.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:42px;color:#F5F4F3;}@media (max-width: 1120px){.css-s5s6ko{margin-right:12px;}} Join us: Learn how to build a trusted AI strategy to support your company's intelligent transformation, featuring Forrester .css-1ixh9fn{display:inline-block;}@media (max-width: 480px){.css-1ixh9fn{display:block;margin-top:12px;}} .css-1uaoevr-heading-6{font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-1uaoevr-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} .css-ora5nu-heading-6{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-box-pack:start;-ms-flex-pack:start;-webkit-justify-content:flex-start;justify-content:flex-start;color:#0D0E10;-webkit-transition:all 0.3s;transition:all 0.3s;position:relative;font-size:16px;line-height:28px;padding:0;font-size:14px;line-height:24px;font-weight:500;-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;color:#F5F4F3;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{border-bottom:0;color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover path{fill:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div{border-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover div:before{border-left-color:#CD4848;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active{border-bottom:0;background-color:#EBE8E8;color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active path{fill:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div{border-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:active div:before{border-left-color:#0D0E10;}.css-ora5nu-heading-6:hover{color:#F5F4F3;} Register now .css-1k6cidy{width:11px;height:11px;margin-left:8px;}.css-1k6cidy path{fill:currentColor;}

- Leadership |

- Convergent vs. divergent thinking: Find ...

Convergent vs. divergent thinking: Finding the right balance for creative problem solving

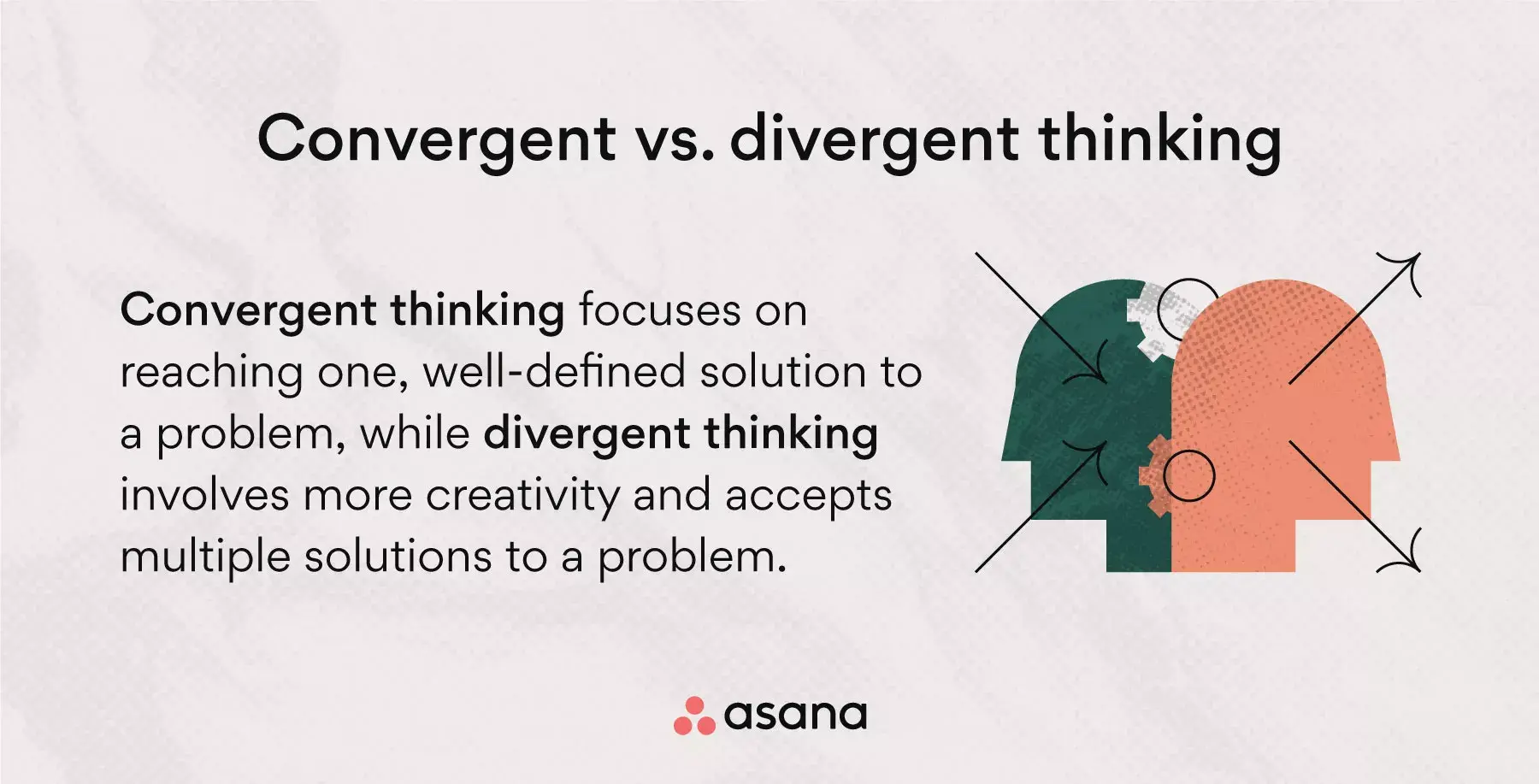

Convergent thinking focuses on finding one well-defined solution to a problem. Divergent thinking is the opposite of convergent thinking and involves more creativity. In this piece, we’ll explain the differences between convergent and divergent thinking in the problem-solving process. We’ll also discuss the importance of using both types of thinking to improve your decision making.

Have you ever taken a personality test like the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator? If so, you’ve likely answered a bunch of questions for an algorithm to tell you how you interact with the world around you. One thing this test will tell you is if you make decisions more objectively (thinkers) or decisions more subjectively (feelers).

Anatomy of Work Special Report: How to spot—and overcome—the most crucial enterprise challenges

Learn how enterprises can improve processes and productivity, no matter how complex your organization is. With fewer redundancies, leaders and their teams can hit goals faster.

![divergent thinking and problem solving [Resource Card] AOW Blog Image](https://assets.asana.biz/transform/fdc408f5-063d-4ea7-8d73-cb3ec61704fc/Global-AOW23-Black-Hole?io=transform:fill,width:2560&format=webp)

What is the difference between convergent and divergent thinking?

J. P. Guilford, a psychologist, created the terms convergent and divergent thinking in 1956. Convergent thinking focuses on reaching one well-defined solution to a problem. This type of thinking is best suited for tasks that involve logic as opposed to creativity, such as answering multiple-choice tests or solving a problem where you know there are no other possible solutions.

Divergent thinking is the opposite of convergent thinking and involves more creativity. With this type of thinking, you can generate ideas and develop multiple solutions to a problem. While divergent thinking often involves brainstorming for many possible answers to a question, the goal is the same as convergent thinking—to arrive at the best solution.

In practice, here’s what these different types of thinking might look like:

Convergent thinking: If the copy machine breaks at work, a convergent thinker would call a technician right away to fix the copy machine.

Divergent thinking: If the copy machine breaks at work, a divergent thinker would try to determine the cause of the copy machine’s malfunction and assess various ways to fix the problem. One option may be to call a technician, while other options may include looking up a DIY video on YouTube or sending a company-wide email to see if any team members have experience with fixing copy machines. They would then determine which solution is most suitable.

Convergent thinking in project management

You may use convergent thinking in project management without being aware of it. Because convergent thinking embraces structure and clear solutions, it’s natural for project managers to lean toward this approach. The benefits of convergent thinking include:

A quicker way to arrive at a solution

Leaves no room for ambiguity

Encourages organization and linear processes

There’s nothing wrong with using convergent thinking to align teams, create workflows, and plan projects. There are many instances in project management when you must reach solutions quickly. However, if you completely avoid divergent thinking, you’ll have trouble developing innovative solutions to problems.

The benefits of divergent thinking

It can be difficult as a busy project manager to slow down and think divergently. Projects have deadlines and it’s important to make decisions quickly. You may think that if you don’t come up with a solution right away, you’ll disappoint your clients or customers.

However, working too quickly can also cause you to make decisions within your comfort zone instead of taking risks. Divergent thinking can benefit you as a project manager because you’ll adopt a learning mindset. Divergent thinking can also help you:

Identify new opportunities

Find creative ways to solve problems

Assess ideas from multiple perspectives

Understand and learn from others

Fast results and predictability may work some of the time, but this way of thinking won’t help you stand out from competitors. You’ll need divergent thinking to impress clients or customers and set yourself apart from others.

Use convergent and divergent thinking for creative problem solving

You can use a mix of convergent and divergent thinking to solve problems in your processes or projects. Without using both types of thinking, you’ll have a harder time getting from point A to point B.

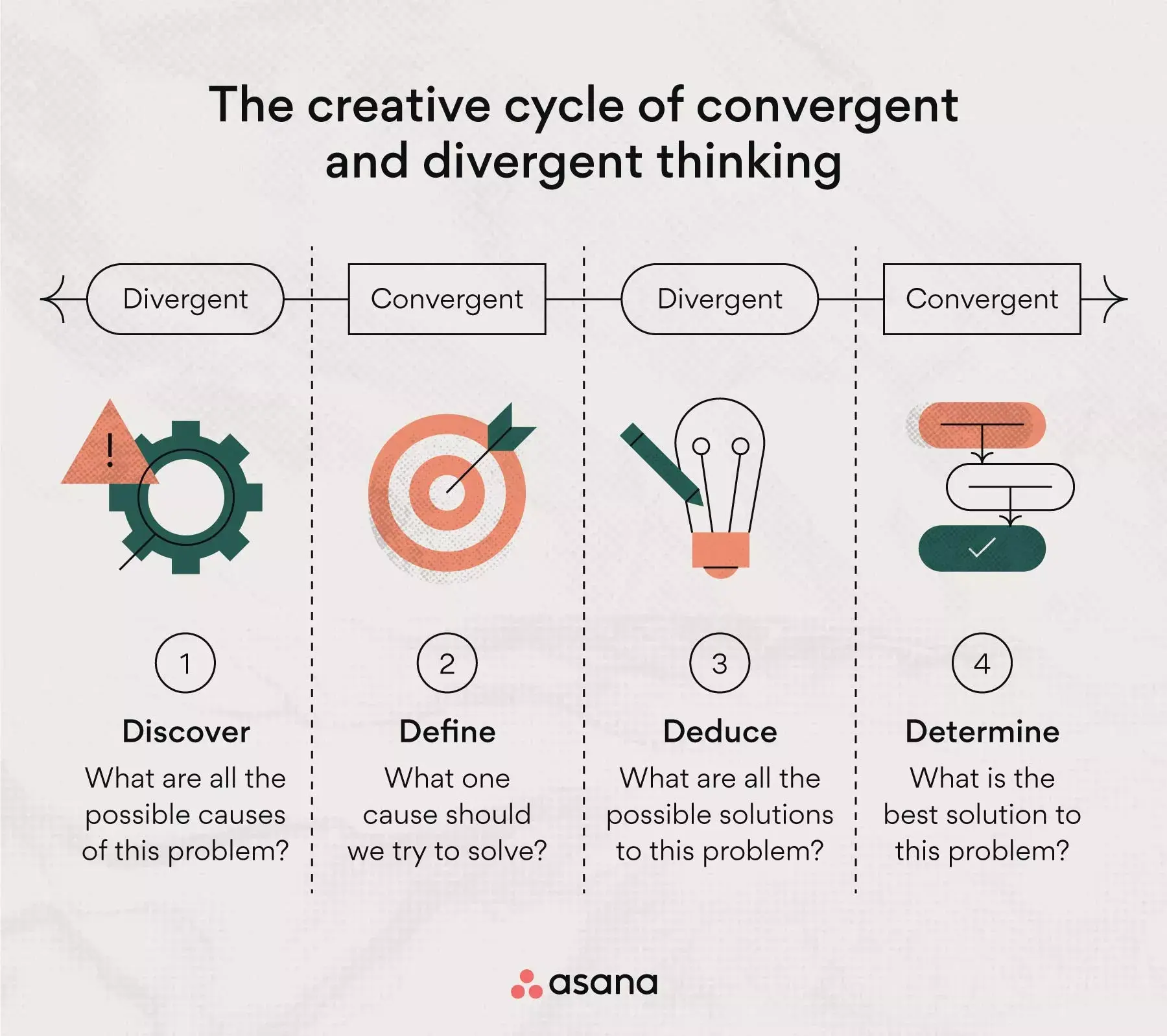

1. Discover: Divergent thinking

The first stage of creative problem solving is discovery, and in this stage, you’ll need to use divergent thinking. When you have a problem at work, the first step is to discover the cause of the problem by considering all of the possibilities.

