An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

- PMC10002018

Adolescent Pregnancy Outcomes and Risk Factors

Jana diabelková.

1 Department of Public Health and Hygiene, Medical Faculty, University of Pavol Jozef Šafárik, Šrobárova 2, 041 80 Košice, Slovakia

Kvetoslava Rimárová

Peter urdzík.

2 Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Medical Faculty, Louis Pasteur University Hospital, University of Pavol Jozef Šafárik, Trieda SNP 1, 040 11 Košice, Slovakia

Andrea Houžvičková

Ľubica argalášová.

3 Institute of Hygiene, Faculty of Medicine, Comenius University in Bratislava, Špitálska 24, 813 72 Bratislava, Slovakia

Associated Data

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

One of the major social and public health problems in the world is adolescent pregnancy. Adolescent pregnancy is strongly associated to less favorable results for both the mother and the newborn. We conducted this research to ascertain the impact of teenage age on neonatal outcomes and also observed the lifestyles of pregnant teenage girls. We conducted a study of 2434 mothers aged ≤19 years (n = 294) or 20–34 years (n = 2140) who gave birth in 2019–2020 at the Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics of Louis Pasteur University Hospital in Košice. The data on mothers and newborn infants have been reported from the reports on mothers at childbirth. Women between the ages of 20 and 34 served as the reference group. The teenage mothers were more likely to become pregnant if they were unmarried (OR = 14.2; 95% CI = 9.3–21.6; p < 0.001) and had a basic education or lack of education (OR = 16.8; 95% CI = 11.5–24.6; p < 0.001). Additionally, they were more likely to smoke when pregnant (OR = 5.0; 95% CI = 3.8–6.6; p < 0.001). Low birth weight was more common in newborns born to adolescent mothers than in those born to adult mothers ( p < 0.001). Our findings showed that infants of teenage mothers often had lower birth weights (−332.6 g, p < 0.001). Adolescent mothers were associated with lower Apgar scores at the first minute ( p = 0.003). As compared with the control group, pregnant teenage girls had a greater prevalence of preterm deliveries in our research ( p = 0.004). This study finds significant age-related disparities in neonatal outcomes between mothers. These results might be used to identify vulnerable groups who need special assistance and actions to reduce the probability of negative outcomes for such groups.

1. Introduction

Adolescent pregnancies are a global public health problem. Teenage pregnancy is the pregnancy of 10- to 19-year-old girls [ 1 ]. Adolescents are further divided into early (10–14 years old), middle (15–17 years old), and late adolescents (over 17 years old) [ 2 ].

According to the World Health Organization, adolescent pregnancies are a global problem for both developed and developing countries. Although the global teenage birth rate has decreased, there are regional differences in the rates of change. Adolescent pregnancies have decreased globally, from 64.5 per 1000 women in 2000 to 42.5 per 1000 women in 2021. However, there are huge differences in levels between and within countries. While the estimated global teenage birth rate has decreased, the actual number of childbirths to teenagers continues to be high. Pregnancy in girls under the age of 19 is severe in every aspect and requires very complex and long-term solutions [ 1 ].

The transition from childhood to adulthood occurs during the phase of adolescence, during which there are numerous changes in the physiological, anatomical, structural, and psychological aspects. Because many teenagers are not physically or mentally prepared for pregnancy and childbirth, they are more likely to experience complications that can have serious health consequences. Giving birth during adolescence has serious consequences for the health of the mother and her infant [ 1 ]. The adolescent age group is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes [ 2 , 3 ].

The rate of teenage pregnancies has recently been greatly affected by several significant factors. The decreasing age at menarche is one of the factors that can affect a woman’s fertility. Since the 19th century, the age at menarche has been decreasing at a rate of 2–3 months per decade in many European countries, resulting in an overall decrease of about 3 years. Most of the decrease in menarche age is related to better nutrition and health. The onset of first sexual activity occurs at a significantly younger age, which is another contributing element. Teenage pregnancy, therefore, remains a serious social, economic, and health problem [ 4 ].

Young maternal age is more likely a marker for one or more other maternal risk factors associated with poor birth outcomes. Poverty, low education, and inadequate family support are also problems. These factors increase the risk of sexually transmitted infections, unsafe abortions, and birth complications, all of which are exacerbated by inadequate prenatal care [ 5 ]. For girls, early pregnancies can have social consequences such as lower status in the household and community; stigmatization; abuse by family, peers, and partners; and early and forced marriage. Early pregnancy and childbirth during adolescence can hinder a girl’s otherwise healthy development into adulthood and negatively affect her educational opportunities, financial security, and health. Many teenage girls who are pregnant cannot continue their education or work because they are pregnant. This can have a big impact on their future [ 6 ]. In addition, children born to parents who cannot care for them face additional dangers. In the first few years of a child’s life, the mother–child relationship declines. This is primarily due to the mother’s immaturity. When teenage mothers are victims of sexual assault, the situation is even worse. Apart from their mothers, these children tend to be brought up by their grandparents and relatives, with frequent changes in caregivers. Children have a higher risk of being abused or neglected and a higher risk of failing in school and are more likely to engage in criminal behavior later on [ 7 ].

The economic, social, and political development and progress of any country depend on the healthy size of adolescents and children. As a result, the healthier the teenager is, the healthier the nation and future generations will be. Teenagers thus need special attention from us.

Understanding the issue is necessary to develop and carry out prevention initiatives to decrease teen pregnancy. Knowledge about the target groups, teenage pregnancy and birth outcomes, and the risk and preventive factors related to teenage pregnancy is needed. This information is important in choosing which risk and protective factors to target and, thus, better implementing the effective implementation of evidence-based adolescent pregnancy prevention practices.

Examining the newborn outcomes and risk variables associated with adolescent pregnancies was the aim of the present research.

2. Materials and Methods

The research took place in the years 2019–2020 in eastern Slovakia. This study included 2434 newborns and their mothers. Data were collected at the University of Pavel Jozef Šafárik’s Faculty of Medicine and the Louis Pasteur University Hospital’s Gynecology and Obstetrics Clinic in Košice. This hospital has a higher prevalence of mothers with high-risk pregnancies because it is the East Slovakian center for low birth weight and preterm birth.

The data were obtained from hospital records. Available information included the mother’s education, marital status, lifestyle, and when prenatal care began. Additionally, the Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min, the newborn’s gestational age, and the newborn’s weight were recorded. The total number of mothers in the results tables was different because not all the data for each mother were available in the clinical records. The study excluded women who were carriers of multiple pregnancies because they had a higher risk of preterm birth and lower birth weights of their newborns. Thus, women with multiple pregnancies were not included among the participants.

Maternal age was defined as the mother’s age in completed years at the time of delivery. The youngest women recruited to the cohort were 14 years old; therefore, the data for this study were limited to women aged 14–34 years at delivery who had a singleton pregnancy. The results for women under the age of 19 were compared with the results for women in the reference group (20–34 years). The age range of 20 to 34 years was chosen as the reference group because this age range had the lowest risk of developing age-related problems.

In our records, a woman who smoked at least one cigarette per day while pregnant was considered a smoker. All women who consumed 15 g of alcohol per day were considered alcohol consumers. This is equivalent to 0.5 L of 12-degree beer, 0.3 L of wine, or 0.5 dL of strong alcohol.

The neonatal outcome variables of interest in this study were low birth weight (less than 2500 g), very low birth weight (less than 1500 g), extremely low birth weight (less than 1000 g), macrosomia (birth weight greater than 4000 g), preterm birth (less than 37 weeks gestation), very preterm birth (less than 32 weeks gestation), extremely preterm birth (less than 28 weeks gestation), and low Apgar score at the first and fifth minutes (less than 7).

