- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Solar eclipse

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- Why cultural criticism matters

Cultural criticism is journalism. And in an era when fewer outlets support it, we need more of it, not less

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Why cultural criticism matters

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62759157/shutterstock_1113168074.0.jpg)

I’ve been thinking about The Hateful Eight a lot lately.

There’s no real good reason for this, except that the movie, which came out in 2015 and is Quentin Tarantino’s most recent film, takes place in a kind of miserable, snow-covered hell, making it one of those non-Christmas films that still feels most appropriate to break out at the end of the year.

The movie was one of Tarantino’s lowest earners at the box office, and it hasn’t had the long tail that many of his other films have enjoyed in the cultural conversation. If Tarantino has ever made a movie that’s been largely forgotten, it’s The Hateful Eight .

And yet I can’t seem to shake it, over three years after I first saw it.

I didn’t think much of the movie at the time . Filmed largely on one set, where eight characters gab and gab and gab at each other until the bloodshed begins, the nearly three-hour film is an endless series of provocations by Tarantino that toy with big dividing lines around race, class, and especially gender in America, without tipping its cap toward what it really thinks.

It’s a nasty, ugly movie, and it’s all but impossible to tell if Tarantino is reveling in that nastiness and ugliness (which he does from time to time, as in his 2007 movie Death Proof ) or depicting it so that we might reflect on our own nastiness and ugliness (which he did in his 2012 movie Django Unchained , whose core goal seems to be forcing white Americans to confront their ancestors’ role in the institution of slavery).

The Hateful Eight is just mean , and it feels like the work of someone who looked around at America and concluded that it was a land full of angry, spiteful people who would be more willing to burn their own lives to the ground than admit either their own sins or the sins of their country. It’s an apocalyptic story, even though it’s set in the Old West, about a country trapped in a cabin with itself and tilting toward murder.

In 2015, it played like Tarantino sticking his tongue out at you from the movie screen. But in 2018, it plays like a prophecy I missed at the time.

The two years since the 2016 election have been disastrous for the continued employment of cultural critics and journalists

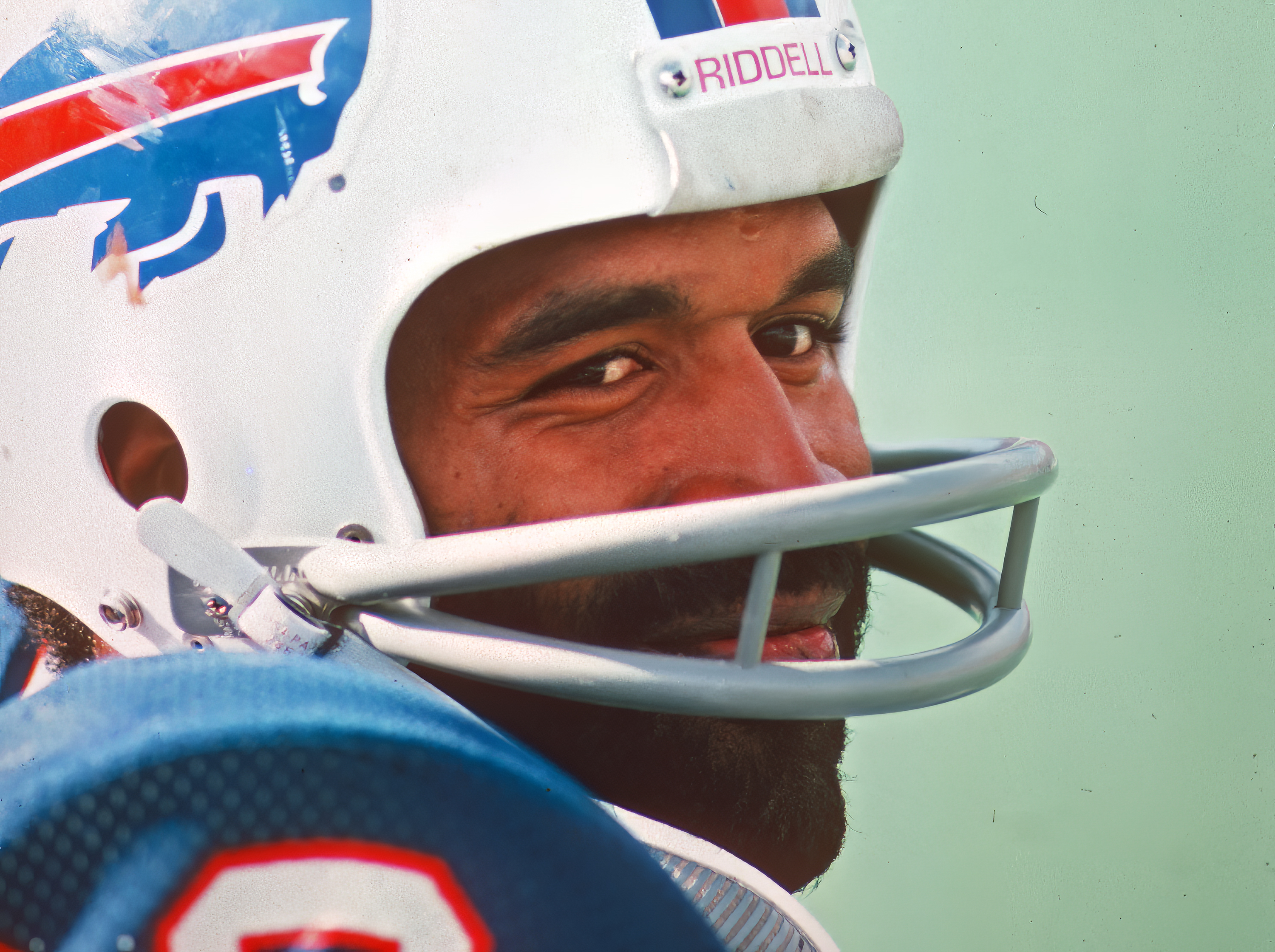

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13658955/837355130.jpg.jpg)

The last two years have not been particularly great for cultural criticism and culture writing more generally. The twin pressures of a political situation that has a tendency to gobble up all available media oxygen and the increased centrality of review aggregation sites like Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic (to the degree that movie studios routinely blame bad Rotten Tomatoes scores for their box office failures) have pushed more and more media companies to cut back on culture writing.

Often, these cuts have come to pass through the outright downsizing of culture-writing staffs. Buzzfeed dismissed four culture writers and editors in late 2017 (though it still employs the terrific critic Alison Willmore) and its culture-oriented podcast team in 2018. In July 2018, many staff members of The A.V. Club, perhaps the internet’s longest-running outlet focused solely on pop culture, took buyouts as part of an ongoing effort by the site’s corporate parent, Gizmodo Media Group, to trim costs. In October, veteran music publication The Fader laid off its most senior employees .

Here is a list of places *just off the top of my head* that have laid off culture/features reporters and not rehired for them in the last 2 years: -Fusion -MTV News -The Village Voice -Buzzfeed -IBT -Vocativ -LA Weekly -Fader -Inverse -Upworthy -Complex -GQ -Gothamist - — kelsey mckinney (@mckinneykelsey) November 8, 2018

But some publications simply ceased to publish culture writing altogether, when they weren’t going out of business entirely. In particular, independent newspapers like the Village Voice, an important incubator of tremendous cultural writing for decades, shuttered completely , while its connected Voice Media has ceased film and TV coverage entirely as of December 31, 2018. Similarly, the website Mic has more or less been stripped for parts .

The above is not intended as an exhaustive list. Many, many more publications have cut cultural journalism either in part or in whole. And these job losses are often doled out piecemeal — a layoff here, or a position left unfilled after a departure there. The larger picture can be easy to miss unless you happen to notice culture writers announcing they’ve been laid off on Twitter or are a freelancer trying to pitch to an ever-shrinking pool of outlets. But the pool is shrinking, drip by drip.

It would be one thing if some publications were cutting cultural journalists, but those cultural journalists were still able to find jobs elsewhere. But over the past two years, in numerous discussions I’ve had with journalists at all levels of the cultural journalism ecosystem, it’s become more and more clear that the jobs simply aren’t there.

If you look beyond publications that have intentionally reduced the number of culture writers on their staffs, you’ll find many that have curtailed hiring around culture writing — often in favor of expanding political coverage. They’ve either mostly held pat with culture hiring since the 2016 election, or they’ve opted not to fill positions that opened because someone left, shifting those resources toward political writing.