For example, you may have had multiple projects run over budget. This begs the question: Why does this keep happening? If you used convergent thinking to answer this question, you might jump straight to a conclusion about why these budget overruns are happening. But when you use divergent thinking, you consider all possible causes of the problem.

Possible causes of budget overruns may include:

Lack of communication between team members

Improper allocation of resources

Poor project planning

Projects taking longer than expected

Now that you have all the possible causes of your problem, you can move on to the next stage of creative problem solving, which is to define your cause.

2. Define: Convergent thinking

Use convergent thinking when narrowing down the potential causes of your problem. While it’s possible that more than one cause led to your budget overruns, convergent thinking requires a focused approach to solving your problem, so you’ll need to choose the cause you think is most problematic.

Lack of communication may have contributed to your budget overruns, but if poor project planning played a bigger role in your budget woes, then it’s the cause you should go with. When you create a solution to your project planning procedure, it can result in better budgeting. Most causes are also inter-linked. So better planning will improve workplace communication even if it wasn't the primary goal.

3. Deduce: Divergent thinking

In stage three, you’ll switch back to divergent thinking as you work to find a solution for your problem. If the cause of your budget overruns is poor project planning, then possible solutions may include:

Use a project plan template

Better communication with stakeholders

More thorough research of project requirements

Implement cost control methods

You must consider all possible solutions to your problem before you can land on the best solution.

4. Determine: Convergent thinking

The last stage of problem solving is when you’ll use convergent thinking once again to determine which solution will most effectively eliminate your problem. While all the solutions you came up with in stage three may solve your problem to some degree, you should begin with one action item to address. In some instances, you may focus on more than one action item, but only do so if these items are related.

For example, after discussing the possible solutions with your team, you decide that adding cost control methods to your cost management plan should prevent budget overruns and may even help you save money.

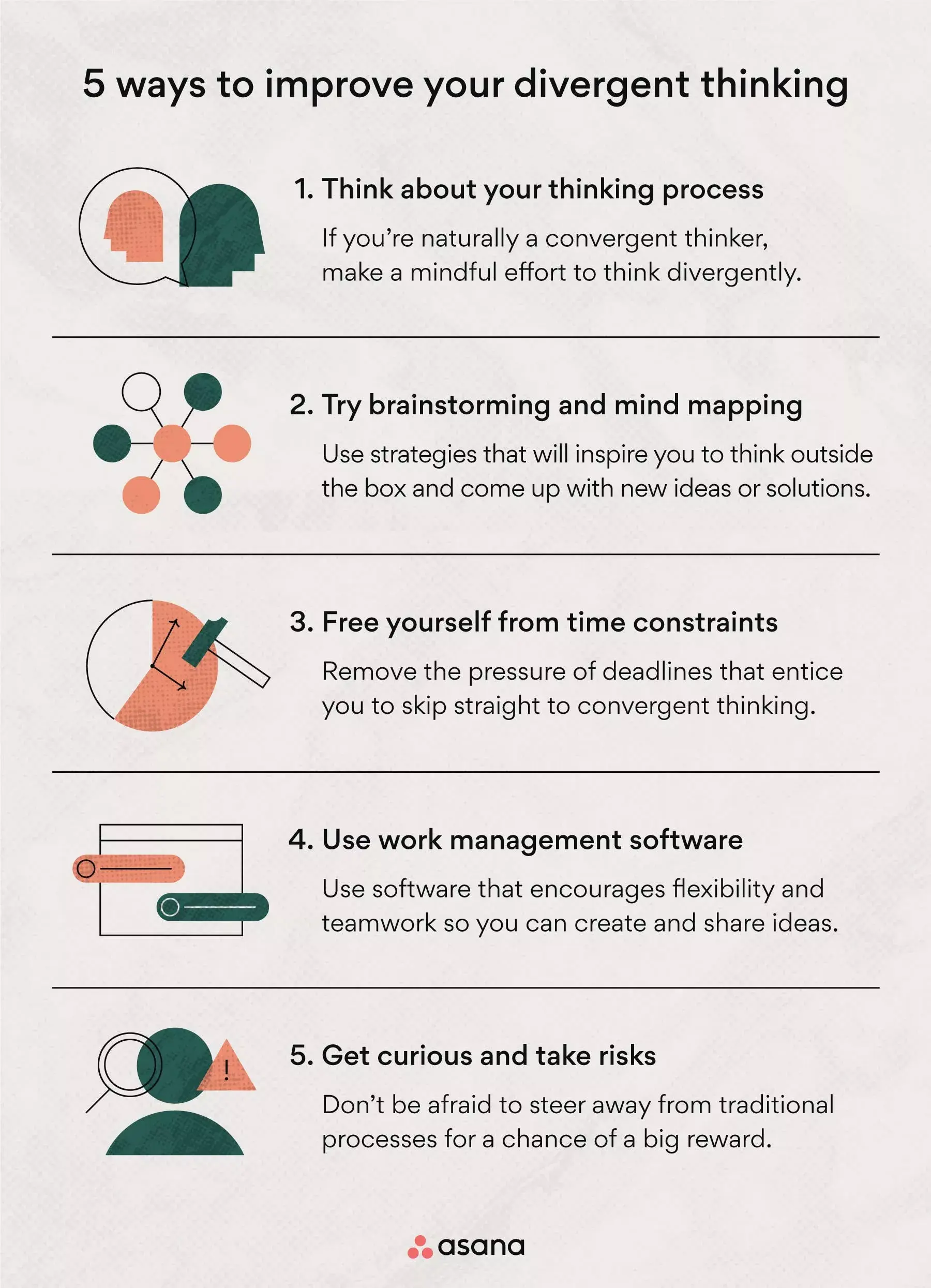

How to be a more divergent thinker

Becoming a more divergent thinker will help you exercise both sides of your brain and ensure you see problems from every angle. The following strategies can stimulate divergent thinking:

1. Think about your thinking process

Sometimes the best strategy is the simplest one. When you’re mindful about thinking divergently, it becomes easier to do. Try putting notes up in your office or adding steps in your processes that encourage divergent thinking.

Steps that encourage divergent thinking may include:

Require at least a one-hour break before sending emails regarding big decisions

Before making a big decision, put yourself in the shoes of other team members and consider their perspectives

Don’t make big decisions without vetting your decision with at least two people

By taking active steps to think about your thinking, you may realize that divergent thinking comes more naturally.

2. Try brainstorming and mind mapping

Brainstorming and mind mapping are two strategies that inspire divergent thinking because they help you think outside the box and generate new ideas. Mind mapping is a form of brainstorming in which you diagram tasks, words, concepts, or items that link to a central concept. This diagram helps you visualize your thoughts and generate ideas without worrying about structure.

You can also brainstorm in other ways. Other divergent thinking brainstorming techniques include:

Starbursting: Starbursting is a visual brainstorming technique where you put an idea on the middle of a whiteboard and draw a six-point star around it. Each point will represent the questions: who, what, when, where, why, and how?

SWOT analysis: SWOT analysis can be used for strategic planning and brainstorming. You can use it to vet the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of an idea.

Lightning decision jam: Known as LDJ for short, this brainstorming technique begins with writing down positives about a topic or what’s working regarding the topic, then writing down negatives and identifying what needs to be addressed most urgently.

Try group brainstorming sessions to get fresh ideas and solutions. If you perform these sessions regularly, you may find them enjoyable and crucial for creative problem solving.

3. Free yourself from time constraints

Everyone has deadlines they must meet. But if you’re making an important decision or trying to solve a crucial problem, try to get rid of those strict time constraints so you don’t feel pressured to skip straight to a convergent thinking approach.

Some techniques you can use to relieve pressure caused by deadlines include:

Request a meeting agenda in advance so you have time to prepare.

Use timeboxing to come up with multiple ideas in 5-10 minute intervals.

Set personal deadlines before official deadlines to give yourself some wiggle room.

It’s understandable to feel rushed to find the correct answer in a high-pressure work environment, but you won’t know that your answer is the correct one without taking the time to consider all possible solutions.

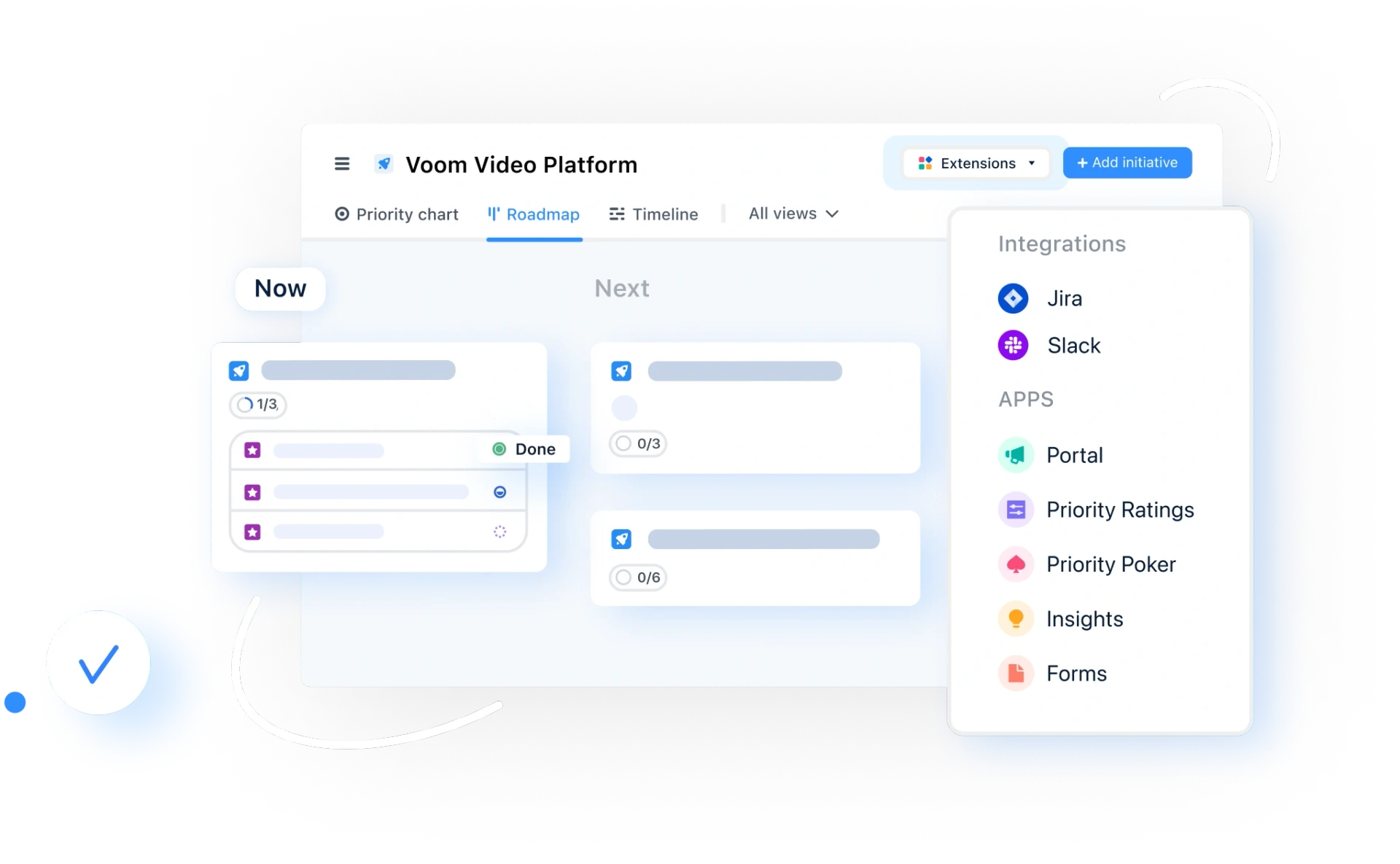

4. Use work management software

Work management is an approach to organizing projects, processes, and routine tasks in order to provide clarity to your team so they can hit their goals faster. Work management software, like Asana, can benefit both types of thinking.