Most mothers completed eight prenatal care visits. Thus, we divided the group of mothers into two groups: those who had fewer than eight antenatal visits and those who had eight or more visits.

The IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 program (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze the data. The data were given as median (min–max), mean (standard deviation), and number (percent).

The data were processed using both primary characters and modified characters (categorized). Most of the findings were statistically significant, and the analysis included important discoveries that were related to the collected empirical data. The χ2 independence test, with a significance level of 0.05, was used to assess the frequency of individual variations of characteristics in the analyzed groups and subgroups. The Student’s t -test was used to compare the arithmetic means of continuous variables. The odds ratio, or, was used to compare the frequency of social and anamnestic variables in the adolescent mothers and mothers from the reference group.

Data were available for 2434 pregnancies for this analysis. A total of 294 (12.1%) of these births included teenagers between the ages of 14 and 19. The controls were 27.9 ± 3.9 years old on average, whereas the adolescents’ mean age was 17.4 ± 1.4. Table 1 displays the characteristics of the study’s participants.

Characteristics of the sample by maternal age.

Numbers in bold indicate statistically significant values.

Our study demonstrated that adolescent mothers had lower levels of education ( p < 0.001), only primary school (84.1%). About 46% of teenage girls reported smoking during pregnancy. In the reference group, the proportion of smokers was 14.6% ( p < 0.001). Alcohol consumption during pregnancy was relatively low at 0.6%, and the data on alcohol use were not statistically significant ( Table 1 ).

In the adolescent group, there were up to 45.7% of women ( p < 0.001) who went to the doctor after the first trimester. Most mothers completed eight prenatal care visits. Therefore, we divided the group of mothers into two groups: those who had fewer than eight antenatal visits and those who had eight or more visits. Up to 75.9% of teenage girls who were pregnant had fewer than eight clinic visits ( p < 0.001) ( Table 2 ).

Antennal care received by the respondents.

Adolescent girls were significantly more likely to be single (OR = 14.2; 95% CI = 9.3–21.6; p < 0.001), to have less education (OR = 16.8; 95% CI = 11.5–24.6; p < 0.001), and to smoke during pregnancy (OR = 5.0; 95% CI = 3.8–6.6; p < 0.01). They were more likely to visit a doctor for the first time during pregnancy after the first trimester (OR = 0.3; 95% CI = 0.2–0.3; p < 0.001) and were more likely to visit a doctor fewer than eight times (OR = 4.0; 95% CI = 3.0–5.3; p < 0.001) during pregnancy ( Table 3 ).

OR of various risk variables for adolescent mothers’ reproductive outcomes.

OR—odds ratio; CI—confidence interval. Numbers in bold indicate statistically significant values.

Table 4 shows the results for newborns. Infants born to teenage mothers had a significantly higher rate of low birth weight than those born to women who were adults ( p < 0.001). Our findings showed that children born to teenage mothers weighed less on average (−332.6 g, p < 0.001). In contrast to the control group, pregnant adolescents in our analysis had a higher prevalence of premature births ( p = 0.004). Children of adolescent mothers had a lower first-minute Apgar score ( p = 0.003).

Neonatal outcomes.

4. Discussion

Pregnancy in adolescence is a health problem worldwide. Teenagers themselves are a high-risk group in need of high-priority interventions. In general, most pregnancies in adolescence are extra-marital and unintended [ 2 ]. The teenage mothers in this research were more likely to be single (OR = 14.2; 95% CI = 9.3–21.6; p < 0.001), which is similar to previous studies [ 5 , 8 , 9 , 10 ].

Psychological immaturity is common among adolescent mothers. Because they do not understand the value of family planning, they often engage in risky sexual behavior and become pregnant while still in school and still living with their parents [ 9 ]. This study confirms that teenage mothers are significantly more likely to have a low level of education ( p < 0.001). These findings agreed with those of other research investigations carried out in other nations [ 2 , 9 ]. Adolescent girls often drop out of school due to pregnancy or childbirth. Sometimes problems at school and poor school performance appear even before pregnancy. Some teenage girls who are not doing well in school may find motherhood an attractive option. When these variables combine, young mothers have fewer career possibilities, often resulting in lower earnings for the rest of their lives [ 9 , 11 ]. Early pregnancies are significantly reduced by education; the more years of education, the lower the rate of early pregnancies [ 1 ].

Quitting smoking has a direct impact on the health of the fetus. Teenagers in our research were more likely to smoke during pregnancy (OR = 5.0; 95% CI = 3.8–6.6; p < 0.001). Previous research has shown that several high-risk activities are associated with a higher likelihood of pregnancy. These activities included the use of tobacco products, drinking alcohol, drug use, and risky sexual behavior [ 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 ].

Teenagers need accurate information about where to go when they need advice and help. Numerous studies have highlighted the benefits of prenatal care in minimizing pregnancy risks [ 9 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Unlike controls, pregnant adolescent girls in our study used prenatal care services less frequently. This was confirmed by a later gestational age at the first visit ( p < 0.001) and a lower number of visits to the doctor during pregnancy ( p < 0.001). This may be a result of a lack of information about the community services offered and the benefits of providing early and routine care. Teenagers may think they are not entitled to prenatal care, or they may choose to keep the pregnancy a secret [ 9 , 11 , 18 ]. Pregnant teenagers often interrupt school attendance, partly because of their participation in prenatal care. If clinic times are compatible with school attendance and medical staff are sensitive to adolescent needs, antenatal visits are more likely to be attended. Therefore, the needs of adolescents must be taken into account when providing prenatal care. However, direct study comparisons are difficult as there are different definitions of appropriate prenatal care. Regardless of how prenatal care is defined, the data suggest that adolescents tend to receive less adequate care than adult women [ 3 , 8 , 14 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Similar findings were obtained by Kassa et al. [ 22 ], who found that the number of antenatal care visits was lower in the teenage group and that doctor visits started later in pregnancy in this group. De Vienne et al. [ 23 ], on the other hand, did not find a difference between younger and older women in the analyzed age categories. Quinlivan and Evans published a study [ 24 ] comparing the outcomes of adolescents attending either a general or a specialist antenatal clinic for teenagers. In adolescent pregnancy clinics, prenatal care was provided by a multidisciplinary team and included social support and thorough infection screening. The rate of preterm births has decreased significantly as a result of the care provided at teen pregnancy clinics. According to the authors, the key strategies were the prevention of ascending infections of the genital tract and the provision of comprehensive treatment for teenagers. Healthcare professionals should be aware that teenage pregnancies are high-risk pregnancies and educate young women about the value of prenatal care and frequent antenatal visits.

In our study, preterm births were more common among pregnant teenage mothers than in controls ( p = 0.004), which is similar to previous studies [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. Due to the fact that preterm birth is a complex pregnancy problem, it is complicated to identify the exact cause. According to Debiec et al. [ 17 ], preterm birth is more common in teenagers who receive insufficient prenatal care, which supports the hypothesis that poor prenatal care is a risk factor for preterm birth. However, Chen et al. [ 4 ] point out that the risk of preterm birth persisted even in women who received adequate prenatal care. Yadav et al. [ 10 ] found that preterm birth was significantly more common in teenagers. According to them, the rise might be attributed to biological immaturity and socioeconomic deprivation. Clinically indicated preterm births may be the result of medical conditions such as intrauterine growth restriction or spontaneous labor. Both spontaneous preterm birth and intrauterine growth restriction are associated with maternal malnutrition, and there is strong evidence linking both conditions to maternal smoking during pregnancy [ 13 , 18 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. Adolescent mothers are more likely to deliver preterm due to gynecological immaturity (such as a short cervix [25 mm] and a small uterine volume) and susceptibility to subclinical infections. Other studies suggest that these risks are related to biological immaturity in adolescent females and are not related to social deprivation, smoking, or inadequate prenatal care [ 27 , 36 , 37 ].

