You may opt out or contact us anytime.

Zócalo Podcasts

What the Heck Is the Mexican Mafia?

How a gang neglected by wardens made it big outside prison walls.

Inmates walk around an exercise yard at the California Institution for Men state prison in Chino, California, June 3, 2011. The Supreme Court has ordered California to release more than 30,000 inmates over the next two years or take other steps to ease overcrowding in its prisons to prevent “needless suffering and death.” California’s 33 adult prisons were designed to hold about 80,000 inmates and now have about 145,000. The U.S. has more than 2 million people in state and local prisons. It has long had the highest incarceration rate in the world. REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson (UNITED STATES – Tags: CRIME LAW POLITICS SOCIETY) – RTR2N9TX

By Jim Hernandez | September 11, 2015

That’s the story of the Mexican Mafia.

Today, the gang is mentioned over and over in reports of crime and the prisons, but often without any context, or background. So public ignorance is broad. The Mexican Mafia is not from Mexico and it’s not like the Italian Mafia. It is, instead, a prison gang that is profoundly Californian, a reflection of our state’s history and caste system.

It’s an elemental tale that goes back beyond the Mexican Mafia’s founding in 1957 to the mid-19th century, the westward movement to California. As the value of the land increased, earlier residents (many of them Mexican) were forced to move from their homes to make way for growth and the American Dream of others.

By the 1930s, barrios had formed in communities across California. In these separated worlds, the first street gangs emerged in opposition to police and white violence. Mexican-American gangs like White Fence and Florencia controlled spaces that others could not—playgrounds, street corners, and vacant lots. And their members had each other—and the worlds where they were allowed, because no one else wanted those places. Joining a gang became an identity, a way of defying convention and law. These gangs—and their skirmishes with white gangs who attacked people—helped define the boundaries of communities like Boyle Heights and Ramona Gardens.

In the period following World War II, the world opened for those who had been excluded, at least in some places. Most significantly, the G.I. Bill made education attainable for veterans and prompted the expansion of state universities and community colleges. The foundation for this was the case Mendez v. Westminster , which challenged California’s segregated schooling.

It was these good times that, paradoxically, produced the Mexican Mafia. As opportunities opened up for some, others saw neighbors and community leaders move on and were only too aware they were left behind. Filling this leadership void were the Pintos (ex-cons) returning to their gangs, and bringing with them the culture of the prisons.

This was true of 13 gang members who were facing time at Deuel Vocational Institution, a prison in Tracy (about 60 miles southeast of San Francisco) known as the “Gladiator School.” It was a place where only the worst of California’s youth would be housed. At this time, prison jobs were doled out to the politically loyal, training was minimal, and no one much cared. So the control of the prison yards fell to the Blue-Bird and Diamond Tooth gangs, which were white. But the gangs were not particularly well organized.

That left an opening when the 13 inmates from L.A. entered Gladiator School and began recruiting Hispanic inmates from L.A. The power of this Southern California gang was challenged by others—Northern Hispanics, African-Americans, and white groups.

In response, the L.A. gang members pursued an idea; a super gang that would join together members of various L.A.-area Mexican gangs while in prison. This was not entirely new; traditionally independent gangs such as White Fence, Hawaiian Gardens, Florencia, and El Hoyo Maravilla joined forces while in prison. While these gangs may have been at odds outside prison, inside they had much in common; they had been vetted by gangs, and in prisons faced similar restrictions on their activities, including education and recreation. Their gang membership provided bonds and a support system for importing drugs, gaining information on other inmates, enforcing threats away from the prison, and coordinating violence within the prison.

From its beginning in 1957, the Mexican Mafia grew and prospered—in part because the group was ignored. After all, it represented two of the least powerful groups in California: Mexican-Americans and prisoners. This neglect allowed the group time to gain power in a corrections system designed to control and punish.

No other gang gained the strength of La Eme. Prisoners could be ordered to deliver messages. If they were intercepted, then the prisoner holding the message would accept the punishment, not the sender of the message. Savings accounts for prisoners, which were established by the California Department of Corrections, were used to launder funds.

In the 1970s, the group began its evolution from prison gang to organized crime. Released convicts returned to their homes and gangs, and they began to collect “taxes” from local drug dealers, sending part of the proceeds to the Mexican Mafia. The payment of taxes allowed dealers to sell drugs unhindered and remain alive, and gave cartels a distribution network. All this was governed from inside prison walls.

Rudy Cadena, one of the original members of the Mexican Mafia, took advantage of new federally funded community service programs. After his release from prison, he spearheaded an effort by Mexican Mafia members to enter such projects as volunteers. Then, with a record of service, they offered to participate on the boards of nonprofits and other associations responsible for the program. From these positions, it was easy to take control of the project, hire and fire staff, and loot the designated funds. In a short period of time, community service programs became a cash cow for La Eme.

One example was a Los Angeles program titled Project Get Going. Ellen Delia, the wife of project director Michael Delia, challenged the Mexican Mafia’s involvement, which led to the bleeding of program funds. Refusing to see her work tossed aside, she complained to state and local leaders. But there were no responses. In 1977, she went to the state Capitol in Sacramento with the intent of taking her case directly to the state senate. Her body was found just north of the Sacramento city limits. The senate meeting went on without interruption.

At times, the Mexican Mafia could keep the peace. In 1992, with the streets of East Los Angeles resembling a war zone, Mexican Mafia leader Peter Ojeda called a meeting of gang leaders at El Salvador Park in Santa Ana. In unequivocal language, he ordered an end to the drive-by violence. Anyone who disobeyed the orders would face the possibility of assassination. The carnage ended abruptly. The Mexican Mafia was hailed as a peacemaker in the press. And, in the process, its members had gained control of many unaffiliated gangs.

Still, the Mexican Mafia faced law enforcement scrutiny, and plenty of fines and convictions of members resulted. The FBI, in particular, had success against the Mexican Mafia. But local law enforcement groups weren’t well-organized enough to fight the power and structure of a statewide gang. Indeed, the Mexican Mafia’s breadth has been its advantage—it can think about growing statewide, while police departments, by their nature, have a narrow, local focus.

That growth has been continuous and uncompromising. Its power and reach have only increased. Even the convictions show this relentlessness. Recently, the daughter of an imprisoned leader received a 15-year sentence for her role in guiding a street gang under the orders of her father. In Ventura County, a top enforcer for the Mexican Mafia was sentenced to 27 years in prison, for his attempt to establish a “Mesa” or ruling body of gang leaders.

In all these ways, the Mexican Mafia is a historic success. And quite a story. The streets of L.A. produced a change in power inside the California prison system, which in turned unified street gangs and facilitated the mass importation of street drugs. La Eme’s method was simple. They took youth on the streets and gave them an identity and purpose. They took community programs, and devoured them. They won public support.

They took a system that disregarded them—and made it theirs.

Send A Letter To the Editors

Please tell us your thoughts. Include your name and daytime phone number, and a link to the article you’re responding to. We may edit your letter for length and clarity and publish it on our site.

(Optional) Attach an image to your letter. Jpeg, PNG or GIF accepted, 1MB maximum.

By continuing to use our website, you agree to our privacy and cookie policy . Zócalo wants to hear from you. Please take our survey !-->

Get More Zócalo

No paywall. No ads. No partisan hacks. Ideas journalism with a head and a heart.

InSight Crime

INVESTIGATION AND ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZED CRIME

Mexico Cartel-US Gang Ties Deepening as Criminal Landscape Fragments

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Español ( Spanish )

US gangs and Mexico’s organized crime groups are forging ever closer ties, according to US authorities, as the fragmenting cartels turn to the transnational criminal outsourcing model to protect their interests north of the border.

In 2012, US federal forces identified Mexican drug trafficking organizations operating in at least 22 cities and nearly all counties in California (see map below). They also found 18 street and prison gangs in the state had ties to these groups, the California Attorney General’s Office (OAG) stated in a March report ( pdf – see attached below). In Texas, all of the four gangs identified as “Tier 1” for their size and threat level, as well as many “Tier 2” gangs, maintain relationships with Mexican cartels, according to the 2014 Texas Gang Threat Assessment from the Department of Public Safety or DPS ( pdf ).

The California OAG reported gangs have now grown to take on roles as enforcers, drug sellers, arms smugglers and money launderers for the cartels. In turn, they get to buy their drugs in bulk from the major organizations, thus allowing them to bypass the middlemen and receive up to 50 percent discounts on wholesale drug purchases. Similarly, the Texas report found gangs were involved in drugs, weapons, cash and people smuggling for the cartels, as well as contract killings.

This relationship allows the Mexican organizations to conduct operations without entering US territory, thus reducing their risks, and to expand their distribution networks. US gang members offer the added benefits of being able to cross the border with less risk of detection and having an in-depth knowledge of the areas where they operate.

While Mexico’s transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) prefer to partner with gangs of their own nationality, both reports make it clear that profit comes first for both the gangs and the cartels. The Texas report states: “Ultimately, gangs work with any group that will help further their criminal objectives.”

In California, the Familia Michoacana has worked with La M and its rival gang, Nuestra Familia, but has also been documented as working with the primarily African-American gangs like the Bloods and the Crips, and the white supremacist prison gang the Aryan Brotherhood. Members of transnational street gangs the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) and Barrio 18 operating in California are also reportedly involved with the Mexican cartels, as well as partnering with California gangs, including La M, who have worked in association with the MS13 since at least the early 1990s.

Inter-gang rivalries do not stop opposing gangs from working with the same cartel. In fact, according to the Texas gang report, business relationships with Mexican cartels have led to increased cooperation across racial divides and between former rivals. The report mentions a drug ring run by the Aryan Brotherhood and the primarily Hispanic gang Houstone Tango Blast, in collaboration with a Mexican cartel. The California report, on the other hand, expresses concern over the potential violence the gang-cartel relationship may create when, for example, “Sureños” gangs (those operating in the southern part of the state) attempt to encroach on “Norteño” territory on behalf of cartels.

