How to Format a College Essay: Step-by-Step Guide

Mark Twain once said, “I like a good story well told. That’s the reason I am sometimes forced to tell them myself.”

At College Essay Guy, we too like good stories well told.

The problem is that sometimes students have really good stories … that just aren’t well told.

They have the seed of an idea and the makings of a great story, but the essay formatting or structure is all over the place.

Which can lead a college admissions reader to see you as disorganized. And your essay doesn’t make as much of an impact as it could.

So, if you’re here, you’re probably wondering:

Is there any kind of required format for a college essay? How do I structure my essay?

And maybe what’s the difference?

Good news: That’s what this post answers.

First, let’s go over a few basic questions students often have when trying to figure out how to format their essay.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- College essay format guidelines

- How to brainstorm and structure a college essay topic

- Recommended brainstorming examples

- Example college essay: The “Burying Grandma” essay

College Essay Format Guidelines

Should I title my college essay?

You don’t need one. In the vast majority of cases, students we work with don’t use titles. The handful of times they have, they’ve done so because the title allows for a subtle play on words or reframing of the essay as a whole. So don’t feel any pressure to include one—they’re purely optional.

Should I indent or us paragraph breaks in my college essay?

Either. Just be consistent. The exception here is if you’re pasting into a box that screws up your formatting—for example, if, when you copy your essay into the box, your indentations are removed, go with paragraph breaks. (And when you get to college, be sure to check what style guide you should be following: Chicago, APA, MLA, etc., can all take different approaches to formatting, and different fields have different standards.)

How many paragraphs should a college essay be?

Personal statements are not English essays. They don’t need to be 5 paragraphs with a clear, argumentative thesis in the beginning and a conclusion that sums everything up. So feel free to break from that. How many paragraphs are appropriate for a college essay? Within reason, it’s up to you. We’ve seen some great personal statements that use 4 paragraphs, and some that use 8 or more (especially if you have dialogue—yes, dialogue is OK too!).

How long should my college essay be?

The good news is that colleges and the application systems they use will usually give you specific word count maximums. The most popular college application systems, like the Common Application and Coalition Application, will give you a maximum of 650 words for your main personal statement, and typically less than that for school-specific supplemental essays . Other systems will usually specify the maximum word count—the UC PIQs are 350 max, for example. If they don’t specify this clearly in the application systems or on their website (and be sure to do some research), you can email them to ask! They don’t bite.

So should you use all that space? We generally recommend it. You likely have lots to share about your life, so we think that not using all the space they offer to tell your story might be a missed opportunity. While you don’t have to use every last word, aim to use most of the words they give you. But don’t just fill the space if what you’re sharing doesn’t add to the overall story you’re telling.

There are also some applications or supplementals with recommended word counts or lengths. For example, Georgetown says things like “approx. 1 page,” and UChicago doesn’t have a limit, but recommends aiming for 650ish for the extended essay, and 250-500 for the “Why us?”

You can generally apply UChicago’s recommendations to other schools that don’t give you a limit: If it’s a “Why Major” supplement, 650 is probably plenty, and for other supplements, 250-500 is a good target to shoot for. If you go over those, that can be fine, just be sure you’re earning that word count (as in, not rambling or being overly verbose). Your readers are humans. If you send them a tome, their attention could drift.

Regarding things like italics and bold

Keep in mind that if you’re pasting text into a box, it may wipe out your formatting. So if you were hoping to rely on italics or bold for some kind of emphasis, double check if you’ll be able to. (And in general, try to use sentence structure and phrasing to create that kind of emphasis anyway, rather than relying on bold or italics—doing so will make you a better writer.)

Regarding font type, size, and color

Keep it simple and standard. Regarding font type, things like Times New Roman or Georgia (what this is written in) won’t fail you. Just avoid things like Comic Sans or other informal/casual fonts.

Size? 11- or 12-point is fine.

Color? Black.

Going with something else with the above could be a risk, possibly a big one, for fairly little gain. Things like a wacky font or text color could easily feel gimmicky to a reader.

To stand out with your writing, take some risks in what you write about and the connections and insights you make.

If you’re attaching a doc (rather than pasting)

If you are attaching a document rather than pasting into a text box, all the above still applies. Again, we’d recommend sticking with standard fonts and sizes—Times New Roman, 12-point is a standard workhorse. You can probably go with 1.5 or double spacing. Standard margins.

Basically, show them you’re ready to write in college by using the formatting you’ll normally use in college.

Is there a college essay template I can use?

Depends on what you’re asking for. If, by “template,” you’re referring to formatting … see above.

But if you mean a structural template ... not exactly. There is no one college essay template to follow. And that’s a good thing.

That said, we’ve found that there are two basic structural approaches to writing college essays that can work for every single prompt we’ve seen. (Except for lists. Because … they’re lists.)

Below we’ll cover those two essay structures we love, but you’ll see how flexible these are—they can lead to vastly different essays. You can also check out a few sample essays to get a sense of structure and format (though we’d recommend doing some brainstorming and outlining to think of possible topics before you look at too many samples, since they can poison the well for some people).

Let’s dig in.

STEP 1: HOW TO BRAINSTORM AN AMAZING ESSAY TOPIC

We’ll talk about structure and topic together. Why? Because one informs the other.

(And to clarify: When we say, “topic,” we mean the theme or focus of your essay that you use to show who you are and what you value. The “topic” of your college essay is always ultimately you.)

We think there are two basic structural approaches that can work for any college essay. Not that these are the only two options—rather, that these can work for any and every prompt you’ll have to write for.

Which structural approach you use depends on your answer to this question (and its addendum): Do you feel like you’ve faced significant challenges in your life … or not so much? (And do you want to write about them?)

If yes (to both), you’ll most likely want to use Narrative Structure . If no (to either), you’ll probably want to try Montage Structure .

So … what are those structures? And how do they influence your topic?

Narrative Structure is classic storytelling structure. You’ve seen this thousands of times—assuming you read, and watch movies and TV, and tell stories with friends and family. If you don’t do any of these things, this might be new. Otherwise, you already know this. You may just not know you know it. Narrative revolves around a character or characters (for a college essay, that’s you) working to overcome certain challenges, learning and growing, and gaining insight. For a college essay using Narrative Structure, you’ll focus the word count roughly equally on a) Challenges You Faced, b) What You Did About Them, and c) What You Learned (caveat that those sections can be somewhat interwoven, especially b and c). Paragraphs and events are connected causally.

You’ve also seen montages before. But again, you may not know you know. So: A montage is a series of thematically connected things, frequently images. You’ve likely seen montages in dozens and dozens of films before—in romantic comedies, the “here’s the couple meeting and dating and falling in love” montage; in action movies, the classic “training” montage. A few images tell a larger story. In a college essay, you could build a montage by using a thematic thread to write about five different pairs of pants that connect to different sides of who you are and what you value. Or different but connected things that you love and know a lot about (like animals, or games). Or entries in your Happiness Spreadsheet .

How does structure play into a great topic?

We believe a montage essay (i.e., an essay NOT about challenges) is more likely to stand out if the topic or theme of the essay is:

X. Elastic (i.e., something you can connect to variety of examples, moments, or values) Y. Uncommon (i.e., something other students probably aren’t writing about)

We believe that a narrative essay is more likely to stand out if it contains:

X. Difficult or compelling challenges Y. Insight

These aren’t binary—rather, each exists on a spectrum.

“Elastic” will vary from person to person. I might be able to connect mountain climbing to family, history, literature, science, social justice, environmentalism, growth, insight … and someone else might not connect it to much of anything. Maybe trees?

“Uncommon” —every year, thousands of students write about mission trips, sports, or music. It’s not that you can’t write about these things, but it’s a lot harder to stand out.

“Difficult or compelling challenges” can be put on a spectrum, with things like getting a bad grade or not making a sports team on the weaker end, and things like escaping war or living homeless for three years on the stronger side. While you can possibly write a strong essay about a weaker challenge, it’s really hard to do so.

“Insight” is the answer to the question “so what?” A great insight is likely to surprise the reader a bit, while a so-so insight likely won’t. (Insight is something you’ll develop in an essay through the writing process, rather than something you’ll generally know ahead of time for a topic, but it’s useful to understand that some topics are probably easier to pull insights from than others.)

To clarify, you can still write a great montage with a very common topic, or a narrative that offers so-so insights. But the degree of difficulty goes up. Probably way up.

With that in mind, how do you brainstorm possible topics that are on the easier-to-stand-out-with side of the spectrum?

Brainstorming exercises

Spend about 10 minutes (minimum) on each of these exercises.

Values Exercise

Essence Objects Exercise

21 Details Exercise

Everything I Want Colleges To Know About Me Exercise

Feelings and Needs Exercise

If you feel like you already have your topic, and you just want to know how to make it better…

Still do those exercises.

Maybe what you have is the best topic for you. And if you are incredibly super sure, you can skip ahead. But if you’re not sure this topic helps you communicate your deepest stories, spend a little time on the exercises above. As a bonus, even if you end up going with what you already had (though please be wary of the sunk cost fallacy ), all that brainstorming will be useful when you write your supplemental essays .

The Feelings and Needs Exercise in particular is great for brainstorming Narrative Structure, connecting story events in a causal way (X led to Y led to Z). The Essence Objects, 21 Details, Everything I Want Colleges to Know exercises can lead to interesting thematic threads for Montage Structure (P, Q, and R are all connected because, for example, they’re all qualities of a great endodontist). But all of them are useful for both structural approaches. Essence objects can help a narrative come to life. One paragraph in a montage could focus on a challenge and how you overcame it.

The Values Exercise is a cornerstone of both—regardless of whether you use narrative or montage, we should get a sense of some of your core values through your essays.