In this study, the percentage of low birth weight in infants born from adolescent mothers was higher than in mothers who gave birth in adulthood ( p < 0.001), which is similar to previous studies [ 23 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 38 , 39 ]. It is thought that growing adolescents may compete with the fetus for resources, which might hinder fetal development and lead to low-birth-weight newborns or newborns that are small for their gestational age [ 40 ]. Marvin-Dowle et al. [ 40 ] conducted research in England among women aged 19 years and 20–34 years to examine the relationship between maternal and newborn outcomes in teenage women. Extremely low birth weight was found to be significantly more common in the teenager group compared with the control group.

Extremely underweight newborns have a higher risk of death within the first few months of life [ 12 ] as well as long-term problems with their physical and cognitive development [ 9 , 11 ]. Extremely low birth weight was not more common in our study cohort of adolescent mothers ( p = 0.246).

The term Apgar, or appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration, was created by Doctor Virginia Apgar. This score is a simple method for evaluating neonates one and five minutes after birth. A newborn’s Apgar score is determined by several variables, including color, heart rate, reflexes, muscle tone, and breathing. Scores for each item range from 0 (zero), 1, or 2, with a total score of 7 to 10 considered good [ 41 ]. No significant difference in the low Apgar score between adolescent and adult pregnancies was found when compared with hospital-based retrospective cohort research in Nepal by Yadav et al. [ 10 ]. Due to several sociodemographic, obstetric, and dietary factors, low Apgar scores occur more frequently in teenage pregnancies than in adult pregnancies [ 3 , 22 ]. In a study conducted over 6 years in Japan with 30,831 women under the age of 25 who were pregnant with a singleton, Ogawa et al. [ 29 ] examined the relationship between adolescent pregnancy and adverse outcomes. They found that low Apgar scores were significantly more common among adolescent mothers than among mothers aged 20 to 24 [ 29 ]. Low Apgar scores are associated with infant complications such as breathing difficulties, feeding problems, hypothermia, and seizures [ 42 ]. Low Apgar scores at five minutes correlate with mortality and may indicate a higher likelihood of cerebral palsy [ 41 ]. In our study, the difference in the prevalence of low Apgar scores between adolescent mothers and the control group was confirmed only when the Apgar score was evaluated after the first minute ( p = 0.003).

The development of social policy can be improved by having a thorough understanding of all these socioeconomic factors that influence teen pregnancy.

The first and most important step in strategies to reduce adolescent pregnancies and associated poor neonatal outcomes should be to “prevent it”. Measures to reduce the prevalence of teenage pregnancy also include increasing the importance of education. Although there are many different techniques to prevent a young girl from becoming pregnant, sexual abstinence is the only one that is 100% successful. This approach is the only one that ensures zero pregnancy risk and safeguards the adolescent from contracting any STDs. It is important to make teenagers aware of the responsibility that comes with sexual activity. The more information teenagers receive about this topic, the higher the chance that they will behave cautiously.

Teenagers should be educated about the negative consequences of teenage pregnancy, especially by their parents and at school. Building adolescents’ knowledge, skills, resilience, and aspirations through relationships and education helps them delay sexual activity until they are ready; enjoy healthy, consensual relationships; and use family planning methods. Schools may play a role by encouraging students to make mature decisions about their sex and by disseminating the knowledge needed to prevent adolescent pregnancy.

Teenagers are more likely to have their first sexual experience later in life if they and their parents have open discussions about relationships and sexual health from a young age. When parents spend time discussing sex and family planning with their children, they can have a significant impact on their decisions. Some parents have trouble talking about this topic. The barriers to parental communication include embarrassment, concern that discussion may encourage early sexual activity, and uncertainty about how to properly answer questions. Parents and all practitioners who come into contact with young people therefore need guidance on how to talk to them.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, pregnancies in adolescents should be considered high-risk pregnancies. It is necessary to emphasize the need for comprehensive prenatal care for pregnant adolescent children because insufficient prenatal care can be harmful to both the mother and her fetus. Promoting early and thorough prenatal care is a key strategy if adolescent pregnancy outcomes are to be improved. Addressing teen pregnancy also requires a major effort by families, service providers, schools, faith-based and community organizations, recreation centers, policymakers, and youth. Teenagers should be educated about the negative consequences of teenage pregnancy, especially by their parents and at school. Our results confirm the relatively high prevalence of pregnant adolescent girls who smoked. Education should therefore also focus more on the risks associated with the use of substances during pregnancy.

The most important elements in preventing unwanted teenage pregnancies are a functional and stable family, good relations between parents, and good relations between parents and children. Parents should be the main source of information about sex. Adolescent pregnancy is not only a medical problem but also a social and societal problem, so society also plays an important role in preventing unwanted pregnancies, spreading awareness among young people, and holding them accountable for their actions.

6. Limitation

The conclusions of this study must be interpreted in light of limitations in the dataset and study design. For example, this study cannot adequately control for such factors as infectious exposure and drug use, which may differ between the groups.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants KEGA No. 008UPJŠ-4/2020, KEGA 010UPJŠ-4/2021 of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovakia and 015UK-4/2022. We also thank the directory board of the Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics at Louis Pasteur University Hospital in Košice for assistance with organization of sample collection at the hospital wards.

Author Contributions

J.D., K.R. and P.U. designed the project; J.D. and A.H. participated in data analysis; J.D. was responsible for interpretation and writing of the final version for publication; K.R. and E.D. were responsible for funding acquisition and project administration; J.D. performed the literature search and drafted sections of the manuscript; K.R., E.D. and Ľ.A. provided critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Louis Pasteur University Hospital, Košice, Slovakia, 2019/EK/2014.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 25 May 2016

Teenage pregnancy: the impact of maternal adolescent childbearing and older sister’s teenage pregnancy on a younger sister

- Elizabeth Wall-Wieler 1 ,

- Leslie L. Roos 1 &

- Nathan C. Nickel 1

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume 16 , Article number: 120 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

699k Accesses

36 Citations

46 Altmetric

Metrics details

Risk factors for teenage pregnancy are linked to many factors, including a family history of teenage pregnancy. This research examines whether a mother’s teenage childbearing or an older sister’s teenage pregnancy more strongly predicts teenage pregnancy.

This study used linkable administrative databases housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP). The original cohort consisted of 17,115 women born in Manitoba between April 1, 1979 and March 31, 1994, who stayed in the province until at least their 20 th birthday, had at least one older sister, and had no missing values on key variables. Propensity score matching (1:2) was used to create balanced cohorts for two conditional logistic regression models; one examining the impact of an older sister’s teenage pregnancy and the other analyzing the effect of the mother’s teenage childbearing.

The adjusted odds of becoming pregnant between ages 14 and 19 for teens with at least one older sister having a teenage pregnancy were 3.38 (99 % CI 2.77–4.13) times higher than for women whose older sister(s) did not have a teenage pregnancy. Teenage daughters of mothers who had their first child before age 20 had 1.57 (99 % CI 1.30–1.89) times higher odds of pregnancy than those whose mothers had their first child after age 19. Educational achievement was adjusted for in a sub-population examining the odds of pregnancy between ages 16 and 19. After this adjustment, the odds of teenage pregnancy for teens with at least one older sister who had a teenage pregnancy were reduced to 2.48 (99 % CI 2.01–3.06) and the odds of pregnancy for teen daughters of teenage mothers were reduced to 1.39 (99 % CI 1.15–1.68).

Although both were significant, the relationship between an older sister’s teenage pregnancy and a younger sister’s teenage pregnancy is much stronger than that between a mother’s teenage childbearing and a younger daughter’s teenage pregnancy. This study contributes to understanding of the broader topic “who is influential about what” within the family.

