Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Gratitude Defined

What is gratitude.

Robert Emmons, perhaps the world’s leading scientific expert on gratitude, argues that gratitude has two key components, which he describes in a Greater Good essay, “ Why Gratitude Is Good .”

“First,” he writes, “it’s an affirmation of goodness. We affirm that there are good things in the world, gifts and benefits we’ve received.”

In the second part of gratitude, he explains, “we recognize that the sources of this goodness are outside of ourselves. … We acknowledge that other people—or even higher powers, if you’re of a spiritual mindset—gave us many gifts, big and small, to help us achieve the goodness in our lives.”

Emmons and other researchers see the social dimension as being especially important to gratitude. “I see it as a relationship-strengthening emotion,“ writes Emmons, “because it requires us to see how we’ve been supported and affirmed by other people.”

Because gratitude encourages us not only to appreciate gifts but to repay them (or pay them forward), the sociologist Georg Simmel called it “the moral memory of mankind.” This is how gratitude may have evolved : by strengthening bonds between members of the same species who mutually helped each other out.

To investigate how gratitude relates to bonding and empathy, pioneering research is exploring what gratitude looks like in the brain .

For more: Read The Gratitude Project , a new book by the GGSC, to learn how gratitude can lead to a better life and a better world. Get an in-depth overview of where gratitude comes from, what its benefits are, and how to cultivate it in our special white paper on the science of gratitude . Also check out the GGSC’s Expanding the Science and Practice of Gratitude project .

What are the Limitations?

Five Ways Giving Thanks Can Backfire

Most of the time, gratitude is good. But research finds that there are situations when…

When Guilt Stops Gratitude

Why do we sometimes respond with resentment, not gratitude, when people are good to us?…

What Gets in the Way of Gratitude?

What must we overcome as a culture or as individuals for gratitude to flourish? The key,…

Featured Articles

Your Happiness Calendar for April 2024

This month, play and find joy.

Why We Should Share Our Good News (Not Just Our Struggles)

A new study suggests that when people respond enthusiastically to our good news, we feel more grateful and closer to them—especially as we age.

Seven Reminders for How to Live Well in 2024

If all your goals and good intentions seem to fall by the wayside soon after New Year's, try getting back to basics.

The Best Greater Good Articles of 2023

We round up the most-read and highly rated Greater Good articles from the past year.

The Top 10 Insights from the “Science of a Meaningful Life” in 2023

Our team names the most provocative and influential findings published during this past year.

Greater Good Resources for Thriving Over the Holidays

We gathered articles that explore holiday stress management, managing conflict, picking gifts, making resolutions, and more.

Why Practice It?

Over the past 15 years, hundreds of studies have documented the social , physical , and psychological benefits of gratitude . The research suggests these benefits are available to most anyone who practices gratitude, even in the midst of adversity , such as elderly people confronting death , women with breast cancer , and people coping with a chronic muscular disease. Here are some of the top research-based reasons for practicing gratitude.

- Gratitude brings us happiness : Through research by Robert Emmons, happiness expert Sonja Lyubomirsky, and many other scientists, practicing gratitude has proven to be one of the most reliable methods for increasing happiness and life satisfaction; it also boosts feelings of optimism , joy, pleasure, enthusiasm, and other positive emotions.

- On the flip side, gratitude also reduces anxiety and depression and could be a helpful part of therapy . Research suggests it may help reduce depression among people with chronic disease.

- Gratitude is good for our bodies : Studies by Emmons and his colleague Michael McCullough suggest gratitude strengthens the immune system, lowers blood pressure, reduces symptoms of illness, and makes us less bothered by aches and pains. It also encourages us to exercise more and take better care of our health.

- Grateful people sleep better : They get more hours of sleep each night, spend less time awake before falling asleep, and feel more refreshed upon awakening. If you want to sleep more soundly, count blessings, not sheep.

- Gratitude makes us more resilient : It has been found to help people recover from traumatic events, including Vietnam War veterans with PTSD, victims of natural disasters, and people living under violent, political conflict .

- Gratitude strengthens relationships : It makes us feel closer and more committed to friends and romantic partners . When partners feel and express gratitude for each other , they each become more satisfied with their relationship . Gratitude may also encourage a more equitable division of labor between partners.

- Gratitude promotes forgiveness —even between ex-spouses after a divorce.

- Gratitude makes us “ pay it forward ”: Grateful people are more helpful , altruistic , and compassionate—in other words, more prosocial .

- Gratitude is good for kids : Children as young as six or seven are more generous when they’re feeling grateful, and grateful adolescents tend to be more resilient . When 10-19 year olds practice gratitude, they report greater life satisfaction and more positive emotion, and they feel more connected to their community .

- Gratitude is good for schools : Studies suggest it makes students feel better about their school; it also makes teachers feel more satisfied and accomplished, and less emotionally exhausted, possibly reducing teacher burnout.

For more: Read Emmons’ essay about “ Why Gratitude is Good ” and Giacomo Bono’s essay on “ What We Still Don’t Know about Gratitude and Youth .”

How Do I Cultivate It?

Are you a natural pessimist? Take heart: The benefits of gratitude aren’t only available to people with a naturally grateful disposition. Instead, feeling grateful is a skill we can develop with practice, reaping its rewards along the way. Here are some specific, science-based activities for cultivating an attitude of gratitude from our new site Greater Good in Action :

- Three Good Things: A way to tune into the positive events in your life.

- Gratitude Letter: Write a letter expressing thanks, and deliver it in person.

- Mental Subtraction of Positive Events : How to appreciate what you have by imagining your life without it. One variation on this practice is Mental Subtraction of Relationships.

- Savoring Walk: How a stroll outside can help build lasting happiness.

- Give It Up : Savor something more by taking a break from it.

And here are more of the most effective ways to cultivate gratitude, according to research.

- Keep a gratitude journal , recording three to five things for which you’re grateful every day or week. Because some evidence suggests that how we keep a gratitude journal—for instance, how often we write in it or whether we express our gratitude to others —can influence its impact, the GGSC’s Jason Marsh offers these research-based tips for gratitude journaling. Apply these tips through the GGSC’s new and easy-to-use online gratitude journal, Thnx4.org .

- Write a “gratitude letter” to an important person in your life whom you’ve never properly thanked. Research suggests gratitude letters provide strong and long-lasting happiness boosts , especially when they’re delivered in person. When participants in her studies write gratitude letters, Sonja Lyubomirsky provides them with these instructions .

- Savor the good in your life—don’t just gloss over the beauty and pleasures that come your way. Loyola University psychologist Fred Bryant has identified 10 ways to practice savoring ; GGSC advisory board member Rick Hanson has developed his own method for savoring positive emotions and experiences, which he calls “ taking in the good .“

- Focus on intentions: When you receive a gift, or when something good happens to you in general, consider how someone tried on purpose to bring that goodness into your life, even at a cost to themselves. Research suggests this goes a long way toward cultivating “an attitude of gratitude,“ among children and adults alike.

- Create a grateful school climate by fostering gratitude among staff and working to counter the culture of complaining .

- Create a grateful workplace by getting buy-in from leaders, providing lots of opportunities for gratitude, and making sure that everyone gets thanked.

- Recognize the positive: The GGSC’s Christine Carter asks her daughters about three good things that happen to them each day—a way to help them appreciate the gifts big and small that come their way.

- Get metaphysical: Research suggests that thinking hard about our own mortality makes us more grateful for life; another study found that praying more often increases gratitude .

For more: Check out Emmons’ 10 Ways to Become More Grateful ; learn about the six habits of highly grateful people ; and read journalist Catherine Price’s entertaining article about how she tested gratitude practices on herself. And don’t forget to start counting your blessings through the GGSC’s online gratitude journal, Thnx4 !

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

Advertisement

Supported by

Toni Morrison: ‘Goodness: Altruism and the Literary Imagination’

- Share full article

By Toni Morrison

- Aug. 7, 2019

Toni Morrison spoke at Harvard Divinity School on the subject of altruism in 2012. Her lecture is published here for the first time.

