- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Quality improvement...

Quality improvement into practice

Read the full collection.

- Related content

- Peer review

- Adam Backhouse , quality improvement programme lead 1 ,

- Fatai Ogunlayi , public health specialty registrar 2

- 1 North London Partners in Health and Care, Islington CCG, London N1 1TH, UK

- 2 Institute of Applied Health Research, Public Health, University of Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK

- Correspondence to: A Backhouse adam.backhouse{at}nhs.net

What you need to know

Thinking of quality improvement (QI) as a principle-based approach to change provides greater clarity about ( a ) the contribution QI offers to staff and patients, ( b ) how to differentiate it from other approaches, ( c ) the benefits of using QI together with other change approaches

QI is not a silver bullet for all changes required in healthcare: it has great potential to be used together with other change approaches, either concurrently (using audit to inform iterative tests of change) or consecutively (using QI to adapt published research to local context)

As QI becomes established, opportunities for these collaborations will grow, to the benefit of patients.

The benefits to front line clinicians of participating in quality improvement (QI) activity are promoted in many health systems. QI can represent a valuable opportunity for individuals to be involved in leading and delivering change, from improving individual patient care to transforming services across complex health and care systems. 1

However, it is not clear that this promotion of QI has created greater understanding of QI or widespread adoption. QI largely remains an activity undertaken by experts and early adopters, often in isolation from their peers. 2 There is a danger of a widening gap between this group and the majority of healthcare professionals.

This article will make it easier for those new to QI to understand what it is, where it fits with other approaches to improving care (such as audit or research), when best to use a QI approach, making it easier to understand the relevance and usefulness of QI in delivering better outcomes for patients.

How this article was made

AB and FO are both specialist quality improvement practitioners and have developed their expertise working in QI roles for a variety of UK healthcare organisations. The analysis presented here arose from AB and FO’s observations of the challenges faced when introducing QI, with healthcare providers often unable to distinguish between QI and other change approaches, making it difficult to understand what QI can do for them.

How is quality improvement defined?

There are many definitions of QI ( box 1 ). The BMJ ’s Quality Improvement series uses the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges definition. 6 Rather than viewing QI as a single method or set of tools, it can be more helpful to think of QI as based on a set of principles common to many of these definitions: a systematic continuous approach that aims to solve problems in healthcare, improve service provision, and ultimately provide better outcomes for patients.

Definitions of quality improvement

Improvement in patient outcomes, system performance, and professional development that results from a combined, multidisciplinary approach in how change is delivered. 3

The delivery of healthcare with improved outcomes and lower cost through continuous redesigning of work processes and systems. 4

Using a systematic change method and strategies to improve patient experience and outcome. 5

To make a difference to patients by improving safety, effectiveness, and experience of care by using understanding of our complex healthcare environment, applying a systematic approach, and designing, testing, and implementing changes using real time measurement for improvement. 6

In this article we discuss QI as an approach to improving healthcare that follows the principles outlined in box 2 ; this may be a useful reference to consider how particular methods or tools could be used as part of a QI approach.

Principles of QI

Primary intent— To bring about measurable improvement to a specific aspect of healthcare delivery, often with evidence or theory of what might work but requiring local iterative testing to find the best solution. 7

Employing an iterative process of testing change ideas— Adopting a theory of change which emphasises a continuous process of planning and testing changes, studying and learning from comparing the results to a predicted outcome, and adapting hypotheses in response to results of previous tests. 8 9

Consistent use of an agreed methodology— Many different QI methodologies are available; commonly cited methodologies include the Model for Improvement, Lean, Six Sigma, and Experience-based Co-design. 4 Systematic review shows that the choice of tools or methodologies has little impact on the success of QI provided that the chosen methodology is followed consistently. 10 Though there is no formal agreement on what constitutes a QI tool, it would include activities such as process mapping that can be used within a range of QI methodological approaches. NHS Scotland’s Quality Improvement Hub has a glossary of commonly used tools in QI. 11

Empowerment of front line staff and service users— QI work should engage staff and patients by providing them with the opportunity and skills to contribute to improvement work. Recognition of this need often manifests in drives from senior leadership or management to build QI capability in healthcare organisations, but it also requires that frontline staff and service users feel able to make use of these skills and take ownership of improvement work. 12

Using data to drive improvement— To drive decision making by measuring the impact of tests of change over time and understanding variation in processes and outcomes. Measurement for improvement typically prioritises this narrative approach over concerns around exactness and completeness of data. 13 14

Scale-up and spread, with adaptation to context— As interventions tested using a QI approach are scaled up and the degree of belief in their efficacy increases, it is desirable that they spread outward and be adopted by others. Key to successful diffusion of improvement is the adaption of interventions to new environments, patient and staff groups, available resources, and even personal preferences of healthcare providers in surrounding areas, again using an iterative testing approach. 15 16

What other approaches to improving healthcare are there?

Taking considered action to change healthcare for the better is not new, but QI as a distinct approach to improving healthcare is a relatively recent development. There are many well established approaches to evaluating and making changes to healthcare services in use, and QI will only be adopted more widely if it offers a new perspective or an advantage over other approaches in certain situations.

A non-systematic literature scan identified the following other approaches for making change in healthcare: research, clinical audit, service evaluation, and clinical transformation. We also identified innovation as an important catalyst for change, but we did not consider it an approach to evaluating and changing healthcare services so much as a catch-all term for describing the development and introduction of new ideas into the system. A summary of the different approaches and their definition is shown in box 3 . Many have elements in common with QI, but there are important difference in both intent and application. To be useful to clinicians and managers, QI must find a role within healthcare that complements research, audit, service evaluation, and clinical transformation while retaining the core principles that differentiate it from these approaches.

Alternatives to QI

Research— The attempt to derive generalisable new knowledge by addressing clearly defined questions with systematic and rigorous methods. 17

Clinical audit— A way to find out if healthcare is being provided in line with standards and to let care providers and patients know where their service is doing well, and where there could be improvements. 18

Service evaluation— A process of investigating the effectiveness or efficiency of a service with the purpose of generating information for local decision making about the service. 19

Clinical transformation— An umbrella term for more radical approaches to change; a deliberate, planned process to make dramatic and irreversible changes to how care is delivered. 20

Innovation— To develop and deliver new or improved health policies, systems, products and technologies, and services and delivery methods that improve people’s health. Health innovation responds to unmet needs by employing new ways of thinking and working. 21

Why do we need to make this distinction for QI to succeed?

Improvement in healthcare is 20% technical and 80% human. 22 Essential to that 80% is clear communication, clarity of approach, and a common language. Without this shared understanding of QI as a distinct approach to change, QI work risks straying from the core principles outlined above, making it less likely to succeed. If practitioners cannot communicate clearly with their colleagues about the key principles and differences of a QI approach, there will be mismatched expectations about what QI is and how it is used, lowering the chance that QI work will be effective in improving outcomes for patients. 23

There is also a risk that the language of QI is adopted to describe change efforts regardless of their fidelity to a QI approach, either due to a lack of understanding of QI or a lack of intention to carry it out consistently. 9 Poor fidelity to the core principles of QI reduces its effectiveness and makes its desired outcome less likely, leading to wasted effort by participants and decreasing its credibility. 2 8 24 This in turn further widens the gap between advocates of QI and those inclined to scepticism, and may lead to missed opportunities to use QI more widely, consequently leading to variation in the quality of patient care.

