25 Basic Research Examples

Basic research is research that focuses on expanding human knowledge, without obvious practical applications.

For a scholarly definition, we can turn to Grimsgaard (2023):

“Basic research, also called pure, theoretical or fundamental research, tends to focus more on ‘big picture’ topics, such as increasing the scientific knowledge base around a particular topic.”

It is contrasted with applied research , which “seeks to solve real world problems” (Lehmann, 2023).

Generally, basis research has no clear economic or market value, meaning it tends to take place in universities rather than private organizations. Nevertheless, this blue-skies basic research can lead to enormous technological breakthroughs that forms the foundation for future applied research .

Basic Research Examples

- Physics: Understanding the properties of neutrinos.

- Medicine: Investigating the role of gut microbiota in mental health.

- Anthropology: Studying the social structures of ancient civilizations.

- Biology: Exploring the mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing.

- Psychology: Understanding the cognitive development in infants.

- Chemistry: Researching new catalytic processes for organic synthesis.

- Astronomy: Investigating the life cycle of stars.

- Sociology: Exploring the impacts of social media on society.

- Ecology: Studying the biodiversity in rainforests.

- Computer Science: Developing new algorithms for machine learning.

- Mathematics: Exploring new approaches to number theory.

- Economics: Investigating the causes and effects of inflation.

- Linguistics: Researching the evolution of languages over time.

- Political Science: Studying the effects of political campaigns on voter behavior.

- Geology: Investigating the formation of mountain ranges.

- Architecture: Studying ancient building techniques and materials.

- Education: Researching the impact of remote learning on academic performance.

- History: Investigating trade routes in the medieval period.

- Literature: Analyzing symbolism in 19th-century novels.

- Philosophy: Exploring concepts of justice in different cultures.

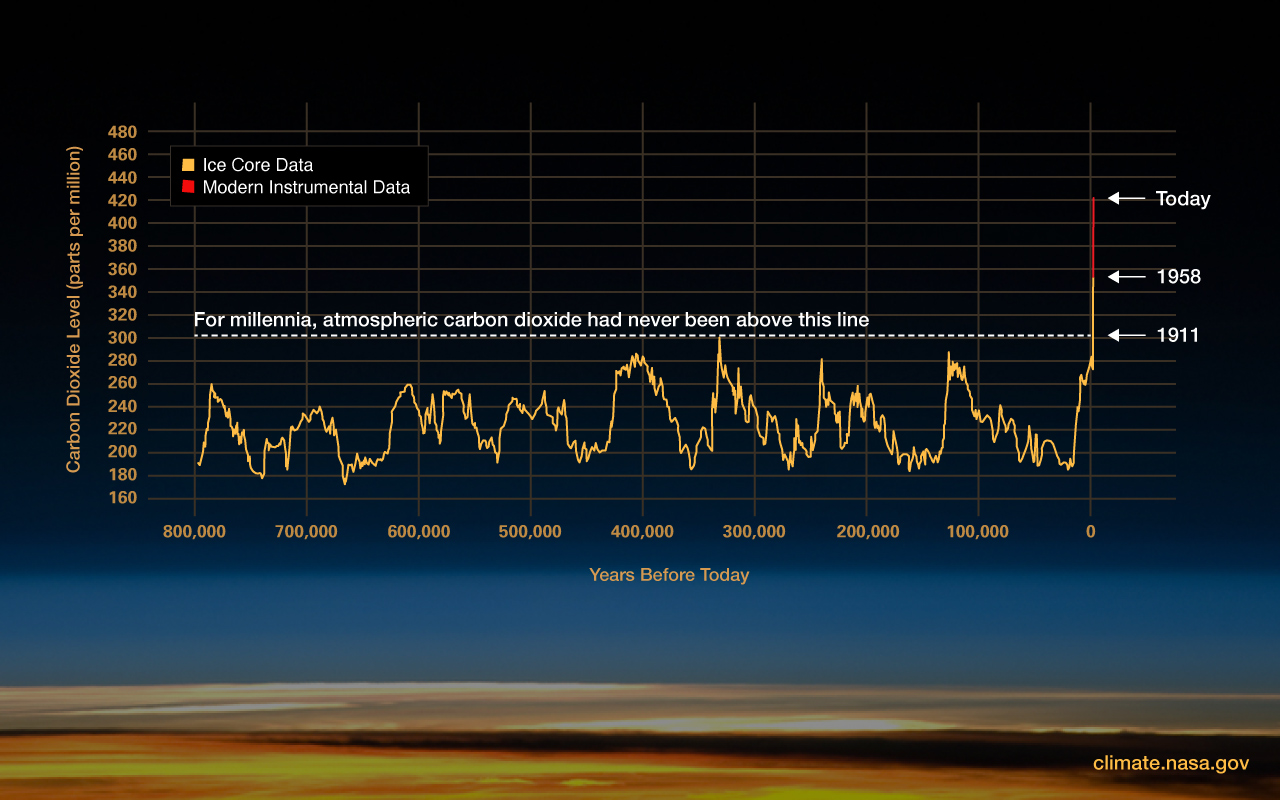

- Environmental Science: Studying the impact of plastics on marine life.

- Genetics: Investigating the role of specific genes in aging.

- Engineering: Researching materials for improving battery technology.

- Art History: Investigating the influence of politics on Renaissance art.

- Agricultural Science: Studying the impact of pest management practices on crop yield.

Case Studies

1. understanding the structure of the atom.

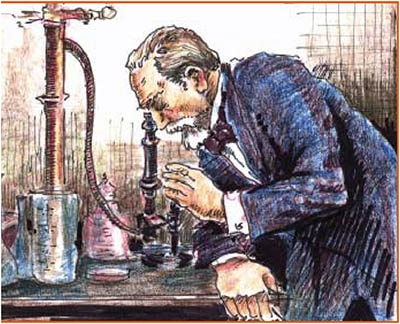

The study of atomic structure began in the early 1800s, with John Dalton’s atomic theory suggesting that atoms were indivisible and indestructible. However, it was not until the 20th century that Ernest Rutherford’s gold foil experiment led to the discovery of the nucleus and the proposal of the planetary model of the atom, which was further refined by Niels Bohr and eventually led to the quantum mechanical model, showing that electrons move in orbital shells around the nucleus.

Research Context:

- Topic: Investigating the structure and behavior of atoms.

- Purpose: Understand the fundamental particles (protons, neutrons, and electrons) and forces that govern atomic behavior.

- Methodology: Utilize particle accelerators, theoretical models, and experimental physics.

- Significance: Fundamental understanding of atomic structures has paved the way for numerous technological and scientific breakthroughs, such as the development of nuclear energy and advancements in chemistry and materials science.

Outcomes and Further Developments:

- Discovery and exploration of subatomic particles like quarks.

- Development of quantum mechanics and quantum field theory.

- Subsequent advancements in various scientific fields, such as nuclear physics, chemistry, and nanotechnology.

2. Researching the Human Genome

The Human Genome Project, an international research effort that began in 1990, aimed to sequence and map all of the genes – collectively known as the genome – of humans. Completed in 2003, it represented a monumental achievement in science, providing researchers with powerful tools to understand the genetic factors in human disease, paving the way for new strategies for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.

- Topic: Investigating the structure, function, and mapping of the human genome.

- Purpose: Understand the genetic makeup of humans, identify genes, and learn how they work.

- Methodology: Techniques like DNA sequencing, genetic mapping, and computational biology.

- Significance: Foundational for various advancements in genetics, medicine, and biology, providing insights into diseases, development, and evolution.

- Completion of the Human Genome Project, which mapped the entire human genome.

- Advancements in personalized medicine, genetic testing, and gene therapy.