On an October morning in 2006, a young man backed his truck into the driveway of a one-room schoolhouse. He walked into the school and after ordering the boy students, the teacher and a few other adults to leave, he lined up 10 girls, ages 9 to 13, and shot them. The mindless horror of that attack drew intense and sustained press as well as, later on, books and film. Although there had been two other school shootings only a few days earlier, what made this massacre especially notable was the fact that its landscape was an Amish community — notoriously peaceful and therefore the most unlikely venue for such violence.

Before the narrative tracking the slaughter had been exhausted in the press, another rail surfaced, one that was regarded as bizarre and somehow as shocking as the killings. The Amish community forgave the killer, refused to seek justice, demand vengeance, or even to judge him. They visited and comforted the killer’s widow and children (who were not Amish), just as they embraced the relatives of the slain. There appeared a number of explanations for their behavior — their historical aversion to killing anyone at all for any reason and their separatist convictions. More to the point, the Amish community had nothing or very little to say to outside inquiry except that it was God’s place to judge, not theirs. And, as one cautioned, “Do not think evil of this man.” They held no press conferences and submitted to no television interviews. They quietly buried the dead, attended the killer’s funeral, then tore down the old schoolhouse and built a new one.

Their silence following the slaughter, along with their deep concern for the killer’s family, seemed to me at the time characteristic of genuine “goodness.” And I became fascinated with the term and its definition.

Thinkers, of whom none was as uninformed as I was, have long analyzed what constitutes goodness, what good is good, and what its origins are or may be. The myriad theories I read overwhelmed me, and to reduce my confusion I thought I should just research the term “altruism.” I quickly found myself on a frustrating journey into a plethora of definitions and counterdefinitions. I began by thinking of altruism as a more or less faithful rendition of its Latin root: alter/other; selfless compassion for the “other.” That route was not merely narrow; it led to a swamp of interpretations, contrary analyses, and doubt. A few of these arguments posited wildly different explanations: (1) Altruism is not an instinctive act of selflessness, but a taught and learned one. (2) Altruism might actually be narcissism, ego enhancement, even a mental disorder made manifest in a desperate desire to think well of oneself to erase or diminish self-loathing. (3) Some of the most thought-provoking theories came from scholarship investigating the DNA, if you will, seeking evidence of an embedded gene automatically firing to enable the sacrifice of oneself for the benefit of others; a kind of brother or sister to Darwin’s “survival of the fittest.” Examples of confirmation or contradiction of the Darwinian theory came primarily from the animal and insect kingdoms: squirrels deliberately attracting predators to themselves to warn the other squirrels; birds as well and especially ants, bees, bats all in service to the colony, the collective, the swarm. Such behavior is very common among humans. But the question being put seemed to be whether such sacrifice for kin and/or community is innate, built, as it were, into our genes just as individual conquest of others is held to be a natural, instinctive drive that serves evolution. Is there a “good” gene along with a “selfish” gene? The further question for me was the competition between the gene and the mind.

I confess I was unable and ill equipped to understand much of the scholarship on altruism, but I did learn something about its weight, its urgency, and its relevance and irrelevance in contemporary thought.

Keeping those Amish in mind, I wondered why the narrative of that event, in the press and visual media, quickly ignored the killer and the slaughtered children and began to focus almost exclusively on the shock of forgiveness. As I noted earlier, mass shootings at schools were perhaps too ordinary; there had been two such shootings elsewhere during that same time, but the Amish community’s unwillingness to clamor for justice/vengeance/retribution, or even to judge the killer was the compelling story. The shock was that the parents of the dead children took pains to comfort the killer’s widow, her family and her children, to raise funds for them, not themselves. Of the victimized community’s response to that almost classic example of evil, in addition to their refusal to fix blame, the most extraordinary element was their silence. It was that silence (that refusal to be lionized, televised) that caused me to think differently about goodness.

Of course thinking about goodness implies, indeed requires, a view of its opposite.

I have never been interested in or impressed by evil itself, but I have been confounded by how attractive it is to others. I am stunned by the attention given to its every whisper and shout. Which is not to deny its existence and ravage, nor to suggest evil does not demand confrontation, but simply to wonder why it is so worshiped, especially in literature. Is it its theatricality, its costume, its blood spray, the emotional satisfaction that comes with its investigation more than with its collapse? (The ultimate detective story, the paradigm murder mystery.) Perhaps it is how it dances, the music it inspires, its clothing, its nakedness, its sexual disguise, its passionate howl, and its danger. The formula in which evil reigns is bad versus good, but the deck is stacked because goodness in contemporary literature seems to be equated with weakness, as pitiful (a girl running frightened and helpless through the woods while the pursuing villain gets more of our attention than her savior).

Evil has a blockbuster audience; Goodness lurks backstage. Evil has vivid speech; Goodness bites its tongue. It is Billy Budd, who can only stutter. It is Coetzee’s Michael K, with a harelip that so limits his speech that communication with him is virtually impossible. It is Melville’s Bartleby, confining language to repetition. It is Faulkner’s Benjy, an idiot.

Rather than rummage through the exquisite and persuasive language of religions — all of which implore believers to rank goodness as the highest and holiest of human achievement, and many of which identify their saints and icons of worship as examples of pure altruism — I decided to focus on the role goodness plays in literature using my own line of work — fiction — as a test.

In 19th-century novels, regardless of what acts of wickedness or cruel indifference controlled the plot, the ending was almost always the triumph of goodness. Dickens, Hardy, and Austen all left their readers with a sense of the restoration of order and the triumph of virtue, even Dostoyevsky. Note that Svidrigailov in “Crime and Punishment,” exhausted by his own evil and the language that supports it, becomes so bored by his terminal acts of charity, he commits suicide. He cannot live without the language of evil, nor within the silence of good deeds. There are famous exceptions to what could be called a 19th-century formula invested in identifying clearly who or what is good. Obviously “Don Quixote” and “Candide” both mock the search for pure goodness. Other exceptions to that formula remain puzzles in literary criticism: Melville’s “Billy Budd” and “Moby-Dick,” both of which support multiple interpretations regarding the rank, the power, the meaning that goodness is given in these texts. The consequence of Billy Budd’s innocence is execution. Is Ishmael good? Is Ahab a template for goodness, fighting evil to the death? Or is he a wounded, vengeful force outfoxed by indifferent nature, which is neither good nor bad? Innocence represented by Pip we know is soon abandoned, swallowed by the sea without a murmur. Generally, however, in 19th-century literature, whatever the forces of malice the protagonist is faced with, redemption and the triumph of virtue was his or her reward.

Twentieth-century novelists were unimpressed. The movement away from happy endings or the enshrining of good over evil was rapid and stark after World War I. That catastrophe was too wide, too deep to ignore or to distort with a simplistic gesture of goodness. Many early modern novelists, especially Americans, concentrated on the irredeemable consequences of war — the harm it did to its warriors, to society, to human sensibility. In those texts, acts of sheer goodness, if not outright comical, are treated with irony at best or ladled with suspicion and fruitlessness at worst. One thinks of Faulkner’s “A Fable” and the mixed reviews it received, most of which were disdainful of the deliberate armistice between soldiers in trench warfare against each other driven by a Christ-like character. The term “hero” seems to be limited these days to the sacrificing dead: first responders running into fiery buildings, mates throwing themselves on grenades to save the lives of others, rescuing the drowning, the wounded. Faulkner’s character would never be seen or praised as a hero.

Evil grabs the intellectual platform and its energy; it demands careful examinations of its consequences, its techniques, its motives, its successes however short-lived or temporary. Grief, melancholy, missed chances for personal happiness often seem to be contemporary literature’s concept of evil. It hogs the stage. Goodness sits in the audience and watches, assuming it even has a ticket to the show. A most compelling example of this obsession with evil is Umberto Eco’s “The Prague Cemetery.” Brilliant as it is, never have I read a more deeply disturbing fascination with the nature of evil; disturbing precisely because it is treated as a thrilling intelligence scornful of the monotony and stupidity of good intentions.