Peer Review reports

The risks and realities associated with teenage motherhood are well documented, with consequences starting at childbirth and following both mother and child over the life span.

Teenage births result in health consequences; children are more likely to be born pre-term, have lower birth weight, and higher neonatal mortality, while mothers experience greater rates of post-partum depression and are less likely to initiate breastfeeding [ 1 , 2 ]. Teenage mothers are less likely to complete high school, are more likely to live in poverty, and have children who frequently experience health and developmental problems [ 3 ]. Understanding the risk factors for teenage pregnancy is a prerequisite for reducing rates of teenage motherhood. Various social and biological factors influence the odds of teenage pregnancy; these include exposure to adversity during childhood and adolescence, a family history of teenage pregnancy, conduct and attention problems, family instability, and low educational achievement [ 4 , 5 ].

Mothers and older sisters are the main sources of family influence on teenage pregnancy; this is due to both social risk and social influence. Family members both contribute to an individual’s attitudes and values around teenage pregnancy, and share social risks (such as poverty, ethnicity, and lack of opportunities) that influence the likelihood of teenage pregnancy [ 6 , 7 ]. Having an older sister who was a teen mom significantly increases the risk of teenage childbearing in the younger sister and daughters of teenage mothers were significantly more likely to become teenage mothers themselves [ 8 , 9 ]. Girls having both a mother and older sister who had teenage births experienced the highest odds of teenage pregnancy, with one study reporting an odds ratio of 5.1 (compared with those who had no history of family teenage pregnancy) [ 5 ]. Studies consistently indicate that girls with a familial history of teenage childbearing are at much higher risk of teenage pregnancy and childbearing themselves, but methodological complexities have resulted in inconsistent findings around “parent/child sexual communication and adolescent pregnancy risk” [ 10 ]. A review of family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk found risk factors to include living in poor neighborhoods and families, having older siblings who were sexually active, and being a victim of sexual abuse [ 10 ]. Research around the impact of sister’s teenage pregnancy has been limited to mostly qualitative studies using small samples of minority adolescents in the United States [ 5 , 11 ].

To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the impact of an older sister’s teenage pregnancy on the odds of her younger sister having a teenage pregnancy, and compared this effect with the direct effect of having a mother who bore her first child before age 20. By controlling for a variety of social and biological factors (such as neighborhood socioeconomic status, marital status of mother, residential mobility, family structure changes, and mental health), and the use of a strong statistical design—propensity score matching with a large population-based dataset—this study aims to determine whether teenage pregnancy is more strongly predicted by having an older sister who had a teenage pregnancy or by having a mother who bore her first child before age 20.

The setting of this study, Manitoba, is generally representative of Canada as a whole, ranking in the middle for several health and education indicators [ 12 , 13 ]. At the time of the 2011 Census, approximately 1.2 million people resided in Manitoba, with more than half (783,247) living in the two urban areas, Winnipeg and Brandon [ 14 ]. Teenage pregnancy rates in Manitoba exceed the national; in 2010 teenage pregnancy rates in Canada were 28.2 per 1000, in Manitoba the rate was 48.7 per 1000 [ 15 ]. The Manitoba teen pregnancy rates in 2010 were slightly lower than rates in England and Wales (54.6 per 1000), and the United States (57.4 per 1000) [ 16 , 17 ].

The Manitoba Population Health Research Data Repository contains province-wide, routinely collected individual data over time (going back to 1970 in some files), across space (with residential location documented using six digit postal codes), for each family (with changes in family structure recorded every 6 months) and for each resident. Health variables are measured continuously from physician claims and hospital abstracts (as long as an individual remains in Manitoba) [ 18 ].

A research registry identifies every provincial resident, with information on births, arrival and departure dates, and deaths created from the provincial health registry and coordinated with Vital Statistics files. Given approximately 16,000 births annually, follow-up (about 74 % over 20 years) is comparable to that in the largest cohort studies based on primary data [ 19 ]. Previous research using similar data shows the results are not biased by individuals leaving the province or dying. Information on data linkage, confidentiality/privacy, and validity of the datasets used have been described elsewhere [ 20 – 22 ]. Children are linked to mothers using hospital birth record information; the mother was noted in essentially all cases [ 23 ]. Sisters were defined as having the same biological mother.

The cohort consists of women who were born in Manitoba between April 1, 1979 and March 31, 1994, stayed in the province until at least their 20 th birthday, had at least one older sister, and had no missing values on key variables. In this study, teenage pregnancies are defined as those between the ages of 14 and 19; pregnancies prior to age 14 were excluded due to low numbers and for comparability to other studies. For this reason, families in which at least one sister had a pregnancy before age 14 were removed (34 families). To address threats of independence, when a family had more than one younger sister (more than two daughters), one younger sister was randomly selected. Figure 1 diagrams the selection trajectory for the 17,115 individuals selected—boxes in bold indicate the included cohort. At age 14, just over 85 % of girls in this cohort were living in the same postal code as at least one older sister.

Cohort selection

Teenage pregnancy was defined as having at least one pregnancy between the ages of 14 and 19 (inclusive). A pregnancy is defined as having at least one hospitalization of with a live birth, missed abortion, ectopic pregnancy, abortion, or intrauterine death, or at least one hospital procedure of surgical termination of pregnancy, surgical removal of ectopic pregnancy, pharmacological termination or pregnancy or intervention during labour and delivery. Pregnancy status was determined by ICD-9-CM codes (for diagnoses before April 1, 2004), ICD-10-CA codes (for diagnoses on or after April 1, 2004), and Canadian Classification of Health Intervention (CCI) codes in the hospital discharge abstract database [ 24 ]. Appendix 1 presents specific codes used to determine pregnancy status.

Independent variable

The independent variables of interest were whether an individual had an older sister with a teenage pregnancy (defined for all sisters as described above) and whether an individual’s mother bore her first child before age 20.

Based on an extensive literature review and availability of information in the database, several key variables describing neighborhood, maternal, and individual characteristics were included [ 4 , 25 ]. Covariates measure characteristics in the younger sister’s life before age 14. Neighborhood socioeconomic status at age 14 was measured by the Socioeconomic Factor Index (SEFI) (higher SEFI score corresponds with lower socioeconomic status), which is generated using Manitoba (Statistics Canada) dissemination areas [ 26 ]. This index combines neighborhood information on income, education, employment, and family structure. These neighborhoods typically include between 400 and 700 urban individuals and are somewhat larger in rural areas. Neighborhood location at age 14 was divided into urban (Winnipeg and Brandon), rural south (South Eastman, Central, and Assiniboine Regional Health Authorities), and rural mid/north (North Eastman, Interlake, Parkland, Nor-Man, Churchill, and Burntwood Regional Health Authorities). The maternal characteristic included is marital status at birth of child. An individual’s number of older sisters was also accounted for.

Three time-varying covariates between birth and age 13 for the younger sister were included in the study- mental health conditions, residential mobility, and family structure change. These variables can occur at specific points in time and the timing of their occurrence can differ across individuals. Mental health is defined using the Johns Hopkins University Adjusted Clinical Group (ACG) software; this software groups medical and hospital diagnoses over the course of a year into 27 Major Expanded Diagnostic Clusters (MEDCs) [ 27 ]. If for 1 year between birth and age 13, the diagnoses an individual received fell into the ‘Mental Health’ MEDC, that individual was categorized as having mental health conditions before age 13. Residential mobility was measured by at least one residential move (defined by change in six digit postal code) between birth and age 13. At least one change in family structure (parental divorce, death, marriage, remarriage) between birth and age 13 was noted as ‘family structure change’.

