Center for Union Facts

The Center for Union Facts (CUF) has compiled the single most comprehensive database of information about labor unions in the United States. The database contains more than 100 million facts , ranging from basic union finances and leader salaries, to political operations, to strikes and unfair labor practices, and much more. The data comes from various local, state, and federal government agencies that track labor union operations.

Other CUF Projects

U.S. Department of the Treasury

Labor unions and the u.s. economy.

By Laura Feiveson, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Microeconomics

Today, the Treasury Department released a first-of-its-kind report on labor unions, highlighting the evidence that unions serve to strengthen the middle class and grow the economy at large. Over the last half century, middle-class households have experienced stagnating wages, rising income volatility, and reduced intergenerational mobility, even as the economy as a whole has prospered. Unions can improve the well-being of middle-class workers in ways that directly combat these negative trends. Pro-union policy can make a real difference to middle-class households by raising their incomes, improving their work environments, and boosting their job satisfaction. In doing so, unions can help to make the economy more equitable and robust.

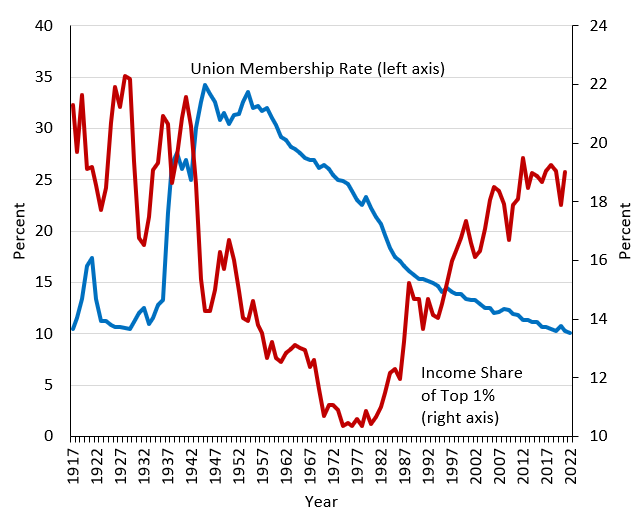

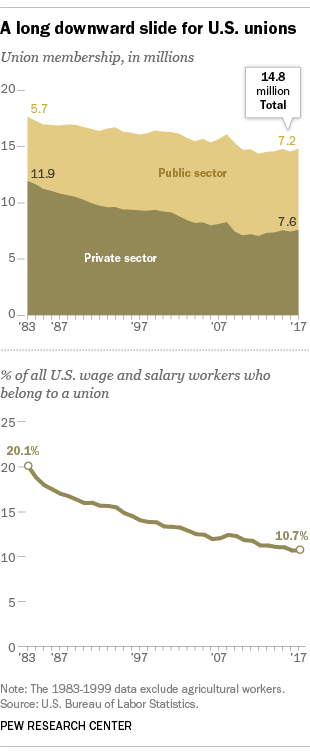

Over the last century, union membership rates and income inequality have diverged, as shown in Figure 1. Union membership peaked in the 1950s at one-third of the workforce. At that time, despite pervasive racial and gender discrimination, overall income inequality was close to its lowest level since its peak before the Great Depression, and was continuing to fall. Over the subsequent decades, union membership steadily declined, while income inequality began to steadily rise after a trough in the 1970s. In 2022, union membership plateaued at 10 percent of workers while the top one percent of income earners earned almost 20 percent of total income.

Figure 1: Union Membership and Inequality

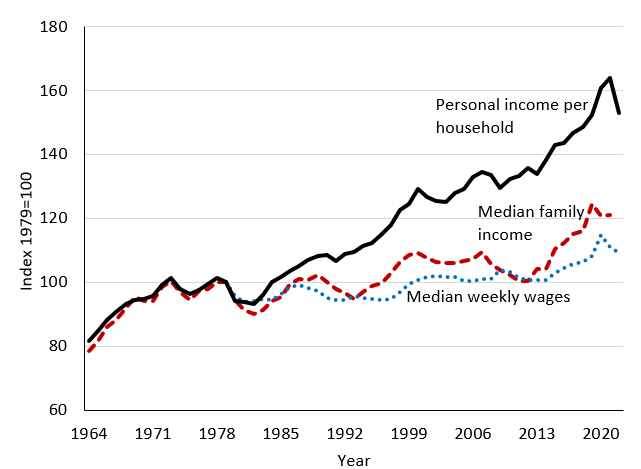

While the overall U.S. economy has grown over the past few decades, the rise in inequality can be a proxy for the experience of many middle-class households. The income of the median family rose only 0.6 percent per year, in contrast to average personal income per household which rose 1.1 percent per year, as seen in Figure 2. And, notably, other markers of middle-class stability have deteriorated since the 1970s. Income has become more volatile, [1] the amount of time spent on vacation has fallen, [2] and middle-class Americans are less prepared for retirement. [3] Intergenerational mobility has declined—90 percent of children born in the 1940s earned more than their parents did at age 30, while only half of children born in the mid-1980s did the same. [4]

Figure 2: Income and Wage Growth since the 1960s

So, how could unions help? Treasury’s report shows that unions have the potential to address some of these negative trends by raising middle-class wages, improving work environments, and promoting demographic equality. Of course, unions should not be the only solution to these structural trends. But the evidence below and in the report suggests that unions can be useful in building the economy from the middle out.

Wages

One of the most oft-cited benefits of unions is the so-called “union wage premium”—the amount that union members make above and beyond non-members. While simple comparisons of the wages of union workers and nonunion workers find that union workers typically make about 20 percent more than nonunion workers, [5] economists turn to other types of analysis to capture causal effects of unions on wages. The first approach controls for many worker and occupation characteristics with the goal of comparing the wages earned by two similar workers that differ only in their union status. The other empirical approach is “regression discontinuity analysis,” which compares the wages in workplaces which just barely passed a vote to unionize against wages in workplaces that barely failed to pass the unionization vote. All in all, the evidence from these two approaches points to a union wage premium of around 10 to 15 percent, with larger effects for longer-tenured workers. [6]

Work environments

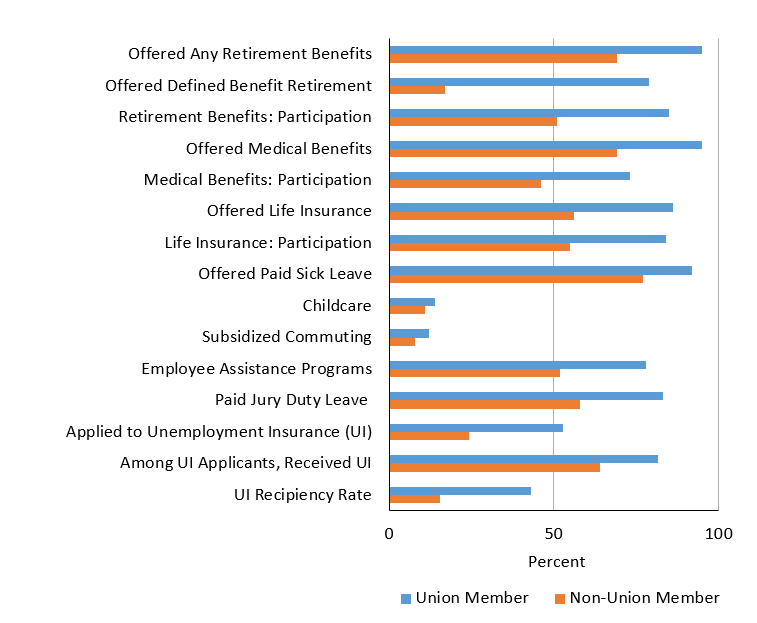

Worker wellbeing is greatly affected by non-wage benefits. Some benefits, such as healthcare benefits and retirement benefits, are a part of the compensation package and have substantial monetary value. Other features of the work environment, like flexible scheduling or workplace safety regulations, may not have direct monetary value but could still be highly valued by workers. For example, one study estimated that the average worker is willing to give up 20 percent of wages to avoid having their schedule frequently changed by their employer on short notice. [7] Another study, co-authored by Secretary Yellen, found that 80 percent of people who like their jobs cite a non-wage reason as the primary cause of their satisfaction and, conversely, 80 percent of people who dislike their jobs cite non-wage reasons to explain their dissatisfaction. [8]

There is strong evidence that unions improve both fringe benefits and non-wage features of the workplace. Figure 3 shows how much more likely it is for a union worker to be offered certain amenities than a nonunion worker. While these simple comparisons reflect correlations only, studies that use more robust empirical approaches find the same: unions have had a large hand in improving work environments on many dimensions and, in doing so, raise the wellbeing of workers and their families. [9]

Figure 3: Fringe Benefits and Amenities

Workplace Equality

The diverse demographics of modern union membership mean that the benefits of any policy that strengthens today’s unions would be felt across the population.Union membership is now roughly equal across men and women. In 2021, Black men had a particularly high union representation rate at 13 percent, as compared to the population average of 10 percent. [10]

Unions promote within-firm equality by adopting explicit anti-discrimination measures, supporting anti-discrimination legislation and enforcement, and promoting wage-setting practices that are less susceptible to implicit bias. As an example of egalitarian wage-setting practices, single rate or automatic progression wage structures contribute to lower within-firm income inequality compared to firms that make individual determinations. [11] These types of practices, and others like publicly available pay schedules, benefit women and vulnerable workers who can be less likely to negotiate aggressively for pay raises.

Empirical studies have confirmed that unions have, indeed, closed race and gender gaps within firms. For example, one study finds that the wage gap between Black and white women was significantly reduced due to union measures. [12] Another study provides evidence of how collective bargaining has reduced gender wage gaps amongst teachers. [13]

The positive effects of unions are not limited to union workers. Nonunionized firms in competition with unionized workplaces may choose to raise wages, change hiring practices, or improve their workplace environment to attract workers. [14] Unions can also affect workplace norms by, say, lobbying for workplace safety improvements, or advocating for changes in minimum wage laws. [15] The empirical evidence finds that these positive spillovers exist. Each 1 percentage point increase in private-sector union membership rates translates to about a 0.3 percent increase in nonunion wages. These estimates are larger for workers without a college degree, the majority of America’s workforce. [16]

Unions may also produce benefits for communities that extend beyond individual workers and employers by enhancing social capital and civic engagement. Union members vote 12 percentage points more often than nonunion members, and nonunion members in union households vote 3 percentage points more often than individuals in nonunion households. [17] In addition, union members are more likely to donate to charity, attend community meetings, participate in a neighborhood project, and volunteer for an organization. [18]

Increased unionization has the potential to contribute to the reversal of the stark increase in inequality seen over the last half century. In turn, increased financial stability to those in the middle or bottom of the income distribution could alleviate borrowing constraints, allowing workers to start businesses, build human capital, and exploit investment opportunities. [19] Reducing inequality can also promote economic resilience by reducing the financial fragility of the bottom 95 percent of the income distribution, making these Americans less sensitive to negative income shocks and thus lessening economic volatility. [20] In short, unions can promote economy-wide growth and resilience.

