Counseling Resource Navigation Support Groups Education Financial Assistance

Copelink blog.

Latest news, stories and updates from our blog.

Columbia School of Social Work, Cancer Care and University of Washington School of Social Work Introduce the Handbook of Oncology Social Work

Columbia School of Social Work, Cancer Care and University of Washington School of Social Work applaud the publication of the “ Handbook of Oncology Social Work: Psychosocial Care for People with Cancer ,” published by Oxford University Press.

The development of this inaugural Handbook of Oncology Social Work provides an up-to-date repository of the scope of oncology social workers’ clinical practice, education, research, policy, and program leadership in the psychosocial care of people with cancer and their families. It addresses both the science and art of psychosocial care and identifies the increasing specialization of oncology social work related to its unique knowledge base, skills, role and the progressive complexity of psychosocial challenges for patients with cancer.

The Handbook ’s editors are Grace Christ, DSW/PhD, Professor Emerita, Research Scientist, Columbia School of Social Work; Carolyn Messner, DSW, OSW-C, LCSW-R, Director of Education and Training, Cancer Care ; and Lynn Behar, PhD, LICSW, OSW-C, and Founder, Carol LaMare Program for Oncology and Palliative Social Work, University of Washington School of Social Work.

The “ Handbook of Oncology Social Work: Psychosocial Care for People with Cancer ” includes 109 chapters by 160 authors and is available now for order.

Advance Praise of the Handbook of Oncology Social Work

“This long-awaited volume written by pioneers in the field, provides a wealth of evidence-based information on how to deliver cancer care for the whole person ... a must read for anyone practicing in oncology.”

-- Julia H. Rowland, PhD, Director, Office of Cancer Survivorship, National Cancer Institute, NIH/DHHS

About Columbia School of Social Work Columbia School of Social Work has been a leader in social work education and research since 1898. It joins rigorous academic theory with real-world practice to enhance the welfare of citizens and communities in New York City, the nation and around the world. To learn more, visit www.socialwork.columbia.edu .

About Cancer Care ® Founded in 1944, Cancer Care is the leading national organization providing free, professional support services and information to help people manage the emotional, practical and financial challenges of cancer. Our comprehensive services include counseling and support groups over the phone, online and in-person, educational workshops, publications and financial and co-payment assistance. All Cancer Care services are provided by oncology social workers and world-leading cancer experts. Headquartered in New York, NY, Cancer Care maintains three additional locations in Norwalk, CT, Ridgewood, NJ and Syosset, NY. To learn more, visit www.cancercare.org or call 800-813-HOPE (4673).

About University of Washington School of Social Work Founded in 1934, and celebrating 80 years of impact, the University of Washington School of Social Work is a recognized leader in solving the most demanding social issues of our day through rigorous research, academic innovation and public service. Visit www.socialwork.uw.edu to learn more.

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy

By using our website, you agree to our recently updated Privacy Policy . Here you can read more about our use of cookies which help us make continuous improvements to our website. Privacy Policy .

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Addictions and Substance Use

- Administration and Management

- Aging and Older Adults

- Biographies

- Children and Adolescents

- Clinical and Direct Practice

- Couples and Families

- Criminal Justice

- Disabilities

- Ethics and Values

- Gender and Sexuality

- Health Care and Illness

- Human Behavior

- International and Global Issues

- Macro Practice

- Mental and Behavioral Health

- Policy and Advocacy

- Populations and Practice Settings

- Race, Ethnicity, and Culture

- Religion and Spirituality

- Research and Evidence-Based Practice

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Work Profession

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Oncology social work research.

- Julianne S. Oktay Julianne S. Oktay University of Maryland Baltimore

- and Bradley Zebrack Bradley Zebrack University of Michigan

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.1268

- Published online: 25 June 2018

Oncology social work researchers have made (and continue to make) important contributions to the knowledge base that supports the profession. This article discusses the profession of oncology social work, its roots in medical social work in the United States, the development of cancer treatment, and the body of research that informs its art and practice. Oncology social work research is placed in the broader contexts of the social work profession, the field of oncology, and the specific field of oncology social work.

Through the decades, the profession of oncology social work has grown, gained stability and legitimacy. Oncology social work itself, along with oncology social work research, have made rapid strides in the 21st century and accelerating in impact and relevance. Oncology social work research is stronger now than ever. Recent developments, such as the addition of a research institute at the annual AOSW conference and initiatives to establish a “practice-based research network” are expanding capacity in the field.

Oncology social work researchers bring a unique perspective to their research. Social work’s patient-centered perspective is reflected in research that explores the cancer experience of patients and family members and leads to new interventions based on that experience. Social work’s focus on human development over the life course results in research that reflects a developmental framework or focuses on specific age groups, such as children, adolescents, young adults, or the elderly. Social work’s conceptual model of “Person-in-Environment” is reflected in research on cancer patients in the context of their interpersonal relationships. The values of social justice and cultural competence are reflected in research on health disparities, minority populations, and multicultural perspectives. Finally, the field of oncology social work itself has been the focus of recent research on distress screening and its implementation.

In the 21st century, oncology social work research stands in a pivotal position. Although this type of research is now widely recognized as important, it is still a challenge to access the level of support from major funders of cancer research required to establish and reinforce a strong and vibrant knowledge base for the profession.

- Psychosocial oncology

- Social work

- cancer and oncology social work

Oncology social workers have long served as front-line advocates for the “whole patient,” incorporating psychosocial care into the treatment of patients with cancer and promoting patient- and family-centered care (Hedlund, 2015 ). Several recent developments (discussed later in the article) highlight the importance of social work in quality cancer care. Like all professions, social work relies on empirical research findings to inform psychosocial practice and generate new knowledge. Both oncology social work itself and the research associated with this discipline have made rapid strides in recent years and are on the verge of critical acceleration in terms of its impact and relevance.

This article provides background on the profession of oncology social work, its roots in US medical social work, on cancer treatment, and on the body of research that informs its art and practice. We begin by placing oncology social work research in the broader contexts of (1) the social work profession, (2) the field of oncology, and (3) the specific field of oncology social work.

The Development of the Social Work Profession

The social work profession is rooted in the progressive movement of the early part of the 20th century . Accomplishments from that period included labor laws (especially child labor laws), the integration of large immigrant populations into American society (e.g., settlement houses), voting rights for women, and the building of a basic social network to protect and support vulnerable populations (e.g., the sick, disabled, aged, mentally ill, and children). In the health-care field, pioneers Ida Cannon and Harriett Bartlett at Massachusetts General Hospital and Johns Hopkins Hospital, respectively, developed the first hospital social work departments (Bartlett, 1957 ; Cannon, 1913 ; Gehlert, 2006 ; Fobair et al., 2009 ; Kiegher, 2000 ), while others worked in a variety of public health efforts (e.g., fighting TB, sanitation). The first school of social work was established at Simmons College in 1904 , in part to train social workers to work at Massachusetts General (Simmons, 2016 ). The focus of early health social work was on assisting poor immigrants from Europe struggling with infectious diseases and other maladies attributable to their physical and social environments. As public health advanced, a number of successful programs (vaccination, pubic sanitation, clean water, pasteurization of milk) and the development of antibiotics eliminated many of these health issues; social workers then began to focus on persons struggling with serious chronic and life-threatening conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

By the 1950s, medical social work was a well-established specialty, with its own organization, textbooks, and journal. However, in the mid-1950s, medical social work (and other specialty groups) was absorbed into the new National Association of Social Workers with a broader and more unified vision of the social work profession that emphasized what all social workers have in common, rather than on the skills they had developed in specialty niches. Out of this period came a strong common ideology emphasizing professional ethics, a commitment to social justice, and a strong belief in the importance of professional training and research. Schools of social work grew, as did the importance of the master’s in social work degree and of research. By the mid-1960s, federal dollars became available to fund scholarships for students (NIMH) and to support faculty research in areas of national interest (poverty, health and aging, civil rights/integration).

The creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 led to increased numbers of medical social workers, and once again, knowledge in this field expanded. Two journals in medical social work were established in 1975 , Social Work and Health Care and Health and Social Work , and important textbooks in the field were published (Bracht, 1978 ).

Research in the Social Work Profession

Although many of the very early social work pioneers, such as Jane Addams and Ann Abbott, were involved in research (Zimbalist, 1977 ), research in the social work field did not begin to grow rapidly until the 1950s. Even then, the practice side of the profession expanded much more rapidly, while research activities grew at a much slower pace. New schools of social work strongly emphasized practice, with limited attention to research. Doctoral programs in social work also expanded in the 1960s; however, many of these programs offered a practice-focused doctorate (DSW), instead of the more research-focused PhD. Concerned, the Russell Sage Foundation initiated funding opportunities to encourage and expand research efforts in social work (Austin, 1991 ), and among these was a new doctoral program at the University of Michigan. Despite the emergence of some excellent doctoral programs, by 1988 a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) task force declared research in social work to be in crisis. “A sustained and credible program of research is … essential to a profession’s self-respect and to its ability to maintain the positive regard of outsiders whose opinions help support and legitimize the profession’s endeavors (Fanshel, quoted in Austin, 1991 ). They pointed out that research resources in social work had “lagged far behind” the practice aspect of the profession and concluded that social work research “has failed to meet the needs of practitioners.” Also, although new doctoral programs had proliferated, the number of graduates granted doctoral degrees did not increase; and, according to this NIMH report, the quality of research produced by those with social work doctorates was not comparable to that of graduates from other disciplines and professions. The task force identified several major factors limiting a scientific knowledge base in social work, including a lack of strong, research-based doctoral programs, lack of support for social work research at the national level, and a lack of integration of research into practice forums (Austin, 1991 ). The task force recommended increased attention to research in social work education. Research training in many social work doctoral programs was strengthened as a result of the report. Also, a new forum for social work research was established in 1993 , the Society for Social Work Research (SSWR), with its own research journal, the Journal of the Society for Social Work Research (JSSWR).

Also created at the same time was the Institute for the Advancement of Social Work Research (IASWR), designed to strengthen the infrastructure in social work research and to enhance the connections between social work research and practice, education, and policy (Zlotnik, Biegel, & Solt, 2002 ; Zlotnik, & Solt, 2006 , 2008 ). IASWR was funded jointly by major social work organizations such as the NASW, CSWE, and leadership in bachelors and doctoral social work education.

To fully understand social work in oncology, and the role social workers play in the delivery of cancer care, it is helpful to understand the nature of the medical treatment of cancer and how it developed.

The Development of the Field of Oncology

Until the development of effective treatments, cancer was almost always fatal. In the absence of screening and early detection, surgery was often the only treatment. Cancers were not typically discovered until they had grown quite large and patients became symptomatic: as a result, the cancer had already spread throughout the body. At that point, surgery was often ineffective, or it was so extensive that it was deforming (e.g., radical mastectomy). In the earlier days of cancer treatment, it was common practice not to tell patients they had cancer. Often obscure terminology was used, or vague information was given about prognosis.

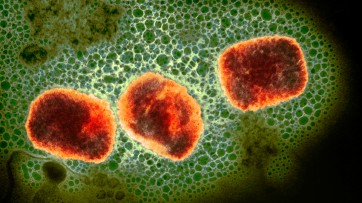

The introduction of surveillance (Seven Warning Signs program of the ACS), along with advances in treatment such as radiation and chemotherapy meant that more and more cancers were treated successfully. Patients began to live longer, and in some cases, cancers were cured. The first successes were with pediatric cancers, where dramatic increases in survival rates were observed through the 1970s and 1980s.

In breast cancer, the development of mammograms meant that small cancers could be found and treated before they spread (metastasized). In colon cancer, screening allowed polyps to be removed before they become malignant. This has reduced the rate of colon cancer deaths significantly. More recently, the recognition that cancer can arise from environmental or behavioral exposure to carcinogens has reduced the risks for these cancers in the population. The most significant was the connection made between smoking and lung (and other cancers). The long and ultimately successful campaign against smoking has led to a significant reduction in lung cancer and other cancer deaths. The recognition that skin cancers are often related to sun exposure has led to widespread use of sunscreens, and the FDA has recently recommended that tanning salons be off limits for teens.

The successes of early detection and prevention programs gradually led to a significant increase in the number of cancer survivors. A new organization, the National Coalition of Cancer Survivors, founded in 1986 by a group of cancer care providers and patient advocates, helped advance the notion that a cancer experience for patients and families is initiated at the time of diagnosis and contributes through phases of treatment—and, for many, a transition to off-treatment survival. The number of survivors has grown exponentially since then, with over 14 million survivors in the 21st century . In 1996 , partially in response to the political pressure from the cancer survivorship movement, the National Cancer Institute established the Office of Cancer Survivorship, with the primary aim of establishing and advancing a research agenda responsive to the issues and needs of cancer survivors.

There have also been important changes in the way cancer is understood. A national program to study the human genome bolstered our understanding that some cancers are genetically based. That is, vulnerability to some types of cancer can be inherited. This understanding meant that patients who are at higher risk could be identified and treated prophylactically. For example, women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation can now decide to have prophylactic mastectomies and/or oophorectomies to prevent the development of future cancer. However, the cancers caused by an inherited genetic mutation account for only a small proportion of all cancers. Many more mutations are now thought to be the result of environmental factors interacting with genetic characteristics. Of special interest to social workers is the understanding of “epigenetics,” the interactions occurring among human genes and the physical environment. That is, some cancer risks and associated disparities across demographic sub-groups defined by race, age, or gender can be explained by genomic changes arising from physically or emotionally stressful environments (Werner-Lin, 2015 ). Excess mortality rates for young women (particularly young African American women) with advanced-stage breast cancer may be another example of epigenetics explaining this disparity.

Another new development in cancer prevention is the recognition that screening can lead to over-treatment, especially in cancers that are often slow-growing and in populations (often older) that have high survival rates. Early screening in prostate and early stage breast cancers have become controversial (Brawley, 2017 ).

The most recent developments in cancer treatment include personalization of treatments based on unique characteristics of the individual tumor, and new forms of immunotherapy, also targeted to individual characteristics. Immunotherapy offers great promise for the future, but these treatments are currently so costly that they are often out-of-reach for all but the most wealthy or well-insured patients.

Improved treatments, better screening, and changing demographics are contributing to increases not only in the numbers of oncology patients and survivors but also to changes in the way that patients and their families experience cancer and its treatments, with important implications for the way social work is configured and practiced.

Psychosocial Aspects of Oncology

The increase in the number of survivors, along with a cultural shift that emphasized open communication of cancer diagnosis and prognosis, has led to greater recognition of psychosocial needs of patients as well as the needs of families (IOM, 2006 ). Problems of survivors became visible initially when some survivors of childhood cancers, the first group to respond to new treatments, began to show late effects of initial treatment: including reduced fertility and risks for developing secondary cancers, as they moved into adolescence and young adulthood. Now, it is recognized that cancer survivors of all ages experience problems such as fatigue, sleep difficulties, depression, fear of cancer recurrence, and financial issues (IOM, 2006 ).

New treatments mean that cancer patients are now sometimes faced with difficult treatment decisions. For example, recent research suggests that some early cancers do not progress, even when untreated (e.g., early stage breast and prostate cancers). Also, many of the new treatments are expensive and are not covered by insurance. Patients and families may find themselves choosing prolonged survival but at the cost of bankruptcy as well as physical, psychological, social, and financial distress. Some patients are faced with choosing to know whether they carry genes that predispose them to cancer, with enormous impact not on themselves but on their family members, including children (or future children). In stark contrast to the days when cancer patients were not told that they had cancer, patients in the 21st century have to comprehend and manage an overwhelming amount of information and face daunting choices that require complex negotiations with family members such as issues on when and how to inform children and the need to identify their core values.