Both reports highlighted the potential for increased violent crime as these relationships deepen. Major cities such as San Jose, California, have already reported huge increases in gang related homicides, and throughout the state, around 30 percent of all murders between 2009 and 2012 were gang-related. Meanwhile, in some jurisdictions in Texas, gangs are reportedly responsible for up to 90 percent of all crime.

InSight Crime Analysis

Ties between Mexican cartels and US gangs are not new. Gangs operating near the southwestern border have long bought product from Mexican groups for US-based street sales. However, as these reports highlight, this relationship has been expanding geographically and evolving, particularly since 2006, the year that marked the start of former President Felipe Calderon’s frontal assault on the cartels.

These kinds of alliances are, in part, the product of a changing criminal landscape in Mexico . As the major cartels have weakened and fragmented, new, smaller groups have emerged to challenge their hegemony. In turn, this has forced the cartels to seek out both alternative revenue streams and new alliances.

Cartels have been forced to realign themselves — for example, Zetas rival the Sinaloa Cartel appears to have struck up a tenuous alliance with the Zetas’ former bosses in the Gulf Cartel. New alliances have also been reported between the old cartels and the newer criminal groups, with agents from the Beltran Leyva Organization (BLO) allegedly meeting with Knights Templar contacts this past January.

Developing collaborative relationships with gangs on the US side of the border is the logical next step in this process, and the states bordering Mexico, which are key entry points for drugs shipped north, are a good place to start. According to a 2011 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) report ( pdf ), the Sinaloa Cartel maintains business ties with gangs based in the border states of California, Arizona and Texas. California’s major cities, in particular, have become important transit points for methamphetamine and heroin (see OAG map below) — an estimated 70 percent of foreign-produced methamphetamines consumed in the US is first trafficked through San Diego. It is also a rising marijuana production center for Mexico’s cartels and a money laundering hotspot, reported the OAG.

Both reports emphasize the fluidity of these relationships and the key role that mutual business interests play. However, there is also one case in Texas that shows just how deep these ties have the potential to go: Barrio Azteca. This gang was born in the Texas prison system, but later expanded across the border into Mexico and developed a relationship with the Juarez Cartel, providing manpower for the group’s armed wing “La Linea” as the group fought the Sinaloa Cartel for control of Juarez. The gang has since grown to control local drug distribution in its own right.

SEE ALSO: Barrio Azteca Profile

While Barrio Azteca is the most extreme case, it is not the only gang that appears to show loyalty to a specific cartel. Another example is the Sureños, or Sureño 13, a gang confederation loosely affiliated to the Mexican Mafia that originated in California and whose expansion in Texas was partly facilitated by the Sinaloa Cartel, according to the DPS (see DPS map of Sureños presence in Texas below). This Mexican drug federation turned to the gang for support in El Paso after seizing control of the Juarez drug route, largely because the gang was “already a longstanding client and a trusted ally.”

These relationships will likely continue to deepen, evolve and grow as Mexican TCOs expand operations further into the US and tap into new markets. In the latest National Drug Threat Assessment report ( pdf ), the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) noted increased heroin and methamphetamine consumption in the US, thought to be driven by Mexican suppliers, and the presence of Mexican heroin in the eastern coast and Midwest markets (areas historically dominated by Colombian product). The Sinaloa Cartel, particularly, has established itself in the Chicago heroin market , which is an important transit point for drugs distributed to the rest of the United States.

It is not just Mexico’s biggest transnational organizations that are following this model and it appears even the smaller, more territorially based Mexican groups are trying to cash in on the trade and seeking out the help of US gangs. The Texas report cites a June 2013 operation in which 37 members of Tango Blast and the Mexican Knights Templar criminal group were indicted on heroin, methamphetamine and money laundering charges.

The new cooperation paradigm in Mexico follows a similar trend to that seen with the fragmentation of Colombia’s underworld: less powerful criminal organizations facing greater competition are seeking out new allies, and aligning themselves with criminals lower on the chain that can help carry out their dirty work and protect their drug interests.

After the paramilitary umbrella organization the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) officially disbanded, numerous elements from this and other drug trafficking groups formed what the Colombian government has labeled “BACRIM” (from bandas criminales – criminal bands). These third-generation drug traffickers no longer have the same reach or power over all links in the drug chain as their predecessors. Because of this, groups such as Colombia’s current premier drug trafficking organization, the Urabeños, have relied on the assistance of so-called “oficinas de cobro” — criminal debt collection offices — and other smaller groups, including street gangs. These other groups also run their own independent operations, and the alliances are far from sacred: they constantly shift and evolve based on business interests.

SEE ALSO: Coverage of BACRIM

As Mexico’s major capos get picked off and the cartels are weakened by security force initiatives and infighting, its organized crime landscape is increasingly looking like Colombia’s . The growing, fluid relationships with US-based gangs are just one sign of this and along with the diversification of cash sources and drug routes, likely represent the future of organized crime in the region.

Related Content

What are your thoughts, click here to send insight crime your comments..

We encourage readers to copy and distribute our work for non-commercial purposes, with attribution to InSight Crime in the byline and links to the original at both the top and bottom of the article. Check the Creative Commons website for more details of how to share our work, and please send us an email if you use an article.

One reply on “Mexico Cartel-US Gang Ties Deepening as Criminal Landscape Fragments”

Stay informed with insight crime.

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive a weekly digest of the latest organized crime news and stay up-to-date on major events, trends, and criminal dynamics from across the region.

We go into the field to interview, report, and investigate. We then verify, write, and edit, providing the tools to generate real impact.

Our work is costly and high risk. Please support our mission investigating organized crime.

Download the full report (PDF)

Mexico’s vigilantes: violence and displacement – a photo essay

In southern Mexico, a toxic mix of gangs, vigilantes and cartels is fuelling rising violence. ‘Community police’ or ‘self-defence’ groups, often accused of having ties with drug cartels, have proliferated and extended their control over the territory. And time after time, outnumbered soldiers do not intervene

A FUPCEG vigilante vehicle bears the slogan: “They could see me dead, but never surrendering nor humiliated”, at the group’s base in Filo de Caballos

What now passes for the law in Xaltianguis, a little town on the road to Acapulco, arrived with a car bomb and butchery. A heavily armed vigilante force took over the town in the Mexican state of Guerrero last month by driving out a rival band, blowing up a car with gas cylinders and cutting up the body of one of the fallen gang members. Residents cowered in their homes or fled down the highway through mountainous tropical scrubland. Police and troops guarding Xaltianguis did nothing.

A shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe is decorated with a Mexican flag on the road leading to Filo de Caballos. Driving the back roads of Guerrero means passing dozens of roadblocks manned by men in civilian clothes with assault rifles.

Top: clothes pegs hang on a line on the roof of a home whose residents fled after heavy fighting in Filo de Caballos. Above: displaced children rest inside an unfinished home in Chichihualco where they have taken refuge after FUPCEG vigilantes took over their towns.

Now, a few hundred metres from the new “community police” base the vigilantes set up, Mexican marines and the state police guard the highway and make patrol sorties through the town. But they have made no attempt to arrest the vigilantes, even though most of them openly carry illegal assault rifles. “We have the town practically bullet-proofed by the government. At the entrances to the town you can see the army, the marines, all levels of government here supporting us,” boasted Daniel Adame, the leader of the United Front of Guerrero Community Police (FUPCEG) group, which took over Xaltianguis.

Students pass FUPCEG vigilantes outside the group’s base in Filo de Caballos.

Left: FUPCEG vigilantes drive past the bullet hole-riddled gate to a home where heavy fighting took place in Filo de Caballos. Right: A local leader waits to meet Salvador Alanis, a FUPCEG strategist and spokesman, inside the group’s base shattered by gunfire in Filo de Caballos.

A FUPCEG vigilante on patrol in Filo de Caballos.

FUPCEG vigilantes on the streets of Xaltianguis.

It is a scene repeated over and over again in southern Mexico: “community police” or “self-defence” groups, often accused of having ties with drug cartels, have proliferated and extended their control over the territory. Critics say rival gangs often infiltrated the ranks of community police forces. And time after time, outnumbered soldiers do not intervene, in part because they are afraid of opening fire on civilians.

Many had expected violence to taper off in Guerrero as synthetic opioids such as fentanyl knocked the bottom out of the opium market that had fed organised crime groups in the state. In fact, homicides in the notoriously violent state dropped by 36% in the first three months of the year. But it appears a new round of violence is starting, pitting warring gangs against vigilante squads fighting over fuel theft, gold mines and routes for precursor chemicals.

Thousands have been displaced by the fighting, and the toxic mix of cartels, hired killers and vigilantes and state forces have essentially neutralised the Mexican military, forcing troops into the role of mere spectators or, worse, hostages.

Daniel Adame, the local FUPCEG leader, displays weapons that he says civilians have been obliged to take up to defend themselves, as his son and bodyguard stands behind him at the force’s base in Xaltianguis.

Adame is a far cry from the vigilante leaders of past years – townsfolk who armed themselves with shotguns and single-shot rifles to defend their towns from drug cartels . The FUPCEG leader is a self-described businessman who owns a lion and exotic birds, and has an expensive AR-15 rifle with a telescopic sight. His son carries a pistol with carved silver handgrips.

He defended the use of the car bomb, saying other groups – such as the rival Union of Towns and Organisations of Guerrero (UPOEG) – also used explosives. He said his group had taken over because the other one was tied to organised crime, an assertion UPOEG tossed back at Adame’s force.

A UPOEG mural at a blocked-off town entrance in Buenavista reads: “They took so much from us that we lost our fear.”

Top: UPOEG’s Comandante Geronimo talks about the force’s struggle to protect Buenavista from cartels and other vigilante groups. Above: UPOEG members solicit change from drivers at a roadblock in Buenavista.

Such groups are increasingly powerful and willing to challenge the armed forces. Salvador Alanis, a strategist and spokesman for the FUPCEG, said the group had as many as 9,000 men under arms in a string of towns it controlled, outnumbering the Mexican army in the state. He also recalled: “One time the army came and fired teargas at women, and we didn’t allow that.”

Salvador Alanis, a FUPCEG strategist and spokesman, in Filo de Caballos.

Left: FUPCEG vigilantes enter a home whose occupants fled after heavy fighting in Filo de Caballos. Right: a FUPCEG vigilante stands guard outside the group’s base in Filo de Caballos.

The Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, is betting his security strategy on the newly-created National Guard, a sort of militarised police force which is expected to be deployed in Guerrero in a month. But if the guard faces the same limitations the army does, it will immediately be at a disadvantage in states such as Guerrero and Michoacán.

Alanis said: “I’m telling the federal government right now, this could happen to your National Guard, because if one of these guys opens fire it will be a massacre on both sides.” He claimed to have an arrangement with local army commanders in Guerrero to leave his forces alone. “It’s a relationship of tolerance, if not coordination,” he added. “You don’t mess with us, and we don’t mess with you.”

Military police wear GN armbands, the insignia of the new National Guard.

While most of the vigilante forces are recruited from local men, Alanis said his group also employed about 100 gunmen trained to kill with the aim of taking over towns. He called them “a team that comes to destroy”. “They are ready to kill or die for whatever you give them,” he said.

And as it is ever more difficult to distinguish the vigilantes from the cartels, the cartels also are growing bolder. In the Michoacán town of Zamora, the Jalisco New Generation drug cartel paraded through town in May in a convoy of at least two dozen pickups and SUVs, all proudly bearing the cartel’s initials, CJNG, on their doors and sides.

With soldiers standing by as towns are taken over, the conflicts in some areas are becoming almost medieval. Residents of the town of Chichihualco have dug trenches across the highway leading to the FUPCEG stronghold in the village of Filo de Caballos because Alanis has repeatedly threatened to take over their city. Others have set up roadblocks to defend their towns. Driving the back roads of Guerrero these days means passing dozens of roadblocks manned by men in civilian clothes with assault rifles.

Top: children play on the quiet main street in Filo de Caballo. Above: A woman works in a shop in Filo de Caballos. Residents estimate that about half the town’s population fled after violent clashes and a takeover by FUPCEG vigilantes.

David Barragan, who fled FUPCEG vigilantes, gets by by manning over a government-operated tollbooth on the road leading out of Mexico City towards Guerrero, charging motorists about half the toll and keeping the money.

“Comandante Geronimo” stood by one such bullet-riddled barricade made of sandbags. A member of the UPOEG, he has endured attacks about every two months from FUPCEG to the south and the Ardillos drug gang to the north. Geronimo, who did not want to give his real name for fear of reprisals, explained why there was such heavy fighting for such small, poor towns. “There’s a crisis now in the mountains and the criminal gangs aren’t blockheads,” he said. “They say this [opium] isn’t going to be a business, but the mines are. So I think a month of crisis is coming.”

The Canadian-owned goldmines that dot the mountains have historically been shaken down for protection payments by gangs. Now gold has been discovered at other spots in the state, raising the prospect that cartels or vigilante groups may want to take up a direct role in the mines.

Others believe the groups want to take control of routes to the seaport of Acapulco to move precursor chemicals now that synthetic opioids have displaced the region’s natural-grown opium poppies. David Barragan, a resident of Los Moros who was forced from his village by the incursion of Alanis’ FUPCEG forces, said: “We thought that once the opium poppy business died out, the violence was going to end.”

Like many residents of the mountains, Barragan long depended on planting an acre or two of poppies to make money. But when prices dropped a couple of years ago, Barragan turned to his stand of avocado trees, the new “green gold” in the mountains of southern Mexico. But now the vigilantes have seized his avocado orchard and are harvesting the fruit he had waited two years to mature.

Barragan, like hundreds of his neighbours and thousands throughout the state, has fled. He said residents would not accept this situation for much longer. “The National Guard is what we most need up here, and have been waiting for, but if it doesn’t work we are going to take other measures.” He said many of his neighbours were thinking of getting guns.

A statuette of Jesus stands in an abandoned home taken over by FUPCEG vigilantes in Chichihualco.

- The Guardian picture essay

- Photography

Most viewed

Understanding and Addressing Youth in “Gangs” in Mexico

08/28/13 – The Justice in Mexico Project at the University of San Diego in collaboration with the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars presents the most recent publication in a series of working papers that analyze the range of civic engagement experiences taking place in Mexico to strengthen the rule of law and improve security in the face of organized crime related violence.

By Nathan P. Jones.

The report seeks to understand and define the gang issue in Mexico, establish the regional histories and sociologies of what is known about these gangs, and understand the causes of youth gang involvement. The paper briefly describes U.S.-Mexico bilateral efforts on youth gang prevention via the Merida Initiative, and identifies a sampling of existing civil society groups and programs geared specifically toward addressing youth gangs in Mexico and Central America. The report concludes with a set of policy recommendations for the U.S. and Mexican governments on how to best support civil society and strengthen relevant state institutions.

Nathan P. Jones, Ph.D., is the Alfred C. Glassell III Postdoctoral Fellow in Drug Policy at the Baker Institute . His research focuses on drug violence in Mexico.

Click here to read the paper.

You can also access the previous papers in this series:

Civic Engagement and the Judicial Reform: The role of civil society in reforming criminal justice in Mexico by Rodríguez Ferreira, Octavio.

The Victims’ Movement in Mexico , by Villagran, Lauren.

Civil Society, the Government and the Development of Citizen Security by Dudley, Steven and Rodríguez Sandra.

The Effects of Drug-War Related Violence on Mexico’s Press and Democracy , by Edmonds-Poli, Emily.

This Working Paper is the product of a joint project on civic engagement and public security in Mexico coordinated by the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the Justice in Mexico Project at the University of San Diego.

Related News

Analyzing the Problem of Femicide in Mexico: The Role of Special Prosecutors in Combatting Violence Against Women

¿Dónde están los datos?: New Working Paper

2019 Organized Crime and Violence in Mexico Report

New Working Paper: Immigration and National Security: An Empirical Assessment of Central American Immigration and Violent Crime in the United States

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Upcoming Events

- There are no upcoming events.

Maura Currie Maura Currie

Leave your feedback

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/mexicos-president-says-he-wont-confront-cartels-on-u-s-orders

Mexico’s president says he won’t confront cartels on U.S. orders

MEXICO CITY (AP) — Mexico’s president said Friday he won’t fight Mexican drug cartels on U.S. orders, in the clearest explanation yet of his refusal to confront the gangs.

Over the years, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has laid out various justifications for his “hugs, not bullets” policy of avoiding clashes with the cartels. In the past he has said “you cannot fight violence with violence,” and on other occasions he has argued the government has to address “the causes” of drug cartel violence, ascribing them to poverty or a lack of opportunities.

READ MORE: Mexico demands investigation into U.S. military-grade weapons being used by drug cartels

But on Friday, while discussing his refusal to go after the cartels, he made it clear he viewed it as part of what he called a “Mexico First” policy.

“We are not going to act as policemen for any foreign government,” López Obrador said at his daily news briefing. “Mexico First. Our home comes first.”

López Obrador basically argued that drugs were a U.S. problem, not a Mexican one. He offered to help limit the flow of drugs into the United States, but only, he said, on humanitarian grounds.

“Of course we are going to cooperate in fighting drugs, above all because it has become a very sensitive, very sad humanitarian issue, because a lot of young people are dying in the United States because of fentanyl,” the president said. Over 70,000 Americans die annually because of synthetic opioids like fentanyl, which are mainly made in Mexico from precursor chemicals smuggled in from China.

López Obrador’s view — like many of his policies — harkens back to the 1970s, a period when many officials believed that Mexican cartels selling drugs to gringos was a U.S. issue, not a Mexican one.

“For decades, past administrations in Mexico have thought the war against drug cartels was basically a U.S. problem,” said security analyst David Saucedo, noting that Mexican domestic drug consumption, while growing — especially methamphetamines — is still at relatively low levels.

“On the other hand, the drug cartels provide jobs in regions where the Mexican government can’t provide economic development, they encourage social mobility, and generate revenue through drug sales to balance trade and investment deficits.”

López Obrador has argued before against “demonizing” the drug cartels, and has encouraged leaders of the Catholic church to try to negotiate peace pacts between warring gangs.

Explaining why he has ordered the army not to attack cartel gunmen, López Obrador said in 2022 “we also take care of the lives of the gang members, they are human beings.”

He has also sometimes appeared not to take the violence issue seriously. In June 2023, he said of one drug gang that had abducted 14 police officers: “I’m going to tell on you to your fathers and grandfathers,” suggesting they should get a good spanking.

Asked about those comments at the time, residents of one town in the western Mexico state of Michoacan who have lived under drug cartel control for years reacted with disgust and disbelief.

“He is making fun of us,” said one restaurant owner, who asked to remain anonymous because he — like almost everyone else in town — has long been forced to pay protection money to the local cartel.

“The president said out loud what we had suspected for a long time, that his administration is not really fighting the drug cartels,” said Saucedo, the security analyst. “He has only decided to administer the conflict, setting up what may have to be a crusade against the cartels in the future that he won’t have to fight.”

López Obrador has also made a point of visiting the township of Badiraguato in Sinaloa state, the home of drug lords like Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzman, at least a half dozen times, and pledging to do so again before he leaves office in September.

It’s also a stance related to prickly nationalism and independence. Asked in November why he has visited the sparsely populated rural township so many times, López Obrador quoted a line from an old drinking song, “because I want to.”

The president has imposed strict limits on U.S. agents operating in Mexico, and limited how much contact Mexican law enforcement can have with them.

The U.S. Embassy in Mexico had no comment on López Obrador’s most recent remarks. But it did note the U.S. Treasury Department announced sanctions Friday on a Sinaloa Cartel money-laundering network in which the proceeds of fentanyl sales were used to buy shipments of cell phones in the United States, which were then sold in Mexico.

John Kirby, spokesman for the White House National Security Council, credited “strong partnership with the government of Mexico, with which we coordinated closely and for which, we are grateful,” in investigating that case.

While Mexico has detained a few high-profile gang members, the government’s policy no longer matches what Mexican drug cartels have become: extortion machines that make much of their money, not from trafficking drugs, but extorting protection payments from businessmen, farmers, shop owners and street vendors, killing anyone who doesn’t pay.

They take over legitimate businesses, kill rival street-level drug dealers, and murder bus and taxi drivers who refuse to act as lookouts for them.

The cartels control increasingly large swathes of territory both in northern Mexico — their traditional base — and in southern states like Guerrero, Michoacan, Chiapas and Veracruz.

It is unclear if peaceful coexistence was ever possible with Mexican drug gangs. While some regions have produced marijuana or opium poppies for at least 50 years, the illegal trade always brought violence.

López Obrador claims the “Mexico First” policy is needed to reduce domestic violence. Last year, he claimed Mexico saw a drop of 17% in homicides under his administration. But in fact homicides had already fallen about 7% from their mid-2018 peak when López Obrador took office in December of that year. The president is essentially taking credit for a drop that started under his predecessor, Enrique Peña Nieto.

READ MORE: Mexico almost certain to elect its first woman president as campaigning begins

The most reliable annual count shows that homicides in Mexico declined by 9.7% in 2022 compared to 2021, the first significant drop during the current administration. Mexico’s National Statistics Institute said there were 32,223 killings in 2022.

The country’s homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants dropped from about 28 in 2021 to 25 in 2022. By comparison, the U.S. homicide rate in 2021 was about 7.8 per 100,000 inhabitants.

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

Translations dictionary

or esse [ es -ey] or [ ey -sey]

What does ese mean?

Ese , amigo , hombre . Or, in English slang, dude , bro , homey . Ese is a Mexican-Spanish slang term of address for a fellow man.

Related words

Where does ese come from.

Ese originates in Mexican Spanish. Ese literally means “that” or “that one,” and likely extended to “fellow man” as shortened from expressions like ese vato , “that guy.”

There are some more elaborate (though less probable) theories behind ese . One goes that a notorious Mexican gang, the Sureños (“Southerners”), made their way from Mexico City to Southern California in the 1960s. Ese is the Spanish name for letter S , which is how the gang members referred to each other. Or so the story goes.

Ese is recorded in English for a “fellow Hispanic man” in the 1960s. It became more a general term of address by the 1980s, though ese remains closely associated (and even stereotyped) with Chicano culture in the US.

Ese is notably found in the Chicano poetry of José Antonio Burciaga and Cheech & Chong comedy routines (Cheech Marin is Mexican-American.)

White confusion over ese was memorably parodied in a 2007 episode of the TV show South Park . On it, the boys think they can get some Mexican men to write their essays , but them men write letters home to their eses .

Examples of ese

Who uses ese?

For Mexican and Mexican-American Spanish speakers, ese has the force of “dude,” “brother,” or “man,” i.e., a close and trusted friend or compatriot .

I needa kick it wit my ese's its been a minute — al (@a1anxs) February 1, 2019

It’s often used as friendly and familiar term of address…

Always a good time with my ese. 😎 pic.twitter.com/xxM4YroWDV — | Y | G | (@yg_monroe) January 12, 2019

…but it can also be more aggressively and forcefully.

Cypress Hill 2018: Who you tryin' ta mess with, ese? Don't you know I'm seeking professional help for my deep rooted emotional problemsssssss?!? — JAY. (@GoonLeDouche) June 30, 2018

“You’d have to be crazy to swipe left.” Who you tryna get crazy with, ese? Don’t you know I’m loco? Sorry, always wanted to say that. Anyway, swipe left. Might actually be crazy. — Why I Swiped Left (@LeftyMcSwiper) December 17, 2018

Ese is associated with Mexican and Chicano American culture, where it can refer to and be used by both men and women. The term is also specifically associated with Mexican-American gang culture.

What's up ese? pic.twitter.com/0vAQxZZ6SO — AlesiAkiraKitsune© (@AlesiAkira) January 21, 2019

It is often considered appropriative for people outside those cultures to use ese , especially since some non-Mexican people may use ese in ways that mock Mexicans and Mexican-American culture.

This is not meant to be a formal definition of ese like most terms we define on Dictionary.com, but is rather an informal word summary that hopefully touches upon the key aspects of the meaning and usage of ese that will help our users expand their word mastery.

- By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy policies.

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other categories

- Famous People

- Fictional Characters

- Gender & Sexuality

- Historical & Current Events

- Pop Culture

- Tech & Science

- Translations

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Mexican Slang: 90+ Spanish Slang Words and Expressions to Sound Like a Local (with Audio and a Quiz)

Looking to have a huge head start when you travel to Mexico?

You’ve gotta learn the slang.

In this post, I’m going to give you a brief introduction to the country’s unique version of Spanish—and by the time we’re done, you’ll be better prepared to navigate a slang-filled conversation with Mexicans!

The Most Common Mexican Slang Words and Expressions

1. ¡qué padre — cool, 2. me vale madre — i don’t care, 3. poca madre — really cool, 4. fresa — preppy.

- 5. ¡Aguas! — Watch out!

6. En el bote — In jail

7. estar crudo — to be hungover, 8. ¡a huevo — **** yeah, 9. chilango — someone from mexico city, 10. te crees muy muy — you think you’re something special, 11. ese — dude, 12. metiche — busybody, 13. pocho / pocha — a mexican who’s left mexico, 14. naco — tacky, 15. cholo — mexican gangster, 16. güey — dude, 17. carnal — close friend, 18. ¿neta — really.

- 19. Eso que ni que — I agree

20. Ahorita — Right now

21. ni modo — whatever, 22. no hay tos — no problem, 23. sale — okay, sure, 24. coda / codo — someone who’s cheap, 25. tener feria — to have money/change, 26. buena onda — good vibes, 27. ¿qué onda — what’s up, 28. ¡viva méxico — long live mexico.

- 29. Pendejo — Jerk

- 30. Cabrón — Mean, not very smart, awesome

- 31. Pedo — Drunk, problem

- 32. Pinche — Ugly, cheap

33. Verga — Male genitalia

34. chingar — to f***, 35. ¡no manches / ¡no mames — no way, don’t mess with me, 36. está cañón — difficult, 37. chido — nice, cool, 38. chulo / chula — good-looking person, 39. ¿a poco — really, 40. ¡órale — right on, 41. chela — beer, 42. la tira — the cops, 43. ¿mande — what, 44. suave — cool, 45. gacho — mean, 46. ándale — hurry up, 47. chale — give me a break, 48. chamba / chambear — work, 49. bronca — problem, 50. paro — favor, 51. chido / chida — cool, 52. padre — awesome, 53. chingón — badass, 54. chamba — job, 55. vato — guy, 56. morro — kid, 57. jefa / jefe — mom/dad, 58. vieja / viejo — girlfriend, wife/boyfriend, husband, 59. carnalito — little brother, 60. chiquitín — little one, 61. chavito / chavita — young guy/young girl, 62. camión — bus, 63. chulear — to show off, 64. chingar — to bother, 65. estrenar — to wear or use something for the first time, 66. guacala — yuck, 67. huevón — lazy person, 68. jato — car, 69. mamacita — attractive woman, 70. pisto — money, 71. ¿que pex — what’s up, 72. rola — song, 73. ¿sapbe — what’s up , 74. valedor — friend, 75. vato loco — crazy guy, 76. wacha — look / watch, 77. ¡ya nos cargó el payaso — we’re in trouble, 78. cuate — buddy, 79. jeta — face, 80. madrazo — a strong hit, 81. nalga — buttocks, 82. ñero — dark-skinned person, 83. pacheco — drunk, 84. pirata — fake, 85. relajo — mess, 86. riata — belt, 87. sobres — okay, got it, 88. tapado — conceited, 89. troca — truck, 90. zarape — blanket or shawl, what you need to know about mexican spanish, resources for learning more mexican slang, quick guide to mexican slang, na’atik language and culture institute, why you should learn mexican slang, mexican slang quiz: test yourself, and one more thing….

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Mexican slang could be a language of its own.

Just a word of warning: some terms on this list may be considered rude and should be used with caution.

This phrase’s literal translation, “How father!”, doesn’t make much sense at all, but it can be understood to mean “cool!” or “awesome!”

¡Conseguí entradas para Daddy Yankee! (I got tickets for Daddy Yankee!)

¡ Qué padre , güey! (Awesome, dude!)

This phrase is used to say “I don’t care.” It’s not quite a curse, but it can be considered offensive in more formal situations.

If used with the word que (that), remember you need to use the subjunctive .

Me vale madre lo que haga con su vida. (I don’t care what he does with his life).

Literally translated as “little mother,” this phrase is used to describe something really cool.

Once again, this phrase can be considered offensive (and is mostly used among groups of young men).

Esta canción está poca madre . (This song is really cool).

Literally a “strawberry,” a fresa is not something you want to be.

