Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

FIND YOUR SCHOOL

Degree program, areas of focus, tuition range.

Continue to School Search

- Where to Study

- What to Know

- Your Journey

2020 Student Thesis Showcase - Part I

Have you ever wondered what students design in architecture school? A few years ago, we started an Instagram account called IMADETHAT_ to curate student work from across North America. Now, we have nearly 3,000 projects featured for you to view. In this series, we are featuring thesis projects of recent graduates to give you a glimpse into what architecture students create while in school. Each week, for the rest of the summer, we will be curating five projects that highlight unique aspects of design. In this week’s group, the research ranges from urban scale designs focused on climate change to a proposal for a new type of collective housing and so much in between. Check back each week for new projects.

In the meantime, Archinect has also created a series featuring the work of 2020 graduates in architecture and design programs. Check out the full list, here .

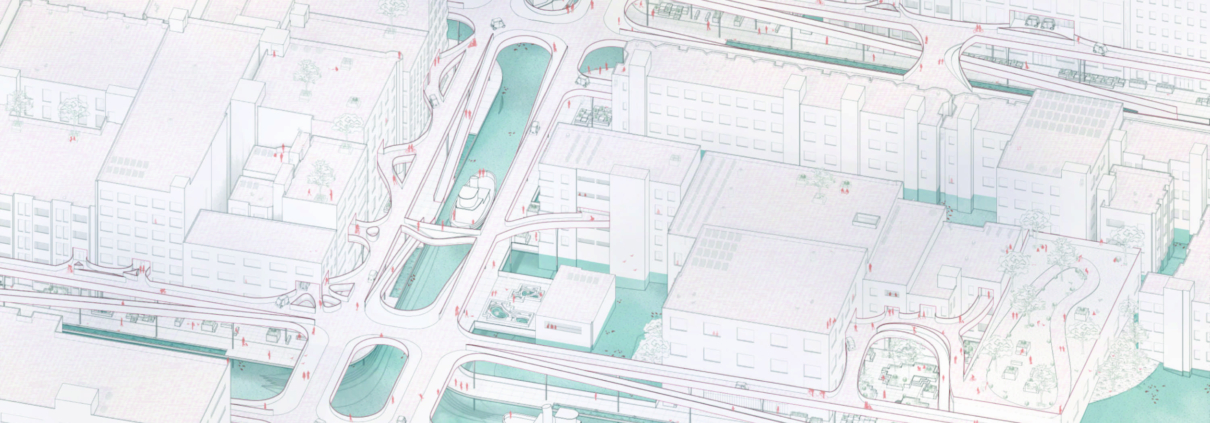

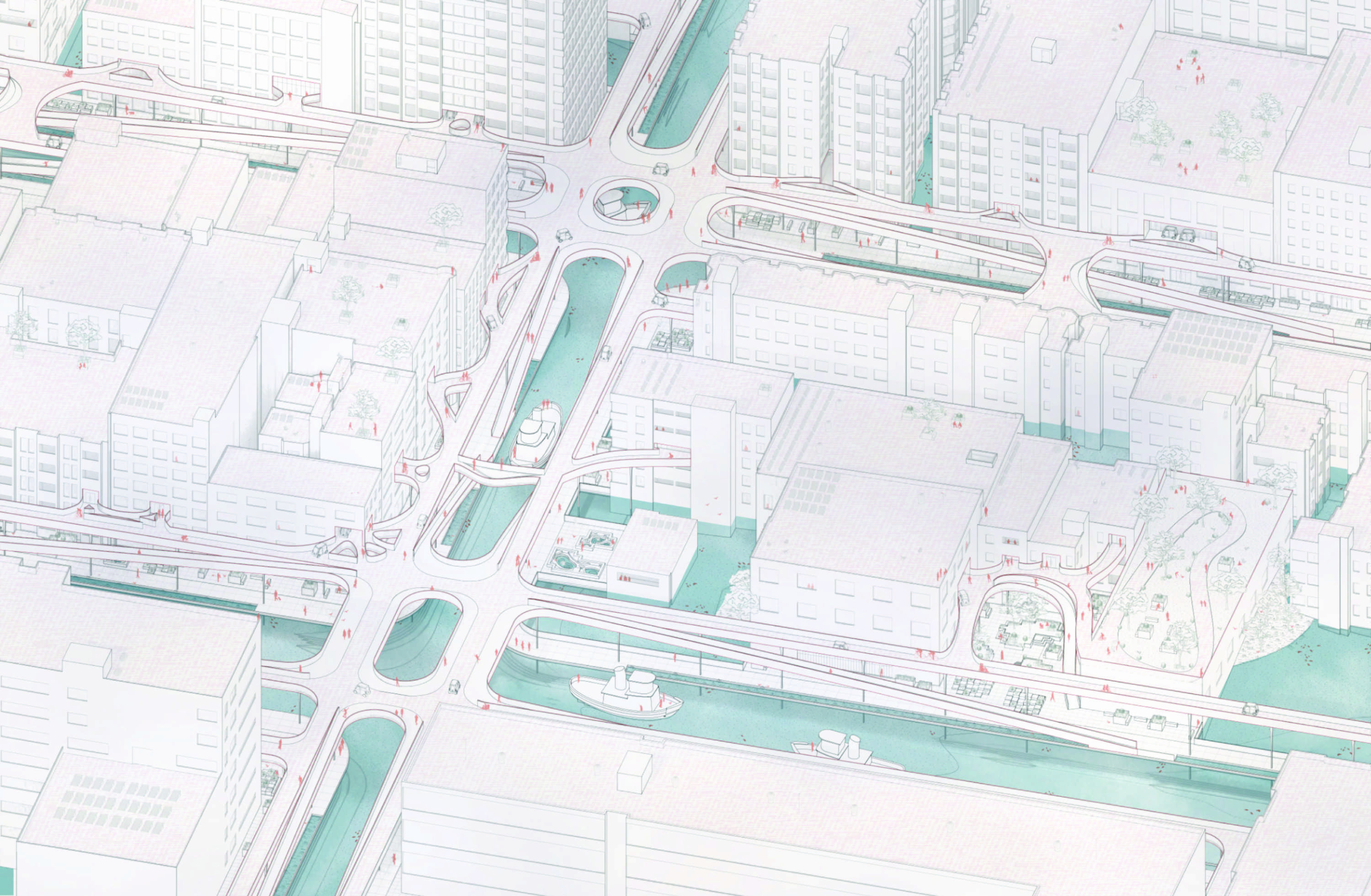

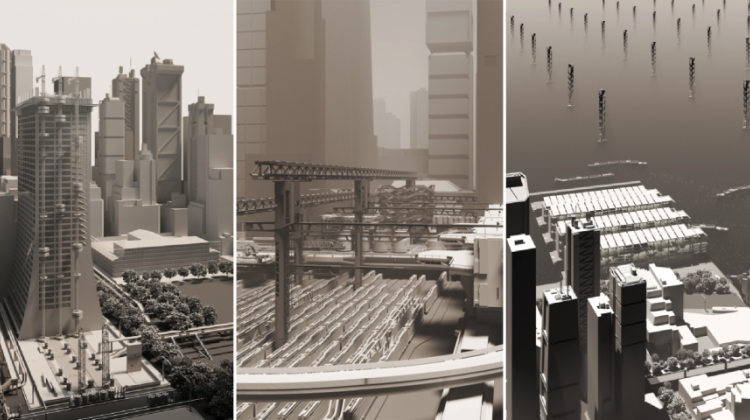

Redefining the Gradient by Kate Katz and Ryan Shaaban, Tulane University, M.Arch ‘20

Thesis Advisors: Cordula Roser Gray and Ammar Eloueini / Course: 01-SP20-Thesis Studio

Sea level rise has become a major concern for coastal cities due to the economic and cultural importance tied to their proximity to water. These cities have sustained their livelihood in low-lying elevations through the process of filling, bridging, and raising land over coastal ecosystems, replacing their ecological value with infrastructures focused on defining the edge between city and nature. Hard infrastructures have been employed to maintain urban landscapes but have minimal capacity for both human and non-human engagement due to their monofunctional applications focused on separating conditions rather than integrating them. They produce short-term gains with long-term consequences, replacing and restricting ecosystems and acting as physical barriers in a context defined by seasonal transition.

