We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Critical thinking

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

10 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station36.cebu on November 4, 2022

Robert H. Ennis (1996), Critical Thinking

- Published: February 2000

- Volume 14 , pages 48–51, ( 2000 )

Cite this article

- Alec Fisher 1

1713 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom

Alec Fisher

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Fisher, A. Robert H. Ennis (1996), Critical Thinking. Argumentation 14 , 48–51 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007850227823

Download citation

Issue Date : February 2000

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007850227823

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Critical Thinking Dispositions: Their Nature and Assessability

- Robert H. Ennis

Developed By

- Français (Canada)

Critical thinking

By robert hugh ennis.

- ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ 5.00 ·

- 18 Want to read

- 0 Currently reading

- 1 Have read

Preview Book

My Reading Lists:

Use this Work

Create a new list

My book notes.

My private notes about this edition:

Check nearby libraries

- Library.link

Buy this book

This edition doesn't have a description yet. Can you add one ?

Previews available in: English

Showing 1 featured edition. View all 1 editions?

Add another edition?

Book Details

Published in.

Upper Saddle River, NJ

Edition Notes

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Classifications

The physical object, community reviews (0).

- Created April 1, 2008

- 12 revisions

Wikipedia citation

Copy and paste this code into your Wikipedia page. Need help ?

- Politics & Social Sciences

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Critical Thinking 1st Edition

Unique in perspective, this book provides a general approach to critical thinking skills that can be applied to all disciplines. With an emphasis on writing, as well as on deciding what to believe or do, it offers extended discussions, examples, and practice of such skills as observing, making judgments, planning experiments, and developing ideas and alternatives.

- ISBN-10 0133747115

- ISBN-13 978-0133747119

- Edition 1st

- Publisher Pearson

- Publication date September 28, 1995

- Language English

- Dimensions 7.05 x 1.15 x 8.95 inches

- Print length 432 pages

- See all details

Editorial Reviews

From the publisher, from the back cover, product details.

- Publisher : Pearson; 1st edition (September 28, 1995)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 432 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0133747115

- ISBN-13 : 978-0133747119

- Item Weight : 1.28 pounds

- Dimensions : 7.05 x 1.15 x 8.95 inches

- #7,813 in Philosophy (Books)

- #19,509 in Core

About the author

Robert hugh ennis.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Table of Contents

- New in this Archive

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Back to Entry

- Entry Contents

- Entry Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Supplement to Critical Thinking

How can one assess, for purposes of instruction or research, the degree to which a person possesses the dispositions, skills and knowledge of a critical thinker?

In psychometrics, assessment instruments are judged according to their validity and reliability.

Roughly speaking, an instrument is valid if it measures accurately what it purports to measure, given standard conditions. More precisely, the degree of validity is “the degree to which evidence and theory support the interpretations of test scores for proposed uses of tests” (American Educational Research Association 2014: 11). In other words, a test is not valid or invalid in itself. Rather, validity is a property of an interpretation of a given score on a given test for a specified use. Determining the degree of validity of such an interpretation requires collection and integration of the relevant evidence, which may be based on test content, test takers’ response processes, a test’s internal structure, relationship of test scores to other variables, and consequences of the interpretation (American Educational Research Association 2014: 13–21). Criterion-related evidence consists of correlations between scores on the test and performance on another test of the same construct; its weight depends on how well supported is the assumption that the other test can be used as a criterion. Content-related evidence is evidence that the test covers the full range of abilities that it claims to test. Construct-related evidence is evidence that a correct answer reflects good performance of the kind being measured and an incorrect answer reflects poor performance.

An instrument is reliable if it consistently produces the same result, whether across different forms of the same test (parallel-forms reliability), across different items (internal consistency), across different administrations to the same person (test-retest reliability), or across ratings of the same answer by different people (inter-rater reliability). Internal consistency should be expected only if the instrument purports to measure a single undifferentiated construct, and thus should not be expected of a test that measures a suite of critical thinking dispositions or critical thinking abilities, assuming that some people are better in some of the respects measured than in others (for example, very willing to inquire but rather closed-minded). Otherwise, reliability is a necessary but not a sufficient condition of validity; a standard example of a reliable instrument that is not valid is a bathroom scale that consistently under-reports a person’s weight.

Assessing dispositions is difficult if one uses a multiple-choice format with known adverse consequences of a low score. It is pretty easy to tell what answer to the question “How open-minded are you?” will get the highest score and to give that answer, even if one knows that the answer is incorrect. If an item probes less directly for a critical thinking disposition, for example by asking how often the test taker pays close attention to views with which the test taker disagrees, the answer may differ from reality because of self-deception or simple lack of awareness of one’s personal thinking style, and its interpretation is problematic, even if factor analysis enables one to identify a distinct factor measured by a group of questions that includes this one (Ennis 1996). Nevertheless, Facione, Sánchez, and Facione (1994) used this approach to develop the California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory (CCTDI). They began with 225 statements expressive of a disposition towards or away from critical thinking (using the long list of dispositions in Facione 1990a), validated the statements with talk-aloud and conversational strategies in focus groups to determine whether people in the target population understood the items in the way intended, administered a pilot version of the test with 150 items, and eliminated items that failed to discriminate among test takers or were inversely correlated with overall results or added little refinement to overall scores (Facione 2000). They used item analysis and factor analysis to group the measured dispositions into seven broad constructs: open-mindedness, analyticity, cognitive maturity, truth-seeking, systematicity, inquisitiveness, and self-confidence (Facione, Sánchez, and Facione 1994). The resulting test consists of 75 agree-disagree statements and takes 20 minutes to administer. A repeated disturbing finding is that North American students taking the test tend to score low on the truth-seeking sub-scale (on which a low score results from agreeing to such statements as the following: “To get people to agree with me I would give any reason that worked”. “Everyone always argues from their own self-interest, including me”. “If there are four reasons in favor and one against, I’ll go with the four”.) Development of the CCTDI made it possible to test whether good critical thinking abilities and good critical thinking dispositions go together, in which case it might be enough to teach one without the other. Facione (2000) reports that administration of the CCTDI and the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) to almost 8,000 post-secondary students in the United States revealed a statistically significant but weak correlation between total scores on the two tests, and also between paired sub-scores from the two tests. The implication is that both abilities and dispositions need to be taught, that one cannot expect improvement in one to bring with it improvement in the other.

A more direct way of assessing critical thinking dispositions would be to see what people do when put in a situation where the dispositions would reveal themselves. Ennis (1996) reports promising initial work with guided open-ended opportunities to give evidence of dispositions, but no standardized test seems to have emerged from this work. There are however standardized aspect-specific tests of critical thinking dispositions. The Critical Problem Solving Scale (Berman et al. 2001: 518) takes as a measure of the disposition to suspend judgment the number of distinct good aspects attributed to an option judged to be the worst among those generated by the test taker. Stanovich, West and Toplak (2011: 800–810) list tests developed by cognitive psychologists of the following dispositions: resistance to miserly information processing, resistance to myside thinking, absence of irrelevant context effects in decision-making, actively open-minded thinking, valuing reason and truth, tendency to seek information, objective reasoning style, tendency to seek consistency, sense of self-efficacy, prudent discounting of the future, self-control skills, and emotional regulation.