- Development of CRISPR technology, enabling precise genetic editing.

Basic Research vs Applied Research

Basic research focuses on expanding knowledge and understanding fundamental concepts without immediate practical application, while applied research focuses on solving specific, practical problems using the knowledge gained from basic research (Akcigit, Hanley & Serrano-Velarde, 2021).

A simple comparison of definitions is below:

- Basic research seeks to gain greater knowledge or understanding of the fundamental aspects of phenomena.

- Applied research seeks to solve practical problems the researcher or their stakeholders are facing.

A researcher might choose basic research over applied if their primary motivation is to expand the boundaries of human knowledge and contribute to academic theories, whilst they might favor applied research if they are more interested in achieving immediate solutions, innovations, or enhancements impacting real-world scenarios (Akcigit, Hanley & Serrano-Velarde, 2021; Baetu, 2016).

To learn more about applied research, check out my article on applied research.

Basic Research: Disappearing in 21st Century Universities?

In the 1980s, universities increasingly came under pressure to prove their specific financial value to society. This has only intensified over the decades. So, whereas once universities were preoccupied with basic research, there’s been a big push toward academic-industry collaborations where research demonstrates its economic value, rather than its cultural or intellectual value, to society. This may, on the one hand, help make universities relevant to today’s world. But on the other hand, it may interfere with the blue skies research that could identify and solve the bigger, less financially pressing, questions and problems of our ages (Bentley, Gulbrandsen & Kyvik, 2015).

Pros and Cons of Basic Research

The primary advantage of basic research is that it generates knowledge and understanding of fundamental principles that can later serve as a foundation for technological advancement or social betterment.

It can lead to groundbreaking discoveries, stimulate creativity, and drive scientific innovation by satisfying human curiosity (Akcigit, Hanley & Serrano-Velarde, 2021; Baetu, 2016).

It is also often the catalyst for training the next generation of scientists and researchers.

However, basic research can be time-consuming, expensive, and its outcomes may not always be directly observable or immediately beneficial.

This is why it’s often left to government-funded research institutes and universities to conduct this sort of research. As Binswanger (2014) argues, “basic research constitutes, for the most part, a common good which cannot be sold profitably on markets.

Furthermore, its value is often underestimated because the applications are not immediately apparent or tangible.

Below is a summary of some advantages and disadvantages of basic research:

Abeysekera, A. (2019). Basic research and applied research. Journal of the National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka , 47 (3).

Akcigit, U., Hanley, D., & Serrano-Velarde, N. (2021). Back to basics: Basic research spillovers, innovation policy, and growth. The Review of Economic Studies , 88 (1), 1-43.

Baetu, T. M. (2016). The ‘big picture’: the problem of extrapolation in basic research. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science.

Bentley, P. J., Gulbrandsen, M., & Kyvik, S. (2015). The relationship between basic and applied research in universities. Higher Education , 70 , 689-709. ( Source )

Binswanger, M. (2014). How nonsense became excellence: forcing professors to publish. In Welpe, I. M., Wollersheim, J., Osterloh, M., & Ringelhan, S. (Eds.), Incentives and Performance: Governance of Research Organizations . Springer International Publishing.

Grimsgaard, W. (2023). Design and strategy: a step by step guide . New York: Taylor & Francis.

Lehmann, W. (2023). Social Media Theory and Communications Practice . London: Taylor & Francis.

Wiid, J., & Diggines, C. (2009). Marketing Research . Juta.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Basic Research: What it is with examples

In building knowledge, there are many stages and methodologies to generate insights that contribute to its understanding and advancement; basic research and applied research are usually the most effective on this path.

Understanding research allows us to understand all the properties of a specific science or phenomenon at a fundamental level. Some examples are branches such as sociology, humanities, and other scientific fields; below, we will tell you everything you need to know about this type of research and its possible applications.

What is Basic Research?

Basic Research is a type of research used in the scientific field to understand and extend our knowledge about a specific phenomenon or field. It is also accepted as pure investigation or fundamental research .

This type of research contributes to the intellectual body of knowledge. Basic research is concerned with the generalization of a theory in a branch of knowledge; its purpose is usually to generate data that confirm or refute the initial thesis of the study.

It can also be called foundational research; many things get built on this foundation, and more practical applications are made.

Basic Research vs. Applied Research

Basic Research finds its counterpart and complement in applied research. They are two handy research methods when generating and giving a utility to the generated data. There are very marked differences, and understanding them will allow you to understand the path followed to create new knowledge.

The most important difference between basic research and applied research lies in the objective of each. It seeks to expand the information and understanding of the object of study, while applied research aims to provide a solution to the problem studied.

The relationship between these two types of research is usually very close since the methodologies used are often quite similar; the significant change is found in the initial and final point of the investigation.

Basic Research Examples

There can be many examples of basic research; here are some of them:

- A study of how stress affects labor productivity.

- Studying the best factors of pricing strategies.

- Understand the client’s level of satisfaction before certain interactions with the company providing solutions.

- The understanding of the leadership style of a particular company.

Advantages & Disadvantages

Basic research is critical for expanding the pool of knowledge in any discipline. The introductory course usually does not have a strict period, and the researcher’s concern commonly guides them. The conclusion of the fundamental course is generally applicable in a wide range of cases and plots.

At the same time, the basic study has disadvantages as well. The findings of this type of study have limited or no constructive conclusions. In another sense, fundamental studies do not resolve complex and definite business problems, but it does help you understand them better.

Taking actions and decisions based on the results of this type of research will increase the impact these insights may have on the problem studied if that is the purpose.

LEARN ABOUT: Theoretical Research

How to do basic research?

This process follows the same steps as a standard research methodology. The most crucial point is to define a thesis or theory that involves a perfectly defined case study; this can be a phenomenon or a research problem observed in a particular place.

There are many types of research, such as longitudinal studies , observational research , and exploratory studies. So the first thing you should do is determine if you can obtain the desired result with research or if it is better to opt for another type of research.

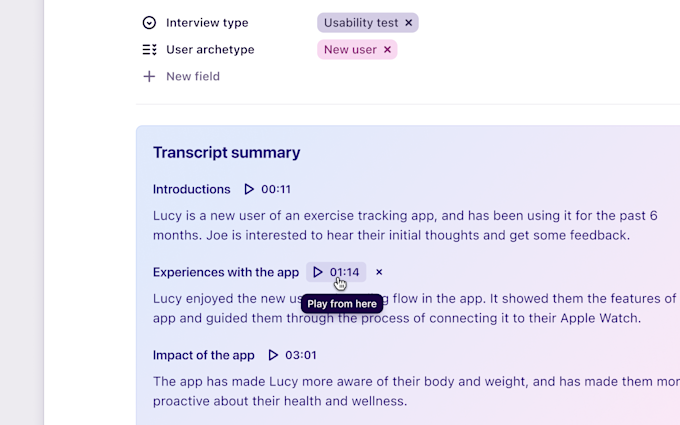

Once you have determined your research methodology, the data collection process begins, also depending on your type of study; sometimes, you can collect the data passively through observation or experimentation. On other occasions, intervene directly and collect quantitative information with tools such as surveys.

