This website uses cookies.

We would love to chat with you!

Wait! Before you go....Please leave your email and we will be in touch.

Different Interview Styles and When to Use Them

Warren Sukernek

What are the Different Interviewing Styles?

Conducting effective interviews with flocareer.

Interviewing is one of the most crucial parts of the recruiting process. Understanding the art of conducting interviews can make the hiring process smoother and help you hire suitable candidates. There are many types of interviews, each suitable for different occasions. For example, the interview style may differ by career field, the position's seniority, and the interviewer's skillset.

This article will help you understand the different interviewing styles and the best scenarios to use them.

The interviewing style you should use should depend on the role and your skillset. Using the right interviewing technique can help you make more informed hiring decisions. Here are the three most common styles of conducting interviews:

1. The Conversational Interview

The most common interviewing style is conversational. This is a form of an unstructured and informal interview where interviewers skim through participants’ CVs and ask questions in an ad-hoc manner rather than referring to a pre-set question bank. The benefit of the conversational style is that it puts candidates at ease and can help them open up about their experiences and reveal their personality traits.

The conversational style of interviewing is not without limitations. Hiring managers should avoid relying on them as a predictive tool of candidates’ performance as conversational interviews have lower predictive validity than structured interviews. Instead, you can ask candidates to take an aptitude test for better reliability and combine these scores with an interview to understand the candidate’s character and values.

Another way to improve your conversational interviews is to prepare questions, even if the tone is informal. Having standardized interviews allows you to assess the quality of answers you receive and compare candidates objectively. FloCareer’s interview structuring solutions can help you create a unique and relevant question bank, helping you conduct consistent and bias-free interviews.

2. The Direct Interview

During direct interviews, the hiring manager presents candidates with straightforward questions. Direct interviews involve more structure than the conversational interview style and they may even lead to interview anxiety.

However, the direct interview also has many perks , e.g., interviewees will be unlikely to veer off-topic as the interview is timed and focused. These interviews are also suitable for assessing the candidate's character, skills, area of interest, and attitudes.

Image: https://www.pexels.com/photo/ethnic-female-psychotherapist-listening-to-black-clients-explanation-5699479/

How to make the most of direct interviews?

The biggest drawback of this interview is that it makes interviewees nervous. This anxiety can show up in their interview as them blanking out on responses, general rigidity, and not getting enough room to voice their thoughts.

To prevent this, interviewers should choose open-ended questions which give candidates enough room to share their insights and experiences without feeling cornered. In addition, if you seek candidates with specific skills, you can give your candidates an opportunity to demonstrate their skills.

Seeing how well applicants answer situational questions — questions asking how they would respond to a hypothetical scenario — is predictive of their job performance. Finally, going for ‘past behavioral’ questions, which sound like ‘Tell me about a time when…’, are also strongly predictive measures.

These measures asked through open-ended questions will likely make for a robust direct interview assessment for your next hire.

3. The Behavioral Interview

As findings from the behavioral school of psychology made their way into the workforce in the 1970s, the outcome was the behavioral interview of today. This style analyzes a candidate’s past performance more precisely than asking a few questions.

So, instead of asking what candidates would do in specific scenarios, behavioral interviews try to revisit situations candidates found themselves in and, more importantly, what they did to make the most of those scenarios.

Image: https://pixabay.com/images/id-544404/

Such interviews go into detail to assess the course of action taken by the individual and the insights they gleaned from the situation. Behavioral interview questions might also probe the emotional state of candidates, especially during a stressful work situation.

Based on how candidates evaluate their performance, the interviewer can understand their efficacy in managing stressful situations or circumstances requiring skills like creativity, problem-solving, or critical thinking.

How to make the most of behavioral interviews:

Ensure that you design questions to deal with the issues presented by the situation rather than confuse the applicant. Listening skills are essential to know when to probe deeper into an applicant’s retelling.

Asking questions like ‘what made you do that?’, ‘how did you get around that problem?’ and ‘what was going through your mind?’ can help you get more insight from the responses candidates give. You can also delve into bad situations to gauge whether candidates have reflected on what they could've done better.

4. The Structured Interview

A structured interview is a standardized and objective interview format where each application is asked the same set of questions in the same order. The candidate’s responses are then evaluated using a predetermined scale, allowing the hiring manager to compare applicants with each other in an unbiased way.

There are many benefits of the structured interview: asking structured questions related to a candidate’s background is predictive of the candidate’s job performance. In addition, by streamlining the recruitment efforts, they help hiring managers save time spent preparing for each interview. Moreover, since they reduce unconscious hiring bias , they can help businesses create more diverse teams.

How to make the most of structured interviews:

Creating an appropriate interview structure is key to evaluating candidates successfully. FloCareers’s army of over 3,000 freelance interviews uses analytics and insights to create the right question bank for your team to use. Moreover, FloCareer’s Live Interview Platform lets you incorporate coding assessments and scenario-based tests into the interview process, helping you evaluate the applicant’s skills and find the best hire.

5. Technical Assessment

What better way to judge an applicant than by seeing them in action, right? While all the other techniques take care of the cultural and behavioral fit, it’s crucial to also see their coding ability live. This also allows you to test for logic and to see whether they are up to date with the newest coding practices. Our interview as a software service helps you integrate technical assessments as part of your recruiting process. We’ve a large database of technical questions that we ask candidates and they’re expected to either write down or whiteboard the solution. If you prefer, we also allow you to use an integrated development environment as part of the tests.

The interviewing style that works for one person might not work for another, so testing the different types can help you understand what works for you. Note that interview styles can vary based on the roles you are hiring for.

Ensure that you aren’t forcing any styles to fit a situation; instead, pick the style according to the situation. Some interviewers might find that blending all the styles works best for them.

Assessing skills fairly and transparently is a crucial component of good interviewing, and FloCareer has the best tools to help you do this. From interview structure curation to the live interview platform, our products and solutions enable you to make better hires effectively and efficiently.

Interview as a Service

automated interviews

video interviews

Interviewing

structured interview

technical interviews

flow careers

live Interview platform

live interviews

technical interview platform

interview platform

freelance interviewers

high quality interviews

flow career

technical interview process

structure of interview

technical assessments

video interview platform

interview service

interview outsourcing company

outsource expert interviewers

screening interview

karat interview

tech interview process

structured interviews

interview as a service company

interview structure

accelerate hiring

video interview

on demand interviews service

Flocareer platform

interview outsourcing

technical interviewers

structured interview strategy

behavioral interviews

interviewing styles

direct interview

interview styles

conversational interview

interviews with flocareer

FloCareer was created and is run with the goal of empowering hiring teams across the globe by finding best match for their requirements using technology and power of gig economy. We enable hiring teams by offloading them from taking first few rounds of in-depth technical interviews on FloCareer’s state of the art Interview platform.

You may also want to read

5500+ Freelance Interviewers - Outsource Your Technical Interviews

Be A Freelance Interviewer with FloCareer - Side Gig to feed your passion

Why You Should Outsource Your Technical Interviews With FloCareer

- Find a company

The rhythm of the interview: expert tips for speaking on the big day

Sep 26, 2022

Journaliste indépendante.

They say that a successful job interview follows the 80/20 rule: the candidate speaks for 80% of the time, and the recruiter speaks for the remaining 20%. The recruiter’s role is to ask the right questions and supply key details about the role. The candidate is there to talk about their experiences and prove that they’re the best person for the job , using relevant and carefully worded answers. Well, that’s the theory …

In reality, things aren’t that simple. Managing your speaking time in an interview is no small feat: chances are, a little voice in your head is second-guessing your every sentence. “Take your time! No, hurry up. Now slow down! Time is running out: go, go, go!” How can you know if you’re speaking too much or not enough? Margaux Lefebvre, public speaking expert, is here to guide you through some classic interview situations, pointing out pitfalls to avoid and giving you the tools that you need to shine .

The monologue: to be, or not to be?

You’ve launched into a run-on speech that would make even a seasoned Shakespearean actor flinch. Words are practically falling out of your mouth, with ideas flying around left and right. By the time you’ve realized what’s happening, it’s already too late. Or is it?

“ Not necessarily,” says Lefebvre. It’s best to avoid the extremes—talking so much that the interviewer can’t get a word in, or remaining practically mute throughout the whole interview—but how a listener “feels” time depends on how you make them feel. “I like to use movies as an example,” she says. “ Several hours might go by in a flash in front of something like Lord of the Rings, but a thirty-minute short film might seem to drag on for eternity.” So, if you think that the ins and outs of your latest project are interesting enough to merit a full breakdown, then work out what you’re going to say ahead of time: that way, you can keep your listener hooked and draw their attention to the most important points.

You’re more likely to drone on if you feel like you’ve been put on the spot, perhaps in reaction to an unexpected question . You’ll start to explain yourself, then back up, go off at a tangent, keep adding ideas here and there, and before you know it, you’re rambling incoherently. “That’s why preparation is so important,” states Lefebvre. “You need to have one or two key messages you want to get across in your answers to any type of question. And if you get asked a question you weren’t expecting, take a few seconds to think about your response before you open your mouth.”

But what if you have a lot to say? The key is to remember that an interview is meant to be a conversation . Ask the interviewer how long they want to spend on a question: “ I have several relevant experiences in this area. How many would you like me to tell you about?” Alternatively, you could give a quick overview of what you have to say, then ask the interviewer if they’d like to hear more: “ Those are the main aspects, should I go on?”

Bridging awkward gaps in conversation

Talking too much can be a problem—but then, so can talking too little. Uncomfortable silences can be unnerving during an interview, especially if you don’t know whether it’s up to you or the interviewer to get things going again.

If your answer to a question is met with silence, perhaps the interviewer just needs a few moments to absorb what you’ve said , or maybe they’re thinking about their next question . If things are getting uncomfortable and the recruiter seems receptive, Lefebvre suggests asking a question (“ Do you want me to go on?” ) or even using humor to break the silence. “Acknowledging the silence can create a feeling of complicity between you and the recruiter, strengthening the human connection. Humor can disperse tension and lighten the tone of the discussion,” she explains.

What if you can’t answer a question ? Lefebvre’s answer is simple: don’t panic! An honest and open response is a token of maturity and candor. “Humor and sincerity are the best tools for building empathy. Whatever happens, admitting that you don’t have all the answers is rarely a bad move.”

The power of silence

Yes, silence can be stressful, but it can also be a valuable tool. That’s why you don’t need to jump in with an immediate answer to every question. Lefebvre suggests taking two to three seconds before responding, something she calls “ smart silence”. This short break allows the interviewer to re-focus their attention on what you’re about to say and shows you’ve thought about your answer.

You’ve heard the term “ethos” before, but did you know that the original Latin meaning relates to the impression made on others by a speaker? The greatest speakers know how to use silence to their own ends, to mark a point or create a compelling atmosphere: “ Silence is a key element of the ethos. It creates an impression of mastery. It makes you the master of your time,” says Lefebvre.

Silence also gives you time to think. A few precious seconds can be enough to develop a constructed, reasoned response to a question—and that’s far better than giving an immediate but irrelevant answer.

Paraverbal communication in interviews

Paraverbal communication is everything that relates to speech besides the actual words you use: your tone of voice, volume, speed, and so on. Do you tend to talk fast? Stress often causes people to speak even faster , so you’ll want to slow down. Lefebvre recommends practicing reading aloud to help slow yourself down and suggests candidates focus on their breathing.

Another point to think about is how you finish your sentences. Do you tend to trail off? Do you feel the need to say “that’s all” at the end of every answer? If you’re aware of any verbal tics you might have, you can do something about them: finishing your sentences neatly gives the impression of confidence. When you speak , your sentences will naturally “wind down”: at the end of a phrase, your speech slows, and the pitch of your voice gradually descends. The listener will know you’ve finished without you needing to tell them . “Don’t be afraid to leave a moment of silence at the end of your answer,” adds Lefebvre. “Silence is a clear sign that you’ve finished speaking, and the interviewer will pick up on that.” If the silence is getting uncomfortable, then you can always ask a question, as we said earlier. Aaaaand … that’s all.

Translated by Catherine Prady

Photo: Welcome to the Jungle

Follow Welcome to the Jungle on Facebook , LinkedIn , and Instagram , and subscribe to our newsletter to get our latest articles every day!

More inspiration: Ace your job interview

Recruitment red flags: How to spot greenwashing in an interview

If sustainability matters to you, watch out for the over-use of words like "eco-friendly" and "100% natural" ...

Apr 30, 2024

What we can learn from the most iconic TV show interviews

Interviews are tough for everyone, even fictional characters. So, what can we take away from some of TV’s most memorable job interviews?

Feb 22, 2024

Confident, not cocky: Perfecting the art of humble confidence in interviews

Too much of one thing? Not enough of another? Here’s how to showcase confidence in an interview without coming across too strong.

Jan 09, 2024

Unemployed: How to avoid stereotypes during a job interview

Whether you were laid off, took a personal break, or spent the past year as a caregiver, getting back on the market after unemployment can be hard.

Jan 04, 2024

Ink and metal: Should you hide tattoos and piercings in an interview?

It may feel like an outdated question, but physical appearance plays a role in job interviews (whether we like it or not).

Dec 14, 2023

The newsletter that does the job

Want to keep up with the latest articles? Twice a week you can receive stories, jobs, and tips in your inbox.

Looking for your next job opportunity?

Over 200,000 people have found a job with Welcome to the Jungle.

Interviewing Preparation

Interview preparation.

Prepare for your interview by researching your interview subject and coming up with a list of prepared questions.

Learning Outcomes

Discuss how interviewers should best prepare for an interview

Key Takeaways

- Thoroughly doing your homework on a potential interview subject not only helps you to build rapport with him or her during your interview, it helps to confirm whether or not your interviewee makes an appropriate primary source.

- Whether you write out talking points or specific questions, make sure to pay attention during your interview to look for opportunities to ask follow-up questions.

- Both interviewers and interviewees should keep in mind factors such as timing and pacing to keep the discussion focused.

- talking point : A specific topic raised in a conversation or argument which is intended as a basis for further discussion, especially one which represents a point of view.

- interview : A formal meeting in person, for the assessment of a candidate or applicant.

Preparing for Your Interview

Preparing for Your Interview : Make sure you’ve done your homework and research before heading to an interview!

An interview is a conversation between two or more people where questions are asked by the interviewer to elicit facts or statements from the interviewee. Interviews are used for purposes that range from evaluating job candidates to collecting market research and creating news stories. Interviews are usually led and completed by the interviewer based on what the interviewee says. They tend to be far more personal than questionnaires and surveys, as the interviewer works directly with the interviewee. The format also ranges depending on the context, purpose, and constraints for both parties.

Question Preparation

Once you’ve figured out everything you need to know about your interview subject or interviewer, it is time to prepare your questions. There are two approaches to this. First, you can make a list of talking points. These aren’t necessarily specific questions, however they serve as a guide for main points you want to make sure you hit over the course of your interview. Alternatively, you can be even more prepared by coming up with a set of questions for your interview subject or interviewer. Make sure you ask enough questions to get the information, or to demonstrate your knowledge of a certain subject or industry. Keep in mind timing and pacing during the interview. It is easy to overwhelm or appear aggressive if you ask too many probing or irrelevant questions.

As an interviewer, you may use open-ended and close-ended questions. Close-ended questions typically have a yes or no answer, or some kind of definitive fact. Open-ended questions are those that are open to interpretation and experience.

Preparation for Interviewers

Even if you are planning to interview the foremost expert in your subject field, you should always do some research into your interview subject no matter how famous they might be. You’ll want to do this for a couple of reasons.

First, you’ll want to establish rapport right away with your interview subject, even from the very first communication you have with the person asking if they’ll consent to being a primary source for your research. Second, you’ll want to evaluate that you have in fact selected the best person with the most credibility and authority to speak to that information for which you seek.

Interview Conduct

Listen to your interviewee, ask questions, respect boundaries, avoid leading questions, and don’t interrupt to ensure a successful interview.

State the best practices for conducting an interview

- An interview, in qualitative research, is a conversation where questions are asked to elicit information, usually pertaining to a product or service, as a means of gaining a better understanding of how a consumer thinks.

- It is important to listen not only to what the participant is actually saying but also to the subtext and flow of the conversation.

- It is essential that while the participant is being interviewed they are being encouraged to explore their experiences in a manner that is sensitive and respectful.

- Ask open-ended questions, not leading ones.

- Participants should feel comfortable and respected throughout the entire interview—thus interviewers should avoid interrupting participants whenever possible.

An interview, in qualitative research, is a conversation where questions are asked to elicit information, usually pertaining to a product or service, as a means of gaining a better understanding of how a consumer thinks. The interviewer is usually a professional or paid researcher, sometimes trained, who poses questions to the interviewee, in an alternating series of usually brief questions and answers.They are a standard part of qualitative research, in contrast to focus groups in which an interviewer questions a group of people at the same time. The qualitative research interview seeks to describe and the meanings of central themes in the life world of the subjects. The main task in interviewing is to understand the meaning of what the interviewees say. Interviewing, when considered as a method for conducting qualitative research, is a technique used to understand the experiences of others.

Approach to Interviewing

When choosing to interview as a method for conducting qualitative research, it is important to be tactful and sensitive in your approach. Interviewer and researcher, Irving Seidman, devotes an entire chapter of his book, Interviewing as Qualitative Research , to the import of proper interviewing technique and interviewer etiquette. Some of the fundamentals of his technique are summarized below.

According to Seidman, listening is both the hardest as well as the most important skill in interviewing. Furthermore, interviewers must be prepared to listen on three different levels: they must listen to

- what the participant is actually saying,

- the “inner voice” or subtext of what the participant is communicating, and

- the process and flow of the interview, so as to remain aware of how tired or bored the participant is.

The listening skills required in an interview require more focus and attention to detail than what is typical in normal conversation. Therefore, it is often helpful for interviewers to take notes while the participant responds to questions or to tape-record the interviews themselves to as to be able to more accurately transcribe them later.

Ask Questions

While an interviewer generally enters each interview with a predetermined, standardized set of questions, it is important that they also ask follow-up questions throughout the process. Such questions might encourage a participant to elaborate upon something poignant that they’ve shared and are important in acquiring a more comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. Additionally, it is important that an interviewer ask clarifying questions when they are confused.

Respect Boundaries

Seidman explains this tactic as “Explore, don’t probe.” It is essential that while the participant is being interviewed they are being encouraged to explore their experiences in a manner that is sensitive and respectful. They should not be “probed” in such a way that makes them feel uncomfortable or like a specimen in lab. If too much time is spent dwelling on minute details or if too many follow-up questions are asked, it is possible that the participant will become defensive or unwilling to share. Thus, it is the interviewer’s job to strike a balance between ambiguity and specificity in their questions.

Conducting Your Interview : Be respectful and practice active listening to get the most out of your interview time.

Avoid Leading Questions

Leading questions are questions that suggest or imply a particular answer. While they are often asked innocently, they risk of altering the validity of the responses obtained as they discourage participants from using their own language to express their sentiments. It is instead preferable that interviewers ask open-ended questions. For example, instead of asking “Did the experience make you feel sad?”, it would be better to ask “How did the experience make you feel?” which suggests no particular feeling.

Don’t Interrupt

Participants should feel comfortable and respected throughout the entire interview—thus interviewers should avoid interrupting participants whenever possible. While participants may digress in their responses and while the interviewer may lose interest in what they are saying at one point or another it is critical that they be tactful in their efforts to keep the participant on track and to return to the subject matter in question.

Interview Followup

Content analysis is an essential part of the follow-up, in order to summarize who said what and when .

Explain how the different interview methods influence content analysis during follow-up

- If you have interviewed synchronously one or two experts in person, telephone, or video conference, then you should listen to the recording of the interview and mark points of interest.

- If you have conducted an online synchronous interview using chat, make sure that you have actually activated the archive feature so that you have a recorded transcript of the chat and are able to review each of the questions and responses at a later time.

- If you conducted an online asynchronous interview, you may have a large sample of geographically dispersed respondents. You will need to summarize the content or tabulate the ratings if you used rating scales for the interview questions.

- Once you have completed your content analysis, you will want to consider how to cite or credit the source(s) of the “personal communication” in order to indicate the person, the date, and the type of interview or manner of data collection.

- content analysis : A methodology in the social sciences for studying the content of communication. Harold Lasswell formulated the core questions of content analysis: “Who says what, to whom, why, to what extent and with what effect? “

Content Analysis is Essential Follow-up

Content analysis is an essential part of the follow-up to any type of interview. You want to summarize or describe the responses and associate them with the source or group of sources, who were the sample of people who responded. You want to summarize who said what , and when . If have engaged in a one-on-one in-person interview, the you will want to use your best informational listening and note-taking skills to capture the content of what was said. If you used an online synchronous or asynchronous interview method, you will already have a transcript or archive of the content, but will need to reliably summarize the responses to your interview questions. The different methods of interviewing will require different methods of follow-up to capture the content and prepare it for use.

In-person Interview

If you have interviewed synchronously one or two experts in person, telephone, or video conference, then you will want to listen to the recording of the interview and mark points of interest. You can either take notes, transcribe relevant answers, or mark with a time stamp the location of important content that relates to your topic for replay or review later.

In-person Interview : Record the interview for playback and analysis.

Online Synchronous Interview

Online synchronous interviews use simple text chat functions that can be recorded or archived for later analysis. If you have conducted an online synchronous interview using chat, make sure you have actually activated the archive feature so that you have a recorded transcript of the chat and are able to review each of the questions and responses at a later time. Since you can chat interview with a number of people about your topic, you may eventually want to summarize and analyze the data for patterns in the responses.

Online Asynchronous Interview

An asynchronous online interview is one where the researcher and the researched do not need to be online at the same time. Typically these interviews will use email, but other technologies might also be employed.

If you conducted an online interview asynchronously, you may have a large sample of geographically dispersed respondents. You will need to summarize the content or tabulate the ratings if you used rating scales for the interview questions.

If you asked closed questions, you can tabulate the frequency of responses in the different categories. However, if you asked more open-ended questions, you will find it useful to code the content of the interviews with some system so that you can group the responses into meaningful categories in order to summarize the results.

Citing the Interview

Once you have completed your content analysis, you will want to consider how to cite or credit the source(s) of the respondents. Since the results of your interview are usually not published, they will be considered “personal communication.” Generally, you will indicate the person, date, and manner of data collection. Here are some examples:

Personal Interview face to face—Expert, A. (2013, May 2) Personal Interview.

Personal interview by telephone or chat—Expert, A (2013, May 3) Telephone (chat) Interview.

Personal interview by email—Expert, A. ( 2013, May 4) Email Interview.

- Social Research Methods/Qualitative Research. Provided by : Wikibooks. Located at : http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Social_Research_Methods/Qualitative_Research . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Interviewing. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interviewing . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- interview. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/interview . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- talking point. Provided by : Wiktionary. Located at : http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/talking_point . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- IMG_1991 | Flickr - Photo Sharing!. Provided by : Flickr. Located at : http://www.flickr.com/photos/usfbps/4607149956/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Interview (research). Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interview_(research) . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Social Research Methods/Qualitative Research. Provided by : Wikibooks. Located at : http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Social_Research_Methods/Qualitative_Research%23Qualitative_Research . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Social Research Methods/Surveys. Provided by : Wikibooks. Located at : http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Social_Research_Methods/Surveys . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Dunedin ICT Internship Speed Dating 2010 | Flickr - Photo Sharing!. Provided by : Flickr. Located at : http://www.flickr.com/photos/21218849@N03/5016229588/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Qualitative data analysis. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qualitative_data_analysis%23Data_analysis . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Professional and Technical Writing/Documenting Your Sources/APA Style Reference Lists. Provided by : Wikibooks. Located at : http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Professional_and_Technical_Writing/Documenting_Your_Sources/APA_Style_Reference_Lists . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Content analysis. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Content_analysis . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Online interview. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Online_interview . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Interview jimbo. Provided by : Wikimedia. Located at : http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Interview_jimbo.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.2 Researching and Supporting Your Speech

Learning objectives.

- Identify appropriate methods for conducting college-level research.

- Distinguish among various types of sources.

- Evaluate the credibility of sources.

- Identify various types of supporting material.

- Employ visual aids that enhance a speaker’s message.

We live in an age where access to information is more convenient than ever before. The days of photocopying journal articles in the stacks of the library or looking up newspaper articles on microfilm are over for most. Yet, even though we have all this information at our fingertips, research skills are more important than ever. Our challenge now is not accessing information but discerning what information is credible and relevant. Even though it may sound inconvenient to have to physically go to the library, students who did research before the digital revolution did not have to worry as much about discerning. If you found a source in the library, you could be assured of its credibility because a librarian had subscribed to or purchased that content. When you use Internet resources like Google or Wikipedia, you have no guarantees about some of the content that comes up.

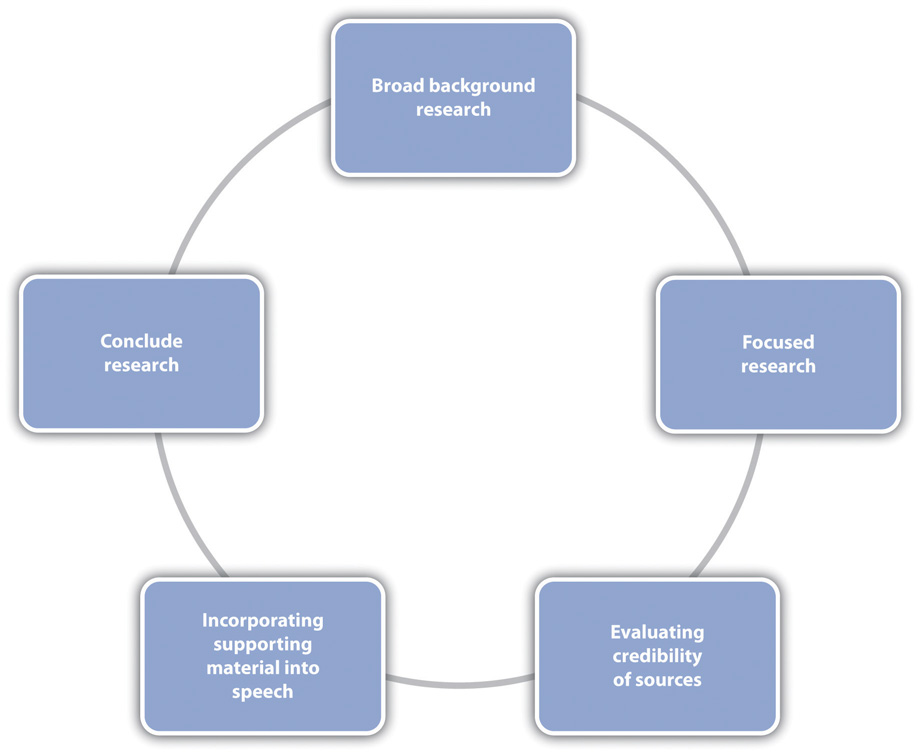

Finding Supporting Material

As was noted in Section 9.1 “Selecting and Narrowing a Topic” , it’s good to speak about something you are already familiar with. So existing knowledge forms the first step of your research process. Depending on how familiar you are with a topic, you will need to do more or less background research before you actually start incorporating sources to support your speech. Background research is just a review of summaries available for your topic that helps refresh or create your knowledge about the subject. It is not the more focused and academic research that you will actually use to support and verbally cite in your speech. Figure 9.3 “Research Process” illustrates the research process. Note that you may go through some of these steps more than once.

Figure 9.3 Research Process

I will reiterate several times in this chapter that your first step for research in college should be library resources, not Google or Bing or other general search engines. In most cases, you can still do your library research from the comfort of a computer, which makes it as accessible as Google but gives you much better results. Excellent and underutilized resources at college and university libraries are reference librarians. Reference librarians are not like the people who likely staffed your high school library. They are information-retrieval experts. At most colleges and universities, you can find a reference librarian who has at least a master’s degree in library and information sciences, and at some larger or specialized schools, reference librarians have doctoral degrees. I liken research to a maze, and reference librarians can help you navigate the maze. There may be dead ends, but there’s always another way around to reach the end goal. Unfortunately, many students hit their first dead end and give up or assume that there’s not enough research out there to support their speech. Trust me, if you’ve thought of a topic to do your speech on, someone else has thought of it, too, and people have written and published about it. Reference librarians can help you find that information. I recommend that you meet with a reference librarian face-to-face and take your assignment sheet and topic idea with you. In most cases, students report that they came away with more information than they needed, which is good because you can then narrow that down to the best information. If you can’t meet with a reference librarian face-to-face, many schools now offer the option to do a live chat with a reference librarian, and you can also contact them by e-mail or phone.

College and university libraries are often at the cutting edge of information retrieval for academic research.

Andre Vandal – The Morrin College Library – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Aside from the human resources available in the library, you can also use electronic resources such as library databases. Library databases help you access more credible and scholarly information than what you will find using general Internet searches. These databases are quite expensive, and you can’t access them as a regular citizen without paying for them. Luckily, some of your tuition dollars go to pay for subscriptions to these databases that you can then access as a student. Through these databases, you can access newspapers, magazines, journals, and books from around the world. Of course, libraries also house stores of physical resources like DVDs, books, academic journals, newspapers, and popular magazines. You can usually browse your library’s physical collection through an online catalog search. A trip to the library to browse is especially useful for books. Since most university libraries use the Library of Congress classification system, books are organized by topic. That means if you find a good book using the online catalog and go to the library to get it, you should take a moment to look around that book, because the other books in that area will be topically related. On many occasions, I have used this tip and gone to the library for one book but left with several.

Although Google is not usually the best first stop for conducting college-level research, Google Scholar is a separate search engine that narrows results down to scholarly materials. This version of Google has improved much over the past few years and has served as a good resource for my research, even for this book. A strength of Google Scholar is that you can easily search for and find articles that aren’t confined to a particular library database. Basically, the pool of resources you are searching is much larger than what you would have using a library database. The challenge is that you have no way of knowing if the articles that come up are available to you in full-text format. As noted earlier, most academic journal articles are found in databases that require users to pay subscription fees. So you are often only able to access the abstracts of articles or excerpts from books that come up in a Google Scholar search. You can use that information to check your library to see if the article is available in full-text format, but if it isn’t, you have to go back to the search results. When you access Google Scholar on a campus network that subscribes to academic databases, however, you can sometimes click through directly to full-text articles. Although this resource is still being improved, it may be a useful alternative or backup when other search strategies are leading to dead ends.

Types of Sources

There are several different types of sources that may be relevant for your speech topic. Those include periodicals, newspapers, books, reference tools, interviews, and websites. It is important that you know how to evaluate the credibility of each type of source material.

Periodicals

Periodicals include magazines and journals, as they are published periodically. There are many library databases that can access periodicals from around the world and from years past. A common database is Academic Search Premiere (a similar version is Academic Search Complete). Many databases, like this one, allow you to narrow your search terms, which can be very helpful as you try to find good sources that are relevant to your topic. You may start by typing a key word into the first box and searching. Sometimes a general search like this can yield thousands of results, which you obviously wouldn’t have time to look through. In this case you may limit your search to results that have your keyword in the abstract , which is the author-supplied summary of the source. If there are still too many results, you may limit your search to results that have your keyword in the title. At this point, you may have reduced those ten thousand results down to a handful, which is much more manageable.

Within your search results, you will need to distinguish between magazines and academic journals. In general, academic journals are considered more scholarly and credible than magazines because most of the content in them is peer reviewed. The peer-review process is the most rigorous form of review, which takes several months to years and ensures that the information that is published has been vetted and approved by numerous experts on the subject. Academic journals are usually affiliated with professional organizations rather than for-profit corporations, and neither authors nor editors are paid for their contributions. For example, the Quarterly Journal of Speech is one of the oldest journals in communication studies and is published by the National Communication Association.

The National Communication Association publishes several peer-reviewed academic journals.

The National Communication Association’s office in Washington D.C., courtesy of Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0.

If your instructor wants you to have sources from academic journals, you can often click a box to limit your search results to those that are “peer reviewed.” There are also subject-specific databases you can use to find periodicals. For example, Communication and Mass Media Complete is a database that includes articles from hundreds of journals related to communication studies. It may be acceptable for you to include magazine sources in your speech, but you should still consider the credibility of the source. Magazines like Scientific American and Time are generally more credible and reliable than sources like People or Entertainment Weekly .

Newspapers and Books

Newspapers and books can be excellent sources but must still be evaluated for relevance and credibility. Newspapers are good for topics that are developing quickly, as they are updated daily. While there are well-known newspapers of record like the New York Times , smaller local papers can also be credible and relevant if your speech topic doesn’t have national or international reach. You can access local, national, and international newspapers through electronic databases like LexisNexis. If a search result comes up that doesn’t have a byline with an author’s name or an organization like the Associated Press or Reuters cited, then it might be an editorial. Editorials may also have bylines, which make them look like traditional newspaper articles even though they are opinion based. It is important to distinguish between news articles and editorials because editorials are usually not objective and do not go through the same review process that a news story does before it’s published. It’s also important to know the background of your paper. Some newspapers are more tabloid focused or may be published by a specific interest group that has an agenda and biases. So it’s usually better to go with a newspaper that is recognized as the newspaper of record for a particular area.

Books are good for a variety of subjects and are useful for in-depth research that you can’t get as regularly from newspapers or magazines. Edited books with multiple chapters by different authors can be especially good to get a variety of perspectives on a topic.

Don’t assume that you can’t find a book relevant to a topic that is fairly recent, since books may be published within a year of a major event.

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY 2.0.

To evaluate the credibility of a book, you’ll want to know some things about the author. You can usually find this information at the front or back of the book. If an author is a credentialed and recognized expert in his or her area, the book will be more credible. But just because someone wrote a book on a subject doesn’t mean he or she is the most credible source. For example, a quick search online brings up many books related to public speaking that are written by people who have no formal training in communication or speech. While they may have public speaking experience that can help them get a book deal with a certain publisher, that alone wouldn’t qualify them to write a textbook, as textbook authors are expected to be credentialed experts—that is, people with experience and advanced training/degrees in their area. The publisher of a book can also be an indicator of credibility. Books published by university/academic presses (University of Chicago Press, Duke University Press) are considered more credible than books published by trade presses (Penguin, Random House), because they are often peer reviewed and they are not primarily profit driven.

Reference Tools

The transition to college-level research means turning more toward primary sources and away from general reference materials. Primary sources are written by people with firsthand experiences with an event or researchers/scholars who conducted original research. Unfortunately, many college students are reluctant to give up their reliance on reference tools like dictionaries and encyclopedias. While reference tools like dictionaries and encyclopedias are excellent for providing a speaker with a background on a topic, they should not be the foundation of your research unless they are academic and/or specialized.

Dictionaries are handy tools when we aren’t familiar with a particular word. However, citing a dictionary like Webster’s as a source in your speech is often unnecessary. I tell my students that Webster’s Dictionary is useful when you need to challenge a Scrabble word, but it isn’t the best source for college-level research. You will inevitably come upon a word that you don’t know while doing research. Most good authors define the terms they use within the content of their writing. In that case, it’s better to use the author’s definition than a dictionary definition. Also, citing a dictionary doesn’t show deep research skills; it only shows an understanding of alphabetical order. So ideally you would quote or paraphrase the author’s definition rather than turning to a general dictionary like Webster’s . If you must turn to a dictionary, I recommend an academic dictionary like The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) , which is the most comprehensive dictionary in the English language, with more than twenty volumes. You can’t access the OED for free online, but most libraries pay for a subscription that you can access as a student or patron. While the OED is an academic dictionary, it is not specialized, and you may need a specialized dictionary when dealing with very specific or technical terms. The Dictionary of Business and Economics is an example of an academic and specialized dictionary.

Many students have relied on encyclopedias for research in high school, but most encyclopedias, like World Book , Encarta , or Britannica , are not primary sources. Instead, they are examples of secondary sources that aggregate, or compile, research done by others in a condensed summary. As I noted earlier, reference sources like encyclopedias are excellent resources to get you informed about the basics of a topic, but at the college level, primary sources are expected. Many encyclopedias are Internet based, which makes them convenient, but they are still not primary sources, and their credibility should be even more scrutinized.

Wikipedia’s open format also means it doesn’t generally meet the expectations for credible, scholarly research.

Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0.

Wikipedia revolutionized how many people retrieve information and pioneered an open-publishing format that allowed a community of people to post, edit, and debate content. While this is an important contribution to society, Wikipedia is not considered a scholarly or credible source. Like other encyclopedias, Wikipedia should not be used in college-level research, because it is not a primary source. In addition, since its content can be posted and edited by anyone, we cannot be sure of the credibility of the content. Even though there are self-appointed “experts” who monitor and edit some of the information on Wikipedia, we cannot verify their credentials or the review process that information goes through before it’s posted. I’m not one of the college professors who completely dismisses Wikipedia, however. Wikipedia can be a great source for personal research, developing news stories, or trivia. Sometimes you can access primary sources through Wikipedia if you review the footnote citations included in an entry. Moving beyond Wikipedia, as with dictionaries, there are some encyclopedias that are better suited for college research. The Encyclopedia of Black America and the Encyclopedia of Disaster Relief are examples of specialized academic reference sources that will often include, in each entry, an author’s name and credentials and more primary source information.

When conducting an interview for a speech, you should access a person who has expertise in or direct experience with your speech topic. If you follow the suggestions for choosing a topic that were mentioned earlier, you may already know something about your speech topic and may have connections to people who would be good interview subjects. Previous employers, internship supervisors, teachers, community leaders, or even relatives may be appropriate interviewees, given your topic. If you do not have a connection to someone you can interview, you can often find someone via the Internet who would be willing to answer some questions. Many informative and persuasive speech topics relate to current issues, and most current issues have organizations that represent their needs. For an informative speech on ageism or a persuasive speech on lowering the voting age, a quick Internet search for “youth rights” leads you to the webpage for the National Youth Rights Association. Like most organization web pages, you can click on the “Contact Us” link to get information for leaders in the organization. You could also connect to members of the group through Facebook and interview young people who are active in the organization.

Once you have identified a good interviewee, you will want to begin researching and preparing your questions. Open-ended questions cannot be answered with a “yes” or “no” and can provide descriptions and details that will add to your speech. Quotes and paraphrases from your interview can add a personal side to a topic or at least convey potentially complicated information in a more conversational and interpersonal way.

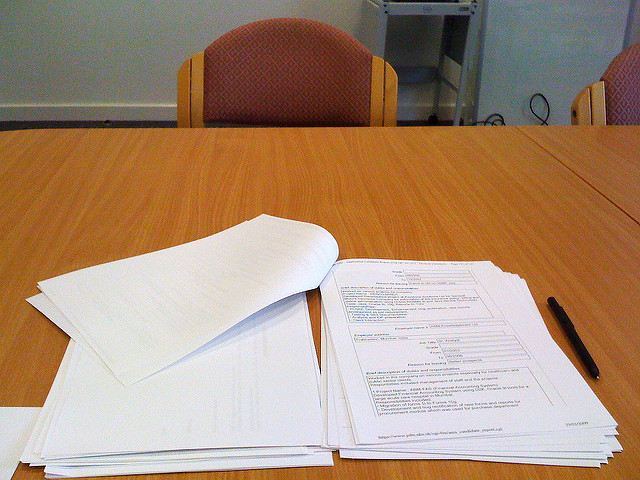

Even if you record an interview, take some handwritten notes and make regular eye contact with the interviewee to show that you are paying attention.

David Davies – Interviews – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Closed questions can be answered with one or two words and can provide a starting point to get to more detailed information if the interviewer has prepared follow-up questions. Unless the guidelines or occasion for your speech suggest otherwise, you should balance your interview data with the other sources in your speech. Don’t let your references to the interview take over your speech.

Tips for Conducting Interviews

- Do preliminary research to answer basic questions. Many people and organizations have information available publicly. Don’t waste interview time asking questions like “What year did your organization start?” when you can find that on the website.

- Plan questions ahead of time. Even if you know the person, treat it as a formal interview so you can be efficient.

- Ask open-ended questions that can’t be answered with only a yes or no. Questions that begin with how and why are generally more open-ended than do and did questions. Make sure you have follow-up questions ready.

- Use the interview to ask for the personal side of an issue that you may not be able to find in other resources. Personal narratives about experiences can resonate with an audience.

- Make sure you are prepared. If interviewing in person, have paper, pens, and a recording device if you’re using one. Test your recording device ahead of time. If interviewing over the phone, make sure you have good service so you don’t drop the call and that you have enough battery power on your phone. When interviewing on the phone or via video chat, make sure distractions (e.g., barking dogs) are minimized.

- Whether the interview is conducted face-to-face, over the phone, or via video (e.g., Skype), you must get permission to record. Recording can be useful, as it increases accuracy and the level of detail taken away from the interview. Most smartphones have free apps now that allow you to record face-to-face or phone conversations.

- Whether you record or not, take written notes during the interview. Aside from writing the interviewee’s responses, you can also take note of follow-up questions that come to mind or notes on the nonverbal communication of the interviewee.

- Mention ahead of time if you think you’ll have follow-up questions, so the interviewee can expect further contact.

- Reflect and expand on your notes soon after the interview. It’s impossible to transcribe everything during the interview, but you will remember much of what you didn’t have time to write down and can add it in.

- Follow up with a thank-you note. People are busy, and thanking them for their time and the information they provided will be appreciated.

We already know that utilizing library resources can help you automatically filter out content that may not be scholarly or credible, since the content in research databases is selected and restricted. However, some information may be better retrieved from websites. Even though both research databases and websites are electronic sources, there are two key differences between them that may impact their credibility. First, most of the content in research databases is or was printed but has been converted to digital formats for easier and broader access. In contrast, most of the content on websites has not been printed. Although not always the case, an exception to this is documents in PDF form found on web pages. You may want to do additional research or consult with your instructor to determine if that can count as a printed source. Second, most of the content on research databases has gone through editorial review, which means a professional editor or a peer editor has reviewed the material to make sure it is credible and worthy of publication. Most content on websites is not subjected to the same review process, as just about anyone with Internet access can self-publish information on a personal website, blog, wiki, or social media page. So what sort of information may be better retrieved from websites, and how can we evaluate the credibility of a website?

Most well-known organizations have official websites where they publish information related to their mission. If you know there is an organization related to your topic, you may want to see if they have an official website. It is almost always better to get information from an official website, because it is then more likely to be considered primary source information. Keep in mind, though, that organizations may have a bias or a political agenda that affects the information they put out. If you do get information from an official website, make sure to include that in your verbal citation to help establish your credibility. Official reports are also often best found on websites, as they rarely appear in their full form in periodicals, books, or newspapers. Government agencies, nonprofits, and other public service organizations often compose detailed and credible reports on a wide variety of topics.

The US Census Bureau’s official website is a great place to find current and credible statistics related to population numbers and demographic statistics.

U.S. Census Bureau – public domain.

A key way to evaluate the credibility of a website is to determine the site’s accountability. By accountability, I mean determining who is ultimately responsible for the content put out and whose interests the content meets. The more information that is included on a website, the better able you will be to determine its accountability. Ideally all or most of the following information would be included: organization/agency name, author’s name and contact information, date the information was posted or published, name and contact information for person in charge of web content (i.e., web editor or webmaster), and a link to information about the organization/agency/business mission. While all this information doesn’t have to be present to warrant the use of the material, the less accountability information is available, the more you should scrutinize the information. You can also begin to judge the credibility of a website by its domain name. Some common domain names are .com , .net , .org , .edu , .mil , and .gov . For each type of domain, there are questions you may ask that will help you evaluate the site’s credibility. You can see a summary of these questions in Table 9.2 “Website Domain Names and Credibility” . Note that some domain names are marked as “restricted” and others aren’t. When a domain is restricted, .mil for example, a person or group wanting to register that domain name has to prove that their content is appropriate for the guidelines of the domain name. Essentially, this limits access to the information published on those domain names, which increases the overall credibility.

Table 9.2 Website Domain Names and Credibility

Types of Supporting Material

There are several types of supporting material that you can pull from the sources you find during the research process to add to your speech. They include examples, explanations, statistics, analogies, testimony, and visual aids. You will want to have a balance of information, and you will want to include the material that is most relevant to your audience and is most likely to engage them. When determining relevance, utilize some of the strategies mentioned in Section 9.1 “Selecting and Narrowing a Topic” . Thinking about who your audience is and what they know and would like to know will help you tailor your information. Also try to incorporate proxemic information , meaning information that is geographically relevant to your audience. For example, if delivering a speech about prison reform to an audience made up of Californians, citing statistics from North Carolina prisons would not be as proxemic as citing information from California prisons. The closer you can get the information to the audience, the better. I tell my students to make the information so relevant and proxemic that it is in our backyards, in the car with us on the way to school or work, and in the bed with us while we sleep.

An example is a cited case that is representative of a larger whole. Examples are especially beneficial when presenting information that an audience may not be familiar with. They are also useful for repackaging or reviewing information that has already been presented. Examples can be used in many different ways, so you should let your audience, purpose and thesis, and research materials guide your use. You may pull examples directly from your research materials, making sure to cite the source. The following is an example used in a speech about the negative effects of standardized testing: “Standardized testing makes many students anxious, and even ill. On March 14, 2002, the Sacramento Bee reported that some standardized tests now come with instructions indicating what teachers should do with a test booklet if a student throws up on it.” You may also cite examples from your personal experience, if appropriate: “I remember being sick to my stomach while waiting for my SAT to begin.”

You may also use hypothetical examples, which can be useful when you need to provide an example that is extraordinary or goes beyond most people’s direct experience. Capitalize on this opportunity by incorporating vivid description into the example that appeals to the audience’s senses. Always make sure to indicate when you are using a hypothetical example, as it would be unethical to present an example as real when it is not. Including the word imagine or something similar in the first sentence of the example can easily do this.

Whether real or hypothetical, examples used as supporting material can be brief or extended. Brief examples are usually one or two sentences, as you can see in the following hypothetical example: “Imagine that your child, little sister, or nephew has earned good grades for the past few years of elementary school, loves art class, and also plays on the soccer team. You hear the unmistakable sounds of crying when he or she comes home from school and you find out that art and soccer have been eliminated because students did not meet the federal guidelines for performance on standardized tests.” Brief examples are useful when the audience is already familiar with a concept or during a review. Extended examples, sometimes called illustrations, are several sentences long and can be effective in introductions or conclusions to get the audience’s attention or leave a lasting impression. It is important to think about relevance and time limits when considering using an extended illustration. Since most speeches are given within time constraints, you want to make sure the extended illustration is relevant to your speech purpose and thesis and that it doesn’t take up a disproportionate amount of the speech. If a brief example or series of brief examples would convey the same content and create the same tone as the extended example, I suggest you go with brevity.

Explanations

Explanations clarify ideas by providing information about what something is, why something is the way it is, or how something works or came to be. One of the most common types of explanation is a definition. Definitions do not have to come from the dictionary. Many times, authors will define concepts as they use them in their writing, which is a good alternative to a dictionary definition.

Since quoting a dictionary definition during a speech is difficult, it’s better to put a definition into your own words based on how it is defined in the original source in which it appeared.

Julian Bucknall – Dictionaries – CC BY-NC 2.0.

As you do your research, think about how much your audience likely knows about a given subject. You do not need to provide definitions when information is common knowledge. Anticipate audience confusion and define legal, medical, or other forms of jargon as well as slang and foreign words. Definitions like the following are also useful for words that we are familiar with but may not know specifics: “According to the 2011 book Prohibition: 13 Years That Changed America , what we now know as Prohibition started in 1920 with the passage of the Volstead Act and the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment.” Keep in mind that repeating a definition verbatim from a dictionary often leads to fluency hiccups, because definitions are not written to be read aloud. It’s a good idea to put the definition into your own words (still remembering to cite the original source) to make it easier for you to deliver.

Other explanations focus on the “why” and “how” of a concept. Continuing to inform about Prohibition, a speaker could explain why the movement toward Prohibition began: “The Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution gained support because of the strong political influence of the Anti-Saloon League.” The speaker could go on to explain how the Constitution is amended: “According to the same book, a proposed amendment to the Constitution needs three-fourths of all the states to approve it in order to be ratified.” We use explanations as verbal clarifications to support our claims in daily conversations, perhaps without even noticing it. Consciously incorporating clear explanations into your speech can help you achieve your speech goals.

Statistics are numerical representations of information. They are very credible in our society, as evidenced by their frequent use by news agencies, government offices, politicians, and academics. As a speaker, you can capitalize on the power of statistics if you use them appropriately. Unfortunately, statistics are often misused by speakers who intentionally or unintentionally misconstrue the numbers to support their argument without examining the context from which the statistic emerged. All statistics are contextual, so plucking a number out of a news article or a research study and including it in your speech without taking the time to understand the statistic is unethical.

Although statistics are popular as supporting evidence, they can also be boring. There will inevitably be people in your audience who are not good at processing numbers. Even people who are good with numbers have difficulty processing through a series of statistics presented orally. Remember that we have to adapt our information to listeners who don’t have the luxury of pressing a pause or rewind button. For these reasons, it’s a good idea to avoid using too many statistics and to use startling examples when you do use them. Startling statistics should defy our expectations. When you give the audience a large number that they would expect to be smaller, or vice versa, you will be more likely to engage them, as the following example shows: “Did you know that 1.3 billion people in the world do not have access to electricity? That’s about 20 percent of the world’s population according to a 2009 study on the International Energy Agency’s official website.”

You should also repeat key statistics at least once for emphasis. In the previous example, the first time we hear the statistic 1.3 billion, we don’t have any context for the number. Translating that number into a percentage in the next sentence repeats the key statistic, which the audience now has context for, and repackages the information into a percentage, which some people may better understand. You should also round long numbers up or down to make them easier to speak. Make sure that rounding the number doesn’t distort its significance. Rounding 1,298,791,943 to 1.3 billion, for example, makes the statistic more manageable and doesn’t alter the basic meaning. It is also beneficial to translate numbers into something more concrete for visual or experiential learners by saying, for example, “That’s equal to the population of four Unites States of Americas.” While it may seem easy to throw some numbers in your speech to add to your credibility, it takes more work to make them impactful, memorable, and effective.

Tips for Using Statistics

- Make sure you understand the context from which a statistic emerges.

- Don’t overuse statistics.

- Use startling statistics that defy the audience’s expectations.

- Repeat key statistics at least once for emphasis.

- Use a variety of numerical representations (whole numbers, percentages, ratios) to convey information.

- Round long numbers to make them easier to speak.

- Translate numbers into concrete ideas for more impact.

Analogies involve a comparison of ideas, items, or circumstances. When you compare two things that actually exist, you are using a literal analogy—for example, “Germany and Sweden are both European countries that have had nationalized health care for decades.” Another type of literal comparison is a historical analogy. In Mary Fisher’s now famous 1992 speech to the Republican National Convention, she compared the silence of many US political leaders regarding the HIV/AIDS crisis to that of many European leaders in the years before the Holocaust.

My father has devoted much of his lifetime to guarding against another holocaust. He is part of the generation who heard Pastor Niemöller come out of the Nazi death camps to say, “They came after the Jews and I was not a Jew, so I did not protest. They came after the Trade Unionists, and I was not a Trade Unionist, so I did not protest. They came after the Roman Catholics, and I was not a Roman Catholic, so I did not protest. Then they came after me, and there was no one left to protest.” The lesson history teaches is this: If you believe you are safe, you are at risk.

A figurative analogy compares things that are not normally related, often relying on metaphor, simile, or other figurative language devices. In the following example, wind and revolution are compared: “Just as the wind brings changes in the weather, so does revolution bring change to countries.”

When you compare differences, you are highlighting contrast—for example, “Although the United States is often thought of as the most medically advanced country in the world, other Western countries with nationalized health care have lower infant mortality rates and higher life expectancies.” To use analogies effectively and ethically, you must choose ideas, items, or circumstances to compare that are similar enough to warrant the analogy. The more similar the two things you’re comparing, the stronger your support. If an entire speech on nationalized health care was based on comparing the United States and Sweden, then the analogy isn’t too strong, since Sweden has approximately the same population as the state of North Carolina. Using the analogy without noting this large difference would be misrepresenting your supporting material. You could disclose the discrepancy and use other forms of supporting evidence to show that despite the population difference the two countries are similar in other areas to strengthen your speech.

Testimony is quoted information from people with direct knowledge about a subject or situation. Expert testimony is from people who are credentialed or recognized experts in a given subject. Lay testimony is often a recounting of a person’s experiences, which is more subjective. Both types of testimony are valuable as supporting material. We can see this in the testimonies of people in courtrooms and other types of hearings. Lawyers know that juries want to hear testimony from experts, eyewitnesses, and friends and family. Congressional hearings are similar.

Congressional hearings often draw on expert and lay testimony to provide a detailed understanding of an event or issue.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

When Toyota cars were malfunctioning and being recalled in 2010, mechanics and engineers were called to testify about the technical specifications of the car (expert testimony), and car drivers like the soccer mom who recounted the brakes on her Prius suddenly failing while she was driving her kids to practice were also called (lay testimony). When using testimony, make sure you indicate whether it is expert or lay by sharing with the audience the context of the quote. Share the credentials of experts (education background, job title, years of experience, etc.) to add to your credibility or give some personal context for the lay testimony (eyewitness, personal knowledge, etc.).

“Getting Competent”

Choosing the Right Supporting Material

As you sift through your research materials to find supporting material to incorporate into your speech, you will want to include a variety of information types. Choosing supporting material that is relevant to your audience will help make your speech more engaging. As was noted earlier, a speaker should consider the audience throughout the speech-making process. Imagine you were asked to deliver a speech about your college or university. To get some practice adapting supporting material to various audiences, provide an example of each type of supporting material that is tailored to the following specific audiences. Include an example, an explanation, a statistic, an analogy, some testimony, and a visual aid.

- Incoming first-year students

- Parents of incoming first-year students

- Alumni of the college or university

- Community members that live close to the school

Visual Aids

Visual aids help a speaker reinforce speech content visually, which helps amplify the speaker’s message. They can be used to present any of the types of supporting materials discussed previously. Speakers rely heavily on an audience’s ability to learn by listening, which may not always be successful if audience members are visual or experiential learners. Even if audience members are good listeners, information overload or external or internal noise can be barriers to a speaker achieving his or her speech goals. Therefore skillfully incorporating visual aids into a speech has many potential benefits:

- Helping your audience remember information because it is presented orally and visually

- Helping your audience understand information because it is made more digestible through diagrams, charts, and so on

- Helping your audience see something in action by demonstrating with an object, showing a video, and so on

- Engaging your audience by making your delivery more dynamic through demonstration, gesturing, and so on

There are several types of visual aids, and each has its strengths in terms of the type of information it lends itself to presenting. The types of visual aids we will discuss are objects; chalkboards, whiteboards, and flip charts; posters and handouts; pictures; diagrams; charts; graphs; videos; and presentation software. It’s important to remember that supporting materials presented on visual aids should be properly cited. We will discuss proper incorporation of supporting materials into a speech in Section 9.3 “Organizing” . While visual aids can help bring your supporting material to life, they can also add more opportunities for things to go wrong during your speech. Therefore we’ll discuss some tips for effective creation and delivery as we discuss the various types of visual aids.

Three-dimensional objects that represent an idea can be useful as a visual aid for a speech. They offer the audience a direct, concrete way to understand what you are saying. I often have my students do an introductory speech where they bring in three objects that represent their past, present, and future. Students have brought in a drawer from a chest that they were small enough to sleep in as a baby, a package of Ramen noodles to represent their life as a college student, and a stethoscope or other object to represent their career goals, among other things. Models also fall into this category, as they are scaled versions of objects that may be too big (the International Space Station) or too small (a molecule) to actually show to your audience.

Tips for Using Objects Effectively

- Make sure your objects are large enough for the audience to see.

- Do not pass objects around, as it will be distracting.

- Hold your objects up long enough for the audience to see them.

- Do not talk to your object, wiggle or wave it around, tap on it, or obstruct the audience’s view of your face with it.

- Practice with your objects so your delivery will be fluent and there won’t be any surprises.

Chalkboards, Whiteboards, and Flip Charts

Chalkboards, whiteboards, and flip charts can be useful for interactive speeches. If you are polling the audience or brainstorming you can write down audience responses easily for everyone to see and for later reference. They can also be helpful for unexpected clarification. If audience members look confused, you can take a moment to expand on a point or concept using the board or flip chart. Since many people are uncomfortable writing on these things due to handwriting or spelling issues, it’s good to anticipate things that you may have to expand on and have prepared extra visual aids or slides that you can include if needed. You can also have audience members write things on boards or flip charts themselves, which helps get them engaged and takes some of the pressure off you as a speaker.

Posters and Handouts

Posters generally include text and graphics and often summarize an entire presentation or select main points. Posters are frequently used to present original research, as they can be broken down into the various steps to show how a process worked. Posters can be useful if you are going to have audience members circulating around the room before or after your presentation, so they can take the time to review the poster and ask questions. Posters are not often good visual aids during a speech, because it’s difficult to make the text and graphics large enough for a room full of people to adequately see. The best posters are those created using computer software and professionally printed on large laminated paper.

Printing/copying businesses are now good at helping produce professional-looking posters. Although they can be costly, they add to the speaker’s credibility.