How (and why) to outline your college essay to use a good structure

While not every professional writer knows exactly how a story will end when they start writing, they also have months (or years) to craft it, and they may throw major chunks or whole drafts away. You probably don’t want to throw away major chunks or whole drafts. So you should outline.

Use the brainstorming exercises from earlier to decide on your most powerful topics and what structure (narrative or montage) will help you best tell your story.

Then, outline.

For a narrative, use the Feelings and Needs Exercise, and build clear bullet points for the Challenges + Effects, What I Did About It, and What I Learned. Those become your outline.

Yeah, that simple.

For a montage, outline 4-7 ways your thread connects to different values through different experiences, and if you can think of them, different lessons and insights (though these you might have to develop later, during the writing process). For example, how auto repair connects to family, literature, curiosity, adventure, and personal growth (through different details and experiences).

Here are some good example outlines:

Narrative outline (developed from the Feelings and Needs Exercise)

Challenges:

Domestic abuse (physical and verbal)

Controlling father/lack of freedom

Sexism/bias

Prevented from pursuing opportunities

Cut off from world/family

Lack of sense of freedom/independence

Faced discrimination

What I Did About It:

Pursued my dreams

Traveled to Egypt, London, and Paris alone

Challenged stereotypes

Explored new places and cultures

Developed self-confidence, independence, and courage

Grew as a leader

Planned events

What I Learned:

Inspired to help others a lot more

Learned about oppression, and how to challenge oppressive norms

Became closer with mother, somewhat healed relationship with father

Need to feel free

And here’s the essay that became: “ Easter ”

Montage outline:

Thread: Home

Values: Family, tradition, literature

Ex: “Tailgate Special,” discussions w/family, reading Nancy Drew

Perception, connection to family

Chinese sword dance

Values: Culture/heritage, meticulousness, dedication, creativity

Ex: Notebook, formations/choreography

Nuances of culture, power of connection

Values: Science/chemistry, curiosity

Synthesizing plat nanoparticles

Joy of discovery, redefining expectations

Governor’s School

Values: Exploration, personal growth

Knitting, physics, politics, etc.

Importance of exploring beyond what I know/am used to, taking risks

And here’s the essay that became: “ Home ”

When to scrap what you have and start over

Ultimately, you can’t know for sure if a topic will work until you try a draft or two. And maybe it’ll be great. But keep that sunk cost fallacy in mind, and be open to trying other things.

If you’re down the rabbit hole with a personal statement topic and just aren’t sure about it, the first step you should take is to ask for feedback. Find a partner who can help you examine it without the attachment to all the emotion (anxiety, worry, or fear) you might have built up around it.

Have them help you walk through The Great College Essay Test to make sure your essay is doing its job. If it isn’t yet, does it seem like this topic has the potential to? Or would other topics allow you to more fully show a college who you are and what you bring to the table?

Because that’s your goal. Format and structure are just tools to get you there.

Down the Road

Before we analyze some sample essays, bookmark this page, so that once you’ve gone through several drafts of your own essay, come back and take The Great College Essay Test to make sure your essay is doing its job. The job of the essay, simply put, is to demonstrate to a college that you’ll make valuable contributions in college and beyond. We believe these four qualities are essential to a great essay:

Core values (showing who you are through what you value)

Vulnerability (helps a reader feel connected to you)

Insight (aka “so what” moments)

Craft (clear structure, refined language, intentional choices)

To test what values are coming through, read your essay aloud to someone who knows you and ask:

Which values are clearly coming through the essay?

Which values are kind of there but could be coming through more clearly?

Which values could be coming through and were opportunities missed?

To know if you’re being vulnerable in your essay, ask:

Now that you’ve heard my story, do you feel closer to me?

What did you learn about me that you didn’t already know?

To search for “so what” moments of insight, review the claims you’re making in your essay. Are you reflecting on what these moments and experiences taught you? How have they changed you? Are you making common or (hopefully) uncommon connections? The uncommon connections are often made up of insights that are unusual or unexpected. (For more on how to test for this, click The Great College Essay Test link above.)

Craft comes through the sense that each paragraph, each sentence, each word is a carefully considered choice. That the author has spent time revising and refining. That the essay is interesting and succinct. How do you test this? For each paragraph, each sentence, each word, ask: Do I need this? (Huge caveat: Please avoid neurotic perfectionism here. We’re just asking you to be intentional with your language.)

Still feeling you haven’t found your topic? Here’s a list of 100 Brave and Interesting Questions . Read these and try freewriting on a few. See where they lead.

Finally, here’s an ...

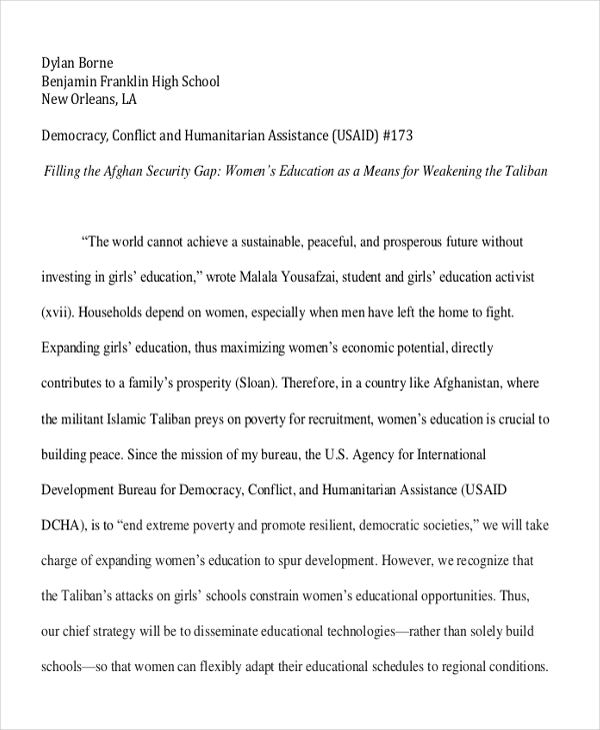

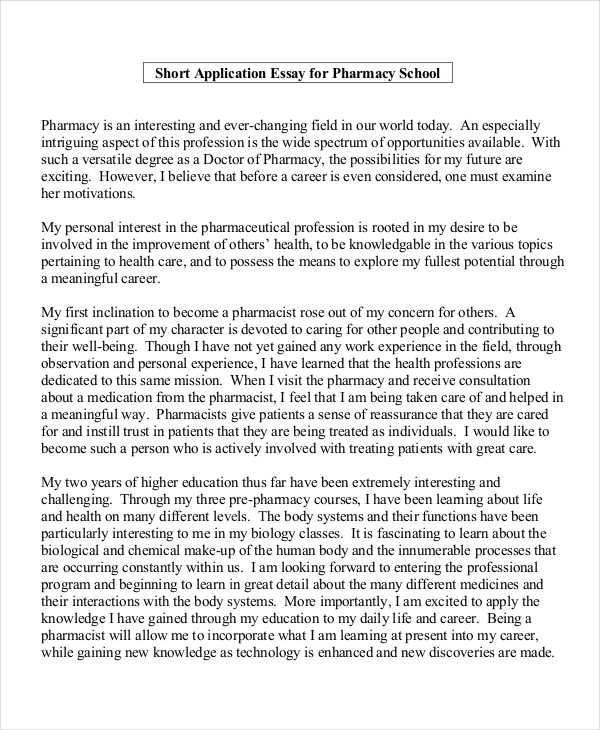

Example College Essay Format Analysis: The “Burying Grandma” Essay

To see how the Narrative Essay structure works, check out the essay below, which was written for the Common App "Topic of your choice" prompt. You might try reading it here first before reading the paragraph-by-paragraph breakdown below.

They covered the precious mahogany coffin with a brown amalgam of rocks, decomposed organisms, and weeds. It was my turn to take the shovel, but I felt too ashamed to dutifully send her off when I had not properly said goodbye. I refused to throw dirt on her. I refused to let go of my grandmother, to accept a death I had not seen coming, to believe that an illness could not only interrupt, but steal a beloved life.

The author begins by setting up the Challenges + Effects (you’ve maybe heard of this referred to in narrative as the Inciting Incident). This moment also sets up some of her needs: growth and emotional closure, to deal with it and let go/move on. Notice the way objects like the shovel help bring an essay to life, and can be used for symbolic meaning. That object will also come back later.

When my parents finally revealed to me that my grandmother had been battling liver cancer, I was twelve and I was angry--mostly with myself. They had wanted to protect me--only six years old at the time--from the complex and morose concept of death. However, when the end inevitably arrived, I wasn’t trying to comprehend what dying was; I was trying to understand how I had been able to abandon my sick grandmother in favor of playing with friends and watching TV. Hurt that my parents had deceived me and resentful of my own oblivion, I committed myself to preventing such blindness from resurfacing.

In the second paragraph, she flashes back to give us some context of what things were like leading up to these challenges (i.e., the Status Quo), which helps us understand her world. It also helps us to better understand the impact of her grandmother’s death and raises a question: How will she prevent such blindness from resurfacing?

I became desperately devoted to my education because I saw knowledge as the key to freeing myself from the chains of ignorance. While learning about cancer in school I promised myself that I would memorize every fact and absorb every detail in textbooks and online medical journals. And as I began to consider my future, I realized that what I learned in school would allow me to silence that which had silenced my grandmother. However, I was focused not with learning itself, but with good grades and high test scores. I started to believe that academic perfection would be the only way to redeem myself in her eyes--to make up for what I had not done as a granddaughter.

In the third paragraph, she starts shifting into the What I Did About It aspect, and takes off at a hundred miles an hour … but not quite in the right direction yet. What does that mean? She pursues things that, while useful and important in their own right, won’t actually help her resolve her conflict. This is important in narrative—while it can be difficult, or maybe even scary, to share ways we did things wrong, that generally makes for a stronger story. Think of it this way: You aren’t really interested in watching a movie in which a character faces a challenge, knows what to do the whole time, so does it, the end. We want to see how people learn and change and grow.

Here, the author “Raises the Stakes” because we as readers sense intuitively (and she is giving us hints) that this is not the way to get over her grandmother’s death.

However, a simple walk on a hiking trail behind my house made me open my own eyes to the truth. Over the years, everything--even honoring my grandmother--had become second to school and grades. As my shoes humbly tapped against the Earth, the towering trees blackened by the forest fire a few years ago, the faintly colorful pebbles embedded in the sidewalk, and the wispy white clouds hanging in the sky reminded me of my small though nonetheless significant part in a larger whole that is humankind and this Earth. Before I could resolve my guilt, I had to broaden my perspective of the world as well as my responsibilities to my fellow humans.

There’s some nice evocative detail in here that helps draw us into her world and experience.

Structurally, there are elements of What I Did About It and What I Learned in here (again, they will often be somewhat interwoven). This paragraph gives us the Turning Point/Moment of Truth. She begins to understand how she was wrong. She realizes she needs perspective. But how? See next paragraph ...

Volunteering at a cancer treatment center has helped me discover my path. When I see patients trapped in not only the hospital but also a moment in time by their diseases, I talk to them. For six hours a day, three times a week, Ivana is surrounded by IV stands, empty walls, and busy nurses that quietly yet constantly remind her of her breast cancer. Her face is pale and tired, yet kind--not unlike my grandmother’s. I need only to smile and say hello to see her brighten up as life returns to her face. Upon our first meeting, she opened up about her two sons, her hometown, and her knitting group--no mention of her disease. Without even standing up, the three of us—Ivana, me, and my grandmother--had taken a walk together.

In the second-to-last paragraph, we see how she takes further action, and some of what she learns from her experiences: Volunteering at the local hospital helps her see her larger place in the world.

Cancer, as powerful and invincible as it may seem, is a mere fraction of a person’s life. It’s easy to forget when one’s mind and body are so weak and vulnerable. I want to be there as an oncologist to remind them to take a walk once in a while, to remember that there’s so much more to life than a disease. While I physically treat their cancer, I want to lend patients emotional support and mental strength to escape the interruption and continue living. Through my work, I can accept the shovel without burying my grandmother’s memory.

The final paragraph uses what we call the “bookend” technique by bringing us back to the beginning, but with a change—she’s a different, slightly wiser person than she was. This helps us put a frame around her growth.

… A good story well told . That’s your goal.

Hopefully, you now have a better sense of how to make that happen.

For more resources, check out our College Application Hub .

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

MLA Format: The Ultimate Guide to Correctly Formatting Your Paper

Hannah Yang

So you need to create an MLA heading? You’re not alone—MLA format is one of the most common styles you’ll be expected to use when you’re writing a humanities paper, whether you’re a high-school student or a PhD candidate.

Read on to learn what a correct MLA heading looks like and how to create one that works like magic.

What Is an MLA Heading?

How do you format an mla heading, what is an mla header, how do you format an mla header, headings are only the beginning, commonly asked questions about mla headers, final thoughts.

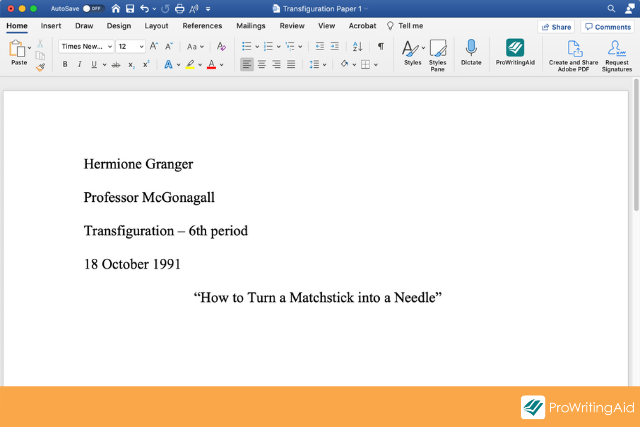

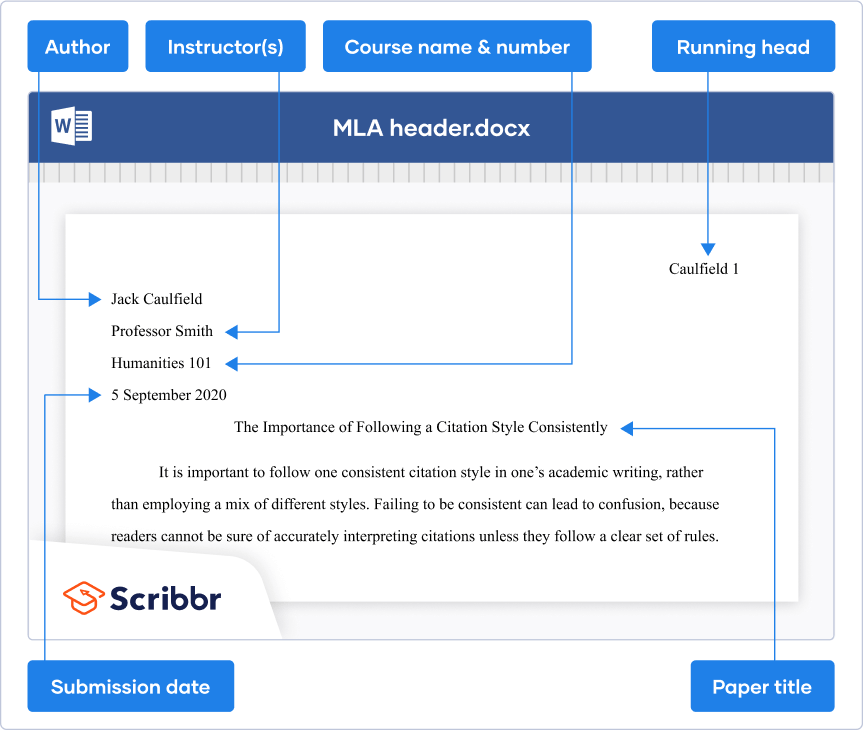

The term “MLA heading” refers to five lines of important information that appear at the top of the first page.

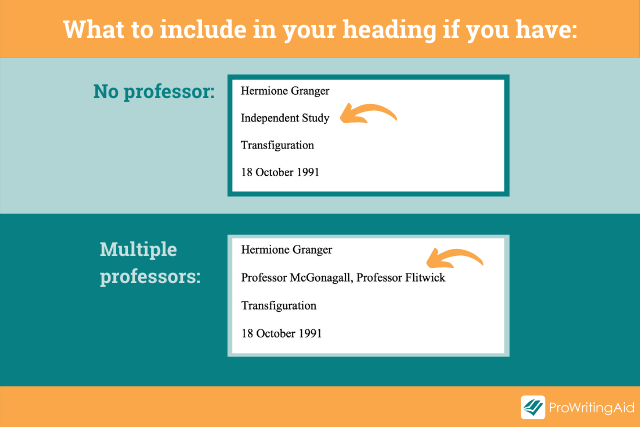

Here are two examples of what an MLA heading could look like:

Hermione Granger

Professor McGonagall

Transfiguration—6th period

18 October 1991

“How to Turn A Matchstick into a Needle”

Harry J. Potter

Prof. Remus Lupin

Defense Against the Dark Arts

4 March 1994

“Why I Think My Professor Is a Werewolf”

Why are these headings important? Well, your teacher probably collects hundreds of papers every year. If any identifying information is missing from these assignments, grading and organizing them becomes much more of a challenge.

MLA headings ensure that all key information is presented upfront. With just a glance at the first page, your teacher can easily figure out who wrote this paper, when it was submitted, and which class it was written for.

What Are the Parts of an MLA Heading?

An MLA heading should include:

- Your instructor’s name

- The name of the class

- The date the assignment is due

- The title of your paper

Your instructor may give you specific guidelines about how much detail to include in each line. For example, some teachers may ask you to refer to them by their titles, while others may ask you to use their full names. If you haven’t been given any specific instructions, don’t sweat it—any option is fine as long as it’s clear and consistent.

Follow these formatting rules for your MLA heading:

- Start each piece of information on a separate line

- Don’t use any periods, commas, or other punctuation at the end of the line

- Keep the heading double-spaced, in the same font as the rest of your paper

- Left-align the first four lines (they should start at the 1-inch margin on the left side of your paper)

- Center the title (it should appear in the middle of your paper)

- Make sure your title is in title case

Title case means that major words should be capitalized and minor words should be lowercase. Major words include nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, and any word longer than four letters. Minor words include conjunctions, prepositions, and articles.

Tip: Remember that Hermione’s “Society for the Promotion of Elfish Welfare” shortens to S.P.E.W., not S.F.T.P.O.E.W—only the major words are capitalized!

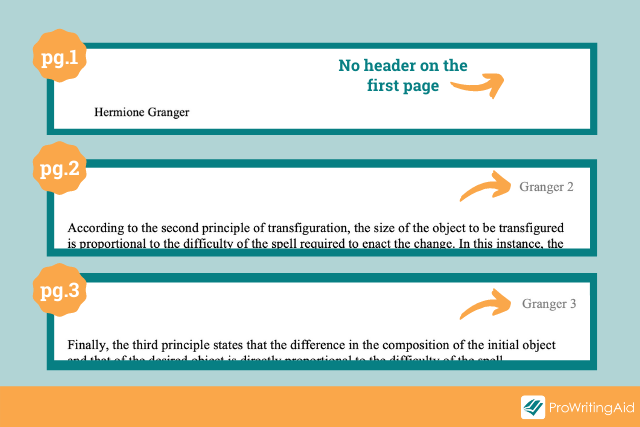

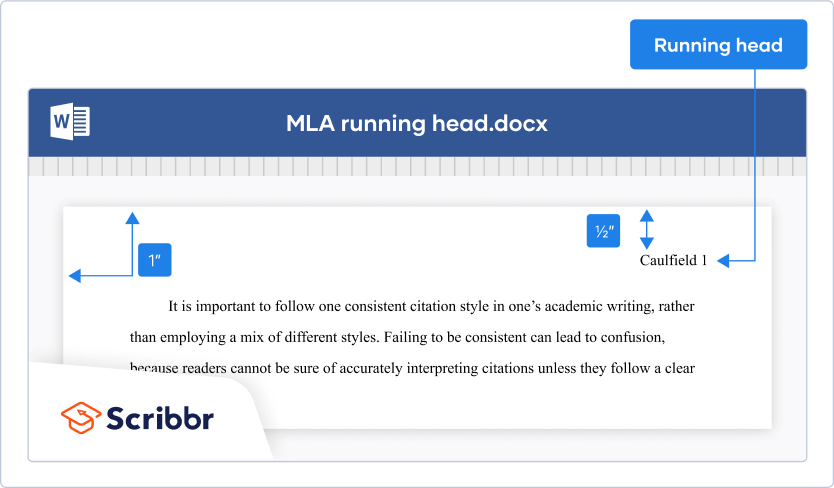

The MLA heading should only appear on the first page of your paper . But wait, you’re not done yet! In the rest of your paper, you need to include something called an MLA header at the top right corner of every page.

Think of the MLA header as a short, simple “You are here” marker that shows the reader where they are in the paper. By looking at the MLA headers, your instructor can easily understand where each page goes and which paper it belongs to.

What Are the Parts of an MLA Header?

The MLA header consists of your last name and page number.

For example, the second page of Hermione Granger’s essays would be labeled “Granger 2”, the third would be labeled “Granger 3”, and so on.

Creating MLA Headers in Microsoft Word

If you’re writing your paper in Microsoft Word, follow these steps:

- Click Insert

- Scroll down to Page Numbers and click on it

- Set the position to “Top of Page (Header)”

- Set the alignment to “Right”

- Make sure there’s no checkmark in the box for “Show number on first page”

- Click on the page number and type your last name before the number

- Set your font and font size to match the rest of your paper, if they don’t already

Creating MLA Headers in Google Docs

If you’re writing your paper in Google Docs, follow these steps:

- Scroll down to Page Numbers and hover over it

- Choose the option that sets your page number in the upper right corner

- Set your font and type size to match the rest of your paper, if they don’t already

Tip: After you create your first MLA header, save a template document for yourself that you can re-use next time, so you don’t have to follow these steps every time you write a paper!

Once you've got your headings sorted, it's time to start writing your paper. While we can't help you edit the content of your essay , ProWritingAid is here to make sure your grammar, spelling, and style is on point.

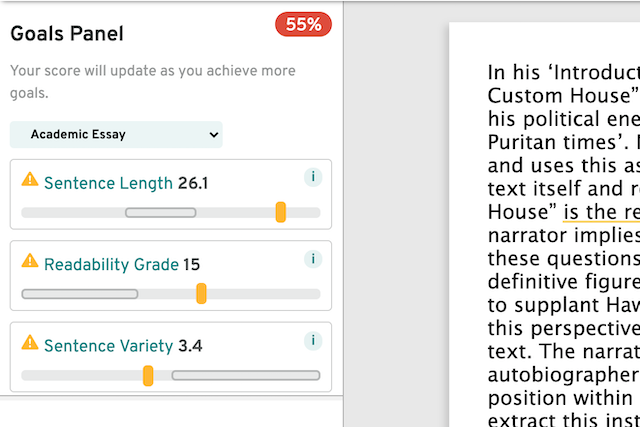

As well as checking your grammar, ProWritingAid also shows you your progress towards key goals like varied sentence structure, active voice, readability, and more. The target scores are all based on averages for real essays, so you'll always know if you're on track.

Ready to start receiving feedback before you submit your work?

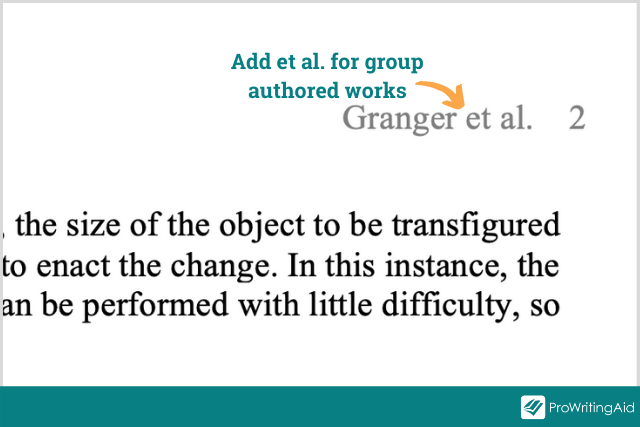

Whose last name should you use in your MLA header if you’re writing a group paper?

The MLA Style Guide has no specific guidelines for group projects. You should always include the names of all members of the group project in the first line of your heading, but you don’t necessarily need to do this for the header on every page.

If there are only two or three authors collaborating on your paper, you can include all of your last names in the MLA header, e.g., “Granger, Potter, and Weasley 2.”

If you’re part of a bigger group and it would take up too much space to include all of your last names, you can write the name that comes first in the alphabet and then add “ et al. ”, e.g., “Granger et al. 2.” (The term “et al.” is short for the Latin term “et alia”, which means “and others.” You’ll often see it used in academic papers with multiple authors.)

Should you include your class period in your MLA heading or just the class name?

There’s no MLA rule about this, but when in doubt, it’s always better to err on the side of including too much information in your heading rather than not enough.

If your instructor teaches more than one version of the same course, they’ll probably find it helpful if you specify the class period you’re in. You can either include your class period after the class name, e.g., “History of Magic—2nd period”, or before the class name, e.g., “2nd Period History of Magic.”

What should you write in your MLA heading if you don’t have an instructor?

If you have no instructor, you can explain the situation in the line where you would normally put the instructor’s name, e.g., “Independent Study” or “No Instructor.”

What should you write in your MLA heading if you have multiple instructors?

If you have multiple instructors, you can include both of their names in the line where you would put the instructor’s name. If you’re in a college course where you have a professor and a TA, you should choose whose name to include in the header depending on who will ultimately be reading your paper.

Should you include the date you started writing the paper or the date the paper is due?

The MLA Style Guide has no specific guidelines about which date you need to put in the heading. In general, however, the best practice is to put the date the assignment is due.

This is because all the papers for the same assignment will have the same due date, even if different students begin writing their assignments on different days, so it’s easier for your instructor to use the due date to determine what assignment the paper is for.

Should you format the date as Day Month Year or Month Day Year?

In MLA format, you should write the date in the order of Day Month Year. Instead of writing May 31 2021, for example, you would write 31 May 2021.

What font should you use for your MLA heading and header?

Both the heading and the header should be in the same font as the rest of your paper. If you haven’t chosen a font for your paper yet, remember that the key thing to aim for is readability. If you choose a font where your teachers have to squint to read it, or one where your teachers can’t figure out the difference between what’s italicized and what isn’t, you should rethink your choice.

When in doubt, go with Times New Roman, 12 pt. It’s always a safe bet for MLA papers unless your instructor specifically tells you otherwise.

Do you need to italicize or bold the title of your MLA paper?

No. There’s no need to use any special styling on the title of an MLA paper, such as bold or italics.

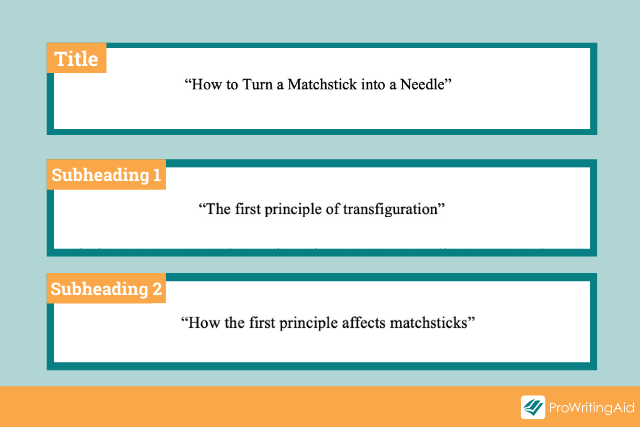

How do you format section titles in your MLA paper?

If you’re writing a paper with multiple sections, you may need to include a subtitle at the top of each section.

The MLA Style Guide gives you two options for using subtitles in a paper: one-level section titles or several-level subtitles (for papers with subsections within each section).

For one-level section titles, the formatting is simple. Every subtitle should look the same as the title (centered and double-spaced, with no special formatting).

The only difference is that instead of using title case, you should capitalize only the first word of each subtitle. For example, a title would be spelled “How to Turn a Matchstick into a Needle”, while a subtitle would be spelled “How to turn a matchstick into a needle.”

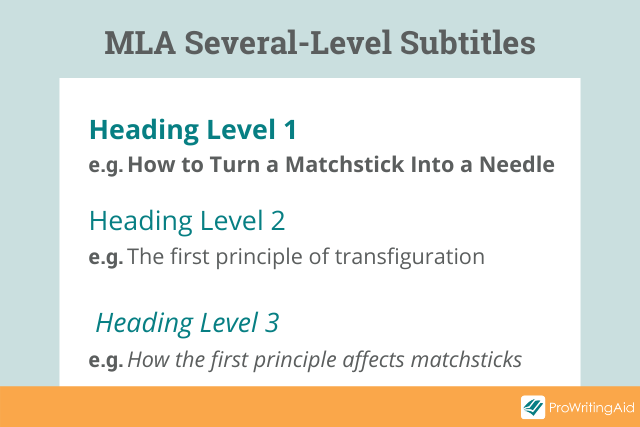

For several-level subtitles, you will need to format each level in a different way to show which level each section is at. You can use boldface, italics, and underlining to differentiate between levels. For example, subtitles at the highest level should be bolded, while subtitles at the next level down should be italicized.

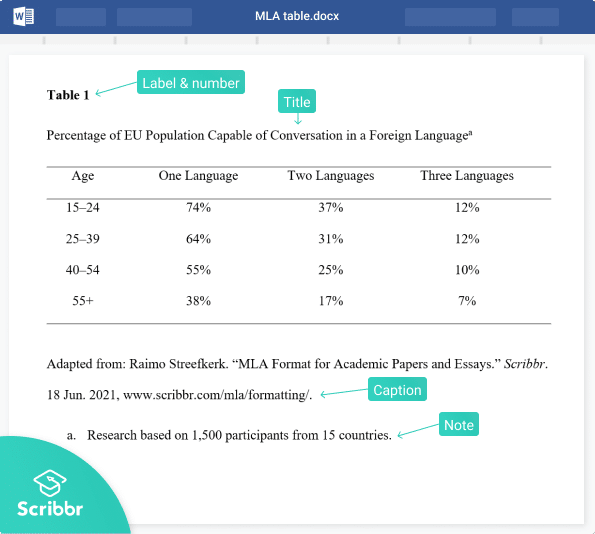

See the chart below for MLA’s suggested formats.

What is the difference between MLA format and APA format?

MLA and APA are two sets of guidelines for formatting papers and citing research.

MLA stands for the Modern Language Association. The MLA handbook is most often used in fields related to the humanities, such as literature, history, and philosophy.

APA stands for the American Psychological Association. The APA format is most often used in fields related to the social sciences, such as psychology, sociology, and nursing.

The APA manual includes a heading format similar to the MLA heading format with a few key differences, such as using a separate cover page instead of simply including the heading at the top of the first page. Both heading formats ensure that all of your papers include all your key identifying information in a clear and consistent way.

Where can you learn more about MLA style?

If you have questions about how to format a specific assignment or paper, it’s always best to consult your instructor first. Your school may also have a writing center that can help you with formatting questions.

In addition, Purdue has fantastic resources for all kinds of formatting topics, from MLA headings to MLA citations and everything in between.

If you would like to find out more directly from the Modern Language Association, consult the MLA Style Center or the MLA Handbook (8th edition).

Now you’re ready to write an MLA paper with a fantastic heading. Make sure your essay does your heading justice by checking it over with ProWritingAid.

Write Better Essays Every Time

Are your teachers always pulling you up on the same errors? Maybe you're losing clarity by writing overly long sentences or using the passive voice too much?

ProWritingAid helps you catch these issues in your essay before you submit it.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to format a college essay: 15 expert tips.

College Essays

When you're applying to college, even small decisions can feel high-stakes. This is especially true for the college essay, which often feels like the most personal part of the application. You may agonize over your college application essay format: the font, the margins, even the file format. Or maybe you're agonizing over how to organize your thoughts overall. Should you use a narrative structure? Five paragraphs?

In this comprehensive guide, we'll go over the ins and outs of how to format a college essay on both the micro and macro levels. We'll discuss minor formatting issues like headings and fonts, then discuss broad formatting concerns like whether or not to use a five-paragraph essay, and if you should use a college essay template.

How to Format a College Essay: Font, Margins, Etc.

Some of your formatting concerns will depend on whether you will be cutting and pasting your essay into a text box on an online application form or attaching a formatted document. If you aren't sure which you'll need to do, check the application instructions. Note that the Common Application does currently require you to copy and paste your essay into a text box.

Most schools also allow you to send in a paper application, which theoretically gives you increased control over your essay formatting. However, I generally don't advise sending in a paper application (unless you have no other option) for a couple of reasons:

Most schools state that they prefer to receive online applications. While it typically won't affect your chances of admission, it is wise to comply with institutional preferences in the college application process where possible. It tends to make the whole process go much more smoothly.

Paper applications can get lost in the mail. Certainly there can also be problems with online applications, but you'll be aware of the problem much sooner than if your paper application gets diverted somehow and then mailed back to you. By contrast, online applications let you be confident that your materials were received.

Regardless of how you will end up submitting your essay, you should draft it in a word processor. This will help you keep track of word count, let you use spell check, and so on.

Next, I'll go over some of the concerns you might have about the correct college essay application format, whether you're copying and pasting into a text box or attaching a document, plus a few tips that apply either way.

Formatting Guidelines That Apply No Matter How You End Up Submitting the Essay:

Unless it's specifically requested, you don't need a title. It will just eat into your word count.

Avoid cutesy, overly colloquial formatting choices like ALL CAPS or ~unnecessary symbols~ or, heaven forbid, emoji and #hashtags. Your college essay should be professional, and anything too cutesy or casual will come off as immature.

Mmm, delicious essay...I mean sandwich.

Why College Essay Templates Are a Bad Idea

You might see college essay templates online that offer guidelines on how to structure your essay and what to say in each paragraph. I strongly advise against using a template. It will make your essay sound canned and bland—two of the worst things a college essay can be. It's much better to think about what you want to say, and then talk through how to best structure it with someone else and/or make your own practice outlines before you sit down to write.

You can also find tons of successful sample essays online. Looking at these to get an idea of different styles and topics is fine, but again, I don't advise closely patterning your essay after a sample essay. You will do the best if your essay really reflects your own original voice and the experiences that are most meaningful to you.

College Application Essay Format: Key Takeaways

There are two levels of formatting you might be worried about: the micro (fonts, headings, margins, etc) and the macro (the overall structure of your essay).

Tips for the micro level of your college application essay format:

- Always draft your essay in a word processing software, even if you'll be copy-and-pasting it over into a text box.

- If you are copy-and-pasting it into a text box, make sure your formatting transfers properly, your paragraphs are clearly delineated, and your essay isn't cut off.

- If you are attaching a document, make sure your font is easily readable, your margins are standard 1-inch, your essay is 1.5 or double-spaced, and your file format is compatible with the application specs.

- There's no need for a title unless otherwise specified—it will just eat into your word count.

Tips for the macro level of your college application essay format :

- There is no super-secret college essay format that will guarantee success.

- In terms of structure, it's most important that you have an introduction that makes it clear where you're going and a conclusion that wraps up with a main point. For the middle of your essay, you have lots of freedom, just so long as it flows logically!

- I advise against using an essay template, as it will make your essay sound stilted and unoriginal.

Plus, if you use a college essay template, how will you get rid of these medieval weirdos?

What's Next?

Still feeling lost? Check out our total guide to the personal statement , or see our step-by-step guide to writing the perfect essay .

If you're not sure where to start, consider these tips for attention-grabbing first sentences to college essays!

And be sure to avoid these 10 college essay mistakes .

Ellen has extensive education mentorship experience and is deeply committed to helping students succeed in all areas of life. She received a BA from Harvard in Folklore and Mythology and is currently pursuing graduate studies at Columbia University.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write Any High School Essay

Last Updated: March 22, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA and by wikiHow staff writer, Hunter Rising . Emily Listmann is a private tutor in San Carlos, California. She has worked as a Social Studies Teacher, Curriculum Coordinator, and an SAT Prep Teacher. She received her MA in Education from the Stanford Graduate School of Education in 2014. There are 14 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 562,393 times.

Writing an essay is an important basic skill that you will need to succeed in high school and college. While essays will vary depending on your teacher and the assignment, most essays will follow the same basic structure. By supporting your thesis with information in your body paragraphs, you can successfully write an essay for any course!

Writing Help

Planning Your Essay

- Expository essays uses arguments to investigate and explain a topic.

- Persuasive essays try to convince the readers to believe or accept your specific point of view

- Narrative essays tell about a real-life personal experience.

- Descriptive essays are used to communicate deeper meaning through the use of descriptive words and sensory details.

- Look through books or use search engines online to look at the broad topic before narrowing your ideas down into something more concise.

- For example, the statement “Elephants are used to perform in circuses” does not offer an arguable point. Instead, you may try something like “Elephants should not be kept in the circus since they are mistreated.” This allows you to find supporting arguments or for others to argue against it.

- Keep in mind that some essay writing will not require an argument, such as a narrative essay. Instead, you might focus on a pivotal point in the story as your main claim.

- Talk to your school’s librarian for direction on specific books or databases you could use to find your information.

- Many schools offer access to online databases like EBSCO or JSTOR where you can find reliable information.

- Wikipedia is a great starting place for your research, but it can be edited by anyone in the world. Instead, look at the article’s references to find the sites where the information really came from.

- Use Google Scholar if you want to find peer-reviewed scholarly articles for your sources.

- Make sure to consider the author’s credibility when reviewing sources. If a source does not include the author’s name, then it might not be a good option.

- Outlines will vary in size or length depending on how long your essay needs to be. Longer essays will have more body paragraphs to support your arguments.

Starting an Essay

- Make sure your quotes or information are accurate and not an exaggeration of the truth, or else readers will question your validity throughout the rest of your essay.

- For example, “Because global warming is causing the polar ice caps to melt, we need to eliminate our reliance on fossil fuels within the next 5 years.” Or, “Since flavored tobacco appeals mainly to children and teens, it should be illegal for tobacco manufacturers to sell these products.”

- The thesis is usually the last or second to last sentence in your introduction.

- Use the main topics of your body paragraphs as an idea of what to include in your mini-outline.

Writing the Body Paragraphs

- Think of your topic sentences as mini-theses so your paragraphs only argue a specific point.

- Many high school essays are written in MLA or APA style. Ask your teacher what format they want you to follow if it’s not specified.

- Unless you’re writing a personal essay, avoid the use of “I” statements since this could make your essay look less professional.

- For example, if your body paragraphs discuss similar points in a different way, you can use phrases like “in the same way,” “similarly,” and “just as” to start other body paragraphs.

- If you are posing different points, try phrases like “in spite of,” “in contrast,” or “however” to transition.

Concluding Your Essay

- For example, if your thesis was, “The cell phone is the most important invention in the past 30 years,” then you may restate the thesis in your conclusion like, “Due to the ability to communicate anywhere in the world and access information easily, the cell phone is a pivotal invention in human history.”

- If you’re only writing a 1-page paper, restating your main ideas isn’t necessary.

- For example, if you write an essay discussing the themes of a book, think about how the themes are affecting people’s lives today.

- Try to pick the same type of closing sentence as you used as your attention getter.

- Including a Works Cited page shows that the information you provided isn’t all your own and allows the reader to visit the sources to see the raw information for themselves.

- Avoid using online citation machines since they may be outdated.

Revising the Paper

- Have a peer or parent read through your essay to see if they understand what point you’re trying to make.

- For example, if your essay discusses the history of an event, make sure your sentences flow in a chronological way in the order the events happened.

- If you cut parts out of your essay, make sure to reread it to see if it affects the flow of how it reads.

Community Q&A

- Allow ample time to layout your essay before you get started writing. Thanks Helpful 2 Not Helpful 0

- If you have writer's block , take a break for a few minutes. Thanks Helpful 2 Not Helpful 2

- Check the rubric provided by your teacher and compare your essay to it. This helps you gauge what you need to include or change. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 1

- Avoid using plagiarism since this could result in academic consequences. Thanks Helpful 5 Not Helpful 1

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.grammarly.com/blog/types-of-essays/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/thesis-statements/

- ↑ https://guides.libs.uga.edu/reliability

- ↑ https://facultyweb.ivcc.edu/rrambo/eng1001/outline.htm

- ↑ https://examples.yourdictionary.com/20-compelling-hook-examples-for-essays.html

- ↑ https://wts.indiana.edu/writing-guides/how-to-write-a-thesis-statement.html

- ↑ https://guidetogrammar.org/grammar/five_par.htm

- ↑ https://learning.hccs.edu/faculty/jason.laviolette/persuasive-essay-outline

- ↑ https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/writingcenter/paragraphs/topicsentences

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/transitions/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/ending-essay-conclusions

- ↑ https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/how-to-write-an-essay/conclusion

- ↑ https://pitt.libguides.com/citationhelp

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/revising-drafts/

About This Article

Writing good essays is an important skill to have in high school, and you can write a good one by planning it out and organizing it well. Before you start, do some research on your topic so you can come up with a strong, specific thesis statement, which is essentially the main argument of your essay. For instance, your thesis might be something like, “Elephants should not be kept in the circus because they are mistreated.” Once you have your thesis, outline the paragraphs for your essay. You should have an introduction that includes your thesis, at least 3 body paragraphs that explain your main points, and a conclusion paragraph. Start each body paragraph with a topic sentence that states the main point of the paragraph. As you write your main points, make sure to include evidence and quotes from your research to back it up. To learn how to revise your paper, read more from our Writing co-author! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Ariel Arias Petzoldt

Aug 25, 2020

Did this article help you?

Nov 22, 2017

Rose Mpangala

Oct 24, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, how to format a college essay header.

Hi guys, I'm writing my college essays and I was wondering what the proper header format is for a college essay? Should I include my name, date, class, or anything else? Thanks in advance!

Hi there! When it comes to formatting a college essay header, simplicity is key. Most colleges prefer the following format:

- In the top left corner of the first page, include your full name, followed by a space, and then your high school (or the abbreviation of your high school name).

- On the line below your high school's name, type the course title (if applicable) or the purpose of the essay (for example, "Personal Statement" or "X School Supplement").

- Add one more space, and then type the date of submission.

It should look something like this:

City High School

Personal Statement

December 1, 2023

For the body of the essay, use 12-point font, double-spacing, and 1-inch margins. Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri are common font choices. Don't forget to proofread and check for any specific formatting requirements provided by the colleges you're applying to.

Keep in mind that for schools that use the Common App you won't need to format your essay like this; you just copy and paste your essay into the provided text boxes. Good luck with your essays!

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

MLA General Format

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

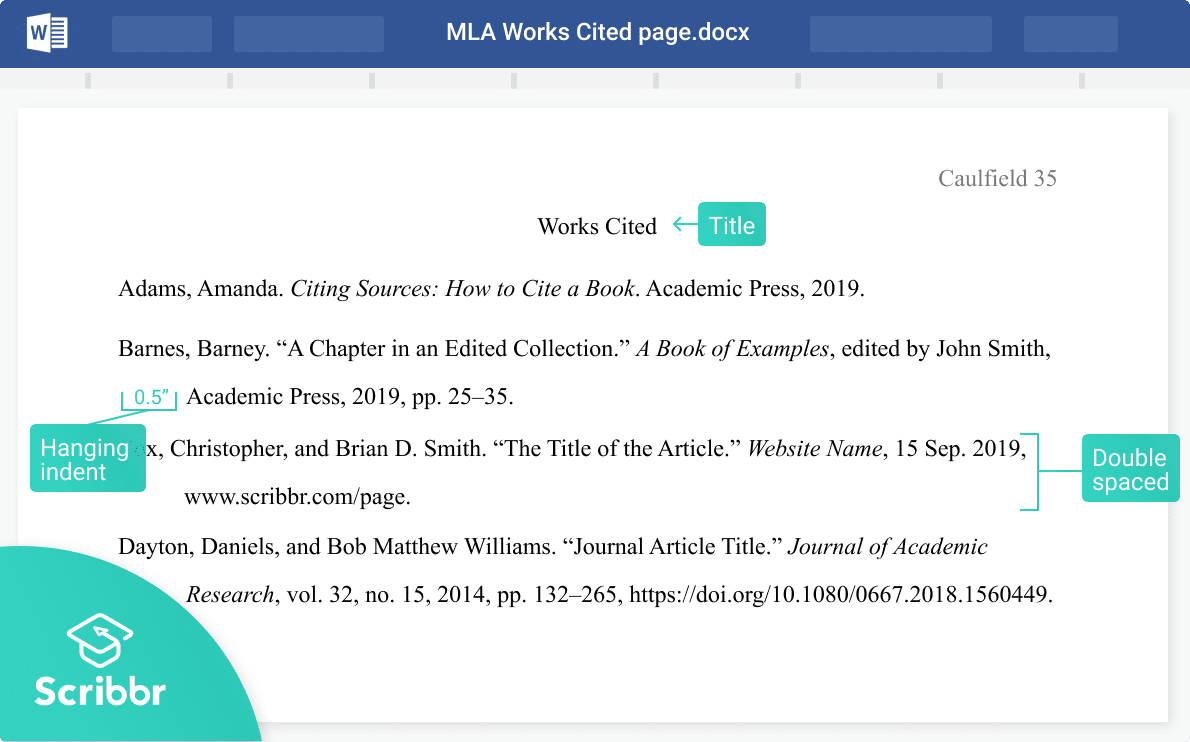

MLA Style specifies guidelines for formatting manuscripts and citing research in writing. MLA Style also provides writers with a system for referencing their sources through parenthetical citation in their essays and Works Cited pages.

Writers who properly use MLA also build their credibility by demonstrating accountability to their source material. Most importantly, the use of MLA style can protect writers from accusations of plagiarism, which is the purposeful or accidental uncredited use of source material produced by other writers.

If you are asked to use MLA format, be sure to consult the MLA Handbook (9th edition). Publishing scholars and graduate students should also consult the MLA Style Manual and Guide to Scholarly Publishing (3rd edition). The MLA Handbook is available in most writing centers and reference libraries. It is also widely available in bookstores, libraries, and at the MLA web site. See the Additional Resources section of this page for a list of helpful books and sites about using MLA Style.

Paper Format

The preparation of papers and manuscripts in MLA Style is covered in part four of the MLA Style Manual . Below are some basic guidelines for formatting a paper in MLA Style :

General Guidelines

- Type your paper on a computer and print it out on standard, white 8.5 x 11-inch paper.

- Double-space the text of your paper and use a legible font (e.g. Times New Roman). Whatever font you choose, MLA recommends that the regular and italics type styles contrast enough that they are each distinct from one another. The font size should be 12 pt.

- Leave only one space after periods or other punctuation marks (unless otherwise prompted by your instructor).

- Set the margins of your document to 1 inch on all sides.

- Indent the first line of each paragraph one half-inch from the left margin. MLA recommends that you use the “Tab” key as opposed to pushing the space bar five times.

- Create a header that numbers all pages consecutively in the upper right-hand corner, one-half inch from the top and flush with the right margin. (Note: Your instructor may ask that you omit the number on your first page. Always follow your instructor's guidelines.)

- Use italics throughout your essay to indicate the titles of longer works and, only when absolutely necessary, provide emphasis.

- If you have any endnotes, include them on a separate page before your Works Cited page. Entitle the section Notes (centered, unformatted).

