Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Introducing International Relations: Concepts, Theories and Practices

2023, Oxford University Press

Introducing International Relations explores the development of the IR ‘discipline’ through three major essentials: concepts, theories, and practices. Each chapter is structurally organised with respect to detailing concepts, moving thereon to theory, and animated with relevant empirical examples making the connect between theory and practice. Pakistan and the developing world provide the primary reference points for the discussion of practice which is one of the major strengths of the book. In addition, the book challenges students to think methodically, independently, and critically by way of relevant thinking exercises and a summation of key points at the end of individual chapters. This book will not only serve as a useful text for undergraduate and graduate students in universities and colleges but also as a resource for faculty, researchers in think tanks, bureaucrats, candidates appearing in competitive civil service examinations, journalists in print and electronic media, and general readers interested in understanding the nuances that constitute, determine, and shape international relations.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Assessing international relations in undergraduate education

- Teaching and Learning

- Published: 06 May 2020

- Volume 20 , pages 345–358, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Kamil Zwolski 1

2521 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

This paper advocates a holistic approach to assessing international relations in undergraduate education, which revolves around: (a) essays and (b) active learning-related tasks, such as simulation reflective statements/reports and performance. The paper argues that, on the one hand, academic essays are far from irrelevant and it is difficult to overestimate their practical significance. On the other hand, active learning-related tasks are best utilised as a supplementary assessment, expanding the students’ range of transferable skills. The assessment structure advocated in this paper results from a holistic approach to assessment design, which includes teacher’s own experience, familiarity with pedagogical scholarship and input from students. This last element is the least common even though it makes sense to understand how students see their own assessment. To that end, the paper shares the results of a pilot project run at one of the UK universities, which engaged students as partners in rethinking their assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Discourses of artificial intelligence in higher education: a critical literature review

Is Empathy the Key to Effective Teaching? A Systematic Review of Its Association with Teacher-Student Interactions and Student Outcomes

A review of the benefits and drawbacks of high-stakes final examinations in higher education.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This paper aims to serve as one of the reference points for international relations (IR) teachers who are interested in enhancing their teaching practices—or at least making their pedagogical choices more conscious. By no means is it the first contribution of this kind, but it does take stock of the existing teaching and learning literature in IR. The paper also offers original contribution on how to design IR assessment in undergraduate education, which is a slightly underdeveloped topic but one of foremost importance to students. To that end, the paper suggests a holistic framework for assessment design, and in that context, it shares the experience of running a pilot initiative involving politics and IR students at a UK university in shaping how they are assessed. The paper begins by reappraising the scholarship on assessment in IR, although the boundaries are blurred here and most literature deals with teaching and learning IR in general, rather than scrutinising the assessment element. Unsurprisingly, most debates concern innovative approaches to IR teaching and learning, most notably simulations. This paper explores simulations as a potentially beneficial teaching activity and advocates considering this and similar active learning methods in the context of the holistic framework for assessing learning outcomes. In the second section, the paper discusses the proposed holistic approach to designing assessment, which involves building on one’s own experience, catching up with the pedagogical scholarship and working together with students in order to obtain a better understanding of the local learning culture. This last point is further developed in the subsequent section, which reports on the experiment in forming a staff–student partnership for enhancing assessment and feedback practices. The final part of the paper explains the two-tier assessment strategy for undergraduate IR teaching, followed by the limitations of the framework presented in this paper accompanied by possible solutions.

Assessment in IR: state of the art

The question of assessment, including its purpose, format and feedback, has long been at the centre of undergraduate student learning. Not only are the examinations, essays and other summative assignments crucial for awarding degrees, but assessment also has a defining role in shaping the patterns of student life at a university. Several foundational studies in the USA and UK revealed, as early as in the 1970s, the extent to which students care, or even obsess about assessment. Making the Grade (Becker et al. 1968 ) pointed to the so-called GPA (grade point average) perspective, signifying the finding that very few students are genuinely interested in the process of learning, as opposed to strategising about achieving the highest grades. The Hidden Curriculum (Snyder 1971 ) famously exposed the importance, from the students’ perspective, of the informal rules about navigating the landscape of studying for a degree. Finally, Up To the Mark: A Study of the Examination Game (Miller and Parlett 1974 ) famously identified students as cue-seekers, cue-conscious or cue-deaf, depending on how well attuned they are to what they think is actually expected in assessment.

All those studies, together with the plethora of subsequent publications, point to the fact that students care great deal about assessment. In this context, it is rather surprising that almost no academic publications focus on how to assess IR in higher education. This absence may also affect other academic subjects, but what makes it interesting in IR is the fact that there is substantive literature on the teaching and learning of IR as such. Almost all that literature, however, revolves around innovative methods for engaging teaching delivery, with the bulk of analysis focusing on simulations (e.g. Kaunert 2009 ). This emphasis on simulations is hardly surprising. After all, nation states serve as a point of departure, as well as remain the focal point throughout the entire IR module delivery. Even when the overarching argument is that states are not the only meaningful actors in IR, concepts such as globalisation or global governance are still considered against the core notion of sovereign nation states. Just like the nation states, individual students possess different qualities, enjoy some degree of autonomy and are constrained and enabled by a variety of structural and individual “variables”.

Consequently, simulations can offer students a glimpse into the “real” world of international politics, bringing the more abstract contents of an IR module to live. Still, setting up and running simulations in a way which supports student learning and learning objectives are far from straightforward and involve risks. For example, one key question concerns evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of available simulation models, such as Statecraft. Statecraft is a commercial, ready-made and fully online simulation of international politics, making strides into IR classrooms around the world (Carvalho 2014 ; Epley 2016 ; Linantud and Kaftan 2018 ; Raymond 2014 ; Saiya 2016 ). In module evaluations, students repeatedly say that Statecraft is fun and engaging (Raymond 2014 ), but it is notoriously difficult to confirm its learning–enhancing quality (Epley 2016 : 214–215). Other possible simulation designs involve adapting the traditional Diplomacy (Mattlin 2018 ) board game or placing students in a hypothetical scenario of a Zombie attack (Horn et al. 2015 ).

