- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

Review discipline styles

Visualize disciplinary styles.

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- 6. Synthesize

- 7. Write a Literature Review

As you prepare to write your own review, it is a good idea to look at examples from your disciplinary area (humanities, social sciences, or natural or applied sciences). Here are some sample literature reviews taken from the introductory section of articles from different fields. The last article on the list is a systematic review article , that is, an article that does not present the results of a new study but rather discusses the results of the existing studies that have been published on its chosen topic.

At the end of each citation is a link to the full text of the article.

- Mosher, C. E., Winger, J. G., Hanna, N., Jalal, S. I., Fakiris, A. J., Einhorn, L. H., Birdas, T. J., Kesler, K. A., & Champion, V. L. (2014). Barriers to mental health service use and preferences for addressing emotional concerns among lung cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology , 23 (7), 812–819. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3488

- Gibau, G. S. (2015). Considering Student Voices: Examining the Experiences of Underrepresented Students in Intervention Programs. CBE Life Sciences Education, 14(3). http://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-06-0103

- León, D., Arzola, N., & Tovar, A. (2015). Statistical analysis of the influence of tooth geometry in the performance of a harmonic drive. Journal of the Brazilian Society of Mechanical Sciences and Engineering, 37(2), 723-735. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40430-014-0197-0

- Sawesi, S., Rashrash, M., Phalakornkule, K., Carpenter, J. S., & Jones, J. F. (2016). The Impact of Information Technology on Patient Engagement and Health Behavior Change: A Systematic Review of the Literature. JMIR Medical Informatics, 4(1), e1. http://doi.org/10.2196/medinform.4514

See below for screen captures of some aspects of each article's style . To compare these with articles by UO authors, please visit UO Scholars' Bank .

These screen captures from the articles listed above show some aspects of style from each article. Click the links in the box above to view the rest of the articles. In-text citations are highlighted because citation style is an important aspect of overall style.

- << Previous: 1. Identify the Question

- Next: 3. Search the Literature >>

- Last Updated: Jan 10, 2024 4:46 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

- Reserve a study room

- Library Account

- Undergraduate Students

- Graduate Students

- Faculty & Staff

Write a Literature Review

- Developing a Research Question

- Database Searching

- Documenting Your Search and Findings

- Discipline-Specific Literature Reviews

Are You Conducting a Literature Review in the Health Sciences?

We have a guide specific to Health Sciences Literature Reviews .

Your Librarian Can Help!

Because literature reviews can vary based on discipline, subject specialist librarians can provide online or in-person assistance with your literature review search. If ever you are in need of research assistance, don't hesitate to consult a specialist based on your subject area.

You may also find additional guidance about conducting literature reviews in your discipline by browsing our Research Guides by Subject .

Find Examples for Your Discipline

You can look for other literature reviews in your subject area to see how they are written. To see how a literature review is formatted in a particular discipline, look for peer-reviewed examples of other work in that field. You’ll find literature reviews in the introduction to a primary research article, but they can also stand alone to summarize the current state of knowledge in a field.

Additional Ebooks on Discipline-Specific Literature

VCU Libraries has various online books about conducting research that can provide you with in depth information about conducting literature reviews.

- << Previous: Documenting Your Search and Findings

- Last Updated: Oct 16, 2023 1:53 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.vcu.edu/lit-review

- General Education Courses

- School of Business

- School of Design

- School of Education

- School of Health Sciences

- School of Justice Studies

- School of Nursing

- School of Technology

- CBE Student Guide

- Online Library

- Ask a Librarian

- Learning Express Library

- Interlibrary Loan Request Form

- Library Staff

- Databases A-to-Z

- Articles by Subject

- Discovery Search

- Publication Finder

- Video Databases

- NoodleTools

- Library Guides

- Course Guides

- Writing Lab

- Rasmussen Technical Support (PSC)

- Copyright Toolkit

- Faculty Toolkit

- Suggest a Purchase

- Refer a Student Tutor

- Live Lecture/Peer Tutor Scheduler

- Faculty Interlibrary Loan Request Form

- Professional Development Databases

- Publishing Guide

- Professional Development Guides (AAOPD)

- Literature Review Guide

The Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- Plan Your Literature Review

- Identify a Research Gap

- Define Your Research Question

- Search the Literature

- Analyze Your Research Results

- Manage Research Results

- Write the Literature Review

What is a Literature Review? What is its purpose?

The purpose of a literature review is to offer a comprehensive review of scholarly literature on a specific topic along with an evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of authors' arguments . In other words, you are summarizing research available on a certain topic and then drawing conclusions about researchers' findings. To make gathering research easier, be sure to start with a narrow/specific topic and then widen your topic if necessary.

A thorough literature review provides an accurate description of current knowledge on a topic and identifies areas for future research. Are there gaps or areas that require further study and exploration? What opportunities are there for further research? What is missing from my collection of resources? Are more resources needed?

It is important to note that conclusions described in the literature you gather may contradict each other completely or in part. Recognize that knowledge creation is collective and cumulative. Current research is built upon past research findings and discoveries. Research may bring previously accepted conclusions into question. A literature review presents current knowledge on a topic and may point out various academic arguments within the discipline.

What a Literature Review is not

- A literature review is not an annotated bibliography . An annotated bibliography provides a brief summary, analysis, and reflection of resources included in the bibliography. Often it is not a systematic review of existing research on a specific subject. That said, creating an annotated bibliography throughout your research process may be helpful in managing the resources discovered through your research.

- A literature review is not a research paper . A research paper explores a topic and uses resources discovered through the research process to support a position on the topic. In other words, research papers present one side of an issue. A literature review explores all sides of the research topic and evaluates all positions and conclusions achieved through the scientific research process even though some conclusions may conflict partially or completely.

From the Online Library

SAGE Research Methods is a web-based research methods tool that covers quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods. Researchers can explore methods and concepts to help design research projects, understand a particular method or identify a new method, and write up research. Sage Research Methods focuses on methodology rather than disciplines, and is of potential use to researchers from the social sciences, health sciences and other research areas.

