Empathic joy and the empathy-altruism hypothesis

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Psychology, University of Kansas, Lawrence 66045-2160.

- PMID: 1941512

- DOI: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.3.413

Three experiments tested whether empathy evokes egoistic motivation to share vicariously in the victim's joy at improvement (the empathic-joy hypothesis) instead of altruistic motivation to increase the victim's welfare (the empathy-altruism hypothesis). In Experiment 1, Ss induced to feel either low or high empathy for a young woman in need were given a chance to help her. Some believed that if they helped they would receive feedback about her improvement; others did not. In Experiments 2 and 3, Ss induced to feel either low or high empathy were given a choice of getting update information about a needy person's condition. Before choosing, they were told the likelihood of the person's condition having improved--and of their experiencing empathic joy--was 20%, was 50%, or was 80%. Results of none of the experiments patterned as predicted by the empathic-joy hypothesis; instead, results of each were consistent with the empathy-altruism hypothesis.

Publication types

- Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S.

- Helping Behavior

What is empathic joy hypothesis?

The Empathy Joy hypothesis states that the reason for someone helping another in need are positive feelings associated with the altruistic behavior. Helping others is a reward in itself because it brings a person happiness and joy when they commit a helping behavior.

What is the empathy-altruism hypothesis quizlet?

According to the empathy-altruism hypothesis, when people feel empathy toward another person (they experience events and emotions the other person experiences), they attempt to help that person purely for altruistic reasons.

Are empathy and altruism related?

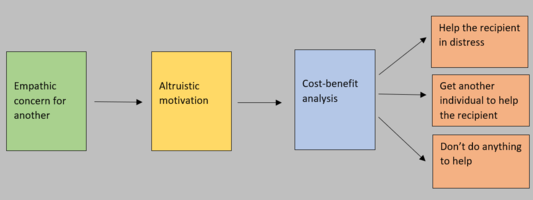

The connection between empathy and altruism is quite simple, according to the empathyaltruism hypothesisempathy is the emotion that triggers an altruistic motive (for a review, see Batson, 2011). … Both egoism and altruism have an ultimate goal of increasing someone’s welfare.

Is empathic emotion a source of altruistic motivation?

Is Empathic Emotion a Source of Altruistic Motivation? It has been suggested that empathy leads to altruistic rather than egoistic mo- tivation to help. … Evidence indicates that feeling empathy for the person in need is an important mo- tivator of helping (cf.

Who proposed empathy altruism hypothesis?

C. Daniel Batson Social psychologist C.Daniel Batson formulated the empathy-altruism hypothesis as a revision and extension of the ideas developed by these philosophers and psychologists.

Which of them is involved in the empathic joy hypothesis?

Kyle Smith, Jack Keating, and Ezra Stotland proposed the empathicjoy hypothesis, which claims that people feeling empathic concern help to get the pleasure of sharing vicariously in the joy that the target of empathy feels when his or her need is removed.

Why does self esteem decline during elementary school?

Self-esteem tends to decline during elementary school because children:can realistically compare their abilities to their peers. Children who believe they are powerless to affect their fate, and so give up, feeling that they should not try to succeed, have developed: learned helplessness.

Why is altruism a part of prosocial behavior quizlet?

Prosocial behavior is any action intended to help others. One motivation for prosocial behavior is altruism, or the desire to help others with no expectation of reward. In this lesson, we exploreprosocial behavior and the elements that social psychologists have identified as predicting it. You just studied 24 terms!

What does the social exchange theory suggest about the nature of altruism quizlet?

Second: According to the social exchange theory, people help others in situations in which they hope it would result in more rewards and fewer cost. … In empathy and altruism perspective, people are more likely to help others when they feel empathy toward that person regardless of what they have to gain.

Are Empaths selfish?

This does not mean that empaths are self-absorbed: it’s quite the opposite, actually. … If an empath needs to remove themselves to a quiet, still space in order to sort themselves out, they’re not being selfish, antisocial, or self-absorbed at all. They just need some stillness for the sake of balance and wellbeing.

Is empathy actually selfish?

Empathy is selfish It is, fundamentally, a selfish tool, as opposed to an altruistic set of impulses. Empathy contextualises oneself. It grounds a person in their surroundings, allowing them to ‘soak up’ the emotions of others, in order to heal themselves and intake new information.

What are altruistic motives?

Behavior is normally described as altruistic when it is motivated by a desire to benefit someone other than oneself for that person’s sake. The term is used as the contrary of self-interested or selfish or egoisticwords applied to behavior that is motivated solely by the desire to benefit oneself.

What is a cognitive explanation for altruism?

While the definition of altruism involves doing for others without reward, there may still be cognitive incentives that are not obvious. For example, we might help others to relieve our own distress or because being kind to others upholds our view of ourselves as kind people.

What do you think is the primary motive for helping behavior egoism or altruism?

Altruistic help Although many researchers believe that egoism is the only motivation for helping, others suggest that altruismhelping that has as its ultimate goal the improvement of another’s welfaremay also be a motivation for helping under the right circumstances.

What does research suggest about the connection between social class and altruism?

What does research suggest about the connection between social class and altruism? People who are not wealthy give a higher proportion of their incomes to charity.

What is the difference between altruism and empathy?

Definition. Altruism is the practice of selfless concern for others’ welfare while empathy is the ability to understand another person’s perspective and to share his or her feelings.

What is the meaning of altruistic behavior?

Altruism is when we act to promote someone else’s welfare, even at a risk or cost to ourselves. … Evolutionary scientists speculate that altruism has such deep roots in human nature because helping and cooperation promote the survival of our species.

What is the difference between altruism and compassion?

is that altruism is regard for others, both natural and moral without regard for oneself; devotion to the interests of others; brotherly kindness; selflessness; contrasted with egoism or selfishness while compassion is deep awareness of the suffering of another, coupled with the wish to relieve it.

Which of the following is a component of empathy quizlet?

What are the three distinct components of empathy? Emotional empathy, empathic accuracy, empathic concern.

What is the competitive altruism approach?

Competitive altruism is a hypothesis that attempts to explain the presence of cooperative behaviors (like helping and sharing) in organisms that don’t have a direct benefit to the organism performing the the behavior.

What are the objectives of social psychology?

The goal of social psychology is to understand cognition and behavior as they naturally occur in a social context, but the very act of observing people can influence and alter their behavior. For this reason, many social psychology experiments utilize deception to conceal or distort certain aspects of the study.

Why does self-esteem drop in adolescence?

Teenagers’ self-esteem is often affected by the physical and hormonal changes they experience, especially during puberty . Teens undergo major changes in their lives and their self-esteem can often become fragile. … Teens who set goals in their lives have higher self-esteem than those who do not.

How do elementary students build self-esteem?

- Five Strategies for Self Esteem.

- Use Positive Encouragement.

- Teach Boundaries and Lessons.

- Provide Feedback and Corrections.

- Correct Inaccurate Beliefs.

- Provide Consistent Love and Support.

How accepting yourself can improve your self-esteem?

Improving Your Self-Esteem

- Positive thinking. Try your best to avoid thinking negative thoughts about yourself. …

- Learn from mistakes. We all screw up a lot. …

- Be adventurous. Try new things, explore new hobbies, eat new foods! …

- Accept yourself. …

- Let your voice be heard. …

- Lend a hand. …

- Practice self-care.

What is altruism example?

Altruism refers to behavior that benefits another individual at a cost to oneself. For example, giving your lunch away is altruistic because it helps someone who is hungry, but at a cost of being hungry yourself. … Recent work suggests that humans behave altruistically because it is emotionally rewarding.

