Online Classes Vs. Traditional Classes Essay

Online vs. in-person classes essay – introduction, online and traditional classes differences, works cited.

The article compares and contrasts online classes and traditional classes. Among the advantages of online classes are flexibility and convenience, while in-person classes offer a more structured learning environment. The author highlights that online lessons can be more cost-effective, although they lack support provided by live interactions. Overall, the online vs. traditional classes essay is very relevant today, and the choice depends on the individual student’s needs and preferences.

Modern technology has infiltrated the education sector and as a result, many college students now prefer taking online classes, as opposed to attending the traditional regular classes. This is because online classes are convenient for such students, and more so for those who have to both work and attend classes.

As such, online learning gives them the flexibility that they needed. In addition, online learning also gives an opportunity to students and professionals who would not have otherwise gone back to school to get the necessary qualifications. However, students who have enrolled for online learning do not benefit from the one-on-one interaction with their peers and teachers. The essay shall endeavor to examine the differences between online classes and the traditional classes, with a preference for the later.

Online classes mainly take place through the internet. As such, online classes lack the regular student teacher interaction that is common with traditional learning. On the other hand, learning in traditional classes involves direct interaction between the student and the instructors (Donovan, Mader and Shinsky 286).

This is beneficial to both the leaner and the instructors because both can be bale to establish a bond. In addition, student attending the traditional classroom often have to adhere to strict guidelines that have been established by the learning institution. As such, students have to adhere to the established time schedules. On the other hand, students attending online classes can learn at their own time and pace.

One advantage of the traditional classes over online classes is that students who are not disciplined enough may not be able to sail through successfully because there is nobody to push them around. With traditional classes however, there are rules to put them in check. As such, students attending traditional classes are more likely to be committed to their education (Donovan et al 286).

Another advantage of the traditional classes is all the doubts that students might be having regarding a given course content can be cleared by the instructor on the spot, unlike online learning whereby such explanations might not be as coherent as the student would have wished.

With the traditional classes, students are rarely provided with the course materials by their instructors, and they are therefore expected to take their own notes. This is important because they are likely to preserve such note and use them later on in their studies. In contrast, online students are provided with course materials in the form of video or audio texts (Sorenson and Johnson 116).

They can also download such course materials online. Such learning materials can be deleted or lost easily compared with handwritten class notes, and this is a risk. Although the basic requirements for a student attending online classes are comparatively les in comparison to students attending traditional classes, nonetheless, it is important to note that online students are also expected to be internet savvy because all learning takes place online.

This would be a disadvantage for the regular student; only that internet savvy is not a requirement. Students undertaking online learning are likely to be withdrawn because they hardly interact one-on-one with their fellow online students or even their instructors. The only form of interaction is online. As such, it becomes hard for them to develop a special bond with other students and instructors. With traditional learning however, students have the freedom to interact freely and this helps to strengthen their existing bond.

Online learning is convenient and has less basic requirements compared with traditional learning. It also allows learners who would have ordinarily not gone back to school to access an education. However, online students do not benefit from a close interaction with their peers and instructors as do their regular counterparts. Also, regular students can engage their instructors more easily and relatively faster in case they want to have certain sections of the course explained, unlike online students.

Donovan, Judy, Mader, Cynthia and Shinsky, John. Constructive student feedback: Online vs. traditional course evaluations. Journal of Interactive Online Learning , 5.3(2006): 284-292.

Sorenson, Lynn, and Johnson, Trav. Online Student Ratings of Instructions . San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2003. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 28). Online Classes Vs. Traditional Classes Essay. https://ivypanda.com/essays/online-classes-vs-traditional-classes-essay/

"Online Classes Vs. Traditional Classes Essay." IvyPanda , 28 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/online-classes-vs-traditional-classes-essay/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Online Classes Vs. Traditional Classes Essay'. 28 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Online Classes Vs. Traditional Classes Essay." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/online-classes-vs-traditional-classes-essay/.

1. IvyPanda . "Online Classes Vs. Traditional Classes Essay." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/online-classes-vs-traditional-classes-essay/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Online Classes Vs. Traditional Classes Essay." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/online-classes-vs-traditional-classes-essay/.

- Technology Ruins One-on-One Interaction and Relations

- Remote vs In-person Classes: Positive and Negative Aspects

- Mathematics Teaching Approaches in Burns' Study

- The Impressions of Emirati Youths on ISIS

- Managers’ Training Proposal

- Coaching Approaches. Separation by Target and Source Data.

- Walmart Workplace Aspects Analysis

- The Value of In-Person Human Interaction

- Organizational Behavior and Workplace Conflicts

- Educator Ethics: The Case Study

- Principles Application in E-Learning

- Cambourne’s Conditions of Learning

- Concept of Transformative Learning in Modern Education

- Podcasts as an Education Tool

- Wikis as an Educational Tool

A Comparison of Student Learning Outcomes: Online Education vs. Traditional Classroom Instruction

Despite the prevalence of online learning today, it is often viewed as a less favorable option when compared to the traditional, in-person educational experience. Criticisms of online learning come from various sectors, like employer groups, college faculty, and the general public, and generally includes a lack of perceived quality as well as rigor. Additionally, some students report feelings of social isolation in online learning (Protopsaltis & Baum, 2019).

In my experience as an online student as well as an online educator, online learning has been just the opposite. I have been teaching in a fully online master’s degree program for the last three years and have found it to be a rich and rewarding experience for students and faculty alike. As an instructor, I have felt more connected to and engaged with my online students when compared to in-person students. I have also found that students are actively engaged with course content and demonstrate evidence of higher-order thinking through their work. Students report high levels of satisfaction with their experiences in online learning as well as the program overall as indicated in their Student Evaluations of Teaching (SET) at the end of every course. I believe that intelligent course design, in addition to my engagement in professional development related to teaching and learning online, has greatly influenced my experience.

In an article by Wiley Education Services, authors identified the top six challenges facing US institutions of higher education, and include:

- Declining student enrollment

- Financial difficulties

- Fewer high school graduates

- Decreased state funding

- Lower world rankings

- Declining international student enrollments

Of the strategies that institutions are exploring to remedy these issues, online learning is reported to be a key focus for many universities (“Top Challenges Facing US Higher Education”, n.d.).

Babson Survey Research Group, 2016, [PDF file].

Some of the questions I would like to explore in further research include:

- What factors influence engagement and connection in distance education?

- Are the learning outcomes in online education any different than the outcomes achieved in a traditional classroom setting?

- How do course design and instructor training influence these factors?

- In what ways might educational technology tools enhance the overall experience for students and instructors alike?

In this literature review, I have chosen to focus on a comparison of student learning outcomes in online education versus the traditional classroom setting. My hope is that this research will unlock the answers to some of the additional questions posed above and provide additional direction for future research.

Online Learning Defined

According to Mayadas, Miller, and Sener (2015), online courses are defined by all course activity taking place online with no required in-person sessions or on-campus activity. It is important to note, however, that the Babson Survey Research Group, a prominent organization known for their surveys and research in online learning, defines online learning as a course in which 80-100% occurs online. While this distinction was made in an effort to provide consistency in surveys year over year, most institutions continue to define online learning as learning that occurs 100% online.

Blended or hybrid learning is defined by courses that mix face to face meetings, sessions, or activities with online work. The ratio of online to classroom activity is often determined by the label in which the course is given. For example, a blended classroom course would likely include more time spent in the classroom, with the remaining work occurring outside of the classroom with the assistance of technology. On the other hand, a blended online course would contain a greater percentage of work done online, with some required in-person sessions or meetings (Mayadas, Miller, & Sener, 2015).

A classroom course (also referred to as a traditional course) refers to course activity that is anchored to a regular meeting time.