Formatting the First Page of Your Paper

- Do not make a title page for your paper unless specifically requested or the paper is assigned as a group project. In the case of a group project, list all names of the contributors, giving each name its own line in the header, followed by the remaining MLA header requirements as described below. Format the remainder of the page as requested by the instructor.

- In the upper left-hand corner of the first page, list your name, your instructor's name, the course, and the date. Again, be sure to use double-spaced text.

- Double space again and center the title. Do not underline, italicize, or place your title in quotation marks. Write the title in Title Case (standard capitalization), not in all capital letters.

- Use quotation marks and/or italics when referring to other works in your title, just as you would in your text. For example: Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas as Morality Play; Human Weariness in "After Apple Picking"

- Double space between the title and the first line of the text.

- Create a header in the upper right-hand corner that includes your last name, followed by a space with a page number. Number all pages consecutively with Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, 4, etc.), one-half inch from the top and flush with the right margin. (Note: Your instructor or other readers may ask that you omit the last name/page number header on your first page. Always follow instructor guidelines.)

Here is a sample of the first page of a paper in MLA style:

The First Page of an MLA Paper

Section Headings

Writers sometimes use section headings to improve a document’s readability. These sections may include individual chapters or other named parts of a book or essay.

MLA recommends that when dividing an essay into sections you number those sections with an Arabic number and a period followed by a space and the section name.

MLA does not have a prescribed system of headings for books (for more information on headings, please see page 146 in the MLA Style Manual and Guide to Scholarly Publishing , 3rd edition). If you are only using one level of headings, meaning that all of the sections are distinct and parallel and have no additional sections that fit within them, MLA recommends that these sections resemble one another grammatically. For instance, if your headings are typically short phrases, make all of the headings short phrases (and not, for example, full sentences). Otherwise, the formatting is up to you. It should, however, be consistent throughout the document.

If you employ multiple levels of headings (some of your sections have sections within sections), you may want to provide a key of your chosen level headings and their formatting to your instructor or editor.

Sample Section Headings

The following sample headings are meant to be used only as a reference. You may employ whatever system of formatting that works best for you so long as it remains consistent throughout the document.

Formatted, unnumbered:

Level 1 Heading: bold, flush left

Level 2 Heading: italics, flush left

Level 3 Heading: centered, bold

Level 4 Heading: centered, italics

Level 5 Heading: underlined, flush left

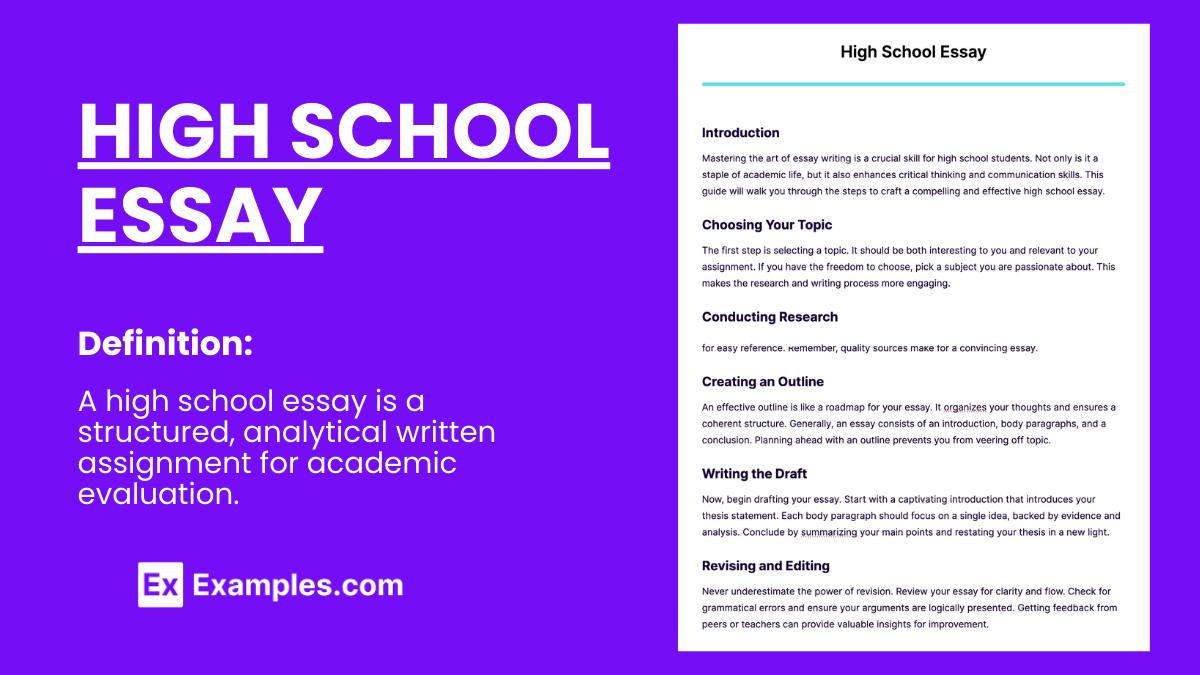

High School Essay

Navigating the complexities of High School Essay writing can be a challenging yet rewarding experience. Our guide, infused with diverse essay examples , is designed to simplify this journey for students. High school essays are a crucial part of academic development, allowing students to express their thoughts, arguments, and creativity. With our examples, students learn to structure their essays effectively, develop strong thesis statements, and convey their ideas with clarity and confidence, paving the way for academic success.

What Is a High School Essay? A high school essay is anything that falls between a literary piece that teachers would ask their students to write. It could be anything like an expository essay , informative essay , or a descriptive essay . High school essay is just a broad term that is used to describe anything that high school student writes, probably in subjects like English Grammar or Literature.

It is a good way to practice every student’s writing skills in writing which they might find useful when they reach college. Others might even be inspired to continue writing and take courses that are related to it.

Download High School Essay Bundle

When you are in high school, it is definite that you are expected to do some write-ups and projects which require pen and paper. Yes. You heard that right. Your teachers are going to let you write a lot of things starting from short stories to other things like expository essays. However, do not be intimidated nor fear the things that I have just said. It is but a normal part of being a student to write things. Well, take it from me. As far as I can recall, I may have written about a hundred essays during my entire high school years or maybe more. You may also see what are the parts of an essay?

High School Essay Format

1. introduction.

Hook: Start with an engaging sentence to capture the reader’s interest. This could be a question, a quote, a surprising fact, or a bold statement related to your topic. Background Information: Provide some background information on your topic to help readers understand the context of your essay. Thesis Statement: End the introduction with a clear thesis statement that outlines your main argument or point of view. This statement guides the direction of your entire essay.

2. Body Paragraphs

Topic Sentence: Start each body paragraph with a topic sentence that introduces the main idea of the paragraph, supporting your thesis statement. Supporting Details: Include evidence, examples, facts, and quotes to support the main idea of each paragraph. Make sure to explain how these details relate to your topic sentence and thesis statement. Analysis: Provide your analysis or interpretation of the evidence and how it supports your argument. Be clear and concise in explaining your reasoning. Transition: Use transition words or phrases to smoothly move from one idea to the next, maintaining the flow of your essay.

3. Conclusion

Summary: Begin your conclusion by restating your thesis in a new way, summarizing the main points of your body paragraphs without introducing new information. Final Thoughts: End your essay with a strong closing statement. This could be a reflection on the significance of your argument, a call to action, or a rhetorical question to leave the reader thinking.

Example of High School Essay

Community service plays a pivotal role in fostering empathy, building character, and enhancing societal well-being. It offers a platform for young individuals to contribute positively to society while gaining valuable life experiences. This essay explores the significance of community service and its impact on both individuals and communities. Introduction Community service, an altruistic activity performed for the betterment of society, is a cornerstone for personal growth and societal improvement. It not only addresses societal needs but also cultivates essential virtues in volunteers. Through community service, high school students can develop a sense of responsibility, a commitment to altruism, and an understanding of their role in the community. Personal Development Firstly, community service significantly contributes to personal development. Volunteering helps students acquire new skills, such as teamwork, communication, and problem-solving. For instance, organizing a local food drive can teach students project management skills and the importance of collaboration. Moreover, community service provides insights into one’s passions and career interests, guiding them towards fulfilling future endeavors. Social Impact Secondly, the social impact of community service cannot be overstated. Activities like tutoring underprivileged children or participating in environmental clean-ups address critical societal issues directly. These actions not only bring about immediate positive changes but also inspire a ripple effect, encouraging a culture of volunteerism within the community. The collective effort of volunteers can transform neighborhoods, making them more supportive and resilient against challenges. Building Empathy and Understanding Furthermore, community service is instrumental in building empathy and understanding. Engaging with diverse groups and working towards a common goal fosters a sense of solidarity and compassion among volunteers. For example, spending time at a senior center can bridge the generational gap, enriching the lives of both the elderly and the volunteers. These experiences teach students the value of empathy, enriching their emotional intelligence and social awareness. In conclusion, community service is a vital component of societal development and personal growth. It offers a unique opportunity for students to engage with their communities, learn valuable life skills, and develop empathy. Schools and parents should encourage students to participate in community service, highlighting its benefits not only to the community but also in shaping responsible, caring, and informed citizens. As we look towards building a better future, the role of community service in education cannot be overlooked; it is an investment in our collective well-being and the development of the next generation.

Essay Topics for High School with Samples to Edit & Download

- Should schools have dress codes?

- Sex education in middle school

- Should homework be abolished?

- College education costs

- How does technology affect productivity?

- Is climate change reversible?

- Is social media helpful or harmful?

- Climate change is caused by humans

- Effects of social media on youth

- Are men and women treated equally?

- Are professional athletes overpaid?

- Changes over the past decade

- Guns should be more strictly regulated

- My favorite childhood memory

- Religion in school

- Should we stop giving final exams?

- Video game addiction

- Violence in media content

High School Essay Examples & Templates

Free Download

High School Essay For Students

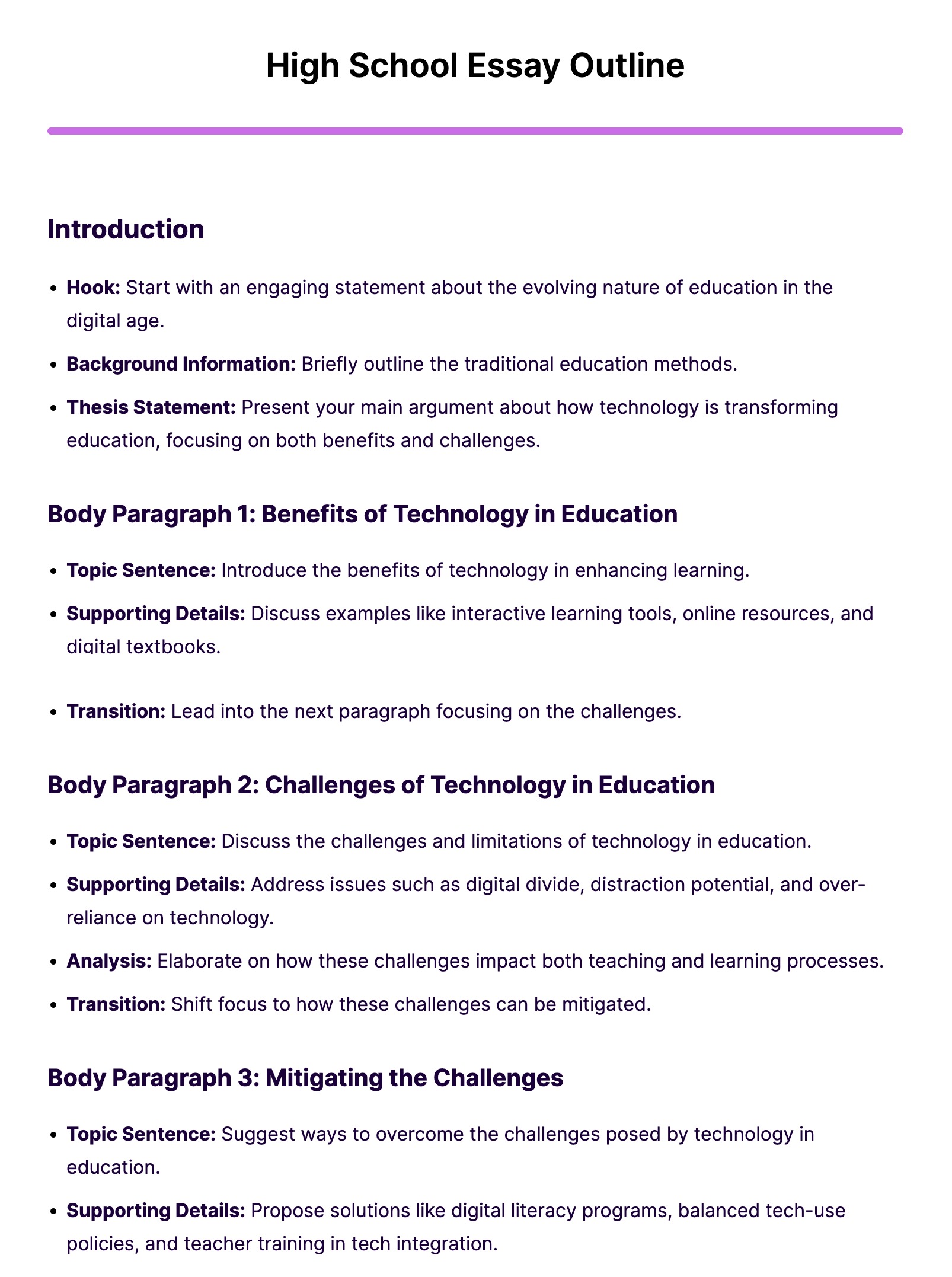

High School Essay Outline

High School Essay Example

High School Self Introduction Essay Template

High School Student Essay

englishdaily626.com

Reflective High School

oregoncis.uoregon.edu

Argumentative Essays for High School

Informative Essays for High School

High School Persuasive

writecook.com

Narrative Essays

Scholarship Essays

High School Application

e-education.psu.edu

High School Graduation Essay

High School Leadership Essay

web.extension.illinois.edu

How to Write a High School Essay

Some teachers are really not that strict when it comes to writing essay because they too understand the struggles of writing stuff like these. However, you need to know the basics when it comes to writing a high school essay.

1. Understand the Essay Prompt

- Carefully read the essay prompt or question to understand what’s required. Identify the type of essay (narrative, persuasive, expository, etc.) and the main topic you need to address.

2. Choose a Topic

- If the topic isn’t provided, pick one that interests you and fits the essay’s requirements. Make sure it’s neither too broad nor too narrow.

3. Conduct Research (if necessary)

- For expository, argumentative, or research essays, gather information from credible sources to support your arguments. Take notes and organize your findings.

4. Create an Outline

- Outline your essay to organize your thoughts and structure your arguments effectively. Include an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

5. Write the Introduction

- Start with a hook to grab the reader’s attention (a quote, a question, a shocking fact, etc.). Introduce your topic and end the introduction with a thesis statement that presents your main argument or purpose.

6. Develop Body Paragraphs

- Each body paragraph should focus on a single idea or argument that supports your thesis. Start with a topic sentence, provide evidence or examples, and explain how it relates to your thesis.

7. Write the Conclusion

- Summarize the main points of your essay and restate your thesis in a new way. Conclude with a strong statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

Types of High School Essay

1. narrative essay.

Narrative essays tell a story from the writer’s perspective, often highlighting a personal experience or event. The focus is on storytelling, including characters, a setting, and a plot, to engage readers emotionally. This type allows students to explore creativity and expressiveness in their writing.

2. Descriptive Essay

Descriptive essays focus on detailing and describing a person, place, object, or event. The aim is to paint a vivid picture in the reader’s mind using sensory details. These essays test the writer’s ability to use language creatively to evoke emotions and bring a scene to life.

3. Expository Essay

Expository essays aim to explain or inform the reader about a topic in a clear, concise manner. This type of essay requires thorough research and focuses on factual information. It’s divided into several types, such as compare and contrast, cause and effect, and process essays, each serving a specific purpose.

4. Persuasive Essay

Persuasive essays aim to convince the reader of a particular viewpoint or argument. The writer must use logic, reasoning, and evidence to support their position while addressing counterarguments. This type tests the writer’s ability to persuade and argue effectively.

5. Analytical Essay

Analytical essays require the writer to break down and analyze an element, such as a piece of literature, a movie, or a historical event. The goal is to interpret and make sense of the subject, discussing its significance and how it achieves its purpose.

6. Reflective Essay

Reflective essays are personal pieces that ask the writer to reflect on their experiences, thoughts, or feelings regarding a specific topic or experience. It encourages introspection and personal growth by examining one’s responses and learning from them.

7. Argumentative Essay

Similar to persuasive essays, argumentative essays require the writer to take a stance on an issue and argue for their position with evidence. However, argumentative essays place a stronger emphasis on evidence and logic rather than emotional persuasion.

8. Research Paper

Though often longer than a typical essay, research papers in high school require students to conduct in-depth study on a specific topic, using various sources to gather information. The focus is on presenting findings and analysis in a structured format.

Tips for High School Essays

Writing a high school essay if you have the tips on how to do essay effectively . This will give you an edge from your classmates.

- Stay Organized: Keep your notes and sources well-organized to make the writing process smoother.

- Be Clear and Concise: Avoid overly complex sentences or vocabulary that might confuse the reader.

- Use Transitions: Ensure that your paragraphs and ideas flow logically by using transition words and phrases.

- Cite Sources: If you use direct quotes or specific ideas from your research, make sure to cite your sources properly to avoid plagiarism.

- Practice: Like any skill, essay writing improves with practice. Don’t hesitate to write drafts and experiment with different writing styles.

Importance of High School Essay

Aside from the fact that you will get reprimanded for not doing your task, there are more substantial reasons why a high school essay is important. First, you get trained at a very young age. Writing is not just for those who are studying nor for your teachers. As you graduate from high school and then enter college (can see college essays ), you will have more things to write like dissertations and theses.

At least, when you get to that stage, you already know how to write. Aside from that, writing high essays give a life lesson. That is, patience and resourcefulness. You need to find the right resources for your essay as well as patience when finding the right inspiration to write.

How long is a high school essay?

A high school essay typically ranges from 500 to 2000 words, depending on the assignment’s requirements and the subject matter.

How do you start a personal essay for high school?

Begin with an engaging hook (an anecdote, quote, or question) that introduces your theme or story, leading naturally to your thesis or main point.

What makes a good high school essay?

A good high school essay features a clear thesis, coherent structure, compelling evidence, and personal insights, all presented in a polished, grammatically correct format.

High School Essay Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Write a High School Essay on the importance of participating in sports.

Discuss the role of student government in high schools in a High School Essay.

How to Make a Cover Page: APA and MLA Format

A cover page is the first page of a paper or report that lists basic information, such as the title, author(s), course name, instructor, date, and sometimes the name of the institution. Also known as a title page, a cover page is a requirement of some formatting styles. But certain instructors or assignments may request them regardless of the style requirements.

When a cover page is required, it has specific rules for what to include and how to format it that depend on the style. In this guide, we explain how to create a cover page in different formatting styles and what you need to use it correctly.

What is a cover page?