Somewhat similar to the word “preppy” in the United States , a fresa is a young person from a wealthy family who’s self-centered, superficial and materialistic.

Ella es una fresa. (She’s preppy/rich/stuck up).

5. ¡Aguas! — Watch out!

This phrase is used throughout Mexico to mean “be careful!” or “look out!”

Literally meaning “waters,” it’s possible that this usage evolved from housewives throwing buckets of water to clean the sidewalks in front of their homes.

¡Aguas! El piso está mojado. (Be careful! The floor’s wet).

The word bote means “can” (as in a can of soda).

However, when a Mexican says someone is “en el bote,” they mean someone is “in the slammer,” “in jail.”

Adrián no puede venir, ¡está en el bote ! (Adrian can’t come, he’s in jail!)

Estar crudo means “to be raw,” as in food that hasn’t been cooked.

However, if someone in Mexico tells you they’re crudo, it means they’re hungover because they’ve drunk too much alcohol.

Estoy muy crudo hoy. (I’m really hungover today).

Huevos (eggs) are often used to denote a specific part of the male anatomy —you can probably guess which—and they’re also used in a wide variety of slang phrases.

¡A huevo! is a vulgar way to show excitement or approval. Think “eff yeah!” without the self-censorship.

¡Ganamos el partido! (We won the game!)

¡A huevo! Me alegra. (**** yeah! I’m glad)

This slang term means something, usually a person, who comes from Mexico City.

Calling someone a chilango is saying that they’re representative of the culture of the city.

¿Eres chilango ? (Are you from Mexico City?)

This literally means “you think you’re very very” but the slang meaning is more of “you think you’re something special,” or “you think you’re all that.”

Often, this is used to power down someone who’s boastful or thinks they’re better than anyone else.

Te crees muy muy desde que conseguiste ese trabajo. (You think you’re all that since you got that job).

Supposedly, in the 1960s members of a Mexican gang called the Sureños (“Southerners”) used to call each other “ese” (after the first letter of the gang’s name).

However, in the ’80s, the word ese started to be used to refer to men in general, meaning something like “dude” or “dawg”.

It’s also possible ese originated from expressions like ese vato (“that guy”), and from that, the word ese started to be used to refer to a man.

“¿Qué pedo, ese ?” “What up, dawg?”

Metiche is a slang word for someone who loves to get the scoop on everyone’s everything.

Some people would refer to this sort of person as a busybody!

¿De qué hablaste con tu amiga? (What did you talk about with your friend?)

Nada, ¡no seas tan metiche ! (Nothing, don’t be such a busybody!)

This Mexican slang term refers to a Mexican who’s left Mexico or someone who’s perhaps forgotten their Mexican roots or heritage.

It can be used as just an observatory expression, but also as a derogatory slang word used to point out that someone’s at fault for not remembering their heritage.

Mis primos pochos vienen a visitar este fin de semana. (My pocho cousins are coming to visit this weekend).

Naco is a word used to describe someone or something poorly educated and bad-mannered.

The closest American equivalent would be “tacky” or “ghetto.”

The word has its origins in insulting indigenous and poor people, so be careful with this word!

Me parece un poco naco . (It seems a bit tacky).

Although the word cholo can have several meanings, it often refers to Mexican gangsters, especially Mexican American teens and youngsters who are in a street gang.

Vi unos cholos en la esquina. (I saw some gang members on the corner).

This one is pronounced like the English word “way” and it’s one of the most quintessential Mexican slang words.

Originally used to mean “a stupid person,” the word eventually morphed into a term of endearment similar to the English “dude.”

¡Apúrate, güey ! (Hurry up, dude!)

Carnal comes from Spanish carne (meat).

It’s perhaps for this reason that carnal is used to describe a close friend who’s like a sibling to you, carne de tu carne or flesh of your flesh.

Allí está mi carnala Laura . (There’s my close friend Laura).

“Truth?” or “really?” is what someone’s saying when they use this little word.

This popular conversational interjection is used to fill a lull in the chatter or to give someone the opportunity to come clean on an exaggeration.

Oftentimes, though, it’s just said to express agreement with the last comment in a conversation or to clarify something.

¿ Neta ? Pero ¿qué pasó? (Really? But what happened?)

19. Eso que ni que — I agree

Don’t try to translate this literally—just know that this convenient phrase means that you’re in agreement with whatever’s being discussed.

Es muy bueno para bailar. (He’s really good at dancing).

Sí, baila mejor que todos, eso que ni que . (Yes, he dances better than everyone, no doubt about it).

This translates as “little now” but the small word means right now, or at this very moment.

¡Tenemos que irnos ahorita ! (We have to leave right now!)

Ni modo , which can be literally translated as “not way” or “either way,” is possibly one of the most popular Mexican expressions.

It’s generally used to say “eh, whatever” or “it is what it is.”

Ni modo can also be used with que (that) and a present subjunctive to say you can’t do something at the moment or there’s no way you’d do it.

It’s like saying “there’s no way” or “are you nuts?” in English.

Ni modo , hay mejores chicas/chicos en el mundo. (Oh well, there are better girls/guys in the world)

Ni modo que conteste, güey. (There’s no way I’m answering, man).

No hay tos literally means “there’s no cough,” but it’s used to say “no problem” or “don’t worry about it.”

Lo siento, me olvidé mi billetera. ¿Tienes plata? (Sorry, I forgot my wallet. Do you have cash?)

No, pero no hay tos , comamos en la casa. (No, but no problem, let’s eat at home).

Sale means “okay,” “sure,” “yeah” or “let’s do it,” so it’s normally used in situations when someone suggests doing something and you agree.

It can also be used as a question tag when you want someone’s opinion or to see if they’re on the same page as you.

¿Vamos al concierto? (Shall we go to the concert?)

Sale , pero tendrás que prestarme lana. (Sure, but you’ll have to lend me some money.)

Codo literally means “elbow” in English but Mexican slang has turned it into a term used to describe someone who’s cheap.

It can be applied to either gender, so pay attention to the -a or -o ending of this descriptive noun.

¡Ese codo ni pagó la cena! (That cheapskate didn’t even pay for dinner!)

Feria means “fair” so the literal translation of this expression is “to have or be fair.”

However, feria also refers to coins when it’s used in Mexico. So, the phrase basically means “to have money” or “to have pocket change.”

¿Tienes feria ? (Do you have money?).

Buena onda literally translates to “good wave” but it’s used to indicate that there are good vibes or a good energy present.

Tienes buena onda . (You give off good vibes).

This slangy Mexican expression translates to “what wave?” but is a cool way to ask “what’s up?”

It’s another feel-good, casual conversational expression that really adds a lot of good feelings to any chat.

¿ Qué onda ? ¿Cómo has estado? (What’s up? How have you been?)

¡Viva México! literally means “long live Mexico!”

It’s the unifying phrase that says the country should grow, prosper and see happy times for its citizens and visitors.

It’s often shortened to “¡viva!” which means the same as the full phrase .

¡Ganamos el mundial! ¡ Viva México ! (We won the world cup! Long live Mexico!)

29. P endejo — Jerk

Pendejo is one of those magical words that appear in almost every Spanish variety but have a different meaning depending on where you are.

In Mexico, it has a rather rude meaning: “unpleasant or stupid person,” “jerk.”

No me hables, pendejo . (Don’t talk to me, jerk).

30. C abrón — Mean, not very smart, awesome

While technically cabrón means “big [male] goat,” it has plenty of other meanings.

Used as a rude word its meaning is quite similar to pendejo, but cabrón is higher in the rudeness scale: meaning unpleasant, mean or not very bright.

But change the tone a bit and you might, instead, be saying someone is awesome!

The word can even be used in place of the f-bomb, very often following bien— very, to mean you’re really awesome at doing something.

Soy bien cabrón jugando a Minecraft. (I’m friggin’ awesome at playing Minecraft).

31. P edo — Drunk, problem

A pedo is a fart, literally.

This word has lots of different meanings, depending on how you say it and the situation:

- Estar pedo — to be drunk

- Peda — drinking session

- Ser buen pedo — to give off good vibes

- Ser mal pedo — to be unfriendly or hostile

- ¿Qué pedo? — what’s up?

- Pedo — problem or argument

- Ponerse al pedo — to want a fight, or to have an attitude of defiance

- ¿Qué pedo contigo, cabrón? (What’s your problem, man?)

Here’s Mexican actress Salma Hayek explaining qué pedo and other Mexican slang:

32. P inche — Ugly, cheap

The word pinche may sound quite unproblematic for many Spanish speakers because it literally means “kitchen helper.”

However, when in Mexico, this word goes rogue and acquires a couple of interesting meanings.

It can mean “ugly,” “substandard,” “poor” or “cheap,” but it can also be used as an a ll-purpose enhancer, much like the meaner cousin of “hecking” is used in English.

Eres un pinche loco . (You’re effing crazy).

Originally, the verga was the horizontal beam from which a ship’s sails were hung, but this word has come to mean a man’s schlong in Spanish nowadays.

You can also use this word as a standalone exclamation with the meaning of the f-bomb.

Here are a few more uses of the word:

- Creerse verga — to think you’re all that

- Valer verga — to be worthless

- Irse a la verga — a “lovely” way of telling someone to eff off

- Tus palabras me valen verga . (Your words mean nothing to me).

Chingar means “to do the deed.” It’s Mexico’s version of the f-word. Simple.

Chingar is a word that’s prevalent in Mexican culture in its various forms and meanings.

¡Deja de chingar ! (Stop f***ing around!)

These two phrases are essentially one and the same, hence why they’re grouped together.

Literally meaning “don’t stain!” and “don’t suck,” these are used to say “no way! You’re kidding me!” or “don’t mess with me!”

No manches is totally benign, but no mames is considered vulgar and can potentially be offensive.

¡No manches! ¿Pensé que habían terminado? (No way! I thought they had broken up?)

Here are actors Eva Longoria and Michael Peña explaining no manches and other Mexican slang words:

When you say that something is está cañón (literally, “it’s cannon”), you’re saying “it’s hard/difficult.”

Some believe that the phrase arose as a more polite euphemism for está cabrón.

As a Spaniard, I find this meaning quite funny, because estar cañón means “to be very attractive” in Castilian Spanish.

El examen estuvo bien cañón . (The exam was very difficult).

This word is simply a fun way to say “nice” or “cool” in Mexican Spanish.

Despite its status as slang, it’s not vulgar or offensive in the least—so have fun with it!

It can be used as both a standalone exclamation (¡qué chido! — cool!) or as an adjective.

Tienes un carro bien chido. (You have a really cool car).

When it comes to Mexico, chulo is used as an adjective to refer to people you find hot, good-looking or pretty.

You can also use it to refer to things with the meaning of “cute,” however if you travel to Spain, don’t use this word to refer to people—since a chulo is “a pimp.”

¿Viste ese chulo en la panadería? (Did you see that hot guy in the bakery?)

There’s no way to translate this one literally, it just comes back as nonsense. Mexicans, however, use it to say “really?” when they’re feeling incredulous.

Ale dijo que ganó la lotería! (Alex said that he won the lottery!)

¿ A poco ? ¿Lo crees? (Really? Do you believe him?)

This exclamation basically means “right on!” or in some situations is used as a message of approval like “let’s do it!”

Órale is another Mexican slang word that’s considered inoffensive and is appropriate for almost any social situation.

It can be said quickly and excitedly or offered up with a long, drawn-out “o” sound.

Creo que te puedo ganar. (I think I can beat you).

¡Órale! A ver. (Bring it on! Let’s see).

Simple enough, chela is a Mexican slang word for beer.

In other parts of Latin America, chela is a woman who’s blond (usually with fair skin and blue eyes).

No one is quite sure if there’s a link between the two, and it seems unclear how the word came to mean “beer” in the first place.

¿Quieres tomar unas chelas ? (Do you want to have a few beers?)

A tira is a “strip,” but when you use it as a Mexican slang word, you mean the cops.

¡Aguas! ¡Ahí viene la tira ! (Watch out! The fuzz are coming!)

This is used in Mexico in place of ¿qué? or ¿cómo? to respond when someone says your name.

Luis, ¿estás allí? (Luis, are you there?)

¿ Mande ? ¿Me llamaste? (What? Did you call me?)

Technically, suave translates to “soft,” but suave is a way to say “cool.”

¡Ese mural es suave ! (That mural is cool!)

This literally means “slouch,” but it’s used to say something is mean or ugly .

Enrique es gacho . (Enrique is mean.)

Andar means “to walk,” so ándale is a shortened version of the verb combined with the suffix “- le ,” a sort of grammatical placeholder that adds no meaning to the word.

Use this to tell someone to hurry up .

¡ Ándale ! Necesitamos estar ahi a las 8. (Hurry up! We need to be there at 8.)

Chale doesn’t really have a clear literal translation, but it’s most often used to show your annoyance.

It’s similar to the English “give me a break.”

Su coche tardará dos semanas en arreglarse. (Your car will take two weeks to fix.)

¡Chale! (Give me a break!)

Chamba and chambear mean “work” and “to work,” respectively.

No me gusta mi chamba. (I don’t like my job.)

The word bronca means “problem,” and it’s used in expressions like no hay bronca (“no problem”) and tengo broncotas (“I’m in big trouble”).

Mi familia tiene broncas con mi hermano. (My family has problems with my brother.)

Though the official word for “favor” in Spanish is the cognate favor, paro is another way of referring to a favor in Mexico.

Hazme el paro means “do me a favor.”

Puedes hacerme el paro ? (Can you do me a favor?)

Though “cool” in Spanish is commonly expressed as genial , chido is a colloquial way of describing something as cool or awesome in Mexican slang.

Esa película estuvo bien chida . (That movie was really cool!)

Similar to chido , padre is another slang term used to convey that something is awesome or great.

¡La fiesta estuvo bien padre ! (The party was really awesome!)

Chingón is an informal term used to describe something or someone as extraordinary, impressive, or badass.

¡Ese tatuaje está bien chingón ! (That tattoo is really badass!)

Chamba is a slang term used to refer to work or a job.

Tengo mucha chamba esta semana . (I have a lot of work this week.)

Vato is a slang term for a guy or dude.

Ese vato es muy amable . (That guy is very friendly.)

Morro is an informal term for a young boy.

Mi hermanito es un buen morro . (My little brother is a good kid.)

Jefa and jefo, which both mean “boss” are just informal terms for “mom” and “dad.”

Mi jefa siempre cocina delicioso . (My mom always cooks deliciously.)

Vieja and viejo , which technically mean “old,” are similar to the English saying of “old man,” referring to a boyfriend, or “old lady,” referring to one’s girlfriend or wife.

Salí con mi vieja al cine . (I went to the movies with my girlfriend.)

Carnalito is a diminutive form of carnal , referring to a younger brother.

Mi carnalito siempre quiere jugar . (My little brother always wants to play.)

Chiquitín is an affectionate term for someone small or younger.

¡Hola, chiquitín ! ¿Cómo estás? (Hi, little one! How are you?)

These are affectionate slang terms for a young man or young woman.

Ese chavito es muy talentoso . (That young guy is very talented.)

Camión which literally means “truck,” is a colloquial term for a bus.

Voy a tomar el camión a la escuela . (I’m going to take the bus to school.)

Chulear literally means “to pimp,” but in Mexico, it’s a verb used to describe showing off or flaunting something.

Deja de chulear tu nuevo auto . (Stop showing off your new car.)

Here’s a great explanation of chulear (in Spanish):

Chingar is a versatile verb with various meanings, but it can be used to express annoyance or bother.

No me chingues , estoy ocupado . (Don’t bother me; I’m busy.)

Estrenar is a verb used when someone wears or uses something for the first time.

Voy a estrenar mis zapatos nuevos hoy .

This expression is an informal way to express disgust or dislike, similar to saying “yuck” in English.

¡ Guacala ! Esta comida no tiene buen sabor . (Yuck! This food doesn’t taste good.)

Used to describe someone who is lazy, this term is derived from the word huevo, meaning “egg,” which is associated with laziness.

Mi amigo es muy huevón , siempre está descansando . (My friend is very lazy, he’s always resting.)

While the standard term for “car” is coche , jato is a slang word used in Mexico to refer to a car or automobile.

Vamos en mi jato al cine esta noche . (Let’s go to the movies in my car tonight.)

Used as a term of endearment, mamacita refers to an attractive or beautiful woman.

¡Ay, mamacita , estás muy guapa hoy! (Oh, beautiful, you look very pretty today!)

This slang term is used to refer to money, similar to saying “cash” in English.

Necesito un poco de pisto para el transporte . (I need some cash for transportation.)

An informal and colloquial way of asking “what’s up?” or “what’s going on?”

¿ Qué pex, cómo estás? (What’s up, how are you?)

Used to refer to a song or piece of music, rola is a common slang term in Mexican Spanish.

Esta rola es mi favorita. (This song is my favorite.)

An alternative and informal way of asking “what’s up?”

Sapbe , nos vemos en el centro . (What’s up, see you downtown.)

Literally meaning “brave,” this slang term simply means “good friend.”

Mi valedor siempre está allí para ayudarme . (My friend is always there to help me.)

Describes someone as a crazy or wild guy, often used in a lighthearted or affectionate manner.

Mi amigo es un vato loco , siempre hace cosas divertidas . (My friend is a crazy guy, always doing funny things.)

Wacha , which is taken from the English “watch,” is an informal and colloquial way of saying “look” or “watch.”

Wacha esa película, está buenísima . (Look at that movie, it’s really good.)

This expression is used to convey that a difficult or troublesome situation has arisen. It literally means “the clown has already killed us.”

Se nos olvidaron las entradas, ya nos cargó el payaso . (We forgot the tickets, we’re in trouble.)

An informal term used to refer to a friend or buddy, indicating camaraderie.

Ese cuate siempre me ayuda cuando lo necesito . (That buddy always helps me when I need it.)

Used to refer to someone’s face, especially when expressing a negative emotion. It’s just like the English “mug.”

No me gusta su jeta , siempre está enojado . (I don’t like his face, he’s always angry.)

This slang term is used to describe a strong hit or punch.

Le di un madrazo al balón y entró en la portería . (I gave the ball a strong hit and it went into the goal.)

This slang term, literally “cheek,” is used informally to refer to this part of the body.

Le dieron un golpe en la nalga . (They gave him a hit on the buttocks.)

Although “dark-skinned person” is a direct translation, ñero is a colloquial term used in some regions to describe someone with a dark complexion. Be careful not to offend with this one.

No importa si eres ñero o güero, todos somos iguales . (It doesn’t matter if you’re dark-skinned or fair-skinned, we are all equal.)

Pacheco is often used in Mexico to describe someone who is intoxicated or inebriated.

No puedo hablar con él cuando está pacheco . (I can’t talk to him when he’s drunk.)

Go deeper into pacheco here:

Literally meaning “pirate,” this term is often used in Mexican slang to describe counterfeit or knockoff items.

No compres ese reloj, es pirata . (Don’t buy that watch, it’s fake.)

This literally means “relax,” but in Mexican slang, it means a mess, or a chaotic or disorderly situation.

No quiero más relajo en casa . (I don’t want more mess in the house.)

This slang term for a belt is often used in casual or regional contexts.

Me apreté la riata para que no se me cayera el pantalón . (I tightened the belt so my pants wouldn’t fall.)

Literally meaning “envelopes,” this term means “I got it,” a casual way of expressing understanding or acknowledgment.

—¿Vamos al cine mañana? —¡ Sobres ! (Are we going to the movies tomorrow? – Okay, got it!)

While “covered” is the direct translation, tapado is a slang term used in some regions to describe someone who is arrogant or full of themselves.

No me gusta hablar con él, está muy tapado . (I don’t like talking to him, he’s very conceited.)

Instead of the standard camión , troca is commonly used in Mexico to refer to a pickup truck or a large vehicle.

Vamos a cargar la troca con las cosas para la mudanza . (Let’s load the truck with the things for the move.)

Zarape specifically refers to a colorful Mexican blanket or shawl often used for warmth or decoration.

Me envolví en el zarape porque hacía frío . (I wrapped myself in the blanket because it was cold.)

Check out this video to hear some of these Mexican slang words in context:

Here’s some good things to know about Mexican Spanish:

- In Mexican Spanish, the pronoun t ú is used for the second-person familiar form. Mexicans don’t use v os .

- The pronoun vosotros isn’t used in Mexican Spanish. Mexicans use ustedes even in informal settings.

- Mexican Spanish features more loanwords from English than other national dialects. You will hear a lot more English words in Mexican Spanish than other dialects.

This is a compact volume filled with definitions, example sentences, online links and lots of relevant information about Mexican Spanish.

There are more than 500 words and phrases included in this book.

“Mexislang” is the end result of a blog that was intended to teach readers about Mexican slang.

It offers insight into the history of slang expressions and tips for how to use each word or phrase.

The option to stay with Mexican families to immerse in the language is a great way to learn about culture—including slang!

But if you’re not up for traveling, courses are also available in online one-on-one or small group format.

Online classes focus on grammar and conversational skills, so you’re sure to pick up plenty of slang along the way.

Also, they have a fantastic blog that’s both informative and entertaining.

Like with English, Spanish is spoken differently depending on the country—in fact, you could argue that Spanish differs even more than English!

In order to understand and be understood in Mexican Spanish, it’s pretty essential that you learn some common Mexican slang.

If you’re not convinced, here are some reasons you might want to learn the lingo:

- To avoid awkward situations. Don’t count on every Spanish word being transferable from place to place—something that is perfectly polite in Spanish from Spain could be considered rude in Mexican Spanish.

- If you’re learning Spanish in the United States. Considering that the States has such a huge Mexican population, chances are that you’ll encounter lots of Mexican Spanish speakers!

- For travel in Mexico. For both safety reasons and to ensure smooth travels, it’s a good idea to brush up on your slang.

- To sound more fluent. Of course, learning slang words is one of the surest ways of making your Spanish sound more natural and fluent!

Slang is perfect for instantly turning “program” Spanish into street Spanish.

More importantly, they offer insight into some cultural nuances that language learners don’t always get to see.

Use slangy terms to power up conversations and go from basic to vivid in a heartbeat!

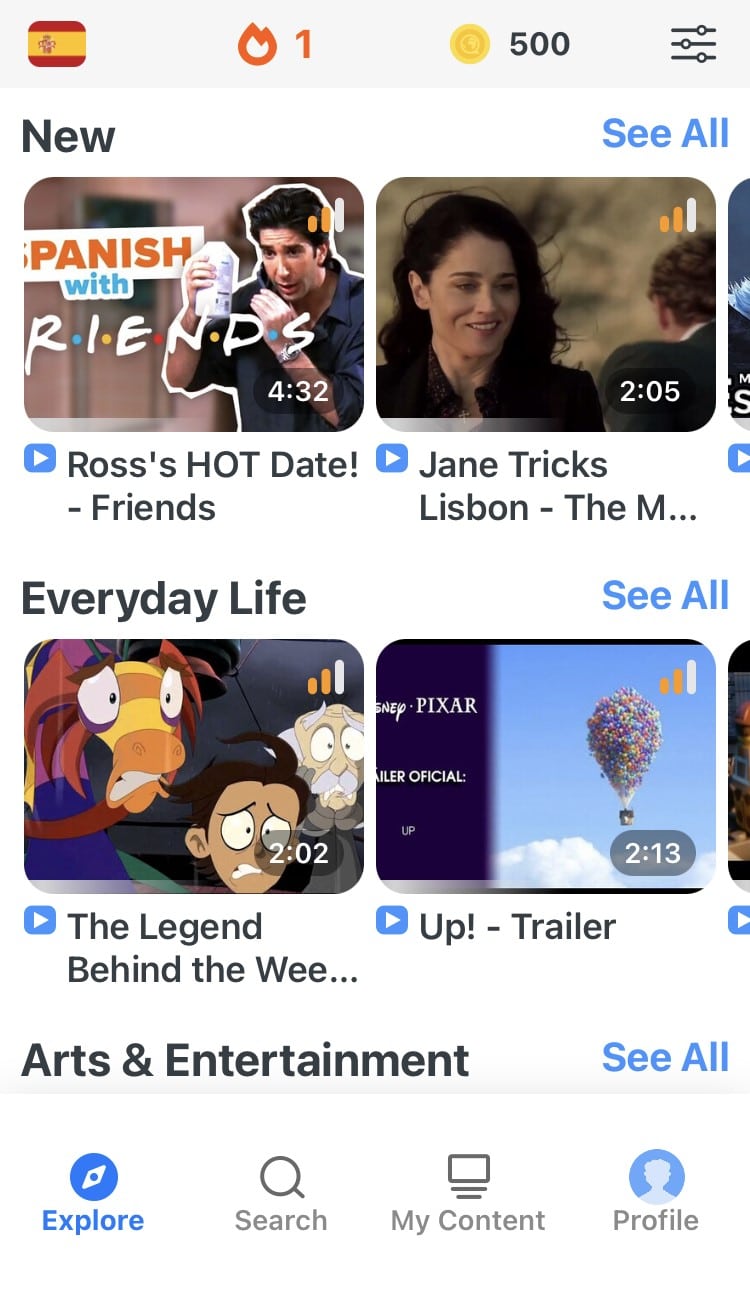

If you've made it this far that means you probably enjoy learning Spanish with engaging material and will then love FluentU .

Other sites use scripted content. FluentU uses a natural approach that helps you ease into the Spanish language and culture over time. You’ll learn Spanish as it’s actually spoken by real people.

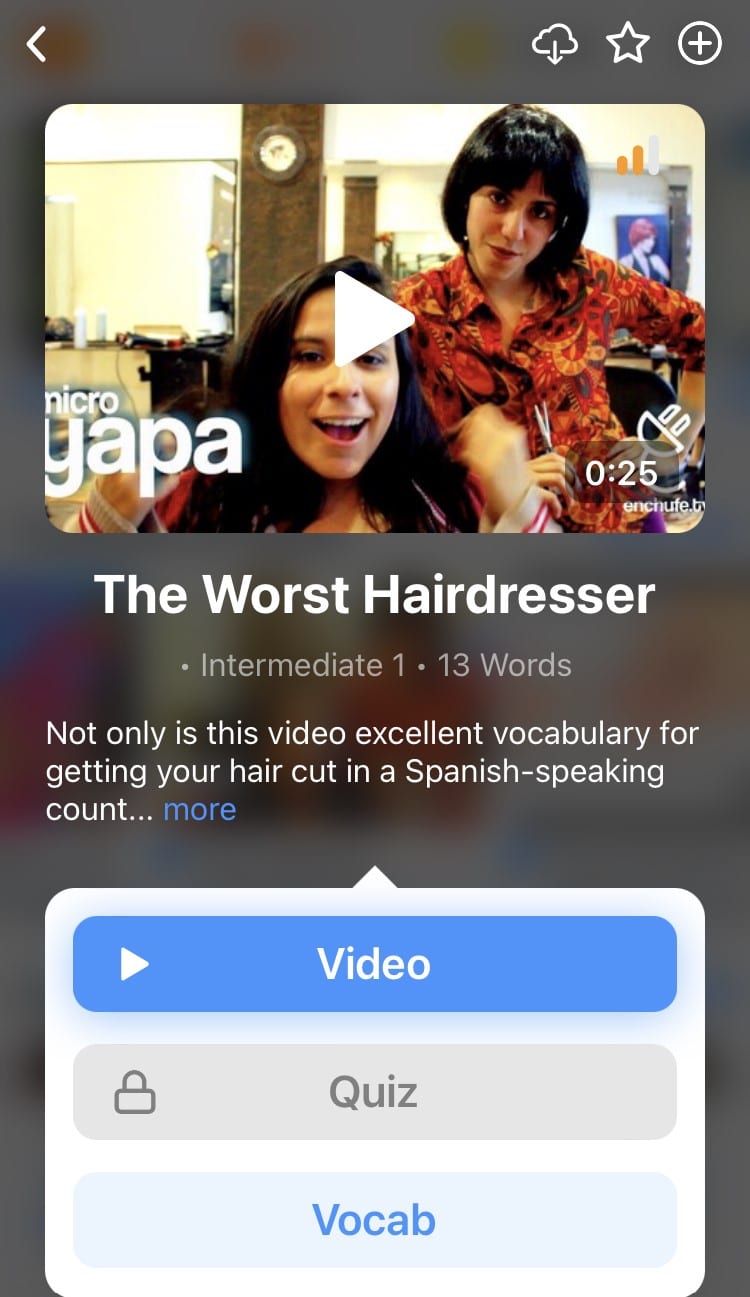

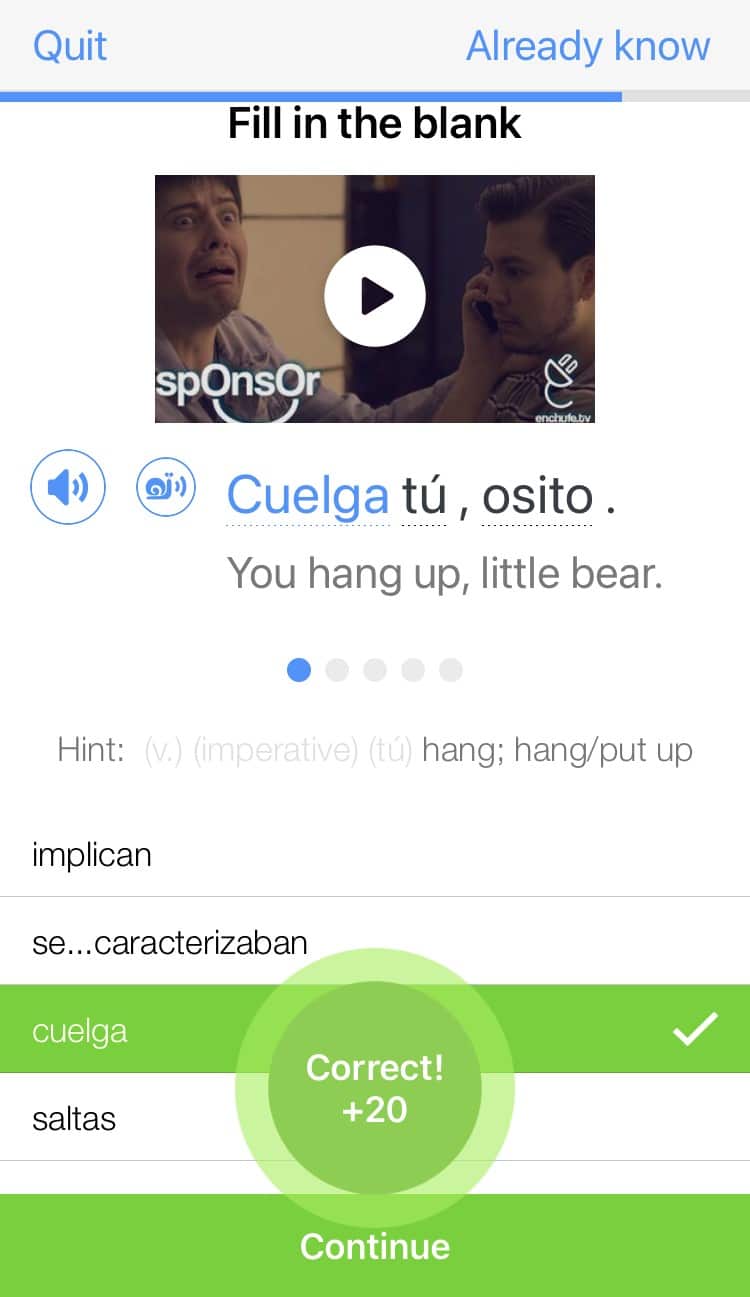

FluentU has a wide variety of videos, as you can see here:

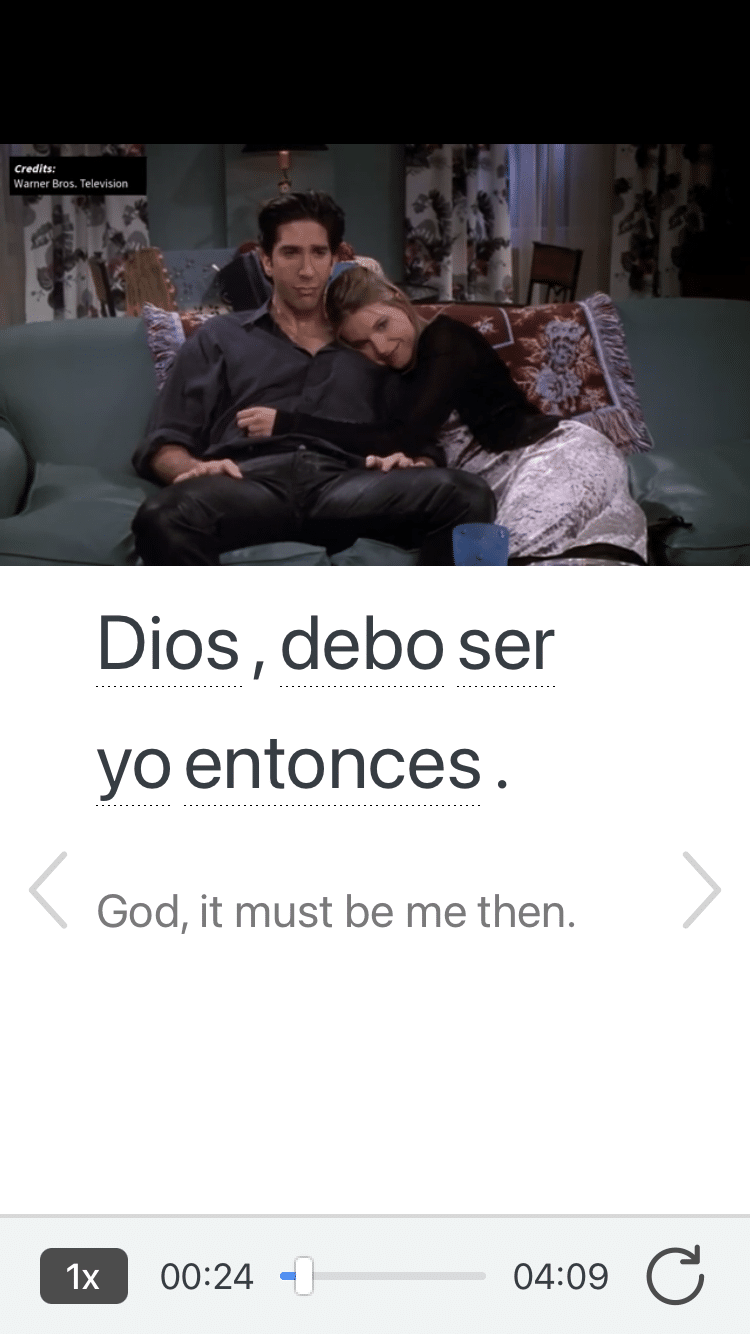

FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive transcripts. You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don’t know, you can add it to a vocab list.

Review a complete interactive transcript under the Dialogue tab, and find words and phrases listed under Vocab .

Learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU’s robust learning engine. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you’re on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you’re learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. Every learner has a truly personalized experience, even if they’re learning with the same video.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

Authorities charge Mexican Mafia prison gang members for smuggling, assault

A uthorities Friday announced that 13 members or associates of the Mexican Mafia prison gang have been charged by the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office for their roles in a narcotic smuggling operation and violent assault that took place within Los Angeles County jail system, two of whom are fugitives.

"Two of the defendants charged were arrested on Thursday and one was arrested today," Laura Eimiller of the FBI said in a statement on Friday morning.

"Two are being sought by members of the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department and the FBI's San Gabriel Valley Safe Streets Task Force," Eimiller said. "Eight defendants charged were already incarcerated on unrelated charges."

According to Eimiller, Estela Guerrero, 50, of Long Beach, and Daniel Arochi-Gonzalez, 24, of Carson, were arrested Thursday at their homes. Rosa Christina Martinez, 35, was arrested Friday in Compton. Marco Lujan, 47, and Ariel Pereyra, 28, are being sought.

The following defendants charged in the case are currently incarcerated on unrelated charges: Jose Martinez, 36, Pharoah Brooks, 47, David Fraysure, 28, Jackie Triplett, 40, Jessie Quintero, 44, Andy Dominguez, 30, Angel Grajales, 33, and Daniel Garcia, 37.

The investigation began in February of 2022, following reports that narcotics had been smuggled into the Los Angeles County Jail, as well as a report of a violent attack of an inmate within the jail, Eimiller said.

"The narcotics smuggling and violent assault are alleged to have been coordinated by several high-ranking associates of the Mexican Mafia from outside of the jail under the authority of a Mexican Mafia member in state prison," Eimiller said. "That inmate had been charged with operating inside of a Los Angeles County facility on behalf of the Mexican Mafia criminal enterprise."

According to investigators and deputy district attorneys who filed the case being announced Friday, a Mexican Mafia "facilitator" allegedly relayed orders to Mexican Mafia associates within the Los Angeles County jail -- known as "Sureños" or "soldiers" -- to attack an individual who had falsely claimed to be a member of the Mexican Mafia, which is "an act considered to be a serious violation to the criminal organization." Eimiller said.

"On orders passed through the facilitator, multiple Sureños are alleged to have attacked the victim who was transported to a hospital for treatment of his injuries," Eimiller said.

"During the investigation, a Mexican Mafia secretary and inmates -- known as "shotcallers" -- in leadership positions for the Mexican Mafia, allegedly coordinated the movement of drugs that had been smuggled into the jail, Eimiller said.

According to investigators, the narcotics were moved to different locations within the jail to be sold to other inmates for the collection of Mexican Mafia proceeds, Eimiller said.

In another incident, a Mexican Mafia shotcaller within the jail allegedly reported to a facilitator that narcotics which belonged to a Mexican Mafia member had been smuggled into the jail by an inmate, Eimiller said.

"As a result, investigators were able to identify the inmate in possession of the drugs," Eimiller said. "Deputies with the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department seized over 30 grams of heroin."

Want to get caught up on what's happening in SoCal every weekday afternoon? Click to follow The L.A. Local wherever you get podcasts.

A search warrant at the alleged facilitator's residence resulted in the seizure of about 10 ounces of methamphetamine, a firearm, numerous Mexican Mafia communications and about $16,000 in cash found in envelopes labeled with the names of several shotcallers within the jail, Eimiller said.