While simulations represent the most popular form of active learning activities in IR classes, there are other non-standard techniques intended to boost student engagement and understanding. Among those, films are on the rise, with some classes combining the classical features (e.g. Duck Soup from 1933 or All Quiet on the Western Front from 1930) with more recent releases, such as Lord of the Rings and 300 (Engert and Spencer 2009 ; Simpson and Kaussler 2009 ; Valeriano 2013 ). Other, less common delivery techniques involve civic engagement and service learning (Glazier 2015 ), as well as teaching IR through arts (Ramel 2018 ) and even dance (Rösch 2018 ). While all of these in-class teaching activities may truly help to engage students and render abstract concepts more accessible, there is no evidence that active learning activities mitigate the “hidden curriculum” effect, which prompts students to strategise in a way to neglect those aspects of learning which are perceived as not directly relevant to assessment. If anything, modern students may be even more oriented towards outcomes as opposed to the process of learning than those attending universities in the 1960s and 1970s. The discussion whether this process of instrumentalisation of university studies is right, or how to change it, goes far beyond the scope of this paper. The fact is that modern universities act as if assessment is the cornerstone of studying for a degree, as indicated by the amount of time and resources allocated to monitor the “quality” of assessment and decide on student assessment/degree outcomes. At the same time, students’ perceptions about the importance of “results” are often shaped even before they come to the university by stories they hear from their parents and their understanding of what it takes to build a successful professional life. Consequently, there are good reasons for university assessment to be thought-through, seamlessly integrated into our understanding of what kinds of knowledge and skills our students should acquire.

Some of the rare contributions on assessment in IR focus on measuring student performance in simulations (Kollars and Rosen 2013 ; Raymond and Usherwood 2013 ), with the notable exception of the paper arguing for short paper assignments in classes (Mcmillan 2014 ). Raymond and Usherwood make an interesting point on the limits of reflective statements, widely used in simulation exercises (notably in Statecraft), which ask students to reflect on their simulation experience and link it to the theoretical contents of the module. The authors note that drawing any definite conclusions about student learning progress based on their reflective statements is unjustified, citing literature questioning how accurately we can recreate all that happened in the past (including causal links) (Raymond and Usherwood 2013 : 160–61). Kollars and Rosen, on the other hand, list the benefits of assessment through simulations. One of the alleged benefits is that simulations allow developing a better understanding of students’ true abilities because they allow observing student progress over a longer period. In contrast, examinations may induce stress, which may cause otherwise good students to produce poor results (Kollars and Rosen 2013 : 153). Finally, McMillan stresses the advantages of short paper assignments over longer research papers, arguing that the former can serve the same purposes as the latter, but short assignments come with a plethora of other benefits, such as closer links with the type of writing students will be doing in their jobs (McMillan 2014 : 109–10). The purpose of this paper is more encompassing. Rather than evaluating assessment options for active learning activities, this paper suggests a comprehensive framework for assessing IR in undergraduate education. An integral part of the framework itself, however, is the method underpinning it. The following section explains the holistic method, which informed the two-tier IR assessment strategy introduced later in this paper.

A holistic method for assessment design

In this paper, I argue that a well thought-through assessment strategy should, ideally, rest on three components: experience, some knowledge of the relevant pedagogical literature and student engagement. Experience and theoretical expertise pertain to the classical distinction between knowing how and knowing what. While the latter refers to our knowledge of theories and principles, the former “rests on bodily experience and practice: it is knowledge within the practice instead of behind the practice” (Pouliot 2008 : 267). Of course, this distinction is ideal, and our understanding of assessment is likely underpinned by some theoretical knowledge. What I propose is to make the distinction between experience and theoretical expertise explicit in our thinking about assessment, even if the boundaries between the two are blurred in our professional development. For example, it is established practice to offer graduate teaching assistants some brief pedagogical training to prepare them for teaching and marking. In the UK context, it has also become common for universities to require their early-career staff to acquire professional recognition through the fellowship scheme of the Higher Education Academy (now Advance HE). Both modes of learning, through acquiring theoretical knowledge and through practice, have their own place in developing effective assessment strategies.

The final component concerns student engagement. There are different forms of engaging students in discussions on assessment and feedback, ranging from ad hoc consultations to institutionalised channels for working with students in partnership. Conversely, there is also a variety of areas suitable for staff–student partnership schemes, including (a) learning, teaching and assessment; (b) curriculum design and pedagogy; (c) subject-based research; and (d) scholarship of teaching and learning (Healey et al. 2014 ). Those areas often overlap, as they do in my own initiative, which I will now briefly outline. In the academic year 2018/2019, I launched a pilot project intended to engage undergraduate students in my department, across all 3 years, in a sustained and meaningful discussion on assessment and feedback. My intention was not merely to elicit information from students on how they would like to be assessed. Instead, I framed the initiative as a way to enhance our learning community, which implied that the learning process was going to take place both ways (as it did) (Healey et al. 2014 : 25–35).

For implementation, I relied on several online platforms in order to make the initiative flexible. Specifically, the Microsoft Teams collaborative platform played the central role, supported by Microsoft Stream for recording videos and Microsoft Forms for collecting student responses. A typical flow of work would involve myself recording a 5–10-min video outlining an issue I would like to discuss, such as students’ preferred methods of assessment. Afterwards, I would ask students to answer a few questions, such as how they would rate several different assessment forms and which ones were their most/least favourite types. After reading the responses, I would record another video commenting on student responses and offering them some tips and insights into how assessment works from the pedagogical perspective. Finally, I would ask students to comment on that follow-up video, which would often lead to the new cycle. Overall, between 70 and 90 students actively participated throughout the project, and they made over 500 written contributions on different areas of assessment and feedback. The project ended in April 2019 with very positive student feedback.

How do students want to be assessed?

