- AERA Open Editors

- AERJ Editors

- EEPA Editors

- ER Issues and Archives

- JEBS Editors

- JSTOR Online Archives

- RER Editors

- RRE Editors

- AERA Examination and Desk Copies

- Mail/Fax Book Order Form

- International Distribution

- Books & Publications

- Merchandise

- Search The Store

- Online Paper Repository

- Inaugural Presentations in the i-Presentation Gallery

- Research Points

- AERA Journal Advertising Rate Cards

- Publications Permissions

- Publications FAQs

Share

The Review of Educational Research ( RER , bimonthly, begun in 1931) publishes critical, integrative reviews of research literature bearing on education. Such reviews should include conceptualizations, interpretations, and syntheses of literature and scholarly work in a field broadly relevant to education and educational research. RER encourages the submission of research relevant to education from any discipline, such as reviews of research in psychology, sociology, history, philosophy, political science, economics, computer science, statistics, anthropology, and biology, provided that the review bears on educational issues. RER does not publish original empirical research unless it is incorporated in a broader integrative review. RER will occasionally publish solicited, but carefully refereed, analytic reviews of special topics, particularly from disciplines infrequently represented.

Impact Factor : 11.2 5-Year Impact Factor : 16.6 Ranking : 1/263 in Education & Educational Research

- Open Access

- © 2020

Systematic Reviews in Educational Research

Methodology, Perspectives and Application

- Olaf Zawacki-Richter 0 ,

- Michael Kerres 1 ,

- Svenja Bedenlier 2 ,

- Melissa Bond 3 ,

- Katja Buntins 4

Oldenburg, Germany

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Essen, Germany

With contributions from international experts

First volume with a special focus on systematic reviews in educational research

Contains practical examples

Takes ethical considerations into account

502k Accesses

350 Citations

222 Altmetric

- Table of contents

About this book

Editors and affiliations, about the editors, bibliographic information.

- Publish with us

Buying options

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Table of contents (9 chapters), front matter, methodological considerations, systematic reviews in educational research: methodology, perspectives and application.

- Mark Newman, David Gough

Reflections on the Methodological Approach of Systematic Reviews

- Martyn Hammersley

Ethical Considerations of Conducting Systematic Reviews in Educational Research

Teaching systematic review.

- Melanie Nind

Why Publish a Systematic Review: An Editor’s and Reader’s Perspective

- Alicia C. Dowd, Royel M. Johnson

Examples and Applications

Conceptualizations and measures of student engagement: a worked example of systematic review.

- Joanna Tai, Rola Ajjawi, Margaret Bearman, Paul Wiseman

Learning by Doing? Reflections on Conducting a Systematic Review in the Field of Educational Technology

- Svenja Bedenlier, Melissa Bond, Katja Buntins, Olaf Zawacki-Richter, Michael Kerres

Systematic Reviews on Flipped Learning in Various Education Contexts

- Chung Kwan Lo

The Role of Social Goals in Academic Success: Recounting the Process of Conducting a Systematic Review

- Naska Goagoses, Ute Koglin

- Systematic Reviews

- Educational Research

- Practical Examples for Systematic Reviews

- Student Engagement

- Educational Technology

- Academic Success

- Education Research

Olaf Zawacki-Richter, Svenja Bedenlier, Melissa Bond

Michael Kerres, Katja Buntins

Prof. Dr. Olaf Zawacki-Richter, Professor of Educational Technology, Center for Open Education Research (COER), Faculty of Education and Social Science, Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Germany.

Prof. Dr. Michael Kerres, Professor of Educational Science | Learning Technology & Innovations, Learning Lab, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany.

Dr. Svenja Bedenlier, Research Associate, Center for Open Education Research (COER), Faculty of Education and Social Science, Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Germany.

Katja Buntins, Research Associate, Learning Lab, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany.

Book Title : Systematic Reviews in Educational Research

Book Subtitle : Methodology, Perspectives and Application

Editors : Olaf Zawacki-Richter, Michael Kerres, Svenja Bedenlier, Melissa Bond, Katja Buntins

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-27602-7

Publisher : Springer VS Wiesbaden

eBook Packages : Education , Education (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020

License : CC BY

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-658-27601-0 Published: 02 December 2019

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-658-27604-1 Published: 11 September 2020

eBook ISBN : 978-3-658-27602-7 Published: 21 November 2019

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XXI, 161

Number of Illustrations : 4 b/w illustrations

Topics : Research Methods in Education

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Review of Educational Research

Subject Area and Category

SAGE Publications Inc.

Publication type

00346543, 19351046

Information

How to publish in this journal

The set of journals have been ranked according to their SJR and divided into four equal groups, four quartiles. Q1 (green) comprises the quarter of the journals with the highest values, Q2 (yellow) the second highest values, Q3 (orange) the third highest values and Q4 (red) the lowest values.

The SJR is a size-independent prestige indicator that ranks journals by their 'average prestige per article'. It is based on the idea that 'all citations are not created equal'. SJR is a measure of scientific influence of journals that accounts for both the number of citations received by a journal and the importance or prestige of the journals where such citations come from It measures the scientific influence of the average article in a journal, it expresses how central to the global scientific discussion an average article of the journal is.

Evolution of the number of published documents. All types of documents are considered, including citable and non citable documents.

This indicator counts the number of citations received by documents from a journal and divides them by the total number of documents published in that journal. The chart shows the evolution of the average number of times documents published in a journal in the past two, three and four years have been cited in the current year. The two years line is equivalent to journal impact factor ™ (Thomson Reuters) metric.

Evolution of the total number of citations and journal's self-citations received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. Journal Self-citation is defined as the number of citation from a journal citing article to articles published by the same journal.

Evolution of the number of total citation per document and external citation per document (i.e. journal self-citations removed) received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. External citations are calculated by subtracting the number of self-citations from the total number of citations received by the journal’s documents.

International Collaboration accounts for the articles that have been produced by researchers from several countries. The chart shows the ratio of a journal's documents signed by researchers from more than one country; that is including more than one country address.

Not every article in a journal is considered primary research and therefore "citable", this chart shows the ratio of a journal's articles including substantial research (research articles, conference papers and reviews) in three year windows vs. those documents other than research articles, reviews and conference papers.

Ratio of a journal's items, grouped in three years windows, that have been cited at least once vs. those not cited during the following year.

Leave a comment

Name * Required

Email (will not be published) * Required

* Required Cancel

The users of Scimago Journal & Country Rank have the possibility to dialogue through comments linked to a specific journal. The purpose is to have a forum in which general doubts about the processes of publication in the journal, experiences and other issues derived from the publication of papers are resolved. For topics on particular articles, maintain the dialogue through the usual channels with your editor.

Follow us on @ScimagoJR Scimago Lab , Copyright 2007-2022. Data Source: Scopus®

Cookie settings

Cookie Policy

Legal Notice

Privacy Policy

On The Site

Harvard educational review.

Edited by Maya Alkateb-Chami, Jane Choi, Jeannette Garcia Coppersmith, Ron Grady, Phoebe A. Grant-Robinson, Pennie M. Gregory, Jennifer Ha, Woohee Kim, Catherine E. Pitcher, Elizabeth Salinas, Caroline Tucker, Kemeyawi Q. Wahpepah

Individuals

Institutions.

- Read the journal here

Journal Information

- ISSN: 0017-8055

- eISSN: 1943-5045

- Keywords: scholarly journal, education research

- First Issue: 1930

- Frequency: Quarterly

Description

The Harvard Educational Review (HER) is a scholarly journal of opinion and research in education. The Editorial Board aims to publish pieces from interdisciplinary and wide-ranging fields that advance our understanding of educational theory, equity, and practice. HER encourages submissions from established and emerging scholars, as well as from practitioners working in the field of education. Since its founding in 1930, HER has been central to elevating pieces and debates that tackle various dimensions of educational justice, with circulation to researchers, policymakers, teachers, and administrators.

Our Editorial Board is composed entirely of doctoral students from the Harvard Graduate School of Education who review all manuscripts considered for publication. For more information on the current Editorial Board, please see here.

A subscription to the Review includes access to the full-text electronic archives at our Subscribers-Only-Website .

Editorial Board

2023-2024 Harvard Educational Review Editorial Board Members

Maya Alkateb-Chami Development and Partnerships Editor, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Maya Alkateb-Chami is a PhD student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research focuses on the role of schooling in fostering just futures—specifically in relation to language of instruction policies in multilingual contexts and with a focus on epistemic injustice. Prior to starting doctoral studies, she was the Managing Director of Columbia University’s Human Rights Institute, where she supported and co-led a team of lawyers working to advance human rights through research, education, and advocacy. Prior to that, she was the Executive Director of Jusoor, a nonprofit organization that helps conflict-affected Syrian youth and children pursue their education in four countries. Alkateb-Chami is a Fulbright Scholar and UNESCO cultural heritage expert. She holds an MEd in Language and Literacy from Harvard University; an MSc in Education from Indiana University, Bloomington; and a BA in Political Science from Damascus University, and her research on arts-based youth empowerment won the annual Master’s Thesis Award of the U.S. Society for Education Through Art.

Jane Choi Editor, 2023-2025

Jane Choi is a second-year PhD student in Sociology with broad interests in culture, education, and inequality. Her research examines intra-racial and interracial boundaries in US educational contexts. She has researched legacy and first-generation students at Ivy League colleges, families served by Head Start and Early Head Start programs, and parents of pre-K and kindergarten-age children in the New York City School District. Previously, Jane worked as a Research Assistant in the Family Well-Being and Children’s Development policy area at MDRC and received a BA in Sociology from Columbia University.

Jeannette Garcia Coppersmith Content Editor, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Jeannette Garcia Coppersmith is a fourth-year Education PhD student in the Human Development, Learning and Teaching concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. A former public middle and high school mathematics teacher and department chair, she is interested in understanding the mechanisms that contribute to disparities in secondary mathematics education, particularly how teacher beliefs and biases intersect with the social-psychological processes and pedagogical choices involved in math teaching. Jeannette holds an EdM in Learning and Teaching from the Harvard Graduate School of Education where she studied as an Urban Scholar and a BA in Environmental Sciences from the University of California, Berkeley.

Ron Grady Editor, 2023-2025

Ron Grady is a second-year doctoral student in the Human Development, Learning, and Teaching concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. His central curiosities involve the social worlds and peer cultures of young children, wondering how lived experience is both constructed within and revealed throughout play, the creation of art and narrative, and through interaction with/production of visual artifacts such as photography and film. Ron also works extensively with educators interested in developing and deepening practices rooted in reflection on, inquiry into, and translation of the social, emotional, and aesthetic aspects of their classroom ecosystems. Prior to his doctoral studies, Ron worked as a preschool teacher in New Orleans. He holds a MS in Early Childhood Education from the Erikson Institute and a BA in Psychology with Honors in Education from Stanford University.

Phoebe A. Grant-Robinson Editor, 2023-2024

Phoebe A. Grant-Robinson is a first year student in the Doctor of Education Leadership(EdLD) program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her ultimate quest is to position all students as drivers of their destiny. Phoebe is passionate about early learning and literacy. She is committed to ensuring that districts and school leaders, have the necessary tools to create equitable learning organizations that facilitate the academic and social well-being of all students. Phoebe is particularly interested in the intersection of homeless students and literacy. Prior to her doctoral studies, Phoebe was a Special Education Instructional Specialist. Supporting a portfolio of more than thirty schools, she facilitated the rollout of New York City’s Special Education Reform. Phoebe also served as an elementary school principal. She holds a BS in Inclusive Education from Syracuse University, and an MS in Curriculum and Instruction from Pace University.

Pennie M. Gregory Editor, 2023-2024

Pennie M. Gregory is a second-year student in the Doctor of Education Leadership (EdLD) program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Pennie was born in Incheon, South Korea and raised in Gary, Indiana. She has decades of experience leading efforts to improve outcomes for students with disabilities first as a special education teacher and then as a school district special education administrator. Prior to her doctoral studies, Pennie helped to create Indiana’s first Aspiring Special Education Leadership Institute (ASELI) and served as its Director. She was also the Capacity Events Director for MelanatED Leaders, an organization created to support educational leaders of color in Indianapolis. Pennie has a unique perspective, having worked with members of the school community, with advocacy organizations, and supporting state special education leaders. Pennie holds an EdM in Education Leadership from Marian University.

Jennifer Ha Editor, 2023-2025

Jen Ha is a second-year PhD student in the Culture, Institutions, and Society concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research explores how high school students learn to write personal narratives for school applications, scholarships, and professional opportunities amidst changing landscapes in college access and admissions. Prior to doctoral studies, Jen served as the Coordinator of Public Humanities at Bard Graduate Center and worked in several roles organizing academic enrichment opportunities and supporting postsecondary planning for students in New Haven and New York City. Jen holds a BA in Humanities from Yale University, where she was an Education Studies Scholar.

Woohee Kim Editor, 2023-2025

Woohee Kim is a PhD student studying youth activists’ civic and pedagogical practices. She is a scholar-activist dedicated to creating spaces for pedagogies of resistance and transformative possibilities. Shaped by her activism and research across South Korea, the US, and the UK, Woohee seeks to interrogate how educational spaces are shaped as cultural and political sites and reshaped by activists as sites of struggle. She hopes to continue exploring the intersections of education, knowledge, power, and resistance.

Catherine E. Pitcher Editor, 2023-2025

Catherine is a second-year doctoral student at Harvard Graduate School of Education in the Culture, Institutions, and Society program. She has over 10 years of experience in education in the US in roles that range from special education teacher to instructional coach to department head to educational game designer. She started working in Palestine in 2017, first teaching, and then designing and implementing educational programming. Currently, she is working on research to understand how Palestinian youth think about and build their futures and continues to lead programming in the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem. She holds an EdM from Harvard in International Education Policy.

Elizabeth Salinas Editor, 2023-2025

Elizabeth Salinas is a doctoral student in the Education Policy and Program Evaluation concentration at HGSE. She is interested in the intersection of higher education and the social safety net and hopes to examine policies that address basic needs insecurity among college students. Before her doctoral studies, Liz was a research director at a public policy consulting firm. There, she supported government, education, and philanthropy leaders by conducting and translating research into clear and actionable information. Previously, Liz served as a high school physics teacher in her hometown in Texas and as a STEM outreach program director at her alma mater. She currently sits on the Board of Directors at Leadership Enterprise for a Diverse America, a nonprofit organization working to diversify the leadership pipeline in the United States. Liz holds a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a master’s degree in higher education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Caroline Tucker Co-Chair, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Caroline Tucker is a fourth-year doctoral student in the Culture, Institutions, and Society concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research focuses on the history and organizational dynamics of women’s colleges as women gained entry into the professions and coeducation took root in the United States. She is also a research assistant for the Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery Initiative’s Subcommittee on Curriculum and the editorial assistant for Into Practice, the pedagogy newsletter distributed by Harvard University’s Office of the Vice Provost for Advances in Learning. Prior to her doctoral studies, Caroline served as an American politics and English teaching fellow in London and worked in college advising. Caroline holds a BA in History from Princeton University, an MA in the Social Sciences from the University of Chicago, and an EdM in Higher Education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Kemeyawi Q. Wahpepah Co-Chair, 2023-2024 Editor, 2022-2024 [email protected]

Kemeyawi Q. Wahpepah (Kickapoo, Sac & Fox) is a fourth-year doctoral student in the Culture, Institutions, and Society concentration at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Their research explores how settler colonialism is addressed in K-12 history and social studies classrooms in the United States. Prior to their doctoral studies, Kemeyawi taught middle and high school English and history for eleven years in Boston and New York City. They hold an MS in Middle Childhood Education from Hunter College and an AB in Social Studies from Harvard University.

Submission Information

Click here to view submission guidelines .

Contact Information

Click here to view contact information for the editorial board and customer service .

Subscriber Support

Individual subscriptions must have an individual name in the given address for shipment. Individual copies are not for multiple readers or libraries. Individual accounts come with a personal username and password for access to online archives. Online access instructions will be attached to your order confirmation e-mail.

Institutional rates apply to libraries and organizations with multiple readers. Institutions receive digital access to content on Meridian from IP addresses via theIPregistry.org (by sending HER your PSI Org ID).

Online access instructions will be attached to your order confirmation e-mail. If you have questions about using theIPregistry.org you may find the answers in their FAQs. Otherwise please let us know at [email protected] .

How to Subscribe

To order online via credit card, please use the subscribe button at the top of this page.

To order by phone, please call 888-437-1437.

Checks can be mailed to Harvard Educational Review C/O Fulco, 30 Broad Street, Suite 6, Denville, NJ 07834. (Please include reference to your subscriber number if you are renewing. Institutions must include their PSI Org ID or follow up with this information via email to [email protected] .)

Permissions

Click here to view permissions information.

Article Submission FAQ

Closing the open call, question: “i have already submitted an article to her and i am awaiting a decision, what can i expect”.

Answer: First, any manuscripts already submitted through the open call and acknowledged by HER, as well as all invited manuscripts, R&R’d manuscripts, and manuscripts currently in production are NOT affected in any way by our pause in open calls. Editors are working to move through all current submissions and you can expect to receive any updates or decisions as we move through each step of our production process. If you have any questions, please contact the Co-Chairs, Caroline Tucker and Kemeyawi Wahpepah at [email protected] .

Question: “Can you share more about why you are closing the open call?”

Answer: As a graduate student run journal, we perform our editorial tasks in addition to our daily lives as doctoral students. We have been (and continue to be) incredibly grateful for the authors who share their work with us. In closing the open call, we hope to give ourselves time to review each manuscript in the best manner possible.

Submissions

Question: “what manuscripts are a good fit for her ”.

Answer: As a generalist scholarly journal, HER publishes on a wide range of topics within the field of education and related disciplines. We receive many articles that deserve publication, but due to the restrictions of print publication, we are only able to publish very few in the journal. The originality and import of the findings, as well as the accessibility of a piece to HER’s interdisciplinary, international audience which includes education practitioners, are key criteria in determining if an article will be selected for publication.

We strongly recommend that prospective authors review the current and past issues of HER to see the types of articles we have published recently. If you are unsure whether your manuscript is a good fit, please reach out to the Content Editor at [email protected] .

Question: “What makes HER a developmental journal?”

Answer: Supporting the development of high-quality education research is a key tenet of HER’s mission. HER promotes this development through offering comprehensive feedback to authors. All manuscripts that pass the first stage of our review process (see below) receive detailed feedback. For accepted manuscripts, HER also has a unique feedback process called casting whereby two editors carefully read a manuscript and offer overarching suggestions to strengthen and clarify the argument.

Question: “What is a Voices piece and how does it differ from an essay?”

Answer: Voices pieces are first-person reflections about an education-related topic rather than empirical or theoretical essays. Our strongest pieces have often come from educators and policy makers who draw on their personal experiences in the education field. Although they may not present data or generate theory, Voices pieces should still advance a cogent argument, drawing on appropriate literature to support any claims asserted. For examples of Voices pieces, please see Alvarez et al. (2021) and Snow (2021).

Question: “Does HER accept Book Note or book review submissions?”

Answer: No, all Book Notes are written internally by members of the Editorial Board.

Question: “If I want to submit a book for review consideration, who do I contact?”

Answer: Please send details about your book to the Content Editor at [email protected].

Manuscript Formatting

Question: “the submission guidelines state that manuscripts should be a maximum of 9,000 words – including abstract, appendices, and references. is this applicable only for research articles, or should the word count limit be followed for other manuscripts, such as essays”.

Answer: The 9,000-word limit is the same for all categories of manuscripts.

Question: “We are trying to figure out the best way to mask our names in the references. Is it OK if we do not cite any of our references in the reference list? Our names have been removed in the in-text citations. We just cite Author (date).”

Answer: Any references that identify the author/s in the text must be masked or made anonymous (e.g., instead of citing “Field & Bloom, 2007,” cite “Author/s, 2007”). For the reference list, place the citations alphabetically as “Author/s. (2007)” You can also indicate that details are omitted for blind review. Articles can also be blinded effectively by use of the third person in the manuscript. For example, rather than “in an earlier article, we showed that” substitute something like “as has been shown in Field & Bloom, 2007.” In this case, there is no need to mask the reference in the list. Please do not submit a title page as part of your manuscript. We will capture the contact information and any author statement about the fit and scope of the work in the submission form. Finally, please save the uploaded manuscript as the title of the manuscript and do not include the author/s name/s.

Invitations

Question: “can i be invited to submit a manuscript how”.

Answer: If you think your manuscript is a strong fit for HER, we welcome your request for invitation. Invited manuscripts receive one round of feedback from Editors before the piece enters the formal review process. To submit information about your manuscript for the Board to consider for invitation, please fill out the Invitation Request Form. Please provide as many details as possible. Whether we could invite your manuscript depends on the interest and availability of the current Board. Once you submit the form, we will give you an update in about 2–3 weeks on whether there are Editors who are interested in inviting your manuscript.

Review Timeline

Question: “who reviews manuscripts”.

Answer: All manuscripts are reviewed by the Editorial Board composed of doctoral students at Harvard University.

Question: “What is the HER evaluation process as a student-run journal?”

Answer: HER does not utilize the traditional external peer review process and instead has an internal, two-stage review procedure.

Upon submission, every manuscript receives a preliminary assessment by the Content Editor to confirm that the formatting requirements have been carefully followed in preparation of the manuscript, and that the manuscript is in accord with the scope and aim of the journal. The manuscript then formally enters the review process.

In the first stage of review, all manuscripts are read by a minimum of two Editorial Board members. During the second stage of review, manuscripts are read by the full Editorial Board at a weekly meeting.

Question: “How long after submission can I expect a decision on my manuscript?”

Answer: It usually takes 6 to 10 weeks for a manuscript to complete the first stage of review and an additional 12 weeks for a manuscript to complete the second stage. Due to time constraints and the large volume of manuscripts received, HER only provides detailed comments on manuscripts that complete the second stage of review.

Question: “How soon are accepted pieces published?”

Answer: The date of publication depends entirely on how many manuscripts are already in the queue for an issue. Typically, however, it takes about 6 months post-acceptance for a piece to be published.

Submission Process

Question: “how do i submit a manuscript for publication in her”.

Answer: Manuscripts are submitted through HER’s Submittable platform, accessible here. All first-time submitters must create an account to access the platform. You can find details on our submission guidelines on our Submissions page.

Rick Hess Straight Up

Education policy maven Rick Hess of the American Enterprise Institute think tank offers straight talk on matters of policy, politics, research, and reform. Read more from this blog.

Is Education Research Too Political?

- Share article

On Monday, I talked with departing Institute of Education Sciences Director Mark Schneider, who just wrapped up his six-year term. In our conversation, he argued for newer and better research centers at IES, along with a heightened commitment to producing timely and accessible reports. Well, as anyone who knows Mark well can attest, he almost always has more to say. I thought I’d reach back out and see if he had anything else he wanted to get off his mind. Here is Part Two of our conversation.

Rick: On Monday, you mentioned that Marguerite Roza, Emily Oster, and Sean Reardon are doing good, serious work on education topics and releasing it in a timely fashion. Can you say a bit about what they’re doing right and why NCES isn’t meeting that need?

Mark : As noted on Monday, the most telling example is the collection of school-level finance data. Not only are these data required by law, they are also among the most important pieces of information needed to understand the distribution of resources and to relate detailed expenditure data to school outcomes. But despite years of pressure—from Jim Blew, who headed the policy division of ED during the last few years of the DeVos era, from me, and from many others—NCES has never produced timely district financial data and has yet to produce complete school-by-school financials. District financials are released more than two years after the close of the fiscal year, and school-by-school financial pilot data dating back to FY18 have not yet been released. Looking ahead, NCES has promised to release its first set of complete FY22 school-level financials at the end of 2024—again, over two years after the close of the fiscal year . Assuming NCES meets its promise—a risky bet, given past missed deadlines—this would be “fast” by government standards—but far too slow to meet real-world needs.

Rick : What’s responsible for this?

Mark: Much of the problem is that NCES uses an antiquated approach to data collection, issuing a uniform survey that doesn’t match up to different state systems and then waiting for all submissions before releasing datasets. In contrast, teams from Georgetown, Brown, Stanford, and others grab data directly from the source and then convert them into a more standardized format. Teams then release the state-by-state files as they are available instead of holding it all until the very last state has a clean file. The process is far faster. For instance, Georgetown’s NERD$ site—run by Roza—is posting FY23 school-by-school financial files for some states in as few as six to eight months after the close of the fiscal year. With the quick turnaround, district leaders can, for example, marry the finance data with Stanford’s SEDA performance data and use it to inform decisions during the next budget season.

Rick : OK. So, what’s some of this other work that you flagged?

Mark : Similarly, Emily Oster’s work on school closures during the pandemic was released faster than NCES’s and its coverage was more comprehensive. In part because of NCES’s lagging performance, I was able to get additional money from Congress to set up the School Pulse Survey, which has finally given NCES a tool for gathering close to real-time information about conditions in schools. Fair warning, though: NCES calls it “experimental,” which means they are lying in wait to encumber it with more and more statistical tests that will likely delay the release of the data.

Oster and Sean Reardon have also been far ahead of NCES in gathering and releasing detailed data on student performance. Reardon’s Educational Opportunity Project presents detailed and timely information about COVID-related learning loss and recovery. Oster is also working on releasing more detailed and extensive data on student assessment from all states. To this point, they have released data through 2023. In contrast, NCES’s EdFacts promised the 2022 data in December 2023, but it’s not been released yet. Here’s an additional wrinkle: Oster did her work with one salaried employee and a team of undergrads. EdFacts costs around $13 million per year.

Rick : I’ve been struck that, during Secretary Cardona’s tenure, political appointees have gotten far more involved in the release of NAEP results and used the releases to promote administration talking points more than they have in past administrations. How concerned should we be about IES getting caught up in our partisan divides?

Mark: I was both lucky and happy to serve during both the Trump and Biden administrations. Although appointed by Trump, I have found that most of my dealings with senior leaders appointed by Biden have been quite good. But will that political distance and professionalism hold in a second administration of either major candidate? The signs are not good. For instance, IES has an advisory board called the National Board of Education Sciences, or NBES. When the Obama administration was on its way out the door, it tried to fill NBES with their appointees. However, the commissions were never fully executed, and the Trump administration refused to honor the unfinished appointments. Both administrations were within their legal rights to take these actions—but we will still need to see what political ramifications follow.

When I assumed the IES director’s role about halfway through the Trump administration, there were few people on the board, all holdovers from the Obama administration. It was very hard to get the White House to pay attention to the open seats, and I was only able to get three people, all high quality, appointed to the board. At the end of 2020, on his way out the door, Trump appointed a whole bunch of people to the board, many of whose qualifications raised eyebrows. When Biden took office, those commissions had not been finalized, leaving the board consisting of the three people I was able to get appointed. One morning, each of them received an email saying that they had to resign by the end of the day or be fired. The administration then appointed 14 people to the 15-person board. I fear that if the Republicans win the presidency this fall, they will fire the board and replace it with people more to their liking, making what should be a nonpartisan science board highly politicized. I can’t help but wonder if that will lead to the politicization of the director’s tenure.

Rick: Looking outside of IES, it certainly feels to me like the professional education research organizations have become increasingly ideological over the years. Is that a valid criticism? If so, what might help?

Mark: I agree. In 1996, mathematics professor Alan Sokal published the paper “ Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity ” as a hoax to show the shallowness of postmodern critical theory. When he wrote it, I’m sure he was hoping to put an end to that line of work. But, as James Meigs notes in a 2021 Commentary piece: “Sokal meant his essay as a parodic warning. Twenty-five years later, it appears that the Sokal Hoax was actually an instruction manual.” Rick, as you recall, for years, as the AERA annual conference approached, you would go through the program and identify what you considered the most bizarre takes on education. I’m not sure that you could do this today, since you’d have to publish just about the entire program.

Rick: Oh, man, that takes me back. Yeah, I eventually gave that up. I’d hoped that shame could help discourage some of the sillier stuff, but it felt, like you note, that the silly stuff won out. Why is that?

Mark: Education research is highly ideologically driven. If DEI has affected more established and rigorous sciences, which it has, then what can we expect from a far weaker scientific field such as ours? As Meigs noted about Sokal’s paper turning into an instruction manual, I guess your lists could be viewed as a guide to the future work in education.

Rick: Here’s a final question. If you could leave your successor at IES with one piece of advice, what would it be?

Mark: My daughter told me that she learned this parable while in business school.

A new executive is meeting with the executive she is replacing and asks for advice. The outgoing exec says, “I left three envelopes in the desk drawer. Open them sequentially as crises emerge.”

Sure enough, at the inevitable first crisis, the new exec opened the first envelop, which read: “Blame your predecessor.” At the second crisis, the exec opened the second envelop, which read: “Apologize and swear to do better.” Then the third crisis showed up, and the third envelop read: “Write three letters.”

When I pass the baton, I hope that I have gotten IES a little further down the track than people expected. But the race is long, there’s a lot of work left unfinished, and the demand for accountability and innovation won’t go away any time soon.

Oh, and finally, the next director should pray that we don’t have another pandemic. While there are many reasons we should hope never to see a pandemic again, from a narrow perspective, COVID punched a two-year hole in my tenure, limiting what I was able to accomplish.

The opinions expressed in Rick Hess Straight Up are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Frontiers in Medicine

- Healthcare Professions Education

- Research Topics

Impact of Technology on Human Behaviors in Medical Professions Education

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

Human behaviors are essential in understanding how individuals engage in medical science academic activities. Healthcare systems across the globe have witnessed a significant shift in recent years by integrating technology in innovating new methods and practices to improve educational practices. Therefore, ...

Keywords : healthcare education, medical education, teachers’ behavior, students’ behavior, human behavior, technology in medical sciences, program development, curriculum development, teacher and student performance

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines, participating journals.

Manuscripts can be submitted to this Research Topic via the following journals:

total views

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

- Open access

- Published: 05 December 2023

A scoping review to identify and organize literature trends of bias research within medical student and resident education

- Brianne E. Lewis 1 &

- Akshata R. Naik 2

BMC Medical Education volume 23 , Article number: 919 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

829 Accesses

1 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Physician bias refers to the unconscious negative perceptions that physicians have of patients or their conditions. Medical schools and residency programs often incorporate training to reduce biases among their trainees. In order to assess trends and organize available literature, we conducted a scoping review with a goal to categorize different biases that are studied within medical student (MS), resident (Res) and mixed populations (MS and Res). We also characterized these studies based on their research goal as either documenting evidence of bias (EOB), bias intervention (BI) or both. These findings will provide data which can be used to identify gaps and inform future work across these criteria.

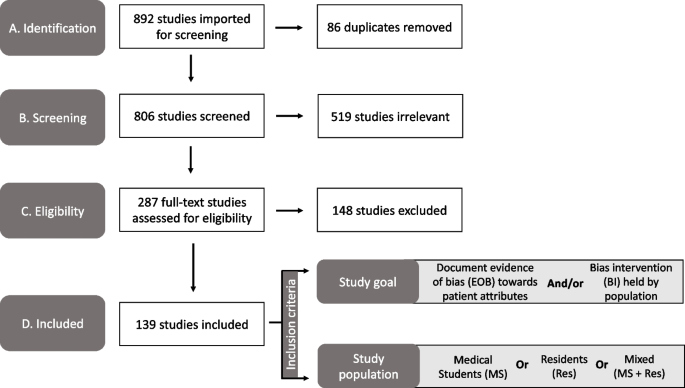

Online databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, WebofScience) were searched for articles published between 1980 and 2021. All references were imported into Covidence for independent screening against inclusion criteria. Conflicts were resolved by deliberation. Studies were sorted by goal: ‘evidence of bias’ and/or ‘bias intervention’, and by population (MS or Res or mixed) andinto descriptive categories of bias.

Of the initial 806 unique papers identified, a total of 139 articles fit the inclusion criteria for data extraction. The included studies were sorted into 11 categories of bias and showed that bias against race/ethnicity, specific diseases/conditions, and weight were the most researched topics. Of the studies included, there was a higher ratio of EOB:BI studies at the MS level. While at the Res level, a lower ratio of EOB:BI was found.

Conclusions

This study will be of interest to institutions, program directors and medical educators who wish to specifically address a category of bias and identify where there is a dearth of research. This study also underscores the need to introduce bias interventions at the MS level.

Peer Review reports

Physician bias ultimately impacts patient care by eroding the physician–patient relationship [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. To overcome this issue, certain states require physicians to report a varying number of hours of implicit bias training as part of their recurring licensing requirement [ 5 , 6 ]. Research efforts on the influence of implicit bias on clinical decision-making gained traction after the “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care” report published in 2003 [ 7 ]. This report sparked a conversation about the impact of bias against women, people of color, and other marginalized groups within healthcare. Bias from a healthcare provider has been shown to affect provider-patient communication and may also influence treatment decisions [ 8 , 9 ]. Nevertheless, opportunities within medical education curriculum are created to evaluate biases at an earlier stage of physician-training and provide instruction to intervene them [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. We aimed to identify trends and organize literature on bias training provided during medical school and residency programs since the meaning of ‘bias’ is broad and encompasses several types of attitudes and predispositions [ 13 ].

Several reviews, narrative or systematic in nature, have been published in the field of bias research in medicine and healthcare [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Many of these reviews have a broad focus on implicit bias and they often fail to define the patient’s specific attributes- such as age, weight, disease, or condition against which physicians hold their biases. However, two recently published reviews categorized implicit biases into various descriptive characteristics albeit with research goals different than this study [ 17 , 18 ]. The study by Fitzgerald et al. reviewed literature focused on bias among physicians and nurses to highlight its role in healthcare disparities [ 17 ]. While the study by Gonzalez et al. focused on bias curricular interventions across professions related to social determinants of health such as education, law, medicine and social work [ 18 ]. Our research goal was to identify the various bias characteristics that are studied within medical student and/or resident populations and categorize them. Further, we were interested in whether biases were merely identified or if they were intervened. To address these deficits in the field and provide clarity, we utilized a scoping review approach to categorize the literature based on a) the bias addressed and b) the study goal within medical students (MS), residents (Res) and a mixed population (MS and Res).

To date no literature review has organized bias research by specific categories held solely by medical trainees (medical students and/or residents) and quantified intervention studies. We did not perform a quality assessment or outcome evaluation of the bias intervention strategies, as it was not the goal of this work and is standard with a scoping review methodology [ 19 , 20 ]. By generating a comprehensive list of bias categories researched among medical trainee population, we highlight areas of opportunity for future implicit bias research specifically within the undergraduate and graduate medical education curriculum. We anticipate that the results from this scoping review will be useful for educators, administrators, and stakeholders seeking to implement active programs or workshops that intervene specific biases in pre-clinical medical education and prepare physicians-in-training for patient encounters. Additionally, behavioral scientists who seek to support clinicians, and develop debiasing theories [ 21 ] and models may also find our results informative.

We conducted an exhaustive and focused scoping review and followed the methodological framework for scoping reviews as previously described in the literature [ 20 , 22 ]. This study aligned with the four goals of a scoping review [ 20 ]. We followed the first five out of the six steps outlined by Arksey and O’Malley’s to ensure our review’s validity 1) identifying the research question 2) identifying relevant studies 3) selecting the studies 4) charting the data and 5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results [ 22 ]. We did not follow the optional sixth step of undertaking consultation with key stakeholders as it was not needed to address our research question it [ 23 ]. Furthermore, we used Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) that aided in managing steps 2–5 presented above.

Research question, search strategy and inclusion criteria

The purpose of this study was to identify trends in bias research at the medical school and residency level. Prior to conducting our literature search we developed our research question and detailed the inclusion criteria, and generated the search syntax with the assistance from a medical librarian. Search syntax was adjusted to the requirements of the database. We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO using MeSH terms shown below.

Bias* [ti] OR prejudice*[ti] OR racism[ti] OR homophobia[ti] OR mistreatment[ti] OR sexism[ti] OR ageism[ti]) AND (prejudice [mh] OR "Bias"[Mesh:NoExp]) AND (Education, Medical [mh] OR Schools, Medical [mh] OR students, medical [mh] OR Internship and Residency [mh] OR “undergraduate medical education” OR “graduate medical education” OR “medical resident” OR “medical residents” OR “medical residency” OR “medical residencies” OR “medical schools” OR “medical school” OR “medical students” OR “medical student”) AND (curriculum [mh] OR program evaluation [mh] OR program development [mh] OR language* OR teaching OR material* OR instruction* OR train* OR program* OR curricul* OR workshop*

Our inclusion criteria incorporated studies which were either original research articles, or review articles that synthesized new data. We excluded publications that were not peer-reviewed or supported with data such as narrative reviews, opinion pieces, editorials, perspectives and commentaries. We included studies outside of the U.S. since the purpose of this work was to generate a comprehensive list of biases. Physicians, regardless of their country of origin, can hold biases against specific patient attributes [ 17 ]. Furthermore, physicians may practice in a different country than where they trained [ 24 ]. Manuscripts were included if they were published in the English language for which full-texts were available. Since the goal of this scoping review was to assess trends, we accepted studies published from 1980–2021.

Our inclusion criteria also considered the goal and the population of the study. We defined the study goal as either that documented evidence of bias or a program directed bias intervention. Evidence of bias (EOB) had to originate from the medical trainee regarding a patient attribute. Bias intervention (BI) studies involved strategies to counter biases such as activities, workshops, seminars or curricular innovations. The population studied had to include medical students (MS) or residents (Res) or mixed. We defined the study population as ‘mixed’ when it consisted of both MS and Res. Studies conducted on other healthcare professionals were included if MS or Res were also studied. Our search criteria excluded studies that documented bias against medical professionals (students, residents and clinicians) either by patients, medical schools, healthcare administrators or others, and was focused on studies where the biases were solely held by medical trainees (MS and Res).

