- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Search more than 3,000 biographies of contemporary and classic poets.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

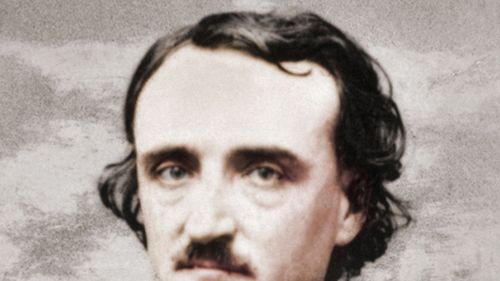

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe was born on January 19, 1809, in Boston. Poe’s father and mother, both professional actors, died before the poet was three years old, and John and Frances Allan raised him as a foster child in Richmond, Virginia. John Allan, a prosperous tobacco exporter, sent Poe to the best boarding schools and, later, to the University of Virginia, where Poe excelled academically. After less than one year of school, however, he was forced to leave the university when Allan refused to pay Poe’s gambling debts.

Poe returned briefly to Richmond, but his relationship with Allan deteriorated. In 1827, Poe moved to Boston and enlisted in the United States Army. His first collection of poems, Tamerlane, and Other Poems (George Redway), was published that year. In 1829, he published a second collection entitled Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems (Hatch & Dunning). Neither volume received significant critical or public attention. Following his Army service, Poe was admitted to the United States Military Academy, but he was again forced to leave for lack of financial support. He then moved into the home of his aunt Maria Clemm and her daughter, Virginia, in Baltimore.

Poe began to sell short stories to magazines at around this time, and, in 1835, he became the editor of the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond, where he moved with his aunt and cousin Virginia. In 1836, he married Virginia, who was thirteen years old at the time. Over the next ten years, Poe would edit a number of literary journals including the Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine and Graham’s Magazine in Philadelphia and the Broadway Journal in New York City. It was during these years that he established himself as a poet, a short story writer, and an editor. He published some of his best-known stories and poems, including “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” and “The Raven.” After Virginia’s death from tuberculosis in 1847, Poe’s lifelong struggle with depression and alcoholism worsened. He returned briefly to Richmond in 1849 and then set out for an editing job in Philadelphia. For unknown reasons, he stopped in Baltimore. On October 3, 1849, he was found in a state of semi-consciousness. Poe died four days later of “acute congestion of the brain.” Evidence by medical practitioners who reopened the case has shown that Poe may have been suffering from rabies.

Poe’s work as an editor, poet, and critic had a profound impact on American and international literature. His stories mark him as one of the originators of both horror and detective fiction. Many anthologies credit him as the “architect” of the modern short story. He was also one of the first critics to focus primarily on the effect of style and structure in a literary work; as such, he has been seen as a forerunner to the “art for art’s sake” movement. French Symbolists such as Stéphane Mallarmé and Arthur Rimbaud claimed him as a literary precursor. Charles Baudelaire spent nearly fourteen years translating Poe into French. Today, Poe is remembered as one of the first American writers to become a major figure in world literature.

Related Poets

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth, who rallied for “common speech” within poems and argued against the poetic biases of the period, wrote some of the most influential poetry in Western literature, including his most famous work, The Prelude , which is often considered to be the crowning achievement of English romanticism.

W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats, widely considered one of the greatest poets of the English language, received the 1923 Nobel Prize for Literature. His work was greatly influenced by the heritage and politics of Ireland.

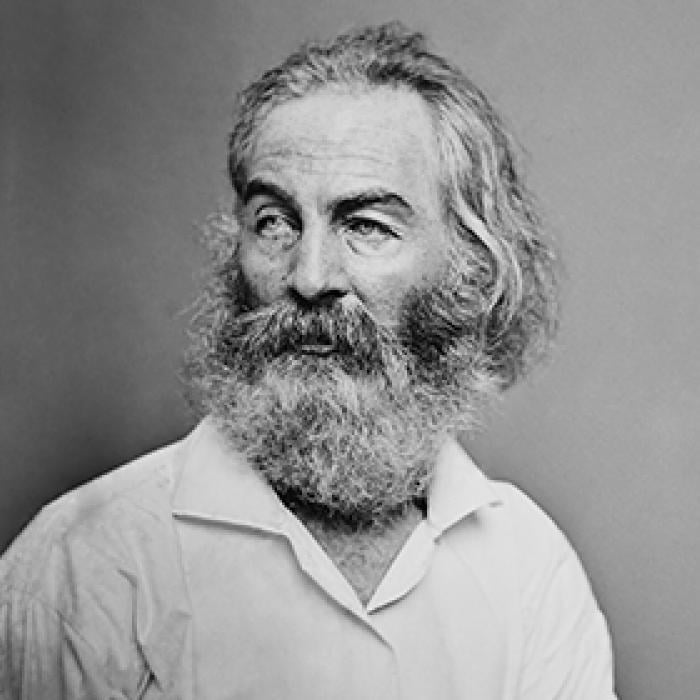

Walt Whitman

William Blake

William Blake was born in London on November 28, 1757, to James, a hosier, and Catherine Blake. Two of his six siblings died in infancy. From early childhood, Blake spoke of having visions—at four he saw God "put his head to the window"; around age nine, while walking through the countryside, he saw a tree filled with angels.

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson was born on December 10, 1830, in Amherst, Massachusetts. While she was extremely prolific as a poet and regularly enclosed poems in letters to friends, she was not publicly recognized during her lifetime. She died in Amherst in 1886, and the first volume of her work was published posthumously in 1890.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe was a writer and critic famous for his dark, mysterious poems and stories, including “The Raven,” “Annabel Lee,” and “The Tell-Tale Heart.”

Who Was Edgar Allan Poe?

Quick facts, army and west point, writing career as a critic and poet, poems: “the raven” and “annabel lee”, short stories, legacy and museum.

FULL NAME: Edgar Allan Poe BORN: January 19, 1809 DIED: October 7, 1849 BIRTHPLACE: Boston, Massachusetts SPOUSE: Virginia Clemm Poe (1836-1847) ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Capricorn

Edgar Allan Poe was born Edgar Poe on January 19, 1809, in Boston. Edgar never really knew his biological parents: Elizabeth Arnold Poe, a British actor, and David Poe Jr., an actor who was born in Baltimore. His father left the family early in Edgar’s life, and his mother died from tuberculosis when he was only 2.

Separated from his brother, William, and sister, Rosalie, Poe went to live with his foster parents, John and Frances Allan, in Richmond, Virginia. John was a successful tobacco merchant there. Edgar and Frances seemed to form a bond, but he had a more difficult relationship with John.

By age 13, Poe was a prolific poet, but his literary talents were discouraged by his headmaster and by John, who preferred that young Edgar follow him in the family business. Preferring poetry over profits, Poe reportedly wrote poems on the back of some of Allan’s business papers.

Money was also an issue between Poe and John. Poe went to the University of Virginia in 1826, where he excelled in his classes. However, he didn’t receive enough money from John to cover all of his costs. Poe turned to gambling to cover the difference but ended up in debt.

He returned home only to face another personal setback—his neighbor and fiancée Sarah Elmira Royster had become engaged to someone else. Heartbroken and frustrated, Poe moved to Boston.

In 1827, around the time he published his first book, Poe joined the U.S. Army. Two years later, he learned that his mother, Frances, was dying of tuberculosis, but by the time he returned to Richmond, she had already died.

While in Virginia, Poe and his father briefly made peace with each other, and John helped Poe get an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Poe excelled at his studies at West Point, but he was kicked out after a year for his poor handling of his duties.

During his time at West Point, Poe had fought with John, who had remarried without telling him. Some have speculated that Poe intentionally sought to be expelled to spite his father, who eventually cut ties with Poe.

After leaving West Point, Poe published his third book and focused on writing full-time. He traveled around in search of opportunity, living in New York City, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Richmond. In 1834, John Allan died, leaving Poe out of his will, but providing for an illegitimate child Allan had never met.