Contemporary literature is not interested in goodness on a large or even limited scale. When it appears, it is with a note of apology in its hand and has trouble speaking its name. For every “To Kill a Mockingbird,” there is a Flannery O’Connor’s “Wise Blood” or “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” striking goodness down with a well-honed literary ax. Many of the late 20th-, early 21st-century heavyweights — Philip Roth, Norman Mailer, Saul Bellow and so on — are masters at exposing the frailty, the pointlessness, the comedy of goodness.

I thought it would be interesting and possibly informative to examine my thesis on the life and death of goodness in literature using my own work. I wanted to measure and clarify my understanding by employing the definitions of altruism that I gleaned from my tentative research. To this end, I selected three:

1. Goodness taught and learned (a habit of helping strangers and/or taking risks for them).

2. Goodness as a form of narcissism, ego enhancement or even a mental disorder.

3. Goodness as instinct, as a result of genetics (protecting one’s kin or one’s group).

An example of the first: A learned habit of goodness can be found in “A Mercy.” There a priest, at some danger to himself, teaches female slaves to read and write. Lest this be understood as simple kindness, here is a sample of punishments levied on white people who risked promoting literacy among black people: “Any white person assembling with slaves or free Negroes for purpose of instructing them to read or write, or associating with them in any unlawful assembly, shall be confined in jail not exceeding six months and fined not exceeding $100.00.” That text appeared in Virginia’s criminal law as late as 1848.

Examples of the third: Instinctive kin protection is the most common representative of goodness — and I acknowledge several areas of failure to articulate them. From the deliberate sticking of one’s leg under a train for insurance money to raise their family in “Sula,” to setting a son on fire to spare him and others the sight of his self-destruction. Note this is the same mother who throws herself out of a window to save a daughter from fire. These acts are far too theatrical and are accompanied by no compelling language. On the other hand, there is the giving away of one’s child to a stranger in order to save her from certain molestation in “A Mercy.” The motive that impels Florens’s mother, a minha mae , seems to me quite close to altruism, and most importantly is given language which I hoped would be a profound, a literal definition of freedom: “To be given dominion over another is a hard thing; to wrest dominion over another is a wrong thing; to give dominion of yourself to another is an evil thing.”

Another example of the third: Unquestioning compassion in support of not just kin but of members of the group in general. In “Home,” for example, women provide unsolicited but necessary nursing care to a member of the collective who has spent a lifetime despising them; their “reason” being responsibility to God: “They did not want to meet their Maker and have nothing to say when He asked, ‘What have you done?’” A further instance of innate group compassion is the healing of Cee, physically as well as mentally. It was important to me to give that compassion voice: “Look to yourself,” Miss Ethel tells her. “You free. Nothing and nobody is obliged to save you but you … You young and a woman and there is serious limitation in both but you a person, too … Somewhere inside you is that free person … Locate her and let her do some good in the world.”

An example of the second: Goodness as a form of narcissism, perhaps mental disorder, occurs in the very first novel I wrote. Determined to erase his self-loathing, Soaphead Church, a character in “The Bluest Eye,” chooses to “give,” or pretend to give, blue eyes to a little girl in psychotic need of them. In his letter to God, he imagines himself doing the good God refuses. Misunderstood as it is, it has language.

Over time, these last 40 years, I have become more and more invested in making sure acts of goodness (however casual or deliberate or misapplied or, like the Amish community, blessed) produce language. But even when not articulated, like the teaching priest in “A Mercy,” such acts must have a strong impact on the novel’s structure and on its meaning. Expressions of goodness are never trivial or incidental in my writing. In fact, I want them to have life-changing properties and to illuminate decisively the moral questions embedded in the narrative. It was important to me that none of these expressions be handled as comedy or irony. And they are seldom mute.

Allowing goodness its own speech does not annihilate evil, but it does allow me to signify my own understanding of goodness: the acquisition of self-knowledge. A satisfactory or good ending for me is when the protagonist learns something vital and morally insightful that she or he did not know at the beginning.

Claudia’s words, at the end of “The Bluest Eye”: “I even think now that the land of the entire country was hostile to marigolds that year. This soil is bad for certain kinds of flowers. Certain seeds it will not nurture, certain fruit it will not bear, and when the land kills of its own volition, we acquiesce and say the victim had no right to live. We are wrong of course but it doesn’t matter. It’s too late. At least on the edge of my town, among the garbage and sunflowers of my town, it’s much, much, much too late.”

Such insight has nothing to do with winning, and everything to do with the acquisition of knowledge. Knowledge on display in the language of moral clarity — of goodness.

Toni Morrison’s lecture will be reprinted in “Goodness and the Literary Imagination,” edited by Davíd Carrasco, Stephanie Paulsell and Mara Willard, to be published by the University of Virginia Press in October.

Follow New York Times Books on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram , s ign up for our newsletter or our literary calendar . And listen to us on the Book Review podcast .

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Salman Rushdie’s new memoir, “Knife,” addresses the attack that maimed him in 2022, and pays tribute to his wife who saw him through .

Recent books by Allen Bratton, Daniel Lefferts and Garrard Conley depict gay Christian characters not usually seen in queer literature.

What can fiction tell us about the apocalypse? The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward .

At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled voice of a generation in Māori writing .

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race.

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Goodness and the Literary Imagination

Harvard's 95th ingersoll lecture with essays on morrison's moral and religious vision, toni morrison. edited by david carrasco, stephanie paulsell, and mara willard.

- Literary Criticism

- Author Bio(s)

What exactly is goodness? Where is it found in the literary imagination? Toni Morrison, one of American letters’ greatest voices, pondered these perplexing questions in her celebrated Ingersoll Lecture, delivered at Harvard University in 2012 and published now for the first time in book form.

Perhaps because it is overshadowed by the more easily defined evil, goodness often escapes our attention. Recalling many literary examples, from Ahab to Coetzee’s Michael K, Morrison seeks the essence of goodness and ponders its significant place in her writing. She considers the concept in relation to unforgettable characters from her own works of fiction and arrives at conclusions that are both eloquent and edifying. In a lively interview conducted for this book, Morrison further elaborates on her lecture’s ideas, discussing goodness not only in literature but in society and history—particularly black history, which has responded to centuries of brutality with profound creativity.

Morrison’s essay is followed by a series of responses by scholars in the fields of religion, ethics, history, and literature to her thoughts on goodness and evil, mercy and love, racism and self-destruction, language and liberation, together with close examination of literary and theoretical expressions from her works. Each of these contributions, written by a scholar of religion, considers the legacy of slavery and how it continues to shape our memories, our complicities, our outcries, our lives, our communities, our literature, and our faith. In addition, the contributors engage the religious orientation in Morrison’s novels so that readers who encounter her many memorable characters such as Sula, Beloved, or Frank Money will learn and appreciate how Morrison’s notions of goodness and mercy also reflect her understanding of the sacred and the human spirit.

- P.O. Box 400318 (Postal)

- Charlottesville, VA 22904-4318

- 210 Sprigg Lane (Courier)

- Charlottesville, VA 22903-2417

- 434 924-3468 (main)

- 1-800-831-3406 (toll-free)

- 434 982-2655 (fax)

- General Inquiries

- Staff Directory

Would you like to explore a topic?

- LEARNING OUTSIDE OF SCHOOL

Or read some of our popular articles?

Free downloadable english gcse past papers with mark scheme.

- 19 May 2022

How Will GCSE Grade Boundaries Affect My Child’s Results?

- Akshat Biyani

- 13 December 2021

The Best Free Homeschooling Resources UK Parents Need to Start Using Today

- Joseph McCrossan

- 18 February 2022

How to Write the Perfect Essay: A Step-By-Step Guide for Students

- June 2, 2022

- What is an essay?

What makes a good essay?

Typical essay structure, 7 steps to writing a good essay, a step-by-step guide to writing a good essay.