It is easier to measure critical thinking skills or abilities than to measure dispositions. The following eight currently available standardized tests purport to measure them: the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (Watson & Glaser 1980a, 1980b, 1994), the Cornell Critical Thinking Tests Level X and Level Z (Ennis & Millman 1971; Ennis, Millman, & Tomko 1985, 2005), the Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test (Ennis & Weir 1985), the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (Facione 1990b, 1992), the Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment (Halpern 2016), the Critical Thinking Assessment Test (Center for Assessment & Improvement of Learning 2017), the Collegiate Learning Assessment (Council for Aid to Education 2017), the HEIghten Critical Thinking Assessment (https://territorium.com/heighten/), and a suite of critical thinking assessments for different groups and purposes offered by Insight Assessment (https://www.insightassessment.com/products). The Critical Thinking Assessment Test (CAT) is unique among them in being designed for use by college faculty to help them improve their development of students’ critical thinking skills (Haynes et al. 2015; Haynes & Stein 2021). Also, for some years the United Kingdom body OCR (Oxford Cambridge and RSA Examinations) awarded AS and A Level certificates in critical thinking on the basis of an examination (OCR 2011). Many of these standardized tests have received scholarly evaluations at the hands of, among others, Ennis (1958), McPeck (1981), Norris and Ennis (1989), Fisher and Scriven (1997), Possin (2008, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c, 2014, 2020) and Hatcher and Possin (2021). Their evaluations provide a useful set of criteria that such tests ideally should meet, as does the description by Ennis (1984) of problems in testing for competence in critical thinking: the soundness of multiple-choice items, the clarity and soundness of instructions to test takers, the information and mental processing used in selecting an answer to a multiple-choice item, the role of background beliefs and ideological commitments in selecting an answer to a multiple-choice item, the tenability of a test’s underlying conception of critical thinking and its component abilities, the set of abilities that the test manual claims are covered by the test, the extent to which the test actually covers these abilities, the appropriateness of the weighting given to various abilities in the scoring system, the accuracy and intellectual honesty of the test manual, the interest of the test to the target population of test takers, the scope for guessing, the scope for choosing a keyed answer by being test-wise, precautions against cheating in the administration of the test, clarity and soundness of materials for training essay graders, inter-rater reliability in grading essays, and clarity and soundness of advance guidance to test takers on what is required in an essay. Rear (2019) has challenged the use of standardized tests of critical thinking as a way to measure educational outcomes, on the grounds that they (1) fail to take into account disputes about conceptions of critical thinking, (2) are not completely valid or reliable, and (3) fail to evaluate skills used in real academic tasks. He proposes instead assessments based on discipline-specific content.

There are also aspect-specific standardized tests of critical thinking abilities. Stanovich, West and Toplak (2011: 800–810) list tests of probabilistic reasoning, insights into qualitative decision theory, knowledge of scientific reasoning, knowledge of rules of logical consistency and validity, and economic thinking. They also list instruments that probe for irrational thinking, such as superstitious thinking, belief in the superiority of intuition, over-reliance on folk wisdom and folk psychology, belief in “special” expertise, financial misconceptions, overestimation of one’s introspective powers, dysfunctional beliefs, and a notion of self that encourages egocentric processing. They regard these tests along with the previously mentioned tests of critical thinking dispositions as the building blocks for a comprehensive test of rationality, whose development (they write) may be logistically difficult and would require millions of dollars.

A superb example of assessment of an aspect of critical thinking ability is the Test on Appraising Observations (Norris & King 1983, 1985, 1990a, 1990b), which was designed for classroom administration to senior high school students. The test focuses entirely on the ability to appraise observation statements and in particular on the ability to determine in a specified context which of two statements there is more reason to believe. According to the test manual (Norris & King 1985, 1990b), a person’s score on the multiple-choice version of the test, which is the number of items that are answered correctly, can justifiably be given either a criterion-referenced or a norm-referenced interpretation.

On a criterion-referenced interpretation, those who do well on the test have a firm grasp of the principles for appraising observation statements, and those who do poorly have a weak grasp of them. This interpretation can be justified by the content of the test and the way it was developed, which incorporated a method of controlling for background beliefs articulated and defended by Norris (1985). Norris and King synthesized from judicial practice, psychological research and common-sense psychology 31 principles for appraising observation statements, in the form of empirical generalizations about tendencies, such as the principle that observation statements tend to be more believable than inferences based on them (Norris & King 1984). They constructed items in which exactly one of the 31 principles determined which of two statements was more believable. Using a carefully constructed protocol, they interviewed about 100 students who responded to these items in order to determine the thinking that led them to choose the answers they did (Norris & King 1984). In several iterations of the test, they adjusted items so that selection of the correct answer generally reflected good thinking and selection of an incorrect answer reflected poor thinking. Thus they have good evidence that good performance on the test is due to good thinking about observation statements and that poor performance is due to poor thinking about observation statements. Collectively, the 50 items on the final version of the test require application of 29 of the 31 principles for appraising observation statements, with 13 principles tested by one item, 12 by two items, three by three items, and one by four items. Thus there is comprehensive coverage of the principles for appraising observation statements. Fisher and Scriven (1997: 135–136) judge the items to be well worked and sound, with one exception. The test is clearly written at a grade 6 reading level, meaning that poor performance cannot be attributed to difficulties in reading comprehension by the intended adolescent test takers. The stories that frame the items are realistic, and are engaging enough to stimulate test takers’ interest. Thus the most plausible explanation of a given score on the test is that it reflects roughly the degree to which the test taker can apply principles for appraising observations in real situations. In other words, there is good justification of the proposed interpretation that those who do well on the test have a firm grasp of the principles for appraising observation statements and those who do poorly have a weak grasp of them.

To get norms for performance on the test, Norris and King arranged for seven groups of high school students in different types of communities and with different levels of academic ability to take the test. The test manual includes percentiles, means, and standard deviations for each of these seven groups. These norms allow teachers to compare the performance of their class on the test to that of a similar group of students.

Copyright © 2022 by David Hitchcock < hitchckd @ mcmaster . ca >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2023 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

- Advanced Search

- All new items

- Journal articles

- Manuscripts

- All Categories

- Metaphysics and Epistemology

- Epistemology

- Metaphilosophy

- Metaphysics

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Religion

- Value Theory

- Applied Ethics

- Meta-Ethics

- Normative Ethics

- Philosophy of Gender, Race, and Sexuality

- Philosophy of Law

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Value Theory, Miscellaneous

- Science, Logic, and Mathematics

- Logic and Philosophy of Logic

- Philosophy of Biology

- Philosophy of Cognitive Science

- Philosophy of Computing and Information

- Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Physical Science

- Philosophy of Social Science

- Philosophy of Probability

- General Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Science, Misc

- History of Western Philosophy

- Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy

- Medieval and Renaissance Philosophy

- 17th/18th Century Philosophy

- 19th Century Philosophy

- 20th Century Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy, Misc

- Philosophical Traditions

- African/Africana Philosophy

- Asian Philosophy

- Continental Philosophy

- European Philosophy

- Philosophy of the Americas

- Philosophical Traditions, Miscellaneous

- Philosophy, Misc

- Philosophy, Introductions and Anthologies

- Philosophy, General Works

- Teaching Philosophy

- Philosophy, Miscellaneous

- Other Academic Areas

- Natural Sciences

- Social Sciences

- Cognitive Sciences

- Formal Sciences

- Arts and Humanities

- Professional Areas

- Other Academic Areas, Misc

- Submit a book or article

- Upload a bibliography

- Personal page tracking

- Archives we track

- Information for publishers

- Introduction

- Submitting to PhilPapers

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Subscriptions

- Editor's Guide

- The Categorization Project

- For Publishers

- For Archive Admins

- PhilPapers Surveys

- Bargain Finder

- About PhilPapers

- Create an account

Critical Thinking

Reprint years, philarchive, external links.

- From the Publisher via CrossRef (no proxy)

- pdcnet.org (no proxy)

Through your library

- Sign in / register and customize your OpenURL resolver

- Configure custom resolver

Similar books and articles

Citations of this work, references found in this work.

No references found.

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

Russia’s limits on critical thinking are hitting its academic performance

Stricter political and administrative controls on what can be said have led to the creation of a pioneering ‘free university’, say katarzyna kaczmarska and dmitry dubrovsky.

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

Recent months have seen heated debates in Russia about the limits of faculty and students’ rights to undertake public speaking and engage in political activism.

