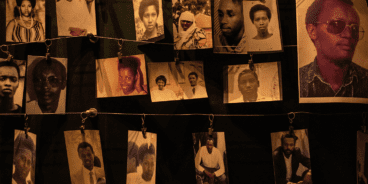

Cambodia 1975–1979

An exhumed mass grave in Cambodia yields skeletons of the executed. October 10, 1981. —David Allen Harvey/National Geographic Creative

“To keep you is no gain; to lose you is no loss.”

From April 17, 1975, to January 7, 1979, the Khmer Rouge perpetrated one of the greatest crimes of the 20th century. Nearly two million people died under the rule of the fanatical Communist movement, which imposed a ruthless agenda of forced labor, thought control, and mass execution on Cambodia. The purported goal was to transform the Southeast Asian country into a classless agrarian utopia. The result was an ancient society’s wholesale destruction and a horrifying new term for the world to confront: “the killing fields.”

The Khmer Rouge began their reign with the murder of surrendering officials of the former government and the brutal emptying of the capital and other cities. Black-clad soldiers marched millions of people into the countryside and put them to work as slaves digging canals and tending crops. Religion, popular culture, and all forms of self-expression were forbidden. Families were split apart, with children forced into mobile labor brigades. Anyone who questioned the new order risked torture and death by a blow to the head. Ethnic minorities faced particular persecution. Not even members of the Khmer Rouge were safe. The movement killed thousands of its own as suspected traitors and spies for foreign powers. In time, gross mismanagement of the economy led to shortages of food and medicine, and untold numbers of Cambodians succumbed to disease and starvation. An invasion by neighboring Vietnam finally toppled the regime. But a new civil war began and almost three decades passed before any Khmer Rouge leaders were brought to justice. In 2006, the United Nations and the Cambodian government inaugurated a joint tribunal known as the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC). So far it has convicted three defendants and sentenced them to lengthy prison terms.

Khmer Rouge ideological leader Nuon Chea in the dock at the tribunal in Phnom Penh. —ECCC/Nhet Sok Heng

Survivor Sophany Bay, testifying before the Khmer Rouge tribunal, holds up a photo of one of her three children, all whom died during the regime's rule. —ECCC

The court functions not only to return verdicts but also to try to give some measure of peace and resolution to victims and to Cambodian society as a whole. Its proceedings are open to the public; victims can register as “civil parties” to question defendants during trial sessions and seek various types of reparations.

The court has drawn criticism for the high cost of operation and the low number of indictments. But whatever its flaws, it reflects a strengthening global consensus that, no matter how much time has passed, perpetrators of the modern era’s worst crimes must be brought to account, in a framework that helps survivors repair their lives.

The Museum is grateful to the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, Kingdom of Cambodia; the Documentation Center of Cambodia; and the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia for their support and materials used in this case history.

This page was last updated in April 2018.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Khmer Rouge

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 21, 2018 | Original: September 12, 2017

The Khmer Rouge was a brutal regime that ruled Cambodia, under the leadership of Marxist dictator Pol Pot , from 1975 to 1979. Pol Pot’s attempts to create a Cambodian “master race” through social engineering ultimately led to the deaths of more than 2 million people in the Southeast Asian country. Those killed were either executed as enemies of the regime, or died from starvation, disease or overwork. Historically, this period—as shown in the film The Killing Fields —has come to be known as the Cambodian Genocide.

Although Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge didn’t come to power until the mid-1970s, the roots of their takeover can be traced to the 1960s, when a communist insurgency first became active in Cambodia, which was then ruled by a monarch.

Throughout the 1960s, the Khmer Rouge operated as the armed wing of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, the name the party used for Cambodia. Operating primarily in remote jungle and mountain areas in the northeast of the country, near its border with Vietnam, which at the time was embroiled in its own civil war, the Khmer Rouge did not have popular support across Cambodia, particularly in the cities, including the capital Phnom Penh.

However, after a 1970 military coup led to the ouster of Cambodia’s ruling monarch, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the Khmer Rouge decided to join forces with the deposed leader and form a political coalition. As the monarch had been popular among city-dwelling Cambodians, the Khmer Rouge began to glean more and more support.

HISTORY Vault: Pol Pot

The life story of one of the world's most mysterious & ruthless mass murderers. Hear from those who knew him as a boy, as a radical student in the 1950s, & who were by his side when he was head of the Khmer Rouger Government in the 1970s.

For the next five years, a civil war between the right-leaning military, which had led the coup, and those supporting the alliance of Prince Norodom and the Khmer Rouge raged in Cambodia. Eventually, the Khmer Rouge side seized the advantage in the conflict, after gaining control of increasing amounts of territory in the Cambodian countryside.

In 1975, Khmer Rouge fighters invaded Phnom Penh and took over the city. With the capital in its grasp, the Khmer Rouge had won the civil war and, thus, ruled the country.

Notably, the Khmer Rouge opted not to restore power to Prince Norodom, but instead handed power to the leader of the Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot. Prince Norodom was forced to live in exile.

As a leader of the Khmer Rouge during its days as an insurgent movement, Pol Pot came to admire the tribes in Cambodia’s rural northeast. These tribes were self-sufficient and lived on the goods they produced through subsistence farming.

The tribes, he felt, were like communes in that they worked together, shared in the spoils of their labor and were untainted by the evils of money, wealth and religion, the latter being the Buddhism common in Cambodia’s cities.

Once installed as the country’s leader by the Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot and the forces loyal to him quickly set about remaking Cambodia, which they had renamed Kampuchea, in the model of these rural tribes, with the hopes of creating a communist-style, agricultural utopia.

Declaring 1975 “Year Zero” in the country, Pol Pot isolated Kampuchea from the global community. He resettled hundreds of thousands of the country’s city-dwellers in rural farming communes and abolished the country’s currency. He also outlawed the ownership of private property and the practice of religion in the new nation.

Cambodian Genocide

Workers on the farm collectives established by Pol Pot soon began suffering from the effects of overwork and lack of food. Hundreds of thousands died from disease, starvation or damage to their bodies sustained during back-breaking work or abuse from the ruthless Khmer Rouge guards overseeing the camps.

Pol Pot’s regime also executed thousands of people it had deemed as enemies of the state. Those seen as intellectuals, or potential leaders of a revolutionary movement, were also executed. Legend has it, some were executed for merely appearing to be intellectuals, by wearing glasses or being able to speak a foreign language.

As part of this effort, hundreds of thousands of the educated, middle-class Cambodians were tortured and executed in special centers established in the cities, the most infamous of which was Tuol Sleng jail in Phnom Penh, where nearly 17,000 men, women and children were imprisoned during the regime’s four years in power.

During what became known as the Cambodian Genocide , an estimated 1.7 to 2.2 million Cambodians died during Pol Pot’s time in charge of the country.