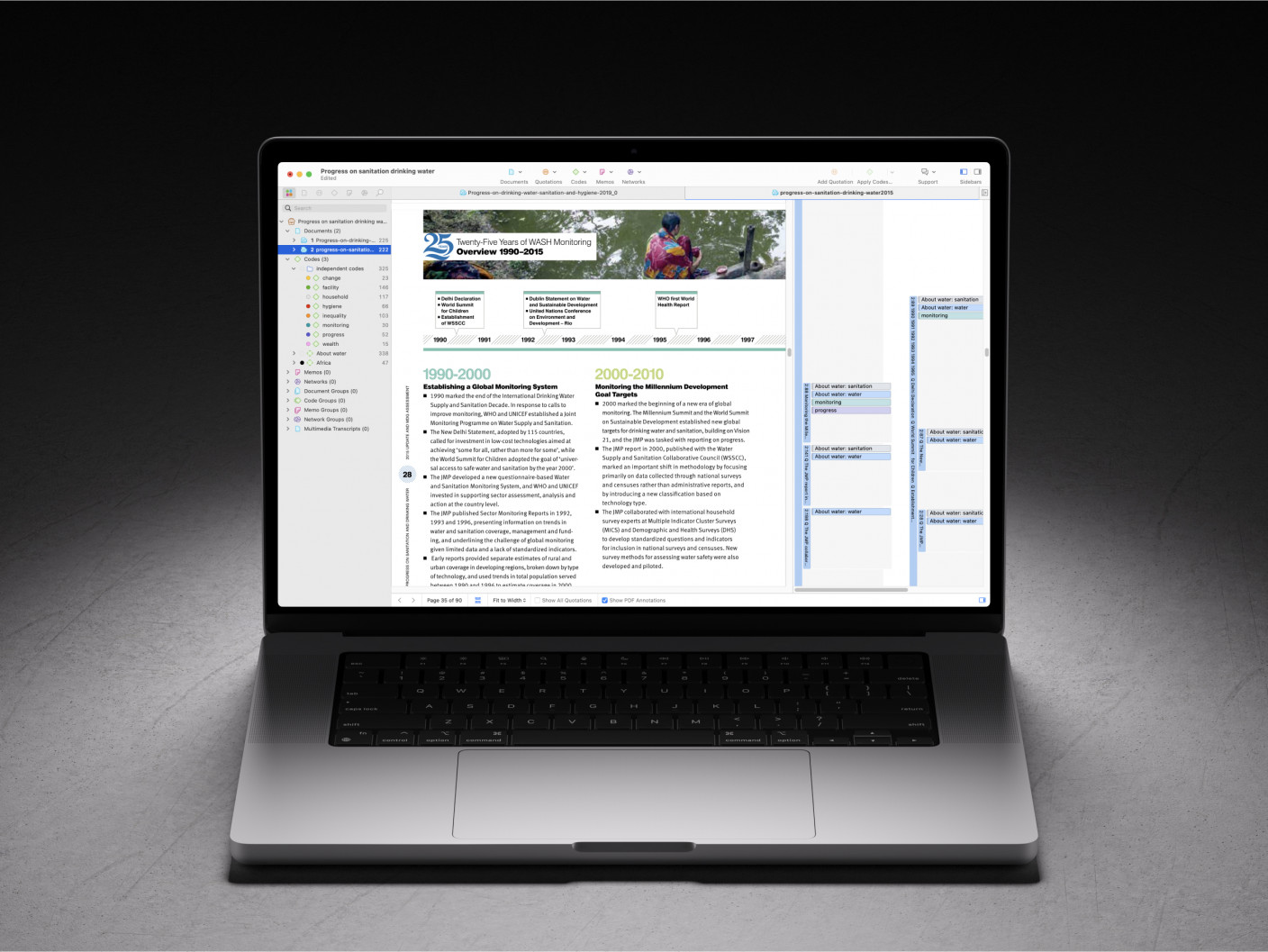

Platforms like QuestionPro will help you have a wide range of functions and tools to carry out your research; its survey software has helped students and professionals obtain all the information necessary to generate high-value insights.

In addition, it has a data analysis suite with which you can analyze all this information using all kinds of reports for a more straightforward interpretation of the final results.

QuestionPro is much more than survey software ; we have a solution for each specific problem and industry. We also offer data management platforms such as our research data repository called Insights Hub.

MORE LIKE THIS

Unlocking Creativity With 10 Top Idea Management Software

Mar 23, 2024

20 Best Website Optimization Tools to Improve Your Website

Mar 22, 2024

15 Best Digital Customer Experience Software of 2024

15 Best Product Experience Software of 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Basic Research in Psychology

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Basic research—also known as fundamental or pure research—refers to study and research meant to increase our scientific knowledge base. This type of research is often purely theoretical, with the intent of increasing our understanding of certain phenomena or behavior. In contrast with applied research, basic research doesn't seek to solve or treat these problems.

Basic Research Examples

Basic research in psychology might explore:

- Whether stress levels influence how often students engage in academic cheating

- How caffeine consumption affects the brain

- Whether men or women are more likely to be diagnosed with depression

- How attachment styles among children of divorced parents compare to those raised by married parents

In all of these examples, the goal is merely to increase knowledge on a topic, not to come up with a practical solution to a problem.

The Link Between Basic and Applied Research

As Stanovich (2007) noted, many practical solutions to real-world problems have emerged directly from basic research. For this reason, the distinction between basic research and applied research is often simply a matter of time. As social psychologist Kurt Lewin once observed, "There is nothing so practical as a good theory."

For example, researchers might conduct basic research on how stress levels impact students academically, emotionally, and socially. The results of these theoretical explorations might lead to further studies designed to solve specific problems. Researchers might initially observe that students with high stress levels are more prone to dropping out of college before graduating. These first studies are examples of basic research designed to learn more about the topic.

As a result, scientists might then design research to determine what interventions might best lower these stress levels. Such studies would be examples of applied research. The purpose of applied research is specifically focused on solving a real problem that exists in the world. Thanks to the foundations established by basic research, psychologists can then design interventions that will help students effectively manage their stress levels , with the hopes of improving college retention rates.

Why Basic Research Is Important

The possible applications of basic research might not be obvious right away. During the earliest phases of basic research, scientists might not even be able to see how the information gleaned from theoretical research might ever apply to real-world problems. However, this foundational knowledge is essential. By learning as much as possible about a topic, researchers are able to gather what they need to know about an issue to fully understand the impact it may have.

"For example, early neuroscientists conducted basic research studies to understand how neurons function. The applications of this knowledge were not clear until much later when neuroscientists better understood how this neural functioning affected behavior," explained author Dawn M. McBride in her text The Process of Research in Psychology . "The understanding of the basic knowledge of neural functioning became useful in helping individuals with disorders long after this research had been completed."

Basic Research Methods

Basic research relies on many types of investigatory tools. These include observation, case studies, experiments, focus groups, surveys, interviews—anything that increases the scope of knowledge on the topic at hand.

Frequently Asked Questions

Psychologists interested in social behavior often undertake basic research. Social/community psychologists engaging in basic research are not trying to solve particular problems; rather, they want to learn more about why humans act the way they do.

Basic research is an effort to expand the scope of knowledge on a topic. Applied research uses such knowledge to solve specific problems.

An effective basic research problem statement outlines the importance of the topic; the study's significance and methods; what the research is investigating; how the results will be reported; and what the research will probably require.

Basic research might investigate, for example, the relationship between academic stress levels and cheating; how caffeine affects the brain; depression incidence in men vs. women; or attachment styles among children of divorced and married parents.

By learning as much as possible about a topic, researchers can come to fully understand the impact it may have. This knowledge can then become the basis of applied research to solve a particular problem within the topic area.

Stanovich KE. How to Think Straight About Psychology . 8th edition. Boston, MA: Pearson Allyn and Bacon; 2007.

McCain KW. “Nothing as practical as a good theory” Does Lewin's Maxim still have salience in the applied social sciences? Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology . 2015;52(1):1-4. doi:10.1002/pra2.2015.145052010077

McBride DM. The Process of Research in Psychology . 3rd edition . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2015.