The question concerning students’ assessment preferences was the first one I raised. First, I asked students to rate 15 different forms of assessment according to their preferences, with a system of five stars ratings. Students were invited to freely interpret the notion of “preference” and whether it related to value-added to their learning process, perceived difficulty, student familiarity or something else. The subsequent two open qualitative questions, where students justified their most and least preferred choices, allowed them to clarify what it is exactly that they like/dislike about those assessment types. Ninety students responded. My expectation was that students would prefer innovative or non-standard forms of assessment to essays and examinations. In reality, essays emerged on top of the list, followed by essay plans and short response papers. Assessment related to problem-based learning (PBL) and simulations were next on the list, with the least favourite assessment forms being poster presentations, oral presentations and examinations. While PBL and simulations can, more appropriately, be classified as assessment activities rather than assessment forms, Carol Evans rightly includes them on the list of assessment types Footnote 1 because they are inherently predisposed to generate a variety of non-standard assessments, such as practical performance or written/oral interpretation of practical experience. For this reason, it is difficult to disentangle PBL and simulations as learning techniques from associated assessment as these non-standard learning activities typically work in tandem with a set of non-standard assessment forms.

When justifying their choices, students defended essays as representing the fairest form of assessment, allowing them to demonstrate their true academic potential. Arguably, essays allow undertaking a more in-depth approach to researching a specific topic. They support advancing a careful and considerate thought and offer enough time to research and explore the topic. Essays allow getting to grips with different arguments. Because there is plenty of time available, essays represent a true reflection of the students’ ability. Finally, essays allow going into the details of a question and carefully study the answer. They are effective in drawing students’ attention into the relevant literature and are supportive of students’ developing own arguments. Based on the combination of practical experience, insights from pedagogical literature and student engagement, I argue in the following section that essays should constitute the bedrock of assessing IR in undergraduate education. In fact, skills associated with academic essay writing have become crucially important—more than anywhere in the past—and it is difficult to overestimate their practical significance.

Tier one: academic essays and their practical value for IR

For the purpose of my argument, I do not draw the distinction between longer papers and short response papers. This kind of distinction was indeed relevant for McMillan ( 2014 ), who argues the value of short papers over longer ones in IR, but undergraduate essays come in different sizes ranging from 500 to 600 words short papers all the way up to 5000–6000 words. It is even possible to consider the final undergraduate project itself—the dissertation—a one long essay, especially if it is oriented towards theory or history. Instead of the length, what matters is the underpinning characteristics of academic essays. These are long established and include (a) explicitness, in that the academic essay form is devoid of nuances; (b) the rationalist and humanist paradigm, in that the written form is considered crucial for exchanging knowledge and fostering progress; and (c) persuasiveness, in that the essay aims to advance ideas supported by explicit evidence (Andrews 2003 ).

In the UK context, the industry-oriented and economic growth-driven policy agenda has led to the dismissal of the humanities and social sciences subjects, in which essays dominate, and the promotion of science and engineering (STEM) subjects instead. As such, and in comparison with the more pragmatic, technical and result-oriented reports, it may be tempting to view essays as “academic” in the pejorative sense of the word, i.e. entailing abstract and hence impractical approach to theorise about ideas. In reality, essays allow to develop and practice skills relevant not only for employment prospects, but also—from the IR perspective—to navigate the completely new reality of the interconnection between international politics, new technologies and populism. Among others, academic essays allow to practice “research skills, logical and critical thinking skills, clear expression, independent learning, communications skills, organisational skills, time and task management skills self-awareness, reflective skills (…)” (Shields 2010 : 20).

Essays and critical thinking

One helpful way to distinguish between the value of essays for assessing IR from methods related to active learning is to recognise that they emphasise two different kinds of knowledge: declarative and functioning. The word “emphasise” is appropriate here because the two kinds of assessment do not align themselves neatly with the two kinds of knowledge. Essays, for example, can ask students to apply declarative knowledge to an empirical problem, such as an international conflict. Simulation-related assessments, on the other hand, may require students to identify relevant facts or argue their position. Both kinds of knowledge can be further divided up into different levels of demonstrated complexity using so-called SOLO framework, which stands for structure of the observed learning outcome (Biggs and Tang 2011 , pp. 86–90). The SOLO framework stipulates that when students learn, their understanding should grow in complexity, progressing across five levels. These learning levels are:

Prestructural Indicating that students only understand individual words, but their sentences miss the point due to lack of knowledge and understanding.

Unistructural Indicating that students can identify one basic aspect of a problem, but missing other dimensions.

Multistructural Indicating that students know various facts (individual trees), but lack an overarching understanding of a problem (the forest).

Relational Indicating that students can tie together different facts into a coherent “whole”. Different facts and concepts are integrated to present us with the “forest view” of a problem.

Extended abstract Indicating that students can move beyond the immediate confines of the question and conceptualise their response at the higher level, offering the reader a new perspective on a problem.

The model will look familiar to the students of Rosenau and Durfee ( 1995 ) and their ladder of abstraction, which stipulates that we should always strive to reach a higher level of understanding by shifting our focus away from simple facts and towards identifying relationships and patterns, making ourselves more theoretically conscious. The bottom line of both propositions is that learning entails improving our comprehension of complexity, which entails thinking in a more structured and logical way, reaching better-informed conclusions or being able to synthesise information based on sound assessment of arguments. Those are all components of critical thinking—a foundational skill (still) underpinning the rationale behind higher education. In this context, essays remain a highly suitable and practical way for students to practice their complexity comprehension, as well as to demonstrate their progress to the degree-awarding institution. The SOLO framework, in turn, allows situating students’ progress on a scale from a very basic understanding all the way up to the ability to abstract the problem and see it from a new perspective.