Poe, who continued to struggle living in poverty, got a break when one of his short stories won a contest in the Baltimore Saturday Visiter . He began to publish more short stories and, in 1835, landed an editorial position with the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond. Poe developed a reputation as a cut-throat critic, writing vicious reviews of his contemporaries. His scathing critiques earned him the nickname the “Tomahawk Man.”

His tenure at the magazine proved short, however. Poe’s aggressive reviewing style and sometimes combative personality strained his relationship with the publication, and he left the magazine in 1837. His problems with alcohol also played a role in his departure, according to some reports.

Poe went on to brief stints at Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine , Graham’s Magazine , as well as The Broadway Journal , and he also sold his work to Alexander’s Weekly Messenger , among other journals.

In 1844, Poe moved to New York City. There, he published a news story in The New York Sun about a balloon trip across the Atlantic Ocean that he later revealed to be a hoax. His stunt grabbed attention, but it was his publication of “The Raven,” in 1845, that made Poe a literary sensation.

That same year, Poe found himself under attack for his stinging criticisms of fellow poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow . Poe claimed that Longfellow, a widely popular literary figure, was a plagiarist, which resulted in a backlash against Poe.

Despite his success and popularity as a writer, Poe continued to struggle financially, and he advocated for higher wages for writers and an international copyright law.

Poe self-published his first book, Tamerlane and Other Poems , in 1827. His second poetry collection, Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems , was published in 1829.

As a critic at the Southern Literary Messenger in Richmond from 1835 to 1837, Poe published some of his own works in the magazine, including two parts of his only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym . Later on came poems such as “Ulalume” and “The Bells.”

“The Raven”

Poe’s poem “The Raven,” published in 1845 in the New York Evening Mirror , is considered among the best-known poems in American literature and one of the best of Poe’s career. An unknown narrator laments the demise of his great love Lenore and is visited by a raven, who insistently repeats one word: “Nevermore.” In the work, which consists of 18 six-line stanzas, Poe explored some of his common themes: death and loss.

“Annabel Lee”

This lyric poem again explores Poe’s themes of death and loss and might have been written in memory of his beloved wife, Virginia, who died two years prior its publication. The poem was published on October 9, 1849, two days after Poe’s death, in the New York Tribune .

In late 1830s, Poe published Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque , a collection of short stories. It contained several of his most spine-tingling tales, including “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “Ligeia,” and “William Wilson.”

In 1841, Poe launched the new genre of detective fiction with “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” His literary innovations earned him the nickname “Father of the Detective Story.” A writer on the rise, he won a literary prize in 1843 for “The Gold Bug,” a suspenseful tale of secret codes and hunting treasure.

“The Black Cat”

Poe’s short story “The Black Cat” was published in 1843 in The Saturday Evening Post . In it, the narrator, a one-time animal lover, becomes an alcoholic who begins abusing his wife and black cat. By the macabre story’s end, the narrator observes his own descent into madness as he kills his wife, a crime his black cat reports to the police. The story was later included in the 1845 short story collection, Tales by Edgar Allan Poe .

Later in his career, Poe continued to work in different forms, examining his own methodology and writing in general in several essays, including “The Philosophy of Composition,” “The Poetic Principle,” and “The Rationale of Verse.” He also produced the thrilling tale, “The Cask of Amontillado.”

From 1831 to 1835, Poe lived in Baltimore, where his father was born, with his aunt Maria Clemm and her daughter Virginia. He began to devote his attention to Virginia; his cousin became his literary inspiration as well as his love interest. The couple married in 1836 when she was only 13 years old and he was 27.

In 1847, at the age of 24—the same age when Poe’s mother and brother also died—Virginia passed away from tuberculosis. Poe was overcome by grief following her death, and although he continued to work, he suffered from poor health and struggled financially until his death in 1849.

Poe died on October 7, 1849, in Baltimore at age 40.

His final days remain somewhat of a mystery. Poe left Richmond on ten days earlier, on September 27, and was supposedly on his way to Philadelphia. On October 3, he was found in Baltimore in great distress. Poe was taken to Washington College Hospital, where he died four days later. His last words were “Lord, help my poor soul.”

At the time, it was said that Poe died of “congestion of the brain.” But his actual cause of death has been the subject of endless speculation. Some experts believe that alcoholism led to his demise while others offer up alternative theories. Rabies, epilepsy, and carbon monoxide poisoning are just some of the conditions thought to have led to the great writer’s death.

Shortly after his passing, Poe’s reputation was badly damaged by his literary adversary Rufus Griswold. Griswold, who had been sharply criticized by Poe, took his revenge in his obituary of Poe, portraying the gifted yet troubled writer as a mentally deranged drunkard and womanizer. He also penned the first biography of Poe, which helped cement some of these misconceptions in the public’s minds.

Although Poe never had financial success in his lifetime, he has become one of America’s most enduring writers. His works are as compelling today as they were more than a century ago. An innovative and imaginative thinker, Poe crafted stories and poems that still shock, surprise, and move modern readers. His dark work influenced writers including Charles Baudelaire , Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and Stephane Mallarme.

The Baltimore home where Poe stayed from 1831 to 1835 with his aunt Maria Clemm and her daughter, Poe’s cousin and future wife Virginia, is now a museum. The Edgar Allan Poe House offers a self-guided tour featuring exhibits on Poe’s foster parents, his life and death in Baltimore, and the poems and short stories he wrote while living there, as well as memorabilia including his chair and desk.

- The death of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world.

- Lord, help my poor soul.

- Sound loves to revel near a summer night.

- But as, in ethics, evil is a consequence of good, so, in fact, out of joy is sorrow born. Either the memory of past bliss is the anguish of to-day, or the agonies which are have their origin in the ecstasies which might have been.

- They who dream by day are cognizant of many things which escape those who dream only by night.

- The boundaries which divide life from death are at best shadowy and vague. Who shall say where the one ends, and where the other begins?

- With me poetry has been not a purpose, but a passion; and the passions should be held in reverence; they must not—they cannot at will be excited, with an eye to the paltry compensations, or the more paltry commendations, of mankind.

- And now—have I not told you that what you mistake for madness is but over-acuteness of the senses?—now, I say, there came to my ears a low, dull, quick sound, such as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton. I knew that sound well, too. It was the beating of the old man’s heart.

- All that we see or seem is but a dream within a dream.

- I have no faith in human perfectibility. I think that human exertion will have no appreciable effect upon humanity. Man is now only more active—not more happy—nor more wise, than he was 6000 years ago.

- [I]f you wish to forget anything upon the spot, make a note that this thing is to be remembered.

- Beauty of whatever kind, in its supreme development, invariably excites the sensitive soul to tears.

Watch “The Mystery of Edgar Allan Poe” on HISTORY Vault

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

William Shakespeare

How Did Shakespeare Die?

Christine de Pisan

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

14 Hispanic Women Who Have Made History

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Amanda Gorman

Langston Hughes

7 Facts About Literary Icon Langston Hughes

Maya Angelou

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Literatures

- Asian Literatures

- British and Irish Literatures

- Latin American and Caribbean Literatures

- North American Literatures

- Oceanic Literatures

- Slavic and Eastern European Literatures

- West Asian Literatures, including Middle East

- Western European Literatures

- Ancient Literatures (before 500)

- Middle Ages and Renaissance (500-1600)

- Enlightenment and Early Modern (1600-1800)

- 19th Century (1800-1900)

- 20th and 21st Century (1900-present)

- Children’s Literature

- Cultural Studies

- Film, TV, and Media

- Literary Theory

- Non-Fiction and Life Writing

- Print Culture and Digital Humanities

- Theater and Drama

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Poe, edgar allan.

