Essay on Art

500 words essay on art.

Each morning we see the sunshine outside and relax while some draw it to feel relaxed. Thus, you see that art is everywhere and anywhere if we look closely. In other words, everything in life is artwork. The essay on art will help us go through the importance of art and its meaning for a better understanding.

What is Art?

For as long as humanity has existed, art has been part of our lives. For many years, people have been creating and enjoying art. It expresses emotions or expression of life. It is one such creation that enables interpretation of any kind.

It is a skill that applies to music, painting, poetry, dance and more. Moreover, nature is no less than art. For instance, if nature creates something unique, it is also art. Artists use their artwork for passing along their feelings.

Thus, art and artists bring value to society and have been doing so throughout history. Art gives us an innovative way to view the world or society around us. Most important thing is that it lets us interpret it on our own individual experiences and associations.

Art is similar to live which has many definitions and examples. What is constant is that art is not perfect or does not revolve around perfection. It is something that continues growing and developing to express emotions, thoughts and human capacities.

Importance of Art

Art comes in many different forms which include audios, visuals and more. Audios comprise songs, music, poems and more whereas visuals include painting, photography, movies and more.

You will notice that we consume a lot of audio art in the form of music, songs and more. It is because they help us to relax our mind. Moreover, it also has the ability to change our mood and brighten it up.

After that, it also motivates us and strengthens our emotions. Poetries are audio arts that help the author express their feelings in writings. We also have music that requires musical instruments to create a piece of art.

Other than that, visual arts help artists communicate with the viewer. It also allows the viewer to interpret the art in their own way. Thus, it invokes a variety of emotions among us. Thus, you see how essential art is for humankind.

Without art, the world would be a dull place. Take the recent pandemic, for example, it was not the sports or news which kept us entertained but the artists. Their work of arts in the form of shows, songs, music and more added meaning to our boring lives.

Therefore, art adds happiness and colours to our lives and save us from the boring monotony of daily life.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Art

All in all, art is universal and can be found everywhere. It is not only for people who exercise work art but for those who consume it. If there were no art, we wouldn’t have been able to see the beauty in things. In other words, art helps us feel relaxed and forget about our problems.

FAQ of Essay on Art

Question 1: How can art help us?

Answer 1: Art can help us in a lot of ways. It can stimulate the release of dopamine in your bodies. This will in turn lower the feelings of depression and increase the feeling of confidence. Moreover, it makes us feel better about ourselves.

Question 2: What is the importance of art?

Answer 2: Art is essential as it covers all the developmental domains in child development. Moreover, it helps in physical development and enhancing gross and motor skills. For example, playing with dough can fine-tune your muscle control in your fingers.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Essays About Art: Top 5 Examples and 9 Prompts

Essays about art inspire beauty and creativity; see our top essay picks and prompts to aid you.

Art is an umbrella term for various activities that use human imagination and talents.

The products from these activities incite powerful feelings as artists convey their ideas, expertise, and experience through art. Examples of art include painting, sculpture, photography, literature, installations, dance, and music.

Art is also a significant part of human history. We learn a lot from the arts regarding what living in a period is like, what events influenced the elements in the artwork, and what led to art’s progress to today.

To help you create an excellent essay about art, we prepared five examples that you can look at:

1. Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? by Linda Nochlin

2. what is art by writer faith, 3. my art taught me… by christine nishiyama, 4. animals and art by ron padgett, 5. the value of art by anonymous on arthistoryproject.com, 1. art that i won’t forget, 2. unconventional arts, 3. art: past and present, 4. my life as an artist, 5. art histories of different cultures, 6. comparing two art pieces, 7. create a reflection essay on a work of art, 8. conduct a visual analysis of an artwork, 9. art period or artist history.

“But in actuality, as we all know, things as they are and as they have been, in the arts as in a hundred other areas, are stultifying, oppressive, and discouraging to all those, women among them, who did not have the good fortune to be born white, preferably middle class, and above all, male. The fault lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education–education understood to include everything that happens to us from the moment we enter this world…”

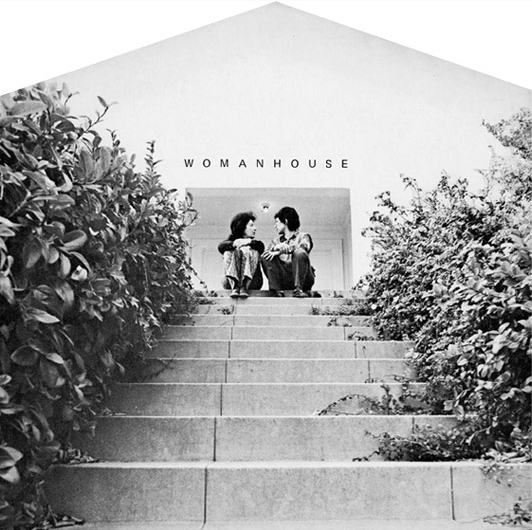

Nochlin goes in-depth to point out women’s part in art history. She focuses on unjust opportunities presented to women compared to their male peers, labeling it the “Woman Problem.” This problem demands a reinterpretation of the situation’s nature and the need for radical change. She persuades women to see themselves as equal subjects deserving of comparable achievements men receive.

Throughout her essay, she delves into the institutional barriers that prevented women from reaching the heights of famous male art icons.

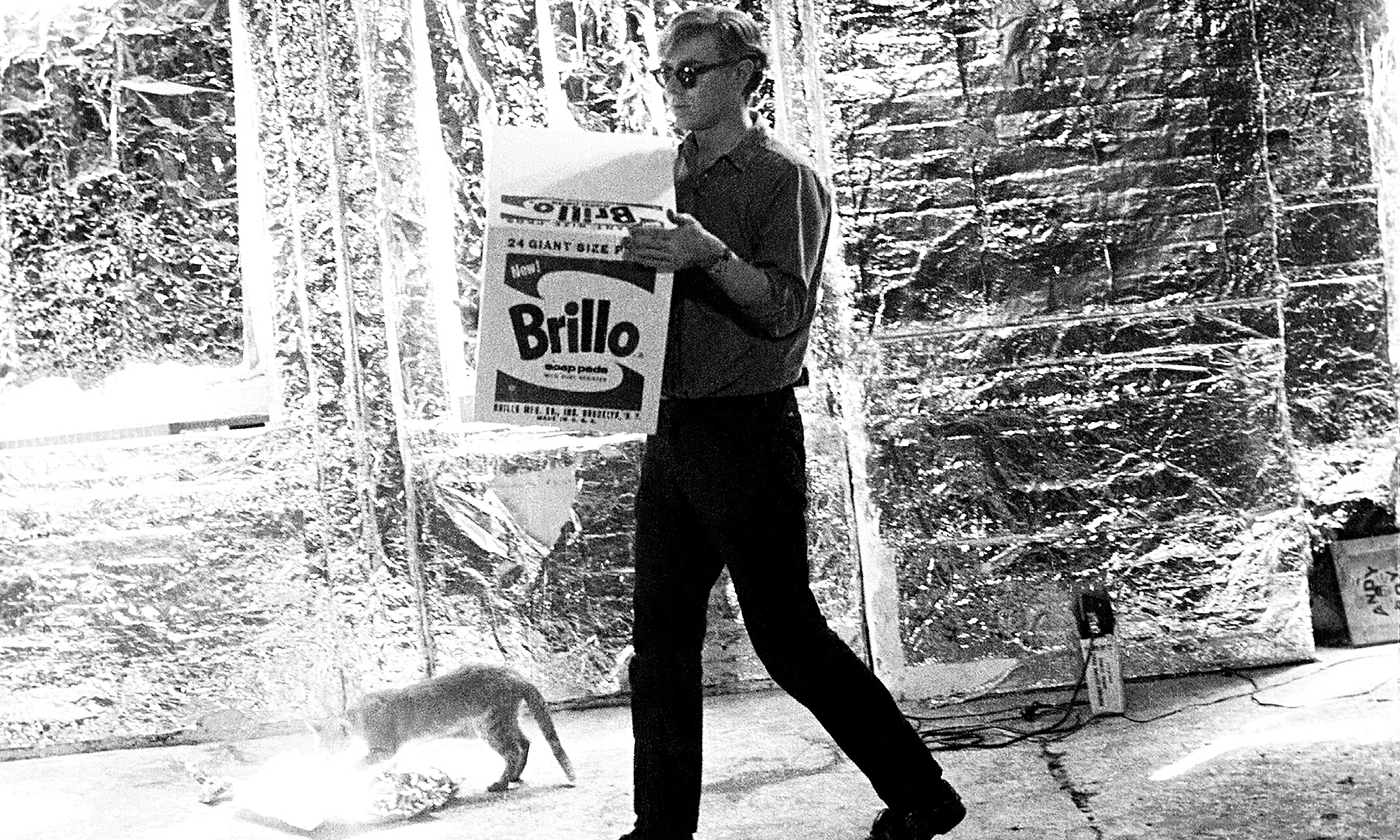

“Art is the use of skill and imagination in the creation of aesthetic objects that can be shared with others. It involves the arranging of elements in a way that appeals to the senses or emotions and acts as a means of communication with the viewer as it represents the thoughts of the artist.”

The author defines art as a medium to connect with others and an action. She focuses on Jamaican art and the feelings it invokes. She introduces Osmond Watson, whose philosophy includes uplifting the masses and making people aware of their beauty – he explains one of his works, “Peace and Love.”

“But I’ve felt this way before, especially with my art. And my experience with artmaking has taught me how to get through periods of struggle. My art has taught me to accept where I am today… My art has taught me that whatever marks I make on the page are good enough… My art has taught me that the way through struggle is to acknowledge, accept and share my struggle.”

Nishiyama starts her essay by describing how writing makes her feel. She feels pressured to create something “great” after her maternity leave, causing her to struggle. She says she pens essays to process her experiences as an artist and human, learning alongside the reader. She ends her piece by acknowledging her feelings and using her art to accept them.

“I was saying that sometimes I feel sorry for wild animals, out there in the dark, looking for something to eat while in fear of being eaten. And they have no ballet companies or art museums. Animals of course are not aware of their lack of cultural activities, and therefore do not regret their absence.”