All in all, the evidence presented in Treasury’s report challenges the view that worker empowerment holds back economic prosperity. In addition to their effect on the economy through more equality, unions can have a positive effect on productivity through employee engagement and union voice effects, providing a road map for the type of union campaigns that could lead to additional growth. [21] One such example found that patient outcomes improved in hospitals where registered nurses unionized. [22]

The Biden-Harris Administration recognizes the benefits of unions to the middle class and the broader economy and has taken actions, outlined in Treasury’s report, to empower workers. There have been promising signs: union petitions in 2022 rose to their highest level since 2015, [23] and public opinion in support of unions is at its highest level in over 50 years. [24] The evidence summarized here and in Treasury’s report suggest these burgeoning signs of strengthening worker power are good news for the middle class and the economy as a whole.

[1] Dynan, Karen, Douglas Elmendorf, and Daniel Sichel. 2012. “The Evolution of Household Income Volatility.” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 12 (2).

[2] Van Dam, Andrew. 2023. “The mystery of the disappearing vacation day.” The Washington Post, February 10, 2023.

[3] Johnson, Richard W., and Karen E. Smith. 2022. “How Might Millennials Fare in Retirement?” Urban Institute , September 2022.

[4] Chetty, et al. (2017).

[5] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2023. Table 2.: Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers by union affiliation and selected characteristics. Last modified January 19, 2023.

[6] For example: Gittleman, Maury, and Morris M. Kleiner. 2016. "Wage effects of unionization and occupational licensing coverage in the United States." ILR Review 69 (1): 142–172; Kleiner, Morris M., and Alan B. Krueger. 2013. “Analyzing the Extent and Influence of Occupational Licensing on the Labor Market.” Journal of Labor Economics 31 (2): S173–S202; DiNardo, John, and David S. Lee. 2004. “Economic Impacts of New Unionization on Private Sector Employers: 1984–2001.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119 (4): 1383–1441; Frandsen, Brigham R. 2021. “The Surprising Impacts of Unionization: Evidence from Matched Employer-Employee Data.” Journal of Labor Economics 39 (4): 861–894.

[7] Mas, Alexandre, and Amanda Pallais. 2017. "Valuing alternative work arrangements." American Economic Review 107 (12): 3722–59.

[8] Akerlof, George A., Andrew K. Rose, and Janet L. Yellen. 1988. "Job switching and job satisfaction in the US labor market." Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1988 (2): 495–594.

[9] Knepper, Matthew. 2020. “From the Fringe to the Fore: Labor Unions and Employee Compensation.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 102 (1): 98–112.

[10] Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and author’s calculations using BLS data, accessed through IPUMS. Data reflect 2022 values. Sample is employed 16+ year olds. Excludes workers represented by, but not a member of, unions.

[11] See, e.g., Card (1996) and Freeman (1982). Freeman, Richard B. 1982. "Union wage practices and wage dispersion within establishments." ILR Review 36 (1): 3–21.

[12] Rosenfeld, Jake, and Meredith Kleykamp. 2012. “Organized Labor and Racial Wage Inequality in the United States.” American Journal of Sociology 117 (5): 1460–1502.

[13] Biasi, Barbara, and Heather Sarsons. 2022. "Flexible wages, bargaining, and the gender gap." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 137 (1): 215–266.

[14] Fortin, Nicole M., Thomas Lemieux, and Neil Lloyd. 2021. "Labor market institutions and the distribution of wages: The role of spillover effects." Journal of Labor Economics 39 (S2): S369–S412; Taschereau-Dumouchel, Mathieu. 2020. "The Union Threat." The Review of Economic Studies 87 (6): 2859–2892.

[15] The impact of changes in government policy arising out of union advocacy is not the focus of this paper; however, Ahlquist (2017) suggests that advocacy plays an important role in unions’ impacts on the labor market. Spillovers and “threat effects” within the labor market, however, are discussed in this paper. Ahlquist, John S. 2017. “Labor Unions, Political Representation, and Economic Inequality.” Annual Review of Political Science 20 (1): 409–432.

[16] Note: Rosenfeld, Denice, and Laird (2016) do not interpret their estimates causally. Their approach suffers from many of the CPS’s sample size limitations. Although the CPS ostensibly reports quite detailed occupational codes, Rosenfeld, Denice, and Laird estimate regressions with only four occupational codes and 18 industry codes. This data limitation greatly increases the risks that the regression-adjusted approach cannot control for selection effects into unionization.

[17] This 12-percentage-point union voting premium largely reflects socioeconomic factors associated with individuals who join a union. However, when comparing members with non-members who exhibit similar characteristics, there remains a union voting premium of 4 percentage points. Freeman, Richard B. 2003. “What Do Unions Do…to Voting?” National Bureau of Economic Research , working paper no. 9992.

[18] Zullo, Roland. 2011. “Labor Unions and Charity.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 64 (4): 699–711.

[19] Aghion, P., E. Caroli, and C. Garcia-Penalosa. 1999. “Inequality and Economic Growth: The Perspective of the New Growth Theories.” Journal of Economic Literature 37 (4): 1615–60.

[20] Kumhof, Michael, Romain Rancière, and Pablo Winant. 2015. “Inequality, Leverage, and Crises.” American Economic Review 105 (3): 1217–45.

[21] Doucouliagos, Christos, Richard B. Freeman, and Patrice Laroche. 2017. The Economics of Trade Unions: A study of a Research Field and Its Findings . London: Routledge.

[22] Dube, Arindrajit, Ethan Kaplan, and Owen Thompson. 2016. “Nurse unions and patient outcomes.” ILR Review 69 (4): 803–833.

[23] National Labor Relations Board. 2022. “Election Petitions Up 53%, Board Continues to Reduce Case Processing Time in FY22.” Press release. October 6, 2022. https://www.nlrb.gov/news-outreach/news-story/election-petitions-up-53-board-continues-to-reduce-case-processing-time-in .

[24] McCarthy, Justin. 2022. “U.S. Approval of Labor Unions at Highest Point Since 1965.” Gallup , August 30, 202 2.

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Research sheds light on how labor unions reduced income inequality from WWII through the 1970s

Unions played a key role in reducing income inequality during the middle of the 20th century, when the wage difference between the highest and lowest earners significantly shrank.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Clark Merrefield, The Journalist's Resource October 4, 2021

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/economics/inequality-labor-unions/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

Recent research in the Quarterly Journal of Economics offers previously unseen levels of detail unraveling the relationship between labor unions and income inequality in the U.S.

The study, “ Unions and Inequality over the Twentieth Century: New Evidence from Survey Data ,” suggests rising union membership from the 1930s to the 1960s strongly contributed to closing the income gap between the richest and poorest Americans during those decades, with particular gains for racial and ethnic minorities. The results are largely based on responses to more than 500 Gallup surveys from 1936 to 1986.

Further, a “premium” of 10% to 20% higher income for union households compared with non-union households from the 1940s through the mid-2010s remains “relatively consistent over our long sample period, despite the large swings in density and composition of union members that we document,” the authors write.

Union density generally refers to the share of workers in an industry who are in a union. The Gallup surveys did not consistently ask about health insurance coverage and paid vacation time, so the authors do not explore benefits other than higher wages that can come with union jobs.

New measures of union density

Before 1973, economists estimated union membership at the national level. For example, Rutgers University labor economist Leo Troy used union dues revenue and other data to estimate national union membership from 1897 to 1962 for a book the National Bureau of Economic Research published in 1965.

Eight years later, the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics began asking about union membership as part of their Current Population Survey , a monthly survey of 60,000 households. Labor economists could, for the first time, analyze individual union membership.

But by then, union density was trending downward.

The new analysis of Gallup data shows the share of U.S. households with a union member had fallen under 30% by that time, down from a high of nearly 35% in the mid-1950s.

“Almost everything economists knew had come from this post-1970 period when unions were in decline,” says Suresh Naidu , an economics professor at Columbia University and co-author of the recent paper with Henry Farber , Daniel Herbst and Ilyana Kuziemko . “So we were like, ‘Let’s see what this looks like when you look at the period when unions were increasing.’”

The Gallup data come from a trove of surveys, available through the Roper Center for Public Opinion at Cornell University, that starting in 1937 asked respondents whether anyone in their household was a union member. The authors go back an additional year using a survey about household spending on union dues in 1936 conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the now-defunct Bureau of Home Economics .

Using those surveys and the Current Population Survey since 1973, along with other data sources, the authors find the share of union households skyrocketed from just over 10% in 1936 to roughly one-third in 1955. Union density held steady around 30% through the 1960s before dropping below 25% by 1985.

The rise of unions from 1936 to 1968 explains about 25% of the decline during that period in the Gini coefficient , a common measure of income inequality, according to the paper. The lower the Gini coefficient for a nation, the narrower the gap between its highest and lowest income earners.

After 1968, falling union membership explains roughly 10% of increasing income inequality over the next five decades, the authors find.

In 2020, about 11% of wage and salary earners were union members — 35% of them in the public sector and 6% in the private sector, according to the Current Population Survey. Union workers earned a median of $1,144 per week in 2020, compared with $958 for non-union workers. Put another way, union workers earn $1 for every 84 cents a non-union worker earns.

Although dozens of local union shops remained racially segregated in the South during the years after World War II, unions generally also “drew in disadvantaged groups such as the less educated and nonwhite households,” find Naidu and co-authors Henry Farber , Daniel Herbst and Ilyana Kuziemko .

“That suggests a reason why unions mid-century were a powerful force for equality,” Naidu says. “They brought in the people worst off in the labor market and raised their wages a lot.”

Black workers in particular continue to be represented by unions at a relatively high rate. In 2020, nearly 14% of Black workers could claim union representation, compared with 12% of white workers, 11% of Hispanic or Latino workers and 10% of Asian workers, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The rise and fall of manufacturing in the U.S.

The U.S. economy from the Great Depression through the postwar years looked very different than it does today. Before, during and after the war, unions organized some of the biggest firms engaged in domestic production for domestic buyers — think Ford, General Motors and U.S. Steel.

