of Human Communication Science and Department of Psychology, University of London.

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article explores how word meaning is represented by speakers of a language, reviewing psychological perspectives on the representation of meaning. It starts by outlining four key issues in the investigation of word meaning, then introduces current theories of semantics. Meaning representation has long interested philosophers (since Aristotle) and linguists, in addition to psychologists, and a very extensive literature exists in these allied fields. When considering semantic representation, four fundamental questions to ask are: How are word meanings related to conceptual structures? How is the meaning of each word represented? How are the meanings of different words related to one another? Can the same principles of organisation hold in different content domains? The article also discusses holistic theories of semantic representation, along with featural theories.

T his chapter deals with how word meaning is represented by speakers of a language, reviewing psychological perspectives on the representation of meaning. We start by outlining four key issues in the investigation of word meaning, then we introduce current theories of semantics, and we end with a brief discussion of new directions.

Meaning representation has long interested philosophers (since Aristotle) and linguists (e.g. Chierchia and McConnell-Ginet, 2000 ; Dowty, 1979 ; Pustejovsky, 1993 ; see Jackendoff, 2002 ), in addition to psychologists, and a very extensive literature exists in these allied fields. However, given our goal to discuss how meaning is represented in speakers' minds/brains, we will not be concerned with theories and debates arising primarily from these fields except where the theories have psychological or neural implications (as for example the work by linguists such as Jackendoff, 2002 ; Kittay, 1987 ; Lakoff, 1987 ; 1992 ). Moreover, the discussion we present is limited to the meaning of single words; it will not concern the representation and processing of the meaning of larger linguistic units such as sentences and text.

12.1 Key issues in semantic representation

When considering how meaning is represented, four fundamental questions to ask are: (1) How are word meanings related to conceptual structures? (2) How is the meaning of each word represented? (3) How are the meanings of different words related to one another? (4) Can the same principles of organization hold in different content domains (e.g. words referring to objects, words referring to actions, words referring to properties)? With few exceptions, existing theories of semantic organization have made explicit claims concerning the representation of each meaning and the relations among different word meanings, while the relation between conceptual and semantic structures is often left implicit, and the issue of whether different principles are needed for representation of different content domains is often neglected. Let us address these questions in turn.

12.1.1 How are word meanings related to concept ual knowledge?

Language allows us to share experiences, needs, thoughts, desires, etc.; thus, word meanings need to map into our mental representations of objects, actions, properties, etc. in the world. Moreover, children come to the language learning task already equipped with substantial knowledge about the world (based on innate biases and concrete experience; e.g. Bloom, 1994 ; Gleitman, 1990 ); thus, word meanings (or semantics) must be grounded in conceptual knowledge (mental representations of objects, events, etc. that are non-linguistic). This claim is certainly uncontroversial in the cognitive sciences and neuroscience: it is not so unusual, in fact, for researchers to assume (explicitly, or more often implicitly) that concepts and word meanings are the same thing, or at least are linked on a one-to-one mapping (e.g.Humphreys et al., 1999 ). It has also been discussed in bilingualism research (Grosjean, 1998 ) where this issue has important ramifications for theories of the representation of meaning in multiple languages.

In the concepts and categorization literature, scholars treat semantics and concepts as entirely interchangeable. Typically, experiments on the structure of conceptual knowledge use words as stimuli but the findings are discussed in terms of concepts, under the tacit assumption that the use of words in a given task should produce comparable results to nonlinguistic stimuli (e.g. pictures, or artificial categories). In other words, it is often assumed that the conceptual system is entirely responsible for categorizing entities in the world (physical, mental), whereas the assignment of a name to a conceptual referent (and its retrieval) is a transparent and straightforward matter.

Obviously, word meanings and concepts must be tightly related, and when we activate semantic representations we also activate conceptual information. One striking demonstration of the fact that comprehending language entails activation of information beyond linguistic meaning comes from imaging studies showing that primary motor areas are activated when speakers see or hear sentences or even single words referring to motion, in comparison to sentences referring to abstract concepts (Tettamanti et al., 2005 ), non-words (Hauk et al., 2004 ), or spectrally rotated speech (Vigliocco et al., 2006 ). These activations indicate that the system engaged in the control of action is also automatically engaged in understanding language related to action. Because of this tight link between conceptual structure and word meanings, research into the latter cannot dispense with the former. The issue that we must address is whether concepts and word meanings can be treated as completely interchangeable, as is often assumed.

12.1.1.1 Concepts and word meanings: do we need to draw a line?

As discussed in Murphy ( 2002 ), effects of category membership and typicality are well established in both the concepts and categorisation literature (for concepts) (e.g.Rosch, 1978 ) and in the psycholinguistic literature (for words) (e.g.Federmeier and Kutas, 1999 ; Kelly et al., 1986 ). Moreover, properties that have been argued to have explanatory power in the structure of conceptual knowledge and its breakdown in pathological conditions (e.g. semantic dementia) such as correlation among conceptual features, shared and distinctive features (e.g. Gonnerman et al., 1997 ; McRae and Cree, 2002 ; McRae et al., 1997 ; Tyler et al., 2000 ; see Moss, Tyler, and Taylor, Chapter 13 this volume), have also been shown to predict semantic effects such as semantic priming among words (e.g.McRae and Boisvert, 1998 ; Vigliocco et al., 2004 ). For example, McRae and Boisvert ( 1998 ) showed that previously conflicting patterns of results from semantic priming studies could be accounted for in terms of featural overlap and featural correlation between prime and target word.

Thus, if the factors that affect conceptual structures also affect semantic representations, it would seem to be parsimonious to consider conceptual and semantic representations to be the same thing, or at least to be linked on a one-to-one basis.