The End of Pol Pot

The Vietnamese Army invaded Cambodia in 1979 and removed Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge from power, after a series of violent battles on the border between the two countries. Pol Pot had sought to extend his influence into the newly unified Vietnam, but his forces were quickly rebuffed.

After the invasion, Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge fighters quickly retreated to remote areas of the country. However, they remained active as an insurgency, albeit with declining influence. Vietnam retained control in the country, with a military presence, for much of the 1980s, over the objections of the United States.

Over the decades since the fall of the Khmer Rouge, Cambodia has gradually reestablished ties with the world community, although the country still faces problems, including widespread poverty and illiteracy. Prince Norodom returned to govern Cambodia in 1993, although he now rules under a constitutional monarchy.

Pol Pot himself lived in the rural northeast of the country until 1997, when he was tried by the Khmer Rouge for his crimes against the state. The trial was seen as being mostly for show, however, and the former dictator died while under house arrest in jungle home.

The stories of the suffering of the Cambodian people at the hands of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge have garnered worldwide attention in the years since their rise and fall, including through the 1984 movie The Killing Fields, an account of the atrocities based on the book The Death and Life of Dith Pran by journalist Sydney Schanberg.

Cambodia’s brutal Khmer Rouge regime. BBC News . The Cambodian Genocide. United to End Genocide . Cambodian Genocide. World Without Genocide. The Khmer Rouge and Pol Pot’s Regime. Mount Holyoke College. Cambodia: The World Factbook. CIA .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Search form

Modern southeast asia.

- Syllabus 2021

- Professor Harms

- Course Bibliography

- Syllabus 2020

- Syllabus 2018

- Syllabus Fall 2018 (Yale-NUS)

- Reading Responses

- Headlines Essays

- Final Essay Proposals

- Final Essays

- Ripped from the Headlines

- Western Media

- Southeast Asia Media

- Suggested Readings

- Misc Research

- Khu Tao sống Translation

- Digital Vietnam Presenters and Videos Clips

You are here

The cambodian genocide, 1975-1979 (ben kiernan, 2004).

Kiernan, Ben (2004). The Cambodian Genocide, 1975-1979. A Century of Genocide Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts . Samuel Totten et al, Ed. New York, Routledge : 338-373.

Ben Kiernan, in “The Cambodian Genocide, 1975-1979”, provides a detailed account of the Pol Pot regime’s systematic attempt to exterminate ethnic, religious, and cultural minorities from Cambodia. The essay is divided into three sections. The first is a facts-based retelling of the Khmer Rouge’s genocidal campaign in the late 1970s, from the rise of Pol Pot to the excruciating details of how the regime attempted to subjugate or eliminate different demographic groups. The second section is a comparison of two scholars’ interpretations of the Cambodian genocide along with Kiernan’s own commentary. And the third is a selection of first-hand accounts from survivors of the Khmer Rouge as collected and transcribed by Kiernan and Chanthou Boua. Through these three lenses, Kiernan provides a factually rich and emotionally compelling perspective of a dark period in Cambodia’s history.

Pol Pot’s rise to power

In the first third of the essay, Kiernan recounts how Pol Pot, the leader of Cambodia’s genocidal Khmer Rouge, developed intellectually and came to power. Pol Pot was born Saloth Sar to a large family of Khmer peasants. Pol Pot’s parents owned 9 hectares of riceland and six buffalo, however, and even had royal connections—they were “peasants with a difference” (Kiernan 342). He would have no experience farming and would be relatively ignorant of village life. In 1948, Pol Pot received a scholarship to study in Paris and involved himself in political life. When he returned home in 1953 after flunking out of his program, Pol Pot responded to King Sihanouk’s declaration of martial law in Cambodia by following his closest brother to join the Cambodian and Vietnamese Communists. In 1966 the party changed its name to the “Communist Party of Kampuchea” (CPK) and in 1975 it was victorious over Sihanouk’s successor regime. They proclaimed the state of Democratic Kampuchea, with Pol Pot as secretary general.

Having narrated the rise of the CPK under Pol Pot and his collaborators’ leadership, Kiernan details how the Party established and maintained control over DK. CPK leadership sealed off Cambodia from communications, closing borders, banning foreign language, and suppressing local journalism. They violently purged the Party of dissenters and individuals “too close” to Vietnam’s Communists. And CPK forces systematically took control of and purged each of DK’s major zones. With control over the whole of DK, Pol Pot and his collaborators began to execute a political program based on their “national and racial grandiosity” (Kiernan 346). Kiernan describes their belief system as such: Cambodia did not need to import anything, including knowledge, from its neighboring countries. It could recover its pre-Buddhist glory by rebuilding its society (and economy) in the image of the medieval Angkor kingdom.

A systematic campaign of extermination

A major form this “rebuilding” took was the eradication of Buddhism from Cambodia. By Kiernan’s estimation, fewer than 2,000 of Cambodia’s 70,000 Buddhist monks may have survived the massacres. In addition to the extermination of Buddhism and its practitioners from the country, the Party targeted the Vietnamese, Chinese, and Muslim Cham minorities. While these groups made up a total of 15% of Cambodia’s population, Pol Pot’s regime claimed they were less than 1% of the population. Hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese Cambodians were expelled or murdered in what Kiernan calls a “campaign of systematic racial extermination” (Kiernan 347). The Chinese population, 425,000 in 1975, was reduced to 200,000 over the next four years. The largely urban ethnic Chinese were targeted, Kiernan believes, less for their race than for their city-dwelling status. They were forced to work in deplorable conditions, succumbing to disease and hunger, and had their language and culture banned. Finally, the Muslim Chams suffered greatly for their distinct religion, language, and culture. After rebellions against the new government, all 113 Cham villages were emptied and about 100,000 individuals murdered. Islamic schools and religious practices were banned, as well as the Cham language. Many were forced to eat pork, or were murdered if they refused. The result of this four-year campaign to exterminate racial and cultural minorities from Cambodia did not limit itself to those in the aforementioned minority groups, and not even those in the peasant majority fared well under the regime.

International responses and scholarship

In the second section of the essay, Kiernan addresses the international community’s attitudes toward the Khmer Rouge and its leadership. A key takeaway is that the United States, its allies, and the United Nations failed to condemn the campaign of extermination that took place in Cambodia from 1975-1979. In particular, the United States continued to support the Pol Pot regime because it desired Cambodia’s independence as a counterweight to Chinese influence in Southeast Asia. Kiernan also provides two contrasting examples of scholars’ interpretations of the Khmer Rouge’s actions. The pro-Chinese neo-Marxist Samir Amin initially praised DK as a model for African socialists to follow, though in 1981 he conceded it suffered from “excesses” because it was a “principally peasant revolution” (Kiernan 357). Historical Michael Vickery seized on this idea in 1984 as reason to reject DK, writing that “nationalism, populism and peasantism really won out over communism” (Kiernan 357, quoting Vickery 1984, p. 289). Kiernan effectively points out flaws in both scholars’ arguments about the nature of the Pol Pot regime. In particular, he notes how Vickery failed to collect first-hand testimony from witnesses of diverse backgrounds to support his claims about the conditions of various peasant groups. Kiernan also introduces a major controversy in the historiography of the Cambodian revolution: the “central control” question. Scholars debated whether the Pol Pot regime was a centralised dictatorship or a chaotic project driven by peasant whims; Kiernan claims the regime was only capable of such mass murder because it had concentrated power. Today, consensus supports Kiernan’s contention that the events of 1975-1979 constituted genocide. A collection of primary source documents from the Khmer Rouge regime lives at Yale and will fuel continued investigations into the genocide.