- Thomas Wright

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.612

- Published online: 26 September 2017

At the beginning of the twenty-first century , Edgar Allan Poe was more popular than ever. The Raven and a number of his Gothic and detective tales were among the most famous writings in the English language, and they were often some of the first works of literature that young adults read. They had also entered the popular imagination—football teams and beers were named after them, and they had inspired episodes of the animated television show The Simpsons and a number of rock songs. Poe also continued to exercise a profound influence over writers and artists. Two of the most popular authors of the second half of the twentieth century , Stephen King and Isaac Asimov , acknowledged Poe as an important precursor. Countless novels published at the end of the twentieth century , such as Peter Ackroyd 's The Plato Papers: A Prophesy ( 1999 ) and Mark Z. Danielewski 's House of Leaves ( 2000 ), also bear definite traces of his influence. The Argentinean author Jorge Luis Borges , whose own works are greatly indebted to Poe, once called him the unacknowledged father of twentieth-century literature, and Poe's influence shows no signs of diminishing. Despite his enormous popularity and influence, Poe's canonical status is still challenged by certain commentators. Harold Bloom , for instance, regards Poe's writings as vulgar and stylistically flawed. Bloom follows in a long line of Poe detractors, many of whom have been amazed by the fact that what T. S. Eliot called his “puerile” and “haphazard” productions could have influenced “great” writers such as the French poets Charles Baudelaire and Stéphane Mallarmé .

Poe criticism was, however, far more favorable (and far more plentiful) over the last half of the twentieth century than previously. Poe is indeed something of a boom industry in academia. New Critics, New Historicists, psychoanalysts, and poststructuralists all find his works suggestive. Few of these critics are interested in making aesthetic judgements, however, and those who concern themselves with such things continue to express doubts about Poe's achievement.

As a result, Poe remains something of an enigma. To many he is a formative influence, a genius, and an inspiration; to others he is a shoddy stylist and a charlatan. It would be more reasonable, perhaps, to regard Poe as all of these things and to accept James Russell Lowell 's famous judgment that he was “Three fifths…genius, and two fifths sheer fudge.” Few of Poe's readers are reasonable, however, as he is one of those writers who is either loved or hated.

Poe's Persona

One of the reasons Poe has been far more popular and influential than writers who, according to some, have produced works of greater literary value is that he created, with a little help from others, a fascinating literary persona. That persona was of an author at once bohemian and extremely intellectual. The bohemian aspect was largely the creation of his “friend” Rufus Wilmot Griswold , who in his obituary of Poe described him as a depraved and demonic writer. Poe himself was responsible for the intellectual element: he presented himself to the public in his writings as an erudite and bookish scholar.

Poe's persona captured the imagination of the world; like Byron before him, he became a kind of mythical or archetypal figure. Nineteenth-century poets such as Ernest Dowson and Baudelaire (who prayed to Poe and dressed up as him) regarded Poe as the original bohemian poète maudit (a tradition in which the poet explores extremes of experience and emotional depth) and as the first self-conscious literary artist. As such, he seemed to be a prefiguring type of themselves. This legendary persona may be at odds with Poe's real personality and the actual facts of his biography, but that is beside the point. What matters is that it fascinated and continues to fascinate people.

Poe's legendary personality and life have also provided people with a context in which his writings can be read (and it is worth noting here that an account of Poe's life has traditionally appeared as a preface to anthologies of his works). As is the case with the Irish writer Oscar Wilde , we tend to read Poe's works as expressions of his (real or mythical) character and as dramatizations of his personality. This confers a degree of homogeneity on his writings; although he experimented in a variety of forms and wrote on numberless topics, we think of all of his productions as “Poe performances.”

Early Poetry

Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston on 19 January 1809 , the son of the itinerant actors David Poe Jr. and Elizabeth Arnold , both of whom died when he was still an infant. He was brought up by the Richmond tobacco merchant John Allan , with whom he had a difficult relationship. Educated in London and then, for a brief period, at the University of Virginia, Poe entered the U.S. Army in 1827 . It was always Poe's ambition to be recognized as a great poet, and in 1827 he published his first volume of verse, Tamerlane and Other Poems , under the name “a Bostonian.”

The title poem of the slim collection is a monologue by Tamerlane, the Renaissance Turkish warrior. The other poems are conventional romantic meditations on death, solitude, nature, dreams, and vanished youth in which Poe comes before us, as it were, in the theatrical garb of the romantic poet. The poems display Poe's considerable gift for imitation (which he later used to great effect in his prose parodies) and his habit of half quoting from his favorite authors. They contain countless echoes from romantic poets (especially Lord Byron). It is not, however, so much a question of plagiarism as it is of Poe serving a literary apprenticeship and placing himself within a poetic tradition.

In 1829 Poe published, under his own name, his second verse collection, Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems . It contained revised versions of some of the poems that had been published in Tamerlane (Poe was a zealous reviser) and seven new poems. Sonnet—To Science , Poe's famous poem on the antagonistic relationship between science and poetry, opens the book. It is followed by the title poem, Al Aaraaf , which has been variously interpreted as a lament for the demise of the creative imagination in a materialistic world and as an allegorical representation of Poe's aesthetic theories. The poem is characterized by its variety of meter, its heavy baroque effects, and its extreme obscurity. The volume has its lighter moments, however. Fairyland , with its “Dim vales,” “Huge moons,” and yellow albatrosses is one of Poe's first exercises in burlesque and self-parody. It was typical of Poe to include, within the same volume, serious poems and comic pieces that seem to parody those compositions.

In 1831 , wishing to leave the army, Poe got himself expelled from the West Point military academy. In that year he also brought out a third volume of poetry, Poems by Edgar A. Poe . This collection represents a considerable advance on his earlier efforts and contains famous poems such as To Helen and The Doomed City (later called The City in the Sea ). The former, which is perhaps the most beautiful of all Poe's lyrics, is a stately hymn to Helen of Troy, which in its later, revised form, contained the celebrated lines:

Thy Naiad airs have brought me home To the Glory that was Greece, And the grandeur that was Rome.

The Doomed City is a wonderful evocation of a silent city beneath the sea.

Both poems create a haunting atmosphere through the use of alliteration, assonance, measured rhythms, and gentle rhymes; they also contain words with long open vowel sounds such as “loom,” “gloom,” “yore,” and “bore” that were to become a Poe trademark. Because of Poe's fondness for such techniques, it is hardly surprising that his poems have been compared to music. Poe believed that music was the art that most effectively excited, elevated, and intoxicated the soul and thus gave human beings access to the ethereal realm of supernal beauty, a realm in which Poe passionately believed and for which he seems to have pined throughout his life. As Poe aimed to create similar effects with his verse, he attempted to marry poetry and music. This is why the rhythm of his verse is perfectly measured and often incantatory; it is also why he frequently chose words for their sounds rather than for their sense. In To Helen , for example, he writes of “those Nicéan barks of yore,” a rather confused classical allusion but a word that produces wonderfully musical vibrations.

Poe offers us what he called “a suggestive indefiniteness of meaning with a view of bringing about vague and therefore spiritual effects .” Decadent and symbolist poets of the nineteenth century , including Baudelaire and Paul Verlaine , were heavily influenced by Poe's method, and they consciously imitated his “word-music.” They also regarded Poe as their most important precursor because of his theoretical statements about poetry. Indeed, Poe was (and perhaps remains) as famous a critic and theoretician of verse as he was a poet. He is particularly remembered for his powerful denunciation of didactic poetry and for his emphasis on the self-consciousness and deliberateness of the poet's art.

Most of Poe's important theoretical pronouncements were made in the essays and lectures he wrote toward the end of his life. In Poems he wrote a prefatory “Letter to Mr —,” which represents his first theoretical statement about verse. Here he defined poetry as a pleasurable idea set to music. He also argued, with more than a slight nod to the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge , that poetry “is opposed to a work of science by having, for its immediate object, pleasure, not truth; to romance, by having for its object an indefinite instead of a definite pleasure.” At its best, Poe's poetry embodies such ideas by creating vague yet powerful atmospheric effects and by giving the reader intense aesthetic pleasure.

Poe's early poetry received mixed reviews and failed to establish him as either a popular or a critically acclaimed author. Later commentators, such as T. S. Eliot and Walt Whitman , criticized its limited range and extent; they also bemoaned its lack of intellectual and moral content. Others dismissed Poe as a mere verse technician; Emerson famously referred to him as “the jingle man.” Poe's verse was, however, revered by later nineteenth-century poets such as Mallarmé and Dowson, and considering his influence on such Decadent and symbolist writers, he can perhaps be regarded as the most influential American poet of that century after Whitman.

Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque

Numerous connections exist between Poe's early verse and the short stories he started to write for magazines and newspapers around 1830 . (Poe's decision to turn his hand to prose was partly because of the lack of commercial and critical success achieved by his poetry.) In some of his stories Poe included poems; he also returned to forms, such as the dramatic monologue and the dialogue between disembodied spirits, that he had used in poems such as Tamerlane and Al Aaraaf . And yet Poe's tales are clearly distinguished from his early verse, most obviously by their variety of mood, content, and theme. Poe seems to have been liberated as a writer when he turned from romantic verse to the more flexible, capacious, and traditionally heterogeneous genre of the short story. He now had at his disposal a multitude of tones and devices, and in the twenty-five stories that he wrote in the 1830s and that were collected in the anthology Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (2 vols., 1840 ), he exploited these to great effect.

In fact, such is the diversity of the style and mood of Poe's early stories that the division of the contents of Tales into the two categories of grotesque and arabesque seems simplistic and inadequate. Poe's grotesques are comic and burlesque stories that usually involve exaggeration and caricature. In this group we can include the tales Lionizing and The Scythe of Time (earlier called A Predicament ), which are satires of the contemporary literary scene. Another characteristic of Poe's grotesque stories is the introduction of elements of the ludicrous and the absurd. In the tale Loss of Breath , the protagonist literally loses his breath and goes out in search of it. It is a shame that Poe's early grotesques are generally neglected, because not only do they testify to his range and resourcefulness as a writer, but some of them are compelling and funny. The neglect results partly from the fact that, in order to be appreciated, they require extensive knowledge of the literary and political state of antebellum America and partly because they have been overshadowed by his arabesque tales.

Poe's arabesque tales are intricately and elaborately constructed prose poems. The word “arabesque” can also be applied to those stories in which Poe employed Gothic techniques. Gothic literature, which typically aimed to produce effects of mystery and horror, was established in the latter half of the eighteenth century by writers such as the English novelist Anne Radcliffe and the German story writer E. T. A. Hoffmann . By the beginning of the nineteenth century , the Gothic short story had become one of the most popular forms of magazine literature in England and America.

It is generally agreed that Poe's particular contribution to Gothic literature was his use of the genre to explore and describe the psychology of humans under extreme and abnormal conditions. Typically, his characters are at the mercy of powers over which they have no control and which their reason cannot fully comprehend. These powers may take the form of sudden, irrational impulses (“the imp of the perverse” that inspires the protagonist of Berenice to extract the teeth of his buried wife, for example), or as is the case with the eponymous hero of William Wilson , a hereditary disease. Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque contains some of Poe's most famous Gothic productions, including Morella , Ligeia , and Berenice (the stories of the so-called “marriage group,” which concern the deaths of beautiful young women), along with perhaps the most popular of all his tales, The Fall of the House of Usher .

“Usher” is a characteristic arabesque production. It exhibits many of the trappings of Gothic fiction: a decaying mansion located in a gloomy setting, a protagonist (Roderick Usher) who suffers from madness and a peculiar sensitivity of temperament inherited from his ancient family, and a woman (his sister) who is prematurely buried and who rises from her tomb. Yet from Gothic clichés such as these, Poe produced a tale of extraordinary power. Indeed, perhaps only Stephen King in The Shining ( 1977 ) has succeeded in investing a building with such horror and in conveying the impression that it is alive.

Apart from the grotesque and arabesque stories, Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque includes other varieties of writing. Hans Phaall has been classed as science fiction, and King Pest is a surreal historical adventure. Several stories contain elements of all of these genres; Metzengerstein , for example, is at once a work of historical fiction, a powerful Gothic tale, and a witty and grotesque parody of the latter genre. The diversity of the contents of the tales, and the variety of theme and style within individual stories, must be seen in the context of the original form in which they appeared. All of the tales were first published in popular newspapers and magazines from 1832 to 1839 . The audience for such publications was extremely heterogeneous, and Poe was clearly trying to appeal to as large a cross-section as possible. We should also remember that, unlike subscribers to weightier publications, the magazine- and newspaper-reading public had a very limited attention span. Readers craved novelty, sensation, and diversity.

Poe was profoundly influenced by the tastes of this public. In a letter to Thomas Willis White , a newspaper editor, he remarked that the public loves “the ludicrous heightened into the grotesque: the fearful colored into the horrible: the witty exaggerated into the burlesque: the singular wrought out into the strange and mystical.” In Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque this is precisely what he gave them. The most obvious characteristic of his stories is their sensationalism: they include accounts of balloon journeys to the moon, premature burials, encounters with the devil, and a number of gruesome deaths.

From the early 1830s Poe planned to gather together his short stories and publish them in book form. In the mid-1830s he unsuccessfully offered for publication a collection of stories under the title Tales of the Folio Club . Poe devised an elaborate plan for the “Folio Club” volume. The tales were to be read out, over the course of a single evening, by various members of a literary club, and each story was to be followed by the critical remarks of the rest of the company. The book was evidently intended as a satire of popular contemporary modes of fiction and criticism; as such it can be compared to the work of Poe's English contemporary, Thomas Love Peacock . The satirical intent is clearly indicated by the names and descriptions of the various club members, which include “Mr Snap, the President, who is a very lank man with a hawk nose.” Many of the figures were based on real people.

When considering Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque , it is important to remember the dramatic nature of its forerunner. Our knowledge of the Folio Club gathering encourages us to read Poe's stories as the compositions of various personae and to regard Poe as author of the authors of the tales. W. H. Auden described Poe's writing as operatic, and Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque does indeed resemble an opera in which Poe's narrators walk on and off the stage. Thus, the narrator of Morella mutters, melodramatically, “Years—years, may pass away, but the memory of that epoch—never!” as he leaves the stage to make way for the narrator of Lionizing . “I am,” the latter remarks to the reader-audience by way of introduction, “that is to say, I was —a great man.”

Poe's gift for impersonating his narrators is remarkable, and like a great dramatist, he seemed to contain multitudes of characters. The comparison with the playwright is appropriate because the world of Poe's writing is a thoroughly theatrical one. In it the laws of “real life” (of psychological accuracy and consistency, for instance) do not apply, and in this context we can recall Poe's famous distinction between “Hamlet the dramatis persona” and “Hamlet the man.” In the Poe universe, bizarre and absurd incidents occur on a regular basis, the dialogue and the settings are distinctly stagy, and everything is hyperbolic. As the above quotations from Morella and Lionizing suggest, it is also a world in which tragedy can be quickly followed by comedy.

And here we might recall that Poe was the son of two itinerant actors. It is particularly interesting to note that Poe's beloved mother, Eliza, was renowned for her ability to play an enormous range of tragic and comic roles, often in the same theatrical season. Her son seems to have inherited this gift as, in his writings, he effortlessly swaps a suit of sables for motley attire. At times, as in The Visionary (later called The Assignation ), which contains elements of tragedy, parody, and self-parody, Poe wore both costumes at the same time. And this in turn may help us understand the appeal of Gothic literature for Poe, because it is a form of writing in which comedy intensifies the horror by setting it in relief. Those who have adapted Poe's tales for the cinema have appreciated the humorous elements of the Gothic, as their films are at once terrifying and hilarious.

Drama and theatricality are in fact everywhere in Poe's writing. As a young poet, he effortlessly mimicked the styles of writers such as Byron; as a reviewer he convincingly adopted the tone of the authoritative critic. Throughout his works he seems to entertain and juggle ideas rather than to offer them as articles of faith, and the idea of literary performance is central to his authorship. Poe is a writer-performer whose productions can be compared to virtuoso literary displays. As readers we are like members of a theater audience who are by turns enthralled, horrified, and dazzled, and when the performance is over we applaud Poe's artistry.

An appreciation of the theatrical nature of Poe's work has important consequences for criticism. If we view Poe's writing as fundamentally dramatic, it becomes impossible to discover Poe's individual voice in the universe of voices that is his work or to analyze it from the point of view of his authorial intentions. It also becomes essential to judge the work's style and content in terms of its dramatic appropriateness: when Poe's writing is weak and verbose, for example, this may be the appropriate style for a particular narrator.

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket

The only full-length novel that Poe would write, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket ( 1838 ), was begun on the suggestion of a publisher to whom he had unsuccessfully offered Tales of the Folio Club . Its first two installments appeared in the Southern Literary Messenger , and it came out in book form in 1838 . In choosing to write a sensational sea adventure—the plot includes, among other things, a mutiny, a shipwreck, a famine, and a massacre—Poe once again selected an extremely popular subject and form.

As a realistic chronicle of an utterly fantastic journey, the novel is similar to some of the stories Poe had written in the 1830s, such as MS. Found in a Bottle . Cast in the form of a first-person account of a real sea voyage and including journal entries, “factual” information, and scholarly footnotes, Pym is written with a sharp attention to significant detail that recalls the novels of the eighteenth-century author Daniel Defoe . This attention to detail, which can be found throughout Poe's fiction, confers a degree of verisimilitude on narrations that lack psychological realism. Poe's fictional works are not, in other words, realistic, but they have a reality of their own. Pym is also similar to a Defoe novel in that it is digressive and loosely structured. In contrast to Poe's short stories, it lacks a definite architecture and fails to create a unified impression or effect. Curiously enough, this is precisely what makes it such a hypnotic book. Pym's journey, like that of Karl Rossman in Franz Kafka 's Amerika ( 1927 ), is imbued with a vague sense of horror.

Pym also contains a preface, reminiscent of Defoe, in which the narrator claims that the book is a real account of a voyage although its first installments in the Southern Literary Messenger had appeared under the name of the short-story writer, “Mr Poe.” Few reviewers were taken in by this typical Poe hoax, and the novel was generally reviewed with varying degrees of enthusiasm, as a work of fiction. Until around the 1960s, critics tended to agree with Poe's own dismissive estimation of his “very silly” novel. Since then, however, it has received much better press and has inspired a variety of readings that range from the autobiographical to the allegorical. Like many of Poe's works, it is Pym 's ambiguity and indefiniteness that make it so suggestive. These qualities are perfectly embodied in the novel's famous last line. As the eponymous hero's boat heads toward a cataract, a shrouded human figure suddenly appears, “And the hue of the figure was of the perfect whiteness of the snow.” At about the same time Poe also wrote two other works, both unfinished, that can be briefly mentioned here. The Journal of Julius Rodman , a Pym -like account of an expedition across the Rocky Mountains, appeared in Gentleman's Magazine in 1840 . Five years previously the Southern Literary Messenger had published scenes from Politian , a blank verse tragedy set in Renaissance Italy that would later be included in The Raven and Other Poems ( 1845 ).

Poe's Criticism

Throughout his life Poe wrote a great deal of literary journalism and worked in an editorial capacity for a variety of newspapers. It was also one of his great ambitions to edit his own magazine. As a critic he was outspoken, vitriolic, and fearless. He highlighted the technical limitations of the books he reviewed, accused several authors (most famously Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ) of plagiarism, and took great delight in attacking the New England literary establishment.

Poe was not simply motivated by a disinterested concern for the health of letters; he was also desperately trying to carve his way to literary fame. That is why his criticism tended to be as sensational as his short-story writing: controversy was the equivalent of the Gothic and grotesque effects of his fiction. Without money or regular employment, Poe had to achieve celebrity status in order to survive in the literary marketplace, and if he could not be famous then he would be notorious. He did everything he could to keep his name before the public, even going to the extent of anonymously reviewing his own works.

Poe also used the pages of the popular press to fashion and present an image of himself as a man of immense erudition. In his articles, as in his short stories, he included countless quotations and phrases from various languages; he also made a great exhibition of his learning. Poe's “Marginalia,” published in newspapers during the 1840s, consists of comments and meditations that he claimed to have scribbled in the margins of the books in his library. “I sought relief,” he commented, like a latter-day Renaissance connoisseur of fine literature, “from ennui in dipping here and there at random among the volumes of my library.” The reality was quite different, however. Poe wrote the pieces as fillers for newspapers when they were short of copy, and the sad fact of the matter was that he could never afford to assemble an extensive library of his own.

Poe's most important contributions to literary criticism were his theories concerning the short story and poetry. It has been suggested that his comments on the short story, which were scattered throughout reviews of books such as Nathaniel Hawthorne 's Twice-Told Tales ( 1837 ), helped establish the genre in its modern form. Poe's theory can be briefly summarized. He was concerned above all with the effect of his tale on the reader. This effect should, he thought, be single and unified. When readers finished the story they ought be left with a totality of impression, and every element of the story—character, style, tone, plot, and so on—should contribute to that impression. Stories too long to be read at a single sitting could not, in Poe's view, achieve such powerful and unified effects—hence the brevity of his own productions. Poe also advocated the Aristotelian unities of place, time, and action and put special emphasis on the opening and conclusion of his tales. In addition, he encouraged authors to concentrate exclusively on powerful emotional and aesthetic effects—the aim of fiction, he suggested, was not a didactic one. Finally, instead of providing the reader with a transparent upper current of meaning, he thought that the meaning of a tale should be indefinite and ambiguous.

Obviously, such ideas help us understand Poe's own short stories. The Tell-Tale Heart and The Masque of the Red Death , for example, exhibit most of the above-mentioned characteristics. The theories of poetry that Poe adumbrated in book reviews and in lectures such as The Poetic Principle ( 1849 ) also help us understand his verse. In Poe's criticism there is a sense in which he was justifying his own practice as a creative writer and also attempting to create the kind of critical atmosphere in which his work would be favorably judged. Other writers, such as T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound , have also found this to be an effective strategy for achieving literary success. More broadly, it can be suggested that writing such as Poe's that lacks a definite content and an unambiguous message requires a theory in order to, as it were, support it and make it intelligible to the reader.

Poe's statements about poetry are similar to his pronouncements on the short story. Thus, in a review of Longfellow's Hyperion, A Romance ( 1839 ), he criticized its lack of a definite design and unified effect. Later, when commenting on the same author's Ballads and Other Poems ( 1841 ), he complained of Longfellow's didacticism and his failure to appreciate that the aim of poetry was not to instruct readers but to give them access to the world of supernal beauty. These ideas were expressed in a more theoretical form in The Poetic Principle , in which Poe criticized what he referred to as “the heresy of the didactic” and famously defined poetry as “the Rhythmical Creation of Beauty.” These ideas proved to be extremely influential and were later adapted by “art-for-art's-sake” aesthetes such as Oscar Wilde and by symbolists such as Paul Valéry . It has also been suggested that Poe's emphasis on the words on the page, rather than on external considerations such as the writer's biography, make him an important precursor of the New Critics.

The Raven and Other Poems

Poe's most influential theoretical essay was probably “The Philosophy of Composition,” published in Graham's Magazine in 1846 . Before we turn to it, however, it is necessary to consider The Raven , the inception and writing of which the essay describes. The Raven , first published in the New York Evening Mirror in January 1845 , was an instant hit with the reading public. This allusion to pop music is apt because the immediate and enormous success of the poem has been accurately compared to that of a present-day song. On its publication, Poe became an overnight sensation, and thereafter he would always be associated with the poem. In a sense this association is unfortunate, because it obscures the fact that the poem, like many of Poe's short stories, is a dramatic production. The narrator, a young man mourning the death of his love Lenore, sits in his study musing “over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore”—a character and a setting typical of Poe. As well as being a dramatic poem, it is also an intensely theatrical one: the gloomy weather, the speaking bird, and props such as the purple curtain and the bust of Pallas could have been filched from the set of a Gothic drama. The young man's language, too, is distinctly stagy; at one point he remarks to the Raven: “ ‘Sir…or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore.’ ” The effect of such distinctly camp lines is complicated; you are not sure whether to laugh or scream. In the theater, and in the theatrical world of the poem, it is of course possible to do both.

Given the theatricality of the poem, it is fitting that Poe performed it, just as Dickens performed his novels, in public and private readings. During his recitations Poe once again proved that the theater was in his blood: he would dress in black, turn the lamps down low, and chant the poem in a melodious voice. The content of the poem is of course unrealistic; like a great drama, however, it creates its own vivid and convincing reality through its solemn rhymes and its stately rhythm.

