- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The Student Body Is Deaf and Diverse. The School’s Leadership Is Neither.

More than 30 years after a groundbreaking protest at Gallaudet University in Washington, questions about leadership at a school for the deaf in Atlanta have been further compounded by race.

By Amanda Morris

Student protests over the hiring of a white hearing superintendent have roiled a school for the deaf that serves mostly Black and Hispanic students in the Atlanta area and have focused attention on whether school leaders should better reflect the identities of their students.

The Atlanta Area School for the Deaf, run by the Georgia Department of Education, is one of two public schools for the deaf in Georgia and serves roughly 180 students from kindergarten to 12th grade, about 80 percent of whom are Black and Hispanic.

Students protested the hiring, accusing the school and the Education Department of racism and disability-based discrimination against the deaf community known as audism. They noted that the school’s top leadership included no people of color or deaf people.

Two weeks later, the superintendent, Lisa Buckner, who has 22 years of experience as a teacher and administrator of deaf students and had most recently worked at the Education Department, resigned. The school has appointed an interim superintendent, who is also a white hearing woman, and is now searching for a permanent replacement.

Since the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis last summer, institutions across the country have grappled with questions of representation and leadership, often propelled by community protests. At the school in Atlanta, the demands echoed a 1988 student uprising at Gallaudet University, the federally chartered private school for the deaf and hard of hearing in Washington.

In that protest, which was viewed as a landmark moment for deaf people, students successfully pushed for the university’s first deaf president and drew attention to longstanding challenges faced by deaf people.

Activism since then, including a controversy that saw two board members at Gallaudet resign in 2020 while saying the school discriminated against Black deaf people in hiring and promotions, has increasingly evoked both race and disability. Three decades after the original Gallaudet protest, many in the deaf community say they are still fighting some of the same battles.

The protests in Atlanta followed the hiring of Ms. Buckner in September. She replaced the former superintendent, John Serrano, who resigned in May after four years working as the school’s first deaf Latino leader.

The Atlanta school said it interviewed every applicant who met minimum qualifications for the position. Meghan Frick, a spokeswoman for the Georgia Department of Education, said it “stands opposed to audism and other forms of prejudice.” She described Ms. Buckner as “an educational leader” who was “proficient” in American Sign Language, or A.S.L.

But current and former staff members say deaf employees and people of color were overlooked for promotions, and both staff and students have complained that Ms. Buckner’s knowledge of A.S.L. was poor. In the original job posting, sign language fluency was listed as a preferred, not required, skill.

Many student protesters felt like the new superintendent could not understand them and looked down on them, according to Trinity Arreola, 18, a protest leader.

“It’s like we’re going backward,” Ms. Arreola, a senior and the president of the Latino Student Union, said. “It’s like we’re going back to a time where deaf people were thought of as limited and incapable.”

The school’s top leadership consists of white hearing women filling the roles of superintendent and assistant principal. In the 2020-21 school year, 79 percent of teachers were white and 60 percent of teachers were hearing, according to Education Department data. Ms. Buckner declined to answer questions about her decision to resign or complaints from students and staff.

Since May, at least 12 other employees have quit the school. Many of those who quit were deaf, people of color, or both, according to one former agriculture teacher, Emily Friedberg, 50, who is white and deaf.

After 12 years working at the school, she said, she was pushed to quit in June — months before she found out who the new superintendent was — because of what she described as a “hostile” environment driven by white hearing leadership that she said “bullied” deaf staff and made inappropriate remarks about students of color.

Ms. Frick said the Education Department was not aware of incidents like these at the school. She said officials encouraged anyone with concerns to reach out to the Education Department leadership.

Though the Gallaudet protest paved the way for new education and employment opportunities for the deaf, schools for the deaf are still mostly led by hearing people and are seldom led by people of color who are deaf.

Of the 73 school leadership positions for 71 statewide K-12 schools for the deaf across the country, 46 are held by hearing people, according to Tawny Holmes Hlibok, a professor of deaf studies at Gallaudet. Among the 27 deaf school leaders — a number that she said has more than doubled from seven years ago — three are people of color.

Growing research shows that students perform better in school if they have role models who reflect their background.

“I notice that when I talk to deaf children at a school without a deaf leader and ask them what they want to be when they grow up, they often limit themselves,” Professor Hlibok said, adding, “When I ask them if they want to be a teacher or lawyer or nurse, they say they can’t because that job is for a hearing person.”

A 2019 report by the National Deaf Center found that 44.8 percent of Black deaf people and 43.6 percent of deaf Native Americans are in the labor force, compared with 59 percent of white deaf people.

Along with a lack of role models, many deaf students, particularly deaf students of color, are not adequately prepared for college because of a lack of early language support services and a lack of certified educational interpreters in public schools, said Laurene E. Simms, interim chief bilingual officer at Gallaudet.

Black deaf students obtain undergraduate, master’s or Ph.D. degrees at about half the rate of Black hearing students, and half the rate of white deaf students, according to another 2019 report by the National Deaf Center .

The loss of so many people of color on the Atlanta school’s staff has made many students feel less comfortable there, according to Katrina Callaway, 19, a senior. In the past, she said, she and her friends have confided in teachers who they can relate to about their problems, home lives and friends, but now “students don’t feel like there’s anyone they can open up to,” she said.

“When I try to open up to someone who hasn’t had the same experiences,” she said, “I’m not always sure if I can trust them, and I feel a lot of self-doubt.” She said that sometimes it seemed that white staff treated students differently based on their skin color.

More broadly, activists in recent years have complained about the “whitewashing of disability,” or how much it is largely seen through a white lens, despite statistics that show Black people are more likely to have a disability .

For example, media portrayals of those with disabilities and leadership of disability organizations skew white, according to Vilissa Thompson, a Black disabled activist who created the hashtag #DisabilitySoWhite on Twitter to draw attention to the issue.

Recently, Netflix’s “Deaf U” reality series focusing on Gallaudet College students was criticized for its lack of deaf women of color, even though less than half of the school’s students were white at the time.

Those broader issues raised the stakes at places like the Atlanta school.

Ms. Frick said the Georgia Department of Education was working to create leadership pathways for teachers and school staff.

Mr. Serrano, the previous superintendent, declined to comment on his experience with the Education Department, but he wrote in an email that he hoped the department would conduct an equitable and inclusive search for the next superintendent.

“It is my firm belief that students want and need a leader who ‘looks like them’ and who shares their experiences as deaf and hard of hearing individuals,” he wrote.

Amanda Morris is a 2021-2022 disability reporting fellow for the National desk. More about Amanda Morris

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

If online learning works for you, what about deaf students? Emerging challenges of online learning for deaf and hearing-impaired students during COVID-19: a literature review

Wajdi aljedaani.

1 University of North Texas, Denton, USA

Rrezarta Krasniqi

Sanaa aljedaani.

2 Cleveland State University, Cleveland, USA

Mohamed Wiem Mkaouer

3 Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, USA

Stephanie Ludi

Khaled al-raddah.

With the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, educational systems worldwide were abruptly affected and hampered, causing nearly total suspension of all in-person activities in schools, colleges, and universities. Government officials prohibited the physical gatherings in educational institutions to reduce the spread of the virus. Therefore, educational institutions have aggressively shifted to alternative learning methods and strategies such as online-based platforms—to seemingly avoid the disruption of education. However, the switch from the face-to-face setting to an entirely online setting introduced a series of challenges, especially for the deaf or hard-of-hearing students. Various recent studies have revealed the underlying infrastructure used by academic institutions may not be suitable for students with hearing impairments. The goal of this study is to perform a literature review of these studies and extract the pressing challenges that deaf and hard-of-hearing students have been facing since their transition to the online setting. We conducted a systematic literature review of 34 articles that were carefully collected, retrieved, and rigorously categorized from various scholarly databases. The articles, included in this study, focused primarily on highlighting high-demanding issues that deaf students experienced in higher education during the pandemic. This study contributes to the research literature by providing a detailed analysis of technological challenges hindering the learning experience of deaf students. Furthermore, the study extracts takeaways and proposed solutions, from the literature, for researchers, education specialists, and higher education authorities to adopt. This work calls for investigating broader and yet more effective teaching and learning strategies for deaf and hard-of-hearing students so that they can benefit from a better online learning experience.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has largely affected the education sector, and in particular deaf education. According to Krishnan et al. [ 1 ], various measures to reduce the spread of the disease have led academic institutions to unprecedented changes to their academic activities. For instance, to comply with the social distancing requirement, most schools transitioned to online learning, while some have been forced to temporarily shutdown if such technology was unavailable [ 2 ]. Although these measures have significantly reduced the spread of the virus, they have also introduced several challenges, severely impacting the educational systems worldwide.