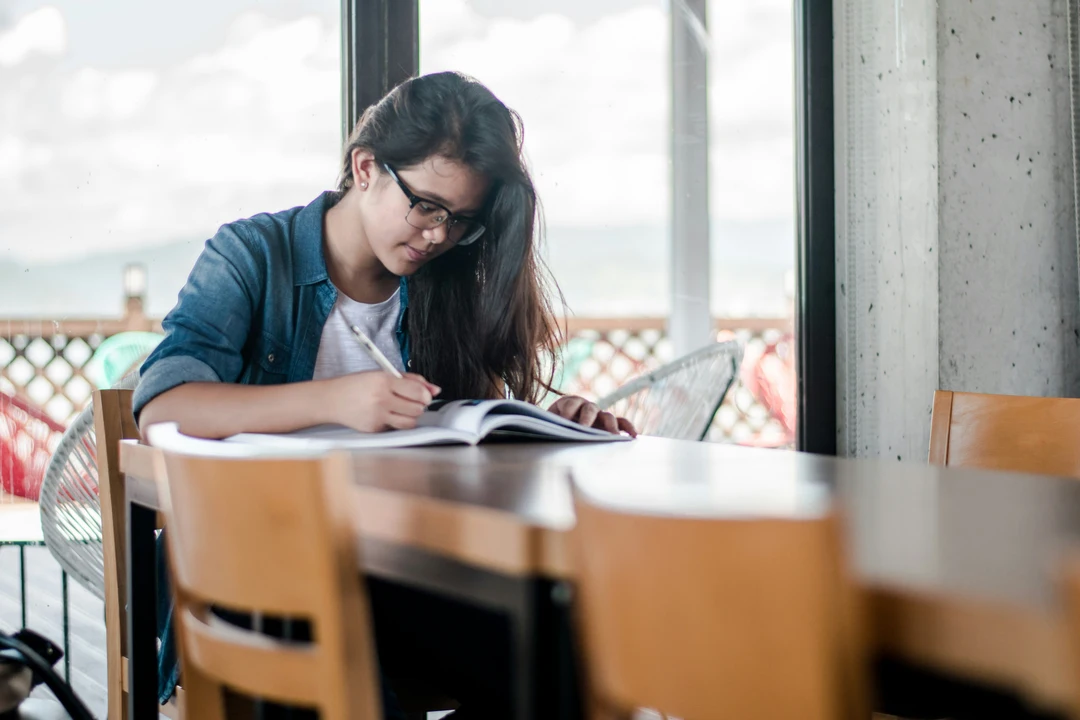

Whether you are gearing up for your GCSE coursework submissions or looking to brush up on your A-level writing skills, we have the perfect essay-writing guide for you. 💯

Staring at a blank page before writing an essay can feel a little daunting . Where do you start? What should your introduction say? And how should you structure your arguments? They are all fair questions and we have the answers! Take the stress out of essay writing with this step-by-step guide – you’ll be typing away in no time. 👩💻

What is an essay?

Generally speaking, an essay designates a literary work in which the author defends a point of view or a personal conviction, using logical arguments and literary devices in order to inform and convince the reader.

So – although essays can be broadly split into four categories: argumentative, expository, narrative, and descriptive – an essay can simply be described as a focused piece of writing designed to inform or persuade. 🤔

The purpose of an essay is to present a coherent argument in response to a stimulus or question and to persuade the reader that your position is credible, believable and reasonable. 👌

So, a ‘good’ essay relies on a confident writing style – it’s clear, well-substantiated, focussed, explanatory and descriptive . The structure follows a logical progression and above all, the body of the essay clearly correlates to the tile – answering the question where one has been posed.

But, how do you go about making sure that you tick all these boxes and keep within a specified word count? Read on for the answer as well as an example essay structure to follow and a handy step-by-step guide to writing the perfect essay – hooray. 🙌

Sometimes, it is helpful to think about your essay like it is a well-balanced argument or a speech – it needs to have a logical structure, with all your points coming together to answer the question in a coherent manner. ⚖️

Of course, essays can vary significantly in length but besides that, they all follow a fairly strict pattern or structure made up of three sections. Lean into this predictability because it will keep you on track and help you make your point clearly. Let’s take a look at the typical essay structure:

#1 Introduction

Start your introduction with the central claim of your essay. Let the reader know exactly what you intend to say with this essay. Communicate what you’re going to argue, and in what order. The final part of your introduction should also say what conclusions you’re going to draw – it sounds counter-intuitive but it’s not – more on that below. 1️⃣

Make your point, evidence it and explain it. This part of the essay – generally made up of three or more paragraphs depending on the length of your essay – is where you present your argument. The first sentence of each paragraph – much like an introduction to an essay – should summarise what your paragraph intends to explain in more detail. 2️⃣

#3 Conclusion

This is where you affirm your argument – remind the reader what you just proved in your essay and how you did it. This section will sound quite similar to your introduction but – having written the essay – you’ll be summarising rather than setting out your stall. 3️⃣

No essay is the same but your approach to writing them can be. As well as some best practice tips, we have gathered our favourite advice from expert essay-writers and compiled the following 7-step guide to writing a good essay every time. 👍

#1 Make sure you understand the question

#2 complete background reading.

#3 Make a detailed plan

#4 Write your opening sentences

#5 flesh out your essay in a rough draft, #6 evidence your opinion, #7 final proofread and edit.

Now that you have familiarised yourself with the 7 steps standing between you and the perfect essay, let’s take a closer look at each of those stages so that you can get on with crafting your written arguments with confidence .

This is the most crucial stage in essay writing – r ead the essay prompt carefully and understand the question. Highlight the keywords – like ‘compare,’ ‘contrast’ ‘discuss,’ ‘explain’ or ‘evaluate’ – and let it sink in before your mind starts racing . There is nothing worse than writing 500 words before realising you have entirely missed the brief . 🧐

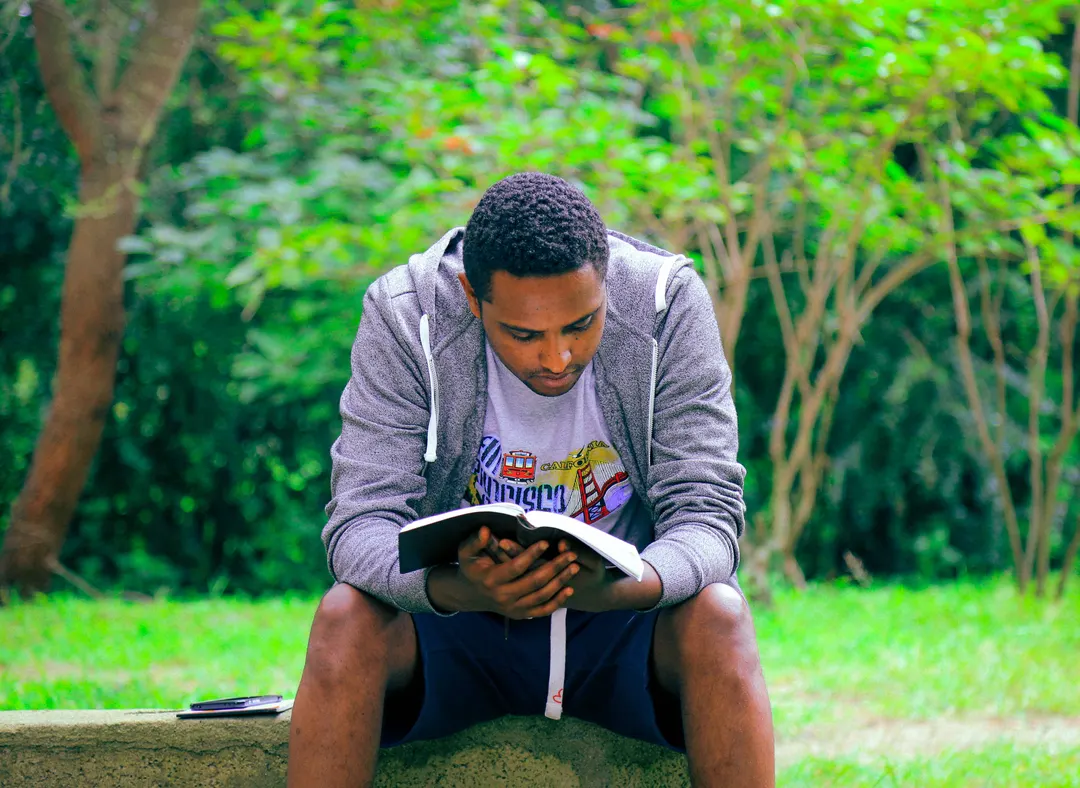

Unless you are writing under exam conditions , you will most likely have been working towards this essay for some time, by doing thorough background reading. Re-read relevant chapters and sections, highlight pertinent material and maybe even stray outside the designated reading list, this shows genuine interest and extended knowledge. 📚

