Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity

Meg Riordan, Ph.D., is the chief learning officer at The Possible Project, an out-of-school program that collaborates with youth to build entrepreneurial skills and mindsets and provides pathways to careers and long-term economic prosperity. She has been in the field of education for over 25 years as a middle and high school teacher, school coach, college professor, regional director of N.Y.C. Outward Bound Schools, and director of external research with EL Education:

Although critical thinking often defies straightforward definition, most in the education field agree it consists of several components: reasoning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking, plus analysis and evaluation of information, such that multiple sides of an issue can be explored. It also includes dispositions and “the willingness to apply critical-thinking principles, rather than fall back on existing unexamined beliefs, or simply believe what you’re told by authority figures.”

Despite variation in definitions, critical thinking is nonetheless promoted as an essential outcome of students’ learning—we want to see students and adults demonstrate it across all fields, professions, and in their personal lives. Yet there is simultaneously a rationing of opportunities in schools for students of color, students from under-resourced communities, and other historically marginalized groups to deeply learn and practice critical thinking.

For example, many of our most underserved students often spend class time filling out worksheets, promoting high compliance but low engagement, inquiry, critical thinking, or creation of new ideas. At a time in our world when college and careers are critical for participation in society and the global, knowledge-based economy, far too many students struggle within classrooms and schools that reinforce low-expectations and inequity.

If educators aim to prepare all students for an ever-evolving marketplace and develop skills that will be valued no matter what tomorrow’s jobs are, then we must move critical thinking to the forefront of classroom experiences. And educators must design learning to cultivate it.

So, what does that really look like?

Unpack and define critical thinking

To understand critical thinking, educators need to first unpack and define its components. What exactly are we looking for when we speak about reasoning or exploring multiple perspectives on an issue? How does problem-solving show up in English, math, science, art, or other disciplines—and how is it assessed? At Two Rivers, an EL Education school, the faculty identified five constructs of critical thinking, defined each, and created rubrics to generate a shared picture of quality for teachers and students. The rubrics were then adapted across grade levels to indicate students’ learning progressions.

At Avenues World School, critical thinking is one of the Avenues World Elements and is an enduring outcome embedded in students’ early experiences through 12th grade. For instance, a kindergarten student may be expected to “identify cause and effect in familiar contexts,” while an 8th grader should demonstrate the ability to “seek out sufficient evidence before accepting a claim as true,” “identify bias in claims and evidence,” and “reconsider strongly held points of view in light of new evidence.”

When faculty and students embrace a common vision of what critical thinking looks and sounds like and how it is assessed, educators can then explicitly design learning experiences that call for students to employ critical-thinking skills. This kind of work must occur across all schools and programs, especially those serving large numbers of students of color. As Linda Darling-Hammond asserts , “Schools that serve large numbers of students of color are least likely to offer the kind of curriculum needed to ... help students attain the [critical-thinking] skills needed in a knowledge work economy. ”

So, what can it look like to create those kinds of learning experiences?

Designing experiences for critical thinking

After defining a shared understanding of “what” critical thinking is and “how” it shows up across multiple disciplines and grade levels, it is essential to create learning experiences that impel students to cultivate, practice, and apply these skills. There are several levers that offer pathways for teachers to promote critical thinking in lessons:

1.Choose Compelling Topics: Keep it relevant

A key Common Core State Standard asks for students to “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” That might not sound exciting or culturally relevant. But a learning experience designed for a 12th grade humanities class engaged learners in a compelling topic— policing in America —to analyze and evaluate multiple texts (including primary sources) and share the reasoning for their perspectives through discussion and writing. Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care about and connect with can ignite powerful learning experiences.

2. Make Local Connections: Keep it real

At The Possible Project , an out-of-school-time program designed to promote entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, students in a recent summer online program (modified from in-person due to COVID-19) explored the impact of COVID-19 on their communities and local BIPOC-owned businesses. They learned interviewing skills through a partnership with Everyday Boston , conducted virtual interviews with entrepreneurs, evaluated information from their interviews and local data, and examined their previously held beliefs. They created blog posts and videos to reflect on their learning and consider how their mindsets had changed as a result of the experience. In this way, we can design powerful community-based learning and invite students into productive struggle with multiple perspectives.

3. Create Authentic Projects: Keep it rigorous

At Big Picture Learning schools, students engage in internship-based learning experiences as a central part of their schooling. Their school-based adviser and internship-based mentor support them in developing real-world projects that promote deeper learning and critical-thinking skills. Such authentic experiences teach “young people to be thinkers, to be curious, to get from curiosity to creation … and it helps students design a learning experience that answers their questions, [providing an] opportunity to communicate it to a larger audience—a major indicator of postsecondary success.” Even in a remote environment, we can design projects that ask more of students than rote memorization and that spark critical thinking.

Our call to action is this: As educators, we need to make opportunities for critical thinking available not only to the affluent or those fortunate enough to be placed in advanced courses. The tools are available, let’s use them. Let’s interrogate our current curriculum and design learning experiences that engage all students in real, relevant, and rigorous experiences that require critical thinking and prepare them for promising postsecondary pathways.

Critical Thinking & Student Engagement

Dr. PJ Caposey is an award-winning educator, keynote speaker, consultant, and author of seven books who currently serves as the superintendent of schools for the award-winning Meridian CUSD 223 in northwest Illinois. You can find PJ on most social-media platforms as MCUSDSupe:

When I start my keynote on student engagement, I invite two people up on stage and give them each five paper balls to shoot at a garbage can also conveniently placed on stage. Contestant One shoots their shot, and the audience gives approval. Four out of 5 is a heckuva score. Then just before Contestant Two shoots, I blindfold them and start moving the garbage can back and forth. I usually try to ensure that they can at least make one of their shots. Nobody is successful in this unfair environment.

I thank them and send them back to their seats and then explain that this little activity was akin to student engagement. While we all know we want student engagement, we are shooting at different targets. More importantly, for teachers, it is near impossible for them to hit a target that is moving and that they cannot see.

Within the world of education and particularly as educational leaders, we have failed to simplify what student engagement looks like, and it is impossible to define or articulate what student engagement looks like if we cannot clearly articulate what critical thinking is and looks like in a classroom. Because, simply, without critical thought, there is no engagement.

The good news here is that critical thought has been defined and placed into taxonomies for decades already. This is not something new and not something that needs to be redefined. I am a Bloom’s person, but there is nothing wrong with DOK or some of the other taxonomies, either. To be precise, I am a huge fan of Daggett’s Rigor and Relevance Framework. I have used that as a core element of my practice for years, and it has shaped who I am as an instructional leader.