Recognizing the increased importance of psychosocial issues in today’s cancer care, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) developed the concept of cancer-related “distress” and published its first guidelines for distress management in 1999 . The NCCN defines “distress” as the “multifactorial unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological (cognitive, behavioral, emotional), social, and/or spiritual nature that may interfere with the ability to cope effectively with cancer, its physical symptoms, and its treatment” (NCCN, 2016 ). The NCCN also developed the Distress Thermometer, an instrument to detect distress, and advised performing distress screening in all clinical settings for those diagnosed with cancer. This recommendation was often ignored. Jacobsen and Ransom ( 2007 ) found that of NCCN member institutions that treated adults with cancer only three of the country’s 18 top cancer centers surveyed routinely performed distress screening on all patients.

In 2008 an influential report by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (now the Academy of Medicine, part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine), entitled Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs , concluded that there was sufficient evidence to support the provision of psychosocial health services in cancer care to all patients who need them. Meeting this standard of care, the IOM committee noted, required clinical care protocols that would identify each patient’s psychosocial health needs; link the patient with needed services and coordinate biomedical and psychosocial care; and systematically followed up and adjusted plans as needed. It emphasized that for many patients with cancer, this standard of care was not being met.

Building on the NCCN guidelines and the IOM report, the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) has mandated distress screening as a clinical activity required for accreditation. The CoC is the primary accrediting body for as many as 1,500 cancer-treating programs serving approximately 70% of all cancer patients in the United States. As of 2015 , CoC-accredited cancer programs must demonstrate compliance with patient-centered standards of care as a condition for cancer center accreditation.

Under this mandate, cancer centers are required to have protocols to screen and identify patients experiencing distress and to refer them, when appropriate, for psychosocial care. Centers must also provide evidence that distress-screening protocols are carried out as intended and result in appropriate referral and follow-up when indicated (ACoS, 2016 ).

Newer research on the contribution of stress and stressful living conditions to cancer development have important implications for social work. Oncology social workers most often focus on the individual and family levels when considering both prevention and treatment. However, the profession’s roots are more closely associated with neighborhood- and community-level interventions (Specht & Courtney, 1994 ). This new understanding of how multiple levels (genetic, biological, environmental, behavioral) interact in cancer development and treatment may lead to more oncology social work intervention at the “macro” levels (Werner-Lin, McCoyd, Doyle, & Gehlert, 2016 ).

Research in Psychosocial Oncology

Psychosocial care for cancer patients and their families reflects developments in the field of oncology, as well as those in mental health care more generally, and this is reflected in psychosocial oncology research. In the earliest days, not surprisingly, the focus of both practice and research was on dealing with death and dying. Early work with cancer patients, a growing interest in the more open way of approaching death promoted by Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, a nurse from England, and the work of sociologists Anselm Strauss (Glaser & Strauss, 1965 , 1968 ) and Barney Glaser focused attention on the negative outcomes of the common practice of withholding a cancer diagnosis to patients. Patients were often isolated and unsupported at the time of death. As open communication became the norm, psychiatrists and other psychosocial providers were able to offer therapies for cancer patients and families.

Early research in the field of psychosocial oncology was conducted primarily by the psychiatrists who had joined the research-focused cancer centers then developing (Holland, 1998 ). One of the earliest centers for psychosocial research on the impact of cancer was the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, under Arthur Sutherland. This group produced a number of studies on the psychological impact of cancer and care of the dying (Holland, 1998 ). Another early center, led by Avery Weisman at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, shed light on patient reaction to a cancer diagnosis (Weisman, Worden, & Sobel, 1980 ). They conducted studies that led to the first tool used to detect distress levels in patients (Zabora & MacMurray, 2012 ).

As cancer treatments improved, psychosocial services and research expanded. A strong leader in the field was Jimmie Holland, now known as the mother of psycho-oncology, who chaired the psychiatry department at Memorial Sloan Kettering, in New York City. Other influential pioneers flourished on the West Coast. David Spiegel (Stanford) and Fawzy Fawzy (UCLA) tested the effect of psychosocial interventions on cancer patients. Working with one of the originators of group psychiatry (Yalom, 1970 ), Speigel applied this type of group therapy for women with Stage III breast cancer. The therapy was based on socio-emotional expression, based on the theory that being open about negative emotions (e.g., fear, depression). To Spiegel’s surprise, the socio-emotional group therapy not only proved to be beneficial to psychological health of the women, as he had expected, but it showed longer survival of the experimental group (Spiegel, Bloom, Kramer, & Gottheil, 1989 ). (This finding was not supported in subsequent research, but it spurred many cancer programs to add psychosocial programs.) Fawzy’s research tested the effect (including biological) of psychoeducation with melanoma patients (Fawzy, 1989 ).

As research in psychosocial oncology expanded, new organizations developed to bring investigators together in influential conferences. In the early stage, existing cancer groups added psychosocial subgroups, such as the Cancer and Leukemia Group (CALGB), NCI’s Psychosocial Collaborative Oncology Group (PSYCOG), and the European Organization for Research in the Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) (Holland, 1998 ). In 1984 the International Psychosocial Oncology Society (IPOS) was formed by the group of scientists (mainly psychiatrists) who were studying the psychosocial aspects of cancer in Europe and the United States. They held their first conference in Beaune, France, in 1994 . Regional societies (e.g., European, American, Canadian, Australian) were formed soon after, creating an international network. The traditional practice of not telling cancer patients the truth about their diagnosis waned around the globe, creating new opportunities for psychosocial services and research. These national, regional, and international societies have grown rapidly as the field of psychosocial oncology has expanded. Meetings of national, regional, and international psychosocial oncology societies and their journal, Psycho-oncology , with Jimmie Holland serving as editor, have been the prime venue for the exchange of scientific information, networking, and training in psychosocial oncology research. In addition, Dr. Holland has edited the Handbook of Psychooncology (with Julia Rowland), and later, Psycho-oncology (Holland, 1998 ), now in its third edition, which serves as the principal reference for researchers in this field.

In the 1990s there was an explosion of research on psychosocial aspects of cancer, including research on the physical, psychological, and social consequences of the disease and its treatments. Also, a body of research developed on interventions, including research on support groups, psychotherapy, problem-solving approaches, cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness, and yoga. This reflects the development and testing of measurement instruments that were necessary to study the effectiveness of interventions. These new instruments, targeted to cancer patients rather than those with mental illness, emphasized “quality of life.” Over time, versions of these instruments were developed for specific types and stages of cancer (Cella, 1989 ; Cella et al., 1993 ). Combined with the increasingly sophisticated scales to screen for psychosocial distress (Zabora & MacMurray, 2012 ), these instruments, as well as those that measure mental disorders (anxiety and depression), made it possible for researchers to assess the impact of psychosocial services on patients and families.

By the turn of the century, there was enough research to support review articles and meta-analyses, generally showing the positive effect of psychosocial interventions (Cwikel, Behar, & Rabson-Hare, 2000 ; Faller et al., 2013 ; Graves, 2003 ; McQuellon & Danhauer, 2006 ; Meyer & Mark, 1995 ; Schneider et al., 2010 ), medical cost-offsets (Carlson & Bultz, 2003 , 2004 ), and even survival (Fu et al., 2016 ).

This research led to widening recognition that the psychosocial impact of cancer was significant and that negative consequences could be reduced or avoided by providing evidence-based interventions. Also, it was this research that led to the development of distress screening, and the highly influential IOM report (discussed earlier) on the importance of caring for the “whole patient” and not just the cancer itself (IOM, 2008 ). The IOM report also included a recommendation about research priorities, calling on organizations sponsoring research in oncology care to include as funding priorities “tools and strategies for use by clinical practices to ensure that all patients with cancer receive care that meets the standard of psychosocial care” (IOM, 2008 ).

The Development of Oncology Social Work

The developments discussed in the previous sections have all shaped oncology social work. For example, the Commission on Cancer mandate focused attention on oncology social workers implementing distress screening as well provide appropriate follow-up services. Before discussing these recent developments, however, it is important to place the field of oncology social work in a historical context.

Oncology social work has been impacted by the changes in cancer and its treatment, changes in the health-care system, and by greater recognition of the importance of psychosocial care in the wider professional community (see “Research in Psychosocial Oncology” section) (Hedlund, 2015 ). Although the field has grown and changed in response, a strong foundation had been built many years before.

Following the Second World War, the medical field became increasingly specialized, backed by a strong research base funded by the National Institutes of Health. As a result, the role of medical social workers also became more varied. While the early social work departments employed social workers across many different hospital settings, increased medical specialization and autonomy meant that funding for social work positions shifted to medical departments such as pediatrics, medicine, surgery, oncology, and psychiatry. It became difficult to maintain consistent policies and standards across departments who saw the role (and value) of social workers very differently. For example, many pediatrics departments relied heavily on social workers to work with the families of their patients, while surgery departments typically employed small numbers of social workers, primarily for discharge planning. As cancer treatment began to separate from the broader medical departments (medicine, surgery) and move into standalone centers, oncology social work began to develop as a separate field within medical social work. This new field was strongly affected by the changes in the treatment of oncology patients, which occurred in the late 20th century (see The Development of the Field of Oncology section)

Two early oncology social workers were Eleanor Cockerill (Curran & Cockerill, 1948 ) and Bernice Catherine Harper, from California’s City of Hope National Medical Center (Harper, 1975 , 1977 / 1994 ). As the major cancer centers developed and grew, oncology social work services expanded, initially in the National Cancer Institute (NCI) designated programs. Over time, the scope of oncology social work practice expanded, and oncology social workers began to see themselves as a significant subgroup of hospital-based social workers possessing a specialized skill set. Informal groups of oncology social workers began to form in major cities. These groups often included other professionals, such as nurses and psychiatrists, who were interested in the psychosocial aspect of cancer. By the 1970s, groups were meeting in Boston, New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. In 1977 , the Association of Pediatric Oncology Social Workers (APOSW) was formed. This was the first formal organization of social workers dedicated to the support of young cancer patients and their families, and it began to hold annual conferences. Around the same period, the American Cancer Society focused attention on the psychosocial aspect of cancer care, holding “human values conferences” where oncology social workers were invited as both participants and guest speakers. These events also became networking centers for a first generation of oncology social workers (e.g., Joan Herman, Judith Ross, Pat Fobair, Grace Christ, and Marie Lauria) to share knowledge and ideas for research.

With the support the American Cancer Society, a fledging network of oncology social workers took steps to form a professional organization (Fobair et al., 2009 ). Initially (in 1983 ), the ACS formed a national advisory committee on oncology social work and organized a national educational workshop (in 1984 ) to get the ball rolling for a new professional organization, which became the National Association of Oncology Social Workers (NAOSW). In the meantime, Grace Christ, chief of the Social Work Department at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, launched the Journal of Psychosocial Oncology —as a publishing outlet for the new organization.

Although the NAOSW held annual meetings and membership grew through the 1980s and 1990s, financial viability was a consistent problem. Membership dues and conference fees did not produce enough income to survive, and the organization had to rely on the support of the cancer centers (usually the employer of the president) for administrative support. By the mid-1990s, the NAOSW was in financial crisis, and under the leadership of presidents Jim Zabora and Hester Hill, it was dissolved and them re-created with a more financially viable structure under the name Association of Oncology Social Work (AOSW). And the Journal of Psychosocial Oncology , under the leadership of editors Grace Christ and Jim Zabora, was offered as an AOSW membership benefit.

The American Cancer Society continued to support AOSW, providing funding for leadership development, strategic planning, and collaboration with national cancer organizations throughout the organization’s history (Fobair et al., 2009 ). The ACS also published two books that became classics in oncology social work, Oncology Social Work: A Clinician’s Guide (Stearns, Lauria, Hermann, & Fogelberg, 1993 ), and Social Work in Oncology: Supporting Survivors, Families and Caregivers (Luria, Clark, Hermann, & Stearns, 2001 ). Also, in 2003 Cancer Support Groups: A Guide for Facilitators (Kraweick & Greer, 2015 ) was published.

AOSW has collaborated with other organizations to advance the field of oncology social work. For example, in 1998 AOSW collaborated with the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) and the National Coalition of Cancer Survivors (NCCS) to produce the so-called Cancer Survival Toolbox. (The Toolbox project was later joined by the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) (Clark & Collins, 2015 ). During the 1990s and 2000s, AOSW allied with patient advocacy and health-care professional organizations and assumed a position of leadership in a national effort to set a standard for the inclusion of quality psychosocial care for all cancer patients and their families. AOSW members were “at the table” when the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) began to develop distress screening tools. When the CoC mandated distress screening (discussed in the section “Research in Psychosocial Oncology” ) oncology social workers, especially those working in cancer centers accredited by the ACoS, began to incorporate distress screening into their practices (Oktay, Nedjat-Haiem, Davis, & Kern, 2012 ; Burg, Adorno, & Hidalgo, 2012 ). This type of screening departs from the more traditional approach in oncology social work, where patients are referred and then fully assessed. However, staffing levels remain too low to allow this approach for every patient in all but a few settings. Distress screening is seen as responsive to the IOM emphasis on treating the whole patient, so that oncology social workers now do a more thorough assessment on patients who screen with high distress scores and/or problems.

Another important 21st-century development in the field of oncology social work is the publication of the Handbook of Oncology Social Work: Psychosocial Care for People with Cancer (Christ, Messner, & Behar, 2015 ). It covers a wide range of topics in over 800 pages, illustrating the extensive knowledge the field has accumulated in its short life.

AOSW has grown to over 1,400 members, holds annual conferences, has an active listserv, many special interest groups, as well as a webpage and Facebook and Twitter accounts; they have also added webinars to continuously spread knowledge throughout the community. AOSW also offers a certification in oncology social work (the OSW-C), now widely recognized in the field (Vaitones, Schutte, & Mattison, 2015 ).

Research in Oncology Social Work

Oncology social workers make up the majority of those offering psychosocial oncology services, but researchers investigating psychosocial outcomes have contributed a disproportionately small portion of research in this field. There are many reasons for this, including the scarcity of oncology social work researchers, lack of funding for social work research, and few opportunities for advanced research training and activities. The issues faced by oncology social work researchers are much the same as those identified by the NIMH Task Force (discussed in Research in the Social Work Profession s ection) 25 years ago.

In spite of these limitations, oncology social work researchers have made important contributions to the knowledge base that supports psychosocial care. In fact, oncology social work research has a long history, as some of the earliest oncology social workers successfully combined research with their clinical practice. One of the first to publish empirical research in a scientific journal was Ruth Abrams, at Massachusetts General Hospital (Abrams & Finesinger, 1953 ; Abrams, 1966 , 1974 ). Abrams later established the Ruth Abrams Interdisciplinary Research Program and hired Barbara Berkman as the first director. Dr. Berkman was interested in cancer in the elderly, since she discovered that cancer was a predictive factor for referral to social work for elderly hospital patients (Berkman & Rehr, 1973 ; Berkman, Rehr, & Rosenberg, 1980 ). Dr. Berkman combined an active research career with professional leadership, advocating for the new profession of oncology social work and eventually establishing the Hartford Geriatric Scholars program for social work education, training, and advocacy. (See the section “American Cancer Society”).

Since the early days, oncology social work leaders have combined practice, leadership, advocacy, and research (Fobair et al., 2009 ). Oncology social work researchers bring a unique perspective to their research in psychosocial oncology. For example, social work is known for “starting where the client is”—a patient-centered perspective. This is reflected in research that explores the cancer experience of patients and family members. One of the earliest examples was the work of a Patricia Fobair, a radiation oncology social worker at Stanford in the early 1980s: her work explored the problems of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma who were treated with radiation (Fobair, Hoppe, Bloom, Cox, Varghese, & Spiegal, 1986 ). Other examples include work with children whose parents had terminal cancer (Christ, 2000 ), women whose mothers had breast cancer (Oktay, 2005 ), and women with the BRCA 1 or 2 genes (Werner-Lin, 2007 ). Many of these studies led to new interventions based on the patients’ experience (Abernathy et al., 2010 ; Siegel et al., 1992 ).

As another perspective of social work is human development over the life course, it is not surprising that oncology social work research also reflects a developmental framework (Oktay & Walters, 1991 ) and/or focuses on specific age groups, such as children (Jones, Parker-Raley, & Barczyk, 2011 ; Weiner, Battles, Bernstein, Long, Mansky, & Mackall, 2006 ), adolescents and young adults (Zebrack, 2011 ; Zebrack & Isaacson, 2012 ) or the elderly (Rohan et al., 1995 ; Smith et al., 2008 ).

Social work also applies a conceptual model called the “Person-in-Environment” and this perspective, too, is reflected in oncology social work research. For many of these researchers, this has led to a focus on cancer patients in the context of their interpersonal relationships and families. This work includes studies of couples (Kayser, Feldman, Borstelmann, & Daniels, 2010 ), daughters (Oktay, 2005 ), and mothers (Kayser & Sormanti, 2002 ; Lewis et al., 2000 ).

Social justice and cultural competence are core values of social work. Not surprisingly, oncology social work researchers have engaged in research focusing on health disparities (Ell et al., 2005 ; Ell, Vourlekis, Lee, & Xie, 2007 ; Gehlert et al., 2008 ; Gehlert, Mininger, & Ciriano-Steffens, 2010 ), minority populations (Lee & Vang, 2010 ; Davis, Emerson, & Husaini, 2005 ; Wells et al., 2015 ) and multicultural perspectives (Kayser et al., 2014 ).

With the focus on screening for distress in cancer patients discussed earlier, oncology social work researchers have also focused in this area, including the instruments themselves (Zabora, Smith-Wilson, Fetting, & Enterline, 1990 ) and the prevalence of psychosocial distress (Zabora, Brintzenhofe-Szoc, Curbow, Hooker, & Piantadosi, 2001 ). (Also see the section “A Project to Assure Quality Cancer Care [APAQCC].”)

Finally, the field of oncology social work itself has been the focus of some oncology social work research (Rohan & Bausch, 2009 ). For example, AOSW’s Social Workers in Oncology Research Group (SWORG) conducted a membership survey of oncology social work activities (Zebrack et al., 2008 ). Others have studied the implementation of distress screening (Burg, Adorno, & Hidalgo, 2012 ; Oktay, Nedjat-Haiem, Davis, & Kern, 2012 ; Zebrack et al., 2015 , 2016 ).

In order to build a strong research base for the profession, oncology social work needs a combination of resources. These include support and excellent training for doctoral students, mentoring and funding for researchers, and opportunities for networking and interaction with other researchers—both within the field and in related fields as well. The major sources of support for oncology social work research have been the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the Association for Oncology Social Work (AOSW). Other important support has come from the National Association of Social Work (NASW), which collaborated with ACS and AOSW in several projects discussed below. In addition, in 2002 the National Cancer Institute awarded NASW a grant to investigate barriers to the incorporation of research into oncology social work practice. The expert panel verified that many of the barriers to the use of research in oncology social work practice identified in the past, such as lack of easy access to research results, lack of mentoring, inadequate administrative support, and under-funding remained barriers in 2002 (NASW, 2003 ). The report identified a number of strategies to improve the practice-research linkage. However, most of these required funding, which, unfortunately was not forthcoming (Zlotnik, 2016 , personal communication).

American Cancer Society

The American Cancer Society has contributed significantly to the development of oncology social work researchers through its Health Professional Training Grants in Cancer Control. This program, which began in 1989 under the leadership of Barbara Berkman, provides grants to doctoral students in oncology social work. The program began as a post-master’s clinical training grant, emphasizing advanced clinical practice. By 1999 the program shifted focus to support doctoral student training, and in 2004 it was adapted to allow for support to begin at the start of doctoral education and continue for up to four years. To strengthen the research training of the grantees, funded doctoral scholars and their mentors attend a pre-conference research training institute in conjunction with the annual meeting of the Society for Social Work Research (SSWR), the prime research organization in social work. Over 30 oncology social work doctoral students have received support through this program (Kraweick & Greer, 2015 ).

The AOSW has also recognized and supported research in the field. Several doctorally trained social workers have also served as AOSW president, strengthening the commitment to research in the organization. In the 1990s, oncology social workers recognized the need for research on oncology social work practice and its impact on patient outcomes and cancer-care delivery. Changes in the American health-care system and its financing changed the way social work services were paid for, from the blanket coverage traditionally offered to hospitals, to a managed care approach. As a result, health-care professionals had to demonstrate their effectiveness, especially those not providing traditional medical care. AOSW responded with the development of the social work Oncology Research Group (SWORG). SWORG was approved as a special committee of the board in 1996 , with the goal of development and implementation of research protocols to be used at multiple sites. Other goals were to promote interest in research in the membership, and to generate research proposals for AOSW. It was under the auspices of SWORG that studies of screening, under Zabora’s leadership, of the oncology social work role (Zebrack et al., 2008 ) and of distress screening (Brinzenthof-Socz et al., 2015 ) were conducted. SWORG also published a guide to research for AOSW members (Roberts, Brintzenhofe-Socz, Zebrack, & Behar, 2003 ). AOSW members participated on the committees whose work served as the foundation for the NCCN, IOM, and CoC standards on distress screening. SWORG decided to conduct additional research in distress screening, to help prepare the profession for its expanded role. They used the JPO to share current knowledge, publishing a special issue in the fall of 2012 , edited by Zebrack and Burg. Articles included an overview of distress screening, analysis of screening instruments, qualitative research on how social workers were handling the challenge (Burg, Adorno, & Hidalgo, 2012 ; Oktay, Nedjat-Haiem, Davis, & Kern, 2012 ), among others. The group developed a membership survey to be conducted through the AOSW listserv; this survey was seeking opinions on current experience with distress screening, as well as barriers and facilitating factors. The results of this survey were published in 2015 (Brinzenhof-Socz et al., 2015 ).

Another important resource for networking and strategic planning for oncology social work research has been the development of an annual meeting of the leadership of the field in Louisville. In 2011 Kayser accepted the first endowed professorship in oncology social work (the Dr. Renato LaRocca Chair of Oncology Social Work) at the Kent School of Social Work in Louisville, Kentucky. As a part of her professorship and with funding through the Kent School of Social Work, Kayser has hosted an annual social work research meeting with the purpose of establishing and acting upon a set of priorities for social work research. Important initiatives that have advanced oncology social work research were produced as a result of these meetings, including the aforementioned special issue on distress screening for the JPO, a large-scale survey of AOSW member experiences with implementation of distress screening, and AOSW’s Project to Assure Quality Cancer Care (APAQCC).

In spite of these supportive programs, oncology social work research continues to struggle for funding. This means that most of the research related to psychosocial oncology lacks a social work (let alone patient) perspective. Even now, little is known about the services that social workers offer and their effectiveness. Even basic needs of the profession, such as staffing standards, remain poorly understood.

Recent Developments in Oncology Social Work Research

A project to assure quality cancer care (apaqcc).

Among the responses of oncology social work researchers to the important changes in the field, especially the mandates by the CoC, was the creation of Association of Oncology Social Work’s Project to Assure Quality Cancer Care (APAQCC). Initiated in 2014 , APAQCC involved sixty-five Commission on Cancer (CoC)–accredited cancer programs across the United States (and two in Canada) and academic partners at the University of Michigan School of Social Work and the University of Louisville Kent School of Social Work. Its purpose was twofold. Its first aim was to examine the capacity of cancer programs to provide quality psychosocial support services; and the second aim was to evaluate the implementation of distress screening. The project targeted oncology social workers as the experts on psychosocial care at their institutions and provided them with data necessary to influence change and assume a leadership role at their institutions.

During Phase I, APAQCC participants surveyed cancer-care providers at their respective institutions as a means for assessing the capacity of their cancer program to deliver psychosocial care. In Phase II, APAQCC participants conducted a two-month retrospective review of electronic medical records for patients seen in their cancer program to assess adherence and responsiveness to their institution’s prescribed psychosocial screening protocol, as well as the medical service utilization of those patients.

Research Institutes

Another important development was that the AOSW held its first two-day Post-Conference Research Institute in 2016 , immediately following the AOSW’s 32nd Annual Conference. The effort grew out of the recognition that these forces have set the stage to foster a stronger research agenda for the field and to bridge the gap between research and practice. The research institute, co-chaired by AOSW research director Julianne S. Oktay, and Brad Zebrack, was conceived as a venue for researchers, including established leaders in the field, and oncology social work practitioners interested in conducting research, meeting others with similar interests, and to facilitate mentorship. Mini lectures, panel discussions, and roundtable sessions were designed as opportunities for participants to present and discuss ideas, research topics, and challenges in oncology social work research. These included a keynote address: “Notes from the Data-Mines: Research, Practice and Life Lessons Learned from Personal Encounters with Cancer” presented by Irwin Epstein of Hunter College; a panel discussion on “The Funding Quest: Opportunities, Challenges, and Successes”; expert-led roundtable discussion sessions on identifying research opportunities in social work practice; and a presentation on “Publishing Oncology Social Work Research: New Directions for the Journal of Psychosocial Oncology .” A white paper on the research institute was developed to communicate the recent focus on research within AOSW to members as well as the outside community.

Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN)

Building upon the success of APAQCC, as well as recent recognition of the potential of practice-based research networks to address issues of relevance to social work, particularly health disparities (Gehlert, Walters, Uehara, & Lawlor, 2015 ) research leaders in oncology social work, with support from PCORI, aim to develop a collaborative research group for psychosocial oncology—a sustainable community of cancer patient advocates, oncology social workers, and social work researchers devoted to assuring the delivery of high-quality cancer care for all patients and their families. This cooperative group will draw upon the collective wisdom of oncology social work practitioners, academic researchers, and patient advocates. The group intends to establish an efficient structure within which to answer research questions arising in the practice of social work with cancer patients and their families. Social work researchers will have opportunities to propose and conduct research from within the collaborative, and the lessons learned through conduct of studies undertaken by the cooperative group will inform future studies. At present, vital intellectual capital is lost upon the completion of freestanding studies conducted in silos by individuals or small teams of investigators, which is typically the case in psychosocial oncology research.

The goal is to define and conduct high-impact, clinically relevant research and serve as a venue for ongoing recruitment of new stakeholders and expertise into the field of psychosocial oncology research. The PCRC also will be designed to enhance oncology social workers’ collective knowledge and ability to design and conduct research, disseminate findings, and achieve systems changes that ultimately result in improved patient outcomes and institutional cost savings.

Oncology social work research has contributed to the vibrancy of the field from its earliest days. Through the decades, the profession itself has grown while also gaining stability and legitimacy. Research contributes to the profession by providing knowledge that forms the basis of its professional expertise. As of the early 21st century , oncology social work research is stronger than ever. It is increasingly recognized as critical to understanding the complex interplay of factors that determine the development and outcome of cancer, as evidenced by Sarah Gehlert’s membership on the Board of Scientific Counselors at the National Human Genome Institute of NIH. It has a cadre of well-qualified researchers and outstanding training programs for new PhDs. The continued support of the ACS is critical to this. It also has the support of the AOSW and has been successful in conducting a number of research studies on the membership that have contributed greatly to the knowledge base of the profession. It has successfully secured funding for these research projects and for training in research. The field has greatly benefited from its first endowed professorship at the University of Louisville Kent School of Social Work. Although oncology social work research stands in a pivotal position to conduct much-needed research, now recognized as important by the highest levels in the country (reflected in several reports by the influential IOM), the profession is still challenged in finding the kind of support from major funders of cancer research (e.g., the NCI) required to establish and reinforce a strong knowledge base. Also lacking are vigorous postdoctoral opportunities. While there is some support for early career researchers in psycho-oncology, support that targets oncology social work is lacking. Thus, new PhDs who seek careers in research struggle to find their footing. Attention needs to be paid to these issues if research is to fulfill its promise to the profession.

- Abernathy, A. , Herndon, J. E. , Coan, A. , Staley, T. L. , Wheeler, J. L. , Rowe, K. , et al. (2010). Phase 2 pilot study of Pathfinders: A psychosocial intervention for cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer , 18 (7), 893–898.

- Abrams, R. D. (1966). The patient with cancer—his changing pattern of communication. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians , 16 (6), 237.

- Abrams, R. D. (1974). Not alone with cancer: A guide for those who care. What to expect, what to do . New York: Charles C. Thomas.

- Abrams, R. D. & Finesinger, J. E. (1953). Guilt reactions in patients with cancer. Cancer , 6 (3), 474–482.

- ACoS . (2016). American College of Surgeons: Cancer program standards .

- Austin, D. (1991). Building social work knowledge for effective services and policies: A plan for research development . Report of the Task Force on Social Work Research. National Institute of Mental Health. Rockville, MD: NIMH.

- Bartlett, H. (1957). 50 Years of Social Work in the Medical Setting . New York: NASW.

- Berkman, B. & Rehr, H. (1973). Early social service case finding for hospitalized patients: An experiment. Social Service Review , 47 (2), 256–265.

- Berkman, B. , Rehr, H. , & Rosenberg, G. (1980). A social work department develops and test a screening mechanism to identify high social risk situation. Social work in health care , 5 (4), 373–385.

- Bracht, N. F. (1978). Social work in health care: A guide to professional practice . New York: Haworth.

- Brawley, O. W. (2017). Accepting the existence of breast cancer overdiagnosis . Annals of Internal Medicine , 166 (5), 364–365.

- Brintzenthofe-Szoc, K. , Davis, C. , Kayser, K. , Lee, H. Y. , Nedjat-Haiem, F. , Oktay, J. S. , et al. (2015). Screening for psychosocial distress: A national survey of oncology social workers. Journal Psychosocial Oncology , 33 (1), 34–47.

- Burg, M. , Adorno, G. , & Hidalgo . (2012). An analysis of Social Work Oncology Network Listserv postings on the Commission on Cancer’s distress screening guidelines. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology , 30 (6), 636–651.

- Cannon, I. M. (1913). Social work in hospitals: A contribution to progressive medicine . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Carlson, L. E. & Bultz, B. D. (2003) Benefits of psychosocial oncology care: Improved quality of life and medical cost offset. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes , 1 (10), 8 .

- Carlson, L. E. , & Bultz, B. D. (2004). Efficacy and medical cost offset of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: Making the case for economic analyses. Psycho-oncology , 13 , 837–849.

- Cella, D. F. (1989). Quality of life. In J. C. Holland (Ed.), Psycho-oncology (pp. 1135–1146). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cella, D. F , Tulsky, D. S. , Gray, G. , Sarafin, B. , Linn, E. Bonomi, A. , et al. (1993). The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. Journal Clinical Oncology , 11 (3), 570–579.

- Christ, G. (2000). Healing children’s grief: Surviving a parent’s death from cancer . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Christ, G. H. , Messner, C. & Behar, L. (Eds.). (2015). Handbook of oncology social work: Psychosocial care for people with cancer . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Clark, E. J. & Collins, S. (2015). NASW and oncology social work. In G. H. Christ , C. Messner , & L. Behar (Eds.), Handbook of oncology social work: Psychosocial care for people with cancer (pp. 763–768). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Curran, J. A. & Cockerill, E. (1948). Widening horizons in medical education: A study of the teaching of social and environmental factors in medicine, 1945–1946 . New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund.

- Cwikel, J. , Behar, L. , & Rabson-Hare, J. (2000). A comparison of a vote count and a meta-analysis review of intervention research with adult cancer patients. Research on Social Work Practice , 10 , 139–158.

- Davis, C. , Emerson, J. S. , & Husaini, B. A. (2005). Breast cancer screening among African American women: Adherence to current recommendations. Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved , 16 (2), 308–314.

- Ell, K. , Sanchez, K. , Vourlekis, B. , Lee, P. J. , Dwight-Johnson, M. , Lagomasino, I. , et al. (2005). Depression, correlates of depression, and receipt of depression care among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology , 23 (13), 3052–3060.

- Ell, K. , Vourlekis, B. , Lee, P. J. , Xie, B. (2007). Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: A randomized clinical trial. Preventive Medicine , 44 (1), 26–33.

- Faller, H. , Schuler, M. , Richard, M. , Heckl, U. , Weis, J. , & Kuffner, R. (2013). Effects of psycho-oncologic interventions on emotional distress and quality of life in adult patients with cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology , 31 (6), 782–793.

- Fawzy, F. (1989). Psychoeducational interventions. In J. C. Holland (Ed.), Psycho-oncology (pp. 676–693). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Fobair, P. , Hoppe, R. T. , Bloom, J. , Cox, R. , Varghese, A. , & Spiegal, D. (1986). Psychosocial problems among survivors of Hodgkin’s disease. Journal of Clinical Oncology , 4 (5), 805–814.

- Fobair, P. , Stearns, N. , Christ, G. , Dozier-Hall, D. , Newman, N. , Zabora, J. , et al. (2009). Historical threads in the development of oncology social work. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology , 27 , 155–215.

- Fu, W. W. , Popovic, M. , Agarwal, A. , Milakovic, M. , Fu, T. S. , McDonald, R. , et al. (2016). The impact of psychosocial intervention on survival in cancer: A meta-analysis. Annals of Palliative Medicine , 5 (2), 93–106.

- Gehlert, S. (2006). The conceptual underpinnings of social work in health care. In S. Gehlert & T. A. Browne (Eds.), Handbook of health social work (pp. 3–22). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley.

- Gehlert, S. , Mininger, C. , & Ciriano-Steffens, T. M. (2010). Placing biology in breast cancer disparities research. In Communities, neighborhoods and health (pp. 57–72). New York: Springer.

- Gehlert, S. , Sohmer, D. , Sacks, T. , Mininger, C. , McClintock, M. , & Olopade, O. (2008). Targeting health disparities: A model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Health Affairs , 27 (2), 339–349.

- Gehlert, S. , Walters, K. , Uehara, E. & Lawlor, E. (2015). The case for a national health social work practice-based research network in addressing health equity. Health and Social Work , 40 (4), 253–255.

- Glaser, B. , & Strauss, A. (1965). Awareness of dying . Chicago: Aldine.

- Glaser, B. , & Strauss, A. (1968). Time for dying . Chicago: Aldine.

- Graves, K. (2003). Social cognitive theory and cancer patients’ quality of life: A meta-analysis of psychosocial intervention components. Health Psychology , 22 , 210–219.

- Harper, B. C. (1975). Social aspects of cancer recovery. Cancer , 3 (1), 1–2.

- Harper, B. C. (1977/1994). Death: The coping mechanisms of the health professional . Greenville, SC: Southeastern University Press.

- Haynes, M. A. , & Smedley, B. D. (1999). The unequal burden of cancer: An assessment of NIH research and programs for ethnic minorities and the medically underserved . Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press.

- Hedlund, S. (2015). Oncology social work: Past, present, and future. In G. H. Christ , C. Messner , & L Behar (Eds.), Handbook of oncology social work: Psychosocial care for people with cancer (pp. 9–13). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Holland, J. C. (1998). Societal views of cancer and the emergence of psycho-oncology . In J. C. Holland (Ed.), Psycho-oncology (pp. 3–15). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jacobsen P. B. , & Ransom, S. (2007). Implementation of NCCN distress management guidelines by member institutions. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network , 5 (1), 99–103.

- Jones, B. L. , Parker-Raley, J. , & Barczyk, A. (2011). Adolescent cancer survivors: Identity paradox and the need to belong. Qualitative Health Research , 21 (8), 1033–1040.

- IOM . (2006). From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition . Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- IOM . (2008). Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs . Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- IOM . (2013). Delivering high-quality cancer care: Charting a new course for a system in crisis . Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Kayser, K. , Cheung, P. K. H. , Rao, N. , Chan, Y. C. L. , Yu Chan, Y. , & Lo, P. (2014). The influence of culture on couples coping with breast cancer: A comparative analysis of couples from China, India, and the United States. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology , 32 (3), 264–288.

- Kayser, K. , Feldman, B. N. , Borstelmann, N. , & Daniels, A. (2010). The effects of a randomized couple-based intervention on the quality of life of breast cancer patients and their partners. Journal of Social Work Research , 34 (1), 20–32.

- Kayser, K. , & Sormanti, M. (2002). Identity and the illness experience: Issues faced by mothers with cancer. Illness, Crisis, and Loss , 10 , 10–26.

- Kiegher, S. M. (2000). Knowledge development in health and social work. Health Social Work , 25 (1), 3–8.

- Kraweick, V. , & Greer, G. (2015). The American Cancer Society’s contributions to oncology social work. In G. H. Christ , C. Messner , L. Behar (Eds.), Handbook of oncology social work: Psychosocial care for people with cancer (pp. 745–750). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lee, H. Y. & Vang, S. (2010). Barriers to cancer screening among Hmong Americans: The influence of health care accessibility, culture and cancer literacy. Journal of Community Health , 35 , 302.

- Lewis, F. M. , Behar, L. C. , Anderson, K. H. , Shands, M. E. , Zehlis, E. H. , Darby, E. , et al. (2000). Blowing away the myths about the child’s experience with the mother’s breast cancer. Cancer and the Family , 2 , 201–221.

- Luria, M. , Clark, E. , Hermann, J. , & Stearns, N. (2001). Social work in oncology: Supporting survivors, families and caregivers . Atlanta: American Cancer Society.

- McQuellon, R. P. , & Danhauer, S. C. (2006). Psychosocial rehabilitation in cancer care. In A. E. Chang , P. A. Ganz , D. F. Hayes , T. J. Kinsella , H. I. Pass , J. H. Schiller , et al. (Eds.), Oncology (pp. 1942–1954). New York: Springer.

- Meyer, T. J. , & Mark, M. M. (1995). Effects of psychosocial interventions with adult cancer patients: a meta-analysis of randomized experiments. Health Psychology , 14 (2), 101–108.

- NASW . (2003). Barriers of translating oncology research to social work practice. NASW in partnership with NCI. Washington, DC: NASW.

- NCCN . (2016). National comprehensive cancer network .

- Oktay, J. S. (2005). Breast cancer: Daughters tell their stories . New York: Haworth.

- Oktay, J. S. (2012). Grounded theory . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Oktay, J. S. , Nedjat-Haiem, F. , Davis, C. , & Kern, K. (2012). Distress screening: Experiences of oncology social workers. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology , 30 (6), 652–666.

- Oktay, J. S. , & Volland, P. J. (1987). Foster home care for the frail elderly as an alternative to nursing home care: an experimental evaluation. American Journal of Public Health , 77 (12), 1505–1510.

- Oktay, J. S. , & Volland, P. J. (1990). Post-hospital support program for the frail elderly and their caregivers: A quasi-experimental evaluation. American Journal of Public Health , 80 (1), 39–46.

- Oktay, J. S. , & Walter, C. A. (1991). Breast cancer in the life course: Women’s experiences . New York: Springer.

- Roberts, C. , Brintzenhofe-Socz, K. , Zebrack, B. & Behar, L. (2003). A social work guide to conducting research in psychosocial oncology . Philadelphia: AOSW.

- Rohan, E. A. , & Bausch, J. (2009). Climbing Everest: Oncology work as an expedition in caring. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology , 27 (1), 84–118.

- Rohan, E. A. , Berkman, B. , Walker, S. , & Holmes, W. (1995). The geriatric cancer patient: Ageism in social work practice. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 23 (1–2), 201–222.

- Schneider, S. , Moyer, A. , Knapp-Oliver, S. , Sohl, S. , Cannella, D. , & Targhetta, V. (2010). Pre-intervention distress moderates the efficacy of psychosocial treatment for cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine , 33 , 1–14.

- Siegel, K. , Mesagno, F. P. , Karus, D. , & Christ, G. , Banks, K. , & Moynihan, R. (1992). Psychosocial adjustment of children with a terminally ill parent. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 31 (12), 327–333.

- Simmons School of Social Work . (2016). The evolution of social work: Historical milestones .

- Smith, S. , Zimmerman, S. , Williams, C. S. , Preisser, J. S. , & Clipp, E. C. (2008). Post-traumatic stress outcomes in Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology , 26 (6), 934–941.

- Specht, H. , & Courtney, M. (1994). Unfaithful angels: How social work has abandoned its mission . New York: Free Press.

- Spiegel, D. , Bloom, J. R. , Kramer, H. C. , & Gottheil, E. (1989). Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet , 2 (8668), 888–891.

- Stearns, N. , Lauria, M , Hermann, J. & Fogelberg, P. (1993). Oncology social work: A clinician’s guide . Atlanta: American Cancer Society.

- Vaitones, V. , Schutte, J. , & Mattison, D. (2015). OSW-C: The importance of certification for oncology social workers. In G. H. Christ , C. Messner , L Behar (Eds.), Handbook of oncology social work: Psychosocial care for people with cancer (pp. 757–762). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Weiner, L. , Battles, H. B. , Bernstein, D. , Long, L. , Mansky, P. , & Mackall, C. (2006). Persistent psychological distress in long-term survivors of pediatric sarcoma. Psycho-oncology , 15 , 898–910.

- Weisman, A. D. , Worden, J. W. , & Sobel, H. J. (1980). Psychosocial screening and intervention with cancer patients: A research report . Boston: Harvard Medical School.

- Wells, A. A. , Shon, E. J. , McGowan, K. , & James, A. (2015). Perspectives of low-income African-American women non-adherent to mammography screening: the importance of information, behavioral skills, and motivation . Journal of Cancer Education , 32 (2).

- Werner-Lin, A. (2007). Danger zones: Risk perceptions of young women from families with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Family Process , 46 , 335–349.

- Werner-Lin, A. (2015). The oncology social worker and genomics. In G. H. Christ , C. Messner , & L. Behar (Eds.), Handbook of oncology social work: Psychosocial care for people with cancer (pp. 255–260). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Werner-Lin, A. , McCoyd, J. L. , Doyle, M. H. , & Gehlert, S. J. (2016). Leadership, literacy, and translational expertise in genomics: Challenges and opportunities for social work . Health Social Work , 41 (3), e52–e59.

- Yalom, I. D. (1970). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy . New York: Basic Books.

- Zabora, J. R. , Smith-Wilson, R. , Fetting, J. H. , & Enterline, J. P. (1990) An efficient method for psychosocial screening of cancer patients. Psychosomatics , 31 (2), 192–196.

- Zabora, J.R. , Brintzenhofe-Szoc, K. , Curbow, B. , Hooker, C. & Piantadosi, S. (2001) The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-Oncology 10(1) 19-28.

- Zabora, J. R. & MacMurray, L. (2012). The history of psychosocial screening among cancer patients. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology , 30 (6), 625–635.

- Zebrack, B. (2011). Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer , 117 (S10), 2289–2294.

- Zebrack, B. , & Isaacson, S. (2012). Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology , 30 (11), 1221–1226.

- Zebrack, B. , Kayser, K. , Padgett, L. S. , Sundstrom, L. , Jobin, C. , Nelson, K. , et al. (2016). Institutional capacity to provide psychosocial oncology support services: A report from the Association of Oncology Social Work. Cancer , 122 (12), 1937–1945.

- Zebrack, B. , Kayser, K. , Sundstrom, L. , Savas, S. , Henrickson, C. , Acquati, C. , et al. (2015). Psychosocial distress screening implementation in cancer care: An analysis of adherence, responsiveness, and acceptability. Journal of Clinical Oncology , 33 (10), 1165–1170.

- Zebrack, B , Walsh, K. , Burg, M. A. , Maramaldi, P. , & Lim, J. (2008). Oncology social worker competencies and implications for education and training. Health and Social Work , 47 (4), 355–375.

- Zimbalist, S. E. (1977). Historic themes and landmarks in social welfare research . New York: Harper & Row.

- Zlotnik, J. L. , Biegel, D. , & Solt, B. E. (2002). The Institute for the Advancement of Social Work Research: Strengthening social work research in practice and policy. Research on Social Work Practice , 12 (2), 318–337.

- Zlotnik, J. L. , & Solt, B. E. (2006, September). The Institute for the Advancement of Social Work Research working to increase our practice and policy evidence base. Research on Social Work Practice , 16 (5), 534–539.

- Zlotnik, J. L. , & Solt, B. E. (2008). Developing research infrastructure: The Institute for the Advancement of Social Work Research. Social Work Research , 32 (4), 201–207.

Other Resources

- New & Featured

- Forthcoming Articles

Printed from Encyclopedia of Social Work. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 25 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.150.64]

- 185.80.150.64

Character limit 500 /500

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Everything to Know About Oncology Social Workers

- What They Do

- How to Get Help

Frequently Asked Questions

When someone is diagnosed with cancer , the focus is usually on finding the most successful treatment options. But there’s more to dealing with cancer than medical therapies and procedures. Cancer may affect a person emotionally, socially, and financially, too. That’s when oncology social workers can help.

Oncology social workers are skilled professionals who provide emotional, psychological, social, and practical support for cancer patients. They help patients navigate different resources and unpack useful information. These experts address the patient as a whole, instead of only focusing on medical treatment.

This article discusses the role of oncology social workers as advocates for people with cancer.

SDI Productions / Getty Images

What Do Oncology Social Workers Do?

Oncology social workers perform a wide range of services, some of which include:

- Providing information to patients about their disease

- Helping patients explain their cancer diagnosis to family and friends

- Performing counseling services

- Leading or recommending support groups

- Acting as a mediator for patient/caregiver disputes

- Offering resources for financial assistance

- Explaining medical insurance coverage

- Helping patients find transportation to healthcare appointments

- Teaching patients how to perform relaxation and coping strategies

Oncology Social Workers and Research

Oncology social workers are becoming more involved in research, including leading research studies designed to improve patients' quality of life.

Managing Practical Concerns

Oncology social workers can help cancer patients sort out different practical or logistical issues. These professionals are trained to effectively explain a cancer diagnosis and treatments to patients and their family members.

Additionally, they may help patients pay their bills, understand their insurance coverage, or find resources for financial assistance. Sometimes, this involves showing patients how to fill out the necessary paperwork or requesting coverage information from insurance companies.

Oncology social workers can also help patients secure home care services, transportation, and childcare.

Providing Emotional Support

A cancer diagnosis can be psychologically challenging. An oncology social worker helps patients with their emotional needs. They can arrange hospice services (comfort care for patients at the end of life) or provide support for patients who are transitioning to survivorship (care after diagnosis and treatment).