#3 Make a detailed plan

Following the handy structure we shared with you above, now is the time to create the ‘skeleton structure’ or essay plan. Working from your essay title, plot out what you want your paragraphs to cover and how that information is going to flow. You don’t need to start writing any full sentences yet but it might be useful to think about the various quotes you plan to use to substantiate each section. 📝

Having mapped out the overall trajectory of your essay, you can start to drill down into the detail. First, write the opening sentence for each of the paragraphs in the body section of your essay. Remember – each paragraph is like a mini-essay – the opening sentence should summarise what the paragraph will then go on to explain in more detail. 🖊️

Next, it's time to write the bulk of your words and flesh out your arguments. Follow the ‘point, evidence, explain’ method. The opening sentences – already written – should introduce your ‘points’, so now you need to ‘evidence’ them with corroborating research and ‘explain’ how the evidence you’ve presented proves the point you’re trying to make. ✍️

With a rough draft in front of you, you can take a moment to read what you have written so far. Are there any sections that require further substantiation? Have you managed to include the most relevant material you originally highlighted in your background reading? Now is the time to make sure you have evidenced all your opinions and claims with the strongest quotes, citations and material. 📗

This is your final chance to re-read your essay and go over it with a fine-toothed comb before pressing ‘submit’. We highly recommend leaving a day or two between finishing your essay and the final proofread if possible – you’ll be amazed at the difference this makes, allowing you to return with a fresh pair of eyes and a more discerning judgment. 🤓

If you are looking for advice and support with your own essay-writing adventures, why not t ry a free trial lesson with GoStudent? Our tutors are experts at boosting academic success and having fun along the way. Get in touch and see how it can work for you today. 🎒

Popular posts

- By Guy Doza

- By Akshat Biyani

- By Joseph McCrossan

- In LEARNING TRENDS

4 Surprising Disadvantages of Homeschooling

- By Andrea Butler

The 12 Best GCSE Revision Apps to Supercharge Your Revision

More great reads:.

Benefits of Reading: Positive Impacts for All Ages Everyday

- May 26, 2023

15 of the Best Children's Books That Every Young Person Should Read

- By Sharlene Matharu

- March 2, 2023

Ultimate School Library Tips and Hacks

- By Natalie Lever

- March 1, 2023

Book a free trial session

Sign up for your free tutoring lesson..

What Is The Good Life & How To Attain It

Yet with more than 8 billion people on this planet, there are probably just as many opinions about what the good life entails.

Positive psychology began as an inquiry into the good life to establish a science of human flourishing and improve our understanding of what makes life worth living (Lopez & Snyder, 2011).

We will begin this article by exploring definitions of the good life, before presenting a brief history of philosophical theories of the good life. Then we’ll introduce a few psychological theories of the good life and methods for assessing the quality of life, before discussing how you can apply these theories to live a more fulfilling life.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Happiness & Subjective Wellbeing Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify sources of authentic happiness and strategies to boost wellbeing.

This Article Contains:

What is the good life, what is the good life in philosophy, theories about the good life, assessing your quality of life, how to live the good life, positivepsychology.com resources, a take-home message.

The word ‘good’ has a very different meaning for very many people; however, there are some aspects of ‘the good life’ that most people can probably agree on such as:

- Material comfort

- Engagement in meaningful activities/work,

- Loving relationships (with partners, family, and friends)

- Belonging to a community.

Together, a sense of fulfillment in these and other life domains will lead most people to flourish and feel that life is worth living (Vanderweele, 2017).

However, the question ‘what is the good life?’ has been asked in many fields throughout history, beginning with philosophy. Let’s look at where it all began.

According to Socrates

Interestingly enough, the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates never wrote anything down. His student Plato reported his speeches in published dialogues that demonstrate the Socratic method. Key to Socrates’ definition of the good life was that “the unexamined life is not worth living” (Ap 38a cited in West, 1979, p. 25).

Socrates argued that a person who lives a routine, mundane life of going to work and enjoying their leisure without reflecting on their values or life purpose had a life that wasn’t worth living.

Download 3 Free Happiness Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to discover authentic happiness and cultivate subjective well-being.

Download 3 Free Happiness Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

According to Plato

Plato’s view of the good life was presented in The Republic (Plato, 380-375 BCE/2007) and supported the views of his teacher, Socrates. The Republic examines virtue and the role of philosophy, community, and the state in creating the conditions needed to live well.

In this dialogue, Socrates is asked why a person ought to be virtuous to live a good life, rather than merely appear to be virtuous by cultivating a good reputation. Socrates answers that the good life doesn’t refer to a person’s reputation but to the state of a person’s soul.

The role of philosophy is essential because philosophers are educated in using reason to subdue their animal passions. This creates noble individuals who contribute to a well-ordered and humane society. A person who is unable to regulate their behavior will be unstable and create suffering for themselves and others, leading to a disordered society.

Therefore, educated reason is crucial for cultivating virtuous conduct to minimize human suffering, both individually and socially. For Socrates and Plato, rational reflection on the consequences of our actions is key to establishing virtuous conduct and living the good life, both inwardly and outwardly.

For a fuller account check out the Wireless Philosophy video by Dr. Chris Surprenant below.

According to Aristotle

For Plato’s student Aristotle, the acquisition of both intellectual and character virtues created the highest good, which he identified with the Greek word eudaimonia , often translated as happiness (Aristotle, 350 BCE/2004).

Aristotle believed a person achieves eudaimonia when they possess all the virtues; however, acquiring them requires more than studying or training. External conditions are needed that are beyond the control of individuals, especially a form of state governance that permits people to live well.

It was Aristotle’s option that state legislators (part of Greek governance) should create laws that aim to improve individual character, which develops along a spectrum from vicious to virtuous. To cultivate virtue, reason is required to discern the difference between good and bad behavior.

For more on Aristotle’s version of the good life, click out the Wireless Philosophy video by Dr. Chris Surprenant below.

According to Kant

Immanuel Kant was a Prussian-born German philosopher active during the Enlightenment period of the late 18th century (Scruton, 2001). He is best known for his seminal contributions to ethics, moral philosophy, and metaphysics.

For Kant, a capacity for virtue is unique to human beings, because the ability to resist bodily desires requires the exercise of reason. Kant claims that human reason makes us worthy of happiness by helping us become virtuous (Kant, 1785/2012).

Kant’s argument describes the relationship between morality, reason, and freedom. One necessary condition of moral action is free choice.

An individual’s action is freely chosen if their reasoning determines the right course of action. Conduct is not freely chosen if it is driven by bodily desires like hunger, lust, or fear, or behavioral coercion that applies rewards and punishments to steer human actions.

For Kant, individuals should act only if they can justify their action as universally applicable, which he termed the categorical imperative (Kant, 1785/2012). He argued that all our behavioral choices can be tested against the categorical imperative to see if they are consistent with the demands of morality. If they fail, they should be discarded.

A virtuous person must exercise reason to identify which principles are consistent with the categorical imperative and act accordingly. However, Kant claimed that reason can only develop through education in a civilized society that has secured the external conditions required for an individual to become virtuous.

For example, an individual who lives in fear of punishment or death lacks the freedom required to live virtuously, therefore authoritarian societies can never produce virtuous individuals. Poverty also erodes an individual’s freedom as they will be preoccupied with securing the means of survival.