The 1940s specifically were “a decade of extraordinary wage compression,” as economists Claudia Goldin and Robert Margo explain in a February 1992 paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics. The difference between the highest and lowest wage earners narrowed so significantly that Goldin and Margo dubbed those years the “Great Compression.”

As Farber, Herbst, Kuziemko and Naidu find, the Great Compression was partly spurred by unionization.

Likewise, an August 2018 paper in The Economic History Review finds that parts of the U.S. where unions grew briskly during the 1940s also show greater reductions in wage inequality than places where unions expanded less quickly.

“In 1950 we lived in an economy where Americans bought American-made goods,” explains Farber, an economics professor at Princeton University. “It’s pre-globalization. There was this overarching agreement between unions and management that management would accept the unions, unions would allow management to manage, and there would be labor peace without the opportunity to strike during a contract. Roughly speaking, it was sharing the gains that came from having a protected product market, because Americans didn’t want to buy cars made elsewhere.”

National markets are also more interconnected than they were midcentury. The U.S. is now a net importer of goods. The U.S. imported $2.3 trillion worth of goods in 2020, $911 billion more than it exported. Census data on trade balances go back to 1960 , when the nation imported $15 billion worth of goods — nearly $5 billion less than it exported.

Finally, U.S. jobs are no longer dominated by manufacturing. In 1950, manufacturing firms produced $225 billion worth of goods, roughly 40% of the nation’s entire industrial output, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. By late 2019, before COVID-19, manufacturing represented 16% of the nation’s industrial output.

Today, the biggest firms in the U.S. — Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet and Facebook — are data companies. If they do build physical products, like cell phones, that largely happens overseas. Income inequality has grown , with the highest income earners in the U.S. having gradually taken home a larger share of the national income from 1980 onward.

Here’s how the manufacturing decline has played out in the labor market: Nearly 30% of full- and part-time U.S. workers were employed in manufacturing in 1950. By 2019, 8% worked in manufacturing while 18% worked in retail, hospitality or food services.

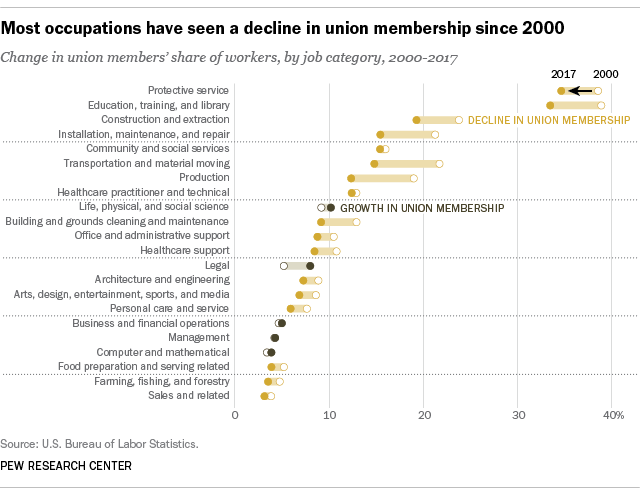

Citing federal labor statistics, Vanderbilt University sociologist Daniel Cornfield writes in a 1986 paper in the American Journal of Sociology that in “manufacturing — the traditional source of union membership — the percentage of unionized workers declined from 51.3% to 39.9% between 1956 and 1978.”

The decline in manufacturing as a share of unionized workers has continued over the last 20 years. In 2000, 15% of union jobs were in manufacturing. By 2020, that figure had dipped to 8.5%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Unionization rates for government jobs have held relatively steady over the last two decades, with about 37% of the public sector unionized today. Private sector unionization has fallen from 2000 to 2020, from 9% to 6%. The educational services sector is a notable exception, growing from 12% unionization in 2000 to 14% in 2020.

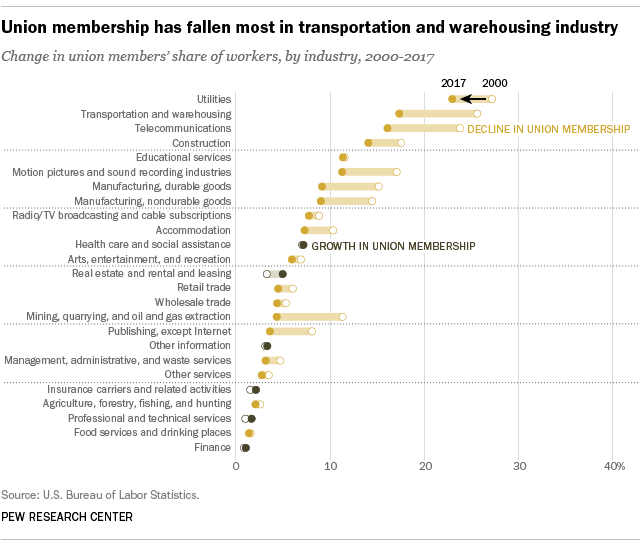

Utilities, transportation, warehousing and telecommunications remain the most unionized industries, though union density in each has declined by over 5% since 2000 — and by almost 10% in telecommunications alone.

How unions grew

The “ Unions and Inequality ” authors identify two primary ways unions expanded before and during World War II and the Great Compression.

The first was the Wagner Act , which President Franklin Roosevelt signed in 1935 and which the Supreme Court upheld in 1937 . The act, sponsored by New York Sen. Robert Wagner , established the National Labor Relations Board . It brought legal protection to private sector unionization and collective bargaining activities, with some unions turning their focus toward organizing unskilled workers after it became law.

Before the Wagner Act, most workers involved in industrial manufacturing were not in unions. Large companies sometimes used physical violence to break organizing campaigns. “Henry Ford, whose brutal private army was well known by his workers, set the tone for how to crush unions,” recounts University of Rhode Island labor historian Erik Loomis in his 2018 book, “A History of America in Ten Strikes.”

Governments at all levels also had historically sided with employers, “with military deployments and judicial repression commonplace,” the authors of the recent paper write in the appendix .

The second event that led to union expansion was Roosevelt establishing the National War Labor Board in January 1942, weeks after the U.S. entered World War II. The board seated 12 representatives drawn from private firms, unions and the public sector. It was tasked with settling labor disputes before they affected wartime production.

“The government was letting very large defense contracts for armaments and so on and requiring, as a condition of the contract, by executive order, that companies be open to unionization,” Farber says. “In places that had a lot of government contracts, there was a growth in unionization and inequality in those places at those times declined.”

The Wagner Act also protected recognition strikes, says Naidu. Over the five years after the act passed, strikes were successful in gaining union recognition 40% of the time, compared with about 20% during the seven years before the act, the authors find.

The Korean War provides an important check on their findings. A smaller conflict than World War II, the Korean War from 1950 to 1953 still required massive production of tanks, planes, ammunition and guns.

Difference was, firms that got government contracts during the Korean War didn’t have to allow unionization efforts. The authors find “no correlation between Korean War Defense spending and changes in state union density or inequality measures.”

About The Author

Clark Merrefield

Unions & Worker Organizations

The Labor Center conducts research on unions and worker organizations and how they affect the lives of working people. This research has included the effects of unions on workers’ wages and benefits, how that differs by race, ethnicity and gender, and the role of unions in shaping public policy. The Center analyzes state and local policies that support worker voice on the job and the ability of workers to organize. We also study the effectiveness of organizing and bargaining strategies and methods.

See also our Labor-Managements Partnerships program

Rules to Win By: Power and Participation in Union Negotiations

A new negotiations book by Jane McAlevey and Abby Lawlor written by and for workers, not management–there’s no other book like this!

September 10, 2023

Seema Patel reflects on building power for workers ‘on the margins’

August 29, 2023

California Union Membership and Coverage: 2023 Chartbook

Snapshot of California Union Membership: ‘It’s not your grandfather’s union anymore’

September 16, 2023

Tech Fears Are Showing Up on Picket Lines

September 4, 2023

Workers ‘can still win really big.’ How labor can demand more

Research & Publications

- Labor Education

- Unions & Worker Organizations

- Announcement

Our colleague and friend Jane McAlevey has entered hospice

Jane McAlevey sent this letter to friends, family, collegues and supporters to explain that she has entered hospice care.

Building a strong, organized teachers union: A conversation with Alex Caputo-Pearl

The Labor Center sat down with Practitioner in Residence Alex Caputo-Pearl to delve into some of the work he’s completing during his residency, his role during the 2019 UTLA teacher’s strike, and his upcoming book about the teacher’s labor movement in recent years.

Two outstanding labor organizers join the UC Berkeley Labor Center as practitioners in residence

We are pleased to welcome labor organizers Jaz Brisack and Brad Hirn to the Labor Center for a year-long residency.

New ways for organizers to lead

At the latest Labor Center Lead Organizer Training 19 organizers strengthened their organizing skills and learned to cultivate new leaders within their organizations. The frontline leaders from teacher, grocery, and flight attendant unions, and Black, Latino, and Filipino worker centers, among others, learned to adapt different leadership approaches to different circumstances.

- Public Sector

California’s teachers are fighting for better schools

Teachers’ willingness to strike represents not just a resurgence of union power, but also their determination to call attention to the dire consequences of decades of California’s underinvestment in K-12 education.

The Union Effect in California

May 31, 2018

The Union Effect in California #1: Wages, Benefits, and Use of Public Safety Net Programs

June 7, 2018

The Union Effect in California #2: Gains for Women, Workers of Color, and Immigrants

June 20, 2018

The Union Effect in California #3: A Voice for Workers in Public Policy

Tools & Resources

California Workers’ Rights: A Manual of Job Rights, Protections and Remedies (Available in print and as an e-book)

August 3, 2013

Work, Money and Power: Unions in the 21st Century

April 25, 2021

“Hey, the Boss Just Called Me Into the Office!” The Weingarten Decision and the Right to Representation on the Job

Press Coverage

Tenants are forcing bay area landlords to the bargaining table.

Brad Hirn said, “The ordinance doesn’t automatically bestow upon tenants a victory: it provides a framework for tenants to think about how to organize a majority of their neighbors, and it imposes the obligation on the landlord to bargain in good faith.”

ABX Air Pilots Choose Cooperation Over Confrontation

Ken Jacobs said there’s a long history of unions promoting good union employers. That level of collegiality is not frequently seen in the airline industry, Jacobs acknowledged.

They work 80 hours a week for low pay. Now, California’s early-career doctors are joining unions

Ken Jacobs said establishing a union among Kaiser residents could have far-reaching impacts given the size of the health care behemoth, which is often looked at as a leader for worker pay and benefits. “It’s a big deal to take on something the size of Kaiser,” Jacobs said.