So, in order to explain critical thought, a teacher or a leader must familiarize themselves with these tried and true taxonomies. Easy, right? Yes, sort of. The issue is not understanding what critical thought is; it is the ability to integrate it into the classrooms. In order to do so, there are a four key steps every educator must take.

- Integrating critical thought/rigor into a lesson does not happen by chance, it happens by design. Planning for critical thought and engagement is much different from planning for a traditional lesson. In order to plan for kids to think critically, you have to provide a base of knowledge and excellent prompts to allow them to explore their own thinking in order to analyze, evaluate, or synthesize information.

- SIDE NOTE – Bloom’s verbs are a great way to start when writing objectives, but true planning will take you deeper than this.

QUESTIONING

- If the questions and prompts given in a classroom have correct answers or if the teacher ends up answering their own questions, the lesson will lack critical thought and rigor.

- Script five questions forcing higher-order thought prior to every lesson. Experienced teachers may not feel they need this, but it helps to create an effective habit.

- If lessons are rigorous and assessments are not, students will do well on their assessments, and that may not be an accurate representation of the knowledge and skills they have mastered. If lessons are easy and assessments are rigorous, the exact opposite will happen. When deciding to increase critical thought, it must happen in all three phases of the game: planning, instruction, and assessment.

TALK TIME / CONTROL

- To increase rigor, the teacher must DO LESS. This feels counterintuitive but is accurate. Rigorous lessons involving tons of critical thought must allow for students to work on their own, collaborate with peers, and connect their ideas. This cannot happen in a silent room except for the teacher talking. In order to increase rigor, decrease talk time and become comfortable with less control. Asking questions and giving prompts that lead to no true correct answer also means less control. This is a tough ask for some teachers. Explained differently, if you assign one assignment and get 30 very similar products, you have most likely assigned a low-rigor recipe. If you assign one assignment and get multiple varied products, then the students have had a chance to think deeply, and you have successfully integrated critical thought into your classroom.

Thanks to Dara, Patrick, Meg, and PJ for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Critical Thinking Student Wheel available from Mentoring Minds | review by The Curriculum Corner | This wheel is a great tool for lesson planning using Bloom’s Taxonomy!

- Our Mission

An Inside Look at Webb’s Depth of Knowledge

The creator of the well-known framework explains how it helps teachers evaluate the cognitive complexity of a task or assignment—and clears up some misconceptions about it.

Question: What is the 37th digit in the number pi? (No calculator or googling allowed!)

Coming up with the 37th digit of pi is a very difficult task. But it’s not a complex task. In our classrooms, it’s important that we know what makes a task complex versus difficult so that we can effectively address the rigor or depth of K–12 academic expectations. One of us (Norman Webb) developed the Depth of Knowledge (DOK) framework in the late 1990s precisely for this purpose: to categorize expectations and tasks according to the complexity of engagement required.

DOK provides a common language that can be used to determine the degree to which the complexity of cognitive engagement, explicit in academic standards, is being translated into appropriate learning opportunities and assessment tasks. Because today’s academic standards emphasize conceptual understanding and authentic application of disciplinary practice, evaluating complexity of engagement is more important than ever. This article explores how teachers and administrators can use DOK to work more efficiently, effectively, and purposefully when they design curriculum.

DOK IN THE CLASSROOM

In general, lessons and courses are anchored in academic standards. Even for coursework that is not standards-based, teachers design curriculum based on learning objectives. To use DOK in your practice, start by looking at the standards (or other learning objectives) that anchor a lesson. What is the complexity of cognitive engagement required for success? When interpreting a standard, you can use the full DOK definitions for a specific content area. These general key questions can also help:

DOK 1: Is the focus on recall of facts or reproduction of taught processes?

DOK 2: Is the focus on relationships between concepts and ideas or using underlying conceptual understanding?

DOK 3: Is the focus on abstract inference or reasoning, nonroutine problem-solving, or authentic evaluative or argumentative processes that can be completed in one sitting?

DOK 4: Is the focus at least with the complexity of DOK 3, but iterative, reflective work and extended time are necessary for completion?

Evaluating the complexity of an expectation or task. When using DOK to evaluate educational materials, think about the degree of processing of concepts and skills required. For example, recalling the names of the state capitals is a low-complexity task. Retrieving bits of information from memory requires a minimal degree of processing of concepts. Either it’s in there and can be accessed… or it’s not. Similarly, correctly executing a multistep protocol is a simple task: There are specific steps to follow, and the protocol is either completed correctly… or not. As another example, we may ask students to use the standard algorithm to add two three-digit numbers or to follow specific, ordered steps to properly focus a microscope.

In contrast, tasks that require abstract reasoning and nonroutine problem-solving are highly complex. For example, tasks that involve analyzing multiple alternative solutions with consideration of constraints and trade-offs or building original evidential arguments require significantly more processing of concepts and skills than do tasks that must be completed via recall.

For example, we may ask students to develop an engineering design solution to a problem they identify. We could have students write or present a research-based argument about what time school should start and end, taking into account different perspectives of students, families, and staff. Overall, complexity of cognitive engagement depends on multiple factors, including the degree of processing required, the degree of intricacies (interconnected parts), and the extent to which the work is concrete versus abstract.

Appropriate use of DOK differentiates difficulty from complexity. Although complex tasks (like analyzing alternative solutions or building an evidential argument) are likely to be difficult, many difficult tasks (like correctly following a multistep protocol or memorizing state capitals) are not complex. Overall, difficulty depends on multiple factors, including the amount of effort required, the opportunity for error, and the opportunity to learn. “What does a fossa eat?” is a very simple question. But for someone who has never had the opportunity to learn what a fossa eats, it is also a very difficult question—unanswerable, in fact.

Use of DOK can help ensure that tasks that are intended to be complex are, indeed, complex (and not just difficult). It is also important to recognize when difficulty is inherent to a task. For example, long division and use of standard English punctuation may be difficult, but they are also tasks that students are typically expected to master.

AVOIDING MISINTERPRETATIONS OF DOK

As DOK has become a widely used tool in the United States and beyond, a variety of misinterpretations have inevitably emerged. For example, a frequently reproduced and highly misleading graphic (known to some as “the DOK wheel” and to others as the “wheel of misfortune”) attributes verbs to the different levels of DOK. This graphic suggests that a verb can be used to determine the complexity of engagement required by an expectation or task.

For instance, according to this graphic, the verb identify indicates a DOK 1. That could surely work in some cases—imagine having students “identify the circle in a group of shapes.” But now imagine having students “identify a strategy for addressing attendance issues using data from multiple sources.” Obviously, the complexity of these two tasks is significantly different despite using the same verb. To determine complexity, we need to look beyond the verb and consider the full scope of an expectation or task.

Another common misrepresentation is seen in progression or stair-step models that depict DOK as a hierarchy like Bloom’s or Maslow’s. But learning does not necessarily progress “up” from simple to complex. Consider mathematics: We often have students work conceptually with an idea before we introduce a more simple, rote approach. For example, we typically have students work with manipulables and form conceptual constructs of the idea of area before we introduce the equation l x w = a .

If you have ever used project-based learning (PBL), you have likely seen that a student may dive into work on a DOK 3 problem only to discover a simultaneous need for a DOK 1 task, like looking up a definition or taking a measurement. In fact, the use of a complex problem to motivate a need-to-know for lower-complexity goals is a core rationale for use of PBL.

Misrepresenting learning as progressing from simple to complex can be harmful if students who struggle with low-complexity tasks are held back from the rich, engaging, complex educational opportunities that we know promote learning. Ensuring access to complex learning opportunities for all students is foundational to the equity-focused goals of standards-based systems.

Incorporating DOK into practice can start by using the simple questions included here to ensure clearly and commonly understood learning targets. Then, the same process can be applied to the questions, tasks, and prompts we use in lessons and assessments. By defining and naming the DOK of the different components, we can work with greater focus and intentionality to check that the complexity of engagement explicit within those learning targets is carried through in the classroom.

And, by the way, the 37th digit of pi is 4.

Webb's Depth of Knowledge

May 11, 2023

Explore Webb's Depth of Knowledge, a framework to analyze cognitive demand. Understand its four levels and how to apply them in educational settings.

Main, P (2023, May 11). Webb's Depth of Knowledge. Retrieved from https://www.structural-learning.com/post/webbs-depth-of-knowledge

What is Webb's Depth of Knowledge?

Webb's Depth of Knowledge (DOK) is a system designed to categorize activities based on the complexity of thinking required to complete them. It serves as a framework for educators to create more cognitively engaging and challenging tasks . DOK is essential for educators since it helps them to identify the cognitive demand of activities and make informed decisions on how to design effective learning experiences for their students.

The four levels of DOK range from simple recall to conceptual understanding and metacognition .

Webb's Depth of Knowledge is an essential tool for educators aiming to create an engaging and challenging learning experience for their students. It helps educators to design tasks that require students to engage in higher-order thinking and promote the complexity of thinking required to apply their understanding to the real world. With DOK, educators can focus on student learning and apply cognitive rigor to create activities that promote knowledge application and student success.

What are the 4 levels of Webb's Depth of Knowledge?

Webb's Depth of Knowledge (DOK) is a framework used by educators to categorize tasks and assignments based on the level of cognitive effort required to complete them. This framework provides a helpful tool for designing and evaluating tasks that require deeper thinking and understanding. DOK is particularly useful for standardized assessments, where tasks are structured to test various levels of rigor.

There are four levels of Webb's Depth of Knowledge, each building on the previous level and requiring greater levels of cognitive complexity. The first level is recall , which requires learners to simply recall information from memory. This may involve basic knowledge such as terms, definitions, or historical facts.

At the second level, learners must demonstrate understanding of a concept or skill. This includes activities such as explaining a concept, interpreting data to support a claim, or summarizing key ideas from a text.

The third level of DOK requires learners to apply their knowledge and understanding in different contexts. This may involve analyzing primary sources to make an argument, developing a research question, or creating a project that integrates multiple disciplines.

Finally, the fourth level of DOK requires learners to engage in critical thinking , synthesize information and evaluate arguments. This includes activities such as evaluating sources of information, synthesizing information from multiple sources to create new knowledge, developing original ideas and solutions, or evaluating the validity of an argument.

It is essential to recognize that each level of DOK builds upon the previous level. At the first level, learners must recall basic knowledge, and at the second level, they must demonstrate understanding of the concept. In the third level, they must apply their knowledge in different contexts before finally engaging in critical thinking and synthesis at the highest level.

To further clarify the levels, consider a complex concept, such as climate change. At the recall level, learners might be asked to define climate change or name the greenhouse gases. At the understanding level, they might be asked to explain the causes of climate change or interpret data.

At the application level, learners might be asked to apply their knowledge by creating a proactive plan to reduce carbon emissions. Finally, at the highest level, learners might synthesize information from multiple sources to develop a solution to mitigate the negative effects of climate change.

Webb's DOK is a powerful tool for educators, creating a common language for discussing levels of cognitive complexity, designing instructional activities , and evaluating student progress. By considering the four levels of rigor, educators can craft learning experiences that meet students where they are and move them towards greater depth of knowledge.

What exactly do we mean by 'Depth of Knowledge'?

Depth of knowledge (DOK) is a concept used to assess the level of cognitive complexity required for students to complete a specific task. It was first introduced in 1997 by Dr. Norman Webb and involves categorizing tasks based on their cognitive demand. This allows teachers to better understand what students are capable of and design appropriate learning experiences to develop deeper understanding.

While the DOK wheel is a commonly used tool, it is not the same as depth of knowledge itself. The wheel simply displays different cognitive resource demands which allow teachers to more easily identify the DOK level required for a given activity.

Webb's 1997 study provides a framework for categorizing DOK into four levels of rigor. Each level builds on the previous one, and requires learners to engage in greater levels of cognitive complexity.

It is important to note that the DOK levels are not fixed and may vary depending on age group, subject, and context. By using DOK, teachers can create tasks that challenge students and encourage deeper learning.

What is the Learning Theory behind Webb's DOK?

The Webb learning theory , also known as Webb's depth of knowledge (DOK) framework, was developed by Dr. Norman Webb in 1997. Dr. Webb is a respected education researcher and psychologist who has devoted his career to exploring the complexities of learning and cognition.

Dr. Webb's motivation for developing the DOK framework was to provide educators with a clear and useful tool for measuring and promoting deeper student learning. The framework is designed to help teachers and learners identify the level of rigor required to complete a particular task or assignment, from basic recall to complex and nuanced thinking.

The DOK framework is different from other learning taxonomies, such as Bloom's Taxonomy, in that it focuses less on the type of cognitive task and more on the level of rigor required to complete it. This means that the DOK framework is useful not just for designing and evaluating assessments, but also for guiding instructional practices that promote deeper learning.