Low educational achievement has been linked to an increased risk of teenage pregnancy [ 28 ]. The earliest measure of educational achievement available is the Grade 9 Achievement Index, which was built on a technique developed by Mosteller and Tukey using enrollment files, course grades, and the provincial population registry [ 29 , 30 ]. As some of the individuals in this cohort experience their first pregnancy before completing grade 9, this covariate is only appropriate for girls having their first pregnancy after their 16 th birthday. Sensitivity testing was done with this population to determine how strongly educational achievement affected the odds of the variables of interest.

Analytic approach

The relationship between pregnancy during one’s teenage years and having an older sister who became pregnant during adolescence or having a mother who bore her first child as a teenager is confounded by many measured and unmeasured characteristics. We adjusted for these confounding characteristics using 2:1 propensity score matching [ 31 ]; two controls were matched with every case as this “will result in optimal estimation of treatment effect [ 32 ]”. Propensity score matching both enables adjustment for several confounders simultaneously and facilitates diagnostic tests to identify whether the adjustment strategy created comparable exposure groups (i.e., whether women with and without an older sister who got pregnant during adolescence are similar on observed characteristics) [ 31 ]. Logistic regression models were used to calculate propensity scores for two responses—the predicted probability of having an older sister having a teenage pregnancy and the predicted probability of having a mother bearing her first child before age 20. For each model, we investigated the comparability of our two groups—those with and without an older sister having a teenage pregnancy, and those with and without a mother who bore her first child as a teenager—using two diagnostics. A kernel density plot verified that the distribution of propensity scores in our two groups overlapped [ 33 ]; each case was matched to two controls using greedy matching [ 34 ]. Second, after matching, the balance of the covariates was assessed using standard differences and t-tests. Covariate balance was checked by t-statistics calculated for the standardized differences between cases and controls for each covariate before and after matching. Any point outside of the two vertical dotted lines signified a statistically significant difference between the cases and controls on that covariate (at p = 0.05) (Figs. 2 and 3 ).

Checking covariate balance of older sister’s teenage pregnancy status

Checking covariate balance of mother’ teenage mom status

Conditional logistic regression analysis of the matched cohorts examined the impact of an older sister’s teenage pregnancy and of a mother’s teenage childbearing on teenage pregnancy. Sensitivity analysis helped assess the validity of the assumption of no unobservable confounders, and assessed how strong the influence of unobserved covariates would have to be in order to nullify our findings [ 35 , 36 ]. The lower limit of the 99 % confidence interval (selected to be more conservative) was used to determine the threshold unobserved covariates would have to reach to void the observed relationship.

Impact of older sister having a teenage pregnancy

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics of the covariates and outcome variables. Of the girls having an older sister with a teenage pregnancy, 40.4 % had a teenage pregnancy. This is significantly higher than the 10.3 % teenage pregnancy rate among those not having an older sister with a teenage pregnancy.

The covariates, in general, accord with social stratification theory [ 37 ]. Teens with an older sister having a teenage pregnancy were also more likely to have been born to an unmarried mother and have a mother who herself was a teenage mother (43 % versus 14 %). At age 14, approximately 42 % of those whose older sister had a teenage pregnancy lived in Rural Mid/Northern Manitoba; only 22 % of those whose older sister did not have a teenage pregnancy lived in this region at age 14. Lower teenage pregnancy was associated with residence in relatively prosperous southern Manitoba. Individuals with older sisters having teenage pregnancies were more likely to live in lower socioeconomic status neighborhood (higher SEFI scores at age 14) with higher rates of residential mobility (68 % vs 59 %), family structure change (28 % vs 16 %), and mental health issues (19 % vs 16 %).

After propensity score matching (on all variables in Fig. 2 ), the final sample consisted of 1873 cases and 3746 controls (1:2); a total of 1618 cases and 9878 controls were excluded from the analysis. T-statistics calculated for each covariate before and after matching to check for covariate balance; all covariates differed significantly in the unmatched sample and balanced in the matched sample (Fig. 2 ).

The final conditional logistic regression model indicates the odds of becoming pregnant before age 20 for those having an older sister with a teenage pregnancy to be 3.38 (99 % CI 2.77–4.13) times greater than for girls whose older sister(s) did not have a teenage pregnancy (Table 3 ).

Impact of mother’s teenage childbearing

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics of the covariates and outcome variables. Of the girls having a teenage mother, 39.4 % had a teenage pregnancy. This is significantly higher than the 13.1 % teenage pregnancy rates among those whose mother bore her first child after age 19.

After propensity score matching (on all variables in Fig. 3 ), the final sample consisted of 1522 cases and 3044 controls (1:2); a total of 659 cases and 11890 controls were excluded from the analysis. T-statistics calculated for each covariate showed all covariates to differ significantly in the unmatched sample and to balance in the matched sample (Fig. 3 ).

The final conditional logistic regression model indicates that the odds of becoming pregnant before age 20 for those whose mother had her first child before age 20 are 1.57 (99 % CI 1.30–1.89) times greater than for girls whose mother had her first child after age 19 (Table 3 ). Thus, the impact of being born to a mother having her first child before age 20 on teenage pregnancy is much less than that of an older sisters’ teenage pregnancy.

Sensitivity analysis and limitations

With the confidence interval for the first model (examining the association between an older sister’s teenage pregnancy and a younger sister’s teenage pregnancy) ranging between 2.77 and 4.13, to attribute the higher rates of teenage pregnancy to unmeasured confounding rather than to an older sisters’ teen pregnancy status, that covariate would need to generate more than a 2.8-fold increase in the odds of teenage pregnancy and be a near perfect predictor of teenage pregnancy. In the second model (assessing the association between a mother’s teenage childbearing and a younger sister’s teenage pregnancy), the 99 % confidence interval was 1.30 to 1.89; unobserved covariates would need to produce a much smaller increase in odds of teen pregnancy to nullify this finding.

Although linkable administrative data have significant advantages, some important predictors are lacking. Information on involvement with Child and Family Services (CFS) and parental use of income assistance have recently been added to the Manitoba databases, but do not cover the cohort used here. While having a teenage mother and becoming a teenage mother have both been linked to involvement with CFS, in 2001 less than two percent of children under age 18 were in care [ 38 , 39 ]. A variable available (and applicable) for a subpopulation is educational achievement, which is highly correlated with both involvement with CFS and parental welfare use [ 40 ]. These two new measures would likely explain little additional variance in teenage pregnancy. Appendix 2 describes the cohort and propensity score matching for this additional analysis, comparing these findings with the original results in Table 3 . Educational attainment is measured using the Grade 9 Achievement Index, a standardized measure taking into account the number of courses completed in Grade 9 and the average marks of those courses. After adjusting for educational achievement, the odds of teenage pregnancy for teens with at least one older sister who had a teenage pregnancy were reduced to 2.48 (99 % CI 2.01–3.06) and the corresponding odds for teen daughters of teenage mothers were lowered to 1.39 (99 % CI 1.15–1.68).

The rate differences of teenage pregnancy were similar for those whose older sister had a teenage pregnancy (40.4 per 100 - 10.3 per 100 = 30.1 per 100) and for those whose mother bore her first child before age 20 (39.4 per 100 - 13.1 per 100 = 26.3 per 100). After propensity score matching on a series of variables, the odds of becoming pregnant for a teenager were much higher if her older sister had a teenage pregnancy than if her mother had been a teenage mother. For both older sisters’ teenage pregnancy and mother’s teenage childbearing, the odds in this study are lower than those reported elsewhere; this is likely due to the larger sample size, more rigorous methods, and inclusion of important predictors.

Several examinations of family histories in the literature show older sisters to have the greatest influence on a younger sister’s odds of having a teenage pregnancy. Controlling for family socioeconomic status, maternal parenting, and sibling relationships, teens with an older sister who had a teenage birth were 4.8 times more likely to have a teenage birth themselves; these odds increased to 5.1 if both the older sister and mother had a teenage birth [ 11 ]. Four older studies estimated the rate of teen pregnancy to be between 2 and 6 times higher for those with older sisters having a teenage pregnancy [ 41 ]. This work focused primarily on young black women in the United States and controlled for limited confounders (aside from race and age). None of the previous studies examining the impact of an older sister’s teenage pregnancy controlled for mother’s teenage childbearing or time-varying factors before age 14 (mental health, residential mobility, family structure changes); this research probably overestimated the relationship between sisters’ teenage pregnancy status.

The mechanisms driving the relationship between an older sister’s teenage pregnancy and the pregnancy of a younger adolescent sister have been examined through approaches based on social learning theory, shared parenting influences, and shared societal risk [ 41 ]. Bandura’s social learning theory indicates that “most human behavior is learned observationally through modeling: from observing others one forms an idea of how new behaviors are performed, and on later occasions this coded information serves as a guide for action” [ 7 ]. When sisters live in the same environment, seeing an older sister go through a teenage pregnancy and childbirth may make this a more acceptable option for the younger sister [ 11 ]. Not only do both sisters have the same maternal influence that may affect their odds of teenage pregnancy, having an older sister who is a teenage mother may change the parenting style of the mother. Mothers involved in parenting of their teenage daughters’ child may have “supervised their children less, communicated with their children less about sex and contraception, and perceived teenage sex as more acceptable when the older daughter’s status changed from pregnant to parenting” [ 42 ]. Finally, both sisters share the same social risks, such as poverty, ethnicity, and lack of opportunities, that increase their chances of having a teenage pregnancy [ 42 ].

Having a mother bearing her first child before age 20 was a significant predictor for teenage pregnancy. We found daughters of teenage mothers to be 51 % more likely to have a teenage pregnancy than those whose mothers were older than 19 when they bore their first child. This is quite close to the 66 % increase found by Meade et al (2008), who controlled for many of the same variables except having an older sister with a teenage pregnancy, and the time-varying covariates of family structure change, mental health conditions, and residential mobility. Meade et al. [ 9 ] did adjust for school performance; in the adjusted sub-sample, the odds ratio reduced to 1.34, indicating a 34 % increase in teenage pregnancy.

Intergenerational teenage pregnancy may be influenced by such mechanisms as “biological heritability, intergenerational transmission of values regarding family, the mother’s level of fertility, the indirect impact of socioeconomic and family environment through educational deficits or low opportunity or aspirations, and directly through the mother’s role modeling” [ 43 ]. Women bearing their first child in their adolescence are more likely to pass on “risky” characteristics, which could produce negative outcomes in their offspring [ 44 ]. Another mechanism identified as contributing to intergenerational teenage pregnancy is that daughters of teenage mothers have an increased internalized preference for early motherhood, have low levels of maternal monitoring, and are thus more likely to become sexually active at a young age and engage in unprotected sex [ 44 ]. The influence of a mother’s teenage pregnancy therefore works through the environment created and parenting style assumed as a result of a mother’s teenage childbearing.

The use of administrative data to conduct health services research has some significant advantages and limitations. Administrative data from a large birth cohort have higher levels of accuracy is not depending on recall (such as in retrospective surveys) and is ideal for examining risk factors over time due to the longitudinal follow-up [ 45 ]. These data—with a large N and a number of covariates—are well-suited for propensity scoring. A significant limitation (shared with almost all observational studies) is that certain covariates and mediating effects are unobservable due to lack of information. The data can only capture recorded variables; for example, only individuals seeking mental health treatment will receive a diagnosis, which may not be include all individuals with mental health conditions [ 46 ]. Sensitivity testing addresses this limitation, but such covariates might well have impacted study results. As mentioned above, not adjusting for involvement with child protective services (such as CFS) is a limitation. Although the number of teenage girls involved with CFS is relatively small, they may not be interacting with their mother or older sister on a regular basis and thus are less likely to model themselves after their family members. The availability of an educational predictor was an identified limitation. To account for the impact of educational achievement in our full cohort, educational outcomes would need to be available for everyone for grade 7 at the latest (as almost all teenage pregnancies occur after grade 7). Since educational achievement generally remains quite similar from year to year—grade 9 achievement is likely to be quite similar to grade 7 achievement [ 30 ]; this reduced odds ratio may better estimate the true odds. In several years, such variables can be incorporated into models of teenage pregnancy. Additionally, we were unable to identify Aboriginal individuals; this is a limitation as teenage pregnancy rates are more than twice as high in the Aboriginal population than in the general population [ 47 ]. Family and peer relationships, social norms, and cultural differences will likely never be measured through administrative data; limiting the degree to which these confounders can be controlled for.

Conclusions

This paper contributes to understanding of the broader topic “who is influential about what” within the family. The teenage pregnancy risk seen in younger sisters when older sisters had a teenage pregnancy appears based on the interaction with that sister and her child; the family environment experienced by the siblings is quite similar. Much of the pregnancy risk among teenage daughters of mothers bearing a child before age 20 seems likely to result from the adverse environment often associated with early childbearing. Given that an older sister’s teenage pregnancy has a greater impact than a mother’s teenage childbearing, social modelling may be a stronger risk factor for teenage pregnancy than living in an adverse environment.

Abbreviations

Adjusted Clinical Group

Canadian Classification of Health Intervention

Child and Family Services

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, with Canadian Enhancements

Major Expanded Diagnostic Clusters

Manitoba Centre for Health Policy

Socioeconomic Factor Index

Chen XK, Wen SW, Fleming N, Demissie K, Rhoads GG, Walker M. Teenage pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a large population based retrospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:368–73.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kingston D, Heaman M, Fell D, Chalmers B. Comparison of adolescent, young adult, and adult women’s maternity experiences and practices. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1228–37.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hoffman SD, Maynard R. Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs & Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press; 2008.

Google Scholar

Woodward L, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with teenage pregnancy: Results of a prospective study from birth to 20 years. J Marriage Fam. 2001;63:1170–84.

Article Google Scholar

East P, Reyes B, Horn E. Association between adolescent pregnancy and a family history of teenage births. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39:108–15.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Akella D, Jordan M. Impact of social and cultural factors on teen pregnancy. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2011;8:41–62.

Bandura A. Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977.

Ferraro AA, Cardoso VC, Barbosa AP, Da Silva AAM, Faria CA, De Ribeiro VS, Bettiol H, Barbieri MA. Childbearing in adolescence: intergenerational dejà-vu? Evidence from a Brazilian birth cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:149.

Meade CS, Kershaw TS, Ickovics JR. The intergenerational cycle of teenage motherhood: an ecological approach. Health Psychol. 2008;27:419–29.

Miller B, Benson B. Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis. Dev Rev. 2001;21:1–38.

Article CAS Google Scholar

East PL, Slonim A, Horn EJ, Trinh C, Reyes BT. How an adolescent’s childbearing affects siblings’ pregnancy risk: a qualitative study of Mexican American youths. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;41:210–7.

Oreopoulos P, Stabile M, Walld R, Roos L. Short, medium, and long term consequences of poor infant health: An analysis using siblings and twins. J Hum Resour. 2008;43:88–138.

Shanahan M, Gousseau C. Using the POPULIS framework for interprovincial comparison of expenditures on health care. Med Care. 1999;37:JS83–JS100.

Statistics Canada. Focus on geography series, 2011 census. 2014.

McKay A. Trends in Canadian National and Provincial/Territorial teen pregnancy rates: 2001-2010. Can J Hum Sex. 2012;21:161–75.

Office of National Statistics. Conceptions in England and Wales, 2010. Newport, CN: Office for National Statistics; 2012.