Why is altruism a part of prosocial behavior?

Prosocial behavior covers the broad range of actions intended to benefit one or more people other than oneselfactions such as helping, comforting, sharing, and cooperation. Altruism is motivation to increase another person’s welfare; it is contrasted to egoism, the motivation to increase one’s own welfare.

What is the social exchange theory quizlet?

Social Exchange theory looks at the economics of relationships; how people evaluate the costs and rewards of their current relationships. … -Negative costs are subtracted from positive rewards. -When rewards exceed costs, the overall evaluation is positive. -When costs exceed rewards, the overall evaluation is negative.

What does the social exchange theory suggest about the nature of altruism?

On one hand, social exchange theory posits that people will help only when the benefits of helping outweigh the costs. On the other hand, the empathy-altruism hypothesis says that people are altruistically motivated to help others for whom they feel empathy.

How do evolutionary psychologists use the concepts of kin selection and the reciprocity norm to explain human prosocial behavior?

Evolutionary psychologists used the kin-selection to explain how people would act altruistically first upon their own genetic relatives first before non-genetic relatives because of they share some of the same genes for greater survival for future generations.

How can a social trap create conflict?

In social traps, two or more individuals engage in mutually destructive behavior by rationally pursuing their own self-interests. People in conflict tend to expect the worst of each other, producing mirror-image perceptions that can become self-fulfilling prophecies.

Graduated from ENSAT (national agronomic school of Toulouse) in plant sciences in 2018, I pursued a CIFRE doctorate under contract with Sun’Agri and INRAE in Avignon between 2019 and 2022. My thesis aimed to study dynamic agrivoltaic systems, in my case in arboriculture. I love to write and share science related Stuff Here on my Website. I am currently continuing at Sun’Agri as an R&D engineer.

Related Posts

What is a good e e ratio, what is the pressure of nitrous oxide cylinder, what is electronic diplomacy, how is edna used for conservation, what does echocardiography measure, what are the units of e in e hv, how do you identify e faecalis, what does enterococcus faecalis look like, how do i know if i have eisenia fetida, what is meant by e glass fiber, what is e-glass and s-glass, what is e type fiberglass, what is e-glass fiber used for, what is e glass used for, what is e-glass fiber, is s-glass or e glass better, what is meant by e-government, what is a mayan e-group, is entamoeba hartmanni pathogenic, what is e hc .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Neuroscience of Happiness and Pleasure

The evolutionary imperatives of survival and procreation, and their associated rewards, are driving life as most animals know it. Perhaps uniquely, humans are able to consciously experience these pleasures and even contemplate the elusive prospect of happiness. The advanced human ability to consciously predict and anticipate the outcome of choices and actions confers on our species an evolutionary advantage, but this is a double-edged sword, as John Steinbeck pointed out as he wrote of “the tragic miracle of consciousness” and how our “species is not set, has not jelled, but is still in a state of becoming” ( Steinbeck and Ricketts 1941 ). While consciousness allows us to experience pleasures, desires, and perhaps even happiness, this is always accompanied by the certainty of the end.

Nevertheless, while life may ultimately meet a tragic end, one could argue that if this is as good as it gets, we might as well enjoy the ride and in particular to maximize happiness. Yet, it is also true that for many happiness is a rare companion due to the competing influences of anxiety and depression.

In order to help understand happiness and alleviate the suffering, neuroscientists and psychologists have started to investigate the brain states associated with happiness components and to consider the relation to well-being. While happiness is in principle difficult to define and study, psychologists have made substantial progress in mapping its empirical features, and neuroscientists have made comparable progress in investigating the functional neuroanatomy of pleasure, which contributes importantly to happiness and is central to our sense of well-being.

In this article we will try to map out some of the intricate links between pleasure and happiness. Our main contention is that a better understanding of the pleasures of the brain may offer a more general insight into happiness, into how brains work to produce it in daily life for the fortunate, how brains fail in the less fortunate, and hopefully into better ways to enhance the quality of life.

A SCIENCE OF HAPPINESS?

As shown by the other contributions to this volume, there are many possible definitions and approaches to investigating happiness. Many would agree that happiness has remained difficult to define and challenging to measure—partly due to its subjective nature. Is it possible to get a scientific handle on such a slippery concept? There are several aids to start us off.

Since Aristotle, happiness has been usefully thought of as consisting of at least two aspects: hedonia (pleasure) and eudaimonia (a life well lived). In contemporary psychology these aspects are usually referred to as pleasure and meaning, and positive psychologists have recently proposed to add a third distinct component of engagement related to feelings of commitment and participation in life ( Seligman et al. 2005 ).

Using these definitions, scientists have made substantial progress in defining and measuring happiness in the form of self-reports of subjective well-being, in identifying its distribution across people in the real world, and in identifying how well-being is influenced by various life factors that range from income to other people ( Kahneman 1999 ). This research shows that while there is clearly a sharp conceptual distinction between pleasure versus engagement-meaning components, hedonic and eudaimonic aspects empirically cohere together in happy people.

For example, in happiness surveys, over 80 percent of people rate their overall eudaimonic life satisfaction as “pretty to very happy,” and comparably, 80 percent also rate their current hedonic mood as positive (for example, positive 6–7 on a 10 point valence scale, where 5 is hedonically neutral) ( Kesebir and Diener 2008 ). A lucky few may even live consistently around a hedonic point of 8—although excessively higher hedonic scores may actually impede attainment of life success, as measured by wealth, education, or political participation ( Oishi et al. 2007 ).

While these surveys provide interesting indicators of mental well-being, they offer little evidence of the underlying neurobiology of happiness. That is the quest we set ourselves here. But to progress in this direction, it is first necessary to make a start using whatever evidence is both relevant to the topic of well-being and happiness, and in which neuroscience has relative strengths. Pleasure and its basis offers a window of opportunity.

In the following we will therefore focus on the substantial progress in understanding the psychology and neurobiology of sensory pleasure that has been made over the last decade ( Berridge and Kringelbach 2008 ; Kringelbach and Berridge 2010 ). These advances make the hedonic side of happiness most tractable to a scientific approach to the neural underpinnings of happiness. Supporting a hedonic approach, it has been suggested that the best measure of subjective well-being may be simply to ask people how they hedonically feel right now—again and again—so as to track their hedonic accumulation across daily life ( Kahneman 1999 ). Such repeated self-reports of hedonic states could also be used to identify more stable neurobiological hedonic brain traits that dispose particular individuals toward happiness. Further, a hedonic approach might even offer a toehold into identifying eudaimonic brain signatures of happiness, due to the empirical convergence between the two categories, even if pleasant mood is only half the happiness story ( Kringelbach and Berridge 2009 ).

It is important to note that our focus on the hedonia component of happiness should not be confused with hedonism, which is the pursuit of pleasure for pleasure’s own sake, and more akin to the addiction features we describe below. Also, to focus on hedonics does not deny that some ascetics may have found bliss through painful self-sacrifice, but simply reflects that positive hedonic tone is indispensable to most people seeking happiness.

A SCIENCE OF PLEASURE

The link between pleasure and happiness has a long history in psychology. For example, that link was stressed in the writings of Sigmund Freud when he posited that people “strive after happiness; they want to become happy and to remain so. This endeavor has two sides, a positive and a negative aim. It aims, on the one hand, at an absence of pain and displeasure, and, on the other, at the experiencing of strong feelings of pleasure” ( Freud and Riviere 1930 : 76). Emphasizing a positive balance of affect to be happy implies that studies of hedonic brain circuits can advance the neuroscience of both pleasure and happiness.