Exclusive: S.F. mega-landlord Veritas is selling off 762 rent-controlled apartments

Veritas, the largest landlord in San Francisco, has defaulted on another loan and is losing 23 apartment buildings. Our practitioner in residence Brad Hirn discusses Veritas, the Union-At-Home ordinance, and ongoing tenant organizing.

Enjoy Labor’s Tailwinds—but Don’t Forget to Keep Rowing!

The recent upsurge in organizing is worth celebrating, but workers can’t afford to rest.

Program Contacts

Labor Center Chair

510-643-2621

Jane McAlevey

Senior Policy Fellow

Alex Caputo-Pearl

Practitioner in Residence

Senior Fellow

.cls-1{fill:#fff;}.cls-2{fill:#1b9dcd;}

Most americans see unions as a gateway to financial stability and job security.

Poll: Labor Unions in America

This Navigator Research report contains polling data on Americans’ latest perceptions of labor unions, including what Americans view as the most important benefits of labor unions, perceptions of anti-union policies and declines in union membership, and which party Americans view as the most equipped to strengthen labor unions and empower workers.

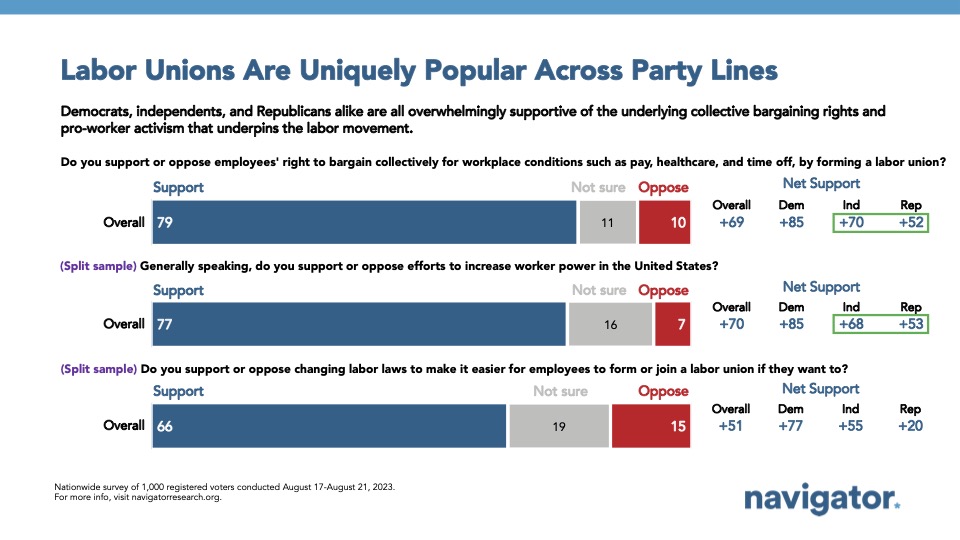

Two in three Americans support making it easier for employees to form or join a labor union, with even larger shares who support the “right to bargain collectively” and to increase worker power in the United States.

By a 51-point margin, most Americans support labor laws that would make it easier for employees to form or join a labor union (66 percent support – 15 percent oppose), including four in five Democrats (81 percent), two in three Republicans (67 percent), and even half of Republicans (49 percent). An even larger share of Americans — 79 percent — say they support employees’ right to collectively bargain, and 77 percent also say they support increasing worker power in the United States. When asked to rank the top four most appealing aspects of labor unions, “better pay ” was listed across party lines and among both union households and non-union households as the biggest draw for union membership.

- Other aspects seen as most appealing about being in a union include “better benefits like PTO, parental or sick leave, and health care” (46 percent), “job security” (40 percent), and “better pension or retirement plans (37 percent). While “making it harder for managers and executives to take advantage of working people” was ranked lower overall (28 percent), it is in the top four most appealing aspects for those living in union households (36 percent).

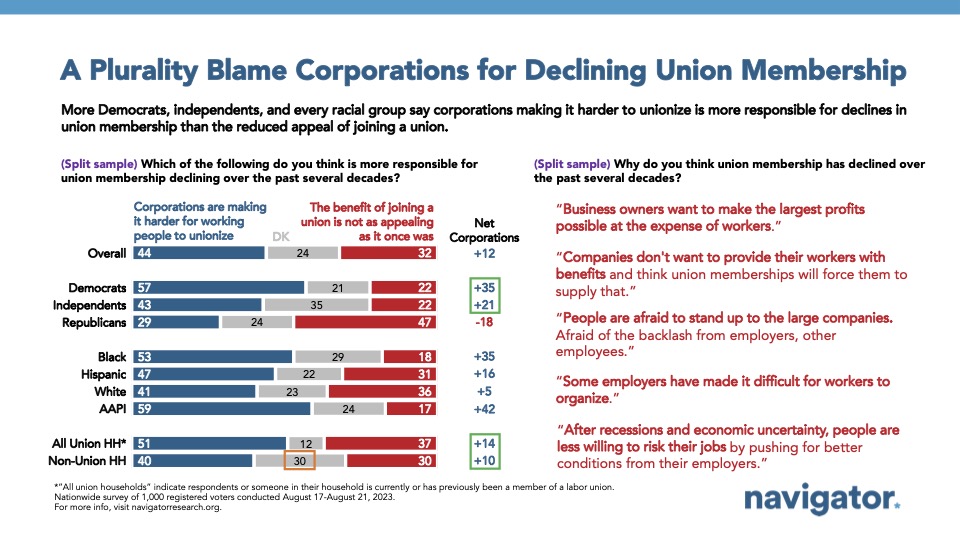

A plurality of Americans blame corporations more for declining union membership than believe the benefit of joining a union is not as appealing as it once was.

Less than one in three view a decline in union membership as a product of unions not being as appealing as they once were (32 percent), while a greater share view corporations making it harder for workers to unionize as being to blame (44 percent). Significantly larger shares of Democrats (57 percent blame corporations – 22 percent not as appealing) and independents (43 percent blame corporations – 22 percent not as appealing) are much more likely to blame corporations than a weakened appeal in union membership.

- While different views exist as to why membership is in decline, Americans say they view this decline as bad for workers and the economy: by a 22-point margin, Americans view the decline of union membership as having a negative impact on the country (21 percent positive impact – 43 percent negative impact). Democrats and those living in union households are most likely to say the decline in union membership is having a negative impact on the country (55 percent and 54 percent, respectively).

When asked about the potential effects of increasing union membership, seven in ten say there would be both a positive impact on wages paid to working people (71 percent) and the availability of jobs with benefits like PTO, parental or sick leave, and health care (70 percent), while about two in three say there would be a positive impact on workplace safety (69 percent), the well-being of workers who are newly represented by unions (67 percent), and training and apprenticeship programs (65 percent).

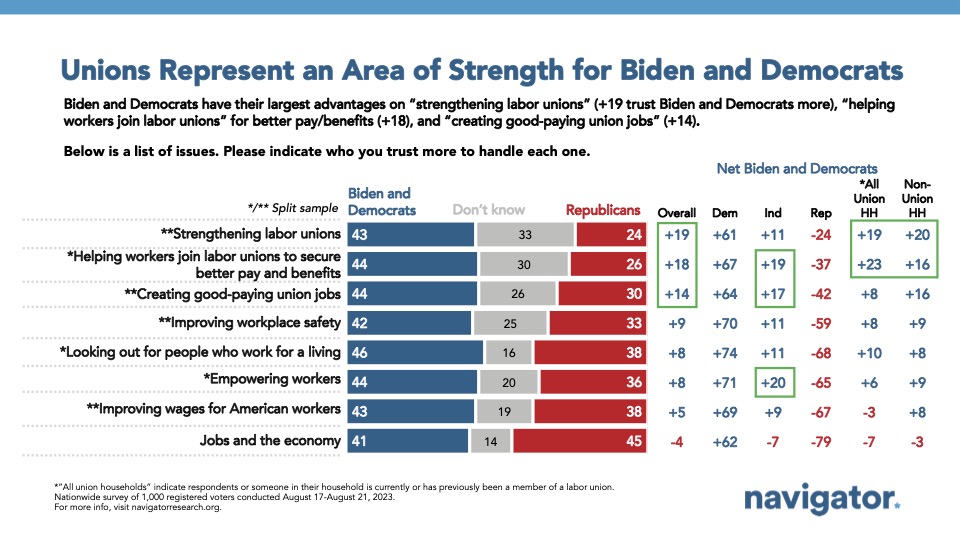

Biden and Democrats are more trusted on union and worker empowerment than Republicans.

By a 19-point margin, Democrats are more trusted than Republicans to strengthen labor unions (43 percent Biden/Democrats – 24 percent Republicans). These margins are consistent across a range of issues related to unions and worker quality of life, including “helping workers join labor unions to secure better pay and benefits” (net +18; 44 percent Biden and Democrats – 26 percent Republicans), “creating good-paying union jobs” (net +14; 44 percent Biden/Democrats – 30 percent Republicans), and “looking out for people who work for a living” (net +8; 46 percent Biden and Democrats – 38 percent Republicans)

- Democrats are generally viewed as being more pro-union, while Republicans are generally viewed more as being anti-union: 42 percent of Americans say they believe Republicans are anti-union compared to just 14 percent who believe they are pro-union, while 49 percent think Democrats are pro-union and just 10 percent believe they are anti-union.

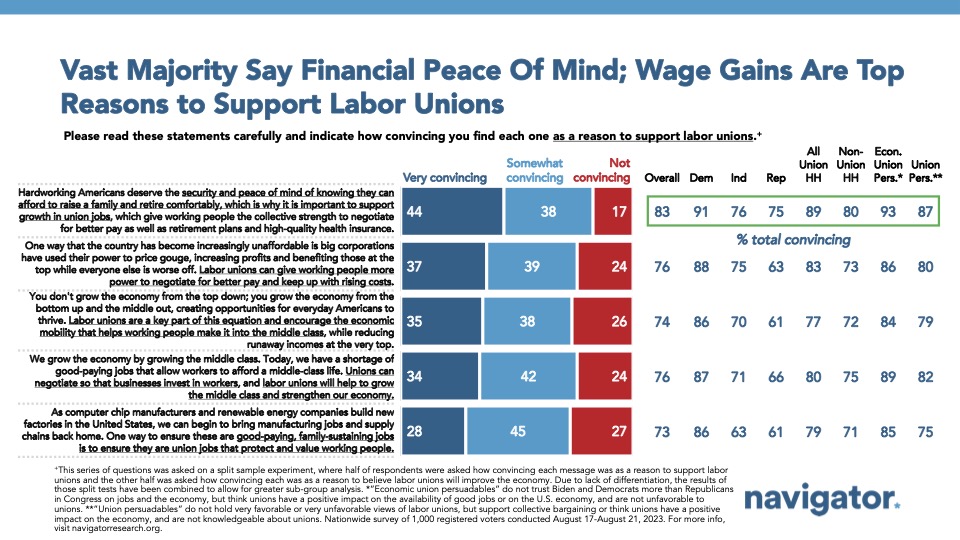

Centering financial peace of mind and the ability to negotiate higher pay to keep up with rising costs are seen as the most convincing pro-union arguments.