First-hand accounts of the Cambodian genocide

Finally, Kiernan introduces several first-hand accounts of the Cambodian genocide from individuals belonging to targeted minority communities — including a Muslim Cham woman named Nao Gha. He also includes the perspectives of two peasant boys, Sat and Mien, who eventually fled to Thailand after being forced to labor in dire conditions under the Khmer Rouge. These transcriptions add human context to the facts and figures Kiernan gave at the outset. Kiernan does not add commentary to the interviews. Instead, he allows the stories of these witnesses to take center stage and add credibility to the entirety of the essay.

I have little to add to Kiernan’s essay on the Cambodian genocide. His neutral language and limited communication of his personal opinions allowed the horror of Pol Pot’s state-sponsored genocide to command the reader’s full attention. He provides many lenses through which readers can interpret this period in Cambodia’s history – politics, human rights, biography, international relations, and first-hand narratives.

It was disappointing but unsurprising to learn that the international community failed to take immediate action against the Khmer Rouge, as geopolitical concerns dwarfed human rights issues in importance to state actors. And it was fascinating to see how different scholars interpreted the same series of events, each impacted by his own political beliefs and biases. Finally, it was disturbing but important to read through the first-hand accounts of the atrocities committed by the Pol Pot regime. I appreciate that Kiernan earlier criticized other scholars for their lack of diverse first-hand accounts, then did the necessary work to collect and transcribe such accounts. This is recommended reading for anyone unfamiliar with the details of the Cambodian genocide or wishing to better understand its events in context.

“The late 20th century saw the era of mass communications, but DK tolled a vicious silence. Internally and externally, Cambodia was sealed off. Its borders were closed, all neighboring countries militarily attacked, use of foreign languages banned, embassies and press agencies expelled, local newspapers and television shut down, radios and bicycles confiscated, mail and telephones suppressed.” (Kiernan 344)

Fascinating and disturbing to see listed the mechanisms of control the Party used – would be interested to learn how these methods compare with other authoritarian/genocidal regimes.

“The Vietnamese community, for example, was entirely eradicated… In research conducted in Cambodia since 1979 it has not been possible to find a Vietnamese resident who had survived the Pol Pot years there.” (Kiernan 347)

“The Chinese under Pol Pot’s regime suffered the worst disaster ever to befall any ethnic Chinese community in Southeast Asia.” (Kiernan 347)

“About 100,000 Chams were massacred… Islamic schools and religion, as well as the Cham language, were banned. Thousands of Muslims were physically forced to eat pork. Many were murdered for refusing.” (Kiernan 348)

“…While the Cambodian genocide progressed, Washington, Bejing, and Bangkok all supported the continued independent existence of the Khmer Rouge regime.” (Kiernan 354)

“They also executed college students and former government officials, soldiers, and police. I saw the bodies of many such people not far from the village.” (Thoun Cheng, first-hand account recorded by Ben Kiernan and Chanthou Boua)

There is at first less discussion of the non-ethnic/religious targets of the Khmer Rouge’s extermination program, but this speaks to the regime’s hatred of anyone educated or involved in prior governments.

“I was never allowed to eat any of the fruits of my labor, all of which were carted away by truck; I don’t know where.” (Sat, a peasant boy who lived through the genocide in Cambodia, account recorded by Kiernan and Boua)

Particularly ironic, as the revolution was supposedly for the benefit of the peasant class. Sat, a peasant boy, works constantly for the regime yet cannot even eat what he produces. His account also implicitly weakens many of Amin and Vickery’s claims about the ideology of the Pol Pot regime.

Based on this essay, how does Kiernan define genocide and what are the key points he makes in support of his claim that a genocide took place in Cambodia 1975-1979?

What was the driving ideology behind the attempts of the Khmer Rouge to eliminate groups like the Buddhists, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Muslim Cham from Cambodia?

As recently as 1991, the UN failed to condemn the events in Cambodia as genocide with reference to the Genocide Convention. And during the reign of the Khmer Rouge, international actors and commentators alike failed to publicly recognize the regime for what it was. International legal organisations also dismissed proposals to investigate the crimes committed by the DK regime in the decades after Pol Pot’s overthrow. What caused this inaction in the international community, and was this avoidable? Is it unreasonable to hope that this would not happen in the future?

How should scholars or politicians interested in communist ideology, like Stalinism or some aspects of Maoism, approach discussion of the Khmer Rouge? Note how Samir Amin and Michael Vickery address the influence (or lack thereof) of international communist models on Pol Pot’s regime, peasant participation, and urban vs. peasant conflict.

You certainly went above and beyond the call of duty with this review of the reading. Very comprehensive and thorough!

I suppose my question for you is not about this text, then, but about your feelings about the capacity historical writing has to convey the horror of a genocidal regime in general. I have read this text by Kiernan numerous times and agree with everthing you note in your review. But I always end the reading dry eyed and a bit distanced from the events. Meanwhile, when I watch New Year Baby I find myself moved in an indescribable way. Given this, what are ways that historical writing can bring in the power of affect in ways that the film does?

Professor Harms – Thank you for the kind comment! I just saw this. I think the answer to your question is that different people are affected emotionally (and driven to seek change for the better) by different styles. Personally, I got chills and was very moved by Kiernan’s text and was for some reason not more moved by the New Year Baby film. (But I agree, it is very well done and difficult to watch.) Clearly, others might feel differently and therefore it’s ideal for multiple framings of the horror of the Cambodian genocide to exist to get the message across. Also, different approaches to communication – emotionally affected vs. dry and factual – are effective in different spaces, for example in legal matters the fact-based approach is valuable. It’s certainly important to have individuals doing both kinds of work!

Time Essay: Cambodia: An Experiment in Genocide

The enormity of the tragedy has been carefully reconstructed from thereports of many eyewitnesses. Some political theorists have defendedit, as George Bernard Shaw and other Western intellectuals defended thebrutal social engineering in the Soviet Union during the 1930s. Yet itremains perhaps the most dreadful infliction of suffering on a nationby its government in the past three decades. The nation is Cambodia.

On the morning of April 17, 1975, advance units of Cambodia’s Communistinsurgents, who had been actively fighting the defeated Western-backedgovernment of Marshal Lon Nol for nearly five years, began entering thecapital of Phnom Penh. The Khmer Rouge looted things, such as watchesand cameras, but they did not go on a rampage. They seemed disciplined.And at first, there was general jubilation among the city’s terrified,exhausted and bewildered inhabitants. After all, the civil war seemedfinally over, the Americans had gone, and order, everyone seemed toassume, would soon be graciously restored.