- Sage Research Methods Project Planner - Reviewing the Literature View the resources and videos for a step-by-step guide to performing a literature review.

The Literature Review: Step by Step

Follow this step-by-step process by using the related tabs in this Guide.

- Define your Research question

- Analyze the material you’ve found

- Manage the results of your research

- Write your Review

Getting Started

Consider the following questions as you develop your research topic, conduct your research, and begin evaluating the resources discovered in the research process:

- What is known about the subject?

- Are there any gaps in the knowledge of the subject?

- Have areas of further study been identified by other researchers that you may want to consider?

- Who are the significant research personalities in this area?

- Is there consensus about the topic?

- What aspects have generated significant debate on the topic?

- What methods or problems were identified by others studying in the field and how might they impact your research?

- What is the most productive methodology for your research based on the literature you have reviewed?

- What is the current status of research in this area?

- What sources of information or data were identified that might be useful to you?

- How detailed? Will it be a review of ALL relevant material or will the scope be limited to more recent material, e.g., the last five years.

- Are you focusing on methodological approaches; on theoretical issues; on qualitative or quantitative research?

What is Academic Literature?

What is the difference between popular and scholarly literature?

To better understand the differences between popular and scholarly articles, comparing characteristics and purpose of the publications where these articles appear is helpful.

Popular Article (Magazine)

- Articles are shorter and are written for the general public

- General interest topics or current events are covered

- Language is simple and easy to understand

- Source material is not cited

- Articles often include glossy photographs, graphics, or visuals

- Articles are written by the publication's staff of journalists

- Articles are edited and information is fact checked

Examples of magazines that contain popular articles:

Scholarly Article (Academic Journal)

- Articles are written by scholars and researchers for academics, professionals, and experts in the field

- Articles are longer and report original research findings

- Topics are narrower in focus and provide in-depth analysis

- Technical or scholarly language is used

- Source material is cited

- Charts and graphs illustrating research findings are included

- Many are "peer reviewed" meaning that panels of experts review articles submitted for publication to ensure that proper research methods were used and research findings are contributing something new to the field before selecting for publication.

Examples of academic journals that contain scholarly articles:

Define your research question

Selecting a research topic can be overwhelming. Consider following these steps:

1. Brainstorm research topic ideas

- Free write: Set a timer for five minutes and write down as many ideas as you can in the allotted time

- Mind-Map to explore how ideas are related

2. Prioritize topics based on personal interest and curiosity

3. Pre-research

- Explore encyclopedias and reference books for background information on the topic

- Perform a quick database or Google search on the topic to explore current issues.

4. Focus the topic by evaluating how much information is available on the topic

- Too much information? Consider narrowing the topic by focusing on a specific issue

- Too little information? Consider broadening the topic

5. Determine your purpose by considering whether your research is attempting to:

- further the research on this topic

- fill a gap in the research

- support existing knowledge with new evidence

- take a new approach or direction

- question or challenge existing knowledge

6. Finalize your research question

NOTE: Be aware that your initial research question may change as you conduct research on your topic.

Searching the Literature

Research on your topic should be conducted in the academic literature. The Rasmussen University Online Library contains subject-focused databases that contain the leading academic journals in your programmatic area.

Consult the Using the Online Library video tutorials for information about how to effectively search library databases.

Watch the video below for tips on how to create a search statement that will provide relevant results

Need help starting your research? Make a research appointment with a Rasmussen Librarian .

TIP: Document as you research. Begin building your references list using the citation managers in one of these resources:

- APA Academic Writer

Recommended programmatic databases include:

Data Science

Coverage includes computer engineering, computer theory & systems, research and development, and the social and professional implications of new technologies. Articles come from more than 1,900 academic journals, trade magazines, and professional publications.

Provides access to full-text peer-reviewed journals, transactions, magazines, conference proceedings, and published standards in the areas of electrical engineering, computer science, and electronics. It also provides access to the IEEE Standards Dictionary Online. Full-text available.

Computing, telecommunications, art, science and design databases from ProQuest.

Healthcare Management

Articles from scholarly business journals back as far as 1886 with content from all disciplines of business, including marketing, management, accounting, management information systems, production and operations management, finance, and economics. Contains 55 videos from the Harvard Faculty Seminar Series, on topics such as leadership, sustaining competitive advantage, and globalization. To access the videos, click "More" in the blue bar at the top. Select "Images/ Business Videos." Uncheck "Image Quick View Collection" to indicate you only wish to search for videos. Enter search terms.

Provides a truly comprehensive business research collection. The collection consists of the following databases and more: ABI/INFORM Complete, ProQuest Entrepreneurship, ProQuest Accounting & Tax, International Bibliography of Social Sciences (IBSS), ProQuest Asian Business and Reference, and Banking Information Source.

The definitive research tool for all areas of nursing and allied health literature. Geared towards the needs of nurses and medical professionals. Covers more than 750 journals from 1937 to present.

HPRC provides information on the creation, implementation and study of health care policy and the health care system. Topics covered include health care administration, economics, planning, law, quality control, ethics, and more.

PolicyMap is an online mapping site that provides data on demographics, real estate, health, jobs, and other areas across the U.S. Access and visualize data from Census and third-party records.

Human Resources

Articles from all subject areas gathered from more than 11,000 magazines, journals, books and reports. Subjects include astronomy, multicultural studies, humanities, geography, history, law, pharmaceutical sciences, women's studies, and more. Coverage from 1887 to present. Start your research here.

Cochrane gathers and summarizes the best evidence from research to help you make informed choices about treatments. Whether a doctor or nurse, patient, researcher or student, Cochrane evidence provides a tool to enhance your healthcare knowledge and decision making on topics ranging from allergies, blood disorders, and cancer, to mental health, pregnancy, urology, and wounds.

Health sciences, biology, science, and pharmaceutical information from ProQuest. Includes articles from scholarly, peer-reviewed journals, practical and professional development content from professional journals, and general interest articles from magazines and newspapers.

Joanna Briggs Institute Academic Collection contains evidence-based information from across the globe, including evidence summaries, systematic reviews, best practice guidelines, and more. Subjects include medical, nursing, and healthcare specialties.