Committee on Department of Defense Basic Research. APPENDIX D: Definitions of basic, applied, and fundamental research . In: Assessment of Department of Defense Basic Research. Washington, D.C.: The National Academic Press; 2005.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- What is Pure or Basic Research? + [Examples & Method]

Sometimes, research may be aimed at expanding a field of knowledge or improving the understanding of a natural phenomenon. This type of research is known as a basic, pure or fundamental research, and it is a major means of generating new ideas, principles and theories.

In many cases, basic research fuels scientific innovations and development because it is driven by the need to unravel the unknown. In this article, we will define what basic research is, its data collection methods and how it differs from other approaches to research.

What is Basic Research?

Basic research is a type of research approach that is aimed at gaining a better understanding of a subject, phenomenon or basic law of nature. This type of research is primarily focused on the advancement of knowledge rather than solving a specific problem.

Basic research is also referred to as pure research or fundamental research. The concept of basic research emerged between the late 19th century and early 20th century in an attempt to bridge the gaps existing in the societal utility of science.

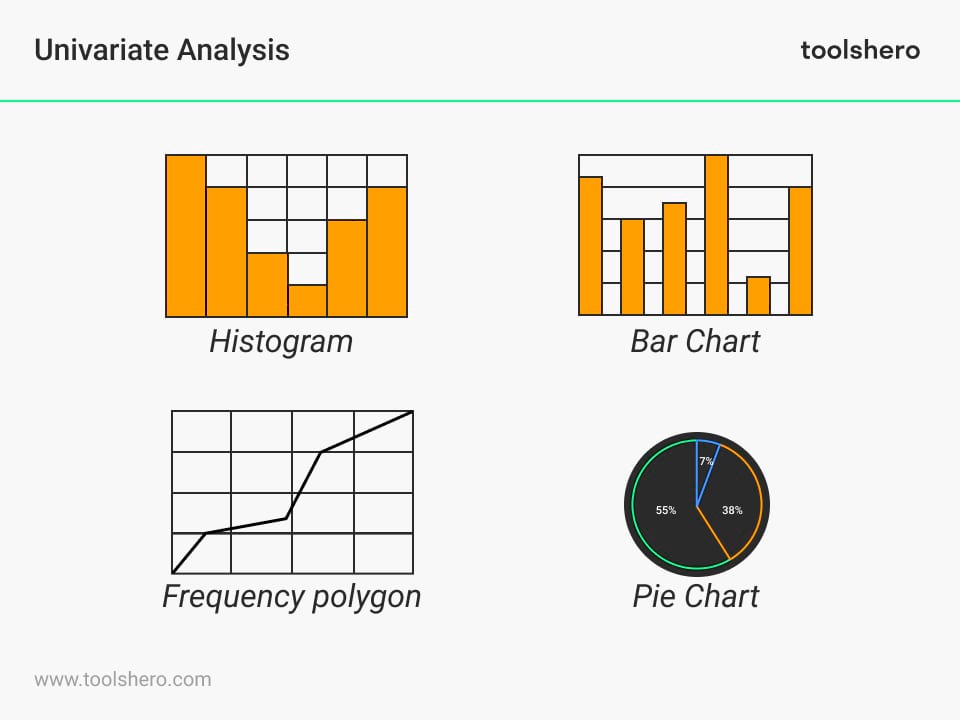

Typically, basic research can be exploratory , descriptive or explanatory; although in many cases, it is explanatory in nature. The primary aim of this research approach is to gather information in order to improve one’s understanding, and this information can then be useful in proffering solutions to a problem.

Examples of Basic Research

Basic research can be carried out in different fields with the primary aim of expanding the frontier of knowledge and developing the scope of these fields of study. Examples of basic research can be seen in medicine, education, psychology, technology, to mention but a few.

Basic Research Example in Education

In education, basic research is used to develop pedagogical theories that explain teaching and learning behaviours in the classroom. Examples of basic research in education include the following:

- How does the Language Acquisition Device work on children?

- How does the human retentive memory work?

- How do teaching methods affect student’s concentration in class?

Basic Research Example in Science

Basic research advances scientific knowledge by helping researchers understand the function of newly discovered molecules and cells, strange phenomena, or little-understood processes. As with other fields, basic research is responsible for many scientific breakthroughs; even though the knowledge gained may not seem to yield immediate benefits.

Examples of basic research in science include:

- A research to determine the chemical composition of organic molecules.

- A research to discover the components of the human DNA.

Basic Research Example in Psychology

In psychology, basic research helps individuals and organisations to gain insights and better understanding into different conditions. It is entirely theoretical and allows psychologists to understand certain behaviors better without providing solutions to these behaviours or phenomena.

Examples of basic research in psychology include:

- Do stress levels make individuals more aggressive?

- To what extent does caffeine consumption affect classroom concentration?

- A research on behavioral differences between children raised by separated families and children raised by married parents.

- To what extent do gender stereotypes trigger depression?

Basic Research Example in Health

Basic research methods improve healthcare by providing different dimensions to the understanding and interpretation of healthcare issues. For example, it allows healthcare practitioners to gain more insight into the origin of diseases which can help to provide cures to chronic medical conditions.

Many health researchers opine that many vaccines are developed based on an understanding of the causes of the disease such as in the case of the polio vaccine. Several medical breakthroughs have been attributed to the wealth of knowledge provided through basic research.

Examples of basic research in health include:

- An investigation into the symptoms of Coronavirus.

- An investigation into the causative factors of malaria

- An investigation into the secondary symptoms of high blood pressure.

Basic Research Method

An interview is a common method of data collection in basic research that involves having a one-on-one interaction with an individual in order to gather relevant information about a phenomenon. Interview can be structured, unstructured or semi-structured depending on the research process and objectives.

In a structured interview , the researcher asks a set of premeditated questions while in an unstructured interview, the researcher does not make use of a set of premeditated questions. Rather he or she depends on spontaneity and follow-up questioning in order to gather relevant information.

On the other hand, a semi-structured interview is a type of interview that allows the researcher to deviate from premeditated questions in order to gather more information about the research subject. You can conduct structured interviews online by creating and administering a survey online on Formplus .

- Observation

Observation is a type of data-gathering method that involves paying close attention to a phenomenon for a specific period of time in order to gather relevant information about its behaviors. When carrying out basic research, the researcher may need to study the research subject for a stipulated period as it interacts with its natural environment.

Observation can be structured or unstructured depending on its procedures and approach. In structured observation, the data collection is carried out using a predefined procedure and in line with a specific schedule while unstructured observation is not restricted to a predetermined procedure.

An experiment is a type of quantitative data-gathering method that seeks to validate or refute a hypothesis and it can also be used to test existing theories. In this method of data collection , the researcher manipulates dependent and independent variables to achieve objective research outcomes.

Typically, in an experiment, the independent variable is modified or changed in order to determine its effects on the dependent variables in the research context. This can be done using 3 major methods; controlled experiments , field experiments, and natural experiments

- Questionnaire

A questionnaire is a data collection tool that is made up of a series of questions to which the research subjects provide answers. It is a cost-effective method of data gathering because it allows you to collect large samples of data from the members of the group simultaneously.

You can create and administer your pure research questionnaire online using Formplus and you can also make use of paper questionnaires; although these are easily susceptible to damage. [

Here is a step-by-step guide of how to create and administer questionnaires for basic research using Formplus:

- Sign in to Formplus

In the Formplus builder, you can easily create different questionnaires for applied research by dragging and dropping preferred fields into your form. To access the Formplus builder, you will need to create an account on Formplus.

Once you do this, sign in to your account and click on “Create Form ” to begin.