For a deeper examination of these ideas view the Wireless Philosophy video by Dr. Chris Surprenant below.

According to Dr. Seligman

Dr. Martin Seligman is widely regarded as one of the founding fathers of positive psychology. For Seligman, the good life entails using our character strengths to engage in activities we find intrinsically fulfilling, during work and play and in our relationships.

For Seligman, ‘the good life’ has three strands,

- Positive emotions

- Eudaimonia and flow

Dr. Seligman’s work with Christopher Peterson (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) helped to develop the VIA system of signature strengths . When we invest our strengths in the activities of daily living, we can develop the virtues required to live ‘the good life’; a life characterized by positive emotional states, flow, and meaning.

Here is a video to learn more from Dr. Seligman about how cultivating your unique strengths is essential for living the good life.

Theories about what constitutes the good life and how to live it abound. This section will look at some of the most recent psychological theories about what contributes to the good life.

Set-Point Theory

Set-point theory argues that while people have fluctuating responses to significant life events like getting married, buying a new home, losing a loved one, or developing a chronic illness, we generally return to our inner ‘set point’ of subjective wellbeing (SWB) after a few years (Diener et al., 1999). This is largely inherited and tied in with personality type.

In terms of the Big Five personality traits , those predisposed to neuroticism will tend more toward pessimism and negative perceptions of events, while those who are more extroverted and open to experience will tend more toward optimism.

According to set-point theory, the efforts we make to achieve our life goals will have little lasting effect on our overall SWB given we each have our own ‘happiness set point’ (Lyubomirsky, 2007).

Furthermore, set point theory suggests that there’s little we can do for people who have been through a difficult time like losing their spouse or losing their job because they will eventually adapt and return to their previous set point.

This implies that helping professionals who believe they can improve people’s SWB in the longer term may be misguided. Or does it?

Other research provides evidence that achieving life goals can have a direct effect on a person’s overall contentment (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2021). Specifically, pursuing non-competitive goals such as making a family, building friendships, helping others in our community, and engaging in social justice activities improve our sense of wellbeing.

On the other hand, pursuing competitive life goals like building a career and monetary wealth exclusively undermines SWB.

For set-point theory, the good life depends more on innate personality traits than education. For a surprising account of this, using a practical example, view the video below.

Life-Satisfaction Theory

Typically, life satisfaction refers to a global evaluation of what makes life worth living rather than focusing on success in one area of life like a career or intimate relationship, or the fleeting sense of pleasure we often call happiness (Suikkanen, 2011).

However, there tend to be two dominant theories of what causes life satisfaction: bottom-up theories and top-down theories.

Bottom-up theories propose that life satisfaction is a consequence of a rounded overall sense of success in highly valued life domains . Valued life domains differ from person to person. For a professional athlete, sporting achievement may be highly valued, while for a committed parent having a good partnership and stable family life will be super important (Suikkanen, 2011).

Of course, these are not mutually exclusive. For most people, multiple life domains matter equally. However, if we are satisfied with the areas that we value, a global sense of life satisfaction results (Suikkanen, 2011).

Top-down theories propose that our happiness set-point has a greater influence on life satisfaction than goal achievement. In other words, personality traits like optimism have a positive impact on a person’s satisfaction with life regardless of external circumstances, whereas neuroticism undermines contentment.

The debate continues, and life satisfaction is likely influenced by a combination of nature and nurture as with other areas of psychology (Suikkanen, 2011). You can read an extended discussion of the evidence in our related article on life satisfaction .

So, while life satisfaction is associated with living a good life, it’s not necessarily related to education, the exercise of reason, or the cultivation of virtues as proposed by the philosophers mentioned above. For example, a successful financial criminal may be highly satisfied with life but would be deemed a corrupt human being by such lofty philosophical standards.

Hedonic treadmill

Meanwhile, the concept of the hedonic treadmill proposes that no matter what happens, good or bad, a person will eventually return to their baseline emotional state. For example, if someone gets married, moves to a new home, is promoted, loses a job, or is seriously injured in an accident, eventually, they will default to their innate set point (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012).

This has also been termed hedonic adaptation theory (Diener et al., 2006). It means that no matter how hard we chase happiness or try to avoid suffering, ultimately, our innate tendencies toward pessimism or optimism return us to our baseline level, either dysphoria or contentment (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005).

If you tend to see the glass as half empty rather than half full, don’t be discouraged, because recent research by Sheldon and Lyubomirsky (2021) acknowledges that while we each have a happiness set point, we can also cultivate greater happiness. We’ve offered some tips in the ‘how to’ section below.

Nevertheless, assessing the quality of life has led to an abundance of international research using quality of life indicators (QoLs) in a variety of scales and questionnaires (Zheng et al., 2021).

Gill and Feinstein identified at least 150 QoL assessment instruments back in the mid-1990s (Gill & Feinstein, 1994). Since then, scales have been refined to measure the quality of life in relation to specific health conditions, life events, and demographic factors like age, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (Zheng et al., 2021).

Our article Quality of Life Questionnaires and Assessments explains this in more detail and guides you on how to choose the best instrument for your clients.

Meanwhile, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ( OECD ) has developed the Better Life Index to measure how people from different demographics define a high quality of life. You can find out more in the brief video below.

How can each of us live the good life today given our array of differences? Below are five steps you can take to clarify what the good life means to you, and how you can apply your strengths to set goals that will lead to greater fulfillment.

1. Clarify your values

Clarifying what is important to you helps invest your life with meaning. Download our values clarification worksheet to get started.

2. Identify valued life domains

Investing in activities in valued life domains is intrinsically rewarding. Download our valued life domains worksheet to find out more.

3. Invest in your strengths

You can find out your character strengths by taking the free survey here . Playing to your strengths helps you overcome challenges and achieve your goals leading to greater life satisfaction. Read our article about how to apply strengths-based approaches to living well.

4. Set valued goals

Finally, we all benefit when we set goals and make practical plans to achieve them. Try our setting valued goals worksheet for guidance.

5. Ensure high-quality relationships

Healthy relationships with partners, family, friends, and colleagues are essential for living the good life and achieving your goals. To assess the quality of your relationships, take a look at our article on healthy relationships with free worksheets.

You can also look at our healthy boundaries article with more free resources. Healthy boundaries support you in living the good life in all life domains, while poor boundaries will leave you feeling unfulfilled.

17 Exercises To Increase Happiness and Wellbeing

Add these 17 Happiness & Subjective Well-Being Exercises [PDF] to your toolkit and help others experience greater purpose, meaning, and positive emotions.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

We have an excellent selection of resources you might find useful for living the good life.

First, take a look at our Meaning & Valued Living Masterclass for positive psychology practitioners. This online masterclass follows a practical process of identifying values, investing in strengths and then applying them to living a more fulfilled life.

In addition, we have two related articles for you to enjoy while exploring the role of meaning in the good life:

- Realizing Your Meaning: 5 Ways to Live a Meaningful Life

- 15 Ways to Find Your Purpose of Life & Realize Your Meaning

Next, we have an article explaining the role of human flourishing in living the good life.

- What Is Flourishing in Positive Psychology? (+8 Tips & PDF)

Finally, we have an article on how to apply values-driven goal-setting to living the good life.

- How to Set and Achieve Life Goals The Right Way

We also have worksheets you may find useful aids to living the good life:

Our How Joined Up is Your Life? worksheet can help your client identify their interests and passions, assess how authentically they are living their life, and identify any values that remain unfulfilled.

This Writing Your Own Mission Statement worksheet can help clients capture what they stand for, their aims, and objectives. Having a personal mission statement can be useful to return to periodically to assess our alignment with our values and goals.

Finally, this How to Get What You Deserve in Life worksheet can help clients identify what they want as well as justify why they deserve a good life.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others develop strategies to boost their wellbeing, this collection contains 17 validated happiness and wellbeing exercises . Use them to help others pursue authentic happiness and work toward a life filled with purpose and meaning.

We all want to live the good life, whatever that means to us individually. The concept has preoccupied human beings for millennia.

If you currently struggle, which we all do at different times, we hope you’ll consider trying some of the science-based strategies suggested above to steer your way through.

All the evidence we have shared above shows that you can improve your life satisfaction and subjective wellbeing by living in line with your values. But you have to be clear about what’s important to you.

Values-based living invests your life with more meaning and purpose and is key to living the good life.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Happiness Exercises for free .

- Aristotle. (2004). Nicomachean ethics (Tredennick, H & Thomson, J.A.K., Trans.). Penguin. Original work published 350 BCE.

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollon, C. N. (2006). Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist , 61(4), 305–314.

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin , 125(2), 276–302.

- Gill, T. M., & Feinstein, A. R. (1994). A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements . Jama, 272(8), 619-626.

- Kant, I. (2012). Groundwork of the metaphysics of morals . Cambridge University Press. Original work published 1785.

- Lopez, S. L. & Snyder, C. R. (2011). The Oxford handbook of positive psychology . Oxford University Press.

- Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology , 9, 111–131.

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2007). The how of happiness: A scientific approach to getting the life you want . Penguin.

- Plato. (2007). The Republic (D. Lee, Trans.; 2nd ed.). Penguin. Original work published 380-375 BCE.

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press.

- Scruton, R. (2001). Kant: A very short introduction . Oxford.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2012). The challenge of staying happier: Testing the hedonic adaptation prevention model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 38(5), 670–680.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2021). Revisiting the sustainable happiness model and pie chart: Can happiness be successfully pursued? The Journal of Positive Psychology , 16(2), 145–154.

- Suikkanen, J. (2011). An improved whole life satisfaction theory of happiness. International Journal of Wellbeing , 1(1), 149-166

- Vanderweele, T. J. (2017). On the promotion of human flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 114(31), 8148–8156.

- West, T. G. (1979). Plato’s “Apology of Socrates”: an interpretation, with a new translation . Cornell University Press.

- Zheng, S., He, A., Yu, Y., Jiang, L., Liang, J. & Wang, P. (2021). Research trends and hotspots of health-related quality of life: a bibliometric analysis from 2000 to 2019. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 19 , 130.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

For me a happy life is having the necessary things to have a good life in the physical aspect, economic aspect ,social aspect, achievement and also family, love and health . The luxuries are also good but they are extra things in life. The most important thing in life is love and peace.

This article made my day. Thank you for putting it together.

I lost approximately 14,000 dollars because of a bank fraud. This money is a product of my hardwork as a nurse and I have been saving it so I have a money when I travel back to be with partner. And the bank refused to refund my money. This incidence has made me feel devastated about life. It affected me emotionally and mentally. But I tried to contain this emotion for a few months and avoided to work and avoided my friends. But I am lucky that my parents, my sisters and especially my partner have been very supportive and understanding to me. They showed me the love and care I needed especially those tough times. Only a few days ago that I realised I should start to help myself and this is why I started to listen to a different talks and read articles that will help me to stay positive in life. Having this article read, it reminded me that I should be grateful that I am surrounded with great people. So thank you for sharing this article and making it accessible to everyone.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Embracing JOMO: Finding Joy in Missing Out

We’ve probably all heard of FOMO, or ‘the fear of missing out’. FOMO is the currency of social media platforms, eager to encourage us to [...]

The True Meaning of Hedonism: A Philosophical Perspective

“If it feels good, do it, you only live once”. Hedonists are always up for a good time and believe the pursuit of pleasure and [...]

Happiness Economics: Can Money Buy Happiness?

Do you ever daydream about winning the lottery? After all, it only costs a small amount, a slight risk, with the possibility of a substantial [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

3 Happiness Exercises Pack [PDF]

- Academic Skills

- Reading, writing and referencing

Writing a great essay

This resource covers key considerations when writing an essay.

While reading a student’s essay, markers will ask themselves questions such as:

- Does this essay directly address the set task?

- Does it present a strong, supported position?

- Does it use relevant sources appropriately?

- Is the expression clear, and the style appropriate?

- Is the essay organised coherently? Is there a clear introduction, body and conclusion?

You can use these questions to reflect on your own writing. Here are six top tips to help you address these criteria.

1. Analyse the question

Student essays are responses to specific questions. As an essay must address the question directly, your first step should be to analyse the question. Make sure you know exactly what is being asked of you.

Generally, essay questions contain three component parts:

- Content terms: Key concepts that are specific to the task

- Limiting terms: The scope that the topic focuses on

- Directive terms: What you need to do in relation to the content, e.g. discuss, analyse, define, compare, evaluate.

Look at the following essay question:

Discuss the importance of light in Gothic architecture.

- Content terms: Gothic architecture

- Limiting terms: the importance of light. If you discussed some other feature of Gothic architecture, for example spires or arches, you would be deviating from what is required. This essay question is limited to a discussion of light. Likewise, it asks you to write about the importance of light – not, for example, to discuss how light enters Gothic churches.

- Directive term: discuss. This term asks you to take a broad approach to the variety of ways in which light may be important for Gothic architecture. You should introduce and consider different ideas and opinions that you have met in academic literature on this topic, citing them appropriately .

For a more complex question, you can highlight the key words and break it down into a series of sub-questions to make sure you answer all parts of the task. Consider the following question (from Arts):

To what extent can the American Revolution be understood as a revolution ‘from below’? Why did working people become involved and with what aims in mind?

The key words here are American Revolution and revolution ‘from below’. This is a view that you would need to respond to in this essay. This response must focus on the aims and motivations of working people in the revolution, as stated in the second question.

2. Define your argument

As you plan and prepare to write the essay, you must consider what your argument is going to be. This means taking an informed position or point of view on the topic presented in the question, then defining and presenting a specific argument.

Consider these two argument statements:

The architectural use of light in Gothic cathedrals physically embodied the significance of light in medieval theology.

In the Gothic cathedral of Cologne, light served to accentuate the authority and ritual centrality of the priest.

Statements like these define an essay’s argument. They give coherence by providing an overarching theme and position towards which the entire essay is directed.

3. Use evidence, reasoning and scholarship

To convince your audience of your argument, you must use evidence and reasoning, which involves referring to and evaluating relevant scholarship.

- Evidence provides concrete information to support your claim. It typically consists of specific examples, facts, quotations, statistics and illustrations.

- Reasoning connects the evidence to your argument. Rather than citing evidence like a shopping list, you need to evaluate the evidence and show how it supports your argument.

- Scholarship is used to show how your argument relates to what has been written on the topic (citing specific works). Scholarship can be used as part of your evidence and reasoning to support your argument.

4. Organise a coherent essay

An essay has three basic components - introduction, body and conclusion.

The purpose of an introduction is to introduce your essay. It typically presents information in the following order:

- A general statement about the topic that provides context for your argument

- A thesis statement showing your argument. You can use explicit lead-ins, such as ‘This essay argues that...’

- A ‘road map’ of the essay, telling the reader how it is going to present and develop your argument.

Example introduction

"To what extent can the American Revolution be understood as a revolution ‘from below’? Why did working people become involved and with what aims in mind?"

Introduction*

Historians generally concentrate on the twenty-year period between 1763 and 1783 as the period which constitutes the American Revolution [This sentence sets the general context of the period] . However, when considering the involvement of working people, or people from below, in the revolution it is important to make a distinction between the pre-revolutionary period 1763-1774 and the revolutionary period 1774-1788, marked by the establishment of the continental Congress(1) [This sentence defines the key term from below and gives more context to the argument that follows] . This paper will argue that the nature and aims of the actions of working people are difficult to assess as it changed according to each phase [This is the thesis statement] . The pre-revolutionary period was characterised by opposition to Britain’s authority. During this period the aims and actions of the working people were more conservative as they responded to grievances related to taxes and scarce land, issues which directly affected them. However, examination of activities such as the organisation of crowd action and town meetings, pamphlet writing, formal communications to Britain of American grievances and physical action in the streets, demonstrates that their aims and actions became more revolutionary after 1775 [These sentences give the ‘road map’ or overview of the content of the essay] .