Among a variety of arguments that were all viewed as convincing reasons to support labor unions, the top two performers included:

- Hardworking Americans deserve the security and peace of mind knowing they can afford to raise a family and retire comfortably, which is why it’s important to support growth in union jobs , which give working people the collective strength to negotiate for better pay as well as retirement plans and high-quality health insurance (83 percent found this convincing; 89 percent of those living in union households and 76 percent of independents found this argument to be convincing); and,

- One way that the country has become increasingly unaffordable is big corporations have used their power to price gouge, increasing profits and benefiting those at the top while everyone else is worse off. Labor unions can give working people more power to negotiate for better pay and keep up with rising costs (76 percent found this convincing; 83 percent of those living in union households and 75 percent of independents found this argument to be convincing).

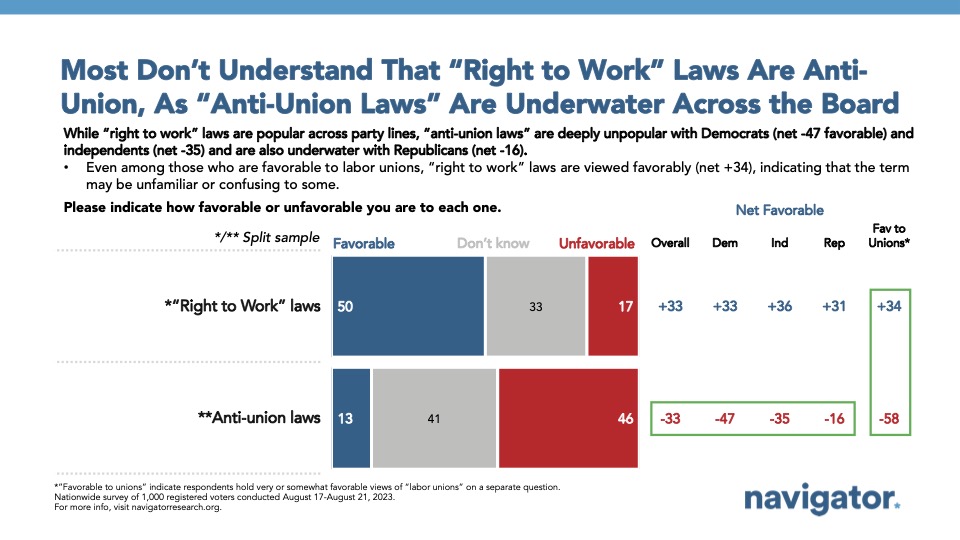

While anti-union laws are strongly unfavorable across party lines, most don’t understand that “right to work” laws are anti-union laws.

Just over one in ten say they have favorable views of “anti-union laws” (net -37; 13 percent favorable – 50 percent unfavorable), with net favorability underwater across the board amongst Democrats (net -47), independents (net -35), and Republicans (net -16). Despite anti-union laws being deeply unpopular, “right to work laws” are viewed favorably across party lines (net +33; 50 percent favorable – 17 percent unfavorable). Even among those who are favorable to labor unions, “right to work laws” were viewed favorably (net +34).

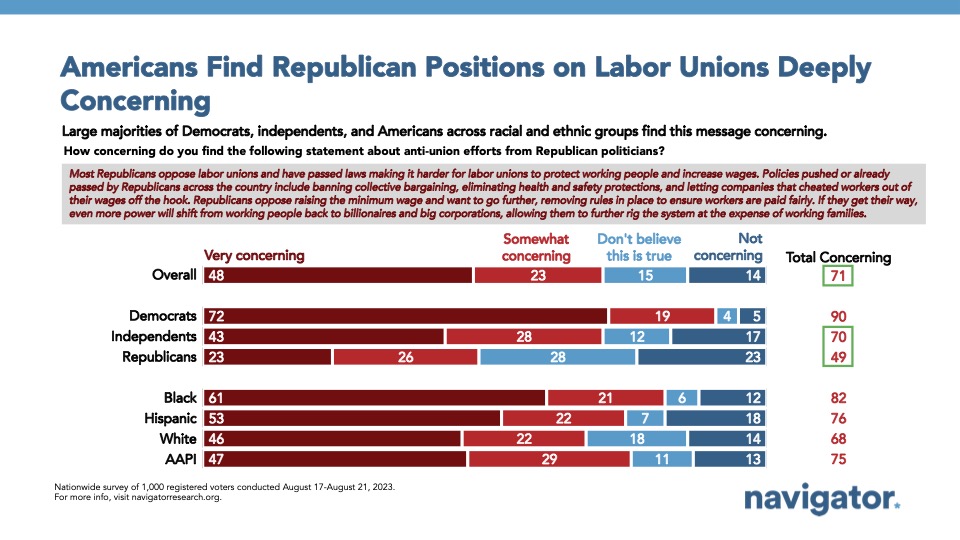

Anti-union efforts from Republican politicians are deeply concerning to Americans.

Respondents were shown the following statement about anti-union efforts from Republican politicians: “Most Republicans oppose labor unions and have passed laws making it harder for labor unions to protect working people and increase wages. Policies pushed or already passed by Republicans across the country include banning collective bargaining, eliminating health and safety protections, and letting companies that cheated workers out of their wages off the hook. Republicans oppose raising the minimum wage and want to go further, removing rules in place to ensure workers are paid fairly. If they get their way, even more power will shift from working people back to billionaires and big corporations, allowing them to further rig the system at the expense of working families.” Seven in ten found this statement to be concerning (71 percent), including nine in ten Democrats (90 percent), seven in ten independents (70 percent), and nearly half of Republicans (49 percent).

- In a separate question, the top concerns Americans have regarding anti-union policies being pursued by Republican politicians include “Republicans want to take power from working people and give it back to billionaires and big corporations, allowing them to further rig the system at the expense of working families” (41 percent) and that “Republicans oppose raising the minimum wage and want to go further, removing rules that are in place to ensure workers get paid fair wages they can make a living on” (32 percent).

Navigator Research on the Economy

Three in Five Americans Support a National Law Protecting Abortion Medication

Poll on abortion rights in the U.S., including support for creating a federal protection to access prescription abortion medication and trust in the Supreme Court as the Court prepares to hear arguments on abortion-related cases.

Three in Five Constituents Support Congress Taking Action to Federally Protect Medication Abortion and IVF

Battleground poll on the recent Alabama Supreme Court decision impacting IVF, including the most concerning outcomes from the decision and support for Congress federally protecting both medication abortion and IVF.

The Most Popular Elements of the Biden Administration’s Proposed Budget Include Lowering Health Care Costs and Taxing the Rich

Polling data on how Americans view different parts of the Biden administration’s proposed federal budget, how they view the Republican Study Committee’s proposed budget, and how learning about both budget proposals impacts perceptions.

Share this:

About the study.

Global Strategy Group conducted public opinion surveys among a sample of 1,000 registered voters from August 17-August 21, 2023. 105 additional interviews were conducted among Hispanic voters. 75 additional interviews were conducted among Asian American and Pacific Islander voters. 103 additional interviews were conducted among African American voters. 100 additional interviews were conducted among independent voters. 100 additional interviews were conducted among union households. The survey was conducted online, Nationwide surveys of registered voters; Each wave represents approximately 1,000 interviews taken over the prior three-five days. recruiting respondents from an opt-in online panel vendor. Respondents were verified against a voter file and special care was taken to ensure the demographic composition of our sample matched that of the national registered voter population across a variety of demographic variables.

Like the info here?

Get it directly in your inbox when new polls are released.

About Navigator

In a world where the news cycle is the length of a tweet, our leaders often lack the real-time public-sentiment analysis to shape the best approaches to talking about the issues that matter the most. Navigator is designed to act as a consistent, flexible, responsive tool to inform policy debates by conducting research and reliable guidance to inform allies, elected leaders, and the press. Navigator is a project led by pollsters from Global Strategy Group and GBAO along with an advisory committee, including: Andrea Purse, progressive strategist; Arkadi Gerney, The Hub Project; Joel Payne, The Hub Project; Christina Reynolds, EMILY’s List; Delvone Michael, Working Families; Felicia Wong, Roosevelt Institute; Mike Podhorzer, AFL-CIO; Jesse Ferguson, progressive strategist; Navin Nayak, Center for American Progress Action Fund; Stephanie Valencia, EquisLabs; and Melanie Newman, Planned Parenthood Action Fund.

- Competition

- Inequality & Mobility

- Tax & Macroeconomics

- Value Added

- Elevating Research

- Connect with an Expert

- In the Media

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

Connect with us

- Washington Center for Equitable Growth

- 740 15th St. NW 8th Floor

- Washington, D.C. 20005

- Phone: 202.545.6002

RESEARCH December 13, 2022

The latest research on unions demonstrates that they reduce the spread of COVID-19 for workers and the broader public

- The experience of of workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic shows that U.S. workers need labor unions because neither government regulations nor market forces are sufficient to protect workers.

- The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration has improved workplace safety since its founding in 1971, yet thousands of workers are killed and millions are maimed at work each year in the United States.

- Relying on market forces alone to help address worker safety problems is unlikely to meaningfully improve workplace safety because many U.S. workers find it difficult to quit even when facing poor working conditions.

- U.S. workers also may be deterred from moving themselves and their families to new job opportunities because of important family and community ties in their present location, which in turn can lead to local labor markets that are riddled with market failures, such as unsafe working conditions.

- This report demonstrates that labor unions in one key sector of the care economy—nursing homes—can mitigate these market failures by providing workers with a voice in the workplace and enabling them to bargain collectively with their employers.

- This report details why safe worksites are often won through union-led struggles, not automatically generated by market competition, focusing on nursing homes and the broader U.S. economy.

- The benefits of unionization may be especially large for Black workers, who are often exposed to the most dangerous workplace hazards, in nursing homes and writ large in U.S. workplaces.