If you’re having trouble with divergent thinking in particular, there are certain features of the software you may find most useful. Work management software can stimulate divergent thinking by allowing you to:

Collaborate with others on projects

Share ideas and feedback quickly

Make changes at the click of a button

Keeping your projects online is also important because your team can work together regardless of whether they work remotely or in the office.

5. Get curious and take risks

Sometimes team members settle into convergent thinking habits because they’re afraid of taking risks. While it’s important to prevent project risks when possible, you shouldn’t be afraid to steer away from traditional processes and think outside of the box.

The best project managers can switch between convergent and divergent thinking depending on whether a situation requires a quick and structured solution or an open mind. Not every situation requires subjectivity, but you’ll often need to use a mix of convergent and divergent thinking to be a successful leader.

Develop creative ideas with convergent and divergent thinking

We all have a natural cognitive approach to creative problem solving, and there’s nothing wrong with sticking to your guns. But if you want to inspire idea generation and solve problems in the best way possible, then you must use both convergent and divergent thinking.

Related resources

100+ teamwork quotes to motivate and inspire collaboration

Beat thrash for good: 4 organizational planning challenges and solutions

Work schedule types: How to find the right approach for your team

When to use collaboration vs. coordination

- Group Brainstorming Strategies

- Group Creativity

- How to Make Virtual Brainstorming Fun and Effective

- Ideation Techniques

- Improving Brainstorming

- Marketing Brainstorming

- Rapid Brainstorming

- Reverse Brainstorming Challenges

- Reverse vs. Traditional Brainstorming

- What Comes After Brainstorming

- Spider Diagram Guide

- 5 Whys Template

- Assumption Grid Template

- Brainstorming Templates

- Brainwriting Template

- Innovation Techniques

- 50 Business Diagrams

- Business Model Canvas

- Change Control Process

- Change Management Process

- NOISE Analysis

- Profit & Loss Templates

- Scenario Planning

- Winning Brand Strategy

- Work Management Systems

- Developing Action Plans

- How to Write a Memo

- Improve Productivity & Efficiency

- Mastering Task Batching

- Monthly Budget Templates

- Top Down Vs. Bottom Up

- Weekly Schedule Templates

- Kaizen Principles

- Opportunity Mapping

- Strategic-Goals

- Strategy Mapping

- T Chart Guide

- Business Continuity Plan

- Developing Your MVP

- Incident Management

- Needs Assessment Process

- Product Development From Ideation to Launch

- Visualizing Competitive Landscape

- Communication Plan

- Graphic Organizer Creator

- Fault Tree Software

- Bowman's Strategy Clock Template

- Decision Matrix Template

- Communities of Practice

- Goal Setting for 2024

- Meeting Templates

- Meetings Participation

- Microsoft Teams Brainstorming

- Retrospective Guide

- Skip Level Meetings

- Visual Documentation Guide

- Weekly Meetings

- Affinity Diagrams

- Business Plan Presentation

- Post-Mortem Meetings

- Team Building Activities

- WBS Templates

- Online Whiteboard Tool

- Communications Plan Template

- Idea Board Online

- Meeting Minutes Template

- Genograms in Social Work Practice

- How to Conduct a Genogram Interview

- How to Make a Genogram

- Genogram Questions

- Genograms in Client Counseling

- Understanding Ecomaps

- Visual Research Data Analysis Methods

- House of Quality Template

- Customer Problem Statement Template

- Competitive Analysis Template

- Creating Operations Manual

- Knowledge Base

- Folder Structure Diagram

- Online Checklist Maker

- Lean Canvas Template

- Instructional Design Examples

- Genogram Maker

- Work From Home Guide

- Strategic Planning

- Employee Engagement Action Plan

- Huddle Board

- One-on-One Meeting Template

- Story Map Graphic Organizers

- Introduction to Your Workspace

- Managing Workspaces and Folders

- Adding Text

- Collaborative Content Management

- Creating and Editing Tables

- Adding Notes

- Introduction to Diagramming

- Using Shapes

- Using Freehand Tool

- Adding Images to the Canvas

- Accessing the Contextual Toolbar

- Using Connectors

- Working with Tables

- Working with Templates

- Working with Frames

- Using Notes

- Access Controls

- Exporting a Workspace

- Real-Time Collaboration

- Notifications

- Meet Creately VIZ

- Unleashing the Power of Collaborative Brainstorming

- Uncovering the potential of Retros for all teams

- Collaborative Apps in Microsoft Teams

- Hiring a Great Fit for Your Team

- Project Management Made Easy

- Cross-Corporate Information Radiators

- Creately 4.0 - Product Walkthrough

- What's New

Divergent vs Convergent Thinking: What's the Difference?

Divergent and convergent thinking are key components of problem-solving and decision-making, often used across different fields. They represent two different ways of approaching challenges: one focuses on generating many ideas, while the other narrows them down to find the best solution.

In this article, we’ll break down divergent vs convergent thinking styles, explore their practical applications, and show how they can help make better decisions and solve complex problems effectively.

Divergence vs Convergence: Definitions

How to apply divergent and convergent thinking, the pros and cons of convergent vs. divergent thinking, tips to get the most out of divergent & convergent thinking, when to use divergent vs convergent thinking, convergent vs. divergent thinking in project management, why you need both types of thinking.

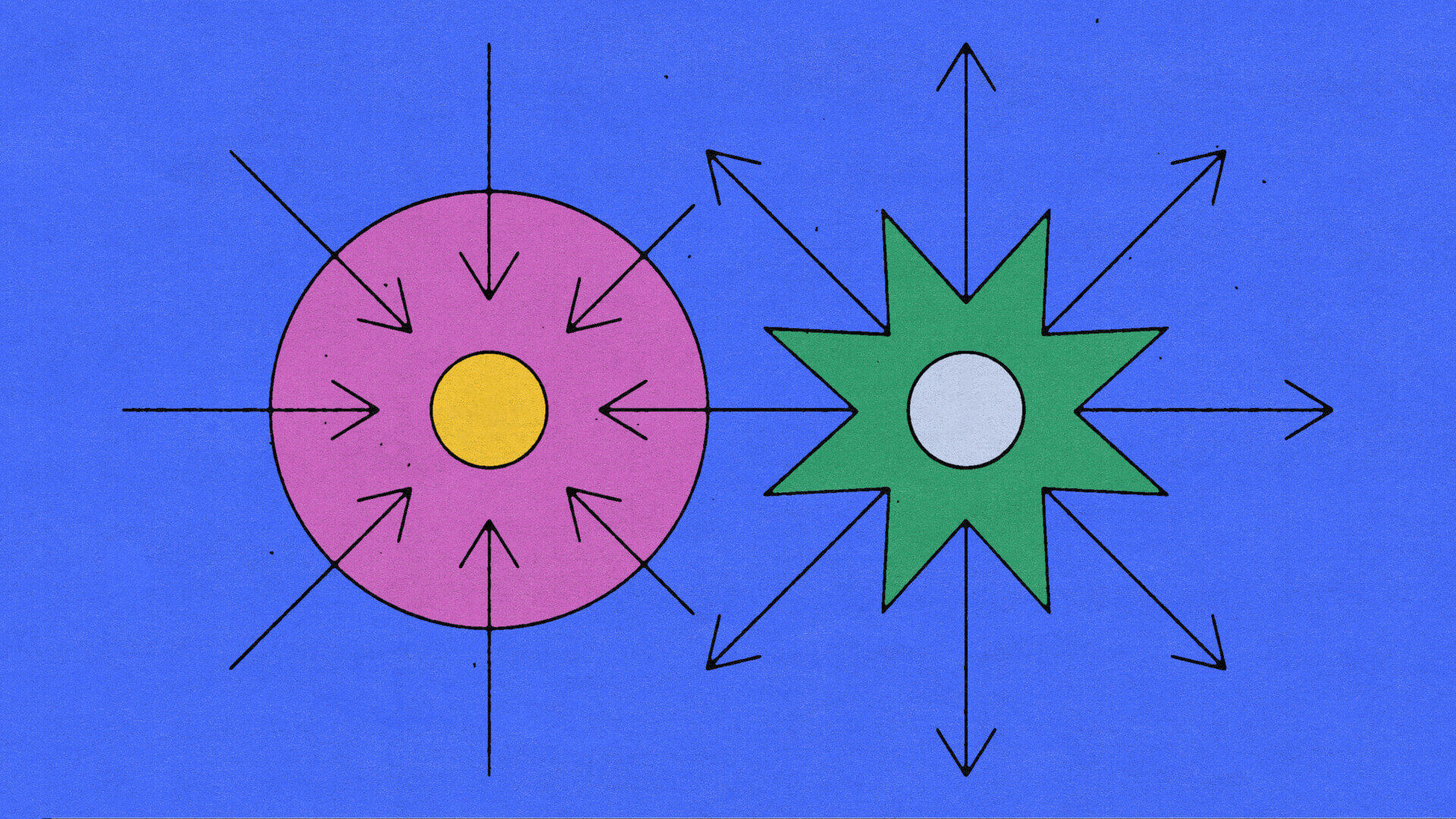

Divergence and convergence are two opposing cognitive processes that play distinct roles in problem-solving and decision-making.

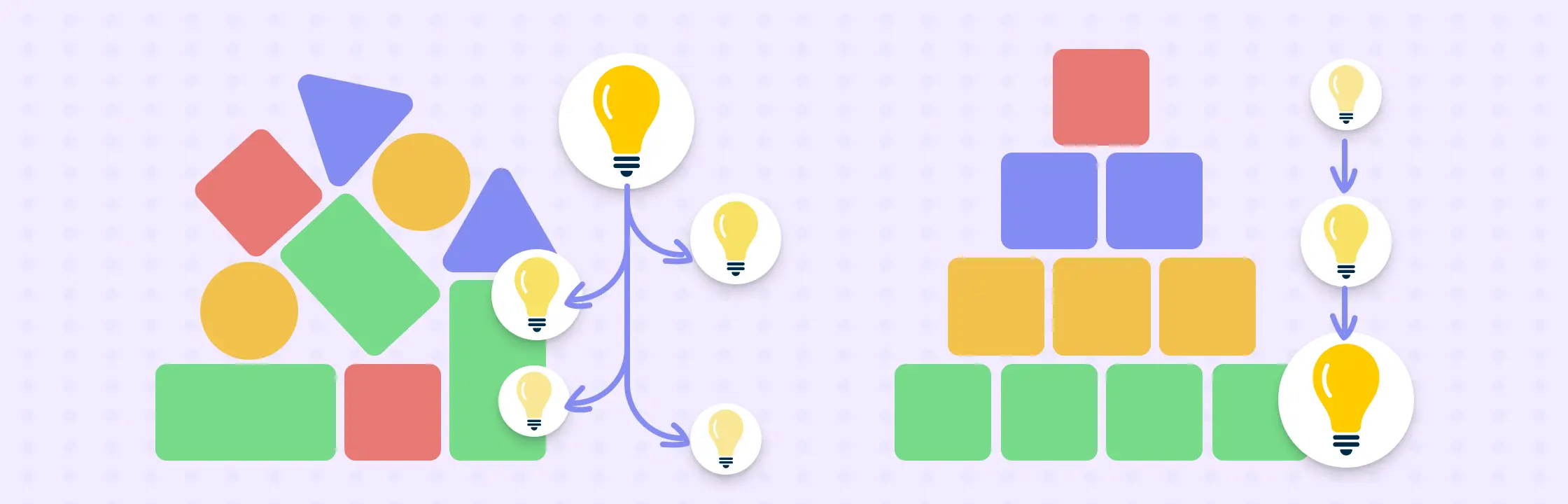

Divergent thinking is a creative process that helps generate a wide range of ideas or possibilities. It involves thinking broadly, exploring different angles, and coming up with multiple solutions to a problem. The main goal of divergent thinking is to promote creativity by allowing a free flow of thoughts without judgment or evaluation. In short, it’s about “thinking outside the box” and considering unconventional options.