Kost K, Henshaw S. U.S. teenage pregnancies, births and abortions. 2014.

Nickel N, Chateau D, Martens P, Brownell M, Katz A, Burland E, Walld R, Hu M, Taylor C, Sarkar J, Goh C, Team TPE. Data resource profile: Pathways to health and social equity for children (PATHS Equity for Children). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:1438–49.

Power C, Kuh D, Morton S. From developmental origins of adult disease to life course research on adult disease and aging: Insights from birth cohort studies. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:7–28.

Ladouceur M, Leslie W, Dastani Z, Goltzman D, Richards J. An efficient paradigm for genetic epidemiology cohort creation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14045.

Roos L, Gupta S, Soodeen R, Jebamani R. Data quality in an information-rich environment: Canada as an example. Can J Aging. 2005;24:153–70.

Roos L, Nicol J. A research registry: Uses, development, and accuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:39–47.

Currie J, Stabile M, Manivong P, Roos L. Child health and young adult outcomes. J Hum Resour. 2010;45:517–48.

Concept: Teenage pregnancy [ http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/viewConcept.php?conceptID=1248 ].

McCall SJ, Bhattacharya S, Okpo E, Macfarlane G. Evaluating the social determinants of teenage pregnancy: A temporal analysis using a UK obstretics database from 1950 to 2010. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:49–54.

Chateau D, Metge C, Prior H, Soodeen R. Learning from the census: The socio-economic factor index (SEFI) and health outcomes in Manitoba. Can J Public Heal. 2012;103 Suppl 2:S23–7.

The Johns Hopkins University. The Johns Hopkins ACG case-mix system (Version 6.0 Release Notes). 2003.

Manlove J. The influence of high school dropout and school disengagement on the risk of school-age pregnancy. J Res Adolesc. 1998;8:187–220.

Mosteller F, Tukey J. Data analysis and regression: a second course in statistics. Reading: Addison-Wesley; 1977.

Roos L, Hiebert B, Manivong P, Edgerton J, Walld R, MacWilliam L, de Rocquigny J. What is most important: Social factors, health selection, and adolescent educational achievement. Soc Indic Res. 2013;110:385–414.

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55.

Austin PC. Statistical criteria for selecting the optimal number of untreated subjects matched to each treated subject when using many-to-one matching on the propensity score. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1092–7.

Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424.

Parsons LS. Reducing Bias in a Propensity Score Matched-Pair Sample Using Greedy Matching Techniques. Cary, NC: Ovation Research Group; 2001.

Jiang M, Foster M, Gibson-Davis C. Breastfeeding and child cognitive outcomes: A propensity score matching approach. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:1296–307.

Rosenbaum P. Observational studies. New York: Springer; 1995.

Book Google Scholar

Singh S, Darroch JE, Frost JJ, the Study Team. Socioeconomic disadvantage and adolescent women’s sexual and reproductive behaviour: The case of five developed countries. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33:251–89.

Jutte D, Roos N, Brownell M, Briggs G, MacWilliam L, Roos L. The ripples of adolescent motherhood: Social, educational and medical outcomes for children of teen and prior teen moms. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10:293–301.

Kusch L: Number of kids in care soars to all-time high. Winnipeg Free Press . Retrieved from http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/number-of-kids-in-care-soars-to-all-time-high-278761011.html . 2014.

Brownell M, Roos NP, MacWilliam L, Leclair L, Ekuma O, Fransoo R. Academic and social outcomes for high-risk youths in Manitoba. Can J Educ. 2010;33:804–36.

East P, Felice M. Pregnancy risk among the younger sisters of pregnant and childbearing adolescents. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1992;13:128–36.

East PL. The first teenage pregnancy in the family: Does it affect mothers’ parenting, attitutes, or mother-adolescent communication? J Marriage Fa. 1999;61:306–19.

Kahn JR, Anderson K. Intergenerational patterns of teenage fertility. Demography. 1992;29:39–57.

Jaffee S, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Why are children born to teen mothers at risk for adverse outcomes in young adulthood? Results from a 20-year longitudinal study. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:377–397.

Jutte D, Roos L, Brownell M. Administrative record linkage as a tool for public health research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:91–108.

Bolton J, Au W, Walld R, Chateau D, Martens P, Leslie W, Enns M, Sareen J. Parental bereavement after the death of an offspring in a motor vehicle collision: A population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;179:177–85.

Murdoch L. Young Aboriginal Mothers in Winnipeg. Winnipeg, MB: Prairie Women’s Health Centre of Excellence; 2009.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Manitoba Health, Active Living and Seniors, or other data providers is intended or should be inferred. Data used in this study are from the Population Health Research Data Repository housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, University of Manitoba and were derived from data provided by Manitoba Health, Active Living and Seniors and Manitoba Education under project #2013/2014-04. All data management, programming and analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.3. Aggregated Diagnosis Groups™(ADGs®) codes were created using The Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Group® (ACG®) Case-Mix System” version 9.

This research has been supported by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research and the Western Regional Training Centre. The funding sources had no involvement in study design, analysis and interpretation of data, in writing the article, and in the decision to submit for publication. None of the authors received any reimbursement for participating in the writing of this paper.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the research repository at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. Access to data is given upon approvals from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board and the Health Information Privacy Committee, and permission from all data providers. More information on access to these databases can be found at http://umanitoba.ca/faculties/health_sciences/medicine/units/community_health_sciences/departmental_units/mchp/resources/access.html .

Authors’ contributions

EW participated in the design of the study, carried out the analysis and drafted the manuscript. LR conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. NN participated in its design and interpretation of results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

EW is a PhD candidate in the Department of Community Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba. LLR is a Distinguished Professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba and a founding director of the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. NCN is a Research Scientist at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study involved secondary analysis of de-identified data files only, with linkages to other files where identifiers have been removed or scrambled. Consent was not obtained from study subjects, as permitted under section 24(3)c of the Personal Health Information Act. Ethics approvals for this project were obtained from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board (reference number 2013-033) and the Health Information Privacy Committee (reference number 2013/2014-04).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Department of Community Health Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Manitoba, 408-727 McDermot Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3E 3P5, Canada

Elizabeth Wall-Wieler, Leslie L. Roos & Nathan C. Nickel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elizabeth Wall-Wieler .

Pregnancy diagnosis codes

Teenage pregnancy is defined as females with a hospitalization with one of the following diagnoses (MCHP, 2013):

○ live birth: ICD-9-CM code V27, ICD-10-CA code Z37

○ missed abortion: ICD-9-CM code 632, ICD-10-CA code O02.1

○ ectopic pregnancy: ICD-9-CM code 633, ICD-10-CA code O00

○ abortion: ICD-9-CM codes 634-637 ICD-10-CA codes O03-O07; or

○ intrauterine death: ICD-9-CM code 656.4, ICD-10-CA code O36.4

Or, a hospitalization with one of the following procedures:

○ surgical termination of pregnancy: ICD-9-CM codes 69.01, 69.51, 74.91; CCI codes 5.CA.89, 5.CA.90

○ surgical removal of extrauterine (ectopic) pregnancy: ICD-9-CM codes 66.62, 74.3; CCI code 5.CA.93

○ pharmacological termination of pregnancy: ICD-9-CM code 75.0; CCI code 5.CA.88; or

○ interventions during labour and delivery, CCI codes 5.MD.5, 5.MD.60

Adjustment for educational achievement

To account for the impact of educational achievement on teenage childbearing, the grade 9 achievement index was adjusted for in a sub-population of individuals who had not had a pregnancy prior to age 16 (Fig. 4 ). As educational achievement was measured using the grade 9 achievement index (which is based on average marks in all classes and the number of credits earned during the school year [ 31 ], individuals had to have at least finished grade 9 before becoming pregnant to use this variable as a predictor.