That’s not to say that no one has hired culture writers of late. But for the most part, in 2017 and 2018, from major newspapers to tiny websites, anyone with enough money to hire new journalists usually wasn’t putting it toward an expanded culture section.

On the one hand, I get this. If I were in charge of a major publication, I would probably be hiring political reporters, too. But on the other hand, cultural criticism is important — vitally so. Sure, it’s how I earn a paycheck, but long before I got into this line of work, great cultural journalism gave me other ways of looking at and understanding the world, which is core to journalism’s mission statement. We need cultural criticism not just to tell us which movies to go see and which ones to avoid, but to tell us things we already knew but didn’t know how to express. If reporting can explain the world to us, cultural criticism can explain us to us.

How our pop culture can offer a dim vision of where we might be headed, explained by the rise of Nazism in the early 20th century

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13658958/GettyImages_2637656.jpg)

One of the foremost critical texts ever written is Siegfried Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler . Kracauer, a film scholar and critic, escaped his native Germany for France as the Nazis rose to power, then escaped France for the US in early 1941, after the Nazis had conquered the country.

Kracauer is associated with the Frankfurt School, a group of Marxists who attempted to tackle questions of how better to build societies, after finding the various structures proposed in the early 20th century sorely lacking (this is an impossibly brief summary, but if you’re interested in the details or just writing and thought in general, you should read more about the Frankfurt School — try the solid history Grand Hotel Abyss by Stuart Jeffries ). But From Caligari to Hitler is concerned less with questions of how to build societies than it is with how societies build and conceptualize themselves via the dream logic of movies.

Kracauer starts from a seemingly self-evident premise: German expressionist filmmakers (like Robert Wiene, who made the 1920 classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari , which gives the book its title) created startlingly artistic statements unlike any others in the rest of the world, shot through with a dark, foreboding sense of impending doom, which paired well with the rise of fascism slowly bubbling away in German society in the ‘20s and early ‘30s.

But Kracauer goes one step further, positing that both these films and the oft-forced cheerfulness of the films that were made after numerous central figures in expressionist movements departed for Hollywood are early psychological manifestations of something within German culture that made Nazism inevitable. He argues that films aren’t just documents of a culture’s values and chosen narrative tropes, but a kind of document of a culture’s subconscious, one that filmmakers often don’t know that they’re making.

Kracauer has a couple of explanations for why he thinks films are so vital to understanding a culture’s psyche, both of which could presumably be applied to television, video games, and maybe even pop music as well.

The first is that while there are always directors or producers “in charge” of a given film, it is inevitably the work of many, many artists — and the more people involved, the more accurately it reflects a culture’s buried hopes. Even if the corporations that make and release films are mostly interested in turning profits, Kracauer suggests, the best way for them to do so is to reflect things that a culture either badly wants to be true or deeply identifies with on some level.

The second is that films address themselves to “the anonymous multitude.” Writes Kracauer in his introduction:

What films reflect are not so much explicit credos as psychological dispositions — those deep layers of collective mentality which extend more or less below the dimension of consciousness. ... Owing to diverse camera activities, cutting and many special devices, films are able, and therefore obliged, to scan the whole visible world. ... In the course of their spatial conquests, films of fiction and films of fact alike capture innumerable components of the world they mirror: huge mass displays, casual configurations of human bodies and inanimate objects, and an endless succession of unobtrusive phenomena. As a matter of fact, the screen shows itself particularly concerned with the unobtrusive, the normally neglected. ... That films particularly suggestive of mass desires coincide with outstanding box-office successes would seem a matter of course. But a hit may cater only to one of many coexisting demands, and not even to a very specific one. In her paper on the methods of selection of films to be preserved by the Library of Congress, Barbara Deming elaborates upon this point: “Even if one could figure out ... which were the most popular films, it might turn out that in saving those at the top, one would be saving the same dream over and over again ... and losing other dreams, which did not happen to appear in the most popular individual pictures but did appear over and over again in a great number of cheaper, less popular pictures.”

Kracauer spends the rest of his book providing a long, in-depth overview of German cinema from its inception to the reign of the Nazis, from pre-World War I examples to filmmakers like Leni Riefenstahl. But his central thesis holds true: Every film, even one of more marginal success, tells you something about the culture that produced it, and the more knowledge you have of how films are made, of how they can create false narratives we desperately want to be true, and of how they intersect with other forms of philosophy and thought, the more you can understand how they serve as signposts toward whatever is to come next.

Kracauer’s methods can be applied to our current pop culture — and the most astute cultural critics often do so

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2542284/truedetective.0.jpg)

Kracauer, of course, was writing his book after the end of World War II. Nazism had been defeated, and German cinema was knocked back by the end of the war as much as everything else in the country. And his timing exposes one of the issues with these sorts of psychological readings — they predict the future, but only if you know what the future looks like already. Which is to say: They are often more useful in hindsight.

I suspect this is why I’ve been thinking so much about The Hateful Eight and its provocative statements about the dark heart of America as 2018 comes to a close; I’ve also been thinking about American Sniper and True Detective and Girls and a host of other entertainments that seemed to herald some sort of budding culture war in the first half of the 2010s with the discussions and debates they started, even as the sleek self-satisfaction of left-leaning media figures in those same years insisted that America was inevitably going to keep pushing further leftward, just very gradually. Demographics had solved everything!

What is important to note here is that the psychologically predictive elements of the works listed above (and numerous others — one could make an argument of this sort surrounding the superhero films of Marvel and DC’s movie studios, for instance ) exist independent of their actual quality. The popular understanding of what a critic does is that a critic tells you whether something is good or bad. But that is the least interesting part of a critic’s job, when all is said and done, because two critics can see the same movie, agree largely on its strengths and flaws, then weight them very differently in their heads .

The true role of a critic is to pull apart the work, to delve into the marrow of it, to figure out what it is trying to say about our society and ourselves. You can love a work and think its politics are deeply problematic; you can believe something is terrible yet offers some accidentally acute insights about the way the world works.

To choose two examples from my list above: I think the second season of True Detective (which was released in the summer of 2015) is an almost unwatchable misfire, a cluttered mess that never once shows any understanding of how to tell a complicated crime story in the time allotted to it. But it’s also one of the more insightful series of its particular generation when it comes to questions of how broken capitalist systems turn people into literal spare parts, exploitable cogs that can be hammered into place and treated like shit because they have no real value as human beings, just as pieces of the larger system. In this fashion, it anticipates more recent TV shows like Westworld and The Handmaid’s Tale , in addition to so many debates we’ve had around politics and populism since it aired.

Girls , meanwhile, remains one of my favorite shows of the decade, but in 2018, it’s much harder to read as anything other than solipsistic. In 2012, when the series debuted, it was easier for at least some critics (myself included) to defend the way Girls ’ protagonists were almost fatally blinkered when it came to the world around them.

Over the course of the show’s six seasons (concluding in 2017), the characters did “grow up,” but their growing up involved so little actual struggle or conflict that it seemed as if the show was unaware of any person who existed outside of online comments sections or the pages of the New Yorker. Its greatest blinders were always to its own characters’ economic and racial privileges, and while it was sometimes aware of that, it was too often not.

And that unawareness is an important puzzle piece in a larger picture of how everything that America would go through in 2016 and beyond was already being stretched to a breaking point in pop culture, which embraced antiheroes who nonetheless exuded a kind of masculine code of ethics all over the place, a kind of dim harbinger of the man in the Oval Office.

None of this is to say that all culture writing should be about Donald Trump. Far from it. That particular rag has been wrung dry. Indeed, many of the most popular works of the past year, both commercially and critically, have been about building better worlds, about utopian ideals, about how great it would be to live in Wakanda (so long as you were in the ruling class), or about how Gilead or the afterlife of The Good Place must be radically altered to create a new, more just way of living.

Once we know where we’re going, all of this will make more sense. But culture writing isn’t about predicting the future — it’s about predicting the present.