To address the issues of hard infrastructure and sea level rise, this thesis proposes an alternative design strategy that incorporates the dynamic water system into the urban grid network. San Francisco was chosen as the location of study as it is a peninsula where a majority of the predicted inundation occurs on the eastern bayside. In this estuary, there were over 500 acres of ecologically rich tidal marshlands that were filled in during the late 1800s. To protect these new lands, the Embarcadero Sea Wall was built in 1916 and is now in a state of neglect. The city has set aside $5 billion for repairs but, instead of pouring more money into a broken system, we propose an investment in new multi-functional ecologically-responsive strategies.

As sea levels rise, the city will be inundated with water, creating the opportunity to develop a new circulation system that maintains accessibility throughout areas located in the flood zone. In this proposal, we’ve designed a connective network where instance moments become moments of pause and relief to enjoy the new cityscape in a dynamic maritime district.

On the lower level, paths widen to become plazas while on the upper level, they become breakout destinations which can connect to certain occupiable rooftops that are given to the public realm. The bases of carved canals become seeding grounds for plants and aquatic life as the water level rises over time. Buildings can protect high-risk floors through floodproofing and structural encasement combined with adaptive floorplates to maintain the use of lower levels. The floating walkway is composed of modular units that are buoyant, allowing the pedestrian paths to conform and fluctuate with diurnal tidal changes. The composition of the units creates street furniture and apertures to engage with the ecologies below while enabling a once restricted landscape of wetlands to take place within the city.