Lecturers at the prestigious Higher School of Economics (HSE), once considered Russia’s most liberal university, have spent the summer worrying that their criticisms of the political status quo might put an end to their teaching careers.

A master’s programme was apparently shut down when the university’s management realised that Yegor Zhukov – a prominent blogger and participant in the 2019 protests against fraudulent practices in the elections for the Moscow city parliament – was among the newly admitted cohort. He was also badly beaten just hours after he posted a video on YouTube explaining that he had been enrolled and then, less than two hours later, was crossed off a list of students admitted.

It has proved contentious for scholars to speak out in public and for students to engage in political activity at least since the 2019 protests. Zhukov was an undergraduate at the HSE when he was arrested following an unsanctioned opposition rally that summer. This led many fellow students, staff and alumni to express solidarity. However, though the management initially supported calls for Zhukov’s release, it later shifted to a policy seemingly designed to avoid future clashes with the state authorities.

In 2020, the university introduced new internal regulations requiring staff and students to refrain from using their university affiliations in public statements that could trigger “negative social reactions and/or have negative reputational consequences for the university”. Though these regulations are careful to emphasise that there are no restrictions on academics speaking out about their “research results” and matters of “professional competence”, keeping within the guidelines is likely to be difficult, particularly for those researching current social or political developments in Russia. This attempt to establish a boundary between “legitimate” academic research and “unacceptable” participation in public debate amounts to another way of silencing critically minded scholars.

After the journalist Svetlana Prokopyeva was found guilty in July of “justifying terrorism” when she dared to ask about the connection between the repressive political regime in Russia and a suicide bomb outside the Federal Security Service office in Arkhangelsk, several HSE employees produced a paper citing values such as “academic ethics” to delegitimise debate about terrorism and its causes. A few scholars responded by pointing out that such a stance could close down research into social phenomena such as terrorism, state terror, revolution and liberation movements.

The HSE has also decided not to extend the contracts of a number of academics for the coming academic year. Though the university’s management has defended its decision on grounds of efficiency and necessary restructuring, those adversely affected argue that the dismissals were motivated by an urge to get rid of those who were most outspoken and critical of the political system in Russia, including the abruptly amended constitution .

The British Association for Slavonic and East European Studies (BASEES) published a letter this July in which the president shared his unease “about the integrity of the process by which decisions over continuing employment and terminations of contracts are taken” and emphasised that these developments undermine the HSE’s position as a close partner for scholars and universities in the UK. And Russia’s University Solidarity trade union called for a protest (using a hashtag translating as “you can’t shut us up”) against measures to punish scholars and students for their outspokenness.

Then, in late August, a group of scholars, including those whose contracts at HSE have not been renewed, issued a manifesto announcing the establishment of Russia’s first Free University and stating that one of their main goals is to free lecturers from excessive administrative pressures (among which they mean to include the pressure not to speak out).

Among the group is Gasan Guseynov, whose social media post last year criticising abuses of the Russian language by journalists and politicians prompted HSE management to look into whether it “violated academic ethics in public speaking”. This led to a committee’s recommending that Guseynov make a public apology for the “deliberate dissemination of ill-considered and irresponsible statements that have caused damage to the university’s reputation”.

All of this took place against a background of Russian universities failing to achieve the planned leap in international rankings; more and more insecure employment contracts ; and legislation requiring that education in schools and universities should include not only knowledge and skills, but also spiritual and moral values.

A recent analysis of the obstacles to scientific progress in Russia concludes that research managers do not prioritise the creation of the kind of new scientific knowledge likely to be recognised by the international academic community. This study was authored by people close to Alexei Kudrin, who represents the liberal-leaning wing within the ruling elite.

What even this group fails to mention, however, is that the problem does not reside so much in management structures as in a political system that crushes creativity and punishes critical thinking and activism.

Katarzyna Kaczmarska is lecturer in politics and international relations at the University of Edinburgh . Dmitry Dubrovsky is an associate research fellow at the Centre for Independent Social Research in Russia.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login

Related articles

Is Russia’s 5-100 Project working?

Simon Baker weighs the evidence for the transformation of the country’s higher education system

Russian science reforms ‘ambitious but unrealistic’

Experts question whether new National Science Project will have wide impact beyond creating ‘a few islands of research excellence’

Russian curbs on foreigners show rise of science nationalism

Kremlin action follows US reluctance to work with China, and comes as Moscow moves closer to Beijing

You might also like

English universities report fewer overseas master’s enrolments

Early data suggest number of international students starting taught postgraduate courses is down 6 per cent, but some individual campuses hit much harder

Dutch universities to cut English-only undergraduate degrees

Universities Netherlands announces new measures to limit international student numbers, but needs politicians’ help to introduce quotas

Biden rolls out major new student debt forgiveness plan

After 2020 campaign promise, and Supreme Court rejection, president still sees winning hand in college debt relief

Labour tipped to ‘lean on’ research budget to boost growth

Shadow chancellor’s regional productivity agenda could be driven by devolving parts of R&D funding or creating new kinds of institutions, say experts

Featured jobs

Please enter at least 3 characters

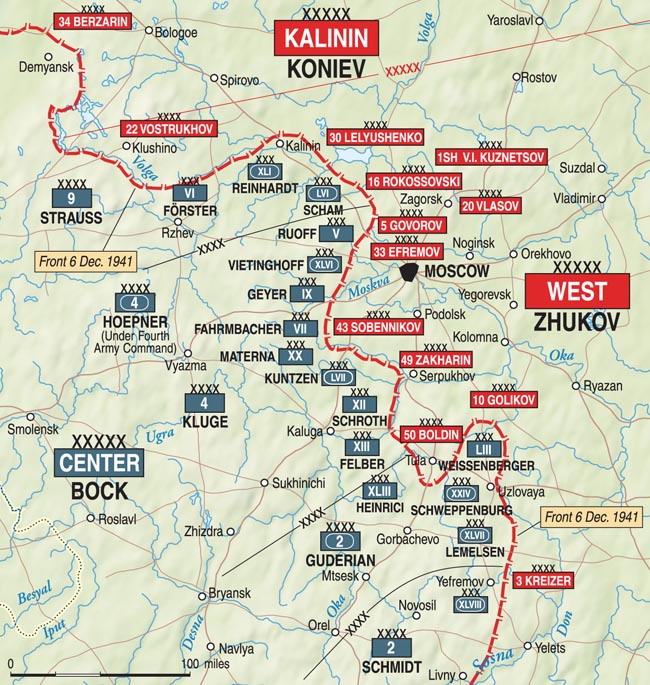

The Battle of Moscow: WWII’s First Critical Turning Point

When German armies invaded the USSR in 1941, Hitler thought victory would be quick and easy. It was neither.

This article appears in: Spring 2019

By Jeff Chrisman

Many consider the Battle of Moscow in late 1941 to be the first turning point of World War II on the Eastern Front . Some even consider the battle for Moscow as the only opportunity for the Germans to prevail in the East. By the middle of 1942, the Soviets had organized enough troops under arms that the Germans could not hope for anything better than a negotiated peace.

Even if the Soviet recapture of Stalingrad in 1942 had never happened and the Battle of Kursk in 1943 had been a German victory, Hitler still could not have won a total victory against the Soviets’ overwhelming numbers.

But, had the Germans been able to take Moscow, or isolated it very early, they might have dropped the Soviets to their knees and forced them to negotiate a cease-fire or perhaps even concede defeat.

After the war, German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring , commander of the Luftwaffe units assigned to Army Group Center, wrote: “The capture of Moscow would have been decisive in that the whole of European Russia would have been cut off from its Asiatic potential and the seizure of the vital economic centers of Leningrad, the Donets Basin, and the Maykop oil fields in 1942 would have been no insoluble task.” (Get a full view of the most ambitious military operation in the history of warfare inside our Operation Barbarossa special issue.)

Why Moscow Was So Important—To Everyone Except for Hitler

Moscow was the center of the Soviet empire. All government offices were there, and it was the main logistics hub and heart of communication and command for all the armed forces. Moscow was at the center of everything, and the Soviets would have been hard pressed without it. Fortunately for them, it never came to that, but it was close—very close.

On June 22, 1941, the German Army attacked the Soviet Union with three army groups on a Continent-wide front from the Baltic coast in northern Lithuania south some 900 miles to the Black Sea coast in southern Romania. German Army Group Center was situated between Army Group North and Army Group South and, at that time, was the strongest of the three. In the first four weeks of the war, Army Group Center surged eastward some 400 miles through Belorussia and then captured Smolensk, a regional administrative city in western Russia only 234 miles from Moscow.

At that point Hitler wasn’t really sure what to do next, but General Franz Halder, chief of staff of the Army High Command (OKH), and Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch, commander of the German Army, knew just what to do: take Moscow! However, Hitler, calling Moscow “merely a mark on a map,” demurred. Instead, he ordered Army Group Center (AGC) to send half of its armored forces, Panzer Group 2, south to help Army Group South (AGS) capture the Ukraine, and the other half of its armored forces, Panzer Group 3, north to help Army Group North (AGN) take Leningrad.

The leaders of AGC were aghast. Army Group commander Field Marshal Fedor von Bock and his armored commanders, General Heinz Guderian of Panzer Group 2 and General Hermann Hoth of Panzer Group 3, protested loudly.

All had envisioned Moscow as their ultimate goal from the beginning and were stunned to find that Hitler didn’t agree. They all lobbied Hitler at every chance, individually and in groups, but to no avail. Once Hitler had made up his mind about something, he seldom, if ever, changed it, and so it was this time as the panzer groups were sent on their divergent ways on August 23.

On September 6, Hitler released Directive #35 for the continuation of the war in the East: “In the sector of Army Group Center. Prepare an operation against Army Group Timoshenko (Soviet West Theater) as quickly as possible so that we can go on the offensive in the general direction of Vyazma and destroy the enemy located in the region east of Smolensk by a double envelopment by powerful panzer forces concentrated on the flanks.”

Still no mention of an attack on Moscow but at least it wasn’t precluded. AGC commander Bock and Army Chief of Staff Halder agreed that even though Moscow had not been mentioned, it was, in fact, the objective.

Ten days later, having received news of 2nd Panzer Army’s successful operations in Ukraine, Bock enlarged his army group’s mission. In addition to the encirclement east of Smolensk, Bock added another encirclement, this one in the area of Bryansk, to the south.

By the fourth week of September, all the operations on the flanks had run their course, and the armored units were returned to AGC command to begin realigning for the continuation of the attack eastward. Panzer Group 3’s attack to the north had been only marginally successful, and AGN never did capture Leningrad. But Panzer Group 2 became an integral part of the AGS’s swift capture of the Ukraine, destroying six Soviet armies and eliminating 665,000 enemy troops.

The 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies Mobilize

Up to this point, the Germans had been dominant; they had overrun or encircled nearly all the enemy they engaged. But the troops were becoming exhausted, and the equipment was badly in need of repair or replacement. Some of the panzer divisions did receive a few replacement tanks, but most other equipment was nearly worn out.

For the continuation of the attack, Army Group Center deployed a total of six armies—9th, 4th, and 2nd, as well as Panzer Groups 2, 3, and 4. All three panzer groups were the size of an army and would be renamed as panzer armies over the next three months, so for clarity here they will all be referred to as panzer armies. AGC had a total of 1,929,406 men in 49 infantry divisions, 14 panzer divisions, eight motorized divisions, and one cavalry division, with more than 1,000 tanks, 14,000 artillery pieces, and 1,390 combat aircraft.

AGC held a 450-mile-long north-south front about 200 miles west of Moscow. The 9th Army was deployed on the northern flank of the army group from Andreapol on the Daugava River northeast of Toropets, south to Berezhok on the Dnieper River 23 miles east of Smolensk.

The 3rd Panzer Army was deployed near the center of 9th Army, east of Velizh. South of 9th Army and in the center of the AGC front was 4th Army; its front ran south from Berezhok to Yekimovichi on the Desna River northeast of Roslavl.

The 4th Panzer Army was on the 4th Army’s southern flank; its front ran from Yekimovichi south along the Desna to near Zhukovka, while 2nd Army held the front south from Zhukovka to Pochep on the Sudost River southwest of Bryansk. The 2nd Panzer Army front ran south to the Army Group South front near Romny.

Facing the AGC attack and defending the western approaches to Moscow was the West Theater, commanded by Marshal Semen Timoshenko, composed of three Soviet fronts, a Soviet front being equivalent to a German army group. Combined, the three fronts had 1,250,000 men in 85 rifle divisions, eight cavalry divisions, four mechanized divisions, one tank division, and 14 tank brigades. Combined they had 7,600 artillery pieces, almost 1,000 tanks, and more than 360 aircraft.

On the northern flank, facing 9th Army and 3rd Panzer Army was the Soviets’ Western Front with six armies: 22nd, 29th, 30th, 19th, 16th, and 20th. The Reserve Front had two Armies in the front line: 24th and 43rd south of the Western Front, facing the German 4th Army and 4th Panzer Army, and four Armies: 31st, 49th, 32nd, and 33rd lined up behind the Western Front in reserve. The southern end of the Soviet line was held by the Bryansk Front with three Armies (50th, 3rd, and 13th) facing the German 2nd Army and 2nd Panzer Army.

At the southern end of the attack front, 2nd Panzer Army was the farthest from Moscow at just over 300 miles, and it began the attack on the Soviet capital, Operation Typhoon, on September 30, two days earlier than the rest of the army group. In the center of the 2nd Panzer Army attack, XXIV Panzer Corps, at Glukhov, stepped off at first light on the 30th. All of the German panzer corps started the war as motorized corps, but all were eventually renamed as panzer corps, so for clarity here all will be referred to as panzer corps.

Exploding Dogs?

The corps’ lead element, 3rd Panzer Division, quickly became the first unit to encounter two of the Soviets’ new weapons of war. The division’s tanks were maneuvering across an open field when several dogs were spotted running loose. Closer inspection through field glasses revealed something strange; all the dogs had small sticks sticking up from their backs. One of the nearby dogs was shot and exploded! Exploding dogs?

The Russians had strapped TNT to the dogs’ backs with triggers attached to the sticks and had trained the dogs to run underneath a tank to find their food. When they did, the sticks were pushed back and tripped the explosives. The tankers had no choice but to shoot all the dogs.

As the dogs were being dealt with, their Russian handlers fled and called in another new Russian innovation. Suddenly, an eerie howling sound filled the air and the entire field erupted in a series of explosions—Katyusha rockets. This was Russia’s first use of the multiple-launch rockets, which were launched from racks on the back of an ordinary truck. Each truck could launch as many as 16 rockets at a time, and each rocket delivered 11 pounds of high explosive.

The “mine dogs” had little future as word of their dangerous mission quickly spread. The Katyusha rockets, on the other hand, became quite useful, and their numbers multiplied rapidly. The Germans even deployed their own multiple rocket system, the Panzerwerfer, a year and a half later. The first day of Operation Typhoon had demonstrated two innovative new ways for the Russians to kill an enemy. The Germans could only guess what surprises succeeding days might bring.

Prelude to the Battle of Moscow: the Germans Caught Sevsk Completely Unawares

The 3rd Panzer Division quickly recovered and captured Sevsk on October 1, while its running mate, 4th Panzer Division, surged 130 miles and got its own surprise as it reached Orel on October 3. The public transportation trams were still running—and full of commuters, as if it were peacetime!

They also found great stocks of machinery on pallets along the roadside, waiting for relocation to the east and out of harm’s way. The division’s advance had been so rapid that it had outrun its own supply and had to wait in Orel for fuel to be airlifted in.

Soviet Bryansk Front commander General Andrei Eremenko thought that this attack on his southern flank was nothing but a diversion by a single corps, that the German main attack would come farther north near Bryansk. Consequently, he sent no forces south to reinforce the failing defenses there. Unfortunately for Eremenko, Guderian’s XXXXVII Panzer Corps, following behind XXIV Panzer Corps, abruptly wheeled north at Sevsk and surged toward Bryansk from the south.

As 2nd Panzer Army units surged through the Bryansk Front lines, Soviet Premier Josef Stalin became alarmed. He summoned one of the few armored leaders available, Maj. Gen. Dmitri Leliushenko, and sent him to Mtsensk on the Orel-Tula-Moscow road with orders to stop Guderian and push 2nd Panzer Army back. He sent a motorcycle regiment, the only troops at hand, with Leliushenko and told him that more troops would meet him at Mtsensk.

As he moved through the industrial city of Tula, Leliushenko commandeered all the guns at the artillery school there, but there were no tractors to tow the guns, so he also commandeered sufficient buses from the Tula Municipal Bus Line to tow them.

Stalin dispatched the 1st Tank Brigade to Leliushenko in Mtsensk the next day, and on the evening of October 6 it smashed into XXIV Panzer Corps units still awaiting fuel in Orel and dealt them significant losses.

The rest of Army Group Center joined the attack on October 2 with the 3rd and 4th Panzer Armies leading the way. Late on October 3, 3rd Panzer Army’s LVI Panzer Corps captured Kholm-Zirkovski and two undamaged bridges over the Dnieper River. The next day, 4th Panzer Army’s XXXXVI Panzer Corps captured Spas-Demensk, and then on October 5 its XXXX Panzer Corps captured Yukhnov, just 110 miles from Moscow. The Soviets moved mostly by foot and simply couldn’t keep pace with the panzers. Then it started to rain.

On October 6, XXXXVII Panzer Corps’ 17th Panzer Division captured Bryansk and two undamaged bridges over the Desna River, as well as the headquarters of the Soviet Bryansk Front. Fortunately for the Soviets, most of the front’s command staff and its commander escaped.

Even greater satisfaction was gained that day by 3rd Panzer Army and 4th Panzer Army when their units converged on Vyazma and completed the encirclement of four Soviet Armies: 16th, 19th, 20th, and 32nd.

Hitler’s War Machine Makes it Halfway to Moscow

The 3rd Panzer Army was now operating with a new commander. Col. Gen. Hermann Hoth was transferred to Poltava on October 5 to take over the 17th Army of Army Group South. General of Panzer Troops Georg-Hans Reinhardt replaced Hoth at 3rd Panzer Army and the commander of the 3rd Panzer Division, while General of Panzer Troops Walter Model replaced Reinhardt at XXXXI Panzer Corps.

Much of the southern half of the attack front had been suffering through intermittent rain for the past few days, but that changed to snow, the first snow the Germans experienced in Russia. But that didn’t mean an improvement in the ground conditions, where the mud grew deeper with each passing vehicle.

The 2nd Army infantry units began catching up with the armored advance by October 6, as its XXXXIII Corps captured Zhizdra on the Moscow highway northeast of Bryansk. Two days later units from 2nd Panzer Army’s XXXXVII Panzer Corps to the south contacted the 112th Infantry Division in Zhizdra, encircling the Soviet 50th Army. The remainder of the Soviet Bryansk Front, 3rd Army and 13th Army, were simultaneously being encircled at Trubchevsk, southwest of Bryansk.

Barely a week into their offensive the Germans were halfway to Moscow, having eliminated seven enemy armies in three great encirclements. Many Soviet troops were able to find their way out of the encirclements, but it is estimated that the Soviets lost close to a million men.

Now the snow had turned back into rain and sometimes came down in sheets, producing torrents of mud. German wheeled vehicles had to be abandoned, horses sank up to their bellies in the muck. All units began building corduroy roads, laying cut-down tree trunks side by side in a laborious process. The movement of supplies, including gasoline and ammunition, became difficult.

The weather was not as bad on the northern flank, but the ground conditions there were more difficult. Dense forest surrounds primordial swamps for miles on end, constricting traffic to major chokepoints. On October 8, the 9th Army’s VI Corps and 3rd Panzer Army’s XXXXI Panzer Corps were directed to turn north to assist the infantry units trying to advance there.

On the 10th they captured Sychevka, a railroad center on a main north-south line. One of the biggest problems they dealt with was abandoned Soviet cars and trucks blocking the few roads for miles; the rail line gave them a chance to work around that problem.

The BBC, on their October 10 evening newscast, announced the German victory at Vyazma, calling it Hitler’s most successful victory of the war and stating, “It had always been believed that the door to Moscow had been firmly barred. That obviously, is not the case!”

Leaders in Moscow had no clue what was happening on their Western Front; unlike the Bryansk Front, there had been no reports of the attack from either the Western Front or the Reserve Front. When stragglers from the Reserve Front reached Maloyaroslavets and reported on the situation, their information was discredited and they were jailed as panic mongers.

Unknown to Moscow, all long-distance telephone facilities in the West had been disrupted. The Soviet command relied heavily on telephone communication, and most higher headquarters had no long-range radios because of a widespread fear of German signal intercept capabilities.

When the Soviet monitoring service reported on Hitler’s radio address to the German people about the attack, the Soviet leaders were incredulous. Aerial reconnaissance planes returned with word of massive German tank columns surging past Spa-Demensk and Yukhnov. Marshal Boris Shaposhnikov, chief of the general staff, still didn’t believe it, so more flights were sent to verify the reports. Finally, although he was still confused and doubtful, Shaposhnikov went to Stalin with the news.

Later that day, phone communications with the Reserve Front were temporarily restored, and Stalin got through to the front headquarters. General Semyon Budenny, the front commander, was missing in action, but his chief of staff confirmed Stalin’s worst fears. The next day Stalin ordered General Georgi Zhukov, who had been commander in chief of the Leningrad Front for less than a month, to Mozhaisk to get a clear picture of the situation.

After reporting his findings to Stalin by phone, Zhukov learned that he had been made the new commander of the Western Front and that the surviving Reserve Front forces would be incorporated into the Western Front. Stalin ordered Zhukov to establish a defensive line at Volokolamsk-Mozhaisk-Maloyaroslavets and hold it.

Stalin Prepares for the Battle of Moscow

Stalin started gathering forces from all over the USSR for the defense of Moscow and quickly ordered 14 new rifle divisions, 14 new tank brigades, and 40 new artillery regiments dispatched to hold the Mozhaisk defensive zone. He also mobilized the civilian population of Moscow; some quarter of a million civilians, most of them women, commenced digging trenches and antitank ditches for the Moscow Defensive Zone.

Fuel was still a problem for the Germans and became so bad that 3rd Panzer Army’s XXXXI Panzer Corps consolidated all of its fuel and formed a special motorized Kampfgruppe with infantry, tanks, and artillery. The Kampfgruppe’s mission was to capture Kalinin, 90 miles to the northeast, and its bridge over the Upper Volga River. Making excellent progress it approached the great bridge in the early morning darkness of the 13th. The dispirited Soviet guards unit didn’t even put up a fight, leaving guns, equipment, and supplies, as it fled.

But now the poor weather spread over the northern flank, too. The rain changed to sleet, then snow, then back to rain, incessantly for days. The fall muddy season, or the “Rasputitsa,” as it is known in Russia, began in mid-October and quickly became more severe than any other in memory. Armored and motorized units couldn’t move; the infantry units slowly began to overtake the stranded mobile formations, but even walking was difficult.

On the south flank, XXIV Panzer Corps’ 4th Panzer Division was still struggling against the same problems: mud and lack of fuel. A small amount of fuel had been flown to them in Orel, allowing them to push up the road toward Mtsensk, but the armored units that Stalin had sent to block their advance did just that. The Soviet 1st Tank Brigade’s T-34 tanks, with their wider tracks, were able to maneuver in the mud while the German tanks couldn’t, and they would hit the 4th hard from one direction, then move to another angle and hit them again.

On October 12, XXIV Panzer Corps commander General Leo Geyr von Schweppenburg requested permission to pull his few remaining 4th Panzer Division tanks out of the Mtsensk battle, turn it over to his panzergrenadiers, and await reinforcements and supplies. With his units spread all over sealing pockets and held up by the mud and the lack of supplies, General Guderian agreed.

In the center of the army group attack front, 4th Army continued struggling through the mud eastward. The XIII Army Corps captured a bridge over the Ugra River just west of Kaluga on the 10th, then captured Kaluga and its bridges over the Oka River two days later. On October 14, the LVII Panzer Corps’ 3rd Motorized Division captured Borovsk, barely 52 miles from Moscow.

The German Advance Gets Stuck in the Mud

But the mud ground all operations to a halt. The only things still mobile were the small local “panje” carts, with their two big wooden wheels pulled by a small native pony. Robbed of their mobility, German units were strung out over hundreds of miles of sodden, soupy landscape with troops from different units mixed together.

Mother Nature had accomplished what the Soviets couldn’t: bring the German advance to a halt. Only when the ground had frozen completely could the assault be resumed in earnest. Unfortunately for the Germans, the soggy ground was not their only problem as the weather grew colder. Not only were their uniforms in tatters, they were summer uniforms. There was no winter clothing. They resorted to stripping the enemy of their heavy coats and hats. Hitler had expected that Operation Barbarossa would be successfully wrapped up in just a few months, so no preparations for dealing with cold weather were made.

Another growing problem was the flood of Soviet troops without organization or guidance across the landscape. Having individually escaped encirclement or just gotten separated from their units, they were still armed, and most knew the lay of the land better than the Germans. They struggled to reach their own lines that they only knew were somewhere to the east and were a constant threat, moving behind the Germans who faced their known enemy in the east.

After a bitter two-day battle, troops of the SS Division “Das Reich” of the 4th Panzer Army captured Borodino on October 15, just 66 miles west of Moscow. Borodino was famous as the site of Napoleon’s pyrrhic victory on the way to defeat at Moscow in 1812. The division commander, SS Obergruppenführer Paul Hausser, known as “Papa Hausser” as the founder of the Waffen SS, was badly wounded in the head and lost his left eye.

On October 17, panic spread through Moscow as the Soviet government offices begin to evacuate to Kuybyshev, widespread looting took place, party members were attacked in the street, and civilians begin to flee the city. The government quickly declared marshal law.

Stalin Tries to Hold the Line Outside Moscow

Also on the 17th, Stalin created a new front, the Kalinin Front, intended to force the Germans out of its namesake city and hold the vital northwestern corner of the Moscow defense line. The front was to be made up of four of the Soviet armies that had escaped encirclement and were commanded by the former commander of the West Front, General Ivan Konev.

By the third week in October, many of the pockets of encircled Soviet troops behind German lines had surrendered, freeing German troops to move up to the front. Of course, they still had to deal with their most vexing problems: the shortage of fuel, food, and ammunition, not to mention the Soviet defensive front, which was growing stronger by the day.

The center of the German attack still advanced, but only slowly as the mud became deeper and enemy defenses stronger. On the 18th, the German 4th Army came up against the still-forming “Mozhaisk Defensive Zone” when they took Maloyaroslavets and the next day when 4th Panzer Army captured Mozhaisk. On the 22nd, the 4th Army captured a bridgehead over the Nara River at Tashirovo, only 38 miles from Moscow. These fierce battles decimated both sides. Regiments were reduced to the size of companies with fewer than 200 men each. But the Germans moved inexorably forward, closing in on Moscow from three sides.

It was a violent days-long struggle for each of these places, where the Germans managed to bring more forces to bear more quickly and ensure victory at that spot. But the Soviets were moving all the forces they could to the Volokolamsk, Mozhaisk, Maloyaroslavets, and Kaluga axes, as these were the main access points west of Moscow.

On the southern flank of the attack, units of 2nd Panzer Army were still able to advance slowly in fits and starts, but they still had the farthest to go. General Guderian had taken all the tank forces of his XXIV Panzer Corps—panzer regiments from its 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions, as well as a battalion of tanks from the 18th Panzer Division—and combined them with the elite Grossdeutschland Panzergrenadier Regiment and an artillery regiment into a single attack force, all under the command of Colonel Heinrich Eberbach, panzer brigade commander of the 4th Panzer Division. With Kampfgruppe Eberbach, they could pool the paltry supplies of the corps and remain in action.

Once the combat bridging equipment had finally slogged forward through the mud, the engineers were able to construct a bridge over the Susha River just north of Mtsensk; Kampfgruppe Eberbach was able to cross on the 23rd. This flanking movement prompted the Soviet 1st Tank Brigade to pull its heavy tanks out of Mtsensk.

The next day Kampfgruppe Eberbach, bypassing Mtsensk, seized Chern, 159 miles from Moscow. This left the large blocking force that the Soviets had installed in Mtsensk with nothing to block.

Pushing up the Tula highway and pursuing the troops retreating from Mtsensk, Eberbach seized Yasnaya Polyana on the 28th—only 111 miles south of Moscow. The only reason that they were able to advance at all is that they could use the hard-surface Kharkov-Orel-Tula-Moscow highway as well as the railroad tracks, which paralleled the highway for much of its run.

In the middle of the 20th century, parts of Russia were still fairly primitive. Most roads were nothing more than dirt pathways, the main roads between towns being hard, compacted earth. Hard-surface macadam roads were limited to those routes connecting Moscow to a handful of large cities.

On October 28, the 9th Army was ordered to go on the defense along the northern flank of the advance. It was to tie in with 3rd Panzer Army at Kalinin and AGN to the west near Ostashkov and protect the army group’s advance from the north.

In the last week of October, the 2nd Army was transferred to the southern flank of the army group, taking command of the XXXIV and XXXV Army Corps and the XXXXVIII Panzer Corps that were already there. This allowed the 2nd Panzer Army to concentrate on the Moscow offensive while 2nd Army concentrated on clearing the southern flank of the army group and maintaining contact with Army Group South.

Although the XXXIV and XXXV Army Corps, as well as the XXXXVIII Panzer, were mostly immobilized by the mud in the wide-open spaces between Orel and Kursk, they devised a plan to utilize a captured Soviet armored train to attack Kursk and secure the Orel-Kursk rail line. Colonel Carl Andre, with two reinforced battalions from his 521st Infantry Regiment, was placed in command of the captured train while other troops from the 296th Infantry Division manned the train’s guns.

The Germans Approach a Lightly Defended Kursk

On November 2, while the armored train successfully secured the rail line, XXXXVIII Panzer Corps troops approached Kursk slowly from the northwest. To everyone’s surprise, most of the Soviet troops in Kursk had already withdrawn, and the remaining troops did so as the Germans arrived. This was fully a year and a half before that name would be written near the top of the list of great battles in the war.

The 4th Army attack, in the middle of the army group, slowed to positional warfare by the end of October. The combination of the mud, dwindling supplies, and stiffening enemy resistance left the commander, Field Marshal Gunther von Kluge, with no choice.

The 4th Panzer Army was similarly affected as its advance slowly ground to a halt. The slow but steady German advance against determined resistance was a war of attrition. The troops were just about spent. Just moving around in the knee-deep mud was exhausting.

Hitler’s “Continuation Plan” for the Encirclement of Moscow

During the second week of November, with most of their forces stuck in the mud, the German generals were making plans for the continuation of the attack once the ground froze. Halder, after a conference with principle staff officers of the army group, realized that it was weaker than he had thought and that it would not be able to take Moscow in 1941.

But now Hitler was adamant. Moscow must be taken! He saw that the morale of the German public was waning because earlier pronouncements had raised expectations that weren’t being met. Moscow must be taken or at least isolated to reassure the German public of Hitler’s strength and resolve. Hitler finally came around to the need of taking Moscow just as his leading generals were having second thoughts.

The Continuation Plan called for two mobile groups to strike at the Soviet flanks and encircle Moscow, 3rd Panzer Army on the north and 2nd Panzer Army on the south, meeting in the Orekhova-Zueva area east of Moscow. The 4th Army and 4th Panzer Army were to assault Moscow frontally from the west, drawing any enemy reinforcements away from the flanks while 9th Army and 2nd Army would cover the north and south flanks, respectively.

After a few days’ rest, the troops were refreshed. They had their first hot meal in days and had been resupplied with ammunition and other essentials. They were as ready as they could be.

The ground was beginning to firm up, thanks to continuing cold weather, making movement more possible by the day. But the Germans were also beginning to confront a new obstacle. Fresh Soviet troops from as far away as Siberia had begun manning the defenses around Moscow—well-trained, experienced troops that didn’t panic at the first sight of a German tank.

By the middle of November, the Soviets had an impressive array of 12 armies facing Bock’s troops. The Western Front had the 5th, 16th, 33rd, 43rd, 49th, and 50th Armies lined up from Volokolamsk south to Tula. The Kalinin Front had the 22nd, 29th, 30th, and 31st Armies on the north flank from Volokolamsk north to Kalinin then west to Ostashkov. The newly constituted Southwest Front held the southern approaches from Efremov and Yelets with the 3rd and 13th Armies. These don’t include the 59 rifle divisions, 13 cavalry divisions, 75 rifle brigades, and 20 tank brigades held in reserve, nor the 65,000-man Peoples Militia manning the complex series of barricades and strongpoints ringing Moscow.

The ground became frozen, but the temperature kept right on dropping; -15°C on November 12, -8°C on the 13th, and -13°C on the 14th, making the winter of 1941-1942 one of the most severe on record. The first week of December the low temperature in the western approaches to Moscow dropped 28°C, down to -33°C on December 7.

Engines of all types had to be left running lest they freeze, making gasoline all the more vital, and the mechanisms of guns of all calibers did freeze. Then there was the problem that replaced the mud more directly—snow, and lots of it.

In addition to their growing manpower pool, the Soviets had two major advantages: they fought from well-prepared defensive positions from Kalinin in the north all the way south to Tula while the Germans only dug holes in the snow. And they were supplied through short “inside” lines. They were backed right up to Moscow, from where their supplies came. The Germans were hundreds of miles from their main supply depots and were now depending on air dropped supplies to survive.

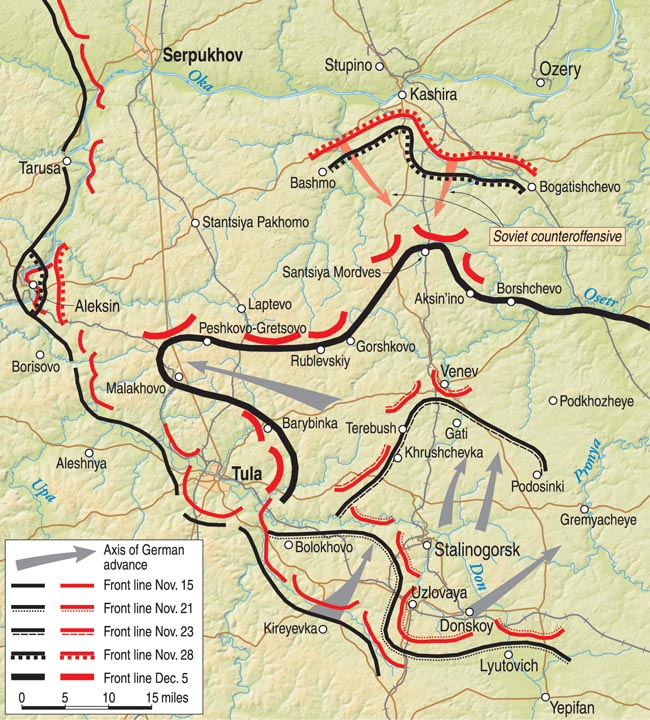

To disrupt German efforts to resume the attack, Stalin ordered Zhukov to launch a series of spoiling attacks at the major access points west of Moscow. Zhukov thought that it was too late for that, but he complied. He ordered the 16th Army to attack the north flank of the 4th Panzer Army above Volokolamsk, the 49th Army to attack 4th Army’s southern flank west of Serpukhov, and the 49th and 50th Armies to attack 2nd Panzer Army’s spearheads north and south of Tula.

The 16th Army’s spoiling attack on the 4th Panzer Army included the 3rd Cavalry Corps, which was made up of newly arrived forces from the Far East. On November 17, following up on the slightly successful initial attack, the Corps’ 44th Mongolian Cavalry Division was ordered to exploit that success with an attack on the German 106th Infantry Division near Musino.

A Scene from Another Era: Mounted Soviets Charge the Germans with Extended Sabers

Bent low in the saddle, their sabers thrust high, the division’s 1st Mounted Regiment charged across the fields toward the German position—a scene from the 1800s. Suddenly, the field erupted with explosion after explosion. The 106th’s artillery regiment had the field completely zeroed in; it was only a matter of pulling the lanyards. Men, horses, and pieces of flesh flew through the air in sickening repetition, until there was no longer any movement.

Then, incredibly, the Division’s 2nd Mounted Regiment formed up and charged across the very same field—with the very same result: 2,000 horsemen and their mounts obliterated in a little over a quarter of an hour. The Soviet attack collapsed. The defending 106th suffered no casualties.

The Soviet spoiling attack against 4th Army’s southern flank at Serpukhov fared somewhat better. The XIII Army Corps held the longest front in the 4th Army—nearly 50 miles from Dubrovka on the Nara River east of Maloyaroslavets south to Petrovka on the Oka River southwest of Aleksin—with only three divisions.

The initial attack on November 15 came as a complete surprise. The 5th Guards Division led the attack with its tank battalion and made several penetrations along the northern half of the corps front near Voronina.

Field Marshal von Kluge dispatched parts of several units that had been set aside for the renewal of the offensive to shore up the XIII Corps defense. After three days of desperate combat, they began to push the enemy back. At that point Zhukov sent in a follow-up attack by newly arrived units that once again had the Germans struggling. Fortunately for them, the Soviet attack subsided on the 19th as Zhukov was forced to move units to face the renewed 4th Panzer Army attack against his right flank.

Farther south, Zhukov’s spoiling attack on 2nd Panzer Army bore some fruit on the 17th when elements of the German 112th Infantry Division of the LIII Corps, which had no effective antitank weapons, broke and ran when attacked by T-34 tanks south of Uslovia. Guderian later pointed out that the division had already lost more than 1,000 men to frostbite and that its automatic weapons were inoperable due to the sub-zero temperatures.

In spite of the spoiling attacks, Army Group Center resumed its attack toward Moscow on the morning of November 15. The XXVII Army Corps, on the right wing of 9th Army, surged southeast from Kalinin along the southern bank of the Volga River to its confluence with the Lama River near Redkino.

The 3rd Panzer Army also attacked that day when the LVI Panzer Corps troops struck out from their positions north of Volokolamsk near Lotoshino, eastward toward the Kalinin-Moscow highway. The 6th Panzer Division pushed ahead of the others and crossed the Lama River the next day. On the 17th, the 6th Panzer contacted XXVII Army Corps units on the Kalinin-Moscow highway near Savidovo.

The 4th Panzer Army was not able to resume the attack on the 15th as it was still busy trying to handle the Soviet spoiling attack on its northern flank. It was the same in the 4th Army sector, where they were trying to keep enemy attacks from overwhelming their southern flank.

In the panzer army zone, most of its units were unable to resume the assault on the 15th because they, too, were still under attack; XXXXIII Army Corps had been under intense attack just south of Aleksin by the Soviet 49th and 50th Armies since November 11, and LIII Army Corps was still dealing with the enemy spoiling attack. On the 18th, the XXIV Panzer Corps was finally able to resume its attack south of Tula toward Venev. In a surprise move, panzer corps units quickly captured Dedilovo and the only intact bridge over the Upa River.

On the far southern flank of the army group, 2nd Army’s XXXIV Army Corps also resumed the advance on the 15th against light opposition, quickly occupying Ponyri in the afternoon. The XXXV Army Corps joined the attack on the 18th, pushing eastward from Novosil against only moderate resistance.

A Serious Supply Issue Hits the German Advance

Although the ground was frozen and motorized traffic was once again able to move, the supply situation was still critical, and units were stranded for lack of gasoline. Then there was the continuing problem of the weather. Fresh snow fell virtually every day, quite often in blizzard conditions, and snow depths of one to two feet were not uncommon.

The 4th Panzer Army was finally able to resume its attack on the 18th, at least with its three left flank corps—XXXX and XXXXVI Panzer Corps and V Army Corps—but ran into a very stubborn enemy entrenched in deep, fortified emplacements. After three days of slugging in brutal weather conditions, they had gained only four miles on average.

Frustrated, General Hoepner threw in his last reserves, and in two days they surged 14 miles through the seam between 16th Army and 30th Army. When they could not be contained, Zhukov had no reserves on hand to throw at them because he had used them all in the Stalin-ordered spoiling attacks.

General Halder called Bock on the 18th wanting to know why 4th Army had not resumed the attack. Bock told him that 4th Army was still fending off the strong Russian attacks on its southern flank and that von Kluge had sent his only reserves there. Bock counseled patience and told Halder that von Kluge would resume the offensive just as soon as he could. Bock and Halder agreed that both combatants were near the end of their strength and that victory would go to the side with the strongest will.

The 9th Army, on the AGC northern flank, went over to the defense on the 19th. The 9th was holding a northeast-facing front along the Volga River from Savidovo northwest to Kalinin then west about 100 miles and connecting with Army Group North near Ostashkov. There was little offensive action on that front; they were just guarding the back of the army group units attacking toward Moscow.

By November 20, the remainder of 3rd Panzer Army’s LVI Panzer Corps had closed up with the 6th Panzer Division on the Kalinin-Moscow highway and turned south. Two days later they captured Klin, 47 miles north of Moscow.

If LVI Panzer Corps could continue south, it could possibly slice in behind the Soviet 16th Army troops fighting 4th Panzer Army troops to the southwest. This wasn’t lost on the Soviets, who quietly began looking over their shoulder.

Not surprisingly, the 4th Panzer Army began pushing steadily forward. On the 18th, XXXX Panzer Corps units captured Mozhaisk, and on the 21st, XXXXVI Panzer Corps units captured Novopetrovskoye, only 42 miles from Moscow.

It was on the army’s northern flank, farthest from Moscow, where the V Army Corps was able to move forward the most quickly. It reached the Kalinin-Moscow highway about 10 miles south of Klin on the 21st, turned south, and on the 23rd captured Solnechnogorsk, just 32 miles from Moscow. That same unit, 2nd Panzer Division, captured Krasnaya Polyana two days later and stood only 15 miles north of Moscow.

With the 4th Panzer Army units moving south on the Kalinin-Moscow highway, Bock changed the orders for 3rd Panzer Army. Rather than continue south on the highway behind 4th Panzer Army, they were now to turn east and push as far as possible while still covering the 4th Panzer Army’s left flank.

The southern half of the encirclement attack was also picking up speed. The 2nd Panzer Army’s XXIV Panzer Corps, after a vicious fight, captured Uslovia on the 20th, then Novomoskvosk on the 22nd and Venev on the 24th. Likewise with the XXXXVII Panzer Corps on their right, which captured Efremov on November 20 and Michailov on the 24th. But Guderian told Bock that fresh, well-armed Siberian troops “keen for battle” were flooding in on his eastern flank.

On November 27, Bock ordered Guderian to forget about striking northeast for the moment and concentrate on taking Tula, the long festering sore that was the anchor for the Soviets on the southern flank of Moscow. The Soviet 50th Army had been holding Tula since the beginning of the German attack and had launched almost daily attacks against the 2nd Panzer Army as it closed in.

Tula was not encircled, but the 2nd Panzer Army held three sides around it with a 30-mile-wide opening on the north. The current plan was for 2nd Panzer Army’s XXXXIII Corps to attack toward the east from Aleksin and meet XXIV Panzer Corps units attacking from the east, closing the encirclement.

The Luftwaffe’s Role in the Battle of Moscow

The Luftwaffe also played a significant part in German operations in Russia. Air Fleet 2, commanded by Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, was attached to Army Group Center from the beginning, and his Junkers Ju-87 Stuka ground attack aircraft led almost every large assault that the Germans undertook. In addition to leading the ground assault, by the end of November Air Fleet 2 had destroyed 6,670 Russian aircraft, 1,900 tanks, 26,000 motor vehicles, and 2,800 trains.

Surprisingly, at the end of November, Air Fleet 2 was transferred to Italy to help the flagging Axis effort in the Mediterranean. This, of course, left AGC drastically short of combat aircraft. Consequently, the Red Air Force immediately claimed air superiority and would hold it for the foreseeable future.

While 4th Panzer Army’s V Army Corps moved south on the Kalinin-Moscow highway, 3rd Panzer Army pushed east behind it. That was when something unusual happened, something that no one could recall ever happening during this campaign. As German units neared, the Soviets withdrew without putting up a fight, and they didn’t burn down the villages as they left. Some thought that they must be expecting to return soon; others thought they were becoming disillusioned and were just in a hurry to get out. Units of the LVI Panzer Corps soon reached the Volga-Moscow canal near Dmitrov, 37 miles due north of Moscow.

With 4th Panzer Army having opened a gap between the Soviet 16th and 30th Armies and 3rd Panzer Army quickly moving eastward through the gap, a crisis erupted in Moscow. The 3rd Panzer Army’s move pushed the Soviet 30th Army into the corner between the Volga River on the north and the Volga-Moscow canal on the east—thus opening a 27-mile gap in Russian lines between 3rd Panzer Army at Dmitrov on the canal and 4th Panzer Army at Krasnaya Polyana.

It is not clear whether the Germans realized their opportunity, but LVI Panzer Corps’ 7th Panzer Division quickly grabbed a bridgehead over the canal at Jakhroma, four miles south of Dmitrov. Army Commander Reinhardt wanted to attack eastward, but Bock ordered him to continue south, west of the canal, covering 4th Panzer Army’s left flank.

“Doubts of Success Are Beginning to Take Definite Form”

On the 28th, the 4th Panzer Army’s XXXX Panzer Corps, closing in from the northwest, captured Lenino, 18 miles from Moscow. Two days later, XXXXVI Panzer Corps’ 11th Panzer Division captured Kryukovo, just 16 miles from Moscow.

That same day a combat group from V Army Corps’ 2nd Panzer Division, fighting its way south on the Kalinin-Moscow highway, reached Ozeretskoye, the terminus of the Moscow tram system, and Lobnja, where they blew up railroad tracks just 13 miles from Moscow. Late in the day a motorcycle patrol from the division reached Khimki, barely six miles from Moscow. If the troops could continue the pressure, Moscow could be theirs.