Deaf education has been facing a unique set of challenges during COVID-19. To start with, distance learning platforms were quickly adopted mainly for non-disabled students, since they represent the mainstream [ 3 ]. Despite their absolute right to access information, deaf students were initially left out of distance learning under the justification of them constituting a hard to manage population, requiring more specialized educational approaches [ 4 ]. In general, the social distancing measures have led to the exclusion and isolation of deaf students, from instructors who could not promptly respond to their educational needs [ 1 ]. In addition, deaf students have experienced significant difficulties with information sharing. These issues include inadequate access to sign interpreters, loss of visual cues, auditory signal issues arising from the use of face masks, lack of transcripts or captions to lectures, etc. [ 5 ]. As noted by Swanwick et al. [ 6 ], the United Nations [ 7 ] made a declaration titled “Disability-Inclusive Response to COVID-19”, which acknowledged that people with disabilities took the hardest hit during the pandemic and their education requires immediate assistance.

While existing literature has focused on improving accessibility for disabled students in higher education, the pandemic has exposed critical weaknesses of e-learning systems for students with special needs that may need to be addressed. One way to strengthen virtual education is to identify challenges and barriers that appeared during the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the major concerns that students with disabilities had to cope with was adjusting to a completely new format of remote learning and instructions [ 8 – 10 ]. With the strict regulations that all students had to comply with, students with disabilities, in general, and deaf students, in particular, were the most to suffer from them [ 2 , 11 – 13 ]. The goal of this paper is to review and expose the major challenges that deaf students were facing during the pandemic. We start with reviewing all research papers that were written as a response to these challenges; then, we analyze them to extract and categorize all the highlighted problems. Given that several studies have identified those challenges, our research aims to systematically collect and categorize them. This study reviews 34 papers, to extract challenges and their corresponding key mitigation plans.

Reviewing literature on the challenges facing deaf education during the current pandemic can provide solutions to e-learning beyond the pandemic. Previous studies have focused on general e-learning experiences, such as Mseleku [ 14 ], while others have looked at accessibility to online education by generally disabled students [ 15 ]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper to review the literature related to accessibility challenges in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The contributions of this paper are:

- A literature review of 34, peer-reviewed, deaf and hearing-impaired publications related to deaf students education during the COVID-19 pandemic, to provide a catalog for future research in this area;

- An exploration of the challenges faced by deaf and hearing-impaired students during the COVID-19 pandemic;

- Key takeaways extracted from the reviewed studies, for researchers and educators, to improve the learning experience of deaf students;

- A replication package of our survey for extension purposes [ 16 ].

This literature review study is structured as follows: Sect. 2 surveys prior work on technological platforms in education and challenges of deaf and hard-of-hearing students. Section 3 outlines our research questions. Section 4 provides an overview of the methodology used in this study to investigate the challenges of deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Section 5 explains our research findings, and Sect. 6 discusses our results. Finally, Sect. 7 highlights the limitations of our research, and Sect. 8 summarizes our conclusions and future work directions.

Related work

Deaf community.

In contrast to hearing individuals, a larger percentage of deaf individuals had difficulty trusting, understanding, and accessing COVID-19 information [ 17 ]. The arrival of COVID-19 disrupted a large volume of sectors around the world. Given the substantial number of government and public health announcements concerning COVID-19, information about the virus was communicated in an irregular and inconsistent manner, putting specific communities at an elevated risk. Due to language isolation, the deaf community, in particular, found it difficult to obtain information about COVID-19 [ 18 ]. Deaf individuals typically experience challenges in acquiring health information, resulting in substantial disparities in health knowledge and discrepancies in preventative health care [ 19 ], and this gap has increased during the COVID-19 epidemic. For example, in the beginning of the epidemic, the sign language related to COVID-19 was inadequately established, resulting in misinformation and confusion [ 20 ]. As the media started intensively focusing on the virus, the World Health Organization (WHO) failed to deliver a conventional sign for COVID-19, leaving this responsibility to deaf communities. Thus, a multitude of pandemic-related signs were created throughout the world [ 21 ]. For instance, the Brazilian deaf community used more than three signs for the virus, leading to uncertainty. As it was initially assumed that COVID-19 was transferred from bats, one approved sign for COVID-19 in Brazil was a hand gesture that resembled a bat bite. According to the authors of the study, this sign generated an unintended fear of animal bites and misperceptions about the genuine risk of COVID-19 transmission [ 21 ]. In fact, the risk of contamination and transmission of infection might be elevated owing to the linguistic discrepancies across global Deaf communities.

Moreover, the frequent usage of face masks during the pandemic also impacted the lives of deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) individuals, as many of them rely on lip-reading as a way of successful communication with hearing individuals. However, the ability to lip-read is hampered by wearing face masks. Grote and Izagaren [ 22 ] highlighted the detrimental impact on adaptability of the Deaf community in the UK owning to the “#MaskforAll” social media campaign. Even the substitutes for face masks such as transparent face masks are inconvenient to obtain and do not meet the medical standards. The authors concluded that the widespread use of face masks poses a major threat of isolation to the Deaf community, not only in the UK but to Deaf communities across the world.

Deaf education

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the world was presented with several barriers in various areas, including the educational sector. An abrupt and unexpected shift of the learning system to distance learning brought with it new obstacles. Alcazar et al. [ 23 ] highlighted the significance of speech-to-visual approach incorporated into distance learning systems as it enables the understanding of material and addresses the individual needs of deaf students.

On the contrary, Baroni and Lazzari [ 24 ] investigated the distance learning experiences of deaf students and revealed that translation, technical, and time problems posed a severe challenge. The teachers and students have faced difficulties adjusting to distant learning at all grade levels and courses [ 25 ]. A study examined the response of the Caribbean education system to the COVID-19 pandemic and concluded that, in addition to the struggle of teachers and students to adapt to remote learning, the courses were not designed to be taught remotely [ 26 ].

The World Federation of the Deaf (WFD) stated that learning materials that are available online might not be intended for deaf students, the accessibility of the internet for some families might be limited, and they might lack the availability of visual and linguistic input [ 27 ]. Moreover, the absence of linguistic support can cause difficulty for deaf students to decode a language [ 28 ]. E-learning might promote inclusive strategies, for instance, providing a written transcripts of classes or captioned videos; however, the complexity of written language might be incomprehensible to the students [ 29 ]. WFD [ 27 ] highlighted that deaf students are expected to learn from homes where sign language is rarely practiced. Moreover, with e-learning, deaf students can be removed from deaf schools with a sign-rich environment. Therefore, with e-learning, the education system for deaf students is at risk of the linguistic barrier due to insufficient availability of sign language [ 30 ].