- The findings in this report suggest that unionization improves health outcomes for workers and reduces racial health inequalities—dynamics consistent with broader research that links public health and racial equality to stronger economic growth.

Ros Reggans was overjoyed when she learned that her employer, a Chicago-area nursing home chain, had received more than $12 million in COVID-19 relief funds through the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. But when she learned that the nursing home was not planning on using these funds to provide staff with more personal protective equipment, higher wages, and paid sick time, she organized her co-workers to go on strike.

“Our patients were dying, our co-workers were dying, and you’re gonna tell me there’s no support for our work? That didn’t feel right to me,” Reggans said. 1 For more than a week, 700 nurses, certified nursing assistants, dietary workers, and other support staff walked picket lines, undeterred by heavy snow and an intransigent boss. Reggans, a Black certified nursing assistant, is also a union steward for the Service Employees International Union. She saw the strike as the best way to advocate for what the staff and patients needed.

Eventually, they went back to work after receiving a modest raise, better access to the needed personal protective equipment, and bonus COVID-19 pay, a sum that allowed workers at the nursing home to stop moonlighting at multiple homes for extra money. They knew that they were at high risk of bringing COVID-19 from nursing home to nursing home and infecting patients in the process, but rent and grocery bills add up quickly on low wages. “That extra money we got wasn’t just for our pockets,” Reggans explained. “It’s pretty simple—the safer we are, the safer they are.” 2

The experience of Reggans and her union illustrates broader themes about labor unions and workplace safety that are important for understanding the past and future of public health crises. Workers need labor unions because neither government regulations nor market forces are sufficient to protect workers. Although the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration has improved workplace safety since its founding in 1971, thousands of workers are killed and millions are maimed at work each year in the United States. 3

Some economists and policymakers argue that market forces alone can help address worker safety problems. Specifically, they believe that those workers who are unhappy with working conditions can simply quit, thus incentivizing employers to improve workplace safety to retain workers. Relying on market mechanisms alone, however, is unlikely to meaningfully improve workplace safety because many workers find it difficult to quit even when facing poor working conditions.

There are many reasons why this is the case. These include market frictions, such as high unemployment, employers’ monopsony power—some firms’ monopoly-like control of labor market conditons in their industries or local labor markets—fear of losing health insurance tied to employment, and incomplete information about workplace safety hazards. All of these conditions make changing jobs burdensome. 4

In addition, workers may be deterred from moving themselves and their families to new job opportunities because of important family and community ties in their present location. 5 Under such circumstances, firms no longer need to compete to retain workers, and local labor markets become riddled with market failures, such as unsafe working conditions.

Our research shows that labor unions in one key sector of the care economy—nursing homes—can mitigate these market failures by providing workers with a voice in the workplace and enabling them to bargain collectively with their employers. Viewing workplace safety as a contingent and contested outcome allows us to identify different labor market institutions, such as unions, that contribute to better and safer jobs—not just in nursing homes, but across the U.S. economy as well.

This report details why safe worksites are often won through union-led struggles, not automatically generated by market competition, focusing on nursing homes and the broader U.S. economy. As we demonstrate below, the benefits of unionization may be especially large for Black workers, who are often exposed to the most dangerous workplace hazards, in nursing homes and writ large in U.S. workplaces. Our findings suggest that unionization improves health outcomes for workers and reduces racial health inequalities. These dynamics are consistent with broader research that links public health and racial equality to stronger economic growth. 6

Unions and workplace safety

Labor unions in the United States have long helped to improve U.S. workers’ safety and guarantee safe worksites. First, unionized workforces enjoy, on average, more comprehensive health insurance coverage, which can improve the overall health of workers and allow them to see doctors more regularly without worrying as much about out-of-pocket costs. 7

Second, unionized workers tend to report workplace safety hazards more frequently to the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration because they have fewer fears of management reprisals for speaking up. Third, collective bargaining agreements frequently restrict excessive hours, mediate the pace of work, and enforce the use of personal protective equipment.

In the best-case scenario, workers can use such agreements to insert occupation-specific safety measures that can become permanent features of company policy. Research on unions in healthcare industries, for example, shows that unions improve workplace safety—and even patient outcomes—by securing safe nurse-to-patient staffing ratios, more paid sick leave, and reducing worker turnover. 8 Similarly, new research finds that the presence of a union made it more likely that OSHA investigators would conduct an inspection of an alleged violation. 9

The reverse is true, too. Research shows that policies that lead to de-unionization, such as so-called right-to-work legislation that is popular in Southern and Midwestern states, have significantly increased occupational fatalities. 10

Why unions made a difference in workplace safety amid the pandemic

The union difference was illuminated by the dangers of the pandemic workplace. COVID-19 is, among many things, an occupational disease because essential workers were disproportionately exposed and died at higher rates. During the first year of the pandemic, researchers find that 68 percent of COVID-induced fatalities among working-age adults were among low-wage workers in retail and service industry jobs. 11 A similar study finds that workers in essential industries were roughly twice as likely to die from COVID-19 than were workers in nonessential industries. 12

Through strikes, walkouts, and protests, essential workers registered their discontent with the pandemic workplace. 13 Yet those complaints rarely translated to lasting changes unless they were backed up by a union. Unions were able to mitigate some of the most hazardous working conditions. During the pandemic, unionized workers across essential industries had greater access to paid sick leave and personal protective equipment, and were tested for COVID-19 more frequently. 14

Research also shows that unionized workers may be less likely to work multiple jobs and to live in settings associated with high COVID-19 transmission. 15 When COVID-19 first hit New York City in the spring of 2020, labor unions representing hospital workers worked closely with administrators and government agencies to rapidly expand hospital capacity while minimizing risk for workers. Unions helped secure access to necessary PPE supplies and ensured that all workers and volunteers were properly trained before being reassigned to new roles in the areas of greatest need. 16

Our own research shows that unions also worked to improve workplace safety in public schools. 17 We find that the average teachers union was associated with a 33 percent relative increase in the probability of a school district adopting a mask mandate. Our study focused on Iowa during the fall of 2020 because it was one of only 12 states that left the masking decision up to school districts at that time. Iowa was also an ideal state to study because its right-to-work law generates much higher district-level variation in unionization than is seen in states with more labor-friendly legislative environments.

We find that the leaders in Iowa’s teachers’ unions advocated for mask mandates through local school boards, a strategy that filled the policy vacuum in a state without a sweeping mask mandate. The following school year, when very few governors mandated masks in schools, this same strategy was pursued by teachers’ unions throughout the country. 18

Unions reduced the spread of COVID-19

To examine the relationship between unions and COVID-19 outcomes, our recent research focused on nursing homes, the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. The number of deaths from COVID-19 among nursing home residents and staff are greatly overrepresented in the U.S. pandemic death toll, accounting for one-fifth of all COVID-19 deaths to date. Yet this industry is also a dramatic example of the power of labor to safeguard public health.

First, we studied nursing homes in New York state during the first few months of the pandemic. Even after accounting for potential confounding factors, we find that the presence of a labor union was associated with 30 percent lower COVID-19 mortality rates for nursing home residents. 19 We also discovered that unionized nursing homes were more likely to provide workers with N95 respirators.

These safer working conditions were secured by unions negotiating with employers, organizing protests, and raising public awareness about PPE shortages. 20 These findings suggest that more PPE translated to differences between life and death among unionized and nonunionized long-term care homes during the early phase of the pandemic, when PPE shortages were more widespread.

We then extended this study to the continental United States, assessing whether the benefits of unionization continued from June 2020 through March 2021, the first full year of the pandemic. We find robust evidence that unions were associated with 10.8 percent lower COVID-19 mortality rates among nursing home residents across the country, as well as 6.8 percent lower COVID-19 infection rates among nursing home staff. 21 With more than 75,000 COVID-19 deaths among residents in nonunionized nursing homes during the period of our study, the results suggest that there would have been approximately 8,000 fewer resident deaths in less than 10 months if all nursing home facilities had been unionized.

These findings also suggest that the mechanisms by which unions reduced COVID-19 mortality rates extended well beyond providing personal protective equipment, which increasingly became easier to access over the study period we examined. While data limitations did not allow us to pin down these mechanisms, a variety of other factors may play a role in driving the union effect, including offering paid sick leave, limiting the number of workers employed at multiple facilities, or encouraging vaccination against COVID-19.