Without articulating the differences between QI and other approaches, there is a risk of not being able to identify where a QI approach can best add value. Conversely, we might be tempted to see QI as a “silver bullet” for every healthcare challenge when a different approach may be more effective. In reality it is not clear that QI will be fit for purpose in tackling all of the wicked problems of healthcare delivery and we must be able to identify the right tool for the job in each situation. 25 Finally, while different approaches will be better suited to different types of challenge, not having a clear understanding of how approaches differ and complement each other may mean missed opportunities for multi-pronged approaches to improving care.

What is the relationship between QI and other approaches such as audit?

Academic journals, healthcare providers, and “arms-length bodies” have made various attempts to distinguish between the different approaches to improving healthcare. 19 26 27 28 However, most comparisons do not include QI or compare QI to only one or two of the other approaches. 7 29 30 31 To make it easier for people to use QI approaches effectively and appropriately, we summarise the similarities, differences, and crossover between QI and other approaches to tackling healthcare challenges ( fig 1 ).

How quality improvement interacts with other approaches to improving healthcare

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

QI and research

Research aims to generate new generalisable knowledge, while QI typically involves a combination of generating new knowledge or implementing existing knowledge within a specific setting. 32 Unlike research, including pragmatic research designed to test effectiveness of interventions in real life, QI does not aim to provide generalisable knowledge. In common with QI, research requires a consistent methodology. This method is typically used, however, to prove or disprove a fixed hypothesis rather than the adaptive hypotheses developed through the iterative testing of ideas typical of QI. Both research and QI are interested in the environment where work is conducted, though with different intentions: research aims to eliminate or at least reduce the impact of many variables to create generalisable knowledge, whereas QI seeks to understand what works best in a given context. The rigour of data collection and analysis required for research is much higher; in QI a criterion of “good enough” is often applied.

Relationship with QI

Though the goal of clinical research is to develop new knowledge that will lead to changes in practice, much has been written on the lag time between publication of research evidence and system-wide adoption, leading to delays in patients benefitting from new treatments or interventions. 33 QI offers a way to iteratively test the conditions required to adapt published research findings to the local context of individual healthcare providers, generating new knowledge in the process. Areas with little existing knowledge requiring further research may be identified during improvement activities, which in turn can form research questions for further study. QI and research also intersect in the field of improvement science, the academic study of QI methods which seeks to ensure QI is carried out as effectively as possible. 34

Scenario: QI for translational research

Newly published research shows that a particular physiotherapy intervention is more clinically effective when delivered in short, twice-daily bursts rather than longer, less frequent sessions. A team of hospital physiotherapists wish to implement the change but are unclear how they will manage the shift in workload and how they should introduce this potentially disruptive change to staff and to patients.

Before continuing reading think about your own practice— How would you approach this situation, and how would you use the QI principles described in this article?

Adopting a QI approach, the team realise that, although the change they want to make is already determined, the way in which it is introduced and adapted to their wards is for them to decide. They take time to explain the benefits of the change to colleagues and their current patients, and ask patients how they would best like to receive their extra physiotherapy sessions.

The change is planned and tested for two weeks with one physiotherapist working with a small number of patients. Data are collected each day, including reasons why sessions were missed or refused. The team review the data each day and make iterative changes to the physiotherapist’s schedule, and to the times of day the sessions are offered to patients. Once an improvement is seen, this new way of working is scaled up to all of the patients on the ward.

The findings of the work are fed into a service evaluation of physiotherapy provision across the hospital, which uses the findings of the QI work to make recommendations about how physiotherapy provision should be structured in the future. People feel more positive about the change because they know colleagues who have already made it work in practice.

QI and clinical audit

Clinical audit is closely related to QI: it is often used with the intention of iteratively improving the standard of healthcare, albeit in relation to a pre-determined standard of best practice. 35 When used iteratively, interspersed with improvement action, the clinical audit cycle adheres to many of the principles of QI. However, in practice clinical audit is often used by healthcare organisations as an assurance function, making it less likely to be carried out with a focus on empowering staff and service users to make changes to practice. 36 Furthermore, academic reviews of audit programmes have shown audit to be an ineffective approach to improving quality due to a focus on data collection and analysis without a well developed approach to the action section of the audit cycle. 37 Clinical audits, such as the National Clinical Audit Programme in the UK (NCAPOP), often focus on the management of specific clinical conditions. QI can focus on any part of service delivery and can take a more cross-cutting view which may identify issues and solutions that benefit multiple patient groups and pathways. 30

Audit is often the first step in a QI process and is used to identify improvement opportunities, particularly where compliance with known standards for high quality patient care needs to be improved. Audit can be used to establish a baseline and to analyse the impact of tests of change against the baseline. Also, once an improvement project is under way, audit may form part of rapid cycle evaluation, during the iterative testing phase, to understand the impact of the idea being tested. Regular clinical audit may be a useful assurance tool to help track whether improvements have been sustained over time.

Scenario: Audit and QI

A foundation year 2 (FY2) doctor is asked to complete an audit of a pre-surgical pathway by looking retrospectively through patient documentation. She concludes that adherence to best practice is mixed and recommends: “Remind the team of the importance of being thorough in this respect and re-audit in 6 months.” The results are presented at an audit meeting, but a re-audit a year later by a new FY2 doctor shows similar results.

Before continuing reading think about your own practice— How would you approach this situation, and how would you use the QI principles described in this paper?

Contrast the above with a team-led, rapid cycle audit in which everyone contributes to collecting and reviewing data from the previous week, discussed at a regular team meeting. Though surgical patients are often transient, their experience of care and ideas for improvement are captured during discharge conversations. The team identify and test several iterative changes to care processes. They document and test these changes between audits, leading to sustainable change. Some of the surgeons involved work across multiple hospitals, and spread some of the improvements, with the audit tool, as they go.

QI and service evaluation

In practice, service evaluation is not subject to the same rigorous definition or governance as research or clinical audit, meaning that there are inconsistencies in the methodology for carrying it out. While the primary intent for QI is to make change that will drive improvement, the primary intent for evaluation is to assess the performance of current patient care. 38 Service evaluation may be carried out proactively to assess a service against its stated aims or to review the quality of patient care, or may be commissioned in response to serious patient harm or red flags about service performance. The purpose of service evaluation is to help local decision makers determine whether a service is fit for purpose and, if necessary, identify areas for improvement.

Service evaluation may be used to initiate QI activity by identifying opportunities for change that would benefit from a QI approach. It may also evaluate the impact of changes made using QI, either during the work or after completion to assess sustainability of improvements made. Though likely planned as separate activities, service evaluation and QI may overlap and inform each other as they both develop. Service evaluation may also make a judgment about a service’s readiness for change and identify any barriers to, or prerequisites for, carrying out QI.

QI and clinical transformation

Clinical transformation involves radical, dramatic, and irreversible change—the sort of change that cannot be achieved through continuous improvement alone. As with service evaluation, there is no consensus on what clinical transformation entails, and it may be best thought of as an umbrella term for the large scale reform or redesign of clinical services and the non-clinical services that support them. 20 39 While it is possible to carry out transformation activity that uses elements of QI approach, such as effective engagement of the staff and patients involved, QI which rests on iterative test of change cannot have a transformational approach—that is, one-off, irreversible change.

There is opportunity to use QI to identify and test ideas before full scale clinical transformation is implemented. This has the benefit of engaging staff and patients in the clinical transformation process and increasing the degree of belief that clinical transformation will be effective or beneficial. Transformation activity, once completed, could be followed up with QI activity to drive continuous improvement of the new process or allow adaption of new ways of working. As interventions made using QI are scaled up and spread, the line between QI and transformation may seem to blur. The shift from QI to transformation occurs when the intention of the work shifts away from continuous testing and adaptation into the wholesale implementation of an agreed solution.