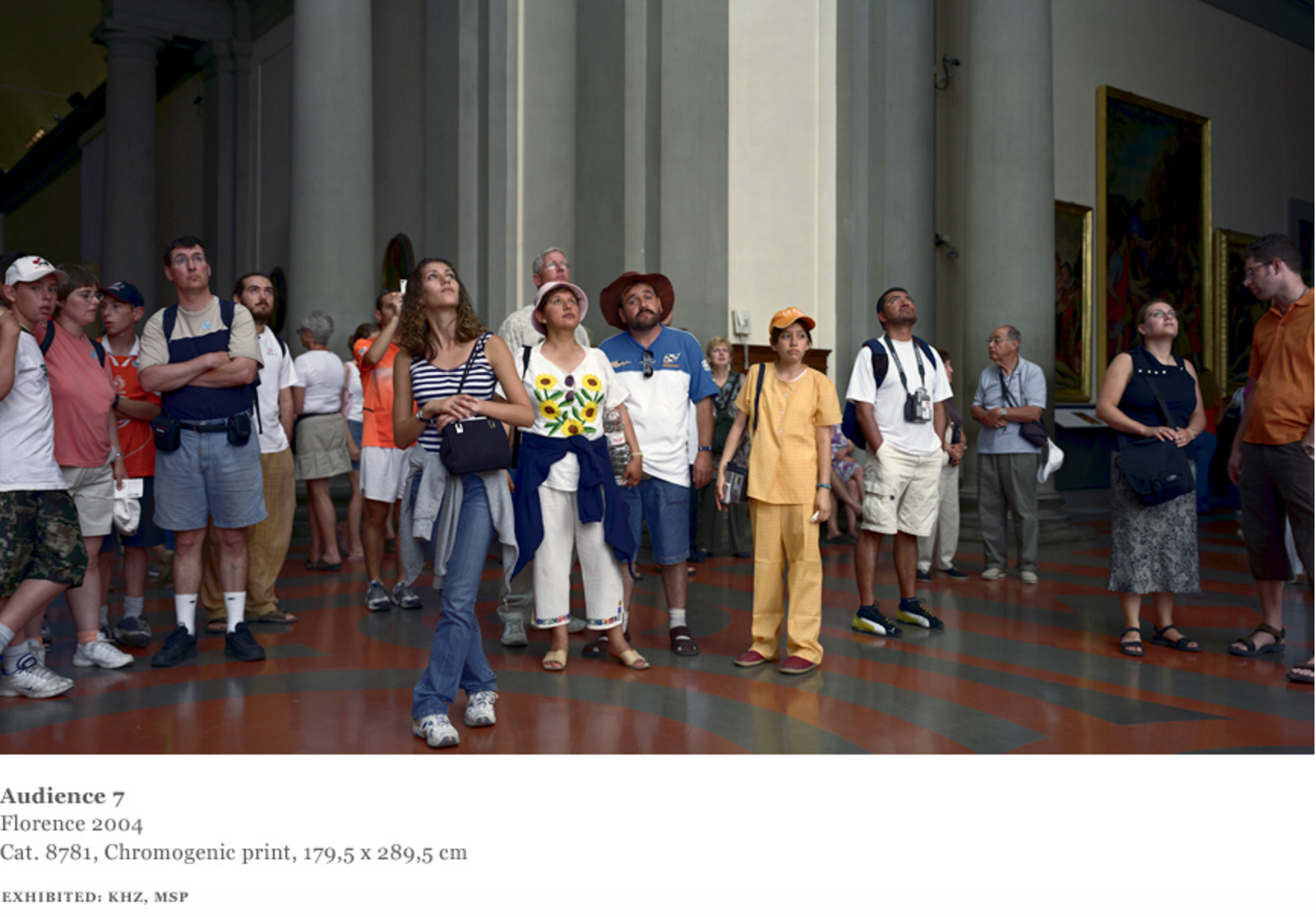

Culture writing can help better explain a vast, sometimes contradictory society

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10263123/black_panther_chadwick_boseman_lupita_nyongo.jpg)

When I make the above argument in favor of cultural criticism to journalistic colleagues who deal in what might be dubbed the “hard sciences” of journalism — data-driven, boots-on-the-ground reporting — I am always aware that it sounds just a little fantastical. And there have been many times that I and my critical brethren have just plumb missed something burbling away in the national subconscious. Few critics looked at the pop culture of the early 2010s and said, “Yep, a culture war’s brewing,” even if it seems blindingly obvious in hindsight.

You can attribute at least some of missing that particular boat to the geographical concentration of cultural critics in New York and Los Angeles (where I live). The homogeneity of critics — too many of us are white, too many of us are male, and too many of us live on one of the coasts — is a real problem that needs to be corrected sooner, rather than later, if we are to better understand the dreams a multicultural nation is having, sometimes in parallel and sometimes in bloody intersection.

Perhaps this is why The Hateful Eight looms so large for me even still. It is a movie that juts America’s lofty ideals right up against its bloody reality, a movie that understood better than most that the precipice we all stood on in 2015 was very different from the one we thought we were on. It’s an ugly movie, sure, but maybe it’s an ugly world. Maybe it was telling the truth, and hoping otherwise is a fool’s errand. It embraces contradiction, in a way that still unsettles.

And yet it is not a final answer, and no review of it will ultimately be a final answer. The movie’s meaning — all movies’ meanings — changes with time, as we change with time. No one piece of culture writing can explain us in all our contradictions. That’s why we need more, not less, of the form. There is probably too much stuff out there to ever get any accurate read of exactly what America is worked up about now — except, maybe, in broader trend pieces — but every new film, TV show, book, game, and album is a new brick in the wall, a new argument to be made.

We’re a country of angry, outsized reactions to any fanboy project that dares cast a woman or person of color in its lead, but also one that makes movies like Black Panther and Crazy Rich Asians and even BlacKkKlansman successful box office hits. We’re a country of Aquaman and The Mule and On the Basis of Sex — to choose three radically different movies, with very different political views, that were sold out for evening showings at my favorite multiplex a few nights ago. We’re a country where everything from The Big Bang Theory to The Good Place , from Game of Thrones to This Is Us , can be a major hit.

The fact that criticism is, on some level, the work of those of us who sit in a dark room and try to interpret dreams will probably always feel a little suspect to some of my colleagues, but it shouldn’t. It is just as deeply reported, just as astutely interpreted, just as rigorously thought through as any other form of journalism, just in a very different form, one that can sound fantastical but one that has centuries of thought and theory backing it up, all the way back to ancient Greece .

Cultural criticism isn’t necessary just so we know what movie to see when we head to the multiplex. It’s necessary because it is part of how we begin to understand both ourselves and this weird, vibrant, crumbling country we are all a part of.

Better than any data set I can think of, it tells us where we’ve been, where we are, and maybe even where we’re going. It’s vital to any publication, to any newsroom, and to any well-rounded news diet. Now, in 2019, let’s see even more of it.

7 great pieces of culture writing from 2018

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12761347/Adventure_Time_Episode_282_Still.jpg)

If you’re excited to explore some great culture writing from the past year, here are seven of my favorite pieces (one of which isn’t in written form at all) digging into pop culture in all its forms.

“Ten Years Later, The Dark Knight and its vision of guilt still resonate,” Bilge Ebiri for the Village Voice

It’s hard to write a retrospective on a movie or TV show everybody has seen, but Ebiri digs deep into what The Dark Knight said about the late George W. Bush era, then shows how the movie pointed to what was to come.

Where then does that leave Gotham? The Dark Knight ends with the city living a lie, but seemingly out of the darkness. (At least for now, since The Dark Knight Rises would show the disastrous consequences of Gordon and Bruce’s duplicity.) And yet it’s hard to look at this movie, made at a time of violent divisiveness in the country over issues of surveillance, of complicity, of violence born of fear, and not see a snapshot of a society — not Gotham’s fictional one, but our own, real-life one — ready to plunge into the abyss of fragmentation, of self-serving chaos. Maybe that’s why Nolan’s film now feels so poignant. Today, it’s hard not to feel that humanity’s worst impulses have won, that those without conscience or shame were allowed to sow endless dissension, hatred, and cruelty, using our own sense of guilt against us.

“2018’s big horror film trend: inherited trauma,” Britt Hayes for ScreenCrush

I pitched this piece, then watched as Hayes wrote a far better version of it than I could have mustered. It’s a great example of noticing a trend in entertainment, then following it to its logical conclusion.

There is a house. Inside is a miniature dollhouse filled with perfect replicas of a life that could be, or might’ve been. Maybe it’s a better version of that life, but it is silent and still — unlike the people around it, who are consumed by trauma. Curiously, four of this year’s most poignant and effective horror stories — Hereditary , The Haunting of Hill House , Sharp Objects , and Halloween — are thematically connected by their exploration of familial mental illness and inherited trauma, and by these miniature dollhouses, which appear in some form in every single one.

“Why I’ve had trouble buying Hollywood’s vision of girl power,” Alison Willmore for Buzzfeed

Pop feminism was everywhere in 2018, and Willmore starts from a Ruth Bader Ginsburg action figure to dissect just why so much pop feminism feels so empty and consumerist.

2018 has been as rich with slogany, simplified women’s empowerment callouts as it has been with reasons for women to be filled with rage and dread, stretching way beyond the merch and mild cinema that’s come to surround Ginsburg. This kind of messaging has shown up all over the movies this year, and television too, from Ocean’s 8 to the Kevin Spacey-less final season of House of Cards. Some of it was sincerely meant, some of it was calculated as hell, and most of it left me in the dust.

“Hulu’s The Bisexual is here to make every queer a little bit uncomfortable,” Heather Hogan for Autostraddle

This is, ostensibly, just a review of a TV show, but it’s also so much more, pushing past merely telling you whether the show in question is good or not to interrogate Hogan’s own responses to it.

During the first two episodes of The Bisexual , I kept thinking, “There’s not a single queer person on the internet who isn’t going to be offended by this in some way” — and by the end of the season, I understood that was the point.

“ Adventure Time finale review: One of the greatest TV shows ever had a soulful, mind-expanding conclusion,” Darren Franich, Entertainment Weekly

Sometimes, writing critically just means celebrating something you loved. Franich offers a sweetly tempered eulogy to a beloved TV series in this extended breakdown of the finale.

Sans commercials, Monday’s “giantsized” final episode clocked 44 minutes, 47 seconds, the precise length of time it takes your average prestige drama to burp. The series finale — variously titled “The Ultimate Adventure” or “Come Along With Me” — found time for two epic showdowns, three epic kisses, two musical numbers, one gigantic personification of universal chaos. This was a last explosion of imagination, every millisecond a subreddit waiting to happen. Eight years is a healthy run, but the propulsive energy suggested a brilliant-but-canceled oddity, an epic saga with an episode order cut halfway through season 3, an “ending” crammed with ideas that could’ve engine-fueled another five seasons.

“CBS’s toxic culture isn’t just behind the scenes. It’s in the shows that it makes,” Kathryn VanArendonk for Vulture

VanArendonk uses deep knowledge of CBS crime procedurals to point to how a culture of sexual harassment was allowed to flourish not just at the company but in the shows it put on the air.

The stories CBS puts out into the world are the ones that reflect the interests of the people who make them, and what results is a self-perpetuating cycle. When we as CBS viewers watch stories that valorize male ego and male judgment, we’re bathed in a TV landscape that teaches us that men who have power are the default. So when men like Les Moonves, Brad Kern, and Michael Weatherly harass and abuse the women around them, their entitlement to hold positions of power appears normal in the context of the shows they make. They are entitled to that power, and that entitlement is confirmed and echoed by what we watch on TV, night after night.

“ Hereditary hot take,” May Leitz (aka NyxFears) for YouTube

Leitz’s deep dive into Hereditary genuinely changed how I thought about one of my favorite movies of the year and made me appreciate it even more. To say more would be to spoil her reading, but the video essay is peppered with evidence from the film itself.

And, of course, if you’re still looking for great culture writing to read, check out what we publish here at Vox , from Aja Romano on the history of Bert and Ernie as queer icons , to Alissa Wilkinson’s beautiful review of Eighth Grade ; from Alex Abad-Santos’s thoughts on the Victoria’s Secret fashion show in the time of corporate wokeness to Constance Grady on why so many TV shows right now are about people trying to be good. (And, okay, you can read my Gritty explainer if you like.)

Correction: The writers who left Buzzfeed, though culture writers, weren’t primarily focused on writing criticism.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

In This Stream

More from emily todd vanderwerff.

- The past 11 presidencies, explained by the TV shows that defined them

- Nancy, a 1930s comic strip, was the funniest thing I read in 2018

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

O.J. Simpson’s story is built on America’s national sins

What to do if you’re worried about “forever chemicals” in your drinking water

Why is there so much lead in American food?

Florida and Arizona show why abortion attacks are not slowing down

The Vatican’s new statement on trans rights undercuts its attempts at inclusion

The messy legal drama impacting the Bravo universe, explained

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Cultural Criticism and the Way We Live Now

By Louis Menand

Susan Sontag was against interpretation. Laura Kipnis was against love. Seven were against Thebes. Mark Greif is against everything.

That’s the title of his new book, the subtitle of which is “Essays.” Neither is completely accurate. Greif is against the way things are, but he has hopes for the way things might become. And, although “Against Everything” is put together from essays written over the past twelve years, and published mostly in the journal of which Greif is a founding editor, n+1 , it is really a book on a single subject: contemporary life, more specifically, the kind of life that someone who would buy such a book, or write such a book, or read a column about such a book—in short, yourself—might right now be living. It’s meant to be consumed from beginning to end. It makes you think.

I guess “Against Everything” would be called a work of cultural criticism. I’ve always disliked that term, since it’s related to no body of knowledge and names no actual calling, unlike, say, movie criticism or book reviewing. Also, movies are movies and books are books, but culture is everything. How are you supposed to get a handle on everything?

“We are incompetent to solve the times,” Emerson said (though, characteristically, he then went on to try to solve them), and that has always seemed a sound journalistic maxim to me. The songs, the shows, the books and movies, the art-world sensations, fashion statements, political spectacles, and tech innovations, the celebrities, cover stories, foods, meds, drugs, diets, exercise regimens, and life-style themes that “everyone” seems to be talking about or taking up or disapproving of—there is just too much foreground. It’s like a classroom in which every student’s hand is raised. “Make sense of me ,” they all cry out.

The problem isn’t picking out what will last. That, actually, is relatively easy. Critical reception is imperfect and it’s not always aligned with popular taste, but major oversights are rare. The problem is figuring out, in the constant bombardment of attention-seeking missiles, which ones tell us something about who we are.

The main difficulty is not knowing what’s a trend, what’s a backlash, and what’s a blip. Many years ago, when people began jogging, I predicted, with the confidence of untried youth, that jogging was a fad that couldn’t last. It wasn’t that ordinary-looking people running in public in their shorts seemed kind of unnatural, although it did. I just couldn’t see how an activity that requires only a pair of sneakers could be sufficiently commercialized to become a fixture in the national life style. Such was my ignorance about the money in footwear.

Jogging didn’t end, but it did evolve into the current professional-class practice of “going to the gym”—a more high-cap and economically exploitable enthusiasm, and the subject of one of Greif’s most devastating “against” essays. The essay is devastating even if you think you have a sensible (or lazy) person’s ambivalence about regimented exercise. You will still feel, after reading him, that you have bought into a soul-destroying managerialism that has disguised itself as a means of enhancing “life.” (Greif’s essay on another professional-class fetish, food, is similarly unsettling.) Greif’s hero is Thoreau, which gives you an idea of the radicalism of his disaffection.

The cultural critic’s conceptual enemy is the smoothing formula known as “the wisdom of crowds.” On that theory, it must be the case that the person whose favorite song is the No. 1 song, whose favorite book is a best-seller, whose favorite food just switched from kale to quinoa, is the luckiest person in the world, because the culture is producing exactly the goods that he or she enjoys. This rule would apply right down all the rungs of life-style choices within your demographic: the kind of car you drive, the number of kids you have, where you take your vacations. On a wisdom-of-crowds hypothesis, what most people who are like you choose to do should be the optimal choice for you.

The cultural critic’s answer is that if you are doing what everyone around you is doing, you are not thinking, and if you are not thinking, you are missing out on your own life. The cultural critic is the person who worries that what everyone is doing right now is distracting us from what is really important, and precisely because it’s what everyone is doing.

The trouble, usually, is identifying the alternative. For the marketplace is flooded with alternatives: that’s what all those raised hands represent. You don’t like what all those people are doing? Do what all these people are doing. There are a lot of defiance goods out there offering an adversarial experience—like high-end pop music (for which Greif has a soft spot: his most brilliant essay is an amazingly multilayered piece called “Learning to Rap”).

But you don’t want to mistake some band’s assertion of autonomy (commercially enabled, but let’s leave that aside) for your own. What you want is something that seems unattainable in a society as saturated in mediated desires as ours is: you want uncoerced choice. Greif’s argument—and this is what separates him from the usual solver of the times—is that what’s killing us is deeply embedded in our social and economic system. It’s not the gym that’s the problem. It’s the way we live now, which is making the gym seem like a solution to something.

Greif thinks that a whole lot will have to change before real choice is possible. Until then, it’s not enough to be against the box-office and the real-estate section and the best-seller list. Until then, we have to be against . . . everything.

It’s a peculiarity of this kind of criticism, criticism that takes on the whole culture, that it is often misread. Most people remember David Riesman’s “The Lonely Crowd” as a critique of mid-century men and women as other-directed, but he actually thought that inner- and outer-direction are mixed in everyone. (He also tied his categories to a prediction about population growth that turned out to be wildly inaccurate, and which he cut from later editions.) Many readers also thought that what Christopher Lasch called “The Culture of Narcissism” referred to a surge of egocentricity. Lasch had to write another book, “The Minimal Self,” to explain that narcissism is symptom of the erosion of ego. Few people remember that one. I don’t think readers will make a mistake about Greif, but it will be interesting to see if they do.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Kyle Chayka

By Anthony Lane

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Writing Curriculum

Analyzing Arts, Criticizing Culture: Writing Reviews With The New York Times

This unit invites students to write about food and fashion, movies and music, books and buildings for a global audience. It features writing prompts, mentor-text lesson plans and a culminating contest.

By The Learning Network

To learn more about all our writing units, visit our writing curriculum overview .

Before the digital age, review writing was largely the province of a small circle of elite tastemakers. That circle still includes critics at The Times, people like A.O. Scott or Pete Wells, who can make or break a movie or a restaurant with a single review.

But these days, all of us are invited to be reviewers — to rate and comment on everything from books and movies to yoga classes and electric toothbrushes. Though this kind of casual writing offers students real audiences and purposes, it often doesn’t require the type of close reading, deep thinking and careful craftsmanship more formal classroom writing demands.

In this unit, we hope to bridge the two, and prove to students that review-writing can be fun.

So why should your students read and write arts and culture reviews? How can doing so fit into your curriculum?

Well, first consider what students will need to know and be able to do:

A cultural review is, of course, a form of argumentative essay. Your class might be writing about Lizzo or “ Looking for Alaska ” instead of, say, climate change or gun control, but they still have to make claims and support them with evidence.

Just as students must for that classroom classic, the literature essay, a reviewer of any genre of artistic expression has to read (or watch, or listen to) a work closely; analyze it and understand its context; and explain what is meaningful and interesting about it.

It may go without saying that review writers have to wrestle with the same questions that writers of any text confront — how to compose in a voice, style, vocabulary and tone that fits one’s subject, audience and purpose. But when you’re writing a review, influencing people is the point, and our unit offers a built-in authentic audience. Beginning with our informal writing prompts and culminating in our review contest, we encourage students to post their work for a global audience of both teenagers and adults to read.

Our contest allows students to write about any work they like from any of 14 categories of expression — including movies, music, restaurants, video games and comedy. To participate, they’ll have to think deeply about the cultural and artistic works that matter most to them, then communicate why to others. That’s not just a skill they need in school, it’s a way of thinking that can serve them for life.

Like all the writing units we publish, this one pulls together a range of flexible resources you can use however you like. While you won’t find a pacing calendar or daily lesson plans, you will find plenty of ways to get your students reading, writing and thinking.

Here are the elements:

Start with four writing prompts that help students become aware of the role of the arts and culture in their lives.

Anatomy of a scene | ‘black panther’, ryan coogler narrates a sequence from his film featuring chadwick boseman as t'challa, a.k.a. black panther..

I’m Ryan Coogler, co-writer and director of “Black Panther”. This scene is an extension of an action set piece that happens inside of a casino in Busan, South Korea. Now, T’Challa is in pursuit of Ulysses Klaue, who’s escaped the casino. He’s eliciting the help of his younger sister, Shuri, here, who’s back home in Wakanda. And she’s remote driving this Lexus sports car. And she’s driving from Wakanda. She’s actually in Wakanda. T’Challa’s in his panther suit on top of the car in pursuit. These are two of T’Challa’s comrades here. It’s Nakia who’s a spy, driving, and Okoye who’s a leader of the Dora Milaje in the passenger’s seat in pursuit of Klaue. The whole idea for this scene is we wanted to have our car chase that was unlike any car chase that we had seen before in combining the technology of Wakanda and juxtaposing that with the tradition of this African warrior culture. And in our film we kind of broke down characters between traditionalists and innovators. We always thought it would be fun to contrast these pairings of an innovator with a traditionalist. T’Challa, we kind of see in this film, is a traditionalist when you first meet him. His younger sister, Shuri, who runs Wakanda’s tech, is an innovator. So we paired them together. In the other car we have Nakia and Okoye, who’s also a traditionalist-innovator pairing. Nakia is a spy who we learn is kind of unconventional. And Okoye, who’s a staunch traditionalist, probably one of our most traditional characters in the film, you know, she doesn’t really like being in clothes that aren’t Wakandan. And this scene is kind of about her really bringing the Wakandan out. One of the images that almost haunted me was this image of this African woman with this red dress just blowing behind her, you know, spear out. And so a big thing was, like, you know, for me was getting the mount right so that the dress would flow the right way. It wouldn’t be impeded by the bracing system she was sitting on. So that took a lot of time. We had to play with the fabric and the amount of the dress to get it right.

While the teenagers you know may be able to talk passionately about music, movies, food and fashion, they may never have had formal practice in communicating the complex observations and analysis behind those reactions. It’s possible that they have also never been pushed to experience forms of art or culture that are new to them.

We developed these five prompts in 2019, but of course they can work for any year of this contest. Invite your students to read what others have previously posted, or contribute their own ideas.

Do You Read Reviews?

What Work of Art or Culture Would You Recommend That Everyone Experience?

What Work of Art or Culture Would You Warn Others to Avoid? Why?

What Could You Read, Listen to or Watch to Stretch Your Cultural Imagination?

What Was the Best Art and Culture You Experienced in 2020?

Whether they’ll ultimately participate in our contest or not, we hope your students will have fun answering these questions — and then enjoy reading the work of other students, commenting on it, and maybe even hitting that “Recommend” button if they read a response they especially like.

All our prompts are open for comment by students 13 and up, and every comment is read by Times editors before it is approved.

Continue with our lesson plan, “ Thinking Critically: Reading and Writing Culture Reviews. ”

This lesson, published in 2015 on a previous iteration of our site, helps students understand the basics.

What experience do they already have with reviews?

What is the role of criticism in our culture?

What are some guidelines for reading any review?

It can be taught as a whole, or you can just use the elements you need to get your students started.

Read mentor texts by adults and by teenagers, and try out some of the “writer’s moves.”

Making an argument via descriptive details with elizabeth, a winner of our 2019 student review contest takes us behind the scenes of her winning essay..

“There is no single term that can adequately define music sensation Lizzo, but bop star, band-geek-turned-pop-icon, classical flutist, self-love trailblazer and inclusivity advocate are all apt descriptors.” ”‘Lizzo in Concert, A Dynamic Reminder of the Power of Self-Acceptance’ by Elizabeth Phelps.” “The review is about a concert that I went to in Washington, D.C., and I went to see Lizzo.” “At her Washington, D.C. concert, she took the audience to church, and center stage, from a gold pulpit lit up with her name, Lizzo preached a message of joy, self-love and celebration.” “Yeah, I’d love to talk a little bit more about that theme of church that runs throughout. Can you tell me a little bit how you came up with that idea. And then how you developed it throughout the review?” “Sure. So, I came up with the idea for church because that’s really what the scene kind of looked and felt like the at the show itself, because she had like an actual podium and then there was like big stained glass windows looking things behind her. So it definitely had that vibe.” “Every ounce of her performance shone with positivity. Even before she appeared, the bright podium and large flats made to look like stained glass windows, gave the audience a taste of the revelry ahead.” “In history, like the Black church has been used to bring people together who may have been marginalized or diminished and passed aside, and I think that was kind of influenced by what was happening on stage, too, because it was another way that people were being unified and being uplifted, just like a church service would. So I tried to keep that theme going in a couple of ways.” “Then, clad in a silver leotard, she appeared at the pulpit and belted out the first song of her set: “Worship,” an anthem of confidence and self-love.” “An anthem, to me, is something, like the actual definition is a song that unifies a group of people for a particular cause. And I thought that that was so emblematic of what was happening because it was bringing everybody together, because the song is all about like, ‘worship me, I know I’m really awesome. And I’m really confident in myself.’ And I thought that it was a strong way to open with this anthem of like unifying all these people, being like, you can love yourself. I am confident in who I am.” “Therein lies the power of Lizzo’s music. It is a place for people of all colors, creeds and backgrounds to come together and celebrate self-acceptance and positivity.” “I really liked that line, too, because I thought it illustrated this unifying nature of what was happening, which I think is what the show was really about. It was about bringing people together and celebrating themselves and celebrating everybody’s differences and how they’re unique and important in their own way.” “The one thing that was very clear to me was the one thought that stuck in my head the whole time was I cannot let Lizzo down, I cannot do her dirty by writing a bad review, or a review that’s not up to the standard of what she has done.”

Our related Review Mentor Texts spotlight 10 pieces, five by Times critics from across the Arts and Culture sections, and five by teenage winners of our previous student review contests.

Each focuses on key elements of this kind of writing, and aligns with the criteria in our contest rubric:

Expressing Critical Opinions: Two Movie Reviews

Learning From Negative Reviews: ‘Aquaman’ and Mumble Rap

Making an Argument via Descriptive Detail: Two Music Reviews

Using Sensory Images: Restaurant Reviews

Addressing Audience: Two Book Reviews

Like all our editions in the Mentor Texts series, these include guidance on reading and analyzing the texts themselves, as well as a “Now Try This” exercise that lets students practice a specific technique or element.

We also provide over 25 additional mentor texts that review both the popular culture students are likely already familiar with — from Ariana Grande to Apple AirPods — as well as other works we think they may enjoy. The goal of this series is to demystify what good writing looks like, and encourage students to experiment with some of those techniques themselves.

And, of course, we always recommend learning from the teenage winners of our previous review contests. You can find winning work from 2020 , 2019 , 2018 , 2017 , 2016 and 2015 to show your students, and invite them to identify “writer’s moves” they’d like to emulate.

Finally, in the past year, we have added three additional resources via our Annotated by the Author series. Invite your students to learn from Manohla Dargis, The Times’s co-chief film critic, as she reveals her writing and research process for her review of the 2021 film “Dune.” Or, have students check out the work of two winners of our 2019 Student Review Contest: Elizabeth Phelps, who writes about why going to a Lizzo concert is like going to church , and Henry Hsiao who explains how he writes with his audience in mind .

Take Advice from Times Critics

In 2020, we interviewed four New York Times Critics — A.O. Scott, Maya Phillips, Jennifer Szalai, and Jon Pareles — and asked them to share their review writing advice for students. Among their suggestions: express a strong opinion, use descriptive details and don’t be afraid to edit. In our post “ Want to Write a Review? Here’s Advice From New York Times Critics ,” we pair the critics’ video interviews with reflection questions for students to consider as they write their own reviews.

We also have an earlier handout that features insights from more Times critics.

Finally, you can watch an edited version of our webinar “ How to Teach Review Writing With The New York Times ” below.

Enter our Review Contest.

By the end of the unit, your students will have read several mentor texts, practiced elements of review writing with each one, and, we hope, thought deeply about the role of criticism in our society in general.

Now we invite them to play critic and produce one polished piece of writing that brings it all together.

Part of the reason we created this contest is to encourage young people to stretch their cultural imaginations. We hope they’ll choose a work that is new and interesting for them, whether that’s a book, a movie, a television show, an album, a game, a restaurant, a building, or a live performance. We hope they’ll take close notes on their experiences, and tell us about it engagingly, making their case with voice and style.

All student work will be read by our staff, volunteers from the Times newsroom and/or by educators from around the country. Winners will have their work published on our site and, perhaps, in the print New York Times.

Our Seventh Annual Review Contest runs from Nov. 10 to Dec. 15, 2021. Visit this page for all the details.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Academic Writing Services

Cultural critique.

Cultural critique is a broad field of study that employs many different theoretical traditions to analyze and critique cultural formations. Because culture is always historically and con textually determined, each era has had to develop its own methods of cultural analysis in order to respond to new technological innovations, new modes of social organization, new economic formations, and novel forms of oppression, exploitation, and subjugation.

The modern European tradition of cultural critique can be traced back to Immanuel Kant’s (1724–1804) seminal essay entitled ‘‘What is Enlightenment?’’ Here, Kant opposed theocratic and authoritarian forms of culture with a liberal, progressive, and humanist culture of science, reason, and critique. By organizing society under the guiding principles of critical reason, Kant believed that pre Enlightenment superstition and ignorance would be replaced by both individual liberty and universal peace.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) historicized Kant’s version of critique through a technique called genealogy. Nietzsche argued that Kant’s necessary universals are born from historical struggles between competing interests. Compared to Greek culture, Nietzsche saw contemporary Germany as degenerate. Prominent figures such as David Strauss and Friedrich Schiller represented ‘‘cultural philistines’’ who promoted cultural conformity to a massified, standardized, and superficial culture. Thus contemporary culture blocked the revitalization of a strong, creative, and vital society of healthy geniuses. Here Nietzsche rested his faith not in universal categories of reason but rather in the aristocratic will to power to com bat the ‘‘herd mentality’’ of German mass culture.

Like Nietzsche, Karl Marx (1818–83) also rejected universal and necessary truths outside of history. Using historical materialism as his major critical tool, Marx argued that the dominant culture legitimated current exploitative economic relations. In short, the class that controls the economic base also controls the production of cultural and political ideas. Whereas Nietzsche traced central forms of mass culture back to the hidden source of power animating them, Marx traced cultural manifestations back to their economic determinates. Here culture is derived from antagonistic social relations conditioned by capitalism, which distorts both the content and the form of ideas. Thus for Marx, cultural critique is essentially ideological critique exposing the interests of the ruling class within its seemingly natural and universal norms.

Whereas Kant defined the proper uses of reason for the creation of a rational social order, Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) argued that the liberal humanist tradition failed to actualize its ideal because it did not take into account the eternal and unavoidable conflict between culture and the psychological unconscious. Freud argued that the complexity of current society has both positive and negative psychological implications. On the one hand, individuals have a certain degree of security and stability afforded to them by society. Yet at the same time, this society demands repression of aggressive instincts, which turn inward and direct themselves toward the ego. This internalization of aggression results in an overpowering super ego and attending neurotic symptoms and pathologies. For Freud, such a conflict is not the result of economic determination (as we saw with Marx), but rather is a struggle fundamental to the social contract and is increasingly exacerbated by the social demand for conformity, utility, and productivity.

With the Frankfurt School of social theory, cultural critique attempted to synthesize the most politically progressive and theoretically innovative strands of the former cultural theories. Max Horkheimer (1895–1971), Theodor Adorno (1903–69), and Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979) are three of the central members of the Frankfurt School who utilized a transdisciplinary method that incorporated elements of critical reason, genealogy, historical materialism, sociology, and psychoanalysis to analyze culture. While heavily rooted in Marxism, the members of the Frankfurt School increasingly distanced themselves from Marx’s conception of the centrality of economic relations, focusing instead on cultural and political methods of social control produced through new media technologies and a burgeoning culture industry. In the classic text Dialectic of Enlightenment (1948), Horkheimer and Adorno demonstrate that Kant’s reliance on reason has not resulted in universal peace but rather increasing oppression, culminating in fascism. Here reason becomes a new form of dogmatism, its own mythology predicated on both external domination of nature and internal domination of psychological drives. This dialectic of Enlightenment reason reveals itself in the rise of the American culture industry whose sole purpose is to produce docile, passive, and submissive workers. Marcuse argued along similar lines, proposing that the American ‘‘one dimensional’’ culture has effectively destroyed the capacity for critical and oppositional thinking. Thus many members of the Frankfurt School (Adorno in particular) adopted a highly pessimistic attitude toward ‘‘mass culture,’’ and, like Nietzsche, took refuge in ‘‘high’’ culture.

While the Frankfurt School articulated cultural conditions in a stage of monopoly capital ism and fascist tendencies, British cultural studies emerged in the 1960s when, first, there was widespread global resistance to consumer capitalism and an upsurge of revolutionary movements. British cultural studies originally was developed by Richard Hoggart, Raymond Williams, and E. P. Thompson to preserve working class culture against colonization by the culture industry. Thus both British cultural studies and the Frankfurt School recognized the central role of new consumer and media culture in the erosion of working class resistance to capitalist hegemony. Yet there are distinct differences between British cultural studies and proponents of Frankfurt School critical theory. Whereas the Frankfurt School turned toward the modernist avantgarde as a form of resistance to instrumental reason and capitalist culture, British cultural studies turned toward the oppositional potentials within youth subcultures. As such, British cultural studies was able to recognize the ambiguity of media culture as a contested terrain rather than a monolithic and one dimensional product of the capitalist social relations of production.