The body of the essay develops and elaborates your argument. It does this by presenting a reasoned case supported by evidence from relevant scholarship. Its shape corresponds to the overview that you provided in your introduction.

The body of your essay should be written in paragraphs. Each body paragraph should develop one main idea that supports your argument. To learn how to structure a paragraph, look at the page developing clarity and focus in academic writing .

Your conclusion should not offer any new material. Your evidence and argumentation should have been made clear to the reader in the body of the essay.

Use the conclusion to briefly restate the main argumentative position and provide a short summary of the themes discussed. In addition, also consider telling your reader:

- What the significance of your findings, or the implications of your conclusion, might be

- Whether there are other factors which need to be looked at, but which were outside the scope of the essay

- How your topic links to the wider context (‘bigger picture’) in your discipline.

Do not simply repeat yourself in this section. A conclusion which merely summarises is repetitive and reduces the impact of your paper.

Example conclusion

Conclusion*.

Although, to a large extent, the working class were mainly those in the forefront of crowd action and they also led the revolts against wealthy plantation farmers, the American Revolution was not a class struggle [This is a statement of the concluding position of the essay]. Working people participated because the issues directly affected them – the threat posed by powerful landowners and the tyranny Britain represented. Whereas the aims and actions of the working classes were more concerned with resistance to British rule during the pre-revolutionary period, they became more revolutionary in nature after 1775 when the tension with Britain escalated [These sentences restate the key argument]. With this shift, a change in ideas occurred. In terms of considering the Revolution as a whole range of activities such as organising riots, communicating to Britain, attendance at town hall meetings and pamphlet writing, a difficulty emerges in that all classes were involved. Therefore, it is impossible to assess the extent to which a single group such as working people contributed to the American Revolution [These sentences give final thoughts on the topic].

5. Write clearly

An essay that makes good, evidence-supported points will only receive a high grade if it is written clearly. Clarity is produced through careful revision and editing, which can turn a good essay into an excellent one.

When you edit your essay, try to view it with fresh eyes – almost as if someone else had written it.

Ask yourself the following questions:

Overall structure

- Have you clearly stated your argument in your introduction?

- Does the actual structure correspond to the ‘road map’ set out in your introduction?

- Have you clearly indicated how your main points support your argument?

- Have you clearly signposted the transitions between each of your main points for your reader?

- Does each paragraph introduce one main idea?

- Does every sentence in the paragraph support that main idea?

- Does each paragraph display relevant evidence and reasoning?

- Does each paragraph logically follow on from the one before it?

- Is each sentence grammatically complete?

- Is the spelling correct?

- Is the link between sentences clear to your readers?

- Have you avoided redundancy and repetition?

See more about editing on our editing your writing page.

6. Cite sources and evidence

Finally, check your citations to make sure that they are accurate and complete. Some faculties require you to use a specific citation style (e.g. APA) while others may allow you to choose a preferred one. Whatever style you use, you must follow its guidelines correctly and consistently. You can use Recite, the University of Melbourne style guide, to check your citations.

Further resources

- Germov, J. (2011). Get great marks for your essays, reports and presentations (3rd ed.). NSW: Allen and Unwin.

- Using English for Academic Purposes: A guide for students in Higher Education [online]. Retrieved January 2020 from http://www.uefap.com

- Williams, J.M. & Colomb, G. G. (2010) Style: Lessons in clarity and grace. 10th ed. New York: Longman.

* Example introduction and conclusion adapted from a student paper.

Looking for one-on-one advice?

Get tailored advice from an Academic Skills Adviser by booking an Individual appointment, or get quick feedback from one of our Academic Writing Mentors via email through our Writing advice service.

Go to Student appointments

How to Write the Perfect Essay

06 Feb, 2024 | Blog Articles , English Language Articles , Get the Edge , Humanities Articles , Writing Articles

You can keep adding to this plan, crossing bits out and linking the different bubbles when you spot connections between them. Even though you won’t have time to make a detailed plan under exam conditions, it can be helpful to draft a brief one, including a few key words, so that you don’t panic and go off topic when writing your essay.

If you don’t like the mind map format, there are plenty of others to choose from: you could make a table, a flowchart, or simply a list of bullet points.

Discover More

Thanks for signing up, step 2: have a clear structure.

Think about this while you’re planning: your essay is like an argument or a speech. It needs to have a logical structure, with all your points coming together to answer the question.

Start with the basics! It’s best to choose a few major points which will become your main paragraphs. Three main paragraphs is a good number for an exam essay, since you’ll be under time pressure.

If you agree with the question overall, it can be helpful to organise your points in the following pattern:

- YES (agreement with the question)

- AND (another YES point)

- BUT (disagreement or complication)

If you disagree with the question overall, try:

- AND (another BUT point)

For example, you could structure the Of Mice and Men sample question, “To what extent is Curley’s wife portrayed as a victim in Of Mice and Men ?”, as follows:

- YES (descriptions of her appearance)

- AND (other people’s attitudes towards her)

- BUT (her position as the only woman on the ranch gives her power as she uses her femininity to her advantage)

If you wanted to write a longer essay, you could include additional paragraphs under the YES/AND categories, perhaps discussing the ways in which Curley’s wife reveals her vulnerability and insecurities, and shares her dreams with the other characters. Alternatively, you could also lengthen your essay by including another BUT paragraph about her cruel and manipulative streak.

Of course, this is not necessarily the only right way to answer this essay question – as long as you back up your points with evidence from the text, you can take any standpoint that makes sense.

Step 3: Back up your points with well-analysed quotations

You wouldn’t write a scientific report without including evidence to support your findings, so why should it be any different with an essay? Even though you aren’t strictly required to substantiate every single point you make with a quotation, there’s no harm in trying.

A close reading of your quotations can enrich your appreciation of the question and will be sure to impress examiners. When selecting the best quotations to use in your essay, keep an eye out for specific literary techniques. For example, you could highlight Curley’s wife’s use of a rhetorical question when she says, a”n’ what am I doin’? Standin’ here talking to a bunch of bindle stiffs.” This might look like:

The rhetorical question “an’ what am I doin’?” signifies that Curley’s wife is very insecure; she seems to be questioning her own life choices. Moreover, she does not expect anyone to respond to her question, highlighting her loneliness and isolation on the ranch.

Other literary techniques to look out for include:

- Tricolon – a group of three words or phrases placed close together for emphasis

- Tautology – using different words that mean the same thing: e.g. “frightening” and “terrifying”

- Parallelism – ABAB structure, often signifying movement from one concept to another

- Chiasmus – ABBA structure, drawing attention to a phrase

- Polysyndeton – many conjunctions in a sentence

- Asyndeton – lack of conjunctions, which can speed up the pace of a sentence

- Polyptoton – using the same word in different forms for emphasis: e.g. “done” and “doing”

- Alliteration – repetition of the same sound, including assonance (similar vowel sounds), plosive alliteration (“b”, “d” and “p” sounds) and sibilance (“s” sounds)

- Anaphora – repetition of words, often used to emphasise a particular point

Don’t worry if you can’t locate all of these literary devices in the work you’re analysing. You can also discuss more obvious techniques, like metaphor, simile and onomatopoeia. It’s not a problem if you can’t remember all the long names; it’s far more important to be able to confidently explain the effects of each technique and highlight its relevance to the question.

Step 4: Be creative and original throughout

Anyone can write an essay using the tips above, but the thing that really makes it “perfect” is your own unique take on the topic. If you’ve noticed something intriguing or unusual in your reading, point it out – if you find it interesting, chances are the examiner will too!

Creative writing and essay writing are more closely linked than you might imagine. Keep the idea that you’re writing a speech or argument in mind, and you’re guaranteed to grab your reader’s attention.

It’s important to set out your line of argument in your introduction, introducing your main points and the general direction your essay will take, but don’t forget to keep something back for the conclusion, too. Yes, you need to summarise your main points, but if you’re just repeating the things you said in your introduction, the body of the essay is rendered pointless.