A related but slightly different view is that happiness depends most chiefly on eliminating negative “pain and displeasure” to free an individual to pursue engagement and meaning. Positive pleasure by this view is somewhat superfluous. This view may characterize the twentieth-century medical and clinical emphasis on alleviating negative psychopathology and strongly distressing emotions. It fits also with William James’s quip nearly a century ago that “happiness, I have lately discovered, is no positive feeling, but a negative condition of freedom from a number of restrictive sensations of which our organism usually seems the seat. When they are wiped out, the clearness and cleanness of the contrast is happiness. This is why anaesthetics make us so happy. But don’t you take to drink on that account” ( James 1920 : 158).

Focusing on eliminating negative distress seems to leave positive pleasure outside the boundary of happiness, perhaps as an extra bonus or even an irrelevancy for ordinary pursuit. In practice, many mixtures of positive affect and negative affect may occur in individuals and cultures may vary in the importance of positive versus negative affect for happiness. For example, positive emotions are linked most strongly to ratings of life satisfaction overall in nations that stress self-expression, but alleviation of negative emotions may become relatively more important in nations that value individualism ( Kuppens et al. 2008 ).

By either hedonic view, psychology seems to be moving away from the stoic notion that affect states such as pleasure are simply irrelevant to happiness. The growing evidence for the importance of affect in psychology and neuroscience shows that a scientific account will have to involve hedonic pleasures and/or displeasures. To move toward a neuroscience of happiness, a neurobiological understanding is required of how positive and negative affect are balanced in the brain.

Thus, pleasure is an important component of happiness, according to most modern viewpoints. Given the potential contributions of hedonics to happiness, we now survey developments in understanding the brain mechanisms of pleasure. The scientific study of pleasure and affect was foreshadowed by the pioneering ideas of Charles Darwin, who examined the evolution of emotions and affective expressions, and suggested that these are adaptive responses to environmental situations. In that vein, pleasure “liking” and displeasure reactions are prominent affective reactions in the behavior and brains of all mammals ( Steiner et al. 2001 ) and likely had important evolutionary functions ( Kringelbach 2009 ). Neural mechanisms for generating affective reactions are present and similar in most mammalian brains, and thus appear to have been selected for and conserved across species ( Kringelbach 2010 ). Indeed, both positive affect and negative affect are recognized today as having adaptive functions ( Nesse 2004 ), and positive affect in particular has consequences in daily life for planning and building cognitive and emotional resources ( Fredrickson et al. 2008 ).

Such functional perspectives are consistent with a thesis that is crucial to our aim of identifying the neurobiological bases of happiness: that affective reactions such as pleasure have objective features beyond their subjective ones. This idea is important, since progress in affective neuroscience has been made recently by identifying objective aspects of pleasure reactions and triangulating toward underlying brain substrates. This scientific strategy divides the concept of affect into two parts: the affective state , which has objective aspects in behavioral, physiological, and neural reactions; and conscious affective feelings , seen as the subjective experience of emotion ( Kringelbach 2004 ). Note that such a definition allows conscious feelings to play a central role in hedonic experiences, but holds that the affective essence of a pleasure reaction is more than a conscious feeling. That objective “something more” is especially tractable to neuroscience investigations that involve brain manipulations and can be studied regardless of the availability or accuracy of corresponding subjective reports.

The available evidence suggests that brain mechanisms involved in fundamental pleasures (food and sexual pleasures) overlap with those for higher-order pleasures (for example, monetary, artistic, musical, altruistic, and transcendent pleasures) ( Kringelbach 2010 ).

From sensory pleasures and drugs of abuse to monetary, aesthetic and musical delights, all pleasures seem to involve the same hedonic brain systems, even when linked to anticipation and memory. Pleasures important to happiness, such as socializing with friends, and related traits of positive hedonic mood are thus all likely to draw upon the same neurobiological roots that evolved for sensory pleasures. The neural overlap may offer a way to generalize from fundamental pleasures that are best understood and so infer larger hedonic brain principles likely to contribute to happiness.

We note the rewarding properties for all pleasures are likely to be generated by hedonic brain circuits that are distinct from the mediation of other features of the same events (for example, sensory, cognitive) ( Kringelbach 2005 ). Thus, pleasure is never merely a sensation or a thought, but is instead an additional hedonic gloss generated by the brain via dedicated systems ( Frijda 2010 ).

THE NEUROANATOMY OF PLEASURE

How does positive affect arise? Affective neuroscience research on sensory pleasure has revealed many networks of brain regions and neurotransmitters activated by pleasant events and states (see figures 1 and and2). 2 ). Identification of hedonic substrates has been advanced by recognizing that pleasure or “liking” is but one component in the larger composite psychological process of reward, which also involves “wanting” and “learning” components ( Smith et al. 2010 ). Each component also has conscious and nonconscious elements that can be studied in humans—and at least the latter can also be probed in other animals.

Reward and pleasure are multifaceted psychological concepts. Major processes within reward (first column) consist of motivation or wanting (white), learning (light gray), and—most relevant to happiness—pleasure liking or affect (gray). Each of these contains explicit (top three rows) and implicit (bottom three rows) psychological components (second column) that constantly interact and require careful scientific experimentation to tease apart. Explicit processes are consciously experienced (for example, explicit pleasure and happiness, desire, or expectation), whereas implicit psychological processes are potentially unconscious in the sense that they can operate at a level not always directly accessible to conscious experience (implicit incentive salience, habits and “liking” reactions), and must be further translated by other mechanisms into subjective feelings. Measurements or behavioral procedures that are especially sensitive markers of the each of the processes are listed (third column). Examples of some of the brain regions and neurotransmitters are listed (fourth column), as well as specific examples of measurements (fifth column), such as an example of how highest subjective life satisfaction does not lead to the highest salaries (top) ( Haisken-De New and Frick 2005 ). Another example shows the incentive-sensitization model of addiction and how “wanting” to take drugs may grow over time independently of “liking” and “learning” drug pleasure as an individual becomes an addict (bottom) ( Robinson and Berridge 1993 ).

The schematic figure shows the approximate sensorimotor, pleasure, and social brain regions in the adult brain. (a) Processing linked to the identification of and interaction with stimuli is carried out in the sensorimotor regions of the brain, (b) which are separate from the valence processing in the pleasure regions of the brain. (c) In addition to this pleasure processing, there is further higher-order processing of social situations (such as theory of mind) in widespread cortical regions. (d) The hedonic mammalian brain circuitry can be revealed using behavioral and subjective measures of pleasures in rodents and humans ( Berridge and Kringelbach 2008 ).

HEDONIC HOTSPOTS

Despite having extensive distribution of reward-related circuitry, the brain appears rather frugal in “liking” mechanisms that cause pleasure reactions. Some hedonic mechanisms are found deep in the brain (nucleus accumbens, ventral pallidum, brainstem) and other candidates are in the cortex (orbitofrontal, cingulate, medial prefrontal and insular cortices). Pleasure-activated brain networks are widespread and provide evidence for highly distributed brain coding of hedonic states, but compelling evidence for pleasure causation (detected as increases in “liking” reactions consequent to brain manipulation) has so far been found for only a few hedonic hotspots in the subcortical structures. Each hotspot is merely a cubic millimeter or so in volume in the rodent brain (and should be a cubic centimeter or so in humans, if proportional to whole brain volume). Hotspots are capable of generating enhancements of “liking” reactions to a sensory pleasure such as sweetness, when stimulated with opioid, endocannabinoid, or other neurochemical modulators ( Smith et al. 2010 ).

Hotspots exist in the nucleus accumbens shell and ventral pallidum, and possibly other forebrain and limbic cortical regions, and also in deep brainstem regions, including the parabrachial nucleus in the pons (see figure 2d ). The pleasure-generating capacity of these hotspots has been revealed in part by studies in which micro-injections of drugs stimulated neurochemical receptors on neurons within a hotspot, and caused a doubling or tripling of the number of hedonic “liking” reactions normally elicited by a pleasant sucrose taste. Analogous to scattered islands that form a single archipelago, hedonic hotspots are anatomically distributed but interact to form a functional integrated circuit. The circuit obeys control rules that are largely hierarchical and organized into brain levels. Top levels function together as a cooperative heterarchy, so that, for example, multiple unanimous “votes” in favor from simultaneously participating hotspots in the nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum are required for opioid stimulation in either forebrain site to enhance “liking” above normal.

In addition, as mentioned above, pleasure is translated into motivational processes in part by activating a second component of reward termed “wanting” or incentive salience, which makes stimuli attractive when attributed to them by mesolimbic brain systems ( Berridge and Robinson 2003 ). Incentive salience depends in particular on mesolimbic dopamine neurotransmission (though other neurotransmitters and structures also are involved).

Importantly, incentive salience is not hedonic impact or pleasure “liking” ( Berridge 2007 ). This is why an individual can “want” a reward without necessarily “liking” the same reward. Irrational “wanting” without liking can occur especially in addiction via incentive-sensitization of the mesolimbic dopamine system and connected structures. At extreme, the addict may come to “want” what is neither “liked” nor expected to be liked, a dissociation possible because “wanting” mechanisms are largely subcortical and separable from cortically mediated declarative expectation and conscious planning. This is a reason why addicts may compulsively “want” to take drugs even if, at a more cognitive and conscious level, they do not want to do so. That is surely a recipe for great unhappiness (see figure 2 , bottom right).

CORTICAL PLEASURE

In the cortex, hedonic evaluation of pleasure valence is anatomically distinguishable from precursor operations such as sensory computations, suggesting existence of a hedonic cortex proper ( figure 2 ). Hedonic cortex involves regions such as the orbitofrontal, insula, medial prefrontal and cingulate cortices, which a wealth of human neuroimaging studies have shown to code for hedonic evaluations (including anticipation, appraisal, experience, and memory of pleasurable stimuli) and have close anatomical links to subcortical hedonic hotspots. It is important, however, to again make a distinction between brain activity coding and causing pleasure. Neural coding is inferred in practice by measuring brain activity correlated to a pleasant stimulus, using human neuroimaging techniques, or electrophysiological or neurochemical activation measures in animals ( Aldridge and Berridge 2010 ). Causation is generally inferred on the basis of a change in pleasure as a consequence of a brain manipulation, such as a lesion or stimulation. Coding and causation often go together for the same substrate, but they may diverge so that coding occurs alone.

Pleasure encoding may reach an apex of cortical localization in a subregion that is midanterior and roughly midlateral within the orbitofrontal cortex of the prefrontal lobe, where neuroimaging activity correlates strongly to subjective pleasantness ratings of food varieties—and to other pleasures such as sexual orgasms, drugs, chocolate, and music. Most important, activity in this special midanterior zone of orbitofrontal cortex tracks changes in subjective pleasure, such as a decline in palatability when the reward value of one food was reduced by eating it to satiety (while remaining high to another food). The midanterior subregion of orbitofrontal cortex is thus a prime candidate for the coding of subjective experience of pleasure ( Kringelbach 2005 ).

Another potential coding site for positive hedonics in orbitofrontal cortex is along its medial edge that has activity related to the positive and negative valence of affective events ( Kringelbach and Rolls 2004 ), contrasted to lateral portions that have been suggested to code unpleasant events (although lateral activity may reflect a signal to escape the situation, rather than displeasure per se) ( O’Doherty et al. 2001 ). This medial–lateral hedonic gradient interacts with an abstraction–concreteness gradient in the posterior-anterior dimension, so that more complex or abstract reinforcers (such as monetary gain and loss) are represented more anteriorly in the orbitofrontal cortex than less complex sensory rewards (such as taste). The medial region that codes pleasant sensations does not, however, appear to change its activity with reinforcer devaluation, and so may not reflect the full dynamics of pleasure.

Still other cortical regions have been implicated by some studies in coding for pleasant stimuli, including parts of the mid-insular cortex that is buried deep within the lateral surface of the brain as well as parts of the anterior cingulate cortices on the medial surface of the cortex. As yet, however, pleasure coding is not as clear for those regions as for the orbitofrontal cortex, and it remains uncertain whether insular or anterior cingulate cortices specifically code pleasure or only emotion more generally. A related suggestion has emerged that the frontal left hemisphere plays a special lateralized role in positive affect more than the right hemisphere ( Davidson and Irwin 1999 ), though how to reconcile left-positive findings with many other findings of bilateral activations of orbitofrontal and related cortical regions during hedonic processing remains an ongoing puzzle ( Kringelbach 2005 ).

It remains still unknown, however, if even the midanterior pleasure-coding site of orbitofrontal cortex or medial orbitofrontal cortex or any other cortical region actually causes a positive pleasure state. Clearly, damage to the orbitofrontal cortex does impair pleasure-related decisions, including choices and context-related cognitions in humans, monkeys, and rats ( Anderson et al. 1999 ; Nauta 1971 ). But some caution regarding whether the cortex generates positive affect states per se is indicated by the consideration that patients with lesions to the orbitofrontal cortex do still react normally to many pleasures, although sometimes showing inappropriate emotions. Hedonic capacity after prefrontal damage has not, however, yet been studied in careful enough detail to draw firm conclusions about cortical causation (for example, using selective satiation paradigms), and it would be useful to have more information on the role of orbitofrontal cortex, insular cortex, and cingulate cortex in generating and modulating hedonic states.

Pleasure causation has been so far rather difficult to assess in humans given the limits of information from lesion studies, and the correlative nature of neuroimaging studies. A promising tool, however, is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which is a versatile and reversible technique that directly alters brain activity in a brain target and where the ensuing whole-brain activity can be measured with Magnetoencephalography (MEG) ) Kringelbach et al. 2007 ). Pertinent to a view of happiness as freedom from distress, at least pain relief can be obtained from DBS of periaqueductal grey in the brainstem in humans, where specific neural signatures of pain have been found ( Green et al. 2009 ), and where the pain relief is associated with activity in the midanterior orbitofrontal cortex, perhaps involving endogenous opioid release. Similarly, DBS may alleviate some unpleasant symptoms of depression, though without actually producing positive affect.

Famously, also, pleasure electrodes were reported to exist decades ago in animals and humans when implanted in subcortical structures, including the nucleus accumbens, septum and medial forebrain bundle ( Olds and Milner 1954 ; Heath 1972 ) ( figure 2c ). However, recently we and others have questioned whether most such electrodes truly caused pleasure, or instead, only a psychological process more akin to “wanting” without “liking” ( Berridge and Kringelbach 2008 ). In our view, it still remains unknown whether DBS causes true pleasure, or if so, where in the brain electrodes produce it.

LOSS OF PLEASURE

The lack of pleasure, anhedonia, is one of the most important symptoms of many mental illnesses, including depression. It is difficult to conceive of anyone reporting happiness or well-being while so deprived of pleasure. Thus anhedonia is another potential avenue of evidence for the link between pleasure and happiness.

The brain regions necessary for pleasure—but disrupted in anhedonia—are not yet fully clear. Core “liking” reactions to sensory pleasures appear relatively difficult to abolish absolutely in animals by a single brain lesion or drug, which may be very good in evolutionary terms. Only the ventral pallidum has emerged among brain hedonic hotspots as a site where damage fully abolishes the capacity for positive hedonic reaction in rodent studies, replacing even “liking” for sweetness with “disliking” gapes normally reserved for bitter or similarly noxious tastes, at least for a while ( Aldridge and Berridge 2010 ). Interestingly, there are extensive connections from the ventral pallidum to the medial orbitofrontal cortex.

On the basis of this evidence, the ventral pallidum might also be linked to human anhedonia. This brain region has not yet been directly surgically targeted by clinicians but there is anecdotal evidence that some patients with pallidotomies (of nearby globus pallidus, just above and behind the ventral pallidum) for Parkinson’s patients show flattened affect (Aziz, personal communication), and stimulation of globus pallidus internus may help with depression. A case study has also reported anhedonia following bilateral lesion to the ventral pallidum ( Miller et al. 2006 ).

Alternatively, core “liking” for fundamental pleasures might persist intact but unacknowledged in anhedonia, while instead only more cognitive construals, including retrospective or anticipatory savoring, becomes impaired. That is, fundamental pleasure may not be abolished in depression after all. Instead, what is called anhedonia might be secondary to motivational deficits and cognitive misap-praisals of rewards, or to an overlay of negative affective states. This may still disrupt life enjoyment, and perhaps render higher pleasures impossible.

Other potential regions targeted by DBS to help with depression and anhedonia include the nucleus accumbens and the subgenual cingulate cortex. In addition, lesions of the posterior part of the anterior cingulate cortex have been used for the treatment of depression with some success ( Steele et al. 2008 ).

BRIDGING PLEASURE TO MEANING

It is potentially interesting to note that all these structures either have close links with frontal cortical structures in the hedonic network (for example, nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum) or belong to what has been termed the brain’s default network, which changes over early development ( Fransson et al. 2007 ; Fair et al. 2008 ).

Mention of the default network brings us back to the topic of eudaimonic happiness, and to potential interactions of hedonic brain circuits with circuits that assess meaningful relationships of self to social others. The default network is a steady state circuit of the brain, which becomes perturbed during cognitive tasks ( Gusnard and Raichle 2001 ). Most pertinent here is an emerging literature that has proposed the default network to carry representations of self ( Lou et al. 1999 ), internal modes of cognition ( Buckner et al. 2008 ), and perhaps even states of consciousness ( Laureys et al. 2004 ). Such functions might well be important to higher pleasures as well as meaningful aspects of happiness.

Although highly speculative, we wonder whether the default network might deserve further consideration for a role in connecting eudaimonic and hedonic happiness. At least, key regions of the frontal default network overlap with the hedonic network discussed above, such as the anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal cortices, and have a relatively high density of opiate receptors. And activity changes in the frontal default network, such as in the subgenual cingulate and orbitofrontal cortices, correlate to pathological changes in subjective hedonic experience, such as in depressed patients ( Drevets et al. 1997 ).

Pathological self-representations by the frontal default network could also provide a potential link between hedonic distortions of happiness that are accompanied by eudaimonic dissatisfaction, such as in cognitive rumination of depression. Conversely, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression, which aims to disengage from dysphoria-activated depressogenic thinking, might conceivably recruit default network circuitry to help mediate improvement in happiness via a linkage to hedonic circuitry.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The most difficult questions facing pleasure and happiness research remain the nature of its subjective experience, the relation of hedonic components (pleasure or positive affect) to eudaimonic components (cognitive appraisals of meaning and life satisfaction), and the relation of each of these components to underlying brain systems. While some progress has been made in understanding brain hedonics, it is important not to over-interpret. In particular we have still not made substantial progress toward understanding the functional neuroanatomy of happiness.

In this article, we have identified a number of brain regions that are important in the brain’s hedonic networks, and speculated on the potential interaction of hedonics with eudaimonic networks. So far the most distinctive insights have come from studying sensory pleasures, but another challenge is to understand the how brain networks underlying fundamental pleasure relate to higher pleasures, such as music, dance, play, and flow to contribute to happiness. While it remains unclear how pleasure and happiness are exactly linked, it may be safe to say at least that the pathological lack of pleasure, in anhedonia or dysphoria, amounts to a formidable obstacle to happiness.

Further, in social animals like humans, it is worth noting that social interactions with conspecifics are fundamental and central to enhancing the other pleasures. Humans are intensely social, and data indicate that one of the most important factors for happiness is social relationships with other people. Social pleasures may still include vital sensory features such as visual faces, touch features of grooming and caress, as well as in humans more abstract and cognitive features of social reward and relationship evaluation. These may be important triggers for the brain’s hedonic networks in human beings.

In particular, adult pair bonds and attachment bonds between parents and infants are likely to be extremely important for the survival of the species ( Kringelbach et al. 2008 ). The breakdown of these bonds is all too common and can lead to great unhappiness. And even bond formation can potentially disrupt happiness, such as in transient parental depression after birth of an infant (in over 10 percent of mothers and approximately 3 percent of fathers [ Cooper and Murray 1998 ]). Progress in understanding the hedonics of social bonds could be useful in understanding happiness, and it will be important to map the developmental changes that occur over a lifespan. Fortunately, social neuroscience is beginning to unravel some of the complex dynamics of human social interactions and their relation to brain activations ( Parsons et al. 2010 ).

In conclusion, so far as positive affect contributes to happiness, then considerable progress has been made in understanding the neurobiology of pleasure in ways that might be relevant. For example, we can imagine several possibilities to relate happiness to particular hedonic psychological processes discussed above. Thus, one way to conceive of hedonic happiness is as “liking” without “wanting.” That is, a state of pleasure without disruptive desires, a state of contentment ( Kringelbach 2009 ). Another possibility is that moderate “wanting,” matched to positive “liking,” facilitates engagement with the world. A little incentive salience may add zest to the perception of life and perhaps even promote the construction of meaning, just as in some patients therapeutic deep brain stimulation may help lift the veil of depression by making life events more appealing. However, too much “wanting” can readily spiral into maladaptive patterns such as addiction, and is a direct route to great unhappiness. Finally, happiness of course springs not from any single component but from the interplay of higher pleasures, positive appraisals of life meaning and social connectedness, all combined and merged by interaction between the brain’s default networks and pleasure networks. Achieving the right hedonic balance in such ways may be crucial to keep one not just ticking over but actually happy.

Future scientific advances may provide a better sorting of psychological features of happiness and its underlying brain networks. If so, it remains a distinct possibility that more among us may be one day shifted into a better situation to enjoy daily events, to find life meaningful and worth living—and perhaps even to achieve a degree of bliss.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Peterson, Eric Jackson, Kristine Rømer Thomsen, Christine Parsons, and Katie Young for helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. Our research has been supported by grants from the TrygFonden Charitable Foundation to Kringelbach and from the National Institute of Mental Health and National Institute on Drug Abuse to Berridge.

- Aldridge JW, Berridge KC. Neural Coding of Pleasure: ‘Rose-Tinted Glasses’ of the Ventral Pallidum. In: Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC, editors. Pleasures of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 62–73. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson SW, et al. Impairment of Social and Moral Behavior Related to Early Damage in Human Prefrontal Cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 1999; 2 (11):1032–37. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berridge Kent. The Debate over Dopamine’s Role in Reward: The Case for Incentive Salience. Psychopharmacology. 2007; 191 (3):391–431. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berridge KC, Kringelbach ML. Affective Neuroscience of Pleasure: Reward in Humans and Animals. Psychopharmacology. 2008; 199 :457–80. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berridge Kent C, Robinson Terry E. Parsing Reward. Trends in Neurosciences. 2003; 26 (9):507–13. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buckner RL, et al. The Brain’s Default Network: Anatomy, Function, and Relevance to Disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008; 1124 :1–38. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper PJ, Murray L. Postnatal Depression. British Medical Journal. 1998; 316 (7148):1884–6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davidson RJ, Irwin W. The Functional Neuroanatomy of Emotion and Affective Style. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1999; 3 (1):11–21. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Drevets WC, et al. Subgenual Prefrontal Cortex Abnormalities in Mood Disorders. Nature. 1997; 386 (6627):824–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fair DA, et al. The Maturing Architecture of the Brain’s Default Network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008; 105 (10):4028–32. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fransson P, et al. Resting-State Networks in the Infant Brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007; 104 (39):15531–6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fredrickson BL, et al. Open Hearts Build Lives: Positive Emotions, Induced through Loving-Kindness Meditation, Build Consequential Personal Resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008; 95 (5):1045–62. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Freud S, Riviere J. Civilization and Its Discontents. New York: J. Cape and H. Smith; 1930. [ Google Scholar ]

- Frijda Nico. On the Nature and Function of Pleasure. In: Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC, editors. Pleasures of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 99–112. [ Google Scholar ]

- Green AL, et al. Neural Signatures in Patients with Neuropathic Pain. Neurology. 2009; 72 (6):569–71. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gusnard DA, Raichle ME. Searching for a Baseline: Functional Imaging and the Resting Human Brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001; 2 (10):685–94. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haisken-De New JP, Frick R. Desktop Companion to the German SocioEconomic Panel Study (Gsoep) Berlin: German Institute for Economic Research (DIW); 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Heath RG. Pleasure and Brain Activity in Man. Deep and Surface Electroencephalograms During Orgasm. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1972; 154 (1):3–18. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- James W. To Miss Frances R. Morse. Nanheim, July 10, 1901. In: James H, editor. Letters of William James. Boston: Atlantic Monthly Press; 1920. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kahneman D. Objective Happiness. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwartz N, editors. Well-Being: The Foundation of Hedonic Psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 3–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kesebir P, Diener E. In Pursuit of Happiness: Empirical Answers to Philosophical Questions. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008; 3 :117–25. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML. Emotion. In: Gregory RL, editor. The Oxford Companion to the Mind. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 287–90. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML. The Human Orbitofrontal Cortex: Linking Reward to Hedonic Experience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005; 6 (9):691–702. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML. The Pleasure Center: Trust Your Animal Instincts. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML. The Hedonic Brain: A Functional Neuroanatomy of Human Pleasure. In: Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC, editors. Pleasures of the Brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 202–21. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC. Pleasures of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML, et al. Deep Brain Stimulation for Chronic Pain Investigated with Magnetoencephalography. Neuroreport. 2007; 18 (3):223–28. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML, et al. A Specific and Rapid Neural Signature for Parental Instinct. PLoS ONE. 2008; 3 :2. e1664. doi: 10.371/journal.pone.0001664. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML, Rolls ET. The Functional Neuroanatomy of the Human Orbitofrontal Cortex: Evidence from Neuroimaging and Neuropsychology. Progress in Neurobiology. 2004; 72 (5):341–72. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC. Towards a Functional Neuroanatomy of Pleasure and Happiness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2009; 13 (11):479–87. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuppens P, et al. The Role of Positive and Negative Emotions in Life Satisfaction Judgment across Nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008; 95 (1):66–75. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Laureys S, et al. Brain Function in Coma, Vegetative State, and Related Disorders. Lancet Neurology. 2004; 3 (9):537–46. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lou HC, et al. A 15O-H 2 O PET Study of Meditation and the Resting State of Normal Consciousness. Human Brain Mapping. 1999; 7 (2):98–105. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller JM, et al. Anhedonia after a Selective Bilateral Lesion of the Globus Pallidus. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006; 163 (5):786–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nauta WJ. The Problem of the Frontal Lobe: A Reinterpretation. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1971; 8 (3):167–87. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nesse RM. Natural Selection and the Elusiveness of Happiness. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences. 2004; 359 (1449):1333–47. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Doherty J, et al. Abstract Reward and Punishment Representations in the Human Orbitofrontal Cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 2001; 4 (1):95–102. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oishi S, et al. The Optimal Level of Well-Being: Can We Be Too Happy? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007; 2 :346–60. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Olds J, Milner P. Positive Reinforcement Produced by Electrical Stimulation of Septal Area and Other Regions of Rat Brain. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1954; 47 :419–27. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parsons CE, et al. The Functional Neuroanatomy of the Evolving Parent-Infant Relationship. Progress in Neurobiology. 2010 forthcoming. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The Neural Basis of Drug Craving: An Incentive-Sensitization Theory of Addiction. Brain Research Reviews. 1993; 18 (3):247–91. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seligman ME, et al. Positive Psychology Progress: Empirical Validation of Interventions. American Psychologist. 2005; 60 (5):410–21. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith KS, et al. Hedonic Hotspots: Generating Sensory Pleasure in the Brain. In: Kringelbach ML, Berridge KC, editors. Pleasures of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 27–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Steele JD, et al. Anterior Cingulotomy for Major Depression: Clinical Outcome and Relationship to Lesion Characteristics. Biol Psychiatry. 2008; 63 (7):670–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinbeck J, Ricketts EF. The Log from the Sea of Cortez. London: Penguin; 1941. [ Google Scholar ]

- Steiner JE, et al. Comparative Expression of Hedonic Impact: Affective Reactions to Taste by Human Infants and Other Primates. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2001; 25 (1):53–74. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Theology of Joy & the Good Life

Building a transformative movement driven by a Christian articulation of the joy that attends the flourishing human life.

The Theology of Joy and the Good Life project sought to restore joy to the center of Christian reflection on the nature of the good life and to restore the question of the good life to the core of Christian theology, the world’s colleges and universities, and our most significant global conversations.

Joy is fundamental to human existence and well-being, yet it is an elusive phenomenon that resists definition. For more than two millennia, the articulation and cultivation of joy was at the center of Jewish and Christian scripture, theology, and practices—an articulation and cultivation that in turn was grounded in and evolved over centuries of lived human experience, observation and discernment. Notwithstanding the importance of joy to human well-being and the deep, ancient religious foundations for understanding and cultivating joy, the very idea of joy has all but disappeared from modern theological reflection, is all but ignored by the social sciences, and is increasingly absent from lived experience. The consequence is a “flattening out,” a “graying,” of human life and communities—abundance of entertainment notwithstanding—and a sharp bloom of individual and communal dysfunction.

The Theology of Joy & the Good Life project was made possible by the John Templeton Foundation with additional support from the McDonald Agape Foundation.

What Is Joy?

"I look at joy as an act of resistance against despair and its forces. ... Joy in that regard is a work, that can become a state, that can become a way of life."

Willie James Jennings

"In the Jewish tradition, joy is something that happens when God finally does something that people have been waiting for."

N.T. Wright

Content & Programming

Consultations.

We conducted a multidisciplinary study of the traditional scriptural, theological, and devotional foundations for a theology of joy, exploring the most current social science resources that would enrich and inform that theological investigation.

Video Interviews

In conjunction with each Theology of Joy and the Good Life consultation, Miroslav Volf and the Center staff have conducted interviews with a number of contributing scholars.

Learn More →

Theology & the Research Sciences

The project seeks to involve and integrate the work of scholars in a variety of disciplines. For this reason, the project hosted a consultation on Theology and the Research Sciences.

Project Description

The Theology of Joy and the Good Life project has grown out of research conducted during the Center’s 2014 work on the “Theology of Joy.” This research led to several key insights and an operating hypothesis about the nature of joy and its relationship to the good life that we seek to research and test. Our hypothesis is that the good life has three basic dimensions:

- Agential (what you do)

- Circumstantial (how the world is for you, both materially and culturally)

- Affective (how you feel)

Given this formal account, joy is revealed as the crown of the good life, both naming its affective dimension, and yet integrating all three. Joy, as a positive emotion (an affective concern-based construal), is a positive affective response to an objective external good, construed rightly and about which one is rightly concerned.

Therefore, one cannot describe joy adequately without reference to the good life. Likewise, at least on the Christian account, one cannot describe the good life adequately without reference to joy. Each is integral to the other. When this essentially integral relationship of joy and the good life is grasped, it becomes apparent that joy is the affective dimension of the good life and that the good life is the life marked by joy.

This formal description constitutes the working hypothesis of the project , which the full proposal is designed to test by conducting research in three closely-related areas.

- The core body of research investigates joy and the good life so as to test and articulate this fundamental integrity of joy and the good life. That is, this research explores whether and to what extent joy is indeed a dimension of the good life and the good life is one marked by true joy. This research will be advanced through two series of consultations—Joy Among the Virtues, Actions, and Emotions and Joy and the Phenomena of Human Existence—as well as by YCFC research scholars, project leadership team members, and work funded by sub-grants and competitions. This research serves as the foundation for all other project activities, including the development of “Christ and the Good Life,” a new course that invites seminary and divinity school students to reflect on the particular shape the good life assumes when Christ is taken to be the key to human flourishing (offered for the first time in Fall 2015).

- Our 2014 consultation on joy and adolescence concluded that adolescence is a pivotal season for the cultivation of the good life of joy. For this reason, the project also studies factors that foster or inhibit joy in this crucial season of life and translate the fruits of this research into practical tools for youth ministry. This is the focus of the subproject on Joy and Adolescent Faith & Flourishing.

- The project explores joy and its analogs in other traditions, recognizing that the affective dimension of the good life may be described differently in different religious and philosophical traditions. In helping us attend to these differences and the ways that they shape the visions of the good life that motivate our lives, theology can serve as a bridge-builder rather than gatekeeper. This is the focus of the subproject on Joy and its Analogs in Other Traditions which will award eight $20k sub-grants to scholar-practitioners of non-Christian traditions to articulate visions of the good life within these traditions with particular attention to the affective dimension.

In all of its activities, the project seeks to involve and integrate the work of scholars working in sometimes disparate theological subfields, casting vision for a renewed and unified theological academy that places the articulation of normative visions of the good life at the core of its work. For this reason, the project begins in AY15-16 with a series of consultations on the “Future of Theology.”

Over the three years of the Templeton Foundation grant (2015-2018), the project will distribute more than $900,000 in subgrants and prizes, inviting a wide network of scholars, pastors, and seminarians to participate in the life of the project. The project also will sponsor monthly public lectures, support the development of two university courses, produce a growing video library of contributors and guests, edited volumes and books—including an anthology of poetry—and curricula for two church-based youth ministry courses.

Ultimately, the Theology of Joy and the Good Life project aims not only to conduct theological research, but to lay the foundations for a movement pursuing questions of the good life in the academy and the culture more broadly. From the start, the project is led by an extraordinary group of scholars and religious leaders from more than twenty institutions around the globe, including Jürgen Moltmann, Jonathan Sacks, N. T. Wright, and Nicholas Wolterstorff.

The Theology of Joy and the Good Life project is made possible by a $4.2 million grant from the John Templeton Foundation with additional support from the Youth Ministry Initiative , the McDonald Agape Foundation , Yale Center for Faith & Culture donors, and the Yale Divinity School.

Other Legacy Projects

From 2003 to 2018, the Yale Center for Faith & Culture has pursued our purpose along a variety of completed initiatives, always dedicated to building bridges of religious, political, and cultural discourse, fostering truth-seeking conversations, and impacting change in individual and community life. Browse other legacy projects below.

Sarah Smith Memorial Conference

Fostering moral leadership in all spheres of life.

Faith & Globalization

Exploring the profound impact of religious faith in a world where political, economic and social spheres are increasingly interconnected.

Ethics & Spirituality in the Workplace

Encouraging business leaders to incorporate faith-based virtues into their work and promoting efforts to align business practice with authentic human flourishing and the global common good.

A Common Word

Loving our Muslim neighbors by affirming our common call to love God and neighbor.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

There are roughly two philosophical literatures on “happiness,” each corresponding to a different sense of the term. One uses ‘happiness’ as a value term, roughly synonymous with well-being or flourishing. The other body of work uses the word as a purely descriptive psychological term, akin to ‘depression’ or ‘tranquility’. An important project in the philosophy of happiness is simply getting clear on what various writers are talking about: what are the important meanings of the term and how do they connect? While the “well-being” sense of happiness receives significant attention in the contemporary literature on well-being, the psychological notion is undergoing a revival as a major focus of philosophical inquiry, following on recent developments in the science of happiness. This entry focuses on the psychological sense of happiness (for the well-being notion, see the entry on well-being ). The main accounts of happiness in this sense are hedonism, the life satisfaction theory, and the emotional state theory. Leaving verbal questions behind, we find that happiness in the psychological sense has always been an important concern of philosophers. Yet the significance of happiness for a good life has been hotly disputed in recent decades. Further questions of contemporary interest concern the relation between the philosophy and science of happiness, as well as the role of happiness in social and political decision-making.

1.1 Two senses of ‘happiness’

1.2 clarifying our inquiry, 2.1 the chief candidates, 2.2 methodology: settling on a theory, 2.3 life satisfaction versus affect-based accounts, 2.4 hedonism versus emotional state, 2.5 hybrid accounts, 3.1 can happiness be measured, 3.2 empirical findings: overview, 3.3 the sources of happiness, 4.1 doubts about the value of happiness, 4.2 restoring happiness to the theory of well-being, 4.3 is happiness overrated, 5.1 normative issues, 5.2 mistakes in the pursuit of happiness, 5.3 the politics of happiness, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the meanings of ‘happiness’.

What is happiness? This question has no straightforward answer, because the meaning of the question itself is unclear. What exactly is being asked? Perhaps you want to know what the word ‘happiness’ means. In that case your inquiry is linguistic. Chances are you had something more interesting in mind: perhaps you want to know about the thing , happiness, itself. Is it pleasure, a life of prosperity, something else? Yet we can’t answer that question until we have some notion of what we mean by the word.

Philosophers who write about “happiness” typically take their subject matter to be either of two things, each corresponding to a different sense of the term:

- A state of mind

- A life that goes well for the person leading it

In the first case our concern is simply a psychological matter. Just as inquiry about pleasure or depression fundamentally concerns questions of psychology, inquiry about happiness in this sense—call it the (long-term) “psychological sense”—is fundamentally the study of certain mental states. What is this state of mind we call happiness? Typical answers to this question include life satisfaction, pleasure, or a positive emotional condition.

Having answered that question, a further question arises: how valuable is this mental state? Since ‘happiness’ in this sense is just a psychological term, you could intelligibly say that happiness isn’t valuable at all. Perhaps you are a high-achieving intellectual who thinks that only ignoramuses can be happy. On this sort of view, happy people are to be pitied, not envied. The present article will center on happiness in the psychological sense.

In the second case, our subject matter is a kind of value , namely what philosophers nowadays tend to call prudential value —or, more commonly, well-being , welfare , utility or flourishing . (For further discussion, see the entry on well-being . Whether these terms are really equivalent remains a matter of dispute, but this article will usually treat them as interchangeable.) “Happiness” in this sense concerns what benefits a person, is good for her, makes her better off, serves her interests, or is desirable for her for her sake. To be high in well-being is to be faring well, doing well, fortunate, or in an enviable condition. Ill-being, or doing badly, may call for sympathy or pity, whereas we envy or rejoice in the good fortune of others, and feel gratitude for our own. Being good for someone differs from simply being good, period: perhaps it is always good, period, for you to be honest; yet it may not always be good for you , as when it entails self-sacrifice. Not coincidentally, the word ‘happiness’ derives from the term for good fortune, or “good hap,” and indeed the terms used to translate it in other languages often have similar roots. In this sense of the term—call it the “well-being sense”—happiness refers to a life of well-being or flourishing: a life that goes well for you.

Importantly, to ascribe happiness in the well-being sense is to make a value judgment : namely, that the person has whatever it is that benefits a person. [ 1 ] If you and I and have different values, then we may well differ about which lives we consider happy. I might think Genghis Khan had a happy life, because I think what matters for well-being is getting what you want; while you deny this because you think a life of evildoing, however “successful,” is sad and impoverished.

Theories of well-being—and hence of “happiness” in the well-being sense—come in three basic flavors, according to the best-known taxonomy (Parfit 1984): hedonism, desire theories, and objective list theories. Whereas hedonists identify well-being roughly with experiences of pleasure, desire theorists equate it with the satisfaction of one’s desires— actually getting what you want, versus merely having certain experiences. Both hedonism and desire theories are in some sense subjectivist, since they ground well-being in the individual’s subjective states. Objective list theorists, by contrast, think some things benefit us independently of our attitudes or feelings: there are objective prudential goods. Aristotelians are the best-known example: they take well-being ( eudaimonia ) to consist in a life of virtuous activity—or more broadly, the fulfillment of our human capacities. A passive but contented couch potato may be getting what he wants, and he may enjoy it. But he would not, on Aristotelian and other objective list theories, count as doing well, or leading a happy life.

Now we can sharpen the initial question somewhat: when you ask what happiness is, are you asking what sort of life benefits a person? If so, then your question concerns matters of value, namely what is good for people—the sort of thing that ethical theorists are trained to address. Alternatively, perhaps you simply want to know about the nature of a certain state of mind—happiness in the psychological sense. In this case, some sort of psychological inquiry will be needed, either philosophical or scientific. (Laypersons often have neither sort of question in mind, but are really asking about the sources of happiness. Thus it might be claimed, say, that “happiness is being with good friends.” This is not a view about the nature or definition of happiness, but rather a theory about the sorts of things that tend to make us happy. It leaves unanswered, or takes for granted, the question of just what happiness is , such that friends are a good source of it.)

In short, philosophical “theories of happiness” can be about either of at least two different things: well-being, or a state of mind. [ 2 ] Accordingly, there are essentially two bodies of philosophical literature about “happiness” and two sets of debates about its nature, though writers often fail to distinguish them. Such failures have generated much confusion, sometimes yielding bogus disagreements that prove to be merely verbal. [ 3 ] For instance, some psychologists identify “happiness” with attitudes of life satisfaction while remaining neutral on questions of value, or whether Bentham, Mill, Aristotle, or any other thinker about the good life was correct. Such researchers employ the term in the psychological sense. Yet it is sometimes objected against such claims that life satisfaction cannot suffice for “happiness” because other things, like achievement or knowledge, matter for human well-being. The objectors are confused: their opponents have made no claims about well-being at all, and the two “sides,” as it were, are simply using ‘happiness’ to talk about different things. One might just as sensibly object to an economist’s tract on “banks” that it has nothing to say about rivers and streams.

Which use of ‘happiness’ corresponds to the true meaning of the term in contemporary English? Arguably, both. The well-being usage clearly dominates in the historical literature through at least the early modern era, for instance in translations of the ancient Greeks’ ‘ eudaimonia ’ or the Latin ‘ beatitudo ’, though this translation has long been a source of controversy. Jefferson’s famous reference to “the pursuit of happiness” probably employed the well-being sense. Even later writers such as Mill may have used the term in its well-being sense, though it is often difficult to tell since well-being itself is often taken to consist in mental states like pleasure. In ordinary usage, the abstract noun ‘happiness’ often invites a well-being reading. And the locution ‘happy life ’ may not naturally take a psychological interpretation, for the simple reason that lives aren’t normally regarded as psychological entities.

Contrast this with the very different meaning that seems to attach to talk of “ being happy.” Here it is much less clear that we are talking about a property of a person’s life; it seems rather to be a property of the person herself. To be happy, it seems, is just to be in a certain sort of psychological state or condition. Similarly when we say that so-and-so “is happy” (as opposed to saying that he is leading a happy life). This psychological usage, arguably, predominates in the current vernacular. Researchers engaged in the self-described “science of happiness” usually do not take themselves to be making value judgments when they proclaim individuals in their studies to be happy. Nor, when asserting that a life satisfaction study shows Utahans to be happier than New Yorkers, are they committing themselves to the tendentious claim that Utahans are better off . (If they are, then the psychology journals that are publishing this research may need to revise their peer-review protocols to include ethicists among their referees.) And the many recent popular books on happiness, as well as innumerable media accounts of research on happiness, nearly all appear to take it for granted that they are talking about nothing more than a psychological condition.

Henceforth ‘happiness’ will be used in the long-term psychological sense, unless otherwise specified. Note, however, that a number of important books and other works on “happiness” in recent decades have employed the well-being sense of the term. Books of this sort appear to include Almeder 2000, Annas 1993, 2011, Bloomfield 2014, Cahn and Vitrano 2015, Kenny and Kenny 2006, McMahon 2005, McPherson 2020, Noddings 2003, Russell 2013, White 2006, and Vitrano 2014, though again it is not always clear how a given author uses the term. For discussion of the well-being notion, see the entry on well-being . [ 4 ]

2. Theories of happiness

Philosophers have most commonly distinguished two accounts of happiness: hedonism , and the life satisfaction theory. Hedonists identify happiness with the individual’s balance of pleasant over unpleasant experience, in the same way that welfare hedonists do. [ 5 ] The difference is that the hedonist about happiness need not accept the stronger doctrine of welfare hedonism; this emerges clearly in arguments against the classical Utilitarian focus on happiness as the aim of social choice. Such arguments tend to grant the identification of happiness with pleasure, but challenge the idea that this should be our primary or sole concern, and often as well the idea that happiness is all that matters for well-being.

Life satisfaction theories identify happiness with having a favorable attitude toward one’s life as a whole. This basic schema can be filled out in a variety of ways, but typically involves some sort of global judgment: an endorsement or affirmation of one’s life as a whole. This judgment may be more or less explicit, and may involve or accompany some form of affect. It may also involve or accompany some aggregate of judgments about particular items or domains within one’s life. [ 6 ]