The new vision of the public realm in this waterfront district hopes to shine an optimistic light on how we can live with nature once again as we deal with the consequences of climate change.

Unearthing the Black Aesthetic by Demar Matthews, Woodbury University, M.Arch ‘20

Advisor: Ryan Tyler Martinez Featured on Archinect

“Unearthing The Black Aesthetic” highlights South Central Los Angeles’s (or Black Los Angeles’s) unique positioning as a dynamic hub of Black culture and creativity. South Central is the densest population of African Americans west of the Mississippi. While every historically Black neighborhood in Los Angeles has experienced displacement, the neighborhood of Watts was hit particularly hard. As more and more Black Angelenos are forced for one reason or another to relocate, we are losing our history and connection to Los Angeles.

As a way to fight this gentrification, we are developing an architectural language derived from Black culture. So many cultures have their own architectural styles based on values, goals, morals, and customs shared by their society. When these cultures have relocated to America, to keep their culture and values intact, they bought land and built in the image of their homelands. That is not true for Black people in America. In fact, until 1968, Black people had no rights to own property in Los Angeles. While others began a race to acquire land in 1492, building homes and communities in their image, we started running 476 years after the race began. What percentage of land was left for Blacks to acquire? How then can we advance the development of a Black aesthetic in architecture?

This project, most importantly, is a collaboration with the community that will be for us and by us. My goal is to take control of our image in architecture; to elevate, not denigrate, Black life and culture. Ultimately, we envision repeating this process in nine historically Black cities in America to develop an architectural language that will vary based on the history and specificities of Black culture in each area.

KILLING IT: The Life and Death of Great American Cities by Amanda Golemba, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, M.Arch ’20

Advisors: Nikole Bouchard, Jasmine Benyamin, and Erik Hancock / Independent Design Thesis

For decades, post-industrial cities throughout the United States have been quietly erased through self-imposed tabula rasa demolition. If considered at all, demolition is touted as the mechanism for removing unsightly blight, promoting safety, and discarding the obsolete and the unwanted. Once deemed unworthy, rarely does a building survive the threat of demolition.

In the last decade, the City of Chicago has erased over 13,000 buildings with 225 in just the last four months. Not only does this mass erasure eradicate the material and the spatial, but it permanently wipes the remnants of human bodies, values, and history — a complete annulment of event, time, and memory.

But why do we feel the need to erase in order to make progress?

Our current path has led to a built environment that is becoming more and more uniform and sterile. Much of America has become standardized, mixed-use developments; neighborhoods of cookie-cutter homes and the excessive use of synthetic, toxic building materials. A uniform world is a boring one that has little room for creativity, individuality, or authenticity.

This thesis, “KILLING IT,” is a design proposal for a traveling exhibition that seeks to change perceptions of the existing city fabric by visualizing patterns of erasure, questioning the resultant implications and effects of that erasure, and proposing an alternative fate. “KILLING IT” confronts the inherently violent aspects of architecture and explores that violence through the intentionally jarring, uncomfortable, and absurd analogy of murder. This analogy is a lens through which to trace the violent, intentional, and premature ending and sterilization of the existing built environment. After all, as Bernard Tschumi said, “To really appreciate architecture, you may even need to commit a murder.”1 But murder is not just about the events that take place within a building, it is also the material reality of the building itself.

Over the life of a building, scarring, moments in time, and decay layer to create an inhabitable palimpsest of memory. This traveling exhibition is infused with the palimpsest concept by investigating strategies of layering, modularity, flexibility, transparency, and building remains, while layering them together to form a system that operates as an inhabitable core model collage. Each individual exhibition simultaneously memorializes the violence that happened at that particular site and implements murderous adaptive reuse strategies through collage and salvage material to expose what could have been.

If we continue down our current path, we will only continue to make the same mistakes and achieve the same monotonous, sterilizing results we currently see in every American city and suburb. We need to embrace a new path that values authenticity, celebrates the scars and traces of the past, and carries memories into the future. By reimaging what death can mean and addressing cycles of violence, “KILLING IT” proposes an optimistic vision for the future of American cities.

- Tschumi, Bernard. “Questions of space: lectures on architecture” (ed. 1990)

A New Prototype for Collective Housing by Juan Acosta and Gable Bostic, University of Texas at Austin, M.Arch ‘20

Advisor: Martin Haettasch / Course: Integrative Design Studio Read more: https://soa.utexas.edu/work/new-prototype-collective-housing

Austin is a city that faces extreme housing pressures. This problem is framed almost exclusively in terms of supply and demand, and the related question of affordability. For architects, however, a more productive question is: Will this new quantity produce a new quality of housing?

How do we live in the city, how do we create individual and collective identity through architecture, and what are the urban consequences? This studio investigates new urban housing types, smaller than an apartment block yet larger and denser than a detached house. Critically assessing existing typologies, we ask the question: How can the comforts of the individual house be reconfigured to form new types of residential urban fabric beyond the entropy of tract housing or the formulaic denominator of “mixed-use.” The nature of the integrative design studio allowed for the testing of material systems and construction techniques that have long had an important economic and ecological impact.

“A New Prototype for Collective Housing” addresses collectivity in both a formal and social sense, existing between the commercial and residential scales present in Austin’s St. John neighborhood as it straddles the I-35 corridor; a normative American condition. A diversity of programs, and multigenerational living, create an inherently diverse community. Additionally, a courtyard typology is used to negotiate the spectrum of private and shared space. Volumes, comprising multiple housing units ranging from studio apartments to four bedrooms, penetrate a commercial plinth that circulates both residents and mechanical systems. The use of heavy timber ensures an equitable use of resources while imbuing the project with a familiar material character.

ELSEWHERE, OR ELSE WHERE? by Brenda (Bz) Zhang, University of California at Berkeley, M.Arch ’20

Advisors: Andrew Atwood and Neyran Turan See more: https://www.brendazhang.com/#/elsewhere-or-else-where/

“ELSEWHERE, OR ELSE WHERE?” is an architectural fever dream about the San Francisco Bay Area. Beginning with the premise that two common ideas of Place—Home and Elsewhere—are no longer useful, the project wonders how disciplinary tools of architecture can be used to shape new stories about where we are.

For our purposes, “Home,” although primarily used to describe a place of domestic habitation, is also referring generally to a “familiar or usual setting,” as in home-base, home-court, home-page, and even home-button. As a counterpoint, Elsewhere shifts our attention “in or to another place,” away. This thesis is situated both in the literal spaces of Elsewhere and Home (landfills, houses, wilderness, base camps, wastelands, hometowns) and in their culturally constructed space (value-embedded narratives determining whether something belongs, and to whom). Since we construct both narratives through principles of exclusion, Elsewhere is a lot closer to Home than we say. These hybrid spaces—domestic and industrial, urban and hinterland, natural and built—are investigated as found conditions of the Anthropocene and potential sites for new understandings of Place.

Ultimately, this thesis attempts to challenge conventional notions of what architects could do with our existing skill sets, just by shifting our attention—Elsewhere. The sites shown here and the concerns they represent undeniably exist, but because of the ways Western architecture draws thick boundaries between and around them, they resist architectural focus—to our detriment.

In reworking the physical and cultural constructions of Homes and Elsewheres, architects are uniquely positioned to go beyond diagnostics in visualizing and designing how, where, and why we build. While this project looks specifically at two particular stories we tell about where we are, the overall objective is to provoke new approaches to how we construct Place—both physically and culturally—within or without our discipline.

Share this entry

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Mail

You might also like

About Study Architecture

- Section 2: Home

- Developing the Quantitative Research Design

- Qualitative Descriptive Design

- Design and Development Research (DDR) For Instructional Design

- Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Research

- Action Research Resource

- Case Study Design in an Applied Doctorate

Qualitative Research Designs

Case study design, using case study design in the applied doctoral experience (ade), applicability of case study design to applied problem of practice, case study design references.

- SAGE Research Methods

- Research Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- Dataset Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- IRB Resource Center This link opens in a new window

The field of qualitative research there are a number of research designs (also referred to as “traditions” or “genres”), including case study, phenomenology, narrative inquiry, action research, ethnography, grounded theory, as well as a number of critical genres including Feminist theory, indigenous research, critical race theory and cultural studies. The choice of research design is directly tied to and must be aligned with your research problem and purpose. As Bloomberg & Volpe (2019) explain:

Choice of research design is directly tied to research problem and purpose. As the researcher, you actively create the link among problem, purpose, and design through a process of reflecting on problem and purpose, focusing on researchable questions, and considering how to best address these questions. Thinking along these lines affords a research study methodological congruence (p. 38).

Case study is an in-depth exploration from multiple perspectives of a bounded social phenomenon, be this a social system such as a program, event, institution, organization, or community (Stake, 1995, 2005; Yin, 2018). Case study is employed across disciplines, including education, health care, social work, sociology, and organizational studies. The purpose is to generate understanding and deep insights to inform professional practice, policy development, and community or social action (Bloomberg 2018).

Yin (2018) and Stake (1995, 2005), two of the key proponents of case study methodology, use different terms to describe case studies. Yin categorizes case studies as exploratory or descriptive . The former is used to explore those situations in which the intervention being evaluated has no clear single set of outcomes. The latter is used to describe an intervention or phenomenon and the real-life context in which it occurred. Stake identifies case studies as intrinsic or instrumental , and he proposes that a primary distinction in designing case studies is between single and multiple (or collective) case study designs. A single case study may be an instrumental case study (research focuses on an issue or concern in one bounded case) or an intrinsic case study (the focus is on the case itself because the case presents a unique situation). A longitudinal case study design is chosen when the researcher seeks to examine the same single case at two or more different points in time or to capture trends over time. A multiple case study design is used when a researcher seeks to determine the prevalence or frequency of a particular phenomenon. This approach is useful when cases are used for purposes of a cross-case analysis in order to compare, contrast, and synthesize perspectives regarding the same issue. The focus is on the analysis of diverse cases to determine how these confirm the findings within or between cases, or call the findings into question.

Case study affords significant interaction with research participants, providing an in-depth picture of the phenomenon (Bloomberg & Volpe, 2019). Research is extensive, drawing on multiple methods of data collection, and involves multiple data sources. Triangulation is critical in attempting to obtain an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon under study and adds rigor, breadth, and depth to the study and provides corroborative evidence of the data obtained. Analysis of data can be holistic or embedded—that is, dealing with the whole or parts of the case (Yin, 2018). With multiple cases the typical analytic strategy is to provide detailed description of themes within each case (within-case analysis), followed by thematic analysis across cases (cross-case analysis), providing insights regarding how individual cases are comparable along important dimensions. Research culminates in the production of a detailed description of a setting and its participants, accompanied by an analysis of the data for themes or patterns (Stake, 1995, 2005; Yin, 2018). In addition to thick, rich description, the researcher’s interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations contribute to the reader’s overall understanding of the case study.

Analysis of findings should show that the researcher has attended to all the data, should address the most significant aspects of the case, and should demonstrate familiarity with the prevailing thinking and discourse about the topic. The goal of case study design (as with all qualitative designs) is not generalizability but rather transferability —that is, how (if at all) and in what ways understanding and knowledge can be applied in similar contexts and settings. The qualitative researcher attempts to address the issue of transferability by way of thick, rich description that will provide the basis for a case or cases to have relevance and potential application across a broader context.

Qualitative research methods ask the questions of "what" and "how" a phenomenon is understood in a real-life context (Bloomberg & Volpe, 2019). In the education field, qualitative research methods uncover educational experiences and practices because qualitative research allows the researcher to reveal new knowledge and understanding. Moreover, qualitative descriptive case studies describe, analyze and interpret events that explain the reasoning behind specific phenomena (Bloomberg, 2018). As such, case study design can be the foundation for a rigorous study within the Applied Doctoral Experience (ADE).

Case study design is an appropriate research design to consider when conceptualizing and conducting a dissertation research study that is based on an applied problem of practice with inherent real-life educational implications. Case study researchers study current, real-life cases that are in progress so that they can gather accurate information that is current. This fits well with the ADE program, as students are typically exploring a problem of practice. Because of the flexibility of the methods used, a descriptive design provides the researcher with the opportunity to choose data collection methods that are best suited to a practice-based research purpose, and can include individual interviews, focus groups, observation, surveys, and critical incident questionnaires. Methods are triangulated to contribute to the study’s trustworthiness. In selecting the set of data collection methods, it is important that the researcher carefully consider the alignment between research questions and the type of data that is needed to address these. Each data source is one piece of the “puzzle,” that contributes to the researcher’s holistic understanding of a phenomenon. The various strands of data are woven together holistically to promote a deeper understanding of the case and its application to an educationally-based problem of practice.

Research studies within the Applied Doctoral Experience (ADE) will be practical in nature and focus on problems and issues that inform educational practice. Many of the types of studies that fall within the ADE framework are exploratory, and align with case study design. Case study design fits very well with applied problems related to educational practice, as the following set of examples illustrate:

Elementary Bilingual Education Teachers’ Self-Efficacy in Teaching English Language Learners: A Qualitative Case Study

The problem to be addressed in the proposed study is that some elementary bilingual education teachers’ beliefs about their lack of preparedness to teach the English language may negatively impact the language proficiency skills of Hispanic ELLs (Ernst-Slavit & Wenger, 2016; Fuchs et al., 2018; Hoque, 2016). The purpose of the proposed qualitative descriptive case study was to explore the perspectives and experiences of elementary bilingual education teachers regarding their perceived lack of preparedness to teach the English language and how this may impact the language proficiency of Hispanic ELLs.

Exploring Minority Teachers Experiences Pertaining to their Value in Education: A Single Case Study of Teachers in New York City

The problem is that minority K-12 teachers are underrepresented in the United States, with research indicating that school leaders and teachers in schools that are populated mainly by black students, staffed mostly by white teachers who may be unprepared to deal with biases and stereotypes that are ingrained in schools (Egalite, Kisida, & Winters, 2015; Milligan & Howley, 2015). The purpose of this qualitative exploratory single case study was to develop a clearer understanding of minority teachers’ experiences concerning the under-representation of minority K-12 teachers in urban school districts in the United States since there are so few of them.

Exploring the Impact of an Urban Teacher Residency Program on Teachers’ Cultural Intelligence: A Qualitative Case Study

The problem to be addressed by this case study is that teacher candidates often report being unprepared and ill-equipped to effectively educate culturally diverse students (Skepple, 2015; Beutel, 2018). The purpose of this study was to explore and gain an in-depth understanding of the perceived impact of an urban teacher residency program in urban Iowa on teachers’ cultural competence using the cultural intelligence (CQ) framework (Earley & Ang, 2003).

Qualitative Case Study that Explores Self-Efficacy and Mentorship on Women in Academic Administrative Leadership Roles

The problem was that female school-level administrators might be less likely to experience mentorship, thereby potentially decreasing their self-efficacy (Bing & Smith, 2019; Brown, 2020; Grant, 2021). The purpose of this case study was to determine to what extent female school-level administrators in the United States who had a mentor have a sense of self-efficacy and to examine the relationship between mentorship and self-efficacy.

Suburban Teacher and Administrator Perceptions of Culturally Responsive Teaching to Promote Connectedness in Students of Color: A Qualitative Case Study

The problem to be addressed in this study is the racial discrimination experienced by students of color in suburban schools and the resulting negative school experience (Jara & Bloomsbury, 2020; Jones, 2019; Kohli et al., 2017; Wandix-White, 2020). The purpose of this case study is to explore how culturally responsive practices can counteract systemic racism and discrimination in suburban schools thereby meeting the needs of students of color by creating positive learning experiences.

As you can see, all of these studies were well suited to qualitative case study design. In each of these studies, the applied research problem and research purpose were clearly grounded in educational practice as well as directly aligned with qualitative case study methodology. In the Applied Doctoral Experience (ADE), you will be focused on addressing or resolving an educationally relevant research problem of practice. As such, your case study, with clear boundaries, will be one that centers on a real-life authentic problem in your field of practice that you believe is in need of resolution or improvement, and that the outcome thereof will be educationally valuable.

Bloomberg, L. D. (2018). Case study method. In B. B. Frey (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (pp. 237–239). SAGE. https://go.openathens.net/redirector/nu.edu?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmethods.sagepub.com%2FReference%2Fthe-sage-encyclopedia-of-educational-research-measurement-and-evaluation%2Fi4294.xml

Bloomberg, L. D. & Volpe, M. (2019). Completing your qualitative dissertation: A road map from beginning to end . (4th Ed.). SAGE.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. SAGE.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 443–466). SAGE.

Yin, R. (2018). Case study research and applications: Designs and methods. SAGE.

- << Previous: Action Research Resource

- Next: SAGE Research Methods >>

- Last Updated: Jul 28, 2023 8:05 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1013605

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in relation to explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular case [i.e., subject of analysis] and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that constitutes your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; and, c) what were the consequences of the event in relation to the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experiences they have had that provide an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of their experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using them as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem [e.g., why is one politician in a particular local election used to show an increase in voter turnout from any other candidate running in the election]. Note that these issues apply to a specific group of people used as a case study unit of analysis [e.g., a classroom of students].

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, historical, cultural, economic, political], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, explain why you are studying Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research suggests Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut off? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should clearly support investigation of the research problem and linked to key findings from your literature review. Be sure to cite any studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for examining the problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your analysis of the case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is common to combine a description of the results with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.

Relate the Findings to Similar Studies No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your case study results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for choosing your subject of analysis. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your case study design and the subject of analysis differs from prior research about the topic.

Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings Remember that the purpose of social science research is to discover and not to prove. When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations revealed by the case study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. Be alert to what the in-depth analysis of the case may reveal about the research problem, including offering a contrarian perspective to what scholars have stated in prior research if that is how the findings can be interpreted from your case.

Acknowledge the Study's Limitations You can state the study's limitations in the conclusion section of your paper but describing the limitations of your subject of analysis in the discussion section provides an opportunity to identify the limitations and explain why they are not significant. This part of the discussion section should also note any unanswered questions or issues your case study could not address. More detailed information about how to document any limitations to your research can be found here .

Suggest Areas for Further Research Although your case study may offer important insights about the research problem, there are likely additional questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or findings that unexpectedly revealed themselves as a result of your in-depth analysis of the case. Be sure that the recommendations for further research are linked to the research problem and that you explain why your recommendations are valid in other contexts and based on the original assumptions of your study.

V. Conclusion

As with any research paper, you should summarize your conclusion in clear, simple language; emphasize how the findings from your case study differs from or supports prior research and why. Do not simply reiterate the discussion section. Provide a synthesis of key findings presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem. If you haven't already done so in the discussion section, be sure to document the limitations of your case study and any need for further research.

The function of your paper's conclusion is to: 1) reiterate the main argument supported by the findings from your case study; 2) state clearly the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem using a case study design in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found from reviewing the literature; and, 3) provide a place to persuasively and succinctly restate the significance of your research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with in-depth information about the topic.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is appropriate:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize these points for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the conclusion of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration of the case study's findings that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from your case study findings.

Note that, depending on the discipline you are writing in or the preferences of your professor, the concluding paragraph may contain your final reflections on the evidence presented as it applies to practice or on the essay's central research problem. However, the nature of being introspective about the subject of analysis you have investigated will depend on whether you are explicitly asked to express your observations in this way.

Problems to Avoid

Overgeneralization One of the goals of a case study is to lay a foundation for understanding broader trends and issues applied to similar circumstances. However, be careful when drawing conclusions from your case study. They must be evidence-based and grounded in the results of the study; otherwise, it is merely speculation. Looking at a prior example, it would be incorrect to state that a factor in improving girls access to education in Azerbaijan and the policy implications this may have for improving access in other Muslim nations is due to girls access to social media if there is no documentary evidence from your case study to indicate this. There may be anecdotal evidence that retention rates were better for girls who were engaged with social media, but this observation would only point to the need for further research and would not be a definitive finding if this was not a part of your original research agenda.

Failure to Document Limitations No case is going to reveal all that needs to be understood about a research problem. Therefore, just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study , you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis. For example, the case of studying how women conceptualize the need for water conservation in a village in Uganda could have limited application in other cultural contexts or in areas where fresh water from rivers or lakes is plentiful and, therefore, conservation is understood more in terms of managing access rather than preserving access to a scarce resource.

Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings. If you do not, your reader may question the validity of your analysis, particularly if you failed to document an obvious outcome from your case study research. For example, in the case of studying the accident at the railroad crossing to evaluate where and what types of warning signals should be located, you failed to take into consideration speed limit signage as well as warning signals. When designing your case study, be sure you have thoroughly addressed all aspects of the problem and do not leave gaps in your analysis that leave the reader questioning the results.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education . Rev. ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998; Miller, Lisa L. “The Use of Case Studies in Law and Social Science Research.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14 (2018): TBD; Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Putney, LeAnn Grogan. "Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010), pp. 116-120; Simons, Helen. Case Study Research in Practice . London: SAGE Publications, 2009; Kratochwill, Thomas R. and Joel R. Levin, editors. Single-Case Research Design and Analysis: New Development for Psychology and Education . Hilldsale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992; Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London : SAGE, 2010; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Los Angeles, CA, SAGE Publications, 2014; Walo, Maree, Adrian Bull, and Helen Breen. “Achieving Economic Benefits at Local Events: A Case Study of a Local Sports Event.” Festival Management and Event Tourism 4 (1996): 95-106.

Writing Tip

At Least Five Misconceptions about Case Study Research

Social science case studies are often perceived as limited in their ability to create new knowledge because they are not randomly selected and findings cannot be generalized to larger populations. Flyvbjerg examines five misunderstandings about case study research and systematically "corrects" each one. To quote, these are:

Misunderstanding 1 : General, theoretical [context-independent] knowledge is more valuable than concrete, practical [context-dependent] knowledge. Misunderstanding 2 : One cannot generalize on the basis of an individual case; therefore, the case study cannot contribute to scientific development. Misunderstanding 3 : The case study is most useful for generating hypotheses; that is, in the first stage of a total research process, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypotheses testing and theory building. Misunderstanding 4 : The case study contains a bias toward verification, that is, a tendency to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions. Misunderstanding 5 : It is often difficult to summarize and develop general propositions and theories on the basis of specific case studies [p. 221].

While writing your paper, think introspectively about how you addressed these misconceptions because to do so can help you strengthen the validity and reliability of your research by clarifying issues of case selection, the testing and challenging of existing assumptions, the interpretation of key findings, and the summation of case outcomes. Think of a case study research paper as a complete, in-depth narrative about the specific properties and key characteristics of your subject of analysis applied to the research problem.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (April 2006): 219-245.

- << Previous: Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Next: Writing a Field Report >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Successful thesis proposals in architecture and urban planning

Archnet-IJAR

ISSN : 2631-6862

Article publication date: 1 May 2020

Issue publication date: 11 November 2020

The purpose of this research is to improve the understanding of what constitutes a successful thesis proposal (TP) and as such enhance the quality of the TP writing in architecture, planning and related disciplines.

Design/methodology/approach

Based on extended personal experience and a review of relevant literature, the authors proposed a conception of a successful TP comprising 13 standard components. The conception provides specific definition/s, attributes and success rules for each component. The conception was applied for 15 years on several batches of Saudi graduate students. The implications of the conception were assessed by a students' opinion survey. An expert inquiry of experienced academics from architectural schools in nine countries was applied to validate and improve the conception.

Assessment of the proposed conception demonstrated several positive implications on students' knowledge, performance and outputs which illustrates its applicability in real life. Experts' validation of the conception and constructive remarks have enabled further improvements on the definitions, attributes and success rules of the TP components.

Research limitations/implications

The proposed TP conception with its 13 components is limited to standard problem-solving research and will differ in the case of other types such as hypothesis-based research.

Practical implications

The proposed conception is a useful directive and evaluative tool for writing and assessing thesis proposals for graduate students, academic advisors and examiners.

Social implications

The research contributes to improving the quality of thesis production process among the academic community in the built environment fields.

Originality/value

The paper is meant to alleviate the confusion and hardship caused by the absence of a consensus on what constitutes a successful TP in the fields of architecture, urban planning and related disciplines.

- Urban planning

- Architecture

- Built environment

- Postgraduate research

- Writing successful thesis proposals

Abdellatif, M. and Abdellatif, R. (2020), "Successful thesis proposals in architecture and urban planning", Archnet-IJAR , Vol. 14 No. 3, pp. 503-524. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-12-2019-0281

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Mahmoud Abdellatif and Reham Abdellatif

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode .

1. Introduction

After the postgraduate student completes her/his coursework in a master programme or passes the comprehensive exam and becomes a doctoral candidate in a doctoral programme, s/he is allowed to submit a “Thesis Proposal” (TP) to her/his department whose main concern is to assess whether the topic is suitable for a graduate study and for the time and resources available ( Afful, 2008 ; Kivunja, 2016 ; Reddy, 2019 ).

The department then sends the submitted TP to higher bodies for official approval. Once approved, the TP becomes a legal binding or “a formal contract” ( Walliman, 2017 ) and “a statement of intent” ( Hofstee, 2006 ) between the researcher and the university. If the student adheres to all prescribed TP requirements within the specified time, s/he will be awarded the degree ( Leo, 2019 ).

Guided by his/her academic advisor, the student prepares the TP within which the researcher explains the research problem, questions, aim and objectives, scope, and methodologies to describe, analyse and synthesize the research problem and develop solutions for it ( Paltridge and Starfield, 2007 ). In addition, the proposal includes a brief about research significance and expected contributions; a preliminary review of literature; thesis structure and approximate completion timeline; and a list of relevant references ( Kivunja, 2016 ; Thomas, 2016 ; Kornuta and Germaine, 2019 ).

1.1 Statement of the problem and research aim

After decades of writing, supervising and refereeing master and doctoral theses in the fields of Architecture and Urban Planning, the authors noticed that TP's differ in format and content from a school to another. This may be considered a healthy matter because it gives room for flexibility that absorbs the variety of research problems and techniques. Yet, the absence of a consensus on what constitutes a successful TP could cause confusion and hardship to both students and advisors ( Kamler and Thomson, 2008 ; Abdulai and Owusu-Ansah, 2014 ). The review of literature indicates that TP writing has been tackled in depth in many fields (see for instance Gonzalez, 2007 ; Balakumar et al. , 2013 ; Eco, 2015 ; Kivunja, 2016 ; Glatthorn and Randy, 2018 ; Kornuta and Germaine, 2019 ). Apart from thesis proposal instruction and guideline manuals posted on universities' websites, the authors believe that there is a lack of in-depth research on the issue of producing successful thesis proposals in the fields of Architecture and Planning.

To propose a successful TP conception which determines the standard components of TP and sets specific definitions, attributes and rules of success for each component.

To apply the proposed conception on several batches of graduate students, then assess its impact on students' performance and output along the years of application.

To validate the proposed conception by getting the insights of experienced academics from architecture and planning schools worldwide, and as such, improve and finalize the conception.

1.2 Research methodology

To propose the Successful TP Conception , the authors relied on two sources: knowledge extracted from their extended experience and a review of relevant studies and instruction manuals and guidelines for preparing TP in several worldwide universities. The Conception has been applied on several batches of master and doctoral students from IAU, KSA for almost 15 years between 2005 and 2020 during their enrolment in three courses in the College of Architecture and Planning, IAU, KSA. These courses are “ARPL 603 Research Methods” and “BISC 600 Research Methods” for the master's level and “URPL 803 Seminar (3): Doctoral Research Methods” for the doctoral level.

From a total of 60 students, 39 students (65%) completed the survey; of whom 12 students (31%) were doctoral and 27 students (69%) were masters students.

- Improve their understanding of the components of a successful TP.

- Enhance their performance in developing their TP's.

- Conduct a more effective self-assessment of their developed TP's.

- Enhance their performance along other stages of producing their theses and dissertations.

- Maintain any other benefits adding to students' research capabilities.

The first part recorded the general characteristics of respondents.

The second inquired about experts' viewpoints on the definitions, attributes and the rules of success of the components of the proposed TP conception.

2. Proposing the Successful TP Conception

2.1 components of a tp for a standard problem-solving research type.