Scenario: QI and clinical transformation

An NHS trust’s human resources (HR) team is struggling to manage its junior doctor placements, rotas, and on-call duties, which is causing tension and has led to concern about medical cover and patient safety out of hours. A neighbouring trust has launched a smartphone app that supports clinicians and HR colleagues to manage these processes with the great success.

This problem feels ripe for a transformation approach—to launch the app across the trust, confident that it will solve the trust’s problems.

Before continuing reading think about your own organisation— What do you think will happen, and how would you use the QI principles described in this article for this situation?

Outcome without QI

Unfortunately, the HR team haven’t taken the time to understand the underlying problems with their current system, which revolve around poor communication and clarity from the HR team, based on not knowing who to contact and being unable to answer questions. HR assume that because the app has been a success elsewhere, it will work here as well.

People get excited about the new app and the benefits it will bring, but no consideration is given to the processes and relationships that need to be in place to make it work. The app is launched with a high profile campaign and adoption is high, but the same issues continue. The HR team are confused as to why things didn’t work.

Outcome with QI

Although the app has worked elsewhere, rolling it out without adapting it to local context is a risk – one which application of QI principles can mitigate.

HR pilot the app in a volunteer specialty after spending time speaking to clinicians to better understand their needs. They carry out several tests of change, ironing out issues with the process as they go, using issues logged and clinician feedback as a source of data. When they are confident the app works for them, they expand out to a directorate, a division, and finally the transformational step of an organisation-wide rollout can be taken.

Education into practice

Next time when faced with what looks like a quality improvement (QI) opportunity, consider asking:

How do you know that QI is the best approach to this situation? What else might be appropriate?

Have you considered how to ensure you implement QI according to the principles described above?

Is there opportunity to use other approaches in tandem with QI for a more effective result?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

This article was conceived and developed in response to conversations with clinicians and patients working together on co-produced quality improvement and research projects in a large UK hospital. The first iteration of the article was reviewed by an expert patient, and, in response to their feedback, we have sought to make clearer the link between understanding the issues raised and better patient care.

Contributors: This work was initially conceived by AB. AB and FO were responsible for the research and drafting of the article. AB is the guarantor of the article.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: This article is part of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on ideas generated by a joint editorial group with members from the Health Foundation and The BMJ , including a patient/carer. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication. Open access fees and The BMJ ’s quality improvement editor post are funded by the Health Foundation.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

- Olsson-Brown A

- Dixon-Woods M ,

- Batalden PB ,

- Berwick D ,

- Øvretveit J

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges

- Nelson WA ,

- McNicholas C ,

- Woodcock T ,

- Alderwick H ,

- ↵ NHS Scotland Quality Improvement Hub. Quality improvement glossary of terms. http://www.qihub.scot.nhs.uk/qi-basics/quality-improvement-glossary-of-terms.aspx .

- McNicol S ,

- Solberg LI ,

- Massoud MR ,

- Albrecht Y ,

- Illingworth J ,

- Department of Health

- ↵ NHS England. Clinical audit. https://www.england.nhs.uk/clinaudit/ .

- Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership

- McKinsey Hospital Institute

- ↵ World Health Organization. WHO Health Innovation Group. 2019. https://www.who.int/life-course/about/who-health-innovation-group/en/ .

- Sheffield Microsystem Coaching Academy

- Davidoff F ,

- Leviton L ,

- Taylor MJ ,

- Nicolay C ,

- Tarrant C ,

- Twycross A ,

- ↵ University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust. Is your study research, audit or service evaluation. http://www.uhbristol.nhs.uk/research-innovation/for-researchers/is-it-research,-audit-or-service-evaluation/ .

- ↵ University of Sheffield. Differentiating audit, service evaluation and research. 2006. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.158539!/file/AuditorResearch.pdf .

- ↵ Royal College of Radiologists. Audit and quality improvement. https://www.rcr.ac.uk/clinical-radiology/audit-and-quality-improvement .

- Gundogan B ,

- Finkelstein JA ,

- Brickman AL ,

- Health Foundation

- Johnston G ,

- Crombie IK ,

- Davies HT ,

- Hillman T ,

- ↵ NHS Health Research Authority. Defining research. 2013. https://www.clahrc-eoe.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/defining-research.pdf .

EDITORIAL article

Editorial: continuous quality improvement (cqi)—advancing understanding of design, application, impact, and evaluation of cqi approaches.

- 1 The University of Sydney, The University Centre for Rural Health, Lismore, NSW, Australia

- 2 James Cook University, College of Medicine and Dentistry, Townsville, QLD, Australia

- 3 University Research Co., LLC, Chevy Chase, MD, United States

Editorial on the Research Topic

Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI)—Advancing Understanding of Design, Application, Impact, and Evaluation of CQI Approaches

Continuous quality improvement (CQI) approaches are increasingly used to bridge gaps between the evidence base for best practice, what actually happens in practice, and achievement of better population health outcomes. Among a range of quality improvement strategies, CQI is characterized by iterative use of processes to identify quality problems, develop solutions, and implement and evaluate changes. Application of CQI in health care is evolving and evidence of their success continues to emerge ( 1 – 3 ).

Through the Research Topic, “Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI)—Advancing Understanding of Design, Application, Impact, and Evaluation of CQI approaches,” we aimed to aggregate knowledge of useful approaches to tailoring CQI approaches for different contexts, and for implementation, scale-up and evaluation of CQI interventions/programs. This Research Topic has attracted seven original research reports and three “perspectives” papers. Thirty-six authors have contributed from eighteen research organizations, universities, and policy and service delivery organizations. All original research articles and one perspective paper come from the Australian Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease (ABCD) National Research Partnership (“ABCD Partnership”) in Indigenous primary healthcare settings ( 4 – 6 ). To some extent, this reflects the interests and connections of two of the Topic Editors, who were lead investigators on the ABCD Partnership. This Partnership has made a prominent contribution to original research on CQI in primary healthcare internationally, with over 50 papers published in the peer-reviewed literature over the past 10 years.

As most articles in this Research Topic arise from the ABCD Partnership, a brief overview of the program provides a useful backdrop. The program originated in 2002 in the Top End of the Northern Territory in Australia, and built on substantial prior research and evaluation of CQI methods in Indigenous primary healthcare. With substantial growth and enthusiastic support from service providers and researchers around Australia, the ABCD Partnership has focused since 2010 on exploring clinical performance variation, examining strategies for improving primary care, and working with health service staff, management and policy makers to enhance effective implementation of successful strategies ( 4 ). By the end of 2014, the ABCD Partnership had generated the largest and most comprehensive dataset on quality of care in Australian Indigenous primary healthcare settings. The Partnership’s work is being extended through the Centre of Research Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement ( 6 ).

Several research papers included in this Research Topic illustrate consistent findings of wide variation in adherence to clinical best-practice guidelines between health centers ( Bailie et al. ; Burnett et al. ; Matthews et al. ). The papers also show variation among different aspects of care, with relatively good delivery of some modes of care [ Bailie et al. ; ( 7 )] and poor delivery of others—such as follow-up of abnormal clinical or laboratory findings. These findings are evident in eye care ( Burnett et al. ), general preventive clinical care ( Bailie et al. ), and in absolute cardiovascular risk assessment ( Matthews et al. ; Vasant et al. ). The findings are consistent with other ABCD-related publications on diabetes care ( 8 ), preventive health ( 9 ), maternal care ( 10 ), child health ( 11 ), rheumatic heart disease ( 12 ), and sexual health ( 13 ).

Systems to support good clinical care are explored by Woods et al. in five primary healthcare centers that were identified through ABCD data as achieving substantially greater improvement than others over successive CQI cycles. Attention to understanding and improving systems was shown to be vital to the improvements in clinical care achieved by these health centers. Improved staffing and commitment to working in the community were standout aspects of health center systems that underpinned improvements in clinical care.

On a wider scale, engagement by primary healthcare services in the ABCD Partnership has enabled assessment of system functioning at district, regional, state, and national levels, as reflected in stakeholders’ perceptions of barriers and enablers to addressing gaps in chronic illness care and child health, and identifying drivers for improvement ( Bailie et al. ). Primary drivers included staff capability, availability and use of information systems and decision support tools, embedding of CQI processes, and community engagement. We have also shown how consistent and sustained policy and infrastructure support for CQI enables large-scale and ongoing improvements in quality of care ( 3 ).

Commitment of the ABCD team to promoting effective use of CQI data is reflected in one “perspective” paper, which describes a theory-informed cyclical interactive dissemination strategy ( Laycock et al. ). Concurrent developmental evaluation provides a mechanism for learning and refinement over successive cycles ( 14 ).

The other two perspective articles (not specifically from the ABCD program) highlight the role of facilitation in CQI and the potential for application of CQI in health professional education. The emerging evidence on facilitation as a vital tool for effective CQI should guide resourcing and approaches to CQI ( Harvey and Lynch ). The approach builds on the humanistic principles of modern CQI methods—participation, engagement, shared decision-making, enabling others, and tailoring to context. The framework for CQI approaches to health professional education described by Clithero et al. directly addresses a critical need for innovative approaches to health workforce development that will strengthen community engagement and embed CQI principles into health system functioning. The scale and scope of need in workforce development is strongly evident in findings of the ABCD program.

Importantly, CQI methods are proving useful in assessing and potentially improving delivery of evidence-based health promotion practices ( Percival et al. ). Percival’s experience in this field highlights the health facility and wider system challenges facing effective implementation of CQI methods. In health promotion these barriers include low priority given to health promotion in the face of heavy demands for acute clinical care. This work in health promotion complements other research on applying CQI to social determinants of health more broadly ( 15 ), including community food supply ( 16 ), housing ( 17 ), and education ( 18 ).

The publications in this special issue address many of the “building blocks” of high performing primary care described by Bodenheimer and colleagues in the US; namely, four foundational components (engaged leadership, data-driven improvement, empanelment, and team-based care) that are vital to facilitate the implementation of the other six elements (patient-team partnership, population management, continuity of care, prompt access to care, comprehensiveness, and care coordination) ( 19 ). They are also relevant to Australian based work on clinical microsystems and development of CQI tools for mainstream general practice, such as the Primary Care-Practice Improvement Tool (with similar components to the ABCD systems assessment tool) ( 20 ).

Continuous quality improvement is vital to improving health outcomes through system strengthening. We anticipate substantial future development of CQI methods. By late 2017, there had been over 20,000 views of this Research Topic, and many articles have already been cited in peer-review manuscripts. Further research on CQI in primary healthcare would be well guided by a systematic scoping review of literature summarizing empirical research on current knowledge in the field, and identifying key knowledge gaps.

Author Contributions

RB wrote the first draft. JB has revised content and structure. SL and EB reviewed and edited subsequent drafts. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. RB was the chief investigator on the ABCD National Research Partnership and is the chief investigator on the Centre of Research Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement. All papers published in the Research Topic received peer review from members of the Frontiers in Public Health Policy panel of reviewers who were independent of named authors on any given article published in this volume, consistent with the journal policy on conflict-of-interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of those who contributed to this Research Topic as authors, review editors, and colleagues.

The National Health and Medical Research Council funded the ABCD National Research Partnership Project (grant number 545267) and the Centre for Research Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement (grant number 1078927). In-kind and financial support was provided by the Lowitja Institute and a range of Community-Controlled and Government agencies.

Abbreviations

ABCD, audit and best practice for chronic disease; CQI, continuous quality improvement.

1. Tricco AC, Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, Moher D, Turner L, Galipeau J, et al. Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies on the management of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet (2012) 379(9833):2252–61. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60480-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Lewin S, Lavis JN, Oxman AD, Bastias G, Chopra M, Ciapponi A, et al. Supporting the delivery of cost-effective interventions in primary health-care systems in low-income and middle-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Lancet (2008) 372(9642):928–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61403-8

3. Bailie R, Matthews V, Larkins S, Thompson S, Burgess P, Weeramanthri T, et al. Impact of policy support on uptake of evidence-based continuous quality improvement activities and the quality of care for Indigenous Australians: a comparative case study. BMJ Open (2017) 7(10). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016626

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Bailie R, Si D, Shannon C, Semmens J, Rowley K, Scrimgeour DJ, et al. Study protocol: national research partnership to improve primary health care performance and outcomes for Indigenous peoples. BMC Health Serv Res (2010) 10:129. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-129

5. Bailie R, Matthews V, Brands J, Schierhout G. A systems-based partnership learning model for strengthening primary healthcare. Implement Sci (2013) 8(1):143. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-8-143

6. Bailie J, Schierhout G, Cunningham F, Yule J, Laycock A, Bailie R. Quality of primary health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People in Australia: key research findings and messages for action from the ABCD National Research Partnership. Menzies Sch Health Res (2015). doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3887.2801

7. Schierhout G, Matthews V, Connors C, Thompson S, Kwedza R, Kennedy C, et al. Improvement in delivery of type 2 diabetes services differs by mode of care: a retrospective longitudinal analysis in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care setting. BMC Health Serv Res (2016) 16(1):560. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1812-9

8. Matthews V, Schierhout G, McBroom J, Connors C, Kennedy C, Kwedza R, et al. Duration of participation in continuous quality improvement: a key factor explaining improved delivery of type 2 diabetes services. BMC Health Serv Res (2014) 14(1):578. doi:10.1186/s12913-014-0578-1

9. Bailie J, Matthews V, Laycock A, Schultz R, Burgess CP, Peiris D, et al. Improving preventive health care in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary care settings. Global Health (2017) 13(1):48. doi:10.1186/s12992-017-0267-z

10. Gibson-Helm ME, Teede HJ, Rumbold AR, Ranasinha S, Bailie RS, Boyle JA. Continuous quality improvement and metabolic screening during pregnancy at primary health centres attended by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Med J Aust (2015) 203(9):369–70. doi:10.5694/mja14.01660

11. McAullay D, McAuley K, Bailie R, Mathews V, Jacoby P, Gardner K, et al. Sustained participation in annual continuous quality improvement activities improves quality of care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. J Paediatr Child Health (2017). doi:10.1111/jpc.13673

12. Ralph AP, Fittock M, Schultz R, Thompson D, Dowden M, Clemens T, et al. Improvement in rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease management and prevention using a health centre-based continuous quality improvement approach. BMC Health Serv Res (2013) 13(1):525. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-525

13. Nattabi B, Matthews V, Bailie J, Rumbold A, Scrimgeour D, Schierhout G, et al. Wide variation in sexually transmitted infection testing and counselling at aboriginal primary health care centres in Australia: analysis of longitudinal continuous quality improvement data. BMC Infect Dis (2017) 17:148. doi:10.1186/s12879-017-2241-z

14. Laycock A, Bailie J, Matthews V, Cunningham F, Harvey G, Percival N, et al. A developmental evaluation to enhance stakeholder engagement in a wide-scale interactive project disseminating quality improvement data: study protocol for a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open (2017) 7:7. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016341

15. McDonald EL, Bailie R, Michel T. Development and trialling of a tool to support a systems approach to improve social determinants of health in rural and remote Australian communities: the healthy community assessment tool. Int J Equity Health (2013) 12(1):15. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-12-15

16. Brimblecombe J, van den Boogaard C, Wood B, Liberato SC, Brown J, Barnes A, et al. Development of the good food planning tool: a food system approach to food security in Indigenous Australian remote communities. Health Place (2015) 34:54–62. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.03.006

17. Bailie RS, Wayte KJ. A continuous quality improvement approach to indigenous housing and health. Environ Health (2006) 6(2):36–41.