Then came the shock. After a few hours, the black-uniformed troopsbegan firing into the air. It was a signal for Phnom Penh’s entirepopulation, swollen by refugees to some 3 million, to abandon the city.Young and old, the well and the sick, businessmen and beggars, were allordered at gunpoint onto the streets and highways leading into the countryside.

Among the first pitiful sights on the road, witnessed by severalWesterners, were patients from Phnom Penh’s grossly overcrowdedhospitals, perhaps 20,000 people all told. Even the dying, the maimedand the pregnant were herded out stumbling onto the streets. Severalpathetic cases were pushed along the road in their beds by relatives,the intravenous bottles still attached to the bedframes. In somehospitals, foreign doctors were ordered to abandon their patients inmid-operation. It took two days before the Bruegel-like multitude wasfully under way, shuffling, limping and crawling to a designatedappointment with revolution.

With almost no preparations for so enormous an exodus —how could therehave been with a war on?—thousands died along the route, the woundedfrom loss of blood, the weak from exhaustion, and others by execution,usually because they had not been quick enough to obey a Khmer Rougeorder. Phnom Penh was not alone: the entire urban population ofCambodia, some 4 million people, set out on a similar grotesquepilgrimage. It was one of the greatest transfers of human beings inmodern history.

The survivors were settled in villages and agricultural communes allaround Cambodia and were put to work for frantic 16-or 17-hour days,planting rice and building an enormous new irrigation system. Many diedfrom dysentery or malaria, others from malnutrition, having been forcedto survive on a condensed-milk can of rice every two days. Still otherswere taken away at night by Khmer Rouge guards to be shot or bludgeonedto death. The lowest estimate of the bloodbath to date —by execution,starvation and disease—is in the hundreds of thousands. The highestexceeds 1 million, and that in a country that once numbered no morethan 7 million. Moreover, the killing continues, according to the latest refugees.

The Roman Catholic cathedral in Phnom Penh has been razed, and even thenative Buddhism is reviled as a “reactionary” religion. There are noprivate telephones, no forms of public transportation, no postalservice, no universities. A Scandinavian diplomat who last year visitedPhnom Penh—today a ghost city of shuttered shops, abandoned officesand painted-over street signs—said on his return: “It was like anabsurd film; it was a nightmare. It is difficult to believe it is true.”

Yet, why is it so difficult to believe? Have not the worst atrocities ofthe 20th century all been committed in the name of some perverse pseudoscience, usually during efforts to create a new heaven on earth, oreven a “new man”? The Nazi notion of racial purity led inexorably toAuschwitz and the Final Solution. Stalin and Mao Tse-tung sent millionsto their deaths in the name of a supposedly moral cause—in their case,the desired triumph of socialism. Now the Cambodians have takenbloodbath sociology to its logical conclusion. Karl Marx declared thatmoney was at the heart of man’s original sin, the acquisition ofcapital. The men behind Cambodia’s Angka Loeu (Organization on High),who absorbed such verities while students in the West, have decided toabolish money.

How to do that? Well, one simplistic way was to abolish cities, becausecities cannot survive without money. The new Cambodian rulers did justthat. What matter that hundreds of thousands died as the cities weredepopulated? It apparently meant little, if anything, to Premier PolPot and his shadowy colleagues on the politburo of DemocraticKampuchea, as they now call Cambodia. When asked about the figure of 1million deaths, President Khieu Samphan replied: “It’s incredible howconcerned you Westerners are about war criminals.” Radio Phnom Penheven dared to boast of this atrocity in the name of collectivism: “Morethan 2,000 years of Cambodian history have virtually ended.”

Somehow, the enormity of the Cambodian tragedy—even leaving aside thegrim question of how many or how few actually died in Angka Loeu ‘sexperiment in genocide—has failed to evoke an appropriate response ofoutrage in the West. To be sure, President Carter has declared Cambodiato be the worst violator of human rights in the world today. And, true,members of the U.S. Congress have ringingly denounced the Cambodianholocaust. The U.N., ever quick to adopt a resolution condemning Israelor South Africa, acted with its customary tortoise-like caution whendealing with a Third World horror: it wrote a letter to Phnom Penhasking for an explanation of charges against the regime.

Perhaps the greatest shock has been in France, a country where many ofCambodia’s new rulers learned their Marx and where worship ofrevolution has for years been something of a national obsession amongthe intelligentsia. Said New Philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy, a formerleftist who has turned against Marxism: “We thought of revolution inits purest form as an angel. The Cambodian revolution was as pure as anangel, but it was barbarous. The question we ask ourselves now is, canrevolution be anything but barbarous?”

Lévy has clearly pointed out the abyss to which worship of revolutionleads. Nonetheless, many Western European intellectuals are stillreluctant to face the issue squarely. If the word “pure,” when used byadherents of revolution, in effect means “barbarous,” perhaps the bestthe world can hope for in its future political upheavals is arevolution that is as “corrupt” as possible. Such skewed values are,indeed, already rife in some quarters. During the 1960s, Mao’s CulturalRevolution in China was admired by many leftist intellectuals in theWest, because it was supposedly “pure”—particularly by contrast withthe bureaucratic stodginess of the Soviet Union. Yet that revolution,as the Chinese are now beginning to admit, grimly impoverished thecountry’s science, art, education and literature for a decade. Even theChinese advocates of “purity” during that time, Chiang Ch’ing and hercronies in the Gang of Four, turned out to have been as corrupt as thepeople in power they sought to replace. With less justification, thereare intellectuals in the West so committed to the twin Molochs of ourday—”liberation” and “revolution”—that they can actually defend whathas happened in Cambodia.

Where the insane reversal of values lies is in the belief that lotionslike “purity” or “corruption” can have any meaning outside an absolutesystem of values: one that is resistant to the tinkering at will bygovernments or revolutionary groups. The Cambodian revolution, in itsown degraded “purity,” has demonstrated what happens when the Marxiandenial of moral absolutes is taken with total seriousness by itsadherents. Pol Pot and his friends decide what good is, what bad is,and how many corpses must pile up before this rapacious demon of”purity” is appeased.

In the West today, there is a pervasive consent to the notion of moralrelativism, a reluctance to admit that absolute evil can and doesexist. This makes it especially difficult for some to accept the factthat the Cambodian experience is something far worse than arevolutionary aberration. Rather, it is the deadly logical consequenceof an atheistic, man-centered system of values, enforced by falliblehuman beings with total power, who believe, with Marx, that morality iswhatever the powerful define it to be and, with Mao, that power growsfrom gun barrels. By no coincidence the most humane Marxist societiesin Europe today are those that, like Poland or Hungary, permit thedilution of their doctrine by what Solzhenitsyn has called “the greatreserves of mercy and sacrifice” from a Christian tradition. Yet ifthere is any doubt about what the focus of the purest of revolutionaryvalues is, consider the first three lines of the national anthem ofDemocratic Kampuchea:

The red, red blood splatters the cities and plains of theCambodian fatherland,

The sublime blood of the workers and peasants, The blood ofrevolutionary combatants of both sexes.

— David Aikman

Currently stationed in West Berlin as TIME’S Eastern Europeanbureau chief, Aikman was the magazine’s last staff correspondent toleave Cambodia, a few days before Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge.

Your browser is out of date. Please update your browser at http://update.microsoft.com

- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Why Publish with HGS?

- Advance Articles

- About Holocaust and Genocide Studies

- About the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- Was There a Genocide?

- An “Enlightened” Polity?

- Samir Amin, Malcolm Caldwell, and the “New Way for the Oppressed”

- Noam Chomsky and “Atrocity Propaganda”

- Enter the Conservatives

- The Scholarly Debate

- Political Interest and the Truth

- < Previous

Arguing about Cambodia: Genocide and Political Interest

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Donald W. Beachler, Arguing about Cambodia: Genocide and Political Interest, Holocaust and Genocide Studies , Volume 23, Issue 2, Fall 2009, Pages 214–238, https://doi.org/10.1093/hgs/dcp034

- Permissions Icon Permissions

From the time the Khmer Rouge seized power in April 1975, people have argued over the actions and intentions of the communist regime in Cambodia. During the years following the revolution, scholars and journalists debated allegations that the Khmer Rouge was committing genocide. Even after communist Vietnam toppled the neighboring regime, debate remained fierce. Much of the positioning by academics, publicists, and politicians seems to have been motivated largely by political purposes.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1476-7937

- Print ISSN 8756-6583

- Copyright © 2024 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Lessons from the Cambodia Genocide

Speech delivered by Professor the Hon Gareth Evans, Former Foreign Minister of Australia, to a Virtual Public Lecture Event, “The 45th Anniversary of Khmer Rouge Victory: What Lessons Could Cambodia Share?,” co-hosted by the Cambodia Institute for Cooperation and Peace and Asia-Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, 28 July 2020.

Cambodia stands almost alone in the modern era for the scale and intensity of the suffering its people have endured, above all during Pol Pot’s unbelievably brutal three-year genocidal reign of terror, which began 45 years ago, in 1975, and resulted in the direct killing of hundreds of thousands of Cambodians, and the deaths from malnutrition and disease of many hundreds of thousands more, producing an overall death toll of up to 2 million men, women and children. But before the Khmer Rouge victory, and very much contributing to it, the country was ravaged by massive United States bombing during the Vietnam war; and after Pol Pot was driven out of Phnom Penh by the Vietnamese invasion in 1978, Cambodia was ravaged further by prolonged civil war, which ended only thirteen years later with the Paris Accords and UN transitional presence. And even with the coming of peace in 1993, the country – unhappily – has not been immune from tension, bitterness, major human rights violations and political violence continuing to the present day.

It is right that we continue to focus, on occasions like this, on the events of the mid-1970s and the lessons to be drawn from them. It is right because the horror that Cambodia experienced then, whether or not it be strictly legally definable as “genocide” within the meaning of the Genocide Convention, remains – along with Rwanda and Bosnia in the 1990s – the talismanic Post-World War II case globally of conscience-shocking group violence, be it driven by race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, class, politics or ideology. And for all the progress that has been made in recent years, as an international community we are still, as the events in Syria, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and elsewhere in recent years graphically demonstrate, falling a long way short of being able to confidently say, when it comes to genocide and other mass atrocity crimes, “Never Again.”

In these relatively brief remarks, there are five specific lessons that I want to draw from Cambodia’s experience: don’t assume any country is immune from genocidal violence; don’t assume the world will help; diplomacy can nonetheless make a difference; don’t assume it’s over when it’s over; and don’t give up on the principle of “the responsibility to protect” – R2P – and the hope provided by its unanimous embrace by the UN General Assembly fifteen years ago, in 2005.

Don’t assume any country is immune from genocidal violence

I remember vividly the atmosphere when I first visited Cambodia in 1968, spending a week drinking beer and eating noodles in student hangouts around Phnom Penh, and careering up and down the dusty road to Siem Reap and Angkor Wat in cheap share-taxis, scattering chickens, pigs and children along the way. The country was tranquil, almost then untouched by the war next door in Vietnam, with the massive US carpet bombing still a year away. What happened in Cambodia in the mid-1970s was, before it happened, unimaginable.

But so too was Hitler’s Holocaust utterly unimaginable before it happened – the cold blooded murder of millions of Jews, Gypsies, Slavs, gays and other non-Aryans, not because of anything they did but for what they could not help being – in the land of Goethe, Schiller, Beethoven, Mahler, Weber and many more contributors to some of the great core achievements of Western civilization. The potential for genocidal violence is not confined to fragile developing countries: in an age of authoritarian populism and crude identity politics – think Erdogan, Orban, Bolsonaro, even Trump’s America – the potentially deadly virus of group hatred can emerge almost anywhere in the world.

The truth is – as I well know from years of wrestling with the problem of conflict prevention and early warning when I headed the International Crisis Group – that there is no real science to determining which societies will explode in orgies of deadly conflict and genocidal violence and those which won’t. Relevant factors include historical grievances and enmities; rapid economic, social or political dislocation; arrogant elites prospering amid poverty; poor governance and leadership generally; poor education systems doing nothing to defuse prejudice; and externally generated destabilization (as with the impact of the US bombing campaign in Cambodia, which gave the Khmer Rouge, previously a marginalized guerilla group, a cause and momentum). But there are no one-size fits-all explanations: it’s often the case that countries with similar histories, cultures, and demographics and experiencing similar internal and external pressures, will respond very differently.

Recognizing the myriad of short-term factors – overlaying longer term structural factors – that will influence which way a society will jump, effective conflict and crisis prevention really comes down to avoiding it-can’t-happen-here type complacency; closely monitoring current developments (with the emergence of prevalent hate-speech being an important indicator of the potential for atrocity crimes); being aware of the available toolbox of preventive measures (political and diplomatic, economic and social, legal and constitutional, and security-sector related); and taking whatever remedial action is possible – both internally and externally – before things get out of hand. It’s not clear that any of this would have prevented the Khmer Rouge victory in Cambodia in 1975, but it is the kind of approach which has helped Burundi stop falling into the volcano over the last two decades despite a profile almost identical to its neighbor Rwanda in the mid-1990s.

Don’t assume world help

What was happening in Cambodia in 1975 was known soon enough to the rest of the world – not least as a result of some brave journalists getting the story out from Phnom Penh – but the reaction was overwhelmingly one of stunning indifference. Partly, and this was certainly the case for the Western political leaderships of the time, it was a matter of cynical self-interest, one of the most extreme manifestations of which that has made its way on to the public record being then US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s observation to Thai Foreign Minister Chatichai seven months after the Khmer Rouge had marched into Phnom Penh: “Tell the Cambodians that we will be friends with them. They are murderous thugs, but we won’t let that stand in our way.” The whole situation was looked at through a Cold War prism, so much so that when Vietnam’s 1978 invasion did stop the Khmer Rouge mass murder in its tracks, it was not applauded by anyone except the Soviet Union.

The almost universal response, not only in the West but throughout the developing world, was that this was an unacceptable violation of state sovereignty. The notion that sovereignty might yield to a larger responsibility to protect those at risk of genocidal violence – to what Kofi Annan was later to describe as “gross and systematic violations of human rights that offend every precept of our common humanity” – had not yet taken any widespread root. It was particularly contested in the global South, where so many countries were so proud of their recently won sovereign independence, so conscious in many cases of their fragility, and so unwilling to concede that any of their former imperial masters could, even in the case of extreme human rights violations, have any kind of “right of humanitarian intervention” within their borders.

Despite the formal global acceptance since 2005 of R2P, which I will come back to below, the unhappy reality remains to this day that if preventive efforts are non-existent or fail, and genocidal violence does erupt, the international will to take strong measures – including, in the last resort. Security Council endorsed military intervention – is in the current international environment almost as non-existent as it was in 1975. Everything really does depend on effective prevention, and a great deal of that is going to have to come from brave internal actors willing to push back against authoritarian overreach. Few things matter more in protecting human rights than strong civil society organisations, and it is gratifying to see in Cambodia how many decent individuals – many of whose voices are heard in Sue Coffey’s excellent edited collection, Seeking Justice in Cambodia: Human Rights Defenders Speak Out (MUP, 2018) – continue to work bravely and tenaciously in an extremely difficult and often extremely hostile political environment, to achieve just that.

Diplomacy can make a difference

The Khmer Rouge threat did not disappear with the Vietnamese invasion: supported by China, it remained a significant force in the provinces, and large-scale civil war continued to take its toll of Cambodians in terms of death, injury, displacement into cross-border refugee camps, general immiseration and loss of life opportunity. The situation was not helped by the multiplicity of actors who had different stakes in the outcome. Internally there were four warring factions – with Hun Sen’s Government waged against a fragile coalition of the non-communist Sihanoukists and Son Sann’s KPNLF with the communist Khmer Rouge under Pol Pot, and each group immensely distrustful of all the others; regionally, Vietnam supported Hun Sen and the six ASEAN members of the time supported his opponents; and, at the great power level, China supported the Khmer Rouge and Prince Sihanouk (as he then was); the Soviet Union supported Hun Sen; and the United States supported the two non-communist resistance groups.

Untangling all this was a formidably complex and protracted diplomatic process, but one that did eventually bring peace. The key to the successful UN peace plan, which I am proud to say that Australia played a central part in forging, was to find a face-saving way for China to withdraw its political and financial support from the Khmer Rouge, which denied that support would either at best immediately collapse or at worst over time wither and die on the vine. The crucial diplomatic agreement was to give an unprecedentedly central role to the United Nations, not just in peacekeeping or electoral monitoring, but in the actual governance of the country during the transitional period. This did give China the cover it needed to disengage from the Khmer Rouge, which did then effectively collapse as an effective force, making a return to peace at last possible.

Peace-making diplomacy will not always be as successful as it was in Cambodia from 1989-91, with the actors who had contributed so much to the problem cooperating effectively to produce a solution, or – to take another example – Kenya after the December 2007, when catastrophically escalating ethnic-based violence was defused by an African Union and UN supported mission led by Kofi Annan negotiating a power sharing cabinet and setting in train ongoing negotiations on underlying root cause issues.

But such diplomacy will always be worth pursuing, as will earlier stage preventive diplomacy involving measures like fact-finding missions, friends groups, eminent persons commissions, conciliation and mediation, and support for non-official second-track dialogue. The difficulty is always to move from rhetoric to effective action: talk is cheap, and there has for many years been endless amounts of it in and around the UN system about the critical importance of prevention, through diplomacy, development assistance and other strategies. But willingness to make the necessary commitment of time and resources has always been in short supply, and shorter still in the present international environment

It may not be over when it’s over

Peacemaking, if it is to be genuinely successful and sustainable, has to be accompanied by effective post-conflict peacebuilding. The end of the Khmer Rouge genocide and the final destruction of its warfighting capability did bring an end to much of Cambodia’s misery, but not all of it. At the signing of the Paris Peace Agreements in 1991, I said in my statement as Australian Foreign Minister that “Peace and Freedom are not prizes which, once gained, can never be lost. They must be won again each day. Their foundations must be sunk deep into the bedrock of political stability, economic prosperity and above all, the observance of human rights.” Sadly, since 1993, the truth of that observation has been borne out over and again.

A foretaste of things to come came with Hun Sen’s refusal to accept his defeat at the UN supervised election in 1993, insisting on a power-sharing arrangement which the international community did not resist, as in retrospect we certainly should have. Since then there has been systematic suppression of any movement towards a mature democracy, with repression of free speech and assembly, the arrest of many human rights activists who have tried to speak out for fundamental freedoms, and the thwarting of every attempt to have a genuinely free election, with periodic resort to murderous violence. In recent months, the Covid-19 pandemic has been used as cover for the passage of further draconian legislation by a parliament from which opposition members have been excluded, further suppressing freedom of speech and assembly, allowing control of technology by any means necessary, and providing for long jail terms and property confiscation.

History teaches us that perhaps the best single indicator of future conflict, within or between countries, is a record of past conflict. Among the countries most at risk of genocidal violence are those that have been there before. Cambodia is a country demanding constant vigilance, both from its own citizenry and from the international community, if it is to meet the hopes and aspirations – not only for peace, but democracy and human rights – of all those who fought so hard to free it from the yoke of Khmer Rouge tyranny. That task was not completed with the UN peace process three decades ago: it remains work in progress.

Don’t give up on R2P

If we are to end once and for all the occurrence or recurrence of genocide and other mass atrocity crimes happening within sovereign state borders anywhere in the world, it is crucial that the international community seriously commit itself to the effective practical implementation of all the “the responsibility to protect” principles which heads of state and government unanimously endorsed at the 2005 World Summit, finally recognizing how indefensible their failure to act had been in Cambodia, Rwanda, Srebrenica and elsewhere.

It is not just a matter of states recognizing their own responsibility not to perpetrate or allow mass atrocity crimes within their own borders, and to assist other states to so act through aid and other support; it’s also a matter of states taking timely and decisive action to halt such crimes – including in extreme cases through UN Security Council endorsed military intervention – if a state has manifestly failed to do so. The present reality is that, particularly when it comes to that more robust third pillar, R2P remains at best work in progress.

As a normative principle – that mass atrocity crimes perpetrated behind sovereign state borders are not just that state’s but the world’s business – its acceptance, as evidenced by annual General Assembly debates and scores of Security Council resolutions, is almost complete. As an effective preventive force, and as a catalyst for institutional change, it has had many identifiable successes. But as an effective reactive mechanism, when prevention has failed, the record – since the Libyan case ran off the rails in 2011 – has been manifestly poor, above all in Syria. In the present international environment – with China and Russia now behaving as they are – it will be a long and difficult process to recreate any kind of Security Council consensus as to how to react to the hardest of cases.

A lot depends in this respect on the willingness of the United States, United Kingdom and France to acknowledge that they, more than anyone else, were responsible for the breakdown of that consensus by their actions in Libya in 2011 – not by their missteps after Gaddafi was overthrown, which they frankly acknowledge, but their refusal to accept that the military intervention mandate agreed by Security Council, in the face of an imminent massacre in Benghazi, was for limited civilian protection purposes, and did not extend to open-ended warfighting designed to achieve regime change. If Trump is re-elected in the US, we can wave goodbye for the foreseeable future – with R2P as with just about everything else in the multilateral system – to any prospect of effective international consensus on these great value issues. But if he is thrown out in November decency has a chance.

Learning the biggest lesson of all from the Cambodian genocide – the need to make R2P genuinely effective – means above all mobilizing the political will to make something actually happen when it must. For that to happen many arguments need to be effectively made to many different constituencies. But the most compelling argument – the one that spurred world leaders to accept the R2P norm in principle in 2005, and which will continue to be crucial in ensuring its practical implementation – remains the moral one, based simply on our common humanity: our duty to rise above the legacy of all those terrible failures in the past, and ensure that never again do any of us stand by, or pass by, in the face of mass atrocity crimes.

Related Content

Atrocity Alert No. 389: Genocide Prevention and Awareness Month, Myanmar (Burma) and North Korea

Atrocity Alert No. 388: Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory, South Sudan and Nicaragua

The World Must Stand Up for the Rohingya - Lest We Forget!

Get involved.

Sign up for our newsletter and stay up to date on R2P news and alerts

Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies The Graduate Center, CUNY 365 Fifth Avenue, Suite 5203 New York, NY 10016-4309, USA

- What Caused the Cambodian Genocide?

The Cambodian genocide was the mass killing of people who were perceived to oppose the Khmer Rouge regime led by Pol Pot . The genocide resulted in the death of between an estimated 1.5 and 3 million people between 1975 and 1979. The regime intended to turn Cambodia into a socialist republic with agriculture as the core economic activity. After successfully overthrowing the government, the Khmer Rouge changed the country’s name from Cambodia to Democratic Kampuchea. Millions of people were forced from the cities into labor camps in rural settlements to work on rice fields. Any person who opposed the regime including the rich, monks and religious leaders were tortured and killed.

Precursors To The Genocide

The Khmer Rouge, formally known as the Communist Party of Kampuchea, was formed during the struggle for independence against the French. By 1968 the movement evolved into a political party. In March 1970, an American backed coup outed the then-head of state King Sihanouk and appointed the Prime Minister Lon Nol as the head of state. Sihanouk allied with the Khmer Rouge, setting the stage for a genocide. At the time, the US was bombing Viet Cong positions in Cambodia, killing thousands of Cambodians in the process. Millions of peasant farmers loyal to the Khmer Rouge were armed by the Chinese government and by April 17, 1975, they took control of the capital city and overthrew the government of Cambodia. The city was considered economically invaluable and thousands of people were forced into labor camps in the villages. Starvation, physical abuse, exhaustion, diseases, became prevalent in the countryside.

Genocide Begins

The Khmer Rouge was extremely brutal in the way it handled the masses. The educated lot consisting of teachers, doctors, artists, monks, religious leaders, and those who worked in government facilities were singled out as a potential threat to the regime and eliminated. Those in opposition were ambushed and killed alongside those who could not work. Once a family member was killed, other family members were targeted to prevent them from seeking revenge. There was no immunity in the conflict, unlike other genocides. Even those on the Khmer Rouge side were eliminated once they were suspected of not being loyal enough. Children were killed under a notion that stated “to permanently disable the weed you pull out the roots. “Several facilities such as schools, medical facilities, and churches were closed down. Child soldiers became part of the Khmer Rouge army.

International Response

The international community remained silent on the ongoing atrocities in Cambodia. Neither Europe nor the US took interest in what was happening despite the frantic efforts by the western media to raise concerns. The United States had suffered heavy casualties in the Vietnam War and was in no position to engage in another conflict.

The End Of The Genocide

In 1977, clashes between Cambodia and Vietnam began. Two years later, Vietnam forced its way into Cambodia and overthrew the government which was comprised of the defectors of the Khmer Rouge. Other members fled to Thailand where they occasionally attacked Vietnam. For the next decade, the ousted members tried to overthrow the Vietnamese-backed regime with the aid of the Soviet Union and China. Vietnam withdrew from Cambodia in 1989 after the US placed economic sanctions on the occupied state while the Soviet Union withdrew its financial aid. In 1991, a coalition came to power. Two years later former head of state Norodom Sihanouk was elected as the president.

More in Society

Countries With Zero Income Tax For Digital Nomads

The World's 10 Most Overcrowded Prison Systems

Manichaeism: The Religion that Went Extinct

The Philosophical Approach to Skepticism

How Philsophy Can Help With Your Life

3 Interesting Philosophical Questions About Time

What Is The Antinatalism Movement?

The Controversial Philosophy Of Hannah Arendt

Home — Essay Samples — Science — Noam Chomsky — A Study of Chomsky’s Writings on The Cambodian Genocide

A Study of Chomsky’s Writings on The Cambodian Genocide

- Categories: 20Th Century Genocide Noam Chomsky

About this sample

Words: 825 |

Published: May 24, 2022

Words: 825 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: History Science

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

5 pages / 2172 words

2 pages / 1054 words

3 pages / 1142 words

1 pages / 373 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Noam Chomsky

Overview of the debate about language acquisition throughout history Mention of the four modern theorists and their respective theories Explanation of each theorist's perspective on language acquisition B.F. [...]

Genie was strapped to a potty chair and neglected by her father. Her father kept her and her mother in a 'protective custody' where they were 'virtual prisoners' to his gross interpretation of a habitable and nurturing [...]

Noam Chomsky, the renowned linguist, activist, and author, has long been a source of inspiration and admiration for me. His multifaceted contributions across diverse fields, including linguistics, psychology, and politics, have [...]

In The Descent of Man, Darwin starts off comparing the bodily structures of humans and animals and discovering that there are many similarities in structures like bones, muscles, and even the brain. To prove this point, he [...]

The idea of what constitutes legitimate scientific proof is one that is subjective and varies from one circumstance to another, but compiling various types of evidence to support a claim has long been an accepted, respected, and [...]