Convergence

Convergent thinking, on the other hand, is a focused and analytical process aimed at selecting the best solution or idea from a set of options. It involves carefully evaluating, comparing, and narrowing down choices to identify the most effective and practical solution to a problem. Convergent thinking is about making decisions and finding the most suitable answer based on specific criteria, often guided by logic, data, and established principles.

This comparison chart gives a quick overview of the differences between divergent and convergent thinking.

Remember that divergent and convergent thinking aren’t separate stages, but often work together iteratively. You may need to switch between these thinking styles multiple times to fine-tune and improve your ideas. Additionally, involving a mix of people with different skills and thinking styles and expertise can also help increase the quality of both your divergent and convergent thinking processes.

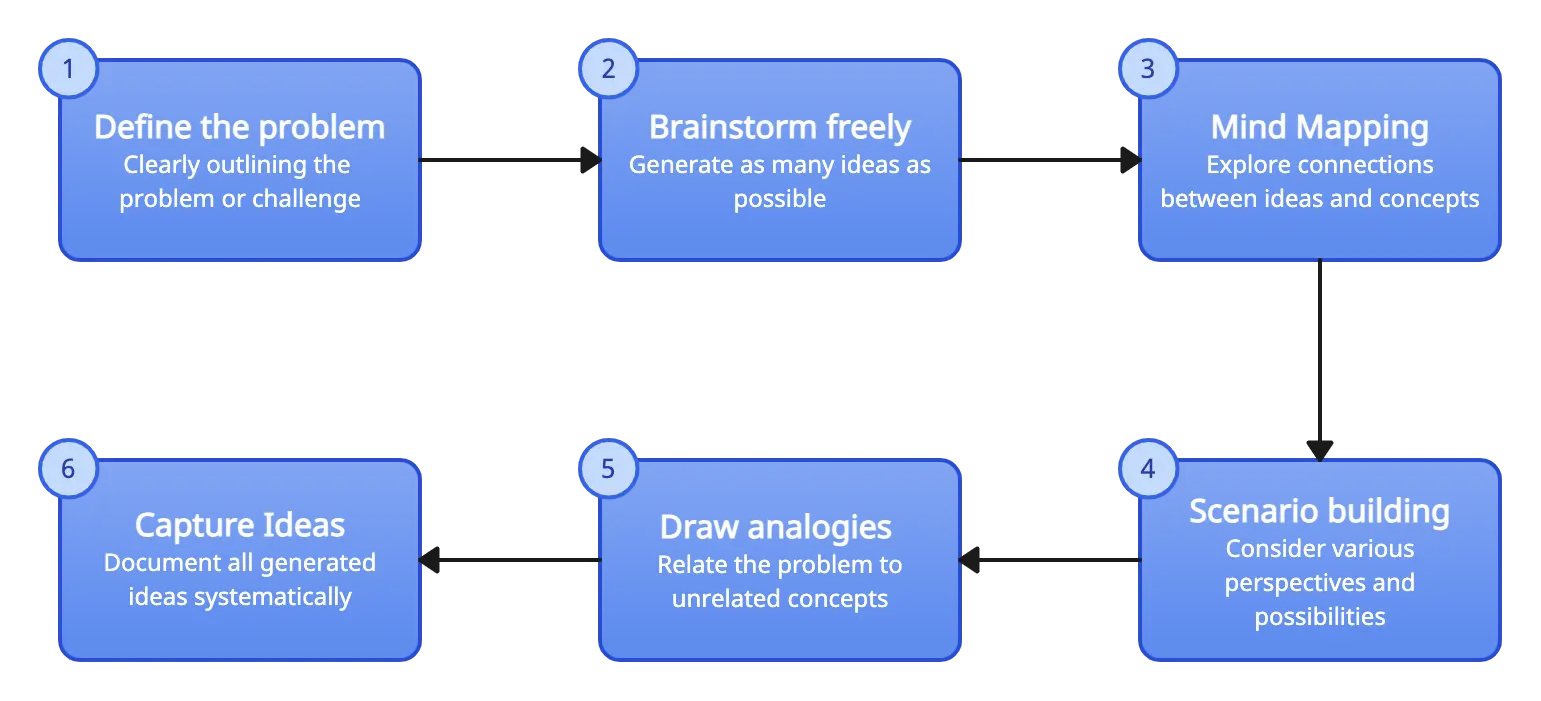

Applying Divergent Thinking

Define the problem : Start by clearly outlining the problem or challenge you’re facing. Understand its scope and boundaries.

Brainstorm freely : Hold a brainstorming session where you and your team generate as many ideas as possible. During this phase:

- Do not criticize or judge ideas.

- Welcome unconventional and even seemingly impractical ideas.

- Build upon the ideas of others to spark creativity.

Mind mapping : Use mind maps or visual diagrams to explore connections between ideas and concepts. This can help you see the bigger picture and identify potential solutions.

- Ready to use

- Fully customizable template

- Get Started in seconds

- Role play and scenario building : Imagine yourself in different scenarios related to the problem. Role-playing and scenario building can help you consider various perspectives and possibilities.

Analogies and metaphors : Draw analogies or use metaphors to relate the problem to unrelated concepts. This can help generate fresh insights and creative solutions.

Idea capture : Document all generated ideas systematically, either on paper or digitally. Organize them for easy reference during the convergent thinking phase. Use the following brainstorming board to quickly record and organize ideas.

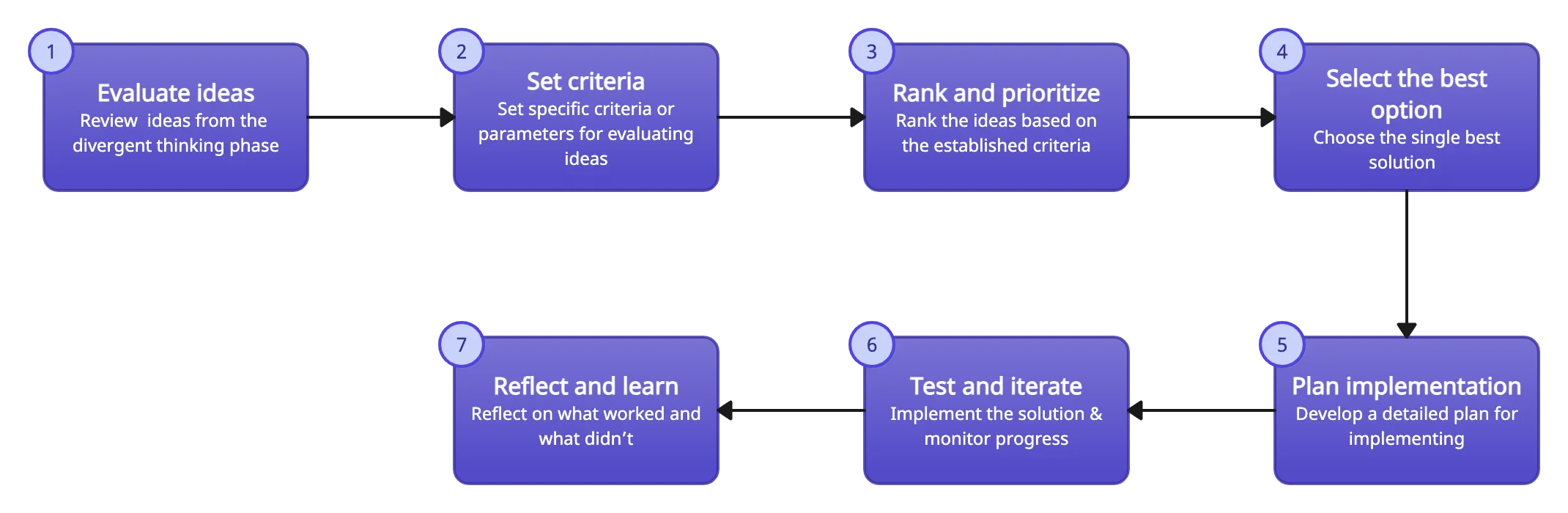

Applying Convergent Thinking

Evaluate ideas : Review the list of generated ideas from the divergent thinking phase. Consider factors like feasibility, practicality, and alignment with your goals and constraints.

Set criteria : Define specific criteria or parameters for evaluating ideas. This could include cost-effectiveness, time constraints, and the potential for implementation.

Rank and prioritize : Rank the ideas based on their alignment with the established criteria. Prioritize the top ideas that best meet your objectives.

Select the best option : Choose the single best solution or idea from the prioritized list. This decision should be well-reasoned and backed by data and analysis.

Plan implementation : Develop a detailed action plan for implementing the chosen solution. Outline the steps, resources, and timeline required for execution.

Test and iterate : Implement the chosen solution and monitor its progress. If necessary, be open to making adjustments and iterations based on feedback and results.

Reflect and learn : After implementing the solution, reflect on the process. What worked well? What could be improved? Use these insights for future problem-solving.

Convergent Thinking Pros and Cons

Divergent thinking pros and cons.

To maximize the effectiveness of divergent and convergent thinking, consider the following tips:

Clear problem definition : Start with a well-defined problem or challenge. Having a clear understanding of what you’re trying to solve or achieve is essential for effective thinking.

Time management : Set time limits for each phase of thinking. Divergent thinking sessions should encourage rapid idea generation, while convergent thinking should focus on efficient decision-making.

Diverse teams : Encourage diversity within your team. A variety of backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives can lead to more comprehensive and innovative solutions.

Document everything : Keep detailed records of all ideas and decisions made during the process. This documentation can serve as a valuable reference and help maintain continuity.

Flexibility : Be willing to adapt and adjust your thinking approach as needed. Sometimes, the process may require going back and forth between divergent and convergent thinking to refine ideas and decisions.

Visual collaboration : Use visual aids, such as whiteboards, mind maps, and diagrams, to carry out idea generation and decision-making. Visual tools can boost communication and understanding within the team. With a visual collaboration platform like Creately , you can effortlessly conduct brainstorming sessions using readily-made templates for mind maps, concept maps, idea boards and more. You can also use its infinite canvas and integrated notes capabilities to capture and organize information in one place.

Iterative approach : Know that problem-solving often involves iterating between divergent and convergent thinking. It’s a dynamic process, and fine tuning ideas is needed for success.

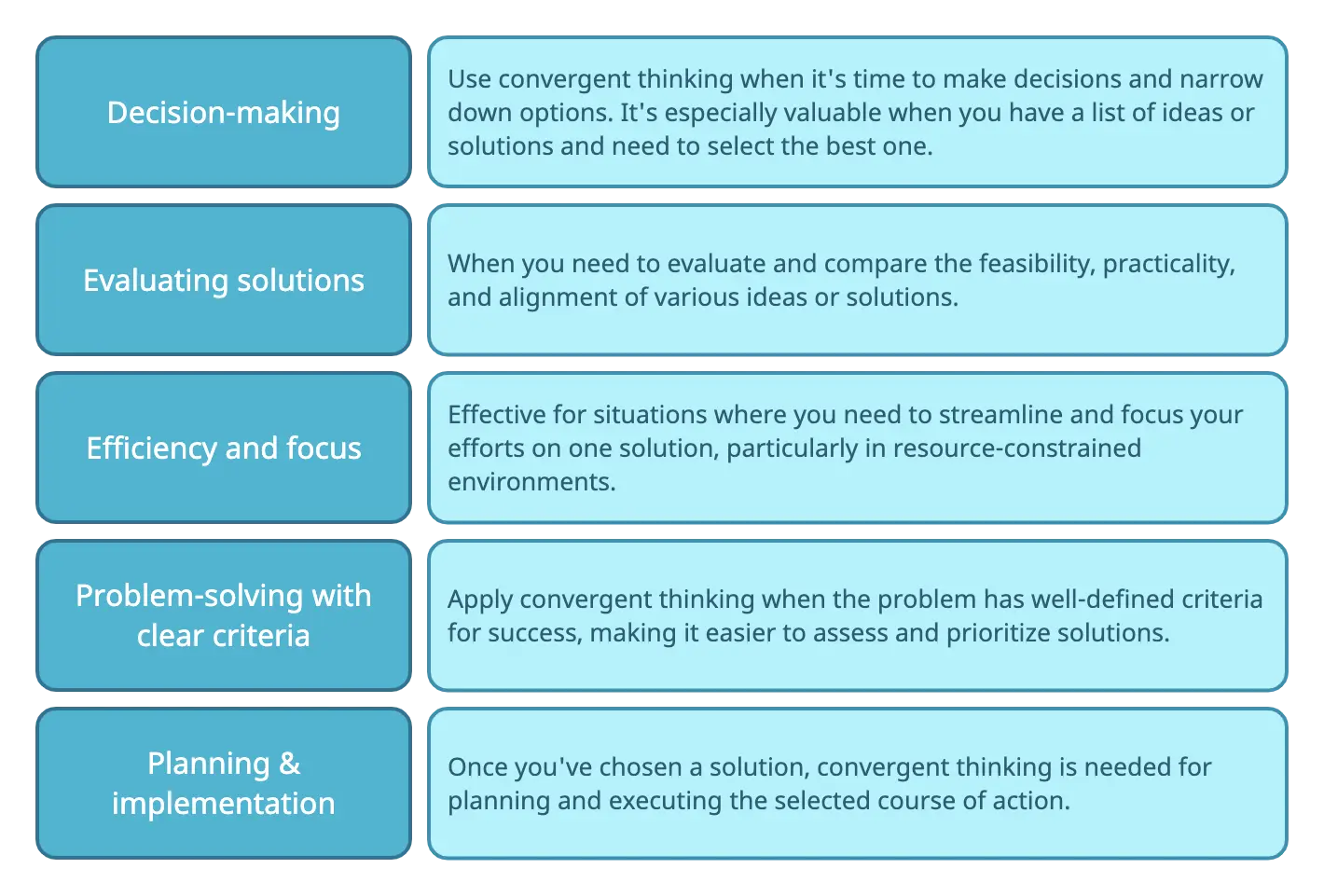

Knowing when to use divergent thinking vs convergent thinking is key to effective problem-solving and decision-making.

Divergent Thinking

Convergent Thinking

In real projects, you often switch between these two thinking styles. Divergent thinking starts things off with idea generation and exploration during planning. As the project moves forward, convergent thinking takes over to make precise decisions and execute efficiently. A good balance between these thinking styles helps project managers guide their projects effectively while allowing room for innovation when needed.

Project managers use convergent thinking to analyze data, evaluate options, and select the most suitable solutions for the project. It’s particularly helpful when you have clearly defined problems or need to allocate resources efficiently. Convergent thinking makes sure that your project stays on course and meets its objectives with precision.

Divergent thinking, on the other hand, is the thinking style you turn to when you’re dealing with complex, open-ended challenges or seeking fresh, imaginative ideas. Project managers use divergent thinking for brainstorming and idea generation without constraints. This approach is useful in exploring various possibilities, finding unique solutions, and injecting creativity into the project.

It’s important to have both divergent and convergent thinking because they play different but complementary roles in problem-solving, decision-making, and creativity. Divergent thinking, for example, helps generate a wide array of ideas and solutions as it helps break away from conventional thinking allowing you to think outside of the box.

On the other hand, convergent thinking comes into play when you need to evaluate, select, and refine ideas or solutions. It helps you make informed decisions based on defined criteria, making sure that the most promising options are chosen for further development.

Having both thinking styles in your toolkit helps comprehensive problem-solving. Divergent thinking deepens your understanding of complex problems by taking into account multiple perspectives and angles, and convergent thinking helps you narrow down options to actionable choices.

In essence, divergent and convergent thinking represent two complementary approaches to problem-solving, with divergent thinking fostering creativity and idea generation, and convergent thinking facilitating decision-making and solution selection. Both thinking styles have their unique strengths and are valuable in various contexts.

Join over thousands of organizations that use Creately to brainstorm, plan, analyze, and execute their projects successfully.

More Related Articles

Amanda Athuraliya is the communication specialist/content writer at Creately, online diagramming and collaboration tool. She is an avid reader, a budding writer and a passionate researcher who loves to write about all kinds of topics.

Divergent Thinking: What It Is, How It Works

“Bring Your Weird,” is one of the values at Panzura , a cloud-management software company based in San Jose, California. “We believe that different thinking is what makes us awesome, and we encourage everyone to be their authentic self at all times,” said Ed Peters, chief innovation officer.

What Is Divergent Thinking?

This “different thinking,” also known as divergent thinking, has resulted in many effective decisions for Panzura, including moving the company’s entire product-development and quality-assurance efforts to its Mexican nearshore unit, rather than nearshoring only parts of the process.

More on Leadership Skills 11 Essential Leadership Qualities for the Future of Work

In the 1950s, psychologist J.P. Guildford came up with the concept of convergent and divergent thinking . Convergent thinking is organized and linear, following certain steps to reach a single solution to a problem. Divergent thinking is more free-flowing and spontaneous, and it produces lots of ideas. Guilford considered divergent thinking more creative because of its ability to yield many solutions to problems.

“Divergent thinking is the ability to generate alternatives,” said Spencer Harrison, associate professor of organizational behavior at management school Insead. Divergent thinkers question the status quo. They reject “we’ve always done it this way” as a reason, he said.

Divergent thinking can and should involve convergent thinking, said Peters of Panzura. The two ways of thinking “are a yin and yang that can become a virtuous cycle and a source of great pride for the team members that create ideas, products and moments.”

Characteristics of Divergent Thinking

“All true thinking is divergent,” said Chris Nicholson, team lead at San Francisco-based Clipboard Health, which matches nurses with open shifts at healthcare facilities. “Everything else is imitation and doesn’t require thinking at all.”

Divergent thinking encompasses creativity, collaboration, open mindedness, attention to detail and other qualities.

Divergent thinking is creative , but it’s not creative thinking, which requires a complicated set of skills, Harrison said. Designers need to be empathetic to create suitable, organic solutions. That empathetic aspect of thinking is, in a way, divergent thinking because it leads to ideas, but it is not the sum and substance of divergent thinking, Harrison said.

“Engaging in divergent thinking while problem solving tends to result in more creative solutions.”

Divergent thinking and creativity are intertwined, said Taylor Sullivan, senior staff industrial-organizational psychologist at Codility , an HR tech company based in San Francisco. “Engaging in divergent thinking while problem solving tends to result in more creative solutions,” she said. “This is important because leader creativity has been shown to promote positive change and inspire followers,” she said. Creative problem-solving also enhances team performance, particularly when it involves brainstorming, Sullivan added.

“One of the key life lessons my father taught me was the importance of being willing to change your mind,” Sullivan said. Open-mindedness — the willingness to to consider new or different perspectives and ideas — is a hallmark of divergent thinking and is critical for effective leadership , she said.

Collaborative

Idea creation at Donut involves cross-department collaboration , said Arielle Shipper, vice president of operations at the New York-based company, which makes office communication tools. “We always pull in people from across the organization, even if the problem we’re working on doesn’t touch their direct role,” Shipper said. Representatives from product and engineering especially bring a perspective that helps tie products and the solutions, she said.

This collaboration involves getting input from everyone, even those who are reluctant to share thoughts, she said. “It’s important to me that everyone knows that their ideas are crucial for our work, even if they contradict what a more senior person is saying,” Shipper said. To spark conversation, she asks “is there anything you disagree with?” rather than “what do you think?” Asking the more tightly focused question, which Shipper calls a “simple but mindful shift in language” promotes a culture of acceptance and ideation.

Rethink Language

Along similar lines, Chris Nicholson and his team at Clipboard Health think divergently by escaping what he calls language traps, “when you realize that what’s happening is being obscured by the way people talk about it,” Nicholson said.

To illustrate: Clipboard Health believes that new hires should “raise the median” on the team they’re joining. That belief, though, led to rejecting people for the wrong reasons, for example not having a Ph.D on a team filled with Ph.Ds.

To get out of that language trap, the company settled on a multi-dimensional median for teams, meaning that candidates could excel in coding ability, humility or other skills .

Detail Oriented

“The devil is in the details,” said Leslie Ryan, managing director in cybersecurity and technology controls at JPMorgan Chase . “I have always thought outside the career and it has helped my career advance,” said Ryan, who has six direct reports and a team of 40.

Earlier in her career, Ryan’s employer wanted to outsource functions that many people thought couldn’t be outsourced. Trade support was one such function. “It typically required a person to be in proximity to the trader and details of the trade,” Ryan explained. By dissecting a trading assistant’s job, she was able to pinpoint certain functions, such as reconciliations and reporting, that could be outsourced.

“I tend to see the bigger picture — strategically and long term,” said Chris Noble, CEO of New York-based cloud-tech company Cirrus Nexus, who considers himself a divergent thinker. “I look at things from a perspective of not what we can’t do, but imagining what can be and where we need to go,” he said. The quality, which Noble attributes in part to his dyslexia, helps him visualize unique and forward-thinking products for Cirrus Nexus.

More on Productivity Productive Downtime Is a Startup Leader’s Secret Weapon

Build Divergent Thinking Skills

Chris Nicholson of Clipboard Health honed his ability to think divergently when he was young; his family of six debated at the dinner table and his father enjoyed playing devil’s advocate. “That led us to see different perspectives,” he said. Nicholson thinks many people are able to think divergently, but perhaps are not in environments that foster it. Divergent thinking is “creative, reality focused, and persistent,” he said.

Ask Questions

When faced with a problem, Nicholson asks questions: “Why do we think this is a problem? What do we achieve if we solve it? What data, experience and customer interactions do we have that backs up our hypotheses?” This “discovery stage,” he said, helps management understand a problem before it builds solutions. “Explore the mystery first and relish the discomfort of not knowing, rather than building a plan based on misguided beliefs,” he said.

Let Thoughts Flow Freely

Free-flowing thought is a necessary step in divergent thinking, agreed Christine Andrukonis, founder and senior partner at leadership consultancy Notion Consulting, who considers divergent thinking a hallmark of leadership. “A great leader’s superpower is to be able to see into the future and anticipate what’s next, which requires divergent thinking,” she said.

“A great leader’s superpower is to be able to see into the future and anticipate what’s next, which requires divergent thinking.”

When presented with a problem, Andrukonis lets her thoughts flow freely and writes them down. Then she steps away to think about what she’s written down and perhaps identify patterns among the thoughts. She circles those patterns, steps away again, and then connects them to the bigger picture.

“My step-away moments are literally that — going for a walk, spending time with my family, or doing something creative like painting,” Andrukonis said. Stepping away does not involve a meeting or work-related task, she said.

Listen Actively

“When I face a problem, I innately begin thinking of different ways the problem can be solved,” said Daryl Hammett, general manager, global demand generation and operations at AWS , based in Seattle, Washington.

Soon after, though, Hammett starts tapping his team for feedback. “We always start with working back from the customers’ needs, so I actively seek the advice and viewpoints of a diverse range of people, listening to their thoughts about the problems, goals, and challenges they face,” he said.

By actively listening , he practices divergent thinking skills and builds solutions with his teams. “Problems are not linear,” he said. “They’re multi-dimensional and should be addressed from a variety of angles before the best solutions appear.”

To nurture divergent thinking, Hammett encourages his team to challenge him without fear of judgment. “I am always open to feedback and change,” he said. “Having two-way conversations helps me cut through the noise and put my people first.”

He also considers divergent thinking a mark of effective leadership — it helped him navigate the management challenges of the pandemic and helps lead his team with flexibility.

Both divergent and convergent thinking have their place in a leader’s skillset, said Spencer Harrison of Insead. Leaders who deal with stable and settled situations might benefit more from convergent thinking, while leaders with unstable, volatile environments might do well to think only divergently.

“What research suggests is that divergent thinking might help you see new possibilities, but you would still need convergent thinking to realize and execute on those possibilities,” he said. “That said, because education and organizations tend to over-reward conformity, divergent thinking is probably a bit more rare and therefore likely more valuable especially in the long run over the course of a career,” Harrison said.

Peters at Panzura has his own opinion. “Sometimes the divergent thinking path wins, much of the time it doesn’t,” he said. “We create more opportunities for divergence by repeating the saying: ‘You never lose. You win or you learn.’

Great Companies Need Great People. That's Where We Come In.

- Our Mission

5 Techniques to Promote Divergent Thinking

Encouraging students to generate many solutions to a particular problem leads to more creative thinking and better problem-solving.

Service robots. ChatGPT. Drone deliveries. In a constantly evolving world, the ability to think creatively and divergently is no longer a nice-to-have attribute but an essential skill. That’s why creativity, problem-solving, and innovation are among the top 10 most critical skills of the future, according to the World Economic Forum .

With the rise of new technologies that excel at convergent thinking, it’s becoming increasingly clear that schools must prioritize divergent thinking in students to equip them for a future of unpredictable challenges and opportunities.

Divergent and Convergent Thinking

The concept of divergent thinking was founded by psychologist J. P. Guilford in 1956. Divergent thinking is the process of generating many different ideas and possibilities in an open-ended, spontaneous, and free-flowing manner. Typically, students have been trained to find the most direct path to one “right” solution. This is called convergent thinking .

However, most problems don’t have just one solution. Divergent thinking allows students to see a problem or concept from many perspectives and helps them generate numerous viable solutions, fostering innovation and creativity. Plus, because there’s no right or wrong answer, it encourages open-mindedness, leading to better solutions.

5 Techniques That Foster Divergent Thinking

1. SCAMPER is a creative thinking strategy that generates new ideas for students by asking questions to make them think about modifying and improving existing products, projects, or ideas. SCAMPER is an acronym for substitute, combine, adapt, modify, put to another use, eliminate, and rearrange .

I use the SCAMPER technique to foster divergent thinking by challenging students to develop new ideas for the work they are already doing.

For example, a few days after assigning a project, paper, or long-term assignment, I like to use this digital SCAMPER sheet to walk students through the process of SCAMPER, so that they take the time to look at what they are doing through a new lens. Students record their answers and then use the sheet to guide them to modify and improve the ideas or concepts they are working on.

2. Mind mapping uses visual diagrams to connect and organize information. It’s an effective way to promote divergent thinking and creativity in the classroom, as students have to think of how their learning connects. I use mind mapping to help students generate new ideas, explore different angles of a topic, or review how the material they are learning builds and connects.

To create a mind map, students start with a central topic and branch out with related ideas and subtopics, using different colors, shapes, and images to differentiate between them. Mind mapping uses keywords or short phrases and connects related ideas with lines or arrows.

Students can do mind mapping individually or in groups. Mind mapping fits in well as a review at the end of a lesson or the end of a unit, promoting retention and comprehension of information. I like giving students a choice when mind mapping using a digital template like this or drawing their own using colored pencils and paper.

3. Brainwriting is similar to brainstorming and is used to help at the beginning of a project or assignment. Brainwriting encourages shy or introverted students to express their thoughts by writing them down. Brainwriting also enables students to take their time to formulate ideas and build on suggestions made by others.

One popular form of brainwriting I use in class is the 6-3-3 exercise. This exercise has students get into groups of up to six participants and write down three ideas each on a piece of paper or sticky notes within three minutes . Once finished, students swap the pieces of paper and read what another participant came up with before adding three more ideas to what they read.

After students have added to the new ideas they received, the group discusses and considers all ideas and agrees upon the next steps for their project or assignment. Brainwriting is an excellent way to foster creativity in the classroom and encourage participation from all students.

4. Reverse brainstorming calls on students to brainstorm ways to make a problem worse or create more related issues. Doing this activity in class helps students identify potential obstacles and encourages critical thinking skills. I use this approach to engage students and generate new ideas in the classroom for planning a project or a paper, or before starting an assignment.

To start reverse brainstorming, I present a problem or challenge to the students and give them 5 minutes to create ways to worsen the situation. For example, I might ask students how to plan a research paper due in the coming weeks or question the wrong way to start a problem. Students then create a list of ways that would make the problem worse and explain why.

This allows students to identify potential roadblocks they may not have previously considered before starting a problem and helps them develop solutions to overcome barriers. Plus, it gets students talking about common misconceptions and errors when deciding how to tackle a problem.

5. What-if scenario planning involves having students imagine different scenarios and consider their potential outcomes. To use this technique in the classroom, I start by presenting a plan or problem to the students. Then, I ask students to imagine different what-if scenarios, such as “What if the problem were solved differently?” or “What if the situation were completely different?”

This technique allows students to consider a range of possible outcomes. It also allows them to look at content in new ways, from historical events to math problems. It’s a compelling way to promote critical thinking skills. What-if scenario planning is also an effective way to build students’ confidence in their ability to approach problems from different angles, which can be a valuable skill for future success.

By honing divergent thinking skills, students can tackle complex problems head-on and develop innovative solutions that keep pace with technological change. After all, the future belongs to those who can think differently and develop game-changing ideas.

Convergent vs. Divergent Thinking: How to Use Both to Think Smarter

by Kathleen Matyas, Senior Strategist

Nov. 17, 2022 / Frameworks & methodologies , Learning-experience design , Strategy

When you’re solving a problem, do you tend to approach it with logical reasoning? Or do you prefer to generate tons of creative ideas and see what sticks? Although most of us naturally favor one style of thinking over the other, you need both to innovate the best possible solutions.

Convergent and divergent thinking—terms coined by American psychologist J.P. Guilford in 1956—describe two complementary cognitive methods for analyzing a problem and choosing the optimal solution. For learning professionals, understanding convergent vs divergent thinking and how to use both can help you generate innovative ideas and deliver more-effective learning experiences.

Let’s take a look at convergent thinking vs divergent thinking and how to strike the right balance between the two.

Convergent vs divergent thinking: what’s the difference?

Convergent and divergent thinking are opposite forces and call for very different mindsets. While it’s impossible—and contradictory—to engage in both kinds of thinking at the same time, using both types of thinking throughout the problem-solving process will enhance the overall outcome.

The two modes of thinking work together: divergent thinking without convergent thinking isn’t actionable, and convergent thinking without divergent thinking is limiting. Let’s take a closer look at the differences between divergent thinking vs convergent thinking.

- Are You Skipping the Validation Step? Why Piloting Your Learning Matters

What is divergent thinking?

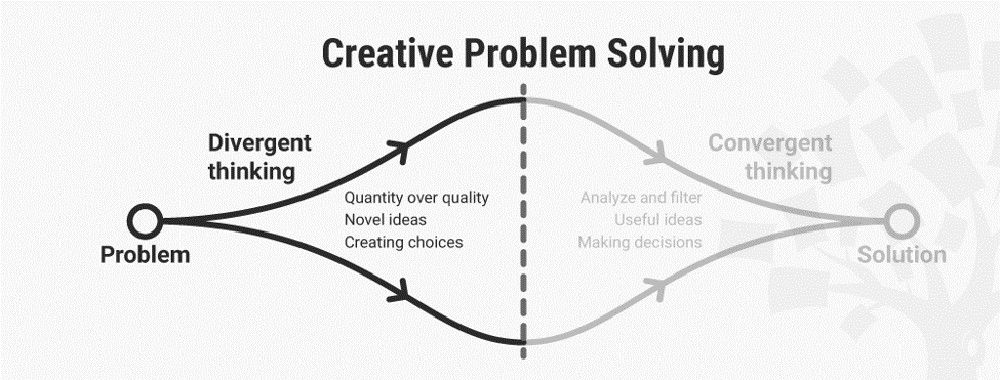

Divergent thinking calls for generating as much information and as many ideas and solutions as possible. Think quantity over quality—this kind of thinking is all about gathering information, coming up with ideas, and creativity. It’s a free-flowing form of thinking where no idea is off limits and the goal is to generate multiple paths forward.

Divergent thinking can be applied to both problem-finding and problem-solving. For example, we apply divergent thinking at the beginning of the learning-design process to accurately diagnose the learner problem and avoid assumptions—it’s part of our Learning Environment Analysis framework . We gather as much information as possible about the learner audience and context: we conduct field observations, interview learners, and review the pre-existing learning materials.

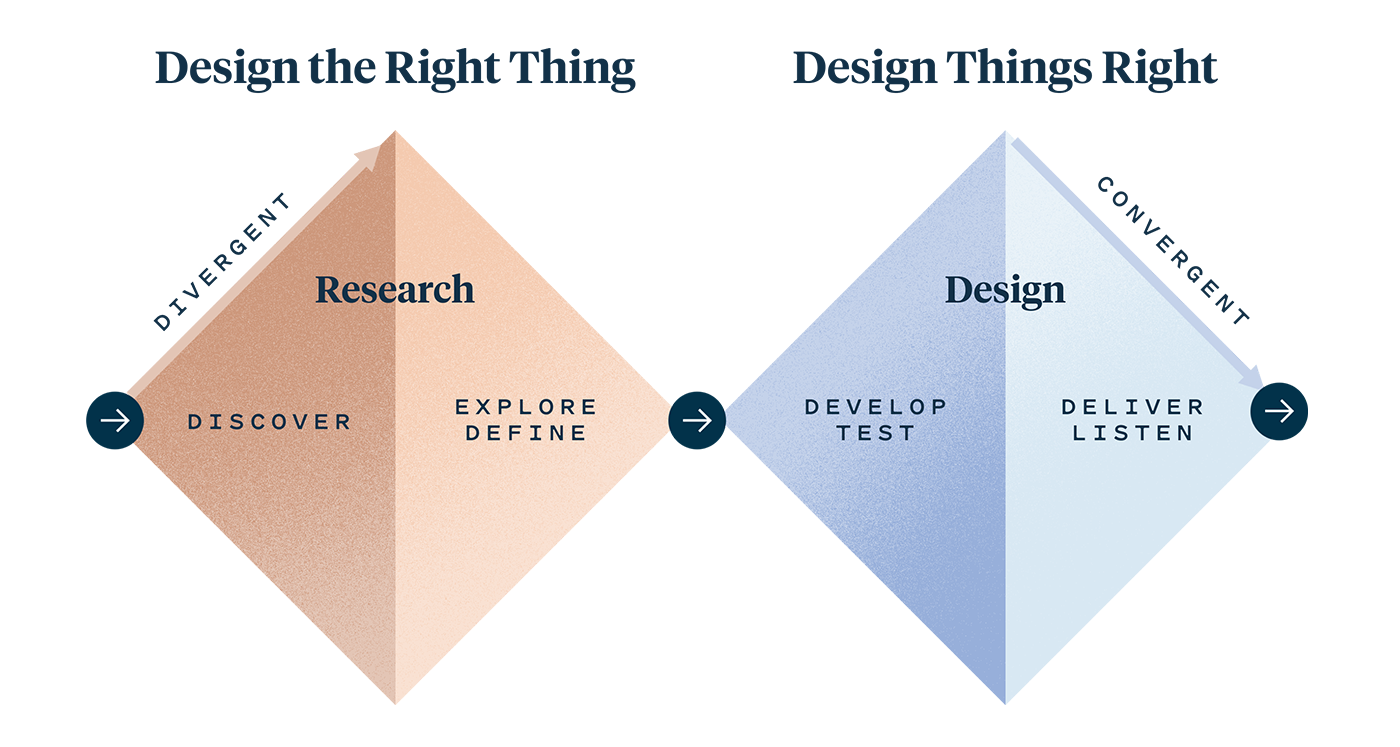

The information gathered during this divergent-research phase informs the next step in the process in which we think convergently to identify the problem and create a problem statement (we’ll talk more about that later on). Once we have our problem statement, it’s time to problem-solve. During this phase, we return once again to divergent thinking in order to brainstorm as many solutions as possible. Those ideas then inform the final stage, where we think convergently to land on the best possible solution.

Divergent thinking is a creative process, but that doesn’t mean you should forgo a structured, thoughtful session for your brainstorming. When we host brainstorms, we put plenty of thought into the prompts, divergent activities, and the structure of the session in order to brainstorm better solutions .

How to conduct a Learning Environment Analysis

In this guide, you’ll find an in-depth overview of a Learning Environment Analysis, a powerful framework for accurately understanding adult learners’ previous knowledge, current challenges, and needs so that you can design the right learning solution. Plus, get worksheets and templates for each stage of the process.

What is convergent thinking?

Divergent and convergent thinking are on opposite sides of the same coin. Where divergent thinking is about discovering, convergent thinking is about defining . You’ve gathered plenty of information and ideas, now it’s time to focus on systematically synthesizing, organizing, and categorizing it all to arrive at a well-defined solution.

The goal of convergent thinking is to take a structured approach to arrive at a clear solution. During this stage, you’ll analyze the inputs from the divergent-thinking phase to determine an outcome or actionable next step—it’s a decision-making moment defined by logical thinking, analyzing, and evaluating.

How to use both divergent and convergent thinking

By now, you’re probably starting to understand convergent vs divergent thinking and how these two methods complement one another. But what’s the best way to apply convergent vs divergent thinking?

We believe that using the Double Diamond framework —a combination of divergent and convergent thinking exercises—helps balance our focus on the content (where people tend to naturally focus) with the wants, needs, and challenges of the learners themselves.

You can delve deeper into exactly how we apply the Double Diamond framework , but what’s most important to know here is how to alternate between the two phases of thinking to help fuel better learning experiences. Since divergent and convergent thinking call for very different mindsets, it’s critical that each step remains distinct and separate.

Here’s our approach to convergent vs divergent thinking, at a glance:

Discover – Divergent We start with an exploratory research phase to better understand learners and eliminate assumptions from our work. Objective tools such as field research and learner interviews help curb pre-judging and solutioning during this phase.

Define – Convergent Next, we take the information generated during the divergent phase and analyze it to reach an actionable next step. Tools like mind mapping and decision trees help us identify patterns and common themes that we can hone to form a clear problem statement.

Develop – Divergent Shifting from problem-finding to problem-solving, we hold a strategic brainstorm to explore all possible solutions for the identified problem. Our philosophy is that quantity drives quality. We adopt a “Yes, and … “ mentality and don’t allow any judging of ideas at this stage. One of the easiest ways to snuff out innovation and creativity is to start judging information or ideas as they emerge.

Deliver – Convergent It’s decision time—we use convergent thinking to bring the entire process together. We evaluate the potential solutions we brainstormed, test and pilot our top choices, and then determine the best solution for the problem.

Strategic learning-experiences perform better

Whether you’re a creative thinker or naturally analytical, it’s important to learn how to apply both kinds of thinking throughout the learning-design process. Without using divergent and convergent thinking, you risk misdiagnosing the learner problem, overlooking possible solutions, and delivering a learning experience that falls short.

We believe that when learning is intentionally designed, amazing things can happen. With just a few simple yet strategic steps, you can easily apply convergent and divergent thinking to illuminate learners’ needs, spark innovative ideas, and converge around a solution that works best.

Brainstorming is too important to be left to chance.

Watch this on-demand webinar for strategies for brainstorming better learning solutions.

Training the next generation of crypto traders

We’re developing a first-of-its-kind learning experience that gives OKX’s new traders the confidence to succeed.

Our experiential, consumer-grade crypto learning academy is designed to deliver a comprehensive introduction to crypto trading for OKX’s 20 million users.

VetBloom A blockchain-based credentialing platform for veterinary specialties

Acist medical systems lifelike 3d product training to guide service techs on the job, best western hotels & resorts helping transform brand culture with fresh, energizing ilt.

- The Simplest Way to Avoid the Research Fail of the Yellow Walkman

- 5 Sets of Tried-and-True Resources for Instructional Designers

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Divergent Thinking

What is divergent thinking.

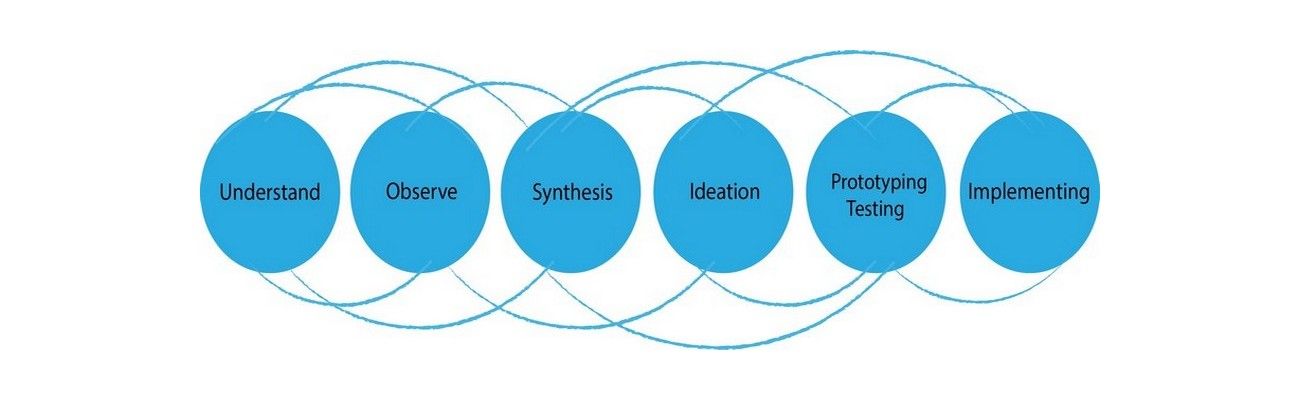

Divergent thinking is an ideation mode which designers use to widen their design space as they begin to search for potential solutions. They generate as many new ideas as they can using various methods (e.g., oxymorons) to explore possibilities, and then use convergent thinking to analyze these to isolate useful ideas.

“When you’re being creative, nothing is wrong.” — John Cleese, Famous comedian and actor

Convergent and divergent thinking

- Transcript loading…

Divergent Thinking Can Open up Endless Possibilities

The formula for creativity is structure plus diversity, and divergent thinking is how you stretch to explore a diverse range of possibilities for ideas that might lead to the best solution to your design problem . As a crucial component of the design thinking process, divergent thinking is valuable when there’s no tried-and-tested solution readily available or adaptable. To find all the angles to a problem, gain the best insights and be truly innovative, you’ll need to explore your design space exhaustively. Divergent thinking is horizontal thinking, and you typically do it early in the ideation stage of a project. A “less than” sign (<) is a handy way to symbolize divergent thinking – how vast arrays of ideas fan out laterally from one focal point: Design team members freely exercise their imaginations for the widest possible view of the problem and its relevant factors, and build on each other’s ideas. Divergent thinking is characterized by:

Quantity over quality – Generate ideas without fear of judgement (critically evaluating them comes later).

Novel ideas – Use disruptive and lateral thinking to break away from linear thinking and strive for original, unique ideas.

Creating choices – The freedom to explore the design space helps you maximize your options, not only regarding potential solutions but also about how you understand the problem itself.

Divergent thinking is the first half of your ideation journey. It’s vital to complement it with convergent thinking, which is when you think vertically and analyze your findings, get a far better understanding of the problem and filter your ideas as you work your way towards the best solution.

A Method to the “Madness” – Use Divergent Thinking with a Structure

Here are some great ways to help navigate the uncharted oceans of idea possibilities:

Bad Ideas – You deliberately think up ideas that seem ridiculous, but which can show you why they’re bad and what might be good in them.

Oxymorons – You explore what happens when you negate or remove the most vital part of a product or concept to generate new ideas for that product/concept: e.g., a word processor without a cursor.

Random Metaphors – You pick something (an item, word, etc.) randomly and associate it with your project to find qualities they share, which you might then build into your design.

Brilliant Designer of Awful Things – When working to improve a problematic design, you look for the positive side effects of the problem and understand them fully. You can then ideate beyond merely fixing the design’s apparent faults.

Arbitrary Constraints – The search for design ideas can sometimes mean you get lost in the sea of what-ifs. By putting restrictions on your idea—e.g., “users must be able to use the interface while bicycling”—you push yourself to find ideas that conform to that constraint.

© Yu Siang and Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 3.0

Learn More about Divergent Thinking

Take our Creativity course to get the most from divergent thinking, complete with templates .

Read one designer’s detailed step-by-step account of divergent thinking at work.

This UX Collective article insightfully presents an alternative approach involving divergent thinking .

Literature on Divergent Thinking

Here’s the entire UX literature on Divergent Thinking by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Divergent Thinking

Take a deep dive into Divergent Thinking with our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services .

The overall goal of this course is to help you design better products, services and experiences by helping you and your team develop innovative and useful solutions. You’ll learn a human-focused, creative design process.

We’re going to show you what creativity is as well as a wealth of ideation methods ―both for generating new ideas and for developing your ideas further. You’ll learn skills and step-by-step methods you can use throughout the entire creative process. We’ll supply you with lots of templates and guides so by the end of the course you’ll have lots of hands-on methods you can use for your and your team’s ideation sessions. You’re also going to learn how to plan and time-manage a creative process effectively.

Most of us need to be creative in our work regardless of if we design user interfaces, write content for a website, work out appropriate workflows for an organization or program new algorithms for system backend. However, we all get those times when the creative step, which we so desperately need, simply does not come. That can seem scary—but trust us when we say that anyone can learn how to be creative on demand . This course will teach you ways to break the impasse of the empty page. We'll teach you methods which will help you find novel and useful solutions to a particular problem, be it in interaction design, graphics, code or something completely different. It’s not a magic creativity machine, but when you learn to put yourself in this creative mental state, new and exciting things will happen.

In the “Build Your Portfolio: Ideation Project” , you’ll find a series of practical exercises which together form a complete ideation project so you can get your hands dirty right away. If you want to complete these optional exercises, you will get hands-on experience with the methods you learn and in the process you’ll create a case study for your portfolio which you can show your future employer or freelance customers.

Your instructor is Alan Dix . He’s a creativity expert, professor and co-author of the most popular and impactful textbook in the field of Human-Computer Interaction. Alan has worked with creativity for the last 30+ years, and he’ll teach you his favorite techniques as well as show you how to make room for creativity in your everyday work and life.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you’ve completed the course. You can highlight it on your resume , your LinkedIn profile or your website .

All open-source articles on Divergent Thinking

Design thinking, essential problem solving 101- it’s more than scientific.

- 7 years ago

How to Think and Work Divergently – 4 Ideation Methods

- 3 years ago

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share the knowledge!

Share this content on:

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

What Is Creative Problem-Solving & Why Is It Important?

- 01 Feb 2022

One of the biggest hindrances to innovation is complacency—it can be more comfortable to do what you know than venture into the unknown. Business leaders can overcome this barrier by mobilizing creative team members and providing space to innovate.

There are several tools you can use to encourage creativity in the workplace. Creative problem-solving is one of them, which facilitates the development of innovative solutions to difficult problems.

Here’s an overview of creative problem-solving and why it’s important in business.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Creative Problem-Solving?

Research is necessary when solving a problem. But there are situations where a problem’s specific cause is difficult to pinpoint. This can occur when there’s not enough time to narrow down the problem’s source or there are differing opinions about its root cause.

In such cases, you can use creative problem-solving , which allows you to explore potential solutions regardless of whether a problem has been defined.

Creative problem-solving is less structured than other innovation processes and encourages exploring open-ended solutions. It also focuses on developing new perspectives and fostering creativity in the workplace . Its benefits include:

- Finding creative solutions to complex problems : User research can insufficiently illustrate a situation’s complexity. While other innovation processes rely on this information, creative problem-solving can yield solutions without it.

- Adapting to change : Business is constantly changing, and business leaders need to adapt. Creative problem-solving helps overcome unforeseen challenges and find solutions to unconventional problems.

- Fueling innovation and growth : In addition to solutions, creative problem-solving can spark innovative ideas that drive company growth. These ideas can lead to new product lines, services, or a modified operations structure that improves efficiency.

Creative problem-solving is traditionally based on the following key principles :

1. Balance Divergent and Convergent Thinking

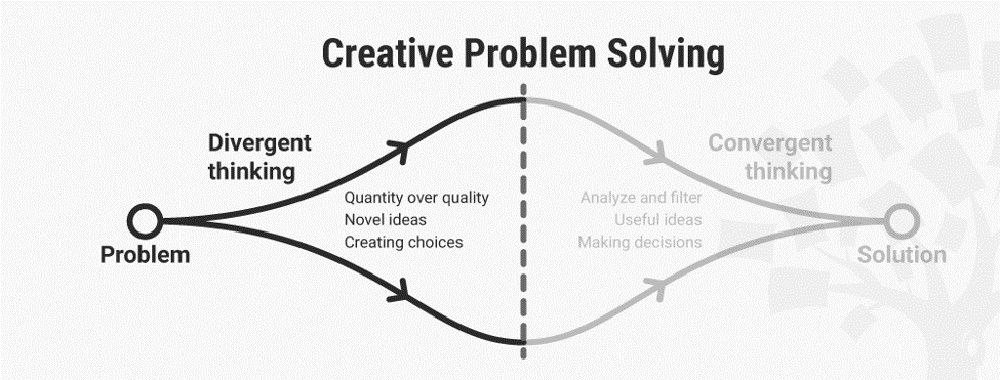

Creative problem-solving uses two primary tools to find solutions: divergence and convergence. Divergence generates ideas in response to a problem, while convergence narrows them down to a shortlist. It balances these two practices and turns ideas into concrete solutions.

2. Reframe Problems as Questions

By framing problems as questions, you shift from focusing on obstacles to solutions. This provides the freedom to brainstorm potential ideas.

3. Defer Judgment of Ideas

When brainstorming, it can be natural to reject or accept ideas right away. Yet, immediate judgments interfere with the idea generation process. Even ideas that seem implausible can turn into outstanding innovations upon further exploration and development.

4. Focus on "Yes, And" Instead of "No, But"

Using negative words like "no" discourages creative thinking. Instead, use positive language to build and maintain an environment that fosters the development of creative and innovative ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving and Design Thinking

Whereas creative problem-solving facilitates developing innovative ideas through a less structured workflow, design thinking takes a far more organized approach.

Design thinking is a human-centered, solutions-based process that fosters the ideation and development of solutions. In the online course Design Thinking and Innovation , Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar leverages a four-phase framework to explain design thinking.

The four stages are:

- Clarify: The clarification stage allows you to empathize with the user and identify problems. Observations and insights are informed by thorough research. Findings are then reframed as problem statements or questions.

- Ideate: Ideation is the process of coming up with innovative ideas. The divergence of ideas involved with creative problem-solving is a major focus.

- Develop: In the development stage, ideas evolve into experiments and tests. Ideas converge and are explored through prototyping and open critique.

- Implement: Implementation involves continuing to test and experiment to refine the solution and encourage its adoption.

Creative problem-solving primarily operates in the ideate phase of design thinking but can be applied to others. This is because design thinking is an iterative process that moves between the stages as ideas are generated and pursued. This is normal and encouraged, as innovation requires exploring multiple ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving Tools

While there are many useful tools in the creative problem-solving process, here are three you should know:

Creating a Problem Story

One way to innovate is by creating a story about a problem to understand how it affects users and what solutions best fit their needs. Here are the steps you need to take to use this tool properly.

1. Identify a UDP

Create a problem story to identify the undesired phenomena (UDP). For example, consider a company that produces printers that overheat. In this case, the UDP is "our printers overheat."

2. Move Forward in Time

To move forward in time, ask: “Why is this a problem?” For example, minor damage could be one result of the machines overheating. In more extreme cases, printers may catch fire. Don't be afraid to create multiple problem stories if you think of more than one UDP.

3. Move Backward in Time

To move backward in time, ask: “What caused this UDP?” If you can't identify the root problem, think about what typically causes the UDP to occur. For the overheating printers, overuse could be a cause.

Following the three-step framework above helps illustrate a clear problem story:

- The printer is overused.

- The printer overheats.

- The printer breaks down.

You can extend the problem story in either direction if you think of additional cause-and-effect relationships.

4. Break the Chains

By this point, you’ll have multiple UDP storylines. Take two that are similar and focus on breaking the chains connecting them. This can be accomplished through inversion or neutralization.

- Inversion: Inversion changes the relationship between two UDPs so the cause is the same but the effect is the opposite. For example, if the UDP is "the more X happens, the more likely Y is to happen," inversion changes the equation to "the more X happens, the less likely Y is to happen." Using the printer example, inversion would consider: "What if the more a printer is used, the less likely it’s going to overheat?" Innovation requires an open mind. Just because a solution initially seems unlikely doesn't mean it can't be pursued further or spark additional ideas.

- Neutralization: Neutralization completely eliminates the cause-and-effect relationship between X and Y. This changes the above equation to "the more or less X happens has no effect on Y." In the case of the printers, neutralization would rephrase the relationship to "the more or less a printer is used has no effect on whether it overheats."

Even if creating a problem story doesn't provide a solution, it can offer useful context to users’ problems and additional ideas to be explored. Given that divergence is one of the fundamental practices of creative problem-solving, it’s a good idea to incorporate it into each tool you use.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a tool that can be highly effective when guided by the iterative qualities of the design thinking process. It involves openly discussing and debating ideas and topics in a group setting. This facilitates idea generation and exploration as different team members consider the same concept from multiple perspectives.

Hosting brainstorming sessions can result in problems, such as groupthink or social loafing. To combat this, leverage a three-step brainstorming method involving divergence and convergence :

- Have each group member come up with as many ideas as possible and write them down to ensure the brainstorming session is productive.

- Continue the divergence of ideas by collectively sharing and exploring each idea as a group. The goal is to create a setting where new ideas are inspired by open discussion.

- Begin the convergence of ideas by narrowing them down to a few explorable options. There’s no "right number of ideas." Don't be afraid to consider exploring all of them, as long as you have the resources to do so.

Alternate Worlds

The alternate worlds tool is an empathetic approach to creative problem-solving. It encourages you to consider how someone in another world would approach your situation.

For example, if you’re concerned that the printers you produce overheat and catch fire, consider how a different industry would approach the problem. How would an automotive expert solve it? How would a firefighter?

Be creative as you consider and research alternate worlds. The purpose is not to nail down a solution right away but to continue the ideation process through diverging and exploring ideas.

Continue Developing Your Skills

Whether you’re an entrepreneur, marketer, or business leader, learning the ropes of design thinking can be an effective way to build your skills and foster creativity and innovation in any setting.

If you're ready to develop your design thinking and creative problem-solving skills, explore Design Thinking and Innovation , one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses. If you aren't sure which course is the right fit, download our free course flowchart to determine which best aligns with your goals.

About the Author

Try for free

Divergent Thinking

Advantages of using divergent thinking , how to implement divergent thinking , convergent vs. divergent thinking, what is the divergent thinking psychology definition, how to combine divergent and convergent thinking for optimal results , techniques to stimulate divergent thinking, .css-uphcpb{position:absolute;left:0;top:-87px;} what is divergent thinking, definition of divergent thinking.

Divergent thinking, often referred to as lateral thinking, is the process of creating multiple, unique ideas or solutions to a problem that you are trying to solve. Through spontaneous, free-flowing thinking, divergent thinking requires coming up with many different answers or routes forward.

Divergent thinking can benefit work processes in the following ways:

Best possible solutions

Increased team morale.

By dismissing the first idea, teams are encouraged to think outside the box and exercise their creativity. This encourages teamwork as they compare ideas and collectively work towards one goal, boosting team morale.

All You Need To Know About Product Management

More flexibility

When faced with a complex problem, divergent thinking allows management to adapt their plans and processes to find an appropriate new solution, encouraging proactive development as opposed to restrictive reactive thinking.

Too much divergent thinking can lead to endless ideation , and no solutions.

That’s where convergent thinking comes in handy. Convergent thinking organizes and structures new ideas, separating those with worth from those which can be left behind.

Creative problem solving begins with divergent thinking — to collect free-flowing ideas — before converging them so they’re relevant to the issue at hand.

Both stages are critical. The divergent stage pushes you to explore all possible options, while the convergent stage ensures you’ve chosen the most appropriate solutions given the context.

Convergent thinking focuses on finding a well-defined solution to a problem by embracing clear solutions and structure.

For example, if a copy machine breaks at work, someone identifying as a convergent thinker would quickly call a technician to fix the machine.

Usually, project managers embrace convergent thinking without even knowing it, so you might already be familiar with this mentality.

Benefits of convergent vs. divergent thinking:

There is no room for ambiguity.

You tend to find solutions more quickly.

Perfect for linear processes and organization.

It allows you to align teams, plan projects, and create workflows in the most efficient way possible.

It’s a straight-to-the-point kind of approach to problem-solving.

Divergent thinking refers to the creative solutions you could find for a problem. This type of thinking allows for more freedom and helps you generate more than one solution by typically using brainstorming as the cognitive method.

Although the means differ from convergent thinking, the end goal is the same — to find the best idea.

For example, a divergent thinker would try to find the cause and develop a fix for that broken copy machine from the previous example.

They might even send a company-wide email to check whether any employees have fixed copy machines before.

Benefits of divergent vs. convergent thinking:

Using creativity to find solutions to problems.

Analyze ideas from different angles.

Identify and apply new opportunities.

Helps the user adopt a learning mindset.