Critical thinking in IR: Brexit and Donald Trump

Although it is difficult to overemphasise the practical implications of practicing and improving the skills promoted by a simple academic essay, one caveat needs to be made here. Naturally, each module should begin with setting up learning objectives and those objectives should dictate the form of assessment. In the words of Biggs ( 2003 ), assessment should not come as a standalone consideration and instead should be constructively aligned with the learning outcomes. This article specifically focuses on the academic disciple of IR, which has developed a relatively well-delineated scope over 100 years since establishment. If the purpose of higher education, in the words of McCaffery ( 2019 : 35), is to “complement critical thinking (…) with critical self-reflection and critical action”, then it is the overarching purpose of IR education to nourish this “formation of critical being” in relation to politics beyond the boundaries of the nation states. Critical being in IR requires awareness of key structures and processes constituting the realm of the “international” and how they manifest themselves in political agendas, decisions, actions or inactions. For example, what are the implications of climate change or coronavirus to international politics? How to make sense of Brexit or Donald Trump’s foreign policy? Regardless of specific learning objectives, few IR teachers will deny these are relevant topics in IR education, and so, the following examples illustrating the relevance of academic essays relate to some of these topics.

In Foreign Affairs, Tom Nichols ( 2017 ) paints a sobering, if not entirely shocking image of the American rejection of experts and expertise. What is particularly disturbing, according to Nichols, is not the fact that Americans do not know about the world (roughly half of the polled respondents favoured bombing Agrabah—a fictional country from a Disney movie), or even that they distaste intellectuals. What seems new and alarming is that ignorance is increasingly considered a virtue and even the most heated argument exchanges are simply replaced by “shouting matches”. One interesting twist to this argument was the observation that the more ignorant the respondents were about the topic, the more definite answers they offered. Another one was the fact that respondents seem equally ignorant on both sides of the ideological spectrum—conservative and liberal.

In the UK context, a study of voters’ knowledge of the European Union (EU) revealed one similar trend: contrary to the popular perception among “Remainers” that the Brexit voters were uninformed, the level of EU knowledge is actually the same on both sides (Carl 2019 ). In one study, both “Remainers” and “Leavers” scored an average of 60% of correct answers to the list of 15 questions about the EU. While it is debatable whether this level of knowledge—on both sides—was enough to decide on an international political issue of such an enormous magnitude, other research findings from the study are actually more interesting in the context of academic essay writing. Out of the 15 questions, nine were considered by the authors “ideologically neutral”, in that the response to those questions was not particularly convenient for either of the sides. Six questions, on the other hand, could be considered more “ideologically convenient” for one of the sides, in that they asked about things such as the level of the UK’s contribution to the EU budget or whether the UK contributes more to the EU budget than it receives.

What is interesting is that factors such as age and higher education affected the level of knowledge related to the first nine “neutral” questions. In contrast, the political ideology of the respondents seems to have gotten an upper hand when answering the more “ideological” questions, in that both sides responded relatively better to questions, which appeared more ideologically convenient to them. For example, “Leavers” were more often correct than “Remainers” when responding to the statement that “The UK currently pays more money into the EU than it gets back in the form of subsidies and other funds” (which is true). Conversely, “Remainers” were more often right when responding to the statement that “More than ten per cent of British government spending goes to the EU” (which is false).

Both the US and UK examples illustrate that people are generally ignorant about the complex matters of international politics. This is hardly surprising. Further, their ignorance does not prevent them in any way from articulating definite opinions, participating in referendums or otherwise acting upon their believes. The American and British examples further confirm the power of ideological biases, which are well known in the world of party politics. We could argue that in the current age of enormous political polarisation, the high level of ideological bias is to be expected among both politicians and the population at large. University campuses, especially in the USA, are not immune to it (Mazer 2018 ). Still, if there is any meaningful role that universities can still undertake other than proffer their brand name to their graduates’ CVs, it is to encourage students to become more critical thinkers and writers. This brings us back to academic essays, which are rightly at the heart of facilitating this task.

The SOLO framework, essays and IR

Returning to the example of Brexit, ideological position, combined with some rudimentary knowledge of the EU, prompted UK citizens to cast their vote in a referendum. Many of those voters likely operated with the unistructural or—at best—multistructural level of EU knowledge, identifying a limited number of individual facts about the EU. Academic essays, by their nature, encourage research when confronted with a problem, prompting students to seek evidence in support of their argument and nourishing the habit of seeking information from higher-quality resources. At this basic level, they encourage students to progress towards practicing multistructural knowledge, where they can identify multiple facts in support of their argument, but also describe and classify those facts.

The value of academic essays is most prominent, however, when they prompt students to progress towards higher levels of comprehension, as indicated by the relational and extended abstract learning levels. Here, to continue with the Brexit example, students are not only able to identify multiple facts relevant to the discussion on the UK’s membership in the EU. They are also able to compare and contrast these facts, analyse and explain them and ultimately argue their case for the UK’s relationship with the EU. Eventually, students should also be able to move outside of the immediate confines of the Brexit question and generalise as well as theorise the problem at the higher level of abstraction by linking it to related concepts such as sovereignty, populism, globalisation or fear.

As for the question of ideological bias, the practice of essay writing remains the most promising exercise requiring students to systematically challenge and question their prior believes and value systems. If they come to the university convinced that, for example, excessive migration from EU countries justifies Brexit, they may still leave the university holding that core believe. At the same time, however, after writing numerous essays concluded with a long-form research project, they should graduate being able to better appreciate the complexity and interconnectedness of those multifaceted political phenomena. They should also be equipped to better recognise how their own ideological biases affect their position on the questions of national and international politics.

Tier two: assessing functioning knowledge through active learning

To reinforce the value of academic essays for assessing IR is not to dismiss more practical assessment methods, such as those stemming from in-class simulations and other kinds of PBL. Here, the paper aligns its argument with most of the writings on IR pedagogy, but it emphasises equal value of both traditional and innovative assessment methods. They are both important because—as noted—essays remain highly practical and relevant . Further, they both emphasise distinct kinds of knowledge, although with overlaps. Essays emphasise declarative knowledge. They teach students to describe, classify, compare, contrast, explain, argue and analyse. They also teach to theorise and generalise (Biggs and Tang 2011 : 124). Assessments related to problem-based and active exercises such as simulations, on the other hand, help students learn how to apply knowledge, solve immediate and remote problems, reflect and improve practice (Biggs and Tang 2011 : 124).