Comprehensive source of full-text articles from more than 1,450 scholarly medical journals.

Articles from more than 35 nursing journals in full text, searchable as far back as 1995.

Analyzing Your Research Results

You have completed your research and discovered many, many academic articles on your topic. The next step involves evaluating and organizing the literature found in the research process.

As you review, keep in mind that there are three types of research studies:

- Quantitative

- Qualitative

- Mixed Methods

Consider these questions as you review the articles you have gathered through the research process:

1. Does the study relate to your topic?

2. Were sound research methods used in conducting the study?

3. Does the research design fit the research question? What variables were chosen? Was the sample size adequate?

4. What conclusions were drawn? Do the authors point out areas for further research?

Reading Academic Literature

Academic journals publish the results of research studies performed by experts in an academic discipline. Articles selected for publication go through a rigorous peer-review process. This process includes a thorough evaluation of the research submitted for publication by journal editors and other experts or peers in the field. Editors select articles based on specific criteria including the research methods used, whether the research contributes new findings to the field of study, and how the research fits within the scope of the academic journal. Articles selected often go through a revision process prior to publication.

Most academic journal articles include the following sections:

- Abstract (An executive summary of the study)

- Introduction (Definition of the research question to be studied)

- Literature Review (A summary of past research noting where gaps exist)

- Methods (The research design including variables, sample size, measurements)

- Data (Information gathered through the study often displayed in tables and charts)

- Results (Conclusions reached at the end of the study)

- Conclusion (Discussion of whether the study proved the thesis; may suggest opportunities for further research)

- Bibliography (A list of works cited in the journal article)

TIP: To begin selecting articles for your research, read the highlighted sections to determine whether the academic journal article includes information relevant to your research topic.

Step 1: Skim the article

When sorting through multiple articles discovered in the research process, skimming through these sections of the article will help you determine whether the article will be useful in your research.

1. Article title and subject headings assigned to the article

2. Abstract

3. Introduction

4. Conclusion

If the article fits your information need, go back and read the article thoroughly.

TIP: Create a folder on your computer to save copies of articles you plan to use in your thesis or research project. Use NoodleTools or APA Academic Writer to save APA references.

Step 2: Determine Your Purpose

Think about how you will evaluate the academic articles you find and how you will determine whether to include them in your research project. Ask yourself the following questions to focus your search in the academic literature:

- Are you looking for an overview of a topic? an explanation of a specific concept, idea, or position?

- Are you exploring gaps in the research to identify a new area for academic study?

- Are you looking for research that supports or disagrees with your thesis or research question?

- Are you looking for examples of a research design and/or research methods you are considering for your own research project?

Step 3: Read Critically

Before reading the article, ask yourself the following:

- What is my research question? What position am I trying to support?

- What do I already know about this topic? What do I need to learn?

- How will I evaluate the article? Author's reputation? Research design? Treatment of topic?

- What are my biases about the topic?

As you read the article make note of the following:

- Who is the intended audience for this article?

- What is the author's purpose in writing this article?

- What is the main point?

- How was the main point proven or supported?

- Were scientific methods used in conducting the research?

- Do you agree or disagree with the author? Why?

- How does this article compare or connect with other articles on the topic?

- Does the author recommend areas for further study?

- How does this article help to answer your research question?

Managing your Research

Tip: Create APA references for resources as you discover them in the research process

Use APA Academic Writer or NoodleTools to generate citations and manage your resources. Find information on how to use these resources in the Citation Tools Guide .

Writing the Literature Review

Once research has been completed, it is time to structure the literature review and begin summarizing and synthesizing information. The following steps may help with this process:

- Chronological

- By research method used

- Explore contradictory or conflicting conclusions

- Read each study critically

- Critique methodology, processes, and conclusions

- Consider how the study relates to your topic

- Description of public health nursing nutrition assessment and interventions for home‐visited women. This article provides a nice review of the literature in the article introduction. You can see how the authors have used the existing literature to make a case for their research questions. more... less... Horning, M. L., Olsen, J. M., Lell, S., Thorson, D. R., & Monsen, K. A. (2018). Description of public health nursing nutrition assessment and interventions for home‐visited women. Public Health Nursing, 35(4), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12410

- Improving Diabetes Self-Efficacy in the Hispanic Population Through Self-Management Education Doctoral papers are a good place to see how literature reviews can be done. You can learn where they searched, what search terms they used, and how they decided which articles were included. Notice how the literature review is organized around the three main themes that came out of the literature search. more... less... Robles, A. N. (2023). Improving diabetes self-efficacy in the hispanic population through self-management education (Order No. 30635901). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: The Sciences and Engineering Collection. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/improving-diabetes-self-efficacy-hispanic/docview/2853708553/se-2

- Exploring mediating effects between nursing leadership and patient safety from a person-centred perspective: A literature review Reading articles that publish the results of a systematic literature review is a great way to see in detail how a literature review is conducted. These articles provide an article matrix, which provides you an example of how you can document information about the articles you find in your own search. To see more examples, include "literature review" or "systematic review" as a search term. more... less... Wang, M., & Dewing, J. (2021). Exploring mediating effects between nursing leadership and patient safety from a person‐centred perspective: A literature review. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(5), 878–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13226

Database Search Tips

- Boolean Operators

- Keywords vs. Subjects

- Creating a Search String

- Library databases are collections of resources that are searchable, including full-text articles, books, and encyclopedias.

- Searching library databases is different than searching Google. Best results are achieved when using Keywords linked with Boolean Operators .

- Applying Limiters such as full-text, publication date, resource type, language, geographic location, and subject help to refine search results.

- Utilizing Phrases or Fields , in addition to an awareness of Stop Words , can focus your search and retrieve more useful results.

- Have questions? Ask a Librarian

Boolean Operators connect keywords or concepts logically to retrieve relevant articles, books, and other resources. There are three Boolean Operators:

Using AND

- Narrows search results

- Connects two or more keywords/concepts

- All keywords/concepts connected with "and" must be in an article or resource to appear in the search results list

Venn diagram of the AND connector

Example: The result list will include resources that include both keywords -- "distracted driving" and "texting" -- in the same article or resource, represented in the shaded area where the circles intersect (area shaded in purple).

- Broadens search results ("OR means more!")

- Connects two or more synonyms or related keywords/concepts

- Resources appearing in the results list will include any of the terms connected with the OR connector

Venn diagram of the OR connector

Example: The result list will include resources that include the keyword "texting" OR the keyword "cell phone" (entire area shaded in blue); either is acceptable.

- Excludes keywords or concepts from the search

- Narrows results by removing resources that contain the keyword or term connected with the NOT connector

- Use sparingly

Venn diagram of the NOT connector

Example: The result list will include all resources that include the term "car" (green area) but will exclude any resource that includes the term "motorcycle" (purple area) even though the term car may be present in the resource.

A library database searches for keywords throughout the entire resource record including the full-text of the resource, subject headings, tags, bibliographic information, etc.

- Natural language words or short phrases that describe a concept or idea

- Can retrieve too few or irrelevant results due to full-text searching (What words would an author use to write about this topic?)

- Provide flexibility in a search

- Must consider synonyms or related terms to improve search results

- TIP: Build a Keyword List

Example: The keyword list above was developed to find resources that discuss how texting while driving results in accidents. Notice that there are synonyms (texting and "text messaging"), related terms ("cell phones" and texting), and spelling variations ("cell phone" and cellphone). Using keywords when searching full text requires consideration of various words that express an idea or concept.

- Subject Headings

- Predetermined "controlled vocabulary" database editors apply to resources to describe topical coverage of content

- Can retrieve more precise search results because every article assigned that subject heading will be retrieved.

- Provide less flexibility in a search

- Can be combined with a keyword search to focus search results.

- TIP: Consult database subject heading list or subject headings assigned to relevant resources

Example 1: In EBSCO's Academic Search Complete, clicking on the "Subject Terms" tab provides access to the entire subject heading list used in the database. It also allows a search for specific subject terms.

Example 2: A subject term can be incorporated into a keyword search by clicking on the down arrow next to "Select a Field" and selecting "Subject Terms" from the dropdown list. Also, notice how subject headings are listed below the resource title, providing another strategy for discovering subject headings used in the database.

When a search term is more than one word, enclose the phrase in quotation marks to retrieve more precise and accurate results. Using quotation marks around a term will search it as a "chunk," searching for those particular words together in that order within the text of a resource.

"cell phone"

"distracted driving"

"car accident"

TIP: In some databases, neglecting to enclose phrases in quotation marks will insert the AND Boolean connector between each word resulting in unintended search results.

Truncation provides an option to search for a root of a keyword in order to retrieve resources that include variations of that word. This feature can be used to broaden search results, although some results may not be relevant. To truncate a keyword, type an asterisk (*) following the root of the word.

For example:

Library databases provide a variety of tools to limit and refine search results. Limiters provide the ability to limit search results to resources having specified characteristics including:

- Resource type

- Publication date

- Geographic location

In both the EBSCO and ProQuest databases, the limiting tools are located in the left panel of the results page.

EBSCO ProQuest

The short video below provides a demonstration of how to use limiters to refine a list of search results.

Each resource in a library database is stored in a record. In addition to the full-text of the resources, searchable Fields are attached that typically include:

- Journal title

- Date of Publication

Incorporating Fields into your search can assist in focusing and refining search results by limiting the results to those resources that include specific information in a particular field.

In both EBSCO and ProQuest databases, selecting the Advanced Search option will allow Fields to be included in a search.

For example, in the Advanced Search option in EBSCO's Academic Search Complete database, clicking on the down arrow next to "Select a Field" provides a list of fields that can be searched within that database. Select the field and enter the information in the text box to the left to use this feature.

Stop words are short, commonly used words--articles, prepositions, and pronouns-- that are automatically dropped from a search. Typical stop words include:

In library databases, a stop word will not be searched even if it is included in a phrase enclosed in quotation marks. In some instances, a word will be substituted for the stop word to allow for the other words in the phrase to be searched in proximity to one another within the text of the resource.

For example, if you searched company of America, your result list will include these variatons:

- company in America

- company of America

- company for America

Creating an Search String

This short video demonstrates how to create a search string -- keywords connected with Boolean operators -- to use in a library database search to retrieve relevant resources for any research assignment.

- Database Search Menu Template Use this search menu template to plan a database search.

- Last Updated: Feb 16, 2024 10:01 AM

- URL: https://guides.rasmussen.edu/LitReview

Literature review: your definitive guide

Joanna Wilkinson

This is our ultimate guide on how to write a narrative literature review. It forms part of our Research Smarter series .

How do you write a narrative literature review?

Researchers worldwide are increasingly reliant on literature reviews. That’s because review articles provide you with a broad picture of the field, and help to synthesize published research that’s expanding at a rapid pace .

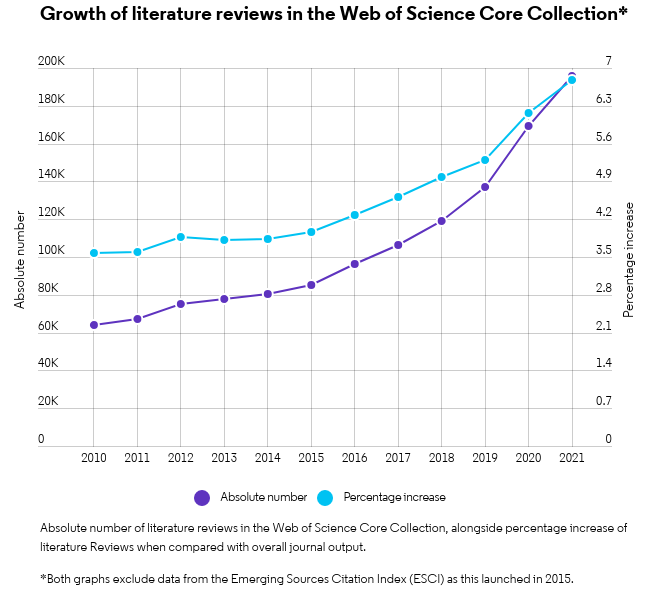

In some academic fields, researchers publish more literature reviews than original research papers. The graph below shows the substantial growth of narrative literature reviews in the Web of Science™, alongside the percentage increase of reviews when compared to all document types.

It’s critical that researchers across all career levels understand how to produce an objective, critical summary of published research. This is no easy feat, but a necessary one. Professionally constructed literature reviews – whether written by a student in class or an experienced researcher for publication – should aim to add to the literature rather than detract from it.

To help you write a narrative literature review, we’ve put together some top tips in this blog post.

Best practice tips to write a narrative literature review:

- Don’t miss a paper: tips for a thorough topic search

- Identify key papers (and know how to use them)

- Tips for working with co-authors

- Find the right journal for your literature review using actual data

- Discover literature review examples and templates

We’ll also provide an overview of all the products helpful for your next narrative review, including the Web of Science, EndNote™ and Journal Citation Reports™.

1. Don’t miss a paper: tips for a thorough topic search

Once you’ve settled on your research question, coming up with a good set of keywords to find papers on your topic can be daunting. This isn’t surprising. Put simply, if you fail to include a relevant paper when you write a narrative literature review, the omission will probably get picked up by your professor or peer reviewers. The end result will likely be a low mark or an unpublished manuscript, neither of which will do justice to your many months of hard work.

Research databases and search engines are an integral part of any literature search. It’s important you utilize as many options available through your library as possible. This will help you search an entire discipline (as well as across disciplines) for a thorough narrative review.

We provide a short summary of the various databases and search engines in an earlier Research Smarter blog . These include the Web of Science , Science.gov and the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ).

Like what you see? Share it with others on Twitter:

[bctt tweet=”Writing a #LiteratureReview? Check out the latest @clarivateAG blog for top tips (from topic searches to working with coauthors), examples, templates and more”]

Searching the Web of Science

The Web of Science is a multidisciplinary research engine that contains over 170 million papers from more than 250 academic disciplines. All of the papers in the database are interconnected via citations. That means once you get started with your keyword search, you can follow the trail of cited and citing papers to efficiently find all the relevant literature. This is a great way to ensure you’re not missing anything important when you write a narrative literature review.

We recommend starting your search in the Web of Science Core Collection™. This database covers more than 21,000 carefully selected journals. It is a trusted source to find research papers, and discover top authors and journals (read more about its coverage here ).

Learn more about exploring the Core Collection in our blog, How to find research papers: five tips every researcher should know . Our blog covers various tips, including how to:

- Perform a topic search (and select your keywords)

- Explore the citation network

- Refine your results (refining your search results by reviews, for example, will help you avoid duplication of work, as well as identify trends and gaps in the literature)

- Save your search and set up email alerts

Try our tips on the Web of Science now.

2. Identify key papers (and know how to use them)

As you explore the Web of Science, you may notice that certain papers are marked as “Highly Cited.” These papers can play a significant role when you write a narrative literature review.

Highly Cited papers are recently published papers getting the most attention in your field right now. They form the top 1% of papers based on the number of citations received, compared to other papers published in the same field in the same year.

You will want to identify Highly Cited research as a group of papers. This group will help guide your analysis of the future of the field and opportunities for future research. This is an important component of your conclusion.

Writing reviews is hard work…[it] not only organizes published papers, but also positions t hem in the academic process and presents the future direction. Prof. Susumu Kitagawa, Highly Cited Researcher, Kyoto University

3. Tips for working with co-authors

Writing a narrative review on your own is hard, but it can be even more challenging if you’re collaborating with a team, especially if your coauthors are working across multiple locations. Luckily, reference management software can improve the coordination between you and your co-authors—both around the department and around the world.

We’ve written about how to use EndNote’s Cite While You Write feature, which will help you save hundreds of hours when writing research . Here, we discuss the features that give you greater ease and control when collaborating with your colleagues.

Use EndNote for narrative reviews

Sharing references is essential for successful collaboration. With EndNote, you can store and share as many references, documents and files as you need with up to 100 people using the software.

You can share simultaneous access to one reference library, regardless of your colleague’s location or organization. You can also choose the type of access each user has on an individual basis. For example, Read-Write access means a select colleague can add and delete references, annotate PDF articles and create custom groups. They’ll also be able to see up to 500 of the team’s most recent changes to the reference library. Read-only is also an option for individuals who don’t need that level of access.

EndNote helps you overcome research limitations by synchronizing library changes every 15 minutes. That means your team can stay up-to-date at any time of the day, supporting an easier, more successful collaboration.

Start your free EndNote trial today .

4.Finding a journal for your literature review

Finding the right journal for your literature review can be a particular pain point for those of you who want to publish. The expansion of scholarly journals has made the task extremely difficult, and can potentially delay the publication of your work by many months.

We’ve written a blog about how you can find the right journal for your manuscript using a rich array of data. You can read our blog here , or head straight to Endnote’s Manuscript Matcher or Journal Citation Report s to try out the best tools for the job.

5. Discover literature review examples and templates

There are a few tips we haven’t covered in this blog, including how to decide on an area of research, develop an interesting storyline, and highlight gaps in the literature. We’ve listed a few blogs here that might help you with this, alongside some literature review examples and outlines to get you started.

Literature Review examples:

- Aggregation-induced emission

- Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering

- Object based image analysis for remote sensing

(Make sure you download the free EndNote™ Click browser plugin to access the full-text PDFs).

Templates and outlines:

- Learn how to write a review of literature , Univ. of Wisconsin – Madison

- Structuring a literature review , Australian National University

- Matrix Method for Literature Review: The Review Matrix , Duquesne University

Additional resources:

- Ten simple rules for writing a literature review , Editor, PLoS Computational Biology

- Video: How to write a literature review , UC San Diego Psychology

Related posts

Demonstrating socioeconomic impact – a historical perspective of ancient wisdom and modern challenges.

Unlocking U.K. research excellence: Key insights from the Research Professional News Live summit

For better insights, assess research performance at the department level

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

ISI Journals

- Informing Science: The International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline (InformingSciJ)

- Journal of Information Technology Education: Research (JITE:Research)

- Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice (JITE:IIP)

- Journal of Information Technology Education: Discussion Cases (JITE: DC)

- Interdisciplinary Journal of e-Skills and Lifelong Learning (IJELL)

- Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge, and Management (IJIKM)

- International Journal of Doctoral Studies (IJDS)

- Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology (IISIT)

- Journal for the Study of Postsecondary and Tertiary Education (JSPTE)

- Informing Faculty (IF)

Collaborative Journals

- Muma Case Review (MCR)

- Muma Business Review (MBR)

- International Journal of Community Development and Management Studies (IJCDMS)

- InSITE2024 : Jul 24 - 25 2024,

- All Conferences »

- Publications

- Journals

- Conferences

The Academic Discipline of Information Technology: A Systematic Literature Review

Back to Top ↑

- Become a Reviewer

- Privacy Policy

- Ethics Policy

- Legal Disclaimer

SEARCH PUBLICATIONS

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Serv Res

- v.42(1 Pt 1); 2007 Feb

Defining Interdisciplinary Research: Conclusions from a Critical Review of the Literature

To summarize findings from a systematic exploration of existing literature and views regarding interdisciplinarity, to discuss themes and components of such work, and to propose a theoretically based definition of interdisciplinary research.

Data Sources/Study Setting

Two major data sources were used: interviews with researchers from various disciplines, and a systematic review of the education, business, and health care literature from January 1980 through January 2005.

Study Design

Systematic review of literature, one-on-one interviews, field test (survey).

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

We reviewed 14 definitions of interdisciplinarity, the characteristics of 42 interdisciplinary research publications from multiple fields of study, and 14 researcher interviews to arrive at a preliminary definition of interdisciplinary research. That definition was then field tested by 12 individuals with interdisciplinary research experience, and their responses incorporated into the definition of interdisciplinary research proposed in this paper.

Principal Findings

Three key definitional characteristics were identified: the qualitative mode of research (and its theoretical underpinnings), existence of a continuum of synthesis among disciplines, and the desired outcome of the interdisciplinary research.

Existing literature from several fields did not provide a definition for interdisciplinary research of sufficient specificity to facilitate activities such as identification of the competencies, structure, and resources needed for health care and health policy research. This analysis led to the proposed definition, which is designed to aid decision makers in funding agencies/program committees and researchers to identify and take full advantage the interdisciplinary approach, and to serve as a basis for competency-based formalized training to provide researchers with interdisciplinary skills.

As scientific knowledge in a wide range of disciplines has advanced, scholars have become increasingly aware of the need to link disciplinary fields to more fully answer critical questions, or to facilitate application of knowledge in a specific area. For example, the discovery that tobacco use was associated with high rates of lung disease was not sufficient to lead to smoking cessation; the addition of research on risk assessment, motivation, and reasoned action were all important in designing programs that have fostered the current lower rates of tobacco use. This recognition has stimulated a steadily growing interest within the scientific community in developing new knowledge through research that combines the skills and perspectives of multiple disciplines. This may be in part a parallel of the wider societal interest in holistic perspectives that do not reduce human experience to a single dimension of descriptors, and to awareness that a number of extremely important and productive fields of study are themselves interdisciplinary: biochemistry, biophysics, social psychology, geophysics, informatics, and others. Recent publications in Health Services Research exemplify the complexities involved in health services research and the need for an interdisciplinary approach ( Glied et al. 2005 ; Gonzales et al. 2005 ; Hunt, Gaba, and Lavizzo-Mourey 2005 ; McLaughlin 2005 ).

A number of research centers funded over the past decade by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; e.g., Center for Evidence-Based Practice in the Underserved; Center on Population, Gender, and Social Inequality; Interdepartmental Neuroscience Center) are labeled as interdisciplinary and have involved scholars from multiple disciplines in productive research endeavors. NIH has identified interdisciplinarity as an essential contributor to needed knowledge and made it an explicit priority in its recent Roadmap. The Roadmap, a new strategic plan for future NIH funding ( http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/interdisciplinary/index.asp ), describes interdisciplinary research as that which:

- integrates the analytical strengths of two or more often disparate scientific disciplines to solve a given biological problem. For instance, behavioral scientists, molecular biologists, and mathematicians might combine their research tools, approaches, and technologies to more powerfully solve the puzzles of complex health problems such as pain and obesity. By engaging seemingly unrelated disciplines, traditional gaps in terminology, approach, and methodology might be gradually eliminated . With roadblocks to potential collaboration removed, a true meeting of minds can take place: one that broadens the scope of investigation into biomedical problems, yields fresh and possibly unexpected insights, and may even give birth to new hybrid disciplines that are more analytically sophisticated (emphasis added).

While descriptive statements and lists of disciplines may be of value in informing observers about interdisciplinary research, they lack the precision needed to determine whether a given research effort is truly interdisciplinary, or simply happens to have been conducted by individuals with different credentials or employed in different academic departments.

Although scholars in the health sciences have developed research teams that often include members of multiple disciplines, the nature of interdisciplinarity and the concept of interdisciplinary research varies across disciplines, as do expectations and values of participants regarding the process of interdisciplinary research. A more precise definition of interdisciplinary research is needed so that funding agencies and researchers themselves can identify the competencies and resources necessary for successful interdisciplinary contributions to science. Such knowledge would be of great use in guiding both research design and funding decisions.

One endeavor to support and enhance interdisciplinary research within the Roadmap is the funding of 21 exploratory centers for interdisciplinary research ( http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/interdisciplinary/exploratorycenters/ ). The authors are associated with one of these interdisciplinary centers, the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on Antimicrobial Resistance (CIRAR, http://www.cumc.columbia.edu/dept/nursing/CIRAR/ ). Currently our research collaborative team includes persons from the disciplines of epidemiology, microbiology, pediatrics, infectious disease, nursing, economics, health policy, education, biostatistics, economics, informatics, public health, and more. Before joining CIRAR, these individuals had been engaged in research programs that range from bench science at the cellular level, clinical trials in hospitals and communities, cost–benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis and community-based participatory research. All of the members of CIRAR have engaged in collaborative work in the past, using their own sense of good scholarship to guide the process. Like many researchers, their experience with the “practice” of interdisciplinarity is a valuable resource, but in order to realize the full potential of this approach to research there must be an effort made to pool these resources across multiple fields.

The purpose of this paper is to summarize findings from a systematic exploration of existing literature and views regarding interdisciplinarity, to discuss themes and components of such work, and to propose a theoretically based definition of interdisciplinary research. Before the review of literature, the authors held interviews with individuals engaged in successful research involving multiple disciplines. A preliminary definition based on the interviews and subsequent literature review was composed. The definition was then field tested and modified to arrive at our proposed definition of interdisciplinary research. The aim of the project was to propose a definition that could then be used, among other applications, to identify the competencies needed for successful interdisciplinary research practice from which curriculum to teach interdisciplinarity could be developed.

This analysis of interdisciplinary research used two primary data sources: interviews with experienced researchers and a systematic literature review. The first data source was a series of one-on-one systematic interviews conducted by the CIRAR director with the 14 researchers (physicians, nurses, and researchers from public health and the social sciences) who were core members of the CIRAR interdisciplinary research center. These individuals had been selected for Center membership because they were experienced and successful researchers whose work bridged several disciplines. In these interviews, respondents were queried regarding their own work styles and the specific characteristics, which they sought in others in order to achieve successful interdisciplinary collaborations. The interviewer asked 10 questions on the researcher's attitudes and behaviors regarding their own professional lives and their disciplinary and interdisciplinary collaborations. The responses were categorized and summarized descriptively.

The larger data source was a systematic literature review conducted in three bodies of academic literature: education, business, and health care. Each was searched by one or more collaborators with expertise in the respective field. Inclusive dates for searches were January 1980 through January 2005 (25 years); only English language books and peer-review journal articles were included, and search terms used were “interdisciplinarity,” “interdisciplinary research,” and “collaborative research.” Databases searched included ProQuest ABI/INFORM Global ( http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb ), which includes business, economics, and management literature; PubMed ( http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?DB =pubmed ) for biomedical literature; and the Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC) database: (Washington, DC: Office of Educational Research and Improvement, U.S. Department of Education) for educational literature. In addition to the peer-reviewed search engines, a review of unindexed reports and publications from health-related foundations with a known interest in interdisciplinary efforts was added. In the articles reviewed, factors identified as important to the success of interdisciplinary research were categorized as environmental/institutional factors, team factors, or individual characteristics of team members.

The initial search produced over 500 sources related in some way to interdisciplinarity. Articles or books were then evaluated for their content; only sources that addressed some aspect of the interdisciplinary research process and theory were included. Many of the sources excluded were examples of interdisciplinary research studies that did not include an analysis of the interdisciplinary process itself or any discussion of definitions.

Based on information synthesized from the literature review and the researcher interviews, a preliminary definition of interdisciplinary research was composed. As a final step, this preliminary definition was field tested by a set of researchers experienced in interdisciplinary work. Twelve individuals (four senior researchers with extensive interdisciplinary experience from academic institutions in three other states and eight members of CIRAR) were asked to review both the NIH definition of interdisciplinary research and the preliminary definition proposed by selected members of the CIRAR Interdisciplinary Working Group based upon a review of the literature. No one involved in the creation of the draft definition participated in the field test. Each individual completed a written survey that included both the NIH definition and draft definition. They were asked to identify critical elements of the draft definition, delete elements that did not belong in the definition, suggest additions from the NIH definition, and make other suggestions related to additions or refinements.

Researcher Interviews

Themes that emerged regarding successful interdisciplinary work included respect for the scientific process and importance of collaborative research; identifying interesting topics; management, focus, and editing of work; and the ability to make mistakes gracefully. The researchers interviewed were seasoned professionals with a history of successful interdisciplinary research; their attitudes and behaviors toward scholarly work and collaboration was greatly informative as successful “case studies.” They identified 27 personal characteristics that they valued in collaborators and 13 ways in which interdisciplinary research could contribute to their work. Although the data from these interviews helped in getting a sense for how senior interdisciplinary researchers think, no definitional specifics emerged from these interviews.

Literature Search

While >500 articles or books related to the general theme of interdisciplinarity were initially identified, only 42 articles or books were specific to the topic of interdisciplinary research (as opposed to examples of interdisciplinary research). The majority of these papers (30/42, 71.4 percent) were from the health and social sciences literature and had a mean of 2.8 ( Table 1 ) ( Allen 1992 ; Barnes, Pashby, and Gibbons 2002 ; Beersma et al. 2003 ; Aram 2004 ; Cummings 2004 ; Hobman, Bordia, and Gallois 2004 ; Guimera et al. 2005 ) authors/article, 59.5 percent of whom were from the social sciences. Of these papers, one-third (14, 33.3 percent) were empirically based research about interdisciplinarity ( Allen 1992 ; White 1999 ; Kone et al. 2000 ; Sullivan et al. 2001 ; Barnes, Pashby, and Gibbons 2002 ; Lattuca 2002 ; Beersma et al. 2003 ; Morillo, Bordons, and Gomez 2003 ; Schulz, Israel, and Lantz 2003 ; Aram 2004 ; Cummings 2004 ; Hobman, Bordia, and Gallois 2004 ; Senior and Swailes 2004 ; Guimera et al. 2005 ); the others were general discussions ( Woollcott 1979 ; Jacobs and Borland 1986 ; Bloedon and Stokes 1994 ; Nissani 1997 ; Israel et al. 1998 ; Lindauer 1998 ; Northridge et al. 2000 ; Stead and Harrington 2000 ; Anderson 2001 ; Aagaard-Hansen and Ouma 2002 ; Board of Health Care Services 2003 ; Frost and Jean 2003 ; Nyden 2003 ; Jacobson, Butterill, and Goering 2004 ; Slatin et al. 2004 ), cases studies ( Dodgson 1992 ; Rosenfield 1992 ; Bisby 2001 ; Higgins, Maciak, and Metzler 2001 ; Lantz et al. 2001 ; Lattuca 2001 ; Cheadle et al. 2002 ; Austin 2003 ; Baba et al. 2004 ; Daniels 2004 ; Tennenhouse 2004 ) and one literature review ( Berkowitz 2000 ). Eleven (26.1 percent) of the papers included an explicit definition of interdisciplinarity and only five papers (11.9 percent) described or cited any type of conceptual framework or theoretical underpinnings for their approach to interdisciplinary research (three distinct typologies, see Table 2 ).

Reviewed Articles from the Health Care, Business, and Education Literatures ( n =42)

Typologies of Interdisciplinary Research

Authors described multiple factors essential to the success of interdisciplinary work. In these papers, 54.8 percent discussed environmental/institutional factors such as an explicit institutional commitment to interdisciplinarity and sufficient resources; 61.9 percent mentioned team factors such as communication, leadership, and trust; and 19.0 percent described individual characteristics of team members such as commitment, flexibility, and being agreeable to work with.

Divergent Paradigms of Interdisciplinary Research

Divergent paradigms of inquiry were reflected in the physical and social sciences as contrasted with the humanities, with associated differences in methodologies and premises. The physical and social sciences employed a positivist or postpositivist mode of inquiry in which an appreciable reality exists and is objectively (although sometimes imperfectly) knowable. The methodologies of the physical and social sciences are primarily hypothesis driven and use experimentation and manipulation to achieve objectivism. The typology proposed by Rosenfield (1992) ( Table 2 ), consistent with the hypothesis-driven approach employed by these fields in which the starting point for all collaborations is a common problem or question, was most cited by references from the social, health, and physical sciences. The humanities employed a critical theory or constructivist mode of inquiry in which reality is experientially based, historically shaped, and its understanding is only relative in nature. The methodologies are not hypothesis driven and the approach emphasizes subjectivism and the inherent interaction between the investigator and the subject, as defined by Guba and Lincoln (1994) . The finding that qualitative modes were a key feature suggests that the quantitative approach is more of a technique than a way of knowing. Explicated assumptions and values are part of qualitative inquiry, and perhaps better set the stage for dialogue.

Key Definitional Components

Of the 42 references identified, 14 contained some language describing key definitional components of interdisciplinary research. The components offered were a synthesis of both the author's personal experience and his or her knowledge of the interdisciplinary literature. A single exception ( Morillo, Bordons, and Gomez 2003 ) was an attempt to empirically define interdisciplinarity based on bibliometric methods in which the degree of interdisciplinarity of a given field of study was determined by the number of subject categories assigned to disciplinary journals by the various citation indices.

The key definitional components from the literature review were:

- Qualitatively different modes of interdisciplinary research There were three predominant typologies of interdisciplinary research cited in the literature. Distinctions were often made based upon where along the continuum of synthesis the various disciplines fell. Different points along the continuum represent qualitatively different forms of collaboration. These typologies are categorized in Table 2 .

- Existence of a continuum of collaboration . In all sources there was common acknowledgement of a continuum with respect to interdisciplinary research and the degree of synthesis involved in the process and achieved in the outcome. One example describing the process: “interaction may range from simple communication of ideas to the mutual integration of organizing concepts, methodology, procedures, epistemology, terminology, data, and organization of research and education in a fairly large field.”( OECD [1998] quoted in Morillo, Bordons, and Gomez [2003 , p. 1237]).

- Definition and fidelity to disciplinarity . Several references defined the disciplinarity of interacting members by content (e.g., “thought domains” [ Aram 2004 ], “specific body of teachable knowledge” [ Woollcott 1979 ], “conceptual specificity” [ Robertson, Martin, and Singer 2003 ], or “journal sets” [ Morillo, Bordons, and Gomez 2003 ]) or by social factors (e.g.,“isolated domains of human experience possessing its own community of experts” [ Nissani 1997 ], or “self-regulating and self-sustaining communities” [ Lattuca 2002 ]).

- Degree of cooperation or interaction . A critical component of a vast majority of the definitions was the degree of cooperation or interaction between members of the collaborative teams, the amount of contact between team members and the degree of sharing of information. Modes of interdisciplinary research with low degrees of synthesis (see Table 2 ) necessitate very little, if any, cooperation between researchers. Modes of interdisciplinary research with even a moderate degree of synthesis between disciplines require ever-greater degrees of interaction between researchers. Distinctions were often made with respect to what is shared, that is, whether it is limited to the specific research topic of concern or extended to include discussions regarding methods and conceptual frameworks.

Characteristics of Multidisciplinary, Interdisciplinary, and Transdisciplinary Research

- Outcome of the collaboration (e.g., solution to discrete problem, new language). Finally, the outcome of the collaboration was often included as a component of the definition. Authors noted that interdisciplinary research may result in the solution of a discreet problem, a single or group of publications, the development of a new field and/or language, and by some in the humanities, the process of the interdisciplinary endeavor itself was the intended outcome. Transdisciplinary endeavors set out to create synthesis between disciplines and are the mode most likely to result in the development of a new field of study or language.

A preliminary definition of interdisciplinary research was developed, based on the key themes and continuum identified in the literature search: “Any study or group of studies undertaken by scholars from two or more distinct academic fields, based on a conceptual model that links or integrates theoretical frameworks from those disciplines, using study design and methodology that is not limited to any one field, and requiring the use of perspectives and skills of the involved disciplines in all phases from study design through data collection, data analysis, specifying conclusions and preparing manuscripts and other reports of work completed.” This preliminary definition was then subjected to a field test of review by twelve experts in interdisciplinary research. All but one reviewer had self-identified expertise in more than one discipline including biochemistry, economics, epidemiology, genetics, health care-associated infections, health policy, infectious disease, internal medicine, medicine, microbiology, molecular biology, nursing, nursing informatics, patient safety, pharmacology, pharmacy, public health, quantitative research, radiology, sociomedical sciences, women's health, and infectious diseases.