Edit Form Title

Click on the field provided to input your form title, for example, “Basic Research Questionnaire”.

Click on the edit button to edit the form.

i. Add Fields: Drag and drop preferred form fields into your form from the Formplus builder Inputs column. There are several field input options for questionnaires in the Formplus builder.

ii. Edit fields

iii. Click on “Save”

iv. Preview form.

Form Customization

With the form customization options in the form builder, you can easily change the look and feel of your form and make it more unique and personalized. Formplus allows you to change your form theme, add background images and even change the font according to your brand specifications.

Multiple Sharing Options

Formplus offers multiple form sharing options which enables you to easily share your questionnaire with respondents. You can use the direct social media sharing buttons to share your form link to your social media pages.

In addition, Formplus has an option to convert form links to QR codes; you can personalize and display your form QR code on your website/banners for easy access. You also can send out survey forms as email invitations to your research subjects.

- Data Reporting

Data reporting is a type of data collection method where the researcher gathers relevant data and turns them in for further analysis in order to arrive at specific conclusions. The crux of this method depends, almost entirely, on the validity of the data collected.

- Case Studies

A case study is a type of data collection method that involves the detailed examination of a specific subject matter in order to gather objective information about the features and behaviors of the research subject. This method of data gathering is primarily qualitative , although it can also be quantitative or numerical in nature.

Case studies involve a detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions and their relationships. In carrying out a case study, the researcher must take extra care to identify the research questions, collect relevant data then evaluate and analyze the data in order to arrive at objective conclusions.

Read More: Research Questions: Definition, Types +[Examples]

How is Basic Research Different from Applied Research?

Applied research is a type of research that is concerned with solving practical problems using scientific methods while basic research is a type of research that is concerned with the expansion of knowledge.

Basic research generates new theories or improves on existing theories hence, it is theoretical in nature. On the other hand, applied research creates practical solutions to specific problems hence, it is practical in nature.

Basic research is knowledge-specific while applied research is solution-specific.

- Research Purpose

The purpose of basic research is to improve on existing knowledge or to discover new knowledge while the purpose of applied research is to solve specific problems.

The scope of basic research is universal while applied research is limited in nature. This means that while applied research addresses a specific problem and is limited to the problem which it addresses, basic research explores multiple dimensions of various fields.

- Basic research is primarily explanatory while applied research is descriptive in nature .

- Basic research adopts an indirect approach to problem-solving while applied research adopts a direct approach to problem-solving.

- In basic research, generalizations are common while in applied research, specific problems are investigated without the aim of generalizations.

Read Also: What is Applied Research? +[Types, Examples & Methods]

Characteristics of Basic Research

- Basic research is analytical in nature.

- It aims at theorizing concepts and not solving specific problems.

- It is primarily concerned with the expansion of knowledge and not with the applicability of the research outcomes.

- Basic research is explanatory in nature.

- Basic research is carried out without any primary focus on possible practical ends.

- It improves the general knowledge and understanding of different fields of study.

Importance of Basic Research

- Acquisition of New Knowledge: Basic research results in new knowledge. It is responsible for many research breakthroughs in different fields of study and it is often considered as the pacesetter in technological and innovative solutions.

- Basic research also enhances the understanding of different subject matters and provides multiple possible dimensions for interpretation of these subject matters.

- Findings of fundamental research are extremely useful in expanding the pool of knowledge in different disciplines.

- Basic research offers the foundation for applied research.

Disadvantages of Basic Research

- Findings from pure research have little or no immediate practical implications. However, these findings may be useful in providing solutions to different problems, in the long run.

- Fundamental research does not have strict deadlines.

- Basic research does not solve any specific problems.

Basic research is an important research method because it exposes researchers to varying dimensions within a field of study. This proves useful, not only for improving scholarship and the general knowledge-base, but for solving problems as is the concern of applied research.

When carrying out basic research, the investigator adopts one or more qualitative and quantitative observation methods which includes case studies, experiments and observation. These data collection methods help the researcher to gather the most valid and relevant information for the research.

In the case of using a survey or questionnaire for data collection , this can easily be done with the use of Formplus forms. Formplus allows you to create and administer different kinds of questionnaires, online and you can easily monitor and categ orise your form responses too.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- applied basic research differences

- basic research example

- basic-research-characteristics

- basic-research-method

- pure research

- pure research example

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Selection Bias in Research: Types, Examples & Impact

In this article, we’ll discuss the effects of selection bias, how it works, its common effects and the best ways to minimize it.

21 Chrome Extensions for Academic Researchers in 2022

In this article, we will discuss a number of chrome extensions you can use to make your research process even seamless

What is Applied Research? + [Types, Examples & Method]

Simple guide on applied research; its types, examples, characteristics, methods, and advantages

Basic vs Applied Research: 15 Key Differences

Differences between basic and applied research in definition, advantages, methods, types and examples

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Research Council (US) Committee to Update Science, Medicine, and Animals. Science, Medicine, and Animals. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004.

Science, Medicine, and Animals.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

The Concept of Basic Research

A nimal research is also important in another type of research, called basic research. Basic research experiments are performed to further scientific knowledge without an obvious or immediate benefit. The goal of basic research is to understand the function of newly discovered molecules and cells, strange phenomena, or little-understood processes. In spite of the fact that there may be no obvious value when the experiments are performed, many times this new knowledge leads to breakthrough methods and treatments years or decades later. For example, chemists developed a tool called a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) machine to determine the structure of chemicals. When it was developed, it had no obvious applications in medicine; however, scientists eventually realized that the NMR machine could be hooked up to a computer to make a magnetic resonance imagery (MRI) machine. The MRI machine takes pictures of the bone and internal tissues of the body without the use of radioactivity. Other examples of basic research that have led to important advances in medicine are the discovery of DNA (leading to cancer treatments) and neurotransmitters (leading to antidepressants and antiseizure medications). However, there are many other instances where basic research, some of which has been done on animals, has not yet resulted in any practical benefit to humans or animals.

NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance)—a machine that measures the vibration of atoms exposed to magnetic fields. Scientists use this machine to study the physical, chemical, and biological properties of matter.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging)—a machine that produces pictures of the bone and internal tissues of the body.

- Cite this Page National Research Council (US) Committee to Update Science, Medicine, and Animals. Science, Medicine, and Animals. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004. The Concept of Basic Research.

- PDF version of this title (3.9M)

Other titles in this collection

- The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health

Recent Activity

- The Concept of Basic Research - Science, Medicine, and Animals The Concept of Basic Research - Science, Medicine, and Animals

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Basic Research: Definition, Examples

Basic research focuses on the search for truth or the development of theory. Because of this property, basic research is fundamental. Researchers with their fundamental background knowledge “design studies that can test, refine, modify, or develop theories.”

Meaning and Definition of Basic Research

Generally, these researchers are affiliated with an academic institution and perform this research as part of their graduate or doctoral studies. Gathering knowledge for knowledge’s sake is the sole purpose of basic research .

Basic research is also called pure research. Basic research is driven by a scientist’s curiosity or interest in a scientific question.

The main motivation in basic research is to expand man’s knowledge, not to create or invent something. There is no obvious commercial value to the discoveries that result from basic research.

The term ‘basic’ indicates that, through theory generation, basic research provides the foundation for applied research . This research approach is essential for nourishing the expansion of knowledge.

It deals with questions that are intellectually interesting and challenging to the investigator. It focuses on refuting or supporting theories that operate in a changing society.

Basic research generates new ideas, principles, and theories, which may not be of immediate practical utility, though such research lays the foundations of modern progress and development in many fields.

Basic research rarely helps practitioners directly with everyday concerns but can stimulate new ways of thinking about our daily lives.

Basic researchers are more detached and academic in their approach and tend to have motives.

For example, an anthropologist may research to try and understand the physical properties, symbolic meanings, and practical qualities of things.

Such research contributes to understanding broad issues of interest to many social sciences-issues of self, family, and material culture .

Having said so, we come up with the following definition of basic research:

When the solution to the research problem has no apparent applications to any existing practical problem but serves only the scholarly interests of a community of a researcher, the research is basic.

Most scientists believe that a fundamental understanding of all branches of science is needed for progress to take place.

In other words, basic research lays the foundation for the following applied research . If basic work is done first, then this research often results from applied spin-offs.

A person wishing to do basic research in any specialized area must have studied the concepts and assumptions of that specialization enough to know what has been done in the past and what remains to be done.

For example, basic research is necessary for the health sector to generate new knowledge and technology to deal with major unsolved health problems.

Here are a few examples of questions asked in pure research:

- How did the universe begin?

- What are protons, neutrons, and electrons composed of?

- How do slime molds reproduce?

- How do the Neo-Malthusians view the Malthusian theory?

- What is the specific genetic code of the fruit fly?

- What is the relevance of the dividend theories in the capital market?

As there is no guarantee of short-term practical gain, researchers find it difficult to obtain funding for basic research.

Examples of Basic Research

The author investigated the smoothness of the solution of the degenerate Hamilton-Bellman (HJB) equation associated with a linear-quadratic regulator control.

The author established the existence of a classical solution of the degenerate HJB equation associated with this problem by the technique of viscosity solutions and hence derived an optimal control from the optimality conditions in the HJB equation.

Hasan (2009) gave a solution to linear programming problems through computer algebra. He developed a computer technique for solving such linear fractional programming problems in his paper.

At the outset, he determined all basic feasible solutions to the constraints, which are a system of linear equations.

The author then computed and compared the objective function values and obtained the optimal objective function value and optimal solutions. The method was then illustrated with a few numerical examples.

What is the primary focus of basic research?

Basic research primarily focuses on the search for truth or the development of theory. It is fundamental in nature and aims to design studies that test, refine, modify, or develop theories.

How does basic research differ from applied research in terms of its purpose?

The sole purpose of basic research is to gather knowledge for knowledge’s sake. It is driven by a scientist’s curiosity or interest in a scientific question without any immediate commercial value to the discoveries, whereas applied research has practical applications.

What is the significance of the term “basic” in basic research?

The term “basic” indicates that the research provides the foundation for applied research through theory generation. It lays the groundwork for modern progress and development in various fields.

Why might researchers face challenges in obtaining funding for basic research?

Since there is no guarantee of short-term practical gain from basic research, researchers often find it difficult to secure funding for such endeavors.

With a clear understanding of basic research; for more learning use our complete guideline on research and research methodology concepts .

- Exploratory Research: Definition, Types, Examples

- Monitoring and Evaluation: Process, Design, Methods

- Non-Probability Sampling

- Personal Interview Method: Definition, Advantages, Disadvantages, Techniques

- Theory: Meaning, Concepts, Theoretical Framework

- Questionnaire: Definition, Characteristics, Contents, Types

- Parallel Forms Method: Definition, Example

- Telephone Interviewing: Advantages, Disadvantages,

- Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA)

- Descriptive Research: Definition, 7 Types, Examples

- Research Paradigm: Key Concepts & Perspectives

- Types of Analytical Procedures

- Systematic Sampling: Definition, Examples

- Social Research: Definition, Examples

- Guttman Scale (Cumulative Scale): Definition, Example

What is Basic Research?

Introduction

What is the meaning of basic research, examples of basic research, how do i perform basic research.

Basic science research is an essential pillar of scientific knowledge, because it extends understanding, provides new insights, and contributes to the advancement of science and fundamental knowledge across disciplines. In contrast, applied research aims for the discovery of practical solutions, which can involve using a technology or innovation that stems from existing knowledge. Basic science research potentially allows for generating ideas on which applied science can build novel inquiry and useful applications.

The process for conducting basic research is essentially the same as in an applied research orientation, but a better understanding of the distinction may prove increasingly important when crafting your research inquiry. In this article, we'll detail the characteristics and importance of basic research.

One of the key distinctions in science is the divide between basic and applied research . Applied research is directly associated with practical applications such as:

- career development

- program evaluation

- policy reform

- community action

In inquiries regarding each of these applications, researchers identify a specific problem to be solved and design a study intentionally aimed at developing solutions to that problem. Basic research is less concerned about specific problems and more focused on the nature of understanding.

Characteristics of basic research

Research that advances understanding of knowledge has distinguishing characteristics and important considerations.

- Focus on theoretical development . Rather than focus on practical applications, scholars in basic science research are more interested in ordering data and understanding in a scientific manner. This means expanding the consensus understanding of theory and the proposal of new theoretical frameworks that ultimately further research.

- Exploratory research questions . Basic research tends to look at areas where there is insufficient theoretical coherence to empirically understand phenomena. In other words, basic research often employs research questions that seek greater definition of knowledge.

- Funding for basic science . The nature of the support available for research depends on whether the science is basic or applied . Government agencies, national institutes, and private organizations all have different objectives, making some more appropriate for basic research than others.

- Writing for research dissemination . Academic journals exist on a continuum between theoretical and practical orientations. Journals that are more interested in theoretical and methodological discussions are more appropriate for basic research than are journals that look for more practical implications arising from research.

The brief survey of these characteristics should guide researchers about how they should approach research design in terms of feasibility, methods, and execution. This discussion shouldn't preclude you from pursuing basic research if it is more appropriate to your research inquiry. Instead, it should inform you of the opportunities, advantages, and challenges of basic research.

Importance of basic research

Fundamental research may seem aimless and unfocused if it doesn't yield any direct practical implications. However, its contribution to scholarly discussion cannot be overstated as it guides the development of theories and facilitates critical discussion about what applied studies to pursue next.

Basic science has guided fields such as microbiology, engineering, and chemistry. Scientists ultimately use its findings to develop new methods in treating disease and innovating on new technology.

Its contribution to the social sciences through observation and longitudinal study is also immeasurable. While basic research is often a precursor to more applied science, the theories it generates spur further study that ultimately leads to professional development programs and policy reform in social institutions.

Shape your data, shape your research with ATLAS.ti

Dive into a transformative analysis experience with a free trial of our powerful data analysis software.

Different fields rely on both applied and basic science for generating new knowledge. While applied research looks to yield direct benefits through real-world applications, fundamental research provides the necessary theoretical foundation for practical research in various fields.

Basic research example in education

Basic research in schooling contexts focuses on understanding the nature of teaching and learning or the processes within educational environments before any focused investigation can be designed, let alone conducted. Basic research is necessary in this case because of the various situated differences across learners who come from different cultures and backgrounds.

Basic research in education looks at various inquiries such as how teachers and students interact with each other and how alternative assessments can create positive learning outcomes. Ultimately, this may lead to applied research that can facilitate the creation of teacher education and professional development programs.

Basic research example in psychology

Psychology is a field that is under constant development. Basic research is essential to developing theories related to human behavior and mental processes. The subfield of cognition is a significant benefactor of basic research as it relies on novel theoretical frameworks relating to memory and learning.

Basic research example in health

A great deal of health research that reaches public consciousness is undoubtedly applied research. The development of vaccines and other medicine to combat the COVID-19 pandemic was one such line of inquiry that addressed a practical need.

That said, scientists will undoubtedly credit basic research as a precursor to medical breakthroughs in applied science research. The knowledge gained through basic research laid the foundation for genomic sequencing of the COVID-19 virus, while experiments on living systems created knowledge about how to safely vaccinate the human body.