In the staff–student partnership initiative, assessment through PBL exercises, including simulations, constituted the second most preferred method among students participating in my staff–student partnership initiative. In this instance, many students who participated in the survey also participated in the Statecraft simulation, so they understood what kind of assessment was linked with the simulation. It included quizzes, reflective statement and performance. In other educational contexts, where students don’t know how a simulation exercise could be assessed, it will help to offer specific examples. As with essays, students justified their preferences in a variety of ways. Arguably, simulations make learning more effective because they allow practicing it and applying to problems. Simulations are especially relevant for learning theories and ideas. Simulations are arguably right for individual expression, and they allow learning without the pressure associated with presentations or debates. Simulations are entertaining, enjoyable and a compelling reason to engage with the module. Related to that point, simulations raise the level of engagement and focus among students when playing a simulation. Another advantage of simulations is their perceived utility for practicing skills important for employability. Different students pointed to different reasons as to why PBL methods are a good way to assess IR, but they mostly revolved around these few points.

These pro-simulation arguments align with the pedagogical literature. A quick glance at the scholarship on teaching and learning in IR indicates that among pedagogically aware academics, there is a strong inclination to move towards active learning methodologies, most notably simulations. As noted, this is hardly surprising because the field of IR is naturally predisposed to encourage this kind of teaching approach. Glazier reinforces this observation, noting that the use of simulations for teaching IR has greatly increased, even if the idea is not new (Glazier 2015 :266–267). Simulations are supposed to offer students a different and, arguably, more effective, way of learning compared to reading and listening. The concepts, dilemmas, problems and theories familiar to IR scholars become more accessible to students through simulations, allowing students to experience them in a controlled environment (Wedig 2010 ). The simulations are also seemingly a more appropriate method for millennial students, who are more receptive to problem-based methods and the learning process cantered on their practical experiences (Crossley-Frolick 2010 ). Finally, computer-based simulations should also develop students’ reflective and critical thinking skills with computers acting “as cognitive amplification tools for reflecting on what students have learned and what they know” (Jonassen et al. 1998 ). As noted, simulations, while not representing an assessment type as such, invite a variety of assessment methods which can complement essays and diversify student experience. Reflective statements, for example, encourage students to consider their practical experience in the context of the theoretical contents of the module [even if this method has limitations—see Raymond and Usherwood 2013 )]. Assessing simulation performance, on the other hand, encourages students to take the exercise seriously and invest some intellectual effort into it.

Simulations, along with other PBL approaches (such as solving practical world problems in class), represent so-called high-impact pedagogies in higher education learning. Their aim can be identified as to “adequately equip students with the knowledge, capabilities and personal qualities that will enable them to thrive in complex and changing contexts” (Evans et al. 2015 : 11). Simulations, if properly designed and assessed, can certainly contribute to these noble objectives. At the same time, however, we must also underline the lack of concluding evidence confirming the value of high impact pedagogies for stronger learning outcomes (Evans et al. 2015 : 11). J. Celeste Lay and Kathleen J. Smarick, whose students simulated a US Senate office at a large US university, caution against setting expectations for simulations too high. They reinforce the argument of this paper by recommending that simulations should not be adopted as a single teaching method, but instead as a supplement to more traditional pedagogies (Lay and Smarick 2006 ).

In lieu of conclusion: obstacles to implementation

I am under no illusion that the two-tier assessment model proposed in this paper, together with the holistic methodology for designing assessment, can be easily implemented across undergraduate IR programs in the UK and elsewhere. Consequently, instead of a traditional conclusion, I propose to address the potential obstacles both junior and senior academics may face when experimenting with assessment design along the lines outlined here. First, there is the question of the actual purpose of assessment. The two-tier model is based on a rather idealistic assumption that students generally attend classes and engage with the contents of the module. With that assumption in mind, we can then focus on designing assessment, which, we believe, makes most pedagogical sense based on our intended learning outcomes, pedagogical literature and student preferences.

The reality, at least in the UK context, is often very different, however. Since lectures are mostly non-compulsory in undergraduate education, some students choose not to attend them. This is a problem for different kinds of reasons, and so, the teaching staff typically reacts by seeking ways to improve attendance. If students strategise their time allocation around assessment, as evidenced in this paper, then essay-based assessment is not optimal because it does not encourage active participation. In fact, anecdotal evidence suggests that it seems perfectly logical for many students to only attend sessions covering the topic of their essays and consider other sessions less relevant. As a result, if lecture attendance and participation is a problem, then other forms of assessment may be considered more suitable to entice student participation. In this case, assessment assumes an additional, disciplinary function. Examination naturally comes to mind as a popular form of assessment, which can be hoped to discipline students to attend sessions, provided the lectures are not recorded and made available online. In this instance, the teacher must use judgement and try to reconcile the pedagogical value of different forms of assessment with the cultural setting in which learning takes place.

The second challenge concerns replicating the holistic method for assessment design, which involves teacher’s own experience, familiarity with the pedagogical research and working in partnership with students. In my own experience, setting up effective staff–student partnership proved most time-consuming, although most of the time was spent in preparation for the initiative. Once I got a good grasp of the MS Teams platform and how to upload videos, I was able to run the initiative committing no more than 2–3 h every other week. This may still prove too time-consuming for many. The alternative to a structured and technology-enhanced partnership with students could be a less formal and more ad hoc system of chatting with students about their assessment and feedback preferences. The idea is to get a better understanding of how students themselves see assessment and feedback, which may differ across institutions and cultures. Another issue is finding time for pedagogical research. In the field of IR, there is a decent amount of the literature on designing teaching, learning and assessment, but it mostly relies on the broader field of higher education pedagogy (active learning, PBL, etc.). One efficient way to gain insights from the pedagogical scholarship is to meet with colleagues working in the field of higher education and discuss ideas. Another approach would be to link pedagogical research for assessment purposes with other objectives, such as applying for an Advance HE’s fellowship, a promotion or simply to better fulfil one’s administrative role.