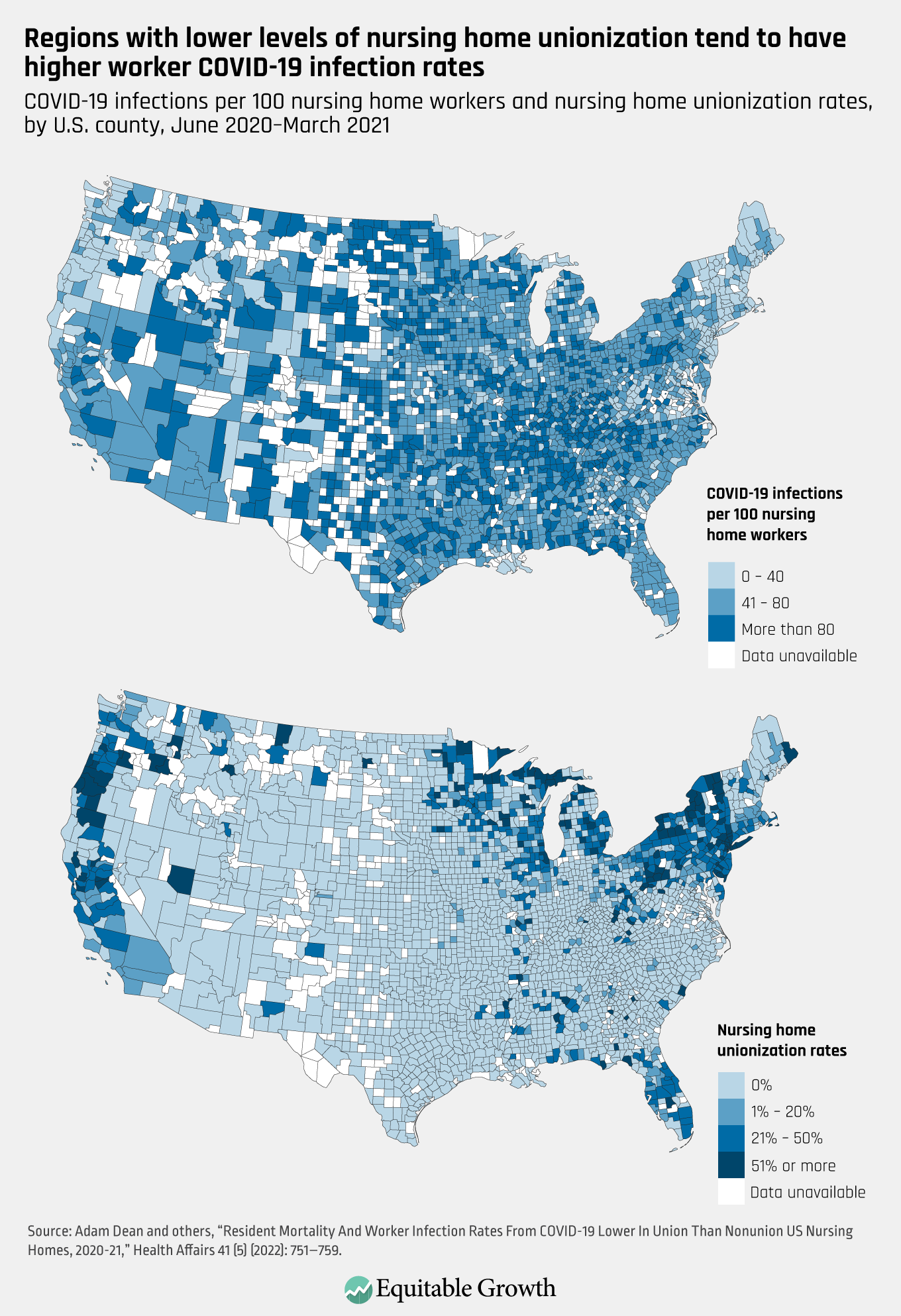

Our regression analysis focused on variation across individual nursing homes and controlled for numerous covariates, but the basic relationship between unions and lower worker COVID-19 infection rates can be seen in the county-level maps displayed in Figure 1. A comparison of these two maps reveals that regions with lower levels of nursing home unionization had higher worker COVID-19 infection rates, just as regions with higher levels of unionization had lower worker infection rates. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1 shows that the South, for example, had very few unionized nursing homes and high worker COVID-19 infection rates over that period of time. In contrast, the tristate area—made up of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut—had high unionization rates and some of the country’s lowest worker infection rates. Figure 1 also clearly shows the geographical concentration of nursing home unionization rates, with the highest union density rates in a small number of counties in the Northeast, Midwest, and Northwest of the country.

Our research suggests that labor unions improved workplace safety in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Workers in other essential industries have been coming to a similar conclusion and have been requesting union elections at a record pace. 22 The recent union victory at an Amazon.com Inc. warehouse in Staten Island, NY, for example, grew out of worker protests demanding that the company do more to reduce the workplace spread of COVID-19.

Similarly, workers at Starbucks retail stores were often motivated to unionize by similar concerns about workplace safety, winning union elections in more than 200 stores nationwide in just the past 6 months. 23 And in the gig economy, a 2022 study of ride-hail drivers during the pandemic found that workers with greater exposure to COVID-19 were more likely to express interest in joining a labor union. 24

Labor unions provide additional health premiums for Black workers

Our research findings about labor unions and COVID-19 in nursing homes have particularly important implications for racial health equity. First, the nursing home workforce is disproportionately made up of Black and Hispanic women, demographic groups that have faced higher COVID-19 infection and mortality rates throughout the pandemic, as well as greater rates of economic precarity and poor health preceding it. 25 Nursing home unions therefore help to protect some of the country’s most vulnerable workers.

Second, the health benefits of unionization may be especially large for Black workers, as discriminatory managerial practices can expose them to the most dangerous workplace tasks. 26 And third, even before the pandemic, Black workers were less likely to work in jobs with employer-sponsored health insurance, a trend that was likely exacerbated by job losses in 2020. 27 Taken together, these racial disparities help us understand how discrimination and structural racism are entwined with employment in low-wage healthcare occupations.

“Black people are put in harm’s way in nursing homes,” explains Gloria Duquette, a Black Jamaican immigrant who works in three different nursing homes in Bloomfield, CT. “The bosses are White, the supervisors are White, but most of us direct caregivers are Black. Unions have rules in place for fairness, for balance. So, it makes it harder for supervisors to play favors with White workers or discriminate against Black workers.” 28

Similar to Duquette’s explanation, scholars have identified numerous ways in which labor unions may help Black workers address workplace discrimination. First, unions educate workers about their employment rights and help them identify illegal racial discrimination. 29 Second, unions reduce workers’ fear of retaliation for voicing dissatisfaction with such discrimination. 30 Third, many unionized workplaces have formal grievance procedures that enable workers to challenge discriminatory managerial practices. 31 Moreover, research shows that unions have the effect of reducing racial resentment among their White co-workers. 32

Labor unions secure especially large wage increases for workers of color. Economists Henry Farber and Ilyana Kuziemko at Princeton Universty, Daniel Herbst at the University of Arizona, and Suresh Naidu at Columbia University analyze data from 1936 through 2019 and find that the union wage premium was larger for non-White workers than White workers. 33 Similarly, sociologists Jasmine Kerrissey and Nathan Meyers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst examine public-sector wages and find that the benefits of union membership were largest for Black and women workers. 34 Shifting focus from wages to wealth, Christian Weller at U-Mass Boston and David Madland at the Center for American Progress find that the union premium is largest for Black union households. 35

In short, there are good reasons to believe that the benefits of unionization are especially large for Black workers—which, in turn, helps reduce U.S. wage inequality and boost more equitable economic growth.

While a rich empirical literature demonstrates that the union wage premium is larger for Black workers, few studies examine how the workplace safety benefits of unionization vary across worker demographics. We therefore conducted additional analysis of COVID-19 infection rates among workers in U.S. nursing homes to see whether this union “health premium” was larger in workplaces with higher proportions of Black workers.

To do so, we gathered new data at both the county and nursing home levels. For county-level worker data by race, we use the U.S. Census Bureau’s Quarterly Workforce Indicators, which contains data on the county-level percentage of healthcare workers who are Black. For nursing-home-level worker data by race, we use recently developed estimates based on the characteristics of neighborhoods where nursing home staff reside. 36

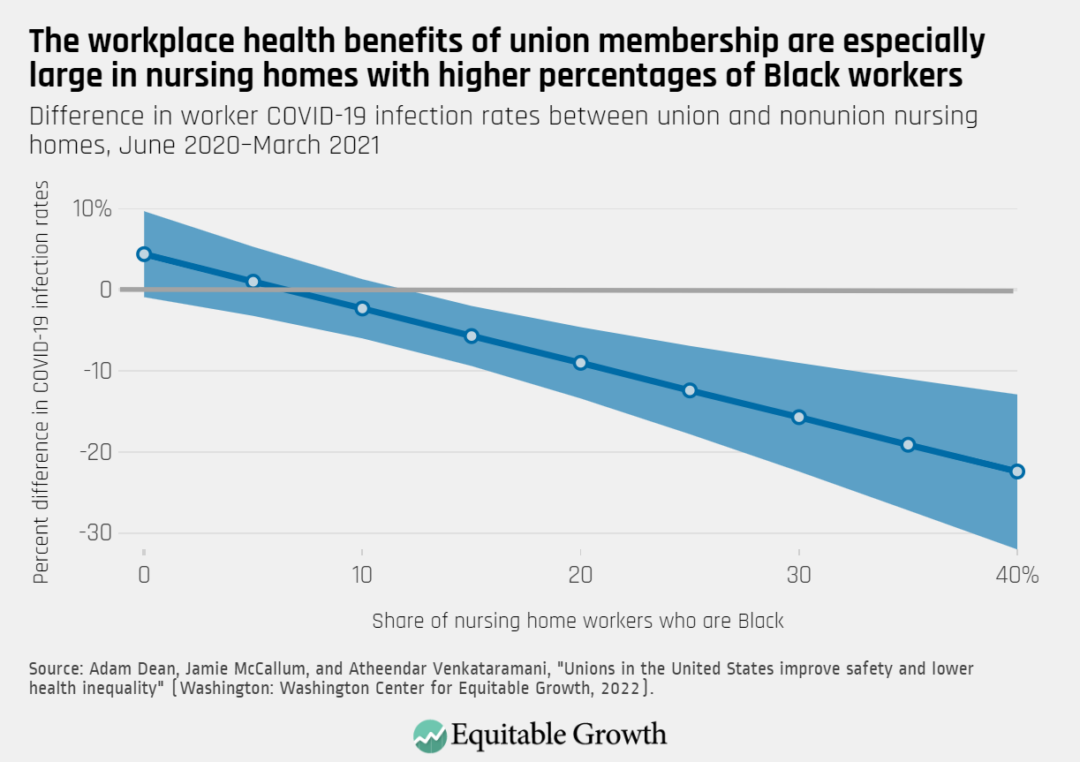

To examine whether and how the union health premium varies across workers’ racial demographics, we built on our recent Health Affairs study of more than 13,000 U.S. nursing homes by assessing heterogeneity in the association between nursing home unions and worker COVID-19 infection rates. 37 We find that the union health premium is significantly larger for nursing homes with higher percentages of Black workers. 38

More specifically, we find that when the county-level percentage of healthcare workers who are Black is at its mean (15.7 percent), unions are associated with 6 percent lower worker COVID-19 infection rates. When the county-level percentage of workers who are Black is one standard deviation above the mean (29.4 percent), unions are associated with 14.3 percent lower worker COVID-19 infection rates. 39 (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2 demonstrates that the difference in worker COVID-19 infection rates in union and nonunion nursing homes grows more negative as the percentage of Black workers increases. In other words, the workplace health benefits of union membership during the pandemic were especially large in nursing homes with higher percentages of Black workers. 40

Conclusion and policy implications

Our research suggests that public health and well-being are linked to workers organizing into unions and thus ensuring higher labor standards. This overarching finding strengthens the case for policies that would bolster the power of U.S. workers to unionize and thereby improve workplace safety. The findings that unions provide especially large health premiums for all workers, but especially Black workers, should inform policy debates about how to alleviate the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on these workers.

Most importantly, our research provides strong evidence for the need to pass the Protecting the Right to Organize, or PRO, Act, which cleared the U.S. House of Representatives in 2021 and now awaits a vote in the U.S. Senate. The legislation would update the Wagner Act, passed almost nine decades ago, and would restore workers’ right to organize without management interference by vastly reducing the obstacles that employers throw in their way.

There are a multitude of reasons to make it easier for workers to form unions. Recent research from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, for example, demonstrates that if the PRO Act were to facilitate unionization, it would increase workers’ wages and decrease income inequality. 41 Our research further bolsters the case for the PRO Act by demonstrating how unions improve workplace safety, highlighting the often-overlooked public health benefits of widespread unionization, especially for workers of color.

U.S. labor history—and the recent upsurges in union activity at corporations such as Amazon and Starbucks—shows that fair labor laws are not an absolute prerequisite for labor organizing. But the pandemic provided the context for a groundswell of interest in unions among the general public and U.S. workers themselves. 42 The PRO Act would make it easier for average workers to improve their jobs, a compelling rationale given lax workplace safety enforcement and the failure of labor markets to consistently deliver safe jobs.

While our research demonstrates the power of unions to improve health and safety, workers still need strong policy measures to ensure an adequate level of safety on the job. Less than 10 percent of all U.S. workers are union members, which means that ensuring greater workplace safety requires large-scale policymaking beyond the right to organize. Despite pressure from Congress and a lawsuit by the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration refuses to make any permanent protocols specific to occupational exposure to COVID-19 or regulations about airborne infectious diseases. Instead, it issued voluntary guidance with loopholes large enough for the biggest U.S. companies to easily slide through.

In June 2021, the agency finally issued an Emergency Temporary Standard on airborne infectious diseases. But that regulation was hobbled soon after by the U.S. Supreme Court’s subsequent rejection of the OSHA “vaccine or test” mandate at certain workplaces. 43 A permanent standard on airborne infectious diseases—akin to the 2000 bloodborne pathogen standard that improved worker safety in the wake of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and the 2014 Ebola outbreak—would create enforceable legal protections for workers in industries that face significant health risks to infectious disease such as COVID-19.

Workplace safety is a crucial component of a healthy and productive economy that generates sustainable and equitable growth. But neither labor market competition nor our current underresourced regulatory framework guarantees safe workplaces. Instead, our research stresses the need for specific policy interventions that can help workers build power from the bottom up. The right to unionize and the right to a safe workplace have been eroded. Public health and safety require that workers win them back.

About the authors

Adam Dean is an assistant professor of political science at George Washington University. His research focuses on international trade and labor politics, as well as the socioeconomic determinants of public health. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, his M.Sc. from the London School of Economics, and his B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania. His second book, Opening Up By Cracking Down , was published by Cambridge University Press in October 2020.

Jamie McCallum is an associate professor of sociology at Middlebury College. His research focuses on work and labor issues in the United States and the Global South. His third book, Essential: How the Pandemic Transformed the Long Fight for Worker Justice , was published by Basic Books in November 2022.

Atheendar Venkataramani is an assistant professor of medical ethics and health policy at the University of Pennasylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and the director of the Opportunity for Health Lab at Perelman. His research focuses on health and socioeconomic inequality—specifically, the effects of economic opportunities on health behaviors and outcomes, the effects of early life interventions on adult health and well-being, and the role of social policies and structural factors in shaping population health. Venkataramani received his Ph.D. in health policy and economics from Yale University in 2009 and his M.D. from Washington University in St. Louis in 2011.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Service Employees International Union for sharing data with us on the union status of U.S. nursing homes.

1. Jamie McCallum, Essential: How the Pandemic Transformed the Long Struggle for Worker Justice (New York: Basic Books, forthcoming.)

3. David Michaels and Jordan Barab, “The Occupational Safety and Health Administration at 50: Protecting Workers in a Changing Economy,” American Journal of Public Health 110 (5) (2020): 631–635, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7144438/ .

4. Ann Rosenthal, “Death by inequality: How workers’ lack of power harms their health and safety” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2021), available at https://www.epi.org/unequalpower/publications/death-by-inequality-how-workers-lack-of-power-harms-their-health-and-safety/ .

5. Rebecca Diamond, “The Determinants and Welfare Implications of US Workers’ Diverging Location Choices by Skill: 1980-2000,” American Economic Review 106 (3) (2016): 479–524.

6. David E. Bloom and others, “Health and economic growth: reconciling the micro and macro evidence.” Working Paper No. w26003 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019); Dora Costa and Richard H. Steckel, “Long-term trends in health, welfare, and economic growth in the United States.” In Richard H. Steckel and Roderick Floud, eds., Health and welfare during industrialization (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), pp. 47–90; Gopi Shah Goda, and Evan J. Soltas, “The Impacts of Covid-19 Illnesses on Workers.” Working Paper No. 30435 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022); Robert Lynch, “The economic benefits of equal opportunity in the United States by ending racial, ethnic, and gender disparities” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2022).

7. Thomas C. Buchmueller, John DiNardo, and Robert G. Valletta, “Union effects on health insurance provision and coverage in the United States,” ILR Review 55 (4) (2002): 610–627; Jacob Goldin, Ithai Z. Lurie, and Janet McCubbin, “Health insurance and mortality: Experimental evidence from taxpayer outreach,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 136 (1) (2021): 1–49.

8. Michael Ash and Jean Ann Seago, “The Effect of Registered Nurses’ Unions on Heart-Attack Mortality,” ILR Review 57 (3) (2004): 422–42, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/001979390405700306 ; Arindrajit Dube, Ethan Kaplan, and Owen Thompson, “Nurse Unions and Patient Outcomes,” ILR Review 69 (4) (2016): 803–33, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793916644251 ; Linda H. Aiken and others, “Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction,” JAMA 288 (16) (2002): 1987–93, available at https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/195438 ; J. Spetz, “ Nursing wage premiums in large hospitals: what explains the size-wage effect” AHSR FHSR Annu Meet Abstr 13 (1996): 100–1.

9. Aaron Sojourner and Jooyoung Yang, “Effects of Union Certification on Workplace-Safety Enforcement: Regression-Discontinuity Evidence,” ILR Review 75 (2) (2022): 373–401, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793920953089 .

10. Michael Zoorob, “Does ‘Right to Work’ Imperil the Right to Health? The Effect of Labour Unions on Workplace Fatalities,” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 75 (10) (2018): 736–738, available at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29898957/ .

11. Elizabeth B. Pathak and others, “Joint Effects of Socioeconomic Position, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender on COVID-19 Mortality among Working-Age Adults in the United States,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (9) (2022): 5479, available at https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095479 .

12. Chen, Yea-Hung and others, “COVID-19 mortality among working-age Americans in 46 states, by industry and occupation,” medRxiv (2022).

13. McCallum, Essential: How the Pandemic Transformed the Long Fight for Worker Justice .

14. Alexander Hertel-Fernandez and others, “Understanding the COVID-19 Workplace: Evidence from a Survey of Essential Workforce” (New York: Roosevelt Institute, 2020), available at https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/RI_SurveryofEssentialWorkers_IssueBrief_202006-1.pdf .

15. M. Keith Chen, Judith A. Chevalier, and Elisa F. Long, “Nursing Home Staff Networks and COVID-19,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (1) (2020), available at https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2015455118 ; Hertel-Fernandez and others, “Understanding the COVID-19 Workplace: Evidence from a Survey of Essential Workforce”; Monita Karmakar, Paula M. Lantz, and Renuka Tipirneni, “Association of Social and Demographic Factors with COVID-19 Incidence and Death Rates in the US,” JAMA Network Open 4 (1) (2021): e2036462, available at https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36462 .

16. Chris Keeley and others, “Staffing Up For The Surge: Expanding The New York City Public Hospital Workforce During The COVID-19 Pandemic,” Health Affairs 39 (8) (2020): 1426–1430.

17. Adam Dean and others, “Iowa school districts were more likely to adopt COVID-19 mask mandates where teachers were unionized,” Health Affairs 40 (8) (2021):1270–6.

18. Adam Dean and Jamie McCallum, “Strong teachers unions and school mask mandates go together,” The Monkey Cage Blog, The Washington Post , August 20, 2021, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/08/20/strong-teachers-unions-school-mask-mandates-go-together-our-research-finds/ .

19. Our regression model adjusts for county-level population and COVID-19 infections per capita. At the nursing home level, we adjust for the average age and acuity of residents, the percentage of residents whose primary support comes from Medicaid or Medicare, whether a nursing home is part of a chain or run for-profit, the percentage of residents who are White, the occupancy rate, and the staff-to-resident ratios for registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and certified nursing assistants.

20. Audrey McNamara, “Nurses across the country protest lack of protective equipment,” CBS News, March 28, 2020, available at https://www.cbsnews.com/news/health-care-workers-protest-lack-of-protective-equipment-2020-03-28/ .

21. Our regression model adjusted for the same covariates as the New York study discussed above.

22. National Labor Relations Board Office of Public Affairs, “Correction: First Three Quarters’ Union Election Petitions Up 58%, Exceeding All FY21 Petitions Filed,” Press release, July 15, 2022, available at https://www.nlrb.gov/news-outreach/news-story/correction-first-three-quarters-union-election-petitions-up-58-exceeding .

23. “Current Starbucks Statistics,” available at https://unionelections.org/data/starbucks/ (last accessed September 20, 2022).

24. Michael David Maffie, “The global ‘hot shop’: COVID‐19 as a union organising catalyst,” Industrial Relations Journal (2022), available at https://doi.org/10.1111/irj.12367 .

25. David P. Bui and others, “Racial and ethnic disparities among COVID-19 cases in workplace outbreaks by industry sector—Utah, March 6–June 5, 2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69 (33) (2020): 1133, available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6933e3.htm ; Kathryn E. W. Himmelstein and Atheendar S. Venkataramani, “Economic vulnerability among US female health care workers: potential impact of a $15-per-hour minimum wage,” American Journal of Public Health 109 (2) (2019): 198–205, available at https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304801 .

26. Elizabeth A. Deitch and others, “Subtle yet significant: The existence and impact of everyday racial discrimination in the workplace,” Human Relations 56 (11) (2003): 1299–1324, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267035611002 ; Desta Fekedulegn and others, “Prevalence of workplace discrimination and mistreatment in a national sample of older US workers: The REGARDS cohort study,” SSM-Population Health 8 (2019): 100444, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100444 .

27. Marsha Lillie-Blanton and Catherine Hoffman, “The role of health insurance coverage in reducing racial/ethnic disparities in health care,” Health Affairs 24 (2) (2005): 398–408.

28. Interview conducted by Jamie McCallum.

29. Elizabeth Hirsh and Christopher J. Lyons, “Perceiving discrimination on the job: Legal consciousness, workplace context, and the construction of race discrimination,” Law & Society Review 44 (2) (2010): 269–298, available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/40783656 .

30. Richard B. Freeman, “Individual mobility and union voice in the labor market,” The American Economic Review 66 (2) (1976): 361–368, available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/1817248 .