- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Clinical Case Study: Cystic fibrosis

Published by Jason Hardy Modified over 6 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Clinical Case Study: Cystic fibrosis"— Presentation transcript:

By: Ryan M. and Anthony L..

Hanadi Baeissa Therapeutic Nutrition. Therapeutic nutrition = Medical nutrition therapy The role of food and nutrition in the treatment of various diseases.

Nutrition Care Process (NCP)

© 2007 Thomson - Wadsworth Chapter 13 Nutrition Care and Assessment.

CF Related Diabetes ADEU November Cystic Fibrosis Genetic disorder Exocrine pancreas dysfunction Autosomal recessive inheritance Several identified.

Cystic Fibrosis Gina Brandl, RN BSN Nursing Instructor, Pediatrics.

Cystic fibrosis. Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder that affects most critically the lungs, and also the pancreas, liver,

Tiffany Rimmer. CF is the most common lethal autosomal recessive genetic disease in Caucasians. It affects over 30,000 individuals in the United States.

CYSTIC FIBROSIS FANOURAKI MARIA CHARALAMPIDOU ALEXANDRA

Cystic Fibrosis By Kristy Sandman. Physiology Genes found in nucleus of each cell Genes made up of nucleotides Genes can be rearranged or mutated Genes.

1 RETROSPECTIVE EVALUATION OF THE PATIENTS WITH CYSTIC FIBROSIS DR.LALE PULAT SEREN ZEYNEP KAMİL MATERNITY AND CHILDREN’S TRAINING AND RESEARCH HOSPITAL.

Mosby items and derived items © 2005 by Mosby, Inc. Chapter 43 Nutrition.

Cystic Fibrosis Stacey Simon. Statistics Most common lethal, hereditary disorder among Caucasians 1 in 1,000 live births Prevalence: 30,000 children.

By: Ruth Maureen Riggie

By Taliyah and Selina. Cystic Fibrosis CF Mucoviscidosis.

Symptoms In newborns: – Delayed growth – Failure to gain weight normally during childhood – No bowel movements in first 24 to 48 hours of life – Salty-tasting.

Patient: Lily Johnson Case study by Alexa Angelo

Cystic Fibrosis Islamic university Nursing College.

Cystic Fibrosis Kayla Barber. What is it? Cystic Fibrosis is a hereditary disease that a person gets when BOTH parents are carriers. It causes abnormally.

CAUSES OF CYSTIC FIBROSIS CF is caused by a mutation in the gene for the protein cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). This protein.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Global health

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 14, Issue 11

- Cystic fibrosis: a diagnosis in an adolescent

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9674-0879 Monica Bennett 1 ,

- Andreia Filipa Nogueira 1 ,

- Maria Manuel Flores 2 and

- Teresa Reis Silva 1

- 1 Pediatric , Centro Hospitalar e Universitario de Coimbra EPE , Coimbra , Portugal

- 2 Pediatric , Centro Hospitalar do Baixo Vouga EPE , Aveiro , Aveiro , Portugal

- Correspondence to Dr Monica Bennett; acinomaicila{at}gmail.com

Most patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) develop multisystemic clinical manifestations, the minority having mild or atypical symptoms. We describe an adolescent with chronic cough and purulent rhinorrhoea since the first year of life, with diagnoses of asthma, allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis. Under therapy with long-acting bronchodilators, antihistamines, inhaled corticosteroids, antileukotrienes and several courses of empirical oral antibiotic therapy, there was no clinical improvement. There was no reference to gastrointestinal symptoms. Due to clinical worsening, extended investigations were initiated, which revealed Pseudomonas aeruginosa in sputum culture, sweat test with a positive result and heterozygosity for F508del and R334W mutations in genetic study which allowed to confirm the diagnosis of CF. In this case, heterozygosity with a class IV mutation can explain the atypical clinical presentation. It is very important to consider this diagnosis when chronic symptoms persist, despite optimised therapy for other respiratory pathologies and in case of isolation of atypical bacterial agents.

- cystic fibrosis

- pneumonia (respiratory medicine)

https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2021-245971

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

A high degree of diagnostic suspicion is of fundamental importance when chronic symptoms persist, despite optimised therapy for previous diagnoses and in case of isolation of atypical bacterial agents in microbiological studies.

This case describes an adolescent with a chronic cough since the first year of life, adequate weight gain and normal pubertal development, without improvement with optimised therapy for other respiratory pathologies. There was no reference to gastrointestinal symptoms. There was clinical worsening at 13 years of age and isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in sputum culture. After extensive investigation, including sweat test and genetic study, it was possible to confirm the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis (CF).

Case presentation

A 13-year-old female teenager presented with chronic cough and purulent rhinorrhoea with periods of intermittent clinical worsening with associated fever since the first year of life. This was accompanied by various medical specialties, with diagnoses of asthma, allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis. She was under therapy with long-acting bronchodilators, antihistamines, inhaled corticosteroids, and antileukotrienes and submitted to several courses of empirical oral antibiotic therapy, without sustained and effective clinical improvement. She presented an adequate height–weight evolution, with a body mass index (BMI) at 50th−85th percentile and normal pubertal development, no reference to gastrointestinal symptoms or previous hospitalisations. Her family background was irrelevant. Due to clinical worsening, with emetising cough associated with intermittent fever and night sweats, a pulmonary CT scan was performed, which revealed parenchymal densification, air bronchogram, thickened bronchi, mucoid impaction and mediastinal adenopathies. Observed in the emergency department, the objective examination highlighted bibasal crackles on pulmonary auscultation, without other alterations. She was treated with clarithromycin, later associated with co-amoxiclav. An extended investigation was initiated, which revealed erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 52 mm/hour, C reactive protein test of 4.10 mg/dL, negative BK and interferon gamma release assay test, and isolation of P. aeruginosa in sputum culture. The antibiotic therapy was changed to ciprofloxacin and sweat tests were performed with positive results on two occasions (102 and 110 mmol/L). Later, a genetic study revealed heterozygosity for the F508del and R334W mutations, which confirmed the diagnosis of CF. Faecal elastase was performed, and the result was normal (>500 µg/g).

After antimicrobial therapy with ciprofloxacin, she maintained P. aeruginosa, and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) was now discovered in the sputum. For this reason, she was hospitalised for intravenous eradication. After 2 weeks of antibiotic therapy with meropenem, gentamicin and teicoplanin, P. aeruginosa was eradicated but not MSSA. Linezulide was prescribed for 2 weeks, with a good response, and the microbiological study was negative.

Outcome and follow-up

During the follow-up period (2 years), she continued having frequent respiratory infections, with isolation of P. aeruginosa and MSSA in respiratory secretions intermittently, requiring the need for several courses of antibiotic therapy. The antibiogram of P. aeruginosa has remained sensible. Currently, she continues follow-up in a specialised fibrosis cystic centre, under inhaled therapy with colistin/tobramycin, hypertonic saline, salbutamol, dornase alfa, budesonide/formoterol, chest physiotherapy and oral azithromycin prophylaxis. Her pulmonary function is normal with a currently forced expiratory volume in 1 s of 87% and she shows adequate height−weight evolution, with BMI maintained at P50–85. The sweat chloride test was not repeated after confirmed diagnosis.

CF is one of the most commonly diagnosed genetic disorders 1 and the most common life-shortening autosomal recessive disease among Caucasian populations, with a frequency of 1 in 2000–3000 live births. 2 CF is caused by mutations in a single large gene on chromosome 7 that encodes the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator ( CFTR ) protein.

There are more than 2000 mutations/variations of the CFTR gene reported and listed in the CFTR mutation database. A small subset are CF disease-causing mutations, of which the majority are associated with pancreatic insufficiency and a smaller subset are associated with pancreatic sufficiency. Most of the known mutations/variations related to CF are described in the CFTR2 database (Clinical and Functional Translation of CFTR). This website provides information about what is currently known about specific genetic variants or variant combination and is a useful resource to correlate clinical measures to the large number of variants identified to date. 3 4

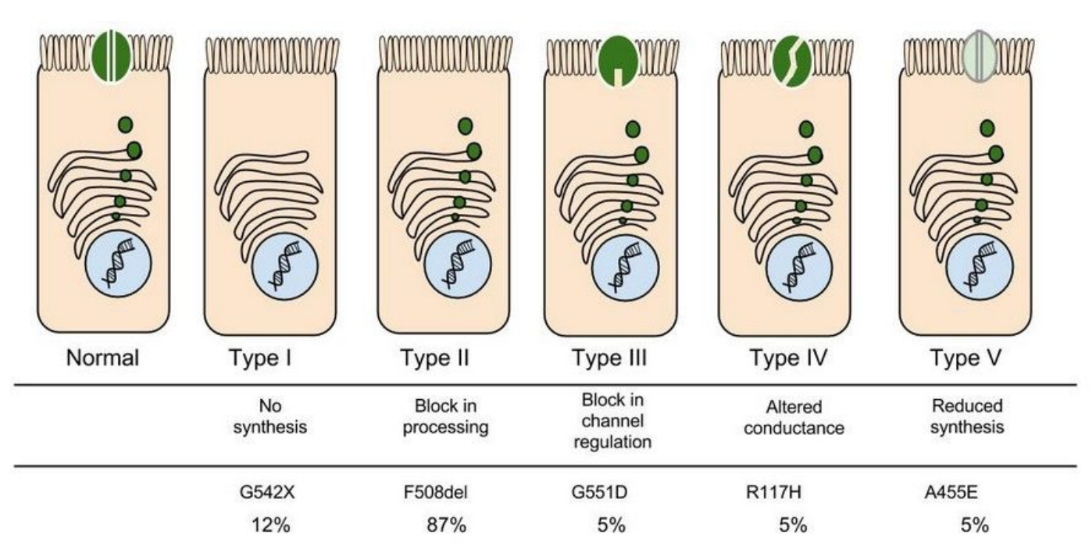

Clinical disease requires disease-causing mutations in both copies of the CFTR gene. Mutations of the CFTR gene have been divided into five different classes. The most common mutation is F508del which is included in category class II mutations—defective protein processing. Approximately 50% of patients with CF are homozygous for this mutation, and 90% will carry at least one copy of this gene. In general, mutations in classes I−III cause more severe disease than those in classes IV and V. Class IV and V mutations are associated with moderate phenotypes and pancreatic sufficiency. 5 The R334W is a rare mutation included in class IV—defective conduction and associated with pancreatic sufficiency. 5 6 Those with less severe mutations present with pancreatic sufficiency and single organ manifestations of CF. Some of these patients would fulfil the diagnostic criteria for CF and some would be classified as having a CFTR-related disorder if the diagnosis of CF cannot be fulfilled. 7

The phenotypic expression of disease varies widely, based on CFTR-related (genotype-related) and non-CFTR-related factors (environmental and other genetic modifiers). Genotype–phenotype correlations are weak for pulmonary disease in CF and somewhat stronger for the pancreatic insufficiency phenotype. 5

Many studies in different individuals heterozygous for CFTR gene mutation have been performed to find out the association of CFTR gene mutation with asthma. The results are inconclusive, as some of the studies have shown positive association, whereas other could find either protective or no association. 8 Also, at this time, there is no evidence for a specific association between CFTR gene mutation and other allergic manifestations.

Clinical manifestations are multisystemic and heterogeneous. 9 The first symptoms of the disease usually appear in the first years of life, and most patients develop a multisystem disease, with predominantly respiratory and digestive symptoms. 2 5 10 The usual presenting symptoms and signs include persistent pulmonary infection, pancreatic insufficiency and elevated sweat chloride levels. However, many patients demonstrate mild or atypical symptoms, and clinicians should remain alert to the possibility of CF even when only a few of the usual features are present. 2 Progressive pulmonary involvement is the main cause of morbidity and mortality. Clinically significant pancreatic insufficiency eventually develops in approximately 85% of individuals with CF. The remaining 10%–15% of patients with CF remain pancreatic sufficient throughout childhood and early adulthood, but these individuals are at risk of pancreatitis. Pancreatic exocrine function may be evaluated indirectly by measurement of faecal elastase, which is clinically practical but has limited accuracy. Low levels of faecal elastase suggest pancreatic insufficiency and support a diagnosis of CF. 2 5 11–13

The diagnosis of CF is based on compatible clinical findings with biochemical or genetic confirmation. The sweat chloride test is the mainstay of laboratory confirmation, although tests for specific mutations, nasal potential difference (NPD), immunoreactive trypsinogen, stool faecal fat or pancreatic enzyme secretion may also be useful in some cases.

Both of the following criteria must be met to diagnose CF: (1) clinical symptoms consistent with CF in at least one organ system, or positive newborn screen or having a sibling with CF; and (2) evidence of cystic CFTR dysfunction (any of the following): elevated sweat chloride ≥60 mmol/L; presence of two disease-causing mutations in the CFTR gene, one from each parental allele; abnormal NPD.

Sweat chloride test ≥60 mmol/L is considered abnormal. If confirmed on a second occasion, this is sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of CF in patients with clinical symptoms of CF. Positive results of sweat testing should be further evaluated by CFTR sequencing. Determining the CFTR genotype is important because the results may affect treatment choices as well as confirm the diagnosis. For patients with inconclusive results of sweat chloride and DNA testing, measurement of NPD can be used to further evaluate for CFTR dysfunction. 5 14

Newborn screening programmes for CF are now performed routinely in several countries, which contributed to a dramatic increase in the number of CF cases identified before presenting with symptoms. The rationale for this screening is that early detection of CF may lead to earlier intervention and improved outcomes because the affected individuals are diagnosed, referred and treated earlier in life compared with individuals who are diagnosed after presenting with symptomatic CF. In Portugal and some other European countries, this programme was implemented less than 10 years ago, contributing to a late diagnosis in older children.

There are different neonatal screening programmes that include biochemical screening and/or DNA assays with panels to test for the most common CFTR mutations in the local population. Most programmes test for between 23 and 40 mutations, and some programmes even perform adjunctive full gene sequencing. Screening for a greater number of mutations increases the likelihood of identifying infants with CF and also increases the identification of rare or unique sequence mutations, making interpretation of the result more complicated. As only a limited number of mutations are evaluated on the genetic screens, it is possible to miss the diagnosis. Thus, it is important to follow such children closely, with particular attention to weight gain and recurrent respiratory infections. Clinicians should consider CF in individuals with suggestive symptoms, even when results of the newborn screen are negative or equivocal. 5 14

In the case described here, heterozygosity with a class IV mutation, usually associated with an intermediate phenotype and pancreatic sufficiency, may explain the atypical clinical presentation and consequent diagnosis only in adolescents. We also hypothesise that this child’s allergic manifestations may have delayed the diagnosis.

As the spectrum of clinical presentation is very variable, it is very important for clinicians from multiple specialties to be vigilant and suspect this diagnosis in conditions such as recurrent pulmonary infection, male infertility, pancreatitis, nasal polyposis and malabsorption even in patients with negative newborn screening. 2 10 13

Learning points

There is a wide spectrum of manifestations of cystic fibrosis (CF). These variations and wide spectrum are based on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-related (genotype-related) and non-CFTR-related factors (environmental and other genetic modifiers).

Most patients with CF develop multisystemic and heterogeneous clinical manifestations, with predominantly respiratory and digestive symptoms.

A minority have mild or atypical symptoms.

Heterozygosity with a class IV mutation usually is associated with an intermediate phenotype and pancreatic sufficiency and can explain the atypical clinical presentation.

It is very important to consider this diagnosis when chronic symptoms persist, despite optimised therapy for other respiratory pathologies and in case of isolation of atypical bacterial agents in microbiological studies.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Consent obtained from parent(s)/guardian(s)

- Dickinson KM ,

- ↵ Cystic fibrosis mutation database . Available: http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/Home.html

- ↵ Clinical and functional translation of CFTR . Available: https://cftr2.org/

- Ellis L , et al

- Awasthi S ,

- Gartner S ,

- Salcedo Posadas A ,

- García Hernández G

- Castellani C ,

- Linnane B ,

- Pranke I , et al

- Farrell PM ,

- Ren CL , et al

- Kharrazi M ,

- Bishop T , et al

Contributors MB cared for study patient, planned and wrote the article. AFN collected data. MMF provided and cared for study patient, served as scientific advisors and critically reviewed the study proposal. TRS cared for study patient, served as scientific advisors and critically reviewed the study proposal.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

Case Study: Cystic Fibrosis - CER

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 26446

This page is a draft and is under active development.

Part I: A Case of Cystic Fibrosis

Dr. Weyland examined a six month old infant that had been admitted to University Hospital earlier in the day. The baby's parents had brought young Zoey to the emergency room because she had been suffering from a chronic cough. In addition, they said that Zoey sometimes would "wheeze" a lot more than they thought was normal for a child with a cold. Upon arriving at the emergency room, the attending pediatrician noted that salt crystals were present on Zoey's skin and called Dr. Weyland, a pediatric pulmonologist. Dr. Weyland suspects that baby Zoey may be suffering from cystic fibrosis.

CF affects more than 30,000 kids and young adults in the United States. It disrupts the normal function of epithelial cells — cells that make up the sweat glands in the skin and that also line passageways inside the lungs, pancreas, and digestive and reproductive systems.

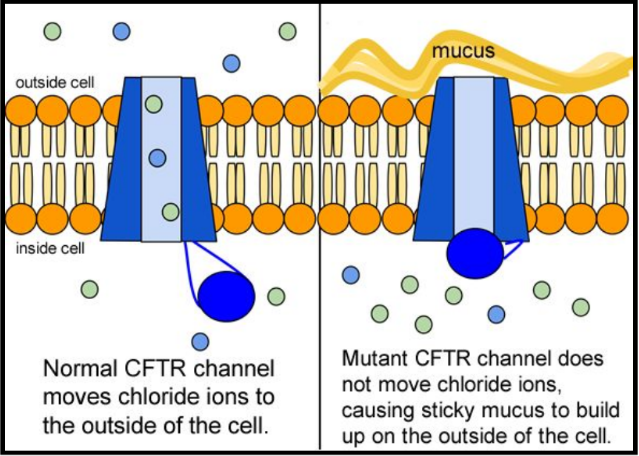

The inherited CF gene directs the body's epithelial cells to produce a defective form of a protein called CFTR (or cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) found in cells that line the lungs, digestive tract, sweat glands, and genitourinary system.

When the CFTR protein is defective, epithelial cells can't regulate the way that chloride ions pass across cell membranes. This disrupts the balance of salt and water needed to maintain a normal thin coating of mucus inside the lungs and other passageways. The mucus becomes thick, sticky, and hard to move, and can result in infections from bacterial colonization.

- "Woe to that child which when kissed on the forehead tastes salty. He is bewitched and soon will die" This is an old saying from the eighteenth century and describes one of the symptoms of CF (salty skin). Why do you think babies in the modern age have a better chance of survival than babies in the 18th century?

- What symptoms lead Dr. Weyland to his initial diagnosis?

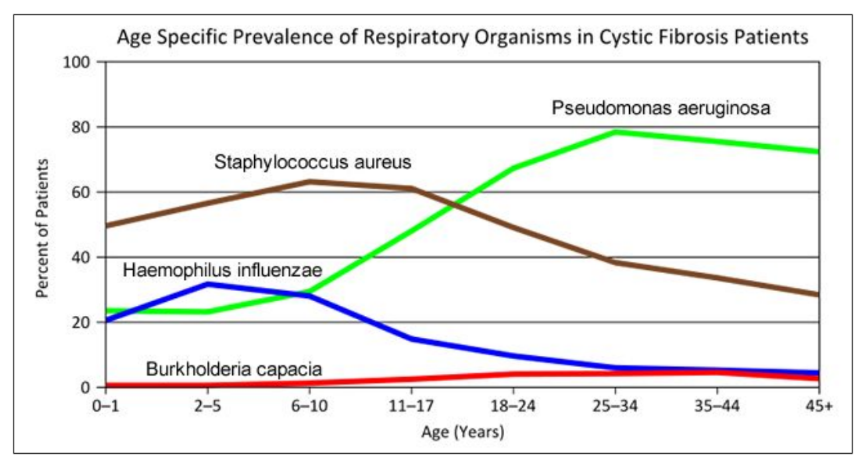

- Consider the graph of infections, which organism stays relatively constant in numbers over a lifetime. What organism is most likely affecting baby Zoey?

- What do you think is the most dangerous time period for a patient with CF? Justify your answer.

Part II: CF is a disorder of the cell membrane.

Imagine a door with key and combination locks on both sides, back and front. Now imagine trying to unlock that door blind-folded. This is the challenge faced by David Gadsby, Ph.D., who for years struggled to understand the highly intricate and unusual cystic fibrosis chloride channel – a cellular doorway for salt ions that is defective in people with cystic fibrosis.

His findings, reported in a series of three recent papers in the Journal of General Physiology, detail the type and order of molecular events required to open and close the gates of the cystic fibrosis chloride channel, or as scientists call it, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR).

Ultimately, the research may have medical applications, though ironically not likely for most cystic fibrosis patients. Because two-thirds of cystic fibrosis patients fail to produce the cystic fibrosis channel altogether, a cure for most is expected to result from research focused on replacing the lost channel.

5. Suggest a molecular fix for a mutated CFTR channel. How would you correct it if you had the ability to tinker with it on a molecular level?

6. Why would treatment that targets the CFTR channel not be effective for 2⁄3 of those with cystic fibrosis?

7. Sweat glands cool the body by releasing perspiration (sweat) from the lower layers of the skin onto the surface. Sodium and chloride (salt) help carry water to the skin's surface and are then reabsorbed into the body. Why does a person with cystic fibrosis have salty tasting skin?

Part III: No cell is an island

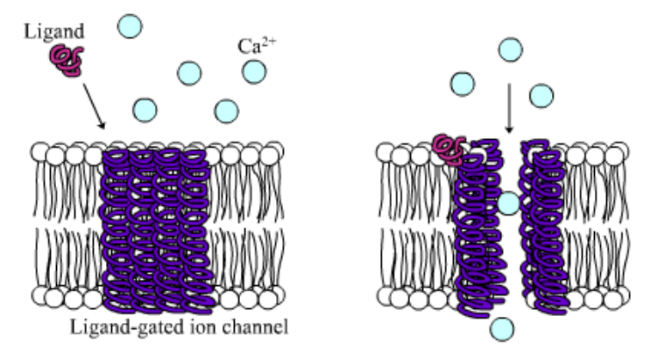

Like people, cells need to communicate and interact with their environment to survive. One way they go about this is through pores in their outer membranes, called ion channels, which provide charged ions, such as chloride or potassium, with their own personalized cellular doorways. But, ion channels are not like open doors; instead, they are more like gateways with high-security locks that are opened and closed to carefully control the passage of their respective ions.

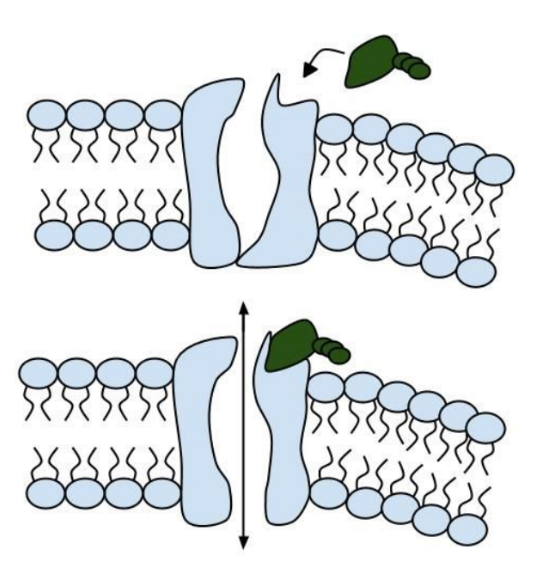

In the case of CFTR, chloride ions travel in and out of the cell through the channel’s guarded pore as a means to control the flow of water in and out of cells. In cystic fibrosis patients, this delicate salt/water balance is disturbed, most prominently in the lungs, resulting in thick coats of mucus that eventually spur life-threatening infections. Shown below are several mutations linked to CFTR:

8. Which mutation do you think would be easiest to correct. Justify your answer. 9. Consider what you know about proteins, why does the “folding” of the protein matter?

Part IV: Open sesame

Among the numerous ion channels in cell membranes, there are two principal types: voltage-gated and ligand-gated. Voltage-gated channels are triggered to open and shut their doors by changes in the electric potential difference across the membrane. Ligand-gated channels, in contrast, require a special “key” to unlock their doors, which usually comes in the form of a small molecule.

CFTR is a ligand-gated channel, but it’s an unusual one. Its “key” is ATP, a small molecule that plays a critical role in the storage and release of energy within cells in the body. In addition to binding the ATP, the CFTR channel must snip a phosphate group – one of three “P’s” – off the ATP molecule to function. But when, where and how often this crucial event takes place has remains obscure.

10. Compare the action of the ligand-gated channel to how an enzyme works.

11. Consider the model of the membrane channel, What could go wrong to prevent the channel from opening?

12. Where is ATP generated in the cell? How might ATP production affect the symptoms of cystic fibrosis?

13. Label the image below to show how the ligand-gated channel for CFTR works. Include a summary.

Part V: Can a Drug Treat Zoey’s Condition?

Dr. Weyland confirmed that Zoey does have cystic fibrosis and called the parents in to talk about potential treatments. “Good news, there are two experimental drugs that have shown promise in CF patients. These drugs can help Zoey clear the mucus from his lungs. Unfortunately, the drugs do not work in all cases.” The doctor gave the parents literature about the drugs and asked them to consider signing Zoey up for trials.

The Experimental Drugs

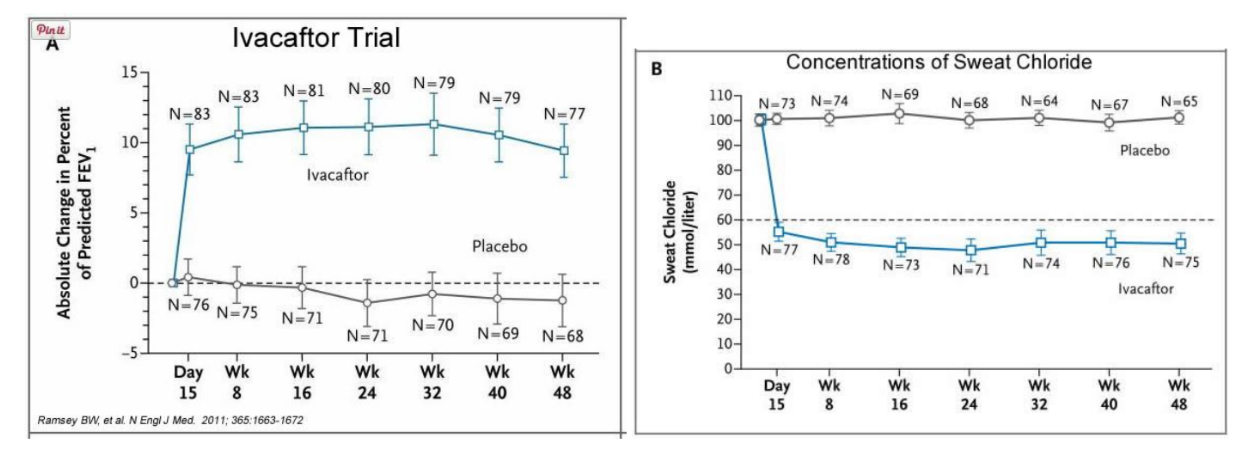

Ivacaftor TM is a potentiator that increases CFTR channel opening time. We know from the cell culture studies that this increases chloride transport by as much as 50% from baseline and restores it closer to what we would expect to observe in wild type CFTR. Basically, the drug increases CFTR activity by unlocking the gate that allows for the normal flow of salt and fluids.

In early trials, 144 patients all of whom were age over the age of 12 were treated with 150 mg of Ivacaftor twice daily. The total length of treatment was 48 weeks. Graph A shows changes in FEV (forced expiratory volume) with individuals using the drug versus a placebo. Graph B shows concentrations of chloride in patient’s sweat.

14. What is FEV? Describe a way that a doctor could take a measurement of FEV.

15. Why do you think it was important to have placebos in both of these studies?

16. Which graph do you think provides the most compelling evidence for the effectiveness of Ivacafor? Defend your choice.

17. Take a look at the mutations that can occur in the cell membrane proteins from Part III. For which mutation do you think Ivacaftor will be most effective? Justify your answer.

18. Would you sign Zoey up for clinical trials based on the evidence? What concerns would a parent have before considering an experimental drug?

Part VI: Zoey’s Mutation

Dr. Weyland calls a week later to inform the parents that genetic tests show that Zoey chromosomes show that she has two copies of the F508del mutation. This mutation, while the most common type of CF mutation, is also one that is difficult to treat with just Ivacaftor. There are still some options for treatment.

In people with the most common CF mutation, F508del, a series of problems prevents the CFTR protein from taking its correct shape and reaching its proper place on the cell surface. The cell recognizes the protein as not normal and targets it for degradation before it makes it to the cell surface. In order to treat this problem, we need to do two things: first, an agent to get the protein to the surface, and then ivacaftor (VX-770) to open up the channel and increase chloride transport. VX-809 has been identified as a way to help with the trafficking of the protein to the cell surface. When added VX-809 is added to ivacaftor (now called Lumacaftor,) the protein gets to the surface and also increases in chloride transport by increasing channel opening time.

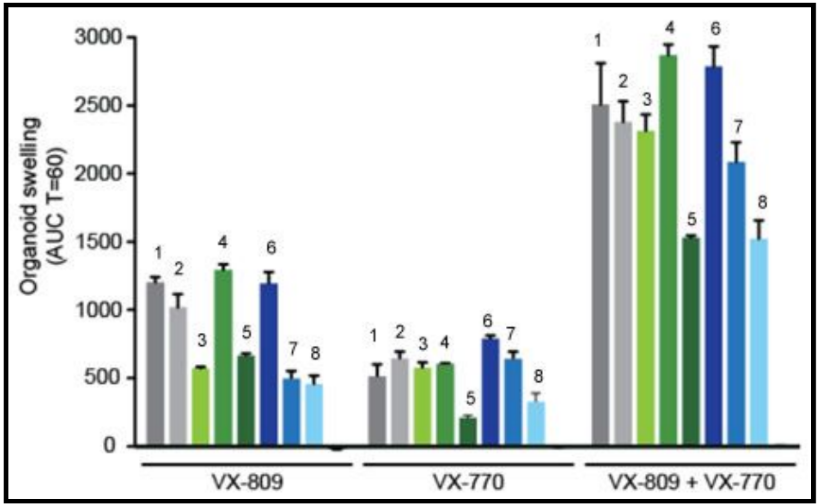

In early trials, experiments were done in-vitro, where studies were done on cell cultures to see if the drugs would affect the proteins made by the cell. General observations can be made from the cells, but drugs may not work on an individual’s phenotype. A new type of research uses ex-vivo experiments, where rectal organoids (mini-guts) were grown from rectal biopsies of the patient that would be treated with the drug. Ex-vivo experiments are personalized medicine, each person may have different correctors and potentiators evaluated using their own rectal organoids. The graph below shows how each drug works for 8 different patients (#1-#8)

19. Compare ex-vivo trials to in-vitro trials.

20. One the graph, label the group that represents Ivacaftor and Lumacaftor. What is the difference between these two drugs?

21. Complete a CER Chart. If the profile labeled #7 is Zoey, rank the possible drug treatments in order of their effectiveness for her mutation. This is your CLAIM. Provide EVIDENCE to support your claim. Provide REASONING that explains why this treatment would be more effective than other treatments and why what works for Zoey may not work for other patients. This is where you tie the graph above to everything you have learned in this case. Attach a page.

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 19: Case Study: Cystic Fibrosis

Julie M. Skrzat; Carole A. Tucker

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Introduction.

- Examination: Age 2 Months

- Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Prognosis

- Intervention

- Conclusion of Care

- Examination: Age 8 Years

- Examination: Age 16 Years

- Recommended Readings

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

C ystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive condition affecting approximately 30,000 Americans and 70,000 people worldwide. According to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation ( Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2019a ), approximately 1,000 new cases are diagnosed yearly in the United States, with a known incidence of 1 per 3,900 live births. The disease prevalence varies greatly by ethnicity, with the highest prevalence occurring in Western European descendants and within the Ashkenazi Jewish population.

The CF gene, located on chromosome 7, was first identified in 1989. The disease process is caused by a mutation to the gene that encodes for the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein. This mutation alters the production, structure, and function of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), a dependent transmembrane chloride channel carrier protein found in the exocrine mucus glands throughout the body. The mutated carrier protein is unable to transport chloride across the cell membrane, resulting in an electrolyte and charge imbalance. Diffusion of water across the cell membrane is thus impaired, resulting in the development of a viscous layer of mucus. The thick mucus obstructs the cell membranes, traps nearby bacteria, and incites a local inflammatory response. Subsequent bacterial colonization occurs at an early age and ultimately this repetitive infectious process leads to progressive inflammatory damage to the organs involved in individuals with CF.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

Cystic fibrosis is caused by mutations in the gene responsible for producing the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein. For this reason, scientists are exploring ways to provide a correct copy of the gene to treat CF.

Our cells contain DNA, a molecule that stores all the genetic information needed to make proteins. A gene is a specific sequence of DNA that carries the instructions for making a protein.

In non-integrating gene therapy, a piece of DNA with a correct copy of the CFTR gene is delivered to an individual's cells, but the DNA remains separate from the genome and is not permanent.

In integrating gene therapy, a piece of DNA that contains a correct version of the CFTR gene would be delivered to an individual's cells. The new copy of the CFTR gene would then become a permanent part of their genome.

What Is Gene Therapy ?

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene contains the instructions for making the CFTR protein . When there is a mutation — or alteration — in the genetic instructions, the production of the CFTR protein may be affected. In people with cystic fibrosis, mutations in the CFTR gene can result in no protein , not enough protein, or the protein being made incorrectly. Each of these defects leads to a cascade of problems that affect the lungs and other organs.

Since the discovery of the CFTR gene in 1989, scientists have been trying to find ways to correct the mutations in the gene that cause CF. Although progress was initially slower than anticipated, scientific breakthroughs in the past 10 years have accelerated advances in gene therapy, also known as gene transfer or gene replacement.

Gene therapy is a process in which a new, correct version of the CFTR gene would be placed into the cells in a person's body. Although the mutant copies of the CFTR gene would still be there, the presence of the correct copies would give cells the ability to make normal CFTR proteins.

Watch this animation to see how this might work.

Types of Gene Therapy: Non-Integrating vs. Integrating

There are two types of gene therapy that have potential to treat CF. It is not yet clear which option will work best. The process of physically delivering gene therapy technology to cells is full of challenges that would have to be overcome for any gene therapy to work.

To learn more about these challenges, watch this video:

Non-Integrating Gene Therapy

In non-integrating gene therapy, a piece of DNA with a correct copy of the CFTR gene is provided to an individual's cells, but the DNA remains separate from the genome and is not permanent. This is like placing a new page between the covers of an existing book without permanently attaching it. Even though the gene therapy does not become part of the genome, the cell can still use the new copy of the CFTR gene to make normal CFTR proteins.

A major advantage of the non-integrating gene therapy approach is that it does not disrupt the rest of the genome, just like adding a new page right under the cover of a book would not disturb the contents of the rest of the book. That means that the risk of side effects, including cancer , is low. A disadvantage of non-integrating gene therapy is that it is not permanent. The effect of the gene therapy might last only for several weeks or months. A person with CF would probably need to be treated with the gene therapy repeatedly for it to be effective.

Non-integrating gene therapy has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat a rare type of blindness, and it has also been shown to work in studies for hemophilia, a blood clotting disorder. In a clinical trial in England, people with CF were given a dose of a non-integrating gene therapy once per month for a year. The study indicated that the CF gene therapy was safe and resulted in a small improvement in lung function . A clinical trial in the U.S. is currently studying the safety and tolerability of non-integrating gene therapy in people with CF.

Integrating Gene Therapy

In integrating gene therapy, a piece of DNA that contains a correct version of the CFTR gene would be delivered to an individual’s cells. The new copy of the CFTR gene would then become a permanent part of their genome, which is the entire set of genetic instructions that is in every cell. This kind of gene therapy is like binding a new page into an existing book.

An advantage of an integrating gene therapy is that it is permanent for the life of the cell. This means that a person with CF might have to receive the gene therapy only once or a few times in their life. A disadvantage is that there may be limited control over where the new copy of the CFTR gene integrates into the genome. The new copy could be inserted into a part of the genome that contains some critical information, like the new page being randomly added to a book and disrupting an important chapter. This means integrating gene therapy could have undesirable side effects, such as increasing the risk of cancer.

A type of integrating gene therapy, known as CAR-T therapy, has already been approved to treat patients with certain kinds of leukemia and lymphoma. Integrating gene therapies to treat CF are being tested in the lab, and a clinical trial to test the safety of this approach in people with CF could happen in the next several years.

To learn more about several key types of lung cells that could be targeted by genetic therapies, including gene therapy, watch this video.

mRNA Therapy for Cystic Fibrosis Article | 3 min read

Gene Editing for Cystic Fibrosis Article | 6 min read

Gene Delivery for Cystic Fibrosis Article | 7 min read

Basics of the CFTR Protein Article | 5 min read

Hear directly from CF researchers and clinicians as they discuss everything you need to know about gene therapies at ResearchCon, April 30 – May 1.

( 1-800-344-4823 ) Mon - Thu, 9 am - 7 pm ET Fri, 9 am - 3 pm ET

- Gene Therapy

Gene Therapy Case Study: Cystic Fibrosis

- Open access

- Published: 15 April 2024

The effect of respiratory muscle training on children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- WenQian Cai 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Meng Li 3 na1 ,

- Yi Xu 3 na1 ,

- JiaNan Wang 1 , 2 ,

- YaHui Zuo 1 , 2 &

- JinJin Cao 4

BMC Pediatrics volume 24 , Article number: 252 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Cystic fibrosis is a chronic genetic disease that can affect the function of the respiratory system. Previous reviews of the effects of respiratory muscle training in people with cystic fibrosis are uncertain and do not consider the effect of age on disease progression. This systematic review aims to determine the effectiveness of respiratory muscle training in the clinical outcomes of children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis.

Up to July 2023, electronic databases and clinical trial registries were searched. Controlled clinical trials comparing respiratory muscle training with sham intervention or no intervention in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. The primary outcomes were respiratory muscle strength, respiratory muscle endurance, lung function, and cough. Secondary outcomes included exercise capacity, quality of life and adverse events. Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed study quality using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 2. The certainty of the evidence was assessed according to the GRADE approach. Meta-analyses where possible; otherwise, take a qualitative approach.

Six studies with a total of 151 participants met the inclusion criteria for this review. Two of the six included studies were published in abstract form only, limiting the available information. Four studies were parallel studies and two were cross-over designs. There were significant differences in the methods and quality of the methodology included in the studies. The pooled data showed no difference in respiratory muscle strength, lung function, and exercise capacity between the treatment and control groups. However, subgroup analyses suggest that inspiratory muscle training is beneficial in increasing maximal inspiratory pressure, and qualitative analyses suggest that respiratory muscle training may benefit respiratory muscle endurance without any adverse effects.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that although the level of evidence indicating the benefits of respiratory muscle training is low, its clinical significance suggests that we further study the methodological quality to determine the effectiveness of training.

Trial registration

The protocol for this review was recorded in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under registration number CRD42023441829.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a multisystem autosomal recessive disease that affects approximately 90,000 individuals, according to data from CF registries worldwide [ 1 , 2 ]. This is caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) gene, leading to a decrease or loss in the function of the CFTR protein [ 2 , 3 ]. Many studies have shown that this foundational flaw causes irreversible, progressive lung disease to start very early in life in people with cystic fibrosis (CF) [ 2 , 4 , 5 ]. CFTR is responsible for transporting chloride ions across the apical membrane of tissue epithelial cells, secreting bicarbonate to regulate the pH of the fluid on the airway surface, and inhibiting epithelial sodium channels (ENaC). Mutations in the CFTR gene lead to dehydration and the production of thick secretions in organs such as the reproductive, digestive, and respiratory tracts [ 1 , 2 , 6 ]. Thickened mucus in the lungs sticks to the surface of the airways, reducing the amount of mucociliated tracts cleared and raising the risk of infection and inflammation, which progressively damages the lungs [ 2 , 7 ]. As a result, breathing becomes more difficult, and gas exchange is reduced. This lowers exercise tolerance and eventually leads to respiratory failure, the main cause of death from cystic fibrosis [ 2 , 8 ].

More recently, the introduction of CFTR modulator medications can correct basic deficiencies [ 2 , 9 , 10 ], which in time may alter the manifestations and complications of CF. Nevertheless, a cure for this condition is not currently available, and ongoing rehabilitation is necessary due to its chronic nature. Therefore, it is crucial to develop or improve the therapeutic approaches aimed at preserving or improving lung function for the well-being of patients with cystic fibrosis. The effective intervention recently is physical exercise [ 2 , 11 ], including respiratory muscle training (RMT) [ 2 , 12 ]. The goal of respiratory muscle training is to enhance expiratory and/or inspiratory muscular strength and endurance in order to improve respiratory function. Respiratory muscle training has demonstrated efficacy in individuals diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [ 2 , 13 , 14 ] and those suffering from various respiratory conditions [ 2 , 15 , 16 ]. It is yet unknown, nevertheless, if respiratory muscle training helps patients with cystic fibrosis. The last systematic review on this topic was published in 2020. Ten randomized controlled trials assessing the impact of respiratory muscle training on individuals with cystic fibrosis were included in the analysis. Nonetheless, the authors conclude that there is insufficient data to support the use of RMT in cystic fibrosis. The primary cause of this result is the poor methodological quality of the individual research [ 2 ].

Several research studies have suggested that respiratory muscle training could potentially improve mucus removal from the lungs, which is a fundamental aspect of preventing pulmonary infections [ 2 , 17 , 18 ]. At the same time, it has been proposed that respiratory muscle training could enhance lung function, exercise capacity, and health-related quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis [ 19 ]. The aforementioned trials have a limited sample size and significant protocol variances, and despite the possible advantages of respiratory muscle training, none of them have shown strong proof of a significant increase in clinical outcomes to yet. Concurrently, recent Cochrane reviews did not consider the distinction between pediatric and adult populations with cystic fibrosis [ 2 ]. The interplay of age and disease progression in CF may lead to age-related physiological variations that can impact the adaptability and reaction of respiratory muscle training. These variations are likely to influence the effectiveness of any intervention strategies.

Thus, the primary goals of this study were to examine the efficacy of respiratory muscle training in terms of respiratory muscle function, lung function,exercise capacity, and quality of life in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) has the protocol for this review registered under registration number CRD42023441829. The presentation of the results of this review followed the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [ 20 ].

Criteria for eligibility

Study designs.

All studies retrieved through the search were evaluated for eligibility based on four inclusion criteria: study or design type, population, intervention, and reported outcomes. The inclusion criteria encompassed parallel or cross-over randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing respiratory muscle training (RMT) with control groups.

Participants

Based on the World Health Organization's (WHO) classification, this meta-analysis concentrated on children (≥ 5 years old) and adolescents with CF (≤ 19 years old). They were diagnosed with CF through sweat testing, genotyping, or both. Studies involving mixed age groups of children and adults with CF were excluded from the analysis unless their data could be segregated and reported separately.

Interventions

Regarding interventions, the review included research that implemented a respiratory muscle training program, specifically either inspiratory muscle training(IMT) or expiratory muscle training(EMT), irrespective of the specific equipment utilized. The inclusion criteria did not impose limitations on the dosage, timing, location, or supervision of the intervention. Additionally, the review did not restrict the type of control group, whether passive (no intervention) or active (sham). However, research that combined respiratory muscle training with any other type of physical exercise training were not included in the review.

In the main included papers, it is necessary for at least one of the specified outcomes to be reported. The primary outcomes of the review focused on: respiratory muscle function such as respiratory muscle strength (maximum inspiratory pressure (MIP) and maximum expiratory pressure (MEP)) and respiratory muscle endurance, and lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV 1 ), forced vital capacity (FVC), and cough level), where cough level assessment included quantification of forced expiratory maneuvers (peak expiratory flow (PEF)) or maximum expiratory flow achieved during cough maneuvers (peak cough flow (PCF)). Secondary outcomes include assessments of exercise capacity, quality of life, and adverse events, regardless of measurement procedures.

Sources of information and search methodology

Until July 2023, the electronic databases that were referenced include PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, CNKI database, VIP database, Wan Fang database, and Chinese Biomedicine Literature Database (CBM). Depending on the database used, the search terms employed included MESH and Text words, in conjunction with free keywords utilizing the Boolean "and" and "OR" operators (Supplementary material Table S 1 ). Furthermore, an examination was conducted on two clinical trial registries, namely the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov. The reference lists of the incorporated studies and previously published systematic reviews were manually scrutinized. Only publications written in English or Chinese will be included in the literature search. Full-text versions were considered only when studies were accessible in full-text format or as conference abstracts.

Study records

Selection process.

The database was searched by principal investigators (CWQ). To ascertain which search results were eligible for inclusion, two reviewers (CWQ, LM) independently examined the results, and their conclusions were compared. When appropriate, we will contact the study authors for further information to address eligibility-related queries. If we are unable to come to an understanding, we shall address these matters and, if required, enlist the help of a third-party examiner (CJJ) to settle these disputes.

Data collection process

Two independent reviewers (CWQ, LM) extracted data using pre-structured forms to gather study characteristics and general information. We shall perform calibration activities prior to the evaluation in order to guarantee uniformity among reviewers. When a study has many publications, all reports are combined, and the data that is most complete is chosen for analysis. In addition, further information was requested from the study authors when needed. Ultimately, a third assessor (CJJ) or consensus are used to settle disagreements.

The following details were extracted: study information (authors, publication date); sample characteristics (size, age, and FEV1); interventions (type of respiratory muscle training device, resistance settings, duration, and frequency); control groups (no treatment, sham RMT/standard care); assessment procedures, and end results.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Two reviewers (CWQ, LM) independently evaluated the methodological rigor of the included studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool 2 (RoB 2) [ 21 ] The methodological criteria were: (1) randomization process; (2) deviations from intended interventions; (3) missing outcome data; (4) measurement of the outcome; (5) selection of the reported results, and (6) any other identified sources of bias. Based on this tool, the studies were classified as high-risk, low-risk, or unclear. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus. We will generate visual representations of potential bias within and across studies using RevMan 5.4 (Review Manager 5.4).

Data synthesis

A table qualitatively described the features of the included studies. Statistical software RevMan 5.4 will be utilized to combine and calculate each outcome, adhering to the statistical guidelines outlined in the current edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. In cases where essential data were absent from a study, corresponding authors were approached for clarification. Results were narratively described in instances where data were insufficient for meta-analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

When data for continuous outcomes (pulmonary function, exercise capacity and respiratory muscle function) were available, we calculated the mean differences (MD) by using pre- and post-intervention data and presented the results with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). There is currently no available data suitable for analysis of dichotomous outcomes. When aggregating findings from crossover studies for meta-analysis, we would employ the inverse variance method as suggested by Elbourne [ 22 ]. In cases where data are scarce, our approach would involve utilizing solely first-arm data or treating crossover trials as parallel trials, with the assumption that zero correlation represents the most cautious estimate.

If the study used the same tool to measure outcomes, the mean difference (MD) was utilized as the effect size. In cases where different measurement tools were utilized across studies, standard mean differences (SMDs) were employed as the effect size. All effect sizes were reported with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Given the limited number of studies included, a random-effects model was employed in all analyses to ascertain the overall effect size, irrespective of the level of heterogeneity. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We intended to use a standard Chi-square test with an alpha threshold of significance set at P < 0.05 to investigate heterogeneity between comparable studies. We would have used the I 2 statistic to calculate the levels of heterogeneity; an I 2 of more than 50% would be regarded as significant heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis or Sensitivity analysis

The following factors were subjected to a subgroup analysis: type of respiratory muscle training.

We did not conduct a scheduled sensitivity analysis to assess the potential impact of bias in the included studies on the reliability of our findings, as there were an insufficient number of studies available for analysis.

Confidence in cumulative evidence

Using the GRADE method, two reviewers (CWQ, LM) evaluated the quality of the evidence for each outcome [ 23 ]. The domains of bias risk, consistency, directness, precision, and reporting bias are taken into account by this paradigm. We reduced the credibility of the data by one level in cases of serious risk and by two levels in instances of very serious risk. Any discrepancies were resolved through mutual agreement.

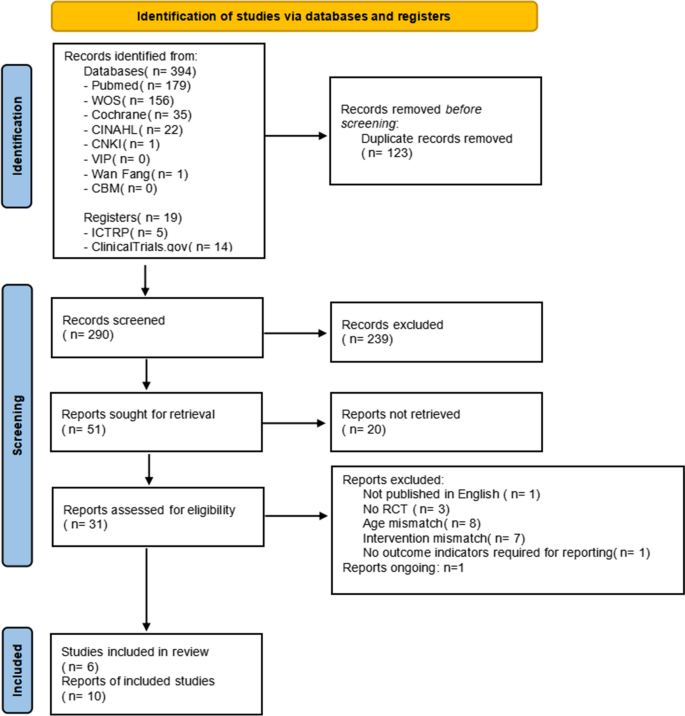

Search results

After conducting an electronic search, 394 records were discovered, and 19 additional records were retrieved from alternative search sources. 290 records were screened after duplicates were removed, and 239 of those were disqualified during the title and abstract review phase because they did not satisfy a minimum of one qualifying criterion. Twenty of the 51 records that were examined could not be retrieved in their entirety, and 21 were excluded (see Supplementary material Table S 2 for the reasons for exclusion). The two key reasons for rejection were study population and design non-compliance. Ultimately, 10 records—representing 6 different studies—met the eligibility requirements [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Additionally, 1 ongoing study was identified (Supplementary material Table S 2 ), which is found in ICTRP.

Regretfully, the reviewers were unable to get any information from the researchers. After the procedure was completed, two studies did not provide data on mean and standard deviation, leaving four studies for quantitative analysis [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 29 ]. Figure 1 displays the PRISMA flowchart for the review procedure.

Flow diagram of the included studies

Characteristics of the included studies

Table 1 describes the features of the six included studies. Four of the studies that met the eligibility criteria were available as full-text publications [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 29 ], with one of them utilizing a crossover design [ 29 ]. The remaining two studies were exclusively released as conference proceedings, and all were designed as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [ 24 , 28 ]. The six studies were carried out in a variety of high-income nations. Two studies were conducted in Turkey [ 25 , 26 ], two in Switzerland [ 28 , 29 ], the rest in Austria [ 24 ] and the USA [ 27 ]. There were 151 total participants in the trials that were included, with a mean age of 6 to 18 years old and 50.9% of them being female.

The included studies varied greatly in terms of the training level and methodology. For the intervention, three of the selected studies applied inspiratory muscle training [ 24 , 26 , 27 ], while one used expiratory muscle training [ 25 ]. The four aforementioned studies focused on respiratory muscle strength training using pressure threshold loading. In contrast, Beilil et al. [ 28 , 29 ] conducted respiratory muscle endurance training. The intensity of training varied across the studies, with most targeting a range of 30% to 60% of maximum inspiratory pressure and/or maximum expiratory pressure. The progression was based on a periodic reassessment of the maximum inspiratory/expiratory pressure. RMT was conducted for a duration of 10–30 min, once or twice a day, 5–7 days per week, over a total period of 6 to 12 weeks. In the control groups, two studies used sham respiratory muscle training, using 5 cmH 2 O of load or 10% of the maximum inspiratory pressure [ 25 , 27 ], and three studies used standard care as the control [ 26 , 28 , 29 ]. Additionally, Albinni et al. [ 24 ] conducted a comparison between the use of a cycle ergometer alone and the addition of inspiratory muscle training.

Also, there was a wide range in the outcome measures that the research chose. All studies reported at least one measure of lung function, principally FEV 1 and FVC. Expiratory muscle training by Emirza et al. also reported PEF. Exercise capacity was reported by all studies, specifically 6-min walking distance (6MWD) [ 25 , 26 ], maximum oxygen uptake (VO 2 max) [ 24 ]and exercise duration [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Three studies used the Cystic Fibrosis Clinical Score (CFCS) or the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire (CFQ) to measure health-related quality of life [ 25 , 28 , 29 ]. Two studies assessed the level of adherence with the training regimen [ 25 , 26 ] 97.9% (SD 4.2) and 97.5% (SD 5.7) for the experimental group and 97.5% (SD 5.7) for the control group, respectively, were the findings of one study; [ 26 ] Another study reported excellent adherence without providing specific numerical data [ 25 ].

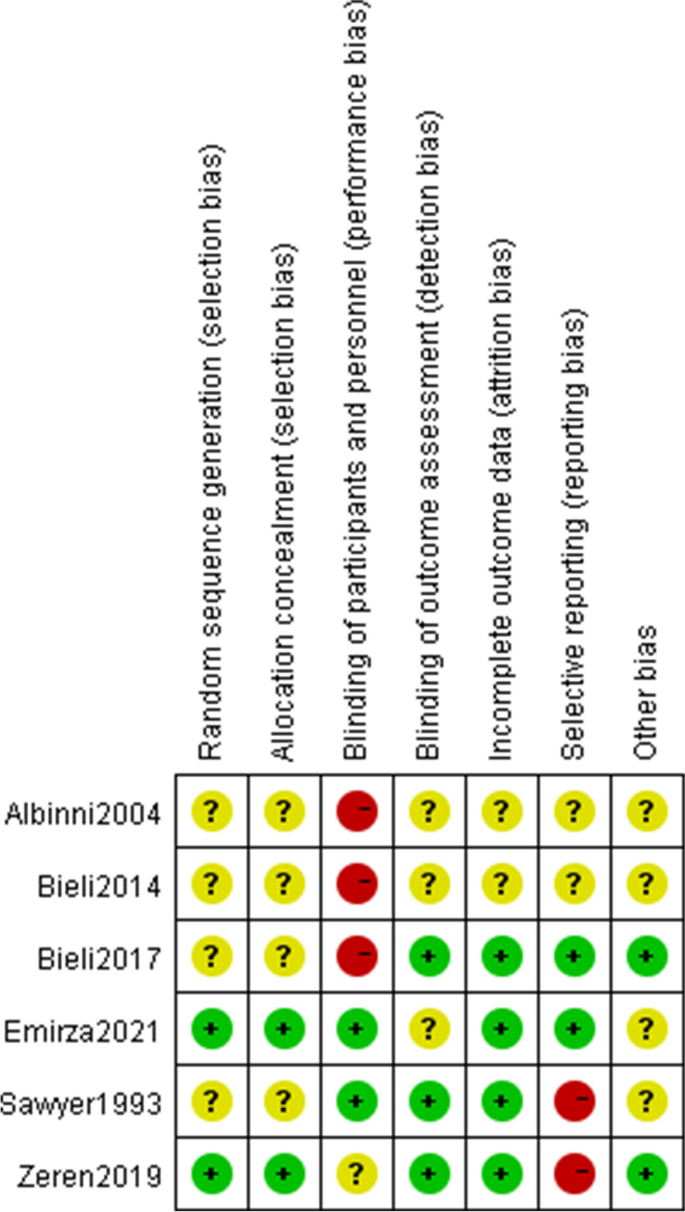

Risk of bias assessment

The majority of included studies had bias risk across all ROB2 domains. The evaluation results were shown in Fig. 2 .

Risk of bias summary

Four of the studies that were considered had ambiguous allocation concealment and random sequence creation (randomness of participant allocation) [ 24 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Most just mentioned that the participants were placed into their groups at random, they did not elaborate on the randomization procedure. It is quite challenging to conduct double blind research in respiratory muscle training. Two studies were rated as having low performance bias because of the use of sham controls [ 25 , 27 ]. In the study of zeren et al., although patients knew which interventions they were doing, the control group also measured maximum inspiratory pressure values weekly to mitigate the impact of the interventions, so the risk of bias of the zeren et al. study was unclear [ 26 ]. Three studies presented with low risk of detection bias (blinding to the outcomes), the assessors did not know the allocation scheme [ 26 , 27 , 29 ], whilst the other studies were unclear due to lack of information.

Regarding incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), the risk of two conference proceedings was unclear [ 24 , 28 ] and the remaining studies were at low risk. The intention-to-treat concept was addressed in the Bieli et al. study. Of the 22 participants, 6 withdrew from the trial, and 4 of them stopped during the control period, indicating that the withdrawal was not directly related to the intervention. Moreover, participants who withdrew did have a tendency to age and have features of more advanced lung disease. We assessed the Bieli et al. study as having a minimal risk of bias [ 29 ]. Additionally, we evaluated another study as having a low risk of bias, although some participants did not complete all training sessions, the reported good adherence was insufficient to affect the outcome analysis [ 26 ]. Data were dropped in two studies, both explaining the reasons for the dropout and did not affect the outcome analysis [ 25 , 27 ].

For reporting bias/selective reporting (selection of outcomes reported in published articles), two studies were classified as high risk because they did not report all prespecified outcomes [ 26 , 27 ]. Two studies provided data on all chosen outcome measures, thus indicating a low likelihood of selective reporting bias in the studies [ 25 , 29 ]. The publications did not provide enough information to assess the risk of bias, and as a result, they have been deemed to have an unclear risk of bias [ 24 , 28 ].

Effects of intervention and certainty of evidence

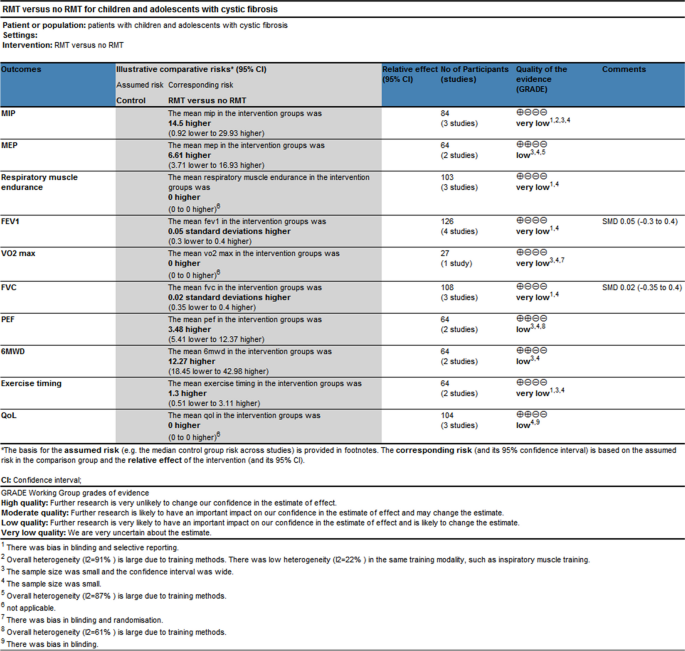

The quantitative analysis did not include two of the papers that were part of this review [ 24 , 28 ]. One study provided information on the overall research participants without specifying for each intervention and control group [ 28 ]. It is impossible to estimate the standard deviation from another study because the exact p -value and 95% confidence interval of the mean difference within or between groups were not provided [ 24 ]. As a result, meta-analyses based on the final four studies were carried out. For every meta-analysis, the quality of the evidence was graded as poor or very low (Fig. 3 ), mostly because of the imprecision resulting from the small sample size overall and the quality of the studies.

GRADE Summary of findings

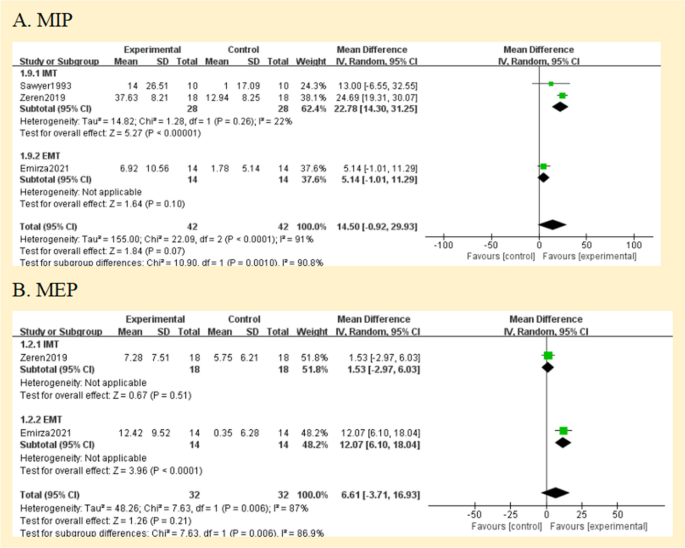

Comparison 1 respiratory muscle strength and endurance

Four studies had documented maximum inspiratory pressures [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Comparisons between the RMT and control groups were presented based on pooled data analysis of three studies (84 patients) [ 25 , 26 , 27 ]. The overall MD was 14.50 cmH 2 O [95%CI -0.92; 29.93] and overall effect Z = 1.84 ( p = 0.07) (Fig. 4 A) (very low certainty of evidence; see Fig. 3 ). One study was excluded from the analysis due to insufficient data [ 24 ]. The omitted study identified a significant maximal inspiratory pressure improvement in the experimental group. Subgroup analyses of studies using IMT alone revealed higher improvements in the experimental groups' maximal inspiratory pressure when compared to the control groups; The overall MD was 22.78 cmH 2 O [95%CI 14.30; 31.25]. The heterogeneity of the comparison was low (I 2 = 22%) (Fig. 4 A). Nevertheless, no significant differences were seen in subgroup analyses conducted just utilizing EMT.

Pooled analysis of respiratory muscle strength. Abbreviation: IMT, inspiratory muscle training; EMT, expiratory muscle training; MIP, maximal inspiratory pressure; MEP, maximal expiratory pressure

The maximal expiratory pressure (MEP) was assessed in 2 studies [ 25 , 26 ]. MEP also did not favour experimental interventions overall. The overall MD was 6.61 cmH 2 O [95%CI -3.71; 16.93] (Fig. 4 B) (low certainty of evidence; see Fig. 3 ). But in the EMT subgroup, maximal expiratory pressure favour experimental interventions [MD = 12.07 cmH 2 O, 95% CI 6.10; 18.04].

The endurance of respiratory muscles was evaluated in 3 studies [ 24 , 28 , 29 ] using varying methodologies, two studies had insufficient data [ 24 , 28 ], so a meta-analysis was not possible. The quality of evidence was deemed to be of very low (Fig. 3 ). According to two studies, the training group's respiratory muscle endurance improved ( P < 0.01) [ 24 , 28 ]. At a 70% MVV breathing performance, Bieli et al. [ 29 ]similarly discovered that the training group's respiratory muscle endurance was longer ( P < 0.01).

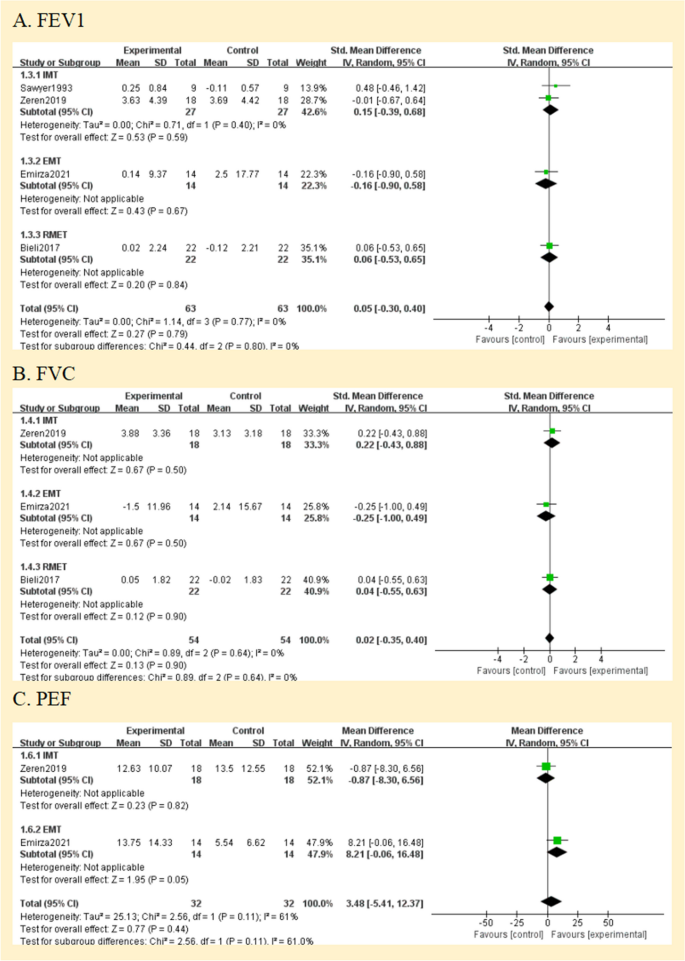

Comparison 2 lung function

All studies assessed lung function. They reported lung function in eitherlitres (L) [ 27 , 28 ], % predicted [ 25 , 26 ] or using the z score; [ 29 ] one study did not define the unit of measurement in the two published abstracts [ 24 ]. Therefore, analyses were performed with SMD. The forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV 1 ), forced vital capacity (FVC), and peak expiratory flow (PEF) were compared between the RMT and control groups in Fig. 5 . Regarding the assessment of the effect on FEV 1 and FVC, there was no heterogeneity between the trials (I 2 = 0%; p = 0.77 and I 2 = 0%; p = 0.64, respectively); however, PEF was very significant. (I 2 = 61%; p = 0.11) (Fig. 5 A, B, and C). None of the pooled parameters showed any discernible variations. Two studies that were not included in the meta-analysis reported no significant benefit of RMT in terms of lung function [ 24 , 28 ]. The only one is that in the subgroup analysis of PEF, EMT has significant benefits for PEF [MD = 8.21, 95% CI -0.06; 16.48]. We judged the quality of the evidence for FEV 1 and FVC to be very low, and the quality of the evidence for PEF to be low (Fig. 3 ).

Pooled analysis of pulmonary function. Abbreviation: IMT, inspiratory muscle training; EMT, expiratory muscle training; RMET: respiratory muscle endurance training; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; PEF: peak expiratory flow

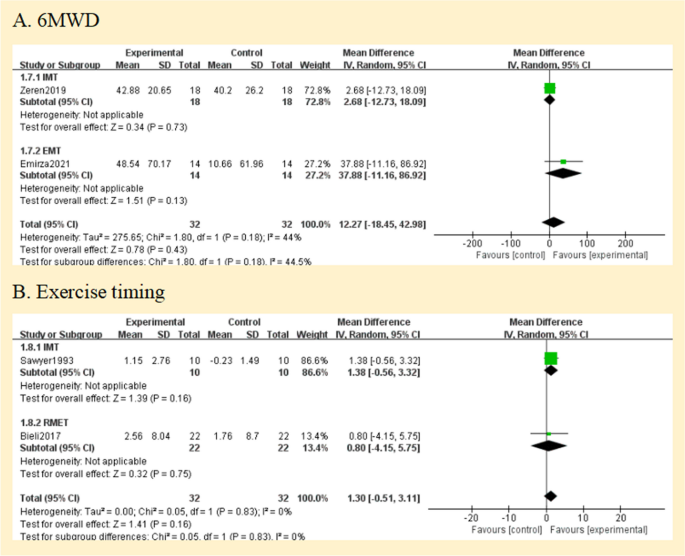

Comparison 3 exercise capacity

Two studies reported the exercise capacity as measured by the distance covered during the 6-min walking test [ 25 , 26 ]. While the distance achieved improved from baseline in both studies during the study, there was no difference in between group comparisons of change from baseline. Pooled data analysis showed no significant differences for the distance walked[MD = 12.27 m, 95% CI -18.45; 42.98] between groups (low certainty of evidence; see Fig. 3 ). The level of heterogeneity was moderate (I 2 = 44%; p = 0.18) (Fig. 6 A).

Pooled analysis of exercise capacity. Abbreviation: IMT, inspiratory muscle training; EMT, expiratory muscle training; RMET, respiratory muscle endurance training; 6MWD, 6-min walking distance

Using the duration of the activity, three studies revealed the exercise capacity [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Analysis of pooled data from two studies (64 patients) compares the RMT and control groups [ 27 , 29 ]. The overall MD was 1.30 min [95%CI -0.51; 3.11] and overall effect Z = 1.41 ( p = 0.16) (Fig. 6 B) (low certainty of evidence; see Fig. 3 ). A study that compared groups indicated that working at 60% of maximal effort resulted in a 10% improvement ( P < 0.03) [ 27 ], but our subgroup analysis showed no statistically significant difference between groups ( p = 0.16).

Regarding maximum exercise capacity, this result was documented in one study [ 24 ]. Maximal exercise capacity was defined as maximal oxygen uptake (Vo 2max ). It only reported within-group improvements, with no data to allow inclusion in our analysis. We assessed the evidence quality to be of a very low standard (Fig. 3 ).

Health-related quality of life

Three studies reported a measure of health-related quality of life by using the CFQ or CFQ Revised (CFQ-R) [ 25 , 28 , 29 ]. Meta-analysis was impossible due to different versions. We judged the quality of the evidence to be low (Fig. 3 ). Emriza et al. used a revised version of the Turkish Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire (CFQ-R) [ 25 ]. The Turkish version of the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire-Revised (CFQ-R) consists of child form, parent form, and adolescent form over multiple domains(physical, emotion, vitality, school, eat, treat, social, body, health, weight, respiratory, digestive, role) [ 30 ]. For each CFQ-R domain, Emriza provided the overall score both before and after training. In the training group, there were significant changes in the children's physical function scores and parents' physical function, vitality, and health perception ( P < 0.05). In the comparison between the two groups, parents had variations in their scores on treatment burden, digestive symptoms, and vitality ( P < 0.05) [ 25 ]. Bieli et al. used German adaptation of the CFQ-14 + , but the study participants were not all over 14 years old, and the report did not explain this [ 29 ]. Bieli's utilization of the CFQ revealed no discernible disparity in the health-related quality of life across the various treatment groups.

The CF clinical score (CFCS), which Bieli also used to gauge symptom severity, shows overall symptom severity. However, neither at baseline nor during the intervention, there was a difference in symptom severity between the two groups [ 28 , 29 ].

This meta-analysis summarizes and analyzes the available evidence on the effects of RMT in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. This review examines the impact of age on the progression of CF and is the initial review of respiratory muscle training in children and adolescents with CF. The results suggest that the RMT program is an effective intervention to improve inspiratory/expiratory muscle strength in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. It also indicates that it may have a positive effect on respiratory muscle endurance with no adverse effects. Expiratory muscle training alone was superior to the control group in improving PEF. RMT did not improve lung function (FEV1, FVC), and the results were inconclusive regarding the benefits of exercise capacity and HRQoL.

The review's overall high risk of bias and small sample size have also led to a low or very low quality of evidence supporting these findings. Of the 6 included studies, only four (including 108 participants) were fully published papers [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ], highlighting the need for further research. Summary of conference proceedings limits the amount of detailed data provided, thereby limiting the data that can be extracted and reducing the rigor of the process.

Training regimens in studies varied widely, and no recommendations have been made on the load, intensity, or duration of training. Of the studies included in this review, 67% used a threshold loading device to transmit resistance (focusing on respiratory muscle strength) with a target intensity of 30% or 60% of maximum respiratory muscle strength [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. This result is consistent with the manufacturer's recommendations for effective inspiratory muscle training (strong breathing), which recommends at least 30% intensity. 33% hyperventilation by autonomic eucapnia (focusing on respiratory muscular endurance) [ 28 , 29 ].

Descriptive analysis of the studies showed that the indicators that best detect the effectiveness of the respiratory muscle training program were maximal inspiratory pressure, maximal expiratory pressure, and respiratory muscle endurance time. The included studies all showed improvements in respiratory muscle function in the trial group, but pooled meta-analyses of training interventions had no significant benefit. For the pre-specified subgroup analyses, due to the limited number of studies, only two studies were included in the inspiratory muscle training subgroup analyses, which showed greater improvement in maximal inspiratory pressure in the trial groups [ 26 , 27 ]. Individual studies that failed to perform subgroup analyses due to limited data also showed that EMT significantly improved expiratory muscle strength [ 25 ]. In addition, IMT does not improve expiratory muscle strength, and vice versa. This is consistent with respiratory muscle training results for other chronic respiratory diseases [ 31 , 32 ]. When the proper physiological load is applied, respiratory muscles respond to training in a manner comparable to that of any skeletal muscle since they are both physiologically and functionally skeletal muscles [ 33 ]. So if the patient can tolerate it, is it possible to conduct joint training to study the effect of the intervention, after all, meta-analyses have demonstrated that IMT + EMT can enhance both inspiratory and expiratory muscle strength [ 34 ].

Only three studies evaluated respiratory muscle endurance, and all of them had positive findings, although using two distinct techniques for assessment [ 24 , 28 , 29 ]. The results coincide with those observed in asthma [ 35 ]. Despite the fact that respiratory muscle pressure is the most widely used indicator of respiratory muscle function in clinical settings, endurance components of respiratory muscle function are important because of their impact on daily activities and their role in facilitating gas exchange and ventilation during physical activity [ 36 ]. Sawyer et al. [ 27 ] tried using an incremental loading procedure to assess the maximum working capacity of the inspiratory muscles, but many children did not perform this procedure correctly and therefore did not report results. Further assessments of respiratory muscle endurance could be beneficial in order to better comprehend the efficacy of RMT. Consequently, we think that assessing respiratory muscle endurance should be a part of future study, and it can be challenging to discover an appropriate way to measure it in youngsters.

According to the meta-analysis's findings, there was not a significant difference between the experimental and control groups' lung function tests (such as FEV 1 and FVC). There are other possible contributing variables to this finding. Firstly, inspiratory interventions do not alter expiratory indicators. Studies employed exhalation measurements primarily because they are applicable to ordinary clinical use and illness progression monitoring. Secondly, the effects of respiratory muscle training are short-lived and not sufficient to halt the natural decline of the lungs in these patients. Lastly, the baseline lung function, such as FEV 1 and FVC, near to the normal prediction range, and the effect of respiratory muscle training on them would not be evident given the features of the group included in the studies. This hypothesis may explain why Enright et al. achieved significant improvements in spirometry, with baseline predictive values of 64% for FEV 1 and 53% for FVC in their study, and the severity of lung deterioration in patients may have enhanced the benefit of RMT on spirometry [ 19 ]. Future studies may involve a larger sample of individuals with reduced lung function to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, extending the follow-up period could help confirm the long-term effectiveness of respiratory muscle training in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis.

Cough is a part of life for people with cystic fibrosis (CF), is the main mechanism of secretion clearance [ 37 ], and is directly related to respiratory muscle strength [ 38 , 39 ]. Quantitative assessment of cough capacity is typically conducted by measuring PCF, but there are currently no internationally accepted guidelines for PCF testing [ 40 ]. The study by Morrow et al. [ 41 ] confirmed a significant positive linear correlation between PEF and PCF in children with neuromuscular disorders (NMDs), showing strong consistency. PEF can be used as an alternative test to assess the effectiveness of coughing. We combined PCF and PEF to discuss the effectiveness of respiratory muscle training for cough. According to reports, a technique to boost cough should be added to the treatment if the PCF is less than 270 L/min, which is the minimum required for an effective cough [ 42 ]. Two studies reported PEF or PCF, both parameters that can objectively measure cough capacity [ 43 ]. Emriza et al. [ 25 ] found that most patients with CF had a low effective cough score before training, for which expiratory muscle training was performed. The result showed a significant increase in PCF of 52.42 ± 51.91 L/min in the training group. Zeren et al. [ 26 ] used inspiratory muscle training, with PEF expressed as a percentage of predicted values, and the results showed that inspiratory muscle training did not confer significant improvement in PEF. Children and adolescents with neuromuscular disorders and chronic lung diseases (CF, bronchiectasis, postinfectious bronchiolitis obliterans) were included in Rodriguez et al. [ 44 ]. According to this study, patients' PCF of 16 L/min is improved by IMT + EMT. We think the impact on PCF is greater when expiratory muscle training is used alone.

Notably, among patients with CF, exercise capacity is a major predictor of both mortality risk and deterioration [ 45 , 46 ]. The higher the level of aerobic fitness in people with cystic fibrosis, the lower the risk of death. But only one study in the review reported maximum oxygen uptake (Vo 2max ), it reported a significant improvement in Vo 2max in the inspiratory muscle training group, but not in the control group [ 24 ]. Therefore, in the future, it is necessary to further explore the aerobic fitness ability of patients with CF after RMT, which will be important for determining the optimal respiratory muscle training regimen.

A great number of patients with CF need lifetime care, which entails frequent admissions and a demanding daily treatment schedule. The impact of this heavy treatment load on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is substantial [ 47 , 48 ]. We must not only consider the effectiveness of interventions, but also assess how patients perceive the benefits of their treatment, which should be particularly important for patients with cystic fibrosis exhibiting chronic, long-term characteristics. However, only three of the studies included in the review reported having used an outcome measure assessing health-related quality of life [ 25 , 28 , 29 ]. We believe that this is a significant omission from other studies and severely limits the external validity of the research base. Bieli reported that neither CFQ nor CFCS improved [ 29 ]. In the study of Emirza et al., the physical function of patients and parents in the training group was improved, and the treatment burden of parents was reduced [ 25 ]. They also offered significant evidence regarding the relative value of interventions from the perspective of the patient and parent. In health technology assessments, quality of life scores can be utilized in conjunction with other scientific information to support financing or regulatory decisions for cystic fibrosis treatment.

Limitations

The RMT treatment intervention for CF with children and adolescents has two limitations. First, the data were mainly from small clinical trials and were highly heterogeneous, for example, The ability to detect treatment effects was hampered by the inconsistent methodological quality of the included studies, heterogeneity in the results used in the studies, the units of measurement for some outcomes, and the methods and degrees of determining and reporting participants' clinical status. Furthermore, the trials' follow-up periods were insufficiently short (12 weeks was the longest regimen) and the effects of long-term use were not entirely evident, thus it could be worthwhile to prolong the intervention time to six months or perhaps a year.