- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step [Template]

Table of Contents

How To Write a Research Proposal

Writing a Research proposal involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and comprehensive document. Here is an explanation of each step:

1. Title and Abstract

- Choose a concise and descriptive title that reflects the essence of your research.

- Write an abstract summarizing your research question, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes. It should provide a brief overview of your proposal.

2. Introduction:

- Provide an introduction to your research topic, highlighting its significance and relevance.

- Clearly state the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Discuss the background and context of the study, including previous research in the field.

3. Research Objectives

- Outline the specific objectives or aims of your research. These objectives should be clear, achievable, and aligned with the research problem.

4. Literature Review:

- Conduct a comprehensive review of relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings, identify gaps, and highlight how your research will contribute to the existing knowledge.

5. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to employ to address your research objectives.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques you will use.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate and suitable for your research.

6. Timeline:

- Create a timeline or schedule that outlines the major milestones and activities of your research project.

- Break down the research process into smaller tasks and estimate the time required for each task.

7. Resources:

- Identify the resources needed for your research, such as access to specific databases, equipment, or funding.

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources to carry out your research effectively.

8. Ethical Considerations:

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise during your research and explain how you plan to address them.

- If your research involves human subjects, explain how you will ensure their informed consent and privacy.

9. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

- Clearly state the expected outcomes or results of your research.

- Highlight the potential impact and significance of your research in advancing knowledge or addressing practical issues.

10. References:

- Provide a list of all the references cited in your proposal, following a consistent citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

11. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as survey questionnaires, interview guides, or data analysis plans.

Research Proposal Format

The format of a research proposal may vary depending on the specific requirements of the institution or funding agency. However, the following is a commonly used format for a research proposal:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your research proposal, your name, your affiliation or institution, and the date.

2. Abstract:

- Provide a brief summary of your research proposal, highlighting the research problem, objectives, methodology, and expected outcomes.

3. Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic and provide background information.

- State the research problem or question you aim to address.

- Explain the significance and relevance of the research.

- Review relevant literature and studies related to your research topic.

- Summarize key findings and identify gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Explain how your research will contribute to filling those gaps.

5. Research Objectives:

- Clearly state the specific objectives or aims of your research.

- Ensure that the objectives are clear, focused, and aligned with the research problem.

6. Methodology:

- Describe the research design and methodology you plan to use.

- Explain the data collection methods, instruments, and analysis techniques.

- Justify why the chosen methods are appropriate for your research.

7. Timeline:

8. Resources:

- Explain how you will acquire or utilize these resources effectively.

9. Ethical Considerations:

- If applicable, explain how you will ensure informed consent and protect the privacy of research participants.

10. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

11. References:

12. Appendices:

Research Proposal Template

Here’s a template for a research proposal:

1. Introduction:

2. Literature Review:

3. Research Objectives:

4. Methodology:

5. Timeline:

6. Resources:

7. Ethical Considerations:

8. Expected Outcomes and Significance:

9. References:

10. Appendices:

Research Proposal Sample

Title: The Impact of Online Education on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study

1. Introduction

Online education has gained significant prominence in recent years, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes by comparing them with traditional face-to-face instruction. The study will explore various aspects of online education, such as instructional methods, student engagement, and academic performance, to provide insights into the effectiveness of online learning.

2. Objectives

The main objectives of this research are as follows:

- To compare student learning outcomes between online and traditional face-to-face education.

- To examine the factors influencing student engagement in online learning environments.

- To assess the effectiveness of different instructional methods employed in online education.

- To identify challenges and opportunities associated with online education and suggest recommendations for improvement.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study Design

This research will utilize a mixed-methods approach to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The study will include the following components:

3.2 Participants

The research will involve undergraduate students from two universities, one offering online education and the other providing face-to-face instruction. A total of 500 students (250 from each university) will be selected randomly to participate in the study.

3.3 Data Collection

The research will employ the following data collection methods:

- Quantitative: Pre- and post-assessments will be conducted to measure students’ learning outcomes. Data on student demographics and academic performance will also be collected from university records.

- Qualitative: Focus group discussions and individual interviews will be conducted with students to gather their perceptions and experiences regarding online education.

3.4 Data Analysis

Quantitative data will be analyzed using statistical software, employing descriptive statistics, t-tests, and regression analysis. Qualitative data will be transcribed, coded, and analyzed thematically to identify recurring patterns and themes.

4. Ethical Considerations

The study will adhere to ethical guidelines, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Informed consent will be obtained, and participants will have the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

5. Significance and Expected Outcomes

This research will contribute to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence on the impact of online education on student learning outcomes. The findings will help educational institutions and policymakers make informed decisions about incorporating online learning methods and improving the quality of online education. Moreover, the study will identify potential challenges and opportunities related to online education and offer recommendations for enhancing student engagement and overall learning outcomes.

6. Timeline

The proposed research will be conducted over a period of 12 months, including data collection, analysis, and report writing.

The estimated budget for this research includes expenses related to data collection, software licenses, participant compensation, and research assistance. A detailed budget breakdown will be provided in the final research plan.

8. Conclusion

This research proposal aims to investigate the impact of online education on student learning outcomes through a comparative study with traditional face-to-face instruction. By exploring various dimensions of online education, this research will provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and challenges associated with online learning. The findings will contribute to the ongoing discourse on educational practices and help shape future strategies for maximizing student learning outcomes in online education settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide...

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

How to choose an Appropriate Method for Research?

What (Exactly) Is A Research Proposal?

A simple explainer with examples + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020 (Updated April 2023)

Whether you’re nearing the end of your degree and your dissertation is on the horizon, or you’re planning to apply for a PhD program, chances are you’ll need to craft a convincing research proposal . If you’re on this page, you’re probably unsure exactly what the research proposal is all about. Well, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Research Proposal Basics

- What a research proposal is

- What a research proposal needs to cover

- How to structure your research proposal

- Example /sample proposals

- Proposal writing FAQs

- Key takeaways & additional resources

What is a research proposal?

Simply put, a research proposal is a structured, formal document that explains what you plan to research (your research topic), why it’s worth researching (your justification), and how you plan to investigate it (your methodology).

The purpose of the research proposal (its job, so to speak) is to convince your research supervisor, committee or university that your research is suitable (for the requirements of the degree program) and manageable (given the time and resource constraints you will face).

The most important word here is “ convince ” – in other words, your research proposal needs to sell your research idea (to whoever is going to approve it). If it doesn’t convince them (of its suitability and manageability), you’ll need to revise and resubmit . This will cost you valuable time, which will either delay the start of your research or eat into its time allowance (which is bad news).

What goes into a research proposal?

A good dissertation or thesis proposal needs to cover the “ what “, “ why ” and” how ” of the proposed study. Let’s look at each of these attributes in a little more detail:

Your proposal needs to clearly articulate your research topic . This needs to be specific and unambiguous . Your research topic should make it clear exactly what you plan to research and in what context. Here’s an example of a well-articulated research topic:

An investigation into the factors which impact female Generation Y consumer’s likelihood to promote a specific makeup brand to their peers: a British context

As you can see, this topic is extremely clear. From this one line we can see exactly:

- What’s being investigated – factors that make people promote or advocate for a brand of a specific makeup brand

- Who it involves – female Gen-Y consumers

- In what context – the United Kingdom

So, make sure that your research proposal provides a detailed explanation of your research topic . If possible, also briefly outline your research aims and objectives , and perhaps even your research questions (although in some cases you’ll only develop these at a later stage). Needless to say, don’t start writing your proposal until you have a clear topic in mind , or you’ll end up waffling and your research proposal will suffer as a result of this.

Need a helping hand?

As we touched on earlier, it’s not good enough to simply propose a research topic – you need to justify why your topic is original . In other words, what makes it unique ? What gap in the current literature does it fill? If it’s simply a rehash of the existing research, it’s probably not going to get approval – it needs to be fresh.

But, originality alone is not enough. Once you’ve ticked that box, you also need to justify why your proposed topic is important . In other words, what value will it add to the world if you achieve your research aims?

As an example, let’s look at the sample research topic we mentioned earlier (factors impacting brand advocacy). In this case, if the research could uncover relevant factors, these findings would be very useful to marketers in the cosmetics industry, and would, therefore, have commercial value . That is a clear justification for the research.

So, when you’re crafting your research proposal, remember that it’s not enough for a topic to simply be unique. It needs to be useful and value-creating – and you need to convey that value in your proposal. If you’re struggling to find a research topic that makes the cut, watch our video covering how to find a research topic .

It’s all good and well to have a great topic that’s original and valuable, but you’re not going to convince anyone to approve it without discussing the practicalities – in other words:

- How will you actually undertake your research (i.e., your methodology)?

- Is your research methodology appropriate given your research aims?

- Is your approach manageable given your constraints (time, money, etc.)?

While it’s generally not expected that you’ll have a fully fleshed-out methodology at the proposal stage, you’ll likely still need to provide a high-level overview of your research methodology . Here are some important questions you’ll need to address in your research proposal:

- Will you take a qualitative , quantitative or mixed -method approach?