Cohort adjustment

Older sister’s teenage pregnancy status

After propensity score matching, the final sample consisted of 1721 cases and 3442 controls (1:2). T-statistics were calculated for each covariate before and after matching to check for covariate balance (Fig. 5 ). Any point outside of the two vertical dotted lines signified a statistically significant covariate (at p = 0.05). All covariates differed significantly in the unmatched sample. After matching, the t-statistics of all covariates fell within the non-significant region indicating balance in cases and controls.

Mother's teenage childbearing status

After propensity score matching, the final sample consisted of 1499 cases and 2998 controls (1:2). T-statistics were calculated for each covariate before and after matching to check for covariate balance (Fig. 6 ). Any point outside of the two vertical dotted lines signified a statistically significant covariate (at p = 0.05). All covariates differed significantly in the unmatched sample. After matching, the t-statistics of all covariates fell within the non-significant region indicating balance in cases and controls.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wall-Wieler, E., Roos, L.L. & Nickel, N.C. Teenage pregnancy: the impact of maternal adolescent childbearing and older sister’s teenage pregnancy on a younger sister. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16 , 120 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0911-2

Download citation

Received : 20 January 2016

Accepted : 14 May 2016

Published : 25 May 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0911-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Teenage pregnancy

- Familial influence

- Social modelling

- Intergenerational effects

- Linkable administrative data

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth

ISSN: 1471-2393

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Understanding the Psychological Impacts of Teenage Pregnancy through a Socio-ecological Framework and Life Course Approach

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Pediatrics, Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, University of California, California, San Francisco.

- 2 Department of Pediatrics, Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Adolescent and Young Adult Health National Resource Center, University of California, California, San Francisco.

- 3 The Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies, University of California San Francisco, University of California, California, San Francisco.

- PMID: 34991169

- DOI: 10.1055/s-0041-1741518

The relationship between mental health and teenage pregnancy is complex. Mental health can be both an antecedent and contributing factor to teenage pregnancy and a concurrent factor wherein pregnancy itself can contribute to depression. Expectant and parenting teens (EPT) are faced with the simultaneous challenges of pregnancy and parenting while navigating the developmental tasks of adolescence which increases their risk for mental health problems. In addition, adolescents growing up in stressful community or home situations where their parents experienced depression, further places them and their children at greater risk of repeated patterns over time. However, adverse mental health outcomes are not inevitable. The socio-ecological model combined with a life course perspective provides a framework for understanding the complexity of risk and protective factors at multiple levels that influence knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and other health outcomes later in life and across generations. This approach has important implications for reducing adolescents' risk of an unintended/mistimed pregnancy and improving mental health and other outcomes for EPT. This paper describes the prevalence of mental health problems in EPT and using a socio-ecological framework and life course perspective explains variations in mental health outcome among EPT. Implications for interventions and innovative approaches are also discussed.

Thieme. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.

- Life Change Events

- Mental Health

- Pregnancy in Adolescence* / psychology

- Study protocol

- Open access

- Published: 25 April 2019

Adolescent pregnant women’s health practices and their impact on maternal, fetal and neonatal outcomes: a mixed method study protocol

- Tahere Hadian 1 ,

- Sanaz Mousavi 2 ,

- Shahla Meedya 3 ,

- Sakineh Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi 4 ,

- Eesa Mohammadi 5 &

- Mojgan Mirghafourvand 4

Reproductive Health volume 16 , Article number: 45 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

5 Citations

9 Altmetric

Metrics details

Considering that individuals’ health practices can affect the health of both mothers and babies, this study is designed to: (a) assess adolescent pregnant women’s health practices and their relationship with maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes; (b) explore the perception of adolescent pregnant women about their own health practices; and (c) recommend some strategies to improve adolescent pregnant women’s health practices during pregnancy.

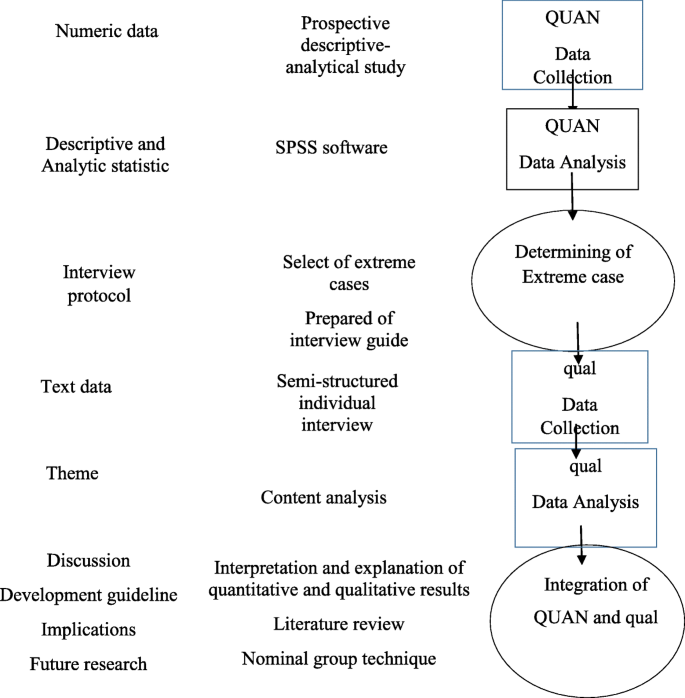

Methods/design

This mixed-method study with the sequential explanatory design has two phases. The first phase (quantitative phase) is a prospective study to assess the adolescent pregnant women’s health practices and its relationship with maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes who live in Tehran, the capital city of Iran. A cluster sampling method will be used to select 316 adolescent pregnant women who visit health centers in Tehran. The second phase is a qualitative study designed to explore the adolescent pregnant women’s perception of important aspects and factors of health practices that can affect their health outcomes. In this phase, purposive sampling and in-depth individual interviews will be conducted for data collection. The conventional content analysis approach will be employed for data analysis. In addition to literature review and nominal group technique, the findings of the qualitative and quantitative phases, will be used to recommend some strategies to support adolescent pregnant women to improve their health practices during pregnancy.

This is the first study looking into health practices in adolescent pregnant women which will be performed via a mixed-method approach, aiming to develop health practices improvement strategies. It is worth noting that there is no strategic guideline in Iran’s health system for improvement of health practices of adolescents. Therefore, it is hoped that the strategy proposed in the current study can enhance health practices of adolescents during pregnancy and ultimately improve their pregnancy and childbirth outcomes.

Ethical code

IR.TBZMED.REC.1397.670.

Plain English summary

Adolescent pregnancy is a public health concern that affects mothers, their children, and the broader community. Pregnancy and childbirth complications remain the leading cause of mortality and morbidity among female adolescents worldwide and can be influenced by lifestyle choices. The rate of adolescent pregnancy is increasing globally and due to recent changes in family planning policies in Iran, it is estimated that adolescent pregnancy will increase in the near future. The current study provides precise information about the health practices in Iranian adolescent pregnant women, and the factors related to them. This study is a mixed-method with the sequential explanatory design has two phases. The first phase (quantitative phase) is a prospective study to assess the adolescent pregnant women’s central and dispersion indices of health practices and its relationship with maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes who live in Tehran, the capital city of Iran. The second phase is a qualitative study designed to explore the adolescent pregnant women’s perception of important aspects and factors of health practices that can affect their health outcomes. The findings of the qualitative and quantitative study in addition to literature review and nominal group technique will be used to recommend some strategies to support adolescent pregnant women to improve their health practice during pregnancy. The strategy proposed by this study may be helpful in promoting health practices in adolescent pregnant women and improving pregnancy and childbirth outcomes in them.