Google Scholar

18. McCalman J, Bainbridge R, Russo S, Rutherford K, Tsey K, Wenitong M, et al. Psycho-social resilience, vulnerability and suicide prevention: impact evaluation of a mentoring approach to modify suicide risk for remote Indigenous Australian students at boarding school. BMC Public Health (2016) 16(1):98. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2762-1

19. Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med (2014) 12(2):166–71. doi:10.1370/afm.1616

20. Crossland L, Janamian T, Sheehan M, Siskind V, Hepworth J, Jackson CL. Development and pilot study of the primary care practice improvement tool (PC-PIT): an innovative approach. Med J Aust (2014) 201(3):S52–5. doi:10.5694/mja14.00262

Keywords: primary health care, health systems research, continuous quality improvement, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, building block

Citation: Bailie R, Bailie J, Larkins S and Broughton E (2017) Editorial: Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI)—Advancing Understanding of Design, Application, Impact, and Evaluation of CQI Approaches. Front. Public Health 5:306. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00306

Received: 20 October 2017; Accepted: 03 November 2017; Published: 23 November 2017

Edited and Reviewed by: Kai Ruggeri , University of Cambridge, United Kingdom

Copyright: © 2017 Bailie, Bailie, Larkins and Broughton. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ross Bailie, ross.bailie@sydney.edu.au

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Differentiating research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement

Research, evidence-based practice (EBP), and quality improvement support the three main goals of the Magnet Recognition Program ® and the Magnet Model component of new knowledge, innovation, and improvements. The three main goals of the Magnet Recognition Program are to: 1) Promote quality in a setting that supports professional practice 2) Identify excellence in the delivery of nursing services to patients or residents 2) Disseminate best practices in nursing services.

The Magnet Model includes five components:

- transformational leadership

- structural empowerment

- exemplary professional practice

- new knowledge, innovation, and improvements

- empirical quality outcomes.

To achieve the goals of the Magnet Recognition Program and the “new knowledge innovation and improvements” component of the Magnet Model, nurses at all levels of healthcare organizations must be involved. Many nurses may be unaware of the importance of their contributions to developing new knowledge, innovations, and improvements and may not be able to differentiate among those processes. This article explains the basic differences among research, EBP, and quality improvement (QI.) (See Comparing research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement .)

Using audit and feedback to improve compliance with evidence-based practices

Implementation: The linchpin of evidence-based practice changes

Is this quality improvement or research?

Understanding research

The purpose of conducting research is to generate new knowledge or to validate existing knowledge based on a theory. Research studies involve systematic, scientific inquiry to answer specific research questions or test hypotheses using disciplined, rigorous methods. While research is about investigation, exploration, and discovery, it also requires an understanding of the philosophy of science. For research results to be considered reliable and valid, researchers must use the scientific method in orderly, sequential steps.

The process begins with burning (compelling) questions about a particular phenomenon, such as: What do we know about the phenomenon? What evidence has been developed and reported? What gaps exist in the knowledge base?

The first part of investigation involves a systematic, comprehensive review of the literature to answer those questions. Identified knowledge gaps typically provide the impetus for developing a specific research question (or questions), a hypothesis or hypotheses, or both. Next, a decision can be made on the underlying theory that will guide the study and aid selection of type of method to be used to explore the phenomenon.

The two main study methods are quantitative (numeric) and qualitative (verbal), although mixed methods using both are growing. Quantitative studies tend to explore relationships among a set of variables related to the phenomenon, whereas qualitative studies seek to understand the deeper meaning of the involved variables.

- Quantitative studies typically involve scientific methodology to determine appropriate sample size, various designs to control for potential errors during data collection, and rigorous statistical analysis of the data.

- Qualitative studies tend to explore life experiences to give them meaning.

In all research, discovery occurs as data are collected and analyzed and results and outcomes are interpreted.

A final important step in the research process is publication of study results with a description of how they contribute to the body of knowledge. Examples of potential nursing research include conducting a systematic review of studies on preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), a randomized controlled trial exploring new wound care methods, and a qualitative study to investigate the lived experiences of patients with a specific chronic disease.

Understanding EBP

Unlike research, EBP isn’t about developing new knowledge or validating existing knowledge. It’s about translating the evidence and applying it to clinical decision-making. The purpose of EBP is to use the best evidence available to make patient-care decisions. Most of the best evidence stems from research. But EBP goes beyond research use and includes clinical expertise as well as patient preferences and values. The use of EBP takes into consideration that sometimes the best evidence is that of opinion leaders and experts, even though no definitive knowledge from research results exists. Whereas research is about developing new knowledge, EBP involves innovation in terms of finding and translating the best evidence into clinical practice.

Steps in the EBP process

The EBP process has seven critical steps:

1. Cultivate a spirit of inquiry.

2. Ask a burning clinical question.

3. Collect the most relevant and best evidence.

4. Critically appraise the evidence.

5. Integrate evidence with clinical expertise, patient preferences, and values in making a practice decision or change.

6. Evaluate the practice decision or change.

7. Disseminate EBP results.

Cultivating a spirit of inquiry means that individually or collectively, nurses should always be asking questions about how to improve healthcare delivery. The burning clinical question commonly is triggered through either a problem focus or a knowledge focus. Problem-focused triggers may arise from identifying a clinical problem or from such areas as risk management, finance, or quality improvement. Knowledge-focused triggers may come from new research results or other literature findings, new philosophies of care, or new regulations.

Regardless of the origin, the next step in the EBP process is to review and appraise the literature. Whereas a literature review for research involves identifying gaps in knowledge, a literature review in EBP is done to find the best current evidence.

Hierarchy of evidence

In searching for the best available evidence, nurses must understand that a hierarchy exists with regard to the level and strength of evidence. All of the various hierarchies of evidence are similar to some degree.

- The highest (strongest) level of evidence typically comes from a systematic review, a meta-analysis, or an established evidence-based clinical practice guideline based on a systematic review.

- Other levels of evidence come from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), other types of quantitative studies, qualitative studies, and expert opinion and analyses.

Critical appraisal

Once the evidence is gathered, the researcher must critically appraise each study to ensure its credibility and clinical significance. Critical appraisal often is thought to be tedious and time-consuming. But it’s crucial to determine not only what was done and how, but how well it was done. An easy method for conducting critical appraisal is to answer these three key questions:

- What were the results of the study? (In other words, what is the evidence?)

- How valid are the results? (Can they be trusted?)

- Will the results be helpful in caring for other patients? (Are they transferable?)

Final steps of EBP

The final steps of the EBP process include integrating the evidence with one’s clinical expertise, taking into account patient preferences, and evaluating the effectiveness of applying the evidence. Disseminating or reporting the results of EBP projects may help others learn about and apply the best evidence. Examples of potential EBP projects include implementing an evidence-based clinical practice guideline to reduce or prevent CAUTIs, evaluating an evidence-based intervention to improve wound healing, and applying an EBP to improve compliance with a specific treatment for a chronic disease.

Understanding QI

The purpose of QI is to use a systematic, data-guided approach to improve processes or outcomes. Principles and strategies involved in QI have evolved from organizational philosophies of total quality management and continuous quality improvement.

While the concept of quality can be subjective, QI in healthcare typically focuses on improving patient outcomes. So the key is to clearly define the outcome that needs to be improved, identify how the outcome will be measured, and develop a plan for implementing an intervention and collecting data before and after the intervention.

Various QI methods are available. A common format uses the acronym FOCUS-PDSA:

F ind a process to improve.

O rganize an effort to work on improvement.

C larify current knowledge of the process.

U nderstand process variation and performance capability.

S elect changes aimed at performance improvement.

P lan the change; analyze current data and predict the results.

D o it; execute the plan.

S tudy (analyze) the new data and check the results.

A ct; take action to sustain the gains.

Unlike research and EBP, QI typically doesn’t require extensive literature reviews and rigorous critical appraisal. Therefore, nurses may be much more involved in QI projects than EBP or research. Also, QI projects normally are site specific and results aren’t intended to provide generalizable knowledge or best evidence. Examples of QI projects include implementing a process to remove urinary catheters within a certain time frame, developing a process to improve wound-care documentation, and improving the process for patient education for a specific chronic disease.

Comparing research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement

- Applies a methodology, which may be quantitative or qualitative, to generate new knowledge, or validate existing knowledge based on a theory

- Uses systematic, scientific inquiry and disciplined, rigorous methods to answer a research question or test a hypothesis about an intervention

- Begins with a burning question and uses a systematic review of literature, including critical appraisal, to identify knowledge gaps

- Contains variables that can be measured and/or manipulated to describe, explain, predict, and/or control phenomena, or to develop meaning, discovery, or understanding about a particular phenomenon

Evidence-based practice

- Translates the best clinical evidence, typically from research results, to make patient care decisions

- Involves more than research use; may include clinical expertise and knowledge gained through experience

- Process begins with a burning question, which may arise from either problem focused or knowledge focused triggers

- Involves a systematic review of literature, including critical appraisal, to find the best available evidence

- Studies whether the evidence warrants a practice change

- Evaluation includes these questions: If practice change was made, did it produce the expected results? If not, why not? If so, how will the new practice be sustained?

Quality improvement

- Uses a system to monitor and evaluate the quality and appropriateness of care based on EBP and research

- Involves A systematic method for improving processes, outcomes, or both

- Evolved from continuous quality improvement and total quality management organizational philosophies

- Focuses on systems, processes, or functions or a combination

- Typically doesn’t require extensive review of literature or critical appraisal

- QI projects are site-specific; results aren’t intended to provide generalizable knowledge or best evidence

Take-away points

- Research, EBP, and QI support the three main goals of the Magnet Recognition Program and the Magnet Model components of new knowledge, innovation, and improvements.

- Research applies a methodology (quantitative or qualitative) to develop new knowledge.

- EBP seeks and applies the best clinical evidence, often from research, toward making patient-care decisions.

- QI uses systematic processes to improve patient outcomes.

All nurses should know and understand the differences among these three concepts.

Brian T. Conner is an assistant professor and undergraduate program director in the College of Nursing at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

Selected references

American Nurses Credentialing Center. Magnet Program Overview. www.nursecredentialing.org/Magnet/ProgramOverview . Accessed April 21, 2014.

Brown SJ Evidence-Based Nursing: The Research-Practice Connection . 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2013.

Burns N, Grove SK, Gray JR. The Practice of Nursing Research: Appraisal, Synthesis, and Generation of Evidence. 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

Harris JL, Roussel L, Walters SE, et al. Project Planning and Management: A Guide for CNLs, DNPs, and Nurse Executives . Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2011.

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A Guide to Best Practice . 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, et al. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM . 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

Tappen RM. Advanced Nursing research: From Theory to Practice . Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2011.

Titler MG, Kleiber D, Steelman VJ, et al. The Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality Care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am . 2001;13(4):497-509.

Visits: 35296

15 Comments .

Found this extremely helpful and broken down for easy understanding.

This is exactly what I needed, detailed and simple at the same time yet easy to understand

Briefly explained the research, EBP, and QI. Thank you!

so good thanks!! hopefully I pass my EBP test tmrw!

This article was helpful. Thank you

Thank You ! _ this the begining of a “Research made easy book”

very helpful

Why wouldn’t QI benefit from literature review and rigorous critical appraisal of the literature? Especially when DNPs and CNLs are involved. I would love to hear thoughts about this.

Very Helpful.

Research concentrate more on new knowledge and validating that existing knowledge based on a theory, while EBP is using the best evident to improve patient outcome and finally QI actually uses a systematic approach to improve the outcome.

Correct interpretation. Excellent

this article was very helpful

great information and so simple to understand

Useful brief tip. Thanks

Comments are closed.

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Human touch

Leadership style matters

Innovation in motion

Nurse referrals to pharmacy

Lived experience

The nurse’s role in advance care planning

Sleep and the glymphatic system

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

High school nurse camp

Healthcare’s role in reducing gun violence

Early Release: Nurses and firearm safety

Gun violence: A public health issue

Postpartum hemorrhage

Let’s huddle up

Nurses have the power

- Latest Articles

- Clinical Practice

- ONS Leadership

- Get Involved

- News and Views

The Difference Between Quality Improvement, Evidence-Based Practice, and Research

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on LinkedIn

- Email Article

- Print Article

As healthcare institutions become ever more complex and our focus on patient experience expands, nurses are leading and participating in research studies , evidence-based practice (EBP) projects, and quality improvement (QI) initiatives with a goal of improving patient outcomes. Research, EBP, and QI have subtle differences and frequent overlap , which can make it a challenge for nurses to identify the best option to investigating a clinical problem.

The first step is a comprehensive review of the literature with a medical librarian. This informs about the problem, what evidence has been reported, and what gaps exist in our knowledge of the problem. Then, synthesize the relevant literature and decide how best to proceed based on the outcome of the literature review, experience with previous projects, available resources, and staff time and effort.

Quality Improvement

QI projects typically don’t involve extensive literature reviews and are usually specific to one facility. The purpose of QI projects is to correct workflow processes, improve efficiencies, reduce variations in care, and address clinical administrative or educational problems . An example is assessing and implementing urinary catheter removal policies with a goal of removing catheters within a defined timeframe.

Evidence-Based Practice

EBP integrates the best available research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values to improve outcomes. The process involves asking a relevant clinical question, finding the best evidence to answer it, applying the evidence to practice, and evaluating the evidence based on clinical outcomes. An example is implementing a new evidence-based clinical practice guideline at an institution to reduce or prevent chemotherapy extravasation for patients receiving vesicant therapy.

If a literature review identifies gaps, you may conduct a study to generate new knowledge or to validate existing knowledge to answer a specific research question. Human subject approval is necessary before conducting a research study. An example is a randomized controlled trial of two skin care regimens for patients receiving external-beam radiation therapy.

Nurses at all levels of care will be involved in asking and answering focused clinical questions with a goal of improving patient outcomes. It is important to be familiar with the similarities and differences between research, EBP, and QI. Each is an excellent method to improve clinical outcomes.

Research, Evidence-Based Practice, and Quality Improvement

- Evidence-based care

- Oncology quality measures

Research, Evidence-Based Practice, and Quality Improvement Simplified

- PMID: 36595725

- DOI: 10.3928/00220124-20221207-09

Is the research process different than evidence-based practice and quality improvement, or is it the same? Scattered evidence and misperceptions regarding research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement make the answer unclear among nurses. This article clarifies and simplifies the three processes for frontline clinical nurses and nurse leaders. The three processes are described and discussed to give the reader standards for differentiating one from the other. The similarities and differences are highlighted, and examples are provided for contextualization of the methods. [ J Contin Educ Nurs . 2023;54(1):40-48.] .

- Education, Nursing, Continuing*

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Quality Improvement*

ES 9 – Improve and Innovate

Essential Public Health Service 9: Improve and innovate public health functions through ongoing evaluation, research, and continuous quality improvement

Learn how environmental health programs support Essential Public Health Service 9 and public health accreditation.

These activities support Essential Service 9 (evaluation, research, and continuous improvement).

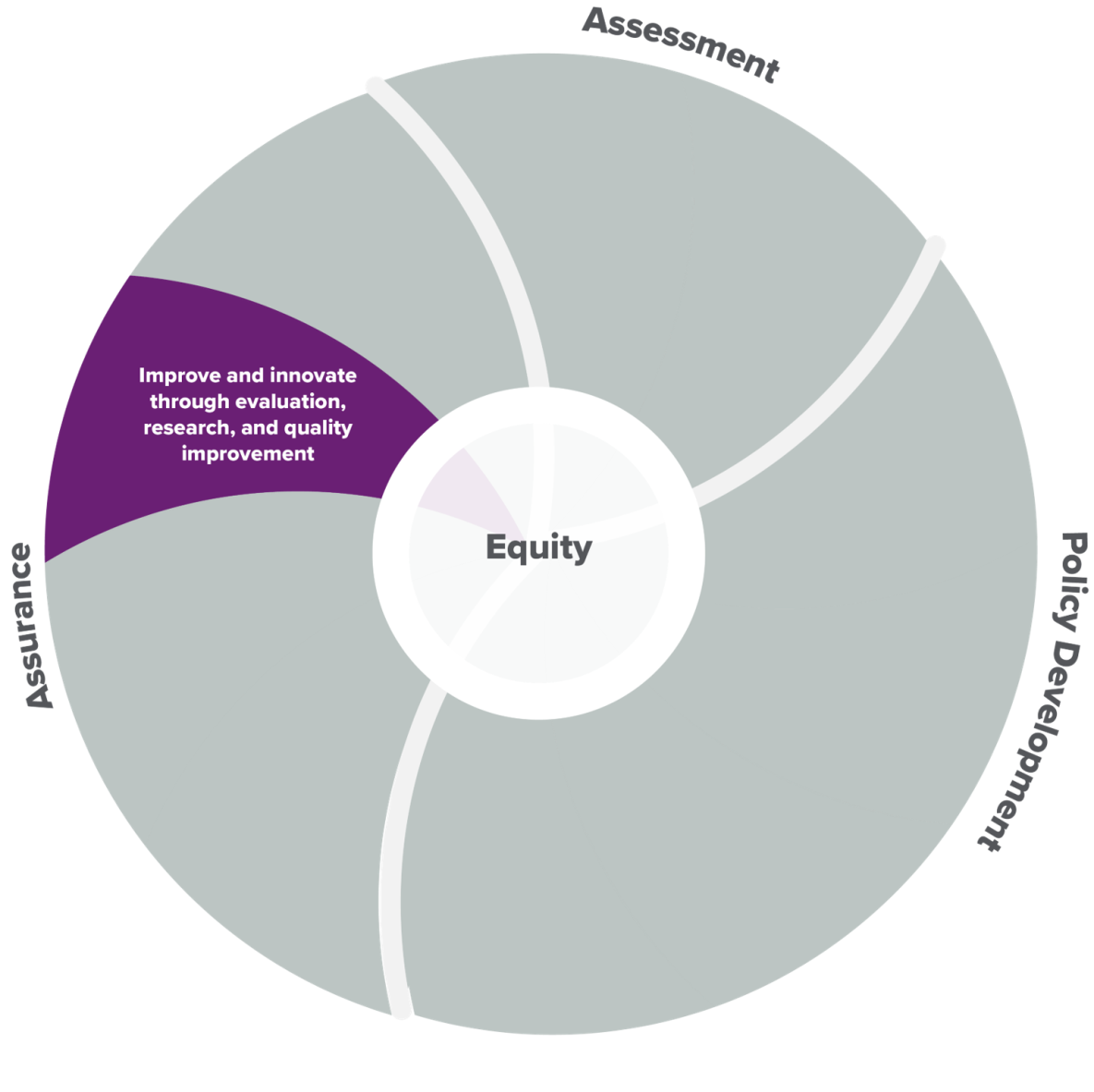

Essential service 9—improve and innovate public health functions through ongoing evaluation, research, and continuous quality improvement—is one of the essential services aligned to the Assurance core function.

Here are some examples of common activities* that help deliver essential service 9.

Building a culture of quality in environmental health programs and using quality improvement to improve environmental health programmatic efforts.

Using research, innovation, and other data to inform program decision-making.

Contributing to the evidence base around environmental health practice.

Evaluating environmental health services, policies, plans, and laws to ensure they contribute to health and do not create undue harm.

These activities connect to PHAB standards.

Environmental health programs also link to and support broader public health initiatives such as public health accreditation. Following are examples of activities that could contribute to accreditation by the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB) . Completing these activities does not guarantee conformity to PHAB documentation requirements.

PHAB Standard 9.1: Build and foster a culture of quality.

- Monitoring environmental public health services against established criteria for performance, including the number of services and inspections provided and the extent to which program goals and objectives are achieved for these services, with a focus on outcome and improvement (for example, decreased rate of illness and injury, decrease in critical inspection violations and factors, decrease in exposure).

- Engaging in performance management, including participation in the health department-wide system.

- Engaging in quality improvement efforts in the health department and implementing quality improvement projects to improve environmental health processes, programs, and interventions.

PHAB Standard 9.2: Use and contribute to developing research, evidence, practice-based insights, and other forms of information for decision-making.

- Collaborating with traditional and nontraditional partners (for example, advocacy groups, academia, other government departments) to identify opportunities to translate research findings to improve environmental public health practice and to analyze and publish findings of environmental health investigations to further general knowledge.

More Information

- 10 Essential Public Health Services

- 10 Essential Public Health Services Toolkit (Public Health National Center for Innovation)

- Environmental Public Health and the 10 Essential Services

*Examples are not exhaustive.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Quality Improvement Process: How to Plan and Measure It

Last Updated on March 21, 2024 by Owen McGab Enaohwo

Start your free 14-day trial of SweetProcess No credit card needed. Cancel anytime. Click Here To Try it for Free.

When a business takes that jump from small to more substantial, it can lose footing. Customers might complain that the product they used to love has lost the high quality they appreciated about it. The question becomes, how do you maintain quality while producing more?

Every business wants to present quality offers, but not everyone understands what it takes and how to have the best quality. And managers often get this wrong.

In this article, we will look at the quality improvement process, uncover the must-haves in a good QIP, and study the methods, tools, and steps to build a sound strategy.

SweetProcess is our software, and it’s built for teams to create and manage quality improvement documents and procedures in one place so they can focus on what drives real business growth. Without adding your credit card info, you can sign up for our 14-day free trial to see how it works.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

What Exactly Is a Quality Improvement Process?

Importance of quality improvement process in a business, key steps for planning an effective quality improvement process, enhance your company’s quality improvement process using sweetprocess, top quality improvement methodologies, common quality improvement tools, common challenges of quality improvement process, key ways to measure the quality improvement process, quality improvement process in healthcare, build an effective quality improvement process with sweetprocess.

Quality improvement process (QIP) is a journey to enhance and refine the overall quality of an organization’s products, services, and processes.

The main essence is to identify areas that need improvement, implement changes, and always monitor outcomes to ensure constant improvement. It’s driven by a commitment to meet or exceed customer expectations, comply with industry standards, and achieve organizational goals.

Let’s look in more detail at the importance and benefits of the quality improvement process.

Enhanced Brand Reputation

When a business regularly offers great products and services, it builds trust with customers, who become loyal and recommend the business to others. QIP helps to make sure that quality is maintained consistently.

Employee Engagement and Satisfaction

QIP ensures clear communication, setting expectations and reducing frustration. This clarity builds trust, enhances teamwork, and promotes collaboration. Investing in QIP not only improves products or services but also creates a workplace where employees feel valued and satisfied.

A motivated and happy team is key to delivering the quality customers expect. QIP is not just a process tool; it’s also a strategy for engaging employees, leading to overall business success.

Adaptability to Change

Change is constant, especially in a competitive market. The ability to adapt quickly can make or mar a brand. That’s where a strong QIP helps you build. It encourages you to stay vigilant, anticipating changes like shifts in customer behavior or new competitors. It promotes a culture of innovation by seeking better ways to operate.

Cost Reduction

Mistakes can be expensive, leading to rework, refunds, lost sales, and damage to your brand. QIP focuses on error prevention before they become complex issues and saves the costs of fixing mistakes. But it doesn’t stop there. QIP leads to long-term savings by promoting continuous learning and development . As you improve, you better understand processes, team capabilities, and customer needs, making informed decisions about technology, hiring, and market expansion.

Regulatory Compliance

QIP helps your business adhere to industry standards, regulations, and laws . It is a built-in guide, ensuring your business is on the right track. QIP prioritizes documenting every process and change, creating a reliable trail of evidence for compliance.

While it may seem like a lot of paperwork, this documentation serves as proof during audits or inspections, demonstrating that your business follows the rules.

Improved Productivity

Quality improvement process can transform your business into a productive powerhouse where you work smarter, not harder, and achieve more with less.

Let’s go over these ten important steps to plan a quality improvement process for your company.

Define Your Goals

Before you plan to improve your work, you must decide what you want to achieve. What are you trying to do with this improvement process? Do you want to spend less money, make customers happier, or get more work done?

Once you know your goals, you can start working toward them. Ensure your goals are specific, achievable, trackable, significant, and have a deadline.

Identify and Analyze the Current Situation

This step involves collecting information and looking at your current ways of doing things to find areas where you can improve. You can use tools like maps, charts, and checklists to write how things are done and find places where things might be slow or wasteful.

Once you know how things are, you can start thinking of ways to improve them. It’s important to include your team and others in this thinking process because they might have helpful ideas that you haven’t thought about.

Engage Stakeholders

Now that you’ve figured out where things can get better and chosen the right methods and tools, it’s time to involve the people that the changes will affect—your stakeholders.

Start by telling them about the goals and good things that will come from improving things. Explain how it will affect their work and answer questions they might have. Ask for their ideas and thoughts on how to make things better. This not only helps make sure the changes work well but also gets them more involved and feel responsible for the process.

Identify Improvement Opportunities

In order to improve your processes , you need to identify opportunities for improvement. It’s achievable by analyzing your current processes and looking for areas of waste, inefficiency, or error. You may also want to gather feedback from your stakeholders to identify problems or areas where they see room for improvement.

Keep in mind that quality improvement ideas can come from sources you least expect, so be open to suggestions from your team and stakeholders.

Set Measurable Goals

After figuring out what you want to achieve and where you can make things better, the next step is to make sure your goals are measurable. This means making sure your goals are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) .

For instance, if you want to reduce customer complaints, you could set a goal to decrease complaints by 20% in the next six months. This way, you have a specific target to aim at and a deadline to reach it.

Select Improvement Methodology and Tools

Choose from the various tools available, which could be lean, Six Sigma, or agile. Each method has its tools and techniques to find and fix problems, reduce mistakes, and boost employee productivity . However, when deciding on the method and tools, think about the business you have, how big your company is, and the QI project size.

Implement Strategy

This is where all your QI efforts in the previous steps come together. You’ll need to create a quality improvement project plan outlining the specific tasks and timelines for each part of the process.

Involve your team and stakeholders in the implementation, and ensure everyone has clear roles and responsibilities. Stay organized and take records during the implementation so you can spot any obstacles early on and make adjustments.

Monitor and Evaluate Progress

After you’ve put your quality improvement plan into action, it’s important to monitor your progress and ensure you’re on the right path to reaching your goals.

Schedule regular checks with your team and stakeholders to review the progress and pinpoint any issues or areas where you can improve. Be open-minded and be ready to change your approach when necessary.

Collect Feedback

While you’re making improvements to your QI process, it’s essential to hear from your team members. Their feedback can point out areas you can improve or your process might not work for them. You can collect feedback through surveys, interviews, or observations. You can also use data to track progress and spot places for improvement.

Standardize and Build a Culture of Continuous Improvement

You can do this through regular training, continuous iteration, and having a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) . However, getting feedback and monitoring the entire process without a platform that automates everything is stressful and time-consuming. You can also use SOP software , so you can automate the process and focus on growing your business.

Yes, you can use SweetProcess to enhance your quality improvement program. Let’s look at how our software can help you.

Document Your Process to Identify Opportunities for Improvement

SweetProcess can help you prevent scattered documents or misinformation in your quality improvement journey.

To do this, log in to SweetProcess, head to the drop-down ‘’More’’ button, and click on the “Processes” tab. After this, click on the “Create Process” button, enter a title for your process, then click “Continue.”

Then use the AI-suggested description or manually write a description of the steps to be followed to complete the process. This will help you easily spot bottlenecks later and make adjustments.

When choosing your description, always ensure that it’s simple, concise, and straight to the point. Once you’re okay with the output, click on the “Approve” button to save it.

As you can see in the image below, SweetProcess gives you the chance to know who edited or adjusted what and when exactly. Plus, you can trace each previous process version, so you can easily identify where to make adjustments.

Once you’re okay with the output, click on the “Approve” button to save it.

Leverage Reports and Analytics in SweetProcess to Make Data-Driven Decisions

SweetProcess also allows you to keep track of process data: every action, step, and task completion time is tracked, giving you a wealth of insights.

And you can use it to track changes and generate and analyze reports to see how improvements affect the quality of different procedures and processes.

As you can see in the image below, almost every important data you need is clearly shown: version history, the personnel who edited or approved a procedure, description of a process or procedure , toggles for approving requests, sign-off log, enable, disable, or preset review dates and number of times this can be done, check approval requests, and related tasks.

SweetProcess makes quality improvement a straightforward process, as it offers an easy-to-use platform that houses process steps. For instance, at Thimbleberry Financial , Amy Walls, president, and financial advisor, explained how documentation on SweetProcess helps them achieve this.