Enrollment Trends in Online Education

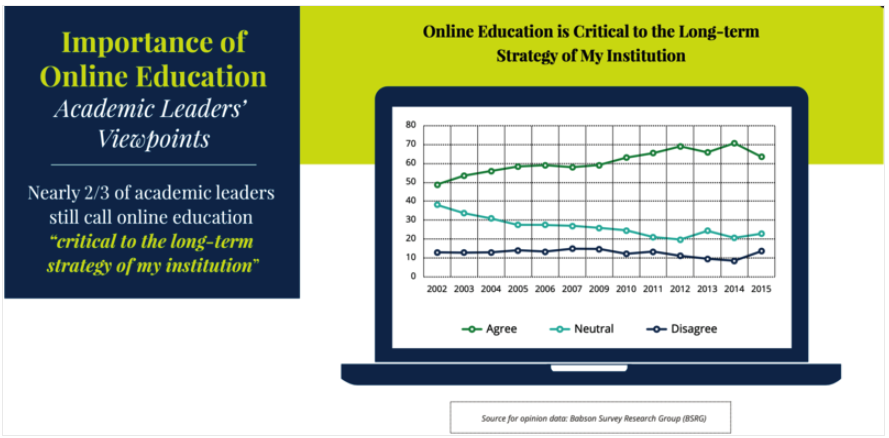

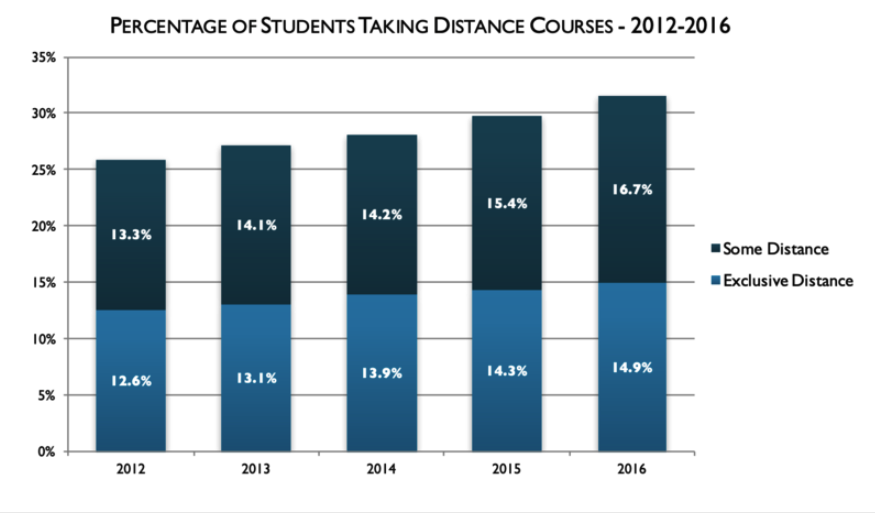

There has been an upward trend in the number of postsecondary students enrolled in online courses in the U.S. since 2002. A report by the Babson Survey Research Group showed that in 2016, more than six million students were enrolled in at least one online course. This number accounted for 31.6% of all college students (Seaman, Allen, & Seaman, 2018). Approximately one in three students are enrolled in online courses with no in-person component. Of these students, 47% take classes in a fully online program. The remaining 53% take some, but not all courses online (Protopsaltis & Baum, 2019).

(Seaman et al., 2016, p. 11)

Perceptions of Online Education

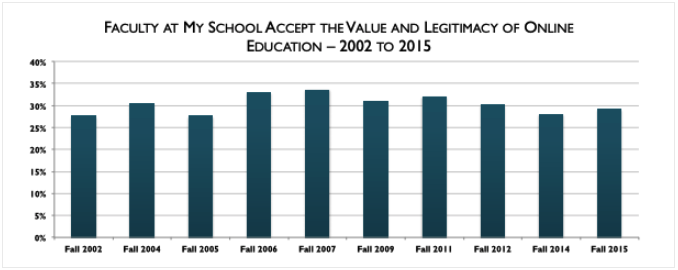

In a 2016 report by the Babson Survey Research Group, surveys of faculty between 2002-2015 showed approval ratings regarding the value and legitimacy of online education ranged from 28-34 percent. While numbers have increased and decreased over the thirteen-year time frame, faculty approval was at 29 percent in 2015, just 1 percent higher than the approval ratings noted in 2002 – indicating that perceptions have remained relatively unchanged over the years (Allen, Seaman, Poulin, & Straut, 2016).

(Allen, I.E., Seaman, J., Poulin, R., Taylor Strout, T., 2016, p. 26)

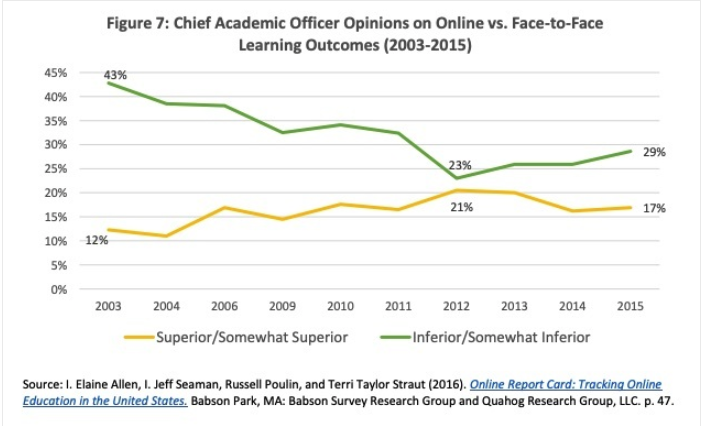

In a separate survey of chief academic officers, perceptions of online learning appeared to align with that of faculty. In this survey, leaders were asked to rate their perceived quality of learning outcomes in online learning when compared to traditional in-person settings. While the percentage of leaders rating online learning as “inferior” or “somewhat inferior” to traditional face-to-face courses dropped from 43 percent to 23 percent between 2003 to 2012, the number rose again to 29 percent in 2015 (Allen, Seaman, Poulin, & Straut, 2016).

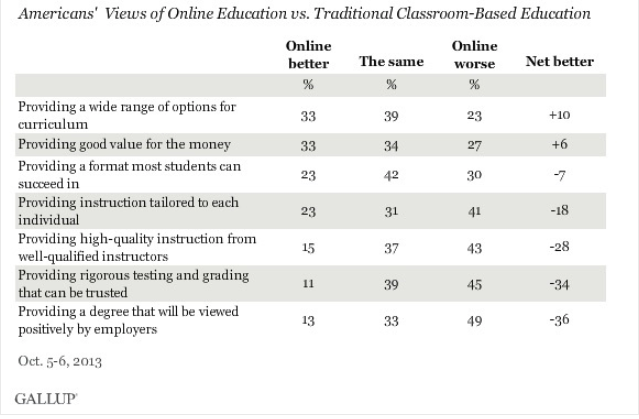

Faculty and academic leaders in higher education are not alone when it comes to perceptions of inferiority when compared to traditional classroom instruction. A 2013 Gallop poll assessing public perceptions showed that respondents rated online education as “worse” in five of the seven categories seen in the table below.

(Saad, L., Busteed, B., and Ogisi, M., 2013, October 15)

In general, Americans believed that online education provides both lower quality and less individualized instruction and less rigorous testing and grading when compared to the traditional classroom setting. In addition, respondents also thought that employers would perceive a degree from an online program less positively when compared to a degree obtained through traditional classroom instruction (Saad, Busteed, & Ogisi, 2013).

Student Perceptions of Online Learning

So what do students have to say about online learning? In Online College Students 2015: Comprehensive Data on Demands and Preferences, 1500 college students who were either enrolled or planning to enroll in a fully online undergraduate, graduate, or certificate program were surveyed. 78 percent of students believed the academic quality of their online learning experience to be better than or equal to their experiences with traditional classroom learning. Furthermore, 30 percent of online students polled said that they would likely not attend classes face to face if their program were not available online (Clienfelter & Aslanian, 2015). The following video describes some of the common reasons why students choose to attend college online.

How Online Learning Affects the Lives of Students ( Pearson North America, 2018, June 25)

In a 2015 study comparing student perceptions of online learning with face to face learning, researchers found that the majority of students surveyed expressed a preference for traditional face to face classes. A content analysis of the findings, however, brought attention to two key ideas: 1) student opinions of online learning may be based on “old typology of distance education” (Tichavsky, et al, 2015, p.6) as opposed to actual experience, and 2) a student’s inclination to choose one form over another is connected to issues of teaching presence and self-regulated learning (Tichavsky et al, 2015).

Student Learning Outcomes

Given the upward trend in student enrollment in online courses in postsecondary schools and the steady ratings of the low perceived value of online learning by stakeholder groups, it should be no surprise that there is a large body of literature comparing student learning outcomes in online classes to the traditional classroom environment.

While a majority of the studies reviewed found no significant difference in learning outcomes when comparing online to traditional courses (Cavanaugh & Jacquemin, 2015; Kemp & Grieve, 2014; Lyke & Frank 2012; Nichols, Shaffer, & Shockey, 2003; Stack, 2015; Summers, Waigandt, & Whittaker, 2005), there were a few outliers. In a 2019 report by Protopsaltis & Baum, authors confirmed that while learning is often found to be similar between the two mediums, students “with weak academic preparation and those from low-income and underrepresented backgrounds consistently underperform in fully-online environments” (Protopsaltis & Baum, 2019, n.p.). An important consideration, however, is that these findings are primarily based on students enrolled in online courses at the community college level – a demographic with a historically high rate of attrition compared to students attending four-year institutions (Ashby, Sadera, & McNary, 2011). Furthermore, students enrolled in online courses have been shown to have a 10 – 20 percent increase in attrition over their peers who are enrolled in traditional classroom instruction (Angelino, Williams, & Natvig, 2007). Therefore, attrition may be a key contributor to the lack of achievement seen in this subgroup of students enrolled in online education.

In contrast, there were a small number of studies that showed that online students tend to outperform those enrolled in traditional classroom instruction. One study, in particular, found a significant difference in test scores for students enrolled in an online, undergraduate business course. The confounding variable, in this case, was age. Researchers found a significant difference in performance in nontraditional age students over their traditional age counterparts. Authors concluded that older students may elect to take online classes for practical reasons related to outside work schedules, and this may, in turn, contribute to the learning that occurs overall (Slover & Mandernach, 2018).

In a meta-analysis and review of online learning spanning the years 1996 to 2008, authors from the US Department of Education found that students who took all or part of their classes online showed better learning outcomes than those students who took the same courses face-to-face. In these cases, it is important to note that there were many differences noted in the online and face-to-face versions, including the amount of time students spent engaged with course content. The authors concluded that the differences in learning outcomes may be attributed to learning design as opposed to the specific mode of delivery (Means, Toyoma, Murphy, Bakia, Jones, 2009).

Limitations and Opportunities

After examining the research comparing student learning outcomes in online education with the traditional classroom setting, there are many limitations that came to light, creating areas of opportunity for additional research. In many of the studies referenced, it is difficult to determine the pedagogical practices used in course design and delivery. Research shows the importance of student-student and student-teacher interaction in online learning, and the positive impact of these variables on student learning (Bernard, Borokhovski, Schmid, Tamim, & Abrami, 2014). Some researchers note that while many studies comparing online and traditional classroom learning exist, the methodologies and design issues make it challenging to explain the results conclusively (Mollenkopf, Vu, Crow, & Black, 2017). For example, some online courses may be structured in a variety of ways, i.e. self-paced, instructor-led and may be classified as synchronous or asynchronous (Moore, Dickson-Deane, Galyan, 2011)

Another gap in the literature is the failure to use a common language across studies to define the learning environment. This issue is explored extensively in a 2011 study by Moore, Dickson-Deane, and Galyan. Here, the authors examine the differences between e-learning, online learning, and distance learning in the literature, and how the terminology is often used interchangeably despite the variances in characteristics that define each. The authors also discuss the variability in the terms “course” versus “program”. This variability in the literature presents a challenge when attempting to compare one study of online learning to another (Moore, Dickson-Deane, & Galyan, 2011).

Finally, much of the literature in higher education focuses on undergraduate-level classes within the United States. Little research is available on outcomes in graduate-level classes as well as general information on student learning outcomes and perceptions of online learning outside of the U.S.

As we look to the future, there are additional questions to explore in the area of online learning. Overall, this research led to questions related to learning design when comparing the two modalities in higher education. Further research is needed to investigate the instructional strategies used to enhance student learning, especially in students with weaker academic preparation or from underrepresented backgrounds. Given the integral role that online learning is expected to play in the future of higher education in the United States, it may be even more critical to move beyond comparisons of online versus face to face. Instead, choosing to focus on sound pedagogical quality with consideration for the mode of delivery as a means for promoting positive learning outcomes.

Allen, I.E., Seaman, J., Poulin, R., & Straut, T. (2016). Online Report Card: Tracking Online Education in the United States [PDF file]. Babson Survey Research Group. http://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/onlinereportcard.pdf

Angelino, L. M., Williams, F. K., & Natvig, D. (2007). Strategies to engage online students and reduce attrition rates. The Journal of Educators Online , 4(2).

Ashby, J., Sadera, W.A., & McNary, S.W. (2011). Comparing student success between developmental math courses offered online, blended, and face-to-face. Journal of Interactive Online Learning , 10(3), 128-140.

Bernard, R.M., Borokhovski, E., Schmid, R.F., Tamim, R.M., & Abrami, P.C. (2014). A meta-analysis of blended learning and technology use in higher education: From the general to the applied. Journal of Computing in Higher Education , 26(1), 87-122.

Cavanaugh, J.K. & Jacquemin, S.J. (2015). A large sample comparison of grade based student learning outcomes in online vs. face-fo-face courses. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network, 19(2).

Clinefelter, D. L., & Aslanian, C. B. (2015). Online college students 2015: Comprehensive data on demands and preferences. https://www.learninghouse.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/OnlineCollegeStudents2015.pdf

Golubovskaya, E.A., Tikhonova, E.V., & Mekeko, N.M. (2019). Measuring learning outcome and students’ satisfaction in ELT (e-learning against conventional learning). Paper presented the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 34-38. Doi: 10.1145/3337682.3337704

Kemp, N. & Grieve, R. (2014). Face-to-face or face-to-screen? Undergraduates’ opinions and test performance in classroom vs. online learning. Frontiers in Psychology , 5. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01278

Lyke, J., & Frank, M. (2012). Comparison of student learning outcomes in online and traditional classroom environments in a psychology course. (Cover story). Journal of Instructional Psychology , 39(3/4), 245-250.

Mayadas, F., Miller, G. & Senner, J. Definitions of E-Learning Courses and Programs Version 2.0. Online Learning Consortium. https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/updated-e-learning-definitions-2/

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. US Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/tech/evidence-based-practices/finalreport.pdf

Mollenkopf, D., Vu, P., Crow, S, & Black, C. (2017). Does online learning deliver? A comparison of student teacher outcomes from candidates in face to face and online program pathways. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration. 20(1).

Moore, J.L., Dickson-Deane, C., & Galyan, K. (2011). E-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: Are they the same? The Internet and Higher Education . 14(2), 129-135.

Nichols, J., Shaffer, B., & Shockey, K. (2003). Changing the face of instruction: Is online or in-class more effective? College & Research Libraries , 64(5), 378–388. https://doi-org.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/10.5860/crl.64.5.378

Parsons-Pollard, N., Lacks, T.R., & Grant, P.H. (2008). A comparative assessment of student learning outcomes in large online and traditional campus based introduction to criminal justice courses. Criminal Justice Studies , 2, 225-239.

Pearson North America. (2018, June 25). How Online Learning Affects the Lives of Students . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPDMagf_oAE

Protopsaltis, S., & Baum, S. (2019). Does online education live up to its promise? A look at the evidence and implications for federal policy [PDF file]. http://mason.gmu.edu/~sprotops/OnlineEd.pdf

Saad, L., Busteed, B., & Ogisi, M. (October 15, 2013). In U.S., Online Education Rated Best for Value and Options. https://news.gallup.com/poll/165425/online-education-rated-best-value-options.aspx

Stack, S. (2015). Learning Outcomes in an Online vs Traditional Course. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning , 9(1).

Seaman, J.E., Allen, I.E., & Seaman, J. (2018). Grade Increase: Tracking Distance Education in the United States [PDF file]. Babson Survey Research Group. http://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/gradeincrease.pdf

Slover, E. & Mandernach, J. (2018). Beyond Online versus Face-to-Face Comparisons: The Interaction of Student Age and Mode of Instruction on Academic Achievement. Journal of Educators Online, 15(1) . https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1168945.pdf

Summers, J., Waigandt, A., & Whittaker, T. (2005). A Comparison of Student Achievement and Satisfaction in an Online Versus a Traditional Face-to-Face Statistics Class. Innovative Higher Education , 29(3), 233–250. https://doi-org.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/10.1007/s10755-005-1938-x

Tichavsky, L.P., Hunt, A., Driscoll, A., & Jicha, K. (2015). “It’s just nice having a real teacher”: Student perceptions of online versus face-to-face instruction. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. 9(2).

Wiley Education Services. (n.d.). Top challenges facing U.S. higher education. https://edservices.wiley.com/top-higher-education-challenges/

July 17, 2020

Online Learning

college , distance education , distance learning , face to face , higher education , online learning , postsecondary , traditional learning , university , virtual learning

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

© 2024 — Powered by WordPress

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Look Who’s Talking About Online vs. Traditional Education

Any student considering taking courses online who has never done so before may understandably have some trepidation. Is an online course really going to give you the experience and knowledge that you need to pursue the degree — and eventually career — that you want?

Luckily, we are no longer sitting at the starting gate with online learning. With more than 20 years of research available, it is much easier today to assess the impact of online learning on the learning experience, as well as the comparative learning outcomes for students that take an online path versus a more traditional one.

The following experts in learning methodology and online education have taken the time to research, write and publish their own findings. Each is employed by a university, most are full-time professors, though adjunct faculty are also represented.

Meet the Experts

The college learning experience extends far beyond what students may learn in a course. In fact, from one perspective, college as much about learning how to learn and how to think critically as it is about the actual substance of the courses themselves. Because of the importance of the critical thinking aspect and how that process is often supported by interaction between students and faculty, one of the criticisms levied against online education is that it makes these interactions more difficult.

In his piece for the International Journal of E-learning and Distance Education , Dr. Mark Bullen sets out to analyze one particular online course to determine:

- whether the students were actively participating, building on each other’s contributions, and thinking critically about the discussion topics; and

- what factors affected student participation and critical thinking

The conclusions of this study, which had a very small sample size, was that students’ discussions in the online course for the most part did not build upon one another, with most students adding comments that were independent from those of their classmates.

It is important to note that Dr. Bullen undertook this study in the nascent stages of online education with what would be very remedial technology in comparison to what is in use today. Advances such as live chat features, video conferencing, and “threaded” forums and discussion areas may all help facilitate interaction between students and faculty. Further, the instructor of the courses noted that “he might have been able to stimulate some discussion if he had taken a more active role, challenging students to elaborate their positions and to compare them with those of other students.”

Dr. Bullen has a Ph.D. in Adult Education, a Master’s degree in Educational Psychology and a B.Ed. from the University of British Columbia. He was also the Chief Editor of the Journal of Distance Education from 2006 to 2012.

Participation and Critical Thinking in Online University Distance Education

In the journal Quest , Drs. Gregg Bennett and Frederick P. Green undertake a thorough review of the available research on the phenomenon of online education as it compares to traditional classroom-based courses. The article identifies three key factors that collectively determine whether students in online and traditional learning environments will achieve the same outcomes: the instructor, the students, and the tools used for the course. Although the technology (such as the Learning Management System, or LMS) does play a role, it is only a well-designed course with a dedicated instructor and students who are motivated to learn that will, together, determine the success of an online program. Drs. Bennett and Green also find that collaboration, convenience, and easy access to additional resources are benefits that give online courses an advantage. The takeaway from the analysis as a whole is that with the right instruction — and the right students — it is possible to conduct courses online just as successfully as in a more traditional setting.

Dr. Bennett currently serves as a Professor of Health & Kinesiology at Texas A&M University where he was awarded the 2010 ING Professor of Excellence, while Dr. Green continues his scholarship focus on the relationship between leisure, leisure lifestyle and the community inclusion of marginalized groups at the University of Southern Mississippi.

Student Learning in the Online Environment: No Significant Difference?

Dr. Jennifer Jill Harman is an Associate Professor in the Psychology department at Colorado State University. In that role, she has written about the process of developing and teaching online courses from a personal perspective. Having taught in classrooms for more than 15 years, Dr. Harman was at first skeptical about the possibility of translating her rigorous psychology coursework to an online platform. However, with the right tools, she was able to create online courses that provided comparable learning outcomes and that, by their online nature, were accessible to more students. Dr. Harman was even able to incorporate counseling skills into her courses through the use of video conferencing tools like Skype and Google Hangouts.

Dr. Harman holds a PhD in Psychology from the University of Connecticut and has published work in the Journal of Family Psychology and Children & Youth Services Review , among others.

Online Versus Traditional Education: Is One Better Than the Other?

In the International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, Dr. Steven Stack has written about how learning outcomes differ in online and traditional educational settings. The study that Dr. Stack uses is particularly interesting because, unlike most other online learning studies, students were not able to choose whether or not they took an online or classroom course, due to an error in the course selection process. Therefore, a set of students took the same class with the same instructor, with some online and some in the classroom. The data from this study, which used 64 total students with a nearly balanced gender ratio, found that both sections of the course performed largely the same, with the online students outperforming the traditional students just slightly. Further, when students were asked to evaluate the course, the two sets gave nearly identical ratings for how much they learned and how they would rate the instructor.

Because of the unique “blind selection” data for this study, it is fascinating to note that the course delivery method, with the same instructor and the same materials, made little to no difference in how students perceived the course or how they performed on exams.

Dr. Stack continues to work as a Professor in the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Wayne State University, where his research interests include Social risk and protective factors for suicide, Cultural Axes of Nations and link to Public Opinion on Criminality and Deviance, and the impact of the death penalty on homicide.

Learning Outcomes in an Online vs Traditional Course

In the International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, Dr. Yuliang Liu directly addresses the idea of how well students learn in an online environment as opposed to a traditional classroom setting.

Unlike the study that Dr. Sacks published, Dr. Liu used self-selected students at a midwestern university for his analysis. Subjects in one online and one traditional course, using the same learning objectives, were given pretests and posttests to assess their learning, as well as quizzes throughout the course. The results of the study found that online students did measurably better on quizzes and in the course overall and had fewer complaints about the course. In fact, Dr. Liu concludes that “online instruction can be a viable alternative for higher education.”

Dr. Liu holds a PhD in Educational Psychology from Texas A&M University in Commerce. Prior to joining the faculty at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, he taught both graduate and undergraduate courses both in classrooms and online at Southeastern Oklahoma State University.

Effects of Online Instruction vs. Traditional Instruction on Students’ Learning

In the Journal of Online Learning and Teaching (JOLT), Dr. Maureen Hannay and Tracy Newvine conducted a study to assess student perceptions of their online learning experiences as compared to classroom courses. The study surveyed 217 students, most of whom were adults taking courses part-time and found that by and large, this student population preferred online learning and felt they were able to achieve more in an online environment. Students noted the convenience of online learning and being able to balance school with other commitments, something that is a great importance to part-time students. 59% of respondents reports achieving higher grades in their online courses while 57% indicated that they learned more in the online setting.

While this questionnaire may not hold all the answers to online vs. traditional education, it is certainly important to consider the views of students who have experienced both formats.

Dr. Hannay holds a Ph.D. in Industrial Relations and Human Resource Management from the University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada and is a Professor of Management at Troy University while Tracy Newvine is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Criminal Justice at Troy University – Global.

Perceptions of Distance Learning: A Comparison of Online and Traditional Learning

In another article from JOLT, Dr. Cindy Ann Dell, Christy Low, and Dr. Jeanine F. Wilker analyze student results from online and traditional sections of the same courses. Rather than relying on tests and student reporting, this analysis looks directly at the work handed in for the different courses and compares the quality. The study looked at both graduate and undergraduate courses, using different assignments for each analysis.

Ultimately, this study found that the quality of work turned in was not significantly different for the online and traditional courses. Rather, the more important indicator of student success was method of instruction that the teacher chose. The study concludes that: “There are a few pedagogical variables that can have an influence including (1) the use of problem-based learning strategies, (2) the opportunity for students to engage in mediated communication with the instructor, (3) course and content information provided to students prior to class starting, (4) and the use of video provided to students by the instructor, to name a few. ”

It can be easy to get weighed down in the technological specifics of online learning, but what this analysis shows is that any instructor can excel in the online space with the right resources and attention to methodology.

Dr. Cindy Ann Dell holds an EdD in Adult and Higher Education from Montana University at Bozeman while Dr. Jeanine F. Wilker holds her PhD in Education with a specialization in Professional Studies from Capella University. Christy Low currently works as an Instructional Designer at Old Dominion University.

Comparing Student Achievement in Online and Face-to-Face Class Formats

Guide to Online Education

- Expert Advice for Online Students

- Frequently Asked Questions About Online Education

- Instructional Design in Online Programs

- Learning Management Systems

- Online Student Trends and Success Factors

- Online Teaching Methods

- Student Guide to Understanding and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Student Services for Online Learners

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Online and face‐to‐face learning: Evidence from students’ performance during the Covid‐19 pandemic

Carolyn chisadza.

1 Department of Economics, University of Pretoria, Hatfield South Africa

Matthew Clance

Thulani mthembu.

2 Department of Education Innovation, University of Pretoria, Hatfield South Africa

Nicky Nicholls

Eleni yitbarek.

This study investigates the factors that predict students' performance after transitioning from face‐to‐face to online learning as a result of the Covid‐19 pandemic. It uses students' responses from survey questions and the difference in the average assessment grades between pre‐lockdown and post‐lockdown at a South African university. We find that students' performance was positively associated with good wifi access, relative to using mobile internet data. We also observe lower academic performance for students who found transitioning to online difficult and who expressed a preference for self‐study (i.e. reading through class slides and notes) over assisted study (i.e. joining live lectures or watching recorded lectures). The findings suggest that improving digital infrastructure and reducing the cost of internet access may be necessary for mitigating the impact of the Covid‐19 pandemic on education outcomes.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Covid‐19 pandemic has been a wake‐up call to many countries regarding their capacity to cater for mass online education. This situation has been further complicated in developing countries, such as South Africa, who lack the digital infrastructure for the majority of the population. The extended lockdown in South Africa saw most of the universities with mainly in‐person teaching scrambling to source hardware (e.g. laptops, internet access), software (e.g. Microsoft packages, data analysis packages) and internet data for disadvantaged students in order for the semester to recommence. Not only has the pandemic revealed the already stark inequality within the tertiary student population, but it has also revealed that high internet data costs in South Africa may perpetuate this inequality, making online education relatively inaccessible for disadvantaged students. 1

The lockdown in South Africa made it possible to investigate the changes in second‐year students' performance in the Economics department at the University of Pretoria. In particular, we are interested in assessing what factors predict changes in students' performance after transitioning from face‐to‐face (F2F) to online learning. Our main objectives in answering this study question are to establish what study materials the students were able to access (i.e. slides, recordings, or live sessions) and how students got access to these materials (i.e. the infrastructure they used).

The benefits of education on economic development are well established in the literature (Gyimah‐Brempong, 2011 ), ranging from health awareness (Glick et al., 2009 ), improved technological innovations, to increased capacity development and employment opportunities for the youth (Anyanwu, 2013 ; Emediegwu, 2021 ). One of the ways in which inequality is perpetuated in South Africa, and Africa as a whole, is through access to education (Anyanwu, 2016 ; Coetzee, 2014 ; Tchamyou et al., 2019 ); therefore, understanding the obstacles that students face in transitioning to online learning can be helpful in ensuring more equal access to education.

Using students' responses from survey questions and the difference in the average grades between pre‐lockdown and post‐lockdown, our findings indicate that students' performance in the online setting was positively associated with better internet access. Accessing assisted study material, such as narrated slides or recordings of the online lectures, also helped students. We also find lower academic performance for students who reported finding transitioning to online difficult and for those who expressed a preference for self‐study (i.e. reading through class slides and notes) over assisted study (i.e. joining live lectures or watching recorded lectures). The average grades between pre‐lockdown and post‐lockdown were about two points and three points lower for those who reported transitioning to online teaching difficult and for those who indicated a preference for self‐study, respectively. The findings suggest that improving the quality of internet infrastructure and providing assisted learning can be beneficial in reducing the adverse effects of the Covid‐19 pandemic on learning outcomes.

Our study contributes to the literature by examining the changes in the online (post‐lockdown) performance of students and their F2F (pre‐lockdown) performance. This approach differs from previous studies that, in most cases, use between‐subject designs where one group of students following online learning is compared to a different group of students attending F2F lectures (Almatra et al., 2015 ; Brown & Liedholm, 2002 ). This approach has a limitation in that that there may be unobserved characteristics unique to students choosing online learning that differ from those choosing F2F lectures. Our approach avoids this issue because we use a within‐subject design: we compare the performance of the same students who followed F2F learning Before lockdown and moved to online learning during lockdown due to the Covid‐19 pandemic. Moreover, the study contributes to the limited literature that compares F2F and online learning in developing countries.

Several studies that have also compared the effectiveness of online learning and F2F classes encounter methodological weaknesses, such as small samples, not controlling for demographic characteristics, and substantial differences in course materials and assessments between online and F2F contexts. To address these shortcomings, our study is based on a relatively large sample of students and includes demographic characteristics such as age, gender and perceived family income classification. The lecturer and course materials also remained similar in the online and F2F contexts. A significant proportion of our students indicated that they never had online learning experience before. Less than 20% of the students in the sample had previous experience with online learning. This highlights the fact that online education is still relatively new to most students in our sample.

Given the global experience of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR), 2 with rapidly accelerating technological progress, South Africa needs to be prepared for the possibility of online learning becoming the new norm in the education system. To this end, policymakers may consider engaging with various organizations (schools, universities, colleges, private sector, and research facilities) To adopt interventions that may facilitate the transition to online learning, while at the same time ensuring fair access to education for all students across different income levels. 3

1.1. Related literature

Online learning is a form of distance education which mainly involves internet‐based education where courses are offered synchronously (i.e. live sessions online) and/or asynchronously (i.e. students access course materials online in their own time, which is associated with the more traditional distance education). On the other hand, traditional F2F learning is real time or synchronous learning. In a physical classroom, instructors engage with the students in real time, while in the online format instructors can offer real time lectures through learning management systems (e.g. Blackboard Collaborate), or record the lectures for the students to watch later. Purely online courses are offered entirely over the internet, while blended learning combines traditional F2F classes with learning over the internet, and learning supported by other technologies (Nguyen, 2015 ).

Moreover, designing online courses requires several considerations. For example, the quality of the learning environment, the ease of using the learning platform, the learning outcomes to be achieved, instructor support to assist and motivate students to engage with the course material, peer interaction, class participation, type of assessments (Paechter & Maier, 2010 ), not to mention training of the instructor in adopting and introducing new teaching methods online (Lundberg et al., 2008 ). In online learning, instructors are more facilitators of learning. On the other hand, traditional F2F classes are structured in such a way that the instructor delivers knowledge, is better able to gauge understanding and interest of students, can engage in class activities, and can provide immediate feedback on clarifying questions during the class. Additionally, the designing of traditional F2F courses can be less time consuming for instructors compared to online courses (Navarro, 2000 ).

Online learning is also particularly suited for nontraditional students who require flexibility due to work or family commitments that are not usually associated with the undergraduate student population (Arias et al., 2018 ). Initially the nontraditional student belonged to the older adult age group, but with blended learning becoming more commonplace in high schools, colleges and universities, online learning has begun to traverse a wider range of age groups. However, traditional F2F classes are still more beneficial for learners that are not so self‐sufficient and lack discipline in working through the class material in the required time frame (Arias et al., 2018 ).

For the purpose of this literature review, both pure online and blended learning are considered to be online learning because much of the evidence in the literature compares these two types against the traditional F2F learning. The debate in the literature surrounding online learning versus F2F teaching continues to be a contentious one. A review of the literature reveals mixed findings when comparing the efficacy of online learning on student performance in relation to the traditional F2F medium of instruction (Lundberg et al., 2008 ; Nguyen, 2015 ). A number of studies conducted Before the 2000s find what is known today in the empirical literature as the “No Significant Difference” phenomenon (Russell & International Distance Education Certificate Center (IDECC), 1999 ). The seminal work from Russell and IDECC ( 1999 ) involved over 350 comparative studies on online/distance learning versus F2F learning, dating back to 1928. The author finds no significant difference overall between online and traditional F2F classroom education outcomes. Subsequent studies that followed find similar “no significant difference” outcomes (Arbaugh, 2000 ; Fallah & Ubell, 2000 ; Freeman & Capper, 1999 ; Johnson et al., 2000 ; Neuhauser, 2002 ). While Bernard et al. ( 2004 ) also find that overall there is no significant difference in achievement between online education and F2F education, the study does find significant heterogeneity in student performance for different activities. The findings show that students in F2F classes outperform the students participating in synchronous online classes (i.e. classes that require online students to participate in live sessions at specific times). However, asynchronous online classes (i.e. students access class materials at their own time online) outperform F2F classes.

More recent studies find significant results for online learning outcomes in relation to F2F outcomes. On the one hand, Shachar and Yoram ( 2003 ) and Shachar and Neumann ( 2010 ) conduct a meta‐analysis of studies from 1990 to 2009 and find that in 70% of the cases, students taking courses by online education outperformed students in traditionally instructed courses (i.e. F2F lectures). In addition, Navarro and Shoemaker ( 2000 ) observe that learning outcomes for online learners are as effective as or better than outcomes for F2F learners, regardless of background characteristics. In a study on computer science students, Dutton et al. ( 2002 ) find online students perform significantly better compared to the students who take the same course on campus. A meta‐analysis conducted by the US Department of Education finds that students who took all or part of their course online performed better, on average, than those taking the same course through traditional F2F instructions. The report also finds that the effect sizes are larger for studies in which the online learning was collaborative or instructor‐driven than in those studies where online learners worked independently (Means et al., 2010 ).

On the other hand, evidence by Brown and Liedholm ( 2002 ) based on test scores from macroeconomics students in the United States suggest that F2F students tend to outperform online students. These findings are supported by Coates et al. ( 2004 ) who base their study on macroeconomics students in the United States, and Xu and Jaggars ( 2014 ) who find negative effects for online students using a data set of about 500,000 courses taken by over 40,000 students in Washington. Furthermore, Almatra et al. ( 2015 ) compare overall course grades between online and F2F students for a Telecommunications course and find that F2F students significantly outperform online learning students. In an experimental study where students are randomly assigned to attend live lectures versus watching the same lectures online, Figlio et al. ( 2013 ) observe some evidence that the traditional format has a positive effect compared to online format. Interestingly, Callister and Love ( 2016 ) specifically compare the learning outcomes of online versus F2F skills‐based courses and find that F2F learners earned better outcomes than online learners even when using the same technology. This study highlights that some of the inconsistencies that we find in the results comparing online to F2F learning might be influenced by the nature of the course: theory‐based courses might be less impacted by in‐person interaction than skills‐based courses.

The fact that the reviewed studies on the effects of F2F versus online learning on student performance have been mainly focused in developed countries indicates the dearth of similar studies being conducted in developing countries. This gap in the literature may also highlight a salient point: online learning is still relatively underexplored in developing countries. The lockdown in South Africa therefore provides us with an opportunity to contribute to the existing literature from a developing country context.

2. CONTEXT OF STUDY

South Africa went into national lockdown in March 2020 due to the Covid‐19 pandemic. Like most universities in the country, the first semester for undergraduate courses at the University of Pretoria had already been running since the start of the academic year in February. Before the pandemic, a number of F2F lectures and assessments had already been conducted in most courses. The nationwide lockdown forced the university, which was mainly in‐person teaching, to move to full online learning for the remainder of the semester. This forced shift from F2F teaching to online learning allows us to investigate the changes in students' performance.

Before lockdown, classes were conducted on campus. During lockdown, these live classes were moved to an online platform, Blackboard Collaborate, which could be accessed by all registered students on the university intranet (“ClickUP”). However, these live online lectures involve substantial internet data costs for students. To ensure access to course content for those students who were unable to attend the live online lectures due to poor internet connections or internet data costs, several options for accessing course content were made available. These options included prerecorded narrated slides (which required less usage of internet data), recordings of the live online lectures, PowerPoint slides with explanatory notes and standard PDF lecture slides.

At the same time, the university managed to procure and loan out laptops to a number of disadvantaged students, and negotiated with major mobile internet data providers in the country for students to have free access to study material through the university's “connect” website (also referred to as the zero‐rated website). However, this free access excluded some video content and live online lectures (see Table 1 ). The university also provided between 10 and 20 gigabytes of mobile internet data per month, depending on the network provider, sent to students' mobile phones to assist with internet data costs.

Sites available on zero‐rated website

Note : The table summarizes the sites that were available on the zero‐rated website and those that incurred data costs.

High data costs continue to be a contentious issue in Africa where average incomes are low. Gilbert ( 2019 ) reports that South Africa ranked 16th of the 45 countries researched in terms of the most expensive internet data in Africa, at US$6.81 per gigabyte, in comparison to other Southern African countries such as Mozambique (US$1.97), Zambia (US$2.70), and Lesotho (US$4.09). Internet data prices have also been called into question in South Africa after the Competition Commission published a report from its Data Services Market Inquiry calling the country's internet data pricing “excessive” (Gilbert, 2019 ).

3. EMPIRICAL APPROACH

We use a sample of 395 s‐year students taking a macroeconomics module in the Economics department to compare the effects of F2F and online learning on students' performance using a range of assessments. The module was an introduction to the application of theoretical economic concepts. The content was both theory‐based (developing economic growth models using concepts and equations) and skill‐based (application involving the collection of data from online data sources and analyzing the data using statistical software). Both individual and group assignments formed part of the assessments. Before the end of the semester, during lockdown in June 2020, we asked the students to complete a survey with questions related to the transition from F2F to online learning and the difficulties that they may have faced. For example, we asked the students: (i) how easy or difficult they found the transition from F2F to online lectures; (ii) what internet options were available to them and which they used the most to access the online prescribed work; (iii) what format of content they accessed and which they preferred the most (i.e. self‐study material in the form of PDF and PowerPoint slides with notes vs. assisted study with narrated slides and lecture recordings); (iv) what difficulties they faced accessing the live online lectures, to name a few. Figure 1 summarizes the key survey questions that we asked the students regarding their transition from F2F to online learning.

Summary of survey data

Before the lockdown, the students had already attended several F2F classes and completed three assessments. We are therefore able to create a dependent variable that is comprised of the average grades of three assignments taken before lockdown and the average grades of three assignments taken after the start of the lockdown for each student. Specifically, we use the difference between the post‐ and pre‐lockdown average grades as the dependent variable. However, the number of student observations dropped to 275 due to some students missing one or more of the assessments. The lecturer, content and format of the assessments remain similar across the module. We estimate the following equation using ordinary least squares (OLS) with robust standard errors:

where Y i is the student's performance measured by the difference between the post and pre‐lockdown average grades. B represents the vector of determinants that measure the difficulty faced by students to transition from F2F to online learning. This vector includes access to the internet, study material preferred, quality of the online live lecture sessions and pre‐lockdown class attendance. X is the vector of student demographic controls such as race, gender and an indicator if the student's perceived family income is below average. The ε i is unobserved student characteristics.

4. ANALYSIS

4.1. descriptive statistics.

Table 2 gives an overview of the sample of students. We find that among the black students, a higher proportion of students reported finding the transition to online learning more difficult. On the other hand, more white students reported finding the transition moderately easy, as did the other races. According to Coetzee ( 2014 ), the quality of schools can vary significantly between higher income and lower‐income areas, with black South Africans far more likely to live in lower‐income areas with lower quality schools than white South Africans. As such, these differences in quality of education from secondary schooling can persist at tertiary level. Furthermore, persistent income inequality between races in South Africa likely means that many poorer black students might not be able to afford wifi connections or large internet data bundles which can make the transition difficult for black students compared to their white counterparts.

Descriptive statistics

Notes : The transition difficulty variable was ordered 1: Very Easy; 2: Moderately Easy; 3: Difficult; and 4: Impossible. Since we have few responses to the extremes, we combined Very Easy and Moderately as well as Difficult and Impossible to make the table easier to read. The table with a full breakdown is available upon request.

A higher proportion of students reported that wifi access made the transition to online learning moderately easy. However, relatively more students reported that mobile internet data and accessing the zero‐rated website made the transition difficult. Surprisingly, not many students made use of the zero‐rated website which was freely available. Figure 2 shows that students who reported difficulty transitioning to online learning did not perform as well in online learning versus F2F when compared to those that found it less difficult to transition.

Transition from F2F to online learning.

Notes : This graph shows the students' responses to the question “How easy did you find the transition from face‐to‐face lectures to online lectures?” in relation to the outcome variable for performance

In Figure 3 , the kernel density shows that students who had access to wifi performed better than those who used mobile internet data or the zero‐rated data.

Access to online learning.

Notes : This graph shows the students' responses to the question “What do you currently use the most to access most of your prescribed work?” in relation to the outcome variable for performance

The regression results are reported in Table 3 . We find that the change in students' performance from F2F to online is negatively associated with the difficulty they faced in transitioning from F2F to online learning. According to student survey responses, factors contributing to difficulty in transitioning included poor internet access, high internet data costs and lack of equipment such as laptops or tablets to access the study materials on the university website. Students who had access to wifi (i.e. fixed wireless broadband, Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Line (ADSL) or optic fiber) performed significantly better, with on average 4.5 points higher grade, in relation to students that had to use mobile internet data (i.e. personal mobile internet data, wifi at home using mobile internet data, or hotspot using mobile internet data) or the zero‐rated website to access the study materials. The insignificant results for the zero‐rated website are surprising given that the website was freely available and did not incur any internet data costs. However, most students in this sample complained that the internet connection on the zero‐rated website was slow, especially in uploading assignments. They also complained about being disconnected when they were in the middle of an assessment. This may have discouraged some students from making use of the zero‐rated website.

Results: Predictors for student performance using the difference on average assessment grades between pre‐ and post‐lockdown

Coefficients reported. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

∗∗∗ p < .01.

Students who expressed a preference for self‐study approaches (i.e. reading PDF slides or PowerPoint slides with explanatory notes) did not perform as well, on average, as students who preferred assisted study (i.e. listening to recorded narrated slides or lecture recordings). This result is in line with Means et al. ( 2010 ), where student performance was better for online learning that was collaborative or instructor‐driven than in cases where online learners worked independently. Interestingly, we also observe that the performance of students who often attended in‐person classes before the lockdown decreased. Perhaps these students found the F2F lectures particularly helpful in mastering the course material. From the survey responses, we find that a significant proportion of the students (about 70%) preferred F2F to online lectures. This preference for F2F lectures may also be linked to the factors contributing to the difficulty some students faced in transitioning to online learning.

We find that the performance of low‐income students decreased post‐lockdown, which highlights another potential challenge to transitioning to online learning. The picture and sound quality of the live online lectures also contributed to lower performance. Although this result is not statistically significant, it is worth noting as the implications are linked to the quality of infrastructure currently available for students to access online learning. We find no significant effects of race on changes in students' performance, though males appeared to struggle more with the shift to online teaching than females.

For the robustness check in Table 4 , we consider the average grades of the three assignments taken after the start of the lockdown as a dependent variable (i.e. the post‐lockdown average grades for each student). We then include the pre‐lockdown average grades as an explanatory variable. The findings and overall conclusions in Table 4 are consistent with the previous results.

Robustness check: Predictors for student performance using the average assessment grades for post‐lockdown

As a further robustness check in Table 5 , we create a panel for each student across the six assignment grades so we can control for individual heterogeneity. We create a post‐lockdown binary variable that takes the value of 1 for the lockdown period and 0 otherwise. We interact the post‐lockdown dummy variable with a measure for transition difficulty and internet access. The internet access variable is an indicator variable for mobile internet data, wifi, or zero‐rated access to class materials. The variable wifi is a binary variable taking the value of 1 if the student has access to wifi and 0 otherwise. The zero‐rated variable is a binary variable taking the value of 1 if the student used the university's free portal access and 0 otherwise. We also include assignment and student fixed effects. The results in Table 5 remain consistent with our previous findings that students who had wifi access performed significantly better than their peers.

Interaction model

Notes : Coefficients reported. Robust standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable is the assessment grades for each student on each assignment. The number of observations include the pre‐post number of assessments multiplied by the number of students.

6. CONCLUSION

The Covid‐19 pandemic left many education institutions with no option but to transition to online learning. The University of Pretoria was no exception. We examine the effect of transitioning to online learning on the academic performance of second‐year economic students. We use assessment results from F2F lectures before lockdown, and online lectures post lockdown for the same group of students, together with responses from survey questions. We find that the main contributor to lower academic performance in the online setting was poor internet access, which made transitioning to online learning more difficult. In addition, opting to self‐study (read notes instead of joining online classes and/or watching recordings) did not help the students in their performance.

The implications of the results highlight the need for improved quality of internet infrastructure with affordable internet data pricing. Despite the university's best efforts not to leave any student behind with the zero‐rated website and free monthly internet data, the inequality dynamics in the country are such that invariably some students were negatively affected by this transition, not because the student was struggling academically, but because of inaccessibility of internet (wifi). While the zero‐rated website is a good collaborative initiative between universities and network providers, the infrastructure is not sufficient to accommodate mass students accessing it simultaneously.

This study's findings may highlight some shortcomings in the academic sector that need to be addressed by both the public and private sectors. There is potential for an increase in the digital divide gap resulting from the inequitable distribution of digital infrastructure. This may lead to reinforcement of current inequalities in accessing higher education in the long term. To prepare the country for online learning, some considerations might need to be made to make internet data tariffs more affordable and internet accessible to all. We hope that this study's findings will provide a platform (or will at least start the conversation for taking remedial action) for policy engagements in this regard.

We are aware of some limitations presented by our study. The sample we have at hand makes it difficult to extrapolate our findings to either all students at the University of Pretoria or other higher education students in South Africa. Despite this limitation, our findings highlight the negative effect of the digital divide on students' educational outcomes in the country. The transition to online learning and the high internet data costs in South Africa can also have adverse learning outcomes for low‐income students. With higher education institutions, such as the University of Pretoria, integrating online teaching to overcome the effect of the Covid‐19 pandemic, access to stable internet is vital for students' academic success.

It is also important to note that the data we have at hand does not allow us to isolate wifi's causal effect on students' performance post‐lockdown due to two main reasons. First, wifi access is not randomly assigned; for instance, there is a high chance that students with better‐off family backgrounds might have better access to wifi and other supplementary infrastructure than their poor counterparts. Second, due to the university's data access policy and consent, we could not merge the data at hand with the student's previous year's performance. Therefore, future research might involve examining the importance of these elements to document the causal impact of access to wifi on students' educational outcomes in the country.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the helpful comments received from the editor, the anonymous reviewers, and Elizabeth Asiedu.

Chisadza, C. , Clance, M. , Mthembu, T. , Nicholls, N. , & Yitbarek, E. (2021). Online and face‐to‐face learning: Evidence from students’ performance during the Covid‐19 pandemic . Afr Dev Rev , 33 , S114–S125. 10.1111/afdr.12520 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

1 https://mybroadband.co.za/news/cellular/309693-mobile-data-prices-south-africa-vs-the-world.html .

2 The 4IR is currently characterized by increased use of new technologies, such as advanced wireless technologies, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, robotics, among others. This era has also facilitated the use of different online learning platforms ( https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-fourth-industrialrevolution-and-digitization-will-transform-africa-into-a-global-powerhouse/ ).

3 Note that we control for income, but it is plausible to assume other unobservable factors such as parental preference and parenting style might also affect access to the internet of students.

- Almatra, O. , Johri, A. , Nagappan, K. , & Modanlu, A. (2015). An empirical study of face‐to‐face and distance learning sections of a core telecommunication course (Conference Proceedings Paper No. 12944). 122nd ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Seattle, Washington State.

- Anyanwu, J. C. (2013). Characteristics and macroeconomic determinants of youth employment in Africa . African Development Review , 25 ( 2 ), 107–129. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anyanwu, J. C. (2016). Accounting for gender equality in secondary school enrolment in Africa: Accounting for gender equality in secondary school enrolment . African Development Review , 28 ( 2 ), 170–191. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arbaugh, J. (2000). Virtual classroom versus physical classroom: An exploratory study of class discussion patterns and student learning in an asynchronous internet‐based MBA course . Journal of Management Education , 24 ( 2 ), 213–233. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arias, J. J. , Swinton, J. , & Anderson, K. (2018). On‐line vs. face‐to‐face: A comparison of student outcomes with random assignment . e‐Journal of Business Education and Scholarship of Teaching, , 12 ( 2 ), 1–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernard, R. M. , Abrami, P. C. , Lou, Y. , Borokhovski, E. , Wade, A. , Wozney, L. , Wallet, P. A. , Fiset, M. , & Huang, B. (2004). How does distance education compare with classroom instruction? A meta‐analysis of the empirical literature . Review of Educational Research , 74 ( 3 ), 379–439. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown, B. , & Liedholm, C. (2002). Can web courses replace the classroom in principles of microeconomics? American Economic Review , 92 ( 2 ), 444–448. [ Google Scholar ]

- Callister, R. R. , & Love, M. S. (2016). A comparison of learning outcomes in skills‐based courses: Online versus face‐to‐face formats . Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education , 14 ( 2 ), 243–256. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coates, D. , Humphreys, B. R. , Kane, J. , & Vachris, M. A. (2004). “No significant distance” between face‐to‐face and online instruction: Evidence from principles of economics . Economics of Education Review , 23 ( 5 ), 533–546. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coetzee, M. (2014). School quality and the performance of disadvantaged learners in South Africa (Working Paper No. 22). University of Stellenbosch Economics Department, Stellenbosch

- Dutton, J. , Dutton, M. , & Perry, J. (2002). How do online students differ from lecture students? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks , 6 ( 1 ), 1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Emediegwu, L. (2021). Does educational investment enhance capacity development for Nigerian youths? An autoregressive distributed lag approach . African Development Review , 32 ( S1 ), S45–S53. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fallah, M. H. , & Ubell, R. (2000). Blind scores in a graduate test. Conventional compared with web‐based outcomes . ALN Magazine , 4 ( 2 ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Figlio, D. , Rush, M. , & Yin, L. (2013). Is it live or is it internet? Experimental estimates of the effects of online instruction on student learning . Journal of Labor Economics , 31 ( 4 ), 763–784. [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeman, M. A. , & Capper, J. M. (1999). Exploiting the web for education: An anonymous asynchronous role simulation . Australasian Journal of Educational Technology , 15 ( 1 ), 95–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilbert, P. (2019). The most expensive data prices in Africa . Connecting Africa. https://www.connectingafrica.com/author.asp?section_id=761%26doc_id=756372

- Glick, P. , Randriamamonjy, J. , & Sahn, D. (2009). Determinants of HIV knowledge and condom use among women in Madagascar: An analysis using matched household and community data . African Development Review , 21 ( 1 ), 147–179. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gyimah‐Brempong, K. (2011). Education and economic development in Africa . African Development Review , 23 ( 2 ), 219–236. [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson, S. , Aragon, S. , Shaik, N. , & Palma‐Rivas, N. (2000). Comparative analysis of learner satisfaction and learning outcomes in online and face‐to‐face learning environments . Journal of Interactive Learning Research , 11 ( 1 ), 29–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lundberg, J. , Merino, D. , & Dahmani, M. (2008). Do online students perform better than face‐to‐face students? Reflections and a short review of some empirical findings . Revista de Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento , 5 ( 1 ), 35–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Means, B. , Toyama, Y. , Murphy, R. , Bakia, M. , & Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidence‐based practices in online learning: A meta‐analysis and review of online learning studies (Report No. ed‐04‐co‐0040 task 0006). U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development, Washington DC.

- Navarro, P. (2000). Economics in the cyber‐classroom . Journal of Economic Perspectives , 14 ( 2 ), 119–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Navarro, P. , & Shoemaker, J. (2000). Performance and perceptions of distance learners in cyberspace . American Journal of Distance Education , 14 ( 2 ), 15–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Neuhauser, C. (2002). Learning style and effectiveness of online and face‐to‐face instruction . American Journal of Distance Education , 16 ( 2 ), 99–113. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nguyen, T. (2015). The effectiveness of online learning: Beyond no significant difference and future horizons . MERLOT Journal of Online Teaching and Learning , 11 ( 2 ), 309–319. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paechter, M. , & Maier, B. (2010). Online or face‐to‐face? Students' experiences and preferences in e‐learning . Internet and Higher Education , 13 ( 4 ), 292–297. [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell, T. L. , & International Distance Education Certificate Center (IDECC) (1999). The no significant difference phenomenon: A comparative research annotated bibliography on technology for distance education: As reported in 355 research reports, summaries and papers . North Carolina State University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shachar, M. , & Neumann, Y. (2010). Twenty years of research on the academic performance differences between traditional and distance learning: Summative meta‐analysis and trend examination . MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching , 6 ( 2 ), 318–334. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shachar, M. , & Yoram, N. (2003). Differences between traditional and distance education academic performances: A meta‐analytic approach . International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning , 4 ( 2 ), 1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tchamyou, V. S. , Asongu, S. , & Odhiambo, N. (2019). The role of ICT in modulating the effect of education and lifelong learning on income inequality and economic growth in Africa . African Development Review , 31 ( 3 ), 261–274. [ Google Scholar ]

- Xu, D. , & Jaggars, S. S. (2014). Performance gaps between online and face‐to‐face courses: Differences across types of students and academic subject areas . The Journal of Higher Education , 85 ( 5 ), 633–659. [ Google Scholar ]

Online Vs Traditional Classes: a Comparative Analysis