Padgett recounts telling his wife how he thinks it’s unfortunate for animals not to have cultural activities, therefore, can’t appreciate art. He shares the genetic mapping of humans being 99% chimpanzees and is curious about the 1% that makes him human and lets him treasure art. His essay piques readers’ minds, making them interested in how art elevates human life through summoning admiration from lines and colors.

“One of the first questions raised when talking about art is simple — why should we care? Art, especially in the contemporary era, is easy to dismiss as a selfish pastime for people who have too much time on their hands. Creating art doesn’t cure disease, build roads, or feed the poor.”

Because art can easily be dismissed as a pastime, the author lists why it’s precious. It includes exercising creativity, materials used, historical connection, and religious value.

Check out our best essay checkers to ensure you have a top-notch essay.

9 Prompts on Essays About Art

After knowing more about art, below are easy prompts you can use for your art essay:

Is there an art piece that caught your attention because of its origin? First, talk about it and briefly summarize its backstory in your essay. Then, explain why it’s something that made an impact on you. For example, you can write about the Mona Lisa and her mysterious smile – or is she smiling? You can also put theories on what could have happened while Leonardo da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa.

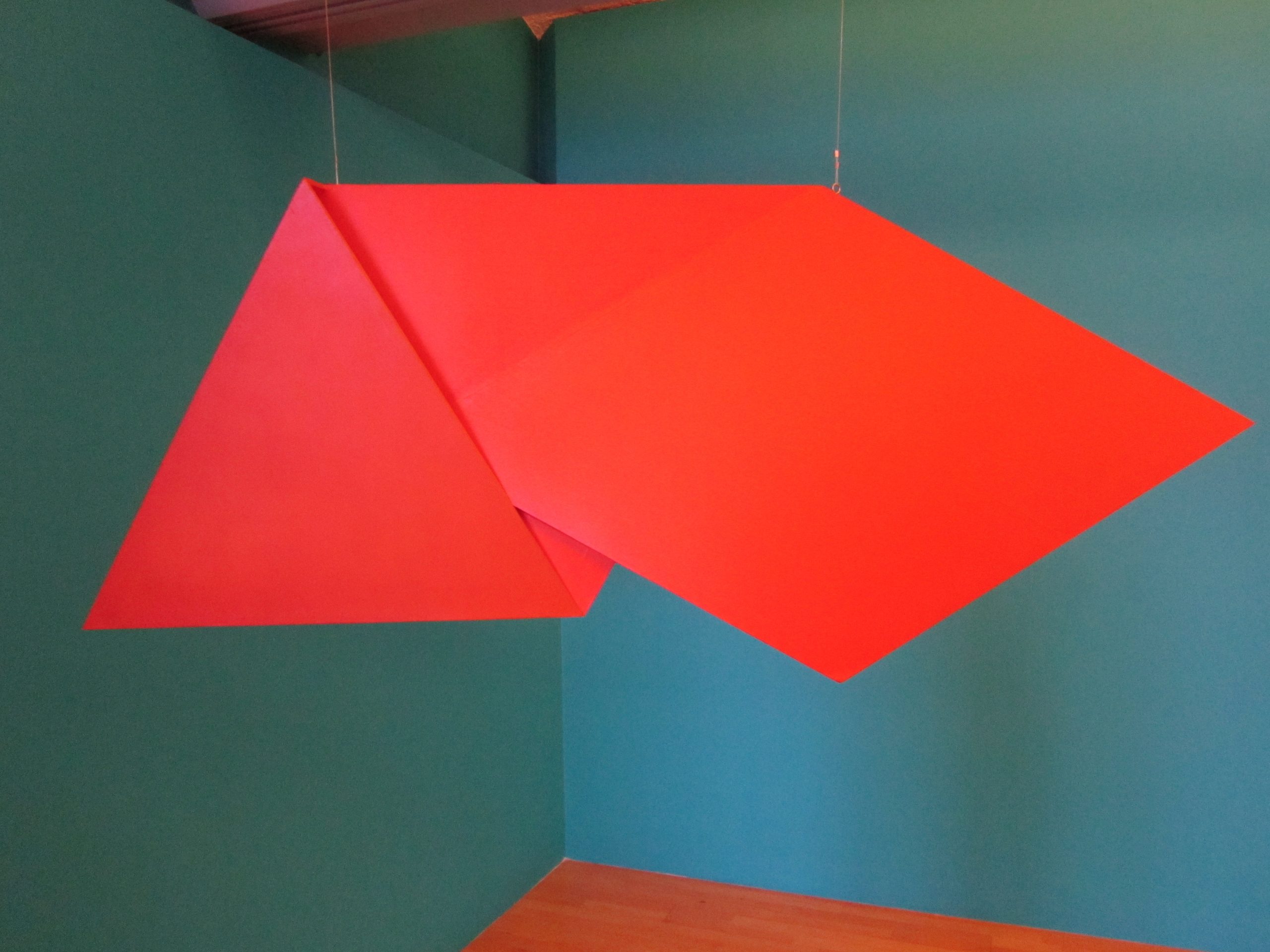

Rather than focusing on mainstream arts like ballet and painting, focus your essay on unconventional art or something that defies usual pieces, such as avant-garde art. Then, share what you think of this type of art and measure it against other mediums.

How did art change over the centuries? Explain the differences between ancient and modern art and include the factors that resulted in these changes.

Are you an artist? Share your creative process and objectives if you draw, sing, dance, etc. How do you plan to be better at your craft? What is your ultimate goal?

To do this prompt, pick two countries or cultures with contrasting art styles. A great example is Chinese versus European arts. Center your essay on a category, such as landscape paintings. Tell your readers the different elements these cultures consider. What is the basis of their art? What influences their art during that specific period?

Like the previous prompt, write an essay about similar pieces, such as books, folktales, or paintings. You can also compare original and remake versions of movies, broadway musicals, etc.

Pick a piece you want to know more about, then share what you learned through your essay. What did the art make you feel? If you followed creating art, like pottery, write about the step-by-step process, from clay to glazing.

Visual analysis is a way to understand art centered around what the eyes can process. It includes elements like texture, color, line, and scale. For this prompt, find a painting or statue and describe what you see in your essay.

Since art is a broad topic, you can narrow your research by choosing only the most significant moments in art history. For instance, if you pick English art, you can divide each art period by century or by a king’s ruling time. You can also select an artist and discuss their pieces, their art’s backstory, and how it relates to their life at the time.

If you are interested in learning more, check out our essay writing tips !

Maria Caballero is a freelance writer who has been writing since high school. She believes that to be a writer doesn't only refer to excellent syntax and semantics but also knowing how to weave words together to communicate to any reader effectively.

View all posts

Works of Art Essay

Introduction, basic facts about the works, personal philosophies of artists, artwork in time-context, comparison: form, content, and subject matter, aesthetic qualities and symbolic significance.

Pieces of artwork from different time periods portray varying styles. Several time periods had distinctive schools of thought. As a result, an artist who created a piece of work revealed a certain philosophical point of view. Aspects like positioning of key figures in an artwork tell of a particular style used to construct an image. Personal philosophies of artists rely upon the prevailing conditions of the time. It is imperative that the viewer makes some identities such as the visual appearance of the work.

Therefore, many works of art belonging to the same period are closely related to the context of the period. This essay has two main parts. The first part highlights more about the impressionism period’s paintings, basic facts about the works, the personal philosophies of the artists, and art work in time context. On the other hand, the second part compares the forms of art with respect to content, subject matter and form. It also compares and contrasts the symbolic significance, aesthetic attributes and the different perspectives from the artists.

The period chosen is Impressionism. Despite the differences in the paintings to be compared, all have got one description in common. Historically, impressionism as an art period dates back to 1874. These artworks have a unique way from their ability to create brilliant and rosy images. Usually, paintings from the impressionism depicted nature. Light and shadows are blended to create softened outlines. The viewer gets an impression of the sun illuminating the canvas (Perry, 1997, p. 11).

The works belong to an impressionism period. The three paintings chosen for comparison are the works of Cassatt Mary, Renoir Pierre-Aguste and Signac Paul. In all paintings, the theme involves people in a house setting. At a glance, the paintings do not have many details except the subjects in their setting.

The positioning of main figures in the frames is a point that draws interest. In the works below, the figures assume a central location in the frame. In addition, the figures in the pictures are presented in bold colors. The bold colors are blended well with shadows to create an outstanding brilliance.

The above paintings are, from left to right, Mary Cassatt’s 1880 painting, Renoir Pierre-Auguste’s 1864 painting, and Signac Paul’s 1885 painting. The first two paintings have their main figures positioned in the foreground. The last painting has the main figures in the middle ground of the frame.

However, a viewer of the painting cannot miss to note the inclusion of purple colors in all paintings. Therefore, the usage of bold colors that present a shimmering effect, and softened outlines of images is evidence that these paintings belong to the impressionism style of painting. Consequently, Mary Cassatt, Renoir Pierre-Aguste, and Signac Paul were impressionists.

Mary Cassatt’s paintings, during the impressionism period, often depicted family life. In the first place, she painted ladies in their homes. For instance, the painting above is entitled, Lydia crocheting in the Garden at Marley . At that time, her male compatriots in the art painting were working on landscapes.

The impressionism movement was the school of thought in the painting world that Mary lived in. The greatest influence for in-home paintings was females in her time were not allowed to walk alone unattended. This piece of work was done when her sister was ill. There is vibrancy in the painting.

However, the face of Lydia is sad. Therefore, Mary must have been sad too; her sister was ill at the time. One should note that the painting was made in France at that time. Women’s place in society was confined to the homesteads. This influenced the setting of her paintings (Swain, 2011, p 20).

Renoir’s painting above is entitled Little Miss Romaine Lacaux . This oil on canvas paint was done in 1864. The painting was also influenced by the impressionism school of thought. This painting is one among many others depicting children. He held a philosophy of living and working. The main influence for this painting was the closure of the Gleyre Studio in 1864 (Klein & Monet, 2006, p 11). Another influence was his affection for children. His age at that time might have influenced this affection.

Paul Signac had a wealthy background. His painting career was initially influenced by his friendship with other artists like Monet. Signac was both an anarchist and libertarian. The painting illustrated above was created in 1885; the year Signac was in constant resistance from bourgeois (Walther & Suckale, 2002, p 508).

Generally, Signac was influenced by impressionist paintings of artists like Monet and Seurat. Two milliners, Rue du Caire portray the widely held idea in the 19 th century that a woman’s work was indoors. Thus, this picture reveals a disorganized environment in which a woman conducts her daily chores.

The three artworks belong to different artists but same time period. The works are further distinguished from one another through philosophies that an artist held then. In this example, the school of thought was impressionism. As a result, each artist combined artistic requirements of impressionism with prevailing situations. This combination was represented as a pictorial idea of the artist about some subject. Therefore, the school of thought, at that time influenced an artwork.

In the first painting made by Mary Cassatt, the blend of colors offsets the dull mood of the picture’s face. The image is generally flat. Nevertheless, the brown color scaling the perspective in the middle ground of the frame adds some form and texture picture. The large bonnet worn by the lady suggests the painters’ internal feeling of hiding a sad mood in the face of the picture.

In the second painting, Renoir combines the effect of shadows and light to offset the flat upper part of the girl with form. The circular shape of the cloth in the lower waistline of the picture introduces motion and transition in colors. Colors begin with dullness and brighten upwards. This color transition introduces innocence in the child; the subject matter.

Lastly, Signac’s milliner is based on flatness. The brushstrokes applied to the tablecloth combines with the wallpaper to introduce parallelism, in the picture. However, flatness of the picture is reduced by the bending figure. Form is introduced in the picture, around the back of the milliner. This underscores the painter’s subject matter; domestic chores of a woman, that time.

The painting of Lydia Crocheting in the Garden at Marley has an awkward aesthetic value. The large bonnet on her head does not match with either her thin body or sad face. Unlike the other two paintings, Mary Cassatt symbolically expressed her sadness through this quality.

There is a quality of elegance in Little miss Romaine by Renoir. The elegance is enhanced by usage of bright colors around the face of the girl. This symbolically depicts innocence in children. Lastly, the aesthetic quality in the Two Milliners is powerful. The bending woman in the picture symbolically represents burden. Despite the differences, all paintings embrace the use of bold and bright colors to present their subject matter.

In conclusion, impressionism employed the use of bold and bright colors in most of the paintings. The most preferred color was purple. The paintings comprised majorly of outdoor scenes like landscapes. Through such artworks, an artist’s subject matter is evident. Therefore, impressionists usually painted according to the prevailing situations at the time.

Klein, AG. & Monet, C. (2006). Claude Monet . Minnesota: ABDO Publishing Company.

Olga’s Gallery (2011). Web.

Perry, G. (1997). Impressionist Palette: quilt color and design . California: C&T Publishing Inc.

Swain, C. (2011). Claude Monet, Edward Degas, Mary Cassatt, Vincent Van Vogh . London: Benchmark Education Company.

Walther, IF. & Suckale, R. (2002). Masterpieces of Western Art : A History of Art in 900 individual studies from the Gothic to the present day, part 1. Bonn: Taschen.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 8). Works of Art. https://ivypanda.com/essays/works-of-art-essay/

"Works of Art." IvyPanda , 8 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/works-of-art-essay/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Works of Art'. 8 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Works of Art." February 8, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/works-of-art-essay/.

1. IvyPanda . "Works of Art." February 8, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/works-of-art-essay/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Works of Art." February 8, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/works-of-art-essay/.

- The Influence of Japanese Art Upon Mary Cassatt

- John Renoir, a French Filmmaker

- Monet, Renoir, Cezanne: Analysis of the Art Works

- Pierre Renoir and Paul Gauguin in Chrysler Museum of Art

- Primitivism and the Avant-Garde

- The Search for Truth: Early Photography, Realism, and Impressionism

- Women Writers and Artists About Social Problems

- Oil Paintings by Renoir, Maler, de Corter

- An analysis of the Luncheon of the boating party

- The Art Movement of Impressionism

- Art through History

- Art Period Comparison: Classicism and Middle Age

- Art Transformation Since the Middle Ages to the Current Times

- Art influences Culture: Romanticism & Realism

- Necklace of Five Gold Pendants and Twenty One Stone Beads

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing Essays in Art History

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

These OWL resources provide guidance on typical genres with the art history discipline that may appear in professional settings or academic assignments, including museum catalog entries, museum title cards, art history analysis, notetaking, and art history exams.

Art History Analysis – Formal Analysis and Stylistic Analysis

Typically in an art history class the main essay students will need to write for a final paper or for an exam is a formal or stylistic analysis.

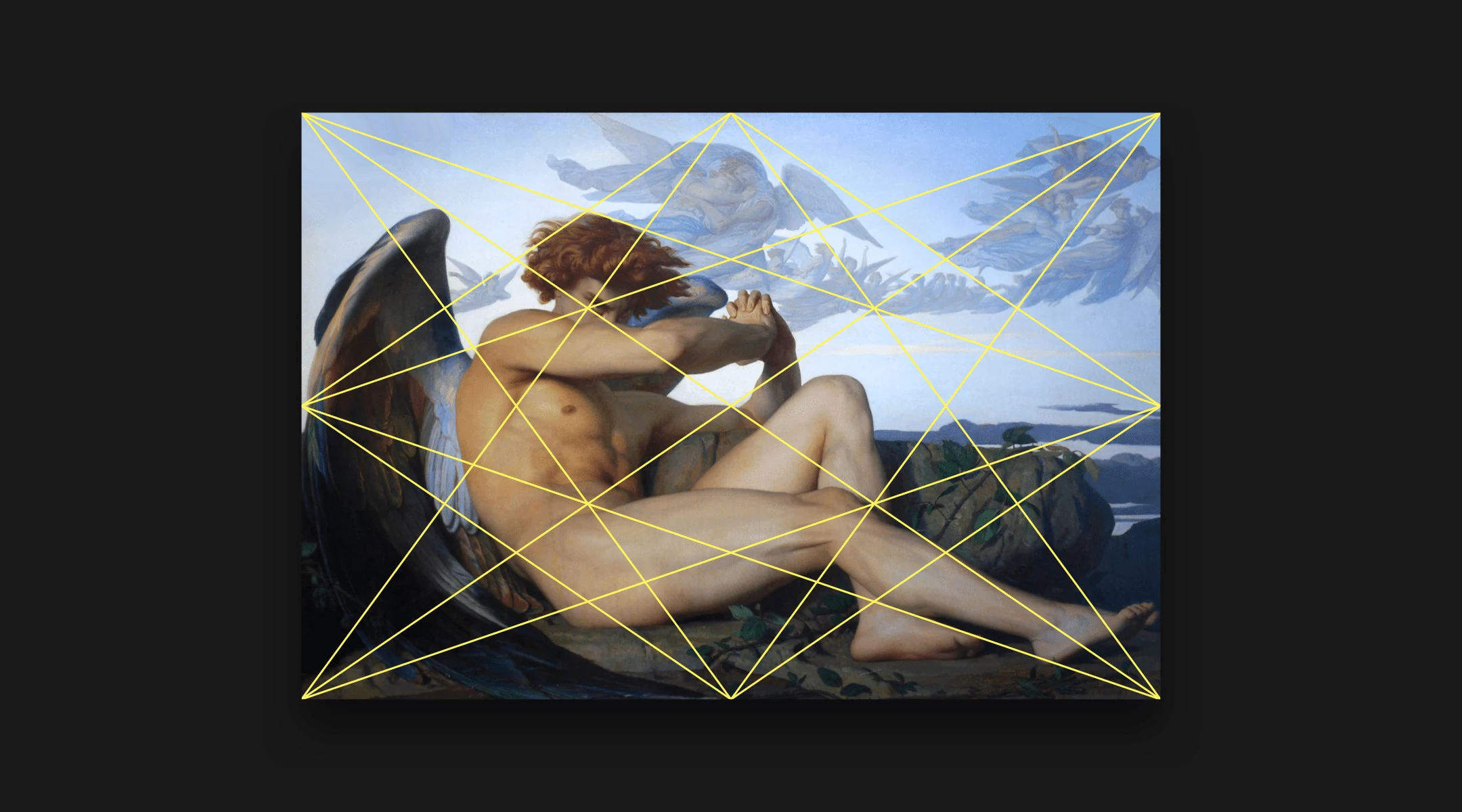

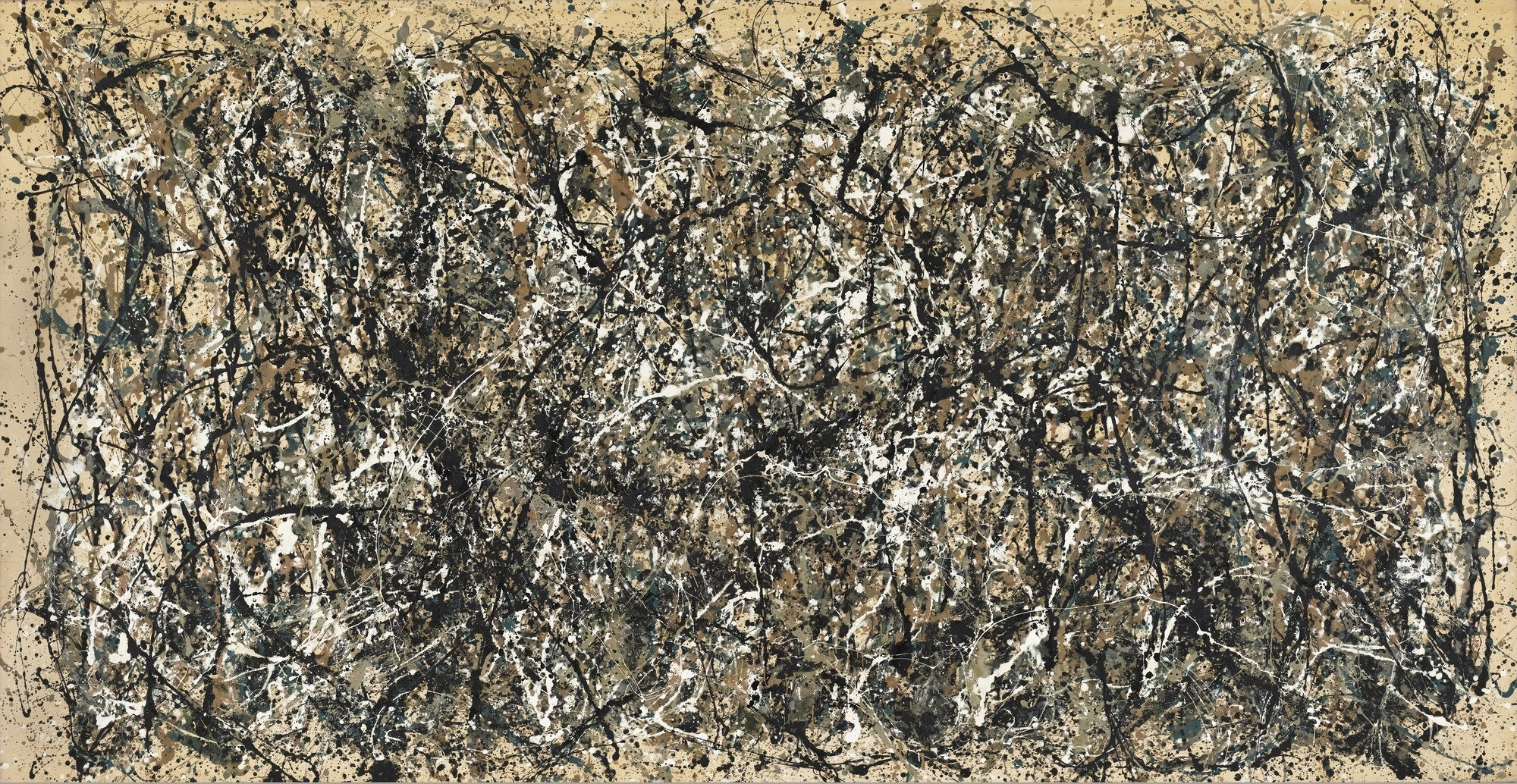

A formal analysis is just what it sounds like – you need to analyze the form of the artwork. This includes the individual design elements – composition, color, line, texture, scale, contrast, etc. Questions to consider in a formal analysis is how do all these elements come together to create this work of art? Think of formal analysis in relation to literature – authors give descriptions of characters or places through the written word. How does an artist convey this same information?

Organize your information and focus on each feature before moving onto the text – it is not ideal to discuss color and jump from line to then in the conclusion discuss color again. First summarize the overall appearance of the work of art – is this a painting? Does the artist use only dark colors? Why heavy brushstrokes? etc and then discuss details of the object – this specific animal is gray, the sky is missing a moon, etc. Again, it is best to be organized and focused in your writing – if you discuss the animals and then the individuals and go back to the animals you run the risk of making your writing unorganized and hard to read. It is also ideal to discuss the focal of the piece – what is in the center? What stands out the most in the piece or takes up most of the composition?

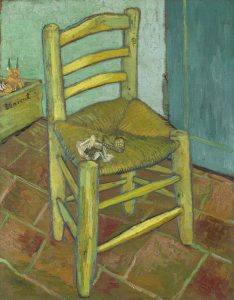

A stylistic approach can be described as an indicator of unique characteristics that analyzes and uses the formal elements (2-D: Line, color, value, shape and 3-D all of those and mass).The point of style is to see all the commonalities in a person’s works, such as the use of paint and brush strokes in Van Gogh’s work. Style can distinguish an artist’s work from others and within their own timeline, geographical regions, etc.

Methods & Theories To Consider:

Expressionism

Instructuralism

Postmodernism

Social Art History

Biographical Approach

Poststructuralism

Museum Studies

Visual Cultural Studies

Stylistic Analysis Example:

The following is a brief stylistic analysis of two Greek statues, an example of how style has changed because of the “essence of the age.” Over the years, sculptures of women started off as being plain and fully clothed with no distinct features, to the beautiful Venus/Aphrodite figures most people recognize today. In the mid-seventh century to the early fifth, life-sized standing marble statues of young women, often elaborately dress in gaily painted garments were created known as korai. The earliest korai is a Naxian women to Artemis. The statue wears a tight-fitted, belted peplos, giving the body a very plain look. The earliest korai wore the simpler Dorian peplos, which was a heavy woolen garment. From about 530, most wear a thinner, more elaborate, and brightly painted Ionic linen and himation. A largely contrasting Greek statue to the korai is the Venus de Milo. The Venus from head to toe is six feet seven inches tall. Her hips suggest that she has had several children. Though her body shows to be heavy, she still seems to almost be weightless. Viewing the Venus de Milo, she changes from side to side. From her right side she seems almost like a pillar and her leg bears most of the weight. She seems be firmly planted into the earth, and since she is looking at the left, her big features such as her waist define her. The Venus de Milo had a band around her right bicep. She had earrings that were brutally stolen, ripping her ears away. Venus was noted for loving necklaces, so it is very possibly she would have had one. It is also possible she had a tiara and bracelets. Venus was normally defined as “golden,” so her hair would have been painted. Two statues in the same region, have throughout history, changed in their style.

Compare and Contrast Essay

Most introductory art history classes will ask students to write a compare and contrast essay about two pieces – examples include comparing and contrasting a medieval to a renaissance painting. It is always best to start with smaller comparisons between the two works of art such as the medium of the piece. Then the comparison can include attention to detail so use of color, subject matter, or iconography. Do the same for contrasting the two pieces – start small. After the foundation is set move on to the analysis and what these comparisons or contrasting material mean – ‘what is the bigger picture here?’ Consider why one artist would wish to show the same subject matter in a different way, how, when, etc are all questions to ask in the compare and contrast essay. If during an exam it would be best to quickly outline the points to make before tackling writing the essay.

Compare and Contrast Example:

Stele of Hammurabi from Susa (modern Shush, Iran), ca. 1792 – 1750 BCE, Basalt, height of stele approx. 7’ height of relief 28’

Stele, relief sculpture, Art as propaganda – Hammurabi shows that his law code is approved by the gods, depiction of land in background, Hammurabi on the same place of importance as the god, etc.

Top of this stele shows the relief image of Hammurabi receiving the law code from Shamash, god of justice, Code of Babylonian social law, only two figures shown, different area and time period, etc.

Stele of Naram-sin , Sippar Found at Susa c. 2220 - 2184 bce. Limestone, height 6'6"

Stele, relief sculpture, Example of propaganda because the ruler (like the Stele of Hammurabi) shows his power through divine authority, Naramsin is the main character due to his large size, depiction of land in background, etc.

Akkadian art, made of limestone, the stele commemorates a victory of Naramsin, multiple figures are shown specifically soldiers, different area and time period, etc.

Iconography

Regardless of what essay approach you take in class it is absolutely necessary to understand how to analyze the iconography of a work of art and to incorporate into your paper. Iconography is defined as subject matter, what the image means. For example, why do things such as a small dog in a painting in early Northern Renaissance paintings represent sexuality? Additionally, how can an individual perhaps identify these motifs that keep coming up?

The following is a list of symbols and their meaning in Marriage a la Mode by William Hogarth (1743) that is a series of six paintings that show the story of marriage in Hogarth’s eyes.

- Man has pockets turned out symbolizing he has lost money and was recently in a fight by the state of his clothes.

- Lap dog shows loyalty but sniffs at woman’s hat in the husband’s pocket showing sexual exploits.

- Black dot on husband’s neck believed to be symbol of syphilis.

- Mantel full of ugly Chinese porcelain statues symbolizing that the couple has no class.

- Butler had to go pay bills, you can tell this by the distasteful look on his face and that his pockets are stuffed with bills and papers.

- Card game just finished up, women has directions to game under foot, shows her easily cheating nature.

- Paintings of saints line a wall of the background room, isolated from the living, shows the couple’s complete disregard to faith and religion.

- The dangers of sexual excess are underscored in the Hograth by placing Cupid among ruins, foreshadowing the inevitable ruin of the marriage.

- Eventually the series (other five paintings) shows that the woman has an affair, the men duel and die, the woman hangs herself and the father takes her ring off her finger symbolizing the one thing he could salvage from the marriage.

The Value of Art Why should we care about art?

One of the first questions raised when talking about art is simple—why should we care? Art in the contemporary era is easy to dismiss as a selfish pastime for people who have too much time on their hands. Creating art doesn't cure disease, build roads, or feed the poor. So to understand the value of art, let’s look at how art has been valued through history and consider how it is valuable today.

The value of creating

At its most basic level, the act of creating is rewarding in itself. Children draw for the joy of it before they can speak, and creating pictures, sculptures and writing is both a valuable means of communicating ideas and simply fun. Creating is instinctive in humans, for the pleasure of exercising creativity. While applied creativity is valueable in a work context, free-form creativity leads to new ideas.

Material value

Through the ages, art has often been created from valuable materials. Gold , ivory and gemstones adorn medieval crowns , and even the paints used by renaissance artists were made from rare materials like lapis lazuli , ground into pigment. These objects have creative value for their beauty and craftsmanship, but they are also intrinsically valuable because of the materials they contain.

Historical value

Artwork is a record of cultural history. Many ancient cultures are entirely lost to time except for the artworks they created, a legacy that helps us understand our human past. Even recent work can help us understand the lives and times of its creators, like the artwork of African-American artists during the Harlem Renaissance . Artwork is inextricably tied to the time and cultural context it was created in, a relationship called zeitgeist , making art a window into history.

Religious value

For religions around the world, artwork is often used to illustrate their beliefs. Depicting gods and goddesses, from Shiva to the Madonna , make the concepts of faith real to the faithful. Artwork has been believed to contain the spirits of gods or ancestors, or may be used to imbue architecture with an aura of awe and worship like the Badshahi Mosque .

Patriotic value

Art has long been a source of national pride, both as an example of the skill and dedication of a country’s artisans and as expressions of national accomplishments and history, like the Arc de Triomphe , a heroic monument honoring the soldiers who died in the Napoleonic Wars. The patriotic value of art slides into propaganda as well, used to sway the populace towards a political agenda.

Symbolic value

Art is uniquely suited to communicating ideas. Whether it’s writing or painting or sculpture, artwork can distill complex concepts into symbols that can be understood, even sometimes across language barriers and cultures. When art achieves symbolic value it can become a rallying point for a movement, like J. Howard Miller’s 1942 illustration of Rosie the Riveter, which has become an icon of feminism and women’s economic impact across the western world.

Societal value

And here’s where the rubber meets the road: when we look at our world today, we see a seemingly insurmountable wave of fear, bigotry, and hatred expressed by groups of people against anyone who is different from them. While issues of racial and gender bias, homophobia and religious intolerance run deep, and have many complex sources, much of the problem lies with a lack of empathy. When you look at another person and don't see them as human, that’s the beginning of fear, violence and war. Art is communication. And in the contemporary world, it’s often a deeply personal communication. When you create art, you share your worldview, your history, your culture and yourself with the world. Art is a window, however small, into the human struggles and stories of all people. So go see art, find art from other cultures, other religions, other orientations and perspectives. If we learn about each other, maybe we can finally see that we're all in this together. Art is a uniquely human expression of creativity. It helps us understand our past, people who are different from us, and ultimately, ourselves.

Reed Enger, "The Value of Art, Why should we care about art?," in Obelisk Art History , Published June 24, 2017; last modified November 08, 2022, http://www.arthistoryproject.com/essays/the-value-of-art/.

Art History Methodologies

Eight ways to understand art

Categorizing Art

Can we make sense of it all?

Advanced Composition Techniques

Let's get mathematical

By continuing to browse Obelisk you agree to our Cookie Policy

- All Periods

- All Regions

- Departments / Collections

Ottoman Wedding Dresses, East to West

The Feathered Serpent Pyramid and Ciudadela of Teotihuacan (ca. 150–250 CE)

Teotihuacan (ca. 100 BCE–800 CE)

Stone Masks and Figurines from Northwest Argentina (500 BCE–650 CE)

Maria Monaci Gallenga (1880–1944)

All essays (1056), abraham and david roentgen, abstract expressionism, the achaemenid persian empire (550–330 b.c.), adélaïde labille-guiard (1749–1803), the aesthetic of the sketch in nineteenth-century france, african christianity in ethiopia, african christianity in kongo, african influences in modern art, african lost-wax casting, african rock art, african rock art of the central zone, african rock art of the northern zone, african rock art of the southern zone, african rock art: game pass, african rock art: tassili-n-ajjer (8000 b.c.–), african rock art: the coldstream stone, africans in ancient greek art, afro-portuguese ivories, the age of iron in west africa, the age of saint louis (1226–1270), the age of süleyman “the magnificent” (r. 1520–1566), the akkadian period (ca. 2350–2150 b.c.), albrecht dürer (1471–1528), alexander jackson davis (1803–1892), alfred stieglitz (1864–1946) and american photography, alfred stieglitz (1864–1946) and his circle, alice cordelia morse (1863–1961), allegories of the four continents, the amarna letters, america comes of age: 1876–1900, american bronze casting, american federal-era period rooms, american furniture, 1620–1730: the seventeenth-century and william and mary styles, american furniture, 1730–1790: queen anne and chippendale styles, american georgian interiors (mid-eighteenth-century period rooms), american impressionism, american ingenuity: sportswear, 1930s–1970s, american needlework in the eighteenth century, american neoclassical sculptors abroad, american portrait miniatures of the eighteenth century, american portrait miniatures of the nineteenth century, american quilts and coverlets, american relief sculpture, american revival styles, 1840–76, american rococo, american scenes of everyday life, 1840–1910, american sculpture at the world’s columbian exposition, chicago, 1893, american silver vessels for wine, beer, and punch, american women sculptors, americans in paris, 1860–1900, amulets and talismans from the islamic world, anatomy in the renaissance, ancient american jade, ancient egyptian amulets, ancient greek bronze vessels, ancient greek colonization and trade and their influence on greek art, ancient greek dress, ancient maya painted ceramics, ancient maya sculpture, ancient near eastern openwork bronzes, andean textiles, animals in ancient near eastern art, animals in medieval art, ann lowe (ca. 1898–1981), annibale carracci (1560–1609), anselm kiefer (born 1945), antelopes and queens: bambara sculpture from the western sudan: a groundbreaking exhibition at the museum of primitive art, new york, 1960, antique engraved gems and renaissance collectors, antoine watteau (1684–1721), antonello da messina (ca. 1430–1479), the antonine dynasty (138–193), antonio canova (1757–1822), apollo 11 (ca. 25,500–23,500 b.c.) and wonderwerk (ca. 8000 b.c.) cave stones, architectural models from the ancient americas, architecture in ancient greece, architecture in renaissance italy, architecture, furniture, and silver from colonial dutch america, archtop guitars and mandolins, arms and armor in medieval europe, arms and armor in renaissance europe, arms and armor—common misconceptions and frequently asked questions, art and craft in archaic sparta, art and death in medieval byzantium, art and death in the middle ages, art and identity in the british north american colonies, 1700–1776, art and love in the italian renaissance, art and nationalism in twentieth-century turkey, art and photography: 1990s to the present, art and photography: the 1980s, art and society of the new republic, 1776–1800, art and the fulani/fulbe people, art for the christian liturgy in the middle ages, art nouveau, the art of classical greece (ca. 480–323 b.c.), the art of ivory and gold in northern europe around 1000 a.d., the art of the abbasid period (750–1258), the art of the almoravid and almohad periods (ca. 1062–1269), art of the asante kingdom, the art of the ayyubid period (ca. 1171–1260), the art of the book in the ilkhanid period, the art of the book in the middle ages, art of the edo period (1615–1868), the art of the fatimid period (909–1171), art of the first cities in the third millennium b.c., art of the hellenistic age and the hellenistic tradition, the art of the ilkhanid period (1256–1353), art of the korean renaissance, 1400–1600, the art of the mamluk period (1250–1517), the art of the mughals after 1600, the art of the mughals before 1600, the art of the nasrid period (1232–1492), the art of the ottomans after 1600, the art of the ottomans before 1600, art of the pleasure quarters and the ukiyo-e style, art of the roman provinces, 1–500 a.d., the art of the safavids before 1600, the art of the seljuq period in anatolia (1081–1307), the art of the seljuqs of iran (ca. 1040–1157), art of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in naples, art of the sufis, the art of the timurid period (ca. 1370–1507), the art of the umayyad period (661–750), the art of the umayyad period in spain (711–1031), art, architecture, and the city in the reign of amenhotep iv / akhenaten (ca. 1353–1336 b.c.), the art, form, and function of gilt bronze in the french interior, arthur dove (1880–1946), an artisan’s tomb in new kingdom egypt, artistic interaction among cultures in medieval iberia, artists of the saqqakhana movement, the arts and crafts movement in america, the arts of iran, 1600–1800, arts of power associations in west africa, the arts of the book in the islamic world, 1600–1800, arts of the greater himalayas: kashmir, tibet, and nepal, arts of the mission schools in mexico, arts of the san people in nomansland, arts of the spanish americas, 1550–1850, asante royal funerary arts, asante textile arts, the ashcan school, asher brown durand (1796–1886), assyria, 1365–609 b.c., the assyrian sculpture court, astronomy and astrology in the medieval islamic world, asuka and nara periods (538–794), athenian vase painting: black- and red-figure techniques, athletics in ancient greece, augustan rule (27 b.c.–14 a.d.), the augustan villa at boscotrecase, auguste renoir (1841–1919), auguste rodin (1840–1917), augustus saint-gaudens (1848–1907), aztec stone sculpture, the bamana ségou state, barbarians and romans, the barbizon school: french painters of nature, baroque rome, baseball cards in the jefferson r. burdick collection, bashford dean and the development of helmets and body armor during world war i, baths and bathing culture in the middle east: the hammam, the bauhaus, 1919–1933, benin chronology, bessie potter vonnoh (1872–1955), birds of the andes, birth and family in the italian renaissance, the birth and infancy of christ in italian painting, the birth of islam, blackwater draw (ca. 9500–3000 b.c.), blackwork: a new technique in the field of ornament prints (ca. 1585–1635), blown glass from islamic lands, board games from ancient egypt and the near east, body/landscape: photography and the reconfiguration of the sculptural object, the book of hours: a medieval bestseller, boscoreale: frescoes from the villa of p. fannius synistor, botanical imagery in european painting, bronze sculpture in the renaissance, bronze statuettes of the american west, 1850–1915, buddhism and buddhist art, building stories: contextualizing architecture at the cloisters, burgundian netherlands: court life and patronage, burgundian netherlands: private life, byzantine art under islam, the byzantine city of amorium, byzantine ivories, the byzantine state under justinian i (justinian the great), byzantium (ca. 330–1453), calligraphy in islamic art, cameo appearances, candace wheeler (1827–1923), capac hucha as an inca assemblage, caravaggio (michelangelo merisi) (1571–1610) and his followers, carolingian art, carpets from the islamic world, 1600–1800, cave sculpture from the karawari, ceramic technology in the seljuq period: stonepaste in syria and iran in the eleventh century, ceramic technology in the seljuq period: stonepaste in syria and iran in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, ceramics in the french renaissance, cerro sechín, cerro sechín: stone sculpture, the cesnola collection at the metropolitan museum of art, charles eames (1907–1978) and ray eames (1913–1988), charles frederick worth (1825–1895) and the house of worth, charles james (1906–1978), charles sheeler (1883–1965), chauvet cave (ca. 30,000 b.c.), childe hassam (1859–1935), chinese buddhist sculpture, chinese calligraphy, chinese cloisonné, chinese gardens and collectors’ rocks, chinese handscrolls, chinese hardstone carvings, chinese painting, the chiton, peplos, and himation in modern dress, the chopine, christian dior (1905–1957), christopher dresser (1834–1904), classical antiquity in the middle ages, classical art and modern dress, classical cyprus (ca. 480–ca. 310 b.c.), classicism in modern dress, claude lorrain (1604/5–1682), claude monet (1840–1926), coffee, tea, and chocolate in early colonial america, collecting for the kunstkammer, colonial kero cups, colossal temples of the roman near east, commedia dell’arte, company painting in nineteenth-century india, conceptual art and photography, constantinople after 1261, contemporary deconstructions of classical dress, contexts for the display of statues in classical antiquity, cosmic buddhas in the himalayas, costume in the metropolitan museum of art, the countess da castiglione, courtly art of the ilkhanids, courtship and betrothal in the italian renaissance, cristobal balenciaga (1895–1972), the croome court tapestry room, worcestershire, the crucifixion and passion of christ in italian painting, the crusades (1095–1291), the cult of the virgin mary in the middle ages, cut and engraved glass from islamic lands, cyprus—island of copper, daguerre (1787–1851) and the invention of photography, the daguerreian age in france: 1839–55, the daguerreian era and early american photography on paper, 1839–60, the damascus room, daniel chester french (1850–1931), daoism and daoist art, david octavius hill (1802–1870) and robert adamson (1821–1848), death, burial, and the afterlife in ancient greece, the decoration of arms and armor, the decoration of european armor, the decoration of tibetan arms and armor, design reform, design, 1900–1925, design, 1925–50, design, 1950–75, design, 1975–2000, the development of the recorder, direct versus indirect casting of small bronzes in the italian renaissance, divination and senufo sculpture in west africa, domenichino (1581–1641), domestic art in renaissance italy, donatello (ca. 1386–1466), drawing in the middle ages, dress rehearsal: the origins of the costume institute, dressing for the cocktail hour, dualism in andean art, duncan phyfe (1770–1854) and charles-honoré lannuier (1779–1819), dutch and flemish artists in rome, 1500–1600, eagles after the american revolution, early cycladic art and culture, early documentary photography, early dynastic sculpture, 2900–2350 b.c., early excavations in assyria, early histories of photography in west africa (1860–1910), early maori wood carvings, early modernists and indian traditions, early netherlandish painting, early photographers of the american west: 1860s–70s, early qur’ans (8th–early 13th century), east and west: chinese export porcelain, east asian cultural exchange in tiger and dragon paintings, easter island, eastern religions in the roman world, ebla in the third millennium b.c., edgar degas (1834–1917): bronze sculpture, edgar degas (1834–1917): painting and drawing, edo-period japanese porcelain, édouard baldus (1813–1889), édouard manet (1832–1883), edward hopper (1882–1967), edward j. steichen (1879–1973): the photo-secession years, edward lycett (1833–1910), egypt in the late period (ca. 664–332 b.c.), egypt in the middle kingdom (ca. 2030–1650 b.c.), egypt in the new kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 b.c.), egypt in the old kingdom (ca. 2649–2130 b.c.), egypt in the ptolemaic period, egypt in the third intermediate period (ca. 1070–664 b.c.), egyptian faience: technology and production, egyptian modern art, egyptian red gold, egyptian revival, egyptian tombs: life along the nile, eighteenth-century european dress, the eighteenth-century pastel portrait, eighteenth-century silhouette and support, eighteenth-century women painters in france, el greco (1541–1614), élisabeth louise vigée le brun (1755–1842), elizabethan england, elsa schiaparelli (1890–1973), empire style, 1800–1815, the empires of the western sudan, the empires of the western sudan: ghana empire, the empires of the western sudan: mali empire, the empires of the western sudan: songhai empire, enameled and gilded glass from islamic lands, english embroidery of the late tudor and stuart eras, english ornament prints and furniture books in eighteenth-century america, english silver, 1600–1800, ernest hemingway (1899–1961) and art, ernst emil herzfeld (1879–1948) in persepolis, ernst emil herzfeld (1879–1948) in samarra, etching in eighteenth-century france: artists and amateurs, the etching revival in nineteenth-century france, ethiopia’s enduring cultural heritage, ethiopian healing scrolls, etruscan art, etruscan language and inscriptions, eugène atget (1857–1927), europe and the age of exploration, europe and the islamic world, 1600–1800, european clocks in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, european exploration of the pacific, 1600–1800, european revivalism, european tapestry production and patronage, 1400–1600, european tapestry production and patronage, 1600–1800, exchange of art and ideas: the benin, owo, and ijebu kingdoms, exoticism in the decorative arts, extravagant monstrosities: gold- and silversmith designs in the auricular style, eynan/ain mallaha (12,500–10,000 b.c.), fabricating sixteenth-century netherlandish boxwood miniatures, the face in medieval sculpture, famous makers of arms and armors and european centers of production, fashion in european armor, fashion in european armor, 1000–1300, fashion in european armor, 1300–1400, fashion in european armor, 1400–1500, fashion in european armor, 1500–1600, fashion in european armor, 1600–1700, fashion in safavid iran, fatimid jewelry, fell’s cave (9000–8000 b.c.), fernand léger (1881–1955), feudalism and knights in medieval europe, figural representation in islamic art, filippino lippi (ca. 1457–1504), fire gilding of arms and armor, the five wares of south italian vase painting, the flavian dynasty (69–96 a.d.), flemish harpsichords and virginals, flood stories, folios from the great mongol shahnama (book of kings), folios from the jami‘ al-tavarikh (compendium of chronicles), fontainebleau, food and drink in european painting, 1400–1800, foundations of aksumite civilization and its christian legacy (1st–8th century), fra angelico (ca. 1395–1455), francisco de goya (1746–1828) and the spanish enlightenment, françois boucher (1703–1770), frank lloyd wright (1867–1959), frans hals (1582/83–1666), frederic edwin church (1826–1900), frederic remington (1861–1909), frederick william macmonnies (1863–1937), the french academy in rome, french art deco, french art pottery, french decorative arts during the reign of louis xiv (1654–1715), french faience, french furniture in the eighteenth century: case furniture, french furniture in the eighteenth century: seat furniture, french porcelain in the eighteenth century, french silver in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, frescoes and wall painting in late byzantine art, from geometric to informal gardens in the eighteenth century, from italy to france: gardens in the court of louis xiv and after, from model to monument: american public sculpture, 1865–1915, the fulani/fulbe people, the function of armor in medieval and renaissance europe, funerary vases in southern italy and sicily, furnishings during the reign of louis xiv (1654–1715), gabrielle “coco” chanel (1883–1971) and the house of chanel, gardens in the french renaissance, gardens of western europe, 1600–1800, genre painting in northern europe, geometric abstraction, geometric and archaic cyprus, geometric art in ancient greece, geometric patterns in islamic art, george inness (1825–1894), george washington: man, myth, monument, georges seurat (1859–1891) and neo-impressionism, georgia o’keeffe (1887–1986), gerard david (born about 1455, died 1523), german and austrian porcelain in the eighteenth century, the ghent altarpiece, gian lorenzo bernini (1598–1680), gilbert stuart (1755–1828), giovanni battista piranesi (1720–1778), giovanni battista tiepolo (1696–1770), gladiators: types and training, glass from islamic lands, glass ornaments in late antiquity and early islam (ca. 500–1000), glass with mold-blown decoration from islamic lands, the gods and goddesses of canaan, gold in ancient egypt, gold in asante courtly arts, gold in the ancient americas, gold of the indies, the golden age of french furniture in the eighteenth century, the golden harpsichord of michele todini (1616–1690), golden treasures: the royal tombs of silla, goryeo celadon, the grand tour, the graphic art of max klinger, great plains indians musical instruments, great serpent mound, great zimbabwe (11th–15th century), the greater ottoman empire, 1600–1800, greek art in the archaic period, greek gods and religious practices, greek hydriai (water jars) and their artistic decoration, the greek key and divine attributes in modern dress, greek terracotta figurines with articulated limbs, gustave courbet (1819–1877), gustave le gray (1820–1884), hagia sophia, 532–37, the halaf period (6500–5500 b.c.), han dynasty (206 b.c.–220 a.d.), hanae mori (1926–2022), hans talhoffer’s fight book, a sixteenth-century manuscript about the art of fighting, harry burton (1879–1940): the pharaoh’s photographer, hasanlu in the iron age, haute couture, heian period (794–1185), hellenistic and roman cyprus, hellenistic jewelry, hendrick goltzius (1558–1617), henri cartier-bresson (1908–2004), henri de toulouse-lautrec (1864–1901), henri matisse (1869–1954), henry kirke brown (1814–1886), john quincy adams ward (1830–1910), and realism in american sculpture, heroes in italian mythological prints, hinduism and hindu art, hippopotami in ancient egypt, hiram powers (1805–1873), the hittites, the holy roman empire and the habsburgs, 1400–1600, hopewell (1–400 a.d.), horse armor in europe, hot-worked glass from islamic lands, the house of jeanne hallée (1870–1924), the housemistress in new kingdom egypt: hatnefer, how medieval and renaissance tapestries were made, the hudson river school, hungarian silver, icons and iconoclasm in byzantium, the idea and invention of the villa, ife (from ca. 6th century), ife pre-pavement and pavement era (800–1000 a.d.), ife terracottas (1000–1400 a.d.), igbo-ukwu (ca. 9th century), images of antiquity in limoges enamels in the french renaissance, impressionism: art and modernity, in pursuit of white: porcelain in the joseon dynasty, 1392–1910, indian knoll (3000–2000 b.c.), indian textiles: trade and production, indigenous arts of the caribbean, industrialization and conflict in america: 1840–1875, the industrialization of french photography after 1860, inland niger delta, intellectual pursuits of the hellenistic age, intentional alterations of early netherlandish painting, interior design in england, 1600–1800, interiors imagined: folding screens, garments, and clothing stands, international pictorialism, internationalism in the tang dynasty (618–907), introduction to prehistoric art, 20,000–8000 b.c., the isin-larsa and old babylonian periods (2004–1595 b.c.), islamic arms and armor, islamic art and culture: the venetian perspective, islamic art of the deccan, islamic carpets in european paintings, italian painting of the later middle ages, italian porcelain in the eighteenth century, italian renaissance frames, ivory and boxwood carvings, 1450–1800, ivory carving in the gothic era, thirteenth–fifteenth centuries, jacopo dal ponte, called bassano (ca. 1510–1592), jade in costa rica, jade in mesoamerica, jain manuscript painting, jain sculpture, james cox (ca. 1723–1800): goldsmith and entrepreneur, james mcneill whistler (1834–1903), james mcneill whistler (1834–1903) as etcher, jan gossart (ca. 1478–1532) and his circle, jan van eyck (ca. 1390–1441), the japanese blade: technology and manufacture, japanese illustrated handscrolls, japanese incense, the japanese tea ceremony, japanese weddings in the edo period (1615–1868), japanese writing boxes, jasper johns (born 1930), jean antoine houdon (1741–1828), jean honoré fragonard (1732–1806), jean-baptiste carpeaux (1827–1875), jean-baptiste greuze (1725–1805), jewish art in late antiquity and early byzantium, jews and the arts in medieval europe, jews and the decorative arts in early modern italy, jiahu (ca. 7000–5700 b.c.), joachim tielke (1641–1719), joan miró (1893–1983), johannes vermeer (1632–1675), johannes vermeer (1632–1675) and the milkmaid, john constable (1776–1837), john frederick kensett (1816–1872), john singer sargent (1856–1925), john singleton copley (1738–1815), john townsend (1733–1809), jōmon culture (ca. 10,500–ca. 300 b.c.), joseon buncheong ware: between celadon and porcelain, joseph mallord william turner (1775–1851), juan de flandes (active by 1496, died 1519), julia margaret cameron (1815–1879), the julio-claudian dynasty (27 b.c.–68 a.d.), kamakura and nanbokucho periods (1185–1392), the kano school of painting, kingdoms of madagascar: malagasy funerary arts, kingdoms of madagascar: malagasy textile arts, kingdoms of madagascar: maroserana and merina, kingdoms of the savanna: the kuba kingdom, kingdoms of the savanna: the luba and lunda empires, kings and queens of egypt, kings of brightness in japanese esoteric buddhist art, the kirtlington park room, oxfordshire, the kithara in ancient greece, kodak and the rise of amateur photography, kofun period (ca. 300–710), kongo ivories, korean buddhist sculpture (5th–9th century), korean munbangdo paintings, kushan empire (ca. second century b.c.–third century a.d.), la venta: sacred architecture, la venta: stone sculpture, the labors of herakles, lacquerware of east asia, landscape painting in chinese art, landscape painting in the netherlands, the lansdowne dining room, london, lapita pottery (ca. 1500–500 b.c.), lascaux (ca. 15,000 b.c.), late eighteenth-century american drawings, late medieval german sculpture, late medieval german sculpture: images for the cult and for private devotion, late medieval german sculpture: materials and techniques, late medieval german sculpture: polychromy and monochromy, the later ottomans and the impact of europe, le colis de trianon-versailles and paris openings, the legacy of genghis khan, the legacy of jacques louis david (1748–1825), leonardo da vinci (1452–1519), letterforms and writing in contemporary art, life of jesus of nazareth, life of the buddha, list of rulers of ancient egypt and nubia, list of rulers of ancient sudan, list of rulers of byzantium, list of rulers of china, list of rulers of europe, list of rulers of japan, list of rulers of korea, list of rulers of mesopotamia, list of rulers of south asia, list of rulers of the ancient greek world, list of rulers of the islamic world, list of rulers of the parthian empire, list of rulers of the roman empire, list of rulers of the sasanian empire, lithography in the nineteenth century, longevity in chinese art, louis comfort tiffany (1848–1933), louis-rémy robert (1810–1882), lovers in italian mythological prints, the lure of montmartre, 1880–1900, luxury arts of rome, lydenburg heads (ca. 500 a.d.), lydia and phrygia, made in india, found in egypt: red sea textile trade in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, made in italy: italian fashion from 1950 to now, the magic of signs and patterns in north african art, maiolica in the renaissance, mal’ta (ca. 20,000 b.c.), mangarevan sculpture, the manila galleon trade (1565–1815), mannerism: bronzino (1503–1572) and his contemporaries, the mantiq al-tair (language of the birds) of 1487, manuscript illumination in italy, 1400–1600, manuscript illumination in northern europe, mapungubwe (ca. 1050–1270), marcel duchamp (1887–1968), mary stevenson cassatt (1844–1926), the master of monte oliveto (active about 1305–35), the materials and techniques of american quilts and coverlets, the materials and techniques of english embroidery of the late tudor and stuart eras, mauryan empire (ca. 323–185 b.c.), medicine in classical antiquity, medicine in the middle ages, medieval aquamanilia, medieval european sculpture for buildings, medusa in ancient greek art, mendicant orders in the medieval world, the mesoamerican ballgame, mesopotamian creation myths, mesopotamian deities, mesopotamian magic in the first millennium b.c., the metropolitan museum’s excavations at nishapur, the metropolitan museum’s excavations at ctesiphon, the metropolitan museum’s excavations at qasr-i abu nasr, michiel sweerts and biblical subjects in dutch art, the middle babylonian / kassite period (ca. 1595–1155 b.c.) in mesopotamia, military music in american and european traditions, ming dynasty (1368–1644), minoan crete, mission héliographique, 1851, miyake, kawakubo, and yamamoto: japanese fashion in the twentieth century, moche decorated ceramics, moche portrait vessels, modern and contemporary art in iran, modern art in india, modern art in west and east pakistan, modern art in west asia: colonial to post-colonial, modern materials: plastics, modern storytellers: romare bearden, jacob lawrence, faith ringgold, momoyama period (1573–1615), monasticism in western medieval europe, the mon-dvaravati tradition of early north-central thailand, the mongolian tent in the ilkhanid period, monte albán, monte albán: sacred architecture, monte albán: stone sculpture, monumental architecture of the aksumite empire, the monumental stelae of aksum (3rd–4th century), mosaic glass from islamic lands, mountain and water: korean landscape painting, 1400–1800, muromachi period (1392–1573), music and art of china, music in ancient greece, music in the ancient andes, music in the renaissance, musical instruments of oceania, musical instruments of the indian subcontinent, musical terms for the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, mycenaean civilization, mystery cults in the greek and roman world, nabataean kingdom and petra, the nabis and decorative painting, nadar (1820–1910), the nahal mishmar treasure, nature in chinese culture, the nature of islamic art, the neoclassical temple, neoclassicism, neolithic period in china, nepalese painting, nepalese sculpture, netsuke: from fashion fobs to coveted collectibles, new caledonia, the new documentary tradition in photography, new ireland, new vision photography, a new visual language transmitted across asia, the new york dutch room, nicolas poussin (1594–1665), nineteenth-century american drawings, nineteenth-century american folk art, nineteenth-century american jewelry, nineteenth-century american silver, nineteenth-century classical music, nineteenth-century court arts in india, nineteenth-century english silver, nineteenth-century european textile production, nineteenth-century french realism, nineteenth-century iran: art and the advent of modernity, nineteenth-century iran: continuity and revivalism, nineteenth-century silhouette and support, nok terracottas (500 b.c.–200 a.d.), northern italian renaissance painting, northern mannerism in the early sixteenth century, northern song dynasty (960–1127), northwest coast indians musical instruments, the nude in baroque and later art, the nude in the middle ages and the renaissance, the nude in western art and its beginnings in antiquity, nudity and classical themes in byzantine art, nuptial furnishings in the italian renaissance, the old assyrian period (ca. 2000–1600 b.c.), orientalism in nineteenth-century art, orientalism: visions of the east in western dress, the origins of writing, ottonian art, pablo picasso (1881–1973), pachmari hills (ca. 9000–3000 b.c.), painted funerary monuments from hellenistic alexandria, painting formats in east asian art, painting in italian choir books, 1300–1500, painting in oil in the low countries and its spread to southern europe, painting the life of christ in medieval and renaissance italy, paintings of love and marriage in the italian renaissance, paolo veronese (1528–1588), the papacy and the vatican palace, the papacy during the renaissance, papyrus in ancient egypt, papyrus-making in egypt, the parthian empire (247 b.c.–224 a.d.), pastoral charms in the french renaissance, patronage at the early valois courts (1328–1461), patronage at the later valois courts (1461–1589), patronage of jean de berry (1340–1416), paul cézanne (1839–1906), paul gauguin (1848–1903), paul klee (1879–1940), paul poiret (1879–1944), paul revere, jr. (1734–1818), paul strand (1890–1976), period of the northern and southern dynasties (386–581), peter paul rubens (1577–1640) and anthony van dyck (1599–1641): paintings, peter paul rubens (1577–1640) and anthony van dyck (1599–1641): works on paper, petrus christus (active by 1444, died 1475/76), the phoenicians (1500–300 b.c.), photographers in egypt, photography and surrealism, photography and the civil war, 1861–65, photography at the bauhaus, photography in düsseldorf, photography in europe, 1945–60, photography in postwar america, 1945-60, photography in the expanded field: painting, performance, and the neo-avant-garde, photojournalism and the picture press in germany, phrygia, gordion, and king midas in the late eighth century b.c., the piano: the pianofortes of bartolomeo cristofori (1655–1731), the piano: viennese instruments, pictorialism in america, the pictures generation, pierre bonnard (1867–1947): the late interiors, pierre didot the elder (1761–1853), pieter bruegel the elder (ca. 1525–1569), pilgrimage in medieval europe, poetic allusions in the rajput and pahari painting of india, poets in italian mythological prints, poets, lovers, and heroes in italian mythological prints, polychrome sculpture in spanish america, polychromy of roman marble sculpture, popular religion: magical uses of imagery in byzantine art, portrait painting in england, 1600–1800, portraits of african leadership, portraits of african leadership: living rulers, portraits of african leadership: memorials, portraits of african leadership: royal ancestors, portraiture in renaissance and baroque europe, the portuguese in africa, 1415–1600, post-impressionism, postmodernism: recent developments in art in india, postmodernism: recent developments in art in pakistan and bangladesh, post-revolutionary america: 1800–1840, the postwar print renaissance in america, poverty point (2000–1000 b.c.), the praenestine cistae, prague during the rule of rudolf ii (1583–1612), prague, 1347–1437, pre-angkor traditions: the mekong delta and peninsular thailand, precisionism, prehistoric cypriot art and culture, prehistoric stone sculpture from new guinea, the pre-raphaelites, presidents of the united states of america, the print in the nineteenth century, the printed image in the west: aquatint, the printed image in the west: drypoint, the printed image in the west: engraving, the printed image in the west: etching, the printed image in the west: history and techniques, the printed image in the west: mezzotint, the printed image in the west: woodcut, printmaking in mexico, 1900–1950, private devotion in medieval christianity, profane love and erotic art in the italian renaissance, the pyramid complex of senwosret iii, dahshur, the pyramid complex of senwosret iii, dahshur: private tombs to the north, the pyramid complex of senwosret iii, dahshur: queens and princesses, the pyramid complex of senwosret iii, dahshur: temples, qin dynasty (221–206 b.c.), the qing dynasty (1644–1911): courtiers, officials, and professional artists, the qing dynasty (1644–1911): loyalists and individualists, the qing dynasty (1644–1911): painting, the qing dynasty (1644–1911): the traditionalists, the rag-dung, rare coins from nishapur, recognizing the gods, the rediscovery of classical antiquity, the reformation, relics and reliquaries in medieval christianity, religion and culture in north america, 1600–1700, the religious arts under the ilkhanids, the religious relationship between byzantium and the west, rembrandt (1606–1669): paintings, rembrandt van rijn (1606–1669): prints, renaissance drawings: material and function, renaissance keyboards, renaissance organs, renaissance velvet textiles, renaissance violins, retrospective styles in greek and roman sculpture, rinpa painting style, the rise of macedon and the conquests of alexander the great, the rise of modernity in south asia, the rise of paper photography in 1850s france, the rise of paper photography in italy, 1839–55, the rock-hewn churches of lalibela, roger fenton (1819–1869), the roman banquet, roman cameo glass, roman copies of greek statues, roman egypt, the roman empire (27 b.c.–393 a.d.), roman games: playing with animals, roman glass, roman gold-band glass, roman housing, roman inscriptions, roman luxury glass, roman mold-blown glass, roman mosaic and network glass, roman painting, roman portrait sculpture: republican through constantinian, roman portrait sculpture: the stylistic cycle, the roman republic, roman sarcophagi, roman stuccowork, romanesque art, romanticism, saint petersburg, saints and other sacred byzantine figures, saints in medieval christian art, the salon and the royal academy in the nineteenth century, san ethnography, sanford robinson gifford (1823–1880), the sasanian empire (224–651 a.d.), scenes of everyday life in ancient greece, scholar-officials of china, school of paris, seasonal imagery in japanese art, the seleucid empire (323–64 b.c.), senufo arts and poro initiation in northern côte d’ivoire, senufo sculpture from west africa: an influential exhibition at the museum of primitive art, new york, 1963, seventeenth-century european watches, the severan dynasty (193–235 a.d.), sèvres porcelain in the nineteenth century, shah ‘abbas and the arts of isfahan, the shah jahan album, the shahnama of shah tahmasp, shaker furniture, shakespeare and art, 1709–1922, shakespeare portrayed, shang and zhou dynasties: the bronze age of china, shoes in the costume institute, shōguns and art, shunga dynasty (ca. second–first century b.c.), sienese painting, silk textiles from safavid iran, 1501–1722, silks from ottoman turkey, silver in ancient egypt, sixteenth-century painting in emilia-romagna, sixteenth-century painting in lombardy, sixteenth-century painting in venice and the veneto, the solomon islands, south asian art and culture, southern italian vase painting, southern song dynasty (1127–1279), the spanish guitar, spiritual power in the arts of the toba batak, stained (luster-painted) glass from islamic lands, stained glass in medieval europe, still-life painting in northern europe, 1600–1800, still-life painting in southern europe, 1600–1800, the structure of photographic metaphors, students of benjamin west (1738–1820), the symposium in ancient greece, takht-i sulaiman and tilework in the ilkhanid period, talavera de puebla, tanagra figurines, tang dynasty (618–907), the technique of bronze statuary in ancient greece, techniques of decoration on arms and armor, telling time in ancient egypt, tenochtitlan, tenochtitlan: templo mayor, teotihuacan: mural painting, teotihuacan: pyramids of the sun and the moon, textile production in europe: embroidery, 1600–1800, textile production in europe: lace, 1600–1800, textile production in europe: printed, 1600–1800, textile production in europe: silk, 1600–1800, theater and amphitheater in the roman world, theater in ancient greece, theseus, hero of athens, thomas chippendale’s gentleman and cabinet-maker’s director, thomas cole (1801–1848), thomas eakins (1844–1916): painting, thomas eakins (1844–1916): photography, 1880s–90s, thomas hart benton’s america today mural, thomas sully (1783–1872) and queen victoria, tibetan arms and armor, tibetan buddhist art, tikal: sacred architecture, tikal: stone sculpture, time of day on painted athenian vases, tiraz: inscribed textiles from the early islamic period, titian (ca. 1485/90–1576), the tomb of wah, trade and commercial activity in the byzantine and early islamic middle east, trade and the spread of islam in africa, trade between arabia and the empires of rome and asia, trade between the romans and the empires of asia, trade relations among european and african nations, trade routes between europe and asia during antiquity, traditional chinese painting in the twentieth century, the transatlantic slave trade, the transformation of landscape painting in france, the trans-saharan gold trade (7th–14th century), turkmen jewelry, turquoise in ancient egypt, tutankhamun’s funeral, tutsi basketry, twentieth-century silhouette and support, the ubaid period (5500–4000 b.c.), ubirr (ca. 40,000–present), umberto boccioni (1882–1916), unfinished works in european art, ca. 1500–1900, ur: the royal graves, ur: the ziggurat, uruk: the first city, valdivia figurines, vegetal patterns in islamic art, velázquez (1599–1660), venetian color and florentine design, venice and the islamic world, 828–1797, venice and the islamic world: commercial exchange, diplomacy, and religious difference, venice in the eighteenth century, venice’s principal muslim trading partners: the mamluks, the ottomans, and the safavids, the vibrant role of mingqi in early chinese burials, the vikings (780–1100), vincent van gogh (1853–1890), vincent van gogh (1853–1890): the drawings, violin makers: nicolò amati (1596–1684) and antonio stradivari (1644–1737), visual culture of the atlantic world, vivienne westwood (born 1941) and the postmodern legacy of punk style, wadi kubbaniya (ca. 17,000–15,000 b.c.), walker evans (1903–1975), wang hui (1632–1717), warfare in ancient greece, watercolor painting in britain, 1750–1850, ways of recording african history, weddings in the italian renaissance, west asia: ancient legends, modern idioms, west asia: between tradition and modernity, west asia: postmodernism, the diaspora, and women artists, william blake (1757–1827), william henry fox talbot (1800–1877) and the invention of photography, william merritt chase (1849–1916), winslow homer (1836–1910), wisteria dining room, paris, women artists in nineteenth-century france, women china decorators, women in classical greece, women leaders in african history, 17th–19th century, women leaders in african history: ana nzinga, queen of ndongo, women leaders in african history: dona beatriz, kongo prophet, women leaders in african history: idia, first queen mother of benin, woodblock prints in the ukiyo-e style, woodcut book illustration in renaissance italy: florence in the 1490s, woodcut book illustration in renaissance italy: the first illustrated books, woodcut book illustration in renaissance italy: venice in the 1490s, woodcut book illustration in renaissance italy: venice in the sixteenth century, wordplay in twentieth-century prints, work and leisure: eighteenth-century genre painting in korea, x-ray style in arnhem land rock art, yamato-e painting, yangban: the cultural life of the joseon literati, yayoi culture (ca. 300 b.c.–300 a.d.), the year one, years leading to the iranian revolution, 1960–79, yuan dynasty (1271–1368), zen buddhism, 0 && essaysctrl.themev == 'departments / collections' && essaysctrl.deptv == null">, departments / collections '">.

ARTS - Herzberg: Writing Essays About Art

- Art History

- Current Artists and Events

- Local Art Venues

- Video and Image Resources

- Writing Essays About Art

- Citation Help

What is a Compare and Contrast Essay?

What is a compare / contrast essay.

In Art History and Appreciation, contrast / compare essays allow us to examine the features of two or more artworks.

- Comparison -- points out similarities in the two artworks

- Contrast -- points out the differences in the two artworks

Why would you want to write this type of essay?

- To inform your reader about characteristics of each art piece.

- To show a relationship between different works of art.

- To give your reader an insight into the process of artistic invention.

- Use your assignment sheet from your class to find specific characteristics that your professor wants you to compare.

How is Writing a Compare / Contrast Essay in Art History Different from Other Subjects?

You should use art vocabulary to describe your subjects..

- Find art terms in your textbook or an art glossary or dictionary

You should have an image of the works you are writing about in front of you while you are writing your essay.

- The images should be of high enough quality that you can see the small details of the works.

- You will use them when describing visual details of each art work.

Works of art are highly influenced by the culture, historical time period and movement in which they were created.

- You should gather information about these BEFORE you start writing your essay.

If you describe a characteristic of one piece of art, you must describe how the OTHER piece of art treats that characteristic.

Example: You are comparing a Greek amphora with a sculpture from the Tang Dynasty in China.

If you point out that the color palette of the amphora is limited to black, white and red, you must also write about the colors used in the horse sculpture.

Organizing Your Essay

Thesis statement.

The thesis for a comparison/contrast essay will present the subjects under consideration and indicate whether the focus will be on their similarities, on their differences, or both.

Thesis example using the amphora and horse sculpture -- Differences:

While they are both made from clay, the Greek amphora and the Tang Dynasty horse served completely different functions in their respective cultures.

Thesis example -- Similarities:

Ancient Greek and Tang Dynasty ceramics have more in common than most people realize.

Thesis example -- Both:

The Greek amphora and the Tang Dynasty horse were used in different ways in different parts of the world, but they have similarities that may not be apparent to the casual viewer.

Visualizing a Compare & Contrast Essay:

Introduction (1-2 paragraphs) .

- Creates interest in your essay

- Introduces the two art works that you will be comparing.

- States your thesis, which mentions the art works you are considering and may indicate whether the focus will be on similarities, differences, or both.

Body paragraphs

- Make and explain a point about the first subject and then about the second subject

- Example: While both superheroes fight crime, their motivation is vastly different. Superman is an idealist, who fights for justice …… while Batman is out for vengeance.

Conclusion (1-2 paragraphs)

- Provides a satisfying finish

- Leaves your reader with a strong final impression.

Downloadable Essay Guide

- How to Write a Compare and Contrast Essay in Art History Downloadable version of the description on this LibGuide.

Questions to Ask Yourself After You Have Finished Your Essay

- Are all the important points of comparison or contrast included and explained in enough detail?

- Have you addressed all points that your professor specified in your assignment?

- Do you use transitions to connect your arguments so that your essay flows into a coherent whole, rather than just a random collection of statements?

- Do your arguments support your thesis statement?

Art Terminology

- British National Gallery: Art Glossary Includes entries on artists, art movements, techniques, etc.

Lee College Writing Center

Writing Center tutors can help you with any writing assignment for any class from the time you receive the assignment instructions until you turn it in, including:

- Brainstorming ideas

- MLA / APA formats

- Grammar and paragraph unity

- Thesis statements

- Second set of eyes before turning in