Pacheco et al. [ 31 ] investigated the difficulties of providing instructional accommodations for students with disabilities in schools during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many deaf students lack the necessary instructional attention in distance learning [ 32 ]. Replication of physical attention provided to deaf students at schools is not possible at homes with prevalent accessibility issues. Another profound problem that hinders the effectiveness of distance learning is improper training of teachers [ 31 ]. In distance learning, students learn in a group format. Therefore, this setting lacks the individual attention needed for deaf students. More importantly, the communication gap, due to the inappropriate handling of physical gestures, significantly hinders students’ learning curve. Even parents’ involvement in such classes was found to be difficult for a regular learning process to be sustainable [ 33 ]. In addition to the difficulties faced by deaf students, their families also deal with critical issues such as technical support and accessibility of the learning environment. Sommer [ 34 ] conducted a study in the USA and revealed that inaccessibility of information for deaf students during the COVID-19 pandemic had a severe emotional impact on them. In a survey by Krishnan et al. [ 1 ], the authors found unfamiliarity with hearing devices, online devices, distractions are the main difficulties DHH students are facing with e-learning platforms.

E-learning platforms

The evolution of technology has greatly improved the education sector, especially with the introduction of learning management systems (LMSs). According to Iqbal [ 35 ], an LMS is a learner-centered technology that focuses on the logistics of managing learners, distribution of learning content, enables interactions between learners and teachers, among other functions. As defined by Dobre [ 36 ], LMSs can be considered as “a set of software platforms, delivered to users by instructors through internet and by the use of various hardware means, having as purpose the delivery in the shortest time possible a high level of knowledge into a domain assuring in the same time a full management of the entire educational cycle, including data and information.” Such a definition provides an elaborate explanation of the purposes of LMS and also shows why the systems have become very crucial in the COVID-19 pandemic when social interactions have been curtailed.

As indicated by Oliveira et al. [ 37 ], LMS systems emerged in the 1990s when the first web browsers were developed and have been greatly improved since then. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Mtebe [ 38 ] indicates that LMS was used either to supplement face-to-face instruction, or to facilitate distance education for students who could not access physical classrooms. However, Alqahtani and Rajkhan [ 39 ] indicate that, due to the current pandemic, many institutions have been forced to shut down and offer learning through LMS. There are a large number of LMSs that are currently in use, but the most common are: Blackboard, canvas, Moodle, among others [ 40 ]. Thus, educational systems adopt LMS depending on their needs, functionalities, and preferences. Batanero et al. [ 41 ] found that integration of the Moodle learning platform enhanced the performance of deaf students by 46.25%. According to Batanero-Ochaíta et al. [ 42 ], the deaf students showed constructive attitude toward Moodle learning platform; however, their perceptions varied on the ease of use and complexity of the platform.

Rather than simply making online course materials more accessible, additional practices must be ingrained in the university settings that convey comfort and safety [ 43 – 45 ]. Alshawabkeh et al. [ 46 ] suggested a formal IT training with an interpreter for the deaf students prior to using LMS.

Research questions

This study aims to explore the barriers of deaf and hard-of-hearing students in education during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study may help identify and critically expose the wide range of concerns and difficulties faced by deaf students during the pandemic. Furthermore, our literature review findings may serve as a comprehensive source for improving the deaf education. Specifically, we investigate the following Research Questions (RQs):

RQ 1 : What challenges and concerns are deaf and hard-of-hearing students in higher education facing with an online education during the COVID-19 pandemic?

RQ1 investigates a series of challenges and concerns during remote learning that deaf and hard-of-hearing students had to endure on the rise of the COVID-19 pandemic. We will explore more in-depth the findings related to recently published work in this domain and discuss implications since COVID-19 emerged as a global humanitarian problem.

RQ 2 : What are emerging solutions to better handle challenges faced in deaf education during the COVID-19 pandemic?

RQ2 investigates the extent to which emerging in-demand solutions can be proposed to overcome some of the major barriers pinpointed in RQ1. At a larger schema, these solutions can serve as a mediating, non-perfunctory source of information to cope better with remote learning. It will shed light on alternating strategies and guidelines that could facilitate deaf and hearing-impaired remote learning, and methods that could be implemented within institutions globally for a more efficient remote learning.

Methodology

This present research is a literature review. It explores the existing most up-to-date scholarly sources relating to the subject of the research to answer the research questions. The objective is to explore the key challenges of the deaf and hearing-impaired in education during the COVID-19 pandemic. This section is divided into the three phases followed when selecting relevant publications: planning, execution, and synthesis. Each of these steps is explained in the following sections.

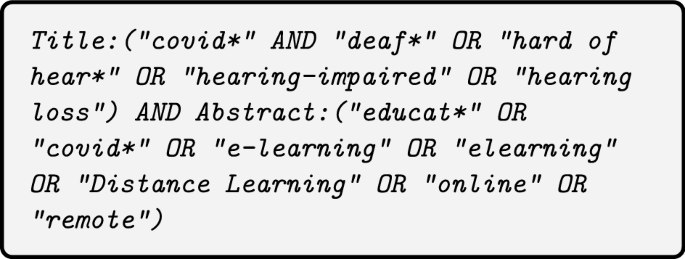

This step entailed refining our search strategy for literature. In line with the literature review methodology, we formulated a set of keywords related to our study, which we searched on various digital repositories.

Search keywords

We conducted a pilot search [ 47 ] to guide our formulation of search keywords in two repositories: ACM and IEEE. We wanted to identify the synonyms and words that are used when describing the barriers to deaf education during the COVID-19 period. Therefore, our search was restricted to the abstracts and titles only. Such a strategy helped in avoiding false positives. The search string used is as follows:

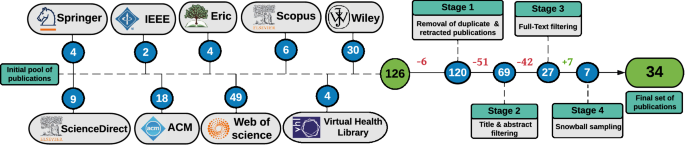

Digital libraries

A literature search was carried out in the following libraries: Scopus, IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, Web of Science, Springer Link, Virtual Health Library, Wiley, ERIC, and Science Direct. We selected the nine libraries in order to ensure maximum coverage of the topic so that no important study was left out and utilized by similar studies (e.g., [ 48 ]). The various libraries queried are provided in Table 1 . The libraries contained studies related to ours and in the fields of hearing-impaired education.

Overview of targeted digital libraries used to collect published work

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

These criteria were useful in filtering and pruning our search results so that we were only left with those publications that were aligned with our study. For example, it was essential to ensure that we got studies in the education context and written in English while excluding those in the medical area and not peer-reviewed. We also included papers that were available in digital format and published during the COVID-19 period. The inclusion/ exclusion criteria are given in Table 2 . Although we aimed at a final pool of relevant papers, the initial search results helped in manual filtering to evaluate the appropriateness of the studies for our research. For example, it was crucial to know the kind of obstacles they identified. Regarding the time frame, we restricted it to 2020, 2021, and 2022, which are the years that have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Backward/forward snowballing

We undertook snowballing to add valuable articles to the ones we had obtained using automated search. According to Wohlin [ 49 ], snowballing involves reviewing papers that have emerged for a literature search and identifying articles that have cited the given paper (forward snowballing) or those that have been cited in the paper (backward snowballing). We conducted the snowballing in a closed recursive manner to make it more effective. As a result, we got a total of 10 articles from snowballing, from where we selected 7 that met our selection criteria. Finally, we included the articles from the snowballing activity to make our final count of 34 articles.

Exclusion during data extraction

Researchers can still eliminate some of the selected articles even at the data extraction stage. Such a situation occurs when the researcher discovers that a paper is a duplicate of another or meets the exclusion criteria. For example, we had an article that provided general information about communication obstacles during COVID-19 without focusing on deaf students [ 50 ], while another took a medical perspective instead of an educational one [ 51 ].

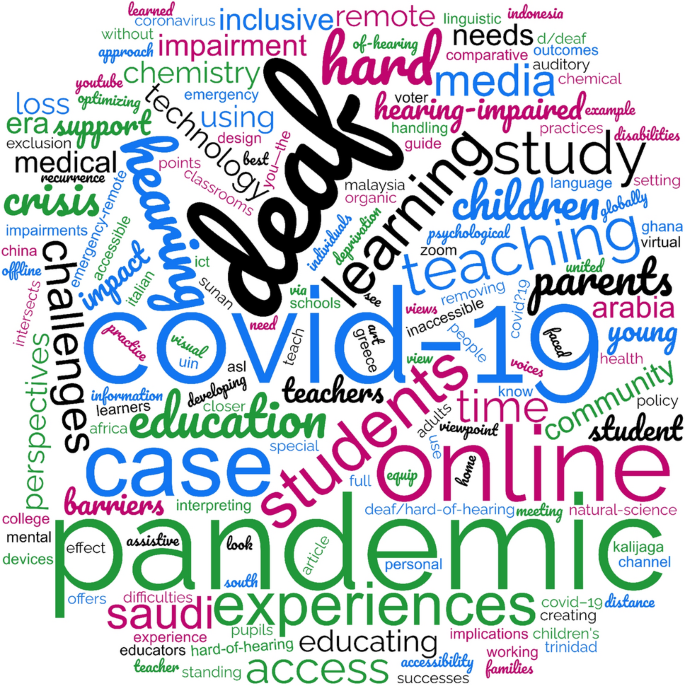

This section depicts the search results from the various digital libraries. The first search in all nine repositories gave a total of 126 articles. After that, we used four stages to evaluate the most relevant publications to our study. The first stage involved removing duplicate and retracted publications, where 6 articles were eliminated, and 120 publications proceeded to the next phase. The second stage was the title and abstract filtering, where we utilized our inclusion and exclusion criteria. In total, we removed 51 publications and allowed 69 to move to the next phase. For instance, the application of our inclusion and exclusion criteria led to the elimination of grey literature, non-peer-reviewed materials, and articles published before 2020, among others. The third stage was full-text filtering, which led to the removal of 42 articles and allowing 27 to move to the next phase. The final stage involved performing both forward and backward snowball sampling [ 49 ] that led to the addition of 7 articles. In total, 34 articles were selected for further analysis. Figure 1 shows the search execution process. Finally, we presented the titles of the 34 papers illustrated in the form of a word cloud as depicted in Fig. 2 .

Overview of publications filtering process

Word cloud of the titles of the selected papers

During the synthesis phase, we examined the collected data with regard to how they could meet our research objectives. We classified the articles according to their country of origin and year of publication in order to understand where and when the barriers to deaf education were experienced. We ensured that every study was thoroughly scrutinized for concrete evidence and that all facts were provided. Careful examination was done to collect all data related to deaf education obstacles during COVID-19. For each study, we extracted the disability type such as deaf, hard-of-hearing, or hearing impairment, the year of publication, study methodology, source of information, approach of collecting data, participant type (i.e., teachers, students, leaders), study sample size, and study location.

To reduce bias in our data, we utilized a peer-review strategy, where all researchers reviewed the data, and any points of contention were discussed. The data was transferred to a Google Spreadsheet to ensure the collaboration of all the authors was in sync during the research. It is important to state that three of the authors were familiar with the scope of studies and have made similar publications and contributions in the past [ 52 – 56 ].

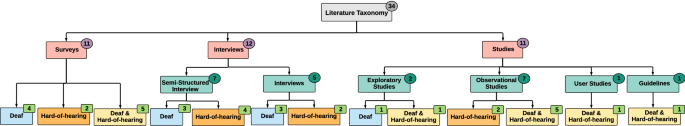

This section reports the findings that we obtained by synthesizing various articles according to the scope of two research questions asked in this study. We analyzed a total of 34 articles. We report the characteristics of this set of studies extensively in Table 3 . The data collected from this set of studies ranged from 2020 to 2022. The types of methods that these studies carried out are represented via a taxonomy as depicted in Fig. 3 . The figure provides a grouping of all the studies according to the methodology and methods used in the studies and the focus of the studies. From the figure, the most notable and common studies were those conducted in the form of surveys, interviews, and observational studies. The most common artifacts used to carry out those types of studies included social media, questionnaires, phone interviews, and other related documents such as guidelines. Regarding the focus of the studies, the most popular target groups in the surveys, interviews, and other studies were hard-of-hearing and deaf. Using the literature taxonomy, we were able to overview the studies we selected.

Overview of literature taxonomy of the selected research papers in our dataset. It highlights the methodology used and the targeted user group

Detailed information regarding the 34 papers selected: these publications report major challenges that students with special needs, specifically deaf and hard-of-hearing students faced in academic institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic

The publications are categorized by year, user, methodologies, affiliations, sample size, and location

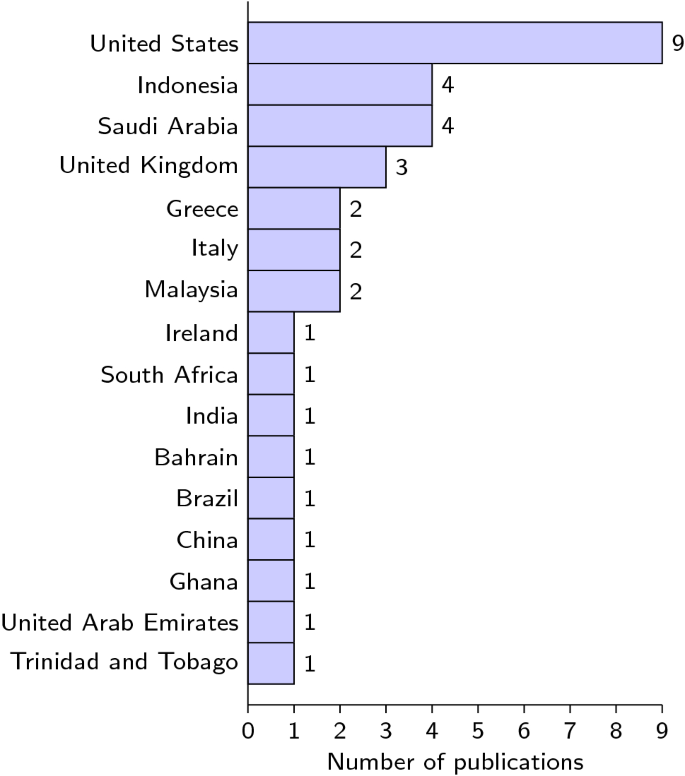

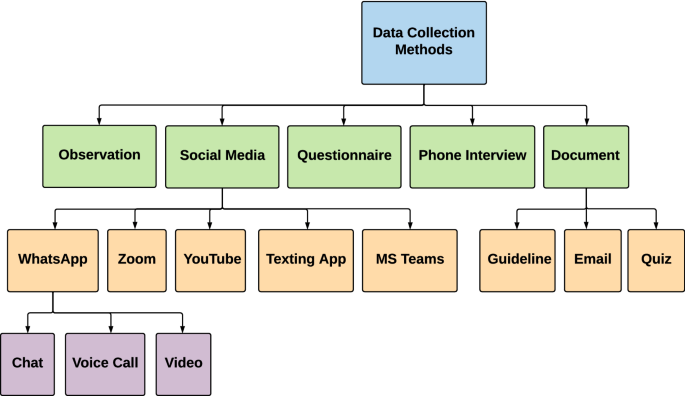

In Fig. 4 , we wanted to establish the country of origin from which the studies were done. According to the collected data, we notice that most of the studies were conducted in the USA. The second-highest number of studies originated from Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, the UK, Greece, Italy, and Malaysia, with all other countries having one study each. Such findings can help motivate scholars from countries with few or no studies to research deaf challenges in their locations. Figure 5 shows an overview of the types of the dataset used across all the 20 studies. It is evident from the figure that social media was the most common and diverse data collection method that was used in the studies. It is possible to speculate that most researchers used social media platforms because of their popularity and because their use has not been affected by the social distancing measures implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic. The extensive use of technology during the pandemic, especially in education, also means that students with learning disabilities faced all kinds of challenges of different ranges from the unsuitability of technologies to health matters. That does not rule out the fact that similar challenges were not observed in other countries such as Indonesia or Italy and other countries. In fact, we noticed that the types of challenges that deaf students experienced were almost uniform across countries. It is important to place our findings within the context of the two research questions that we developed in this study.

Distribution of publications across countries

Overview of types of dataset used across 20 studies

In this research question, we wanted to identify the issues that deaf students were facing during the pandemic. From our findings, we categorized the challenges into four categories: technological; educational; accessibility; and usage issues, and health-related.

- Technology-related challenges Our main focus was to explore how technical issues affected deaf education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Deaf education faced four challenges: unavailability of hearing devices, disruptions during online lessons, and lack of familiarity with the online devices [ 1 , 11 , 57 – 59 ]. It is noted that the challenges in deaf education during COVID-19 can be grouped into three groups: technological, organizational, and methodical [ 60 , 61 ]. Technological challenges are those related to accessibility; organization depends on the collaboration between teachers, while methodical indicates how the instructions were taught. Mohammed [ 62 ] pointed out that video quality, internet stability, and language modality posed major technological barriers to distance learning for deaf students. Aljedaani et al. [ 63 ] presented the challenges faced by deaf students in distance learning and found that among 8 of the participants, 96.9% faced issues with internet connectivity at home and 72% of the responses showed inaccessibility of the content. Our interpretation of the aforementioned challenges is as follows: While students in general picked up quickly using new technology [ 64 ], this was not regarded as a doable option for students with disabilities [ 2 ]. On the contrary, they were faced with a series of challenges with the setup of the technology. First, the students with disabilities found it challenging to use the recommended technology. That was primarily because the interfaces of the software and applications were not designed to accommodate students with hearing disabilities [ 65 , 66 ]. Second, students experienced enormous challenges adapting the use of video conferencing for synchronous lectures [ 61 , 67 ]. Third, it was overwhelmingly difficult for students with hearing needs to follow conversations with multiple signers communicating simultaneously [ 11 , 68 , 69 ]. The lack of simultaneous translation was also one of the major obstacles to address [ 61 ]. Finally, delays in mainstream and remote classroom setup while interacting with deaf students or asking questions were a significant problem (since deaf students use sign language to ask questions), which the translator then interprets to the instructor [ 70 , 71 ]. The findings of Alqraini and Alasim [ 72 ] highlighted deaf students’ lack of focus during classes, as they choose to play games on their devices instead of paying attention to the ongoing lesson. We believe that such issues require solutions to facilitate deaf education.

- Education system-related challenges We also aimed to identify those challenges that were related to learning and the educational system. We found that, while most of the students got adjusted fairly quickly to the remote online system [ 73 ], this became a huge barrier, especially for deaf students [ 72 , 74 ]. Even in a typical classroom setting, d/DHH students generally attend classes with the support of a special education team due to their special needs [ 75 ]. However, working from home, this new adjustment, in reality, created substantial barriers for deaf and hard-of-hearing students [ 3 ]. Researchers [ 46 , 59 , 76 ] underscored that the lack of sign language interpreter hinders the understanding of deaf students with inadequate vocabulary knowledge. Even though the interpreters were present during the online classes, however, due to small visuals, it became challenging for the students to understand. Alsindi et al. [ 77 ] highlighted that in addition to miscommunication between teacher and student, the lack of interpreter’s knowledge regarding art and design hindered the performance of students. Deaf students have also suffered from a lack of access to education and welfare services, such as inadequate sign language interpreting avenues, the difficulty of lip-reading when teachers are wearing masks, limited direct support by teachers, among others [ 58 , 78 – 80 ]. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened social exclusion among deaf students, especially with the disruption of daily interactions with other people, lack of access to information, and inadequate sign language interpreters [ 6 , 61 ]. The exclusion is caused by lack of internet access, poor infrastructure, poverty that impedes lack of access to high-quality educational materials, barriers relating to lack of accessible learning management systems (LMSs), inability to use the LMS to access the content, and LMSs that do not cater for the needs of deaf students [ 2 ]. Deaf education in some countries has been affected by a lack of resources in public schools, unpreparedness among teachers of deaf children, greater exclusion, and obstacles such as lack of real-time transcription services, technical issues, and unavailability of subtitles on videos [ 3 , 58 , 72 ]. The suggested problems call for improvement of the education system to make it more conducive to deaf education.

- Physical accessibility challenges Adequate, accessible experience for students with hearing disabilities was an unattainable goal [ 59 , 61 , 81 ], even though distance learning equipment and technologies such as video-conference technologies, different websites, electronic platforms, applications, and/or various databases became available for most disabled students [ 9 , 82 ]. This was not the case for underdeveloped countries [ 83 ]. Furthermore, some students with hearing disabilities lived in areas where there was hardly any access to the internet [ 13 , 84 ]. To add another layer of barriers, some students with disabilities did not possess even basic technologies [ 79 ]. Hence, without physical attendance, remote learning for students with auditory access needs became a huge struggle for students with disabilities [ 81 ]. We also established that, during the current pandemic, wearing masks seemed to have become the major impediment for students who were deaf or with hearing impairments [ 85 ]. Indeed, face masks became the worst enemy for hard-of-hearing and deaf students. Most importantly, a cloth face mask inhibited speech reading and blocked muffling sound [ 81 ]. They even prevented students from reading lips. The other concern pertained to both audibility and intelligibility of speech. Due to the wearing of masks, students with hearing issues found the teachers voices completely diminished through the use of masks and shields [ 86 ]. This made the student–instructor communication poor and inaccessible. Physical distance also became a significant obstacle between students and faculty only because this unconventional communication reduced speech audibility and intelligibility [ 12 , 87 ].

- Health-related challenges The other most critical challenge pertains to the mental health of disability students [ 88 ]. Students with hearing disabilities showed four times more than other students increased symptoms of anxiety, depression, and emotional challenges compared with the general population [ 89 ]. We established that some health-related issues that emerged during and before the pandemic were affecting deaf education. For instance, deaf students have faced emotional challenges due to isolation from their classmates and lack of access to important information during the pandemic [ 34 , 90 ]. The fact that most deaf students have experience impractical delays has also led to emotional and social issues among them [ 1 , 70 ]. All these challenges have led to numerous mental health problems and unforeseen psychological impacts [ 91 ].

In this section, we will discuss the proposed solutions to the most prominent issues that have been identified in the previous section. The technology used in deaf education must ensure that the audio is clear and with self-explanatory images, the activities taught should be easy due to the online learning challenges, and there should be concerted efforts from all stakeholders [ 60 ]. Furthermore, deaf students should be given mental health services, training on pragmatic skills, be provided with hearing aids, be encouraged to read, and also be facilitated to gain information during the pandemic [ 1 , 34 , 70 , 90 ]. It is also recommended that parents look for suitable online educational programs, find opportunities for exposure to deaf students, communicate with deaf and hard-of-hearing students, enable deaf and hard-of-hearing students to socialize, and assist them in getting the services they need [ 92 ]. A combination of government-led and community-led responses has also provided greater educational and social support for deaf students [ 78 ]. It is also proposed that recognition of group rights will lead to greater inclusion for deaf students, so that cultural and linguistic accessibility can be offered to the population [ 6 ]. For example, sign language should be considered and recognized as a language like any other.

It is also important to develop videos with captions and interpretations, whether offline, online through YouTube or cloud-based Zoom recordings, which are especially useful to the deaf community [ 8 , 10 , 58 , 72 , 74 , 82 , 93 ]. An important aspect of the videos is that they must be thoroughly tested for validity to ensure their effectiveness, and revisions are done in order to improve the quality of the videos. Sutton [ 10 ] also notes the importance of providing interpreters and speech-to-text capabilities for deaf students during the pandemic to aid their learning. It is suggested that governments should utilize inclusive educational models, improve the accessibility of deaf students to various services, provide deaf-friendly masks, expand television programming, and hire more teachers in order to have a favorable number of staff assisting deaf students [ 3 , 79 ]. Low-income families should be given financial assistance to purchase electronic equipment for their children as recommended by Alqraini and Alasim [ 72 ]. The authors also proposed that a quiet environment should be created for the students during their lessons. [ 62 ] suggested the provision of standard educational technologies to teachers and students, proper training of teachers [ 46 , 57 , 84 ], hosting workshops concerning deaf culture, and video translation of textbooks in sign language to ensure the effectiveness of distance learning.

Karampidis et al. [ 94 ] recommended that distance learning platforms should be integrated with “Hercules”, a bidirectional translator that translates five languages, including Greek, Cypriot, British, German, Slovenian, and Portuguese, to their respective sign languages and vice versa. Institutions must incorporate a better approach to provide accessible technology that individuals with diverse needs can adapt during the pandemic [ 63 ]. Another study [ 95 ] suggested the use of ICT (Information Communication Technology) to conduct online classes in the pandemic. The uninterpreted-learning ICT models were preferred by the participants of the case study [ 84 ] over Zoom classes. Mathews et al. [ 96 ] stated that to address the communication gap in distance learning, interpreters have had to employ a variety of specialized expertise, interact with one another, and actively involve both their hearing clients and deaf communities in diverse settings. The study also recommended vocabulary development of the interpreters to convey the lessons more conveniently. Alshawabkeh et al. [ 46 ] suggested that deaf students must be trained by an IT professional with a sign language interpreter prior to initiation of distance learning. Students, teachers, and interpreters should collaborate in order to present material simultaneously. They also proposed that teachers involve deaf students in planning the online class before it begins. Institutions should continuously evaluate the deaf student’s feedback to enhance the quality of distance learning. Moreover, the existing LMSs must be provided with additional features for the DHH students [ 77 ].

Our study has also shown that governments should also put in place inclusive emergency plans and improve access to telecommunication services such as the internet to deaf students [ 2 ]. It is also proposed that policy changes should be made to enable deaf adults to participate in early intervention teams and greater collaboration from multi-agency teams in order to have professional teams working toward inclusion and education of deaf children in the pandemic [ 9 ]. Deaf students should have a conducive environment at home, support from parents, online instructional content, access to specialist support, and good access to instructions to mitigate the connectivity challenges [ 11 , 81 ]. It is evident that collaborations from a wide range of stakeholders will provide the necessary support and resources needed for improving deaf education.

Our literature review provides an elaborate overview of the challenges that deaf students have been facing in education during the course of the current pandemic. Furthermore, we also reviewed potential solutions that can be enforced and incorporated by different authors. In this section, we provide notable takeaways from our study.

Takeaway 1: Provide necessary equipment and technology We have established that a lack of equipment such as hearing aids and inaccessibility to the internet are major obstacles impeding deaf education in the COVID-19 pandemic. The problem is worse in rural areas and those with high levels of poverty [ 2 ]. As further indicated by Paatsch and Toe [ 70 ], global research has shown that many deaf students attend mainstream classes that do not have adequate support for the difficulties that such students face. It has also been demonstrated that deaf students face challenges when using Zoom platforms, especially given that the platform has a steep learning curve and its features are not easily understood by all students [ 11 ]. One of the technologies lacking for many deaf students is Remote microphone (RM) hearing assistive technology (HAT), which should be customized to the needs of every student [ 81 ]. It is important to address such issues in order to promote remote deaf education during the current pandemic.

Takeaway 2: Improve accessibility and usage of learning materials We have noted that many institutions have digitized their content; however, it is still inaccessible due to lack of captioning and unclear audio, among other issues. Such a finding is consistent with Fernandes et al. [ 93 ], who found that learning materials for deaf students should meet the validity and effectiveness so that they can be of help to deaf students. However, it is not translated even when such content is accessed, and there are no speech-to-text services. Furthermore, deaf students find it hard to follow the teacher during virtual classes, when several faces are appearing on the screen simultaneously, or when captions’ speed is fast [ 92 ]. The lack of self-explanatory images, presence of background music, and inclusion of unnecessary decorative details also make the accessibility of learning materials difficult [ 60 ]. It is important to provide visual materials and techniques that will help deaf students learn more effectively [ 61 ]. Another accessibility challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic is that the use of face masks by teachers on online platforms makes it hard for deaf students to read lips, which is a major challenge in their learning that should be overcome by using clear masks [ 10 ]. The provision of accessible learning materials will be very important in improving deaf education.

Takeaway 3: Improve collaboration and partnership It has been clear that all stakeholders should be involved in improving deaf education. The proposed solutions indicate the important role played by the government, teachers, parents, and specialists in improving education outcomes for deaf students. Using the example of Saudi Arabia [ 2 ], governments can play a crucial role to help in creating a conducive environment for deaf education. Furthermore, in Italy, Tomasuolo et al. [ 78 ] explain the crucial role of stakeholder lobbying by deaf organizations such as the World Federation of deaf (WFD), the Italian National Deaf Association, among others. It is noted that collaboration between deaf community members, deaf organizations, scholars, and activists in many countries around the world has led to greater access to education, improved use of captions, greater use of Text apps, broadcasting of content that considers the deaf community, utilization of clear masks, among others [ 9 , 79 ]. Therefore, such collaborations and partnerships provide important opportunities for improving the quality of deaf education in the current pandemic.

Takeaway 4: Cater for the mental health needs of deaf and impaired students We have found that some students developed mental health issues during the pandemic, while others already had them prior. As explained by Krishnan et al. [ 1 ], such a situation has been brought about by the social distancing and related protocols during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has added to their isolation and lack of social interactions. Swanwick et al. [ 6 ] indicate that deaf students faced social exclusion even before the pandemic, but the current situation has exposed and deepened the issue. The pandemic has also led to negative emotional responses from deaf students because the pandemic has led to the school closing, fear of illness, social distancing, among other family problems [ 34 ]. It has been noted that deaf students are psychologically resistant to the effects of the pandemic but show less mental resilience compared to normal hearing students [ 90 ]. Providing counseling and psychological services is crucial.

Takeaway 5: Simplify the LMSs Our study has shown that the mere availability of the LMSs does not guarantee quality online education for deaf students. Indeed, the switch to online learning has been abrupt due to COVID-19, and most deaf students faced tremendous challenges in accessing the content on LMS platforms [ 2 ]. It has also been observed that there were predominant challenges in ensuring an uninterrupted-learning environment via video conferencing, for example, whether Zoom could adequately display LMS-located content or not [ 74 ]. Such systems need to be simplified and customized to improve their usability features and look and feel for deaf students. LMSs are extremely important for remote access to materials and learning for deaf students. The suggestion for their simplification is a crucial takeaway that should be taken into account so that deaf and hard-of-hearing students can fully take advantage of such platforms.

Recommendations for future research

- Future researchers may investigate the techniques of refining LMSs to improve their accessibility. Such a proposition is made because this study has established that many deaf students are unable to fully take advantage of LMS systems [ 63 ]. Potentially, scholars may look at improving the functionality of such systems, customizing them to meet the needs of individual students, and simplifying their navigation.

- Scholars can investigate how mental health issues among deaf students can be mitigated. It is apparent that deaf students are facing a hard time during the pandemic, and the inability to cope can lead to stress. Researchers can investigate the possible ways of addressing the educational and socioeconomic factors that should be addressed so that such students have peace of mind and better mental health outcomes.

- It would also be important to explore how stakeholder engagement can be improved to harness their efforts to help deaf students. It has been established in this study that the roles of various stakeholders are very important in ensuring quality education for the deaf. Other scholars may utilize stakeholder engagement models and frameworks to explain how such stakeholders can work with each other collaboratively so that the learning outcomes of deaf students can be achieved.

- Since we have established a challenge relating to learning materials, subsequent studies could investigate the factors that lead to their inadequacy. For example, it would be important to establish whether institutions get enough funding from the government to purchase materials and other resources that are needed to educate deaf students. In addition, the maintenance of such materials, ensuring efficient and equitable use, as well as their administration, should be evaluated.

- Future researchers can investigate the issues facing other sections of the deaf population, such as immigrants, or across different age-groups. It has been established that there are wide disparities in learning and education outcomes between such groups and the rest of the population. Given that being deaf also comes with unique challenges, it would be important to understand how the intersectionality between social disadvantage and deafness affects deaf students. For instance, it would be prudent to explore the challenges that deaf students from poor backgrounds face during the pandemic.

Limitations

As with any other study, certain limitations are present in this study. We conducted this study using a systematic literature review process [ 98 , 99 ]. Our literature review highlights the major obstacles to deaf and hard-of-hearing distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the fact that our study is limited to impaired and hearing students, there are several limitations worth noting. We explain these limitations as follows.

Data completeness The first limitation of the systematic literature review is the scope and appropriate selection of digital libraries. Therefore, we selected nine diverse electronic data sources. The next step was to ensure that the relevant literature publications were identified and included. We reasoned, though, that there might be other sources relevant within our domain search. Regardless, we attempted to mitigate this limitation as follows. We seeded a domain search with a set of search queries. If sufficient domain expertise is available, the search queries can be created manually; otherwise, a snowballing technique can be used [ 49 , 100 ] in which a small number of initial search terms are used to retrieve a set of results, and then, commonly occurring domain-specific phrases are identified and used to seed further search queries. We also employed an iterative strategy for our term-list construction. Different research communities might likely refer to the same concept or term differently. Hence, the iterative strategy ensured that adequate terms were used in the search process.

Taxonomy bread-and-depth The second limitation is the validity of the constructed taxonomy. We reason whether the taxonomy has sufficient breadth and depth to ensure that accurate classification and systematic analysis are achieved within the deaf and hearing disability domain’s scope. To mitigate this limitation, we employed a well-known content analysis method. In this case, the taxonomy was continuously filtered and evolved to account for every essential component of the paper included. This iterative process boosted our confidence that the taxonomy incurred substantially good coverage for the methods and types of disabilities that were included and examined throughout this literature review.

Objectiveness The third limitation refers to the objectiveness of the study. Typically this reflects on possible biases or flaws in the results. To mitigate this limitation, we have examined each reviewer’s bias by cross-checking the papers. What that means is that no paper received only one reviewer. Thus, multiple reviewers were involved in the process. Furthermore, we have also obtained the summary of the conclusions according to a collection of categorized papers, rather than following only individual reviewers’ interpretations or views with one goal only to avoid bias.

Now that we have identified the barriers to distance learning faced by deaf and hard-of-hearing during the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe future researchers would benefit from this study.

Conclusion and further work

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive literature review with the aim to investigate the chief challenges that education has faced recently by deaf and hard-of-hearing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. In summary, our research contributions provide substantial evidence about the immediate need to investigate the barriers that we emphasized in the previous section. Furthermore, this early contribution of the present work opens an opportunity for the research community and the educational sector to address these needs broadly and globally with similar interest and care. Additionally, our work directly contributes to the literature by providing a detailed analysis of online learning challenges for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. Most critically, it brings forward attention to recommending educational systems to be more accessible during pandemic crises and leverage teaching strategies that can be easily incorporated even in the face of environmental crisis. In addition, we have also disseminated our data as a supplementary electronic file for the research community to engage more extensively in a similar line of research and replicate our work for further advancement of SLR research.

In future work, we will investigate these challenges by extending it further by leveraging an interview-based study with deaf and hard-of-hearing students, where we can understand each problem and propose possible improvements in regard to these problems for individuals and groups. Continuing further this line of research may have an impact on improving and refining existing distance learning pedagogical methodologies and enable participation of the deaf community word-widely beyond the current educational deficiencies within the realm of the accessibility domain.

Declarations

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wajdi Aljedaani, Email: ude.tnu.ym@inaadejlaidjaw .

Rrezarta Krasniqi, Email: ude.tnu.ym@iqinsarKatrazerR .

Sanaa Aljedaani, Email: [email protected] .

Mohamed Wiem Mkaouer, Email: ude.tir@esvmwm .

Stephanie Ludi, Email: [email protected] .

Khaled Al-Raddah, Email: ude.tir@5413alk .

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Challenges That Still Exist for the Deaf Community

What life is like for the deaf and hard of hearing (HOH) has changed significantly in the past half-century. Policy changes and new technologies have provided solutions for many, and yet some hurdles have stayed the same.

The Soukup family—three generations of deaf men—have watched these changes and roadblocks unfold. When a big storm destroyed Ben Soukup Sr.’s farm in 1960, he went to banks all over town to get a loan to rebuild. Every one of them denied his application for one simple reason: He was deaf.

His son never forgot the experience of watching his dad lose his farm and ended up dedicating his life to helping deaf individuals communicate with the world around them, a legacy carried on by his own son, Chris, nearly half a century later.

Ben Soukup Jr. founded the nonprofit Communication Service for the Deaf (CSD), one of a number of nonprofits in the U.S. dedicated to empowering deaf and HOH individuals. Chris has continued the work as the organization’s CEO.

Years after Ben Soukup Sr. lost his farm, the deaf and hard of hearing community would go on to experience some of the greatest advancements in the United States and globally. However, a great number of challenges persist.

Advancements

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) helped pave the way for easier communication between the hearing and deaf or HOH individuals. Passed in 1990, the law was a major turning point for the deaf community in the United States.

The ADA sought to level the playing field for those with disabilities by requiring public and private entities like schools and telecommunication services to provide accommodations for those who are deaf or have hearing loss. The impact was monumental.

Employers were no longer allowed to discriminate against those who were deaf or HOH. Relay services allowed some to make phone calls for the very first time, no longer needing to rely on hearing friends and neighbors call their cable company or make a doctor’s appointment.

Captions appeared below the anchors during the nightly news, and schools and hospitals began providing interpretation services for those who use American Sign Language. The communication chasm between the hearing and non-hearing worlds began to narrow.

The emergence of the internet and electronic devices continued to transform the way deaf and HOH individuals communicate. As email, online messengers, texting, and smartphones become increasingly popular and accessible, speaking and hearing are no longer required to do everyday tasks like ordering takeout or disputing a bill.

Video conferencing services, like Skype or Zoom, have made it significantly easier for sign language users to talk with each other or for remote interpreters to assist with conversations with hearing friends and colleagues

Social media has allowed deaf and HOH individuals to find and connect with one another more easily—helping those living in rural areas, in particular, to find community and build a support network.

Interpretation services are still needed for many situations, but those in the deaf and HOH community are able to interact with more people on their own than ever before. But while the playing field may indeed be leveling, persistent challenges remain.

Economic Challenges

With the passage of legislation like the ADA, those in the deaf community are no longer strictly relegated to the role of a factory worker or hard laborer, but unemployment and underemployment still disproportionately affect them.

Roughly 8% of U.S. working-age adults who are deaf or HOH were actively looking for work yet still unemployed in 2018, with more finding only part-time or temporary positions—and only about 39.5% were employed full time in 2018, compared to 57.5% of their hearing counterparts.

These same gaps persist in education as well. Despite mandates made by the ADA, typical schools and universities are rarely set up in a way that helps deaf and HOH students thrive, and only a few deaf and HOH educational institutions exist. An estimated 33% of working-age, hearing adults have a bachelor’s degree or higher, but only 18% of those who are deaf or HOH do.

The impact of these employment and educational challenges has a ripple effect. Those in the deaf and HOH community are already at higher risk for depression and anxiety. But evidence from psychologists and sociologists indicates that inadequate employment can also be linked to a host of mental health issues , as well as chronic conditions and substance abuse.

All of this can often complicate efforts to find or hold adequate employment, resulting in a vicious cycle—especially when families are unable to access or afford health care.

The largest chunk of insured Americans gets their coverage through their employers . Unemployed or only part-time employed deaf and HOH adults often depend on public assistance programs like Medicaid , which vary widely by state.

One in 10 U.S. deaf or HOH adults aged 21 to 64 years did not have health insurance in 2018, but that’s actually below the national average for people without a disability. The percentage of insured deaf and HOH adults ranged from under 2% in Massachusetts and Washington DC to 17% in Texas.

This is not to say that all underemployed deaf and HOH individuals will struggle with major health issues, but the economic and emotional hardships often associated with not being able to find sufficient work shouldn’t be dismissed.

Families with deaf or HOH working-age adults make, on average, about $15,000 less per year than families with no disabilites, and an estimated 20% of U.S. working-age adults who are deaf or HOH live in poverty, compared to just 10% of their hearing counterparts.

Poverty has its own way of impacting health. Studies show that low-income Americans with limited education are consistently less healthy than their higher educated, wealthier peers, especially for minority populations. Socioeconomic status and education levels are linked to a wide range of health outcomes—from low birth weight to diabetes.

Because of the interconnectedness of many of these issues, overcoming them will not be a simple legislative fix. While many deaf and HOH individuals receive financial support from initiatives like the Social Security Disability and Supplemental Security Income programs, more can be done to encourage equal access to employment and education.

“Where we are still challenged is by and large in the perception of deaf people and their potential,” said Soukup in an interview with Verywell—the potential for not just adequate employment, but also in gaining equal opportunities to advance in the workplace and educational programs.

For CSD’s part, it is launching a venture capital fund for deaf entrepreneurs, helping companies to identify and hire deaf and HOH workers, and assisting companies like Uber to create training materials in American Sign Language . But to overcome the largest economic hurdles, the United States must also tackle the social challenges faced by those who are deaf and HOH.

Social Challenges

Hearing challenges affect all ages, races, and ethnicities, from the entire spectrum of socioeconomic and geographic backgrounds. Some people were born deaf, some lost hearing as a result of a medical condition, illness, time, or trauma.

Some hear a little with the support of a cochlear implant or hearing aid. Some can’t hear anything at all. In fact, the abilities and needs of those with hearing disabilities are as diverse as the community itself.

American Sign Language (ASL)

We don’t know exactly how many people in the United States use ASL, but estimates range from 100,000 to 1 million. Interpreters—they are not called “translators”—help ASL users communicate with hearing individuals.

The ADA required public institutions and schools to provide ASL interpreters for those who need them. You have probably seen them at news conferences during natural disasters, for example, or even at concerts.

ASL is not simply a gesture-based translation of English. It’s a distinct language with its own complex grammar, pronunciation, and word order rules. Just like English, expressions and messages can vary based on who is doing the interpreting.

Often ASL users do not get to choose the interpreter provided or have the option to request interpreters they prefer over others—and that can impact a deaf or HOH individual’s ability to communicate or understand important information.

Even when a sign language interpreter is provided, sometimes it’s not enough. In certain situations—such as a doctor’s office, for example—a certified deaf interpreter might be needed to work alongside the ASL interpreter to ensure nuances are effectively communicated.

Similarly, while many deaf individuals are also fluent in written English, writing things down might not be the best way to communicate with them—especially if sign language is their primary language—and family members who speak ASL shouldn’t be used as a substitute for certified interpreters.

Social Isolation

Nine in 10 deaf children are born to hearing parents, yet less than a third have family members who sign regularly .

Some families rely on the deaf or HOH person to read lips, but this is remarkably difficult and frequently results in an inaccurate understanding of what’s been said. It also requires the deaf or HOH person to “listen” in a way that may not be as easy for them as watching someone sign.

You can imagine the emotional and psychological toll of not being able to communicate with those closest to you, let alone others at school or work. For many deaf individuals living in rural areas, they might be the only deaf person in their community or school, making it extremely challenging to build relationships.

"I remember feeling alone, even when around a lot of people, because of communication barriers,” said Soukup. “I knew that most people were not malicious and that communication barriers exist only because of limited exposure to deaf people and a lack of understanding."

In addition to social isolation, some research shows that deaf children, in particular, are more vulnerable to abuse, neglect, and sexual assault than their hearing peers—the results of which can have a lasting impact on both mental and physical health.

Public Health Challenges

In truth, very little research exists on the health needs of the deaf and HOH population. Health surveys, for example, are often conducted over the phone to the exclusion of deaf people, and most large-scale public health studies do not have ways to parse out data specifically regarding those with hearing loss or deafness.

Many deaf and HOH individuals are unaware of things that might be common knowledge to hearing individuals, such as their own family medical histories or even basic medical terminology because they don’t have the benefit of being able to overhear relatives discussing health matters or other peripheral conversations.

Interactions with medical professionals can be unsatisfying for both parties, as ASL users encounter barriers to qualified interpreters, and medical organizations face difficulties getting reimbursed for providing such services. The experience can be frustrating for all involved.

Suggestions for Improvement

In 2011, researchers published suggestions on ways to close the gap on some of the health inequities encountered by deaf and HOH populations. They suggest we should:

- Improve access to health information for deaf families . This includes adding captions to all public health information with audio, like informational videos, and ensuring that emergency preparedness plans are made with the input of deaf and HOH individuals.

- Include more deaf and HOH people in the research process . Recruitment for public health research projects should be tailored to the deaf and HOH populations, including providing and collecting information using ASL.

- Collect and analyze new and existing data with deaf and HOH people in mind . This could include the simple addition of deaf-related demographic information on surveys, such as at what age hearing loss occurred.

- Encourage ASL users to participate in public health discussions . Community-based participatory research should actively recruit deaf or HOH individuals to provide insight into all health issues—not just those related to hearing—and interpretation services should be provided at public health conferences and events.

- Encourage deaf and HOH people to work in public health and health-related fields . By embarking on careers in health, deaf and HOH can then help shape training curriculum and health experiences to be more accessible to their deaf and HOH peers.

- Advocate for more funding for communication services . Interpretation services are essential for deaf and HOH populations interacting with the health community, but they can be expensive. Talking with policymakers about the need for and importance of funding for these services could help allow for expanded access to medical services and health-related programs.

A Word From Verywell

Much has changed in the decades since Ben Soukup Sr. was denied a loan, but it will take a collective effort at the local, state, and national levels to continue to make true progress.

That being said, hearing individuals can support these efforts by doing more to seek out and build relationships with deaf and HOH people in their communities, and in doing so, help to close the social chasm between the hearing and deaf or HOH world.

Frequently Asked Questions

As of 2011, it was estimated that 30 million people in the U.S. age 12 and older experienced hearing loss in both ears.

People can be born deaf from genetic factors such as hereditary hearing loss and intrauterine infections. Two examples of intrauterine infections are rubella and cytomegalovirus .

People with deafness communicate through visual, auditory, and tactile modes.

- Visual: American sign language (ASL), cued speech (using hand shapes to differentiate speech sounds), lip reading, and gestures

- Auditory: Assisted hearing with a hearing aid or cochlear implant

- Tactile: Uses the hands and body to communicate

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Hearing loss organizations and associations .

Cornell University. Disability statistics .

Garberoglio CL, Cawthon S, Sales A. Deaf people and educational attainment in the United States: 2017 . National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes.

Kushalnagar P, Reesman J, Holcomb T, Ryan C. Prevalence of anxiety or depression diagnosis in deaf adults . J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ . 2019 Oct 1;24(4):378-385. doi:10.1093/deafed/enz017

Herbig B, Dragano N, Angerer P. Health in the long-term unemployed . Dtsch Arztebl Int . 2013;110(23-24):413-9. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2013.0413

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Health insurance coverage of the total population .

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us . American Journal of Public Health . 2010;100(S1). doi:10.2105/ajph.2009.166082

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Data2020 .