The final challenge also concerns time pressures faced by modern academics, but this time it relates to executing the two-tier assessment model discussed in this paper. Essays are relatively straightforward, and all academics (and students) are familiar with the format. However, one aspect of essay-based assessment, which students in my staff–student partnership raised and which is reinforced by the pedagogical scholarship, can significantly raise the workload for the marking staff. It concerns the need for so-called feedforward, entailing some form of a learning curve for students whereby their initial writing attempts have lower stakes in relation to the final essay. Those lower stake assignments could be shorter essay plans or drafts, but they still require someone to read them and offer feedback. Similarly, simulations can be prohibitively time-consuming and even fully automated simulation platforms, such as Statecraft, require significant time and a learning effort on the part of the instructor. The only practical solution, in this case, may be to rely on teaching assistants for the day-to-day facilitation of the simulation, but the availability of those extra teaching resources will vary across institutions, programs and modules.

In a privately distributed document ‘Types of assessment brief’, EAT 2016.

Andrews, R. 2003. The end of the essay? Teaching in Higher Education 8 (1): 117–128.

Article Google Scholar

Becker, H.S., B. Geer, and E.C. Hughes. 1968. Making the grade: The academic side of college life . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Google Scholar

Biggs, J. 2003. Aligning teaching for constructing learning . York, UK: Higher Education Academy.

Biggs, J., and C. Tang. 2011. Teaching for quality learning at University . Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Carl, N. 2019. Are leave voters less knowledgeable about the EU than remain voters? Brexit and public opinion 2019 , 16–17. London: The UK in a Changing Europe.

Carvalho, G. 2014. Virtual worlds can be dangerous: Using ready-made computer simulations for teaching international relations. International Studies Perspectives 15 (4): 538–557.

Crossley-Frolick, K.A. 2010. Beyond model UN: Simulating multi-level, multi-actor diplomacy using the Millennium Development Goals. International Studies Perspectives 11 (2): 184–201.

Engert, S., and A. Spencer. 2009. International relations at the movies: Teaching and learning about international politics through film. Perspectives 17 (1): 83–103.

Epley, J. 2016. Learning by doing: Using an online simulation game in an international relations course. Journal of Interactive Learning Research 27 (3): 201–218.

Evans, C., D. Muijs, and M. Tomlinson. 2015. Engaged student learning: High-impact strategies to enhance student achievement . York: Higher Education Academy.

Glazier, R. 2015. Teaching international relations. In Handbook on teaching and learning in political science and international relations , ed. J. Ishiyama, W.J. Miller, and E. Simon, 265–276. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Healey, M., A. Flint, and K. Harrington. 2014. Engagement through partnership: Students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education . York: Higher Education Academy.

Horn, L., O. Rubin, and L. Schouenborg. 2015. Undead pedagogy: How a zombie simulation Can contribute to teaching international relations. International Studies Perspectives 17 (2): 187–201.

Jonassen, D.H., C. Carr, and H.-P. Yueh. 1998. Computers as mindtools for engaging learners in critical thinking. TechTrends 43 (2): 24–32.

Kaunert, C. 2009. The European Union simulation: From problem-based learning (PBL) to student interest. European Political Science 8 (2): 254–265.

Kollars, N.A., and A.M. Rosen. 2013. Simulations as active assessment? Typologizing by purpose and source. Journal of Political Science Education 9 (2): 144–156.

Lay, J.C., and K.J. Smarick. 2006. Simulating a senate office: The impact on student knowledge and attitudes. Journal of Political Science Education 2 (2): 131–146.

Linantud, J., and J. Kaftan. 2018. The Statecraft effect: Assessment, attitudes, and academic honesty. Journal of Political Science Education 15 (1): 64–81.

Mattlin, M. 2018. Adapting the DIPLOMACY board game concept for 21st century international relations teaching. Simulation and Gaming 49 (6): 735–750.

Mazer, J.P. 2018. Teachers, students, and ideological bias in the college classroom. Wicked problems forum: Freedom of speech at colleges and universities. Communication Education 67 (2): 254–258.

McCaffery, P. 2019. The higher education manager’s handbook , 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

Mcmillan, S.L. 2014. Bravo for brevity: Using short paper assignments in international relations classes. International Studies Perspectives 15 (1): 109–120.

Miller, C.M.L., and M.R. Parlett. 1974. Up to the Mark: A study of the examination game . London: Society for Research into Higher Education.

Nichols, T. 2017. How America lost faith in expertise: And why that’s a giant problem. Foreign Affairs 96 (2): 60–73.

Pouliot, V. 2008. The Logic of practicality: A theory of practice of security communities. International Organization 62 (2): 257–288.

Ramel, F. 2018. Teaching international relations through arts: Some lessons learned. International Studies Perspectives 19 (4): 360–374.

Raymond, C. 2014. Can’t get no (dis)satisfaction: The Statecraft simulation’s effect on student decision making. Journal of Political Science Education 10 (3): 302–314.

Raymond, C., and S. Usherwood. 2013. Assessment in simulations. Journal of Political Science Education 9 (2): 157–167.

Rösch, F. 2018. The power of dance: Teaching international relations through contact improvisation. International Studies Perspectives 19 (1): 67–82.

Rosenau, J.N., and M. Durfee. 1995. Thinking theory thoroughly: Coherent approaches to an incoherent world . Boulder: Westview Press.

Saiya, N. 2016. The Statecraft simulation and foreign policy attitudes among Undergraduate students. Journal of Political Science Education 12 (1): 58–71.

Shields, M. 2010. Essay writing: A student’s guide . London: Sage.

Simpson, A.W., and B. Kaussler. 2009. IR teaching reloaded: Using films and simulations in the teaching of international relations. International Studies Perspectives 10 (4): 413–427.