Poe's raven has become as famous as those other birds of romanticism, Keats 's nightingale, Shelley 's skylark, and Coleridge's albatross. This is ironic because, in The Philosophy of Composition , he insisted that the poem was not a romantic one. The essay was written to demonstrate that, far from being a work of inspiration, the composition of The Raven proceeded with what he called “the precision and rigid consequence of a mathematical problem.” Along with metaphors drawn from mathematics, Poe typically (and revealingly) used images of acting to convey his detachment and self-consciousness during the writing of the poem.

Desiring to create a powerful effect of melancholy beauty that would appeal to both “the popular and the critical taste,” Poe tells us that he hit upon the saddest of all subjects: the death of a beautiful woman. This had, of course, been the subject of several of his earlier writings, such as the “marriage group” of stories in Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque . In order to make the effect of the poem intense and unified, he decided that it should be limited to around one hundred lines and that it would include a refrain composed of the single, sonorous word, Nevermore . In the remainder of the essay Poe, who might be compared here to a magician who enjoys explaining away his tricks, goes on to make numerous comments of a similar nature.

It has been suggested that The Philosophy of Composition was a typical Poe hoax, and it is highly unlikely that it is a veracious account of the actual writing of The Raven . This, however, is largely irrelevant since the essay's importance lies in the fact that it offered a novel theory of composition and a new conception of the poet. Poe was attempting to replace the idea of the inspired poet that had been established by the ancients and by contemporaries such as Coleridge with his notion of the cold and calculating author. Once again, Poe's idea proved to be extremely influential in the history of literature. It informs Valéry's conception of the poet as an extremely self-conscious artist and T. S. Eliot's idea of the impersonal author.

It is doubtful that Poe's theories would have exercised such a powerful influence had he not also embodied and dramatized them in his writings. Perhaps even more important, he also offered himself as an archetype of the kind of author he was describing. Poe presented himself, in other words, as the exemplar of the self-conscious poet, an original that poets such as Baudelaire copied.

The Raven was republished in Poe's most substantial and famous collection of verse, The Raven and Other Poems , in 1845 . The book, which was prefaced by a statement that typically succeeded in being at once self-effacing and arrogant, contained revised versions of earlier compositions such as Israfel and poems that had never previously appeared in book form. Also included in the collection were several poems that had appeared, or would later appear, in Poe's short stories. (This is a striking demonstration of the homogeneous nature of Poe's oeuvre.) The most famous of these poems are The Haunted Palace , a powerful atmospheric poem improvised by Roderick Usher, and The Conqueror Worm , written by the eponymous hero of Ligeia . In the latter, angels are in a theater watching humankind play out its meaningless “motley drama” in which there is “much of Madness and more of Sin / And horror the soul of the plot.” Suddenly, “a blood-red thing” comes onto the stage. The lights go out, the curtain comes down, and death (for it is he) holds illimitable dominion over all. In its Gothic style, its dark vision of the world, and its theatricality, the poem is characteristic of its author and indeed reads like a microcosm of his oeuvre. One obvious point that can be made in connection with the poems that appeared in Poe's short stories is that they are dramatic works (a comparison here might be made with Robert Browning's monologues). Yet again, Poe displays his great gifts as a mimic or actor, and once more we are alerted to the difficulties of reading his work in an autobiographical light.

Many of Poe's finest poems were written after the publication of The Raven and were collected in volume form posthumously. These include the onomatopoeic The Bells , the beautiful ballad Annabel Lee , and the musical masterpiece Ulalume . This last poem is perhaps the most perfect example of Poe's ability to create a mysterious and unearthly atmosphere through repetition, assonance, and the use of languorous, usually trisyllabic, words. While discussing the poem, Poe is reported to have remarked that he deliberately wrote verse that would be unintelligible to the many. Ulalume is certainly hard to understand, but like the rest of Poe's verse, its ambiguity heightens rather than diminishes its power.

Poe, the Detective Story, and Science Fiction

Between the publication of Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque in 1840 and his death in 1849 , Poe wrote numerous short stories. Among them are some of the most famous of all his writings, such as The Black Cat , The Tell-Tale Heart , The Cask of Amontillado , The Pit and the Pendulum , Hop-Frog , and The Masque of the Red Death . These stories have achieved the status of myths in the Western world; even those who have not read them know their plots. Because of the exigencies of space, and also because some of Poe's arabesque and grotesque productions have already been discussed, the focus here is on the stories that appeared in Tales ( 1845 ) and, in particular, on Poe's detective tales and science fiction. Although reviewers of Tales were, as usual, divided between those who described Poe as a great original and those who dismissed him as a showy and stylistically incompetent writer, the volume sold better than any of Poe's other publications.

Four detective stories (or “Tales of ratiocination,” as Poe called them) appeared in Tales : the prize-winning The Gold-Bug and three tales that featured the detective C. Auguste Dupin: The Purloined Letter , The Mystery of Marie Roget , and The Murders in the Rue Morgue . Although writers such as Voltaire, William Godwin , and Tobias Smollet had produced examples of what might be loosely termed crime fiction in the eighteenth century , it was these tales that established the modern short detective story as a definite and distinct form.

In The Murders in the Rue Morgue , the most famous and entertaining of Poe's detective stories, we immediately recognize the structure of the modern detective tale. A hideous and inexplicable crime is committed (the brutal murder of two women in a locked room in Paris), and all the evidence is placed before us. The police, who rely on cunning and instinct rather than rational method and imagination, are utterly baffled. Fortunately for them, an amateur genius, Dupin, is on hand to unravel the mystery. The tale (which in terms of its action is written backward) thus includes two stories: that of the crime and that of its solution and explanation by Dupin.

In creating Dupin, Poe invented the archetype of the modern detective. Among Dupin's descendents are Agatha Christie 's Hercule Poirot, G. K. Chesterton 's Father Brown, and of course Sir Arthur Conan Doyle 's Sherlock Holmes, who in one of Conan Doyle's stories actually discusses Dupin's merits. An eccentric and reclusive genius, Dupin is both a poetic visionary and a detached man of reason; he combines the attributes of the poet with those of the mathematician. In The Purloined Letter , where he unravels a mystery by identifying with the criminal, Dupin also displays an actor's power of empathy. He is, in other words, a glorified and aristocratic version of Poe. Poe also created the original of the detective's companion: a friend of average intelligence who narrates the tale and who acts, as it were, as the reader's representative within it. In The Murders in the Rue Morgue , the character is nameless; in later works by other authors he will be called Doctor Watson and Captain Hastings.

Poe is thus in large part responsible for one of the most popular and dominant forms of modern literature. After reading Poe, the French writers the Goncourt brothers believed that they had discovered “the literature of the twentieth century —love giving place to deductions…the interest of the story moved from the heart to the head…from the drama to the solution.” This prediction proved correct. Twentieth-century writers such as Jorge Luis Borges (who believed that Poe's ghost dictated detective stories to him) consciously imitated Poe, and the popularity and influence of the detective story has been, and still is, enormous. The broader point made by the Goncourt brothers concerning a literature of “the head” is also interesting. The detective story is essentially an intellectual exercise or game, and much of Poe's writing can be described in these terms. Perhaps it is this quality in his work that made it so popular and influential in the twentieth century .

The invention, or at the very least the foundation, of the modern detective story is surely Poe's greatest contribution to world literature. He has also been hailed as the father of modern science fiction. The extent to which Poe established the genre is, however, a matter of controversy. Those who have argued for his formative influence point to the futuristic, technological, and rationalistic elements of his work. It is perhaps better to approach the question through a consideration of Poe's influence, which was enormous. Poe's science fiction stories profoundly influenced later masters of the genre such as Jules Verne , H. G. Wells , and Isaac Asimov (who conflated the science fiction tale and the detective story). Among the Poe stories that have been classed as science fiction are Hans Phaall , the eponymous hero's account of his nineteen-day balloon journey to the moon, and the futuristic Mellonta Tauta . Two stories in Tales , The Colloquy of Monos and Una and The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion , have also been classified as science fiction tales.

Both are dialogues between disembodied spirits set sometime in the distant future. The dialogue form, which derives from ancients such as Lucian and Plato , was very popular in Poe's time among satirical writers such as Thomas Love Peacock, Giacomo Leopardi , and William Blake . Poe also used it for satirical purposes; in these dialogues he criticizes his age for, among other things, its exclusive belief in science. Poe's argument with science was in some respects a typically romantic one. Science and industrialization, it is suggested in The Colloquy , have given humans the false idea that they have dominion over nature and have devalued the poetic intellect.

Yet Poe went further than this conventional romantic position and challenged science's claims to objectivity and its emphasis on empiricism. So far as objectivity is concerned, reading hoax stories such as Hans Phaall leaves the impression that scientific explanations of the world are not unlike stories and that science itself may be a kind of fiction. Regarding the limitations of empiricism, Poe believed that the discovery of facts was not enough and that it is what is done with them that is important. It requires, Poe suggests, a visionary rather than a scientist to sort, connect, and shape them into theories. This visionary figure, who is both poet and mathematician, appears throughout Poe's writings. Sometimes he is Dupin, the great detective; at other times he is Poe, the theorist of poetic composition and the author of the scientific prose poem Eureka .

Poe evidently believed that Eureka , published in 1848 , was his greatest achievement: “I have no desire to live since I have done ‘Eureka,’ ” he wrote to his mother-in-law. “I could accomplish nothing more.” Indeed, he appears to have regarded it as nothing less than the solution to the secret of the universe. It is most unfortunate for humanity, therefore, that Eureka makes extremely dull reading and is very difficult to understand. One of the best attempts at a summary is contained in Kenneth Silverman 's ( 1991 ) excellent biography of Poe. Suffice it to say here that Eureka , subtitled as “Essay on the material and the spiritual universe” predicted, among other things, the annihilation and the rebirth of the universe.

Although Eureka has traditionally been regarded as a distinct work within the Poe canon, there are many connections between it and the rest of his oeuvre. Passages in short stories such as Mellonta Tauta prefigure some of its contents. In his preface to the book Poe described it as a poem rather than a “scientific” work. “I offer this Book of Truths,” he wrote, adapting Keats's famous line, “not in the character of a Truth-Teller, but for the Beauty that abounds in its Truth; constituting it True.”

The rather confused critical reception that Eureka received also made it a typical Poe production. Some reviewers read it as an elaborate hoax in the manner of Hans Phaall ; others considered it to be a prolix and labored satire of scientific discourse. Certain critics regarded it as a brilliant and sincere work of genius, yet it was also dismissed as arrant fudge. Such diverse and extreme reactions to Poe's work have already been noted; they testify to the fact that, whatever else his writing is, it is impossible to ignore.

Poe's Influence

When Poe died in Baltimore on 7 October 1849 from causes that are still the subject of debate, some commentators predicted that his works would be forgotten. They could not have been more wrong, as his books are currently read throughout the world and his influence on world literature has been extraordinary. With their consummate artistry, their self-consciousness, and their heavy atmosphere of decay, Poe's poems and tales (along with his literary persona and his theories) inspired Decadent and symbolist writers of the nineteenth century . Baudelaire, among whose earliest works were translations of Poe's stories, famously died with a copy of Poe's tales beside his bed. Mallarmé, Verlaine, Dowson, and Wilde also worshipped at the Poe shrine.

At the end of the nineteenth century , science fiction writers such as Verne and Wells and authors of detective stories such as Conan Doyle acknowledged their profound debt to Poe. It was Conan Doyle who remarked that Poe's tales “have been so pregnant with suggestion…that each is a root from which a whole literature has developed.” In the twentieth century Poe's influence was no less profound. His short stories were of immense importance to authors as diverse as Kafka, H. P. Lovecraft (who referred to his tales of horror as “Poe stories”), Vladimir Nabokov , and Stephen King. He has also had a powerful effect on every other branch of the arts. Painters such as René Magritte and Edmund Dulac were fascinated by him, and film directors such as Roger Corman and Alfred Hitchcock also took inspiration from his writings.

Poe continues to inspire and enchant people today. In the future he will no doubt attract as much hostile criticism as he has in the past, but he will survive because he will continue to be read. And despite all of the faults and all of the fudge in his writings, it is hard, in conclusion, to think of another American writer who has so drastically altered the landscape of the popular imagination or who has had such a powerful effect on his fellow artists.

Selected Works

- Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827)

- Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems (1829)

- Poems by Edgar A. Poe (1831)

- The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838)

- Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1840)

- The Raven and Other Poems (1845)

- Tales (1845)

- Eureka (1848)

- Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe (1969–1978)

- The Science Fiction of Edgar Allan Poe (1976)

- The Fall of the House of Usher and Other Writings (1986)

- Poetry, Tales, and Selected Essays (1996)

Further Reading

- Carlson, Eric W. , ed. The Recognition of Edgar Allan Poe: Selected Criticism since 1829 . Ann Arbor, Mich., 1966. Collection of all of the famous essays on Poe, including those by T. S. Eliot, W. H. Auden, and Walt Whitman.

- Carlson, Eric W. , ed. A Companion to Poe Studies . Westport, Conn., 1996. A comprehensive collection of modern appraisals of every aspect of Poe's life and work.

- Hayes, Kevin J. The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe . Cambridge, 2002. Excellent and wide-ranging collection of late-twentieth-century Poe scholarship.

- Hyneman, Esther F. Edgar Allan Poe: An Annotated Bibliography of Books and Articles in English, 1827–1973 . Boston, 1974.

- Silverman, Kenneth . Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance . New York, 1991. Its psychoanalytic explanations are sometimes unconvincing, but it is easily the best biography available.

- Walker, I. M. , ed. Edgar Allan Poe: The Critical Heritage . New York, 1986. Anthology of contemporary reviews of Poe's work.

Related Articles

- American Detective Fiction

- Popular Fiction

- The Short Story in America

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Literature. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 19 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|45.133.227.243]

- 45.133.227.243

Character limit 500 /500

- International

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

Edgar Allen Poe Biography | Edgar Allan

Subject: English

Age range: 14 - 18

Resource type: Lesson (complete)

Last updated

8 November 2021

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

This slide show is an introduction to Edgar Allan Poe’s life and work. This is a PowerPoint , and it is editable.

An excellent presentation to introduce your students to his life before you explore his short stories and poems.

Cover Slide Overview Themes and Symbols The Gothic Style The Raven (excerpt) Who was Edgar Allan Poe? Early Years Education Marriage to Virginia Clemm Virginia’s Death Poe’s Final Years

This presentation is editable, for your convenience. Image rich 12 PPT slide show.

For your convenience, this is an EDITABLE document. If you need to tweak the presentation to better suit the needs of your classroom, you will be able to edit this document!

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

Edgar Allan Poe

Jul 20, 2014

100 likes | 197 Views

Edgar Allan Poe. Hunter Smith 6 10-25-11. Edgar Allan Poe. http://www.eapoe.org/. Born on :January 19, 1809 Died on: December 7, 1849 . 5 Short Stories and 5 Poems. 5 POEMS Annabel Lee Alone A Dream W ithin a Dream The Valley of Unrest The Raven. 5 STORIES

Share Presentation

- sparknotes editors

- literature com

- shmoop editorial team

- www poestories com offline

- your theory

- red death symbolism

Presentation Transcript

Edgar Allan Poe Hunter Smith 6 10-25-11

Edgar Allan Poe http://www.eapoe.org/ Born on :January 19, 1809 Died on: December 7, 1849

5 Short Stories and 5 Poems 5 POEMS • Annabel Lee • Alone • A Dream Within a Dream • The Valley of Unrest • The Raven 5 STORIES • The Angel of the Odd • The Black Cat • The Masque of the Red Death • The Murders in the Rue Morgue • The Gold Bug

Biography of poe From the beginning of Poe’s life, he has always been a mysterious mad man. January 19, 1809 he was born in Boston, Massachusetts. There were four children. After the death of his parents, Poe was taken in by John and Frances Allan in Virginia. Edgar went to England with the Allan's in 1815. his first book was Tamerlane and other poems, published in 1827. He moved to Baltimore and published a second book in 1831. He married his cousin when she was but 13. After getting married the two ran to new york 1836, he published another book called the narrative of Gordon Pym.

Part 2 Their last place of residence, Fordham, Virginia had past away in 1847. Alcohol, he more frequently ingested made him have more erratic behavior. After a year, he went to get his “teenage-sweetheart” Elmira Royster.

Your theory on Poe’s Death The alcohol theory to me seems most accurate. In 1847, when Virginia died, he turned to alcohol. I feel Poe had to get some type of kidney failure or poisoning. For me the alcohol theory is best.

Annabel lee • Annabel Lee, a love affair. Poe wrote the poem to show his love for the “fair maiden” to show what love they had shared and what feeling he had when she had past. • A lively affair this poem is, a woman with Poe “in this kingdom by the sea”. They loved with a passion to be separated not. Poe's rage when she died, and subtly when she was living. Using the moon as a metaphor of her beauty. He uses insanity as well as talented poetic skills to bring out what him and his love had shared.

Conclusion (5+ sentences) Poe is known to be the father of horror stories from his demented and crudeness. I make connections with his stories because of his depressive nature and sorrowful writing. He is and artist with words and he speaks not only to my ears, but to my soul. Many not understanding Poe’s meaning, but also he had issues with his life. Not many understand what he is meaning.

Finish paragraphs on your favorite story • In lively detail he shares how she died, quoting “That the wind came out of a cloud, chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.” He explains what he saw, what he felt. He tells how the kinsmen took her away and put her corpse in a tomb. Poe left with sorrowful thought of his passing maiden. • Over all I believe the poem was for his love, for what his beloved and himself had for each other.

Works Cited • Robert Giordano “Poe Stories” 10/31/11 <http://www.poestories.com/offline.php>. • C.D. Merriman for JalicInc “Edgar Allen Poe” 10/31/11<http://www.online-literature.com/poe/>. • The Edgar Allen Poe society of Baltimore “Mystery death of Edgar Allen Poe” 10/31/11 <http://www.eapoe.org/geninfo/poedeath.htm>. • SparkNotes Editors. “SparkNote on Poe’s Short Stories.” (2002.) (31 Oct. 2011.) • <http://www.sparknotes.com/lit/poestories/section10.rhtml>. • Shmoop Editorial Team. "The Masque of the Red Death Symbolism, Imagery & Allegory." (11 Nov. 2008.) ( 2 Nov. 2011.) • <http://www.shmoop.com/masque-of-red-death/symbolism-imagery.html>.

- More by User

Edgar Allan Poe. 1809-1849. His Family and Tragic Life. Born in Boston The son of traveling actors Tragic and unhappy life. Tragic and Unhappy Life. Mother died (of tuberculosis), father deserted him at the age of two

401 views • 15 slides

EDGAR ALLAN POE

EDGAR ALLAN POE. By: Abbi Gregory and Madisen Pierce ELAH Mrs. Serrato. Timeline of Poe’s life. Elements of Style.

825 views • 5 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. “The Fall of the House of Usher”. Elements of the Gothic. Gothic literature takes its themes of terror, darkness from Gothic architecture. Gothic architecture is a style of building that was popular in the Middle Ages, from about the twelfth to the fifteenth century.

559 views • 23 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. „ All religion, my friend , is simply evolved out of fraud , fear , greed , imagination and poetry .“. Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling, By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

489 views • 11 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. Jake O melian 3 11-15-11. URL of Poe picture. Edgar Allan Poe. Born: 1809 Died: 1849. 5 Short Stories and 5 Poems. 5 STORIES Angel of the Odd The Balloon H oax The Black C at Hop-Frog Murders in the Rue M orgue. 5 POEMS Alone The Bells The City in the Sea

359 views • 10 slides

Edgar Allan Poe . Man of Mystery. Poe was born in 1809. His mother left his father when Poe was a baby due to Poe’s father’s drinking problem. When his mother died (Poe was only 3 yrs old), he was practically left an orphan. Relatives took him in, though they never formally adopted him.

427 views • 10 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. Anna Selles. Biography. Edgar Allan Poe was born January 19, 1809 in Boston Massachusetts Son of actors Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins and David Poe His father deserted the family soon after he was born and his mother died a year later

1.06k views • 25 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. Rebekka Quenrud Period .4. 10/25/11. Edgar Allan Poe. http://poestories.com/view.php?photo=42bf361288f88. Born on : January 19, 1809 Died on: November 17, 1875. 5 Short Stories and 5 Poems. 5 POEMS

208 views • 10 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. Dates to Remember. Tuberculosis (TB). Tuberculosis (TB) is an infection, primarily in the lungs. TB can remain in an inactive (dormant) state for years without causing symptoms or spreading to other people.

362 views • 24 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. Jordan Weinberg Marshauna Hinton. Poe’s Childhood. Born January 19, 1809 in Boston, MA His parents died when he was two He was adopted into the wealthy Allan Family Poe was sent to one of the best boarding schools the family could afford

175 views • 6 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. Poe. One of America’s first prominent story writers Inventor of the detective story Champion of the Gothic story tradition Supernatural occurrences Magical settings Evil, beauty, and love are all extreme Trend setter for horror stories for the next three centuries. .

259 views • 11 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. “The Father of the Short Story”. Family Background. Born in Boston in 1809 Father abandoned the fam then died of alcoholism and mother died when Poe was 2 John and Francis Allan adopted him Mrs. Allan loved him, but his relationship with Mr. Allan was strained.

349 views • 8 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. The Cask of Amantillado. Edgar Allan Poe. b. Boston, Mass., 1810 ·mom died 1811, taken in by John Allan · some schooling in Britain, U. of Virginia · gambling debts = disowned by Allan. ·1827 join army, used common name · published privately while in army ·

455 views • 27 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. an author to know. When did he live?. 1809 - 1849. Where did he live?. born in Boston, Massachusetts lived in Baltimore Philadelphia New York. Family Life. both parents died by the time he was 2 years old raised by foster parents, Frances and John Allan

227 views • 12 slides

E. Edgar Allan Poe. Edgar Allan Poe. Poe was born on January 19, 1809 in Boston, Massachusetts. He was the son of Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins Poe and actor David Poe, Jr. His parents died when he was young. He was taken in by John and Frances Allan. More Information.

418 views • 10 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. 1809-1849. His Life. “The want of parental affection,” wrote Poe, “has been the heaviest of my trials. Father was a drunk He abandoned his mother who died son after, leaving Edgar an orphan before the age of three. He was taken in by John and Frances Allan.

194 views • 8 slides

EDGAR ALLAN POE. The Tormented Life of a Disturbed Genius. The Life of Edgar Allan Poe. Born in Boston in 1809 Edgar was the second of three children Both parents were actors Actors were looked down upon by society Despite that, his mother was well known and respected.

475 views • 28 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. 1809-1849. Early life. Edgar Poe was born in Boston on January 19, 1809, to David and Elizabeth Poe. Elizabeth died in 1811 shortly after separating from David and taking the three children David, Edgar, and Rosalie, with her. Early life. The three children were separated

371 views • 22 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. ( January 19 , 1809 – October 7 , 1849 ). Who is Poe?. Poe was an American writer. He wrote short stories and poems. He was an editor and a critic. Biography. BIRTHPLACE- Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston, Massachusetts.

240 views • 9 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. 1809-1849. His Family and Tragic Life. Born in Boston The son of traveling actors Tragic and unhappy life. Tragic and Unhappy Life. Mother died, father deserted him at the age of two adopted by Mr. and Mrs. John Allan constant disagreements with his step-father.

253 views • 15 slides

Edgar Allan Poe. 1809-1849. Born in Boston to David Poe, an alcoholic traveling actor, and Elizabeth Arnold, also an actress David deserted his wife and child when Edgar was a baby His mother died while on tour in Richmond, leaving Edgar an orphan before his 3 rd birthday.

293 views • 8 slides

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology