Advertisement

“Internet Addiction”: a Conceptual Minefield

- Open access

- Published: 19 September 2017

- Volume 16 , pages 225–232, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Francesca C. Ryding 1 &

- Linda K. Kaye 1

17k Accesses

56 Citations

19 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

With Internet connectivity and technological advancement increasing dramatically in recent years, “Internet addiction” (IA) is emerging as a global concern. However, the use of the term ‘addiction’ has been considered controversial, with debate surfacing as to whether IA merits classification as a psychiatric disorder as its own entity, or whether IA occurs in relation to specific online activities through manifestation of other underlying disorders. Additionally, the changing landscape of Internet mobility and the contextual variations Internet access can hold has further implications towards its conceptualisation and measurement. Without official recognition and agreement on the concept of IA, this can lead to difficulties in efficacy of diagnosis and treatment. This paper therefore provides a critical commentary on the numerous issues of the concept of “Internet addiction”, with implications for the efficacy of its measurement and diagnosticity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Internet Addiction

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

What Is Internet Addiction (IA)?

Traditionally, the term addiction has been associated with psychoactive substances such as alcohol and tobacco; however, behaviours including the use of the Internet have more recently been identified as being addictive (Sim et al. 2012 ). The concept of IA is generally characterised as an impulse disorder by which an individual experiences intense preoccupation with using the Internet, difficulty managing time on the Internet, becoming irritated if disturbed whilst online, and decreased social interaction in the real world (Tikhonov and Bogoslovskii 2015 ). These features were initially proposed by Young ( 1998 ) based on the criteria for pathological gambling (Yellowlees and Marks 2007 ), and have since been adapted for consideration within the DSM-5. This has been well received by many working in the field of addiction (Király et al. 2015 ; Petry et al. 2014 ), and has been suggested to enable a degree of standardisation in the assessment and identification of IA (King and Delfabbro 2014 ). However, there is still debate and controversy surrounding this concept, in which researchers acknowledge much conceptual disparity and the need for further work to fully understand IA and its constituent disorders (Griffiths et al. 2014 ).

Much of the debate relates to the issue that IA is conceptualised as addiction to the Internet as a singular entity, although it incorporates an array of potential activities (Van Rooij and Prause 2014 ). That is, the Internet, in all its formats, whether accessed via PC, console, laptop or mobile device, is fundamentally a portal through which we access activities and services. Internet connectivity thus provides us with ways of accessing the following types of activities; play (e.g. online forms of gaming, gambling), work (accessing online resources, downloading software, emailing, website hosting), socialising (social networking sites, group chats, online dating), entertainment (film databases, porn, music), consumables (groceries, clothes), as well as many other activities and services. In this way, the Internet is a highly multidimensional and diverse environment which affords a multitude of experiences as a product of the specific virtual domain. Thus, it is questionable as to whether there is any degree of consistency in the concept of IA, in light of these diverse and specific affordances which may relate to Internet engagement. Indeed, it has been indicated that there are several distinct types of IA, including online gaming, social media, and online shopping (Kuss et al. 2013 ), and it has been claimed that through engagement in these behaviours, individuals may become addicted to these experiences, as opposed to the medium itself (Widyanto et al. 2011 ). Thus, IA is arguably too generalised as a concept to adequately capture these nuances. That is, an individual who spends excessive time online for shopping is qualitatively different from someone who watches or downloads porn excessively. These represent distinct behaviours which are arguably underpinned by different gratifications. Thus, the functionality of aspects of the Internet is a key consideration for research in this area (Tokunaga 2016 ). This is perhaps best approached from a uses and gratifications perspective (LaRose et al. 2003 ; Larose et al. 2001a ; Wegmann et al. 2015 ), to more fully understand the aetiology of IA (discussed subsequently). This is often best underpinned by the uses and gratifications theory (Larose et al. 2001a , 2003 ), which seeks to explain (media) behaviours by understanding their specific functions and how they gratify certain needs. Indeed, in the context of IA, this may be particularly useful to establish the extent to which certain Internet-based behaviours may be more or less functional in need gratification than others, and the extent to which it is Internet platform itself which is driving usage or indeed the constituent domains which it affords. If the former, then controlling Internet-based usage behaviour more generically is perhaps appropriate, however, a more specified approach may often be required given the diverse needs the online environment can afford users.

IA from a Gratifications Perspective

It is questionable on the extent to which IA is itself the “addiction” or whether its aetiology relates to other pre-existing conditions, which may be gratified through Internet domains (Caplan 2002 ). One particular theory that has been referenced throughout much developing research (King et al. 2012 ; Laier and Brand 2014 ) is the cognitive-behavioural model, proposed by Davis ( 2001 ). This model suggests that maladaptive cognitions precede the behavioural symptoms of IA (Davis 2001 ; Taymur et al. 2016 ). Since much research focuses on the comorbidity between IA and psychopathology (Orsal et al. 2013 ), this is particularly useful in underpinning the concept of IA, and perhaps provides support that IA is a manifestation of underlying disorders, due to its psychopathological aetiology (Taymur et al. 2016 ). Additionally, the cognitive-behavioural model also distinguishes between both specific and generalised pathological Internet use, in comparison to global Internet behaviours that would not otherwise exist outside of the Internet, such as surfing the web (Shaw and Black 2008 ). As such, it would assume those individuals who spend excessive time playing poker online, for example, are perhaps better categorised as problematic gamblers rather than as Internet addicts (Griffiths 1996 ). This has been particularly advantageous in the contribution to defining IA, as earlier literature tended to focus solely on either content-specific IA, or the amount of time spent online, rather than focussing as to why individuals are actually online (Caplan 2002 ). Indeed, this shows promise in resolving some of the aforementioned issues in the specificity of IA, as well as the likelihood of pre-existing conditions underpinning problematic behaviours on the Internet.

Much of the recent literature in the realm of IA has focused upon Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) which has recently been included as an appendix as “a condition for further study” in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013 ). This has driven a wide range of research which has sought to establish the validity of IGD as an independent clinical condition (Kuss et al. 2017 ). Among the wealth of research papers surrounding this phenomenon, there remains large disparity within the academic community. Although some researchers claim there is consensus on IGD as a valid clinical disorder (Petry et al. 2014 ), others do not support this (e.g. Griffiths et al. 2016 ). As such, the academic literature has some way to go before more established claims can be made towards IGD as a valid construct, and indeed how this impacts upon clinical treatment.

One means by which researchers could move forward in this regard is to establish the validity of IGD to a wider range of gaming formats. That is, IGD research has predominantly defined the reference point in studies as “online games” or in some cases, is has been even less specific (Lemmens et al. 2015 ; Rehbein et al. 2015 ; Thomas and Martin 2010 ). Arguably, there are a range of forms of “online” gaming, including social networking site (SNS) games which are Internet-mediated and thus by definition, would appear under the remit of IGD. Indeed, links between SNS and gaming have been previously noted (Kuss and Griffiths 2017 ), although this has not specifically been empirically explored in the context of IGD symptomology. For example, causal form of gaming as is typically the case for SNS gaming have their own affordances in respect of where and how they are played, given these are often played on mobile devices rather than on more traditional PC or console platforms. Further, the demographics of who are most likely to play these games can vary from others forms of gaming which have predominated the IGD literature (Hull et al. 2013 ; Leaver and Wilson 2016 ). Accordingly, these affordances present additional nuances, which the literature has not yet fully accounted for in its exploration of IGD. Clearly, IGD relates to a specific form of Internet behaviour which may be conceptualised within IA, yet is paramount to understand it as a separate entity to ensure the conceptualisation and any associated treatment provision is sufficiently nuanced. Likewise, the same case can be made for many other Internet-based behaviours which may be best being established in respect of their functionality and gratification purposes for users.

IA as a Contextual Phenomenon

There is growing evidence suggesting that context is key towards the processes and cognitions associated with consumption of substances such as alcohol (Monk and Heim 2013 , 2014 ; Monk et al. 2016 ), highlighting some important implications towards understanding IA, as a form of behavioural addiction. That is, the study of IA has rarely been studied in respect of its contextual affordances, even though the combination of Internet connectivity (WiFi) and mobility (smartphones) means that the Internet may be accessed in many ways and in multiple contexts. It has been indicated by Griffiths ( 2000 ) that few studies consider the context of Internet use, despite many users spending a substantial amount of time on the Internet via the use of different platforms, such as mobile devices, as opposed to a computer (Hadlington 2015 ). It has been highlighted by Kawabe et al. ( 2016 ) that smartphone ownership in particular is rapidly increasing, and for some, smartphone devices have become a substitute for the computer (Aljomaa et al. 2016 ). It has also been suggested that the duration of usage on smartphones have been significantly associated with IA (Kawabe et al. 2016 ). This can largely be attributed to the advancement of smartphone technology, which permit them to function as a “one-stop-shop” for a variety of our everyday needs (checking the time, replying to emails, listening to music, interacting with others, playing games), and thus it is understandable that we are spending more of our time in using these devices. This further implicates research in IA, as this has often focussed on users’ Internet engagement through computers as opposed to mobile devices, albeit the numerous Internet subtypes accessible through mobile devices (Sinkkonen et al. 2014 ). One Internet subtype in particular which may facilitate addictive behaviours are social networking sites such as Facebook (Wu et al. 2013 ). Particularly, research has identified a positive relationship between daily usage of smartphones and addictive symptoms towards Facebook (Wu et al. 2013 ). This may also be the case for behaviours such as gaming through SNS which are typically accessed on mobile devices rather than computers. However, of critical interest here, is that addiction to these games has been argued to fall under the classification of IGD, despite being online via Facebook (Ryan et al. 2014 ). This indicates that the platform of Internet access is important in online behaviours, as well as implicating that further distinction between Internet subtypes should be made (particularly within SNS), to establish the different features of these, and how these affordances may be related to excessive usage. This issue is particularly pertinent given the increased interest in “smartphone addiction” (Kwon et al. 2013 ) in which the name assumes we are simply studying addiction to our smartphones themselves, not necessarily the functions they are affording to us. Research such as this is assuming the “problem” is the interaction with the technology (e.g. specific device) itself, when this is most likely not the case. Indeed, recent evidence highlights that different uses/functions of smartphones may be more likely to prompt users to feel more “attached” to the device than others, and that usage is often framed by one’s current context (Fullwood et al. 2017 ).

In addition to being able to access the Internet through multiple platforms, we are often reliant on the Internet for many everyday tasks, which poses a further issue in conceptualising what is “problematic” compared to “required” usage. The increased exposure to the Internet in both work and education make it difficult to avoid usage in such environments (Kiliҫer and Ҫoklar 2015 ; Uçak 2007 ), and it could be argued that the amount of time spent on the Internet for such contexts cannot be reflected as an addiction (LaRose et al. 2003 ). This is pertinent in light of much research, which tends to rely on metrics such as time spent online (e.g. average hours per week) as a variable in research paradigms. Particularly, this tends to be used to correlate against other psychological factors, such as depression or well-being, to indicate how “internet use” may be a problematic predictor of these outcomes (e.g. Sanders et al. 2000 ). In light of the aforementioned issues, this does not offer any degree of specificity in how time spent online is theoretically related to the outcomes variables of interest (Kardefelt-Winther 2014 ). Other studies have approached this with greater nuance by considering specific activities, such as number of emails sent and received in a given time period (Ford and Ford 2009 ; LaRose et al. 2001b ), or studied Internet use for a variety of different purposes, such as for health purposes and communication (Bessière et al. 2010 ). Further, other researchers have highlighted the distinction between behaviours such as smartphone “usage” versus “checking” (Andrews et al. 2015 ), whereby the latter may represent a more compulsive and less consciously driven and potentially more addictive form of behaviour than actual “usage”. These more nuanced approaches provide a more useful and theoretically insightful means of establishing how time spent online may be psychologically relevant as a concept. This suggests that future research which theorises on the impacts of “time spent online” (or “screen-time use”) should provide distinction between usage for work/education and leisure, and the gratification this engagement affords, to obtain greater nuance beyond the typical flawed metrics such as general time spent online.

A further compliment to the existing IA literature would be greater use of behavioural measures which garner users’ actual Internet-based behaviours. This is particularly relevant when considering that almost all existing research on smartphone addiction or problematic use, for example has been based on users’ self-reported usage, with no psychometric measure being validated against behavioural metrics. Worryingly, it has been noted that smartphone users grossly underestimate the amount of times they check their smartphone on a daily basis, with digital traces of their smartphone behaviours illuminating largely disparate findings (Andrews et al. 2015 ). Clearly, there is much opportunity to establish forms of Internet usage by capitalising on behavioural metrics and digital traces rather than relying on self-report which may not always be entirely accurate.

The concept of IA is more complex than it often theorised. Although there have been multiple attempts to define the characteristics of IA, there a numerous factors which require greater clarity in the theoretical underpinnings of this concept. Specifically, IA is often considered from the perspective that the Internet itself (and indeed the technology through which we access it) is harmful, with little specificity in how this functions in different ways for individual users, as well as the varying affordances which can be gained through it. Unfortunately, this aligns somewhat with typical societal conceptions of “technology is harmful” perspective, rather than considering the technology itself is simply a portal through which a psychological need is being served. This perspective is not a new phenomenon. Most new media has been subject to such moral panic and thus this serves a historical tradition within societal conception of new media. Indeed, this has been particularly relevant to violent videogames which scholars have discussed in respect of this issue (Ferguson 2008 ). Whilst many scholars recognise this notion through the application of a user and gratifications perspective, stereotypical conceptions of “technology is harmful” still remain. This raises the question about how we as psychologists can enable a cultural shift in these conceptions, to provide a more critical perspective on such issues. The pertinence of this surrounds two key issues; firstly that moving beyond a “technology is harmful” perspective, particularly for concerns over “Internet addiction” as one example, can enable a more critical insight into the antecedents of problematic behaviour to aid treatment, rather than simply revoking access from the Internet for such individuals. Arguably, this latter strategy would not always address the route of the issue and raises implications about the extent to which recidivism would occur upon reinstating Internet access. Secondly, on a more general level, diverging from an “anti-technology” perspective can enable researchers to draw out the nuances of specific Internet environments and their psychological impacts rather than battling with more blanket assumptions that “technology” (as a unitary concept) is presenting all individuals with the same issues and affordances, regardless of the specific virtual platform or context. In this way, we may be presented with more plentiful opportunities to more critically explore individuals and their interactions across many Internet-mediated domains and contexts.

Aljomaa, S. S., Al Qudah, M. F., Albursan, I. S., Bakhiet, S. F., & Abduljabbar, A. S. (2016). Smartphone addiction among university students in the light of some variables. Computers in Human Behavior, 61 , 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.041 .

Article Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Book Google Scholar

Andrews, S., Ellis, D. A., Shaw, H., & Piwek, L. (2015). Beyond self-report: tools to compare estimated and real-world smartphone use. PloS One, 10 , e0139004.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bessière, K., Pressman, S., Kiesler, S., & Kraut, R. (2010). Effects of Internet use on health and depression: a longitudinal study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12 (1), e6. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1149 .

Caplan, S. E. (2002). Problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being: development of a theory-based cognitive–behavioral measurement instrument. Computers in Human Behavior, 18 (5), 553–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0747-5632(02)00004-3 .

Davis, R. A. (2001). A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 17 (2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0747-5632(00)00041-8 .

Ferguson, C. J. (2008). The school shooting/violent video game link: casual relationship or moral panic? Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 5 , 25–37.

Ford, G. S., & Ford, S. G. (2009). Internet use and depression among the elderly . Phoenix Center Policy Paper Series. Retrieved April 26, 2016, from http://www.phoenix-center.org/pcpp/PCPP38Final.pdf .

Fullwood, C., Quinn, S., Kaye, L. K., & Redding, C. (2017). My Virtual friend: a qualitative analysis of the attitudes and experiences of Smartphone users: implications for Smartphone attachment. Computers in Human Behavior, 75 , 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.029 .

Griffiths, M. D. (1996). Gambling on the Internet: a brief note. Journal of Gambling Studies, 12 (4), 471–473.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Griffiths, M. (2000). Internet addiction - time to be taken seriously? Addiction Research & Theory, 8 (5), 413–418. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066350009005587 .

Griffiths, M. D., King, D. L., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). DSM-5 Internet Gaming Disorder needs a unified approach to assessment. Neuropsychiatry, 4 (1), 1–4.

Griffiths, M. D., Van Rooij, A. J., Kardefelt-Winther, D., et al. (2016). Working towards an international consensus on criteria for assessing internet gaming disorder: a critical commentary on Petry et al. (2014). Addiction, 111 , 167–175.

Hadlington, L. J. (2015). Cognitive failures in daily life: exploring the link with Internet addiction and problematic mobile phone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 51 , 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.036 .

Hull, D. C., Williams, G. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2013). Video game characteristics, happiness and flow as predictors of addiction among video game players: a pilot study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2 (3), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.2.2013.005 .

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31 , 351–354.

Kawabe, K., Horiuchi, F., Ochi, M., Oka, Y., & Ueno, S. (2016). Internet addiction: prevalence and relation with mental states in adolescents. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 70 (9), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12402 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kiliҫer, K., & Ҫoklar, A. N. (2015). Examining human value development of children with different habits of Internet usage. Hacettepe University of Education, 30 (1), 163–177.

Google Scholar

King, D. L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2014). The cognitive psychology of Internet gaming disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 34 (4), 298–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.03.006 .

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Griffiths, M. D., & Gradisar, M. (2012). Cognitive-behavioral approaches to outpatient treatment of Internet addiction in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68 (11), 1185–1195. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21918 .

Király, O., Griffiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2015). Internet gaming disorder and the DSM-5: conceptualization, debates, and controversies. Current Addiction Reports, 2 (3), 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0066-7 .

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social networking networking sites and addiction: ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14 , 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030311 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kuss, D. J., van Rooij, A. J., Shorter, G. W., Griffiths, M. D., & van de Mheen, D. (2013). Internet addiction in adolescents: prevalence and risk factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 (5), 1987–1996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.002 .

Kuss, D. J., Grittihs, M. D., & Pontes, H. M. (2017). DSM-5 diagnosis of Internet Gaming Disorder: some ways forward in overcoming issues and concerns in the gaming studies field. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.032 .

Kwon, M., Lee, J., Won, W., Park, J., Min, J., Hahn, C., Gu, X., Choi, J., & Kim, D. (2013). Development and validation of a smartphone addiction scale. PloS One, 8 (2), e56936. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056936 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Laier, C., & Brand, M. (2014). Empirical evidence and theoretical considerations on factors contributing to cybersex addiction from a cognitive-behavioral view. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 21 (4), 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2014.970722 .

Larose, R., Mastro, D., & Eastin, M. S. (2001a). Understanding Internet usage: a social-cognitive approach to uses and gratifications. Social Science Computer Review, 19 (4), 395–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/089443930101900401 .

LaRose, R., Eastin, M. S., & Gregg, J. (2001b). Reformulating the Internet paradox: social cognitive explanations of Internet use and depression. Journal of Online Behavior, 1 (2). Retrieved Setpember 12, 2017 from http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2002-14047-001 .

LaRose, R., Lin, C. A., & Eastin, M. S. (2003). Unregulated Internet usage: Addiction, habit, or deficient self-regulation? Media Psychology, 5 (3), 225–253. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532785xmep0503_01 .

Leaver, T., & Wilson, M. (2016). Social networks, casual games and mobile devices: the shifting contexts of gamers and gaming . London: Bloomsbury Publishing Inc..

Lemmens, J. S., Valkenburg, P. M., & Gentile, D. A. (2015). The internet gaming disorder scale. Psychological Assessment, 27 (2), 567–582.

Monk, R. L., & Heim, D. (2013). Environmental context effects on alcohol-related outcome expectancies, efficacy and norms: a field study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27 , 814–818.

Monk, R. L., & Heim, D. (2014). A real-time examination of context effects on alcohol cognitions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38 , 2452–2459.

Monk, R. L., Pennington, C. R., Campbell, C., Price, A., & Heim, D. (2016). Implicit alcohol-related expectancies and the effect of context. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77 , 819–827.

Orsal, O., Unsal, A., & Ozalp, S. S. (2013). Evaluation of Internet addiction and depression among university students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 82 , 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.291 .

Petry, N. M., Rehbein, F., Gentile, D. A., Lemmens, J. S., Rumpf, H., Mӧßle, T., et al. (2014). An international consensus for assessing Internet Gaming Disorder using the new DSM-5 approach. Addiction, 109 (9), 1399–1406. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12457 .

Rehbein, F., Kliem, S., Baier, D., Mossle, T., & Petry, N. M. (2015). Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in German adolescents: diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM-5 criteria in a state-wide representative sample. Addiction, 110 (5), 842–851.

Ryan, T., Chester, A., Reece, J., & Xenos, S. (2014). The uses and abuses of Facebook: a review of Facebook addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3 (3), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.3.2014.016 .

Sanders, C. E., Field, T. M., Diego, M., & Kaplan, M. (2000). The relationship between Internet use to depression and social isolation among adolescents. Adolescence, 35 (138), 237–242.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Shaw, M., & Black, D. W. (2008). Internet addiction. CNS Drugs, 22 (5), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200822050-00001 .

Sim, T., Gentile, D. A., Bricolo, F., Serpelloni, G., & Gulamoydeen, F. (2012). A conceptual review of research on the pathological use of computers, video games, and the Internet. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10 (5), 748–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-011-9369-7 .

Sinkkonen, H.-M., Puhakka, H., & Meriläinen, M. (2014). Internet use and addiction among Finnish adolescents (15–19 years). Journal of Adolescence, 37 (2), 123–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.11.008 .

Taymur, I., Budak, E., Demirci, H., Akdağ, H. A., Güngör, B. B., & Özdel, K. (2016). A study of the relationship between internet addiction, psychopathology and dysfunctional beliefs. Computers in Human Behavior, 61 , 532–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.043 .

Thomas, N. J., & Martin, F. H. (2010). Video-arcade game, computer game and Internet activities of Australian students: participation participation habits and prevalence of addiction. Australian Journal of Psychology, 62 (2), 59–66.

Tikhonov, M. N., & Bogoslovskii, M. M. (2015). Internet addiction factors. Automatic Documentation and Mathematical Linguistics, 49 (3), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.3103/s0005105515030073 .

Tokunaga, R. S. (2016). An examination of functional difficulties from Internet use: Media habit and displacement theory explanations. Human Communication Research, 42 (3), 339–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12081 .

Uçak, N. Ö. (2007). Internet use habits of students of the department of information management, Hacettepe University, Ankara. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 33 (6), 697–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2007.09.004 .

Van Rooij, A., & Prause, N. (2014). A critical review of “Internet addiction” criteria with suggestions for the future. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3 (4), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.3.2014.4.1 .

Wegmann, E., Stodt, B., & Brand, M. (2015). Addictive use of social networking sites can be explained by the interaction of Internet use expectancies, Internet literacy, and psychopathological symptoms. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4 (3), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.021 .

Widyanto, L., Griffiths, M. D., & Brunsden, V. (2011). A psychometric comparison of the Internet Addiction Test, the Internet-Related Problem Scale, and self-diagnosis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14 (3), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0151 .

Wu, A. M. S., Cheung, V. I., Ku, L., & Hung, E. P. W. (2013). Psychological risk factors of addiction to social networking sites among Chinese smartphone users. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2 (3), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.2.2013.006 .

Yellowlees, P. M., & Marks, S. (2007). Problematic Internet use or Internet addiction? Computers in Human Behavior, 23 (3), 1447–1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.05.004 .

Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 1 (3), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Edge Hill University, St Helens Road, Ormskirk, Lancashire, L39 4QP, UK

Francesca C. Ryding & Linda K. Kaye

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Linda K. Kaye .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ryding, F.C., Kaye, L.K. “Internet Addiction”: a Conceptual Minefield. Int J Ment Health Addiction 16 , 225–232 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9811-6

Download citation

Published : 19 September 2017

Issue Date : February 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9811-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Internet addiction

- Gratifications

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Predictive effect of internet addiction and academic values on satisfaction with academic performance among high school students in mainland china.

- Department of Applied Social Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Academic performance occupies an important role in adolescent development. It reflects adolescents’ cognitive ability and also shapes their academic and career paths. Students who are satisfied with their school performance tend to show higher self-esteem, confidence, and motivation. Previous research has suggested that students’ problem behaviors, such as Internet Addiction (IA), and academic values, including intrinsic and utility values, could predict satisfaction with academic performance. However, the influence of IA and academic values has not been thoroughly explored in Chinese contexts where the pressure for academic success is heavy. This study examined the relationships between IA, academic values (intrinsic and utility value), and satisfaction with academic performance using two waves of data collected from secondary school students in four cities in mainland China. The matched sample included a total of 2,648 Grade 7 or 8 students (57.1% were boys with a mean age of 13.1 years at Wave 1). Participants completed the same questionnaire containing validated measures at both waves with a 1-year interval. In line with the hypotheses, multiple regression analyses showed that Wave 1 IA was a significant negative predictor of Wave 2 intrinsic value, utility value, and satisfaction with academic performance and their changes. Results of mediation analyses revealed that only intrinsic value, but not utility value, positively predicted satisfaction with academic performance. Structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses also showed similar findings. Two observations are concluded from the present findings: IA impaired students’ intrinsic value, utility value, and perceived satisfaction with academic performance; two aspects of academic values demonstrated different influences on satisfaction with academic performance. These findings provide implications for the promotion of academic satisfaction experienced by students and the prevention of negative effects of IA.

Introduction

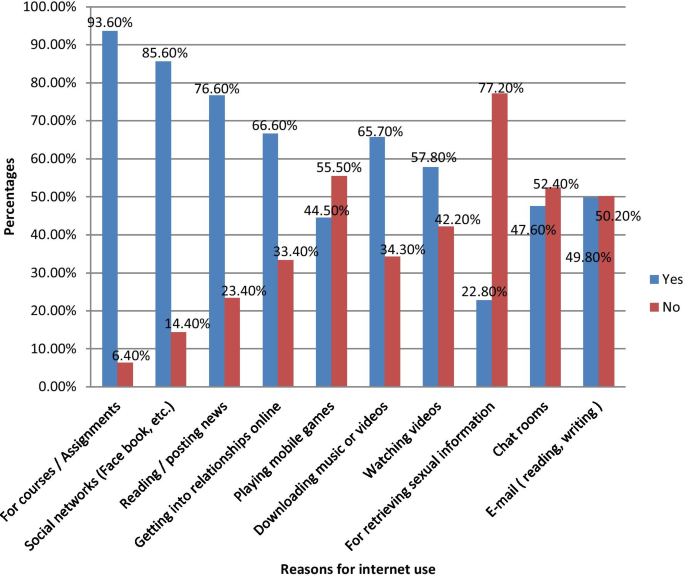

The Internet has significantly changed people’s lives nowadays. Despite the profound benefits of the Internet, the public is aware of the negative influence of its overuse of misuse on health and well-being. One common problem is Internet addiction (IA), which refers to one’s inability to control Internet use that consequently causes social, psychological, academic, and work difficulties in life ( Chou and Hsiao, 2000 ). IA has drawn growing concerns of the public and professionals worldwide.

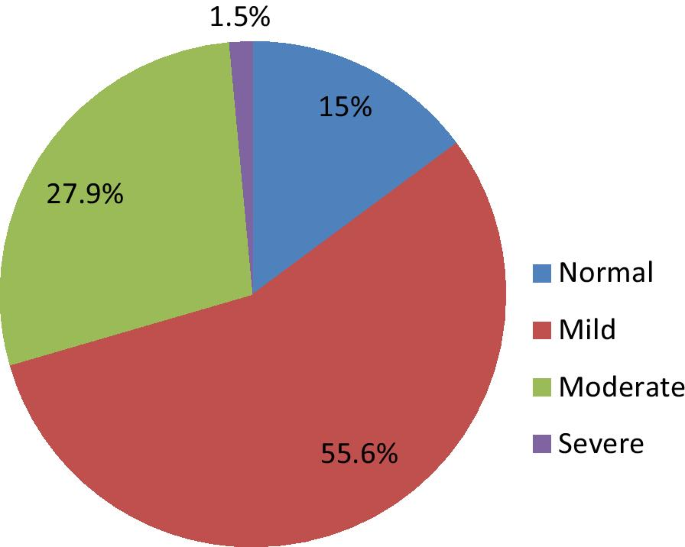

Among different age groups, adolescents are considered more vulnerable to IA as their cognitive ability, self-control, and coping strategies are not fully developed ( Long et al., 2018 ). Many studies have revealed that adolescents have a higher tendency to develop addictive behaviors such as playing online games or using social media in comparison to adults ( Long et al., 2018 ). As the Internet penetration rate has dramatically increased nowadays, more than 80% of the adolescent population in the United Kingdom, United States, and Asia can access the Internet ( Cerniglia et al., 2017 ). According to a national report, around 940 million Chinese people were Internet users, and among them were 172 million children and adolescents ( China Internet Network Information Center, 2020 ). Research has revealed a relatively high prevalence of IA among Chinese adolescents. Shek et al. (2008) conducted research with 6,121 Chinese primary and high school students in Hong Kong, revealing that around 20% of the respondents met the criteria for IA based on two assessment measures. The study of Tan et al. (2016) involving 1,772 high school students in southern China also showed that around 17.2% of participants demonstrating problematic Internet use.

Many studies have documented the negative impact of IA on different aspects of adolescent development, such as sleeping quality ( Tan et al., 2016 ), mental health ( Ko et al., 2012 ), subjective well-being ( Allen and Anderson, 2018 ), social development ( Cerniglia et al., 2017 ), emotional development ( Truzoli et al., 2020 ), and interpersonal relationship ( Zeng et al., 2021 ). For adolescents, IA is particularly associated with low levels of school performance. Empirical evidence showed that students with IA experience more academic failure than their counterparts ( Nemati and Matlabi, 2017 ). For example, students’ online gambling habits were positively related to low levels of school achievements and less prosocial behaviors ( Floros et al., 2015 ). Online pornography watching also impaired adolescents’ academic performance as it reduces their interest, concentration, and involvement in academic activities ( Beyens et al., 2015 ). Similar results were found among Chinese adolescents. For example, a longitudinal study examined the relationship between Internet behavior and students’ academic development based on a sample of 9,949 Chinese students revealed that IA could lead to lower academic achievement, dropout, and absenteeism ( Anthony et al., 2021 ). Another study evaluating IA and negative emotions also reported that IA negatively influenced academic problems by undermining students’ mental and psychological health ( Bu et al., 2021 ). The study of Bai et al. (2020) based on 1,794 adolescents from low-income families in China revealed that IA was linked to depression and detrimental to students’ academic performance.

In Chinese schools, students are evaluated publicly by peers and teachers in terms of whether their behavioral and academic performance reaches school standards, which largely influences students’ psychological health and adjustment ( Chen et al., 2012 ). Undoubtedly, academic performance is considered the most important standard in Chinese school context. Researchers have adopted different approaches to assess academic performance. Primarily, test scores are considered an objective indicator of academic performance and have been often used in previous studies. Although the use of test scores is helpful to suggest education improvement and school accountability, researchers have questioned whether test scores reflect the stable status of individual students’ overall development ( Goldhaber and Özek, 2019 ). An alternative is to use subjective indicators, such as perceived performance level, which reflects one’s overall subjective evaluation of normative performance level compared to peers ( Saw et al., 2016 ). Researchers have pointed out the importance of subjective perceptions of one’s academic performance for its close association with students’ psychological adjustment ( Haraldsen et al., 2020 ). Researchers also argued that satisfaction with perceived academic performance as an element of school adjustment provides a better indication of one’s appraisal of academic achievement in schools ( Shek, 2002 ). Research has shown that dissatisfaction with one’s academic performance constitutes developmental problems for adolescents, particularly when the failure occurs repetitively ( Enns et al., 2001 ; Lee et al., 2016 ). As the present study was interested in the roles of perceived academic values and motivation, we used satisfaction with academic performance as the indicator.

Scientific studies have been conducted to unravel the mechanisms of the negative impacts of IA on academic performance among adolescents. Earlier research has focused on the distraction and divergence behaviors in learning among students with IA, which often directly lead to a decline in school performance. Besides, anxiety and depression have been found to mediate the adverse effect of IA on academic performance ( Ko et al., 2012 ; Bai et al., 2020 ; Bu et al., 2021 ). Recent evidence suggests that IA may also interrupt students’ psychological learning process and create problems in academic values and motivation ( Reed and Reay, 2015 ; Truzoli et al., 2020 ). For example, problematic Internet use was found to exert a negative effect on academic motivation, learning productivity, and psychosocial status, which have negative effects on academic performance ( Truzoli et al., 2020 ).

Academic motivation includes intrinsic value and utility value ( Eccles, 1983 ; Neel and Fuligni, 2013 ). Intrinsic value involves a sense of satisfaction rooted in the study or learning procedure itself, while utility value refers to students’ sense of the instrumental value of the school courses (such as getting higher grades or material rewards) rather than finding the courses interesting. Ryan and Deci (2000) also categorized motivation into intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation refers to an individuals’ aspiration for doing something from the inner heart, while extrinsic motivation defines the concept of getting rewards from outside to stimulate someone to behave ( Benabou and Tirole, 2003 ).

Previous studies have found that IA may impair intrinsic value, as studying is often not as attractive as surfing the Internet ( Hanus and Fox, 2015 ; Reed and Reay, 2015 ). The various attractive and interesting sensory stimulations derived from the Internet could undermine students’ learning interest, self-control, and self-efficacy in learning. Wang et al. (2021) argued that problematic use of short-form video applications was associated with a sole focus on immediate hedonic rewards and a lack of understanding of future harmful consequences. The research of Anthony et al. (2021) found a close relationship between IA and a lack of interest in school learning. A study conducted with Chinese students also revealed the mediating role of intrinsic motivation in the positive relationship between social media use and academic performance ( Malik et al., 2020 ). Previous studies have mainly focused on the negative influence of IA and intrinsic value but paid less attention to the relationships between IA and utility value. Theoretically speaking, IA could also undermine utility value or extrinsic motivation as the intensive reinforcement and reward schedules in Internet activities (e.g., online games) provide instant extrinsic rewards to adolescents ( Truzoli et al., 2020 ), while students may not necessarily receive instant extrinsic rewards (e.g., high grades or praise) even if they study hard.

Although IA has been commonly considered a risk factor for academic values and performance, how the two types of academic values are associated with performance are less conclusive. Theoretically speaking, intrinsic value promotes academic performance through positive and active engagement in learning with enjoyment, autonomy, deep learning, task arrangement, and time spending in learning ( Vansteenkiste et al., 2005 ; Froiland and Oros, 2014 ; Liu et al., 2020 ). Intrinsic value is considered to have a relatively long-term effect on academic performance because it reinforces students’ self-concepts and values, which are vital for students to maintain healthy psychological status and deal with academic failures ( Cheo, 2017 ). On the contrary, utility value is constrained by the existence of external rewards and thus believed to have an instant but short-term positive effect on academic performance. In other words, once external rewards are terminated, utility value may become ineffective in stimulating adolescents’ continuous efforts into their study.

However, empirical evidence supporting the distinctive effects of the two types of values has been equivocal. For example, the study of Baker (2004) on university students found no significant relationships between intrinsic or extrinsic motivation and academic achievement. Some studies revealed that both intrinsic and utility value were positively linked to school performance ( Afzal et al., 2010 ). Some other studies revealed differential effects of intrinsic and utility value on academic outcomes ( Moneta and Siu, 2002 ). For example, a longitudinal study conducted with 13,799 Chinese high school students revealed the different effects of intrinsic and utility value on academic performance. Students with high levels of intrinsic value were more attentive, focused on learning interests, arranged flexible learning strategies, and spent more time learning to improve their academic performance ( Liu et al., 2020 ). It was argued that utility value might undermine the academic performance of students with high intrinsic value because utility value made students feel of being controlled, which damaged ones’ intrinsic values ( Wang and Guthrie, 2004 ; Liu et al., 2020 ). Similarly, Kuvaas et al. (2017) found that intrinsic value was positively associated with better performance, while extrinsic motivation showed a modest negative effect on performance. These inconclusive findings call for further exploration on how academic values might be differently related to adolescent development.

This study aimed to fill some research gaps. First, this study explored the effects of IA on perceived satisfaction of academic performance and the mediating roles of both intrinsic and utility values. This helps reveal the underlying mechanism of the influence of IA on academic performance and clarify the function of two types of academic values, which would fill the above-mentioned theoretical gaps. Second, most existing studies on adolescent IA and academic outcomes have been conducted with Western samples, hence calling for devoting more efforts to these issues in non-Western societies, particularly in Chinese contexts ( Shek et al., 2008 ; Shek and Yu, 2016 ). As academic excellence is highly emphasized in Chinese societies, academic motivation may be perceived differently. In fact, both intrinsic and utility values are emphasized in traditional Chinese culture. Regarding intrinsic value, Confucian stated that “wasn’t it a pleasure to learn and practice often?” (“xue er shi xi zhi, bu. yi yue hu?”) in the Analects of Confucius, highlighting the satisfaction of learning, practical application, and self-improvement ( Waley, 2005 ). As to utility value, the Chinese saying, “one who excels in the study can follow an official career” (“xue er you ze shi”), emphasizes the benefits of academic excellence in future career development. In contemporary Chines societies, “an official career” may no longer be the ultimate goal of studying. However, the value of education still receives great recognition among the public despite the development of ideology and philosophy in China ( Wang and Ross, 2010 ). At the national level, China’s Education Modernization 2035 plan sets the direction for developing the education sector to strengthen its overall capacity and international influence and makes China a powerhouse of education, human resources, and talents. At the family and individual levels, parents and students believe that “knowledge changes fate” and thus highly emphasize academic success ( Xiang, 2018 ). Third, as most studies have not collected longitudinal data, it is difficult to establish the causal relationships between IA and academic performance. In particular, although longitudinal studies have examined the antecedents of IA (e.g., Yu and Shek, 2013 ), limited research has examined the longitudinal prediction of IA on adolescent developmental outcomes in Chinese adolescents. This research aims to understand the relationship between IA and academic performance and examine the mediating role of academic motivation (intrinsic and utility values) in this relationship using two waves of data.

Research Hypotheses

Based on the literature, we proposed the following hypotheses for each research question.

Research Question 1 (RQ1)

What are the concurrent and longitudinal relationships between IA and academic motivation? Based on the previous findings ( Truzoli et al., 2020 ), we proposed that IA would be negatively associated with intrinsic value concurrently (Hypothesis 1a) and longitudinally (Hypothesis 1b). Besides, with reference to the existing literature ( Ryan and Deci, 2000 ; Truzoli et al., 2020 ), we expected negative concurrent and longitudinal relationships between IA and utility value (Hypotheses 1c,d, respectively).

Research Question 2 (RQ2)

What are the concurrent and longitudinal relationships between IA and satisfaction with academic performance? In line with studies conducted with Chinese students ( Anthony et al., 2021 ), we proposed that IA would be negatively related to satisfaction with academic performance concurrently (Hypothesis 2a) and longitudinally (Hypothesis 2b).

Research Question 3 (RQ3)

What are the concurrent and longitudinal relationships between academic motivation and satisfaction with academic performance? In line with previous research ( Anthony et al., 2021 ), we proposed that intrinsic value would be positively linked to satisfaction with academic performance concurrently (Hypothesis 3a) and longitudinally (Hypothesis 3b). Similarly, utility value would also show positive associations with satisfaction with academic performance concurrently (Hypothesis 3c) and over time (Hypothesis 3d).

Research Question 4 (RQ4)

Does academic motivation mediate the relationship between IA and satisfaction with academic performance? According to previous studies suggesting the mediating role of academic motivation ( Malik et al., 2020 ), we hypothesized that intrinsic value and utility value would mediate the impact of IA on satisfaction with academic performance (Hypotheses 4a,b, respectively).

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedure.

The data of this study were derived from a project examining adolescent adjustment and development in mainland China. The participants were recruited from four junior high schools in three provinces. Two waves of data were collected at the beginning of the school year of 2016/2017 (Wave 1) and 1 year later (Wave 2). A survey questionnaire was administered to students during school hours. Students were informed of the research aims, data collection, and the principles that the data collected will be anonymous, confidential, and only used for academic purposes. We obtained written consent from students, their parents, teachers, and school heads before data collection. This study has been reviewed and granted ethical approval by the authors’ university.

In total, 3,010 students completed the questionnaire at Wave 1. Among them, 1,362 were in Grade 7, and 1,648 were in Grade 8. The data at Wave 2 were collected from 2,648 students, including 1,305 Grade 8 students and 1,343 Grade 9 students. The matched sample consisted of 2,648 students (Boys = 1,513; Girls = 1,109) with a mean age of 13.12 years at Wave 1. The attrition rates were 4.2 and 18.5% for Grade 7 and Grade 8 students, respectively, which were more favorable compared with studies reported in longitudinal studies with adolescents ( Epstein and Botvin, 2000 ). Results of attrition analysis revealed non-significant differences between students in the matched sample ( n = 2,648) and the dropouts ( N = 362) in terms of age, IA, intrinsic and utility values, and satisfaction with academic performance in both grades.

Internet Addiction

The Chinese version of the Internet Addiction Scale developed by Young (1998) was adopted to evaluate participants’ IA symptoms. This scale has been used and validated in previous studies and showed good psychometric properties ( Shek et al., 2008 ; Yu and Shek, 2013 ; Chi et al., 2020 ). It includes 10 items assessing different IA symptoms, such as “Have you lied to family members, teachers, social workers, or others to conceal the extent of involvement with the Internet?” Participants indicated whether they exhibited each of the symptoms in the past 12 months on a dichotomous scale (i.e., yes/no). The total score equals the counts of “yes” answers to 10 questions. The values of Cronbach’s α of IA were 0.77 at Wave 1 and 0.80 at Wave 2.

Academic Values

Students’ academic values were measured via two aspects, including intrinsic value and utility value ( Eccles, 1983 ; Neel and Fuligni, 2013 ). This scale has been validated in the Chinese context ( Guo et al., 2017 ). Intrinsic value depicts how students perceive schoolwork as interesting and how much they like schoolwork in general. It includes two items: “In general, I find working on schoolwork is…” (1 = “very boring” and 5 = “very interesting”) and “How much do you like working on schoolwork?” (1 = “a little” and 5 = “a lot”). On the other hand, the utility value describes the perceived usefulness of schoolwork through three items: “Right now, how useful do you find things you learn in school to be in your everyday life,” “In the future, how useful do you think the things you have learned in school will be in your everyday life?” and “How useful do you think the things you have learned in school will be for what you want to be after you graduate” on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “not useful at all” and 5 = “very useful”). The Cronbach’s α estimates for the two scales ranged between 0.87 and 0.91 at the two waves, suggesting good internal consistency of the scales in this study.

Satisfaction With Academic Performance

Satisfaction with academic performance was measured by a single item, “I am satisfied with my academic performance as compared to my classmates,” on a six-point reporting scale (“1 = strongly disagree”; “6 = strongly agree”). This item was developed by authors based on literature ( Education and Manpower Bureau, 2003 ) and has been used in previous studies ( Shek, 2002 ).

Data Analysis

We first conducted descriptive analyses. Table 1 summarizes the means, SDs, and correlations among variables. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine the concurrent and longitudinal relationships between research variables (RQ1, RQ2, and RQ3). This approach has been commonly adopted in the field ( Zhou et al., 2020 ; Dou and Shek, 2021 ). Particularly, we examined the longitudinal effects of IA at Wave 1 on academic outcomes at Wave 2 with the corresponding outcomes at Wave 1 controlled. By controlling the influence of the initial levels of academic outcomes, this method suggests the effect of the predictor variables on the dependent variables over time.

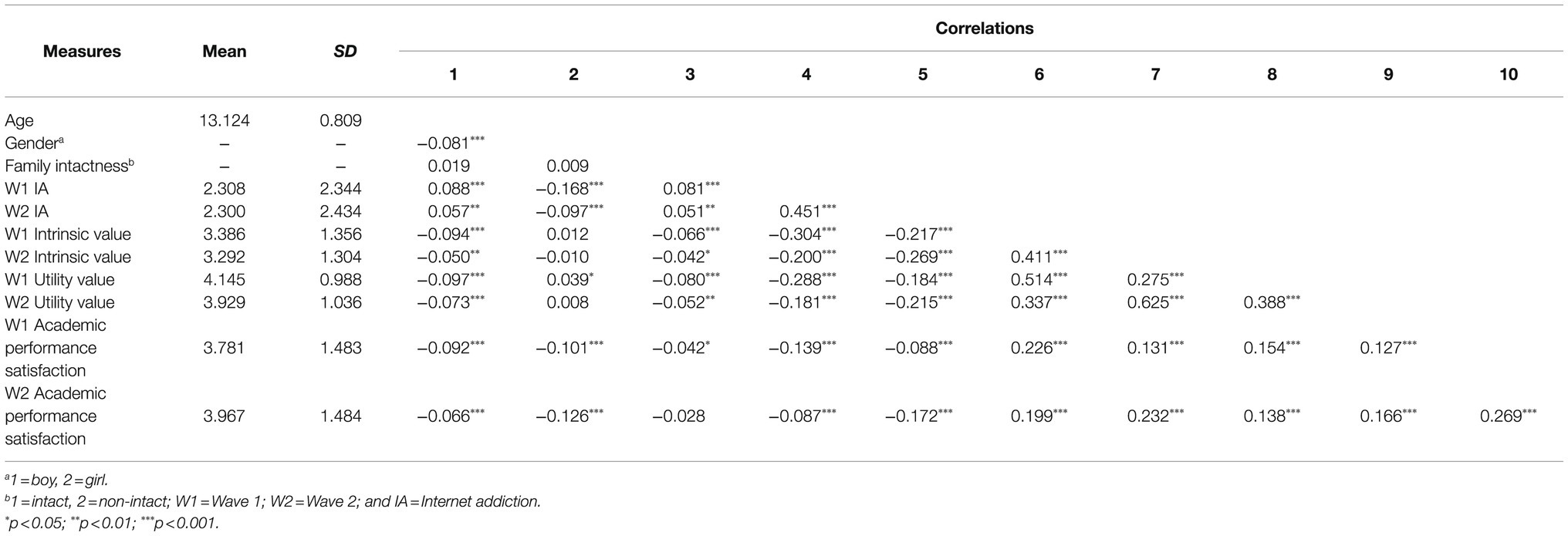

Table 1 . Descriptive and correlational analyses.

For RQ4, we first analyzed the mediational role of intrinsic and utility value through a series of regression models using PROCESS macro in SPSS ( Hayes, 2017 ). We calculated bias-corrected (BC) bootstrap 95% CIs using 2,000 re-samplings in the mediation analyses ( Hayes, 2017 ). We first examined the mediating effects of intrinsic and utility values in two models separately, and then simultaneously added them to one model. This conservative method is helpful to explore the relationships between research variables in line with research questions and also suggest potential interactions. Besides, we used Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to test the complete hypothesized model via Lavaan package in R software ( Rosseel, 2012 ). SEM models can accommodate latent variables, multiple predictors, and outcomes, which allow a comprehensive analysis of the relationships between research variables. Multiple indices were used to indicate model goodness of fit, including Comparative Fit Index (“CFI”), Tucker-Lewis Index (“TLI”), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (“RMSEA”), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (“SRMR”). Based on Hu and Bentler (1999) and Kline (2015) , the cutoff criteria should be above 0.90 for CFI and TFI values, and lower than 0.08 for RMSEA and SRMR values.

Descriptive Results and Correlations

Table 1 shows the means, SDs, and correlations for IA, intrinsic value, utility value, and satisfaction with school performance over the two time points. The correlations between the research variables were significant and in line with the hypotheses. IA was negatively associated with intrinsic and utility value concurrently and longitudinally ( r ranged between −0.20 and −0.30, p s < 0.001), and was negatively correlated with satisfaction with academic performance at each wave ( r s ranged between −0.09 and −0.17, p s < 0.001). Both intrinsic and utility values were positively correlated with satisfaction with academic performance at two waves ( r s ranged between 0.127 and 0.232, p s < 0.001).

Predictive Effects of IA on Academic Values

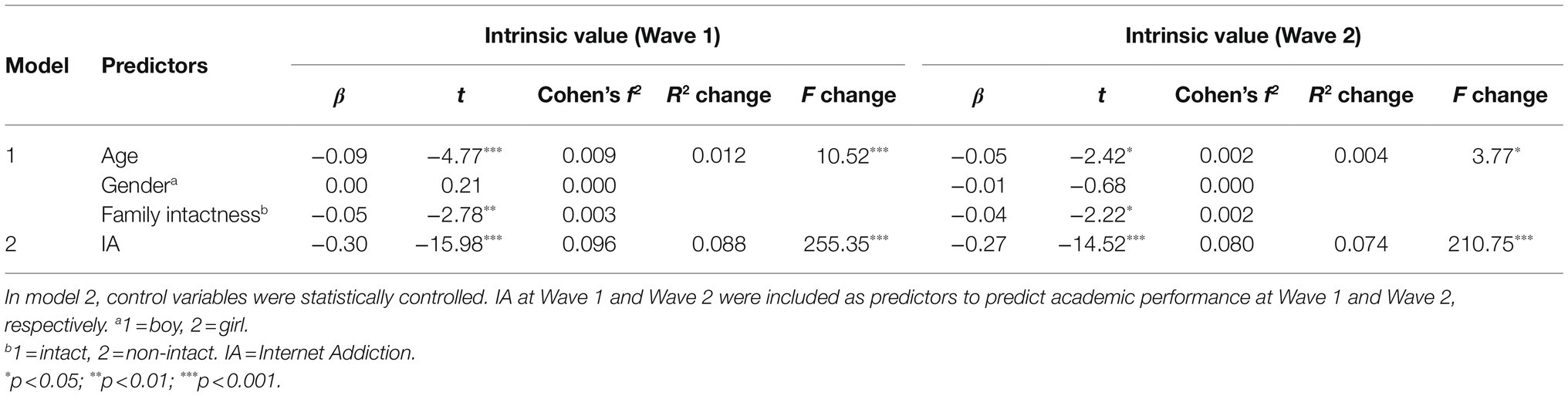

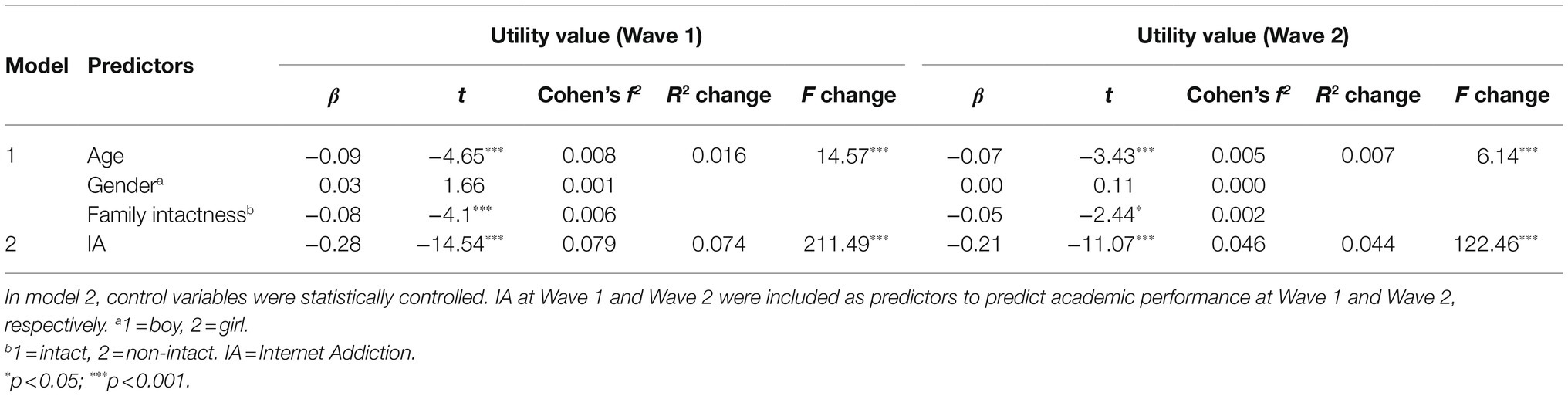

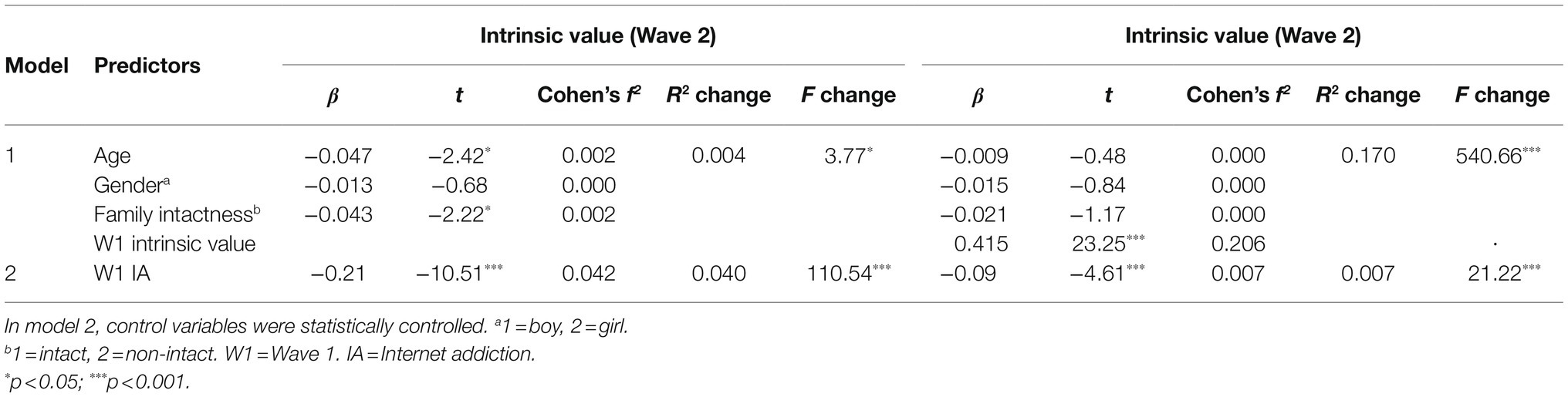

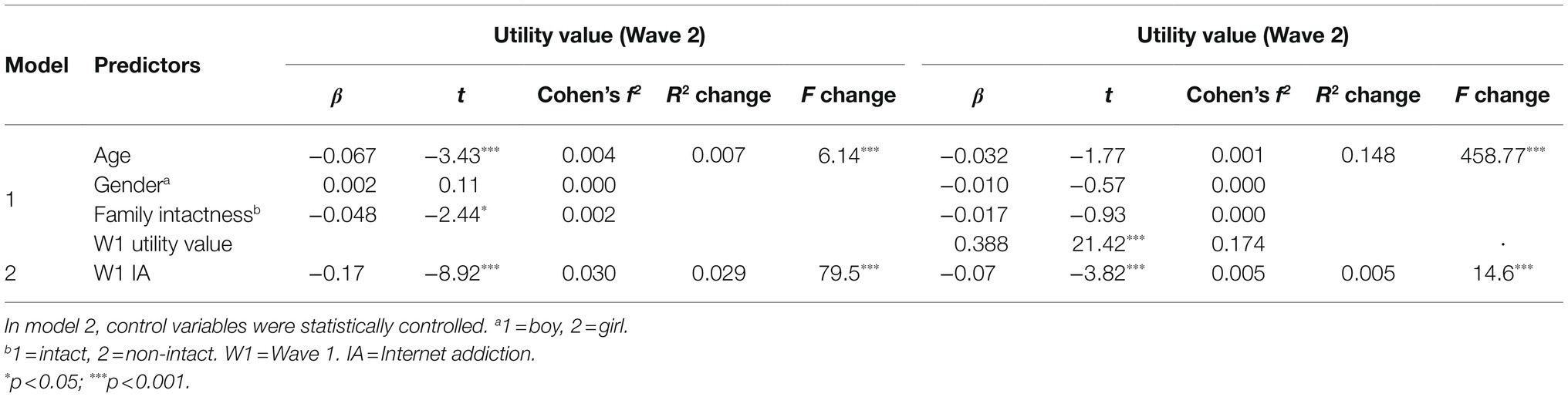

Results of hierarchical multiple regression analyses revealed significant concurrent negative effects of IA on intrinsic value (Wave 1: b = −0.30, p < 0.001, Cohen’s f 2 = 0.096; Wave 2: b = −0.27, p < 0.001, Cohen’s f 2 = 0.080, see Table 2 ) and utility value (Wave 1: b = −0.28, p < 0.001, and Cohen’s f 2 = 0.079; Wave 2: b = −0.21, p < 0.001, and Cohen’s f 2 = 0.046, see Table 3 ) at each wave after controlling gender, age, and family intactness. As to the longitudinal effect, Wave 1 IA had significant longitudinal effects on Wave 2 intrinsic value ( b = −0.21, p < 0.001, and Cohen’s f 2 = 0.042, see Table 4 ) and Wave 2 utility value ( b = −0.28, p < 0.001, and Cohen’s f 2 = 0.079, see Table 5 ). Additionally, after controlling Wave 1 intrinsic and utility values, IA at Wave 1 significantly predicted a decrease in both academic values over time ( b was −0.09 and −0.21, p s < 0.001, and Cohen’s f 2 was 0.007 and 0.046 for intrinsic and utility value, respectively, see Tables 4 , 5 ). Hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d were supported.

Table 2 . Cross-sectional regression analyses for intrinsic value.

Table 3 . Cross-sectional regression analyses for utility value.

Table 4 . Longitudinal regression analyses for intrinsic value.

Table 5 . Longitudinal regression analyses for utility value.

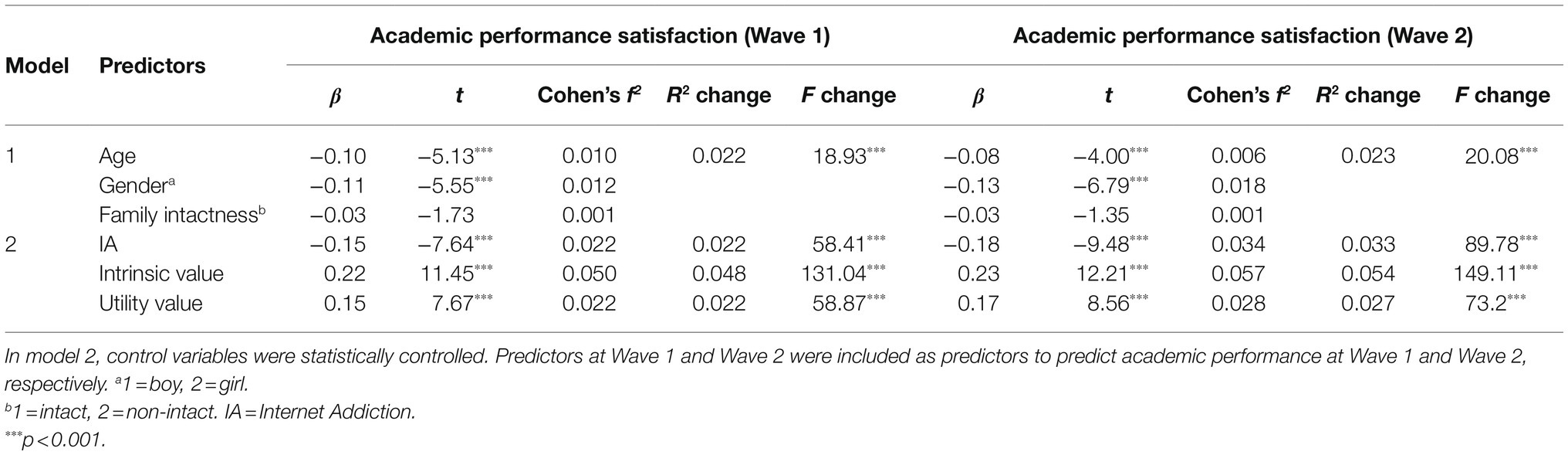

Predictive Effects of IA on Satisfaction With Academic Performance

Results of multiple regression analyses demonstrated that IA had a significantly negative influence on satisfaction with academic performance at each wave ( b was −0.15 and − 0.18, p s < 0.001, and Cohen’s f 2 was 0.022 and 0.034 for Wave 1 and 2, respectively, see Table 6 ). In addition, IA showed significant and negative prediction on Wave 2 satisfaction with academic performance ( b = −0.11, p < 0.001, and Cohen’s f 2 = 0.011, see Table 6 ). After controlling Wave 1 satisfaction with academic performance, IA significantly predicted a decrease in satisfaction with academic performance ( b = −0.07, p < 0.001, and Cohen’s f 2 = 0.004, see Table 6 ). Hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported.

Table 6 . Cross-sectional regression analyses for academic performance.

Predictive Effects of Academic Values on Satisfaction With Academic Performance

Results of multiple regression analyses revealed that intrinsic value and utility value positively predicted each wave’s satisfaction with academic performance ( b ranged between 0.15 and 0.23, p s < 0.001, Cohen’s f 2 ranged from 0.022 to 0.057, see Table 6 ). Results also showed a longitudinal prediction of intrinsic value and utility value on satisfaction with performance ( b = 0.20 and 0.14, p s < 0.001, and Cohen’s f 2 = 0.039 and 0.019 for intrinsic and utility value, respectively, see Table 7 ). Moreover, both intrinsic and utility values predicted an increase in Wave 2 satisfaction with academic performance when Wave 1 satisfaction was controlled ( b = 0.15 and 0.10, p s < 0.001, and Cohen’s f 2 = 0.020 and 0.010 for intrinsic and utility value, respectively, see Table 7 ). Results supported Hypotheses 3a, 3b, 3c, and 3d.

Table 7 . Longitudinal regression analyses for academic performance.

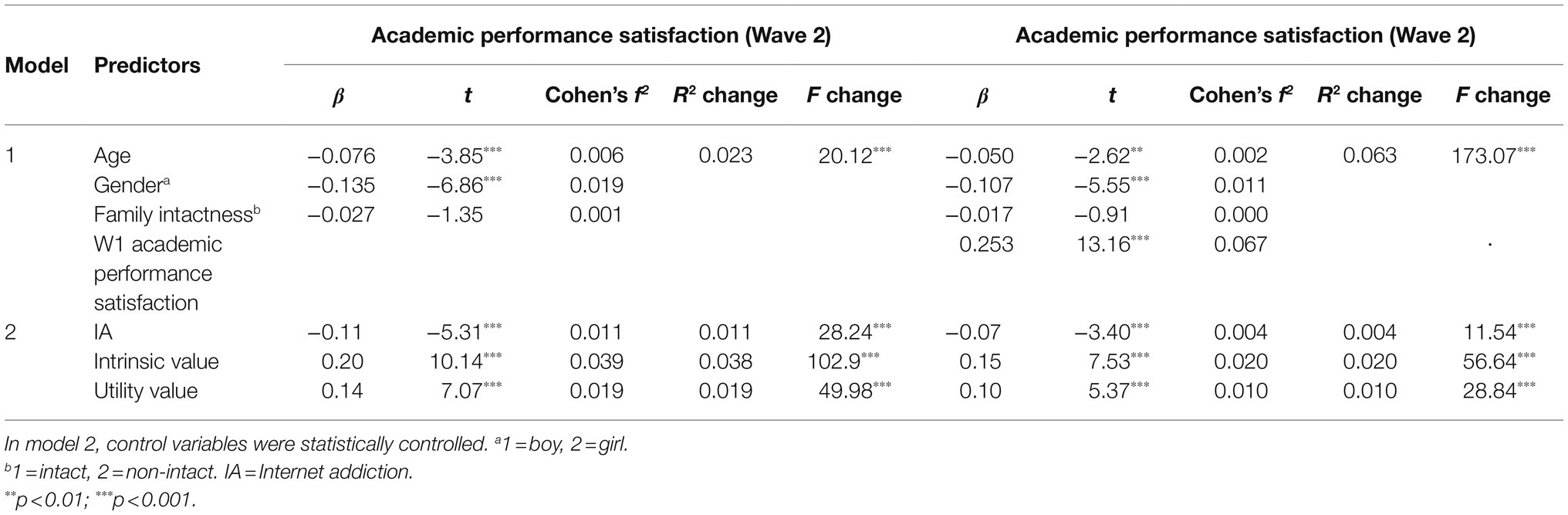

Mediating Roles of Academic Values

Results of mediation analyses via PROCESS are summarized in Table 8 . When intrinsic and utility values were examined in two separate models, results revealed significant mediating effects of both intrinsic value (see Model 1a in Table 8 ) and utility value (see Model 1b in Table 8 ). When they were added to the model simultaneously, results showed that IA at Wave 1 negatively predicted intrinsic value and utility value at Wave 2. However, only intrinsic value, not utility value, positively predicted satisfaction with academic performance, suggesting the potential mediating effect of intrinsic value only (see Model 2 in Table 8 ). The indirect effect of IA on academic performance via intrinsic value was significant ( b = −0.03, p < 0.001, see Model 2 in Table 8 ). The mediating effect of utility value was not significant (see Model 2 in Table 8 ).

Table 8 . Longitudinal mediating effect analyses of intrinsic value and utility value at Wave 2 (the mediators) for the effect of IA at Wave 1 on academic performance satisfaction at Wave 2.

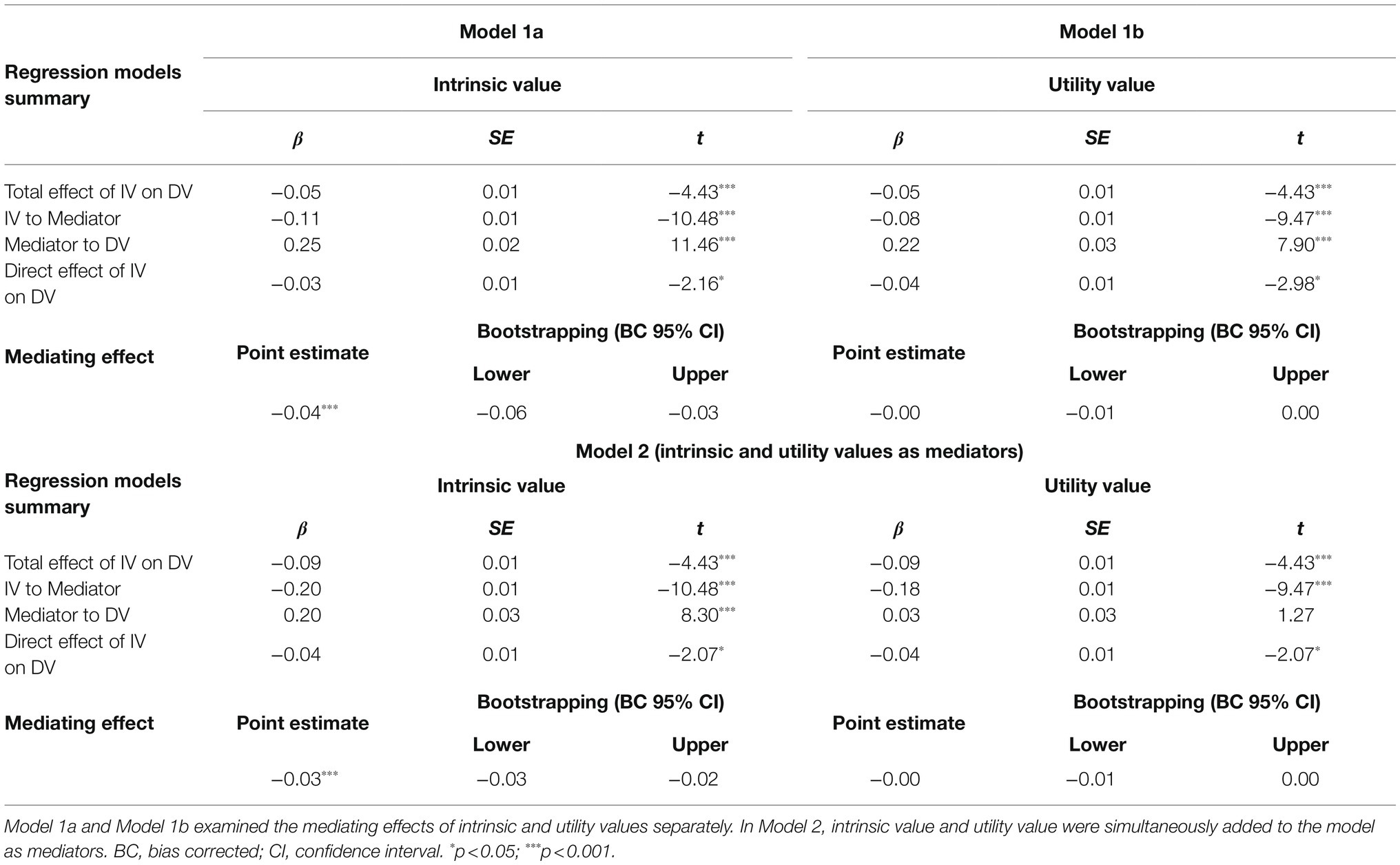

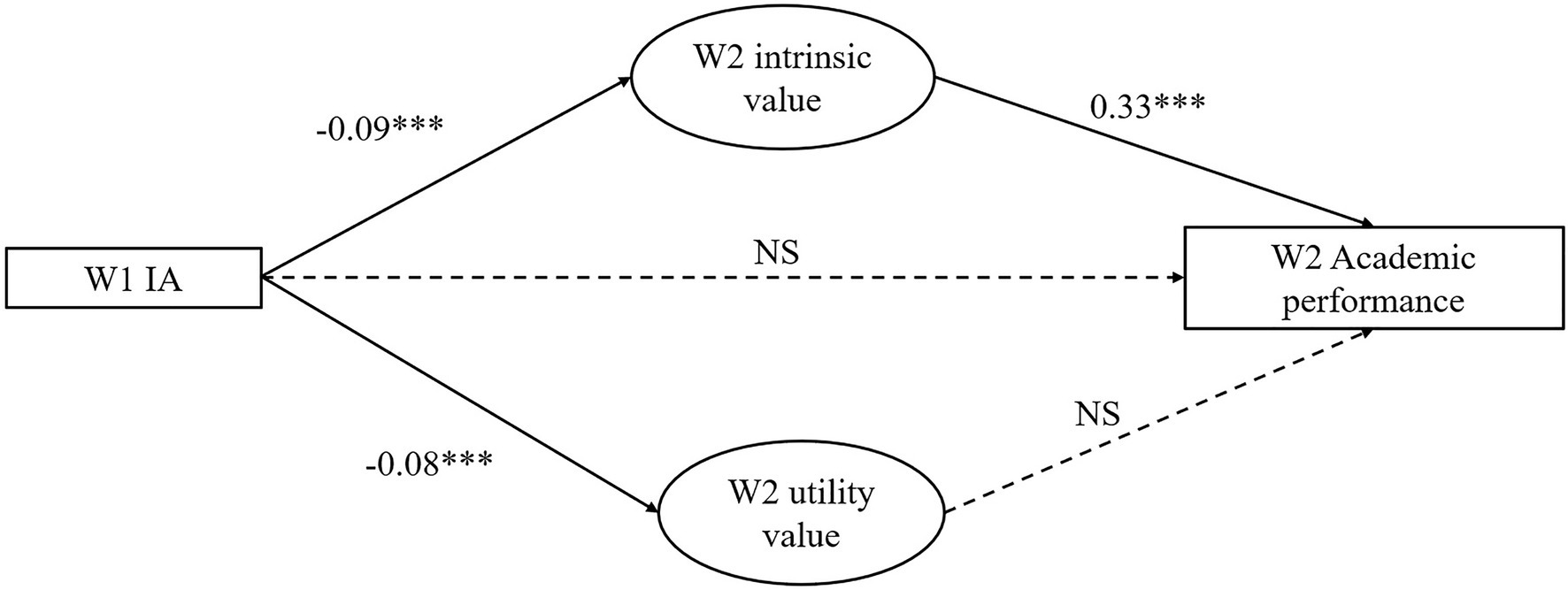

We further developed a SEM model to comprehensively understand the relationships between variables under investigation (see Figure 1 ). The SEM model included IA at Wave 1 and satisfaction with academic performance at Wave 2 as observed variables, and intrinsic and utility values at Wave 2 as latent variable. The SEM model showed adequate model fit ( χ 2 = 47.243, df = 9, CFI = 0.996, TFI = 0.990, NNFI = 0.990, RMSEA = 0.040, and SRMR = 0.011; Kline, 2015 ). Figure 1 shows the standardized coefficients in this model. IA at Wave 1 significantly and negatively predicted Wave 2 intrinsic value ( β = −0.09, p < 0.001), utility value ( β = −0.08, p < 0.001), but not satisfaction with academic performance ( p = 0.064). Wave 2 intrinsic value, but not utility value, demonstrated a significant and positive prediction on academic performance ( β = 0.33, p < 0.001). Results of SEM were in line with the PROCESS findings, which supported Hypothesis 4a but rejected Hypothesis 4b.

Figure 1 . Results of Structural equation modeling (SEM) model. *** p < 0.001.

In this study, we examined the predictive effect of IA on satisfaction with academic performance, with academic values hypothesized as mediators. With reference to the research gaps in the literature, this study has several strengths. First, instead of focusing on objective academic performance indexed by test scores, we adopted students’ satisfaction with academic performance, an indication of students’ appraisal of overall academic achievement, to better understand the research questions concerning students’ psychological motivation and values. Second, this study examined two potential mechanisms through which having IA symptoms potentially predict students’ satisfaction with academic performance through intrinsic and/or utility value. Third, a short-term longitudinal design was used to understand the predictive effects of IA on satisfaction with academic performance. Fourth, we employed a relatively large sample to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Fifth, as very few studies in this field have been conducted in the Chinese context, this study contributes to the understanding of the negative influence of IA on academic performance and the underlying mechanisms in an educational system that highly emphasizes academic success. Finally, analyses based on both multiple regression and SEM were used to address research questions in a comprehensive manner.

Findings based on multiple regression analyses generally support the proposed hypotheses, which are consistent with the existing literature. First, IA negatively predicted satisfaction with academic performance and its change over time. The findings support previous evidence suggesting negative associations between IA and academic performance ( Nemati and Matlabi, 2017 ; Anthony et al., 2021 ; Bu et al., 2021 ). Second, IA positively predicted both intrinsic and utility values and the changes over time. These findings are also in line with previous studies revealing negative influences of problem Internet use on students’ learning motivation ( Truzoli et al., 2020 ; Anthony et al., 2021 ). Third, results of multiple regression showed that both intrinsic and utility values positively predicted satisfaction with academic performance and its change over time. Although some previous studies have emphasized the downside of utility value on adolescent development, the results of the present study corroborate previous evidence highlighting the positive influence of both intrinsic and utility values ( Afzal et al., 2010 ). As mentioned earlier, Chinese cultures acknowledge both intrinsic and utility values of study. Although the education system in China has been criticized for the examination orientation, it is still perceived as the most accessible and fair approach for disadvantaged students to beat the odds and seek academic access ( Wang and Ross, 2010 ). For these students, schooling means much more than individual interests or satisfaction but “a future of comfort and dignity, a family responsibility and collective investment, and a path toward individual freedom and actualization” ( Xiang, 2018 , p. 81). These beliefs reflect instrumental value but are also rooted in spirits of hard-working and persistence that are vital for academic success. Finally, when both intrinsic and utility values were included in the mediation models, only intrinsic value, but not utility value, served as a mediator in the relationship between IA and satisfaction with academic performance. Results based on multiple regression and SEM are consistent, which generate triangulated findings for the study. The results are consistent with the widely held belief that intrinsic and utility values are distinct constructs and have different associations with adolescents’ maladjustment and psychological well-being ( Moneta and Siu, 2002 ). Students demonstrating more IA symptoms tended to regard school work as boring and consequently felt less satisfied with their academic performance, which is in agreement with previous findings ( Liu et al., 2020 ). Additionally, the mediating effect of utility value was not significant when intrinsic value was taken into account. One explanation is that utility value may include different subtypes depending on how one internalizes the extrinsic goals as a personal pursuit. If students regard the striving for performance excellence as a personal commitment, it reflects high levels of autonomy and self-determination ( Ryan and Deci, 2000 ). As results of the correlational analysis revealed a significant positive association between intrinsic and utility value, students may accept the utility of schooling and endorse the external goals. This finding echoes the idea that intrinsic value has an immediate effect on study performance, while ulitity value contributes to performance through its close association with intrinsic motivation ( Wang and Guthrie, 2004 ). We should also investigate the linkages between the two types of academic value in future studies.

There are several theoretical implications of the present findings. First, the study suggests that the negative effects of IA on academic values and satisfaction with academic performance concurrently and over time, which strengthens the theoretical proposition that IA has longitudinal adverse effects on academic outcomes ( Zhang et al., 2018 ). Second, the results underscore the importance of academic values, particularly intrinsic value, in mediating the influence of IA on satisfaction with academic performance. Students possessing high levels of intrinsic value perceive learning as exploratory, playful, and curiosity driven. According to Self-determination Theory ( Ryan and Deci, 2000 ), intrinsic value serves as “a natural wellspring of learning.” However, many online activities, including short videos, social media networks, and online games, have been designed or presented to be mentally stimulating to give users high levels and continual enjoyment ( King and Delfabbro, 2018 ). Students’ basic psychological needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness may be better satisfied by Internet use rather than by traditional learning activities, which may lead to a decrease in their engagement in school work and an increase in Internet use ( Salmela-Aro et al., 2017 ; Zhang et al., 2018 ). As existing research has paid much attention to the direct relationship between the Internet and academic performance, our results highlight the importance of examining how psychological factors mediate the relationship between adolescent problem behaviors and their development and well-being in the long run.

The finding has practical implications for teachers and social workers to help adolescents and their parents understand the negative consequences of IA in undermining academic values (i.e., meaning of study) and academic performance. Given that many teaching and learning activities are online nowadays, adolescents and parents commonly hold the belief that Internet is an indispensable part of life, and thus it cannot be addictive and the “prolonged” use of IA is not problematic. Instead, adolescents should be aware of the potential dark side of Internet use, such as the adverse effects of IA on academic values and perceived school performance ( Salmela-Aro et al., 2017 ). Furthermore, to promote satisfaction with academic performance, we need to cultivate the meaning of studying in students. In school practices, it is trendy for teachers to adopt various pedagogical strategies to spark students’ intrinsic value and cultivate active learners. Utility value, on the contrary, is often regarded as ineffective or even detrimental in adolescent development and is often associated with unhealthy teaching or parenting styles, such as excessive involvement ( Rivers et al., 2012 ). As Benabou and Tirole argued, “external incentives are weak reinforcers in the short run, and negative reinforcers in the long run” (2003, p. 489). However, our results did not reveal any negative associations between utility value and intrinsic value or academic performance. As suggested by Lin et al. (2003) , we believe it is important that teachers and parents need not eliminate all perceived utility values for high performance, especially when students accepting utility value of schooling based on a sense of commitment and self-determination.

There are several limitations of the study. First, because only two waves of data were collected, the findings are based on a short-term longitudinal study. As such, more time points should be added in future studies. Second, the scale of academic values only included a few items for the two types of values. As suggested by Ryan and Deci (2000) , it is meaningful to explore different subtypes of extrinsic motivation based on the perceived locus of causality. We recommend that more items and subtypes of utility value should be examined in future studies. Third, the present study only adopted a subjective indicator of academic performance. We believe satisfaction with performance better reflects adolescents’ self-evaluation on schooling and is closely associated with their psychological well-being. Although satisfaction with academic performance is closely correlated with GPA ( Bradley, 2006 ), it would be helpful to include test scores and/or teacher-rated performance in future studies. Fourth, this study mainly focused on academic values as mediators. Other important factors, such as academic stress, could be taken into account in future studies ( Baker, 2004 ). Finally, only self-report data were collected, which may lead to common-method variance bias. Future studies should use multiple informants’ reports to assess adolescent IA symptoms and academic performance.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Human Subjects Ethics Subcommittee at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

DS designed the research project and contributed to all the steps of the work. DD conducted data analyses, prepared the first draft, and revised the manuscript based on the comments and editing provided by DS. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This paper and the two-wave longitudinal study in the Tin Ka Ping Project P.A.T.H.S. were financially supported by Tin Ka Ping Foundation. The APC was funded by a start-up grant to DD (Project ID: P0035101).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Afzal, H., Ali, I., Aslam Khan, M., and Hamid, K. (2010). A study of university students’ motivation and its relationship with their academic performance. SSRN Electron. J. 5:9. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2899435

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Allen, J. J., and Anderson, C. A. (2018). Satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs in the real world and in video games predict internet gaming disorder scores and well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 84, 220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.034

Anthony, W. L., Zhu, Y. H., and Nower, L. (2021). The relationship of interactive technology use for entertainment and school performance and engagement: evidence from a longitudinal study in a nationally representative sample of middle school students in China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 122:106846. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106846

Bai, C., Chen, X. M., and Han, K. Q. (2020). Mobile phone addiction and school performance among Chinese adolescents from low-income families: A moderated mediation model. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 118:105406. doi: 10540610.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105406

Baker, S. R. (2004). Intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivational orientations: their role in university adjustment, stress, well-being, and subsequent academic performance. Curr. Psychol. 23, 189–202. doi: 10.1007/s12144-004-1019-9

Benabou, R., and Tirole, J. (2003). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Rev. Econ. Stud. 70, 489–520. doi: 10.1111/1467-937x.00253

Beyens, I., Vandenbosch, L., and Eggermont, S. (2015). Early adolescent boys’ exposure to internet pornography: relationships to pubertal timing, sensation seeking, and academic performance. J. Early Adolesc. 35, 1045–1068. doi: 10.1177/0272431614548069

Bradley, G. (2006). Work participation and academic performance: A test of alternative propositions. J. Educ. Work. 19, 481–501. doi: 10.1080/13639080600988756

Bu, H., Chi, X. L., and Qu, D. Y. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of the persistence and incidence of adolescent internet addiction in mainland China: A two-year longitudinal study. Addict. Behav. 122:107039. doi: 10703910.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107039

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cerniglia, L., Zoratto, F., Cimino, S., Laviola, G., Ammaniti, M., and Adriani, W. (2017). Internet addiction in adolescence: neurobiological, psychosocial and clinical issues. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 76, 174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.024

Chen, X., Huang, X., Wang, L., and Chang, L. (2012). Aggression, peer relationships, and depression in Chinese children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 53, 1233–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02576.x

Cheo, R. (2017). Small rewards or Some encouragement? Using an experiment in China to test extrinsic motivation on academic performance. Singap. Econ. Rev. 62, 797–808. doi: 10.1142/S0217590817400276

Chi, X., Hong, X., and Chen, X. (2020). Profiles and sociodemographic correlates of internet addiction in early adolescents in southern China. Addict. Behav. 106:106385. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106385

China Internet Network Information Center (2020). Statistical Report on Internet Development in China.

Google Scholar

Chou, C., and Hsiao, M.-C. (2000). Internet addiction, usage, gratification, and pleasure experience: the Taiwan college students’ case. Comput. Educ. 35, 65–80. doi: 10.1016/S0360-1315(00)00019-1

Dou, D., and Shek, D. T. L. (2021). Concurrent and longitudinal relationships between positive youth development attributes and adolescent internet addiction symptoms in Chinese mainland high school students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:1937. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041937

Eccles, J. (1983). Expectancies, Values and Academic Behaviors. Achievement and Achievement Motives. San Francisco, CA: Free man.

Education and Manpower Bureau (2003). Users’ and training manual for measuring secondary students’ performance in affective and social domains.

Enns, M. W., Cox, B. J., Sareen, J., and Freeman, P. (2001). Adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism in medical students: a longitudinal investigation. Med. Educ. 35, 1034–1042. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.01044.x

Epstein, J. A., and Botvin, G. J. (2000). Methods to decrease attrition in longitudinal studies with adolescents. Psychol. Rep. 87, 139–140. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2000.87.1.139

Floros, G., Paradisioti, A., Hadjimarcou, M., Mappouras, D. G., Karkanioti, O., and Siomos, K. (2015). Adolescent online gambling in Cyprus: associated school performance and psychopathology. J. Gambl. Stud. 31, 367–384. doi: 10.1007/s10899-013-9424-3

Froiland, J. M., and Oros, E. (2014). Intrinsic motivation, perceived competence and classroom engagement as longitudinal predictors of adolescent reading achievement. Educ. Psychol. 34, 119–132. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2013.822964

Goldhaber, D., and Özek, U. (2019). How much should we rely on student test achievement as a measure of success? Educ. Res. 48, 479–483. doi: 10.3102/0013189X19874061

Guo, J., Marsh, H. W., Parker, P. D., Morin, A. J. S., and Dicke, T. (2017). Extending expectancy-value theory predictions of achievement and aspirations in science: dimensional comparison processes and expectancy-by-value interactions. Learn. Instr. 49, 81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.12.007