The National Institute of Health sponsors such basic research and research in other areas such as human DNA, while the National Science Foundation funds basic research on topics such as gender stereotypes and stress levels.

At its core, all scientific inquiry seeks to identify causal factors, relationships, and distinguishing characteristics among concepts and phenomena. As a result, the process is essentially the same for basic or applied science. Nonetheless, it is worth reviewing the process.

- Research design . Identify gaps in existing research that novel inquiry can address. A rigorous literature review can help identify theoretical or methodological gaps that a new study with an exploratory research question can address.

- Data collection . Exploratory research questions tend to prioritize data collection methods such as interviews , focus groups , and observations . Basic research, as a result, casts a wide net for any and all potential data that can facilitate generation of theoretical developments.

- Data analysis . At this stage, the goal is to organize and view your data in such a way that facilitates the identification of key insights. Analysis in basic research serves the dual purpose of filtering data through existing theoretical frameworks and generating new theory.

- Research dissemination . Once you determine your findings, you will want to present your insights in an empirical and rigorous manner. Visualizing data in your papers and presentations is useful for pointing out the most relevant data and analysis in your study.

Whatever your research, make it happen with ATLAS.ti

Turn data into knowledge and innovation with our powerful analysis tools. Download a free trial today.

Fundamental Research

Fundamental research , also known as basic research or pure research does not usually generate findings that have immediate applications in a practical level. Fundamental research is driven by curiosity and the desire to expand knowledge in specific research area. This type of research makes a specific contribution to the academic body of knowledge in the research area.

Fundamental studies tend to make generalizations about the phenomenon, and the philosophy of this type of studies can be explained as ‘gathering knowledge for the sake of knowledge’. Fundamental researches mainly aim to answer the questions of why, what or how and they tend to contribute the pool of fundamental knowledge in the research area .

Opposite to fundamental research is applied research that aims to solve specific problems, thus findings of applied research do have immediate practical implications.

Differences between Fundamental and Applied Research

Differences between applied and fundamental research have been specified in a way that fundamental research studies individual cases without generalizing, and recognizes that other variables are in constant change.

Applied research, on the contrary, seeks generalizations and assumes that other variables do not change. The table below summarizes the differences between the two types of research in terms of purpose and context:

Differences between fundamental and applied research [1]

It is important to note that although fundamental studies do not pursue immediate commercial objectives, nevertheless, findings of fundamental studies may result in innovations, as well as, generating solutions to practical problems. For example, a study entitled “A critical assessment of the role of organizational culture in facilitating management-employee communications” is a fundamental study, but findings of this study may be used to increase the levels of effectiveness of management-employee communications, thus resulting in practical implications.

Examples of Fundamental Research

The following are examples for fundamental researches in business:

- A critical analysis of product placement as an effective marketing strategy

- An investigation into the main elements of brands and branding

- A study of factors impacting each stage of product life cycle

Advantages and Disadvantages of Fundamental Research

Advantages of fundamental research are considered as disadvantages of applied research and vice versa. Fundamental researches are important to expand the pool of knowledge in any discipline. Findings of fundamental studies are usually applicable in a wide range of cases and scenarios. Fundamental studies usually do not have strict deadlines and they are usually driven by the curiosity of the researcher.

At the same time, fundamental studies have disadvantages as well. Findings of this type of studies have little or no practical implications. In other words, fundamental studies do not resolve concrete and specific business problems.

My e-book, The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: a step by step assistance contains discussions of research types and application of research methods in practice. The e-book also explains all stages of the research process starting from the selection of the research area to writing personal reflection. Important elements of dissertations such as research philosophy , research approach , research design , methods of data collection and data analysis , sampling and others are explained in this e-book in simple words.

John Dudovskiy

[1] Table adapted from Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2012) “Research Methods for Business Students” 6 th edition, Pearson Education Limited

Join thousands of product people at Insight Out Conf on April 11. Register free.

Insights hub solutions

Analyze data

Uncover deep customer insights with fast, powerful features, store insights, curate and manage insights in one searchable platform, scale research, unlock the potential of customer insights at enterprise scale.

Featured reads

Tips and tricks

Make magic with your customer data in Dovetail

Four ways Dovetail helps Product Managers master continuous product discovery

Product updates

Dovetail retro: our biggest releases from the past year

Events and videos

© Dovetail Research Pty. Ltd.

Basic vs. applied research: what’s the difference?

Last updated

27 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Research can be used to learn new facts, create new products, and solve various problems. Yet, there are different ways to undertake research to meet a desired goal.

The method you choose to conduct research will most likely be based on what question you want to answer, plus other factors that will help you accurately get the answer you need.

Research falls into two main categories: basic research and applied research. Both types of research have distinct purposes and varied benefits.

This guide will help you understand the differences and similarities between basic and applied research and how they're used. It also answers common questions about the two types of research, including:

Why is it called basic research?

What is more important, basic research or applied research?

What are examples of pure (basic) research and applied research?

Analyze basic and applied research

Dovetail streamlines analysis to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What is basic research?

Basic research (sometimes called fundamental or pure) advances scientific knowledge to completely understand a subject, topic, or phenomenon. It's conducted to satisfy curiosity or develop a full body of knowledge on a specific subject.

Basic research is used to bring about a fundamental understanding of the world, different behaviors, and is the foundation of knowledge in the scientific disciplines. It is usually conducted based on developing and testing theories.

While there is no apparent commercial value to the discoveries that result from basic research, it is the foundation of research used for other projects like developing solutions to solve problems.

Examples of basic research

Basic research has always been used to give humans a better understanding of all branches of science and knowledge. However, it's not specifically based on identifying new things about the universe.

Basic research has a wide range of uses, as shown in the following examples:

Investigation into how the universe began

A study searching for the causes of cancer

Understanding the components that make up human DNA

An examination into whether a vegetarian diet is healthier than one with meat

A study to learn more about which areas in the world get the most precipitation

Benefits of conducting basic research

Called basic research because it is performed without an immediate or obvious benefit, this type of research often leads to vital solutions in the future. While basic research isn't technically solution-driven, it develops the underlying knowledge used for additional learning and research.

There are many benefits derived from basic research, including:

Gaining an understanding of living systems and the environment

Gathering information that can help society prepare for the future

Expanding knowledge that can lead to medical advances

Providing a foundation for applied research

- What is applied research?

Applied research studies particular circumstances to apply the information to real-life situations. It helps improve the human condition by finding practical solutions for existing problems.

Applied research builds off facts derived from basic research and other data to address challenges in all facets of life. Instead of exploring theories of the unknown, applied research requires researchers to use existing knowledge, facts, and discoveries to generate new knowledge.

Solutions derived from applied research are used in situations ranging from medical treatments or product development to new laws or regulations.

Examples of applied research

Applied research is designed to solve practical problems that exist under current conditions. However, it's not only used for consumer-based products and decisions.

Applied research can be used in a variety of ways, as illustrated by the following examples:

The investigation of ways to improve agricultural crop production

A study to improve methods to market products for Gen Z consumers

Examination of how technology can t make car tires last longer

Exploration of how to cook healthy meals with a limited budget

A study on how to treat patients with insomnia

Benefits of using applied research

Although applied research expands upon a foundation of existing knowledge, it also brings about new ideas. Applied research provides many benefits in various circumstances, including:

Designing new products and services

Creating new objectives

Providing unbiased data through the testing of verifiable evidence

- Basic research vs. applied research: the differences

Both basic and applied research are tactics for discovering specific information. However, they differ significantly in the way research is conducted and the objectives they achieve.

Some of the most notable differences between basic and applied research include the following:

Research outcomes: curiosity-driven vs. solution-driven

Basic research is generally conducted to learn more about a specific subject. It is usually self-initiated to gain knowledge to satisfy curiosity or confirm a theory.

Conversely, applied knowledge is directed toward finding a solution to a specific problem. It is often conducted to assist a client in improving products, services, or issues.

Research scope: universal scope vs. specific scope

Basic research uses a broad scope to apply various concepts to gain more knowledge. Research methods may include studying different subjects to add more information that connects evidence points in a greater body of data.

Meanwhile, applied research depends on a specific or narrow scope to gather specific evidence to address a certain problem.

Research approaches: expanding existing knowledge vs. finding new knowledge

Researchers conduct basic research to fill in gaps between existing information points. Basic knowledge is an expansion of existing knowledge to gain a deeper understanding. It is often based on how, what, or why something is the way it is. Although applied research may be based on information derived from basic research, it's not designed to expand the knowledge. Instead, the research is conducted to find new knowledge, usually in the form of a solution.

Research commercialization: Informational vs. commercial gain

The main basis of product development is to solve a problem for consumers.

Basic research might lead to solutions and commercial products in the future to help with this. Since applied research is used to develop solutions, it's often used for commercial gain.

Theory formulation: theoretical vs. practical nature

Basic research is usually based on a theory about a specific subject. Researchers may develop a theory that grows and changes as more information is discovered during the research process. Conversely, applied research is practical in nature since the goal is to solve a specific problem.

- Are there similarities between applied and basic research?

While some obvious differences exist, applied and basic research methods have similarities. For example, researchers may use the same methods to collect data (like interviews, surveys , and focus groups ) for both types of research.

Both types of research require researchers to use inductive and deductive reasoning to develop and prove hypotheses . The two types of research frequently intersect when basic research serves as the foundation for applied research.

While applied research is solution-based, basic research is equally important because it yields information used to develop solutions to many types of problems.

- Methods used in basic research and applied research

While basic and applied research have different approaches and goals, they require researchers or scientists to gather data. Basic and applied research makes use of many of the same methods to gather and study information, including the following:

Observations: Studying research subjects for an extended time allows researchers to gather information about how subjects behave under different conditions.

Interviews: Surveys and one-to-one discussions help researchers gain information from other subjects and validate data.

Experiments: Researchers conduct experiments to prove or disprove certain hypotheses based on information that has been gathered.

Questionnaires: A series of questions related to the research context helps researchers gather quantitative information applicable to both basic and applied research.

- How do you determine when to use basic research vs. applied research?

Basic and applied research are both helpful in obtaining knowledge. However, they aren't usually used in the same settings or under the same circumstances.

When you're trying to determine which type of research to use for a particular project, it's essential to consider your product goals. Basic research seeks answers to universal, theoretical questions. While it works to uncover specific knowledge, it's generally not used to develop a solution. Conversely, applied research discovers answers to specific questions. It should be used to find out new knowledge to solve a problem.

- Bottom line

Both basic and applied research are methods used to gather information and analyze facts that help build knowledge around a subject. However, basic research is used to gain understanding and satisfy curiosity, while applied research is used to solve specific problems. Both types of research depend on gathering information to prove a hypothesis or create a product, service, or valuable process.

By learning more about the similarities and differences between basic and applied research, you'll be prepared to gather and use data efficiently to meet your needs.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 17 February 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

What is Basic Research? Insights from Historical Semantics

- Open access

- Published: 24 June 2014

- Volume 52 , pages 273–328, ( 2014 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Désirée Schauz 1

24k Accesses

45 Citations

18 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

For some years now, the concept of basic research has been under attack. Yet although the significance of the concept is in doubt, basic research continues to be used as an analytical category in science studies. But what exactly is basic research? What is the difference between basic and applied research? This article seeks to answer these questions by applying historical semantics. I argue that the concept of basic research did not arise out of the tradition of pure science. On the contrary, this new concept emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a time when scientists were being confronted with rising expectations regarding the societal utility of science. Scientists used the concept in order to try to bridge the gap between the promise of utility and the uncertainty of scientific endeavour. Only after 1945, when United States science policy shaped the notion of basic research, did the concept revert to the older ideals of pure science. This revival of the purity discourse was caused by the specific historical situation in the US at that time: the need to reform federal research policy after the Second World War, the new dimension of ethical dilemmas in science and technology during the atomic era, and the tense political climate during the Cold War.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Island of Research (Do Not Block the Path of Enquiry)

Is There a Scientific Method? The Analytic Model of Science

Basic Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For some years now, the concept of basic research has been under attack. Its relevance has been questioned empirically as a result of changes in academic research, normatively with respect to science policy, and even theoretically in science and technology studies. Yet while the significance of the concept is in doubt, basic research is still a very common analytical category, deployed not least as a means of distinguishing the new future science policy from the old ideal of basic research. But what exactly is basic research? What is the difference between basic and applied research? Aside from a few exceptional studies (Calvert 2006 ; Godin 2005a ; Pielke 2012 ), science studies have only just begun to seriously reflect upon these questions. When and why did the concept of basic research emerge in the first place? Is the ideal of basic research nothing more than a relaunch of the older pure-science discourse? Historical semantics appears to be a useful approach for answering these questions because its historical perspective provides the conceptual clarity required both in current debates in science and technology studies and public debates on science policy.

In the 1990s, sociological studies claimed that science was undergoing profound changes. Since then, prominent labels such as “Mode 2” or “triple helix” have come to signify a new way of organizing science and technology that transgresses institutional boundaries between universities, industry, and governmental research. According to the alleged paradigm shift from Mode 1 to Mode 2, application-oriented research programmes with cooperative and transdisciplinary project teams have replaced the former university-centred basic research mode. Proponents of this new way of comprehending knowledge production even call for science policy to be modified in order to reflect the altered research mode (Gibbons et al. 1994 ; Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff 1997 ). Our “Leonardo world”, as portrayed by Jürgen Mittelstraß, is ruled by the imperative of technology. The interplay of science and technology raises society’s expectations of research applications, even when the outcomes sometimes turn out to be risky (Mittelstraß 1994 ). These arguments have certainly shaped the debates in science and technology studies and science policy in recent years, although discussions about the degree of change and how to evaluate it remain controversial (Weingart 2008 ; Greenberg 2007 ).

According to studies addressing these historical shifts in science, basic research determined the status quo ante. These studies describe basic research as an application-disinterested mode of research embedded in a disciplinary and academic setting that contrasts, in respect of every analytical feature, to Mode 2. The concept of Mode 1, however, is not based upon profound historical analysis; it rather appears to represent the previously prevailing sociological perspective on science in the tradition of Robert Merton, who emphasized disinterestedness and universalism as central characteristics of modern science. Yet historical studies suggest that the way in which science was organized had already undergone significant change in the early 20th century, as politicians, scientists, and industry formed a new alliance from which all three groups hoped to benefit (Ash 2002 ; Mowery and Rosenberg 1993 ).

Moreover, although recent debates in science studies have demonstrated high levels of discontent with the notion of basic research, producing instead new analytic labels like triple helix or Mode 2, the term “basic research” and its antonym “applied research” continue to frame the discourse about science, without any awareness of both terms’ historical conditionality as discursive strategies in research policy. The semantic dichotomy merely gives way to a continuum between basic and applied research in which the favourite mode, the “use-inspired basic research” (in German “ anwendungsorientierte Grundlagenforschung ”), is located somewhere in the middle of the continuum (Stokes 1997 ; Mittelstraß 1994 ). However, aside from the motif of application, we lack an explicit set of distinctive criteria because studies persist in assuming basic research to be a given category.