At its core, the DOK framework consists of four levels of increasing rigor. Level 1 tasks require students to recall basic information. Level 2 tasks involve some degree of comprehension or application of concepts and skills. Level 3 tasks require students to apply their knowledge and understanding in new and varied contexts. Finally, level 4 tasks require students to engage in higher-order thinking, such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

One of the key benefits of the DOK framework is its ability to promote deeper student learning. By focusing on the level of rigor required to complete a task, it encourages teachers and learners to engage in more complex and nuanced thinking. This means that students are able to develop their capacity for critical thinking, problem-solving, and cognitive flexibility, all of which are essential skills for success in today's complex and rapidly changing world.

The Webb learning theory, or the DOK framework, provides educators with a valuable tool for measuring and promoting deeper student learning. Its emphasis on the level of rigor required for a task or assignment, rather than the type of cognitive task, makes it a useful tool for designing effective assessments and promoting instructional practices that encourage complex and nuanced thinking.

Comparing Bloom's Taxonomy and Webb's Depth of Knowledge

Bloom's Taxonomy and Webb's Depth of Knowledge (DOK) are two well-known learning frameworks used by educators to promote deeper student learning. While they share some similarities, there are also some important conceptual differences that set them apart.

One of the key differences between Bloom's Taxonomy and Webb's DOK is their conceptual approach. Bloom's Taxonomy focuses on different types of cognitive tasks, from basic recall to more complex and abstract thinking, while Webb's DOK focuses on the level of rigor required to complete a particular task or assignment. This means that Bloom's Taxonomy is more focused on the type of thinking required, while Webb's DOK is more focused on the level of cognitive complexity required to complete a task.

Another significant difference between the two models is their alignment with academic standards. Bloom's Taxonomy is designed to align with content standards, which means that it focuses on specific subject matter and the level of thinking required to master it. In contrast, Webb's DOK is aligned with performance standards, which are broader and more encompassing and focus on what students should be able to do with the knowledge they have acquired.

Despite these differences, both models share some similarities. For example, both frameworks emphasize the importance of promoting higher-order thinking skills, such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation, and both can be implemented in the classroom to guide instructional practices that promote deeper student learning.

To implement Bloom's Taxonomy in the classroom, teachers might present students with a variety of tasks that require different levels of thinking and cognition. For example, a level 1 task might involve asking students to recall basic information from a text, while a level 3 task might involve asking them to analyze and evaluate the author's argument.

Similarly, to implement Webb's DOK, teachers might use a wheel chart or rubric to assess the level of rigor required to complete a particular task or assignment and provide students with feedback that encourages them to engage in deeper and more complex thinking.

The strengths of each method are different. Bloom's Taxonomy is useful for promoting critical thinking and problem-solving skills in specific subject areas. On the other hand, Webb's DOK is ideal for promoting cognitive complexity across a wide range of subject areas and assignments. By using both methods together, teachers can create a more robust and comprehensive approach to promoting deeper student learning.

In conclusion, while there are some conceptual differences between Bloom's Taxonomy and Webb's Depth of Knowledge, both frameworks are effective tools for promoting higher-order thinking skills and can be implemented in the classroom in a variety of ways. By understanding the strengths and differences of each method, educators can create a more effective and comprehensive approach to promoting student learning and cognitive complexity.

How does Webb's Depth of Knowledge increase Academic Rigor?

Introducing rigorous instruction in the classroom is one of the most effective ways of helping students develop critical thinking skills and acquire knowledge that they can apply in real-world contexts. Webb's Depth of Knowledge (DOK) is a framework that focuses on increasing rigor in classroom instruction by assessing the cognitive complexity of tasks and assignments. By understanding the four levels of rigor within the DOK framework, educators can design activities and assessments that help their students develop progressively more complex and sophisticated thinking skills.

Application of the DOK Levels

Educators can implement Webb's DOK in their classroom instruction by designing activities and assessments that align with each level. For example, teachers can design Level 1 tasks that focus on simple recall of information, such as asking students to identify key vocabulary words or concepts from a reading passage.

Level 2 tasks might involve applying knowledge and skills to new situations, such as asking students to use mathematical equations to solve real-world problems.

Level 3 tasks are more complex and may require students to analyze and synthesize information from multiple sources or use multiple strategies to complete a task. An example of a Level 3 task might be asking students to compare and contrast the arguments of two different authors on a controversial issue.

Finally, Level 4 tasks involve extended thinking that goes beyond the classroom, such as asking students to use their knowledge and skills to analyze and solve complex real-world problems. For example, a Level 4 task might involve working on a project that requires students to evaluate the environmental impact of a new development in their community.

The DOK framework helps educators increase rigor in classroom instruction by assessing the cognitive complexity of tasks and assignments. By designing activities and assessments that align with each level of rigor, teachers can create a learning environment that promotes critical thinking, problem-solving, and the acquisition of knowledge and skills that prepare students for successful futures.

Implementing Webb's DOK in Classroom Instruction

Webb's Depth of Knowledge (DOK) framework is a pedagogical tool used to design and align activities, assessments, and instructional delivery. The framework's four levels of complexity that are designed to challenge students' critical thinking, problem-solving, and metacognitive skills . Understanding and implementing Webb's DOK in classroom instruction is essential for designing lessons that challenge and foster students' thinking skills at the appropriate level of rigor.

To implement Webb's DOK in classroom instruction, teachers can design activities and assessments that align with each level of complexity. For example, teachers can design Level 1 tasks that focus on simple recall of information such as asking students to identify key vocabulary words or concepts from a reading passage. Activities that challenge Level 2 thinking might involve applying knowledge and skills to new situations such as asking students to use mathematical equations to solve real-world problems.

Level 3 tasks are more complex and often require students to analyze and synthesize information from multiple sources or use multiple strategies to complete a task. Teachers can design activities and assessments that challenge Level 3 thinking by asking students to compare and contrast arguments of two different authors on a controversial issue or to evaluate data from scientific experiments to draw conclusions.

Finally, Level 4 tasks involve extended thinking that goes beyond the classroom. Teachers can challenge students' critical thinking skills by providing authentic learning experiences such as working on a project that requires students to analyze and solve real-world problems. For example, students could evaluate the environmental impact of a new development in their community or design solutions for reducing traffic congestion in their city.

Teachers can use Webb's DOK to design lesson plans that challenge students at appropriate levels of rigor. By using the framework, teachers can align instructional delivery, activities, and assessments to maximize student engagement and learning outcomes. Teachers can also use DOK to differentiate instruction and accommodations for students with diverse learning needs. Activities can be modified to meet the unique learning needs of individual students based on their entry-level knowledge, learning styles, and learning challenges.

It is also important for students to use DOK to monitor their own learning progress . By understanding the levels of complexity, students can monitor their growth in critical thinking and problem-solving abilities. Students can use DOK to set growth targets, reflect on their learning progress, and identify areas of strength and weakness.

Teachers can incorporate active learning strategies such as authentic learning experiences, cooperative learning, and problem-based learning activities to challenge students at various levels of complexity. By implementing Webb's DOK framework, teachers can promote a rich learning environment that challenges and enhances students' thinking skills, resulting in deep learning and retention of knowledge .

Subject-Based Examples of DOK

The versatility of the DOK model makes it an excellent tool for educators to incorporate into lesson planning, regardless of the subject. By understanding the different levels of cognitive rigor required at each stage, teachers can create activities and assessments that challenge their students' critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Let's explore some subject-based examples of how teachers can effectively apply the DOK framework in their lesson planning:

In ELA, teachers can use the DOK framework to create reading and writing activities that align with all four of Webb's levels of complexity. For example, at Level 1, students could be asked to recall specific details from a text, such as identifying the main characters or setting. Level 2 tasks can challenge students to apply their knowledge of literary devices to analyze the text, such as identifying symbols or interpreting metaphors.

Level 3 tasks can be designed to challenge students to compare and contrast different perspectives in a text or drawing conclusions about character motivations. Finally, at Level 4, students could be asked to complete an extended writing project that requires them to use critical thinking and creativity to explore themes from the text in a real-world context.

In math class, teachers can use DOK to challenge students to apply their understanding of mathematical concepts to real-world problems. At Level 1, students can be asked to recall math facts and basic formulas. As they progress to more complex tasks, students can be asked to apply those facts and formulas to more complex problems, such as calculating the area and volume of three-dimensional shapes.

At Level 3, students could be challenged to use statistical data to analyze trends and make predictions, while Level 4 tasks could require students to apply mathematical principles to real-world scenarios, such as designing a bridge that can withstand certain environmental conditions.

In science classes, teachers can use DOK to challenge students to apply their knowledge to real-world phenomena. At Level 1, students could be asked to recall facts about the laws of physics or ecological systems.

As they progress to higher levels, students can be challenged to analyze and synthesize information from multiple sources to draw connections between various scientific principles. For example, students at Level 3 may be challenged to explain the impact of environmental factors on a specific species or predict the outcome of an experiment based on scientific principles.

Finally, at Level 4, students could be asked to design and execute scientific experiments that address real-world issues, such as developing alternative energy sources or evaluating the impact of climate change on ecosystems.

Assessment Creation:

It is crucial to make sure that students are exposed to tasks at all four levels of DOK to foster comprehensive learning and assess the varying levels of cognitive rigor. By incorporating the DOK framework into assessment creation, teachers can create assessments that accurately measure their students' learning progress.

For example, a math exam could include Level 1 questions on basic concepts and formulas, Level 2 questions that focus on applying those formulas to solve problems, Level 3 questions related to data analysis and synthesis, and finally, Level 4 questions on real-world problem solving and application. This approach ensures that the assessment accurately measures students' cognitive skills at all levels, and teachers can use the results to adjust their instruction accordingly.

In conclusion, teachers can use the DOK framework to design effective lesson plans that challenge students' cognitive abilities across various subjects. The model's versatility makes it a valuable tool for educators who wish to engage their students in meaningful learning experiences and ensure they develop the necessary skills to succeed in real-world contexts.

By incorporating DOK into assessment creation, teachers can also measure students' learning progress comprehensively and adjust their instruction accordingly.

Utilising Webb's DOK in Special Education

Webb's Depth of Knowledge (DOK) is a framework that helps educators structure lessons and assessments based on the complexity of thinking required. When teaching special education students, it is important to utilize DOK to ensure that each student's unique pace and learning needs are taken into account.

One of the key considerations when applying DOK in special education is the individualized learning needs of each student. For example, teachers should consider the student's preferred learning style, communication abilities, and areas of strengths when creating lesson plans. By doing so, teachers can create a tailored learning experience that aligns with each student's strengths and limitations, while also ensuring that each student is challenged at an appropriate level of cognitive complexity.

To ensure that special education students stay engaged throughout the learning process, teachers should aim to create authentic learning experiences that link the concepts being taught to real-world contexts. This can help to give students a sense of purpose, and make the learning process more tangible and relevant. Using adaptive learning platforms with active learning strategies can also help to keep students engaged by providing a level of interactivity that is not possible with traditional teaching methods.

In addition, it is important for teachers to work collaboratively with professional learning coaches to develop DOK materials and lessons that are tailored to the specific needs of the special education student. This can help to ensure that each student is learning at an appropriate level of cognitive complexity, and that each student is being challenged in a way that is appropriate for their individual needs.

Overall, implementing DOK in special education requires a focus on individualized learning, authentic learning experiences, and collaboration with professional learning coaches. By taking these factors into account, teachers can create a rich learning environment that helps special education students achieve their full potential. The use of Solo Taxonomy can also enhance the implementation of DOK in special education.

Key Insights and Further Reading on Webb's DoK

Here are five key papers or research articles discussing Webb's Depth of Knowledge (DOK) and its implications in education:

1. Critical Thinking, Instruction, and Professional Development for Schools in the Digital Age by H. Coleman, Jeremy Dickerson, Dennis Dotterer (2017)

Summary: This paper emphasizes the use of Webb's DOK as a theoretical guide to create flexible, student-centered instructional models in schools, promoting higher-level critical thinking skills and professional development.

2. Depth of Teachers' Knowledge: Frameworks for Teachers' Knowledge of Mathematics by V. Holmes (2012)

Summary: The study utilizes Webb's DOK framework as a tool for classifying teachers' knowledge in mathematics, providing a vocabulary for discussing and assessing their understanding at different school levels.

3. Taxonomies in Education: Overview, Comparison, and Future Directions by J. Irvine (2021)

Summary: Irvine analyzes Webb's DOK as a popular taxonomy in education to compare knowledge, cognition, metacognition, higher-order thinking skills, and affect in learning environments.

4. Lecture Breakup- A Strategy for Designing Pedagogically Effective Lectures for Online Education Systems by Siddharth Srivastava, Shalini Lamba, T. Prabhakar (2020)

Summary: This article discusses the application of Webb's DOK in designing quality lectures for online education systems, highlighting its relevance in traditional classroom-based teaching.

5. Quantifying Depth and Complexity of Thinking and Knowledge by Tamal Biswas, Kenneth W. Regan (2015)

Summary: The paper explores Webb's Depth of Knowledge as a qualitative approach to cognitive rigor, assessing depth and complexity in Education Studies.

These papers provide insights into the application and significance of Webb's DOK in various educational contexts, from teacher training programs to online learning environments , emphasizing its role in enhancing critical thinking and understanding at different levels of cognitive complexity.

Frequently Asked Questions about Depth of Knowledge (DOK)

As educators continue to explore new ways of improving student learning, there has been an increased popularity in using Webb's Depth of Knowledge (DOK) framework. However, this framework can be quite complex and often leads to questions among educators about its purpose, implementation, and how it could benefit student learning.

To address these questions, we have created a Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) section on DOK that aims to provide educators with a comprehensive guide to understanding this framework.

The purpose of this section is to offer essential insights on DOK, provide answers to most frequently asked questions, explain how to implement DOK in a meaningful way, and highlight the benefits for student learning.

Whether you are a teacher or a school administrator, you will likely find this section to be a valuable resource in understanding the different levels of cognitive complexity, the benefits of adopting this framework, how to determine the appropriate DOK level for your students, and how to use DOK to develop assessments and lesson plans that align with state standards.

Q1: What is Webb's Depth of Knowledge (DOK)?

Webb's Depth of Knowledge is a framework that categorizes tasks according to the complexity of thinking required to successfully complete them. It is used to analyze the cognitive expectation demanded by standards, curricular activities, and assessment tasks.

Q2: How many levels are there in Webb's DOK?

Webb's DOK is made up of four levels. Level 1 involves recall and reproduction, Level 2 involves skills and concepts, Level 3 involves strategic thinking, and Level 4 involves extended thinking.

Q3: How does Webb's DOK differ from Bloom's Taxonomy?

While both Bloom's Taxonomy and Webb's DOK are frameworks for classifying learning objectives, they are different in their focus. Bloom's taxonomy is a hierarchy of the different levels of cognitive processing , while Webb's DOK focuses on the complexity of mental processing that must occur to complete a task.

Q4: How can I use Webb's DOK in my teaching?

Webb's DOK can be used to ensure your instruction targets various levels of cognitive demand. By understanding the DOK levels of your teaching activities, you can better align these activities with assessments and learning objectives.

Q5: Can Webb's DOK be used to create assessments?

Yes, Webb's DOK is often used to guide the development of assessments, ensuring that they measure the intended cognitive processes . For example, you might design some questions to target lower DOK levels (e.g., recall of information) and others to target higher DOK levels (e.g., strategic and extended thinking).

Q6: Does Webb's DOK align with Common Core State Standards?

Yes, Webb's DOK has been used in the development of the Common Core State Standards to indicate the level of cognitive demand associated with each standard. The intention is to ensure a good balance of cognitive demands across each grade level.

Enhance outcomes across your school

Download an overview of our classroom toolkit.

We'll send it over now.

Please fill in the details so we can send over the resources.

What type of school are you?

We'll get you the right resource

Is your school involved in any staff development projects?

Are your colleagues running any research projects or courses?

Do you have any immediate school priorities?

Please check the ones that apply.

Download your resource

Thanks for taking the time to complete this form, submit the form to get the tool.

Classroom Practice

Writing Resources

- Getting Started

- Free Writing Support Resources for Students

- DNP Editors - PC744 SQUIRE Paper

- APA, AMA, Citation, References, DOI, Plagiarism/Copyright

- Microsoft Word and Google Docs Tutorials

- Self-Editing

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking and writing.

- Discourse Community

- Information Literacy

- Gathering Information / Literature Review: Synthesis and Paraphrase

- Writing Mechanics: Punctuation, Grammar, Syntax

- Style/Organization: APA, AMA, SQUIRE

- Fee-Based Editing-Proofreading

- Presentations

- RefWorks Reference Management Software

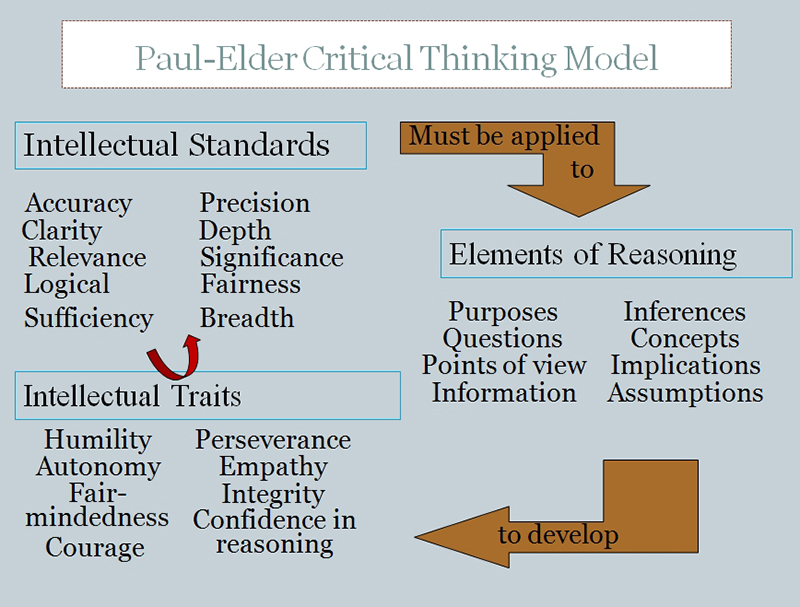

- Resumes and Cover Letters

- To Analyze Thinking We Must Identify and Question its Elemental Structures Elements of Thought presented as a "wheel" model. [Scroll to the Wheel at the bottom of the page.] This is a superb resource for developing ideas and organizing an argument, paper, or presentation. See More below. more... less... By hovering over any element of thought in the wheel, a flyout will appear to help you refine this aspect of your thinking. Also demonstrates how elements of your thinking is integrated with other parts of thought.

- Critical Thinking - Summary Description Excellent five-minute video that describes some of the main principles of critical thinking.

- Defining Critical Thinking The Foundation for Critical Thinking provides structure and definitions for learning to think about your own thinking, a process known as metacognition. This site is recommended in our FNU Introduction to Scholarly Writing Course. It describes concepts involved in critical thinking.

- Critical Thinking "Wheel"_To Analyze Thinking We Must Identify and Question its Elemental Structures Elements of Thought presented as a "wheel" model. Superb resource for developing ideas and organizing an argument, paper, or presentation. See More below. more... less... By hovering over any element of thought in the wheel, a flyout will appear to help you refine this aspect of your thinking. Also demonstrates how elements of your thinking is integrated with other parts of thought.

- Demonstrating critical thinking in writing assignments EXCELLENT VIDEO from Walden University (one hour): Demonstrating critical thinking through writing is one of the tasks of a scholar. This webinar explores some strategies on how to incorporate critical thinking in your writing, highlighting how to use sources to support your own ideas and focusing on creating a thesis statement. NOTE: To view this webinar you must download the free Adobe Connect app. Additional resources, slides, and handouts are available. This instructional content was created by the Walden University Writing Center and is reused under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Critical Reading Critical reading is a vital part of the writing process. In fact, reading and writing processes are alike. In both, you make meaning by actively engaging a text. As a reader, you are not a passive participant, but an active constructor of meaning. Exhibiting an inquisitive, "critical" attitude towards what you read will make anything you read richer and more useful to you in your classes and your life. This guide is designed to help you to understand and engage this active reading process more effectively so that you can become a better critical reader. There is a link on this site in the right navigation bar to download a printable version, with this URL: https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/pdfs/guide31.pdf

- Make a claim (thesis/main idea) for an argument and support with evidence This describes how to express a point of view on a subject (a claim or thesis main idea) and support your argument with evidence. This is an essential skill for academic writers.

- UNC Chapel Hill Writing Center Handouts A comprehensive list of handouts and videos on an assortment of topics related to writing and critical thinking. As an example, select "Argument" in the Writing the Paper column. You will see how to construct a thesis statement to present a main idea or claim (your thesis) and back it up with evidence for statements that support your claim.

- << Previous: Self-Editing

- Next: Discourse Community >>

- Last Updated: Mar 7, 2024 12:58 PM

- URL: https://library.frontier.edu/writingresources

- Schools & departments

Critical thinking

Advice and resources to help you develop your critical voice.

Developing critical thinking skills is essential to your success at University and beyond. We all need to be critical thinkers to help us navigate our way through an information-rich world.

Whatever your discipline, you will engage with a wide variety of sources of information and evidence. You will develop the skills to make judgements about this evidence to form your own views and to present your views clearly.

One of the most common types of feedback received by students is that their work is ‘too descriptive’. This usually means that they have just stated what others have said and have not reflected critically on the material. They have not evaluated the evidence and constructed an argument.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking is the art of making clear, reasoned judgements based on interpreting, understanding, applying and synthesising evidence gathered from observation, reading and experimentation. Burns, T., & Sinfield, S. (2016) Essential Study Skills: The Complete Guide to Success at University (4th ed.) London: SAGE, p94.

Being critical does not just mean finding fault. It means assessing evidence from a variety of sources and making reasoned conclusions. As a result of your analysis you may decide that a particular piece of evidence is not robust, or that you disagree with the conclusion, but you should be able to state why you have come to this view and incorporate this into a bigger picture of the literature.

Being critical goes beyond describing what you have heard in lectures or what you have read. It involves synthesising, analysing and evaluating what you have learned to develop your own argument or position.

Critical thinking is important in all subjects and disciplines – in science and engineering, as well as the arts and humanities. The types of evidence used to develop arguments may be very different but the processes and techniques are similar. Critical thinking is required for both undergraduate and postgraduate levels of study.

What, where, when, who, why, how?

Purposeful reading can help with critical thinking because it encourages you to read actively rather than passively. When you read, ask yourself questions about what you are reading and make notes to record your views. Ask questions like:

- What is the main point of this paper/ article/ paragraph/ report/ blog?

- Who wrote it?

- Why was it written?

- When was it written?

- Has the context changed since it was written?

- Is the evidence presented robust?

- How did the authors come to their conclusions?

- Do you agree with the conclusions?

- What does this add to our knowledge?

- Why is it useful?

Our web page covering Reading at university includes a handout to help you develop your own critical reading form and a suggested reading notes record sheet. These resources will help you record your thoughts after you read, which will help you to construct your argument.

Reading at university

Developing an argument

Being a university student is about learning how to think, not what to think. Critical thinking shapes your own values and attitudes through a process of deliberating, debating and persuasion. Through developing your critical thinking you can move on from simply disagreeing to constructively assessing alternatives by building on doubts.

There are several key stages involved in developing your ideas and constructing an argument. You might like to use a form to help you think about the features of critical thinking and to break down the stages of developing your argument.

Features of critical thinking (pdf)

Features of critical thinking (Word rtf)

Our webpage on Academic writing includes a useful handout ‘Building an argument as you go’.

Academic writing

You should also consider the language you will use to introduce a range of viewpoints and to evaluate the various sources of evidence. This will help your reader to follow your argument. To get you started, the University of Manchester's Academic Phrasebank has a useful section on Being Critical.

Academic Phrasebank

Developing your critical thinking

Set yourself some tasks to help develop your critical thinking skills. Discuss material presented in lectures or from resource lists with your peers. Set up a critical reading group or use an online discussion forum. Think about a point you would like to make during discussions in tutorials and be prepared to back up your argument with evidence.

For more suggestions:

Developing your critical thinking - ideas (pdf)

Developing your critical thinking - ideas (Word rtf)

Published guides

For further advice and more detailed resources please see the Critical Thinking section of our list of published Study skills guides.

Study skills guides

15 Things We Have Learned About Critical Thinking

Here are the key issues to consider in critical thinking..

Posted July 27, 2018

- What Is Cognition?

- Find a therapist near me

Not long after the publication of my book, Critical Thinking: Conceptual Perspectives and Practical Guidelines , by Cambridge University Press, Psychology Today contacted me and asked me to write a blog on the subject. I never thought I would write a blog, but when presented with the opportunity to keep sharing my thoughts on critical thinking on a regular basis, I thought, why not ? Maybe my writing might help educators, maybe they might help students and maybe they might help people in their day-to-day decision-making . If it can help, then it’s worthwhile.

To recap, critical thinking (CT) is a metacognitive process, consisting of a number of sub-skills and dispositions, that, when applied through purposeful, self-regulatory, reflective judgment, increase the chances of producing a logical solution to a problem or a valid conclusion to an argument (Dwyer, 2017; Dwyer, Hogan & Stewart, 2014).

CT, if anything, has become more necessary , in this age of information bombardment and the new knowledge economy (Dwyer, Hogan & Stewart, 2014). It allows students to gain a better understanding of complex information (Dwyer, Hogan, & Stewart, 2012; 2014; Gambrill, 2006; Halpern, 2014); it allows them to achieve higher grades and become more employable, informed and active citizens (Barton & McCully, 2007; Holmes & Clizbe, 1997; National Academy of Sciences, 2005); it facilitates good decision-making and problem-solving in social and interpersonal contexts (Ku, 2009); and it decreases the effects of cognitive biases and heuristic -based thinking (Facione & Facione, 2001; McGuinness, 2013).

It’s now been just over a year since I started writing ‘Thoughts on Thinking’. As I consider my thinking and look over my writing during this period, I thought it would be worthwhile to collate and summarise some of the broader learning that has appeared in my writings. So, here’s what we’ve learned:

- We all know CT is important, but it may be the case that many educators, as well as students, don’t really know what researchers mean by "critical thinking" and/or simply haven’t researched it themselves.

- Just as many don’t really know what is meant by "critical thinking", there is also the problem of ensuring consistency across how it is defined/conceptualised, trained and measured , which is no easy task.

- Without adequate training in CT, it may be the case that mature students’ perceptions of how they approach CT do not match their actual ability - despite potentially enhanced autonomy, student responsibility and locus of control , it may be that an over- optimistic outlook on the benefits of experience (and its associated heuristic-based, intuitive judgment) takes centre-stage above and beyond actual ability.

- Social media is many things: entertainment, education , networking and much more. It is also, unfortunately, a vehicle for promoting faulty thinking. Being able to recognise persuasion techniques, illogical argumentation and fallacious reasoning , will allow you to better assess arguments presented to you, and help you to present better arguments.

- Values are unique to each and every individual. Though individuals can certainly share values, there is no guarantee that all of an individual’s values overlap with another’s. On the other hand, using the 'virtue' moniker implies that the individual is right based on some kind of ‘moral correctness’. Though there is nothing wrong with an individual presenting ideas and perspectives that they value, it is ill-conceived and dangerous to treat them as global virtues that everyone else should value too.

- CT is domain-g eneral, but explicit CT training is necessary if educators want to see CT improve and flourish across domains.

- A person with a strong willingness to conduct CT has the consistent internal willingness and motivation to engage problems and make decisions by using reflective judgment . Reflective judgment, the recognition of limited knowledge and how this uncertainty can affect decision-making processes, is an important aspect of critical thinking regarding ‘taking a step back’ and thinking about an argument or problem a little bit longer and considering the basis for the reasons and consequences of responding in a particular way.

- There is a need for general, secondary-school training in bias and statistics. We need to teach CT to the coming generations. When not critically thinking, people don’t listen, and fail to be open-minded and reflect upon the information presented to them; they project their opinions and beliefs regardless of whether or not they have evidence to support their claims.

- Be open-minded towards others. You don’t have to respect them (respect is earned, it’s not a right); but be courteous (sure, we may be in disagreement; but, hey, we’re still civilised people).

- A person said what they said, not how you interpret what they said. If you are unclear as to what has been said, ask for clarification. Asking for clarity is not a sign of weakness; it is a sign of successful problem-solving.

- ‘Proof’ is the dirtiest word in critical thinking. Research and science do not prove things, they can only disprove. Be wary when you hear the word ‘prove’ or any of its variants thrown around; but also, be mindful that people feel safer when they are assured and words like ‘proven’ reinforce this feeling of assuredness.

- Creative thinking isn’t really useful or practical in critical thinking, depending on how you conceptualize it. Critical thinking and creative thinking are very different entities if you treat the latter as something similar to lateral thinking or ‘thinking outside the box’. However, if we conceptualize creative thinking as synthesizing information for the purpose of inferring a logical and feasible conclusion or solution, then it becomes complementary to critical thinking. But then, we are not resorting to creativity alone - all other avenues involving critical thinking must be considered. That is, we can think creatively by synthesizing information we have previously thought about critically (i.e. through analysis and evaluation ) for the purpose of inferring a logical and feasible conclusion or solution. Thus, given this caveat, we can infuse our critical thinking with creative thinking, but we must do so with caution.

- Changing people’s minds is not easy ; and it’s even more difficult when the person you’re working with believes they have critically thought about it. It may simply boil down to the person you’re trying to educate and their disposition towards critical thinking, but the person’s emotional investment in their stance also plays a significant role.

- There is no such thing as good or bad CT – you either thought critically or you didn’t. Those who try it in good faith are likely to want to do it ‘properly’; and so, much of whether or not an individual is thinking critically comes down to intellectual humility and intellectual integrity .

- Finally, there are some general tips that people find useful in applying their critical thinking:

- Save your critical thinking for things that matter - things you care about.

- Do it earlier in your day to avoid faulty thinking resulting from decision fatigue.

- Take a step back and think about a problem a little bit longer, considering the basis for the reasons and consequences of responding in a particular way.

- Play Devil’s Advocate in order to overcome bias and 'auto-pilot processing' through truly considering alternatives.

- Leave emotion at the door and remove your beliefs, attitudes, opinions and personal experiences from the equation - all of which are emotionally charged.

Barton, K., & McCully, A. (2007). Teaching controversial issues where controversial issues really matter. Teaching History, 127, 13–19.

Dwyer, C.P. (2017). Critical thinking: Conceptual perspectives and practical guidelines. UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J., & Stewart, I. (2012). An evaluation of argument mapping as a method of enhancing critical thinking performance in e-learningenvironments. Metacognition and Learning, 7, 219–244.

Dwyer, C.P., Hogan, M.J. & Stewart, I. (2014). An integrated critical thinking framework for the 21st century. Thinking Skills & Creativity, 12, 43-52.

Eigenauer, J.D. (2017). Don’t reinvent the critical thinking wheel: What scholarly literature tells us about critical thinking instruction. Innovation Abstracts, 39, 2.

Facione, P. A., & Facione, N. C. (2001). Analyzing explanations for seemingly irrational choices: Linking argument analysis and cognitive science. International Journal of Applied Philosophy, 15(2), 267–286.

Gambrill, E. (2006). Evidence-based practice and policy: Choices ahead. Research on Social Work Practice, 16(3), 338–357.

Halpern, D.F. (2014). Though and knowledge. UK: Psychology Press.

Holmes, J., & Clizbe, E. (1997). Facing the 21st century. Business Education Forum, 52(1), 33–35.

Ku, K. Y. L. (2009). Assessing students’ critical thinking performance: Urging for measurements using multi-response format. Thinking Skills and Creativity,4(1), 70–76.

McGuinness, C. (2013). Teaching thinking: Learning how to think. Presented at the Psychological Society of Ireland and British Psychological Association’s Public Lecture Series. Galway, Ireland, 6th March.

National Academy of Sciences. (2005). National Academy of Engineering Institute of Medicine Rising above the gathering storm: Energising and employingAmerica for a brighter economic future. Committee on prospering in the global economy for the 21st century. Washington, DC.

Christopher Dwyer, Ph.D., is a lecturer at the Technological University of the Shannon in Athlone, Ireland.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain