Dialogue Definition

What is dialogue? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Dialogue is the exchange of spoken words between two or more characters in a book, play, or other written work. In prose writing, lines of dialogue are typically identified by the use of quotation marks and a dialogue tag, such as "she said." In plays, lines of dialogue are preceded by the name of the person speaking. Here's a bit of dialogue from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland : "Oh, you can't help that,' said the Cat: 'we're all mad here. I'm mad. You're mad." "How do you know I'm mad?" said Alice. "You must be,' said the Cat, 'or you wouldn't have come here."

Some additional key details about dialogue:

- Dialogue is defined in contrast to monologue , when only one person is speaking.

- Dialogue is often critical for moving the plot of a story forward, and can be a great way of conveying key information about characters and the plot.

- Dialogue is also a specific and ancient genre of writing, which often takes the form of a philosophical investigation carried out by two people in conversation, as in the works of Plato. This entry, however, deals with dialogue as a narrative element, not as a genre.

How to Pronounce Dialogue

Here's how to pronounce dialogue: dye -uh-log

Dialogue in Depth

Dialogue is used in all forms of writing, from novels to news articles to plays—and even in some poetry. It's a useful tool for exposition (i.e., conveying the key details and background information of a story) as well as characterization (i.e., fleshing out characters to make them seem lifelike and unique).

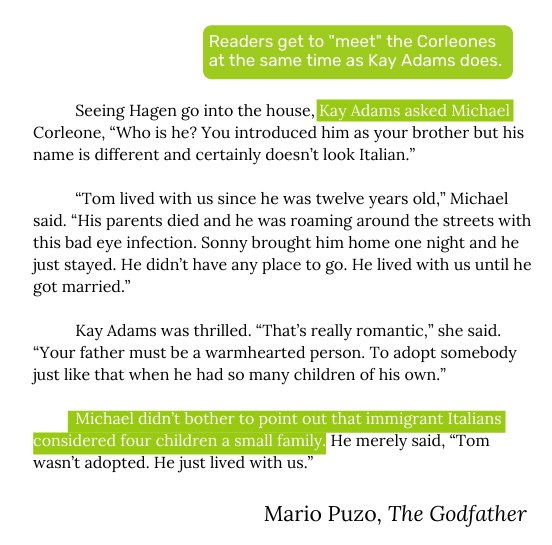

Dialogue as an Expository Tool

Dialogue is often a crucial expository tool for writers—which is just another way of saying that dialogue can help convey important information to the reader about the characters or the plot without requiring the narrator to state the information directly. For instance:

- In a book with a first person narrator, the narrator might identify themselves outright (as in Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go , which begins "My name is Kathy H. I am thirty-one years old, and I've been a carer now for over eleven years.").

- Tom Buchanan, who had been hovering restlessly about the room, stopped and rested his hand on my shoulder. "What you doing, Nick?”

The above example is just one scenario in which important information might be conveyed indirectly through dialogue, allowing writers to show rather than tell their readers the most important details of the plot.

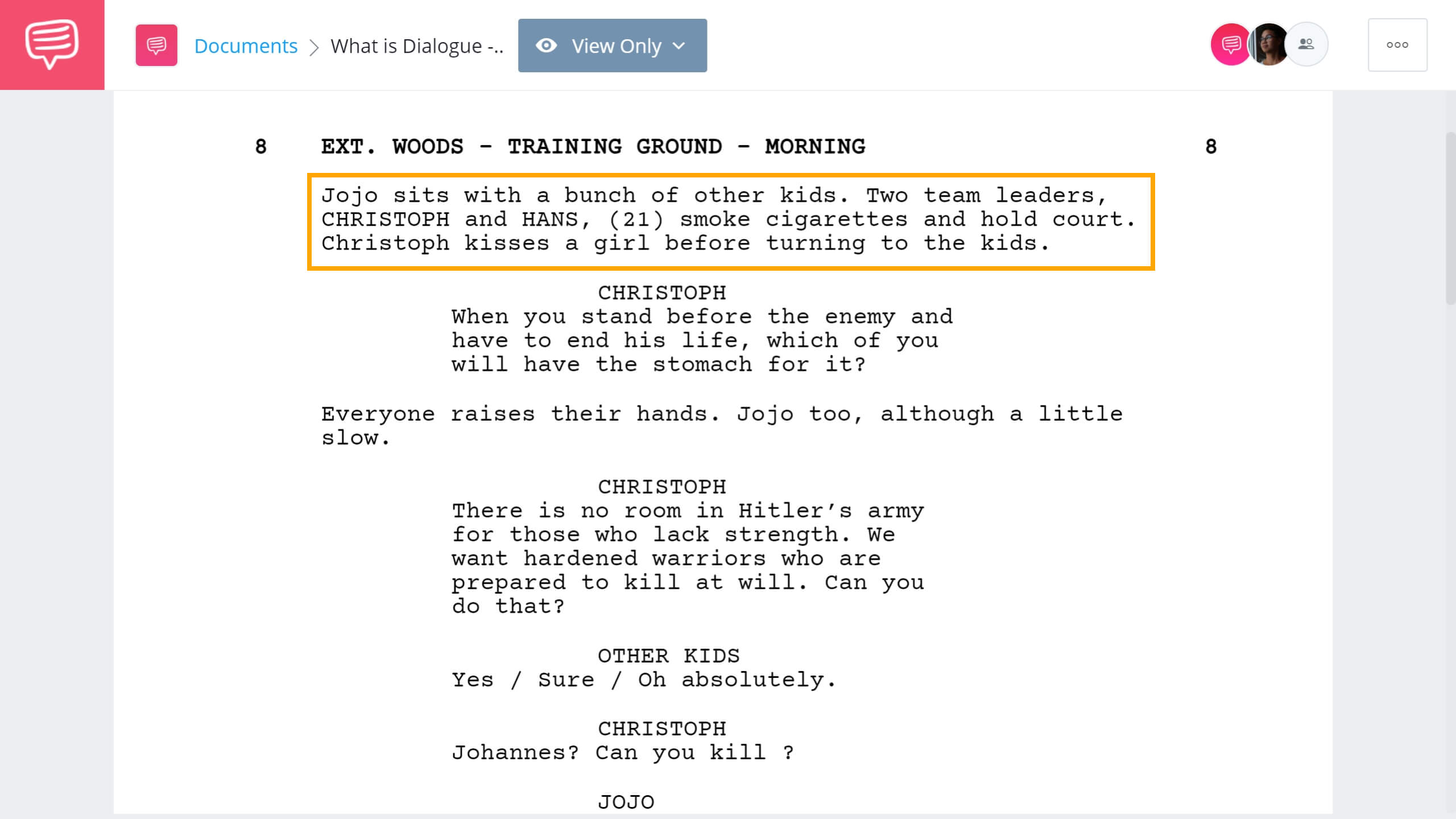

Expository Dialogue in Plays and Films

Dialogue is an especially important tool for playwrights and screenwriters, because most plays and films rely primarily on a combination of visual storytelling and dialogue to introduce the world of the story and its characters. In plays especially, the most basic information (like time of day) often needs to be conveyed through dialogue, as in the following exchange from Romeo and Juliet :

BENVOLIO Good-morrow, cousin. ROMEO Is the day so young? BENVOLIO But new struck nine. ROMEO Ay me! sad hours seem long.

Here you can see that what in prose writing might have been conveyed with a simple introductory clause like "Early the next morning..." instead has to be conveyed through dialogue.

Dialogue as a Tool for Characterization

In all forms of writing, dialogue can help writers flesh out their characters to make them more lifelike, and give readers a stronger sense of who each character is and where they come from. This can be achieved using a combination of:

- Colloquialisms and slang: Colloquialism is the use of informal words or phrases in writing or speech. This can be used in dialogue to establish that a character is from a particular time, place, or class background. Similarly, slang can be used to associate a character with a particular social group or age group.

- The form the dialogue takes: for instance, multiple books have now been written in the form of text messages between characters—a form which immediately gives readers some hint as to the demographic of the characters in the "dialogue."

- The subject matter: This is the obvious one. What characters talk about can tell readers more about them than how the characters speak. What characters talk about reveals their fears and desires, their virtues and vices, their strengths and their flaws.

For example, in Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen's narrator uses dialogue to introduce Mrs. and Mr. Bennet, their relationship, and their differing attitudes towards arranging marriages for their daughters:

"A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a year. What a fine thing for our girls!” “How so? How can it affect them?” “My dear Mr. Bennet,” replied his wife, “how can you be so tiresome! You must know that I am thinking of his marrying one of them.” “Is that his design in settling here?” “Design! Nonsense, how can you talk so! But it is very likely that he may fall in love with one of them, and therefore you must visit him as soon as he comes.”

This conversation is an example of the use of dialogue as a tool of characterization , showing readers—without explaining it directly—that Mrs. Bennet is preoccupied with arranging marriages for her daughters, and that Mr. Bennet has a deadpan sense of humor and enjoys teasing his wife.

Recognizing Dialogue in Different Types of Writing

It's important to note that how a writer uses dialogue changes depending on the form in which they're writing, so it's useful to have a basic understanding of the form dialogue takes in prose writing (i.e., fiction and nonfiction) versus the form it takes in plays and screenplays—as well as the different functions it can serve in each. We'll cover that in greater depth in the sections that follow.

Dialogue in Prose

In prose writing, which includes fiction and nonfiction, there are certain grammatical and stylistic conventions governing the use of dialogue within a text. We won't cover all of them in detail here (we'll skip over the placement of commas and such), but here are some of the basic rules for organizing dialogue in prose:

- Punctuation : Generally speaking, lines of dialogue are encased in double quotation marks "such as this," but they may also be encased in single quotation marks, 'such as this.' However, single quotation marks are generally reserved for quotations within a quotation, e.g., "Even when I dared him he said 'No way,' so I dropped the subject."

- "Where did you go?" she asked .

- I said , "Leave me alone."

- "Answer my question," said Monica , "or I'm leaving."

- Line breaks : Lines of dialogue spoken by different speakers are generally separated by line breaks. This is helpful for determining who is speaking when dialogue tags have been omitted.

Of course, some writers ignore these conventions entirely, choosing instead to italicize lines of dialogue, for example, or not to use quotation marks, leaving lines of dialogue undifferentiated from other text except for the occasional use of a dialogue tag. Writers that use nonstandard ways of conveying dialogue, however, usually do so in a consistent way, so it's not hard to figure out when someone is speaking, even if it doesn't look like normal dialogue.

Indirect vs. Direct Dialogue

In prose, there are two main ways for writers to convey the content of a conversation between two characters: directly, and indirectly. Here's an overview of the difference between direct and indirect dialogue:

- This type of dialogue can often help lend credibility or verisimilitude to dialogue in a story narrated in the first-person, since it's unlikely that a real person would remember every line of dialogue that they had overheard or spoken.

- Direct Dialogue: This is what most people are referring to when they talk about dialogue. In contrast to indirect dialogue, direct dialogue is when two people are speaking and their words are in quotations.

Of these two types of dialogue, direct dialogue is the only one that counts as dialogue strictly speaking. Indirect dialogue, by contrast, is technically considered to be part of a story's narration.

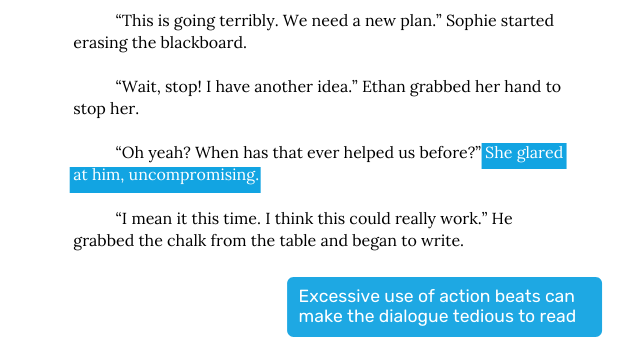

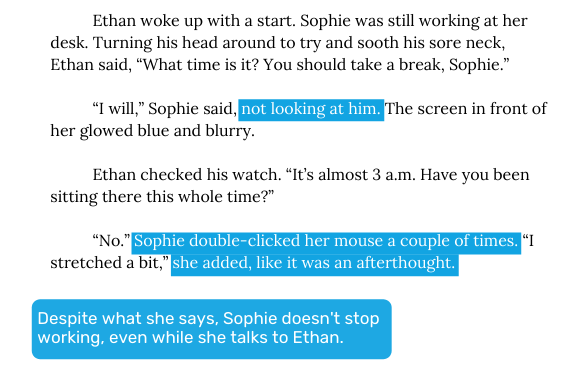

A Note on Dialogue Tags and "Said Bookisms"

It is pretty common for writers to use verbs other than "said" and "asked" to attribute a line of dialogue to a speaker in a text. For instance, it's perfectly acceptable for someone to write:

- Robert was beginning to get worried. "Hurry!" he shouted.

- "I am hurrying," Nick replied.

However, depending on how it's done, substituting different verbs for "said" can be quite distracting, since it shifts the reader's attention away from the dialogue and onto the dialogue tag itself. Here's an example where the use of non-standard dialogue tags begins to feel a bit clumsy:

- Helen was thrilled. "Nice to meet you," she beamed .

- "Nice to meet you, too," Wendy chimed .

Dialogue tags that use verbs other than the standard set (which is generally thought to include "said," "asked," "replied," and "shouted") are known as "said bookisms," and are generally ill-advised. But these "bookisms" can be easily avoided by using adverbs or simple descriptions in conjunction with one of the more standard dialogue tags, as in:

- Helen was thrilled. "Nice to meet you," she said, beaming.

- "Nice to meet you, too," Wendy replied brightly.

In the earlier version, the irregular verbs (or "said bookisms") draw attention to themselves, distracting the reader from the dialogue. By comparison, this second version reads much more smoothly.

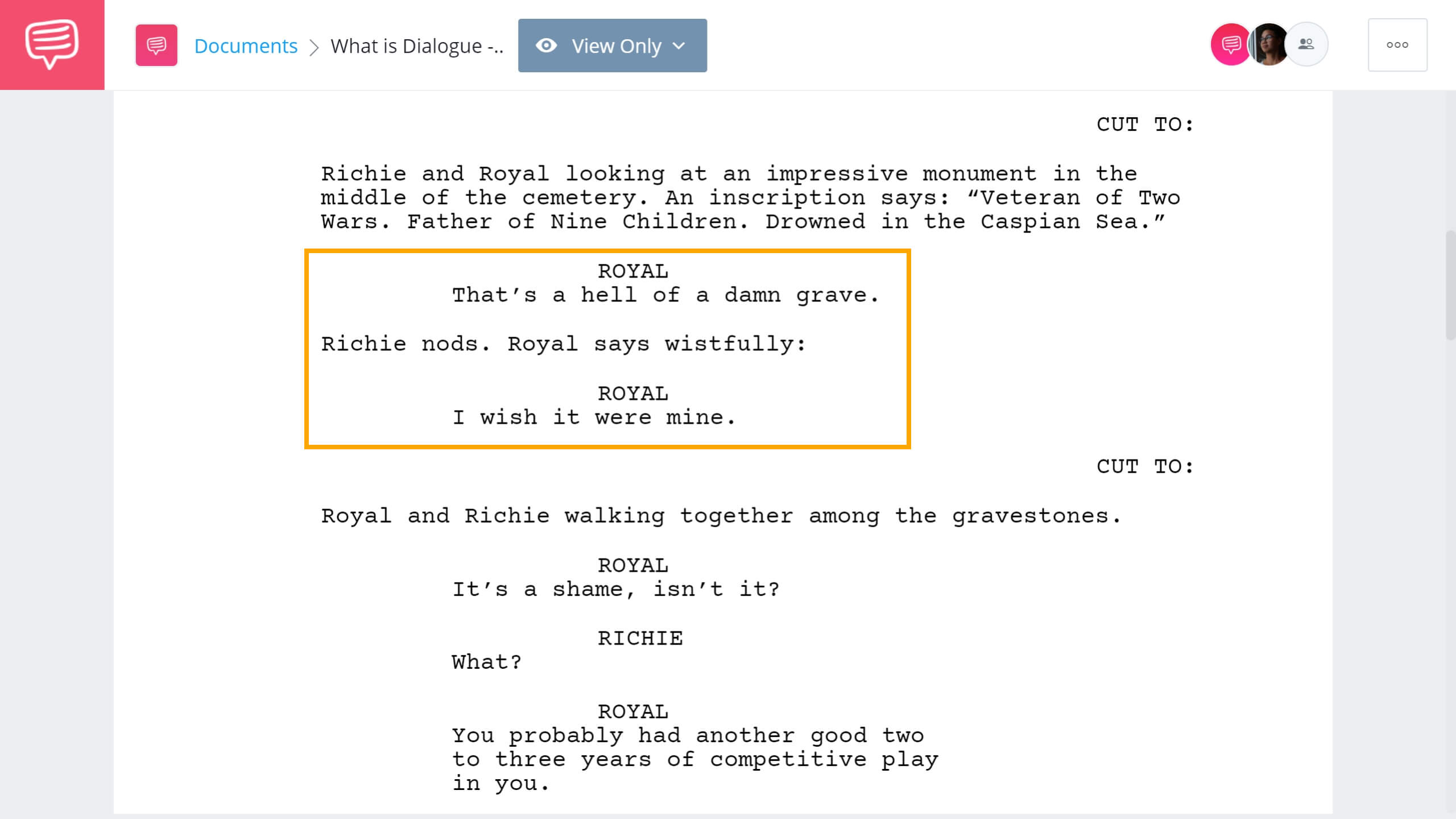

Dialogue in Plays

Dialogue in plays (and screenplays) is easy to identify because, aside from the stage directions, dialogue is the only thing a play is made of. Here's a quick rundown of the basic rules governing dialogue in plays:

- Names: Every line of dialogue is preceded by the name of the person speaking.

- Mama (outraged) : What kind of way is that to talk about your brother?

- Line breaks: Each time someone new begins speaking, just as in prose, the new line of dialogue is separated from the previous one by a line break.

Rolling all that together, here's an example of what dialogue looks like in plays, from Edward Albee's Zoo Story:

JERRY: And what is that cross street there; that one, to the right? PETER: That? Oh, that's Seventy-fourth Street. JERRY: And the zoo is around Sixty-5th Street; so, I've been walking north. PETER: [anxious to get back to his reading] Yes; it would seem so. JERRY: Good old north. PETER: [lightly, by reflex] Ha, ha.

Dialogue Examples

The following examples are taken from all types of literature, from ancient philosophical texts to contemporary novels, showing that dialogue has always been an integral feature of many different types of writing.

Dialogue in Shakespeare's Othello

In this scene from Othello , the dialogue serves an expository purpose, as the messenger enters to deliver news about the unfolding military campaign by the Ottomites against the city of Rhodes.

First Officer Here is more news. Enter a Messenger Messenger The Ottomites, reverend and gracious, Steering with due course towards the isle of Rhodes, Have there injointed them with an after fleet. First Senator Ay, so I thought. How many, as you guess? Messenger Of thirty sail: and now they do restem Their backward course, bearing with frank appearance Their purposes toward Cyprus. Signior Montano, Your trusty and most valiant servitor, With his free duty recommends you thus, And prays you to believe him.

Dialogue in Madeleine L'Engel's A Wrinkle in Time

From the classic children's book A Wrinkle in Time , here's a good example of dialogue that uses a description of a character's tone of voice instead of using unconventional verbiage to tag the line of dialogue. In other words, L'Engel doesn't follow Calvin's line of dialogue with a distracting tag like "Calvin barked." Rather, she simply states that his voice was unnaturally loud.

"I'm different, and I like being different." Calvin's voice was unnaturally loud. "Maybe I don't like being different," Meg said, "but I don't want to be like everybody else, either."

It's also worth noting that this dialogue helps characterize Calvin as a misfit who embraces his difference from others, and Meg as someone who is concerned with fitting in.

Dialogue in A Visit From the Good Squad

This passage from Jennifer Egan's A Visit From the Good Squad doesn't use dialogue tags at all. In this exchange between Alex and the unnamed woman, it's always clear who's speaking even though most of the lines of dialogue are not explicitly attributed to a speaker using tags like "he said."

Alex turns to the woman. “Where did this happen?” “In the ladies’ room. I think.” “Who else was there?” “No one.” “It was empty?” “There might have been someone, but I didn’t see her.” Alex swung around to Sasha. “You were just in the bathroom,” he said. “Did you see anyone?”

Elsewhere in the book, Egan peppers her dialogue with colloquialisms and slang to help with characterization . Here, the washed-up, alcoholic rock star Bosco says:

"I want interviews, features, you name it," Bosco went on. "Fill up my life with that shit. Let's document every fucking humiliation. This is reality, right? You don't look good anymore twenty years later, especially when you've had half your guts removed. Time's a goon, right? Isn't that the expression?"

In this passage, Bosco's speech is littered with colloquialisms, including profanity and his use of the word "guts" to describe his liver, establishing him as a character with a unique way of speaking.

Dialogue in Plato's Meno

The following passage is excerpted from a dialogue by Plato titled Meno. This text is one of the more well-known Socratic dialogues. The two characters speaking are Socrates (abbreviated, "Soc.") and Meno (abbreviated, "Men."). They're exploring the subject of virtue together.

Soc. Now, if there be any sort-of good which is distinct from knowledge, virtue may be that good; but if knowledge embraces all good, then we shall be right in think in that virtue is knowledge? Men. True. Soc. And virtue makes us good? Men. Yes. Soc. And if we are good, then we are profitable; for all good things are profitable? Men. Yes. Soc. Then virtue is profitable? Men. That is the only inference.

Indirect Dialogue in Tim O'Brien's The Things They Carried

This passage from O'Brien's The Things They Carried exemplifies the use of indirect dialogue to summarize a conversation. Here, the third-person narrator tells how Kiowa recounts the death of a soldier named Ted Lavender. Notice how the summary of the dialogue is interwoven with the rest of the narrative.

They marched until dusk, then dug their holes, and that night Kiowa kept explaining how you had to be there, how fast it was, how the poor guy just dropped like so much concrete. Boom-down, he said. Like cement.

O'Brien takes liberties in his use of quotation marks and dialogue tags, making it difficult at times to distinguish between the voices of different speakers and the voice of the narrator. In the following passage, for instance, it's unclear who is the speaker of the final sentence:

The cheekbone was gone. Oh shit, Rat Kiley said, the guy's dead. The guy's dead, he kept saying, which seemed profound—the guy's dead. I mean really.

Why Do Writers Use Dialogue in Literature?

Most writers use dialogue simply because there is more than one character in their story, and dialogue is a major part of how the plot progresses and characters interact. But in addition to the fact that dialogue is virtually a necessary component of fiction, theater, and film, writers use dialogue in their work because:

- It aids in characterization , helping to flesh out the various characters and make them feel lifelike and individual.

- It is a useful tool of exposition , since it can help convey key information abut the world of the story and its characters.

- It moves the plot along. Whether it takes the form of an argument, an admission of love, or the delivery of an important piece of news, the information conveyed through dialogue is often essential not only to readers' understanding of what's going on, but to generating the action that furthers the story's plot line.

Other Helpful Dialogue Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Dialogue: A bare-bones explanation of dialogue in writing, with one or two examples.

- The Dictionary Definition of Dialogue: A basic definition, with a bit on the etymology of the word (it comes from the Greek meaning "through discourse."

- Cinefix's video with their take on the 14 best dialogues of all time : A smart overview of what dialogue can accomplish in film.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1908 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,181 quotes across 1908 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Characterization

- Colloquialism

- Protagonist

- Foreshadowing

- Polysyndeton

- Red Herring

- End-Stopped Line

- Stream of Consciousness

- Flat Character

- Understatement

- Figurative Language

- What is Dialogue? Elements of Creative Writing

- Self Publishing Guide

People usually have a doubt what is dialogue? Dialogue is an artful expression in the literature that brings characters to life through spoken words. It serves as a medium of communication, unveiling their deepest thoughts, emotions, and motivations. With its power to advance the plot, establish relationships, and create tension, dialogue adds a dimension of reality to the narrative.

Dialogue can be written in several styles, including direct speech, indirect speech, or free indirect speech, and can be a mixture of them. It also varies in the form of the speech given by the characters, such as monologue, soliloquy, dialect, interior dialogue, and subtextual dialogue.

There are several types of dialogues that can be used in creative writing. Here are some examples:

- Direct dialogue : This is the most common type of dialogue, in which characters speak directly to each other, usually using quotation marks. For example: “I can’t believe you did that,” she said.

- Indirect dialogue : In this type of dialogue, the writer summarizes what was said instead of using direct quotes. For example: She told him that she couldn’t believe he did that.

- Interior dialogue : This is also known as internal monologue, where a character’s thoughts are revealed to the reader. For example: “I can’t believe I did that,” she thought.

- Monologue : In a monologue, one character speaks at length, usually to an audience within the story or to themselves. For example: “To be or not to be, that is the question,” said Hamlet.

- Soliloquy : Similar to a monologue, a soliloquy is a speech given by a character alone on stage, revealing their innermost thoughts and feelings. For example: “Oh Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo?” said Juliet.

- Dialect : This is a type of dialogue in which characters speak in a particular regional or cultural accent or dialect. For example: “Y’all come back now, ya hear?” said the Southern farmer.

- Subtextual dialogue : This type of dialogue implies meaning beneath the surface and often has a hidden agenda. For example: “I’m sure you didn’t mean to hurt my feelings,” she said, with a sharp edge to her voice.

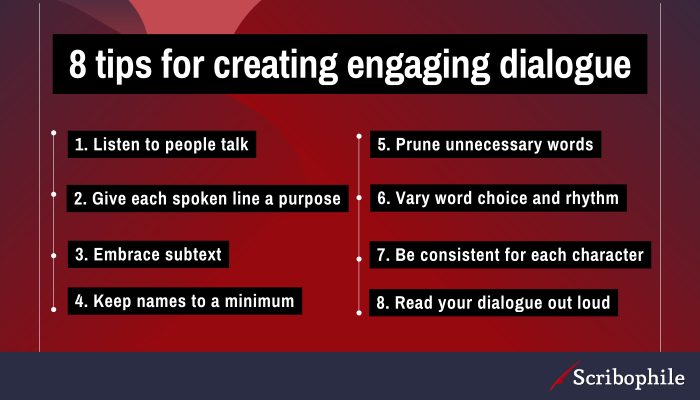

Writing effective dialogue is crucial to creating engaging and memorable characters and stories. Here are some tips for writing effective dialogue:

- Make it sound natural : Dialogue should sound like a real conversation, with pauses, interruptions, and changes in tone and tempo. Use contractions, sentence fragments, and filler words to make it sound natural.

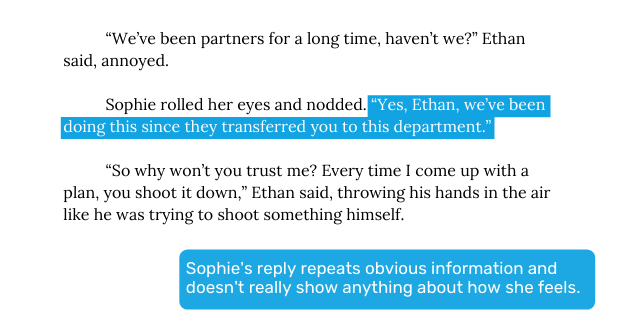

- Show, don’t tell : Use dialogue to show the reader what is happening and how the characters are feeling instead of telling them. For example, instead of saying “he was angry,” show the character’s anger through their words and actions.

- Use subtext : Effective dialogue often has a deeper meaning beneath the surface. Use subtext to create tension and conflict between characters and to reveal their true motivations and emotions.

- Avoid exposition : Dialogue should not be used as a way to provide backstory or exposition. Instead, find other ways to reveal important information to the reader.

- Use tags sparingly : Dialogue tags like “he said” or “she replied” can become repetitive and distracting. Use them sparingly and opt for actions or gestures to indicate who is speaking.

- Vary sentence length and structure : Mix up the length and structure of your dialogue to keep it interesting and avoid monotony.

- Read it out loud : Reading your dialogue out loud can help you identify areas that sound awkward or unnatural and make necessary revisions.

By following these tips, you can write dialogue that is engaging, and realistic, and advances the plot and characterization of your story. Here are a few examples of well-written dialogues:

"Here's looking at you, kid." - Casablanca (1942)

This iconic line, spoken by Humphrey Bogart’s character Rick Blaine to Ingrid Bergman’s character Ilsa Lund in the classic film Casablanca, is an example of how dialogue can convey emotion and meaning through simple, memorable phrases. The line has become a cultural touchstone, representing the romantic tension between the two characters and the bittersweet nostalgia of the film’s wartime setting.

"You can't handle the truth!" - A Few Good Men (1992)

This famous line, spoken by Jack Nicholson’s character Colonel Nathan Jessup in the courtroom drama A Few Good Men, is an example of how dialogue can create tension and conflict. The line represents the character’s stubborn refusal to admit wrongdoing, and the confrontation that follows becomes a pivotal moment in the film’s plot.

"I'm gonna make him an offer he can't refuse." - The Godfather (1972)

This line, spoken by Renee Zellweger’s character Dorothy Boyd to Tom Cruise’s character Jerry Maguire in the romantic comedy-drama Jerry Maguire, is an example of how dialogue can create emotional connection and vulnerability. The line represents the character’s openness and willingness to take a chance on love, and it becomes a turning point in the film’s central relationship.

"You had me at hello." - Jerry Maguire (1996)

Learn what is BookTube? Popular types of content found on BookTube.

In conclusion, these examples show how effective dialogue can contribute to a film or story’s themes, tone, and characterization. They demonstrate the importance of using dialogue to convey emotion, meaning, and conflict, and how memorable phrases can become cultural touchstones.

Publish your book for free with BlueRoseONE and become a bestselling author . Don’t let your dream of becoming an author fade away, grab the opportunity now and publish your book – be it fiction, non fiction, poetry or more.

- About The Author

- Latest Posts

Mansi Chauhan

You May Also Like

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Definition of Dialogue

Plato initially used the term “dialogue” to describe Socratic dialectic works. These works feature dialogues with Socrates, and they were intended to communicate philosophical ideas. As a current literary device, dialogue refers to spoken lines by characters in a story that serve many functions such as adding context to a narrative , establishing voice and tone , or setting forth conflict .

Writers utilize dialogue as a means to demonstrate communication between two characters. Most dialogue is spoken aloud in a narrative, though there are exceptions in terms of inner dialogue. Writers denote dialogue by the use of quotation marks (indicating spoken words) and dialogue tags (words such as “said” or “asked” indicating which character in the narrative is speaking). For example, Charles Dickens utilizes dialogue, quotation marks, and dialogue tags effectively in his work Great Expectations :

“Oh! Don’t cut my throat, sir,” I pleaded in terror. “Pray don’t do it, sir.” “Tell us your name!” said the man. “Quick!” “Pip, sir.” “Once more,” said the man, staring at me. “Give it mouth!”

The reader is able to understand which words are spoken and by which characters. This passage demonstrates the way dialogue is used to convey the thoughts and actions of characters in addition to creating dramatic conflict that moves the plot along.

Examples of Why Writers Use Dialogue

Dialogue, when used effectively in a literary work, is an important literary device. Dialogue allows writers to pause in their third-person description of a story’s action, characters, setting, etc., which can often feel detached to the reader if prolonged. Instead, when characters are “speaking” in first-person in a narrative, the story can become more dynamic.

Here are some examples of why writers use dialogue in literary works:

- reveal conflict in a story

- move story forward

- present different points of view

- provide exposition , background, or contextual information

- efficient means of conveying aspects and traits of characters

- convey subtext (inner feelings and intentions of a character beyond their surface words of communication)

- establish deeper meaning and understanding of a story for the reader

- set character’s voice, point of view , and patterns of expression

- allow characters to engage in conflict

- create authenticity for reader

Famous Lines of Dialogue from Well-Known Movies

Well-known movies often feature memorable lines of dialogue that allow the audience to connect with characters and have a greater understanding of the plot as well as enjoyment of the film. Here are some famous lines of dialogue from well-known movies:

- Casablanca: “But what about us?” “We’ll always have Paris.”

- The Wizard of Oz: “Lions? And Tigers? And Bears?” “Oh my!”

- Star Wars (A New Hope): “He’s almost in range.” “That’s no moon; it’s a space station.”

- Love Story: “Jenny, I’m sorry.” “Don’t. Love means never having to say you’re sorry.”

- No Country for Old Men: “Look, I need to know what I stand to win.” “Everything.”

- Forrest Gump: “I thought I’d try out my sea legs.” “But you ain’t got no legs, Lieutenant Dan.”

- Toy Story: “Buzz, you’re flying!” “This isn’t flying; this is falling with style .”

Writing Effective Dialogue

Writers often find it difficult to utilize dialogue as a literary device. This is understandable considering that most of the daily dialogue exchanged between people in reality is often insignificant. In addition to being meaningful, it’s also difficult to write dialogue that “sounds” authentic to a reader. This poses a danger of taking a reader’s attention away from the story due to distracting dialogue.

However, writers shouldn’t avoid dialogue. This literary device, when written well, accomplishes many things for the narrative overall. Dialogue that sounds natural, authentic, and lifelike will advance the plot of a story, establish characters, and provide exposition. Therefore, writers should understand their purpose in using this literary device effectively as a means of creating a compelling story and entertaining experience for the reader.

Examples of Dialogue in Literature

As a literary device, dialogue can be utilized in almost any form of literature. This allows readers to better understand characters, plot, and even the theme of a literary work. Here are some examples of dialogue in well-known literature:

Example 1: Up-Hill (Christina Rossetti)

Does the road wind up-hill all the way? Yes, to the very end. Will the day’s journey take the whole long day? From morn to night , my friend . But is there for the night a resting-place? A roof for when the slow dark hours begin. May not the darkness hide it from my face? You cannot miss that inn. Shall I meet other wayfarers at night? Those who have gone before. Then must I knock, or call when just in sight? They will not keep you standing at that door. Shall I find comfort, travel-sore and weak? Of labour you shall find the sum. Will there be beds for me and all who seek? Yea, beds for all who come.

It can be rare in poetry to find dialogue as a literary device due to a poem ’s typical nature of not featuring characters. However, in Rossetti’s literary work, the structure of the poem is in dialogue form. The poet asks questions of an unknown speaker and receives answers in return. This dialogue structure is effective in the poem in that the poet’s questions can be understood in a literal as well as symbolic manner. The poet is, on the literal surface, asking about the direction of the road, how long the journey will take, and what they may find once they reach the top of the hill. The unknown speaker replies with logical answers to these questions at a literal level.

However, Rossetti’s poem can also be interpreted as symbolic dialogue. The poet’s questions can be understood as those that humans would ask about the path of life and expectations in death and the afterlife. In this way, the dialogue, or conversation, is between the poet who represents human curiosity and an unknown speaker with the authority to reassure and confirm “answers” to these symbolic questions. Readers are left to wonder if the symbolic dialogue in the poem is between the poet and perhaps God.

Example 2: The Importance of Being Earnest (Oscar Wilde)

ALGERNON. I’m afraid I’m not that. That is why I want you to reform me. You might make that your mission, if you don’t mind, cousin Cecily. CECILY. I’m afraid I’ve no time, this afternoon. ALGERNON. Well, would you mind my reforming myself this afternoon? CECILY. It is rather Quixotic of you. But I think you should try. ALGERNON. I will. I feel better already. CECILY. You are looking a little worse. ALGERNON. That is because I am hungry. CECILY. How thoughtless of me. I should have remembered that when one is going to lead an entirely new life, one requires regular and wholesome meals. Won’t you come in ?

Since plays are dramatic literary works to be performed, they often rely almost exclusively on dialogue between characters as a means of presenting the narrative. When plays are performed on stage, the audience can see and hear which character is speaking in addition to their physical attitude , vocal tone, inflection, etc. When reading a dramatic work such as Wilde’s famous play , the reader understands who is speaking as a result of the character’s name associated with specific lines of dialogue.

Wilde was known for using dialogue as a literary device to create witty conversations between his characters for the audience’s entertainment. However, Wilde’s word play and unexpected exchanges between characters often didn’t serve to create much dramatic action in terms of plot in his literary works. Instead, Wilde’s use of dialogue and patterns of expression convey the voice and traits of his characters in addition to setting forth some dramatic conflict in the narrative.

Example 3: Hills Like White Elephants (Ernest Hemingway)

“And you think then we’ll be all right and be happy.” “I know we will. You don’t have to be afraid. I’ve known lots of people that have done it.” “So have I,” said the girl. “And afterward they were all so happy.” “Well,” the man said, “if you don’t want to you don’t have to. I wouldn’t have you do it if you didn’t want to. But I know it’s perfectly simple.” “And you really want to?” ” I think it’s the best thing to do. But I don’t want you to do it if you don’t really want to.” “And if I do it you’ll be happy and things will be like they were and you’ll love me?” “ I love you now . You know I love you.”

In this short story , Hemingway utilizes dialogue as a literary device to allow his characters to “talk” about a subject , though the actual subject itself is not directly named or expressed by either the man or the girl. This poses a challenge to readers in terms of determining what the couple is actually discussing. This is an effective strategy considering the couple is discussing whether the girl should terminate her pregnancy–a subject that would have been taboo to mention outright. Instead, Hemingway constructs dialogue such that the reader must interpret the difference between what the two characters are saying and what they truly mean.

Therefore, to understand the story, readers must pay close attention not to what is being said but who is speaking and the manner in which they speak. The dialogue becomes much more about the nature of the characters than the words they are speaking. This allows the reader to notice subtleties such as the plaintive tone of the girl, her ambiguous feelings, and her need for reassurance. In turn, the reader is able to notice the pressuring and insistent tone of the man. Hemingway’s use of dialogue, in a sense, offers a story in which the words “tell” less about the narrative than the attitudes of the characters do.

Post navigation

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing community!

How to Write Dialogue: Rules, Examples, and 8 Tips for Engaging Dialogue

by Fija Callaghan

You’ll often hear fiction writers talking about “character-driven stories”—stories where the strengths, weaknesses, and aspirations of the central cast of characters stay with us long after the book is closed. But what drives character, and how do we create characters that leave long-lasting impressions?

The answer lies in dialogue : the device used by our characters to communicate with each other. Powerful dialogue can elevate a story and subtly reveal important information, but poorly written dialogue can send your work straight to the slush bin. Let’s look at what dialogue is in writing, how to properly format dialogue, and how to make your characters’ dialogue the best it can be.

What is dialogue in a story?

Dialogue is the verbal exchange between two or more characters. In most fiction, the exchange is in the form of a spoken conversation. However, conversations in a story can also be things like letters, text messages, telepathy, or even sign language. Any moment where two characters speak or connect with each other through their choice of words, they’re engaging in dialogue.

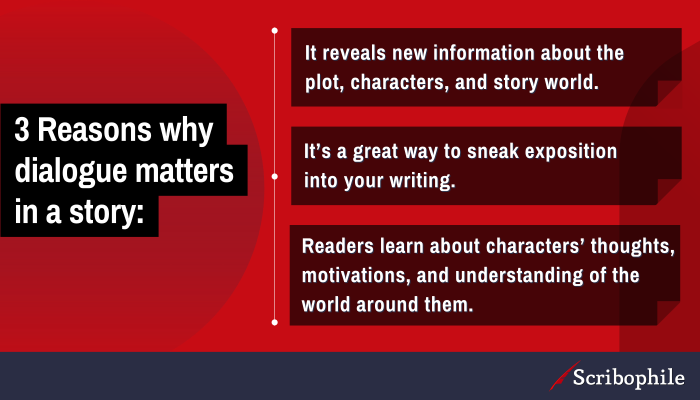

Why does dialogue matter in a story?

We use dialogue in a story to reveal new information about the plot, characters, and story world. Great dialogue is essential to character development and helps move the plot forward in a story.

Writing good dialogue is a great way to sneak exposition into your story without stating it overtly to the reader; you can also use tools like dialect and diction in your dialogue to communicate more detail about your characters.

Through a character’s dialogue, we can learn about their motivations, relationships, and understanding of the world around them.

A character won’t always say what they mean (more on dialogue subtext below), but everything they say will serve some larger purpose in the story. If your dialogue is well-written, the reader will absorb this information without even realizing it. If your dialogue is clunky, however, it will stand out and pull your reader away from your story.

Rules for writing dialogue

Before we get into how to make your dialogue realistic and engaging, let’s make sure you’ve got the basics down: how to properly format dialogue in a story. We’ll look at how to punctuate dialogue, how to write dialogue correctly when using a question mark or exclamation point, and some helpful dialogue writing examples.

Here are the need-to-know rules for formatting dialogue in writing.

Enclose lines of dialogue in double quotation marks

This is the most essential rule in basic dialogue punctuation. When you write dialogue in North American English, a spoken line will have a set of double quotation marks around it. Here’s a simple dialogue example:

“Were you at the party last night?”

Any punctuation such as periods, question marks, and exclamation marks will also go inside the quotation marks. The quotation marks give a visual clue to the reader that this line is spoken out loud.

In European or British English, however, you’ll often see single quotation marks being used instead of double quotation marks. All the other rules stay the same.

Enclose nested dialogue in single quotation marks

Nested dialogue is when one line of dialogue happens inside another line of dialogue—when someone is verbally quoting someone else. In North American English, you’d use single quotation marks to identify where the new dialogue line starts and stops, like this:

“And then, do you know what he said to me? Right to my face, he said, ‘I stayed home all night.’ As if I didn’t even see him.”

The double and single quotation marks give the reader clues as to who’s speaking. In European or British English, the quotation marks would be reversed; you’d use single quotation marks on the outside, and double quotation marks on the inside.

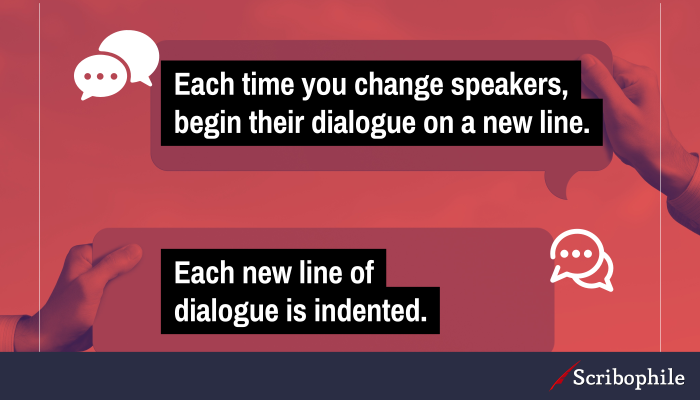

Every speaker gets a new paragraph

Every time you switch to a new speaker, you end the line where it is and start a new line. Here are some dialogue examples to show you how it looks:

“Were you at the party last night?” “No, I stayed home all night.”

The same is true if the new “speaker” is only in focus because of their action. You can think of the paragraphs like camera angles, each one focusing on a different person:

“Were you at the party last night?” “No, I stayed home all night.” She raised a single, threatening eyebrow. “Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and watched Netflix instead.”

If you kept the action on the same line as the dialogue, it would get confusing and make it look like she was the one saying it. Giving each character a new paragraph keeps the speakers clear and distinct.

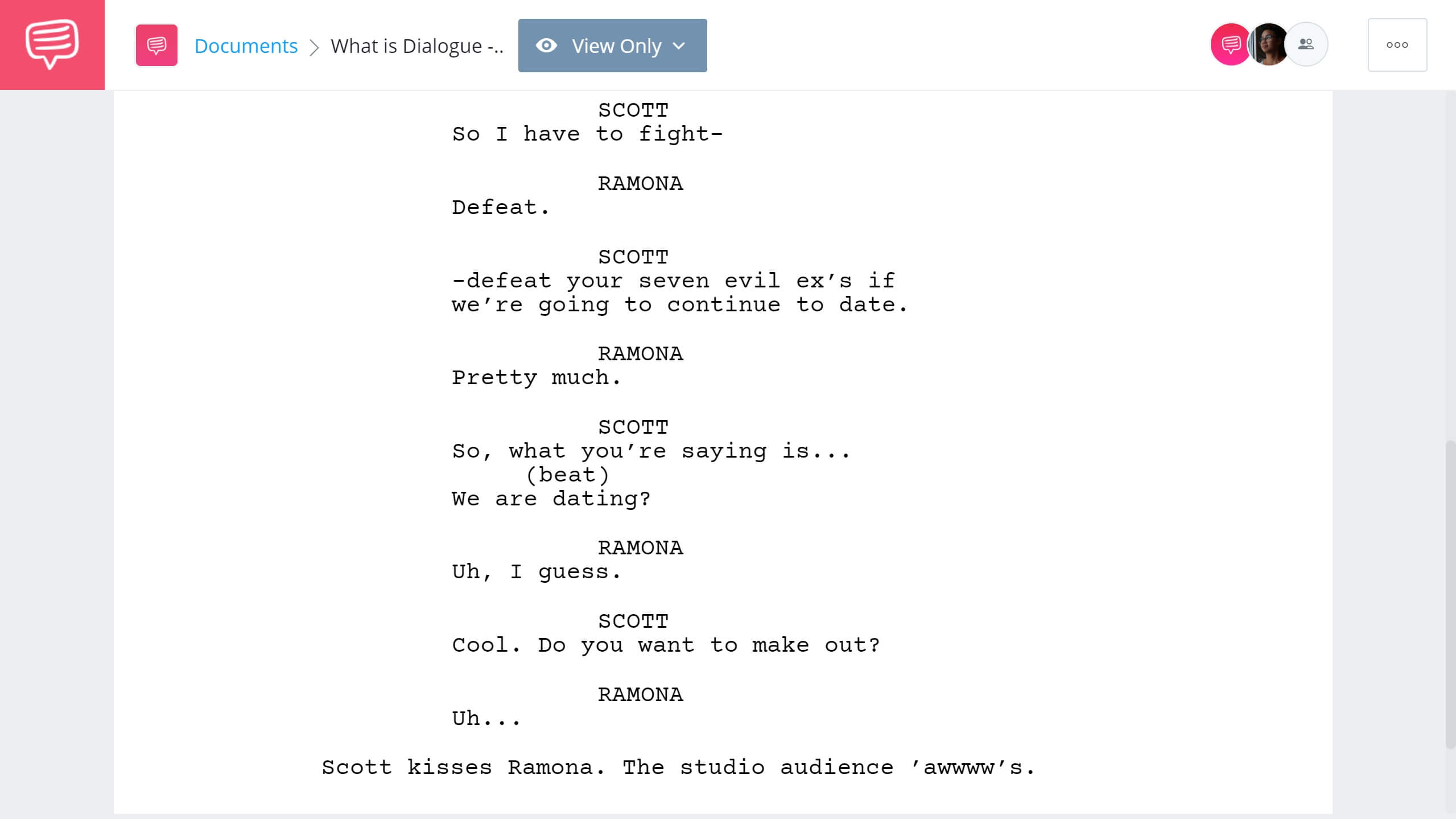

Use em-dashes when dialogue gets cut short

If your character begins to speak but is interrupted, you’ll break off their line of dialogue with an em-dash, like this:

“Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and—” “Is that really what happened?”

Be careful with this one, because many word processors will treat your em-dash like the beginning of a new sentence and attach your closing quotation marks backwards:

“Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and—“

You may need to keep an eye out and adjust as you go along.

In this dialogue example, the new speaker doesn’t lead with an em-dash; they just start speaking like normal. The only time you’ll ever open a line of dialogue with an em-dash is if the speaker who’s been cut off continues with what they were saying:

“Yeah, I wasn’t feeling that well, so I just stayed in and—” “Is that really what happened?” “—watched Netflix instead. Yes, that’s what happened.”

This shows the reader that there’s actually only one line of dialogue, but it’s been cut in the middle by another speaker.

Each line of dialogue is indented

Every time you give your speaker a new paragraph, it’s indented from the left-hand side. Many word processors will do this automatically. The only exception is if your dialogue is opening your story or a new section of your story, such as a chapter; these will always start at the far left margin of the page, whether they’re dialogue or narration.

Long speeches don’t use use closing quotation marks until the end

Most writers favor shorter lines of dialogue in their writing, but sometimes you might need to give your character a longer one—for instance, if the character speaking is giving a speech or telling a story. In these cases, you might choose to break up their speech into shorter paragraphs the way you would if you were writing regular narrative.

However, here the punctuation gets a bit weird. You’ll begin the character’s dialogue with a double quotation mark, like normal. But you won’t use a double quotation mark at the end of the paragraph, because they haven’t finished speaking yet. But! You’ll use another opening quotation mark at the beginning of the subsequent paragraph. This means that you may use several opening double quotation marks for your character’s speech, but only ever one closing quotation mark.

If your character is telling a story that involves people talking, remember to use single quotation marks for your dialogue-within-dialogue as we looked at above.

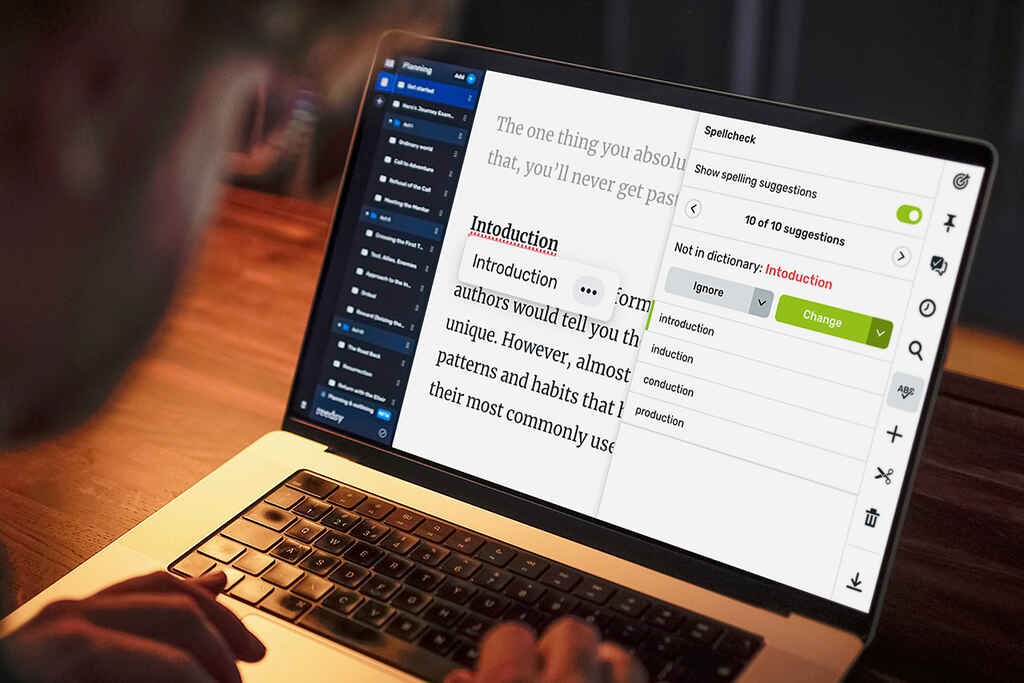

Sometimes these dialogue formatting rules are easier to catch later on, during the editing process. When you’re writing, worry less about using the exact dialogue punctuation and more about writing great dialogue that supports your character development and moves the story forward.

How to use dialogue tags

Dialogue tags help identify the speaker. They’re especially important if you have a group of people all talking together, and it can get pretty confusing for the reader trying to keep everybody straight. If you’re using a speech tag after your line of dialogue—he said, she said, and so forth—you’ll end your sentence with a comma, like this:

“No, I stayed home all night,” he said.

But if you’re using an action to identify the person speaking instead, you’ll punctuate the sentence like normal and start a new sentence to describe the action taking place:

“No, I stayed home all night.” He looked down at his feet.

The dialogue tags and action tags always follow in the same paragraph. When you move your story lens to a new person, you’ll switch to a new paragraph. Each line where a new person speaks propels the story forward.

When to use capitals in dialogue tags

You may have noticed in the two examples above that one dialogue tag begins with a lowercase letter, and one—which is technically called an action tag—begins with a capital letter. Confusing? The rules are simple once you get a little practice.

When you use a dialogue tag like “he said,” “she said,” “he whispered,” or “she shouted,” you’re using these as modifiers to your sentence—dressing it up with a little clarity. They’re an extension of the sentence the person was speaking. That’s why you separate them with a comma and keep going.

With an action tag , you’re ending one sentence and beginning a whole new one. Each sentence represents two distinct moments in the story. That’s why you end the first sentence with a period, and then open the next one with a capital letter.

If you’re not sure, try reading them out loud:

“No, I stayed home all night,” he said. “No, I stayed home all night.” He looked down at his feet.

Since you can’t hear quotation marks out loud, the way you say them will show you if they’re one sentence or two. In the first example, you can hear how the sentence keeps going after the dialogue ends. In the second example, you can hear how one sentence comes to a full stop and another one begins.

But what if your dialogue tag comes before the dialogue, instead of after? In this case, the dialogue is always capitalized because the speaker is beginning a new sentence:

He said, “No, I stayed home all night.” He looked down at his feet. “No, I stayed home all night.”

You’ll still use a comma after the dialogue tag and a period after the action tag, just like if you’d separate them if you were putting your tag at the end.

If you’re not sure, ask yourself if your leading tag sounds like a full sentence or a partial sentence. If it sounds like a partial sentence, it gets a comma. If it reads like a full sentence that stands on its own, it gets a period.

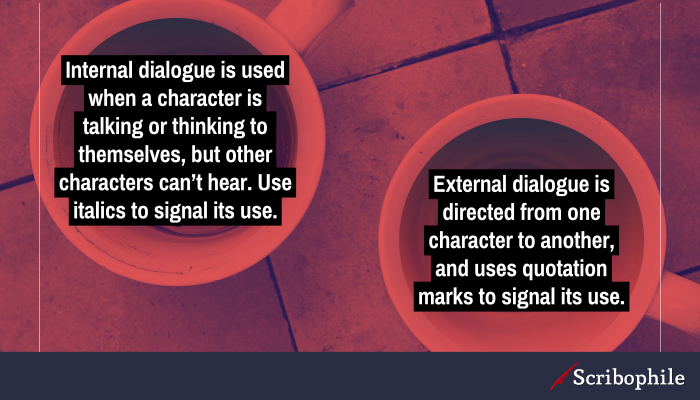

External vs. internal dialogue

All of the dialogue we’ve looked at so far is external dialogue, which is directed from one character to another. The other type of dialogue is internal dialogue, or inner dialogue, where a character is talking to themselves. You’ll use this when you want to show what a character is thinking, but other characters can’t hear.

Usually, internal dialogue will be written in italics to distinguish it from the rest of the text. That shows the reader that the line is happening inside the character’s head. For example:

It’s not a big deal, she thought. It’s just a new school. It’ll be fine. I’ll be fine.

Here you can see that the dialogue tag is used in the same way, just as if it was a line of external dialogue. However, “she thought” is written in regular text because it’s not a part of what the character is thinking. This helps keep everything clear for the reader.

In your story, you can play with using contrasting internal and external dialogue to show that what your characters say isn’t always what they mean. You may also choose to use this internal dialogue formatting if you’re writing dialogue between two or more characters that isn’t spoken out loud—for instance, telepathically or by sign language.

8 tips for creating engaging dialogue in a story

Now that you’ve mastered the mechanics of how to write dialogue, let’s look at how to create convincing, compelling dialogue that will elevate your story.

1. Listen to people talk

To write convincingly about people, you’ll first need to know something about them. The work of great writers is often characterized by their insight into humanity; you read them and think, “Yes, this is exactly what people are like.” You can begin accumulating your own insight by listening to what real people say to each other.

You can go to any public place where people are likely to gather and converse: cafés, art galleries, political events, dimly lit pubs, bookshops. Record snippets of conversation, pay attention to how people’s voices change as they move from speaking to one person to another, try to imagine what it is they’re not saying, the words simmering just under the surface.

By listening to stories unfold in real time, you’ll have a better idea of how to recreate them in your writing—and inspiration for some new stories, too.

2. Give each spoken line a purpose

Here is something that actors have drilled into their heads from their first day at drama school, and writers would do well to remember it too: every single line of dialogue has a hidden motivation. Every time your character speaks, they’re trying to achieve something, either overtly or covertly.

Small talk is rare in fiction, because it doesn’t advance the plot or reveal something about your characters. The exception is when your characters are using their small talk for a specific purpose, such as to put off talking about the real issue, to disarm someone, or to pretend they belong somewhere they don’t.

When writing your own dialogue, ask yourself what the line accomplishes in the story. If you come up blank, it probably doesn’t need to be there. Words need to earn their place on the page.

3. Embrace subtext

In real life, we rarely say exactly what we really mean. The reality of polite society is that we’ve evolved to speak in circles around our true intentions, afraid of the consequences of speaking our mind. Your characters will be no different. If your protagonist is trying to tell their best friend they’re in love with them, for instance, they’ll come up with about fifty different ways to say it before speaking the deceptively simple words themselves.

To write better dialogue, try exploring different ways of moving your characters around what’s really being said, layering text and subtext side by side. The reader will love picking apart the conversation between your characters and deducing what’s really happening underneath (incidentally, this is also the place where fan fiction is born).

4. Keep names to a minimum

You may notice that on television, in moments of great upheaval, the characters will communicate exactly how important the moment is by saying each other’s names in dramatic bursts of anger/passion/fear/heartbreak/shock. In real life, we say each other’s names very rarely; saying someone’s name out loud can actually be a surprisingly intimate experience.

Names may be a necessary evil right at the beginning of your story so your reader knows who’s who, but after you’ve established your cast, try to include names in dialogue only when it makes sense to do so. If you’re not sure, try reading the dialogue out loud to see if it sounds like something someone would actually say (we’ll talk more about reading out loud below).

5. Prune unnecessary words

This is one area where reality and story differ. In life, dialogue is full of filler words: “Um, uh, well, so yeah, then I was like, erm, huh?” You may have noticed this when you practiced listening to dialogue, above. We won’t say there’s never a place for these words in fiction, but like all words in storytelling, they need to earn their place. You might find filler words an effective tool for showing something about one particular character, or about one particular moment, but you’ll generally find that you use them a lot less than people really do in everyday speech.

When you’re reviewing your characters’ dialogue, remember the hint above: each line needs a purpose. It’s the same for each word. Keep only the ones that contribute something to the story.

6. Vary word choices and rhythms

The greatest dialogue examples in writing use distinctive character voices; each character sounds a little bit different, because they have their own personality.

This can be tricky to master, but an easy way to get started is to look at the word choice and rhythm for each character. You might have one character use longer words and run-on sentences, while another uses smaller words and simple, single-clause sentences. You might have one lean on colloquial regional dialect, where another sounds more cosmopolitan. Play around with different ways to develop characters and give each one their own voice.

7. Be consistent for each character

When you do find a solid, believable voice for your character, make sure that it stays consistent throughout your entire story. It’s easy to set a story aside for a while, then return to it and forget some of the work you did in distinguishing your characters’ dialogue. You might find it helpful to write down some notes about the way each character speaks so you can refer back to it later.

The exception, of course, is if your character’s speech pattern goes through a transformation over the course of the story, like Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady . In this case, you can use your character’s distinctive voice to communicate a major change. But as with all things in writing, make sure that it comes from intention and not from forgetfulness.

8. Read your dialogue out loud

After you’ve written a scene between two or more characters, you can take the dialogue for a trial run by speaking it out loud. Ask yourself, does the dialogue sound realistic? Are there any moments where it drags or feels forced? Does the voice feel natural for each character? You’ll often find there are snags you miss in your writing that only become apparent when read out loud. Bonus: this is great practice for when you become rich and famous and do live readings at bookshops.

3 mistakes to avoid when writing dialogue

Easy, right? But there are also a few pitfalls that new writers often encounter when writing dialogue that can drag down an otherwise compelling story. Here are the things to watch out for when crafting your story dialogue.

1. Too much exposition

Exposition is one of the more demanding literary devices , and one of the ones most likely to trip up new writers. Dialogue is a good place to sneak in some information about your story—but subtlety is essential. This is one place where the adage “show, don’t tell” really shines.

Consider these dialogue examples:

“How is she, Doctor?” “Well Mr. Stuffington, I don’t have to remind you that your daughter, the sole heiress to your estate and currently engaged to the Baron of Flippingshire, has suffered a grievous injury when she fell from her horse last Sunday. We don’t need to discuss right now whether or not you think her jealous maid was responsible; what matters is your daughter’s well being. As to your question, I’m afraid it’s very unlikely that she’ll ever walk again.” Can’t you just feel your arm aching to throw the poor book across the room? There’s a lot of important information here, but you can find subtler ways to work it into your story. Let’s try again: “How is she, Doctor?” “Well Mr. Stuffington, your daughter took quite a blow from that horse—worse than we initially thought. I’m afraid it’s very unlikely that she’ll ever walk again.” “And what am I supposed to say to Flippingshire?” “The Baron? I suppose you’ll have to tell him that his future wife has lost the use of her legs.”

And so forth. To create good dialogue exposition, look for little ways to work in the details of your story, instead of piling it up in one great clump.

2. Too much small talk

We looked at how each line of dialogue needs a specific purpose above. Very often small talk in a story happens because the writer doesn’t know what the scene is about. Small talk doesn’t move the scene along unless it’s there for a reason. If you’re not sure, ask yourself what each character wants in this moment.

For example, imagine you’re in an office, and two characters are talking by the water cooler. How was your weekend, what did you think of the game, how’s your wife doing, are those new shoes, etc etc. Can’t you just feel the reader’s will to live slipping away?

But what about this: your characters are talking by the water cooler—Character A and Character B. Character A knows that his friend is inside Character B’s office looking for evidence of corporate espionage, so A is doing everything he can to stop B from going in. How was your weekend, what did you think of the game, how’s your wife doing, are those new shoes, literally anything just to keep him talking. Suddenly these benign little phrases have a purpose.

If you find your characters slipping into small talk, double check that it’s there for a purpose, and not just a crutch to keep you from moving forward in your scene. When writing dialogue, Make each line of dialogue earn its place.

3. Too much repetition

Variation is the spice of a good story. To keep your readers engaged, avoid using the same sentence structure and the same dialogue tags over and over again. Using “he said” and “she said” is effective and clear cut, but only for about three beats. After that, try switching to an action tag instead or letting the line of dialogue stand on its own.

You can also experiment with varying the length of your sentences or groupings of sentences. By changing up the rhythm of your story regularly, you’ll keep it feeling fresh and present for the reader.

Effective dialogue examples from literature

With all of these tips and tricks in mind, let’s look at how other writers have used good dialogue to elevate their stories.

Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine , by Gail Honeyman

“I’m going to pick up a carryout and head round to my mate Andy’s. A few of us usually hang out there on Saturday nights, fire up the playstation, have a smoke and a few beers.” “Sounds utterly delightful,” I said. “What about you?” he asked. I was going home, of course, to watch a television program or read a book. What else would I be doing? “I shall return to my flat,” I said. “I think there might be a documentary about komodo dragons on BBC4 later this evening.”

In this dialogue example, the author gives her characters two very distinctive voices. From just a few words we can begin to see these people very clearly in our minds—and with this distinction comes the tension that drives the story. Dialogue is an excellent place to show your character dynamics using speech patterns and word choices.

Pride and Prejudice , by Jane Austen

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?” Mr. Bennet replied that he had not. “But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.” Mr. Bennet made no answer. “Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently. “You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.” This was invitation enough. “Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

In this famous dialogue example, the author illustrates the relationship between these two characters clearly and succinctly. Their dialogue shows Mr. B’s stalwart, tolerant love for his wife and Mrs. B’s excitement and propensity for gossip. The author shows us everything we need to know about these people in just a few lines.

Dinner in Donnybrook , by Maeve Binchy

“Look, I thought you ought to know, we’ve had a very odd letter from Carmel.” “A what… from Carmel?” “A letter. Yes, I know it’s sort of out of character, I thought maybe something might be wrong and you’d need to know…” “Yes, well, what did she say, what’s the matter with her?” “Nothing, that’s the problem, she’s inviting us to dinner.” “To dinner?” “Yes, it’s sort of funny, isn’t it? As if she wasn’t well or something. I thought you should know in case she got in touch with you.” “Did you really drag me all the way down here, third years are at the top of the house you know, I thought the house had burned down! God, wait till I come home to you. I’ll murder you.” “The dinner’s in a month’s time, and she says she’s invited Ruth O’Donnell.” “Oh, Jesus Christ.”

This dialogue example is a telephone conversation between two people. The lack of dialogue tags or action tags allows the words to come to the forefront and immerses us in their back-and-forth conversation. Even though there are no tags to indicate the speakers, the language is simple and straightforward enough that the reader always knows who’s talking. Through this conversation the author slowly builds the tension from the benign to the catastrophic within a domestic setting.

Compelling dialogue is the key to a good story

A writer has a lot riding on their characters’ dialogue, and learning how to write dialogue is a critical skill for any writer. When done well, it can leaves a lasting impact on the reader. But when dialogue is clumsy and awkward, it can drag your story down and make your reader feel like they’re wasting their time.

But if you keep these tips in mind, listen to dialogue in your everyday life, and practice , you’ll be sure to create realistic dialogue that brings your story to life.

Get feedback on your writing today!

Scribophile is a community of hundreds of thousands of writers from all over the world. Meet beta readers, get feedback on your writing, and become a better writer!

Join now for free

Related articles

What is Dialect in Literature? Definition and Examples

Writing Effective Dialogue: Advanced Techniques

What is a Writer’s Voice & Tips for Finding Your Writing Voice

Dialogue Tag Format: What are Speech Tags? With Examples

Nonfiction Writing Checklist for Your Book

What is Alliteration? Definition, examples and tips

A Complete Guide To Writing Dialogue

One of the writer’s most effective tools is dialogue. A story with little or no conversation between characters can sometimes make the eyelids flicker. Too much may leave the reader breathless. Writing dialogue is tough and a skill that takes time to master.

However, there are plenty of useful tips, tools and methods to help you learn how to write dialogue in a story and how to format it too.

And for your benefit, you can find them all in this comprehensive guide.

Below, you can find the definition of dialogue, tags and formatting guidelines and a discussion on the different ways characters speak and converse.

And you can also find plenty of illuminating dialogue examples to help you gain a clear understanding of the mechanics and how you can apply it to our own writing.

You can jump through this guide by clicking below:

Choose A Chapter

What is dialogue, how to format dialogue.

- Should I Use ‘Said’ And Asked?

How To Write Dialogue Between Two Characters

How to write dialogue readers love, how to write internal dialogue, an exercise on how to write dialogue in a story, good dialogue examples from fiction, technical writing tip – how does dialogue impact the pacing of a story, how do you edit dialogue, more guides on creative writing.

Dialogue is defined as a conversation between two or more characters , particularly in the context of a book, film or play.

Specific to writing, dialogue is the conversation between characters.

A n author may use dialogue to provide the reader with new information about characters or the plot, delivered in a more natural way. They may also utilise it to speed up the pace of the story.

As we’ll see below, there seems to be one pervading guideline when it comes to writing great dialogue and that is clarity reigns supreme.

What Is Internal Dialogue?

Internal dialogue is that which happens within a character’s mind . This can sometimes be reflected in fiction with the use of italics. For example:

I hope they don’t come down here, Mycah thought.

Internal dialogue is a great way of delving deeper into a character’s mind and perspective and is a powerful weapon when it comes to characterization. We explore it in more detail below.

Writers have different stylistic preferences when it comes to dialogue. Below, we’ll take a look at some of the best practices and common literary conventions, such as the use of a dialogue tag and quotation marks.

Using Quotation Marks

If sticking to the principle of clarity reigns supreme, then for me, using double quotation marks is the most effective way of communicating dialogue.

They’re universally recognised as a means of conveying dialogue, and they stand out more on the page in contrast to single quotation marks. There are more reasons for using them, however, and that involves a criqute of the single quotation mark.

Writing Dialogue With Single Quotation Marks

This does come down to a matter of style.

The best format I’ve found, and by best I mean the approach readers find clearest, is to use speech marks (“) as opposed to a single apostrophe (‘).

If, for instance, a character is speaking and quotes someone else, single quotation marks can be used within the speech marks, therefore avoiding any confusion, for example:

“I can’t believe she called me ‘an ungrateful cow.’ She’s got some nerve.”

Format Dialogue On A Single Line

Another helpful approach to help maintain clarity is to begin a piece of dialogue on a new line whenever a new character speaks. For instance:

“Who was at the door?” Nick asked. “A couple of Mormons,” Sarah said.

Adding Dialogue Tags

Dialogue tags are simply a piece of prose that follows a piece of speech that identifies who spoke. You can see it in the example above featuring Nick and Sarah.

You can use a dialogue tag in lots of useful ways. For example body language.

If a character reacts to something another character says or does, to maintain clarity, pop the reaction on a new line, followed by dialogue. So for example:

“We’re all sold out,” Dan said. Jim sighed. “Have you not got any in the back?”

Do You Always Need To Use Dialogue Tags?

Something I’ve noticed some of my favourite writers doing—James Barclay and George R.R. Martin, in particular—is, when possible, avoid using an attribution altogether. Less is more, as they say. If just a couple of people are talking, it may already be clear from the voices and language of the characters who exactly is speaking.

Again, to aid clarity, if there are a number of people involved in a conversation, it helps to use an attribution whenever a different character speaks. Nobody wants to waste time re-reading passages to check who’s speaking. I don’t enjoy it and I’m sure others don’t either.

Repetitive use of attribution may grate on a reader. It can suggest a lack of trust in them to follow the story. It helps when editing to look for moments where it’s unclear who’s speaking and if necessary add an attribution.

A brief point on the styles of attribution. If you read a lot, you may notice some writers prefer the order “John said,” and some prefer “said John”. Sanderson is of the view that the character’s name should come first because that’s the most important bit of information to the reader. But the likes of Tolkien adopted the latter version. It’s all personal preference. Why not mix and match?

Should I Use “Said” And “Asked”?

When it comes to the questions I often see asked on how to write dialogue, this is perhaps the most common.

An attribution, also known as an identifier or tag, is the part of the sentence that follows a piece of dialogue. For example: “John said.” In his creative writing lectures, Brandon Sanderson shares a few useful tips.

- Try to place the attribution as early as possible to help make it clear in the reader’s mind who is speaking. This can be done mid-sentence, such as: “I don’t fancy that,” Milo said. “What else do you have?” Breaking away like this works well if a character is going to be speaking for a few lines or paragraphs. You can also use an attribution before the dialogue, though there’s something about this that I find jarring. Used sparingly it works well, but too often just seems annoying and archaic. It’s all personal preference though.

- Try using beats, but not too many. What’s a beat? A beat is a reaction to something said or done. So for example facial expressions like frowning, smiling, narrowing of the eyes, biting of the lip, and hand gestures such as pointing, clenching fists, and fidgeting. And then you’ve got physical movements, like pacing up and down, smashing a glass, punching a wall.

- Don’t worry about using ‘said’ and ‘asked’. To the reader, these words are almost invisible. What they care about is who exactly is speaking.

- When a character first speaks refer to them by name, but after that, it’s fine to refer to them as he or she, provided they’re still the one speaking. It’s even desirable to use the pronoun; repeating a name over and over can irritate a reader.

Remember the overarching principle for when it comes to writing dialogue: clarity reigns supreme. Using ‘said’ and ‘asked’ is often the clearest way of getting your point across.

What To Use Instead Of Said In Dialogue

Remember, there’s no problem with using the word ‘said’ after a piece of dialogue. But if you find when reading your piece aloud that the repeated use jars, especially in a dialogue-rich scene, you may want to mix things up.

Using words other than ‘said’ can help to characterize too—everybody reacts differently to things and those reactions reveal a lot about a person.

So, here’s a list of twenty words that you can use instead of ‘said’ when writing dialogue:

- Pointed out

- Interrupted

So, let’s take a look at how to write dialogue between two characters. If you’d rather have a visual explainer, check out this informative video below.

A useful distinction to make is between everyday dialogue and the dialogue we find in fiction.

The chatter we hear in real life is full of rambling, repetitive sentences, grumbles, grunts, ‘erms’ and ‘ahs’, with answers to questions filled with echoes (repeating a part of the question posed, e.g. “How are you?” asked A. “How am I?” B answered).

When we think of the dialogue we read in books, it contains little of the things we find in these everyday exchanges. According to Sol Stein, there’s a reason for this—it’s boring to read.

If it holds no relevance to the story, we don’t care if a character’s cat prefers to eat at your neighbour’s house instead of your own, or if they think their nail job isn’t worth the money they paid, or if they think the window cleaner isn’t cleaning their windows. There are some snippets we overhear on the street that are interesting—an unusual name, a section of a story we want to know more about. Rare diamonds in a mine miles deep. I’ve fallen into the trap of trying to achieve realistic dialogue and it makes for drawn-out scenes and boring exchanges.

According to Stein, dialogue ought not to be a recording of actual speech, but rather a semblance of it.

What is this semblance of dialogue why should we try and achieve it?

So, how do we write good dialogue?

When we scrutinise a person as they’re talking (all the boring stuff aside) we discover a lot about their character: who they are, what they believe in, and sometimes, if they reveal them, their motives. We glean all this from word choice, sentence structure, choice of topic, their behaviour as they say something.

It’s these little details we as writers must dig for, so when it comes to writing our own dialogue, we can use them to help characterise our own characters and, if possible, develop the plot. The key to mastering dialogue , according to Stein, is to factor in both characterisation and plot.

How do we do it? Let’s look at some dialogue writing examples:

Milford: How are you? Belle: How am I? I’m fine. How are you? Milford: Well thanks. And the family? Belle: Great

I had to stop myself from stabbing my eyes out with my pen. This example is mundane, riddled with echoes, and gives us no imagery about the characters involved. How about this version?

Milford: How are you? Belle: Oh, I’m sorry, didn’t see you there. Milford: Is this a bad time? Belle: No, no. Absolutely not.

See the difference? Milford asks Belle a question, which Belle doesn’t answer. This is an example of oblique dialogue . It’s indirect, evasive, and creates conflict.

It’s a great tool for when it comes to looking at how to write dialogue in a story using different approaches. Our character is not getting answers. Oblique language helps to reveal a bit about the characters and the plot, namely that Belle could be a bit shifty and up to something unsavoury.

Writing Realistic Dialogue

When it comes to knowing how to write natural dialogue, the question to ask yourself is whether or not this style is going to fit your story.

Natural dialogue suits some stories wonderfully. However, it can also work against your story, maybe confusing things for your readers or making it too difficult to read.

When it comes to writing natural dialogue, it’s important to bear in mind the principles discussed here. Give your conversations purpose, make them oblique or intriguing, and don’t give information up cheaply.

You can achieve this in a natural or more casual or informal style.

If you’re looking for more visual tips and advice on writing dialogue, check out this excellent video below:

Say It Aloud

When you’ve written a piece of dialogue, one of the best and simplest techniques to check how it works is to say it out loud.

In doing so you’ll get a sense of how natural it is or whether it jars, or even if it’s cringy or cliche—we’ve all been there.

If you don’t feel comfortable speaking it aloud, you can use a Text to Voice function, like on a website like Natural Readers which allows you to paste in text and then have it read it back to you (it’s free).

Add Slang From Your World

An effective way to write good dialogue that not only characterizes and drives the plot but adds to your world, is to use slang or world-specific references. This can be particularly useful in the fantasy and sci-fi genres .

For example, in my novel Pariah’s Lament , I refer to the world in place of phrases that refer to our own. So instead of “What in the world was that?” I’d say something like “What in Tervia was that?”

Small Talk And Hellos And Goodbyes

As a general rule, there’s no need to include small talk, hellos and goodbyes. The reader isn’t really too bothered about these niceties. They just want to get to the action, the conflict.

You can brush over things like small talk and hellos with short descriptions in your prose writing . For instance:

Stef and John stepped into the room. A sea of smiling faces welcomed them and before they knew it, they were shaking hands and embracing. “I wasn’t expecting such a warm welcome,” Stef said. “It’s like they have no idea what we’ve done,” John replied. “Maybe they don’t.” “Or maybe they do, and it’s all a ruse.” Stef looked at him a moment, thoughtful. “You’re getting paranoid.”

See here how the hellos were glided by and we’re straight into more interesting dialogue? You can also cut back on the odd superfluous dialogue tag too if it doesn’t add to your story.

Give Your Characters Their Own Voice

A character’s voice is an important factor in dialogue. Nobody speaks in the same way. Some people have lisps, some people say their ‘r’s’ like ‘w’s’, some people don’t enunciate properly, say words differently, speak in accents, and have a nasal twang. There are so many variables.

Introducing these features to some or all of your characters can help to make them more memorable and distinct.

How To Write Dialogue For A Drunk Character

When we’re writing our stories it’s likely that some of our characters may become intoxicated with alcohol or drugs. This creates the question in a writer’s mind, how do you write dialogue for a drunk character?

We can fall into the trap of spelling out the words that they try to say, factoring in the slurs, the missed words and the mispronunciations. The problem this can create is that it can go against our overarching principle of clarity reigns supreme.

Dialogue that’s too difficult to read can cause frustration in the reader. They may get fed up and stop reading altogether—the last thing we want.

The best technique is to provide a description of how the person is talking. Describe how they slur their words, how certain letters sound in their drunken state and so on. Including body language in this will help a great deal too. You can then write dialogue in a more natural and understandable way.

The same applies to the likes of writing stuttering in dialogue. It can be very frustrating for a person to listen to a person with a stutter. To include it in your writing can cause problems too. So again one of the best solutions is to describe the stutter first and then write dialogue naturally.

Hopefully, these tips will help you with how to write dialogue for our intoxicated characters.

An Author May Use Dialogue To Provide The Reader With Information, But Don’t Info Dump

An author may use dialogue to provide the reader with useful information. However, if done incorrectly it can have a negative effect.

In his book The First Five Pages , Noah Lukeman says that one of his biggest reasons for rejecting a manuscript is the use of informative dialogue. In other words, using dialogue as a means for conveying information, or info-dumping . He says it suggests the writer is lazy, too unimaginative to convey the information in a subtler way. If you’d like to learn more about avoiding info dumps, check out my guide on natural worldbuilding .

Sometimes dialogue will give us no information at all. Sometimes snippets. Often if you overhear a conversation between two people you’ll find you understand little of what they discuss. It’s the little details they reveal that are most interesting. Take the example of someone mentioning they went to the hospital. The person they’re with may know why they went, but you don’t. Give the reader pieces of the giant puzzle and leave them wanting more.

Lukeman suggests a few solutions to mend instances of informative dialogue. One is to highlight pieces of dialogue that merely convey information and do not reveal or suggest the character’s personality or wants. Break them apart and find a way to let them trickle into the story.

Understanding how to write internal dialogue can prove a key weapon in your writing arsenal.

This style of dialogue can be employed effectively in scenes or stories focused on lone characters. It can break up the monotony of long paragraphs of exposition, which provides welcome relief to readers. Unlike other forms, you don’t need to use a dialogue tag as such.

There are a couple of common ways that you can employ internal dialogue in writing:

- The first option is to italicise the comments made by your character internally. For example: “A door downstairs slammed shut. It’s not windy tonight. How the hell could that have happened?” The main idea here is that the italicised words make it clear to the reader that this is internal dialogue.

- Another option is to write internal dialogue as you would normal dialogue, with speech marks. The difference is what follows that passage of conversation. Usually, it’s something like, “I really do need to get that fixed,” Halle thought to herself. Here, you simply identify that the dialogue was spoken in the mind and not aloud.

As for which is best for how to write effective dialogue for internal thoughts, it’s all a matter of style. However, my personal preference is using italics. To me, it’s just clearer to readers, and that’s the main aim. So that is how to write internal dialogue.

As a little exercise, try and think of some oblique responses to the following line. I’ll give you an example to start. Remember to factor in Stein’s key ingredients— characterisation and plot:

Exercise: “You’re the most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen.”

Example: “Did you say the same thing to that blonde girl behind the bar?”

In this example of how to write dialogue, we get a response that avoids answering the statement. She could quite easily turn around and say “Thank you,” but that’s boring. Instead, we’re wondering about this man and what he’s about, and a bit more about the woman too, namely that she’s observant.