- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 23 February 2024

Medico-legal risks of point-of-care ultrasound: a closed-case analysis of Canadian Medical Protective Association medico-legal cases

- Ross Prager ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8145-8141 1 , 2 ,

- Derek Wu 3 ,

- Gary Garber 4 , 5 ,

- P. J. Finestone 4 ,

- Cathy Zang 4 ,

- Rana Aslanova 4 &

- Robert Arntfield 1

The Ultrasound Journal volume 16 , Article number: 16 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

6022 Accesses

102 Altmetric

Metrics details

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has become a core diagnostic tool for many physicians due to its portability, excellent safety profile, and diagnostic utility. Despite its growing use, the potential risks of POCUS use should be considered by providers. We analyzed the Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA) repository to identify medico-legal cases arising from the use of POCUS.

We retrospectively searched the CMPA closed-case repository for cases involving diagnostic POCUS between January 1st, 2012 and December 31st, 2021. Cases included civil-legal actions, medical regulatory authority (College) cases, and hospital complaints. Patient and physician demographics, outcomes, reason for complaint, and expert-identified contributing factors were analyzed.

From 2012 to 2021, there were 58,626 closed medico-legal cases in the CMPA repository with POCUS determined to be a contributing factor for medico-legal action in 15 cases; in all cases the medico-legal outcome was decided against the physicians. The most common reasons for patient complaints were diagnostic error, deficient assessment, and failure to perform a test or intervention. Expert analysis of these cases determined the most common contributing factors for medico-legal action was failure to perform POCUS when indicated (7 cases, 47%); however, medico-legal action also resulted from diagnostic error, incorrect sonographic approach, deficient assessment, inadequate skill, inadequate documentation, or inadequate reporting.

Conclusions

Although the most common reason associated with the medico-legal action in these cases is failure to perform POCUS when indicated, inappropriate use of POCUS may lead to medico-legal action. Due to limitations in granularity of data, the exact number of civil-legal, College cases, and hospital complaints for each contributing factor is unavailable. To enhance patient care and mitigate risk for providers, POCUS should be carefully integrated with other clinical information, performed by providers with adequate skill, and carefully documented.

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has become a core diagnostic tool for many physicians [ 1 ]. Its portability, excellent safety profile, and ability to make important diagnoses in real-time helps expedite care. The importance of POCUS has been recognized by many undergraduate and post-graduate medical institutions, and it has seen planned or actual integration into core medical curricula [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Additionally, its safety and ability to enhance patient care has led to its endorsement by multiple major clinical societies [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Despite being an invaluable tool, there is a risk that the rapid uptake of POCUS may outpace development of best practices to safeguard both patients and providers.

Medico-legal analyses can help promote patient safety and improve the quality of healthcare delivery. By analyzing medico-legal cases, we can identify patterns of error, understand the root causes of adverse events, and develop strategies to prevent future occurrences [ 11 ].

The current POCUS medico-legal literature has not identified any cases where performing diagnostic POCUS has resulted in civil-legal action [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Instead, all cases have arisen from failure to perform POCUS when clinically indicated [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. These small studies are limited by sample size, non-comprehensive legal databases, and differences in legal systems between countries, leaving important questions about the medico-legal risk for physicians performing POCUS for Canadian physicians.

The objective of our study was to analyze the Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA) closed-case repository to identify medico-legal cases (civil-legal, college complaints, or hospital complaints) related to the use of POCUS. We describe the nature and frequency of medico-legal claims, identify common errors and contributing factors, and discuss strategies for mitigating medico-legal risks when performing POCUS.

In January 2023, the Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA), a not-for-profit mutual defense organization, represented over 107,000 physician members. The CMPA offers medico-legal support, advice, and education to physicians, and engages in safe medical care research using medico-legal data from its repository. The repository relies on physician members to voluntarily contact the CMPA and submit materials when seeking advice or support for medico-legal matters. We conducted a 10-year retrospective descriptive analysis of medico-legal cases related to diagnostic POCUS performed in a hospital setting. In this study, cases included civil-legal actions (class action legal cases were excluded), medical regulatory authority cases (College) and hospital complaints. A statistical data analyst searched all cases closed between January 1st, 2012 and December 31st, 2021. Prior to analysis, all cases were de-identified and reported at the aggregate level to ensure confidentiality for both patients and healthcare providers. This means that detailed descriptions of individual cases are not possible and may leave an unavoidable lack of granularity. The Advarra Institutional Review Board provided ethical approval for this study.

CMPA medical analysts, who are experienced registered nurses with training in medico-legal research, used standardized methods to code information retrieved from medico-legal cases, including the case information, patient characteristics, health conditions, complications, peer expert criticisms classified using the CMPA’s contributing factors framework [ 11 ], patient harm classified using an in-house classification of harms, and the court ruling or final regulatory authority or hospital decisions. Peer experts are physicians retained by the parties in a legal action to interpret and provide their opinion on clinical, scientific, or technical issues surrounding the care provided. Clinical coding was applied using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision, Canada (ICD-10-CA), the Canadian Classification of Health Interventions, and in-house CMPA coding. To reduce misclassification, nurse-analysts conducted regular quality assurance reviews of coding electronically and as a group.

Closed cases with sufficient information involved various physician specialties caring for patients undergoing diagnostic POCUS. Some cases involved more than one physician and more than one physician specialty per case.

Cases were extracted using word search for point of care ultrasound (see Appendix A for list of terms). We excluded cases involving radiologists, obstetricians performing obstetric ultrasounds, and cardiologists performing echocardiography from the extraction and a manual review excluded cases when POCUS was not the medico-legal issue in the case. A descriptive analysis of the selected cases included an analysis of the contributing factors identified by peer experts as well as analysis of the indications for POCUS, patient harm, care settings, geographical location of care, patient demographics, physician specialty and years in practice.

We report all variables with frequencies and proportions using SAS software, version 9.4 for all statistical analyses (SAS ® Enterprise Guide ® software, Version 9.4. Cary, North Carolina: SAS Institute Inc.; 2013).

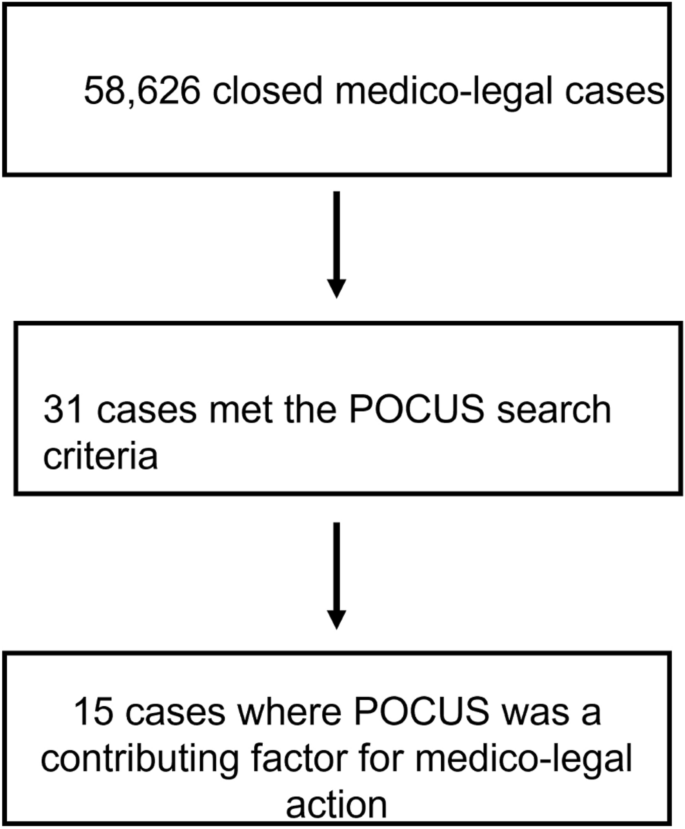

From 2012 to 2021, a total of 58,626 medico-legal cases were captured in the CMPA database. Of these, 31 cases met the database search strategy. POCUS was a contributing factor towards medico-legal action in 15/31 (48%) cases. Nine cases were college complaints, the rest were civil-legal actions (five) or hospital complaints. The medico-legal outcomes for physicians were decided against the physician in all 15 cases.

Patient demographics and outcomes

Ten of the 15 patients were female (67%). The age ranges for patients were: 0–18 years old (2, 13%), 19–29 (3, 20%), 30–49 (7, 47%), 50–64 (2, 13%), and 65–79 (1, 7%). Most cases occurred in the emergency department (13, 87%). Thirteen of the 15 cases (87%) resulted from healthcare related harm to the patient, with 2 cases (13.3%) resulting from non-clinical issues (e.g. documentation). Of the 13 patients with healthcare related harm, 5 patients died (33%). For the remaining patients, the harm classification was mild for 4 patients (26.7%), moderate for 2 patients (13%) severe for 1 patient (7%), and 1 patient experienced no harm (7%). See Appendix 2 for the definitions of patient harm.

The most common patient safety indicators were diagnostic error (12/15, 80%), contraindicated procedure or pharmacotherapy (2/15, 13%), and injury associated with healthcare (1/15, 7%). The most common reasons for patient complaints included diagnostic error (14, 93%), deficient assessment (12, 80%), and failure to perform a test or intervention (8, 53%) (Table 1 ).

Physician demographics

The distribution of specialties for physicians involved in the cases (n = 19) were: emergency medicine (9, 47%), resident physician (3,16%), family medicine (3, 16%), obstetrics and gynecology (1, 5%), internal medicine (1, 5%), general surgery (1, 5%), and diagnostic radiology (1, 5%). Note, cases where the POCUS provider was an obstetrician or radiologist were excluded from our search, however, these specialists may have been included in cases if they were listed as co-complainants. Eleven of 19 physicians (58%) were in practice 5 years of less; five of 19 physicians (26%) were in practice 11–20 years; three of 19 physicians (16%) were in practice 21–30 years. Nine cases (60%) occurred in large urban population centers (> 100,000 people), with 3 cases (20%) occurring in medium population centers (30,000 to 100,000 people), and 3 (20%) cases occurring in small population centers (less than 30,000 people).

Expert contributing factor analysis

Expert analysis identified the root cause of medico-legal action for each case. They found that in 7 cases POCUS was not performed when clinically indicated. In 8 cases, POCUS was performed but there was an issue with its application: in 2 cases, inadequate skill; in 1 case, an incorrect approach used (e.g. a surface POCUS instead of an invasive modality); in 1 case, deficient reporting; in 1 case, deficient documentation;, in 1 case, inappropriate use; in 1 case, misdiagnosis; in 1 case, the expert analysis was not recorded. The lack of granularity of the data limits the ability to report how many of the above cases were civil-legal cases, college complaints, or hospital complaints.

For cases involving a diagnostic error (12 cases), 6 (50%) were related to performing POCUS, and 6 (50%) were related to not performing POCUS. For cases of deficient assessment, in one case, the physician relied on serial POCUS exams, disregarding an important physical exam finding that should have prompted additional imaging. In 4 cases (36%) a misinterpretation of the POCUS led to the failure to perform an indicated test or intervention. Notably, whereas only 1 case had inadequate documentation listed as the cause of complaint from the patient or family members, peer expert criticism identified 11 cases where inadequate documentation contributed to the medico-legal outcome. One important note is that not all documentation issues were specific to POCUS; however, failure to document POCUS findings, and failure to use standardized wording for POCUS reports were identified as contributing factors by peer review.

The contributing factor analysis of 14 cases with criticisms related to patient care (not the 1 case related to documentation), identified provider factors in 13/14 case (93%), team factors in 13/14 cases (93%), and system factors in 3/14 cases (21%). The complete list of provider, team, and system factors identified are included in Table 2 ; however, the most common contributing factors included failure to perform a test or intervention, deficient assessment, and misinterpretation of a test. At the team level, these were documentation issues and communication breakdown with a patient. At a system level these were related to resource issues, and protocol, policy, or procedural issues. Of note, the system level issues that arose from lack of resources were not related to lack of POCUS machine access or lack of access to POCUS infrastructure (e.g. image archiving), but rather inadequate staffing of departments in a way that contributed to patient harm.

Interpretation

In this analysis of closed medico-legal cases in the CMPA repository we identified 15 cases where POCUS was a contributing factor towards medico-legal action. Almost half of the cases were due to physicians failing to perform POCUS when indicated. In contrast to previous literature that had not identified POCUS cases that resulted in a medico-legal action [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ], we found a number of cases where POCUS use resulted in a medico-legal action due to issues with provider skill, sonographic approach, reporting, documentation, misdiagnosis, and inappropriate use. All cases resulted in findings against the physician involved. Five cases involved patient death.

Contrasting our study to existing literature [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ] (which report civil-legal cases only), the increased number of medico-legal cases identified may be accountable by several factors. First, the CMPA repository is a comprehensive database capturing essentially all medico-legal cases against Canadian physicians, with data coded prospectively in a highly searchable way. Additionally, most of the cases were hospital or college complaints, which have a lower barrier to filing compared with civil litigation. This is important as this is the first study to examine hospital and college complaints, in addition to civil litigation. Thus, whereas patients and families may have felt POCUS was applied inappropriately and submitted a hospital or college complaint, it may not have met a threshold to proceed with civil litigation (Fig. 1 ).

Study flow diagram

Regardless, our study demonstrates an important reality for the twenty-first century acute care physician: failure to perform POCUS when indicated may result in medico-legal action. For some specialties and indications, POCUS may no longer be an adjunct to augment traditional bedside assessment but rather a core part of the diagnostic process itself. While POCUS infrastructure and expertise varies between different settings, as the evidence and use of POCUS grows, so too can the expectation that it is appropriately used when clinically indicated. This may be particularly relevant for specific use cases of POCUS with well-established diagnostic pathways including the Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) exam during trauma resuscitation, or its use to diagnosis undifferentiated shock [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. The excellent safety and diagnostic prowess of acute care POCUS has led to its endorsement by various societal guidelines [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ].

Despite increasing adoption of POCUS in acute care medicine, adequate training and skill is necessary for its safe implementation, and in this analysis was flagged as a contributing factor for medico-legal action in several cases. One systems level approach to POCUS education being implemented at multiple institutions is to teach ultrasound physics, knobology, and anatomy in parallel with traditional medical school curriculum to provide learners with a base skillset that can be built on during further training [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Then, specialty specific POCUS training with a focus on interpretation and synthesis can be taught during residency. Although this approach will help ensure future generations of physicians have base competency in POCUS, for clinicians in practice, alternative educational approaches should be considered. These include informal or formal instruction from colleagues with POCUS expertise to help develop core skills. Alternatively, continuing medical education opportunities like POCUS courses, conferences, rotations, or fellowships are an excellent resource, however, may not be feasible for many physicians in practice. Some societies have suggested processes for credentialing and privileging practicing physicians, which may be helpful roadmaps for interested clinicians [ 6 ].

In addition to helping clinicians obtain and interpret POCUS images, formalized training helps clinicians appropriately integrate POCUS findings with other clinical information. In fact, diagnostic errors, deficient assessments, and failure to perform other indicated tests or interventions were the most common reasons for patient complaints in our study, indicating a failure to properly integrate POCUS into the diagnostic workup of patients. Ideally, POCUS findings should be integrated into patient care with a ‘Bayesian mindset’, meaning that the positive or negative finding on POCUS helps change the post-test probability of a pathology being present. This contrasts with an oversimplified view of POCUS where the presence or absence of findings on POCUS dictates whether a disease is present. This dichotomized view of POCUS is potentially dangerous, and in our experience seen more with novice POCUS practitioners. The visual nature of the medium may lend itself to a ‘seeing is believing’ phenomenon, which can lead some clinicians to place inappropriate weight on the POCUS findings, disregarding other competing clinical information.

Inappropriate integration of POCUS into practice may also result from a failure to understand the test characteristics for POCUS in that population. For instance, FAST scan has high specificity (> 98%) to detect intraperitoneal free fluid, however only moderate sensitivity (70–90%) with test characteristics varying between operators [ 18 , 21 , 22 ]. For a trauma patient with a very high pre-test probability for intrabdominal hemorrhage (e.g. 80%), even with a negative FAST scan (assume sensitivity of 70%), the post-test chance of intrabdominal hemorrhage is 55%. Overreliance on POCUS and failure to integrate other clinical information is a crucial pitfall to avoid.

Inadequate documentation led to medico-legal action and was a major theme in the contributing factor analysis. If a POCUS is performed, the indication, views acquired, findings, and interpretation should be recorded in the patient's chart. At a minimum, this should be written as a progress note or included as part of a consultation. A better practice, although not available at many centers, is to save images in an accessible archiving system, and then generate a written report to allow for accountability and communication between providers [ 23 , 24 ]. Ideal practice would have all archived scans undergo quality assurance by a POCUS expert, with the amended reports subsequently uploaded into a patient’s electronic medical record. The practice of "shadow" scans where results are communicated by verbal handover between providers is not acceptable and may expose physicians to medico-legal risk.

Future directions

Although this represents a preliminary analysis of Canadian medico-legal cases involving POCUS, we expect the number of medico-legal cases to grow in parallel with increased POCUS use across. A repeat analysis of this work in 5 or 10 years will be helpful to assess for evolving patterns in POCUS medico-legal risk. Furthermore, this study excluded procedural use of POCUS (e.g. central line insertion) which would be an important area for future research. Additionally, knowledge translation surrounding best practices in POCUS training, clinical integration, and documentation is needed to promote optimal POCUS use among physicians.

Limitations

There are several important limitations: the search terms used may not have retrieved all medico-legal cases related to POCUS. To address this, the CMPA will now prospectively identify POCUS cases to facilitate future research. We omitted granular clinical details from the cases to protect patient and physician privacy, however this limits the analysis of factors leading to poor patient outcomes. This was unavoidable and was done in close collaboration with the CMPA to adhere to their rigorous privacy mandates. We recognize that this leaves unanswered questions, but feel this study still provides actionable take homes to improve patient safety. Finally, we have not included procedural POCUS, as we would lack granularity to distinguish between medico-legal action from the procedure itself, or the POCUS use.

Although failing to perform POCUS when clinically indicated remains an important contributing factor for medico-legal action, in contrast to the existing published literature, we identified cases where the application of POCUS resulted in adverse medico-legal outcomes. Due to limitations in granularity of data, the exact number of civil-legal, College cases, and hospital complaints for each contributing factor is unavailable. Overall, these cases resulted from inadequate skill, misdiagnosis, incorrect approach, deficient patient assessment, and incomplete documentation. The thoughtful and deliberate integration of POCUS into diagnostic pathways will help mitigate risk while allowing patients to experience benefits of this powerful tool.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

Canadian Medical Protective Association

Focused assessment with sonography in trauma

Point-of-care Ultrasound

Arntfield RT, Millington SJ (2012) Point of care cardiac ultrasound applications in the emergency department and intensive care unit–a review. Curr Cardiol Rev 8(2):98–108

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Micks T, Braganza D, Peng S, McCarthy P, Sue K, Doran P et al (2018) Canadian national survey of point-of-care ultrasound training in family medicine residency programs. Can Fam Physician 64(10):e462–e467

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Steinmetz P, Dobrescu O, Oleskevich S, Lewis J (2016) Bedside ultrasound education in Canadian medical schools: a national survey. Can Med Educ J 7(1):e78-86

Ma IWY, Steinmetz P, Weerdenburg K, Woo MY, Olszynski P, Heslop CL et al (2020) The Canadian medical student ultrasound curriculum: a statement from the Canadian ultrasound consensus for undergraduate medical education group. J Ultrasound Med 39(7):1279–1287

Weill S, Picard DA, Kim DJ, Woo MY (2023) Recommendations for POCUS curriculum in Canadian undergraduate medical education: consensus from the inaugural Seguin Canadian POCUS Education Conference. POCUS J 8(1):13–18

Lewis D, Rang L, Kim D, Robichaud L, Kwan C, Pham C et al (2019) Recommendations for the use of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) by emergency physicians in Canada. CJEM 21(6):721–726

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bronshteyn YS, Anderson TA, Badakhsh O, Boublik J, Brady MBW, Charnin JE et al (2022) Diagnostic point-of-care ultrasound: recommendations from an expert panel. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 36(1):22–29

Ma IWY, Arishenkoff S, Wiseman J, Desy J, Ailon J, Martin L et al (2017) Internal medicine point-of-care ultrasound curriculum: consensus recommendations from the Canadian Internal Medicine Ultrasound (CIMUS) group. J Gen Intern Med 32(9):1052–1057

Arntfield R, Millington S, Ainsworth C, Arora R, Boyd J, Finlayson G et al (2014) Canadian recommendations for critical care ultrasound training and competency. Can Respir J 21(6):341–345

Meineri M, Arellano R, Bryson G, Arzola C, Chen R, Collins P et al (2021) Canadian recommendations for training and performance in basic perioperative point-of-care ultrasound: recommendations from a consensus of Canadian anesthesiology academic centres. Can J Anaesth 68(3):376–386

McCleery A, Devenny K, Ogilby C, Dunn C, Steen A, Whyte E et al (2019) Using medicolegal data to support safe medical care: a contributing factor coding framework. J Healthc Risk Manag 38(4):11–18

Reaume M, Farishta M, Costello JA, Gibb T, Melgar TA (2021) Analysis of lawsuits related to diagnostic errors from point-of-care ultrasound in internal medicine, paediatrics, family medicine and critical care in the USA. Postgrad Med J 97(1143):55–58

Solomon L, Emma M, Gibbons LM, Kusulas MP (2022) Current risk landscape of point-of-care ultrasound in pediatric emergency medicine in medical malpractice litigation. Am J Emerg Med 58:16–21

Stolz L, O’Brien KM, Miller ML, Winters-Brown ND, Blaivas M, Adhikari S (2015) A review of lawsuits related to point-of-care emergency ultrasound applications. West J Emerg Med 16(1):1–4

Russ B, Arthur J, Lewis Z, Snead G (2022) A review of lawsuits related to point-of-care emergency ultrasound applications. J Emerg Med 63(5):661–672

Blaivas M, Pawl R (2012) Analysis of lawsuits filed against emergency physicians for point-of-care emergency ultrasound examination performance and interpretation over a 20-year period. Am J Emerg Med 30(2):338–341

Nguyen J, Cascione M, Noori S (2016) Analysis of lawsuits related to point-of-care ultrasonography in neonatology and pediatric subspecialties. J Perinatol 36(9):784–786

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Netherton S, Milenkovic V, Taylor M, Davis PJ (2019) Diagnostic accuracy of eFAST in the trauma patient: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CJEM 21(6):727–738

Vieillard-Baron A, Millington SJ, Sanfilippo F, Chew M, Diaz-Gomez J, McLean A et al (2019) A decade of progress in critical care echocardiography: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med 45(6):770–788

Stickles SP, Carpenter CR, Gekle R, Kraus CK, Scoville C, Theodoro D et al (2019) The diagnostic accuracy of a point-of-care ultrasound protocol for shock etiology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CJEM 21(3):406–417

Lee C, Balk D, Schafer J, Welwarth J, Hardin J, Yarza S et al (2019) Accuracy of focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) in disaster settings: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 13(5–6):1059–1064

Stengel D, Leisterer J, Ferrada P, Ekkernkamp A, Mutze S, Hoenning A (2018) Point-of-care ultrasonography for diagnosing thoracoabdominal injuries in patients with blunt trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12(12):CD012669

PubMed Google Scholar

Aspler A, Wu A, Chiu S, Mohindra R, Hannam P (2022) Towards quality assurance: implementation of a POCUS image archiving system in a high-volume community emergency department. CJEM 24(2):219–223

Lewis D, Alrashed R, Atkinson P (2022) Point-of-care ultrasound image archiving and quality improvement: not “If?” or “When?”…but “How?” and “What Next…?” CJEM 24(2):113–114

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anna MacIntyre for her contributions to the retrieval of cases from the CMPA database.

No funding was obtained for this research.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Critical Care, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada

Ross Prager & Robert Arntfield

London Health Sciences Centre, Rm # D2-528, 800 Commissioners Rd. E., London, ON, N6A 5W9, Canada

Ross Prager

Department of Medicine, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada

Department of Safe Medical Care Research, Canadian Medical Protective Association, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Gary Garber, P. J. Finestone, Cathy Zang & Rana Aslanova

Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada

Gary Garber

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design, analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, and revisions of this study.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ross Prager .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The Advarra Institutional Review Board provided ethical approval for this study.

Consent for publication

No patient information is provided in the manuscript.

Competing interests

None of the authors have relevant competing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

CMPA repository search strategy.

Word search terms:

Bedside ultrasound

Bedside u/s

Point of care

Point of care ultrasound

Point of care u/s

POC ultrasound

Patient harm classification definitions.

The harm classification distinguishes healthcare-associated harm from other medical-legal matters through a reliable method. The system categorizes harm arising from healthcare delivery either from an inherent risk of investigation or treatment, or from three types of patient safety incidents: harmful incident, no harm incident (i.e. incident occurred but did not lead to harm), or a near miss.

Harm classification table.

Based on ASHRM’s Healthcare Associated Preventable Harm Level Classification and Classification of patient safety incidents in primary care.

† Relates to a No harm incident: a patient safety incident that reached a patient but resulted in no discernable harm.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Prager, R., Wu, D., Garber, G. et al. Medico-legal risks of point-of-care ultrasound: a closed-case analysis of Canadian Medical Protective Association medico-legal cases. Ultrasound J 16 , 16 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-024-00364-7

Download citation

Received : 25 July 2023

Accepted : 11 February 2024

Published : 23 February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13089-024-00364-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Medcio-legal

- Patient safety

- Point-of-care ultrasound

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Medico-Legal Findings, Legal Case Progression, and Outcomes in South African Rape Cases: Retrospective Review

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Gender and Health Research Unit, Medical Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa, School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Affiliation School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Affiliation Tshwaranang Legal Advocacy Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa

Affiliation Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, Johannesburg, South Africa

Affiliation Gender and Health Research Unit, Medical Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa

- Rachel Jewkes,

- Nicola Christofides,

- Lisa Vetten,

- Ruxana Jina,

- Romi Sigsworth,

- Lizle Loots

- Published: October 13, 2009

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000164

- Reader Comments

Health services for victims of rape are recognised as a particularly neglected area of the health sector internationally. Efforts to strengthen these services need to be guided by clinical research. Expert medical evidence is widely used in rape cases, but its contribution to the progress of legal cases is unclear. Only three studies have found an association between documented bodily injuries and convictions in rape cases. This article aims to describe the processing of rape cases by South African police and courts, and the association between documented injuries and DNA and case progression through the criminal justice system.

Methods and Findings

We analysed a provincially representative sample of 2,068 attempted and completed rape cases reported to 70 randomly selected Gauteng province police stations in 2003. Data sheets were completed from the police dockets and available medical examination forms were copied. 1,547 cases of rape had medical examinations and available forms and were analysed, which was at least 85% of the proportion of the sample having a medical examination. We present logistic regression models of the association between whether a trial started and whether the accused was found guilty and the medico-legal findings for adult and child rapes. Half the suspects were arrested ( n = 771), 14% (209) of cases went to trial, and in 3% (31) of adults and 7% (44) of children there was a conviction. A report on DNA was available in 1.4% (22) of cases, but the presence or absence of injuries were documented in all cases. Documented injuries were not associated with arrest, but they were associated with children's cases (but not adult's) going to trial (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] for having genital and nongenital injuries 5.83, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.87–18.13, p = 0.003). In adult cases a conviction was more likely if there were documented injuries, whether nongenital injuries alone AOR 6.25 (95% CI 1.14–34.3, p = 0.036), ano-genital injuries alone (AOR 7.00, 95% CI 1.44–33.9, p = 0.017), or both nongenital and ano-genital injuries (AOR 12.34, 95% CI 2.87–53.0, p = 0.001). DNA was not associated with case outcome.

Conclusions

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to show an association between documentation of ano-genital injuries, trials commencing, and convictions in rape cases in a developing country. Its findings are of particular importance because they show the value of good basic medical practices in documentation of injuries, rather than more expensive DNA evidence, in assisting courts in rape cases. Health care providers need training to provide high quality health care responses after rape, but we have shown that the core elements of the medico-legal response require very little technology. As such they should be replicable in low- and middle-income country settings. Our findings raise important questions about the value of evidence that requires the use of forensic laboratories at a population level in countries like South Africa that have substantial inefficiencies in their police services.

Please see later in the article for the Editors' Summary

Citation: Jewkes R, Christofides N, Vetten L, Jina R, Sigsworth R, Loots L (2009) Medico-Legal Findings, Legal Case Progression, and Outcomes in South African Rape Cases: Retrospective Review. PLoS Med 6(10): e1000164. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000164

Academic Editor: Chris Beyrer, John Hopkins University, United States of America

Received: January 27, 2009; Accepted: September 3, 2009; Published: October 13, 2009

Copyright: © 2009 Jewkes et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: Funding was provided by the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights, the Open Society Foundation, the Ford Foundation and the Medical Research Council of South Africa. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Editors' Summary

Sexual violence has significant short- and long-term mental and physical health consequences for the victim. Estimates of how common rape is vary within and between countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between 1% and 12% of women aged 15 or over have experienced sexual violence by a nonpartner. It has also been used as a weapon of war.

The WHO recognises that rape may be committed by a spouse, partner, or acquaintance as well as a stranger, that men can be victims as well as perpetrators, and that coercion need not be physical. It advocates preventing sexual violence through better support for victims, legal and policy changes, educational programmes, and campaigns to change attitudes, and better health care services and training for health care workers.

Health services for victims of rape have two important roles: to assist the victim and to gather evidence for the police and courts. Nonetheless, health services for victims of rape are often poor. Over the last decade, the South African government has taken steps to reduce particularly high rates of sexual violence by broadening the legal definition of rape and improving health services.

Why Was This Study Done?

Previous studies into how useful expert medical evidence is for the police and courts have focused almost exclusively on high-income countries. It is not clear what interventions work best in countries with fewer resources. The researchers wanted to know the impact of medical evidence on how the South African criminal justice system handled cases of rape and attempted rape.

What Did the Researchers Do and Find?

The authors analysed data from police and court files of 1,547 cases of rape or attempted rape first reported in 2003 to a random sample of police stations in Gauteng province, South Africa. They looked for associations between case data and the arrest, charge, trial, and conviction or acquittal of the alleged perpetrator. They included only cases that were closed when they collected data in 2006 and only cases that contained a record of a medical examination of the victim. The researchers used South Africa's then legal definition of rape as “intentional and unlawful vaginal sex with woman without consent.” They analysed cases involving adults and children (aged 0–17 years) separately. They found that the overall conviction rate was very low, with only 3% of adult cases and 7.4% of children's cases resulting in a guilty verdict. Many cases were dropped at each stage of the legal process and DNA evidence was often not collected or, if collected, not analysed. DNA reports were rarely available for the courts. Injuries were not associated with arrests for either adult or children's cases; an arrest took place in 40% of cases without injuries. Child cases were more likely to come to trial if injuries were present, although a guilty verdict was not more likely. The reverse was true in adult cases: the presence or absence of injury was not linked to cases being brought to trial, but if injuries were present, whether genital, nongenital, or both, a conviction was more likely.

What Do These Findings Mean?

One limitation of the research is that the researchers identified statistical associations of events, but this does not prove that one event caused the other. Other possible limitations of the study are that the researchers had access only to cases closed by the police, which may have biased their results, and the quality of the recorded data was very variable. In addition, the research did not consider other factors that may have affected case outcomes, such as how witnesses are perceived in court.

The system to collect and analyse DNA was rarely effective in making evidence available to the courts. It is known from other countries with effective systems that DNA evidence is of no value if the basis of defence is consent; for instance in cases where the accused is an intimate partner of the victim. Injuries appear not to be necessary to secure a conviction but may be seen as useful by the South African courts in corroborating the victim's testimony, at least in adult cases.

The authors conclude that in poor countries, training for nurses and/or doctors who act as forensic medical examiners in how to record injuries and present their evidence in court will be more effective than investing in costly systems for DNA analysis. However, they argue that in South Africa, as a middle-income country with a high proportion of nonintimate partner rapes, there would be benefit in improving the system to collect and analyse DNA evidence rather than abandoning it entirely.

Additional Information

Please access these Web sites via the online version of this summary at http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000164 .

- Further information on rape in South Africa is available from the Tshwaranang Legal Advocacy Centre

- Information on rape is also available from the Rape Crisis Cape Town Trust

- Emergency rape information, facts about rape, events, legal services, and medical care can be found at the Speakout Web site

- The World Health Organization publishes a factsheet on sexual violence , a report on violence and health , as well as guidelines on medico-legal care for victims of sexual violence

Introduction

In 2008 the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1820 (2008), which declared rape to be a threat to global security—an act recognising that rape violates its victims' human rights and has particularly destructive social consequences. The Council also recognised that rape may cause considerable physical and psychological morbidity. Health systems have a critical role in responses to rape, yet in most countries the health sector response is underdeveloped [1] . Post-rape services generally receive few resources, service providers often lack specific training for and confidence in examining victims and interpreting their findings for the courts, and the health needs of victims often remain unmet [2] , [3] . In most countries rape services need resources and development, and research has a valuable role to play in guiding efforts to appropriately focus post-rape health services.

Expert medical evidence is widely used in rape cases, but its contribution to the progression of cases through the legal system and to legal case outcomes is unclear. A recent review [2] found 35 studies exploring the association, all but two from high-income countries, and two others have since been published. In just two studies, both from the United States, having a documented ano-genital injury was associated with filing charges [4] , [5] . Thirteen studies examined the association between the documentation of bodily injuries generally and case outcomes, with only two studies from the United States [6] , [7] and one from Canada [8] finding an association. Many of the studies were very small and dated, which influenced the analyses performed and power thereof [2] .

South Africa has an especially high prevalence of rape [9] , and as such, it is a particularly important context in which to conduct research on health sector responses to rape. Although in this country these responses have historically been poor, in the last decade there have been great efforts for improvement with a new national policy on sexual assault care [10] and clinical management guidelines [11] . The policy includes offering HIV testing and the provision of postexposure prophylaxis for HIV to rape survivors. There have been many different initiatives to train health providers in the provision of post-rape health care and forensic medical examination, which have culminated in the development of a national curriculum [12] . There have also been many efforts to improve the environment of rape facilities, including by identifying and furnishing dedicated rape care rooms. A forensic kit for collecting evidence, chiefly for genotyping, has been in use since 2000 and its completion is a standard part of the medical forensic examination [10] , [13] . The forensic kit enables collection of material that can form part of the evidence presented in court, as in rape cases medical evidence consists of both the observations about the victim at the time of the medical examination (including her or his physical and emotional state and sobriety), observations of injuries on her or his body generally and in the ano-genital region, and results of analysis of specimens taken for DNA. Examination findings are usually presented by the medical examiner (doctor or nurse) in person in a court room as an expert witness, whose testimony consists of the description of these observations and their interpretation. The DNA results are presented by an analyst from the Forensic Science Laboratory. The South African legal system is an adversarial system based on Roman Dutch law.

Given the growth of initiatives to strengthen the post-rape health care and the dual role of the health sector in providing care for victims as well as collection of evidence to assist the courts, it is important to understand the contribution of forensic medical evidence and the role of DNA evidence in case outcomes. To our knowledge, these two considerations have not previously been explored in a developing country. This article reports findings of a study that aimed to describe the processing of rape cases by South African police and courts and the association between medico-legal findings and case progression through the criminal justice system.

Ethics approval was given by the University of Witwatersrand, Faculty of Health Sciences Ethics Committee.

In terms of South African law from 1959 to 2007, rape was defined as occurring when a man had “intentional & unlawful vaginal sex with woman without consent,” and anal and oral penetration without consent were deemed “indecent assaults.” In December 2007 this definition was changed to include anal and oral penetration and encompassed the rape of men. This article presents a study of legally defined rape, based on a provincially representative sample of cases of rape and attempted rape opened at Gauteng province police stations between 00:00 on 1 January 2003 and 23:59 on 31 December 2003, and which had been closed by the police at the time of data collection in 2006 [14] .

A total of 11,926 rapes were reported at the 128 police stations in the province that year. A sample was drawn for the study using a two-stage procedure. The first stage drew a random sample of 70 police stations using probability proportional to size, where size was based on the number of rape cases that year. Within each police station all the closed rape cases for the year were identified and a systematic sample of 30 dockets was selected (or all cases were taken if the number was less than 30). Dockets selected that were not available were not replaced. The proportion of dockets opened from which we were about to draw the sample was 70.1%. We were not able to ascertain how many dockets were unavailable because they were still open and how many were missing for other reasons. This procedure provided a sample of 2,068 cases for the study. If cases went to court, we obtained court records from both High Courts in the province, as well as all 30 magistrates' courts.

The police dockets included the witness statements, police investigation diary, the form on which the findings of the medical examination were documented by the medical examiner, and any other reports, including any from the Forensic Science Laboratory (if available). Data were abstracted by a team of trained fieldworkers using a standardised data coding sheet. Information gathered included the details of the complainant (age, race, occupation, in the case of children the carer), the circumstances of the rape (when it occurred, where, what the victim was doing, use of weapons, victim responses after the rape), information on the suspect (age and relationship to victim), and on the case outcome. Medico-legal forms found in dockets were copied verbatim onto a blank form in the data capture sheet by the fieldworker, whereas those found in court records were photocopied. The information from these was abstracted onto a form for data entry by health professionals on the study team (NC, RJ, and RJ).

Permission to review closed rape dockets was obtained from the police nationally, provincially, and at the stations. Court documents are a matter of public record. No identifying information related to rape victims was collected during fieldwork and any found on documents that were photocopied was erased.

Data Analysis

The analysis was undertaken using Stata 10 and the svy commands used to take into account the structure of the sample. All cases without a medico-legal form, including those for attempted or suspected rape, were excluded from the analysis. Among these, no medical examination was done in 250 cases (50%), in three cases the form had been destroyed with court records, and in a further 252 the reason for nonavailability was unknown. Sixteen cases were dropped because very basic information was unavailable. The remaining 1,547 cases were analysed (85% of those that may have had medical examinations). The analysis is presented according to the age group of the victim (0–17 y and ≥18 y), because the variables operated differently in different age groups. We examined the findings for the 0–11-y-old and 12–17-y-old age groups separately, but combined them because no additional information was gained by their separation.

For Table 1 , we calculated the number and proportion of the cases opened by the police where the perpetrator was arrested (or asked to appear in court), charged, brought to trial, found guilty of a sexual offence (rape, attempted rape, or indecent assault), and imprisoned. We calculated the proportion of the cases that had a forensic evidence kit completed, sent to laboratory, where the suspect's blood was drawn, and where a report on DNA was available from the Forensic Science Laboratory. We also calculated the proportion attaining the previous stage in this process that progressed to the next stage (attrition by stage). We compared the proportion of cases reaching each stage between adults and children using a Pearson Chi-squared test.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000164.t001

For Tables 2 and 3 , we calculated the column percentage or mean for variables according to whether the suspect was arrested or not, brought to trial, and convicted of a sexual offence. The variables presented in these tables are those potential confounding variables for the relationship between the medical evidence variables and the outcomes. The survey regression command was used to compare the ages of victim and perpetrator between the two subgroups. A Pearson Chi-squared test was used to compare the proportion of cases at each level of the variable between the two subgroups for categorical variables.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000164.t002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000164.t003

Potential confounders included those related to the circumstances of the rape and possibility of apprehending the rapist: the involvement of more than one perpetrator, the suspect having previous convictions, the suspect's age, and the victim–perpetrator relationship. Some variables that may have influenced the violence of the rape as well as those that might have been in keeping stereotypical myths about what constitutes a “real rape” were examined: whether the victim resisted physically or verbally, weapons, and abduction, and whether the case was reported within 72 h was included as it could influence detection of injury and the presence of DNA. As an indicator of the quality of the investigation we included whether the first report statement was taken by the police or not. This statement is taken from the first person who the victim told about the rape and is often used as corroboration of aspects of the account of events and the victim's emotional and physical state at the time.

Nongenital (or anal) injuries included incised wounds, lacerations, grazes, bruises, and areas of tenderness and observations are intended to include the whole body except the ano-genital region. Ano-genital injuries were defined as those that may have been found on the mons pubis, frenulum, clitoris, labia majora, labia minora, perineum, fossa navicularis, hymen, vagina, clitoris, or anus. The injuries recorded ranged from lacerations to bruising, redness, inflammation, or tenderness. The variable “injury to the genitals with a skin break” only included genital injury that took the form of an incised wound, scratch, abrasion or laceration, if bleeding was seen, or if there was scarring that was believed to be from injuries caused by the rape. This variable was examined as an indicator of somewhat greater severity of injury. A four-level injury variable was derived with the referent group being no injury, and comparison groups being nongenital injury only, genital injury with a skin break only, both nongenital and genital injuries with a skin break.

Six logistic regression models were built using the Stata 10 svylogit command to describe factors associated with there being an arrest, having the trial commence (among those arrested or asked to appear in court), and being found guilty of a sexual offence (among those going to trial). Models for adults and children are presented separately. For each model the variables in Tables 2 and 3 were considered and those associated with the outcome at p <0.1 were entered into the model with the victim's age and the four-level exposure variable for injury. For the models for conviction, the presence of a DNA report was included; this was not included for the earlier models as DNA analysis is often only completed on a prosecutor's request because a case is about to go to trial. Stepwise backwards elimination was used to reach the parsimonious model from the variables tested. The associations between the outcome and the injury (and DNA) variables are presented for each model, adjusted for age and in the trial models, having a first report statement taken, which significantly associated with the outcome ( p ≤0.05). No other tested variables were significantly associated in these models; these are presented in Table 4 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000164.t004

Table 1 shows the proportion of cases of rape reported to the police and reaching each stage of the criminal justice system process for adults and children. Although an arrest was made in almost half of cases, there was only a conviction for a sexual offence in 3% of adult and 7.4% of children's cases. Examining attrition by stage we see that a trial was commenced in only 27% of adult and 38% of child cases where the suspect was arrested and charged in court. Convictions for sexual offences were achieved in a similar proportion of adult and child cases (30% and 41%) commencing trial.

A forensic evidence kit was completed much more often in adults than children (91% versus 63%). Whereas children were much more likely than adults to present more than 72 h after the rape (17.8% versus 3.4%), kits were still not completed on 23.8% of children and 6.3% of adults presenting within 72 h. Completed kits were often not sent to the laboratory for analysis and, in 71.5% of cases that were prosecuted, the suspect's blood was never drawn. Even when blood was drawn, reports on DNA found were rarely available for the courts.

Some of the features of the adult cases are presented in Table 2 and of child cases in Table 3 , by whether the suspect was arrested, brought to trial, and convicted. Arrest was more common when older children were raped and there was a suggestion that convictions were more common when adult victims were older ( p = 0.07). Otherwise a victim's age was not associated with case outcomes.

Arrest was less likely in rapes of adults involving multiple perpetrators ( p = 0.0003), but otherwise there was no significant difference in this by outcome. The suspect's age was not associated with case outcome. In adult cases, there is some evidence that trials may have been more likely to start if there were previous convictions ( p = 0.08), but conviction for a sexual offence occurred less frequently in this group ( p = 0.05). Arrests in both adult and child cases were much more common if the accused was known to the victim ( p <0.0001).

There was no association between whether the victim resisted the rape or abduction and any of the outcomes, for adults or children. Abducted adult and child victims were less likely to see the suspect arrested, but if there was an arrest, the trial was more likely to commence in adult cases. Armed perpetrators were less likely to be arrested. In cases where there was both an arrest and a trial, a statement from the first witness was much more likely to be in the docket.

Injuries in adults and children did not appear to have any influence over arrests. A notable finding was the high proportion (approximately 40%) of cases where an arrest was effected in rape cases of adults and children where no injuries were described. In children, nongenital injuries were uncommon. In child cases, genital injuries were more often found in cases that were brought to trial. In adults, they were more prevalent in cases where there was a conviction. A DNA report was only available for ten adults and 12 children. There was a conviction in three adult cases and two child cases that had a DNA report. The DNA report more often it led to an acquittal when in five adult and five child cases the short tandem repeat (STR) profile did not match that of the suspect. A match did not assure conviction, the accused having been acquitted in three children's cases and one adult case where the profile did match.

There was no statistically significant association between the presence of injuries and whether the suspect was arrested in adult or child cases (models not shown). Table 4 shows the four multiple variable models for factors associated with going to trial and convictions for a sexual offence in adult and child cases. After an arrest, a trial was significantly more likely to commence in children with both nongenital and genital injuries causing a skin break and there was some evidence that documented genital injuries alone also increased the likelihood of a case going to trial. In children, convictions for sexual offences were not more common in cases where there was evidence of injury. In adults, on the other hand, finding injuries was not associated with case progression to trial. However, having nongenital or genital injury, and having both, were all strongly associated with a conviction. The presence of a DNA report was not associated with conviction in either age group.

We examined a subset of rape cases where there was a forensic medical examination of the victim and have shown a precipitous decline in the proportion of cases reaching each sequential stage in the criminal justice system, with suspects only being convicted in about one in 20 of the documented rape cases. We described a parallel decline in the proportion of cases in which the chain of activities were performed to enable specimens to be collected and sent to a laboratory so that a report on the presence and analysis of DNA would be potentially available for use in trials. Substantial flaws in the system were evident, with forensic evidence collection kits not always being completed, when indicated; those completed often not being sent to the laboratory for analysis; and the suspect's blood infrequently being drawn. As a result of this, DNA reports were almost never available to be used in court cases. Although DNA is often presented as a key to solving cases and convicting offenders, we have shown that when available, DNA more certainly led the courts to acquit [15] , usually because no match to the accused was established, although medical evidence of injuries may have been available. This is not a positive outcome for a rape complainant, but in a criminal justice system that determines cases on absence of reasonable doubt, it would establish “reasonable doubt” that the accused was the culprit and thus assist the court.

We have shown that the presence of ano-genital injuries was associated with children's cases going to trial, and in adult cases a conviction was very much more likely if injuries were documented. It is notable that in a quarter of child cases where there was a conviction there were no documented injuries, which was also the case in 10% of adult cases. These data confirm that the presence of injury is not essential for a conviction in rape cases in South Africa, but at the same time it seems to suggest that courts may like to use the presence of injuries, at least in adult cases, as corroboration of the victim's testimony.

The attrition of cases in the criminal justice system is similar to that found in previous research [16] , and our findings about the nonavailability of DNA confirms those of an earlier small case series [17] . In South Africa, considerable resources have been invested in establishing a system that potentially enables the use of DNA in rape cases, yet it has clearly not been operating properly. It seems that the police are not able to respond appropriately in sending kits to laboratories and ensuring blood is taken from suspects. The police not sending kits to the laboratory was not explained by failure to make an arrest or the police withdrawing the case, but depended primarily on which police station or district the case was opened in. In most cases where suspect's blood was sent to the laboratory the kits were still not analysed. In 2005 the South African Forensic Science Laboratories had backlogs of about 20,000 unanalysed kits [18] , a number proportionately somewhat similar to that reported in the United States, but they were much slower at completing analysis than the average time in the United States [19] . As a result, few kits sent to them are processed, and only children's kits are analysed routinely, rather than on a request from a prosecutor.

This study has shown that in this setting medical documentation of injury and expert testimony in court may have influenced case progression and outcomes. In some individual cases DNA may be of value, but when the system is viewed as a whole this is not evident. It seems likely that this is chiefly because health and police systems in South Africa simply do not work well enough to enable DNA and forensic evidence collection and analysis to realise its potential. Although we know that in some countries even where DNA and forensic evidence systems work more effectively, they are still not associated with a positive legal outcome [8] , as DNA is of no value if the basis of the defence is consent. Nonetheless we believe that as a middle-income country South African forensic laboratories are affordable and a high proportion of South African rape cases are not intimate partner rapes, therefore DNA has the potential to contribute. On the basis of current information, efforts should be made to improve the system and the proportion of cases in which DNA is available rather than dispensing with it entirely.

This study is, to our knowledge, the first from a developing country to examine the association between findings on medico-legal examination and rape case progression and outcomes. Its strengths are its size and the fact that it is based on a random sample of cases from a broad geographic region. There may be limitations to the generalisablity of the findings since we only had access to closed cases and are not sure what proportion of eligible dockets were available for the sample or what biases could have ensued from this. The study relied on routine data, which are often flawed. We enhanced the validity of case outcomes data by using data from courts as well as the dockets. We are aware that the quality of documentation of the dockets and medical findings was very variable, but since this is what is used in the criminal justice system it is still valid to see how it may be associated with the progression of cases. In the analysis here we have only adjusted for a small set of potential confounding factors. We recognise that there could have been other factors influencing whether cases go to trial and convictions, notably how witnesses come across in court, willingness to accept children's testimony in court, and bias from judges. Further research with large datasets is needed to explore these areas in more detail.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to show an association between documentation of ano-genital injuries, trials commencing, and convictions in rape cases in a developing country. Its findings are of particular importance because they point to the value of good basic, forensic medical practices in assisting courts in rape cases. Health care providers need to be trained to provide high quality health care responses after rape, and we have shown that the core elements of the medico-legal response require very little technology. As such they should be replicable in low- and middle-income country settings, providing forensic medical examiners are trained in examination and documentation of injuries, and the presentation and interpretation of findings in court. Our findings raise important questions about the value of evidence that requires the use of forensic laboratories at a population level in countries like South Africa that have substantial inefficiencies in their police services. They suggest that in a resource constrained setting far more benefit may be accrued to rape victims and the criminal justice system by establishing policy, guidelines, and training for forensic medical examiners (be they nurses or doctors) and ensuring that they are equipped to provide good basic health care, including the forensic medical examination, than by focusing on complex and expensive systems to allow for DNA analysis. Further research is needed to deepen understandings of the use of medical evidence in court in a range of settings, and more health systems research is needed in both developed and developing countries to evaluate health systems interventions in post-rape care and their impact on victim/survivor health outcomes as well as the processes of justice.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the South African Police Services for giving us access for the study; Olivia Dunseith and Collet Ngwane who supervised fieldwork and the fieldworkers; Jonathan Levin for drawing the sample; and Samuel Manda for statistical review of the paper.

Author Contributions

ICMJE criteria for authorship read and met: R Jewkes, N Christofides, L Vetten, R Jina, R Sigsworth, L Loots. Agree with the manuscript's results and conclusions: R Jewkes, N Christofides, L Vetten, R Jina, R Sigsworth, L Loots. Designed the experiments/the study: R Jewkes, N Christofides, L Vetten, R Jina, R Sigsworth. Analyzed the data: R Jewkes, L Vetten, R Sigsworth. Collected data/did experiments for the study: R Jewkes, L Vetten, R Sigsworth, L Loots. Wrote the first draft of the paper: R Jewkes. Contributed to the writing of the paper: N Christofides, L Vetten, R Jina. Contributed to data coding of medico-legal forms: N Christofides. Principal investigator: L Vetten. Developed the data schedule collecting court information: L Vetten.

- 1. Jewkes R, Sen P, Garcia Moreno C (2002) Sexual violence. In: Krug EG, Mercy J, Zwi A, Lozano R, editors. World Health Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 148–181.

- 2. Du Mont J, White D (2007) The uses and impacts of medico-legal evidence in sexual assault cases: a global review. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

- 3. Wang SK, Rowley E (2008) Rape: responses from women and health providers. Geneva: Sexual Violence Research Initiative, World Health Organisation.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 5. Lindsay SP (1998) An epidemiologic study of the influence of victim age and relationship to the suspect on the results of evidentiary examinations and law enforcement outcomes in cases of reported sexual assault [PhD dissertation]. San Diego: San Diego State University.

- 10. Department of Health (2005) National sexual assault policy. Pretoria: National Department of Health.

- 11. Department of Health (2004) National management guidelines for sexual assault care. Pretoria: National Department of Health.

- 12. Jina R, Jewkes R, Christofides N, Loots L, editors. (2008) Caring for survivors of sexual assault. A training programme for health care providers in South Africa. Pretoria: Department of Health.

- 13. Biology Training Section (2000) Evidence collection kits: the new series of ECK for biological evidence. Pretoria: DNA Unit SAPS Forensic Science Laboratory.

- 14. Vetten L, Jewkes R, Fuller R, Christofides N (2008) Tracking justice: the attrition of rape cases through the criminal justice system in Gauteng. Johannesburg: Tshwaranang Legal Advocacy Centre.

- 16. Sidiropoulos E (1998) South Africa survey 1997/98. Johannesburg: South African Institute of Race Relations.

- 17. Blass L (2004) The responses of the criminal justice system to sexual violence crimes in the Kathorus region. South Africa. Johannesburg: Centre for Applied Legal Studies, University of the Witswatersrand.

- 18. Jina R (2006) Assessing the use of sexual assault evidence collection kits from six provinces in South Africa [unpublished MMed thesis]. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand.

- 19. Lovrich NP, Pratt TC, Gaffney MJ, Johnson CL, Asplen CH, et al. (2003) National forensic DNA study report. Pullman (Washington): Division of Governmental Studies and Services, Washington State University; Tacoma (Washington): Smith Alling Lane, P.S. Report No: 203970.

Advertisement

Medico-Legal Issues Related to Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Literature Review Including the Indian Scenario

- Review Article

- Published: 30 March 2021

- Volume 55 , pages 1286–1294, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Satvik Pai ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3621-150X 1

1617 Accesses

8 Citations

Explore all metrics

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are commonly performed surgeries worldwide. The number of joint replacement surgeries being performed has increased considerably over the past two decades, but it has also seen an increase in litigation associated with it. The purpose of our study was to review and consolidate literature regarding medico-legal issues pertaining to THA and TKA cases. We looked at the causes of litigation, medico legal aspects of pre-operative requirements, optimisation of medical condition, indications and contraindications for arthroplasty, informed consent, implants, mixing of components from different manufacturers and post-operative rehabilitation. We also wanted to analyse available literature and legal proceedings regarding these cases in India specifically.

Similar content being viewed by others

Litigation analysis of medical damage after total knee arthroplasty: a case study based on Chinese legal database in the past ten years

Shuai Liu, Jilong Zou, … Shuo Geng

Litigation after primary total hip and knee arthroplasties in France: review of legal actions over the past 30 years

Grégoire Rougereau, Thibaut Marty-Diloy, … Philippe Boisrenoult

Knee arthroplasty and lawsuits: the experience in France

Emmanuel Gibon, Thierry Farman & Simon Marmor

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are commonly performed surgeries worldwide. The number of joint replacement surgeries being performed has increased considerably over the past two decades, but it has also seen an increase in litigation associated with it [ 1 ]. In fact orthopaedic adult reconstruction subspecialists are sued for alleged medical malpractice at a rate over twice that of the physician population as a whole [ 2 ]. A survey of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons found that 78% of responding surgeons had been named as a defendant in at least one lawsuit alleging medical malpractice [ 3 ]. The purpose of our study was to review and consolidate literature regarding medico-legal issues pertaining to THA and TKA cases. With respect to THA, TKA cases we looked at the causes of litigation, medico-legal aspects of pre-operative requirements, optimization of medical condition, indications and contraindications for arthroplasty, informed consent, implants, mixing of components from different manufacturers and post-operative rehabilitation. We also wanted to analyse available literature and legal proceedings regarding these cases in India specifically.

Materials and Methods

An extensive literature search was conducted to identify studies pertaining to medico-legal issues in relation to total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA). The electronic databases of PubMed and Cochrane Library were explored using the following search terms and Boolean operators: ‘medico-legal’ OR ‘lawsuit’ OR ‘malpractice’ OR ‘litigation’ AND ‘total hip arthroplasty’ OR ‘total knee arthroplasty’ OR ‘total hip replacement’ OR ‘total knee replacement’ OR ‘THA’ OR ‘TKA’. No restriction in publication date was applied. Manuscript language was restricted to English. In addition, a comprehensive search of reference lists of all identified articles was conducted to find additional studies. Information about specific medico-legal proceedings involving THA/TKA cases in Indian legal courts, state and national consumer dispute redressal forums, and state medical councils were obtained from different books having compendium of medico-legal judgements.

Causes for Litigation

It is important to know the causes of litigation and common allegations in malpractice lawsuits involving hip and knee arthroplasty, so that measures can be taken to prevent such complications occurring and the orthopaedic surgeon can be better prepared in the event of such complications happening. Patterson et al. [ 4 ] analysed 115 malpractice claims filed for alleged neglectful primary and revision THA surgeries. They found that in primary cases, nerve injury (“foot drop”) was the most frequent allegation with 27 claims. Negligent surgery causing dislocation was alleged in 18 and leg length discrepancy in 14. Medical complications were also reported, including three thromboembolic events and six deaths. In revision cases, dislocation and infection were the most common source of suits. The data pertaining to causes of litigation following THA in various studies is represented in Table 1 . Patterson et al. [ 5 ] also studied the malpractice claims filed for alleged neglectful primary and revision TKA surgeries. The analysed 69 primary and eight revision TKAs which were involved in malpractice lawsuits and found that the most frequent factor leading to lawsuits for primary TKA was chronic pain or dissatisfaction in 12 cases, followed by nerve palsy in eight, postoperative in-hospital falls in five, and deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism in three. Medical complications included acute respiratory distress syndrome, cardiac arrest, and decubitus ulcers. Contracture was most common after revision TKA (three of eight cases). They concluded that pre-operative counselling regarding the risks of incomplete pain relief could reduce substantially the number of suits relating to primary TKAs. The data pertaining to causes of litigation following TKA in various studies is represented in Table 2 .