Data extraction and analysis

Following the initial database search, references were downloaded and bulk uploaded into Covidence and duplicates were removed. After the initial screening of title and abstracts, full-texts were reviewed. Authors independently completed title and abstract screening, and full text reviews. Any conflicts at the stage of abstract screening were moved to full-text screening. Conflicts during full-text screening were resolved by deliberation and referring to the inclusion and exclusion criteria detailed in the research protocol. The level of agreement between the two authors for full text reviews as measured by inter-rater reliability was 0.72 (Cohen’s Kappa).

A data extraction template was created in Covidence to extract data from included full texts. Data extraction template included the following variables; country in which the study was conducted, year of publication, goal of the study (EOB, BI or both), population of the study (MS, Res or mixed) and the type of bias studied. Final data was exported to Microsoft Excel for quantification. For charting our data and categorizing the included studies, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews(PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [ 25 ]. Results from this scoping review study are meant to provide a visual synthesis of existing bias research and identify gaps in knowledge.

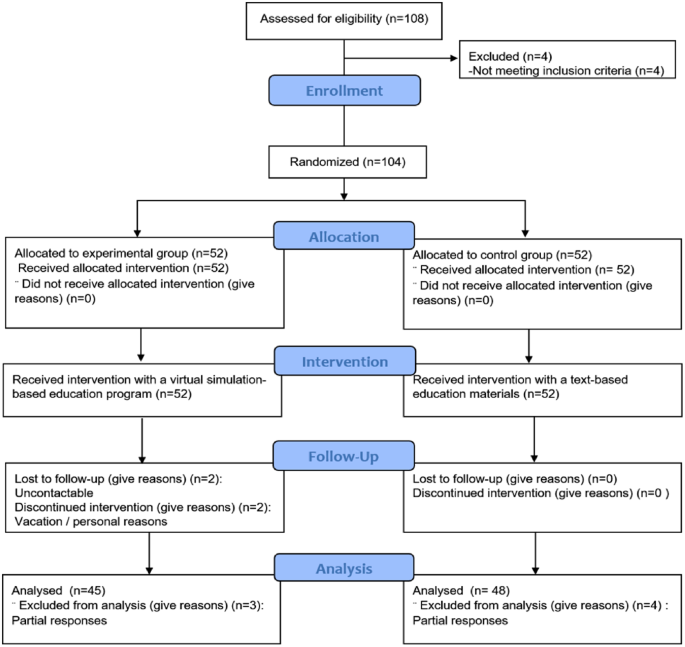

Study selection

Our search strategy yielded a total of 892 unique abstracts which were imported into ‘Covidence’ for screening. A total of 86 duplicate references were removed. Then, 806 titles and abstracts were screened for relevance independently by the authors and 519 studies were excluded at this stage. Any conflicts among the reviewers at this stage were resolved by discussion and referring to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then a full text review of the remaining 287 papers was completed by the authors against the inclusion criteria for eligibility. Full text review was also conducted independently by the authors and any conflicts were resolved upon discussion. Finally, we included 139 studies which were used for data extraction (Fig. 1 ).

PRISMA diagram of the study selection process used in our scoping review to identify the bias categories that have been reported within medical education literature. Study took place from 2021–2022. Abbreviation: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Publication trends in bias research

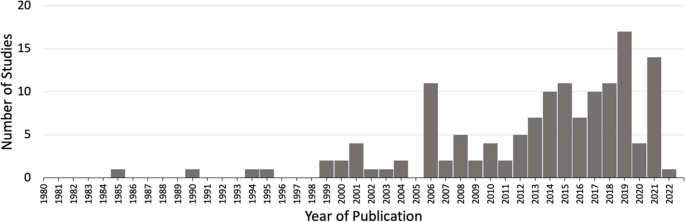

First, we charted the studies to demonstrate the timeline of research focused on bias within the study population of our interest (MS or Res or mixed). Our analysis revealed an increase in publications with respect to time (Fig. 2 ). Of the 139 included studies, fewer studies were published prior to 2001, with a total of only eight papers being published from the years 1985–2000. A substantial increase in publications occurred after 2004, with 2019 being the peak year where most of the studies pertaining to bias were published (Fig. 2 ).

Studies matching inclusion criteria mapped by year of publication. Search criteria included studies addressing bias from 1980–2021 within medical students (MS) or residents (Res) or mixed (MS + Res) populations. * Publication in 2022 was published online ahead of print

Overview of included studies

We present a descriptive analysis of the 139 included studies in Table 1 based on the following parameters: study location, goal of the study, population of the study and the category of bias studied. All of the above parameters except the category of bias included a denominator of 139 studies. Several studies addressed more than one bias characteristic; therefore, we documented 163 biases sorted in 11 categories over the 139 papers. The bias categories that we generated and their respective occurrences are listed in Table 1 . Of the 139 studies that were included, most studies originated in the United States ( n = 89/139, 64%) and Europe ( n = 20/139, 20%).

Sorting of included research by bias category

We grouped the 139 included studies depending on the patient attribute or the descriptive characteristic against which the bias was studied (Table 1 ). By sorting the studies into different bias categories, we aimed to not only quantitate the amount of research addressing a particular topic of bias, but also reveal the biases that are understudied.

Through our analysis, we generated 11 descriptive categories against which bias was studied: Age, physical disability, education level, biological sex, disease or condition, LGBTQ + , non-specified, race/ethnicity, rural/urban, socio-economic status, and weight (Table 1 ). “Age” and “weight” categories included papers that studied bias against older population and higher weight individuals, respectively. The categories “education level” and “socio-economic status” included papers that studied bias against individuals with low education level and individuals belonging to low socioeconomic status, respectively. Within the bias category named ‘biological sex’, we included papers that studied bias against individuals perceived as women/females. Papers that studied bias against gender-identity or sexual orientation were included in its own category named, ‘LGBTQ + ’. The bias category, ‘disease or condition’ was broad and included research on bias against any patient with a specific disease, condition or lifestyle. Studies included in this category researched bias against any physical illnesses, mental illnesses, or sexually transmitted infections. It also included studies that addressed bias against a treatment such as transplant or pain management. It was not significant to report these as individual categories but rather as a whole with a common underlying theme. Rural/urban bias referred to bias that was held against a person based on their place of residence. Studies grouped together in the ‘non-specified bias’ category explored bias without specifying any descriptive characteristic in their methods. These studies did not address any specific bias characteristic in particular but consisted of a study population of our interest (MS or Res or mixed). Based on our analysis, the top five most studied bias categories in our included population within medical education literature were: racial or ethnic bias ( n = 39/163, 24%), disease or condition bias ( n = 29/163, 18%), weight bias ( n = 22/163, 13%), LGBTQ + bias ( n = 21/163, 13%), and age bias ( n = 16/163, 10%) which are presented in Table 1 .

Sorting of included research by population

In order to understand the distribution of bias research based on their populations examined, we sorted the included studies in one of the following: medical students (MS), residents (Res) or mixed (Table 1 ). The following distributions were observed: medical students only ( n = 105/139, 76%), residents only ( n = 19/139, 14%) or mixed which consisted of both medical students and residents ( n = 15/139, 11%). In combination, these results demonstrate that medical educators have focused bias research efforts primarily on medical student populations.

Sorting of included research by goal

A critical component of this scoping review was to quantify the research goal of the included studies within each of the bias categories. We defined the research goal as either to document evidence of bias (EOB) or to evaluate a bias intervention (BI) (see Fig. 1 for inclusion criteria). Some of the included studies focused on both, documenting evidence in addition to intervening biases and those studies were grouped separately. The analysis revealed that 69/139 (50%) of the included studies focused exclusively on documenting evidence of bias (EOB). There were fewer studies ( n = 51/139, 37%) which solely focused on bias interventions such as programs, seminars or curricular innovations. A small minority of the included studies were more comprehensive in that they documented EOB followed by an intervention strategy ( n = 19/139, 11%). These results demonstrate that most bias research is dedicated to documenting evidence of bias among these groups rather than evaluating a bias intervention strategy.

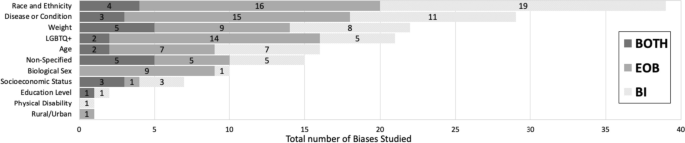

Research goal distribution

Our next objective was to calculate the distribution of studies with respect to the study goal (EOB, BI or both), within the 163 biases studied across the 139 papers as calculated in Table 1 . In general, the goal of the studies favors documenting evidence of bias with the exception of race/ethnic bias which is more focused on bias intervention (Fig. 3 ). Fewer studies were aimed at both, documenting evidence then providing an intervention, across all bias categories.

Sorting of total biases ( n = 163) within medical students or residents or a mixed population based on the bias category . Dark grey indicates studies with a dual goal, to document evidence of bias and to intervene bias. Medium grey bars indicate studies which focused on documenting evidence of bias. Light grey bars indicate studies focused on bias intervention within these populations. Numbers inside the bars indicate the total number of biases for the respective study goal. * Non-specified bias includes studies which focused on implicit bias but did not mention the type of bias investigated

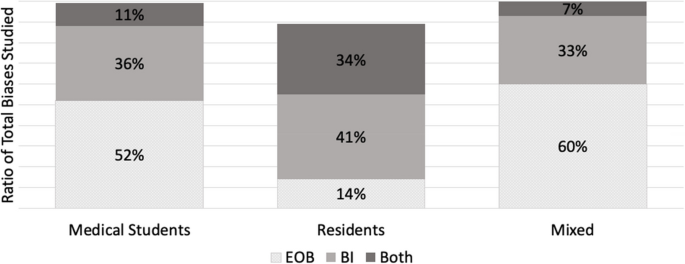

Furthermore, we also calculated the ratio of EOB, BI and both (EOB + BI) within each of our population of interest (MS; n = 122, Res; n = 26 and mixed; n = 15) for the 163 biases observed in our included studies. Over half ( n = 64/122, 52%) of the total bias occurrences in MS were focused on documenting EOB (Fig. 4 ). Contrastingly, a shift was observed within resident populations where most biases addressed were aimed at intervention ( n = 12/26, 41%) rather than EOB ( n = 4/26, 14%) (Fig. 4 ). Studies which included both MS and Res (mixed) were primarily focused on documenting EOB ( n = 9/15, 60%), with 33% ( n = 5/15) aimed at bias intervention and 7% ( n = 1/15) which did both (Fig. 4 ). Although far fewer studies were documented in the Res population it is important to highlight that most of these studies were focused on bias intervention when compared to MS population where we documented a majority of studies focused on evidence of bias.

A ratio of the study goal for the total biases ( n = 163) mapped within each of the study population (MS, Res and Mixed). A study goal with a) documenting evidence of bias (EOB) is depicted in dotted grey, b) bias intervention (BI) in medium grey, and c) a dual focus (EOB + BI) is depicted in dark grey. * N = 122 for medical student studies. b N = 26 for residents. c N = 15 for mixed

Addressing biases at an earlier stage of medical career is critical for future physicians engaging with diverse patients, since it is established that bias negatively influences provider-patient interactions [ 171 ], clinical decision-making [ 172 ] and reduces favorable treatment outcomes [ 2 ]. We set out with an intention to explore how bias is addressed within the medical curriculum. Our research question was: how has the trend in bias research changed over time, more specifically a) what is the timeline of papers published? b) what bias characteristics have been studied in the physician-trainee population and c) how are these biases addressed? With the introduction of ‘standards of diversity’ by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, along with the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the American Medical Association (AMA) [ 173 , 174 ], we certainly expected and observed a sustained uptick in research pertaining to bias. As shown here, research addressing bias in the target population (MS and Res) is on the rise, however only 139 papers fit our inclusion criteria. Of these studies, nearly 90% have been published since 2005 after the “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care” report was published in 2003 [ 7 ]. However, given the well documented effects of physician held bias, we anticipated significantly more number of studies focused on bias at the medical student or resident level.

A key component from this study was that we generated descriptive categories of biases. Sorting the biases into descriptive categories helps to identify a more targeted approach for a specific bias intervention, rather than to broadly intervene bias as a whole. In fact, our analysis found a number of publications (labeled “non-specified bias” in Table 1 ) which studied implicit bias without specifying the patient attribute or the characteristic that the bias was against. In total, we generated 11 descriptive categories of bias from our scoping review which are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3 . Furthermore, our bias descriptors grouped similar kinds of biases within a single category. For example, the category, “disease or condition” included papers that studied bias against any type of disease (Mental illness, HIV stigma, diabetes), condition (Pain management), or lifestyle. We neither performed a qualitative assessment of the studies nor did we test the efficacy of the bias intervention studies and consider it a future direction of this work.

Evidence suggests that medical educators and healthcare professionals are struggling to find the appropriate approach to intervene biases [ 175 , 176 , 177 ] So far, bias reduction, bias reflection and bias management approaches have been proposed [ 26 , 27 , 178 ]. Previous implicit bias intervention strategies have been shown to be ineffective when biased attitudes of participants were assessed after a lag [ 179 ]. Understanding the descriptive categories of bias and previous existing research efforts, as we present here is only a fraction of the challenge. The theory of “cognitive bias” [ 180 ] and related branches of research [ 13 , 181 , 182 , 183 , 184 ] have been studied in the field of psychology for over three decades. It is only recently that cognitive bias theory has been applied to the field of medical education medicine, to explain its negative influence on clinical decision-making pertaining only to racial minorities [ 1 , 2 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 185 ]. In order to elicit meaningful changes with respect to targeted bias intervention, it is necessary to understand the psychological underpinnings (attitudes) leading to a certain descriptive category of bias (behaviors). The questions which medical educators need to ask are: a) Can these descriptive biases be identified under certain type/s of cognitive errors that elicits the bias and vice versa b) Are we working towards an attitude change which can elicit a sustained positive behavior change among healthcare professionals? And most importantly, c) are we creating a culture where participants voluntarily enroll themselves in bias interventions as opposed to being mandated to participate? Cognitive psychologists and behavioral scientists are well-positioned to help us find answers to these questions as they understand human behavior. Therefore, an interdisciplinary approach, a marriage between cognitive psychologists and medical educators, is key in targeting biases held by medical students, residents, and ultimately future physicians. This review may also be of interest to behavioral psychologists, keen on providing targeted intervening strategies to clinicians depending on the characteristics (age, weight, sex or race) the portrayed bias is against. Further, instead of an individualized approach, we need to strive for systemic changes and evidence-based strategies to intervene biases.

The next element in change is directing intervention strategies at the right stage in clinical education. Our study demonstrated that most of the research collected at the medical student level was focused on documenting evidence of bias. Although the overall number of studies at the resident level were fewer than at the medical student level, the ratio of research in favor of bias intervention was higher at the resident level (see Fig. 3 ). However, it could be helpful to focus on bias intervention earlier in learning, rather than at a later stage [ 186 ]. Additionally, educational resources such as textbooks, preparatory materials, and educators themselves are potential sources of propagating biases and therefore need constant evaluation against best practices [ 187 , 188 ].

This study has limitations. First, the list of the descriptive bias categories that we generated was not grounded in any particular theory so assigning a category was subjective. Additionally, there were studies that were categorized as “nonspecified” bias as the studies themselves did not mention the specific type of bias that they were addressing. Moreover, we had to exclude numerous publications solely because they were not evidence-based and were either perspectives, commentaries or opinion pieces. Finally, there were overall fewer studies focused on the resident population, so the calculated ratio of MS:Res studies did not compare similar sample sizes.

Future directions of our study include working with behavioral scientists to categorize these bias characteristics (Table 1 ) into cognitive error types [ 189 ]. Additionally, we aim to assess the effectiveness of the intervention strategies and categorize the approach of the intervention strategies.

The primary goal of our review was to organize, compare and quantify literature pertaining to bias within medical school curricula and residency programs. We neither performed a qualitative assessment of the studies nor did we test the efficacy of studies that were sorted into “bias intervention” as is typical of scoping reviews [ 22 ]. In summary, our research identified 11 descriptive categories of biases studied within medical students and resident populations with “race and ethnicity”, “disease or condition”, “weight”, “LGBTQ + ” and “age” being the top five most studied biases. Additionally, we found a greater number of studies conducted in medical students (105/139) when compared to residents (19/139). However, most of the studies in the resident population focused on bias intervention. The results from our review highlight the following gaps: a) bias categories where more research is needed, b) biases that are studied within medical school versus in residency programs and c) study focus in terms of demonstrating the presence of bias or working towards bias intervention.

This review provides a visual analysis of the known categories of bias addressed within the medical school curriculum and in residency programs in addition to providing a comparison of studies with respect to the study goal within medical education literature. The results from our review should be of interest to community organizations, institutions, program directors and medical educators interested in knowing and understanding the types of bias existing within healthcare populations. It might be of special interest to researchers who wish to explore other types of biases that have been understudied within medical school and resident populations, thus filling the gaps existing in bias research.

Despite the number of studies designed to provide bias intervention for MS and Res populations, and an overall cultural shift to be aware of one’s own biases, biases held by both medical students and residents still persist. Further, psychologists have recently demonstrated the ineffectiveness of some bias intervention efforts [ 179 , 190 ]. Therefore, it is perhaps unrealistic to expect these biases to be eliminated altogether. However, effective intervention strategies grounded in cognitive psychology should be implemented earlier on in medical training. Our focus should be on providing evidence-based approaches and safe spaces for an attitude and culture change, so as to induce actionable behavioral changes.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Medical student

Evidence of bias

- Bias intervention

Hagiwara N, Mezuk B, Elston Lafata J, Vrana SR, Fetters MD. Study protocol for investigating physician communication behaviours that link physician implicit racial bias and patient outcomes in Black patients with type 2 diabetes using an exploratory sequential mixed methods design. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e022623.

Article Google Scholar

Haider AH, Schneider EB, Sriram N, Dossick DS, Scott VK, Swoboda SM, Losonczy L, Haut ER, Efron DT, Pronovost PJ, et al. Unconscious race and social class bias among acute care surgical clinicians and clinical treatment decisions. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(5):457–64.

Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Gonzalez R, Albrecht TL, Chapman R, Foster T, Harper FW, Hagiwara N, Hamel LM, Shields AF, et al. The effects of oncologist implicit racial bias in racially discordant oncology interactions. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2874–80.

Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, van Ryn M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2015;16(4):319–26.

Garrett SB, Jones L, Montague A, Fa-Yusuf H, Harris-Taylor J, Powell B, Chan E, Zamarripa S, Hooper S, Chambers Butcher BD. Challenges and opportunities for clinician implicit bias training: insights from perinatal care stakeholders. Health Equity. 2023;7(1):506–19.

Shah HS, Bohlen J. Implicit bias. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

Google Scholar

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. In: Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003. PMID: 25032386.

Dehon E, Weiss N, Jones J, Faulconer W, Hinton E, Sterling S. A systematic review of the impact of physician implicit racial bias on clinical decision making. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(8):895–904.

Oliver MN, Wells KM, Joy-Gaba JA, Hawkins CB, Nosek BA. Do physicians’ implicit views of African Americans affect clinical decision making? J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(2):177–88.

Rincon-Subtirelu M. Education as a tool to modify anti-obesity bias among pediatric residents. Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:77–8.

Gustafsson Sendén M, Renström EA. Gender bias in assessment of future work ability among pain patients - an experimental vignette study of medical students’ assessment. Scand J Pain. 2019;19(2):407–14.

Hardeman RR, Burgess D, Phelan S, Yeazel M, Nelson D, van Ryn M. Medical student socio-demographic characteristics and attitudes toward patient centered care: do race, socioeconomic status and gender matter? A report from the medical student CHANGES study. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(3):350–5.

Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol Rev. 1995;102(1):4–27.

Kruse JA, Collins JL, Vugrin M. Educational strategies used to improve the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of health care students and providers regarding implicit bias: an integrative review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2022;4:100073.

Zestcott CA, Blair IV, Stone J. Examining the presence, consequences, and reduction of implicit bias in health care: a narrative review. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2016;19(4):528–42.

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, Eng E, Day SH, Coyne-Beasley T. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):E60–76.

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19.

Gonzalez CM, Onumah CM, Walker SA, Karp E, Schwartz R, Lypson ML. Implicit bias instruction across disciplines related to the social determinants of health: a scoping review. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2023;28(2):541–87.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Pat C, Geeta S, Sílvia M. Cognitive debiasing 1: origins of bias and theory of debiasing. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(Suppl 2):ii58.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Thomas A, Lubarsky S, Durning SJ, Young ME. Knowledge syntheses in medical education: demystifying scoping reviews. Acad Med. 2017;92(2):161–6.

Hagopian A, Thompson MJ, Fordyce M, Johnson KE, Hart LG. The migration of physicians from sub-Saharan Africa to the United States of America: measures of the African brain drain. Hum Resour Health. 2004;2(1):17.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Teal CR, Shada RE, Gill AC, Thompson BM, Frugé E, Villarreal GB, Haidet P. When best intentions aren’t enough: Helping medical students develop strategies for managing bias about patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 2):S115–8.

Gonzalez CM, Walker SA, Rodriguez N, Noah YS, Marantz PR. Implicit bias recognition and management in interpersonal encounters and the learning environment: a skills-based curriculum for medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11168.

Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(16):4296–301.

Mayfield JJ, Ball EM, Tillery KA, Crandall C, Dexter J, Winer JM, Bosshardt ZM, Welch JH, Dolan E, Fancovic ER, et al. Beyond men, women, or both: a comprehensive, LGBTQ-inclusive, implicit-bias-aware, standardized-patient-based sexual history taking curriculum. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10634.

Morris M, Cooper RL, Ramesh A, Tabatabai M, Arcury TA, Shinn M, Im W, Juarez P, Matthews-Juarez P. Training to reduce LGBTQ-related bias among medical, nursing, and dental students and providers: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):325.

Perdomo J, Tolliver D, Hsu H, He Y, Nash KA, Donatelli S, Mateo C, Akagbosu C, Alizadeh F, Power-Hays A, et al. Health equity rounds: an interdisciplinary case conference to address implicit bias and structural racism for faculty and trainees. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10858.

Sherman MD, Ricco J, Nelson SC, Nezhad SJ, Prasad S. Implicit bias training in a residency program: aiming for enduring effects. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):677–81.

van Ryn M, Hardeman R, Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Dovidio JF, Herrin J, Burke SE, Nelson DB, Perry S, Yeazel M, et al. Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3547 students: a medical student CHANGES study report. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1748–56.

Chary AN, Molina MF, Dadabhoy FZ, Manchanda EC. Addressing racism in medicine through a resident-led health equity retreat. West J Emerg Med. 2020;22(1):41–4.