Currently, cultural critique is attempting to respond to a new era of global capitalism, hybridized cultural forms, and increasing control of information by a handful of media conglomerates. As a response to these economic, social, and political trends, cultural critique has expanded its theoretical repertoire to include multicultural, postcolonial, and feminist critiques of culture. African American feminist theorist bell hooks is an exemplary representative of new cultural studies who analyzes the interconnected nature of gender, race, and class oppressions operating in imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy. Scholars of color such as hooks and Cornell West critique not only ongoing forms of exclusion, marginalization, and fetishization of the ‘‘other’’ within media culture, but also the classical tools of cultural criticism. Through insights generated by these scholars, cultural criticism is reevaluating its own internal complicity with racism, sexism, colonialism, and homophobia and in the process gaining a new level of self reflexivity that enables it to become an increasingly powerful tool for social emancipation.

References:

- Durham, M. G. & Kellner, D. (2001) Media and Cultural Studies. Blackwell, Malden, MA.

- Freud, S. (1930) Civilization and its Discontents. J. Cape & H. Smith, New York.

- Kant, I. (1992) Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant. Ed. P. Guyer & A. Wood. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Kellner, D. (1989) Critical Theory, Marxism, and Modernity. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- Nietzsche, F. (1989) On the Genealogy of Morals and Ecce Homo. Vintage, New York.

- Tucker, R. (Ed.) (1978) The Marx Engels Reader. Norton, New York.

Back to Top

Back to Sociology of Culture .

- Hirsh Health Sciences

- Webster Veterinary

English: Introduction to Literary and Cultural Criticism

How to use this guide, literary & cultural criticism: background & context, literary & cultural critics / book reviews & bibliographies.

- Articles on Literature in English

- Articles on Related Subjects & Fields

- Books on Literary History, Theory, Criticism & More

- Professional Organizations

Meet Your Librarian

You Might Also Like...

- English Literature: Resources for Graduate Research by Micah Saxton Last Updated Apr 2, 2024 854 views this year

Welcome to the Introduction to Literary and Cultural Criticism Guide. Use the table of contents to find definitions, topic overviews, books, articles, and more that will help you with your research.

If you don't find what you are looking for or need help navigating this guide or any of the resources it contains, don't hesitate to contact the author of this guide or Ask a Librarian .

Want to learn more about the background and context of literary scholarship? Below is a selection of resources that can help you to develop a better understanding of literary research, including the discourses of critical theory.

Always remember that research is not a linear process--it takes a lot of moving back and forth between sources and ideas to understand a topic and how it has developed over time.

- A Dictionary of Critical Theory This is the most wide-ranging and up-to-date dictionary of critical theory available, covering the whole range of critical theory, including the Frankfurt school, cultural materialism, gender studies, literary theory, hermeneutics, historical materialism, and sociopolitical critical theory. Entries clearly explain even the most complex of theoretical discourses, such as Marxism, psychoanalysis, structuralism, deconstruction, and postmodernism.

- Critical Terms for Literary Study Each essay in this collection provides a concise history of a literary term, critically explores the issues and questions the term raises, and then puts theory into practice by showing the reading strategies the term permits.

- Key Terms in Literary Theory This book provides precise definitions of terms and concepts in literary theory, along with explanations of the major movements and figures in literary and cultural theory and an extensive bibliography.

- Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics is a comprehensive reference work dealing with all aspects of its subject: history, types, movements, prosody, and critical terminology.

- A History of Femnist Literary Criticism This book offers a comprehensive guide to the history and development of feminist literary criticism and a lively reassessment of the main issues and authors in the field.

- The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism presents a comprehensive historical survey of the field's most important figures, schools, and movements. It includes alphabetically arranged entries and subentries on critics and theorists, critical schools and movements, and the critical and theoretical innovations of specific countries and historical periods. In print in the library's reference collection (PN81.Z99 J64 1994)

- Oxford English Dictionary (OED) A complete text of the Oxford English dictionary with quarterly updates, including revisions not available in any other form.

The resources in this section provide information such as brief intellectual biographies of literary and cultural critics as well as annotations and reviews of the current scholarship on a topic.

I. Literary and Cultural Critics Dictionary of Literary Biography Complete Online Tip: what you are likely to find here This type of sources offer overviews and summaries; use them to gather, possibly, the following information: 1. A literary/cultural critics/theorist's contribution in the field of literature . * his/her "new" approach/method/theory * his/her "impact" on the scholarship of a particular type of literature 2. Seminal publications by and about a critic/theorist (as mentioned in the essays and listed in the bibliographies) * note authors/scholars who are experts on the critic or the theory * note major journals in the fields, where you are likely to find current scholarship on your topics. * Are there scholars/journals from other fields as well? 3. People, events, ... related to an art historian * how a critic/theorist is shaped by his/her education; * who or what influenced their theory; * what was the field of study like prior. II. Recent Bibliographies & Reviews of Books Literary and Critical Theory (an annotated bibliography) The Year's Work in Critical and Cultural Theory Dissertations and Theses ( Check out the bibliographies of recent dissertations on a topic. ) Dissertation Reviews ( yet to be published, which " offer a glimpse of each discipline's immediate present ") H-Net Reviews in the Humanities and Social Sciences (1994 - ) New York Review of Books (1963 - ) Tip: Questions to ask about reviews of books 1. You might consider such questions as: Does the reviewer agree or disagree with the book’s theses and approaches? Does the reviewer provide new evidence not included in the book? What does the reviewer see as the relevance of the book? What questions not included in the book does the reviewer identify? Based on this book review, what do you think are a few of the major questions or methodologies being used in your chosen field? 2. What's the next larger context? When there Aren't any (or many) books published on your topic, try place your idea in the knowledge hierarchy. For examples: connect Michelangelo's Sistine Ceiling with 16th-century Italian art, focusing on patronage in Rome during the Renaissance and Baroque periods; or, dealing with influential Italian artists through history, etc.?

- Next: Articles on Literature in English >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2023 2:17 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.tufts.edu/c.php?g=711992

Introduction: Rethinking Cultural Criticism—New Voices in the Digital Age

- First Online: 01 December 2020

Cite this chapter

- Nete Nørgaard Kristensen 4 ,

- Unni From 5 &

- Helle Kannik Haastrup 4

649 Accesses

In this introduction, we outline the book’s overall take on the rethinking of cultural criticism in the digital age. First, we outline the book’s approach to its two key concepts, culture and criticism. Our goal is not to offer an exhaustive definition of either concept but to provide a context for the subsequent chapters and how they contribute new theoretical and empirical perspectives to current understandings of cultural criticism. Second, we contextualize the book in broader scholarly debates about changing notions of cultural authority and expertise in the digital age, occasioned by the hybrid media ecology and its intertwined mass media and social media logics, and how these developments reconfigure traditional valorization circuits and modes of performing cultural criticism. Finally, we summarize how the chapters in the book address these newer conditions for and dimensions of cultural criticism in the digital age.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Anderson, C. (2008). Journalism: Expertise, authority, and power in democratic life, chap. 17. In D. Hesmondhalgh & J. Toynbee (Eds.), The Media and Social Theory . London: Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780203930472/chapters/10.4324/9780203930472-24 .

Anker, E., & Felski, R. (2017). Critique and Postcritique . North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Google Scholar

Bielby, D. D., Moloeny, M., & Ngo, B. (2005). Aesthetics of Television Criticism: Mapping Critics’ Reviews in an Era of Industry Transformation. In C. Jones & P. H. Thornton (Eds.), Transformation in Cultural (pp. 1–43). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Blank, G. K. (2007). Critics, Ratings, and Society . Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Bordwell, D. (1989). Making Meaning . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Carroll, N. (2009). On Criticism . New York: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Chadwick, A. (2013). The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chong, P. (2019). Valuing Subjectivity in Journalism: Bias, Emotions, and Self-Interest as Tools in Arts Reporting. Journalism, 20 (3), 427–443.

Article Google Scholar

Chong, P. (2020). Inside the Critic’s Circle . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cultural Critique. (1985). Prospectus. Cultural Critique, 1 (Autumn), 5–6. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1354279.pdf .

Duffy, E. (2015). The Romance of Work: Gender and Aspirational Labour in the Digital Culture Industries. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 19 (4), 441–457.

Frey, M. (2015). The Permanent Crisis of Film Criticism: An Anxiety of Authority . Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Frey, M., & Sayad, C. (Eds.). (2015). Film Criticism in the Digital Age . London: Rutgers University Press.

From, U. (2019). Criticism and Reviews. The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies . Wiley.

Gans, H. J. (1999). Popular Culture and High Culture (rev. ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Genders, A. (2020). BBC Arts Programming: A Service for Citizens or a Product for Consumers? Media, Culture and Society, 42 (1), 58–74.

Gibbs, M., Meese, J., Arnold, M., Nansen, B., & Carter, M. (2015). #Funeral and Instagram: Death, Social Media, and Platform Vernacular. Information, Communication, Society, 18 (3), 255–268.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-identity . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Habermas, J. (1989). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere . Boston: MIT Press.

Hellman, H., Larsen, L. O., Riegert, K., Widholm, A., & Nygaard, S. (2017). What Is Cultural News Good For? Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish Cultural Journalism in Public Service Organisations. In N. N. Kristensen & K. Riegert, K. (Eds.), Cultural Journalism in the Nordic Countries (pp. 111–134). Göteborg: Nordicom.

Hovden, J. F., & Knapskog, K. A. (2015). Doubly Dominated: Cultural Journalists in the Fields of Journalism and Culture. Journalism Practice, 9 (6), 791–810.

Hutchinson, J. (2017). Cultural Intermediaries . London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jaakkola, M. (2018). Vernacular Reviews as a Form of Co-consumption: The User-Generated Review Videos on YouTube. MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research, 34 (65), 10–20.

Kammer, A. (2015). Post-Industrial Cultural Criticism: The Everyday Amateur Expert and the Online Cultural Public Sphere. Journalism Practice, 9 (6), 872–889.

Klein, B. (2005). Dancing About Architecture: Popular Music Criticism and the Negotiation of Authority. Journal of Popular Communication, 3 (1), 1–20.

Kristensen, N. N., & From, U. (2015). From Ivory Tower to Cross-Media Personas—The Heterogeneous Cultural Critic in the Media. Journalism Practice, 9 (6), 853–871.

Kristensen, N. N., & From, U. (2018). Cultural Journalists on Social Media. MedieKultur, 65, 76–97.

Kristensen, N. N., & Haastrup, H. K. (2018). Cultural Critique: Re-negotiating Cultural Authority in Digital Media Culture. MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research, 34 (65), 3–9.

Lewis, T. (2008). Smart Living . New York: Peter Lang.

Marshall, P. D. (2010). The Promotion and Presentation of the Self: Celebrity as Marker of Presentational Media. Celebrity Studies, 1 (1), 35–48.

Marwick, A. E. (2015). Instafame: Luxury Selfies in the Attention Economy. Public Culture, 27 (1), 137–160.

McDonald, R. (2007). The Death of the Critic . London: Continuum.

McWhirter, A. (2016). Film Criticism and Digital Cultures: Journalism, Social Media and the Democratisation of Opinion . London: I.B. Tauris.

Nichols, T. (2017). The Death of Expertise. The Campaign against Established Knowledge and Why it Matters . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nowotny, H., Scott, P., & Gibbons, M. (2001). Re-Thinking Science. Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty . Cambridge: Polity.

Orlik, P. (2016). Media Criticism in a Digital Age: Professional and Consumer Considerations . New York: Routledge.

Poole, M. (1984). The Cult of the Generalist—British Television Criticism 1936–83. Screen, 25 (2), 41–61.

Purhonen, S., Heikkilä, R., Karademir Hazir, I. K., Lauronen, T., Fernández Rodríguez, C. J., & Gronow, J. (2019). Enter Culture, Exit Arts? In The Transformation of Cultural Hierarchies in European Newspaper Culture Sections, 1960–2010 . London: Routledge.

Rixon, P. (2011). TV Critics and Popular Culture: A History of British Television Criticism . London: I.B. Tauris.

Rixon, P. (2015). Radio and Popular Journalism in Britain: Early Radio Critics and Radio Criticism. Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast & Audio Media, 13 (1), 23–36.

Titchener, C. B. (1998). Reviewing the Arts . Manwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

van Dijck, J., & Poell, T. (2013). Understanding Social Media Logic. Media and Communication, 1 (1), 2–14.

van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & de Waal, M. (2018). The Platform Society . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Verboord, M. (2014). The Impact of Peer-Produced Criticism on Cultural Evaluation: A Multilevel Analysis of Discourse Employment in Online and Offline Film Reviews. New Media & Society, 16 (6), 921–940.

Williams, R. (1976/1984). Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society . London: Routledge.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

Nete Nørgaard Kristensen & Helle Kannik Haastrup

Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nete Nørgaard Kristensen .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Nete Nørgaard Kristensen

Helle Kannik Haastrup

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Kristensen, N.N., From, U., Haastrup, H.K. (2021). Introduction: Rethinking Cultural Criticism—New Voices in the Digital Age. In: Kristensen, N.N., From, U., Haastrup, H.K. (eds) Rethinking Cultural Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7474-0_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7474-0_1

Published : 01 December 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-15-7473-3

Online ISBN : 978-981-15-7474-0

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

postcolonialism

More Like This

Show all results sharing these subjects:

- Literary studies (19th century)

cultural criticism

Quick reference.

In literary studies, the term cultural criticism is sometimes used very broadly to refer to any consideration of literature in relation to the culture within which it was produced and/or ...

From: cultural criticism in The Oxford Companion to the Brontës »

Subjects: Literature — Literary studies (19th century)

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries.

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'cultural criticism' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 12 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Character limit 500 /500

The ten best culture criticism reads

On the eve of lynne tillman's new essay collection, we chart our top picks for reading beyond the obvious.

It could be said, with an eye roll or sardonic sigh, that the late-20th-century’s New Journalism gave way to (pop) cultural criticism gave way to, ahem, BuzzFeed. But that linear evolution leaves out a lot of really smart shit. Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem , John Jeremiah Sullivan’s Pulphead , Consider the Lobster – what anyone who knows anything about what university departments sometimes call "creative nonfiction" worships at the alter of these precursors of the self-satisfied grad student blogger, and rightly so: nonfiction often feels more direct – and more interactive – than fiction or poetry. Plus, who doesn’t love a good nuanced take on an interesting cultural figure or phenomenon?

Next week, the possibly unfairly esoteric but beloved art/culture critic Lynne Tillman will release her new essay collection, What Would Lynne Tillman Do? , through the indie publisher Red Lemonade, and it’s cause to revisit writers who face the line between themselves and the culture head on. Check out our picks for reading that goes beyond the obvious.

MY 1980S AND OTHER ESSAYS BY WAYNE KOESTENBAUM

The Venn diagram of criticism and manifesto has a large overlap, and we wouldn’t have it any other way. Koestenbaum’s understanding of major cultural/artistic figures from John Ashbury to Lana Turner is idiosyncratic without being annoying, forceful while leaving room for readers to have the oh-my-God realizations that make reading really good essays feel really good.

FORTY-ONE FALSE STARTS: ESSAYS ON ARTISTS AND WRITERS BY JANET MALCOLM

Malcolm is known for her sometimes-seething criticism, and this collection of essays on well-known artists and writers certainly does not fall into the category of blind praise. The journalist turns what start out as profiles into complicated meditations on the nature of art and literature that press hard on easy understandings of either.

WHITE GIRLS BY HILTON ALS

In this hotly anticipated genre-bender out from McSweeney’s last year, Als plays with form to craft an elegant argument out of material not always strictly nonfictional, and the result feels more truthful than what we might consider strictly truth. His challenge of the idea of categories umbrellas his experiments with form and drives home insights on race, gender, sexuality, art—all the good stuff, basically.

THIS IS RUNNING FOR YOUR LIFE BY MICHELLE ORANGE

A lot of emphasis on the status quo circles back to the fucking thereof, but Orange’s 2013 collection is more about a subtle showcasing of why it’s fucked up. Her subjects range from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders to Hawaii, but they’re connected by a critique of a society more and more mediated by, well, media, as well as Orange’s funny, intimate personal stories.