- What sampling strategy will you adopt?

- How will you collect your data (e.g., interviews, surveys, etc)?

- How will you analyse your data (e.g., descriptive and inferential statistics , content analysis, discourse analysis, etc, .)?

- What potential limitations will your methodology carry?

So, be sure to give some thought to the practicalities of your research and have at least a basic methodological plan before you start writing up your proposal. If this all sounds rather intimidating, the video below provides a good introduction to research methodology and the key choices you’ll need to make.

How To Structure A Research Proposal

Now that we’ve covered the key points that need to be addressed in a proposal, you may be wondering, “ But how is a research proposal structured? “.

While the exact structure and format required for a research proposal differs from university to university, there are four “essential ingredients” that commonly make up the structure of a research proposal:

- A rich introduction and background to the proposed research

- An initial literature review covering the existing research

- An overview of the proposed research methodology

- A discussion regarding the practicalities (project plans, timelines, etc.)

In the video below, we unpack each of these four sections, step by step.

Research Proposal Examples/Samples

In the video below, we provide a detailed walkthrough of two successful research proposals (Master’s and PhD-level), as well as our popular free proposal template.

Proposal Writing FAQs

How long should a research proposal be.

This varies tremendously, depending on the university, the field of study (e.g., social sciences vs natural sciences), and the level of the degree (e.g. undergraduate, Masters or PhD) – so it’s always best to check with your university what their specific requirements are before you start planning your proposal.

As a rough guide, a formal research proposal at Masters-level often ranges between 2000-3000 words, while a PhD-level proposal can be far more detailed, ranging from 5000-8000 words. In some cases, a rough outline of the topic is all that’s needed, while in other cases, universities expect a very detailed proposal that essentially forms the first three chapters of the dissertation or thesis.

The takeaway – be sure to check with your institution before you start writing.

How do I choose a topic for my research proposal?

Finding a good research topic is a process that involves multiple steps. We cover the topic ideation process in this video post.

How do I write a literature review for my proposal?

While you typically won’t need a comprehensive literature review at the proposal stage, you still need to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the key literature and are able to synthesise it. We explain the literature review process here.

How do I create a timeline and budget for my proposal?

We explain how to craft a project plan/timeline and budget in Research Proposal Bootcamp .

Which referencing format should I use in my research proposal?

The expectations and requirements regarding formatting and referencing vary from institution to institution. Therefore, you’ll need to check this information with your university.

What common proposal writing mistakes do I need to look out for?

We’ve create a video post about some of the most common mistakes students make when writing a proposal – you can access that here . If you’re short on time, here’s a quick summary:

- The research topic is too broad (or just poorly articulated).

- The research aims, objectives and questions don’t align.

- The research topic is not well justified.

- The study has a weak theoretical foundation.

- The research design is not well articulated well enough.

- Poor writing and sloppy presentation.

- Poor project planning and risk management.

- Not following the university’s specific criteria.

Key Takeaways & Additional Resources

As you write up your research proposal, remember the all-important core purpose: to convince . Your research proposal needs to sell your study in terms of suitability and viability. So, focus on crafting a convincing narrative to ensure a strong proposal.

At the same time, pay close attention to your university’s requirements. While we’ve covered the essentials here, every institution has its own set of expectations and it’s essential that you follow these to maximise your chances of approval.

By the way, we’ve got plenty more resources to help you fast-track your research proposal. Here are some of our most popular resources to get you started:

- Proposal Writing 101 : A Introductory Webinar

- Research Proposal Bootcamp : The Ultimate Online Course

- Template : A basic template to help you craft your proposal

If you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your research proposal, be sure to check out our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the proposal development process (and the entire research journey), step by step.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Research Proposal Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

51 Comments

I truly enjoyed this video, as it was eye-opening to what I have to do in the preparation of preparing a Research proposal.

I would be interested in getting some coaching.

I real appreciate on your elaboration on how to develop research proposal,the video explains each steps clearly.

Thank you for the video. It really assisted me and my niece. I am a PhD candidate and she is an undergraduate student. It is at times, very difficult to guide a family member but with this video, my job is done.

In view of the above, I welcome more coaching.

Wonderful guidelines, thanks

This is very helpful. Would love to continue even as I prepare for starting my masters next year.

Thanks for the work done, the text was helpful to me

Bundle of thanks to you for the research proposal guide it was really good and useful if it is possible please send me the sample of research proposal

You’re most welcome. We don’t have any research proposals that we can share (the students own the intellectual property), but you might find our research proposal template useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-proposal-template/

Cheruiyot Moses Kipyegon

Thanks alot. It was an eye opener that came timely enough before my imminent proposal defense. Thanks, again

thank you very much your lesson is very interested may God be with you

I am an undergraduate student (First Degree) preparing to write my project,this video and explanation had shed more light to me thanks for your efforts keep it up.

Very useful. I am grateful.

this is a very a good guidance on research proposal, for sure i have learnt something

Wonderful guidelines for writing a research proposal, I am a student of m.phil( education), this guideline is suitable for me. Thanks

You’re welcome 🙂

Thank you, this was so helpful.

A really great and insightful video. It opened my eyes as to how to write a research paper. I would like to receive more guidance for writing my research paper from your esteemed faculty.

Thank you, great insights

Thank you, great insights, thank you so much, feeling edified

Wow thank you, great insights, thanks a lot

Thank you. This is a great insight. I am a student preparing for a PhD program. I am requested to write my Research Proposal as part of what I am required to submit before my unconditional admission. I am grateful having listened to this video which will go a long way in helping me to actually choose a topic of interest and not just any topic as well as to narrow down the topic and be specific about it. I indeed need more of this especially as am trying to choose a topic suitable for a DBA am about embarking on. Thank you once more. The video is indeed helpful.

Have learnt a lot just at the right time. Thank you so much.

thank you very much ,because have learn a lot things concerning research proposal and be blessed u for your time that you providing to help us

Hi. For my MSc medical education research, please evaluate this topic for me: Training Needs Assessment of Faculty in Medical Training Institutions in Kericho and Bomet Counties

I have really learnt a lot based on research proposal and it’s formulation

Thank you. I learn much from the proposal since it is applied

Your effort is much appreciated – you have good articulation.

You have good articulation.

I do applaud your simplified method of explaining the subject matter, which indeed has broaden my understanding of the subject matter. Definitely this would enable me writing a sellable research proposal.

This really helping

Great! I liked your tutoring on how to find a research topic and how to write a research proposal. Precise and concise. Thank you very much. Will certainly share this with my students. Research made simple indeed.

Thank you very much. I an now assist my students effectively.

Thank you very much. I can now assist my students effectively.

I need any research proposal

Thank you for these videos. I will need chapter by chapter assistance in writing my MSc dissertation

Very helpfull

the videos are very good and straight forward

thanks so much for this wonderful presentations, i really enjoyed it to the fullest wish to learn more from you

Thank you very much. I learned a lot from your lecture.

I really enjoy the in-depth knowledge on research proposal you have given. me. You have indeed broaden my understanding and skills. Thank you

interesting session this has equipped me with knowledge as i head for exams in an hour’s time, am sure i get A++

This article was most informative and easy to understand. I now have a good idea of how to write my research proposal.

Thank you very much.

Wow, this literature is very resourceful and interesting to read. I enjoyed it and I intend reading it every now then.

Thank you for the clarity

Thank you. Very helpful.

Thank you very much for this essential piece. I need 1o1 coaching, unfortunately, your service is not available in my country. Anyways, a very important eye-opener. I really enjoyed it. A thumb up to Gradcoach

What is JAM? Please explain.

Thank you so much for these videos. They are extremely helpful! God bless!

very very wonderful…

thank you for the video but i need a written example

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Steps in Developing a Research Proposal

Learning objectives.

- Identify the steps in developing a research proposal.

- Choose a topic and formulate a research question and working thesis.

- Develop a research proposal.

Writing a good research paper takes time, thought, and effort. Although this assignment is challenging, it is manageable. Focusing on one step at a time will help you develop a thoughtful, informative, well-supported research paper.

Your first step is to choose a topic and then to develop research questions, a working thesis, and a written research proposal. Set aside adequate time for this part of the process. Fully exploring ideas will help you build a solid foundation for your paper.

Choosing a Topic

When you choose a topic for a research paper, you are making a major commitment. Your choice will help determine whether you enjoy the lengthy process of research and writing—and whether your final paper fulfills the assignment requirements. If you choose your topic hastily, you may later find it difficult to work with your topic. By taking your time and choosing carefully, you can ensure that this assignment is not only challenging but also rewarding.

Writers understand the importance of choosing a topic that fulfills the assignment requirements and fits the assignment’s purpose and audience. (For more information about purpose and audience, see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” .) Choosing a topic that interests you is also crucial. You instructor may provide a list of suggested topics or ask that you develop a topic on your own. In either case, try to identify topics that genuinely interest you.

After identifying potential topic ideas, you will need to evaluate your ideas and choose one topic to pursue. Will you be able to find enough information about the topic? Can you develop a paper about this topic that presents and supports your original ideas? Is the topic too broad or too narrow for the scope of the assignment? If so, can you modify it so it is more manageable? You will ask these questions during this preliminary phase of the research process.

Identifying Potential Topics

Sometimes, your instructor may provide a list of suggested topics. If so, you may benefit from identifying several possibilities before committing to one idea. It is important to know how to narrow down your ideas into a concise, manageable thesis. You may also use the list as a starting point to help you identify additional, related topics. Discussing your ideas with your instructor will help ensure that you choose a manageable topic that fits the requirements of the assignment.

In this chapter, you will follow a writer named Jorge, who is studying health care administration, as he prepares a research paper. You will also plan, research, and draft your own research paper.

Jorge was assigned to write a research paper on health and the media for an introductory course in health care. Although a general topic was selected for the students, Jorge had to decide which specific issues interested him. He brainstormed a list of possibilities.

If you are writing a research paper for a specialized course, look back through your notes and course activities. Identify reading assignments and class discussions that especially engaged you. Doing so can help you identify topics to pursue.

- Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) in the news

- Sexual education programs

- Hollywood and eating disorders

- Americans’ access to public health information

- Media portrayal of health care reform bill

- Depictions of drugs on television

- The effect of the Internet on mental health

- Popularized diets (such as low-carbohydrate diets)

- Fear of pandemics (bird flu, HINI, SARS)

- Electronic entertainment and obesity

- Advertisements for prescription drugs

- Public education and disease prevention

Set a timer for five minutes. Use brainstorming or idea mapping to create a list of topics you would be interested in researching for a paper about the influence of the Internet on social networking. Do you closely follow the media coverage of a particular website, such as Twitter? Would you like to learn more about a certain industry, such as online dating? Which social networking sites do you and your friends use? List as many ideas related to this topic as you can.

Narrowing Your Topic

Once you have a list of potential topics, you will need to choose one as the focus of your essay. You will also need to narrow your topic. Most writers find that the topics they listed during brainstorming or idea mapping are broad—too broad for the scope of the assignment. Working with an overly broad topic, such as sexual education programs or popularized diets, can be frustrating and overwhelming. Each topic has so many facets that it would be impossible to cover them all in a college research paper. However, more specific choices, such as the pros and cons of sexual education in kids’ television programs or the physical effects of the South Beach diet, are specific enough to write about without being too narrow to sustain an entire research paper.

A good research paper provides focused, in-depth information and analysis. If your topic is too broad, you will find it difficult to do more than skim the surface when you research it and write about it. Narrowing your focus is essential to making your topic manageable. To narrow your focus, explore your topic in writing, conduct preliminary research, and discuss both the topic and the research with others.

Exploring Your Topic in Writing

“How am I supposed to narrow my topic when I haven’t even begun researching yet?” In fact, you may already know more than you realize. Review your list and identify your top two or three topics. Set aside some time to explore each one through freewriting. (For more information about freewriting, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .) Simply taking the time to focus on your topic may yield fresh angles.

Jorge knew that he was especially interested in the topic of diet fads, but he also knew that it was much too broad for his assignment. He used freewriting to explore his thoughts so he could narrow his topic. Read Jorge’s ideas.

Conducting Preliminary Research

Another way writers may focus a topic is to conduct preliminary research . Like freewriting, exploratory reading can help you identify interesting angles. Surfing the web and browsing through newspaper and magazine articles are good ways to start. Find out what people are saying about your topic on blogs and online discussion groups. Discussing your topic with others can also inspire you. Talk about your ideas with your classmates, your friends, or your instructor.

Jorge’s freewriting exercise helped him realize that the assigned topic of health and the media intersected with a few of his interests—diet, nutrition, and obesity. Preliminary online research and discussions with his classmates strengthened his impression that many people are confused or misled by media coverage of these subjects.

Jorge decided to focus his paper on a topic that had garnered a great deal of media attention—low-carbohydrate diets. He wanted to find out whether low-carbohydrate diets were as effective as their proponents claimed.

Writing at Work

At work, you may need to research a topic quickly to find general information. This information can be useful in understanding trends in a given industry or generating competition. For example, a company may research a competitor’s prices and use the information when pricing their own product. You may find it useful to skim a variety of reliable sources and take notes on your findings.

The reliability of online sources varies greatly. In this exploratory phase of your research, you do not need to evaluate sources as closely as you will later. However, use common sense as you refine your paper topic. If you read a fascinating blog comment that gives you a new idea for your paper, be sure to check out other, more reliable sources as well to make sure the idea is worth pursuing.

Review the list of topics you created in Note 11.18 “Exercise 1” and identify two or three topics you would like to explore further. For each of these topics, spend five to ten minutes writing about the topic without stopping. Then review your writing to identify possible areas of focus.

Set aside time to conduct preliminary research about your potential topics. Then choose a topic to pursue for your research paper.

Collaboration

Please share your topic list with a classmate. Select one or two topics on his or her list that you would like to learn more about and return it to him or her. Discuss why you found the topics interesting, and learn which of your topics your classmate selected and why.

A Plan for Research

Your freewriting and preliminary research have helped you choose a focused, manageable topic for your research paper. To work with your topic successfully, you will need to determine what exactly you want to learn about it—and later, what you want to say about it. Before you begin conducting in-depth research, you will further define your focus by developing a research question , a working thesis, and a research proposal.

Formulating a Research Question

In forming a research question, you are setting a goal for your research. Your main research question should be substantial enough to form the guiding principle of your paper—but focused enough to guide your research. A strong research question requires you not only to find information but also to put together different pieces of information, interpret and analyze them, and figure out what you think. As you consider potential research questions, ask yourself whether they would be too hard or too easy to answer.

To determine your research question, review the freewriting you completed earlier. Skim through books, articles, and websites and list the questions you have. (You may wish to use the 5WH strategy to help you formulate questions. See Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” for more information about 5WH questions.) Include simple, factual questions and more complex questions that would require analysis and interpretation. Determine your main question—the primary focus of your paper—and several subquestions that you will need to research to answer your main question.

Here are the research questions Jorge will use to focus his research. Notice that his main research question has no obvious, straightforward answer. Jorge will need to research his subquestions, which address narrower topics, to answer his main question.

Using the topic you selected in Note 11.24 “Exercise 2” , write your main research question and at least four to five subquestions. Check that your main research question is appropriately complex for your assignment.

Constructing a Working ThesIs

A working thesis concisely states a writer’s initial answer to the main research question. It does not merely state a fact or present a subjective opinion. Instead, it expresses a debatable idea or claim that you hope to prove through additional research. Your working thesis is called a working thesis for a reason—it is subject to change. As you learn more about your topic, you may change your thinking in light of your research findings. Let your working thesis serve as a guide to your research, but do not be afraid to modify it based on what you learn.

Jorge began his research with a strong point of view based on his preliminary writing and research. Read his working thesis statement, which presents the point he will argue. Notice how it states Jorge’s tentative answer to his research question.

One way to determine your working thesis is to consider how you would complete sentences such as I believe or My opinion is . However, keep in mind that academic writing generally does not use first-person pronouns. These statements are useful starting points, but formal research papers use an objective voice.

Write a working thesis statement that presents your preliminary answer to the research question you wrote in Note 11.27 “Exercise 3” . Check that your working thesis statement presents an idea or claim that could be supported or refuted by evidence from research.

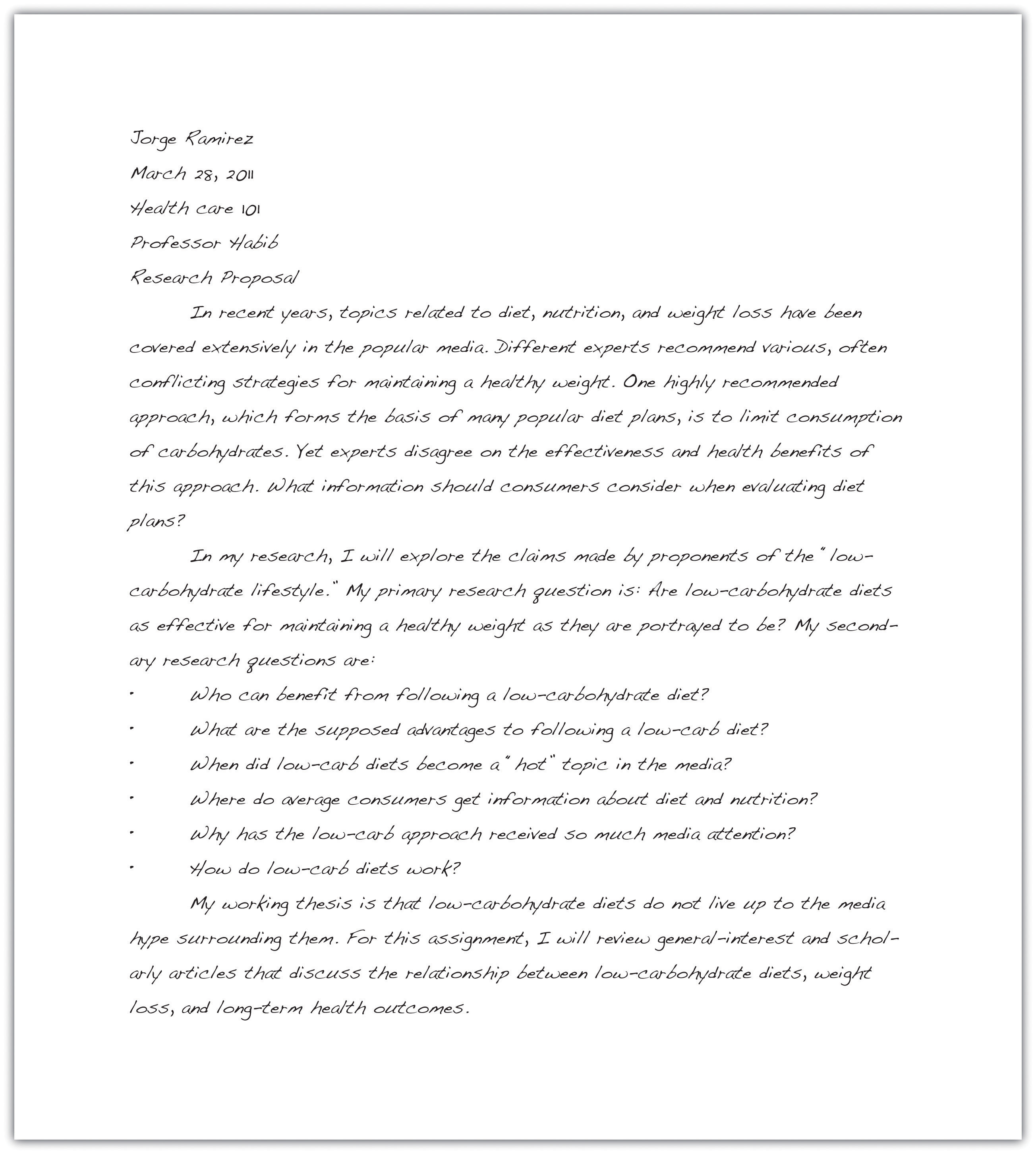

Creating a Research Proposal

A research proposal is a brief document—no more than one typed page—that summarizes the preliminary work you have completed. Your purpose in writing it is to formalize your plan for research and present it to your instructor for feedback. In your research proposal, you will present your main research question, related subquestions, and working thesis. You will also briefly discuss the value of researching this topic and indicate how you plan to gather information.

When Jorge began drafting his research proposal, he realized that he had already created most of the pieces he needed. However, he knew he also had to explain how his research would be relevant to other future health care professionals. In addition, he wanted to form a general plan for doing the research and identifying potentially useful sources. Read Jorge’s research proposal.

Before you begin a new project at work, you may have to develop a project summary document that states the purpose of the project, explains why it would be a wise use of company resources, and briefly outlines the steps involved in completing the project. This type of document is similar to a research proposal. Both documents define and limit a project, explain its value, discuss how to proceed, and identify what resources you will use.

Writing Your Own Research Proposal

Now you may write your own research proposal, if you have not done so already. Follow the guidelines provided in this lesson.

Key Takeaways

- Developing a research proposal involves the following preliminary steps: identifying potential ideas, choosing ideas to explore further, choosing and narrowing a topic, formulating a research question, and developing a working thesis.

- A good topic for a research paper interests the writer and fulfills the requirements of the assignment.

- Defining and narrowing a topic helps writers conduct focused, in-depth research.

- Writers conduct preliminary research to identify possible topics and research questions and to develop a working thesis.

- A good research question interests readers, is neither too broad nor too narrow, and has no obvious answer.

- A good working thesis expresses a debatable idea or claim that can be supported with evidence from research.

- Writers create a research proposal to present their topic, main research question, subquestions, and working thesis to an instructor for approval or feedback.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

17 Research Proposal Examples

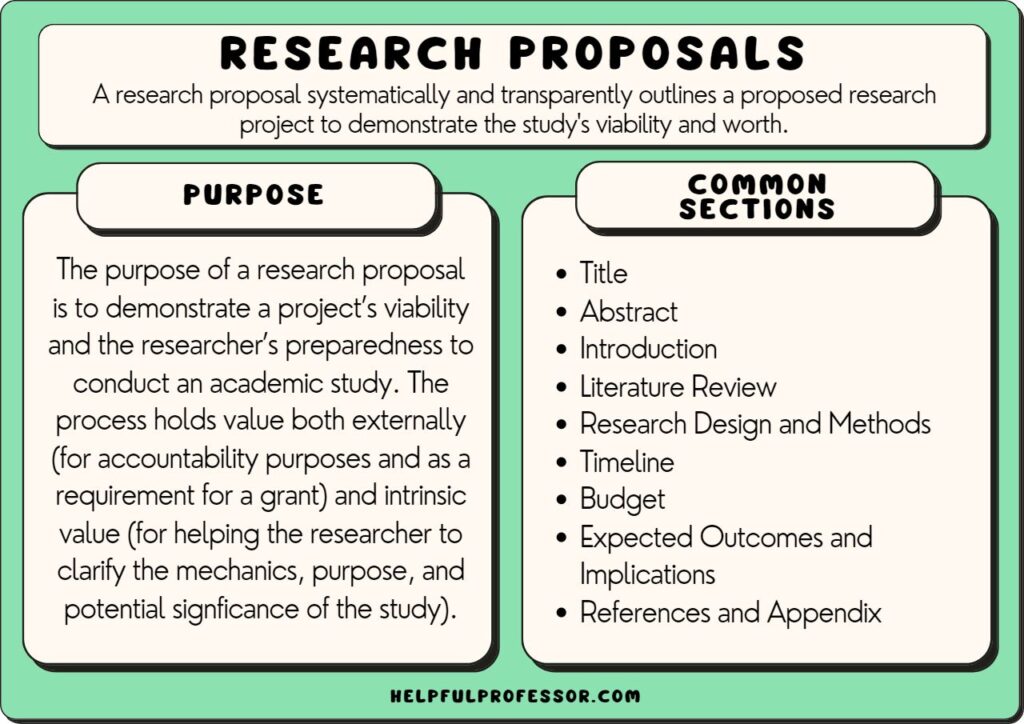

A research proposal systematically and transparently outlines a proposed research project.

The purpose of a research proposal is to demonstrate a project’s viability and the researcher’s preparedness to conduct an academic study. It serves as a roadmap for the researcher.

The process holds value both externally (for accountability purposes and often as a requirement for a grant application) and intrinsic value (for helping the researcher to clarify the mechanics, purpose, and potential signficance of the study).

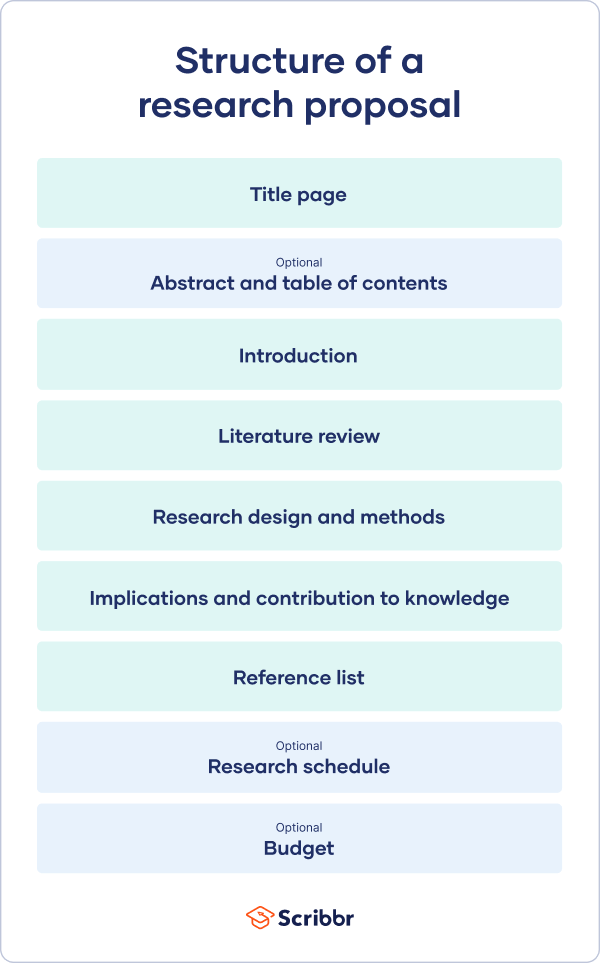

Key sections of a research proposal include: the title, abstract, introduction, literature review, research design and methods, timeline, budget, outcomes and implications, references, and appendix. Each is briefly explained below.

Watch my Guide: How to Write a Research Proposal

Get your Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

Research Proposal Sample Structure

Title: The title should present a concise and descriptive statement that clearly conveys the core idea of the research projects. Make it as specific as possible. The reader should immediately be able to grasp the core idea of the intended research project. Often, the title is left too vague and does not help give an understanding of what exactly the study looks at.

Abstract: Abstracts are usually around 250-300 words and provide an overview of what is to follow – including the research problem , objectives, methods, expected outcomes, and significance of the study. Use it as a roadmap and ensure that, if the abstract is the only thing someone reads, they’ll get a good fly-by of what will be discussed in the peice.

Introduction: Introductions are all about contextualization. They often set the background information with a statement of the problem. At the end of the introduction, the reader should understand what the rationale for the study truly is. I like to see the research questions or hypotheses included in the introduction and I like to get a good understanding of what the significance of the research will be. It’s often easiest to write the introduction last

Literature Review: The literature review dives deep into the existing literature on the topic, demosntrating your thorough understanding of the existing literature including themes, strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in the literature. It serves both to demonstrate your knowledge of the field and, to demonstrate how the proposed study will fit alongside the literature on the topic. A good literature review concludes by clearly demonstrating how your research will contribute something new and innovative to the conversation in the literature.

Research Design and Methods: This section needs to clearly demonstrate how the data will be gathered and analyzed in a systematic and academically sound manner. Here, you need to demonstrate that the conclusions of your research will be both valid and reliable. Common points discussed in the research design and methods section include highlighting the research paradigm, methodologies, intended population or sample to be studied, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures . Toward the end of this section, you are encouraged to also address ethical considerations and limitations of the research process , but also to explain why you chose your research design and how you are mitigating the identified risks and limitations.

Timeline: Provide an outline of the anticipated timeline for the study. Break it down into its various stages (including data collection, data analysis, and report writing). The goal of this section is firstly to establish a reasonable breakdown of steps for you to follow and secondly to demonstrate to the assessors that your project is practicable and feasible.

Budget: Estimate the costs associated with the research project and include evidence for your estimations. Typical costs include staffing costs, equipment, travel, and data collection tools. When applying for a scholarship, the budget should demonstrate that you are being responsible with your expensive and that your funding application is reasonable.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: A discussion of the anticipated findings or results of the research, as well as the potential contributions to the existing knowledge, theory, or practice in the field. This section should also address the potential impact of the research on relevant stakeholders and any broader implications for policy or practice.

References: A complete list of all the sources cited in the research proposal, formatted according to the required citation style. This demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the relevant literature and ensures proper attribution of ideas and information.

Appendices (if applicable): Any additional materials, such as questionnaires, interview guides, or consent forms, that provide further information or support for the research proposal. These materials should be included as appendices at the end of the document.

Research Proposal Examples

Research proposals often extend anywhere between 2,000 and 15,000 words in length. The following snippets are samples designed to briefly demonstrate what might be discussed in each section.

1. Education Studies Research Proposals

See some real sample pieces:

- Assessment of the perceptions of teachers towards a new grading system

- Does ICT use in secondary classrooms help or hinder student learning?

- Digital technologies in focus project

- Urban Middle School Teachers’ Experiences of the Implementation of

- Restorative Justice Practices

- Experiences of students of color in service learning

Consider this hypothetical education research proposal:

The Impact of Game-Based Learning on Student Engagement and Academic Performance in Middle School Mathematics

Abstract: The proposed study will explore multiplayer game-based learning techniques in middle school mathematics curricula and their effects on student engagement. The study aims to contribute to the current literature on game-based learning by examining the effects of multiplayer gaming in learning.

Introduction: Digital game-based learning has long been shunned within mathematics education for fears that it may distract students or lower the academic integrity of the classrooms. However, there is emerging evidence that digital games in math have emerging benefits not only for engagement but also academic skill development. Contributing to this discourse, this study seeks to explore the potential benefits of multiplayer digital game-based learning by examining its impact on middle school students’ engagement and academic performance in a mathematics class.

Literature Review: The literature review has identified gaps in the current knowledge, namely, while game-based learning has been extensively explored, the role of multiplayer games in supporting learning has not been studied.

Research Design and Methods: This study will employ a mixed-methods research design based upon action research in the classroom. A quasi-experimental pre-test/post-test control group design will first be used to compare the academic performance and engagement of middle school students exposed to game-based learning techniques with those in a control group receiving instruction without the aid of technology. Students will also be observed and interviewed in regard to the effect of communication and collaboration during gameplay on their learning.

Timeline: The study will take place across the second term of the school year with a pre-test taking place on the first day of the term and the post-test taking place on Wednesday in Week 10.

Budget: The key budgetary requirements will be the technologies required, including the subscription cost for the identified games and computers.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: It is expected that the findings will contribute to the current literature on game-based learning and inform educational practices, providing educators and policymakers with insights into how to better support student achievement in mathematics.

2. Psychology Research Proposals

See some real examples:

- A situational analysis of shared leadership in a self-managing team

- The effect of musical preference on running performance

- Relationship between self-esteem and disordered eating amongst adolescent females

Consider this hypothetical psychology research proposal:

The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Interventions on Stress Reduction in College Students

Abstract: This research proposal examines the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on stress reduction among college students, using a pre-test/post-test experimental design with both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods .

Introduction: College students face heightened stress levels during exam weeks. This can affect both mental health and test performance. This study explores the potential benefits of mindfulness-based interventions such as meditation as a way to mediate stress levels in the weeks leading up to exam time.

Literature Review: Existing research on mindfulness-based meditation has shown the ability for mindfulness to increase metacognition, decrease anxiety levels, and decrease stress. Existing literature has looked at workplace, high school and general college-level applications. This study will contribute to the corpus of literature by exploring the effects of mindfulness directly in the context of exam weeks.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n= 234 ) will be randomly assigned to either an experimental group, receiving 5 days per week of 10-minute mindfulness-based interventions, or a control group, receiving no intervention. Data will be collected through self-report questionnaires, measuring stress levels, semi-structured interviews exploring participants’ experiences, and students’ test scores.

Timeline: The study will begin three weeks before the students’ exam week and conclude after each student’s final exam. Data collection will occur at the beginning (pre-test of self-reported stress levels) and end (post-test) of the three weeks.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: The study aims to provide evidence supporting the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in reducing stress among college students in the lead up to exams, with potential implications for mental health support and stress management programs on college campuses.

3. Sociology Research Proposals

- Understanding emerging social movements: A case study of ‘Jersey in Transition’

- The interaction of health, education and employment in Western China

- Can we preserve lower-income affordable neighbourhoods in the face of rising costs?

Consider this hypothetical sociology research proposal:

The Impact of Social Media Usage on Interpersonal Relationships among Young Adults

Abstract: This research proposal investigates the effects of social media usage on interpersonal relationships among young adults, using a longitudinal mixed-methods approach with ongoing semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative data.

Introduction: Social media platforms have become a key medium for the development of interpersonal relationships, particularly for young adults. This study examines the potential positive and negative effects of social media usage on young adults’ relationships and development over time.

Literature Review: A preliminary review of relevant literature has demonstrated that social media usage is central to development of a personal identity and relationships with others with similar subcultural interests. However, it has also been accompanied by data on mental health deline and deteriorating off-screen relationships. The literature is to-date lacking important longitudinal data on these topics.

Research Design and Methods: Participants ( n = 454 ) will be young adults aged 18-24. Ongoing self-report surveys will assess participants’ social media usage, relationship satisfaction, and communication patterns. A subset of participants will be selected for longitudinal in-depth interviews starting at age 18 and continuing for 5 years.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of five years, including recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide insights into the complex relationship between social media usage and interpersonal relationships among young adults, potentially informing social policies and mental health support related to social media use.

4. Nursing Research Proposals

- Does Orthopaedic Pre-assessment clinic prepare the patient for admission to hospital?

- Nurses’ perceptions and experiences of providing psychological care to burns patients

- Registered psychiatric nurse’s practice with mentally ill parents and their children

Consider this hypothetical nursing research proposal:

The Influence of Nurse-Patient Communication on Patient Satisfaction and Health Outcomes following Emergency Cesarians

Abstract: This research will examines the impact of effective nurse-patient communication on patient satisfaction and health outcomes for women following c-sections, utilizing a mixed-methods approach with patient surveys and semi-structured interviews.

Introduction: It has long been known that effective communication between nurses and patients is crucial for quality care. However, additional complications arise following emergency c-sections due to the interaction between new mother’s changing roles and recovery from surgery.

Literature Review: A review of the literature demonstrates the importance of nurse-patient communication, its impact on patient satisfaction, and potential links to health outcomes. However, communication between nurses and new mothers is less examined, and the specific experiences of those who have given birth via emergency c-section are to date unexamined.

Research Design and Methods: Participants will be patients in a hospital setting who have recently had an emergency c-section. A self-report survey will assess their satisfaction with nurse-patient communication and perceived health outcomes. A subset of participants will be selected for in-depth interviews to explore their experiences and perceptions of the communication with their nurses.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of six months, including rolling recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing within the hospital.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide evidence for the significance of nurse-patient communication in supporting new mothers who have had an emergency c-section. Recommendations will be presented for supporting nurses and midwives in improving outcomes for new mothers who had complications during birth.

5. Social Work Research Proposals

- Experiences of negotiating employment and caring responsibilities of fathers post-divorce

- Exploring kinship care in the north region of British Columbia

Consider this hypothetical social work research proposal:

The Role of a Family-Centered Intervention in Preventing Homelessness Among At-Risk Youthin a working-class town in Northern England

Abstract: This research proposal investigates the effectiveness of a family-centered intervention provided by a local council area in preventing homelessness among at-risk youth. This case study will use a mixed-methods approach with program evaluation data and semi-structured interviews to collect quantitative and qualitative data .

Introduction: Homelessness among youth remains a significant social issue. This study aims to assess the effectiveness of family-centered interventions in addressing this problem and identify factors that contribute to successful prevention strategies.

Literature Review: A review of the literature has demonstrated several key factors contributing to youth homelessness including lack of parental support, lack of social support, and low levels of family involvement. It also demonstrates the important role of family-centered interventions in addressing this issue. Drawing on current evidence, this study explores the effectiveness of one such intervention in preventing homelessness among at-risk youth in a working-class town in Northern England.

Research Design and Methods: The study will evaluate a new family-centered intervention program targeting at-risk youth and their families. Quantitative data on program outcomes, including housing stability and family functioning, will be collected through program records and evaluation reports. Semi-structured interviews with program staff, participants, and relevant stakeholders will provide qualitative insights into the factors contributing to program success or failure.

Timeline: The study will be conducted over a period of six months, including recruitment, data collection, analysis, and report writing.

Budget: Expenses include access to program evaluation data, interview materials, data analysis software, and any related travel costs for in-person interviews.

Expected Outcomes and Implications: This study aims to provide evidence for the effectiveness of family-centered interventions in preventing youth homelessness, potentially informing the expansion of or necessary changes to social work practices in Northern England.

Research Proposal Template

Get your Detailed Template for Writing your Research Proposal Here (With AI Prompts!)

This is a template for a 2500-word research proposal. You may find it difficult to squeeze everything into this wordcount, but it’s a common wordcount for Honors and MA-level dissertations.

Your research proposal is where you really get going with your study. I’d strongly recommend working closely with your teacher in developing a research proposal that’s consistent with the requirements and culture of your institution, as in my experience it varies considerably. The above template is from my own courses that walk students through research proposals in a British School of Education.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

8 thoughts on “17 Research Proposal Examples”

Very excellent research proposals

very helpful

Very helpful

Dear Sir, I need some help to write an educational research proposal. Thank you.

Hi Levi, use the site search bar to ask a question and I’ll likely have a guide already written for your specific question. Thanks for reading!

very good research proposal

Thank you so much sir! ❤️

Very helpful 👌

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on 30 October 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on 13 June 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organised and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, frequently asked questions.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: ‘A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management’

- Example research proposal #2: ‘ Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use’

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesise prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasise again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement.

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, June 13). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved 22 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/the-research-process/research-proposal-explained/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, what is a literature review | guide, template, & examples, how to write a results section | tips & examples.

Researched by Consultants from Top-Tier Management Companies

Powerpoint Templates

Icon Bundle

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

Top 7 One-Page Research Proposal Templates with Examples and Samples

Neha Parmar

In the world of research and academics, writing proposals is important. Whether you’re an experienced researcher, a student, or someone looking for money for a project, explaining your research clearly is beneficial. A great research proposal can be challenging even when things are going well. Can you fit all your ideas on just one page?

The answer is yes, and it's because of efficiency. In a fast-moving world with lots of information, being brief is good. This short proposal format helps you explain your research goals, methods, and what you expect to find. It gets to the heart of your project, so you can explain it to people who might support you, like advisors or funders.

At this stage, you will do well to explore our curated collection of the top 10 security system proposal templates with samples and examples. Click here.

This way of doing proposals isn't just about being short; it's about making a significant impact. A well-structured one-page proposal is like a quick summary that catches people's attention and helps them understand why your research is important, all in a few seconds. In a world where time is valuable, the One-Page Research Proposal is the best way to ensure people notice and think about your research ideas. Hence, don't miss the chance to improve your proposals with our well-crafted content-ready templates, which are 100 % editable and customizable.

Let's explore!

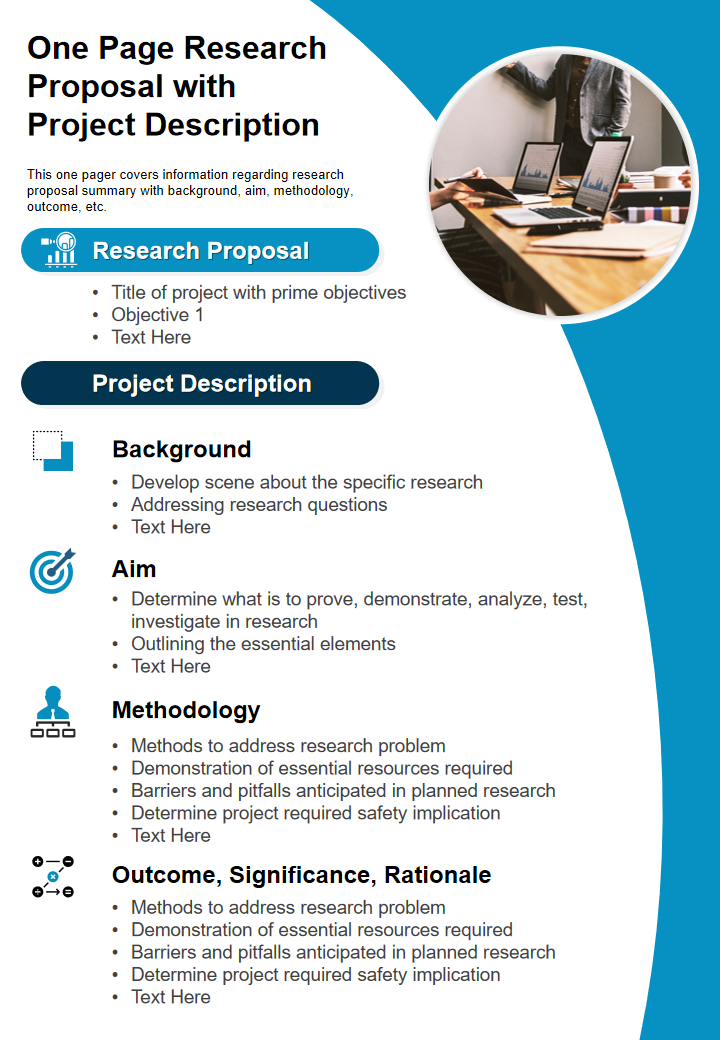

Template1 One-Page Research Proposal with Project Description Presentation Report Infographic

Are you searching for an effective way to present a synchronized summary of your project? Look no further and use this PowerPoint Template. This comprehensive template encompasses necessary information about your research proposal, including project background, objectives, methodology, outcomes, significance, rationale, and more. With the use of this template, you can easily introduce your research proposal's title and objectives while providing a clear project description that outlines the specific area of study. This slide will assist you in creating a detailed project plan, including the methods and techniques to be employed. It also addresses data collection and sampling techniques when preparing the project proposal. Download this pre-prepared content template now to simplify your project presentation.

Download Now

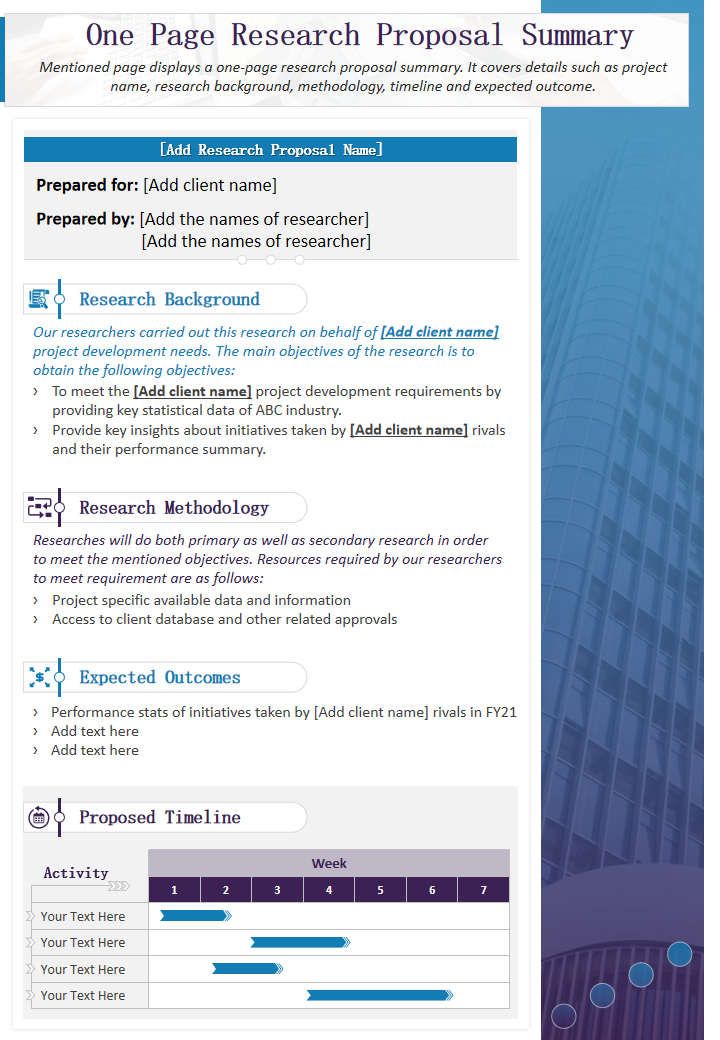

Template 2:- One-Page Research Proposal Summary Presentation Report PPT PDF

Creating a research proposal can be challenging, so we've developed a content-ready template to assist you. This template serves a dual purpose: It aids in presenting and justifying your study, and second, it helps you devise practical strategies for conducting the proposed research. It encompasses critical elements such as project name, research background, methodology, expected outcomes, and a proposed timeline. Whether aligning your research questions, addressing potential challenges, or incorporating essential components, this readily available PPT template empowers you to craft an impeccable presentation. Don't miss out on this opportunity – acquire this PowerPoint Template now!

Download Now!

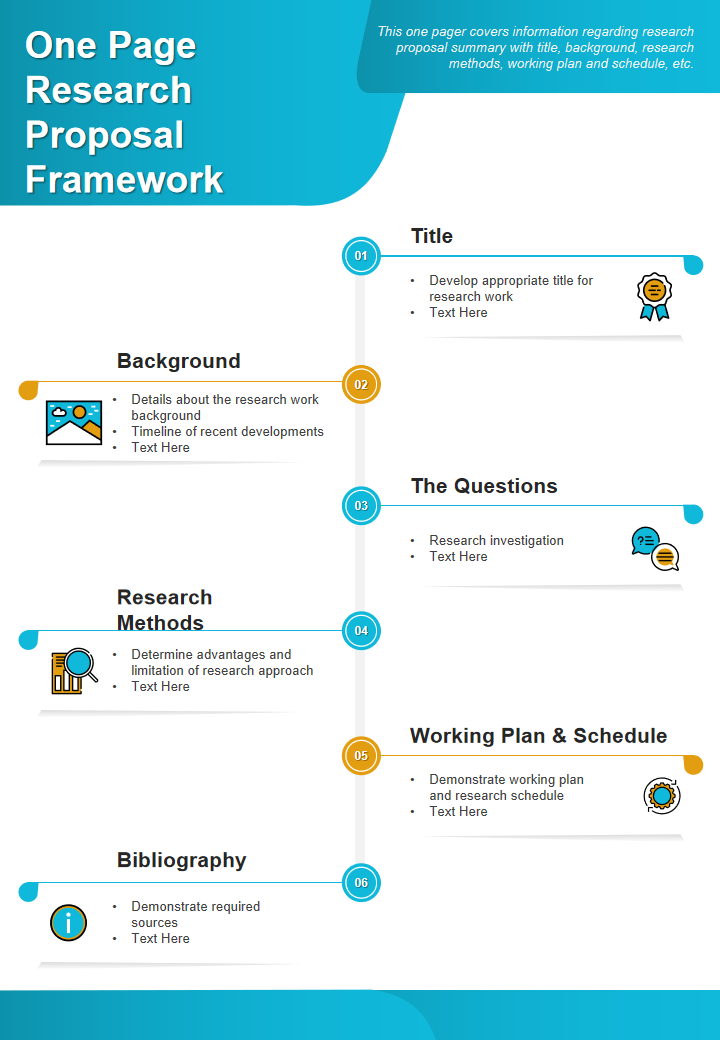

Template 3 One-Page Research Proposal Framework Presentation Doc

This comprehensive template includes sections for a research proposal summary, encompassing the title, background, research questions, methods, work plan, schedule, and bibliography. Within this template, you can specify a suitable research title and provide a comprehensive background of the research work. You also outline recent developments in a timeline, describe your research methodology and assess the strengths and limitations of your approach. Finally, you present your work plan and schedule, and list the necessary sources and references.

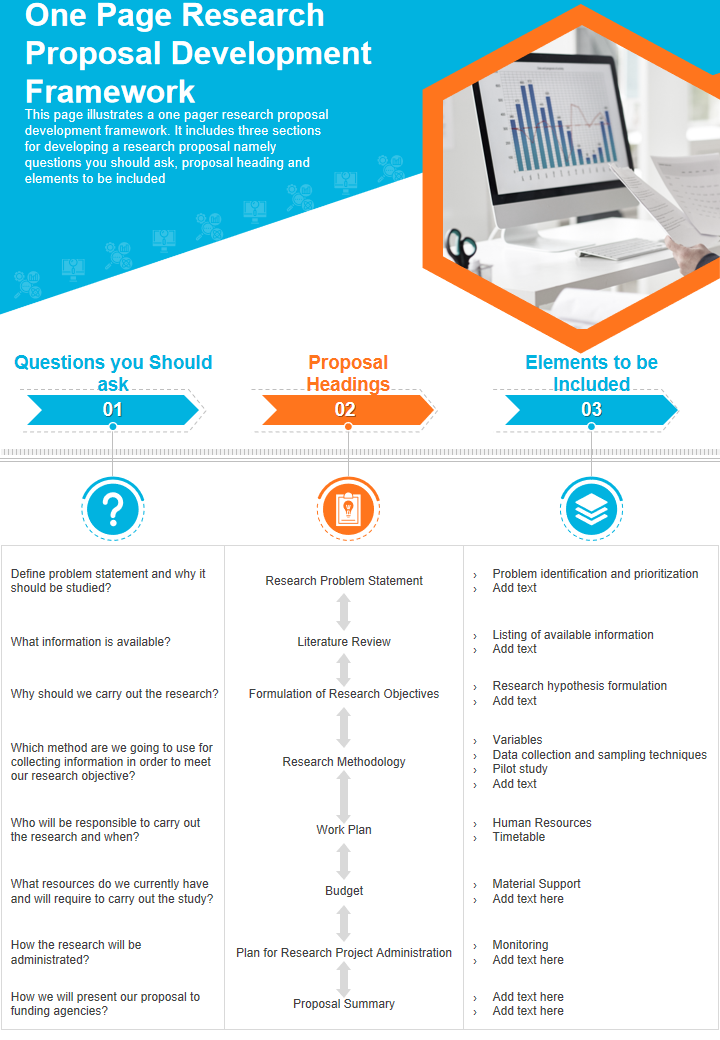

Template 4:- One-Page Research Proposal Development Framework Presentation Infographic

With this PPT Template, you can access a valuable resource for creating a top-notch research proposal. This essential document provides a streamlined approach to crafting a compelling research proposal. Inside, you'll find three critical sections for effective proposal development: A set of vital questions you should address, a dynamic proposal heading, and the essential elements for a successful proposal. Simplify your research process and bolster your presentations with this indispensable framework.

Download now

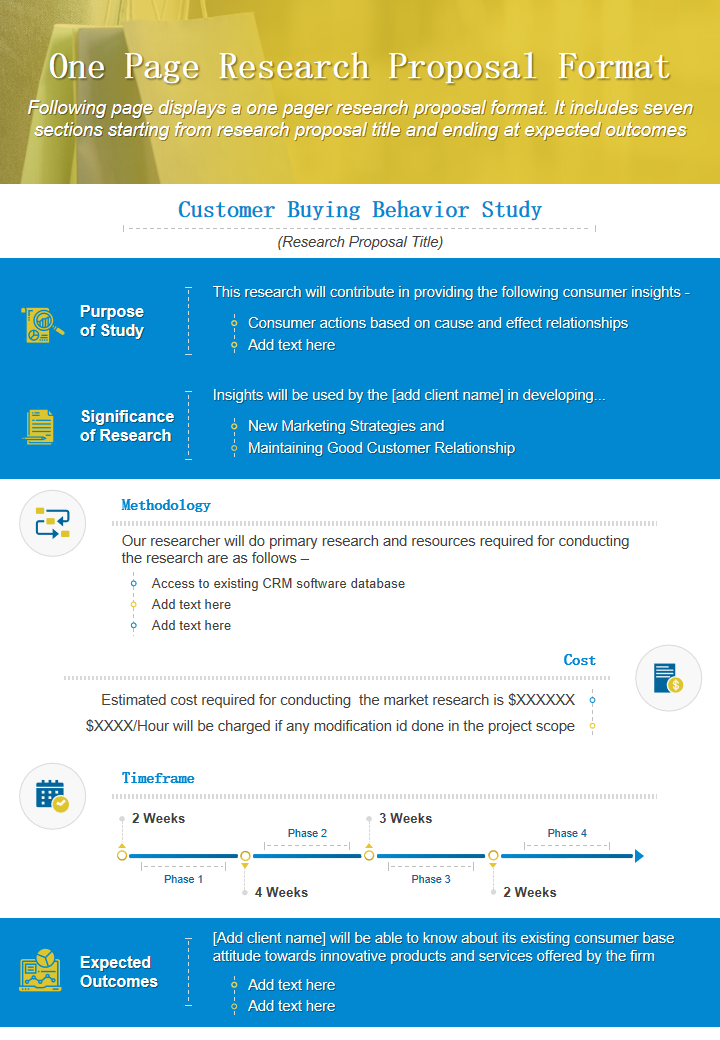

Template 5: One-Page Research Proposal Format Presentation Report PPT Template

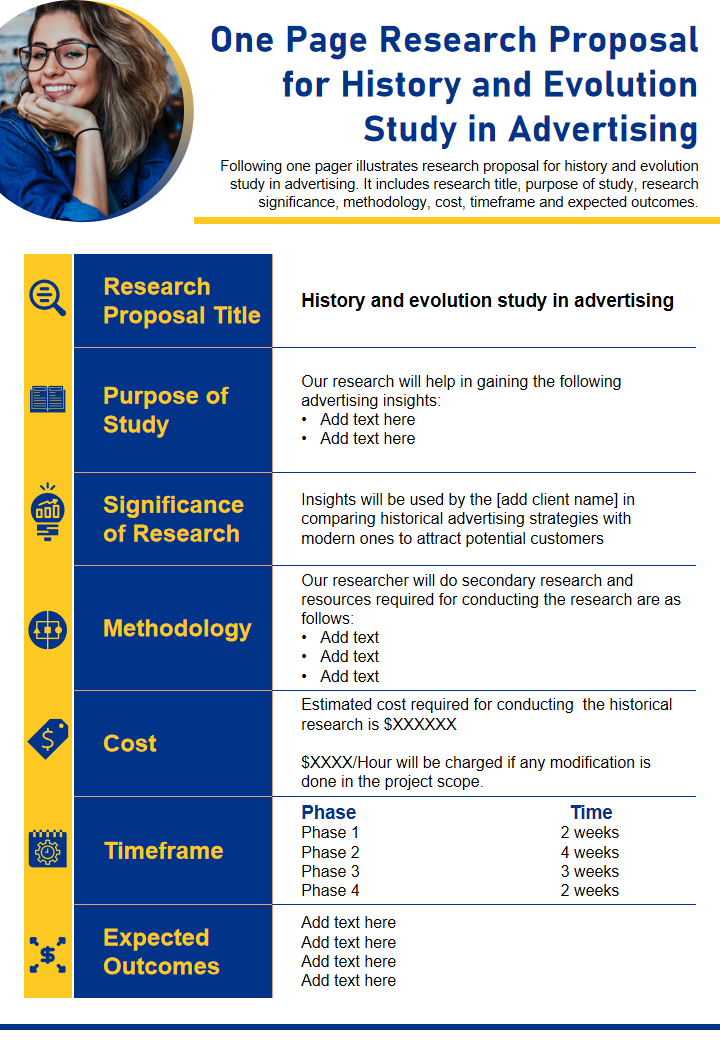

Introducing a convenient and versatile template that assists you in producing a compelling research proposal without the need for extensive, time-consuming effort. It comprises seven sections that guide you through the proposal process, from defining your research proposal title to outlining the expected outcomes. Beginning with the significance and purpose of the study, it seamlessly transitions into methodology, costs, and timeframe and culminates in the anticipated research outcomes. This comprehensive framework ensures your research proposal is well-structured and presentation-ready, allowing you to focus on the content and research.

Template 6 One-Page Research Proposal for History And Evolution Study in Advertising Report

Suppose you're seeking research that provides a richer understanding of how history has influenced advertising and can offer insights for future advertising strategies. In that case, you've come to the right place. Our template encompasses the research title, the study's purpose for gaining advertising insights and the significance of comparing historical and modern advertising strategies to engage potential customers. We also showcase how to conduct an overview of the research methodology and required resources, estimated research costs, a timeline divided into phases, and expected outcomes. Don't miss the opportunity to access this template; download it now to enhance your advertising strategies.

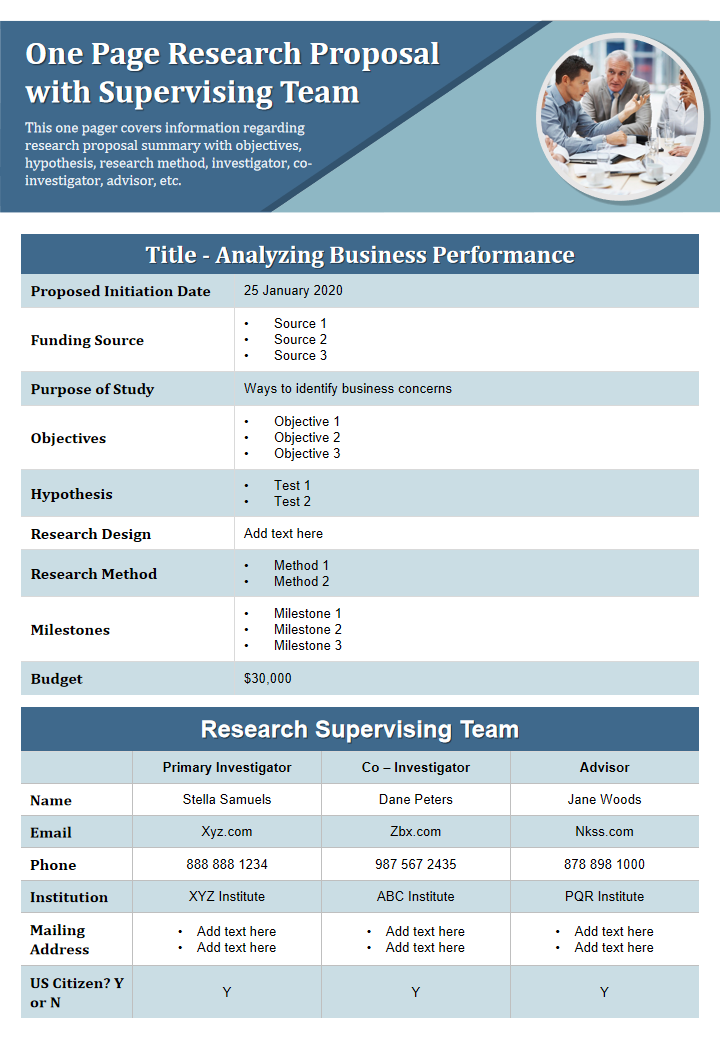

Template 7 One-Page Research Proposal with Supervising team Presentation Report Doc

This comprehensive template has two essential sections. The first part covers vital information such as the proposed initiation date, funding source, study purpose, objectives, hypothesis, research design, methodology, milestones, and budget. The second part focuses on the research supervising team, where you can input the primary investigator, co-investigator, and advisor details, including their names, emails, phone numbers, institutions, mailing addresses, and U.S. citizenship status. Elevate your research proposal to new heights with this ready-to-use template. Download it now to get started.

MAPPING THE PATH TO SUCCESS

When navigating the complexities of your research activities, a research proposal acts as a helpful guide by offering the required direction and structure. It gives you a strong sense of order and assurance in the direction you've chosen to go in. These templates represent a unique opportunity to showcase your expertise in the subject matter, revealing how you plan to impact your chosen field of study.

Using our research proposal presentation templates enables you to effectively convey your research plan by delivering your knowledge with clarity, consistency, and conciseness. Additionally, it forces you to highlight the value of your study and illustrate the prospective results of your research, displaying a thorough awareness of its significance.

In this way, a one-page research proposal not only acts as a blueprint for your project but also as a powerful tool to secure support, funding, and collaboration.

Discover our must-have rebranding proposal templates with samples and examples to give your brand a fresh start and a competitive edge. Click here

PS Dive into the world of research excellence with our handpicked selection of the top 10 research presentation templates, each accompanied by real-life examples and samples. Click here

Related posts:

- Must-Have Research Proposal Summary Example with Templates and Samples

- Top 10 Experimental Proposal Templates with Examples and Samples

- Top 10 Research Paper Proposal Templates with Samples and Examples

- Research Project Proposal Templates That Ace Your Funding Quest!

Liked this blog? Please recommend us

Top 7 Product Owner Templates with Samples and Examples

Top 7 Staff Training Plan Templates with Samples and Examples

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Digital revolution powerpoint presentation slides

Sales funnel results presentation layouts

3d men joinning circular jigsaw puzzles ppt graphics icons

Business Strategic Planning Template For Organizations Powerpoint Presentation Slides

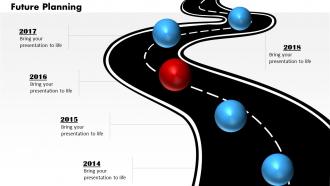

Future plan powerpoint template slide

Project Management Team Powerpoint Presentation Slides

Brand marketing powerpoint presentation slides

Launching a new service powerpoint presentation with slides go to market

Agenda powerpoint slide show