It was 1627 when Sir Francis Bacon published his utopic treatise New Atlantis and Europe was polluted by religious tension, much of which revolving around the recent surge of science but some having existed since long [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Cambodian genocide, systematic murder of up to three million people in Cambodia from 1976 to 1978 that was carried out by the Khmer Rouge government under Pol Pot.. Immediately after World War II, the Americans and the French fought wars against communism in Korea and Vietnam, respectively.Cambodia became independent in 1953 when French Indochina collapsed under the assault of Ho Chi Minh's ...

The Cambodian genocide was the systematic persecution and killing of Cambodian citizens by the Khmer Rouge under the leadership of Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea, Pol Pot. It resulted in the deaths of 1.5 to 2 million people from 1975 to 1979, nearly 25% of Cambodia's population in 1975 (c. 7.8 million).

Cambodia 1975-1979. An exhumed mass grave in Cambodia yields skeletons of the executed. October 10, 1981. —David Allen Harvey/National Geographic Creative. "To keep you is no gain; to lose you is no loss.". From April 17, 1975, to January 7, 1979, the Khmer Rouge perpetrated one of the greatest crimes of the 20th century.

Raymond PIAT/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images. The Khmer Rouge was a brutal regime that ruled Cambodia, under the leadership of Marxist dictator Pol Pot, from 1975 to 1979. Pol Pot's attempts to ...

Ben Kiernan, in "The Cambodian Genocide, 1975-1979", provides a detailed account of the Pol Pot regime's systematic attempt to exterminate ethnic, religious, and cultural minorities from Cambodia. The essay is divided into three sections. The first is a facts-based retelling of the Khmer Rouge's genocidal campaign in the late 1970s ...

On the morning of April 17, 1975, advance units of Cambodia's Communistinsurgents, who had been actively fighting the defeated Western-backedgovernment of Marshal Lon Nol for nearly five years ...

The Cambodian Genocide Essay. The Cambodian Genocide took place from 1975 to 1979 in the Southeastern Asian country of Cambodia. The genocide was a brutal massacre that killed 1.4 to 2.2 million people, about 21% of Cambodia's population. This essay, will discuss the history of the Cambodian genocide, specifically, what happened, the victims ...

Abstract. This photo essay takes the reader on a visual journey through two Cambodian memorial sites 40 years later. Shortly after the United States withdrew from its war in neighboring Vietnam, Cambodia descended into genocide. Intent on using violence to create an agrarian utopia, Pol Pot and his communist Khmer Rouge cadre forcibly displaced ...

The establishment of the Cambodia Genocide Program (CGP) at Yale University facilitated new scholarly research. In April 1994, Congress passed the Cambodian Genocide Justice Act, committing the American government to pursuing justice for victims of the genocide. In December 1994, the State Department awarded $499,000 to the Yale project.

The end of the Khmer Rouge genocide and the final destruction of its warfighting capability did bring an end to much of Cambodia's misery, but not all of it. At the signing of the Paris Peace Agreements in 1991, I said in my statement as Australian Foreign Minister that "Peace and Freedom are not prizes which, once gained, can never be lost

Genocide In Cambodia Essay. 1237 Words5 Pages. The Cambodian Genocide is considered to be one of the worst human tragedies in the last century. The Genocide in Cambodia should be more recognized around the world for its severity and intensity. Khmer Rouge, a communist group led by Pol Pot, seized control of the Cambodian government from Lon Nol ...

The Cambodian genocide was the mass killing of people who were perceived to oppose the Khmer Rouge regime led by Pol Pot. The genocide resulted in the death of between an estimated 1.5 and 3 million people between 1975 and 1979. The regime intended to turn Cambodia into a socialist republic with agriculture as the core economic activity.

The Cambodian Genocide took place from 1975 to 1979 in the Southeastern Asian country of Cambodia. The genocide was a brutal massacre that killed 1.4 to 2.2 million people, about 21% of Cambodia's population. This essay, will discuss the history of the Cambodian genocide, specifically, what happened, the victims and the perpetrators and the ...

The Cambodian Genocide was the result of imperialism, ethnic supremacy, ultra-nationalism, anti-colonialism, a power grab, and religion. It began with the Cambodian people struggling against French colonization and grew in inspiration from Vietnam (end genocide). The French believed that Cambodia was a gateway into China to expand their trade ...

Cambodian Genocide Essay 750 Words | 3 Pages. The True Impact of the Cambodian Genocide The Cambodian Genocide was a tragic event that took place in 1975 and lasted until about 1979. The genocide was led by Pol Pot and the communist party Kampuchea, also knowns as the Khmer Rouge. Millions of people were killed during this catastrophe.

The Cambodian Genocide occurred from 1975 to 1979. This genocide was executed by the Khmer Rouge which was lead by Pol Pot. According to the article "Pol Pot", in 1953 a man named Saloth Sar entered a communist group under the fictitious name of Pol Pot and he took the role of a leader for this group in 1962.

A Study of Chomsky's Writings on The Cambodian Genocide. The quest for justice within Cambodia as a response to the Khmer Rouge's atrocities from 1975 to 1979 has encountered continuous political debate and manoeuvring. With the opening of the Khmer Rouge Tribunal in 2003, it has clearly illustrated the challenges and complexities involved ...

The Cambodian Genocide Essay. The Cambodian Genocide has the historical context of the Vietnam War and the country's own civil war. During the Vietnam War, leading up to the conflicts that would contribute to the genocide, Cambodia was used as a U.S. battleground for the Vietnam War. Cambodia would become a battle ground for American troops ...

The Cambodian Genocide happened in 1975 when the Cambodian government was taken over by the Khmer Rouge. Millions of people were killed and evacuated to labor camps where they were abused and starved to death. Even though all of this was happening in Cambodia, no other countries came to help take back the government.

Cambodian Genocide Essay. 4 February, 2016 The Cambodian Genocide The genocides of Cambodia and the Holocaust were two major genocides that have changed the history of the world forever. The Cambodian genocide started when the Khmer Rouge attempted to nationalize and centralize the peasant farming society of Cambodia (Quinn 63).

In reality, this is how life was for many Cambodians during the reign of Pol Pot between 1975 and 1979. This event, known to many as the Cambodian genocide, left a profound mark on the world around us. In the late 70's, nearly 2 million Cambodians died of overwork, starvation, torture, and execution in what became known as the Cambodian genocide.

Essay On Cambodian Genocide. The Cambodian Genocide The Cambodian genocide lasted from 1975-1979 and killed "approximately 1.7 million people" (Kiernan). The Cambodian genocide was run by the "Khmer Rouge regime headed by Pol Pot combined extremist ideology with ethnic animosity and a diabolical disregard for human life to produce ...

Cambodian Genocide Essay. 1084 Words 5 Pages. Research project and presentation write up: Genocides in the 1970s For this project I worked with Madison Latonie to cover the genocides of the 1970s, including the Bangladesh genocide, the Cambodian genocide, and the East Timor genocide. Of these, I was responsible for completing the section on the ...