Snyder, B.R. 1971. The hidden curriculum . New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Valeriano, B. 2013. Teaching introduction to international politics with film. Journal of Political Science Education 9 (1): 52–72.

Wedig, T. 2010. Getting the most from classroom simulations: Strategies for maximizing learning outcomes. Political Science and Politics 11 (4): 547–555.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Politics and International Relations, University of Southampton, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK

Kamil Zwolski

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kamil Zwolski .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Zwolski, K. Assessing international relations in undergraduate education. Eur Polit Sci 20 , 345–358 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-020-00255-0

Download citation

Published : 06 May 2020

Issue Date : June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-020-00255-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- International relations

- Simulations

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

St Andrews Research Repository

- St Andrews Research Repository

- International Relations (School of)

- International Relations

International Relations Theses

- Register / Login

By Issue Date Names Titles Subjects Classification Type Funder

Search within this collection:

Our research is focused around three broad themes: conflict, peace and security; the evolving character of global and supra-national institutions; and the interpenetration of civil societies and international relations. In addition we have major strengths in area studies which help to ground our research into these broad thematic areas. Some of this activity is carried out under the umbrella of our various research centres, some within other collaborative contexts both within and outside the university, and some by individual researchers.

For more information please visit the School of International Relations home page.

This material is presented to ensure timely dissemination of scholarly and technical work. Copyright and all rights therein are retained by authors or by other copyright holders. All persons copying this information are expected to adhere to the terms and constraints invoked by each author's copyright. In most cases, these works may not be reposted without the explicit permission of the copyright holder.

Recent Submissions

Slaying ideological dragons : the life and thought of kenneth minogue , the myth of beneficial colonisation : coloniality of knowledge production in constructing singapore's history , mission 'mare nostrum', 2013–2014 : a framework of analysis for maritime search and rescue operations , title redacted , invisible transitional justice : a comparative case in the catatumbo and montes de maria regions (colombia) .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Latest science news, discoveries and analysis

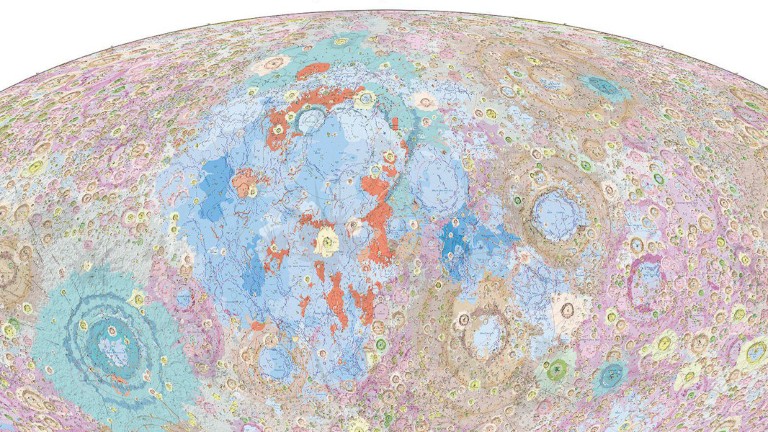

China's Moon atlas is the most detailed ever made

‘Shut up and calculate’: how Einstein lost the battle to explain quantum reality

Rat neurons repair mouse brains — and restore sense of smell

Mini-colon and brain 'organoids' shed light on cancer and other diseases

Scientists urged to collect royalties from the ‘magic money tree’, first glowing animals lit up the oceans half a billion years ago, plastic pollution: three numbers that support a crackdown, the maldives is racing to create new land. why are so many people concerned, ecologists: don’t lose touch with the joy of fieldwork chris mantegna.

Should the Maldives be creating new land?

Lethal AI weapons are here: how can we control them?

Algorithm ranks peer reviewers by reputation — but critics warn of bias

How gliding marsupials got their ‘wings’

Bird flu in us cows: is the milk supply safe, nato is boosting ai and climate research as scientific diplomacy remains on ice, hello puffins, goodbye belugas: changing arctic fjord hints at our climate future, nih pay raise for postdocs and phd students could have us ripple effect.

Retractions are part of science, but misconduct isn’t — lessons from a superconductivity lab

Any plan to make smoking obsolete is the right step

Citizenship privilege harms science

European ruling linking climate change to human rights could be a game changer — here’s how charlotte e. blattner, will ai accelerate or delay the race to net-zero emissions, current issue.

Surprise hybrid origins of a butterfly species

Stripped-envelope supernova light curves argue for central engine activity, optical clocks at sea, research analysis.

Ancient DNA traces family lines and political shifts in the Avar empire

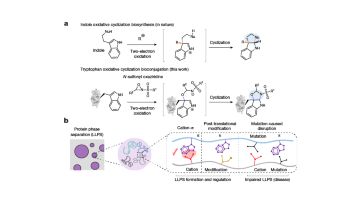

A chemical method for selective labelling of the key amino acid tryptophan

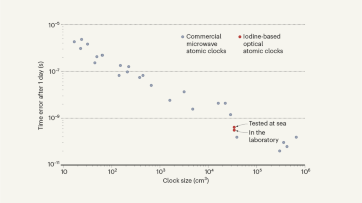

Robust optical clocks promise stable timing in a portable package

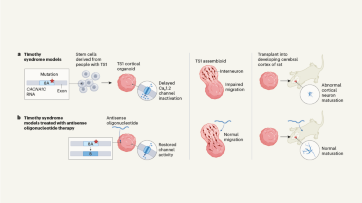

Targeting RNA opens therapeutic avenues for Timothy syndrome

Bioengineered ‘mini-colons’ shed light on cancer progression, galaxy found napping in the primordial universe, tumours form without genetic mutations, marsupial genomes reveal how a skin membrane for gliding evolved.

Breaking ice, and helicopter drops: winning photos of working scientists

Shrouded in secrecy: how science is harmed by the bullying and harassment rumour mill

How ground glass might save crops from drought on a caribbean island, londoners see what a scientist looks like up close in 50 photographs, books & culture.

How volcanoes shaped our planet — and why we need to be ready for the next big eruption

Dogwhistles, drilling and the roots of Western civilization: Books in brief

Cosmic rentals

Las borinqueñas remembers the forgotten puerto rican women who tested the first pill, dad always mows on summer saturday mornings, nature podcast.

Latest videos

Nature briefing.

An essential round-up of science news, opinion and analysis, delivered to your inbox every weekday.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

International Relations An IntroductIon to Second edition Invaluable to students and those approaching the subject for the first time, An Introduction to International Relations, Second Edition provides a comprehensive and stimulating introduction to international relations, its traditions and its changing nature in an era of globalisation.

See Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink, 'Taking Stock: The Constructivist Research Program in International Relations and Comparative Politics', Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 4, no. 1 ...

and Research Design in International Relations 58 4.1 Selected Major Journals in International Relations 85 6.1 From Concept to Coding 121 6.2 GDP per capita (USD) and Life Expectancy (in years) 130 6.3 Per Capital GDP and Life Expectancy Regression Statistics 130 7.1 Three Mixed Method Research Designs and Examples from Scholarship 144

without a foreign policy, has been compared to a shi p in the deep sea. without any knowledge of directions. us, foreign policy leads a state. in ful lling its national interests and acquiring ...

A temporal typology of International Relations paradigms. "positive feedback over time simultaneously increases power asymmetries and renders power relations less visible.". Other scholars believe path-dependent phenomena are less pervasive or less common than is commonly perceived (Leibowitz and Margolis, 1995: 2006).

Contents List of Boxes xvii List of Maps and Figures xxii Preface xxiii 1. The Discipline of International Relations: Imagination, Definition, and Evolution 1.1 1.2 Imagining International Relations Defining International Relations 1.2.1 Inter 1.2.2 Nation 1.2.2.1 Territory 1.2.2.2 Permanent Population or Nation 1.2.2.3 Government 1.2.2.4 Sovereignty 1.2.2.5 Non-State Actors 1.2.3 Relations ...

1. International Relations. Introduction: International relations (IR) or international affair s (IA) commonly also referred to as. international studies (IS), global studies ( GS), or global ...

vi RESEARCH METHODS IN OLITICS INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Why Methodology Matters: Making Informed Research Choices 27 ... The Structure and Contents of a PIR Research Paper 166 00_LAMONT_BODUSZYNSKI_FM.indd 7 2/17/2020 12:00:47 PM. viii RESEARCH METHODS IN OLITICS INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Some Notes on Writing in an Academic Style 178 Chapter ...

UCLA Journal of International Law and Foreign Affairs. 1996 - 2020. Uluslararası İlişkiler / International Relations. 2004 - 2023. Vereinte Nationen: German Review on the United Nations. 1962 - 2020. Verfassung und Recht in Übersee / Law and Politics in Africa, Asia and Latin America. 1968 - 2020. Warship Technology.

Conflict, peace and security are some of the enduring concerns of the Peace Research Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. They have become integrated in the dominant disciplines of international relations (IR) and political science and now are also part of most of the social science disciplines, such as economics, sociology, public policy, gender studies, international law and so on.

Ethics and International Relations Lebow demonstrates that foreign policies consistent with generally accepted ethical norms are more likely to succeed, and those at odds with them to fail. Constructing original data sets and analyzing multiple case studies, Lebow makes an empirical case for ethics in international relations.

This paper advocates a holistic approach to assessing international relations in undergraduate education, which revolves around: (a) essays and (b) active learning-related tasks, such as simulation reflective statements/reports and performance. The paper argues that, on the one hand, academic essays are far from irrelevant and it is difficult to overestimate their practical significance. On ...

Research Methods in International Relations. C. Lamont. Published 7 May 2015. Political Science. Introduction Chapter 1: Research Methods in International Relations Chapter 2: Research Questions and Research Design Chapter 3: Research Ethics Chapter 4: Writing a Literature Review Chapter 5: Qualitative Methods in International Relations Chapter ...

Group devoted to the social science discipline of International Relations | Explore the latest full-text research PDFs, articles, conference papers, preprints and more on INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS ...

Our research is focused around three broad themes: conflict, peace and security; the evolving character of global and supra-national institutions; and the interpenetration of civil societies and international relations. In addition we have major strengths in area studies which help to ground our research into these broad thematic areas.

International Relations is explicitly pluralist in outlook. Editorial policy favours variety in both subject-matter and method, at a time when so many academic journals are increasingly specialised in scope, and sectarian in approach. We … | View full journal description. This journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE).

emergent challenges and the central debates in the field of international relations. In addition, I have updated and expanded the list of web sites to reflect the rapidly growing number of non-governmental organisations, research institutes, and academic journals in international relations. Steven C. Roach University of South Florida March 2007 vi

NEGOTIATION AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Dr. SANGRAM BEHARI Assistant Professor, ... By delving into the intricacies of diplomatic practices, this paper aims to shed light on the critical role diplomacy plays in shaping the course of world affairs. ... JETIR2204855 Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR) www.jetir.org i443

The literature on global international relations (IR) has argued that the discipline develops in the footsteps of world politics, but no sustained attention has been given to more immediate causes ...

ABSTRACT. Research and Writing in International Relations, Third Edition, offers the step-by-step guidance and the essential resources needed to compose political science papers that go beyond description and into systematic and sophisticated inquiry. This book provides concise, easy-to-use advice to help students develop more advanced papers ...

China's rise, networks, and the liberal hegemon. Deborah Welch Larson. Preview abstract. Open Access Product Review First published June 28, 2022 pp. 113-133. xml PDF / EPUB. Table of contents for International Relations, 38, 1, Mar 01, 2024.

This paper studies the realist theory of International Relations and attempts an. explanation of how it illuminates our unders tanding of inter-state relations. We. analyse the key assumptions of ...

Find breaking science news and analysis from the world's leading research journal.

PDF | On Mar 13, 2018, Radhika Kapur published International Relations in India | Find, read and cite all the research you need on ResearchGate